Under Pressure: Time Management, Self-Leadership, and the Nurse Manager

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Context of Healthcare Settings

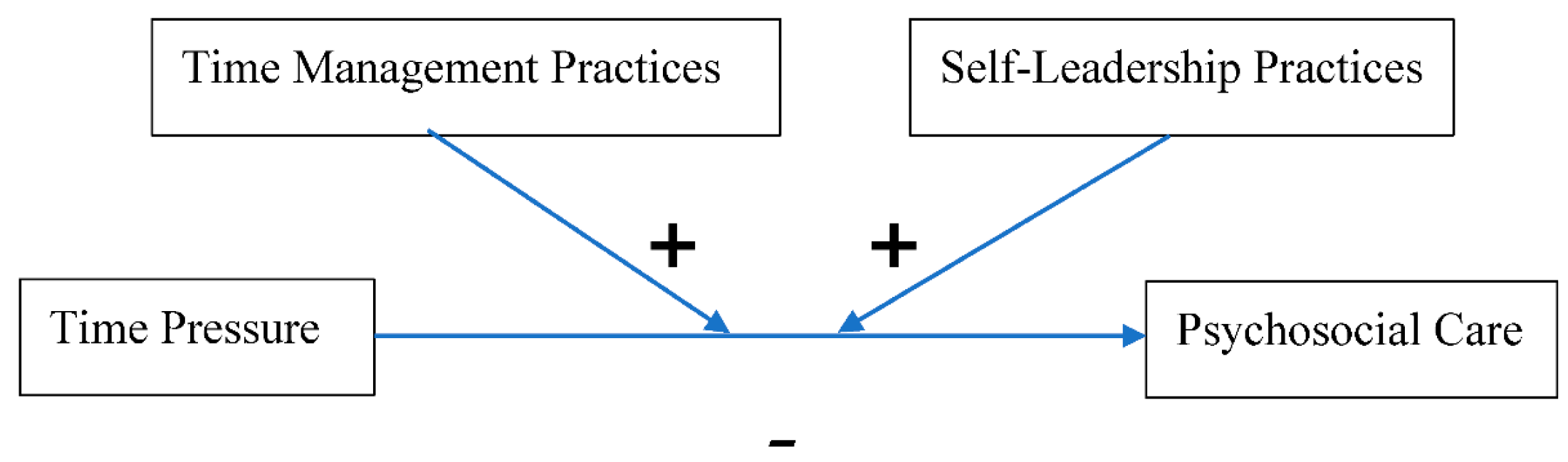

3. The Time Pressure Mitigation Model for Nurse Managers

3.1. Time Pressure and Psychosocial Care

Metaconjecture 1:In situations where nurse managers face increased time pressure, providing quality psychosocial care will be compromised; i.e., the more time pressure a nurse manager experiences, the less psychosocial care their patients receive.

3.2. Time Management for Nurse Managers

- Never relying solely on your memory and instead referring to reminders and lists.

- Accomplishing the most important task as early in the day as possible.

- Paying attention to the time of day that you are most productive and utilizing that time for your most important tasks.

- Keep multitasking to a minimum. Many psychologists believe that multitasking does not actually exist, meaning you can only put your attention on one thing at a time. When people think they are multitasking, they are actually only shifting their attention inefficiently from one matter to another in quick bursts. Each time a person moves their attention back to a previous matter, a transition in cognition must take place. Any momentum the person had in their thought process is interrupted, and the brain must reorient to the new focus. These reorientations may be minute, but over the course of hours, days, and weeks, significant time can be lost in perceived “multitasking.” Thus, it is more efficient and productive to complete tasks with full attention and then move onto the next one needing accomplished.

- Attending to emails only at set times each day, and, when possible, for a determined amount of time.

- Keeping your work area neat and organized. It can help minimize search time for needed resources. Additionally, many productivity experts believe that removing clutter in a physical space helps the mind to focus attention more fully on that matter at hand.

- If able, finishing small tasks before handling larger ones.

- Defining what work needs to be done the next day and writing it down before the end of the shift.

- Taking breaks and doing something enjoyable after you have accomplished a task. Recharge a bit, if possible, before moving onto the next task that needs attention. Improved productivity is a long-term game, not a short burst of frantic task hopping.

- Enjoying the dopamine that the brain secretes when tasks and goals are accomplished. Completing activities feels good and serves to encourage further accomplishment. Therefore, consciously managing activities and the time required for their accomplishment boosts mental and physical health by releasing positive neurochemicals into the bloodstream, as opposed to excessive cortisol that is released over time in unorganized and pressure-packed environments (Lee et al. 2015).

Metaconjecture 2:In situations where nurse managers face increased time pressure, proper application of research-based time management practices can improve psychosocial care; i.e., time management practices positively moderate the negative relationship between time pressure and psychosocial care.

3.3. Self-Leadership for Nurse Managers

- Self-observation—Developing the self-knowledge of when and why a person participates in the actions she/he does. In the context of nurse managers, this suggests that the self-awareness of the antecedents and consequences of perceived time pressure is critical. Self-awareness is a crucial aspect of altering or eradicating self-destructive or limiting behaviors; (Manz and Sims 1980; Manz and Neck 2004; Neck and Houghton 2006).

- Self-goal setting—Having awareness of present actions and results can help a person set meaningful goals for themselves (Manz 1986; Manz and Neck 2004; Manz and Sims 1980; Neck and Houghton 2006). Research supports the effectiveness of establishing challenging and precise goals to improve a person’s performance (Locke and Latham 1990; Neck and Houghton 2006).

- Self-reward—Personal goals that are met with rewards one finds pleasing and desirable can encourage a person to take the initiative to overcome procrastination and/or poor prioritization (Manz and Sims 1980; Manz and Neck 2004).

- Self-punishment (also known as “self-correcting feedback”)—Entails positive honesty, reframing failures and unproductive actions in a way that can help a person remodel future actions. This strategy comes with a caveat, though: self-punishment centered on self-criticism should be used sparingly, lest a person incur excessive guilt that damages self-esteem, self-efficacy, and self-confidence that hinders future performance (Manz and Sims 1991; Neck and Houghton 2006).

- Self-cueing—Designing your work environment with reminders to maintain positive self-leadership behaviors and thoughts. Concrete environmental cues such as notes, lists, and inspiring quotes can help a person return their attention to making progress toward their goals. For example, nurse managers could place pictures in the rooms in which they work reminding them to take deep breaths and focus on the patients on the unit at that particular point in time.

- Building positive features into an activity, so that doing it becomes a reward in itself (Manz and Neck 2004; Manz and Sims 1991). For example, if a nurse manager likes music, she/he could relate what she/he wants to accomplish on the unit at the moment with a song. Perhaps she/he could sing to himself, “Everybody’s workin’ for the weekend!” as she/he looks at timesheets.

- Deliberately turning attention from the ungratifying features of a task and placing it on the more inherently rewarding characteristics of the required action (Manz and Neck 2004; Manz and Sims 1991; Neck and Houghton 2006). An example for the nurse manager could be a daily mental reminder to themselves and their staff as to why they entered the profession in the first place—that is, a reminder to help and care for people. This reminder could help the nurse manager focus on the naturally rewarding aspect of the job instead of focusing on the perceived time pressure.

- Acknowledging and replacing dysfunctional beliefs and assumptions—A person should scrutinize thoughts that are not helpful to achieving goals and exchange them for more rational and productive thoughts and beliefs (Ellis 1977; Manz and Neck 2004; Neck and Manz 1992).

- Practicing positive self-talk—What we quietly say to ourselves should be positive (Neck and Manz 1992, 1996), including our self-evaluations and reactions to events (Ellis 1977; Neck and Manz 1992). Negative and unhelpful self-talk should be acknowledged and exchanged with helpful internal monologues. Mindfully observing the patterns we use to talk to ourselves helps us to replace unconstructive self-talk when it arises. The mind can only focus on one matter at a time, so it is better to place its attention on self-dialogues that are optimistic and hopeful (Seligman 1991).

- Practicing mental imagery or visualization—Develop the skill of intentionally imagining a future event or task in advance of its actual occurrence (Finke 1989; Neck and Manz 1992, 1996). Those who can picture successful completion of a future event or task before it is actually performed are more likely to attain that result (Manz and Neck 2004). Moreover Driskell et al. (1994) conducted a meta-analysis of 35 empirical studies and discovered that mental imagery has a significant positive effect on individual performance (Manz and Neck 2004; Manz and Sims 1980, 2001). Mental imagery can be useful when a problem stems from time pressure. In that case, the nurse manager would picture herself in a calm manner listening to the nurses’ concerns over the challenges at hand, offering timely encouragement, and providing useful, deliberate direction. Solutions can be created that can ultimately save time in the future.

- All-or-nothing thinking—one perceives issues as “black-and-white” instead of as complex situations with a lot of variables and possible perspectives (for example, if events do not play out as hoped, one distinguishes only all-embracing failure).

- Overgeneralization—one oversimplifies a specific failure as having a perpetual nature to it (for example, a person may say to themselves, “I always screw up!”).

- Mental Filtering—one perseverates on one dissatisfying feature of something, thus misrepresenting all other aspects of reality (for example, a nurse manager may have one nurse in the unit who is particularly challenging to her/him, and she/he may think, “My employees all hate me!”).

- Disqualifying the positive—one disregards valuable occurrences (for example, “Well, I got lucky there. That will never happen again.”).

- Jumping to conclusions—one assumes certain conditions of a situation are negative before there is enough evidence to do so (for example, “The top administrators of the hospital are coming today to inspect the unit. They’re bound to find something they’re not happy with.”).

- Magnifying and minimizing—one heightens the significance of negative elements and lessens the presence of positive ones (for example, “Yes, the new nurses on the unit are doing great work, but you know they’ll move onto higher paying hospitals. The good ones always do.”).

- Emotional reasoning—one is steered by negative emotions (for example, on entering the hospital, the nurse manager says to herself, “Well, I wonder what disaster will happen today on the unit.”).

- Labeling and mislabeling—one spontaneously applies undesirable labels to describe oneself, others, or an event (for example, during a break, the nurse manager sarcastically thinks to himself, “How did I end up being the king on this ‘island of misfits’?”).

- Personalization—one accuses oneself for undesirable situations or conclusions that have other origins (for example, “I just know these new directives from the director are because of something I did wrong!”).

Metaconjecture 3:In situations where nurse managers face increased time pressure, proper application of self-leadership practices can improve psychosocial care; i.e., self-leadership practices positively moderate the negative relationship between time pressure and psychosocial care.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aiken, Linda H., Sean P. Clark, Douglas M. Sloane, Julie Sochalski, and Jeffry H. Silber. 2002. Hospital Nurse Staffing and Patient Mortality, Nurse Burnout, and Job Dissatisfaction. JAMA 288: 1987–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2007. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the Art. Journal of Managerial Psychology 22: 309–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, Michael J., Adam Sullivan, Andrea C. Enzinger, Zachary D. Epstein-Peterson, Yolanda D. Tseng, Christine Mitchell, Joshua Niska, Angelika Zollfrank, Tyler J. VanderWeele, and Tracy A. Balboni. 2014. Nurse and Physician Barriers to Spiritual Care Provision at the End of Life. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 48: 400–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, Albert. 1986. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, Albert. 1991. Social Cognitive Theory of Self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50: 248–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberà-Mariné, M. Gloria, Lorella Cannavacciuolo, Adelaide Ippolito, Cristina Ponsiglione, and Giuseppe Zollo. 2019. The Weight of Organizational Factors on Heuristics. Management Decision 57: 2890–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, Adam, and David G. Rand. 2016. Intuition, Deliberation, and Evolution of Cooperation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 113: 936–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belcher, Melanie, and Linda K. Jones. 2009. Graduate Nurses Experiences of Developing Trust in the Nurse-patient Relationship. Contemporary Nurse 31: 142–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Zur, Hasida, and Shlomo J. Breznitz. 1981. The Effect of Time Pressure on Risky Choice Behavior. Acta Psychologica 47: 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, Barbara J., Cathy Lauring, and Nora Jacobson. 2001. How Nurses Manage Time and Work in Long-term-care. Journal of Advanced Nursing 33: 484–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britton, Bruce K., and Abraham Tesser. 1991. Effects of Time-management Practices on College Grades. Journal of Educational Psychology 83: 405–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundgaard, Karin, E. Erik Sorensen, and Charlotte Delmar. 2016. Time-making the Best of it! A Fieldwork Study Outlining Time in Endoscopy Facilities for Short-Term Stay. Open Nursing Journal 10: 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Pete E. 1983. Talking to Yourself—Learning the Language of Self-Support. New York: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Engle A., Aled Jones, and Kitty Wong. 2013. The Relationships between Communication, Care and Time are Intertwined: A Narrative Inquiry Exploring the Impact of Time on Registered Nurses’ Work. Journal of Advanced Nursing 69: 2020–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Cheng H., and Bonnie Raingruber. 2014. Educational Needs of Inpatient Oncology Nurses in Providing Psychosocial Care. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing 18: E1–E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, Brigitte J. C., Wendelien Eerde, Christel G. Rutte, and Robert A. Roe. 2007. A Review of the Time Management Literature. Personnel Review 36: 255–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cone, Kelly J., and Ruth Murray. 2002. Characteristics, Insights, Decision Making, and Preparation of ED Triage Nurses. Journal of Emergency Nursing 28: 401–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristofaro, Matteo 2020. Unfolding Irrationality: How do Meaningful Coincidences Influence Management Decisions? International Journal of Organizational Analysis. forthcoming.

- Davidson, Judy, Janet Mendis, Amy R. Stuck, Gianni DeMichele, and Sidney Zisook. 2018. Nurse Suicide: Breaking the Silence. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, Edward, and Richard Ryan. 1985. The Support of Autonomy and Control of Behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 53: 1024–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCola, Paula R., and Phil Riggins. 2010. Nurses in the Workplace: Expectations and Needs. International Nursing Review 57: 335–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, Evangelia, Arnold B. Bakker, Friedhelm Nachreiner, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2001. The Job Demands-resources Model of Burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driskell, James E., Carolyn Cooper, and Aidan Moran. 1994. Does Mental Practice Enhance Performance? Journal of Applied Psychology 79: 481–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebright, Patricia R., Linda Urden, Emily Patterson, and Barbara Chalko. 2004. Themes Surrounding Novice Nurse Near-miss and Adverse-event Situations. Journal of Nursing Administration 34: 531–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efron, Louis. 2014. Six Reasons your Best Employees Quit You. Available online: http://www.forbes.com/sites/louisfron/2013/06/24/six-reasons-your-best-employees-quit-you/ (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Ellis, Albert. 1977. The Basic Clinical Theory of Rational-Emotive Therapy. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Everett, Jim A., Zach Ingbretsen, Fiery Cushman, and Mina Cikara. 2017. Deliberation Erodes Cooperative Behavior-Even Towards Competitive Out-groups, Even When Using a Control Situation, and Even When Eliminating Selection Bias. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 73: 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finke, Ronald A. 1989. Principles of Mental Imagery. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Marilyn L., and Deborah J. Dwyer. 1996. Stressful Job Demands and Worker Health: An Investigation of the Effects of Self-monitoring. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 25: 1973–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, Marilyn L., Deborah J. Dwyer, and Daniel C. Ganster. 1993. Effects of Stressful Job Demands and Control of Physiological and Attitudinal Outcomes in a Hospital Setting. Academy of Management Journal 26: 289–423. [Google Scholar]

- Ganster, Daniel C. 2005. Executive Job Demands: Suggestions from a Stress and Decision-making Perspective. Academy of Management Review 30: 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbugly, Etienne. 2013. Time Management Hacks I Wish I had known. Available online: www.slideshare.net/egarbugli/26-time-management-hacks-i-wish-id-known-at20?utm_source=slideshowandutm_medium-ssemailand utm_campaign=weekly_digest (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Gardner, Donald G. 1986. Activation Theory and Task Design: An Empirical Test of Several New Predictions. Journal of Applied Psychology 71: 411–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gärling, Tommy, Amelie Gamble, Filip Fors, and Mikael Hjerm. 2016. Emotional Well-being Related to Time Pressure, Impediment to Goal Progress, and Stress-related Symptoms. Journal of Happiness Studies 17: 1789–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, Donald G., and Lindsey L. Cummings. 1988. Activation Theory and Job Design: Review and Reconceptualization. Research in Organizational Behavior 10: 81–122. [Google Scholar]

- Gelsema, Tanya I., Margot van der Doef, Stan Maes, Marloes Janssen, Simone Akerboom, and Chris Verhoeven. 2006. A Longitudinal Study of Job Stress in the Nursing Profession: Causes and Consequences. Journal of Nursing Management 14: 289–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gerdtz, Marie F., and Tracey K. Bucknall. 1999. Why We do the Things We do: Applying Clinical Decision-making Frameworks to Triage Practice. Accident and Emergency Nursing 7: 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdtz, Marie F., and Tracey K. Bucknall. 2001. Australian Triage Nurses’ Decision-making and Scope of Practice. Australian Emergency Nursing Journal 4: 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsby, Elizabeth, Michael Goldsby, Christopher P. Neck, and Christopher B. Neck. 2020. Self-leadership in a Hospital Setting: A Framework for Addressing the Demands of Nurse Managers. Journal of Leadership and Management. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, Cleotilde. 2004. Learning to Make Decisions in Dynamic Environments: Effects of Time Constraints and Cognitive Abilities. Human Factors 46: 449–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greggs-McQuilkin, Doris. 2004. The Stressful World of Nursing. Medsurgical Nursing 13: 141, 189. [Google Scholar]

- Greiner, Birgit A., Niklas Krause, David Ragland, and June M. Fisher. 2004. Occupational Stress and Hypertension: A Multi-method Study Using Observer-based Job Analysis and Self-reports in Urban Transit Operators. Social Science and Medicine 59: 1081–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurses, Ayse P., Pascale Carayon, and Melanie Wall. 2009. Impact of Performance Obstacles on Intensive Care Nurses’ Workload, Perceived Quality, and Safety of Care, and Quality of Working Life. Health Services Research 44: 422–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, Minhi, Robert Lawson, and Young G. Lee. 1992. The Effect of Time Pressure and Information Load on Decision Quality. Psychology and Marketing 9: 365–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, Donald C., Sydney Finkelstein, and Ann C. Mooney. 2005. Executive Job Demands: New Insights for Explaining Strategic Decisions and Leader Behaviors. Academy of Management 30: 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, Kerry A., Leann M. Aitken, and Christine Duffield. 2009. A Comparison of Novice and Expert Nurses’ Cue Collection during Clinical Decision-making: Verbal Protocol Analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies 46: 1335–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilhan, Mustafa N., Elif Durukan, Ender Taner, Isil Maral, and Mehmet A. Bumin. 2008. Burnout and its Correlates among Nursing Staff: Questionnaire Study. Journal of Advanced Nursing 61: 100–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, Onne. 2001. Fairness Perceptions as a Moderator in the Curvilinear Relationships between Job Demands, and Job Satisfaction and Job Performance. Academy of Management Journal 44: 1039–50. [Google Scholar]

- Josefsson, Karin. 2012. Registered Nurses’ Health in Community Elderly Care in Sweden. International Nursing Review 59: 409–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasek, Robert A. 1979. Job Demands, Job Decision Latitude and Mental Strain: Implications for Job Redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly 24: 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Carol J., Paul M. Lane, and Jay D. Lindquist. 1991. Time Congruity in the Organization: A Proposed Quality of Life Framework. Journal of Business and Psychology 6: 79–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman-Scarborough, Carol, and Jay D. Lindquist. 1999. Time Management and Polychronicity: Comparisons, Contrasts, and Insights for the Workplace. Journal of Managerial Psychology 14: 288–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, Amanda, and Ann Allenby. 2013. Barriers to Nurses Providing Psychosocial Care in the Australian Rural Context. Nursing and Health Sciences 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakein, Alan. 1973. How to Get Control of your Time and Life. New York: Nal Penguin Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lawless, Jane, Lixin Wan, and Irene Zeng. 2010. Patient Care ‘Rationed’ as Nurses Struggle under Heavy Workloads—Survey. Nursing New Zealand 16: 16–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lay, Clarry, and Henri C. Schouwenburg. 1993. Trait Procrastination, Time Management, and Academic Behavior. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality 8: 647–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Do Y., Eosu Kim, and Man H. Choi. 2015. Technical and Clinical Aspects of Cortisol as a Biochemical Marker of Chronic Stress. BMB Reports 48: 209–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legg, Melanie J. 2011. What is Psychosocial Care and How Can Nurses Better Provide it to Adult Oncology Patients. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 28: 61–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, Kurt. 1952. Field Theory in Social Science: Selected Theoretical Papers by Kurt Lewin. London: Tavistock. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Marianne, and Andrew Grimes. 1999. Metatriangulation: Building Theory from Multiple Paradigms. The Academy of Management Review 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Joanne, Fiona Bogossian, and Kathy Ahern. 2010. Stress and Coping in Singaporean Nurses: A Literature Review. Nursing and Health Sciences 12: 251–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locke, Edwin A., and Gary P. Latham. 1990. A Theory of Goal Setting and Task Performance. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Macan, Therese H. 1996. Time-management Training: Effects on Time Behaviors, Attitudes, and Job Performance. The Journal of Psychology 130: 229–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackway-Jones, Kevin, Janet Marsden, and Jill Windle. 1997. Emergency Triage: Manchester Triage Group. London: BMJ. [Google Scholar]

- Manz, Charles C. 1986. Self-leadership: Toward an Expanded Theory of Self-influence Processes in Organizations. The Academy of Management Review 11: 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manz, Charles C. 1990. Beyond Self-managing Work Teams: Toward Self-leading Teams in the Workplace. In Research in Organizational Change and Development. Edited by Richard Woodman and William Pasmore. Greenwich: JAI Press, pp. 273–99. [Google Scholar]

- Manz, Charles C. 1991. Developing Self-leaders through SuperLeadership. Supervisory Management 36: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Manz, Charles C. 1992. Mastering Self-Leadership: Empowering Yourself for Personal Excellence. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Manz, Charles C., and C. P. Neck. 2004. Mastering Self-Leadership: Empowering Yourself for Personal Excellence, 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Manz, Charles C., and H. P. Sims, Jr. 1980. Self-management as a Substitute for Leadership: A Social Learning Perspective. Academy of Management Review 5: 361–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manz, Charles C., and H. P. Sims, Jr. 1989. Superleadership: Leading Others to Lead Themselves. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Manz, Charles C., and H. P. Sims, Jr. 1991. Superleadership: Beyond the Myth of Heroic Leadership. Organizational Dynamics 19: 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manz, Charles C., and H. P. Sims, Jr. 2001. The New Superleadership: Leading Others to Lead Themselves. Oakland: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Mathena, Katherine A. 2002. Nursing Manager Leadership Skills. Journal of Nursing Administration 32: 136–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maule, John A., and Anne C. Edland. 1997. Decision Making: Cognitive Models and Explanations. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Maule, John A., Robert J. Hockey, and Larissa Bdzola. 2000. Effects of Time Pressure on Decision-making under Uncertainty: Changes in Affective State and Information Processing Strategy. Acta Psychol 104: 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, Micki. 2005. Self-help, Inc.: Makeover Culture in American Life. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mcmillan, Kristy, Phyllis Butow, Jane Turner, Pasty Yates, Kate White, Sylvie Lambert, Moira Stephens, and Catalina Lawsin. 2016. Burnout and the Provision of Psychosocial Care amongst Australian Cancer Nurses. European Journal of Oncology Nursing 22: 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, Tyebeh, Fatemeh Oskouie, and Forough Rafii. 2012. Nursing Students’ Time Management, Reducing Stress and Gaining Satisfaction: A Grounded Theory Study. Nursing and Health Sciences 14: 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosadeghrad, Ali M. 2013. Occupational Stress and Turnover Intention: Implications for Nursing Management. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 1: 169–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neck, Christopher P., and Annette H. Barnard. 1996. Managing your Mind: What are you Telling Yourself? Educational Leadership 53: 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Neck, Christopher P., and Jeffery D. Houghton. 2006. Two Decades of Self-leadership Theory and Research: Past Developments, Present Trends, and Future Possibilities. Journal of Managerial Psychology 21: 270–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neck, Christopher P., and Charles C. Manz. 1992. Thought Self-leadership: The Impact of Self-talk and Mental Imagery on Performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior 12: 681–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neck, Christopher P., and Charles C. Manz. 1996. Thought Self-leadership: The Impact of Mental Strategies Training on Employee Behavior, Cognition, and Emotion. Journal of Organizational Behavior 17: 445–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neck, Christopher P., Charles C. Manz, and Jeffry Houghton. 2019. Self-Leadership: The Definitive Guide to Personal Excellence, 2nd ed. New York: Sage Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- O’Gara, Geraldine, and Natalie Pattison. 2015. Information and Psychosocial Needs of Families of Patients with Cancer in Critical Care Units. Cancer Nursing Practice 14: 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, John W., James R. Bettman, and Eric J. Johnson. 1993. The Adaptive Decision Maker. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Protzko, John, Claire M. Zedelius, and Jonathan W. Schooler. 2019. Rushing to Appear Virtuous: Time Pressure Increases Social Desirable Responding. Psychological Science 30: 1584–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prussia, Gregory E., Joe S. Anderson, and Charles C. Manz. 1998. Self-leadership and Performance Outcomes: The Mediating Influence of Self-efficacy. Journal of Organizational Behavior 19: 523–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, David G., Alexander Peysakhovich, Gordon T. Kraft-Todd, George E. Newman, Owen Wurzbacher, Martin A. Nowak, and Joshua D. Greene. 2014. Social Heuristics Shape Intuitive Cooperation. Nature Communications 5: 3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, Maria A., Frank Tortorella, and Cynthia St. John. 2010. Improving Psychosocial Care for Improved Health Outcomes. Journal for Healthcare Quality 32: 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roussel, Linda, Patricia L. Thomas, and James L. Harris. 2020. Management and Leadership for Nurse Administrators, 8th ed. Burlington: Jones and Bartlett Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Saintsing, David, Linda M. Gibson, and Anthony Pennington. 2011. The Novice Nurse and Clinical Decision-making: How to Avoid Errors. Journal of Nursing Management 19: 354–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, Elizabeth G. 2014. Front-load your Week and Three Other Stress-busting Time Management Strategies. Available online: http://99u.com/articles/16824/front-load-your-week-3-other-stress-busting-time-management-strategies (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Saunders, Carol, Traci A. Carte, Jon Jasperson, and Brian S. Butler. 2003. Lessons from the Trenches of Metatriangulation Research. Communications of the Association from Information Systems 11: 245–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W. Richard. 1996. The Mandate is still being honored: In Defense of Weber’s Disciples. Administrative Science Quarterly 41: 163–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, Martin E. 1991. Learned Optimism: How to Change Your Mind and Your Life. New York: Random House Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Soleymani, Fatemeh, Arash Rashidian, Rassoul Dinarvand, Abbas Kebriaeezade, Mostafa Hosseini, and Mohammad Abdollahi. 2011. Assessing the Effectiveness and Cost-effectiveness of Audit and Feedback on Physician’s Prescribing Indicators: Study Protocol of a Randomized Controlled Trial with Economic Evaluation. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 20: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Ching I., and Li S. Huang. 2007. Designing Time-limited Cyber Promotions: Effects of Time Limit and Involvement. Cyber Psychology and Behavior 10: 141–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Ching I., Feng Hsio, and Tin Chou. 2010. Nurse-perceived Time Pressure and Patient-perceived Care Quality. Journal of Nursing Management 18: 275–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theorell, Tores, and Robert A. Karasek. 1996. Current Issues Relating to Psychosocial Job Strain and Cardiovascular Disease Research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 1: 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Carl, Nicky Cullum, Dorothy McCaughan, Trevor Sheldon, and Pauline Raynor. 2004. Nurses, Information Use, and Clinical Decision Making: The Real World Potential for Evidence-based Decisions in Nursing. Evidence-Based Nursing 7: 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Carl, Len Dalgleish, Tracy Bucknall, Carole Estabrooks, Alison M. Hutchinson, Kim Fraser, Rien de Vos, Jan Binnekade, Gez Barrett, and Jane Saunders. 2008. The Effects of Time Pressure and Experience on Nurses’ Risk Assessment Decisions: A Signal Detection Analysis. Nursing Research 57: 302–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckett, Anthony, Peta Winters, Fiona Bogossian, and Dip Wood. 2015. Why Nurses are Leaving the Profession…Lack of Support from Managers: What Nurses for an E-cohort Study Said. International Journal of Nursing Practice 21: 359–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Yperen, Nico W., and Tom A. Snijders. 2000. A Multi-level Analysis of the Demands-control Model: Is Stress at Work Determined by Factors at the Group or Individual Level? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 5: 182–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wall, Toby D., Paul R. Jackson, Sharon K. Mullarkety, and Sean K. Parker. 1996. The Demands-control Model of Job Strain: A More Specific Test. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 69: 153–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, Peter B. 1990. Decision Latitude, Job Demands, and Employee Well-being. Work and Stress 4: 285–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warshawsky, Nurs E., and D. S. Havens. 2014. Nurse Manager Job Satisfaction and Intent to Leave. Nursing Economics 32: 32–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Waterworth, Susan. 2003. Time Management Strategies in Nursing Practice. Nursing and Healthcare Management 43: 432–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellens, Benjamin T., and Andrew P. Smith. 2006. Combined Workplace Stressors and Relationship with Mood Physiology, and Performance. Work and Stress 20: 345–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Jia L., and Gary Johns. 1995. Job Scope and Stress. Can Job Scope be Too High? Academy of Management Journal 38: 1288–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziapour, Arash, Alireza Khatony, Faranak Jafari, and Neda Kianipour. 2015. Evaluation of Time Management Behaviors and its Related Factors in the Senior Nurse Managers, Kermanshah-Iran. Global Journal of Health Science 7: 366–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zijlstra, Fred R. H., Robert A. Roe, Anna B. Leonora, and Irene Krediet. 1999. Temporal Factors in Mental Work: Effects of Interrupted Activities. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 72: 163–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goldsby, E.; Goldsby, M.; Neck, C.B.; Neck, C.P. Under Pressure: Time Management, Self-Leadership, and the Nurse Manager. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030038

Goldsby E, Goldsby M, Neck CB, Neck CP. Under Pressure: Time Management, Self-Leadership, and the Nurse Manager. Administrative Sciences. 2020; 10(3):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030038

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoldsby, Elizabeth, Michael Goldsby, Christopher B. Neck, and Christopher P. Neck. 2020. "Under Pressure: Time Management, Self-Leadership, and the Nurse Manager" Administrative Sciences 10, no. 3: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030038

APA StyleGoldsby, E., Goldsby, M., Neck, C. B., & Neck, C. P. (2020). Under Pressure: Time Management, Self-Leadership, and the Nurse Manager. Administrative Sciences, 10(3), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030038