Abstract

Plastic pollution, particularly in marine environments, has become a major global concern; therefore, monitoring and controlling these contaminants is essential to safeguard ecosystem integrity and human health. This study evaluates the ability of Posidonia oceanica spheroids to incorporate and retain plastic debris, with a particular focus on microplastics (MPs). A total of 1300 spheroids were collected along the Latium coast (Central Italy); among these, 454 (34.9%) contained plastic debris, with an average of 3.1 items per spheroid. Overall, 1415 plastic items were extracted and identified. Based on size classification, 48.7% were microplastics, 29.6% mesoplastics, and 21.9% macroplastics. Plastic items mainly consisted of filaments (40.9 ± 12.6%) and fibers (21.5 ± 5.2%). Eleven different colors were recorded, with white (28.8 ± 9.1%), transparent (13.4 ± 6.0%), and black (11.1 ± 6.8%) being the most frequent. A strong correlation was observed between the number of plastic items contained in the spheroids and proximity to wastewater treatment plants, which are known sources of synthetic fibers. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) identified a total of 15 polymer materials, with nylon (18.2 ± 11.0%) and polyethylene terephthalate (PET; 17.3 ± 7.2%) being the most abundant. Structural alterations observed in FTIR spectra, together with carbonyl index values, indicate that most MPs are of secondary origin, resulting from prolonged environmental degradation. These results demonstrate that P. oceanica spheroids effectively promote plastic trapping and highlight their potential as a simple and cost-effective monitoring tool for marine plastic pollution.

1. Introduction

Plastic pollution, particularly in marine environments, has become a major global issue. Without effective improvements in waste management, large amounts of plastic continue to enter the environment each year. Since the first observation of plastic debris in the Sargasso Sea in the 1970s [1], the problem has rapidly escalated, culminating in the formation of large accumulation zones, such as the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch”, which, according to some estimates, accumulates between 1.1. and 3.6 trillion plastics weighing 79,000 tonnes [2]. To monitor this phenomenon, over the past fifty years, hundreds of scientific papers have reported data regarding plastic diffusion everywhere, also using bioindicators after an appropriate selection of both species and matrices [3].

Among the different forms of plastic pollution, microplastics (MPs), plastic particles smaller than 5 mm, are of particular concern due to their ability to infiltrate the food web and eventually reach humans. These particles originate both from the fragmentation of larger plastic waste due to photochemical and mechanical degradation [4] and from primary sources such as cosmetics, synthetic textile fibers, and industrial activities [5].

High concentrations of microplastics have been detected in the Mediterranean Sea [6], one of the most enclosed and human-impacted basins worldwide. Large quantities of MPs in coastal sediments are mainly correlated to human population density or the presence of sources, such as wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), although not originally designed to handle microplastics, indicating that the nearshore area is an important sink of MPs coming from local sources, such as the river mouths [7,8].

Monitoring and controlling these contaminants is, therefore, essential for safeguarding both ecosystem integrity and human health. Numerous analytical methods have been developed to detect and quantify microplastics, covering all trophic levels, from plankton to top predators, and even in remote areas, aquatic or terrestrial ecosystems such as polar snowfalls [9,10,11,12]. Microplastics have been found in the digestive tracts and tissues of a wide variety of marine and terrestrial species, underscoring their pervasive presence [13,14].

A relatively novel approach to monitoring microplastics could involve the use of Posidonia oceanica (PO) spheroids—centimeter-sized, light-brown-colored aggregates, commonly called “sea balls”, “sea potatoes”, “Neptune balls”, or Aegagropilae (AG) [15]. The term derives from ancient Greek words with the meaning of “wild goat” and “fur” referring to the balls regurgitated by goats [16]. The composition and formation mode of these unique vegetation formations were tentatively first described by Ganong in 1909 [17]. Aegagropiles form when fibrous remains of dead seagrass leaf sheaths are rolled along the seabed by currents, behaving similarly to a “tumbleweed”. These naturally formed fibrous aggregates can entrap and retain plastic particles within their dense networks, effectively capturing and removing them from the seabed and the water column [15,18].

Posidonia oceanica is an endemic seagrass species of the Mediterranean Sea with long (up to 1.5 m) and thin leaves, forming extensive underwater meadows that provide shelter and nourishment for approximately 25% of the basin’s marine flora and fauna. These meadows can extend from shallow waters to depths of about 40 m [19]. Unlike algae, it is a true plant with roots, stems, flowers, and fruits; it is estimated that PO covers more than 2% of the seabed [20]. Among the marine plants, Posidonia oceanica is one of the most extensively studied seagrass species in the Mediterranean Sea, probably because it plays a crucial ecological role by producing large amounts of oxygen and organic matter (approximately 500 g dry weight·m−2·year−1) useful for seafloor stabilization and in protecting coastlines from erosion caused by wave action and carbon sequestration [19,20]. Several studies have reported an enrichment of MPs within seagrass meadows compared to adjacent non-vegetated seafloor [21], as well as a direct linkage between intense anthropogenic activity and high plastic contamination in coastal marine ecosystems such as seagrass meadows [22].

However, PO meadows are highly sensitive to anthropogenic pressures, such as coastal development, habitat fragmentation, and bottom trawling, which significantly reduce their distribution. It has been estimated that between 13 and 50% of their potential distribution surface may have been lost since 1960 [23]. Because of their ecological importance, Posidonia oceanica meadows are classified as a key habitat in Mediterranean coastal ecosystems. The species is listed in Annex II of the Barcelona Convention (endangered or threatened species) and in Annex I of the Bern Convention (strictly protected flora species). In addition, PO has been selected as a mark for assessing the Good Environmental Status of marine habitat under the Maritime Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD, 2008/56/EC). In Italy, mapping conducted between 1990 and 2005 estimated a total coverage of approximately 300,000 hectares, with a continuous distribution along the Tyrrhenian coast [24].

Essentially, Posidonia spheroids are found along many coastlines and can transport millions of plastic fragments to the shore, suggesting that they may serve as a natural, low-cost tool for monitoring microplastic pollution in marine ecosystems. By analyzing the plastic debris trapped within these spheroids, it is possible to estimate the spatial distribution and intensity of microplastic contamination across different coastal areas. Moreover, such findings may contribute to the development of strategies aimed at reducing plastic input and mitigating its environmental impacts.

The scope of this work was to investigate the ability of Posidonia oceanica spheroids to incorporate microplastics during their formation on the seabed and to evaluate their potential application as bioindicators of marine plastic pollution.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

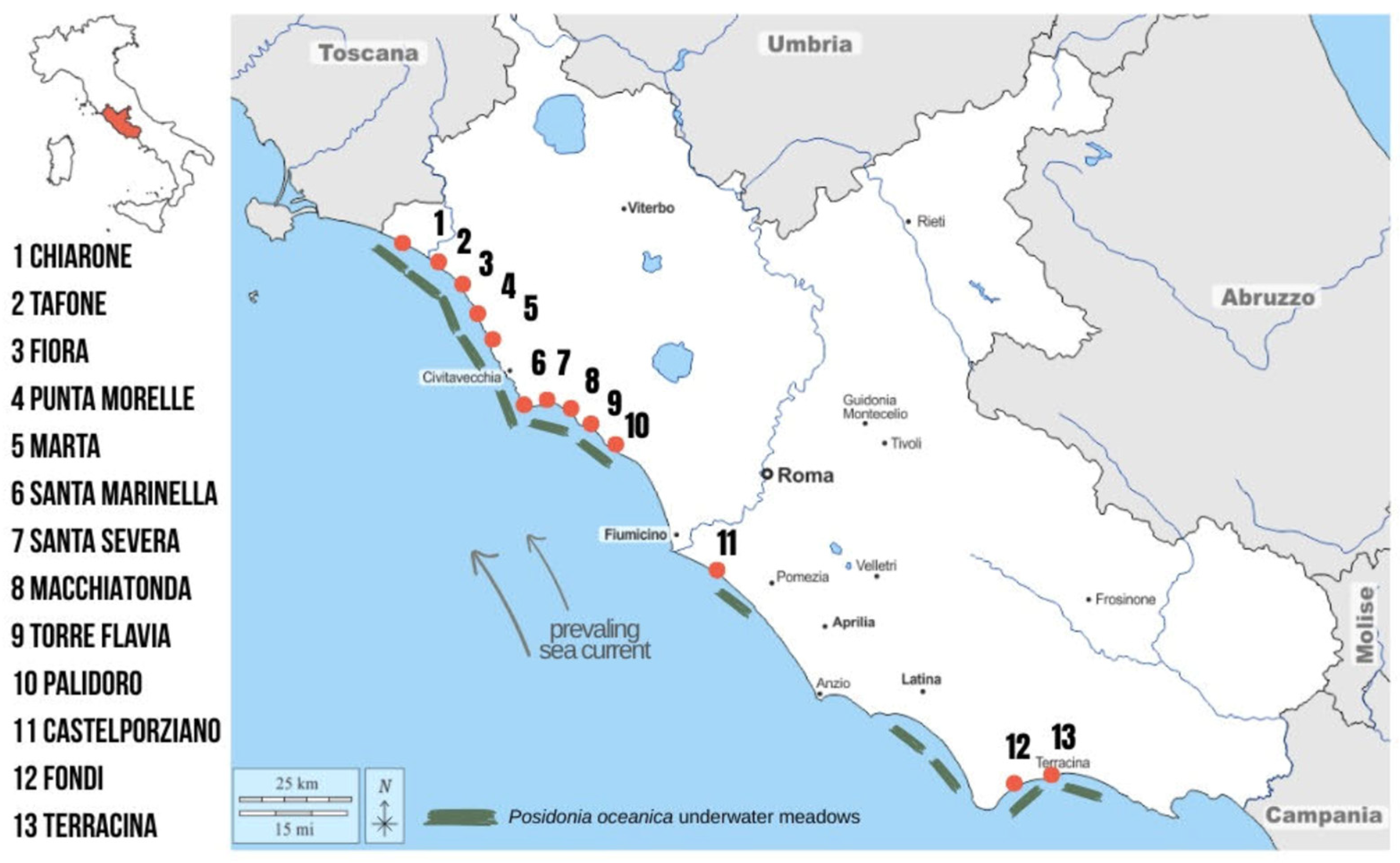

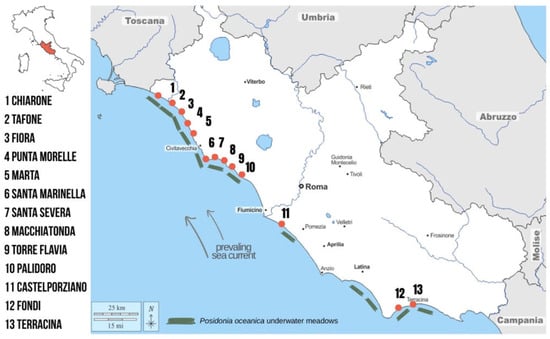

Aegagropiles (AGs) were manually collected from 13 sites along the Latium coastline during spring (Figure 1; GPS coordinates are reported in Table S1). Sampling sites were selected based on the spatial distribution of Posidonia oceanica meadows along the coastline [25].

Figure 1.

Sampling site and Posidonia oceanica distribution along the Latium coast.

At each beach, 1 m2 quadrats were randomly positioned within a coastal strip of approximately 1 km length and 5 m width, starting from the shoreline. Within each quadrat, all AGs were collected until a total of 100 spheroids per site was reached. As the aegagropiles were collected intact from the beach surface and none were taken from banquettes (natural beach accumulations of dead seagrass leaves, rhizomes, and other organic debris), it is reasonable to assume that the collected AGs represent short-term accumulation.

Samples were placed in metal-mesh baskets and transported to the laboratory for further analysis.

2.2. Spheroid Measurements and Plastic Extraction

Once in the laboratory, each spheroid was first measured using a digital caliper to calculate the volume, assuming an ellipsoid shape. Volume was calculated using the standard ellipsoid formula:

Following measurement, spheroids were carefully opened and manually disaggregated to remove the entrapped sand and debris. Subsequently, following a visual investigation carried out with a stereomicroscope (Leica KL 200 Led, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), the identified plastic items were extracted. The sorted items were washed in distilled water to remove residual sand and salt, air-dried under natural conditions, and then transferred to a Petri dish containing a white graph paper background to facilitate the determination of size and color. Furthermore, the items were classified according to morphology (fragment, film, fiber, pills, and filament), color, and maximum linear dimension. Fibers and filaments were distinguished according to their thickness. Plastic items were subsequently classified according to size into microplastics (<5 mm), mesoplastics (5 mm to 2.5 cm), and macroplastics (>2.5 cm), following established classification criteria [26].

2.3. Polymer Characterization

A subset representing 35% of the total samples (500 of 1415 total plastic pieces) was analyzed to identify the polymer matrices. Samples were selected using a proportional random sampling strategy. Plastic items were divided into homogeneous subgroups using the manual quartering method [27].

In this study, plastic pieces smaller than 0.2 mm were excluded from analysis due to the instrumental detection limit (≈0.3 mm). MP particle characterization refers to the principal chemical component of the polymer; therefore, characterization of the samples was carried out by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) using a Thermo-Fisher Scientific Nicolet iS5 6700 spectrophotometer (Waltham, MA, USA). The measurements were carried out in attenuated total reflection (ATR) with the use of a single reflection ATR accessory (model Golden Gate Single Reflection ATR System). For each particle, the FTIR spectra were collected in the spectral range from 4000 cm−1 to 550 cm−1, with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 20 co-added spectra accumulations per scan. Polymers were identified by comparison with the spectra database in the reference library of the instrument using OMNIC™-32 Specta Software, (version 2.1.175) considering a match score ≥85% as acceptable similarity [28].

2.4. Assessment of Polymer Degradation

Following the degradation processes, new peaks appeared on the FTIR spectrum: a peak at a region of 3300–3400 cm−1 (-OH, hydroxyl groups), at 1650–1800 cm−1 (C=O, carbonyl groups; visible in ketones, carboxylic acids, and esters; and centered for saturated compounds at 1715 cm−1), at 1600–1680 cm−1, at 909 cm−1 (C=C, carbon double bonds), and 1000–1250 cm−1 (C-O-C, ether groups). The appearance of carbonyl groups is a sign of oxidation of polyolefins, which accelerates the degradation process. Therefore, using the FTIR spectrum, the polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) degradation was quantified using the carbonyl index (CI = A(1720)/A(722)) that was calculated using the absorption band at 1720 cm−1, with the stretching vibration of the carbonyl group (C=O) while the absorbance at 722 cm−1 used as reference [4,29]. CI values were calculated as the average of at least ten randomly selected PE and PP microplastic items.

Regarding other polymers, such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), and polystyrene (PS), the ATR-FTIR was used to determine any possible functional groups on the surface of the polymer samples, which could be attributed to environmental degradation, such as carbonyl or hydroxyl groups. Spectra were compared with those of corresponding virgin polymer materials.

2.5. Quality Assurance and Contamination Control

To prevent MP contamination, all laboratory procedures were conducted using clean cotton laboratory coats, glass, and stainless-steel equipment. Laboratory surfaces and equipment were cleaned using 70% ethanol and rinsed with distilled water prior to use [30]. During sample processing, beakers filled with distilled water were placed near the working area to detect potential airborne contamination. Prior to use, filters were inspected by a stereomicroscope to ensure the absence of plastic particles. During the stereomicroscope observation of samples, a clean and uncovered Petri dish containing a clean filter was positioned near the operator to detect airborne MP deposition. Additionally, to prevent airborne contamination, all Petri dishes containing plastic items were immediately covered with aluminum foil after use.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

We compared the different sampling sites based on the frequency of occurrence (FO%) and abundance (number of plastic items per spheroid, item size, and type). To check for potential significant differences in the occurrence of plastic items between sites, we measured the Pearson correlation coefficient. Cluster analysis/dendrogram was used to quantify the similarity in terms of hierarchical relationship between data regarding the MPs diffusion in different sample structures. Paired-group UPGMA (Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean) using the Bray–Curtis coefficient of similarity was used to group items. Moreover, the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied to make the data more manageable and understandable by projecting it into a lower-dimensional space. Software PAST 4.1 was utilized to perform these analyses.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Occurrence and Abundance of Plastic Items in Aegagropiles

A total of 1300 Posidonia oceanica spheroids were collected along the Latium coast. Among these, 454 spheroids (34.9%) contained plastic debris, with an average of 3.1 items for each spheroid. In comparison, 52.8% were previously found along the beach of Torre Flavia, one of the sampling sites [15]. Overall, 1415 plastic items were extracted from AGs and identified. The main results related to the collected aegagropiles are summarized in Table 1. The average spheroid volume varies in the range 118.3–318.1 cm3; the largest volume found has V = 1236.1 cm3, while the smallest value was 6.3 cm3 (Figure 2). In some cases, significative differences in spheroid size were observed among sampling sites, likely reflecting variations in the spatial extent of the Posidonia oceanica meadows and their distance from the beach where the AGs were collected. However, no significant correlation was found between the spheroid size and the number of the entrapped plastic items (r = 0.31201, Pearson’s).

Table 1.

Main results as frequency of occurrence (%) and plastic items characteristics related to the collected aegagropiles. Sites: (1) Chiarone River, (2) Tafone River, (3) Fiora River, (4) Punta Le Murelle, (5) Marina Velca, (6) S. Marinella, (7) S. Severa, (8) Macchiatonda, (9) Torre Flavia, (10) Palidoro, (11) Castelporziano, (12) Fondi, and (13) Terracina.

Figure 2.

The largest and the smallest aegagropilae, and an example of an aegagropilae “aggregated” by shreds of fabric.

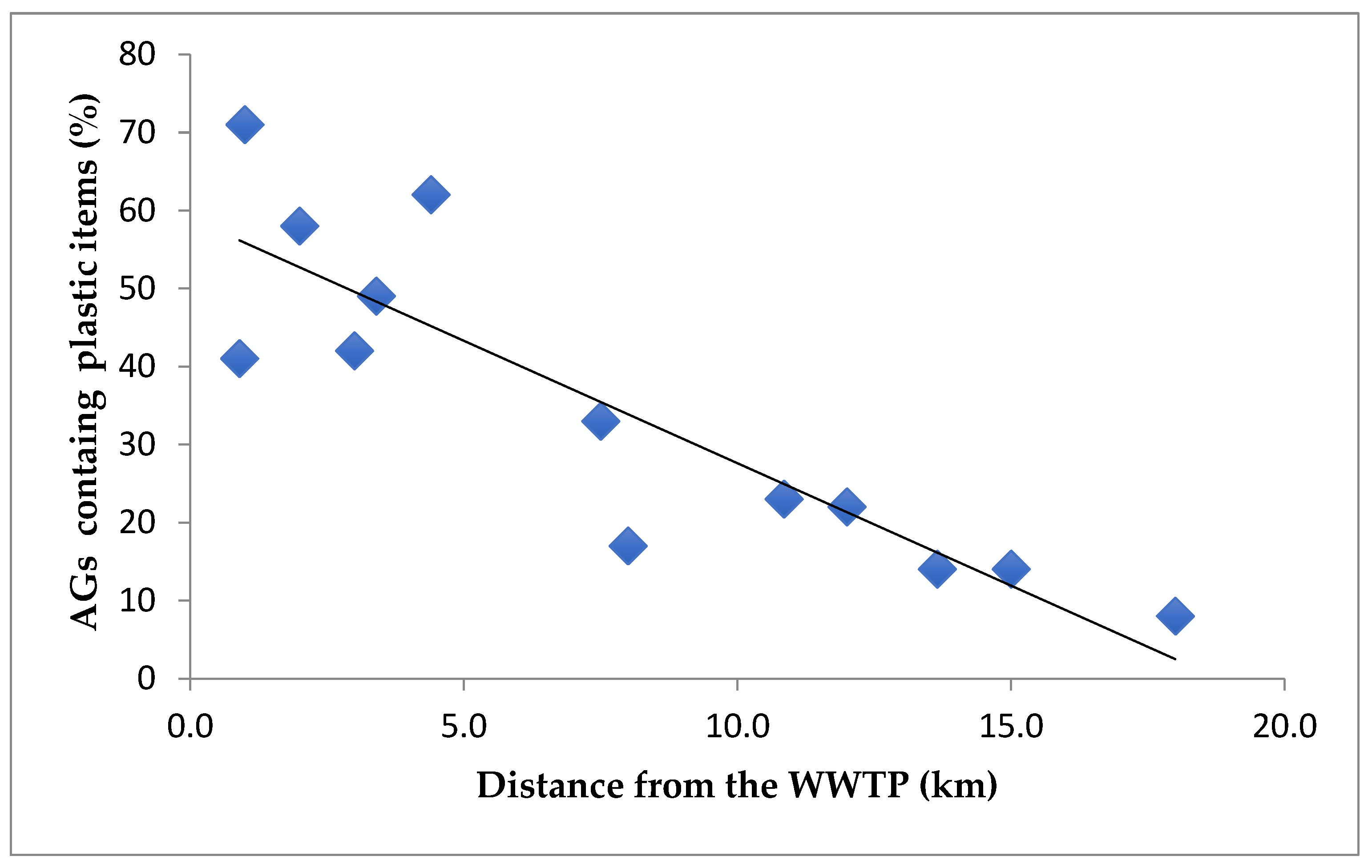

Considering the single sampling site, the observed frequency of microplastics presence varies in the range 8–71%, while the average number of plastic items per spheroid varied between 1.3 and 4.2. The highest number of items recorded within a single spheroid was 15, which was observed in a sample collected at a site located 1.6 km from the Terracina wastewater treatment plant (55,000 population equivalent). A possible explanation for these differences could be the proximity of the wastewater treatment plant.

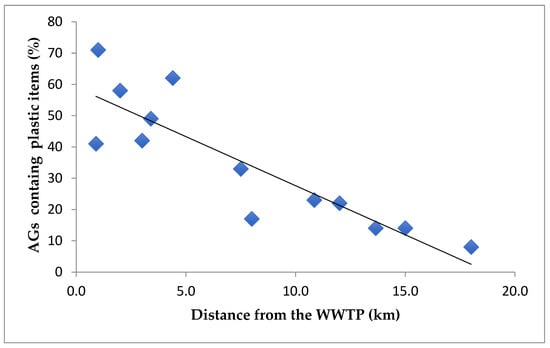

A strong correlation (r = 0.8651) was observed between the number of AGs containing plastic items and the distance from wastewater treatment plants, as shown in Figure 3. Given that WWTPs are distributed along the entire coastline, the influence of hydrodynamic conditions or sediment transport on this correlation can reasonably be considered negligible.

Figure 3.

Correlation between the distance of the wastewater treatment plant and the number of aegagropiles (AGs) containing plastic items (r = 0.8651).

During wastewater treatment processes, a substantial fraction of microplastics may bypass treatment stages and be released into the environment through treated effluents discharged into rivers or, in the case of coastal facilities, directly into the sea at distances of 1–2 km from the shoreline and at depths of approximately 30 m. WWTPs are therefore recognized as significant sources of microplastics, particularly fibers and pellets, owing to the large quantities of synthetic fibers released during textile washing processes, estimated to reach up to 700,000 fibers per wash [31].

3.2. Size Distribution of Plastic Items

Based on size classification, microplastics represented the largest fraction of plastic debris (average value 48.7% ± 12.7, min = 22.3%, and max = 64.4%), while mesoplastics and macroplastics average values were, respectively, 29.6 ± 7.1% (min = 18.1% and max = 42.3%) and 21.9 ± 10.7% (min = 8.4% and max = 44.4%) (Table 1). Macroplastics were mainly represented by filaments and fishing line fragments (Figure S1). Fishing lines, often abandoned or lost by fishermen during the recreation activity, pose a direct hazard to beach users and wildlife [32]. Over time, these materials undergo fragmentation, becoming microplastics that settle on the seabed and are subsequently incorporated into aegagropiles. Among microplastics, fragments of rope (mostly polypropylene) and shreds of synthetic fabric (mainly polyester) were frequently observed (Figure 2).

3.3. Morphological Characterization of Plastic Items

An analysis of the colors and shape of microplastics trapped in AGs revealed that the plastic items mainly consisted of filaments (average value of 40.9 ± 12.6%, min = 23.4% max = 65.7%) and fibers (average value of 21.5 ± 5.2%, min = 5.7% max = 31.5%) with a wide range of colors and size as summarized in Table 1. When fibers and pills, interpreted as small agglomerates of fibers, are considered together, they account for 82.9%. This strong predominance reflects the morphological similarity between plastic fibers and Posidonia oceanica fibers as previously highlighted [15,33,34]. In contrast, films and fragments together account for only 17.0% of plastic items. This proportion is significantly lower than values reported for the sea surface in the same sector of the Tyrrhenian Sea, where films and fragments exceed 90% of total plastic debris [35]. This discrepancy supports the hypothesis that aegagropiles selectively trap fiber-like plastic items, which are more likely to become entangled within their fibrous matrix [15].

Other parameters, including MP abundance, the proportion of fibers and pills, and their maximum number of items per spheroid, further confirm the influence of WWTP proximity. As previously reported [36], these results indicate that the number of items entrapped within the aegagropiles is correlated mainly to the number of plastic items along the seafloor and not to the spheroid size, as already explained. Seagrass meadows are known to promote plastic debris trapping [33,37], supporting the potential of aegagropiles as bioindicators of plastic pollution in benthic environments.

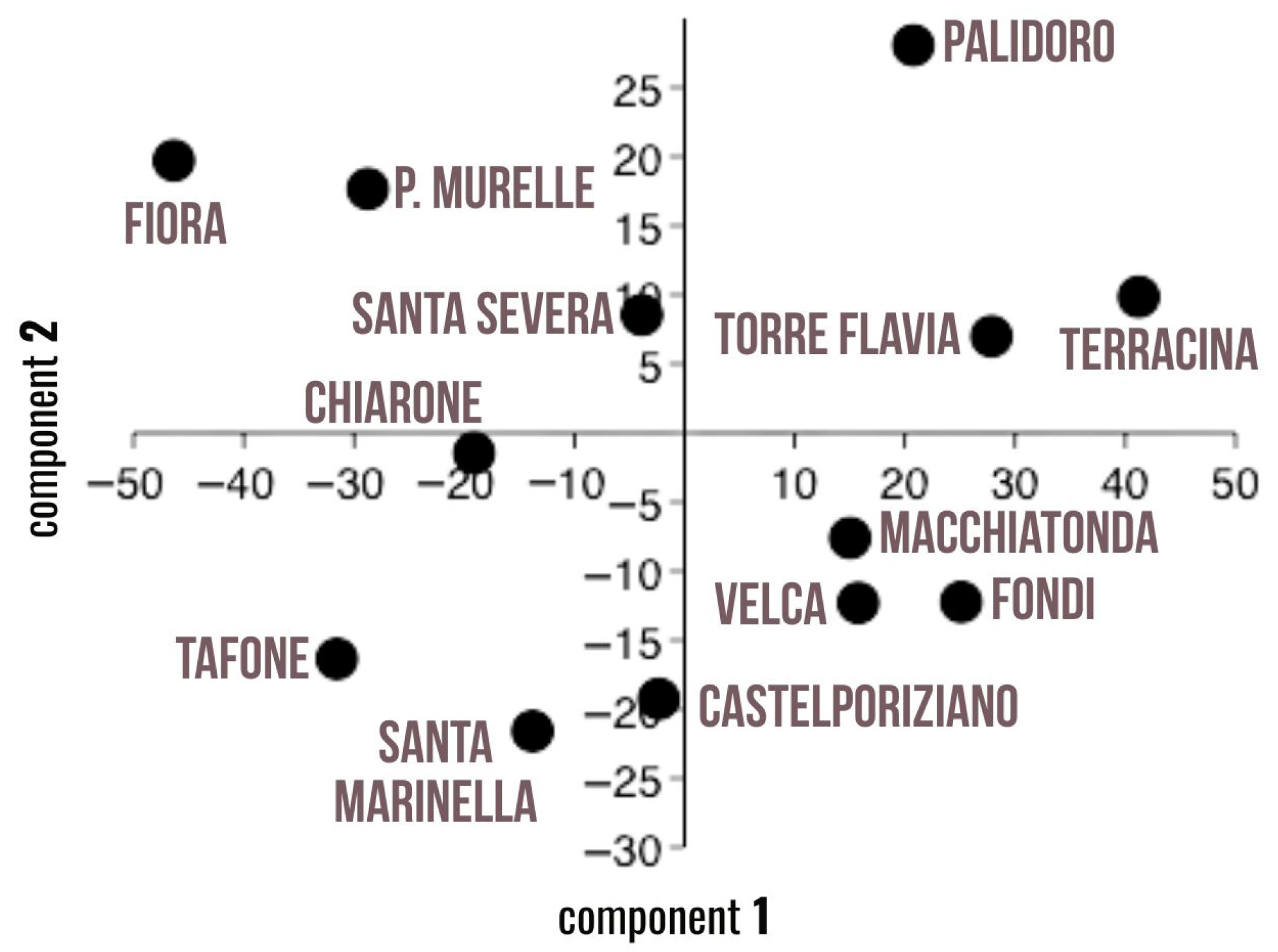

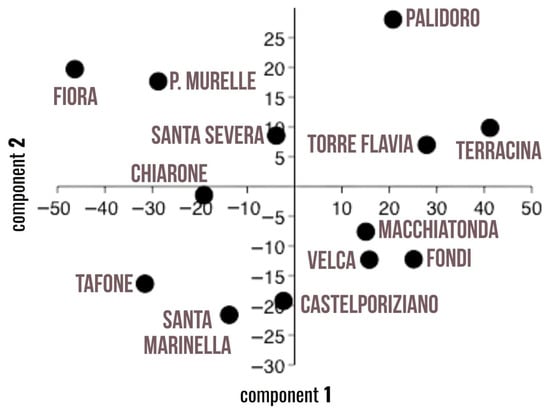

Principal component analysis (PCA), shown in Figure 4, further supported these findings. The first two principal components explained 78.1% of the total variance. In addition to the number of MPs/AG, as reported in Figure 3, variables such as frequency of occurrence, item size (micro), abundance of fibers, and pills were closely associated with the sites located nearest to wastewater treatment plants, Terracina, Palidoro, and Torre Flavia.

Figure 4.

Principal component analysis (PCA) regarding the morphological characterization of spheroids.

3.4. The Colors of Microplastics

A total of eleven different colors were identified among the microplastics recovered from aegagropiles. The most frequent colors were white (28.8 ± 9.1%), transparent (13.4 ± 6.0%), and black (11.1 ± 6.8%). Other authors have noted the prevalence of these colors in the spheroids [34,36,38] and within the Posidonia oceanica meadow sediments [22]. This result is consistent with findings at the sea surface, and ecological implications can be performed, as these items can be mistaken for prey species and ingested by marine organisms and seabirds, facilitating the transfer of microplastics and associated adsorbed pollutants into the human food chain [39].

Notably, all eleven colors were observed exclusively at sites located closest to WWTP discharges, where microplastic abundance was highest (up to 71% of spheroids containing plastic, with an average of 4.2 items per spheroid).

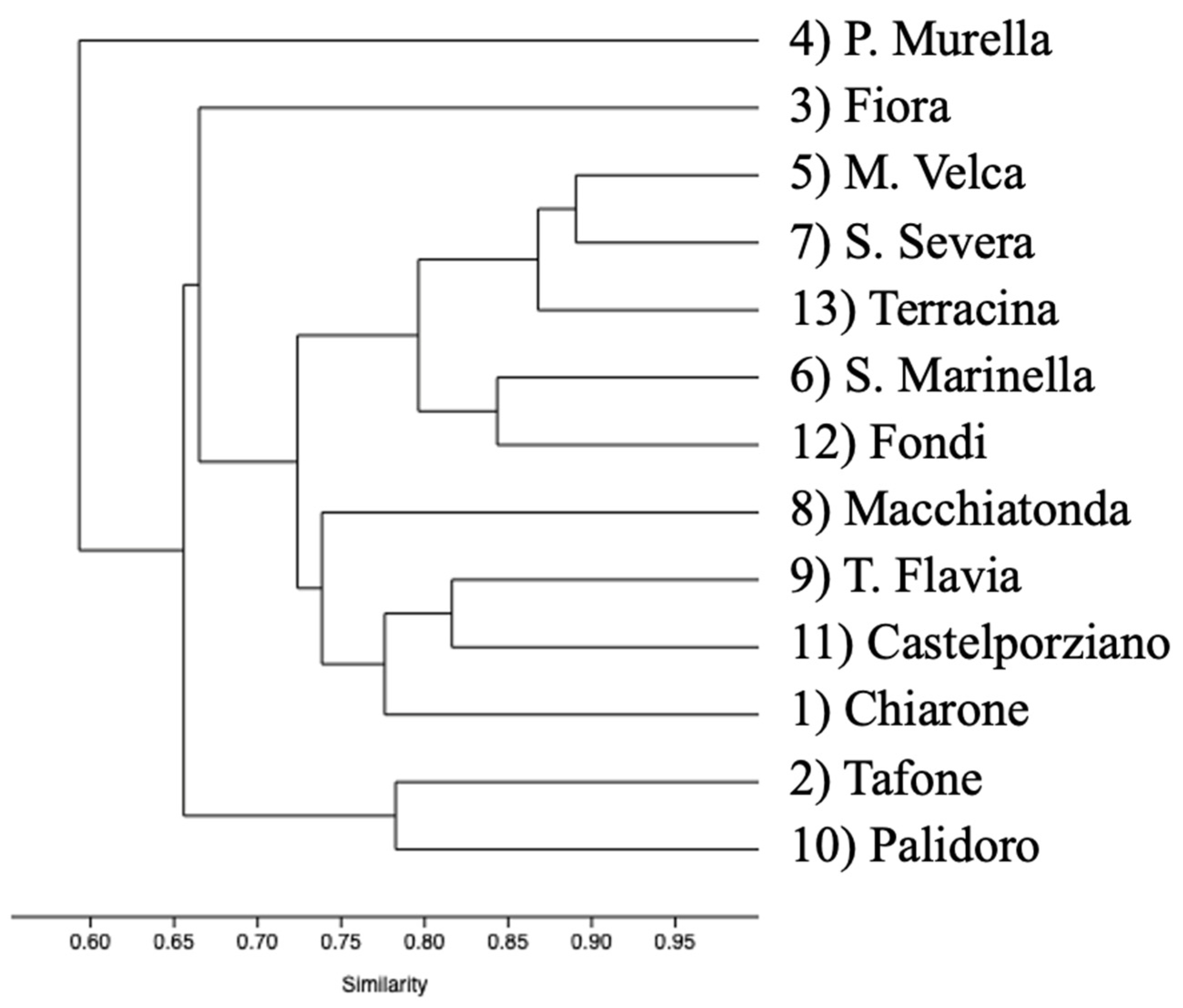

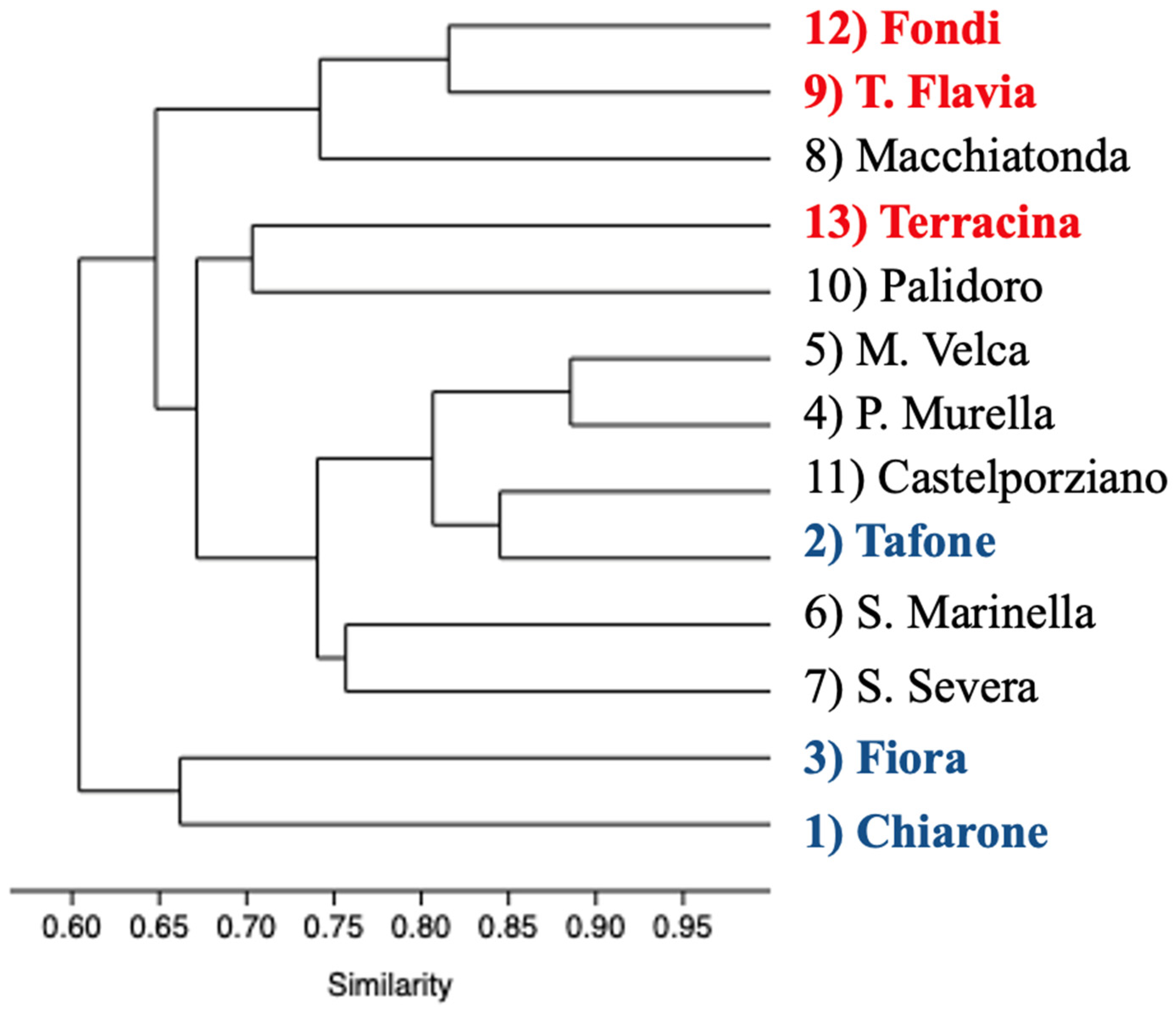

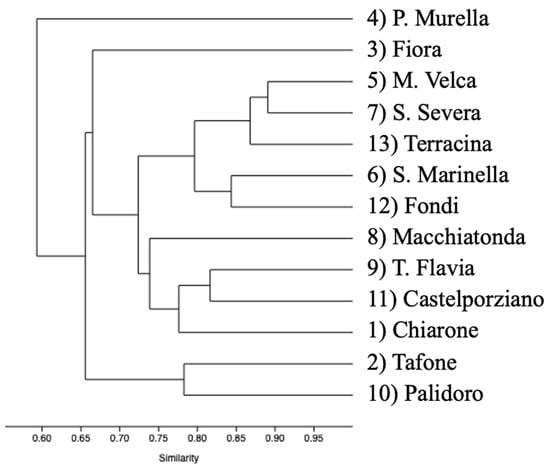

Dendrogram output for hierarchical clustering of polymer color groups performed using the percentage of MPs found in the spheroids collected in 13 sites shows a great similarity within sites (r = 0.8048); colors are directly related to the number of trapped microplastics, confirming that microplastics are randomly distributed inside the AG and therefore should be proportional to the presence on the seafloor (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Dendrogram representing the ordered relationship between polymer color groups.

3.5. Polymer Characterization

Polymer characterization was performed on a representative subset of 500 plastic items extracted from the aegagropiles (35% of the total). Overall, fifteen different polymer materials were identified (Table 2). The most abundant polymers were nylon (average value of 18.2 ± 11.0%) and polyethylene terephthalate (PET; average value of 17.3 ± 7.2%). In addition, PE, PP, PET, nylon, and PES (mainly as synthetic fibers) were found everywhere. In contrast, fragments of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE; d= 2.14–2.18 g/cm3), an excellent material in terms of resistance (applicable from −200 °C to +260 °C, great dielectric properties, and not hygroscopic), were found once (Figure S1). PTFE fibers were also found in seagrass soil sampled in Almeria [22].

Table 2.

Polymers in EG (%), Table 1 for site no. PE = polyethylene; PP = polypropylene; PU = polyurethane; PS = polystyrene; PET = polyethylene terephthalate; PES = polyester; PTFE = polytetrafluoroethylene; PVC = polyvinyl chloride; PBT = polybutylene terephthalate; PA = polyamide; FC = fluorocarbon; CA = cellulose acetate; and ABS = acrylonitrile butadiene styrene.

Comparable results have been reported in previous studies conducted in Mediterranean coastal environments; PET was identified as the dominant polymer in coastal areas of the Balearic Islands (14%) and Mallorca Island (35.1%) [33,36]. While nylon was the most common polymer within the leaves of Cymodocea rotundata observed in the Indian Ocean [40]. Given the high density (PET = 1.3–1.4 g/cm3 and nylon = 1.2–1.4 g/cm3), these polymers are expected to preferentially accumulate on the seafloor, where they become available for incorporation into aegagropiles. Among the polymeric materials identified, fluorocarbon polymers (d = 2.2–2.4 g/cm3) represent a noteworthy finding. These materials, commonly used for fishing lines due to their high strength and optical transparency in water, were detected at low relative abundance (1.8 ± 1.1%). Their limited occurrence may reflect their relatively recent introduction to the Italian market, beginning in the early 1990s, as well as their specific usage patterns.

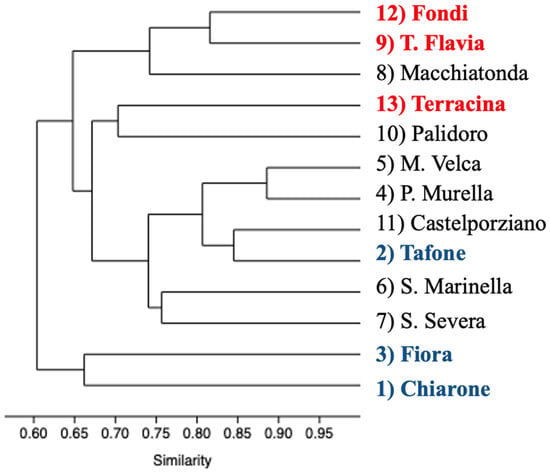

The cluster analysis of polymer composition revealed strong similarities among sites, particularly those characterized by a higher diversity of polymer materials (Figure 6). The greatest similarity (86.7%) was observed among sites exhibiting the highest number of polymeric materials (and the proximity to the WWTP), suggesting common sources and transport pathways of plastic debris within the study area.

Figure 6.

Dendrogram representing the hierarchical relationship between polymer materials groups. Red color: sites at less than 1.5 km from the WWTP. Blue color: sites at more than 15 km from the WWTP.

3.6. Evidence of Polymer Degradation

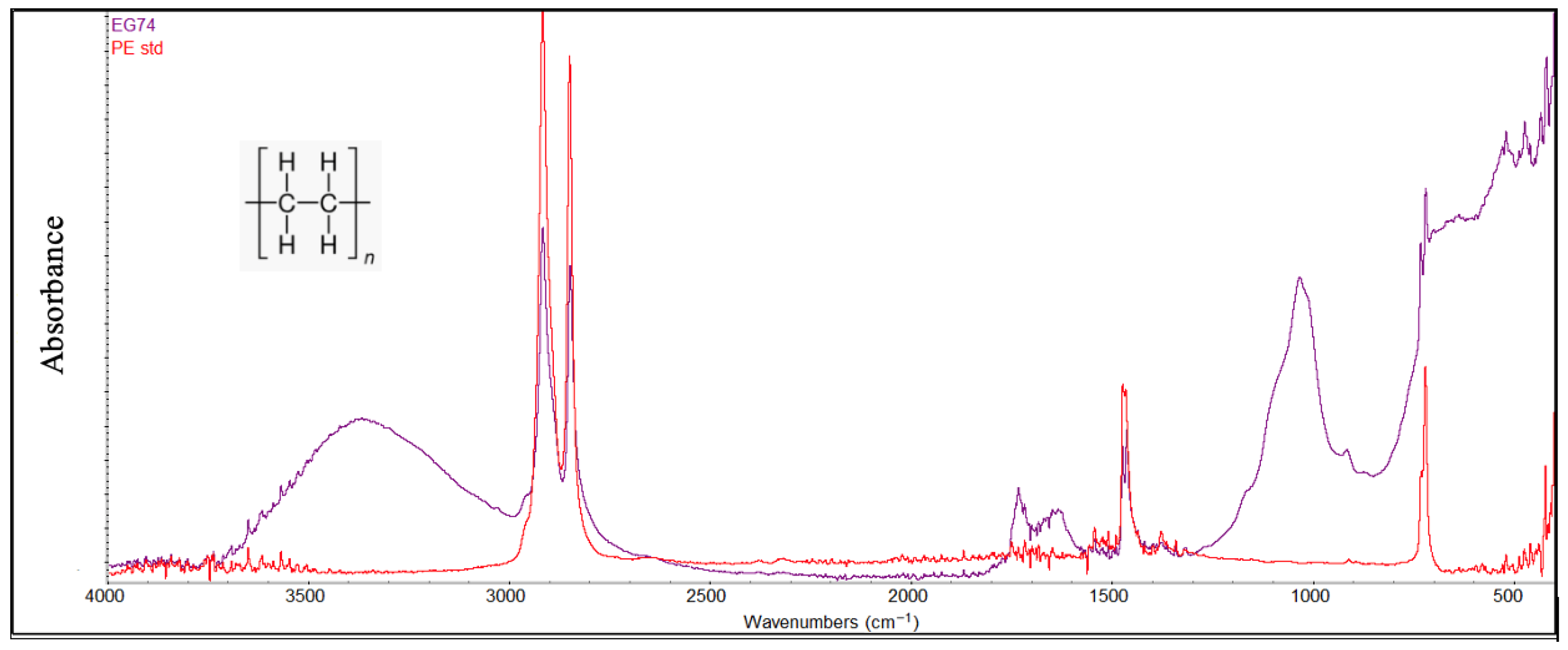

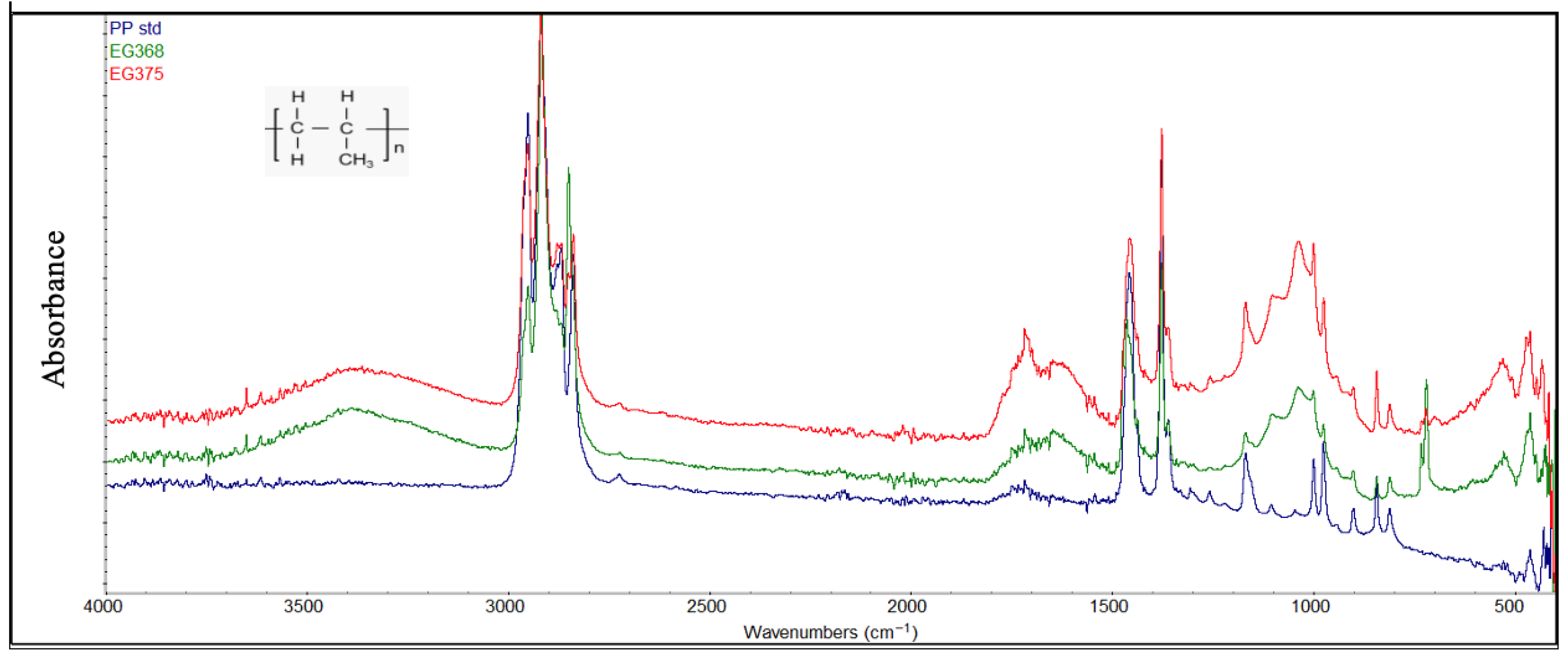

ATR-FTIR spectroscopy is a common technique that can be used to investigate the environmental degradation of polymers through the determination of any possible changes in the functional groups. The predominance of fibers and films among the most abundant plastic items suggests that the majority of microplastics are of secondary origin, resulting from the fragmentation and degradation of larger plastic objects. Consistent with this interpretation, carbonyl index values indicated that many plastic fragments originated from the degradation of macroplastics [4].

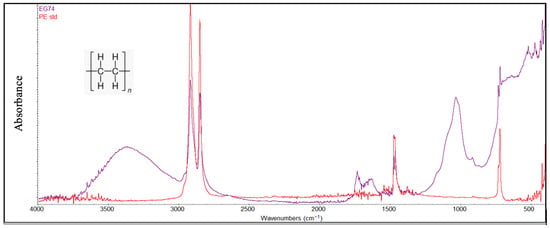

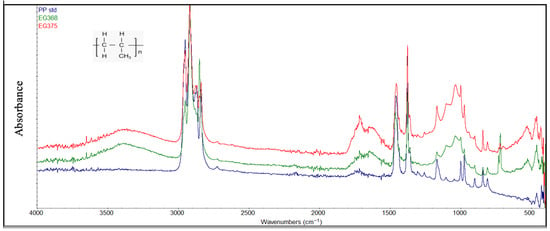

In general, FTIR analysis revealed that several polymer types, particularly polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP), exhibited clear signs of environmental degradation attributable to prolonged exposure to marine conditions and photodegradation processes (Figure 7 and Figure 8). Structural variations observed through the FTIR spectra of the degraded PE and PP were demonstrated by several peaks: in the region of 3300–3400 cm−1 attributable to hydroxyl groups (-OH), in the range of 1600–1800 cm−1 attributable to carbonyl groups (C=O), and in the range of 1000–1250 cm−1 characterized by the presence of the ether groups (C-O-C). The presence of these oxygen-containing groups is the consequence of photodegradation reactions due to simultaneous exposure to the sun and air. Further evidence of advanced degradation stages is provided by the carbonyl index values, which ranged from 0.2 to 0.5 for polyethylene and from 0.3 to 0.6 for polypropylene. These values are comparable to those reported in previous studies [4,41].

Figure 7.

An example of a PE sample degraded compared with a standard PE sample (red color).

Figure 8.

Samples of degraded PP compared with a standard PP sample (blue color).

An estimate of polymer mass loss due to degradation in the marine environment was obtained from polyethylene biofilm chips overflowed from a WWTP (southern Italy). In this case, a weight loss of 3.7 mg year−1 and a thickness reduction of 9.5 μm year−1 were calculated [4].

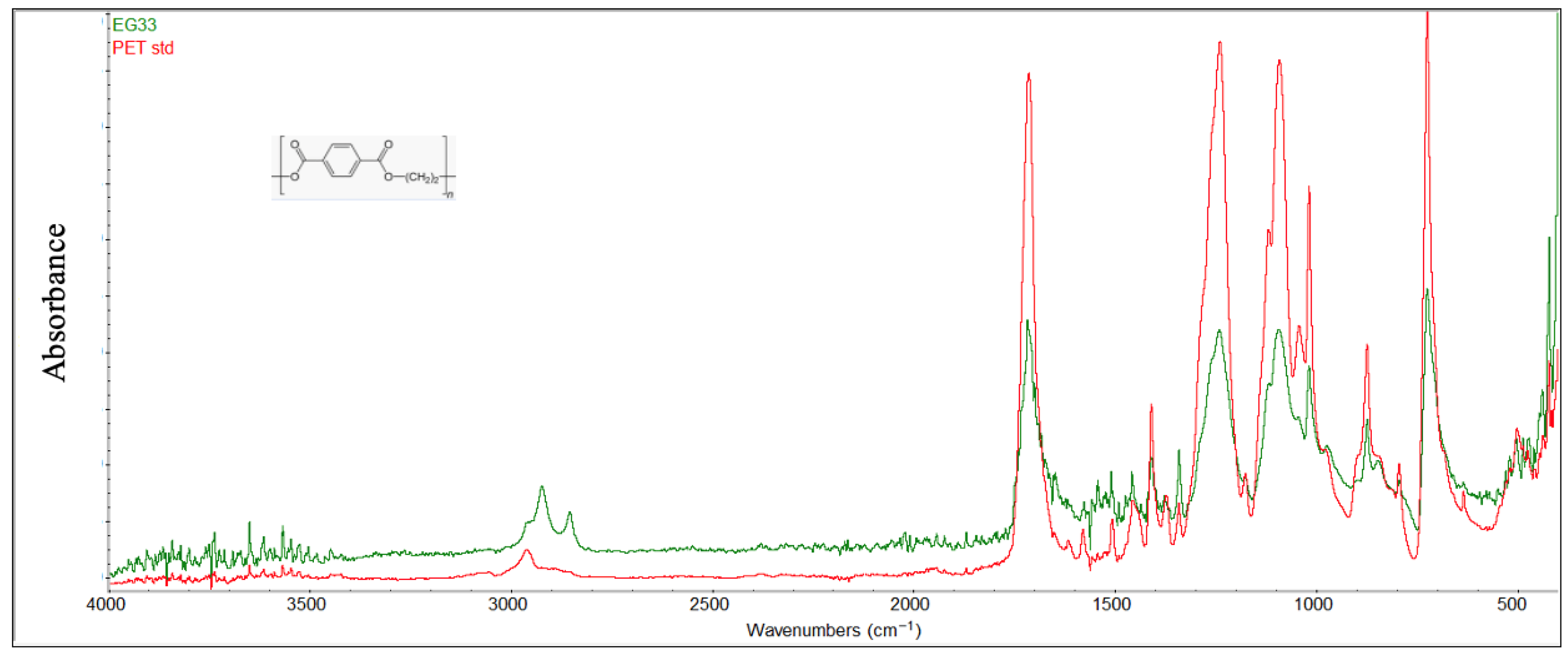

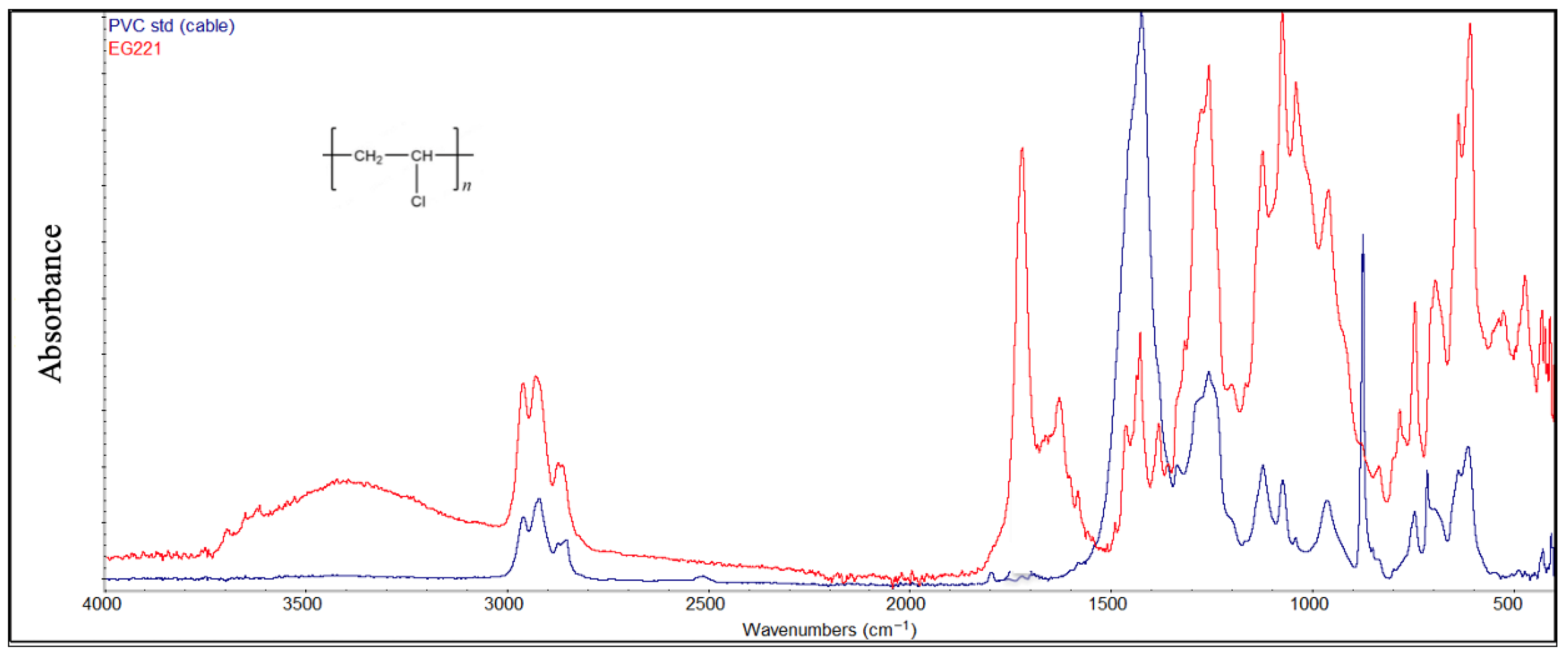

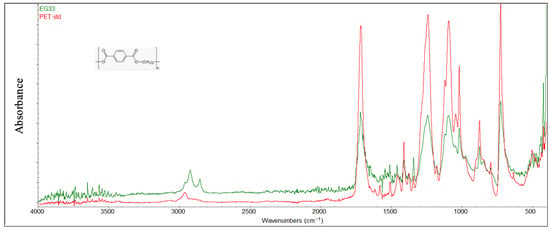

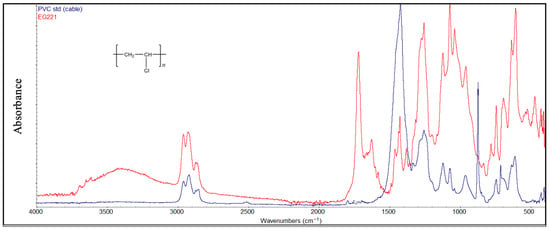

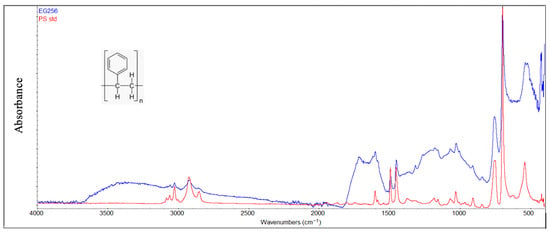

Other polymeric materials found in the aegagropiles showed clear signs of degradation, demonstrating that those objects had been in the sea or, in any case, in the environment for a long time. In the case of PET, PVC, and PS, the specific absorption peaks were analyzed from the FTIR spectra.

For PET samples (Figure 9), comparison with virgin material revealed the disappearance or attenuation of characteristic ester functional group peaks at 1715 cm−1 (ketones C=O stretching), 1245 cm−1 (ether aromatic C-O stretching), 1100 cm−1 (ether aliphatic C-O stretching), 870 cm−1 (banding aromatic C-H), and 730 cm−1 (wagging aromatic C-H). These changes are attributed to the hydrolytic degradation resulting from the prolonged interaction with seawater [42]. Additional peaks at around 2900 cm−1 in the FTIR spectrum were observed on the surface of the sample, indicating the presence of aliphatic structures (carbon chains without double bonds), specifically stretching vibrations of C-H bonds (methylenes -CH2- and methyls -CH3), with bands around 2850–2960 cm−1.

Figure 9.

Comparison between the degraded PET sample and virgin material (red color).

PVC samples (Figure 10) exhibit stronger peaks, which grow with degradation, at around 1730 cm−1 (C=O) as a result of oxidation forming ketones or carboxylic acids from the polymer backbone and at around 1600 cm−1 due to the conjugated double bonds (C=C-C=C) from HCl elimination. Moreover, at 3000–3500 cm−1, an OH-stretching enlarged peak appears due to hydrogen bonding as a marker for hydroperoxidic OH groups increasing with oxidation.

Figure 10.

Comparison between the degraded PVC sample and the virgin material (cable, blue color).

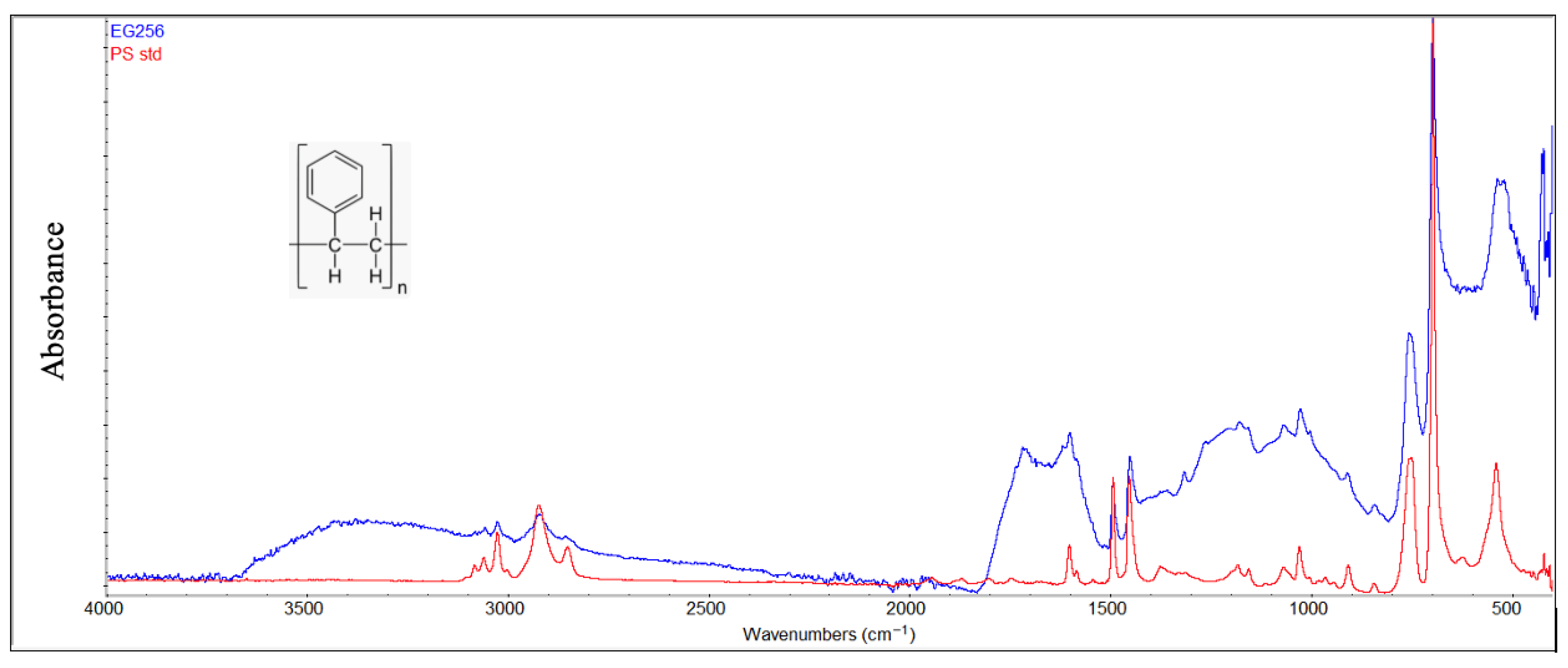

Infrared spectra of polystyrene samples (Figure 11) also showed the formation of hydroxyl and carbonyl groups because of environmental exposure. However, characteristic out-of-plane C-H bending and “ring-puckering” vibrations associated with monosubstituted benzene are clearly evident in the 750–690 cm−1 region, demonstrating that the main degradation occurs along the aliphatic portion of the macromolecule.

Figure 11.

Comparison between the degraded PS sample and virgin material (red color).

3.7. Implications for the Use of Aegagropiles as Microplastic Bioindicators

There is strong evidence that the seafloor constitutes a final sink for plastics from land sources, mainly across the rivers. Consequently, the identification of simple, reliable, and cost-effective methods for assessing plastic contamination in benthic marine environments is a key objective of environmental monitoring.

Bioindicators became essential to identify spatial trends and assign ecological risk. However, the application of a method depends on its cost-effectiveness (human resources, complexity, etc.) and simultaneously should ensure high reliability and accuracy of the results. In the Mediterranean Sea, some EU projects have employed bioindicator species such as sea turtles (Caretta caretta), fish species including red mullet (Mullus barbatus) and bogue (Boops boops), and mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) to evaluate plastic contamination [43]. Over the past decade, many studies reported plastic ingestion by several marine and coastal species [3].

Although AGs have been the subject of many archeological and geological studies, especially as indicators of coastal evolution in some areas of the Mediterranean Sea [44,45], the first reports regarding the identification of the most abundant polymers related to the plastic debris found within aegagropiles [15] have opened new perspectives for their application in microplastics research. Comparative analysis of available studies (Table 3) indicates consistently high proportions of aegagropiles containing microplastics across different Mediterranean regions, supporting the hypothesis that the seabed is heavily contaminated by this emerging pollutant. Furthermore, the extreme variability observed in both the percentage of AGs containing microplastics and the number of items per spheroid suggests that aegagropiles may provide quantitative information on local plastic contamination, as suggested by Figure 3. Nevertheless, further research is required to standardize sampling protocols and analytical methodologies before this approach can be routinely applied in monitoring programs.

Table 3.

Summary table of research studies regarding the MPs’ observation in EGs and banquettes derived from PO degradation. Mi = microplastics, Me = mesoplastics, Ma = macroplastics. nd=undetermined.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that Posidonia oceanica aegagropiles effectively trap plastic debris on the seafloor, confirming their potential use as a natural and reliable indicator of marine plastic pollution, particularly microplastics. Analysis of 1300 spheroids collected along 13 beaches of the Latium coast revealed that more than one-third contained plastic debris, with microplastics representing the dominant size class.

The results indicate that the number of plastic items entrapped within aegagropiles is primarily related to the abundance of plastic debris present on the seafloor rather than to spheroid size. A strong correlation was observed between plastic abundance in spheroids and proximity to wastewater treatment plants, which are known sources of synthetic fibers. This finding highlights the significant contribution of wastewater effluents to coastal microplastic contamination and emphasizes the need for mitigation measures, such as improved filtration systems in washing machines and upgrades to wastewater treatment technologies, which are not currently designed to effectively remove microplastics.

Morphological and chemical characterization of plastic items trapped within the fibrous structure of aegagropiles provided valuable information on polymer types, color distribution, and degradation state. The predominance of fibers and filaments, together with FTIR evidence of advanced polymer degradation and elevated carbonyl index values, indicates that most microplastics are of secondary origin, resulting from long-term environmental weathering of larger plastic objects.

Although the application of Posidonia oceanica aegagropiles as bioindicators of microplastic pollution is still in an early stage, this study demonstrates their strong potential as a simple, cost-effective, and environmentally relevant monitoring tool for benthic marine environments. Further research is required to standardize sampling methodologies and to quantitatively link plastic content in aegagropiles with ambient seafloor contamination levels.

Finally, the widespread availability of Posidonia oceanica aegagropiles along Mediterranean coastlines suggests promising opportunities for large-scale monitoring programs. Citizen science initiatives involving the collection of aegagropiles could complement traditional monitoring approaches, enhancing spatial coverage while simultaneously increasing public awareness of the environmental impacts associated with plastic pollution.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/environments13020071/s1. Figure S1: Fragments of fishing line; Figure S2: FTIR spectrum of polytetrafluoroethylene PTFE sample; Table S1: Coordinates of the sampling localities identified by GPS; and Table S2: PC1 and PC2 principal components data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M. and L.P.; methodology, P.M. and L.P.; validation, P.M. and L.P.; investigation, P.M. and L.P.; data curation, P.M. and L.P.; writing—original draft preparation, L.P.; writing—review and editing, L.P.; supervision, P.M. and L.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Francesca Lecce for technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Carpenter, E.J.; Smith, K.L. Plastics on the Sargasso Sea surface. Science 1972, 175, 1240–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cressey, D. Bottles, bags, ropes and toothbrushes: The struggle to track ocean plastics. Nature 2016, 536, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savoca, M.S.; Abreo, N.A.; Arias, A.H.; Baes, L.; Baini, M.; Bergami, E.; Brander, S.; Canals, M.; Choy, C.A.; Corsi, I.; et al. Monitoring plastic pollution using bioindicators: A global review and recommendations for marine environments. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2025, 4, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrelli, L. Fate of the biofilm chips overflowed from a wastewater treatment plant. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 200, 116142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitko, V.; Hanlon, M. Another source of pollution by plastics: Skin cleaners with plastic scrubbers. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1991, 22, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Sharma, V.; Chatterjee, S. Microplastics in the Mediterranean Sea, sources, pollution intensity, sea health and regulatory policies. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 634934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.A.; Crump, P.; Niven, S.J.; Teuten, E.; Tonkin, A.; Galloway, T.; Thompson, R. Accumulation of Microplastic on Shorelines Worldwide: Sources and Sinks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 9175–9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talvitie, J.; Heinonen, M.; Paakkonen, J.P.; Vahtera, E.; Mikola, A.; Setala, O.; Vahala, R. Do wastewater treatment plants act as a potential point source of Microplastics? Preliminary study in the coastal Gulf of Finland, Baltic Sea. Water Sci. Technol. 2015, 72, 1495e1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Allen, D.; Phoenix, V.R.; Le Roux, G.; Durántez Jiménez, P.; Simonneau, A.; Binet, S.; Galop, D. Atmospheric transport and deposition of microplastics in a remote mountain catchment. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napper, I.E.; Davies, B.F.; Clifford, H.; Elvin, S.; Koldewey, H.J.; Mayewski, P.A.; Miner, K.R.; Potocki, M.; Elmore, A.C.; Gajurel, A.P.; et al. Reaching new heights in plastic pollution-preliminary findings of microplastics on Mount Everest. One Earth 2020, 3, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales-Pleiter, M.; Edo, C.; Aguilera, A.; Viúdez-Moreiras, D.; Pulido-Reyes, G.; González-Toril, E.; Osuna, S.; de Diego-Castilla, G.; Leganés, F.; Fernández-Piñas, F.; et al. Occurrence and transport of microplastics sampled within and above the planetary boundary layer. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 761, 143213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, A.A.; Barnes, D.K.A. Microplastic pollution in a rapidly changing world: Implications for remote and vulnerable marine ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 738, 140349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancia, A.; Chenet, T.; Bono, G.; Geraci, M.L.; Vaccaro, C.; Munari, C.; Mistri, M.; Cavazzini, A.; Pasti, L. Adverse effects of plastic ingestion on the Mediterranean small-spotted catshark (Scyliorhinus canicula). Mar. Environ. Res. 2020, 155, 104876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorca, M.; Álvarez-Muñoz, D.; Ábalos, M.; Rodríguez-Mozaz, S.; Santos, L.H.; León, V.M.; Campillo, J.A.; Martínez-Gómez, C.; Abad, E.; Farré, M. Microplastics in Mediterranean coastal area: Toxicity and impact for the environment and human health. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2020, 27, e00090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrelli, L.; Di Gennaro, A.; Menegoni, P.; Lecce, F.; Poeta, G.; Acosta, A.T.R.; Battisti, C.; Iannilli, V. Pervasive plastisphere: First record of plastics in aegagropiles (Posidonia spheroids). Environ. Pollut. 2017, 229, 1032–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhille, G.; Moulinet, S.; Vandenberghe, N.; Adda-Bedia, M.; Le Gal, P. Structure and mechanics of aegagropilae fiber network. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 4607–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganong, W.F. On balls of vegetable matter from sandy shores. Rhodora 1909, 11, 149–152. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Xu, C.; Perianen, Y.D.; Hu, J.; Holmer, M. Seagrass beds acting as a trap of microplastics—Emerging hotspot in the coastal region? Environ. Pollut. 2020, 257, 113450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ondiviela, B.; Losada, I.J.; Lara, J.L.; Maza, M.; Galván, C.; Bouma, T.J.; van Belzen, J. The role of seagrasses in coastal protection in a changing climate. Coast. Eng. 2014, 87, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyanova, D.; Gullström, M.; Lyimo, L.D.; Dahl, M.; I Hamisi, M.; Mtolera, M.S.P.; Björk, M. Contribution of seagrass plants to CO2 capture in a tropical seagrass meadow under experimental disturbance. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozzolino, L.; Nicastro, K.R.; Zardi, G.; de los Santos, C.B. Species- specific plastic accumulation in the sediment and canopy of coastal vegetated habitats. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 723, 138018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, M.; Bergman, S.; Björk, M.; Diaz-Almela, E.; Granberg, M.; Gullström, M.; Leiva-Dueñas, C.; Magnusson, K.; Marco-Méndez, C.; Piñeiro-Juncal, N.; et al. A temporal record of microplastic pollution in Mediterranean seagrass soils. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 273, 116451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telesca, L.; Belluscio, A.; Criscoli, A.; Ardizzone, G.; Apostolaki, E.T.; Fraschetti, S.; Gristina, M.; Knittweis, L.; Martin, C.S.; Pergent, G. Seagrass meadows (Posidonia oceanica) distribution and trajectories of change. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanu, S.; Piazzolla, D.; Bonamano, S.; Penna, M.; Piermattei, V.; Madonia, A.; Manfredi Frattarelli, F.; Mellini, S.; Dolce, T.; Valentini, R.; et al. Economic Evaluation of Posidonia oceanica Ecosystem Services along the Italian Coast. Sustainability 2022, 14, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diviacco, G.; Spada, E.; Lamberti, C.V. Descrizione e cartografia delle praterie di Posidonia oceanica e dei prati di Cymodocea nodosa. In Le Fanerogame Marine del Lazio; ICRAM-ISPRA: Rome, Italy, 2001; pp. 1–113. [Google Scholar]

- Galgani, F.; Hanke, G.; Werner, S.; De Vrees, L. Marine litter within the European Marine Strategy Framework Directive. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2013, 70, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, R.W.; Dobb, D.E.; Raab, G.A.; Nocerino, J.M. Gy sampling theory in environmental studies. 1. Assessing soil splitting protocols. J. Chemometr. 2002, 16, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sighicelli, M.; Pietrelli, L.; Lecce, F.; Iannilli, V.; Falconieri, M.; Coscia, L.; Di Vito, S.; Nuglio, S.; Zampetti, G. Microplastic pollution in the surface waters of Italian Subalpine Lakes. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 236, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, P.K.; Surekha, P.; Rajagopal, C.; Chatterjee, S.N.; Choudhary, V. Studies on the photo-oxidative degradation of LDPE films in the presence of oxidized Polyethylene. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2007, 92, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, E.; Cicero, F.; Magliocchetti, I.; Menegoni, P.; Sighicelli, M.; Di Ludovico, A.; Le Foche, M.; Pietrelli, L. High Density of Microplastics in the Caddisfly Larvae Cases. Environments 2025, 12, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodzek, M.; Pohl, A.; Rosik-Dulewska, C. Microplastics in Wastewater Treatment Plants: Characteristics, Occurrence and Removal Technologies. Water 2024, 16, 3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, C.; Kroha, S.; Kozhuharova, E.; De Michelis, S.; Fanelli, G.; Poeta, G.; Pietrelli, L.; Cerfolli, F. Fishing lines and fish hooks as neglected marine litter: First data on chemical composition, densities, and biological entrapment from a Mediterranean beach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 1000–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Vidal, A.; Canals, M.; de Haan, W.P.; Romero, J.; Veny, M. Seagrasses provide a novel ecosystem service by trapping marine plastics. Sci. Rep. 2021, 14, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porcino, N.; Bottari, T.; Falco, F.; Natale, S.; Mancuso, M. Posidonia Spheroids Intercepting Plastic Litter: Implications for Beach Clean-Ups. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral-Zettler, L.A.; Ballerini, T.; Zettler, E.R.; Asbun, A.A.; Adame, A.; Casotti, R.; Dumontet, B.; Donnarumma, V.; Engelmann, J.C.; Frère, L.; et al. Diversity and predicted inter- and intra-domain interactions in the Mediterranean Plastisphere. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 286, 117439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomar, C.; Compa, M.; Fagiano, V.; Concato, M.; Deudero, S. Posidonia oceanica egagropiles: Good indicators for plastic pollution in coastal areas? Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2024, 77, 103653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Smit, J.C.; Anton, A.; Martin, C.; Rossbach, S.; Bouma, T.J.; Duarte, C.M. Habitat-forming species trap microplastics into coastal sediment sinks. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 772, 145520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afeniforo, T.; D’Iglio, C.; Borg, J.A.; Litvinenko, I.; Spanò, N.; Savoca, S. Posidonia oceanica wrack intercepts plastic debris: First evaluated evidence on Maltese beaches. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 90, 104439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmo-Gilabert, R.; Fagiano, V.; Alomar, C.; Rios-Fuster, B.; Compa, M.; Deudero, S. Plastic webs, the new food: Dynamics of microplastics in a Mediterranean food web, key species as pollution sources and receptors. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datu, S.S.; Supriadi, S.; Tahir, A. Microplastic in Cymodocea rotundata Seagrass Blades. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Biotech. 2019, 4, 1758–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tocháček, J.; Vrátníčková, Z. Polymer life-time prediction: The role of temperature in UV accelerated ageing of polypropylene and its copolymers. Polym. Test. 2014, 36, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioakeimidis, C.; Fotopoulou, K.; Karapanagioti, H.; Geraga, M.; Zeri, C.; Papathanassiou, E.; Galgani, F.; Papatheodorou, G. The degradation potential of PET bottles in the marine environment: An ATR-FTIR based approach. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossi, M.C.; Peda, C.; Compa, M.; Tsangaris, C.; Alomar, C.; Claro, F.; Ioakeimidis, C.; Galgani, F.; Hema, T.; Deudero, S.; et al. Bioindicators for monitoring marine litter ingestion and its impacts on Mediterranean biodiversity. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 237, 1023–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. Egagropili Sand Dunes (Holocene) along the southeastern Gulf of Sirte (Mediterranean Sea) coast of Brega, Libya. Geophytology 2022, 52, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pascucci, V.; De Falco, G.; Del Vais, C.; Sanna, I.; Melis, R.T.; Andreucci, S. Climate changes and human impact on the Mistras coastal barrier system (W Sardinia, Italy). Mar. Geol. 2018, 395, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sghaier, D.B.; Chniti, I.; Barhoumi-Slimi, T.; Zaaboub, N.; EL Bour, M. The trapping of microplastics in the Posidonia oceanica aegagropiles in Tunisian coastal areas—Southern Mediterranean. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1663783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, B.; Sghaies, D.B.; Matmati, E.; Mraoun, R.; El Bour, M. Detection and quantification of microplastics in Posidonia oceanica banquettes in the Gulf of Gabes, Tunisia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 57196–57203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.