Abstract

The main objective of this work is to assess the potential negative impact of organic farming on the thyroid gland and compare it with the negative impact of conventional farming on this organ. Previous studies have linked exposure to conventional farming with thyroid disruption; relatively less is known about effects of exposure to organic farming on the thyroid. Mus musculus were the bioindicators in this work, captured in a conventional farm (CF), an organic farm (OF), and two reference areas (RF’) without agriculture. Histomorphometric and histomorphological measurements of the thyroid were performed. Hypothyroidism signs were observed in mice exposed to either farming system, being less pronounced in organic farming-exposed mice: epithelium thickness and the epithelial cells’ area and volume were lower than in non-exposed mice [epithelium thickness (µm): 4.16 ± 0.51 (CF); 6.28 ± 0.19 (OF); 7.46 ± 0.25 (RF’)]. Histomorphologic alterations included decreased follicular sphericity, increased epithelium irregularity, increased exfoliation into the colloid, and increased inflammation of thyroid tissue. Results suggest that, while organic farming might be a better alternative to conventional farming, it is not completely free of health hazards. Exposure to an organic farming environment can cause thyroid disruption, although with less pronounced effects than conventional farming. Despite there being risks to be considered, results support the benefit of transitioning from conventional farming systems towards organic farming systems.

1. Introduction

Agriculture is among the most important anthropogenic activities, providing human populations with a steady supply of food, fuel, and fiber [1,2]. However, agriculture is one of the major causes of environmental pollution, adversely affecting ecosystem condition and human health—especially when involving the use of synthetic agrochemicals [3,4]. Based on the nature of approaches towards food and livestock production, agriculture is divided into two major systems: conventional farming (CF) and organic farming (OF). In essence, CF heavily relies on synthetic inputs (i.e., agrochemicals) to maximize yields, while OF excludes synthetic inputs to promote environmental sustainability [5,6]. Worldwide, CF is the dominant farming system [7]. By contrast, although growing, OF represents only about 1% of global cropland [8]. There is ongoing debate about whether OF is an overall better alternative to CF, particularly regarding the balance between production costs, yields, and the presence of hazardous substances in produce [9,10,11].

Conventional farming (also known as industrialized agriculture) refers to agricultural methods heavily reliant on synthetic inputs, such as the use of agrochemicals and genetically modified organisms (GMOs), to achieve the highest possible yields. Most modern agriculture systems rely on CF practices for production, due to a greater demand for food products resulting from a swift rise in world population numbers [12]. The presence of several cancer-promoting pesticide residues has been documented in CF food products, highlighting the serious health hazard associated with CF contaminants [13,14]. On the other hand, organic farming (also referred to as biological agriculture) is characterized by the exclusion of synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and GMOs in its practices. Organic farming prioritizes quality over quantity, with the aim of producing safer and healthier food products, despite relatively lower yields [15,16]. Focusing on environmental sustainability, OF employs techniques like the use of composting and manure as natural fertilizers, crop rotation, cover cropping, and biological pest control—i.e., the implementation of natural predators, parasites, and pathogens of pest populations—in its practices [17,18]. Data suggests that OF positively impacts the environment by promoting a decrease in nitrate leaching and in greenhouse gas emissions, along with increasing farmland biodiversity, and even promoting carbon sequestration via increasing soil organic matter [19]. According to Meng et al. (2017) [19], all these benefits compensate for the economic costs of a lower crop production.

The trend is for current CF systems to transition to OF ones, due to the perception that the latter are more beneficial for both the environment and humans. However, agrochemical residues, especially synthetic pesticide traces, are commonly detected in OF produce [20,21,22]. The review of Lazarević-Pašti et al. (2025) [22] points to the presence of pesticide residues in 28% of organic food in Southern Germany, 9% in the Swiss market, and 6% in the overall European market. Another problem is the fact that OF practices increase the amount and distribution of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in the environment. This is because the manure used as natural fertilizer often comes from livestock that has been treated with antibiotics, growth factors, and other substances [23,24,25]. Bacterial populations in the soil are exposed to these compounds, gain resistance towards them, and pass on the relevant genes both intra- (vertical gene transfer) and interspecies (horizontal gene transfer) [26].

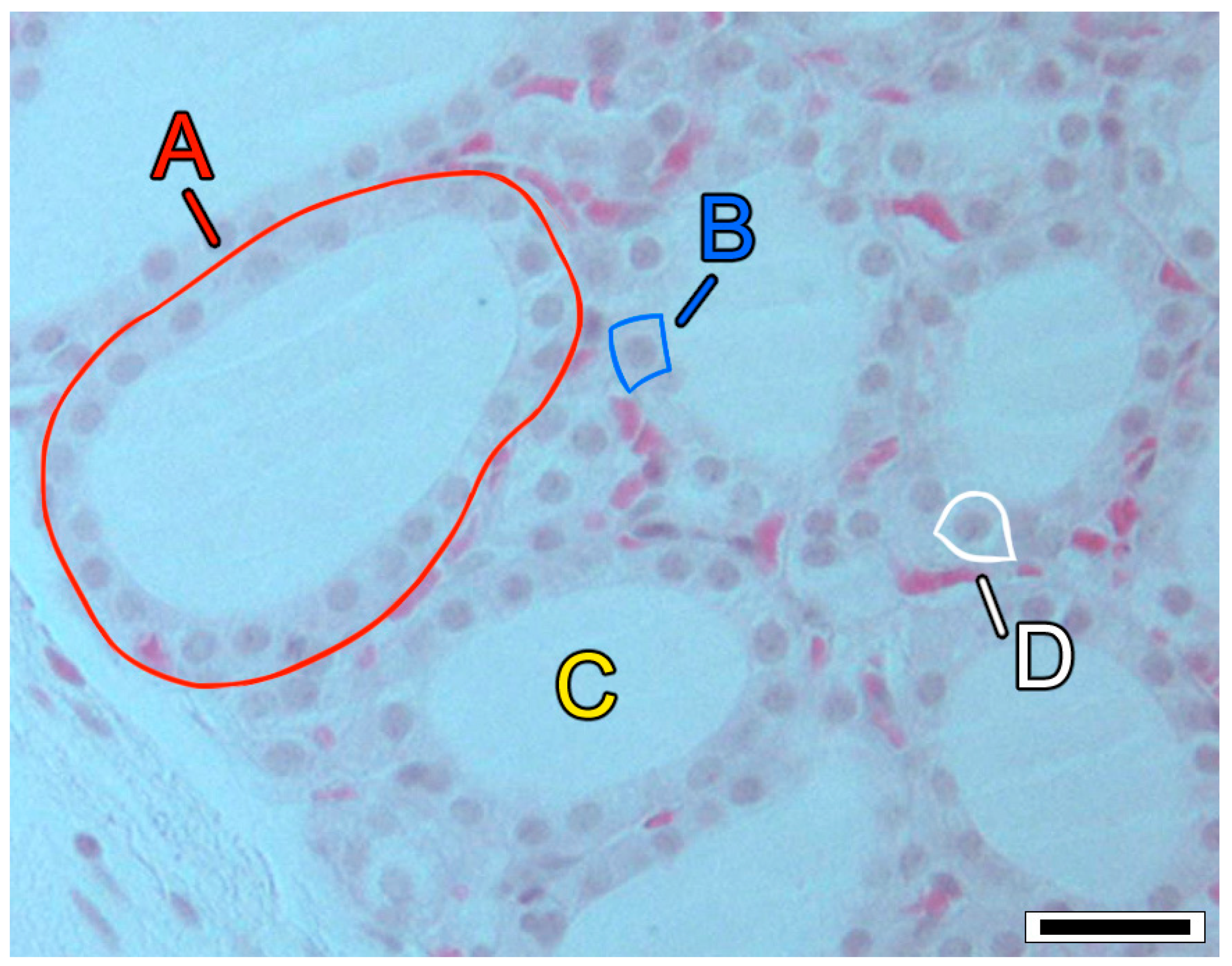

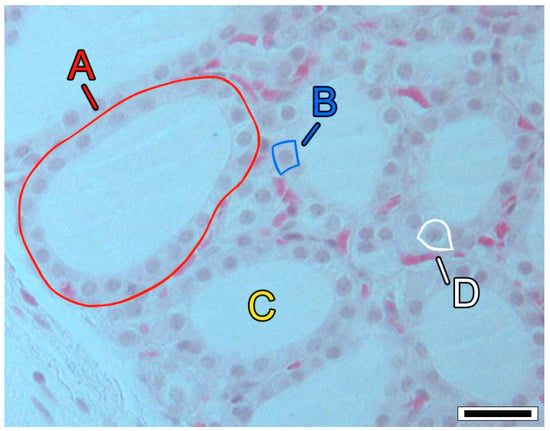

The thyroid is a small, butterfly-shaped endocrine gland located at the front of the neck, responsible for regulating metabolism. This gland synthesizes thyroid hormones (THs)—tetraiodothyronine (thyroxine, T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). Essentially, THs enhance metabolism by affecting the rate at which cells utilize oxygen and nutrients necessary for cellular activities [27,28]. Thyroid hormones oversee a wide array of processes, including the development of the nervous system, respiration, heart rate, body temperature, digestion, and muscle function. Thyrocytes, also known as follicular or epithelial cells, are responsible for producing THs and are arranged in sphere-shaped structures called follicles, which consist of simple cuboidal epithelium that contains colloid in their interior [29]. Within the interstitial tissue between the thyroid follicles, C cells, or parafollicular cells, are present—they produce calcitonin, a hormone that lowers blood calcium levels [30] (Figure 1). The negative feedback mechanism in the hypothalamus–pituitary–thyroid axis (HPT-axis) controls thyroid function based on TH concentrations in the bloodstream. The hypothalamus secretes thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), which is sent to the anterior pituitary, stimulating the production and release of thyrotropin (thyroid-stimulating hormone, TSH). Subsequently, TSH is transported to the thyroid, where it facilitates the biosynthesis and release of TH [29,31].

Figure 1.

Histological section of the thyroid tissue of a wild mouse (Mus musculus L., 1758). Labels: A = follicle; B = thyrocyte (or thyroid follicular cell); C = colloid; D = C cell (or parafollicular cell). Hematoxylin and eosin stain; scale bar = 25 µm; photomicrograph by N. M. P. Coelho.

The thyroid retains high plasticity even in adults, reflecting its ability to adapt to stimuli by changing both its structure and function according to physiological needs. Thyroid structure is closely related to glandular activity levels, making its morphology a good indicator of functional status [32,33,34,35]. Thyroid follicle size and epithelium height are examples of where histological alterations of note can be observed [36]. Around the world, thyroid disorders are the most common endocrine disorders, estimated at around 200 million people having been diagnosed [37]. Estimates suggest that 1 in 10 men and 1 in 8 women have some form of thyroid condition. It is further believed that 50% of thyroid disorders remain undiagnosed, underlining the seriousness of the topic [38]. Hypothyroidism—a thyroid endocrine disorder where THs are produced in insufficient amounts—is thought to affect approximately 5% of world population (≈380 million), with another 5% remaining undiagnosed [39]. This data underlies the need for developing studies that determine the causes of thyroid endocrine disruption so that countermeasures can be implemented.

Endocrine disruption is the process by which natural or man-made chemicals interfere with hormones, frequently by mimicking their structure or blocking their receptors [40]. These exogenous chemicals are called endocrine disruptors (or endocrine-disrupting chemicals, EDCs), causing alterations in or otherwise interfering with the physiological function of endogenous hormones [41]. Agrochemicals are widely distributed environmental EDCs [42,43,44]. “Thyroid disruption” refers to adverse thyroid outcomes resulting from exposures to EDCs, like hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, and cancer [45,46]. Epidemiological studies represent the majority of research linking thyroid disruption with exposure to CF and OF contaminants, with hypothyroidism often being reported in occupationally exposed farm workers [47,48]. A recent study showed that mice chronically exposed to a CF environment had thyroid histomorphology alterations [49]. Such alterations, namely when it comes to lower epithelial cell area and volume, revealed indications of hypothyroidism in the exposed mice. Results underscored the usefulness of thyroid histomorphological biomarkers as early and sensitive indicators of glandular activity, providing information about thyroid disruption.

The purpose of this study is to assess the potential negative impact of OF on the thyroid gland and compare it with the negative impact of CF on this organ, using histological techniques for the analysis of the thyroid of wild mice chronically exposed to these agricultural practices. The topic is especially relevant given the growing demand for agricultural products, and the tendency to regard OF as a better alternative to CF. Therefore, this study aims to answer the following questions: (i) Does chronic exposure to an environment where there are OF practices negatively affect the thyroid? (ii) If so, is such an impact less severe than that caused by CF? The formulated hypothesis was that chronic exposure to OF has a negative but less severe impact on the thyroid than that caused by CF.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Sites

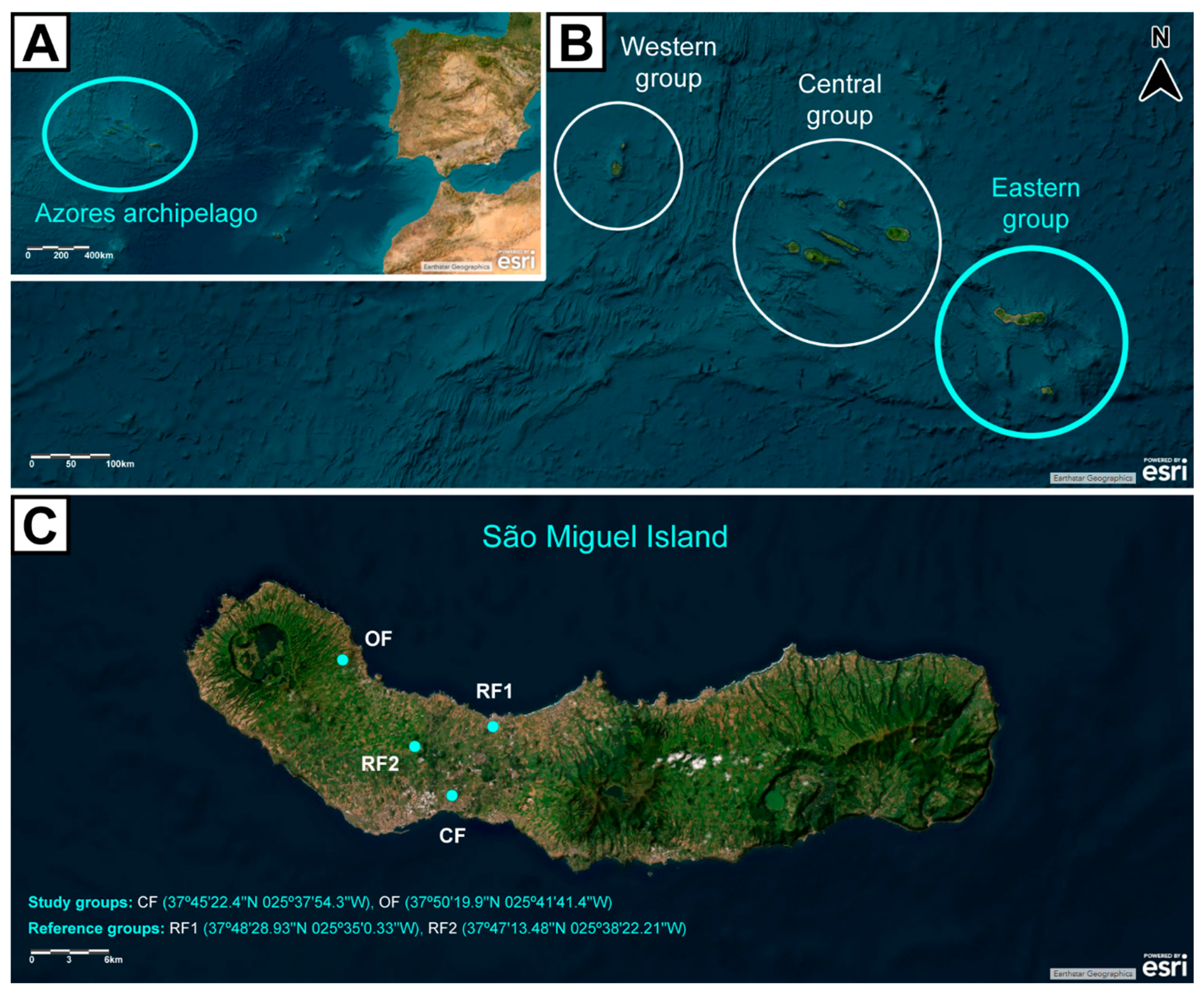

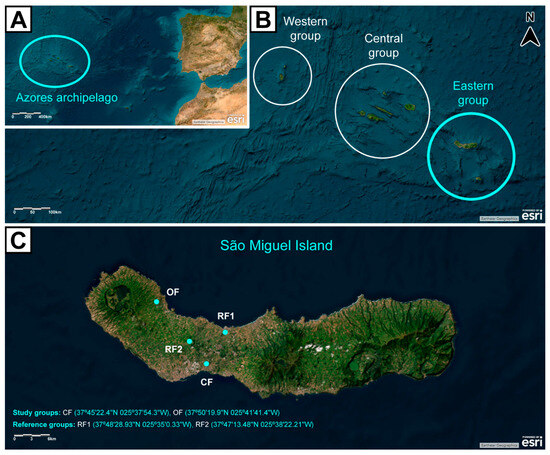

This work was executed on the island of São Miguel, located in the archipelago of the Azores, belonging to Portugal. Study sites were selected based on the presence or absence of agricultural practices—including the nature of those practices. A total of four sites were selected: two agricultural areas (study groups) and two areas without agriculture (reference groups) (Figure 2). The two study groups corresponded to a CF site and an OF site, operated under the respective agricultural system for at least a decade. Concerning the two reference groups, one was a small village (Rabo de Peixe, RF1), while the other corresponded to a pristine area (Pinhal da Paz, RF2); in neither of which agricultural practices had been carried out for at least a decade. All sites are located in the geological complex of Picos Fissural Volcanic System, which provides them with similar bedrock and pedological conditions. This ensures that each site is distinguished mostly on the occurrence and nature of agricultural practices [50,51].

Figure 2.

Map of the Azores archipelago showcasing (A) its location in the Atlantic Ocean, (B) its geographical groups, and (C) São Miguel Island and study sites. Study groups = conventional farming (CF), and organic farming (OF) agricultural areas; Reference groups = small village area (Rabo de Peixe, RF1), and pristine area (Pinhal da Paz, RF2), without agricultural practices. Basemap aerial view backgrounds obtained from ESRI ArcGIS online v2.3: “World Imagery” [basemap], “World Imagery Map”. Last updated on November 2024. https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=10df2279f9684e4a9f6a7f08febac2a9 (most recently consulted on 10 December 2024). Attribution to ESRI and other data providers is present in the figure.

Conventional farming systems are characterized by agricultural practices that frequently utilize agrochemicals, which are governed by European and national regulations. The agrochemicals used in the study area encompass a range of inputs, including both organic and inorganic fertilizers, as well as various pesticides—such as insecticides, herbicides, nematicides, fungicides, molluscicides, and acaricides. Parelho et al. (2014) [50] highlight that agriculture represents a diffuse source of metal pollution in the farming soils of the island of São Miguel. The authors note that the soils under conventional farming practices in this region are especially contaminated with lithium (Li), potassium (K), and molybdenum (Mo), attributed to the intensive and repeated application of inorganic fertilizers and pesticides. On the other hand, OF systems are certified by the European Commission, which prohibits the use of synthetic agrochemicals. Soil amendments are restricted to organic fertilizers, specifically manure and compost. Both farms have been operated under the same system for at least a decade [51]. RF1 is the largest fishing village in the Azores. There are no major agricultural practices within the village, with the exception of some home gardening for a small part of its population. Meanwhile, RF2 is situated within a region with no historical records or evidence of farming activity, encompassing a centennial Japanese cedar [Cryptomeria japonica (Thunb. ex L.f.) D.Don] forest reserve. According to Parelho et al. (2014) [50], the soils from OF and RF2 have trace metal background values significantly lower than those found in the CF site. An exception was identified for vanadium (V) and barium (Ba), both of which are found in greater concentrations in RF2 compared to CF and OF soils. Additional information regarding the characteristics of the study sites is available in Parelho et al. (2016) [51].

2.2. Mice Sampling and Preparation of Histological Slides

Data from animals living in—or otherwise exposed to—contaminated environments is important in research, given that it provides early warnings for environmental hazards and potential human health risks. The assessment of toxic effects on bioindicator species at environmentally relevant concentrations helps in understanding long-term effects of environmental stressors, monitoring contaminant flow through ecosystems and food chains, developing conservation strategies, and protecting public health. Field studies with animal models capture realistic, long-term exposures to complex contaminant mixtures, picturing ecological realism and tapping into conditions impossible to recreate in a laboratory [52,53,54]. Wild mice, scientifically known as Mus musculus L., 1758, meet the criteria for being chosen as bioindicators (i.e., they exhibit high abundance, possess a life expectancy that is sufficiently long to enable the assessment of potential long-term effects [55], and have a relatively small average home range of 145 m2 [56]). Therefore, they were selected as bioindicator species for this study.

In accordance with the methodology described by Coelho et al. (2024) [49], M. musculus mice were captured in each of the selected sites (CF, OF, RF1, and RF2). Following euthanasia using isoflurane (IsoVet® by B. Braun, Voorschoten, The Netherlands), their thyroids underwent the normal histological processing procedures. Both male and female mice were included in this study. Histological slides with several 5 µm thyroid sections of 64 individuals were prepared: 12 from CF, 12 from OF, 27 from RF1, and 13 from RF2. Hematoxylin and eosin stain was applied [57]. A series of histomorphometric and histomorphologic data was collected from the slides with the objective of assessing thyroid status.

Because males and females were not equally distributed between groups (χ2-test, p < 0.05), their data was first treated separately (Supplementary Materials). For both males and females, groups RF1 and RF2 did not differ in the majority of the evaluated parameters (t-test, p > 0.05 for normal data; U-test, p > 0.05 for non-normal data), hence they were merged into a new group, designated RF’ (Supplementary Materials). After assessing differences within groups between males and females, it was found that they did not differ in the majority of the evaluated parameters (t-test, p > 0.05 for normal data; U-test, p > 0.05 for non-normal data), hence statistical analysis was finally performed between groups CF, OF, and RF’ on their respective male and female populations (Supplementary Materials). The inclusion of both males and females within groups ensured balanced samples across the CF and OF groups. In addition, the higher number of individuals in the RF’ group compared to the CF and OF groups increased statistical power, increasing the likelihood of detecting real differences between groups [58]. There were no significant differences (F-test, p > 0.05) in the weight of mice between groups [weight (g): 14.1 ± 0.47 (CF); 13.4 ± 0.40 (OF); 14.6 ± 0.42 (RF’)]. Mice from the CF and OF groups were, on average, significantly (F-test, p > 0.05) younger than those from the RF’ group [age (days): 107 ± 5.3 (CF); 116 ± 11 (OF); 212 ± 11 (RF’)].

The procedures involved in this work were authorized by the Ethics Committee of the University of Azores (REF: 10/2020). The procedures were performed under the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes (ETS 123) recommendations, directive 2010/63EU, and Portuguese legislation (DL 113/2013).

2.3. Histomorphometric Analysis

Following the methodology from Coelho et al. (2024) [49], five thyroid fields, separated by at least 20 µm, were selected for taking photomicrographs, with a total of 20 follicles studied per individual.

Using the Image-Pro Plus v5.0 software, data regarding the (i) number of follicles in a 30,000 µm2 thyroid area, (ii) colloid area and (iii) perimeter, (iv) epithelium thickness, and (v) number of epithelial cell nuclei on a 50 µm transect (Supplementary Materials) was collected. For each parameter, data were recorded as the average per individual. Data regarding the average width of epithelial cells, the average area of epithelial cells, and the average volume of epithelial cells was calculated as described in Coelho et al. (2024) [49].

Epithelium thickness varies with thyroid activity, with cuboidal cells when the gland functions normally and smaller, squamous cells when it is underactive. In light of this, the average epithelium thickness, along with the average epithelial cells’ area and volume, were selected as the primary thyroid function biomarkers [59].

2.4. Histomorphological Analysis

Per field, per individual, five histomorphological parameters (follicular sphericity, epithelium irregularity, degree of exfoliation, degree of inflammation, and degree of colloid vacuolization—the latter based on the presence of vacuoles in the colloid) were studied via the visual qualitative scales defined in Coelho et al. (2024) [49]. The higher the value indicated on the scales, the more significant the disruption to the thyroid. The analyses were performed by two independent observers. The final values were determined by consensus, totaling the following number of observations: 60 for CF, 60 for OF, 135 for RF1, and 65 for RF2. Both the independent analyses and large number of observations served as a way to ensure that the recorded abnormalities were not influenced by histological processing artifacts. Examples of photomicrographs assigned with extreme values can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out in the IBM SPSS Statistics ® v. 28.0.1 (142) software. Statistical significance was considered when p < 0.05.

Morphometric data normality was assessed through Q-Q plots. Differences in the means between groups CF, OF, and RF’ were assessed via One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests [followed by post hoc Tukey’s honest significance (HSD) tests, to assess which groups differed from one another] for normal data, and non-parametric independent samples Kruskal–Wallis tests (followed by pairwise comparisons, to assess which groups differed from one another) for non-normal data.

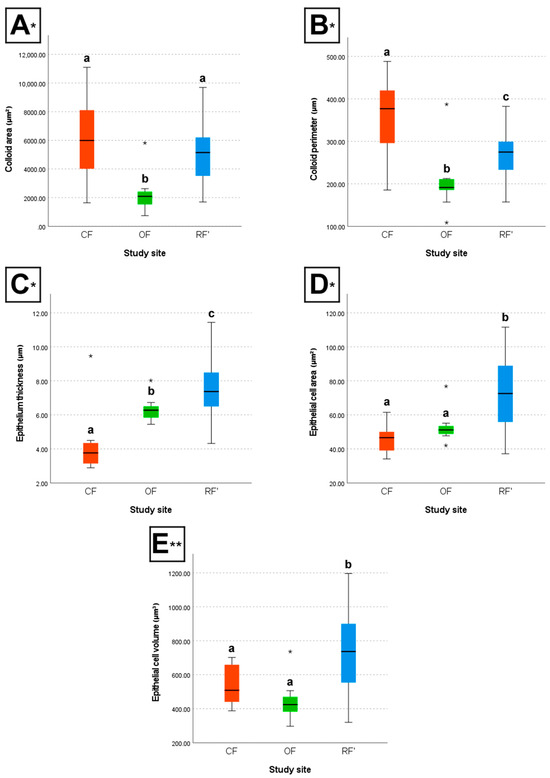

Box plots illustrating colloid area and perimeter, epithelium thickness, and epithelial cell area and volume were made, with the aim of better illustrating differences between their distributions per group. Much like a squamous epithelium, follicles with larger colloid area and perimeter are also indicative of an underactive thyroid. In light of this, the mentioned parameters were chosen for graphical representation due to better representing indications of thyroid disruption [33,59].

For morphological data, non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests were employed to analyze and compare the distributions of values assigned in observations among the groups CF, OF, and RF’. The relative frequency of each category was calculated, per group, to better illustrate differences between their distributions per group.

Data associations were determined via Spearman correlations (in all correlations assessed, at least one parameter had either non-normal data or qualitative data).

3. Results

3.1. Histomorphometric Analysis

The table below displays the descriptive statistics and differences between groups regarding morphometric (quantitative) data (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics detailing the mean values and corresponding standard errors of histomorphometric data from male and female wild mice (Mus musculus L., 1758) sourced from conventional farming (CF), organic farming (OF), and reference (RF’) sites. Pairwise comparisons are shown. * H-test; ** F-test; bold p values mark significant differences (p < 0.05).

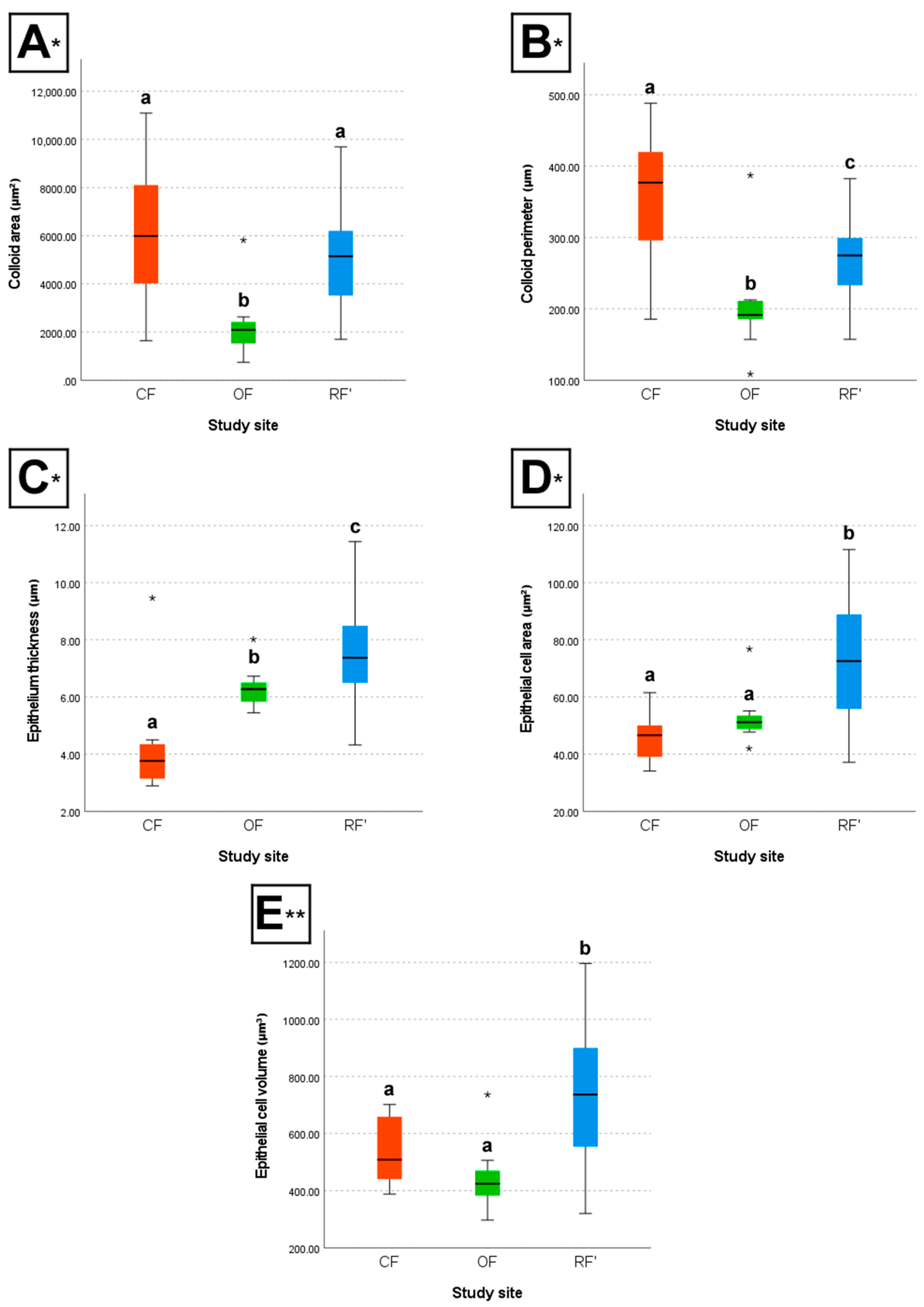

The box plots below illustrate the differences between groups concerning colloid area and perimeter, epithelium thickness, and epithelial cell area and volume (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Box plots of the (A) colloid area, (B) colloid perimeter, (C) epithelium thickness, (D) epithelial cell area, and (E) epithelial cell volume of the male and female wild mice (Mus musculus L., 1758) sourced from conventional farming (CF), organic farming (OF), and reference (RF’) sites. * H-test; ** F-test; different letters (a, b, and c) indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). The line in the middle of each box plot represents the median of the respective group; error bars are shown; an asterisk within the graphs indicates a group outlier.

Between CF and OF, results show that individuals from CF had, on average, significantly larger colloid area (H-test, p < 0.05), larger colloid perimeter (H-test, p < 0.05), lower epithelium thickness (H-test, p < 0.05), a lower number of epithelial cell nuclei per 50 µm (H-test, p < 0.05), larger epithelial cell width (F-test, p < 0.05), and a lower number of follicles in a 30,000 µm2 thyroid area (H-test, p < 0.05), when compared to individuals from OF. However, CF and OF individuals did not differ significantly regarding epithelial cell area (H-test, p > 0.05) and epithelial cell volume (F-test, p > 0.05).

Between CF and RF’, results show that individuals from CF had, on average, significantly larger colloid perimeter (H-test, p < 0.05), lower epithelium thickness (H-test, p < 0.05), a lower number of epithelial cell nuclei per 50 µm (H-test, p < 0.05), larger epithelial cell width (F-test, p < 0.05), lower epithelial cell area (H-test, p < 0.05), lower epithelial cell volume (F-test, p < 0.05), and a lower number of follicles in a 30,000 µm2 thyroid area (H-test, p < 0.05), when compared to individuals from RF’. However, CF and RF’ individuals did not differ significantly regarding colloid area (H-test, p > 0.05).

Finally, between OF and RF’, results show that individuals from OF had, on average, significantly lower colloid area (H-test, p < 0.05), lower colloid perimeter (H-test, p < 0.05), lower epithelium thickness (H-test, p < 0.05), a higher number of epithelial cell nuclei per 50 µm (H-test, p < 0.05), lower epithelial cell width (F-test, p < 0.05), lower epithelial cell area (H-test, p < 0.05), lower epithelial cell volume (F-test, p < 0.05), and a higher number of follicles in a 30,000 µm2 thyroid area (H-test, p < 0.05), when compared to individuals from RF’.

3.2. Histomorphological Analysis

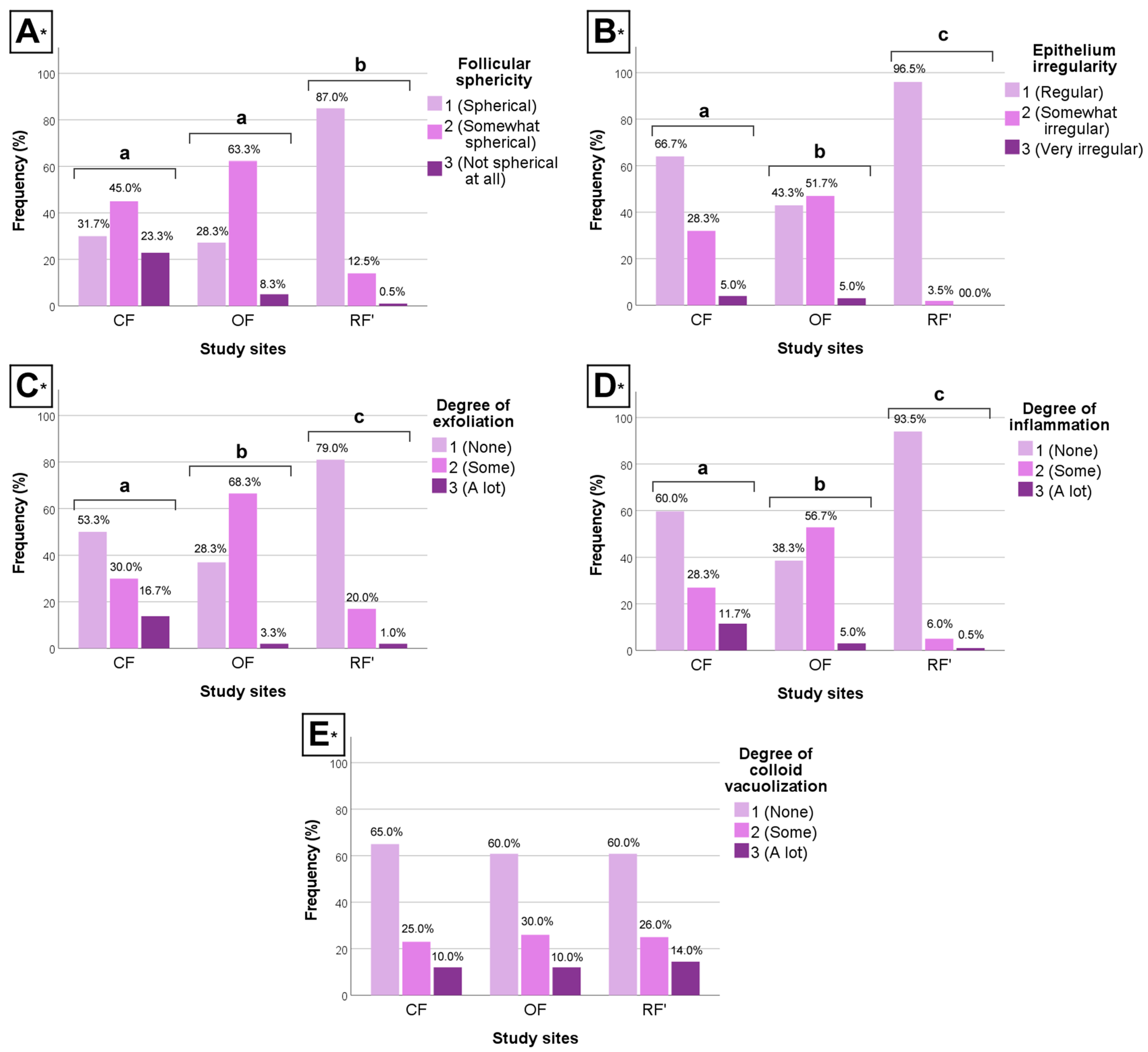

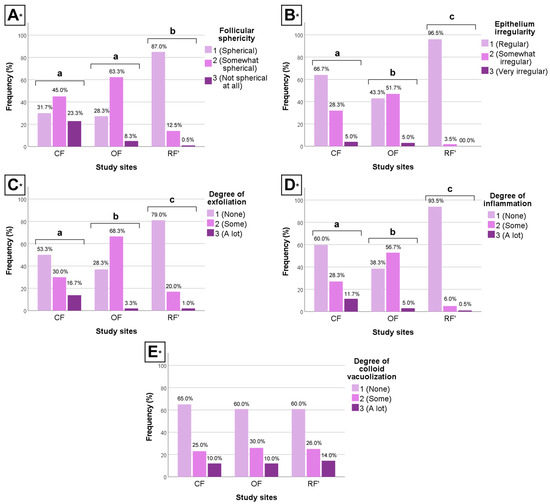

The clustered bar charts below illustrate the differences between groups regarding morphologic (qualitative) data (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Clustered bar charts of the (A) follicular sphericity, (B) epithelium irregularity, (C) degree of exfoliation, (D) degree of inflammation, and (E) degree of colloid vacuolization of the male and female wild mice (Mus musculus L., 1758) sourced from conventional farming (CF), organic farming (OF), and reference (RF’) sites. * H-test; different letters (a, b, and c) indicate significant differences (p < 0.05); relative frequencies per category per group are shown.

Between CF and OF, results show that individuals from CF had significantly more regular epithelium, less exfoliation, and less inflammation (H-test, p < 0.05, all parameters), when compared to individuals from OF. However, CF and OF individuals did not differ significantly regarding follicular sphericity (H-test, p > 0.05).

Between CF and RF’, results show that individuals from CF had significantly less spherical follicles, more irregular epithelium, more exfoliation, and more inflammation (H-test, p < 0.05, all parameters), when compared to individuals from RF’.

Finally, between OF and RF’, results show that individuals from OF had significantly less spherical follicles, more irregular epithelium, more exfoliation, and more inflammation (H-test, p < 0.05, all parameters), when compared to individuals from RF’.

3.3. Data Correlations

Regarding morphometric data, results showed a significant (p < 0.05) positive association between (i) weight and colloid area [rs(64) = 0.274, p = 0.028]; (ii) weight and colloid perimeter [rs(64) = 0.257, p = 0.040]; (iii) age and epithelium thickness [rs(64) = 0.429, p < 0.001]; (iv) age and epithelial cell area [rs(64) = 0.480, p < 0.001]; and (v) age and epithelial cell volume [rs(64) = 0.389, p = 0.001]. On the other hand, there was a significant (p < 0.05) negative association between weight and number of follicles in a 30,000 µm2 thyroid area [rs(64) = −0.312, p = 0.012].

4. Discussion

Numerous studies have examined the effects of environmental endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) on thyroid outcomes [46,60,61,62,63]. In this context, several studies have utilized morphological parameters to evaluate the status of thyroid function, focusing on exposures to substances that induce thyroid endocrine disruption [64,65,66,67]. In Coelho et al. (2024) [49], links were identified between prolonged exposure to environments where there are CF practices and thyroid disruption, notably the emergence of histological signs resembling hypothyroidism in wild mice that were exposed. The methodology followed in this work corroborated those results, while also revealing the same—albeit less strikingly, in certain parameters—for chronic exposure to an environment where there are OF practices. The obtained results are in accordance with those of in vivo studies linking hypothyroidism with exposure to CF contaminants, with emphasis on pesticides [68,69,70,71]. Results also support the findings of other studies indicating a link between hypothyroidism in humans and exposure to CF contaminants [72,73,74,75,76] and OF contaminants [44].

In research, it is important that study populations are well balanced, particularly with respect to the number of subjects per group, age, and sex. This ensures representative samples which support the validity and generalization of results towards larger, more diverse populations, while minimizing the risk of bias [77]. Confounding factors potentially influencing the results of this work were the weight and age of the mice, which should be taken into account when interpreting results [78]. As seen by data correlations, weight could have influenced colloid area, colloid perimeter (heavier mice had larger colloid area and perimeter), and number of follicles in a 30,000 µm2 thyroid area (heavier mice had a lower number of follicles in a 30,000 µm2 thyroid area). Even so, the influence of weight on results was negligible, due to the lack of statistically significant differences in weight between groups. On the other hand, age may have influenced epithelium thickness, epithelial cell area, and epithelial cell volume (younger mice presented lower epithelium thickness, and lower epithelial cell area and volume). This is an important aspect, given that both CF and OF mice were significantly younger than RF’ mice.

Collectively, indications of a higher degree of thyroid disruption in CF, followed by OF, in comparison to RF’ were found for both males and females—especially with regard to lower epithelium thickness, lower epithelial cell area and volume, and a higher degree of thyroid disruption registered in the majority of the evaluated histomorphologic parameters. A noteworthy observation was that indications of thyroid disruption in OF mice were of an intermediate level between CF and RF’ mice. In the study of Parelho et al. (2016) [51], CF mice bioaccumulated higher lead (Pb) hepatic loads, while OF mice bioaccumulated higher cadmium (Cd) hepatic loads—both of which are well-known PTEs—which may help explain some of the results. Still, there are important limitations to be considered when interpreting results, particularly when it comes to the lack of data on TH and TSH levels, and the concentration of EDCs in mouse tissues. The absence of these measurements makes it unclear whether the observed alterations are clinically adverse, leading to the indirect designation of a hypothyroid status in exposed mice. Another relevant aspect is that, although data on soil contaminants within the study sites is available in Parelho et al. (2014, 2016) [50,51], it may not reflect present-day concentrations. Ultimately, this means that the observed thyroid effects can only be attributed to CF and OF environments rather than to defined agents or exposure levels. In light of this, future studies in the scope should include measurements of TH levels and/or EDCs in bioindicators, along with contemporaneous data on contaminants present in the study sites to better justify observed effects.

A healthy thyroid is crucial for young individuals, given that THs contribute to the growth, development, and proper functioning of every organ system in the body [79]. These hormones play a critical role in brain development, to the point where even minor TH deficiencies in youth can cause irreversible brain damage [80,81]. However, thyroid function is known to decline with age, marked by a reduction in TH secretion, and a decline in T3 levels due to decreased peripheral conversion of T4. The HPT-axis also loses response plasticity to shifts in TH production, which can be seen, for instance, in a less pronounced TSH response to TH deficiency [82,83]. Although the lack of age-matched sampling or age-adjusted models in this study may weaken causal interpretation, the fact that the thyroids of exposed mice presented more indications of disruption, even while CF and OF mice were significantly younger than non-exposed RF’ mice (practically half their age), is of concern. Although it was anticipated that the thyroids of younger mice would exhibit a significantly more active state (i.e., characterized by smaller follicles, thicker epithelium, and epithelial cells with increased area and volume), they instead displayed reduced epithelium thickness, diminished epithelial cell area, and decreased epithelial cell volume, all of which suggest a loss of function (hypothyroidism) [33,34]. The existence of notable differences between groups, irrespective of age, underscores the severity of the effects of chronic exposure to CF and OF contaminants on thyroid function. Furthermore, it is conceivable that the variation in data among groups could have been more pronounced had the ages of the mice not varied significantly, accounting for a longer duration of exposure to the farming environments. Increased colloid area and perimeter are also often associated with hypothyroidism [33]; nevertheless, in this work, differences between groups were mostly not significant for these parameters. Therefore, epithelium thickness, along with epithelial cell area and volume, might be a better alternative to assess thyroid disruption than colloid area and perimeter alone. These results further emphasize the significance of effect biomarkers—including epithelial thickness, as well as cell area and volume—in research evaluating chronic exposure to contaminants. Additionally, these biomarkers may be particularly pertinent for organs that play crucial roles in metabolism over an extended lifespan.

In addition to decreasing the ability of the thyroid to produce hormones—as seen through a thinner epithelium, and epithelial cells of smaller area and volume—chronic exposure to CF and OF seemed to alter the histomorphology of the gland. Lower follicular sphericity, epithelium of irregular delimitation, high degree of exfoliation, and high degree of inflammation were observed in the thyroids of OF-exposed mice, though less pronouncedly than in CF mice. No differences were found between groups in terms of degree of vacuolization (when in abundance, colloid vacuoles tend to be a sign of thyroid epithelial cell hyperactivity, which is in line with other studies [66,84,85]).

Decreased follicular sphericity, epithelium of irregular delimitation, and higher degree of exfoliation are alterations that reflect thyroid function status. Because of this, these aspects are the ones most likely tied with exposure to CF and OF environments. On the one hand, decreased follicular sphericity and epithelium of irregular delimitation are commonly associated with injuries on the thyroid [86,87]. In turn, exfoliation, while being a part of normal thyroid function, is tied to epithelial cell degeneration, which results in shedding into the colloid—where apoptosis (cell death) occurs [87,88]. Considering this, results suggest that thyroid disruption arising in CF- and OF-exposed mice not only involves indications of loss of function, but also observable alterations to tissue histomorphology. On the other hand, evidence of a higher abundance of lymphocytes in the thyroid of CF- and OF-exposed mice suggests inflammation that may be related to agrochemical residues and their endocrine-disrupting potential. Agrochemicals have been noted to cause unusual inflammatory reactions, as they can disrupt the normal physiology and metabolism of immune system cells [89,90]. In Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, the immune system actively attacks the thyroid, destroying thyroid cells via cell- and antibody-mediated processes, which can lead to hypothyroidism or underactive thyroid [91]. The causes for Hashimoto’s thyroiditis are still unclear; however, it is plausible that environmental factors, like contaminant exposure, may contribute to its onset [92,93].

It has been shown that EDCs can act at any level of the HPT-axis communication, including by interfering with tissue-specific factors such as iodothyronine deiodinase (DIO) enzymes. Some mechanisms of EDCs’ interference with thyroid metabolism and signaling pathways are (i) mimicking TH structure, (ii) binding to TH receptors, (iii) binding to TH transport proteins, (iv) inhibiting or stimulating DIO activity, (v) inhibiting or stimulating thyroperoxidase (TPO) activity, and (vi) inhibiting iodide (I−) transport into thyrocytes [94,95,96]. The heavy metals (also designated potentially toxic elements, PTEs) present in the composition of agrochemicals—with special emphasis on pesticides—often mimic the chemical structure of TH [97,98,99,100]. Because inorganic fertilizers and several pesticides were used in the CF study site, the observed histological effects on CF-exposed mice were expected and can likely be attributed to the intensive application of these contaminants. In contrast, relatively fewer studies have addressed the impact of OF contaminants on health [26,44,101,102,103]. In the study of Zhuang et al. (2024) [26], eight types of major ARGs and 10 mobile genetic elements (MGEs) were detected in the gut microbiome of mice exposed to a diet consisting of organic foods, including tetracycline, multidrug, sulfonamide, aminoglycoside, beta-lactamase, chloramphenicol, MLSB, and vancomycin resistance genes. It was also found that the abundance and diversity of ARGs, MGEs, and potential antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) in the gut increased with time after organic food consumption. ARGs are not known to directly disrupt the thyroid; however, environmental antibiotic-related contaminants can cause thyroid disruption via TH synthesis inhibition or by causing chemical thyroiditis. It has been documented that long-term exposures to certain antibiotics—like tetracyclines—present in contaminated food and water can cause thyroid disruption [104]. The immune system, which is dysregulated in thyroid autoimmune disorders, can also be influenced by the microbiome [105]. The works of Kongtip et al. (2019) [44] and Nankongnab et al. (2020a) [102] were the only ones to directly study thyroid effects on OF farmers. Their works involved the same population of CF and OF farmers in Thailand. In both studies, the authors found that the TSH, free T3 (FT3), T3, and T4 levels were significantly higher in CF farmers than in OF farmers. In both groups, several individuals suffered from hypothyroidism, though there was a higher proportion of hypothyroid individuals in the OF group. The authors suggested the higher number of females in the OF group—some of which were nearing or in postmenopausal age—as a likely explanation for a higher proportion of hypothyroid individuals. Another relevant factor was that many individuals in the OF group had handled agrochemicals, particularly pesticides, in the past. The studies lacked a population non-exposed to farming environments to serve as a reference group, which makes it difficult to establish the true extent of the impact of OF on the thyroid. Still, their results align with those of the present work in that thyroid effects were overall more pronounced on the CF-exposed group than the OF-exposed group.

The results obtained in this work underline the risks of chronic exposure to both CF and OF environments, which supports the first hypothesis. The thyroids of exposed mice showed several histological signs of disruption (particularly indicating hypothyroidism), when compared to the RF’ group, though less pronouncedly in the OF group. While OF might be a better alternative to CF, it is not completely free of health hazards, mainly because OF products can be indirectly contaminated by the agrochemicals used in CF practices. Considering this, organic certification must guarantee total exemption of agrochemical contamination in OF products. Overall, seeing as exposure to an OF environment seemed to have a less severe impact on the thyroid, the benefit of transitioning from CF systems towards OF systems is supported. Petit et al. (2024) [106] alert us to the fact that thyroid disorders among farmers “likely arise from the combined effects of various causal agents and triggering factors (agricultural exposome)”. In light of this, it is important to continue research into what exactly causes thyroid disruption in both CF and, especially, OF farming practices, so that countermeasures can be taken. Filling in these knowledge gaps is of utmost importance for occupationally exposed farmers, as well as for the general population through food consumption. Efforts made towards tracking pesticide residues in food products have been substantial in the European Union (EU) [107,108,109]. Unfortunately, the same still cannot be said about other regions of the world.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate that chronic exposure to an OF environment—albeit less pronouncedly than in a CF environment—still leads to thyroid disruption. Although there are some limitations to be considered—such as the lack of data on TH levels —this is evidenced by clear histological alterations observed in the thyroid tissue of exposed wild mice, namely (i) decreased epithelium thickness, (ii) lower epithelial cell area and (iii) volume, (iv) lower follicular sphericity, (v) epithelium with irregular delimitation, (vi) greater exfoliation towards the colloid, and (vii) increased inflammation of thyroid tissue. Lower epithelium thickness, along with lower epithelial cell area and volume, are indications commonly associated with hypothyroidism.

Because the OF environment seemed to have a less severe impact on the thyroid than the CF environment, the transition from the globally predominant CF systems to OF alternatives is supported. Still, knowledge gaps remain regarding the general impact of OF on human health. More research is needed about what exactly causes thyroid disruption in both CF and, especially, OF farms, so that preventive countermeasures can be implemented. The topic is of utmost importance, given that it is not only farmers who are exposed to such hazards through their occupation, but also the general population, who are exposed through food consumption.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/environments13020066/s1, Figure S1. Distribution of the male and female wild mice (Mus musculus L., 1758) sourced from conventional farming (CF), organic farming (OF), and reference (RF’) sites; Figure S2. Box plots of the (A) colloid area, (B) colloid perimeter, (C) epithelium thickness, (D) epithelial cell area, and (E) epithelial cell volume of the male (M) wild mice (Mus musculus L., 1758) sourced from conventional farming (CF), organic farming (OF), and reference (RF’) sites; Figure S3. Box plots of the (A) colloid area, (B) colloid perimeter, (C) epithelium thickness, (D) epithelial cell area, and (E) epithelial cell volume of the female (F) wild mice (Mus musculus L., 1758) sourced from conventional farming (CF), organic farming (OF), and reference (RF’) sites; Figure S4. Clustered bar charts of the (A) follicular sphericity, (B) epithelium irregularity, (C) degree of exfoliation, (D) degree of inflammation, and (E) degree of colloid vacuolization of the male (M) wild mice (Mus musculus L., 1758) sourced from conventional farming (CF), organic farming (OF), and reference (RF’) sites; Figure S5. Clustered bar charts of the (A) follicular sphericity, (B) epithelium irregularity, (C) degree of exfoliation, (D) degree of inflammation, and (E) degree of colloid vacuolization of the female (F) wild mice (Mus musculus L., 1758) sourced from conventional farming (CF), organic farming (OF), and reference (RF’) sites; Figure S6. Photomicrographs from thyroid histological sections of wild mice (Mus musculus L., 1758) detailing histomorphometric analysis; Figure S7. Photomicrographs from thyroid histological sections of wild mice (Mus musculus L., 1758) detailing histomorphological analysis; Table S1. Distribution of males and females from conventional farming (CF), organic farming (OF), and reference (RF1, RF2) sites; Table S2. Distribution of males and females from conventional farming (CF), organic farming (OF), and reference (RF’) sites; Table S3. Descriptive statistics detailing the mean values and corresponding standard errors of histomorphometric data from male and female wild mice (Mus musculus L., 1758) sourced from conventional farming (CF), organic farming (OF), and reference (RF’) sites; Table S4. Descriptive statistics detailing the registered observations of histomorphologic data from male and female wild mice (Mus musculus L., 1758) sourced from conventional farming (CF), organic farming (OF), and reference (RF’) sites.

Author Contributions

N.M.P.C.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Illustrating graphical abstract; R.C.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—Review and editing; P.G.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing—Review and editing; F.B.: Conceptualization, Writing—Review and editing; A.S.R.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing—Review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by cE3c (DOI 10.54499/UID/00329/2025) and IVAR (DOI 10.54499/UID/PRR/00643/2025) projects from FCT national funds.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The experimental procedures involved in this work were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Azores (REF: 10/2020). The procedures were performed under the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes (ETS 123) recommendations, directive 2010/63EU, and Portuguese legislation (DL 113/2013).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Paulo Melo for the support in fieldwork. The authors declare that there were no generative AI and AI-associated technologies used in the writing process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

ARB, Antibiotic-resistant bacteria; ARGs, Antibiotic resistance genes; CF, Conventional farming; DIO, Iodothyronine deiodinases; EDCs, Endocrine-disrupting chemicals; EU, European Union; FT3, Free triiodothyronine; GMOs, Genetically modified organisms; HPT-axis, Hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis; I, Iodine; I−, Iodide; MGEs, Mobile genetic elements; OF, Organic farming; PTEs, Potentially toxic elements; RF1, Reference group 1; RF2, Reference group 2; RF’, New reference group (merging of RF1 and RF2 groups); T3, Triiodothyronine; T4, Thyroxine, Tetraiodothyronine; TH, Thyroid hormones; TPO, Thyroperoxidase; TRH, Thyrotropin-releasing hormone; TSH, Thyroid-stimulating hormone.

References

- Fanzo, J. The role of farming and rural development as central to our diets. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 193, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana, C.M.; Freire, D.; Abrantes, P.; Rocha, J.; Pereira, P. Agricultural land systems importance for supporting food security and sustainable development goals: A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, R.; Choudhary, D.; Bali, S.; Bandral, S.S.; Singh, V.; Ahmad, M.A.; Rani, N.; Singh, T.G.; Chandrasekaran, B. Pesticides: An alarming detrimental to health and environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 170113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.; Tian, X.; Lai, W.; Xu, S. Agricultural production and air pollution: An investigation on crop straw fires. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarbad, H. Conventional vs. organic agriculture–Which one promotes better yields and microbial resilience in rapidly changing climates? Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 903500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vašková, H.; Saska, P. Comparison of organic and conventional agriculture in the Czech Republic: A systematic review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitán-Cremaschi, D.; Klerkx, L.; Duncan, J.; Trienekens, J.H.; Huenchuleo, C.; Dogliotti, S.; Contesse, M.E.; Rossing, W.A.H. Characterizing diversity of food systems in view of sustainability transitions. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 39, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowder, D.W.; Reganold, J.P. Financial competitiveness of organic agriculture on a global scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 7611–7616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seufert, V.; Ramankutty, N.; Foley, J.A. Comparing the yields of organic and conventional agriculture. Nature 2012, 485, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigar, V.; Myers, S.; Oliver, C.; Arellano, J.; Robinson, S.; Leifert, C. A systematic review of organic versus conventional food consumption: Is there a measurable benefit on human health? Nutrients 2019, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaise de Oliveira Faoro, D.; Artuzo, F.D.; Rossi Borges, J.A.; Foguesatto, C.R.; Dewes, H.; Talamini, E. Are organics more nutritious than conventional foods? A comprehensive systematic review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milner, G.R.; Boldsen, J.L. Population trends and the transition to agriculture: Global processes as seen from North America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2209478119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadighara, P.; Mahmudiono, T.; Marufi, N.; Yazdanfar, N.; Fakhri, Y.; Rikabadi, A.K.; Khaneghah, A.M. Residues of carcinogenic pesticides in food: A systematic review. Rev. Environ. Health 2023, 39, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khode, D.; Hepat, A.; Mudey, A.; Joshi, A. Health-related challenges and programs among agriculture workers: A narrative review. Cureus 2024, 16, e57222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbois, K.-P.; Schmidt, J.E. Reframing the debate surrounding the yield gap between organic and conventional farming. Agronomy 2019, 9, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondrasek, G.; Horvatinec, J.; Kovačić, M.B.; Reljić, M.; Vinceković, M.; Rathod, S.; Bandumula, N.; Dharavath, R.; Rashid, M.I.; Panfilova, O.; et al. Land resources in organic agriculture: Trends and challenges in the twenty-first century from global to Croatian contexts. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strenner, M.; Chmelíková, L.; Hülsbergen, K.-J. Compost fertilization in organic agriculture—A comparison of the impact on corn plants using field spectroscopy. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panday, D.; Bhusal, N.; Das, S.; Ghalehgolabbehbahani, A. Rooted in nature: The rise, challenges, and potential of organic farming and fertilizers in agroecosystems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Qiao, Y.; Wu, W.; Smith, P.; Scott, S. Environmental impacts and production performances of organic agriculture in China: A monetary valuation. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 188, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampieri, F.; Mazzoni, L.; Cianciosi, D.; Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Regolo, L.; Sánchez-González, C.; Capocasa, F.; Xiao, J.; Mezzetti, B.; Battino, M. Organic vs conventional plant-based foods: A review. Food Chem. 2022, 383, 132352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knuth, D.; Gai, L.; Silva, V.; Harkes, P.; Hofman, J.; Šudoma, M.; Bílková, Z.; Alaoui, A.; Mandrioli, D.; Pasković, I.; et al. Pesticide residues in organic and conventional agricultural soils across Europe: Measured and predicted concentrations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 6744–6752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarević-Pašti, T.; Milanković, V.; Tasić, T.; Petrović, S.; Leskovac, A. With or without you?—A critical review on pesticides in food. Foods 2025, 14, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parelho, C.; Rodrigues, A.; Bernardo, F.; Barreto, M.C.; Cunha, L.; Poeta, P.; Garcia, P. Biological endpoints in earthworms (Amynthas gracilis) as tools for the ecotoxicity assessment of soils from livestock production systems. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 95, 984–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.; Peixoto, F.; Igrejas, G.; Parelho, C.; Garcia, P.; Carvalho, I.; Pereira, J.; Rodrigues, A.; Poeta, P. First report on vanA-Enterococcus faecalis recovered from soils subjected to long-term livestock agricultural practices in Azores archipelago. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2018, 12, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassitta, R.; Nottensteiner, A.; Bauer, J.; Straubinger, R.K.; Hölzel, C.S. Spread of antimicrobial resistance genes via pig manure from organic and conventional farms in the presence or absence of antibiotic use. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 2457–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Fan, H.; Li, X.; Dong, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhao, B.; Wu, S. Transfer and accumulation of antibiotic resistance genes and bacterial pathogens in the mice gut due to consumption of organic foods. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 169842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, S.; Salgado Nunez Del Prado, S.; Celi, F.S. Thyroid hormone action and energy expenditure. J. Endocr. Soc. 2019, 3, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivertsson, E.; Friederich-Persson, M.; Persson, P.; Nangaku, M.; Hansell, P.; Palm, F. Thyroid hormone increases oxygen metabolism causing intrarenal tissue hypoxia; a pathway to kidney disease. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiga-Carvalho, T.M.; Chiamolera, M.I.; Pazos-Moura, C.C.; Wondisford, F.E. Hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis. Compr. Physiol. 2016, 6, 1387–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, G.J.; Grubbs, E.G.; Hofmann, M.C. Thyroid c-cell biology and oncogenic transformation. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2015, 204, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelen, A.; Kwakkel, J.; Fliers, E. Thyroid hormone receptors in health and disease. Minerva Endocrinol. 2012, 37, 291–304. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Montiel, M.D.; Suster, S. The spectrum of histologic changes in thyroid hyperplasia: A clinicopathologic study of 300 cases. Human Pathol. 2008, 39, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Yi, S.; Kang, Y.E.; Kim, H.W.; Joung, K.H.; Sul, H.J.; Kim, K.S.; Shong, M. Morphological and functional changes in the thyroid follicles of the aged murine and humans. J. Pathol. Transl. Med. 2016, 50, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, M.L.; Chernock, R.D.; Mansour, M. Environmental factors and anatomic pathology of the thyroid gland: Review of literature. Diagn. Histopathol. 2020, 26, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candanedo-Gonzalez, F.; Rios-Valencia, J.; Noemi Pacheco-Garcilazo, D.; Valenzuela-Gonzalez, W.; Gamboa-Dominguez, A. Morphology Aspects of Hypothyroidism; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallgren, S.; Darnerud, P.O. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and chlorinated paraffins (CPs) in rats–Testing interactions and mechanisms for thyroid hormone effects. Toxicology 2002, 177, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Sun, W.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H. Global scientific trends on thyroid disease in early 21st century: A bibliometric and visualized analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 14, 1306232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, A.; Chaker, L.; Mattace-Raso, F.U.S.; Terzikhan, N.; Kavousi, M.; Ikram, M.A.; Peeters, R.P.; Franco, O.H. Thyroid function and life expectancy with and without noncommunicable diseases: A population-based study. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiovato, L.; Magri, F.; Carlé, A. Hypothyroidism in context: Where we’ve been and where we’re going. Adv. Ther. 2019, 36, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIEHS (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences). Endocrine Disruptors. 2024. Available online: https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/endocrine (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Ahn, C.; Jeung, E.B. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and disease endpoints. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinlay, R.; Plant, J.A.; Bell, J.N.; Voulvoulis, N. Endocrine disrupting pesticides: Implications for risk assessment. Environ. Int. 2008, 34, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, É.; Freire, C. Exposure to non-persistent pesticides and thyroid function: A systematic review of epidemiological evidence. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2016, 219, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongtip, P.; Nankongnab, N.; Kallayanatham, N.; Pundee, R.; Choochouy, N.; Yimsabai, J.; Woskie, S. Thyroid hormones in conventional and organic farmers in Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Xu, J.; Zheng, M.; Pan, K.; Yang, L.; Ma, L.; Wang, C.; Yu, J. Thyroid dysfunction caused by exposure to environmental endocrine disruptors and the underlying mechanism: A review. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2024, 391, 110909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, N.M.P.; Bernardo, F.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Garcia, P. Volcanic environments and thyroid disruption—A review focused on As, Hg, and Co. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 993, 180018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldner, W.S.; Sandler, D.P.; Yu, F.; Hoppin, J.A.; Kamel, F.; Levan, T.D. Pesticide use and thyroid disease among women in the Agricultural Health Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 171, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccoli, C.; Cremonese, C.; Koifman, R.J.; Koifman, S.; Freire, C. Pesticide exposure and thyroid function in an agricultural population in Brazil. Environ. Res. 2016, 151, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, N.; Camarinho, R.; Garcia, P.; Rodrigues, A.S. Histological evidence of hypothyroidism in mice chronically exposed to conventional farming. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 106, 104387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parelho, C.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Cruz, J.V.; Garcia, P. Linking trace metals and agricultural land use in volcanic soils--A multivariate approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 496, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parelho, C.; Bernardo, F.; Camarinho, R.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Garcia, P. Testicular damage and farming environments—An integrative ecotoxicological link. Chemosphere 2016, 155, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imholt, C.; Abdulla, T.; Stevens, A.; Edwards, P.; Jacob, J.; Woods, D.; Rogers, E.; Aarons, L.; Segelcke, D. Establishment and validation of microsampling techniques in wild rodents for ecotoxicological research. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2018, 38, 1244–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudeta, K.; Kumar, V.; Bhagat, A.; Julka, J.M.; Bhat, S.A.; Ameen, F.; Qadri, H.; Singh, S.; Amarowicz, R. Ecological adaptation of earthworms for coping with plant polyphenols, heavy metals, and microplastics in the soil: A review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Jiang, F.; Ma, J.; Alghamdi, M.A.; Zhu, Y.; Yong, J.W.H. Intersecting planetary health: Exploring the impacts of environmental stressors on wildlife and human health. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 283, 116848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcheselli, M.; Sala, L.; Mauri, M. Bioaccumulation of PGEs and other traffic-related metals in populations of the small mammal Apodemus sylvaticus. Chemosphere 2010, 80, 1247–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidicker, W.Z. Ecological observations on a feral house mouse population declining to extinction. Ecol. Monogr. 1966, 36, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martoja, R.; Martoja-Pierson, M.; Grumbles, L.C.; Moncanut, M.E.; Coll, M.D. Técnicas de Histología Animal [Animal Histology Techniques], 1st ed.; Toray-Masson: Barcelona, Spain, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, C. Sample size and its importance in research. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 42, 102–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Felice, M.; Di Lauro, R. Chapter 72—Anatomy and development of the thyroid. In Endocrinology, 6th ed.; Jameson, J.L., De Groot, L.J., Eds.; W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010; pp. 1342–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.M.; Fallahi, P.; Antonelli, A.; Benvenga, S. Environmental issues in thyroid diseases. Front. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority); Crivellente, F.; Hart, A.; Hernandez-Jerez, A.F.; Hougaard Bennekou, S.; Pedersen, R.; Terron, A.; Wolterink, G.; Mohimont, L. Establishment of cumulative assessment groups of pesticides for their effects on the thyroid. EFSA J. 2019, 17, e05801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, F.; Li, Y.; Ru, H.; Wu, L.; Xiao, Z.; Ni, Z.; Chen, D.; Zhong, L. Thyroid disruption and developmental toxicity caused by triphenyltin (TPT) in zebrafish embryos/larvae. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2020, 394, 114957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, N.; Örün, I. Effects of pesticide NeemAzal-T/S on thyroid, stress hormone and some cytokines levels in freshwater common carp, Cyprinus carpio L. Toxin Rev. 2021, 41, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzler, J.G.; Koutrakis, E.; Siebert, U.; Thomé, J.P.; Das, K. Effects of persistent organic pollutants on the thyroid function of the European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) from the Aegean sea, is it an endocrine disruption? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2008, 56, 1755–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- El-Mehi, A.E.; Amin, S.A. Effect of lead acetate on the thyroid gland of adult male albino rats and the possible protective role of zinc supplementation: A biochemical, histological and morphometric study. Am. J. Sci. 2012, 8, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, M.N.; Santos-Silva, A.P.; Rodrigues-Pereira, P.; Paiva-Melo, F.D.; de Lima Junior, N.C.; Teixeira, M.P.; Soares, P.; Dias, G.R.M.; Graceli, J.B.; de Carvalho, D.P.; et al. The environmental contaminant tributyltin leads to abnormalities in different levels of the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis in female rats. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 241, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, H.; Weiss, V.; Loberg, M.; Lee, E. PFAS-mediated disruptions on thyroid histology. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2024, 162, S94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Song, X.; Yuan, W.; Wen, W.; Wu, X.; Li, J.; Chen, X. Effects of cypermethrin and methyl parathion mixtures on hormone levels and immune functions in Wistar rats. Arch. Toxicol. 2006, 80, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallem, L.; Boulakoud, M.S.; Franck, M. Hypothyroidism after medium exposure to the fungicide maneb in the rabbit Cuniculus lepus. Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci. 2006, 71, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Stoker, T.; Kaydos, E.; Jeffay, S.; Cooper, R. Effect of 2,4-D exposure on pubertal development and thyroid function in the male Wistar rat. Biol. Reprod. 2007, 77, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanu, A.P. Disrupting action of cypermethrin on thyroid and cortisol hormones in the serum of Cyprinus carpio. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2016, 4, 340–341. [Google Scholar]

- Goldner, W.S.; Sandler, D.P.; Yu, F.; Shostrom, V.; Hoppin, J.A.; Kamel, F.; LeVan, T.D. Hypothyroidism and pesticide use among male private pesticide applicators in the Agricultural Health Study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2013, 55, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farokhi, F.; Taravati, A. Pesticide exposure and thyroid function in adult male sprayers. Int. J. Med. Investig. 2014, 3, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, S.; Parks, C.G.; Goldner, W.S.; Kamel, F.; Umbach, D.M.; Ward, M.H.; Lerro, C.C.; Koutros, S.; Hofmann, J.N.; Beane Freeman, L.E.; et al. Pesticide use and incident hypothyroidism in pesticide applicators in the Agricultural Health Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2018, 126, 97008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liem, J.F.; Subekti, I.; Mansyur, M.; Soemarko, D.S.; Kekalih, A.; Suyatna, F.D.; Suryandari, D.A.; Malik, S.G.; Pangaribuan, B. The determinants of thyroid function among vegetable farmers with primary exposure to chlorpyrifos: A cross-sectional study in Central Java, Indonesia. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirikul, W.; Sapbamrer, R. Exposure to pesticides and the risk of hypothyroidism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, J.; Manro, J.; Shannon, H.; Anderson, W.; Brozinick, J.; Chakravartty, A.; Chambers, M.; Du, J.; Eastwood, B.; Heuer, J.; et al. In vivo assay guidelines (last updated on October 2012). In Assay Guidance Manual [Internet]; Markossian, S., Grossman, A., Baski, H., Arkin, M., Auld, D., Austin, C., Baell, J., Brimacombe, K., Chung, T.D.Y., Coussens, N.P., et al., Eds.; Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2012. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK92013/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Kim, J.H.; Ko, Y.; Kim, H.J.; Park, S.J. Age and sex differences in the relationship of body weight changes with colon cancer risks: A nationwide cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarım, Ö. Thyroid hormones growth in health disease. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2011, 3, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segni, M. Disorders of the thyroid gland in infancy, childhood and adolescence (last updated on March 2017). In Endotext [Internet]; Feingold, K.R., Adler, R.A., Ahmed, S.F., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M.R., Chrousos, G., Corpas, E., de Herder, W.W., Dhatariya, K., Dungan, K., et al., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279032/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Wanjari, M.; Patil, M.; Late, S.; Umate, R. Prevalence of thyroid disorder among young adults in the rural areas of Wardha district: A cross-sectional study. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 7700–7704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bégin, M.E.; Langlois, M.F.; Lorrain, D.; Cunnane, S.C. Thyroid function and cognition during aging. Curr. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. 2008, 2008, 474868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.N.; Lansdown, A.; Witczak, J.; Khan, R.; Rees, A.; Dayan, C.M.; Okosieme, O. Age-related variation in thyroid function—A narrative review highlighting important implications for research and clinical practice. Thyroid Res. 2023, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M.; Mölne, J.; Jörtsö, E.; Smeds, S.; Ericson, L.E. Plasma membrane shedding and colloid vacuoles in hyperactive human thyroid tissue. Virchows Arch. B Cell Pathol. Incl. Mol. Pathol. 1988, 56, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirahanchi, Y.; Tariq, M.A.; Jialal, I. Physiology, thyroid (last updated on February 2023). In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519566/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Mense, M.G.; Boorman, G.A. Chapter 33—Thyroid gland. In Boorman’s Pathology of the Rat, 2nd ed.; Suttie, A.W., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maathidy, A.; Alzyoud, J.A.M.; Al-Dalaen, S.; Al-Qtaitat, A. Histological alterations in the thyroid follicular cells induced by lead acetate toxicity in adult male albino rats. Int. J. Pharm. Phytopharm. Res. 2019, 9, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Kellogg, A.P.; Citterio, C.E.; Zhang, H.; Larkin, D.; Morishita, Y.; Targovnik, H.M.; Balbi, V.A.; Arvan, P. Thyroid hormone synthesis continues despite biallelic thyroglobulin mutation with cell death. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 6, e148496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes-Ferreira, M.; Farinha, L.R.L.; Costa, Y.S.O.; Pinto, F.J.; Disner, G.R.; da Rosa, J.G.D.S.; Lima, C. Pesticide-induced inflammation at a glance. Toxics 2023, 11, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruíz-Arias, M.A.; Medina-Díaz, I.M.; Bernal-Hernández, Y.Y.; Agraz-Cibrián, J.M.; González-Arias, C.A.; Barrón-Vivanco, B.S.; Herrera-Moreno, J.F.; Verdín-Betancourt, F.A.; Zambrano-Zaragoza, J.F.; Rojas-García, A.E. Hematological indices as indicators of inflammation induced by exposure to pesticides. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 19466–19476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erge, E.; Kiziltunc, C.; Balci, S.B.; Atak Tel, B.M.; Bilgin, S.; Duman, T.T.; Aktas, G. A novel inflammatory marker for the diagnosis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: Platelet-count-to-lymphocyte-count ratio. Diseases 2023, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babić Leko, M.; Gunjača, I.; Pleić, N.; Zemunik, T. Environmental factors affecting thyroid-stimulating hormone and thyroid hormone levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyna, W.; Wojciechowska, A.; Szybiak-Skora, W.; Lacka, K. The Impact of environmental factors on the development of autoimmune thyroiditis—Review. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, K.J.V.D.; van Raaij, J.A.G.M.; Bragt, P.C.; Notten, W.R.F. Interactions of halogenated industrial chemicals with transthyretin and effects on thyroid hormone levels in vivo. Arch. Toxicol. 1991, 65, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kackar, R.; Srivastava, M.K.; Raizada, R.B. Studies on rat thyroid after oral administration of mancozeb: Morphological and biochemical evaluations. J. Appl. Toxicol. 1997, 17, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thambirajah, A.A.; Wade, M.G.; Verreault, J.; Buisine, N.; Alves, V.A.; Langlois, V.S.; Helbing, C.C. Disruption by stealth—Interference of endocrine disrupting chemicals on hormonal crosstalk with thyroid axis function in humans and other animals. Environ. Res. 2022, 203, 111906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Barceló, D.; Clougherty, R.J.; Gao, B.; Harms, H.; Tefsen, B.; Vithanage, M.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Wells, M. “Potentially toxic element”─Something that means everything means nothing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 11922–11925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, M.; Oliveri Conti, G.; Caltabiano, R.; Buffone, A.; Zuccarello, P.; Cormaci, L.; Cannizzaro, M.A.; Ferrante, M. Role of emerging environmental risk factors in thyroid cancer: A brief review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leemans, M.; Couderq, S.; Demeneix, B.; Fini, J.B. Pesticides with potential thyroid hormone-disrupting effects: A review of recent data. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandramohan, M.S.; da Silva, I.M.; da Silva, J.E. Concentrations of potentially toxic elements in topsoils of urban agricultural areas of Rome. Environments 2024, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, B.; Maddela, N.R.; Venkateswarlu, K.; Megharaj, M. Organic farming: Does it contribute to contaminant-free produce and ensure food safety? Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 769, 145079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nankongnab, N.; Kongtip, P.; Kallayanatham, N.; Pundee, R.; Yimsabai, J.; Woskie, S. Longitudinal study of thyroid hormones between conventional and organic farmers in Thailand. Toxics 2020, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nankongnab, N.; Kongtip, P.; Tipayamongkholgul, M.; Bunngamchairat, A.; Sitthisak, S.; Woskie, S. Difference in accidents, health symptoms, and ergonomic problems between conventional farmers using pesticides and organic farmers. J. Agromed. 2020, 25, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Li, X.; Qiu, Y.; Zeng, X.; Yu, X.; Wang, W.; Yi, X.; Huang, L. Low-dose effects on thyroid disruption in zebrafish by long-term exposure to oxytetracycline. Aquat. Toxicol. 2020, 227, 105608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, A.J.; Seibert, T.; Allen, D.B. Severe and persistent thyroid dysfunction associated with tetracycline-antibiotic treatment in youth. J. Pediatr. 2016, 173, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, P.; Chamot, S.; Al-Salameh, A.; Cancé, C.; Desailloud, R.; Bonneterre, V. Farming activity and risk of treated thyroid disorders: Insights from the TRACTOR project, a nationwide cohort study. Environ. Res. 2024, 249, 118458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). National summary reports on pesticide residue analysis performed in 2021. EFSA Support. Publ. 2023, 20, EN-7901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). National summary reports on pesticide residue analyses performed in 2022. EFSA Support. Publ. 2024, 21, EN-8751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). National summary reports on pesticide residue analyses performed in 2023. EFSA Support. Publ. 2025, 22, EN-9320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.