In this chapter, we describe the knowledge intensive activities allocated in Nitra region, innovation delivery of knowledge-intensive ventures in the sample of our survey, and finally, we investigate, how are these knowledge-intensive ventures rooted in rural municipalities, resp. what motivated them to make decision to locate venture in small municipality.

3.1. Characteristics of Knowledge Intensive Activities in Nitra Self-Governing Region

Nitra self-governing region is a NUTS III. region in western Slovakia, with area of 6344 km2, inhabited by 676,672 citizens (Statistical office of Slovak republic, 2019). This Slovak rural region reached population density of 107 inhabitants on 1 km2 in 2019, having just 15 municipalities over 5000 inhabitants and 45% share of population living in urbanized space (Statistical office of Slovak republic, 2019). From 70,264 enterprises located in region in 2019, 25.2% ventures were falling under knowledge intensive sectors. More specifically, 24.1% of entrepreneurs in regional economy can be considered as knowledge-intensive service providers (KIS) and 1.1% as knowledge intensive manufacturers (KIM).

From 2010 to 2019, amount of knowledge intensive activities in region raised by 19.2%, what means, that regional economy is opening to new activities with higher value added. Of course, that would be not only the result of private investments, but possibly also a cause of support from state programs, EU structural funds and programs of Nitra self-governing region provided to private sector in a given time period.

From sectoral perspective, the highest share on knowledge intensive manufacturing in region was recorded in case of manufacture of machinery and equipment (31.48% of KIM), manufacture of electrical equipment (29.15% of KIM) and manufacture of computer, electronic and optical products (17.23% of KIM). In case of knowledge-intensive services in the region, we found to be dominant the sector of professional, scientific and technical activities (58.28% of KIS in the region), sector of information and communication (14.12%) and financial and insurance activities (9.6%).

In

Table 1, we can observe that a majority of knowledge-intensive service providers in the region are established as natural persons or limited liability enterprises, what can be considered as logical in case of service provision. However, the fact that 40.8% of knowledge intensive manufacturers with a legal form of natural person shows that even without or with minimal number of employees, natural persons can deliver knowledge intensive products.

Most knowledge intensive manufacturers are still established as limited liability companies, what is connected with very small proportion of small, medium and large knowledge intensive enterprises in the region, as showed in

Table 2. Up to 98.5% of knowledge-intensive service providers and 85% knowledge-intensive manufacturers fall under category of micro enterprise if we define the size categories of entrepreneurship by employment. However, we can still observe higher shares of knowledge intensive manufacturers in size categories of small (8.3%), medium (4.27%) and large enterprises (2.46%) in comparison with knowledge intensive services.

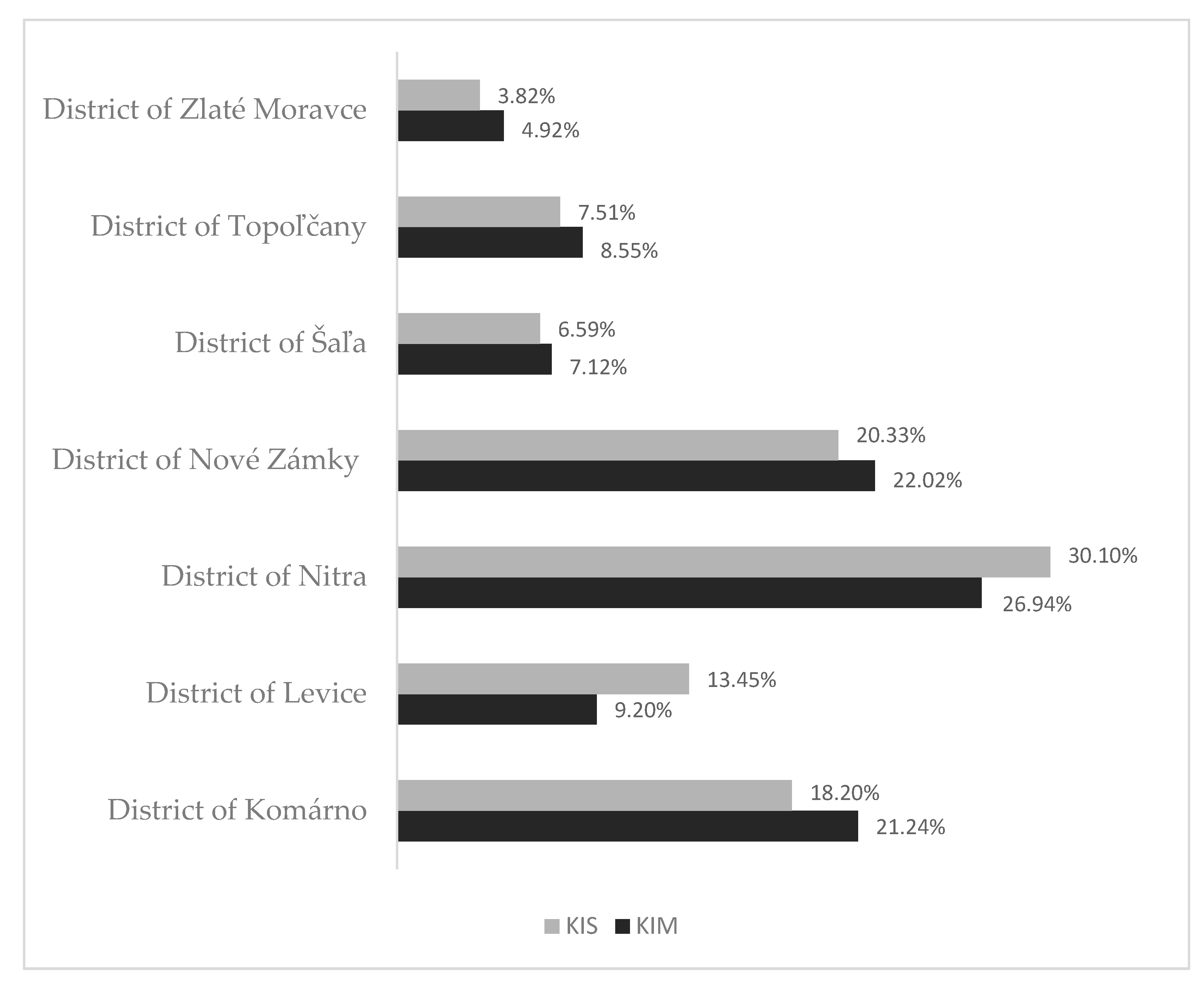

Knowledge intensive activities are unequally distributed in region. As expected, the highest share of knowledge intensive ventures was recorded in Nitra district, where regional center—city of Nitra is allocated. The allocation of the rest of the knowledge intensive ventures can be considered as surprising, as almost half of these ventures reside in southern districts of Nové Zámky and Komárno, which were traditionally agrarian districts lying in a hearth of Danuban Lowland, with a high share of very fertile soils.

On the other hand, we can see very small share of knowledge intensive activity in districts of Zlaté Moravce and Topoľčany, that are neighboring with Nitra district from the north and west, what can be considered as troubling for balanced development of the region. As we can see in

Figure 1, if we would like to compare the distribution of knowledge-intensive services and knowledge-intensive manufacturing, we can find the same localization pattern.

3.2. A Brief Characteristic of the Sample of Our Survey

From 69 responded knowledge-intensive, small and medium sized ventures allocated in municipalities below 5000 inhabitants, 14 responded on call to participate on in-depth survey of their innovation activities. In all tables in the next section, we summarize the information about innovation performance of the respondents in table, where respondents are listed from no. 1 to no. 14, to keep information split to several interconnected tables.

Table 3 provides basic characteristic of our 14 respondents from knowledge-intensive sectors. Up to 6 of 14 of these ventures are located in southern districts of the region, what follows distribution of all knowledge-intensive activities presented in

Figure 1. We can see that from year of establishment perspective, the sample is very saturated, as establishment date range from 1992 to 2018.

Thus, we can observe and compare innovation performance of both well-established ventures and relatively new startups in regional economy. From employment point of view, 10 of 14 enterprises falls into category of small enterprise and 4 to category of medium sized enterprise. In average, 24% of employees of these ventures have tertiary education, while 3 of them declare 50% and more have higher education, and only 4 of investigated enterprises have less than 10% of employees with tertiary degree. While none of responded ventures produce products or provide services having zero university-educated employees, we support general assumption, that business in knowledge-intensive sector is considerably requiring high-quality human capital.

The sectoral distribution of survey respondents is also relatively varied: 4 industrial companies, 2 companies from the health and social assistance sector, 2 companies from the sector of professional, scientific and technical activities, 2 companies from the administration and support services sector and 1 company from the sectors: information and communication technology; agriculture; culture, arts and recreation; and the “other” took part in the survey.

3.3. Results of the Innovation Monitor

In this chapter, we would like to summarize the results of innovation monitor. With such a small sample, it would be relatively easy to expect, that none of survey respondents delivered innovation in recent three years. However, we found that 7 of 14 respondents delivered innovation of its products and services, 2 of 14 delivered process innovation and 4 of 14 marketing innovation. An overview of different kinds of innovation delivery in case of our 14 respondents is presented in

Table 4. Up to 5 of 14 participating knowledge intensive ventures brought a combination of these kinds of innovation. Before we start to describe these innovation actions, we need to fully understand named types of innovation, as described by

Eurostat (

2020).

A product innovation is the launch of a new or significantly improved product or service with respect to its capabilities, user-friendliness, components or subsystems. They must be new to the company, but they do not have to be “new” to the market. Process innovation is the introduction of a new or significantly improved production process, distribution method or support activity in the production of goods or provision of services. Marketing innovation is the implementation of a new marketing concept or strategy that differs significantly from the company’s existing marketing methods and has not been used before (

Eurostat 2020).

In case of both product (service), process and marketing innovation, we asked surveyed knowledge intensive ventures to briefly describe the innovation itself, its nature, level of originality and level of market-novelty. These information for innovators of products and service in the sample is summarized in

Table 5.

Between 7 innovations identified in this category, 5 were new services and 2 new products. The rural environment was suitable for the localization of a knowledge-intensive company in the field of health care services, which brought a new treatment procedure to a small village in the district of Topoľčany, specifically the treatment of the body by neutralizing some negative energy impulses by bioresonance method. The company identifies this service as an original innovation, but it is new at the level of the regional market. In this case, we would rather consider it as an adapted innovation, as this technology can be widespread abroad and in Slovakia in other regions - thus, trying to “look good” when completing a questionnaire can sometimes lead to a distortion of the reality in the results.

An example of a technical innovation is the novel service of company no. 7, which is located in the district of Nitra. Enterprise reallocated to rural settlement, even though it is a technically intensive company, which in the past 3 years has devised a way to provide a service in the field of cleaning industrial machines using ultrasonic waves for the automotive industry. This decision to move out of the Nitra city was mainly connected with expectation of reduced costs (available land, land price, labor costs in case of several job positions). This company stated that this innovation can be considered a “global” new, in-house innovation, which they originally developed through their own development, in order to provide novel services mainly to the automotive industry located in the Nitra Industrial Park.

We found a similar localization intent in the case of company no. 8, which was similarly located in the rural village in the district of Nitra and provide services mainly to industry in city of Nitra. This company delivered innovative service—since 2019 they can provide more technically advanced sheet metal processing services to consumers through the purchase of new technology based on the use of laser plasma. This, as they say, allows the company to process sheet metal in new ways and thus innovation increased their competitiveness. They created this innovative service without imitation; however, it can be still considered as novel only on regional market.

Company no. 9 is an example of the fact, that relatively common services in urban areas can be still novel in the rural regions, and thus, to be an opportunity for businesses in rural. In recent years, the company has introduced 12G Internet through the purchase of the necessary technology and the construction of additional television transmitters in the southern part of the region, bringing high-quality Internet to many villages where it was missing aspect of technical infrastructure. Thus, the entrepreneur correctly states in the survey that this is an adopted innovation that is new on the regional market.

Respondent no. 10 takes advantage of the opportunities arising from the agrarian nature of the region. Thanks to new technologies, it can design and manufacture more innovative conveyors for postharvest cereal storage lines. The company is located in the south of the region, what results in synergistic effects with the agricultural companies with which it cooperates and to which they supply. The result of innovation process are therefore new products, conveyors, although it must be said that the company designs them, and this innovation allows them to design more advanced types. As the essence is again the acquisition of technology and procedures that exists, the company perceives it as an adapted innovation and they also expressed that it is new in the regional market.

Today, much-needed organic products can be developed in rural regions with rich natural potential, quality soil and suitable climatic conditions. This is also the case of our company, no. 12, which thanks to the regional suppliers, produce innovative organic products. In the past 3 years, this enterprise has brought product innovations in the form of the development of a new generation of nutraceuticals, cosmeceuticals and medical drugs of natural origin. Despite the fact that the company operates in the village, the management believe that these are original products that are not adapted and are novel in its nature on the worldwide market.

Moreover, the last identified case of innovation is related to short supply chains on the line: farmer–food industry–final seller–consumer. The farm located in the Nitra district participated on a joint innovative product with other actors in the supply chain—a novel application to trace the origin and method of meat processing. Such innovation in the regional market can bring significant growth in competitiveness for all involved stakeholders. However, it is an even more interesting example because it stands on the border between product innovation and marketing innovation. Such applications are already relatively “basic” in western Europe; however, we still know only about several cases in Slovakia. Thus, enterprise considered it as “innovation created in partnership”, novel on regional market.

We also wanted to compare investments into innovation and expected profit.

Table 6 displays the shares on profit in case of 7 knowledge-intensive ventures that was invested into development and introduction of innovation on the market linked with expectation of an increase in profit due to innovation in the horizon of 3 years. Several innovations, as, e.g., meat tracking application, new technological approach of sheet metal processing or use of new types of conveyors for the design of postharvest lines for cereal storage are expected by entrepreneurs to have very small impact on profit generation. this means, that innovation delivery cannot be perceived only from profit generation perspective. As this result was expected, we investigate motives for decisions to innovate in the next chapter. However, for example respondent no. 7 expect high level on returns from development of new machinery for cleaning of industrial machines, using the ultrasonic waves—thus motivation for innovation can be differentiated according to prior need of given entrepreneur. In certain cases, main driver is the profit, in another cases rather factors connected with competitiveness, prestige and fighting local challenges.

Table 7 presents information about networking directly connected with production of described innovation in investigated ventures. First, we got answer on question, whether it is possible to deliver innovation in rural areas without networking with other firms. Every innovative knowledge-intensive firm in a sample declare, that cooperated on different stages of innovation process with other actors of private sector. We can also observe, that in several cases the academic sector and private R&D entities can stimulate innovation dynamics in private firms. In the regional city seat of Nitra, two universities are allocated, covering majority of research areas in both social and life sciences.

Thus, regional economy can benefit from knowledge diffusion and spill-overs from academic public research. However, we also found a case of cooperation with third sector, regional government and counselling institutions and incubator. The non-profit sector has long been underestimated in terms of its power to support broad range of processes in the private sector enterprises. Even the academic community still does not fully perceive diversity of activities, ability to provide education and support to entrepreneurs or quality of human capital and new ideas accumulated in this sector entities. Innovation-based networking with regional government is also expected result, as regional government in Nitra region is in Slovak conditions considered to be leader in development of cooperation and innovative programs for the private sector entities.

We found only two cases of more “basic” process innovation in our sample. We assume that this may be due to the fact that it is more difficult to understand the essence of process innovation for a responded entrepreneur. As can be seen in

Table 8, a company no. 4 in the healthcare sector in the municipality within the Topoľčany district also declares process innovation associated with employee training and the introduction of a system for using new technology for medical treatment in practice. We can expect entrepreneurs to consider process innovation as original if new processes are the result of internal planning.

Here we can see the thin line between process and product innovation, mainly in case or service provision. The second case is a company no. 5 established to run the organization of a festival in the district of Nové Zámky—the identified process innovation was in the nature of an improved method of communication. In this company, a new organization of the team work was introduced using the modern communication tool Trello and the online planning procedure, which enabled foreign partners to become to be the part of the organizational team. This can be considered as a very interesting example, where the use of ICT tools that are new in rural space, enabled the introduction of new processes. However, we have not gained many examples of process innovations, we believe that their main purpose is not only to increase the efficiency of production processes, but also the organization of work, teams, production sites, trainings and corporate culture.

Table 9 provides an overview of marketing innovations. Up to three of them had the character of new models of product promotion. In the first case (company no. 5) a new website, logo and web design were introduced. This type of innovation can be considered as relatively common. Company no. 7 has brought a new e-mail notification system with original visuals and also has invested in minor design changes in various promotional materials. In the case of company 9. new “bundles” of combined services were introduced as the company started to offer new web hosting and server hosting services. Thus, they rather decided to integrate these services into new bundles with those previously provided, rather than operating them separately. Last company that stated marketing innovation delivery in recent three years—company no. 13, was a farm located in the Nitra district that also brought a product innovation in form of tracking application for food origin.

This farmer also decided to, initiate the organization of a small farmers’ market in the village where the farm is located, to make the promo for year-round sale of fresh meat directly from the yard. Thus, marketing innovations appear to be logically linked to novel products and services.

3.4. Knowledge Intensive Entrepreneurship in Rural Space

In the previous chapter, we described innovations that were delivered in recent three years by responded knowledge-intensive ventures in Nitra region. Now, we would like to put forward a question of localization factors and motivation to allocate the knowledge-intensive business in rural space. We investigate, why the investigated rural enterprises innovated and how these rural knowledge-intensive enterprises located in villages organize the cooperative networks.

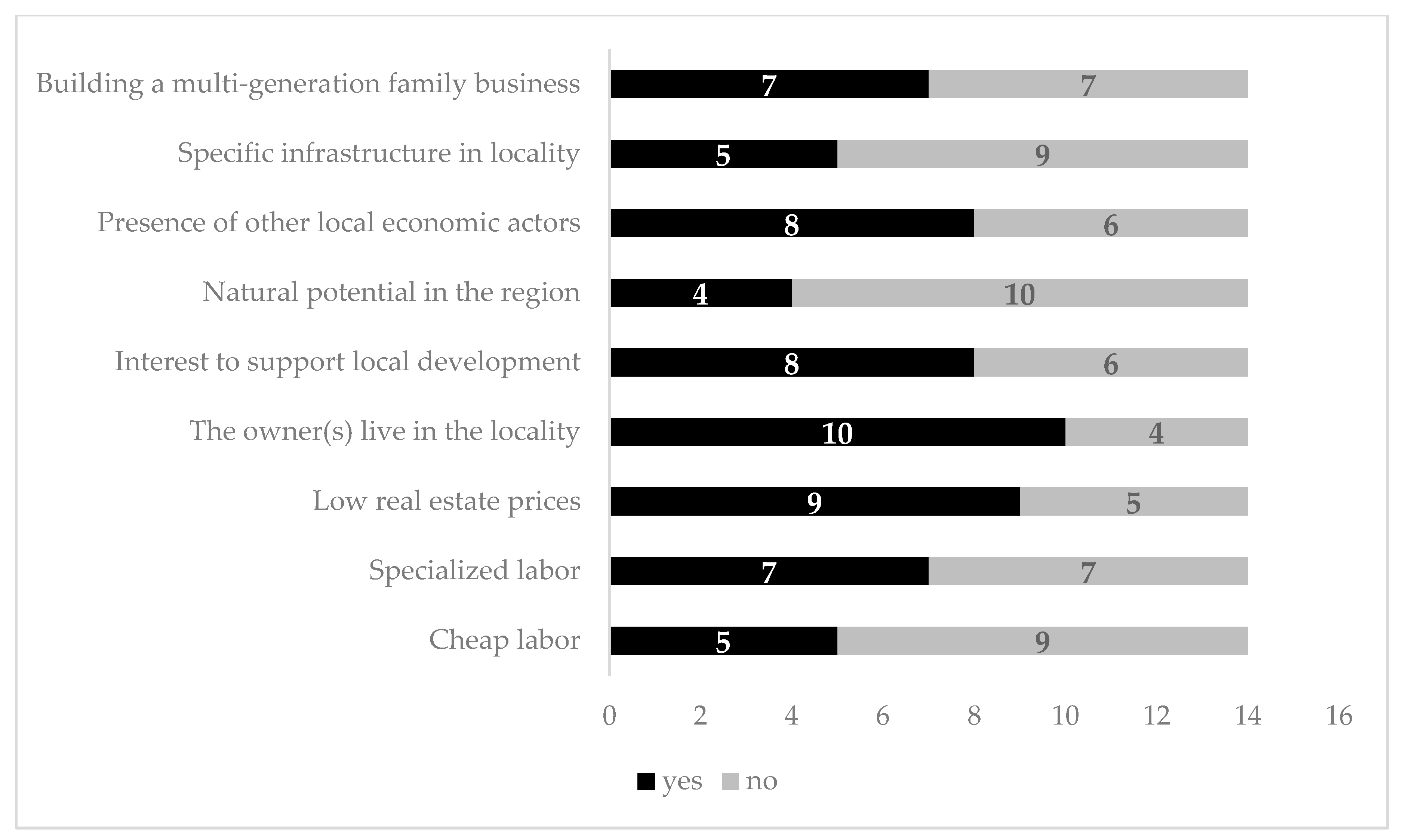

Our main assumption was met, as 10 of 14 responded enterprises allocated their knowledge-intensive business in rural village, as they wanted to run a business in locality of residence (

Figure 2). Thus, the first hypothesis, that we could formulate is, that localization of educated human capital in rural areas can raise the number of knowledge intensive ventures and innovation dynamics in rural areas. As we expected, based on previous research (see, e.g.,

Martyniuk 2016;

Peráček 2019;

Vilčeková et al. 2018), family conditions and attitudes towards entrepreneurship influence localization decisions of small and medium enterprises.

A half of the respondents found their enterprise on the basis of multi-generation family business. Interest to hand down the business to children ň also affect creation of KIF ventures in rural areas and gives to these businesses’ certain expectation of sustainability. Up to 8 of 14 respondents consider an interest to support local development as driver of their business activities—thus, we can hypothesize, that rural enterprises care for over-all development of given rural locality due to informal relations with development actors and rest of the population. The impact of relations with another businesses in given rural area is declared also by fact, that 8 of 14 responded knowledge-intensive ventures consider as important precondition of running business, the presence of other economic agents in the municipality.

Several enterprises consider cheap labor, specialized labor and mainly low real estate costs (9 of 14 respondents) to be important localization factor. We still expected these factors to play more intensive role in comparison with previously described cost-free-related determinants. Thus, in our sample we can observe certain innovation activity not only in municipalities in nodal region of the city, but also in those peripheral. Even if knowledge intensive ventures in rural settlements can be found as the response to local opportunities, family needs and locality problems, there is still possible to observe their need to build networks with actors allocated in urbanized space.

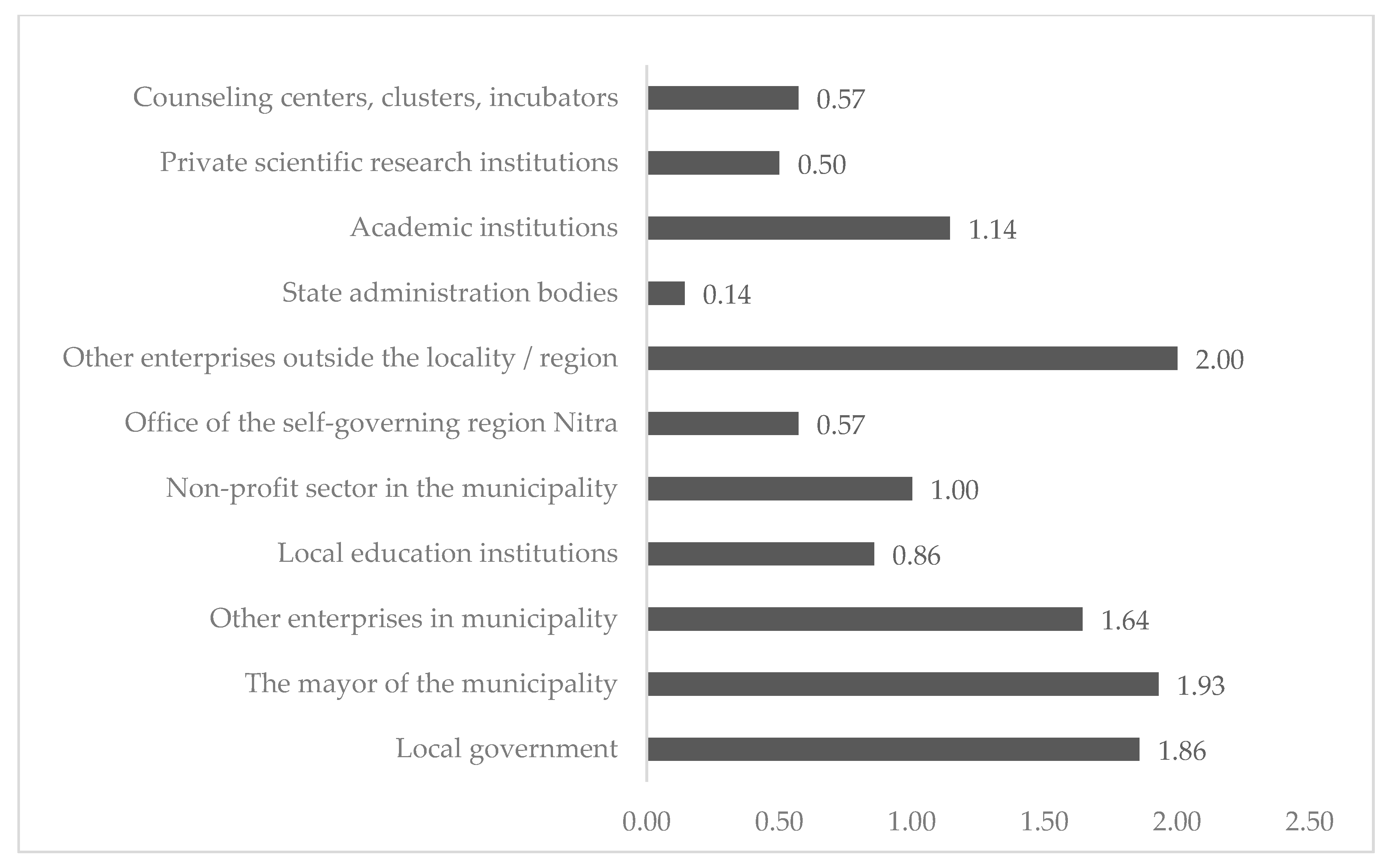

In the next part of this chapter, we interpret the average importance of cooperation with individual types of actors. Each company that participated in the survey was asked to determine the importance of cooperation with a given type of actor on a scale from 0—no importance, to 3—key importance. In this case, we ask about maintaining cooperation with these actors in general—not about the emergence of their specific innovations as in the previous chapter. In

Figure 3, we display the values of the average importance of cooperation with a given type of actors for 14 respondent knowledge-intensive companies. The highest average score was recorded in case of the cooperation with other companies outside the locality, resp. region. Thus, we can construct the hypothesis that doing business in knowledge-intensive industries in rural municipalities requires networking inside the private sector at a distance. However, some companies still use the purchase of basic inputs from local companies (average score 1.64).

We consider the results for networking with the local government, represented by the municipal council and the mayor, to be extremely important. Local government achieved an average significance of 1.86, which means that although knowledge-intensive ventures do not network too much at the local level (rather at greater distances), every enterprise can handle some matters (land plots, building permits, materials, common projects, etc.) trough informal cooperation with municipal self-government. The personal contact with the mayor allows these companies to settle their affairs even more easily in Slovak conditions, as contact with the mayor received an even higher average score, up to 1.93.

Once again, we have shown that the academic sector and the private scientific entities have an impact on the development of knowledge-intensive activities. There is also a certain dynamics of cooperation between rural knowledge-intensive companies and the non-profit sector (we assume that especially in the level of counseling and educational activities) and also between these companies and education in the municipality, although we assume, that cooperation with local schools is not connected with production of products and services by KIF (e.g., rental of premises or catering).

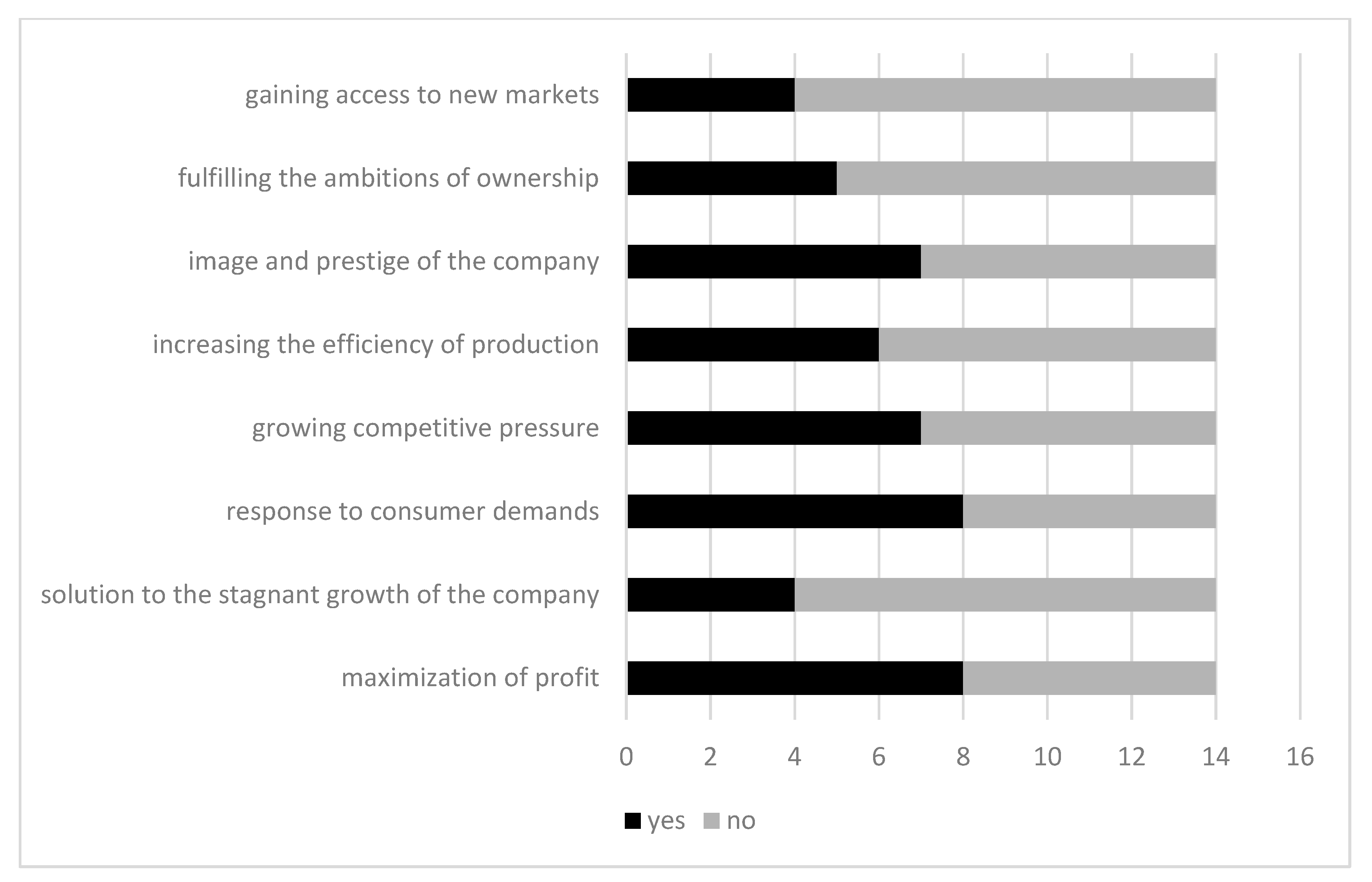

Figure 4 shows the motives for investing in innovation by the researched knowledge-intensive companies. As many as 8 out of 14 ventures consider maximizing profit as the main reason for investing in innovation, the same number of companies consider the cost of innovation to be a necessary prerequisite for keeping their products sufficiently attractive to consumers. Interest to respond on the competitive pressure led 7 of 14 investigated KIF to innovate. A similar share of ventures wanted to improve the company’s image.

Thus, innovation not only pursued financial benefits and cost savings, but also non-financial benefits in form of brand and company image (which is logical especially in case of marketing innovations). Up to 6 out of 14 respondents was driven to innovate in order to increase the efficiency of production, resp. service provision. In some cases (4 of 14 ventures), the fulfillment of long-term goals can be monitored through innovations, resp. sometimes the innovation can represent the fulfillment of the ambitions of company ownership. Only 4 companies tried to gain access to new markets through innovation, which can definitely be considered a specific feature of knowledge-intensive business in the rural space.