Abstract

Forest fertilization is commonly used to enhance tree growth and carbon (C) sequestration, especially in nutrient-poor boreal forests. However, it also poses several environmental risks, including shifting ground vegetation community composition and a reduction in species diversity. This study evaluated how ground vegetation species composition responded to forest fertilization with ammonium nitrate and wood ash across forest stands with varying dominant tree species, age groups, and site types. Ground vegetation assessment was performed during the one to three years following fertilizer application. We conducted detrended correspondence analysis (DCA) to examine compositional differences in ground vegetation between control and fertilized plots and to identify ecological factors underlying dataset variation. Ordination was based on species percentage cover data, with soil chemical parameters and stand inventory metrics providing environmental context for interpreting the results. Additionally, permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was conducted to evaluate whether vegetation composition differed across the experimental design factors. Forest site type and stand developmental stage were the primary drivers of understory composition, with fertilization effects being statistically significant but ecologically modest (0.9–14.2% of variation explained by fertilization in PERMANOVAs). Wood ash treatments showed greater compositional divergence from controls than ammonium nitrate alone. Fertilization effects varied with stand age, with significant responses in middle-aged and pre-mature Norway spruce stands but not in young stands. Despite modest compositional changes, fertilization achieved substantial productivity gains (volume increment increases of 20–60% compared to controls depending on species and site conditions), suggesting that moderate fertilization for timber production can be implemented without dramatic changes to ground vegetation. These results reflect short-term responses (1–3 years after fertilization) and should therefore be interpreted as early ecological effects rather than long-term ecosystem changes.

1. Introduction

Growing demand for timber and climate-focused solutions has led forest managers to fertilize nutrient-limited ecosystems to increase productivity. Forest fertilization is most common in Fennoscandia and North America. Within North America, it is particularly prevalent in Canada and in parts of the United States (e.g., the Pacific Northwest and the Southeast). Nitrogen (N) has traditionally been the primary fertilizer used, but wood ash is increasingly applied in Finland, Sweden, and parts of Canada to supply phosphorus (P), potassium (K), and other base cations, as well as to raise soil pH [1,2]. When carried out judiciously, fertilization can speed up forest stand development, help certain tree species regenerate more successfully, and store larger amounts of carbon (C) [3,4,5]. While this practice indeed increases growth and economic returns, it comes with considerable ecological trade-offs. Forests may experience changes in species composition, biodiversity decline, N leaching into soils and waterways, disruption of microbial and fungal communities and increased susceptibility to certain pests and diseases [6,7,8,9,10].

Understorey plants are among the first to respond when forests are fertilized. Forest vegetation is vertically structured into distinct layers, with ground vegetation (shrub, herb, and moss layers) playing a critical role in nutrient cycling, C sequestration, and habitat provision [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. The herb (field) layer, composed mainly of herbaceous vascular plants, dwarf shrubs, and tree seedlings, exhibits high phenological flexibility compared to woody vegetation [16,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Occupying a transitional position between the moss and shrub layers, it influences light interception and tree establishment. Bryophytes differ fundamentally from vascular plants by absorbing nutrients and water directly through their surface and contribute to ecosystem functioning through N fixation, regulation of decomposition rates, and soil moisture retention [25,26,27,28]. Their sensitivity to environmental conditions makes bryophyte communities particularly informative indicators of ecosystem responses to forest management practices.

Herbaceous plants respond variably to nutrient enrichment, especially N, generally increasing productivity but with species-specific differences. Graminoids often show rapid biomass increases, while some forbs may decline due to increased competition for light [29,30]. Shade-tolerant species adapted to low-nutrient conditions may be particularly vulnerable to displacement by more aggressive colonizers [29]. The timing of fertilization relative to growing seasons can significantly influence herb layer responses, with spring applications often producing stronger effects than late-season treatments [31,32]. Some herb species extend their growing seasons or advance flowering times in response to elevated nutrient availability, affecting reproductive success and competitive dynamics within the herb layer [33,34]. Nutrient-enriched plants also produce litter with altered C:N ratios, affecting decomposition rates and nutrient cycling in subsequent years [31].

Bryophyte responses to fertilization may involve both direct and indirect mechanisms. Direct effects of nutrient addition include ammonium toxicity, causing osmotic stress and tissue browning, while wood ash applications can result in alkaline burns [35,36]. Excess N may also disrupt C metabolism, impairing physiological processes and growth [37,38]. While high N inputs can be harmful, moderate fertilization has stimulated bryophyte growth in some cases, with biomass increases observed up to certain N thresholds [39,40]. N addition may also indirectly affect bryophyte communities by favoring taller, fast-growing vascular plants, thereby intensifying competition for light and space and creating less favorable conditions for bryophyte establishment [41]. Despite their tolerance of low light, many bryophyte species establish most successfully in microsites with reduced vascular plant cover, such as patches of bare ground, disturbed soil, or vegetation gaps [42,43].

This study aimed to evaluate the impact of ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3) and wood ash fertilization on species composition in hemiboreal forest ecosystems in Latvia. Additionally, it sought to identify key environmental factors that influence species composition in control and fertilized plots. We hypothesized that the compositional response to fertilization would be context-dependent in several ways. First, we expected fertilization effects to vary with forest site type and stand developmental stage. Second, we predicted that wood ash would produce different compositional shifts than NH4NO3 due to combined pH and nutrient effects rather than nitrogen enrichment alone. Third, we expected herb and bryophyte species to show different compositional responses to fertilization, reflecting their distinct physiological traits and associations with soil chemical gradients. Species richness and diversity patterns from these plots were examined in our earlier work [44], whereas here we focus on compositional changes. Given the critical role of understorey vegetation, understanding how fertilization alters species communities is essential for developing sustainable management strategies in these transitional forest ecosystems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

This study examined ground vegetation species composition in 20 forest stands across Latvia. These stands encompass three major forest site types (dry upland forests, forests with drained mineral soils, and forests with drained organic soils) dominated by Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.), Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) H. Karst.), and silver birch (Betula pendula Roth). Stand ages range from 25–95 years, classified into developmental stages: young stands (1–40 years for conifers, 1–20 years for birch), middle-aged stands (41–80 years for pine, 41–60 years for spruce, 21–60 years for birch), and pre-mature stands (81–100 years for pine, 61–80 years for spruce, 61–70 years for birch). Stand age group definitions follow traditional Latvian forestry classifications [45,46]. Complete site descriptions are provided in Petaja et al. [44].

Prior to fertilization, all stands underwent commercial thinning to optimize growing conditions. Fertilizers were applied between December 2016 and July 2017 according to site-specific management considerations. Nitrogen fertilization with ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3) was the most common treatment and was applied at 0.44 t ha−1 to increase N availability across a wide range of stands. Wood ash (3 t ha−1), sourced from Fortum and Latgran pellet factories in Latvia, was applied either alone or in combination with NH4NO3 in site types where base cation depletion or soil acidification was considered more likely. Vegetation plots were available only for a subset of treated stands; therefore, not all fertilized areas were represented in the vegetation dataset. Complete treatment specifications are provided in [44].

Circular plots (500 m2) were established in stands where fertilizer was applied mechanically in linear strips, while square plots (400 m2) were used where manual application was required due to accessibility constraints. Plot geometry differences were dictated by fertilizer application methods; however, given the spatial scale of tree growth responses and the plot sizes used, plot shape is not expected to affect estimates of tree increment. Ground vegetation, which responds at finer spatial scales, was assessed separately using subplots within the tree plots, as described below. Buffer zones surrounded all plots to minimize edge effects from adjacent treatments. Complete plot design specifications are provided in [44].

Ground vegetation assessments were conducted within a one- to three-year period following fertilization. Survey methodology, sample plot layouts, and species lists categorized by dominant tree species and forest site type are detailed in [44]. Species abundance within plots was quantified by visually estimating projective cover at the species level across two vegetation layers: the moss layer, dominated by bryophytes and lichens, and the herb layer, comprising vascular plants together with shrubs and tree seedlings not exceeding 50 cm in height.

Forest stand inventory characteristics were determined according to ICP Forests methodology for Level II plots [47]. Stand structure was characterized using standard inventory variables, including tree diameter at breast height (DBH), tree height, and stand basal area, which were summarized at the plot level and used as explanatory variables in the analyses.

Soil sampling and analysis methods followed the ICP Forests forest health monitoring protocols [48,49]. Soil samples were collected within each plot at locations avoiding tree stems, disturbed microsites, and animal burrows. Organic horizons (O/H layer) were sampled separately after removal of surface litter, and mineral soil samples were collected from the upper 0–20 cm following removal of the organic layer. At each plot, a minimum of five subsamples were taken using a soil auger and combined into a single composite sample to account for within-plot spatial heterogeneity. Soil samples were air-dried at ≤40 °C, roots and coarse fragments (>2 mm) were removed, and the <2 mm fraction was used for chemical analyses. A summary of the analytical methods used is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Soil chemical analysis methods and instrumentation.

2.2. Data Analysis

To assess differences in vegetation species composition between control and fertilized plots and identify ecological factors explaining variation in the dataset, detrended correspondence analysis (DCA) was performed. Ordination axes and plots were derived from species percentage cover data, with environmental variables used to interpret the results, including soil chemical parameters (total carbon—Ctot, total nitrogen—Ntot, K, P, Ca, Mg, and pH) and stand inventory metrics (average tree height—H, average tree diameter at breast height—D, average stand basal area—G). The first two DCA axes (DCA1 and DCA2) were selected for visualization based on their highest eigenvalues, indicating they best represent the main gradients in species composition. Eigenvalues and axis lengths for each ordination are provided in Table A1. All recorded species were included in the DCA calculations. For clarity in visualization, only species with stronger loadings on the ordination axes (i.e., located further from the center of the ordination space) are shown in the diagrams, while species near the origin were omitted from figures but retained in analyses. Species acronyms used in ordination diagrams are listed in Table A2. Results are presented both as species-plot ordinations and with significant environmental variables overlaid (p < 0.05). Soil chemical parameters and stand characteristics used as environmental vectors are detailed in Table A3 and Table A4, respectively.

Additionally, a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) based on a distance matrix (adonis) was conducted to evaluate whether vegetation composition differed across forest site types, treatments, and stand age groups. When a significant effect was found for factors with three classes or for interactions, pairwise PERMANOVA tests between individual class combinations were performed. Due to experimental design limitations, it was not possible to construct a single model including all dominant tree species, age groups, forest site types, and treatments simultaneously. Therefore, each dominant tree species was analyzed separately, with multiple models created for each species to explore different combinations of factors and their levels. The PERMANOVA model designs and corresponding factor levels for each tree species are presented in Table 2, following a similar analytical structure as used for GLMMs and LMMs in [44].

Table 2.

PERMANOVA model designs showing combinations of treatments, forest site types, and stand age groups tested for each dominant tree species. SB—silver birch, NS—Norway spruce, SP—Scots pine, DM—forests with drained mineral soils, DO—forests with drained organic soils, DU—dry upland forests.

All analyses were conducted in R version 4.4.0 [56]. DCA and PERMANOVA were conducted through the vegan package [57], and pairwise PERMANOVA tests utilized the jakR package [58].

3. Results

3.1. Silver Birch Stands

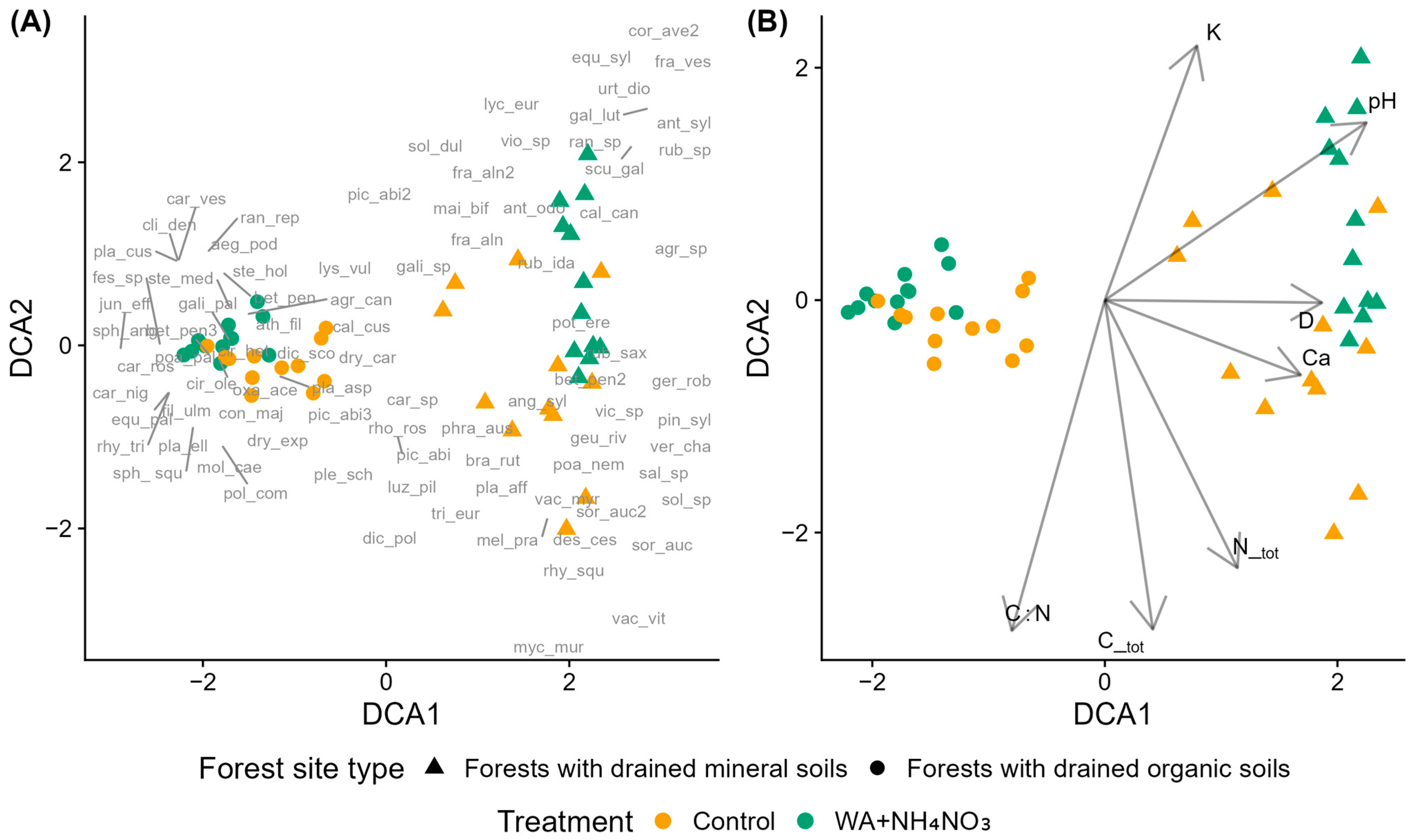

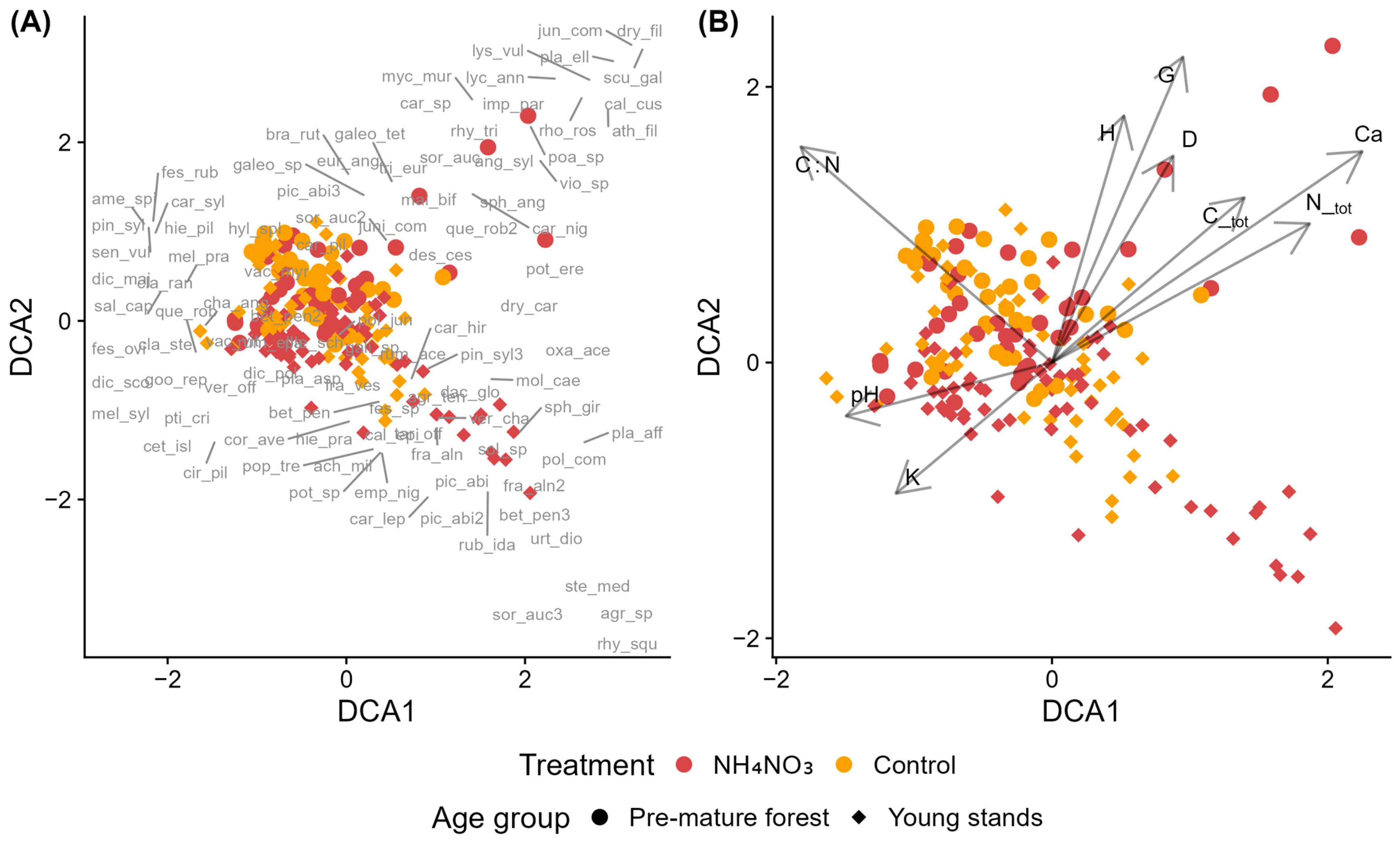

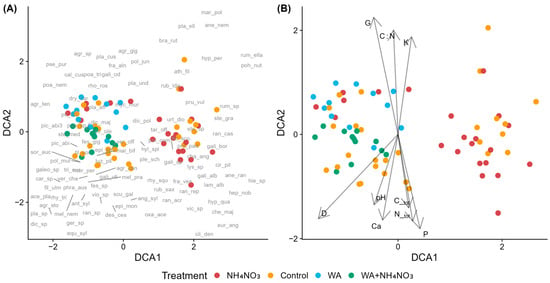

Sample plots of middle-aged silver birch stands clustered distinctly by forest site type along DCA1, separating forests with drained organic soils and forests with drained mineral soils (Figure 1A,B). Treatments showed weaker effects, with some overlap between control and fertilized plots in the case of forests with drained organic soils.

Figure 1.

Detrended Correspondence Analysis (DCA) of species composition in control and fertilized plots in middle-aged silver birch stands across forest site types. Fertilized plots received wood ash (WA) and ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3) co-applied. (A) Sample plots (symbols indicate treatment and forest site type) with species acronyms shown at their optimum positions (full names in Table A2). (B) Sample plots with environmental vectors: D—mean tree diameter at breast height, C_tot—total soil carbon, N_tot—total soil nitrogen, C:N—carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, K—potassium, Ca—calcium, and pH—soil pH (CaCl2).

Hygrophilous species (EIV F ≥ 6) were common across both site types. In forests with drained organic soils, fertilized plots were associated with species exhibiting moderate to high N requirements (EIV N ≥ 5), whereas species with lower N requirements occurred predominantly in control plots. An exception was Poa palustris (EIV N = 8), which also occurred in control plots. In forests with drained mineral soils, fertilized plots were characterized by species with high nitrogen requirements (high EIV N), while control plots were dominated by species indicative of lower N availability and lower reaction values (low EIV N and R).

Moss species showed distinct distribution patterns across forest site types and treatments. In forests with drained mineral soils, Rhytidiadelphus squarrosus, Brachythecium rutabulum, and Plagiomnium affine were associated with control plots. In forests with drained organic soils, control plots were characterized by Pleurozium schreberi, Hylocomnium splendens, Plagiochila asplenioides, Polytrichum commune, Plagiomnium ellipticum, Dicranum scoparium, and Sphagnum squarrosum, while fertilized plots were associated with Climacium dendroides, Sphagnum angustifolium, and Plagiomnium cuspidatum. Rhodobryum roseum and Dicranum polysetum were positioned centrally in the ordination, occurring near control plots of both site types.

Seven environmental variables had significant correlations with DCA axes (Figure 1B). Ca, Ctot, and Ntot correlated positively with DCA1 and negatively with DCA2, C:N correlated negatively with both DCA1 and DCA2, K and pH correlated positively with both DCA1 and DCA2, while D correlated positively with DCA1 and showed no correlation with DCA2.

Results of the permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) indicate that species composition was significantly influenced by both treatment and forest site type, as well as their interaction (Table S1). Among these factors, forest site type has the strongest effect on species composition, explaining 36.65% of the total variation. Treatment accounts for a considerably smaller proportion of variation (6.56%), while the interaction between the two factors explains an even smaller yet statistically significant portion (3.6%). Notably, more than half (53.22%) of the total variation remained unexplained by the model.

Pairwise comparisons showed statistically significant differences in species composition across all treatment combinations (Table S2). The largest differences were observed between forest site types, whereas differences between control and fertilized plots within the same site type were generally smaller. The effect of fertilization was stronger in forests with drained organic soils compared to forests with drained mineral soils.

3.2. Norway Spruce Stands

3.2.1. Young Norway Spruce Stands Across Different Forest Site Types

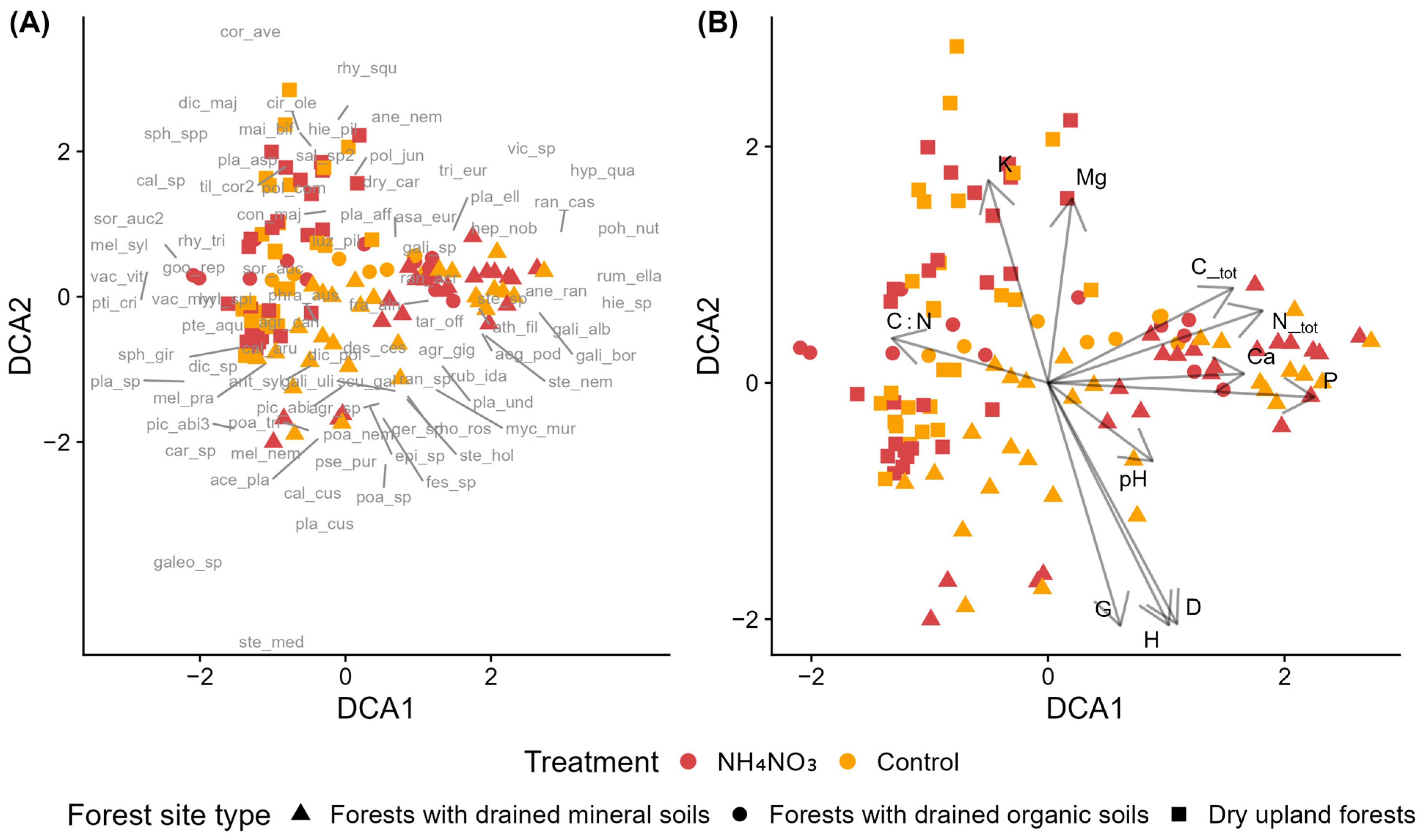

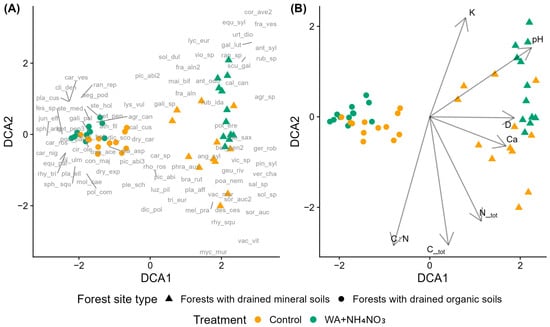

Regarding young Norway spruce stands, sample plots showed grouping by forest site type in the DCA ordination, although clusters were not sharply separated (Figure 2A,B). Control and fertilized plots did not form clearly distinct groups, with considerable overlap between treatments.

Figure 2.

Detrended Correspondence Analysis (DCA) of species composition in control and ammonium nitrate-fertilized (NH4NO3)) plots in young Norway spruce stands across forest site types. (A) Sample plots (symbols indicate treatment and forest site type) with species acronyms shown at their optimum positions (full names in Table A2). (B) Sample plots with environmental vectors: D—mean tree diameter at breast height, G—stand basal area, H—mean tree height, C_tot—total soil carbon, N_tot—total soil nitrogen, C:N—carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, K—potassium, Ca—calcium, P—phosphorus, Mg—magnesium, and pH—soil pH (CaCl2).

Species associated with dry upland forest plots included Maianthemum bifolium, Convallaria majalis, Dryopteris carthusiana (EIV N = 3–4), and bryophytes including Dicranum spp., Polytrichum spp., and Rhytidiadelphus triquetrus (EIV F = 4–7), and Sphagnum spp. (EIV F = 7–8). Plots representing forests with drained mineral soils were associated with N-demanding species (EIV N ≥ 6), including Lamium album, Chamaenerion angustifolium, Aegopodium podagraria, Rubus idaeus, and Stellaria nemorum. These plots also contained moisture-demanding taxa (EIV F > 5), such as Galium uliginosum, Anthriscus sylvestris, Scutellaria galericulata, and Plagiomnium undulatum. Forests with drained organic soils did not exhibit a distinct species assemblage, as their composition overlapped extensively with other site types in ordination space.

The C:N ratio was negatively correlated with DCA1 and positively with DCA2, while Ntot, Ctot, P, and Ca concentrations showed positive correlations with DCA1. K and Mg were positively correlated with DCA2, with K also showing a slight negative correlation with DCA1. Stand structural variables (mean diameter D, height H, and basal area G) and soil pH showed positive correlations with DCA1 and negative correlations with DCA2, aligning primarily with control plots in forests with drained mineral soils.

PERMANOVA results confirmed that forest site type significantly influences the species composition of ground vegetation in young Norway spruce stands, explaining 14.51% of the variation (Table S3). In contrast, the effect of fertilization and its interaction with forest site type were not statistically significant. A large proportion of the variation (82.53%) remained unexplained by this model. Pairwise comparisons revealed statistically significant differences between all the site types (Table S4).

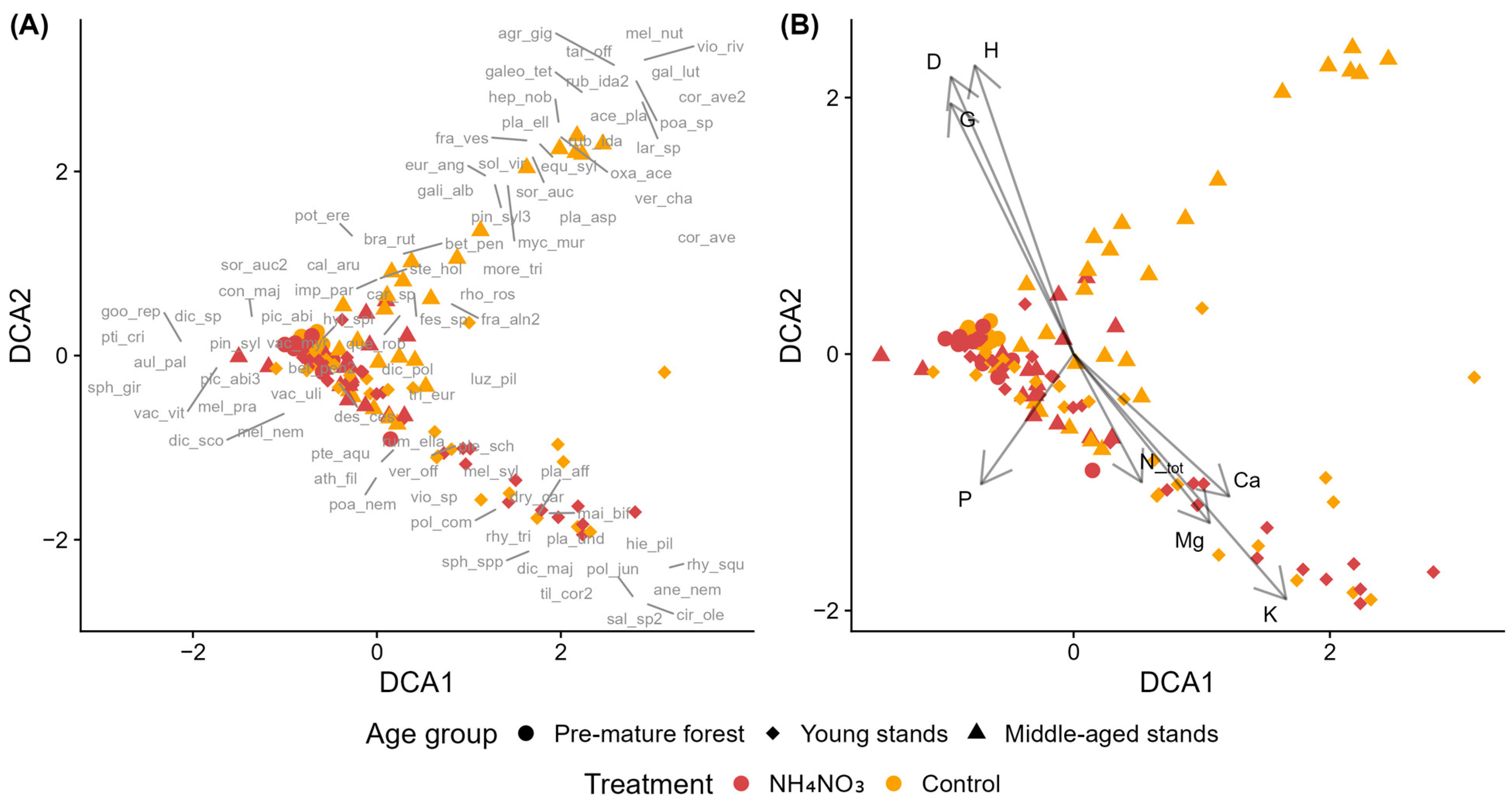

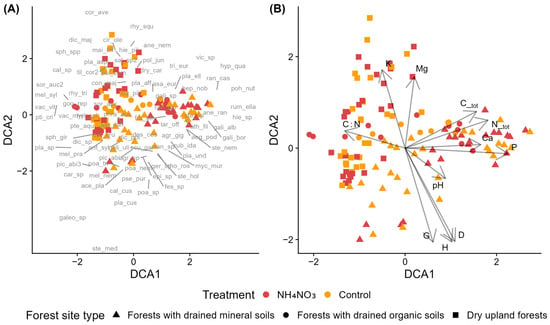

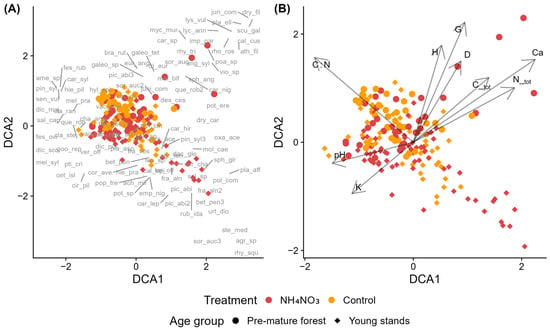

3.2.2. Norway Spruce Stands in Dry Upland Forests Across Different Stand Age Groups

Norway spruce stands of different age groups showed partial separation in ordination space (Figure 3A,B). Control plots from middle-aged stands clustered in the upper region, though some overlapped with other age groups centrally. Young stands showed weaker patterns, with some plots forming a distinct cluster in the lower-right region but most overlapping centrally with other groups. No clear separation between control and fertilized plots was evident across age groups. Species near the control plots of middle-aged stands included herbs with low to moderate N requirements (Melica nutans, Veronica chamaedrys; EIV N ≤ 5) alongside some nitrophilous species (Moehringia trinervia, Mycelis muralis; EIV N ≥ 5) and calciphilous bryophytes (Eurhynchium angustirete, Rhodobryum roseum; EIV R = 7). Plots of young stands were characterized by dry upland forest species such as Pteridium aquilinum and Anemone nemorosa (EIV N ≤ 4), though nitrophilous species (Cirsium oleraceum, Rumex acetosella; EIV N ≥ 6) and hygrophilous bryophytes (Sphagnum spp.; EIV F ≥ 7) were also present. Regarding the environmental factors, D, G, and H had positive correlations with DCA2 and negative correlations with DCA1. Ntot, Ca, Mg, and K showed positive correlations with DCA1 and negative correlations with DCA2, while P showed negative correlations with both axes (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Detrended Correspondence Analysis (DCA) of species composition in control and fertilized plots in Norway spruce stands in dry upland forests across different stand age groups. NH4NO3—ammonium nitrate. (A) Sample plots (symbols indicate treatment and stand age group) with species acronyms shown at their optimum positions (full names in Table A2). (B) Sample plots with environmental vectors: D—mean tree diameter at breast height, G—stand basal area, H—mean tree height, N_tot—soil total nitrogen, K—potassium, Ca—calcium, P—phosphorus, and Mg—magnesium.

PERMANOVA results showed that stand age group was a statistically significant factor and explained the largest proportion of variation in species composition (15.91%, Table S5). The interaction between age group and fertilization also had a significant effect, accounting for 3.4% of the variation, while fertilization alone explained a smaller but still significant proportion (1.9%). In total, the model explained 21.2% of the variation in species composition, with 78.8% remaining unexplained. Pairwise PERMANOVA showed that the strongest compositional differences occurred between age groups, especially between pre-mature stands and both young and middle-aged stands (Table S6). In contrast, differences between control and fertilized plots within the same age group were less pronounced. Significant treatment effects were detected only in pre-mature and middle-aged stands, while young stands showed no significant differences between control and ammonium nitrate plots.

3.2.3. Norway Spruce Stands in Forests with Drained Mineral Soils Across Different Fertilizer Types

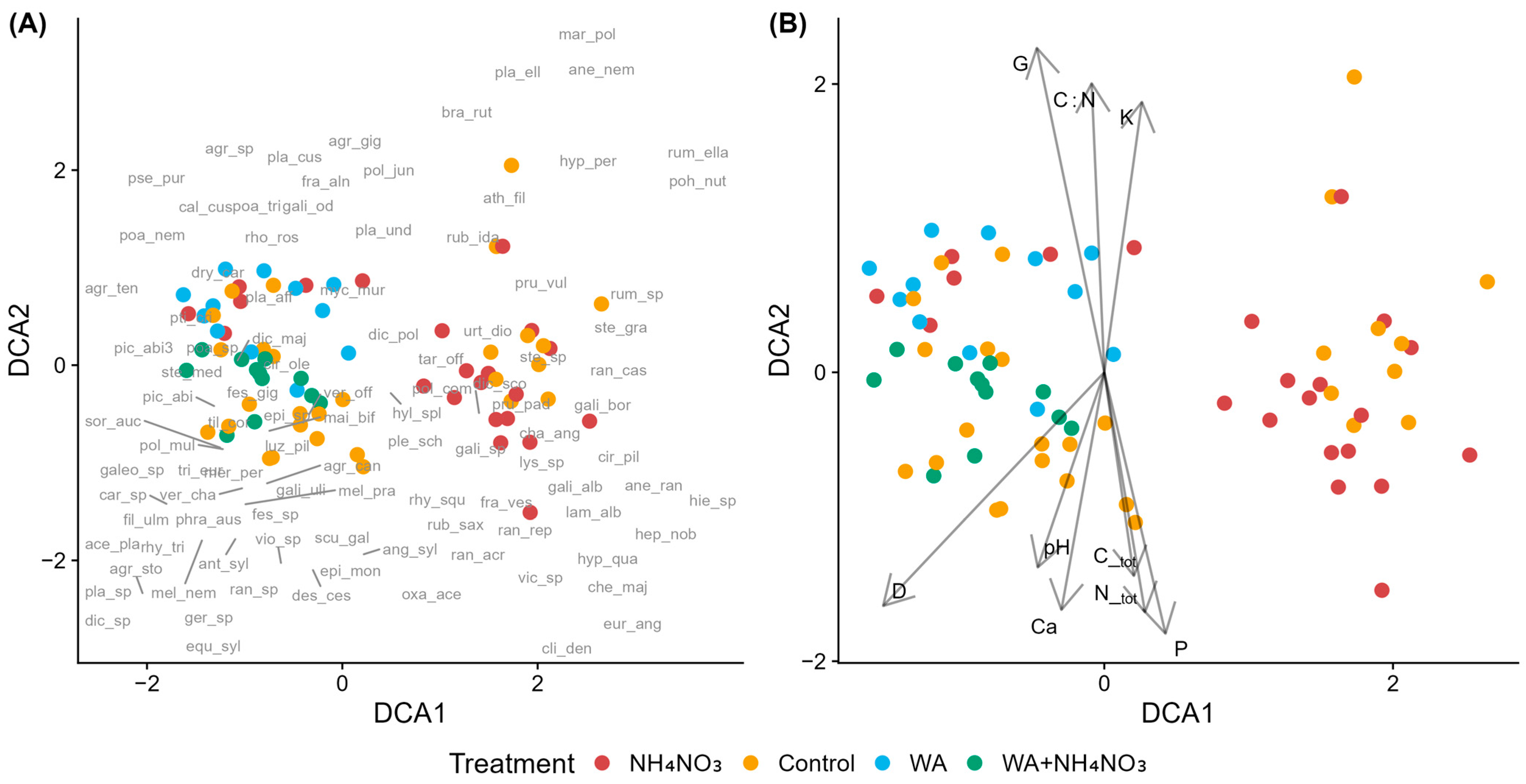

Species composition in young Norway spruce stands in forests with drained mineral soils was analyzed across fertilizer types. The DCA diagram revealed two distinct clusters of sample plots not related to fertilization. Control and NH4NO3-fertilized plots were distributed across both clusters with considerable overlap. Plots treated with wood ash and combined fertilizer (wood ash + NH4NO3) also showed partial overlap with controls (Figure 4A,B).

Figure 4.

Detrended Correspondence Analysis (DCA) of species composition in control and fertilized plots in young Norway spruce stands in forests with drained mineral soils across fertilizer types. (A) Sample plots (symbols indicate treatment) with species acronyms shown at their optimum positions (full names in Table A2). (B) Sample plots with environmental vectors: D—mean tree diameter, G—stand basal area, C_tot—total soil carbon, N_tot—total soil nitrogen, C:N—carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, K—potassium, Ca—calcium, P—phosphorus, and pH—soil pH (CaCl2). Fertilizers include ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3), wood ash (WA), and the combined fertilizer (WA + NH4NO3).

Nitrophilous species including Chamaenerion angustifolium, Chelidonium majus, Taraxacum officinale, and Lamium album (EIV N ≥ 6) were primarly associated with NH4NO3-fertilized plots. Species such as Cirsium oleraceum (N = 5, R = 7) and Stellaria media (N = 8, R = 7) occurred near wood-ash-fertilized plots, while Mycelis muralis (N = 6) was positioned near NH4NO3 and combined fertilizer. Agrostis gigantea, Mercurialis perennis, Athyrium filix-femina, Rubus idaeus, Urtica dioca, Phragmites australis appear to be associated with both control and fertilzed plots or their association is rather unclear. In the moss layer, Pohlia nutans (EIV R = 2) and Marchantia polymorpha (EIV R = 5) clustered near control plots, while Eurhynchium angustirete (EIV R = 7) was associated with fertilized plots. Areas where control and fertilized plots overlap in the ordination are characterized by species indicating moderate to high nutrient availability, while Anthriscus sylvestris (EIV N = 6) clusters near control plots.

Regarding the environmental variables (Figure 4B), N_tot, C_tot, and P are correlated positively with DCA1 and negatively with DCA2. G and C:N are correlated positively with DCA2 and negatively with DCA1, K is correlated positively with both axes, while pH, Ca and D are correlated negatively with both axes.

According to the PERMANOVA results (Table S7), species composition differed significantly both between control and fertilized plots. Fertilization explained 14.2% of the total variation in understorey vegetation and had a statistically significant, though relatively weak, effect.

Pairwise PERMANOVA indicated that differences among the use of different fertilizers were generally stronger than those between fertilized and control plots (Table S8). The clearest separation was observed between NH4NO3 and the combined fertilizer, followed by comparisons involving wood ash and the other treatments. In contrast, comparisons with the control showed weaker effects overall: NH4NO3 plots differed least from controls, the combined fertilizer showed somewhat greater divergence, and wood ash plots exhibited the strongest separation. However, in all cases, the proportion of explained variation remained below 10%.

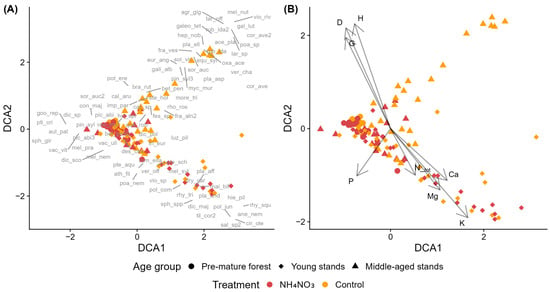

3.3. Scots Pine Stands

When analyzing species composition in control and fertilized Scots pine stands of different age groups in dry upland forests, most plots clustered centrally with considerable overlap between treatments and age groups (Figure 5A,B). Small groups of fertilized plots from both age classes were positioned outside this central cluster. Near the fertilized plots of pre-mature stands, several species with an EIV N ≥ 6 are positioned, such as Athyrium filix-femina, Dryopteris filix-mas, Galeopsis tetrahit, Mycelis muralis, Impatiens parviflora, and the hygrophilous Scutellaria galericulata (Figure 5A). Lycopodium annotinum was another notable species recorded near these plots. In the vicinity of fertilized plots in young stands, species with EIV N ≥ 6 are found, such as Oxalis acetosella, Dactylis glomerata, Urtica dioica, and Stellaria media, as well as moss species with EIV F ≥ 5, including Sphagnum girgensohnii, Plagiomnium affine, and Rhytidiadelphus squarrosus. Several environmental vectors were significantly associated with the ordination. Tree dimensions (H, G, D), Ctot, and Ntot were positively correlated with both DCA1 and DCA2, while K and pH was negatively correlated with both axes (Figure 5B). The C:N ratio showed a positive correlation with DCA2 but a negative correlation with DCA1.

Figure 5.

Detrended Correspondence Analysis (DCA) of species composition in control and ammonium nitrate–fertilized (NH4NO3) plots across young and pre-mature Scots pine stands. (A) Sample plots, where symbols indicate treatment (control vs. NH4NO3) and stand developmental stage, with species acronyms (full names in Table A2) shown at their optimum positions along the ordination gradients. (B) Sample plots with environmental vectors indicating significant correlations with the ordination axes: D—mean tree diameter, G—stand basal area, H—mean tree height, C_tot—total soil carbon, N_tot—total soil nitrogen, C:N—carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, K—potassium, and Ca—calcium, and pH—soil pH (CaCl2).

According to PERMANOVA results, age group is the most significant factor, explaining 5.86% of the variation in species composition among plots (Table S9). Treatment (control vs. fertilized) explains 3.15% of the variation and is also statistically significant. However, the interaction between treatment and age group does not significantly affect species composition. The model explains only 9.57% of the total variation, leaving 90.43% unexplained.

4. Discussion

4.1. Silver Birch

DCA ordination revealed clear compositional differences among plots, with DCA1 separating plots primarily by forest site type and DCA2 showing weaker patterns related to fertilization. PERMANOVA results supported these findings, with forest site type explaining the largest share of variation, followed by fertilization and their interaction, indicating that fertilization effects depend on site-specific conditions. The strong influence of site type reflects fundamental differences in soil properties and hydrology between forests with drained organic soils (formed from accumulated peat) and forests with drained mineral soils (developed from waterlogged mineral material) [59,60], which likely shape both baseline plant communities and their responses to fertilization.

The C:N ratio, an indicator of organic matter mineralization potential [61,62], was higher in forests on drained organic soils and strongly associated with DCA2. Potassium (K) concentration also aligned with DCA2 but in the opposite direction, suggesting that wood ash fertilization increased K availability, particularly in mineral soils where lower C:N ratios are indicative of more rapid nutrient mineralization [1,61,62]. Although Ca is a major component of wood ash, the Ca vector oriented toward mineral soil sites without distinguishing fertilized from control plots, indicating that Ca patterns reflected underlying site differences rather than fertilization effects. Soil pH, in contrast, correlated significantly with community composition and aligned more closely with fertilized plots, reflecting the alkalizing effect of wood ash application. This suggests that pH changes from fertilization influenced species composition more strongly than changes in Ca availability alone.

The Ntot vector did not align closely with fertilized plots or nitrophilous species, likely because total soil N represents a relatively stable pool that may not capture short-term changes in plant-available forms following fertilization. Additionally, species composition may respond more to nutrient availability at the microsite level than to plot-averaged values and environmental vectors in ordination represent correlations rather than causal drivers [63,64,65,66].

Many hygrophilous species persisted in these communities, indicating that moisture availability remains an important ecological filter despite drainage activities. Although fertilization effects were less pronounced than site type effects, nitrophilous species appeared to respond positively to fertilization, supporting the idea that nutrient enrichment can shift the competitive balance in favor of fast-growing, nutrient-demanding taxa. Several studies across Europe similarly show site-specific responses of ground vegetation to N addition—whether through fertilization or deposition—often resulting in shifts toward nitrophilous communities [67,68,69]. PERMANOVA indicated that fertilization had a stronger impact in forests with drained organic soils, though this differential response was not visually apparent in the ordination, likely masked by the strong compositional gradient between site types.

In silver birch middle-aged stands, fertilization mitigated the decline in volume increment during the first three years after application. Compared to control plots, the reduction in volume increment was approximately 40–50% smaller in fertilized plots, indicating a short-term buffering effect on stand productivity.

4.2. Norway Spruce

In the case of young Norway spruce stands, the first DCA axis (DCA1) represented a nutrient-availability gradient, with a negative correlation of the C:N ratio and positive correlations of N, P, and Ca concentrations [61,62]. K and Mg instead aligned with DCA2, suggesting that their distribution is governed by different factors. Similar decoupling of base cations from N and P gradients has been reported in boreal and temperate forests [70,71,72], where K, Ca, and Mg are influenced more by parent material and exchangeable cation pools than by organic matter dynamics. Transient coupling of Ca with N and P may occur under nutrient addition or under acidifying conditions in other systems, when leaching or co-limitation links these nutrient cycles [73,74].

Forest site types differentiated along this nutrient gradient: dry upland forests occupied the nutrient-poor end, forests with drained organic soils spanned low to intermediate levels, and forests with drained mineral soils covered the broadest range. Dry upland forests developed on sandy, acidic podzolic soils, where higher K and Mg concentrations likely reflect parent-material geochemistry rather than greater nutrient availability [59,60,75]. The species composition of these sites corresponded to nutrient-poor forest types typical of the region, with occasional Sphagnum sp. indicating locally wetter microsites. In contrast, forests with drained mineral soils supported more nitrophilous and moisture-demanding species, though these were not specifically associated with fertilized plots.

Both ordination and PERMANOVA analyses indicated that fertilization had no significant impact on species composition in young Norway spruce stands. Vegetation patterns were primarily driven by forest site type, while fertilization and its interaction with site type were not significant. In the ordination, forests with drained organic soils showed little separation from the other site types, likely due to overlapping species composition and the limited number of plots in this category. The absence of detectable vegetation responses to nutrient addition, or effects limited to certain species groups, aligns with results from comparable boreal and temperate forest studies [76,77,78,79].

When assessing the impact of fertilization in Norway spruce stands of different age groups, the ordination revealed stand age as the primary factor differentiating understorey composition. The strongest compositional differences occurred between young and middle-aged stands, likely reflecting the rapid transition in canopy structure, light availability, and competitive environment during this stage of stand development. Pre-mature stands did not form a fully distinct group and overlapped with middle-aged stands, suggesting that compositional change slows once stands reach later stages. Fertilization effects were less apparent in the ordination, with treatment-related patterns much weaker than age-related separation.

DCA2 reflected gradients in stand development and soil nutrient concentrations. The pattern suggests a contrast between younger and older stands rather than a linear age-related decline. Younger stands corresponded to higher total soil nutrient concentrations, while both middle-aged and pre-mature stands showed generally lower concentrations, consistent with nutrient incorporation into biomass as stands develop beyond the early growth phase. DCA1 captured additional variation but without a single dominant driver; instead, it appears to reflect a combination of soil, structural, and successional influences, consistent with weaker and more mixed associations in the ordination. Species composition was significantly correlated with total concentrations of N, Ca, Mg, and K, indicating that vegetation patterns in these stands are associated with underlying soil nutrient status. P also correlated with species composition, but less strongly and in a different direction compared to the other nutrients. This may be related to its different behavior in acidic, sandy soils, where strong sorption processes affect the relationship between total and plant-available pools [80,81]. Because we measured total rather than available nutrients, these correlations should be interpreted as reflecting general soil conditions rather than direct nutrient availability to plants. The C:N ratio did not correlate significantly with species composition. Although lower C:N is often interpreted as higher nutrient availability, this assumption was not supported in our data.

PERMANOVA results supported the ordination patterns, showing that stand age accounted for the greatest share of variation in species composition, far exceeding the effect of fertilization. Although fertilization effects were statistically significant, they explained less than 2% of the total variation in species composition, indicating a weak effect at the community level. A significant age × fertilization interaction indicated that fertilization responses differed across stand development stages. Pairwise tests revealed significant fertilization effects in middle-aged and pre-mature stands, but not in young stands, pointing to age-dependent responses to nutrient addition. Despite these effects, species did not form distinct fertilization-related clusters in ordination space, and nitrophilous taxa occurred in both fertilized and control plots. This pattern suggests that fertilization influenced relative abundances rather than driving turnover in indicator species. The lack of a detectable response in young stands may reflect higher baseline nutrient availability or reduced nutrient limitation earlier in stand development, resulting in limited sensitivity to additional nutrient inputs.

Several studies have found that fertilization effects on understorey vegetation strengthen with stand development, with minimal responses in young stands and detectable effects emerging in more mature forests [79,82]. For example, N addition reduced species richness only in old-growth tropical stands but not in younger rehabilitated stands [83,84], and in temperate hardwood forests, nitrogen fertilization effects varied between ~50-year-old and ~110-year-old stands, with stronger responses in older forests [85]. This pattern appears consistent across biomes, with boreal forest studies showing increasing productivity benefits of fertilization up to around 100 years [3]. Although this evidence comes from overstorey productivity, the age-dependent pattern is consistent with our understory composition results, indicating that fertilization effects depend strongly on stand developmental stage and competitive environment.

In young Norway spruce stands in forests with drained mineral soils, compositional differences were stronger between fertilizer types than between any single fertilizer and controls. Wood ash diverged most from controls while NH4NO3 showed the weakest separation. Although these differences were statistically significant, the proportion of explained variation remained below 10%, indicating that fertilization-related shifts in species composition were modest at the community level. The distribution of NH4NO3-fertilized plots across both ordination clusters likely reflects their application in stands with differing baseline conditions. Despite statistical significance, considerable overlap between fertilized and control plots indicates that fertilization effects were modest relative to underlying site variation and stand developmental stage.

As expected, nitrophilous species were more strongly associated with fertilized plots, particularly those receiving NH4NO3 [86]. This pattern is consistent with nitrogen-driven mechanisms discussed in the introduction, whereby increased N availability enhances the growth and competitive ability of nitrophilous vascular plants. However, species near wood ash fertilized plots were characterized not only by N preferences but also by higher reaction values, reflecting the pH-raising effects of ash application. Such pH- and base cation–mediated effects are known to disproportionately affect bryophyte communities and acidophilous species. The moss layer showed a pH-related pattern, with acidophilous species associated with control plots and calciphilous species with fertilized plots. Soil pH correlated significantly with species composition, with the pH vector aligning with nutrient and base cation gradients toward fertilized plots, particularly those receiving wood ash. This pH-mediated shift is consistent with wood ash raising soil pH and base cation availability [36], which favors calciphilous species while reducing habitat suitability for acid-loving bryophytes [87]. The greater compositional divergence of wood ash fertilization compared to NH4NO3 alone likely reflects these additional pH- and cation-driven mechanisms, rather than N enrichment alone.

Overall, the modest share of variation explained by fertilization indicates that nutrient additions influence ground vegetation within constraints imposed by local site conditions, stand developmental stage, and the competitive environment [88]. Despite the significant effects of forest site type and stand age, a large proportion of the variation in species composition in Norway spruce stands remained unexplained by the PERMANOVA models. Such high residual variation is common in multivariate analyses of understorey plant communities, where species composition is shaped by a wide array of interacting biotic and abiotic factors operating at fine spatial scales. Ground vegetation is particularly sensitive to small-scale heterogeneity in light availability, soil moisture, microtopography, litter depth, and soil chemical properties, many of which were not explicitly included in the model. In addition, historical factors such as drainage intensity and stand development history, as well as stochastic processes including dispersal limitation and priority effects, may further contribute to unexplained variation. A similarly high level of unexplained variation was observed in Scots pine stands, whereas silver birch stands showed a lower, though still substantial, proportion of unexplained variance, indicating that high residual variability in understorey species composition was common across the studied forest types and not unique to Norway spruce stands.

In Norway spruce stands, increases in volume increment were mainly observed in young stands in forests with drained organic soils, where fertilized plots showed relative increases on the order of approximately 20–40% compared to control plots, whereas changes in volume increment were small or inconsistent in middle-aged and pre-mature stands, particularly dry upland forests and forests with drained mineral soils.

4.3. Scots Pine

Regarding Scots pine stands, the DCA ordination shows weak differentiation among the plots, while PERMANOVA reveals statistically significant effects of both stand age and treatment on species composition. Stand age had a somewhat stronger influence than fertilization, but overall differences among plots were small, indicating that community responses to fertilization were limited. The absence of a significant treatment × age interaction suggests that fertilization effects did not differ detectably between the two age groups. DCA2 captured variation in stand structure since tree and stand size metrics (D, G, and H) showed a stronger correlation with DCA2 than with DCA1. While high C:N ratios generally indicate low nutrient availability, the nutrient concentration vectors did not show the expected inverse relationship with the C:N vector. This suggests that nutrient quantity and availability are decoupled, reflecting more complex nutrient patterns than can be inferred from total nutrient pools alone. Soil pH correlated significantly with species composition but showed an inverse relationship with Ca concentration, contrary to typical expectations. This pattern may reflect pH control by factors other than base cation availability in these sandy, acidic podzolic soils, such as organic matter quality or localized acidification processes.

Despite the limited separation observed in the DCA, several nitrophilous species were positioned closer to fertilized plots in the ordination space, suggesting an emerging shift toward communities with higher N demand. These species were less common in control plots, indicating that fertilization may have created conditions favorable for their establishment under previously N-limited conditions. This pattern agrees with earlier findings showing that N addition tends to promote nitrophilous species and favor those adapted to higher nutrient availability [89,90,91].

Lycopodium annotinum, a slow-regenerating species listed in the Latvian Red Data Book and protected under national regulations, was also found in fertilized plots, indicating that this species persists under the fertilization levels applied in this study. The association of hygrophilous mosses (Sphagnum girgensohnii, Plagiomnium affine, Rhytidiadelphus squarrosus) with fertilized plots in young stands suggests that fertilization effects on bryophyte communities may depend on interactions between nutrient enrichment and local moisture availability.

In Scots pine stands of dry upland forests, fertilization increased stand volume increment during the five-year period following application. Compared to control plots, fertilized plots exhibited a substantially higher volume increment, corresponding to a relative increase of approximately 40–60%, depending on age group.

4.4. Limitations of the Study

Our results reflect short-term responses (1–3 years after fertilization); however, the time elapsed since fertilization varied among plots, and vegetation responses may differ between early and slightly later post-fertilization stages. The results should therefore be interpreted as early ecological effects rather than long-term ecosystem changes.

Analyzing each tree species separately, with further stratification by age group and site type, precluded cross-species statistical comparison of treatment effects on ground vegetation. While we could test treatment effects within each species (e.g., whether Norway spruce vegetation changed with fertilization), we could not test whether the magnitude or direction of these effects differed significantly among silver birch, Norway spruce, and Scots pine forests. Consequently, observed variation in responses among the separate analyses may be attributable to tree species, stand age, site conditions, or their interactions, but we cannot statistically distinguish among all of these possibilities.

In addition, our soil chemical analyses measured total nutrient concentrations (e.g., total C and N) rather than plant-available nutrient pools. Consequently, relationships between soil chemistry and vegetation composition should be interpreted as indicators of general site conditions rather than direct measures of nutrient availability to understorey plants. Short-term changes in nutrient availability following fertilization, particularly for N and P, may therefore not be fully captured by our measurements.

5. Synthesis and Conclusions

Forest site type and stand developmental stage were the primary drivers of understorey composition across all dominant tree species, with fertilization effects being statistically significant but explaining a relatively small proportion of compositional variation (typically <10%, range 0.9–14.2%). Fertilization responses were strongly context-dependent, varying with stand age in Norway spruce stands, where effects were detectable in middle-aged and pre-mature stands but absent in young stands.

Wood ash fertilization caused greater compositional divergence than NH4NO3, driven by pH-mediated effects beyond nitrogen enrichment alone. This was most evident in bryophyte communities, where calciphilous species became associated with fertilized plots and acidophilous species with controls, though the modest representation of bryophytes in our ordinations—partly due to exclusion of centrally positioned species—warrants cautious interpretation of these patterns.

Nitrophilous vascular plants showed positive associations with fertilized plots, particularly under NH4NO3 treatment, consistent with nitrogen-driven competitive mechanisms. Overall, single-application fertilization produced detectable but limited short-term changes in ground vegetation composition under the conditions we examined, while achieving substantial productivity gains (volume increment increases of 20–60% depending on tree species and site conditions). This contrast between modest compositional responses and substantial production responses suggests that fertilization can meet timber production objectives without causing dramatic shifts in understory plant communities in the short term. However, long-term monitoring remains essential to assess potential cumulative effects, including gradual shifts toward nitrophilous communities and delayed responses in bryophyte layers.

All three hypotheses were supported by our results:

Hypothesis 1.

Fertilization effects varied with stand age and site type.

Hypothesis 2.

Wood ash produced different compositional shifts than NH4NO3 due to pH effects.

Hypothesis 3.

Herbs and bryophytes showed distinct response patterns.

Nonetheless, the modest amount of variation explained by fertilization and limited representation of bryophytes in our ordinations call for careful interpretation of these patterns.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/environments13020095/s1. Table S1. Results of the PERMANOVA analysis assessing the effects of treatment (control vs ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3) + wood ash), forest site type, and their interaction on species composition variation in middle-aged silver birch stands. Table S2. Pairwise comparisons of species composition between treatment and forest site type groups in middle-aged silver birch stands (NH4NO3–ammonium nitrate, WA–wood ash). Table S3. Results of the PERMANOVA analysis assessing the effects of treatment (control vs ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3)), forest site type, and their interaction on species composition variation in young Norway spruce stands. Table S4. Pairwise comparisons of species composition between forest site type groups in young Norway spruce stands. Table S5. PERMANOVA results for the effects of treatment (control vs ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3)), stand age group, and their interaction on species composition in Norway spruce stands from dry upland forests. Table S6. Pairwise comparisons of species composition between treatment and stand age group combinations in Norway spruce stands from dry upland forests (NH4NO3–ammonium nitrate). Table S7. PERMANOVA results for the effects of treatment (control vs ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3), wood ash or NH4NO3 + wood ash) on species composition in young Norway spruce stands in forests with drained mineral soils. Table S8. Pairwise comparisons of species composition between different treatments (control, ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3), wood ash (WA), NH4NO3 + wood ash) in young Norway spruce stands in forests with drained mineral soils. Table S9. PERMANOVA results for the effects of treatment (control vs ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3)), stand age group, and their interaction on species composition in young and pre-mature Scots pine stands in dry upland forests.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P.; methodology, G.P. and D.E.; software, D.E.; validation, G.P. and D.E.; formal analysis, D.E.; investigation, Z.Z., D.P. and I.S.; resources, A.L.; data curation, G.P. and A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, G.P.; writing—review and editing, G.P. and D.E.; visualization, G.P. and D.E.; supervision, A.L.; project administration, A.L.; funding acquisition, A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by Latvia Council of Science national research programme project: “Forest4LV—Innovation in Forest Management and Value Chain for Latvia’s Growth: New Forest Services, Products and Technologies” (No.: VPP-ZM-VRIIILA-2024/2-0002).

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Data used in the study were partly acquired in the project “Monitoring of forest fertilization effect” No. 5- 5.5.1_001j_101_23_55. Contribution of authors is covered by projects “Comprehensive analysis of hemiboreal forest structure, species composition and ecosystem services using VHR hyperspectral and LiDAR data (HYLIFORES)” No. lzp-2024/1-0484 and “Research and Innovation Based Solutions to Support the Peat Sector’s Transition to a Climate Neutral Economy (PeatTransform)” 6.1.1.2/1/25/A/001.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Eigenvalues and axis lengths from DCAs displayed in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5.

| Figure | Axis | Eigenvalue | Axis Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DCA1 | 0.8016 | 4.5549 |

| 1 | DCA2 | 0.4166 | 4.0936 |

| 1 | DCA3 | 0.2713 | 2.4695 |

| 1 | DCA4 | 0.2473 | 2.1216 |

| 2 | DCA1 | 0.6474 | 4.8256 |

| 2 | DCA2 | 0.5306 | 4.8507 |

| 2 | DCA3 | 0.2943 | 3.1733 |

| 2 | DCA4 | 0.3225 | 3.7083 |

| 3 | DCA1 | 0.5936 | 4.6287 |

| 3 | DCA2 | 0.5397 | 4.3326 |

| 3 | DCA3 | 0.3421 | 2.7242 |

| 3 | DCA4 | 0.2458 | 3.2529 |

| 4 | DCA1 | 0.6568 | 4.2814 |

| 4 | DCA2 | 0.3423 | 3.5589 |

| 4 | DCA3 | 0.2990 | 2.7693 |

| 4 | DCA4 | 0.2293 | 2.6680 |

| 5 | DCA1 | 0.4571 | 3.8630 |

| 5 | DCA2 | 0.3839 | 4.2244 |

| 5 | DCA3 | 0.3130 | 2.9088 |

| 5 | DCA4 | 0.2415 | 3.0310 |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Species list with acronyms used in DCA.

Table A2.

Species list with acronyms used in DCA.

| Vegetation Layer | Latin Name | Acronym |

|---|---|---|

| Moss | Aulacomnium palustre | aul_pal |

| Moss | Brachythecium rutabulum | bra_rut |

| Moss | Calliergon cordifolium | cal_cor |

| Moss | Calliergonella cuspidata | cal_cus |

| Moss | Cirriphyllum piliferum | cir_pil |

| Moss | Climacium dendroides | cli_den |

| Moss | Dicranum sp. | dic_sp |

| Moss | Dicranum majus | dic_maj |

| Moss | Dicranum montanum | dic_mon |

| Moss | Dicranum polysetum | dic_pol |

| Moss | Dicranum scoparium | dic_sco |

| Moss | Eurhynchium angustirete | eur_ang |

| Moss | Eurhyncium striatum | eur_str |

| Moss | Funaria hygrometrica | fun_hyg |

| Moss | Hylocomium splendens | hyl_spl |

| Moss | Marchantia polymorpha | mar_pol |

| Moss | Oxyrrhynchium hians | oxy_hia |

| Moss | Plagiochila asplenioides | pla_asp |

| Moss | Plagiomnium sp. | pla_sp |

| Moss | Plagiomnium affine | pla_aff |

| Moss | Plagiomnium cuspidatum | pla_cus |

| Moss | Plagiomnium ellipticum | pla_ell |

| Moss | Plagiomnium undulatum | pla_und |

| Moss | Pleurozium schreberi | ple_sch |

| Moss | Polytrichum commune | pol_com |

| Moss | Polytrichum juniperinum | pol_jun |

| Moss | Pseudoschleropodium purum | pse_pur |

| Moss | Ptilium crista-castrensis | pti_cri |

| Moss | Rhytidiadelphus squarrosus | rhy_squ |

| Moss | Rhytidiadelphus triquetrus | rhy_tri |

| Moss | Rhodobryum roseum | rho_ros |

| Moss | Sphagnum angustifolium | sph_ang |

| Moss | Sphagnum girgensohnii | sph_gir |

| Moss | Sphagnum magellanicum | sph_mag |

| Moss | Sphagnum squarrosum | sph_ squ |

| Moss | Sphagnum spp. | sph_spp |

| Moss | Cetraria Islandica | cet_isl |

| Moss | Cladonia rangiferina | cla_ran |

| Moss | Cladonia stellaris | cla_ste |

| Herb | Acer plantanoides | ace_pla |

| Herb | Achillea millefolium | ach_mil |

| Herb | Aegopodium podagraria | aeg_pod |

| Herb | Agrostis sp. | agr_sp |

| Herb | Agrostis canina | agr_can |

| Herb | Agrostis gigantea | agr_gig |

| Herb | Agrostis stolonifera | agr_sto |

| Herb | Agrostis tenuis | agr_ten |

| Herb | Amelanchier spicata | ame_spi |

| Herb | Andromeda polifolia | and_pol |

| Herb | Anemone nemorosa | ane_nem |

| Herb | Anemone ranunculoides | ane_ran |

| Herb | Asarum europaeum | asa_eur |

| Herb | Athyrium filix-femina | ath_fil |

| Herb | Angelica sylvestris | ang_syl |

| Herb | Anthoxanthum odoratum | ant_odo |

| Herb | Anthriscus sylvestris | ant_syl |

| Herb | Betula pendula < 0.5 m | bet_pen |

| Herb | Betula pubescens < 0.5 m | bet_pub |

| Herb | Calamagrostis arundinacea | cal_aru |

| Herb | Calamagrostis canescens | cal_can |

| Herb | Calamagrostis epigeios | cal_epi |

| Herb | Calamagrostis sp. | cal_sp |

| Herb | Calluna vulgaris | cal_vul |

| Herb | Carex flava | car_fla |

| Herb | Carex hirta | car_hir |

| Herb | Carex leporina | car_lep |

| Herb | Carex nigra | car_nig |

| Herb | Carex pilulifera | car_pil |

| Herb | Carex rostrata | car_ros |

| Herb | Carex sylvatica | car_syl |

| Herb | Carex vesicaria | car_ves |

| Herb | Carex sp. | car_sp |

| Herb | Chamaenerion angustifolium | cha_ang |

| Herb | Chelidonium majus | che_maj |

| Herb | Circaea alpina | cir_alp |

| Herb | Cirsium heterophyllum | cir_het |

| Herb | Cirsium oleraceum | cir_ole |

| Herb | Comarum palustre | com_pal |

| Herb | Convallaria majalis | con_maj |

| Herb | Corylus avellana | cor_ave |

| Herb | Dactylis glomerata | dac_glo |

| Herb | Deschampsia cespitosa | des_ces |

| Herb | Dryopteris carthusiana | dry_car |

| Herb | Dryopteris cristata | dry_cri |

| Herb | Dryopteris expansa | dry_exp |

| Herb | Dryopteris filix-mas | dry_fil |

| Herb | Empetrum nigrum | emp_nig |

| Herb | Epilobium sp. | epi_sp |

| Herb | Epilobium montanum | epi_mon |

| Herb | Equisetum sp. | equ_sp |

| Herb | Equisetum palustre | equ_pal |

| Herb | Equisetum pratense | equ_pra |

| Herb | Equisetum sylvaticum | equ_syl |

| Herb | Festuca sp. | fes_sp |

| Herb | Festuca gigantea | fes_gig |

| Herb | Festuca rubra | fes_rub |

| Herb | Festuca ovina | fes_ovi |

| Herb | Filipendula ulmaria | fil_ulm |

| Herb | Fragaria vesca | fra_ves |

| Herb | Frangula alnus | fra_aln |

| Herb | Galeobdolon luteum | gal_lut |

| Herb | Galeopsis sp | galeo_sp |

| Herb | Galeopsis tetrahit | galeo_tet |

| Herb | Galium sp. | gali_sp |

| Herb | Galium album | gali_alb |

| Herb | Galium aparine | gali_apa |

| Herb | Galium boreale | gali_bor |

| Herb | Galium odoratum | gali_od |

| Herb | Galium palustre | gali_pal |

| Herb | Galium uliginosum | gali_uli |

| Herb | Geranium sp. | ger_sp |

| Herb | Gymnocarpium dryopteris | gym_dry |

| Herb | Geranium robertianum | ger_rob |

| Herb | Geum rivale | geu_riv |

| Herb | Goodyera repens | goo_rep |

| Herb | Hepatica nobilis | hep_nob |

| Herb | Hieracium pilosella | hie_pil |

| Herb | Hieracium praealtum | hie_pra |

| Herb | Hieracium sp. | hie_sp |

| Herb | Hypericum perforatum | hyp_per |

| Herb | Hypericum quadrangulum | hyp_qua |

| Herb | Impatiens parviflora | imp_par |

| Herb | Impatiens noli-tangere | imp_nol |

| Herb | Juncus sp. | jun_sp |

| Herb | Juncus conglomeratus | jun_com |

| Herb | Juncus effusus | jun_eff |

| Herb | Juniperus communis | juni_com |

| Herb | Lamium album | lam_alb |

| Herb | Ledum palustre | led_pal |

| Herb | Lathyrus sp. | lat_sp |

| Herb | Luzula pilosa | luz_pil |

| Herb | Lathyrus vernus | lat_ver |

| Herb | Lycopodium annotinum | lyc_ann |

| Herb | Lycopus europaeus | lyc_eur |

| Herb | Lysimachia sp. | lys_sp |

| Herb | Lysimachia vulgaris | lys_vul |

| Herb | Maianthemum bifolium | mai_bif |

| Herb | Melampyrum nemorosum | mel_nem |

| Herb | Melampyrum pratense | mel_pra |

| Herb | Melampyrum sylvaticum | mel_syl |

| Herb | Melica nutans | mel_nut |

| Herb | Mentha sp. | men_sp |

| Herb | Mercurialis perennis | mer_per |

| Herb | Milium effusum | mil_eff |

| Herb | Moehringia trinervia | more_tri |

| Herb | Molinia caerulea | mol_cae |

| Herb | Mycelis muralis | myc_mur |

| Herb | Myosotis sylvatica | myo_syl |

| Herb | Orthilia secunda | ort_sec |

| Herb | Oxalis acetosella | oxa_ace |

| Herb | Paris quadrifolia | par_qua |

| Herb | Phragmites australis | phra_aus |

| Herb | Picea abies | pic_abi |

| Herb | Pinus sylvestris | pin_syl |

| Herb | Poa sp. | poa_sp |

| Herb | Poa palustris | poa_pal |

| Herb | Poa nemoralis | poa_nem |

| Herb | Poa pratensis | poa_pra |

| Herb | Poa trivialis | poa_tri |

| Herb | Pohlia nutans | poh_nut |

| Herb | Polygonatum multiflorum | pol_mul |

| Herb | Potentilla sp. | pot_sp |

| Herb | Potentilla erecta | pot_ere |

| Herb | Prunella vulgaris | pru_vul |

| Herb | Prunus padus | pru_pad |

| Herb | Pteridium aquilinum | pte_aqu |

| Herb | Quercus robur < 0.5 m | que_rob |

| Herb | Ranunculus sp. | ran_sp |

| Herb | Ranunculus acris | ran_acr |

| Herb | Ranunculus auricomus | ran_aur |

| Herb | Ranunculus cassubicus | ran_cas |

| Herb | Ranunculus repens | ran_rep |

| Herb | Rubus sp. | rub_sp |

| Herb | Rubus idaeus | rub_ida |

| Herb | Rubus saxatilis | rub_sax |

| Herb | Rumex acetosa | rum_ace |

| Herb | Rumex acetosella | rum_ella |

| Herb | Rumex sp. | rum_sp |

| Herb | Salix sp. | sal_sp |

| Herb | Senecio vulgaris | sen_vul |

| Herb | Scutellaria galericulata | scu_gal |

| Herb | Solanum dulcamara | sol_dul |

| Herb | Solidago sp. | sol_sp |

| Herb | Solidago virgaurea | sol_vir |

| Herb | Sorbus aucuparia | sor_auc |

| Herb | Stellaria graminea | ste_gra |

| Herb | Stellaria holostea | ste_hol |

| Herb | Stellaria media | ste_med |

| Herb | Stellaria nemorum | ste_nem |

| Herb | Stellaria sp. | ste_sp |

| Herb | Taraxacum officinale | tar_off |

| Herb | Tilia cordata | til_cor |

| Herb | Trientalis europaea | tri_eur |

| Herb | Urtica dioica | urt_dio |

| Herb | Vaccinium myrtillus | vac_myr |

| Herb | Vaccinium vitis-idaea | vac_vit |

| Herb | Vaccinium uliginosum | vac_uli |

| Herb | Veronica chamaedrys | ver_cha |

| Herb | Veronica officinalis | ver_off |

| Herb | Vicia sp. | vic_sp |

| Herb | Viola sp. | vio_sp |

| Herb | Viola epipsila | vio_epi |

| Herb | Viola montana | vio_mon |

| Herb | Viola riviniana | vio_riv |

| Herb | Viola uliginosa | vio_uli |

| Shrub | Betula pendula | bet_pen2 |

| Shrub | Betula pubescens | bet_pub2 |

| Shrub | Cirsium oleraceum | cir_ole2 |

| Shrub | Corylus avellana | cor_ave2 |

| Shrub | Frangula alnus | fra_aln2 |

| Shrub | Lonicera xylosteum | lon_xyl |

| Shrub | Picea abies | pic_abi2 |

| Shrub | Pinus sylvestris | pin_syl2 |

| Shrub | Populus tremula | pop_tre |

| Shrub | Quercus robur | que_rob2 |

| Shrub | Rubus idaeus | rub_ida2 |

| Shrub | Salix caprea | sal_cap |

| Shrub | Salix sp. | sal_sp |

| Shrub | Sambucus racemosa | sam_rac |

| Shrub | Sorbus aucuparia | sor_auc2 |

| Shrub | Tilia cordata | til_cor2 |

| Shrub | Urtica dioica. | urt_dio2 |

| Tree | Acer platanoides | ace_pla3 |

| Tree | Betula pendula | bet_pen3 |

| Tree | Betula pubescens | bet_pub3 |

| Tree | Larix sp. | lar_sp |

| Tree | Picea abies | pic_abi3 |

| Tree | Pinus sylvestris | pin_syl3 |

| Tree | Quercus robur | que_rob3 |

| Tree | Sorbus aucuparia | sor_auc3 |

Appendix C

Table A3.

Soil chemical parameters used as environmental vectors in DCA. Units: Ctot, Ntot, K, P, Ca, and Mg in g kg−1; C:N unitless.

Table A3.

Soil chemical parameters used as environmental vectors in DCA. Units: Ctot, Ntot, K, P, Ca, and Mg in g kg−1; C:N unitless.

| ID | Treatment | Ctot | Ntot | C:N | K | P | Ca | Mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AN | 18.05 | 0.98 | 36.13 | 1.06 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 1.74 |

| 1 | Control | 20.22 | 1.03 | 36.50 | 0.85 | 0.71 | 0.56 | 1.25 |

| 2 | AN | 128.22 | 6.23 | 40.18 | 2.13 | 0.44 | 1.40 | 1.65 |

| 2 | Control | 121.20 | 5.94 | 37.50 | 2.38 | 0.39 | 1.45 | 1.74 |

| 3 | AN | 17.97 | 0.98 | 34.81 | 0.78 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.98 |

| 3 | Control | 19.56 | 1.01 | 36.33 | 0.78 | 0.47 | 0.43 | 0.96 |

| 4 | AN | 134.83 | 4.97 | 32.67 | 0.59 | 0.25 | 0.76 | 0.29 |

| 4 | Control | 25.98 | 1.15 | 38.57 | 0.97 | 0.27 | 0.69 | 0.84 |

| 5 | AN | 24.22 | 1.22 | 34.49 | 0.74 | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0.45 |

| 5 | Control | 43.92 | 1.74 | 41.53 | 0.94 | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.41 |

| 6 | AN | 145.05 | 9.48 | 32.45 | 0.74 | 1.03 | 3.26 | 0.95 |

| 6 | Control | 109.88 | 6.88 | 34.54 | 0.68 | 0.71 | 1.78 | 0.69 |

| 7 | AN | 159.38 | 10.61 | 39.90 | 0.70 | 0.77 | 4.28 | 0.95 |

| 7 | Control | 157.94 | 9.71 | 37.53 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 5.54 | 1.00 |

| 8 | AN | 72.29 | 3.82 | 38.32 | 0.82 | 0.48 | 1.06 | 0.82 |

| 8 | Control | 96.97 | 5.00 | 39.86 | 0.93 | 0.59 | 2.32 | 0.96 |

| 8 | WA | 84.21 | 4.49 | 38.86 | 0.91 | 0.58 | 1.34 | 0.95 |

| 9 | AN | 27.23 | 1.19 | 45.56 | 0.66 | 0.73 | 0.35 | 0.69 |

| 9 | Control | 27.65 | 1.21 | 43.25 | 0.63 | 0.87 | 0.32 | 0.61 |

| 10 | AN | 35.08 | 1.70 | 39.14 | 1.03 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 1.34 |

| 10 | Control | 32.98 | 1.69 | 38.28 | 0.90 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 1.14 |

| 11 | AN | 30.85 | 1.40 | 42.73 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.59 | 1.02 |

| 11 | Control | 27.48 | 1.35 | 40.00 | 0.63 | 0.82 | 0.56 | 0.84 |

| 12 | AN | 33.10 | 1.48 | 42.35 | 0.79 | 0.66 | 0.48 | 0.79 |

| 12 | Control | 24.33 | 1.22 | 39.47 | 0.87 | 0.78 | 0.55 | 0.87 |

| 13 | AN | 26.69 | 1.23 | 42.51 | 0.77 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.70 |

| 13 | Control | 22.83 | 1.04 | 43.30 | 0.76 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.75 |

| 14 | AN | 413.94 | 16.17 | 48.48 | 0.67 | 0.85 | 2.83 | 0.72 |

| 14 | Control | 300.25 | 12.39 | 44.56 | 0.72 | 0.66 | 2.14 | 0.58 |

| 15 | AN | 162.12 | 8.22 | 38.33 | 0.52 | 0.65 | 1.53 | 0.41 |

| 15 | Control | 99.33 | 4.66 | 41.70 | 0.41 | 0.27 | 0.58 | 0.26 |

| 16 | AN | 198.03 | 8.36 | 43.32 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 2.25 | 0.54 |

| 16 | Control | 347.07 | 15.19 | 43.41 | 0.68 | 0.74 | 5.84 | 0.79 |

| 17 | AN | 15.07 | 0.82 | 33.87 | 0.47 | 0.69 | 0.20 | 0.28 |

| 17 | Control | 13.74 | 0.77 | 33.89 | 0.46 | 0.69 | 0.21 | 0.29 |

| 18 | AN | 25.50 | 1.20 | 42.52 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 0.38 | 0.43 |

| 18 | Control | 27.65 | 1.28 | 43.11 | 0.56 | 0.80 | 0.37 | 0.39 |

| 19 | AN + WA | 93.85 | 5.89 | 30.18 | 0.44 | 0.74 | 4.19 | 0.60 |

| 19 | Control | 250.71 | 9.49 | 41.22 | 0.46 | 0.65 | 4.33 | 0.62 |

| 20 | AN + WA | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 20 | Control | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

N/A = not available.

Appendix D

Table A4.

Forest stand characteristics and variables (D, H, G) used as environmental vectors in DCA. NS—Norway spruce, SP-Scots pine, and SB—silver birch.

Table A4.

Forest stand characteristics and variables (D, H, G) used as environmental vectors in DCA. NS—Norway spruce, SP-Scots pine, and SB—silver birch.

| ID | Tree Species | Forest Site Type | Treatment | Stand Age Group | D | H | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NS | Dry upland forests | AN | Pre-mature | 19.700 | 18.200 | 22.500 |

| 1 | NS | Dry upland forests | Control | Pre-mature | 19.100 | 16.000 | 23.700 |

| 2 | NS | Dry upland forests | AN | Young | 13.243 | 14.643 | 17.786 |

| 2 | NS | Dry upland forests | Control | Young | 13.743 | 13.686 | 17.114 |

| 3 | NS | Dry upland forests | AN | Middle-aged | 21.033 | 19.633 | 24.367 |

| 3 | NS | Dry upland forests | Control | Middle-aged | 21.067 | 17.933 | 21.833 |

| 4 | NS | Dry upland forests | AN | Pre-mature | 24.700 | 23.600 | 35.000 |

| 4 | NS | Dry upland forests | Control | Pre-mature | 23.700 | 22.900 | 38.450 |

| 5 | NS | Dry upland forests | AN | Young | 16.850 | 18.100 | 22.950 |

| 5 | NS | Dry upland forests | Control | Young | 16.950 | 17.500 | 23.150 |

| 6 | NS | Forests with drained mineral soils | AN | Young | 19.500 | 18.225 | 23.288 |

| 6 | NS | Forests with drained mineral soils | Control | Young | 18.620 | 18.280 | 24.040 |

| 7 | NS | Forests with drained organic soils | AN | Young | 16.867 | 16.450 | 18.367 |

| 7 | NS | Forests with drained organic soils | Control | Young | 17.700 | 16.175 | 20.425 |

| 8 | NS | Forests with drained mineral soils | Control | Young | 25.167 | 18.300 | 20.900 |

| 8 | NS | Forests with drained mineral soils | WA/AN | Young | 24.900 | 18.433 | 21.633 |

| 9 | SP | Dry upland forests | AN | Pre-mature | 18.175 | 18.800 | 27.600 |

| 9 | SP | Dry upland forests | Control | Pre-mature | 19.125 | 20.150 | 30.300 |

| 10 | SP | Dry upland forests | AN | Young | 17.200 | 14.767 | 24.500 |

| 10 | SP | Dry upland forests | Control | Young | 17.133 | 15.633 | 24.900 |

| 11 | SP | Dry upland forests | AN | Pre-mature | 26.267 | 23.433 | 24.100 |

| 11 | SP | Dry upland forests | Control | Pre-mature | 24.833 | 21.833 | 27.233 |

| 12 | SP | Dry upland forests | AN | Young | 17.975 | 17.750 | 18.025 |

| 12 | SP | Dry upland forests | Control | Young | 18.650 | 17.500 | 18.450 |

| 13 | SP | Dry upland forests | AN | Young | 17.270 | 16.230 | 19.300 |

| 13 | SP | Dry upland forests | Control | Young | 17.457 | 17.043 | 18.814 |

| 14 | SP | Dry upland forests | AN | Pre-mature | 35.700 | 27.600 | 38.600 |

| 14 | SP | Dry upland forests | Control | Pre-mature | 26.000 | 23.850 | 37.050 |

| 15 | SP | Dry upland forests | AN | Young | 19.167 | 15.533 | 19.700 |

| 15 | SP | Dry upland forests | Control | Young | 16.667 | 16.300 | 19.600 |

| 16 | SP | Dry upland forests | AN | Pre-mature | 23.567 | 24.267 | 37.100 |

| 16 | SP | Dry upland forests | Control | Pre-mature | 24.767 | 24.333 | 37.033 |

| 17 | SP | Dry upland forests | AN | Young | 13.167 | 10.533 | 18.333 |

| 17 | SP | Dry upland forests | Control | Young | 13.267 | 11.000 | 19.967 |

| 18 | SP | Dry upland forests | AN | Middle-aged | 20.600 | 16.300 | 21.300 |

| 18 | SP | Dry upland forests | Control | Middle-aged | 20.500 | 18.360 | 28.420 |

| 19 | SB | Forests with drained mineral soils | Control | Middle-aged | 17.650 | 19.325 | 13.525 |

| 19 | SB | Forests with drained mineral soils | WA/AN | Middle-aged | 18.725 | 19.350 | 17.225 |

| 20 | SB | Forests with drained organic soils | WA/AN | Middle-aged | 15.900 | 14.850 | 17.000 |

| 20 | SP | Dry upland forests | AN | Middle-aged | 19.250 | 17.250 | 32.250 |

References

- Pitman, R.M. Wood ash use in forestry—A review of the environmental impacts. For. Int. J. For. Res. 2006, 79, 563–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannam, K.D.; Venier, L.; Allen, D.; Deschamps, C.; Hope, E.; Jull, M.; Kwiaton, M.; McKenney, D.; Rutherford, P.M.; Hazlett, P.W. Wood ash as a soil amendment in Canadian forests: What are the barriers to utilization? Can. J. For. Res. 2018, 48, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeraeve, M.; Granath, G.; Lindahl, B.D.; Clemmensen, K.E.; Strengbom, J. How does forest fertilization influence tree productivity of boreal forests? An analysis of data from commercial forestry across Sweden. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 124023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A.; de Montigny, L.; Prescott, C.; Sajedi, T. A Systematic Review of Forest Fertilization Research in Interior British Columbia; Technical Report; Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2017; Volume 111. Available online: www.for.gov.bc.ca/hfd/pubs/Docs/Tr/Tr111.htm (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Bracho, R.; Vogel, J.G.; Will, R.; Martin, T.A.; Noormets, A.; Samuelson, L.J.; Jokela, E.J.; Gonzalez-Benecke, C.A.; Gezan, S.A.; Markewitz, D.; et al. Carbon accumulation in loblolly pine plantations is increased by fertilization across a soil moisture availability gradient. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 424, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetsonen, J.; Laurén, A.; Peltola, H.; Muhonen, O.; Nevalainen, J.; Ikonen, V.-P.; Kilpeläinen, A.; Tuittila, E.-S.; Männistö, E.; Kokkonen, N.; et al. Effects of nitrogen fertilization on the ground vegetation cover and soil chemical properties in Scots pine and Norway spruce stands. Silva Fenn. 2024, 58, 23058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörgensen, K.; Granath, G.; Strengbom, J.; Lindahl, B.D. Links between boreal forest management, soil fungal communities and below-ground carbon sequestration. Funct. Ecol. 2021, 35, 2637–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, L.; Nilsson, T. Duration of forest fertilization effects on streamwater chemistry in a catchment in central Sweden. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 496, 119450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manninen, O.H.; Myrsky, E.; Tolvanen, A.; Stark, S. N-fertilization and disturbance exert long-lasting complex legacies on subarctic ecosystems. Oecologia 2024, 204, 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson Belyazid, U.; Belyazid, S.; Akselsson, C. Pests and Pathogens in Boreal Forest Ecosystems—An Overview of Their Influence on the Carbon Balance of Trees and the Impact of Climate Change and Nitrogen Fertilization on Disease Development; Belyazid Consulting and Communication AB: Malmö, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Fang, S.; Fang, X.; Jin, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Lin, F.; Liu, J.; Ma, J.; Nie, Y.; Ouyang, S.; et al. Forest understory vegetation study: Current status and future trends. For. Res. 2023, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Zhang, X.; Yi, H.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; He, J.; He, L. Plant diversity drives soil carbon sequestration: Evidence from 150 years of vegetation restoration in the temperate zone. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1191704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haritika; Negi, A.K. The underestimated role of understory vegetation dynamics for forest ecosystem resilience: A review. Plant Ecol. 2025, 226, 763–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Ni, D.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, Q.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, H. Herbaceous Vegetation in Slope Stabilization: A Comparative Review of Mechanisms, Advantages, and Practical Applications. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanowicz, A.M.; Kapusta, P.; Stanek, M.; Rola, K.; Zubek, S. Herbaceous plant species support soil microbial performance in deciduous temperate forests. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 794, 151313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliam, F.S. The ecological significance of the herbaceous layer in temperate forest ecosystems. BioScience 2007, 57, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, S.; Tschapka, M.; Heymann, E.W.; Heer, K. Vertical stratification of seed-dispersing vertebrate communities and their interactions with plants in tropical forests. Biol. Rev. 2020, 95, 1429–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, K.J.; Harper, C.A.; Collins, B. Herbaceous Response to Type and Severity of Disturbance. In Sustaining Young Forest Communities; Greenberg, C.H., Collins, B., Thompson, F.R., Eds.; Managing Forest Ecosystems; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 21, pp. 105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Petrokas, R.; Manton, M. Adaptive Relationships in Hemi-Boreal Forests: Tree Species Responses to Competition, Stress, and Disturbance. Plants 2023, 12, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.J.; Givnish, T.J. Fine-scale environmental heterogeneity and spatial niche partitioning among spring-flowering forest herbs. Am. J. Bot. 2021, 108, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlandson, S.K.; Bellemare, J.; Moeller, D.A. Limited range-filling among endemic forest herbs of eastern North America and its implications for conservation with climate change. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 751728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.A.; Watling, J.R. Sunlight: An all-pervasive source of energy. In Plants in Action: Adaptation in Nature, Performance in Cultivation; Atwell, B.J., Kriedemann, P.E., Turnbull, C.E., Eds.; Web Edition 2011; Macmillan Education Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 1999; pp. 380–397. [Google Scholar]