Abstract

This study first analyzes the ecotoxicity of bentazone (BTZ), an herbicide detected in the Albufera Natural Park. BTZ exhibits an EC50 (5 days) towards Lactuca sativa of 900 mg L−1, showing a hormetic effect. The toxic effects of a BTZ, , and mixture are generally lower than the individual toxic effects considered additively. However, possible synergy on ecotoxicity was observed at 600 mg L−1 of BTZ in the presence of 2.8 g L−1 of and 0.8 g L−1 of . A statistical model was obtained to predict the ecotoxicity thresholds towards Lactuca sativa for combinations of the three compounds. In general, when the concentration of one compound increases, a lower concentration of the others is necessary for the mixture to be toxic. However, in the presence of , below 382 mg L−1 of BTZ, the concentrations of both compounds need to be increased. This is attributable to the hormetic behavior of BTZ. This BTZ concentration decreases as the concentration increases. Secondly, the effectiveness of electrooxidation and photoelectrooxidation processes to eliminate BTZ was studied. A ceramic anode made of Sb- and coated with a photocatalyst was used. The degradation and mineralization degrees achieved using a mixture of 0.46 g L−1 of and 1.3 g L−1 of (like the Albufera lake conditions) show intermediate values between those achieved with pure electrolytes. Specifically, applying 0.6 A, they are very close to the maximum values achieved with pure . Moreover, the final effluent’s toxicity is significantly lower, especially when light is applied. Therefore, the photoelectrooxidation process applying 0.6 A with the mixed electrolyte is the most effective technique from the combined point of view of final degradation (90.9%), mineralization (62.4%), and toxicity.

1. Introduction

The current global population requires a large consumption of drinking water [1,2] in homes, hospitals, and industries. This generates a high wastewater load that must be treated at wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). These plants have become a focus of attention at the European level due to the pollution of both their influents and effluents.

Current WWTPs typically employ three types of treatment: primary, secondary, and, in some cases, tertiary. However, it has been observed that these conventional treatments are ineffective against certain emerging contaminants, known as micropollutants. Examples include pharmaceuticals, pesticides, industrial chemicals, surfactants, and personal care products. These have all been detected in groundwater, surface water, municipal wastewater, drinking water, and even food. These micropollutants, although present in low concentrations in the aquatic environment, are highly persistent due to their low biodegradability. This problem is becoming increasingly critical due to their potential long-term adverse effects on the environment and human health.

The recent Directive (EU) 2024/3019 on the treatment of urban wastewater has urged the search for and development of techniques to be implemented as quaternary treatments, capable of reducing both the concentration and toxicity of micropollutants. This directive also mandates the inclusion of these quaternary treatments in WWTPs serving more than 150,000 inhabitants (and in those serving more than 10,000 inhabitants when discharging into areas sensitive to micropollutants). The aim is to reduce the concentration of micropollutants by at least 80%. And this objective must be achieved no later than the end of 2045 [3].

With this measure, the European Union aims to prevent micropollutants detected in WWTP effluents from harming human, animal, and environmental health, given the considerable rate of reuse of this water. In 2022, 10.90% of the water treated in WWTPs in Spain was used for reuse; and this percentage rose to 34.93% in the Valencian Region [4]. Furthermore, 71.4% of the total reused water in Spain was used for agricultural activities; and this percentage reached 87.5% in the Valencian Region [5]. The presence of micropollutants in reused water is particularly concerning in sensitive agricultural areas. This is the case for the Albufera Natural Park. Located south of the city of Valencia (Spain), this natural park is one of the most representative and valuable coastal wetlands in the Mediterranean basin. Since 1986, it has been recognized as a “Wetland of International Importance” [6,7]. The park comprises various aquatic systems, such as the Albufera lake, rice paddies, irrigation canals, and drainage channels. It is a traditional rice-growing area where several micropollutants, such as pesticides, have been detected. Among the pesticides detected in these waters, bentazone and tricyclazole stand out due to their high and persistent concentrations [8,9].

Bentazone (hereinafter, BTZ) is an herbicide commonly used for controlling broadleaf weeds and sedges in corn fields, rice paddies, and other intensive crops. It belongs to the benzothiazole class and acts as a photosynthesis inhibitor in target plants, causing their death. It is usually applied post-emergence, allowing for the control of weeds during their growth phase, minimizing damage to established crops [10]. Regarding BTZ toxicity, it has been considered moderately toxic when ingested and slightly toxic due to dermal absorption in mammals [11]; however, ingestion of large doses can cause acute hepatitis, acute renal failure, and even death [12]. Ecotoxicity studies of BTZ in aquatic invertebrates such as Daphnia magna have also been conducted [13,14]. However, no studies have been found that analyze ecotoxicity in higher plants, such as lettuce (Lactuca sativa) which has been recommended as a bioindicator for determining the toxicity of soil and water samples [15,16,17].

Regarding the techniques that can be implemented as quaternary treatments in WWTPs, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) have emerged in recent years as one of the most promising technologies. The advantages of AOPs are their high mineralization efficiency, broad applicability, and ability to effectively degrade persistent organic compounds, such as micropollutants [18]. Among AOPs, electrochemical processes such as electrooxidation and photoelectrooxidation stand out. These processes use electricity to degrade micropollutants without the need for chemical additives and at relatively low application costs. They are economical, versatile, environmentally friendly, energy-efficient, and easily automated. These characteristics make them attractive methods for treating micropollutants, whether for their complete oxidation to or for their transformation into biodegradable compounds [19].

Electrooxidation can be carried out directly (the contaminant is oxidized on the anode surface) or indirectly (the contaminant is oxidized by oxidizing species that are electrochemically generated). The main electrochemically generated species is the hydroxyl radical (•OH); depending on the medium, other species can also be formed such as hypochlorite, chlorate, or perchlorate anions (in the presence of chlorides) and persulfate anions (in the presence of sulfates). Boron-doped diamond anodes stand out for their high electrochemical stability, corrosion resistance, and ability to generate large quantities of hydroxyl radicals. These qualities make them a very efficient option for the degradation of recalcitrant pollutants. However, the high cost of these materials limits their large-scale application [20]. Therefore, current research is focused on developing new materials that offer a balance between efficiency and economic viability. These new materials include ceramic anodes composed of doped with metals or catalysts, which are the focus of our research group [21,22,23].

In the case of photoelectrooxidation, light is additionally irradiated onto the anode surface. Several studies highlight this technology for its speed and efficiency in contaminant degradation due to the synergistic effect between the electrochemically and photochemically generated radicals [24,25,26].

Several studies have investigated the degradation of BTZ through photolysis [27,28] and photocatalysis using titanium dioxide (TiO2) as a catalyst [29,30,31]. These studies have shown that neither photolysis nor photocatalysis lead to complete mineralization of BTZ. They favor incomplete or partial transformation pathways, resulting in the formation of multiple intermediate by-products. These include dimers, hydroxylated derivatives, ketones, and partially oxidized species [29]. To improve the mineralization degree, these processes could be combined with electrochemical techniques. However, few studies have applied photoelectrooxidation to degrade BTZ. García-Bessegato studied the photoelectrochemical degradation of BTZ on TiO2-modified carbon electrodes, obtaining a degradation degree of 40% after 90 min [32]. Therefore, further research is needed to achieve higher levels of both degradation and mineralization degrees for BTZ.

In this context, this study has two main objectives. The first objective is to assess the ecotoxicity of water contaminated with BTZ, a micropollutant detected in the Albufera Natural Park. For this purpose, germination bioassays with lettuce (Lactuca sativa) seeds are performed. The aim is to study the ecotoxicity of BTZ, its interaction with the environment, analyze its potential synergistic or antagonistic effects, and, using statistical tools, mathematically model its behavior. The second objective of this study is to analyze the effectiveness of electrooxidation and photoelectrooxidation processes in reducing BTZ ecotoxicity. These are promising advanced oxidation techniques that can be used as a quaternary treatment in WWTPs. In this study, they are applied to the degradation of BTZ using a low-cost ceramic anode made of Sb- and coated with a bismuth tungstate () photocatalyst.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Solutions for BTZ Ecotoxicity Analysis

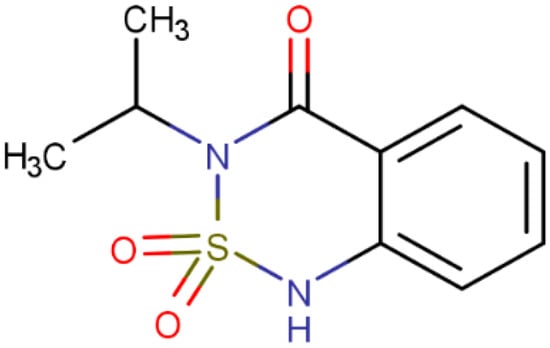

The waters of the Albufera lake are characterized by relatively variable concentrations of sulfates and chlorides over time [33]. Therefore, this study first aimed to analyze the impact that these two compounds may have on the ecotoxicity of BTZ. That is, the aim is to study the ecotoxicity of samples containing BTZ, sodium chloride (), and sodium sulfate () at varying concentrations of each compound. Figure 1 shows the molecular structure of BTZ (3-isopropyl-1H-2,1,3-benzothiadiazin-4(3H)-one 2,2-dioxide, ). BTZ has an aromatic ring that confers toxicity. In addition, some authors have observed that the interaction between nitrogen and sulfur atoms has a significant impact on toxicity. This impact increases as the geometric distance between these atoms decreases [34]. According to Figure 1, this would be the case for BTZ.

Figure 1.

Structure of the BTZ molecule.

First, the individual ecotoxicity of BTZ and was determined; the ecotoxicity of had already been determined in previous work [35]. To determine the ecotoxicity of BTZ, 9 samples with concentrations in the range 50–1200 mg L−1 were prepared from a commercial aqueous solution of 480 g L−1 BTZ (Shandong Zhongfu Chemical Co., Ltd., Weifang, Shandong, China). To determine the ecotoxicity of , 7 samples with concentrations ranging from 1 to 6 g L−1 were prepared using sodium chloride from J.T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ, USA. The used was analytical-grade sodium sulfate from Panreac, Castellar del Vallès, Barcelona, Spain.

Once the individual ecotoxicities of the three compounds were determined, an experimental design was developed using Statgraphics Plus 5.1 software to define the concentration combinations to be tested. A total of 64 samples were prepared using all possible combinations of the following concentrations: 0, 300, 600, and 900 mg L−1 of BTZ; 0, 0.8, 1.6, and 2.4 g L−1 of ; and 0, 1.4, 2.8, and 4.2 g L−1 of Na2SO4. The maximum concentration for each compound was set equal to or slightly below its individual ecotoxicity threshold.

All samples in Section 2.1 were prepared using ultrapure water (Type I water quality according to the ASTM D1193-06 standard [36]) with a maximum conductivity of 0.0555 μS cm−1 at 25 °C. The pH was adjusted, if necessary, with 0.1 M sodium hydroxide (analytical grade NaOH from Panreac) or with 0.1 M hydrochloric acid (, J.T. Baker) or 0.1 M sulfuric acid (, J.T. Baker). This is because the optimal pH range for lettuce seed root growth is 5.5–8.

2.2. Ecotoxicity Measurements Towards Lactuca sativa and Statistical Analysis

The procedure to measure ecotoxicity towards Lactuca sativa consisted of placing a 90 mm diameter filter paper (Whatman “Qualitative 3”) in a Petri dish. Next, the filter paper was impregnated with 3 mL of the sample. Then, 20 seeds of Lactuca sativa Batavia “Reina de Mayo” variety (Intersemillas, Inc., Loriguilla, Valencia, Spain), stored at 5 °C in a refrigerator, were placed on the filter paper. The seeds were distributed as evenly as possible, with sufficient spacing between them to prevent interference during root growth. Then, the Petri dish was covered and placed in a Medilow-M refrigerated incubator (J.P.Selecta, Abrera, Barcelona, Spain) at 20 °C for 120 h (5 days) in complete darkness. After the incubation period, the root elongation was measured.

For each sample, three Petri dishes were prepared (three replicates), meaning a total of 60 seeds were tested per sample. In addition, a negative control sample (in three Petri dishes) containing ultrapure water was included in each experiment. This control sample allowed determination of the ecotoxicity of the samples being tested. It should be noted that an experiment is considered valid when at least 65% of the seeds in the control sample germinate.

The measured root elongation data were processed as follows: for each sample, the mean value and standard deviation were calculated and the p-value was obtained using the statistical software PAST (PAleontological STatistics), version 5.2.1. The p-value is defined as the probability that the difference between a statistical variable in two data sets is equal to or greater than the observed value [37]. In this case, the variable is the mean root elongation, and the two data sets being compared are those corresponding to a sample and the control (ultrapure water). The lower the p-value, the stronger the evidence against the null hypothesis [38]. Specifically, samples with a mean root elongation less than 50% of that corresponding to the control sample (ultrapure water) and a p-value < 0.05 are considered toxic. Therefore, the ecotoxicity (EC50 (5 days)) of a substance is expressed as the concentration that causes 50% inhibition of root growth in Lactuca sativa seeds compared to the control (ultrapure water).

To analyze the data set of samples used in the experimental design described in Section 2.1, a relative parameter is required since not all the samples (with their three replicates) could be placed in the refrigerated incubator at the same time. The chosen parameter is the decrease in root elongation (DRE), which was calculated relative to ultrapure water control, according to Equation (1):

where Lc is the average root length developed in contact with the control solution (ultrapure water) and L is the average root length for the problem sample.

DRE (%) = ((Lc − L)/Lc) × 100

The DRE values were used to analyze the potential synergistic effect on ecotoxicity of the three compounds studied (BTZ, , and ). The DRE calculated according to Equation (1) is called the observed DRE because it was obtained experimentally. The observed DRE were compared to the predicted DRE, defined as the sum of the observed DREs for samples containing a single compound individually. In this way, experimental data were compared with an addition model for predicting the toxicity of mixtures [39]. If the observed DRE is greater than the predicted DRE, this means that there is a synergistic effect between the compounds of that sample.

Furthermore, using Statgraphics Plus 5.1 software, the response surface methodology (RSM) was applied to define a mathematical function relating to the observed DRE (response variable) to the concentrations of BTZ, , and (experimental factors). For this purpose, the experimental data obtained for the 64 samples of the experimental design described in Section 2.1 were used. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess whether the effect of the three experimental factors and their interactions on the response variable was statistically significant. Outliers were discarded after analyzing the difference between the experimentally obtained DRE values and those predicted by the mathematical model (this difference is the residuals). Outliers were identified by the box and whisker plot. In addition, the normality of the residuals was checked using the standardized coefficients of skewness and kurtosis (both included in the range [−2, 2]), the normal probability plot, and the Shapiro–Wilk normality test.

2.3. Electrooxidation and Photoelectrooxidation Experiments

The second objective of this study is to analyze the effectiveness, in terms of ecotoxicity, of electrooxidation and photoelectrooxidation processes on effluents containing BTZ. To achieve this, a total of 12 tests were carried out.

Three solutions were prepared using ultrapure water, all with a concentration of 100 mg L−1 of BTZ, but using three different supporting electrolytes: 1.65 g L−1 of ; 2 g L−1 of ; and a mixture of both compounds corresponding to 0.46 g L−1 of and 1.3 g L−1 of . The three electrolytes provide a similar conductivity value in all three solutions. The latter combination of concentrations is of the same order of magnitude as the average concentration detected in the Albufera lake in 2024 [33]. Each of these three solutions was tested for 4 h using two current intensities (0.2 and 0.6 A), both in the absence (electrooxidation) and presence of light (photoelectrooxidation).

For these experiments, a 250 mL quartz reactor was used. The anode was a ceramic electrode made of Sb-, coated with a bismuth tungstate () photocatalyst, with a surface area of 12 cm2. This photoanode was described in detail in a previous study [40]. The cathode was a 24 cm2 sheet of AISI 304 stainless steel. The light source illuminating the photoanode was a xenon lamp (Hamamatsu Lightningcure LC8 200 W, Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). The temperature of the reactor was kept at 25 °C by using a thermostatically controlled water bath.

In these tests, the ecotoxicity towards Lactuca sativa seeds was assessed, both for the initial solutions and after 4 h of treatment. In addition to using ultrapure water as a control, a second control solution was included, consisting of the supporting electrolyte at the same concentration as in the other samples.

The ecotoxicity results obtained were related to the percentage of degradation achieved, defined as the decrease in BTZ concentration, and the percentage of mineralization achieved, defined as the decrease in total organic carbon (TOC). The BTZ concentration and TOC value were measured using an Unicam UV4-200 UV/Vis spectrometer (Ati Unicam, Cambridge, UK) at 225 nm and a Shimadzu TNM-L ROHS TOC analyzer (Shimadzu Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), respectively [40].

To corroborate the results obtained, the ecotoxicity of the samples was also determined in these tests using a high-sensitivity Microtox M-500 photometer (Strategic Diagnostics Inc., Newark, NJ, USA). This instrument measures the toxicity of a solution by detecting changes in the bioluminescence of the bacterium Vibrio fischeri. This bacterium emits light because of its metabolic respiration process. Therefore, a decrease in cellular respiration due to the presence of any toxic substance translates into a decrease in light emission. The measurements were performed at a temperature of 15 °C, 2% salinity, and an exposure time of 15 min. The MicrotoxOmni 4.2 software, supplied with the instrument, calculates the toxicity value in TU (toxicity units). A toxicity equal to n-TU means that the sample must be diluted n times to inhibit the luminescence of the bacteria by 50%.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. BTZ, NaCl, and Na2SO4 Individual Ecotoxicity Towards Lactuca sativa

Bioassays using higher plants allow for the collection of ecotoxicity data during the early stages of seed germination and growth. More specifically, inhibition of root elongation is considered a valid and sensitive indicator of environmental ecotoxicity [15].

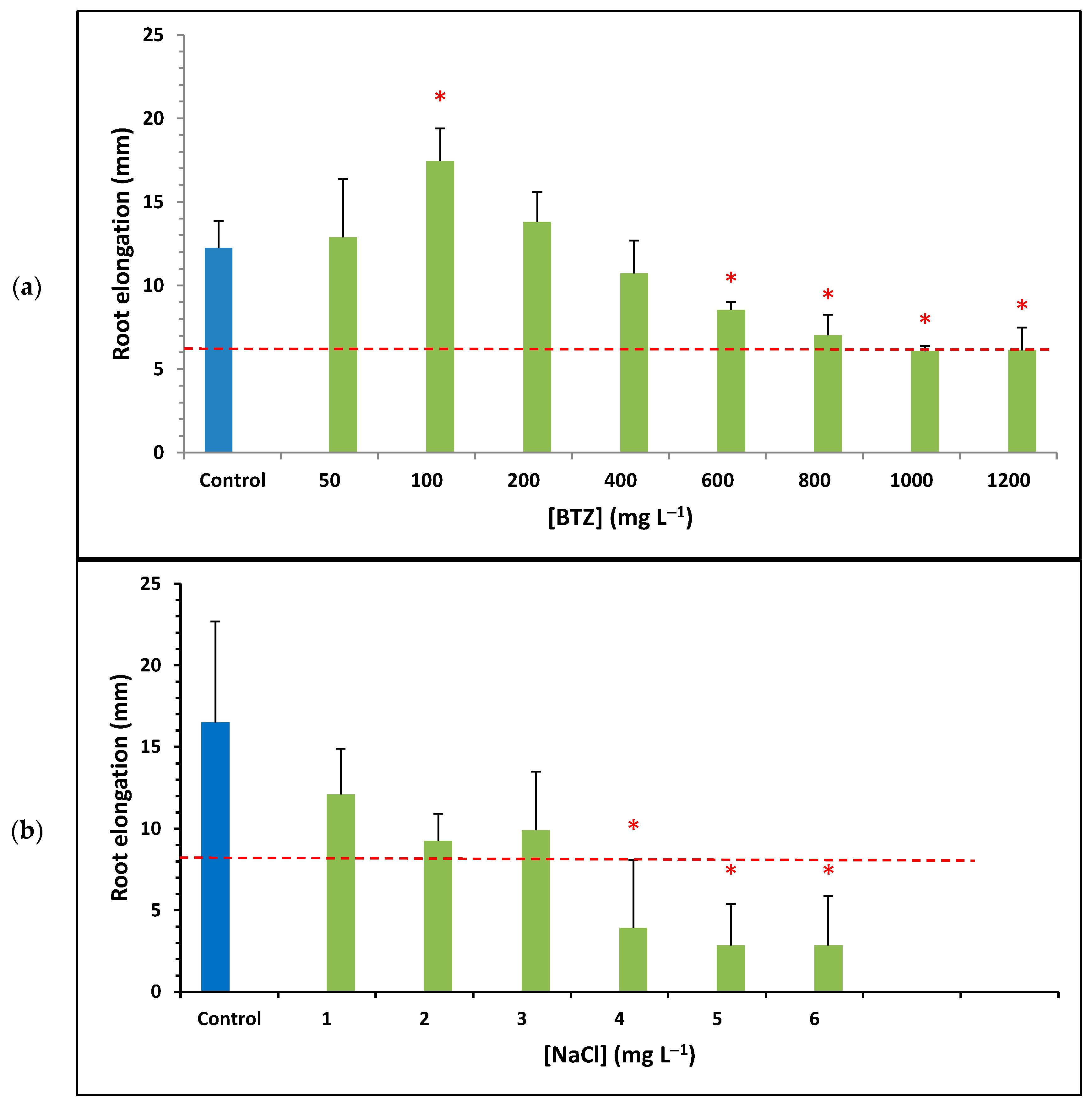

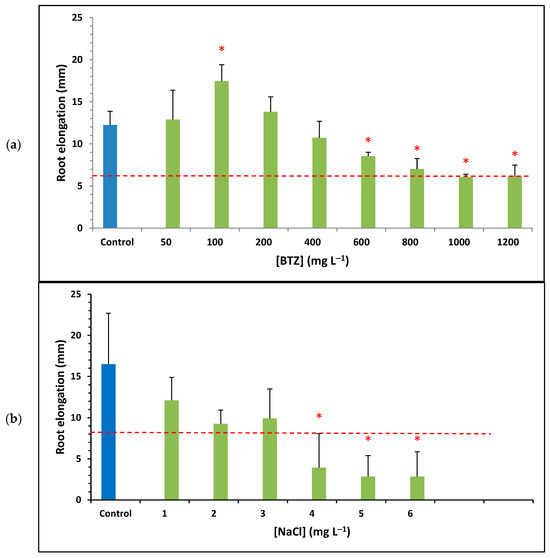

Figure 2 shows the results of the average root elongation obtained for different concentrations of BTZ and (green bars), as well as for the ultrapure water control (blue bar); the standard deviation is shown using error bars. The red asterisk above a bar indicates that the data have a p-value < 0.05, meaning that the difference from the control is statistically significant at a 95% confidence level. The horizontal dashed red line represents 50% of the root elongation observed for the control sample. Based on this, samples with an average root elongation below the red line and an asterisk are considered toxic, according to the US EPA OPPTS 850.4200 standard [41].

Figure 2.

Average root elongation of Lactuca sativa seeds for different concentrations of (a) BTZ and (b) . Error bars represent the standard deviation of three replicates; red asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from the control (ultrapure water) with a p-value < 0.05; and the red dashed line defines the threshold for determining whether a sample is toxic.

Figure 2a shows that, at low concentrations of BTZ (up to 200 mg L−1), the root elongation of the seeds is similar to, or even greater than, that of the control sample, especially at 100 mg L−1, where a significant increase is observed. Furthermore, at low BTZ concentrations, root elongation increases as the BTZ concentration increases, reaching a maximum at 100 mg L−1. Beyond this value, root elongation decreases as the BTZ concentration increases. This behavior can be attributed to a hormetic effect of the herbicide. Herbicides act on the physiological processes of plants, inhibiting their growth; however, when applied at low doses, they can have a positive effect on plant development. The molecular mechanism of herbicide-induced hormesis is still unknown, although it is known that mild stress triggers a compensatory response, leading to greater growth and more efficient reproductive processes [42]. Other authors have also observed the hormetic effect of BTZ on common sage plants (Salvia officinalis), indicating that the plant’s enzymatic systems can neutralize the toxic effects of the herbicide [43].

At concentrations above 800 mg L−1, BTZ is considered toxic to Lactuca sativa since the observed root elongation is less than 50% of that of the control solution, which is corroborated by the p-value. The toxicity threshold was calculated by linearly interpolating the data starting from 100 mg L−1 and finding the point of intersection with the horizontal line representing 50% of root elongation for ultrapure water. Thus, the ecotoxicity value of BTZ towards Lactuca sativa, expressed as EC50 (5 days), was determined to be 900 mg L−1 (3.75 mmol L−1).

Figure 2b shows the root elongation of the seeds at different concentrations. For all concentrations tested, root elongation is lower than that of the control sample. Furthermore, as the concentration increases, root elongation decreases; and at a concentration of 4 mg L−1, the solution was already toxic towards Lactuca sativa. After performing a linear interpolation of the data, the ecotoxicity towards Lactuca sativa of , expressed as EC50 (5 days), is 2.53 g L−1 (43.29 mmol L−1). Other researchers also analyzed the ecotoxicity towards Lactuca sativa of and obtained an EC50 (5 days) value equal to 5.7 g L−1 for germination. However, they observed effects on root growth even at a concentration of 1 g L−1 of , concluding that root growth is more sensitive to than germination [44].

Regarding the ecotoxicity towards Lactuca sativa of , this was not determined experimentally because it had already been established in a previous study, with an EC50 (5 days) value equal to 4.8 g L−1 (33.79 mmol L−1) [35].

When comparing the ecotoxicity towards Lactuca sativa of the three compounds in mmol L−1, BTZ herbicide is about 10 times more toxic than the two salts studied ( and ). This is because a 10-times-lower concentration of BTZ is required to inhibit the root elongation of Lactuca sativa seeds by 50%. In turn, the ecotoxicity of is somewhat greater than that of , as 33.79 mmol L−1 of the former is required, compared to 43.29 mmol L−1 of the latter, to inhibit root elongation by 50%. This behavior is similar to that found in the literature for the ecotoxicity towards the microcrustacean Daphnia magna, expressed as EC50 (48 h), of these two salts: 0.874 g L−1 (14.96 mmol L−1) for [45] and 1.766 g L−1 (12.43 mmol L−1) for [46]. However, the EC50 (48 h) value towards Daphnia magna for BTZ is 3900 mg L−1 (16.23 mmol L−1) [14]; that is, the BTZ herbicide exhibits lower toxicity towards the microcrustacean than the two salts studied, although of the same order of magnitude in mmol L−1.

3.2. Synergistic Effect on Ecotoxicity Towards Lactuca sativa of BTZ, NaCl, and Na2SO4

Synergy is the phenomenon by which two or more factors, when interacting, produce an effect greater than the sum of their individual effects. In the field of ecotoxicity, synergy refers to the ability of two or more substances to produce toxic effects greater than those they would produce if their individual toxic effects were considered additively.

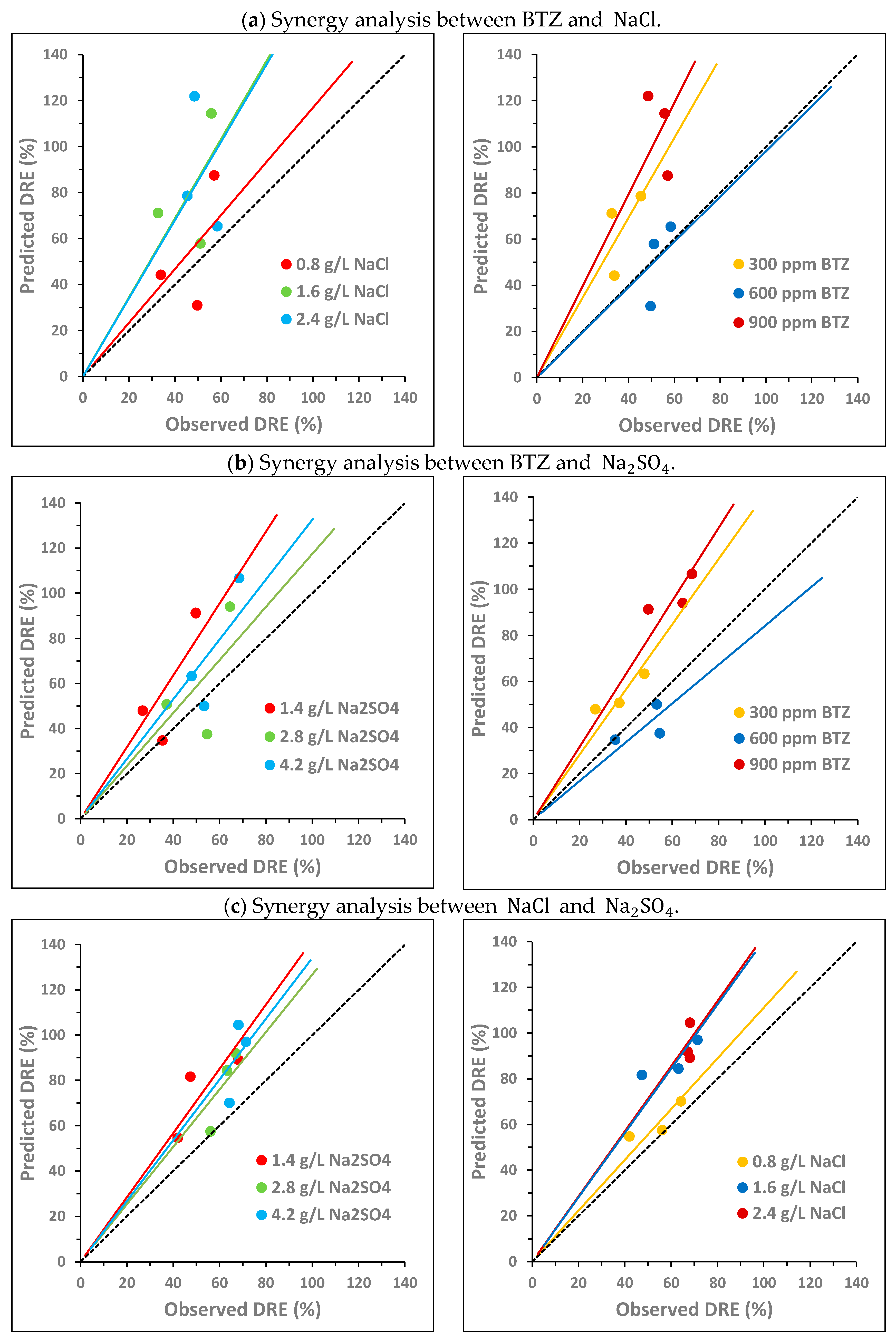

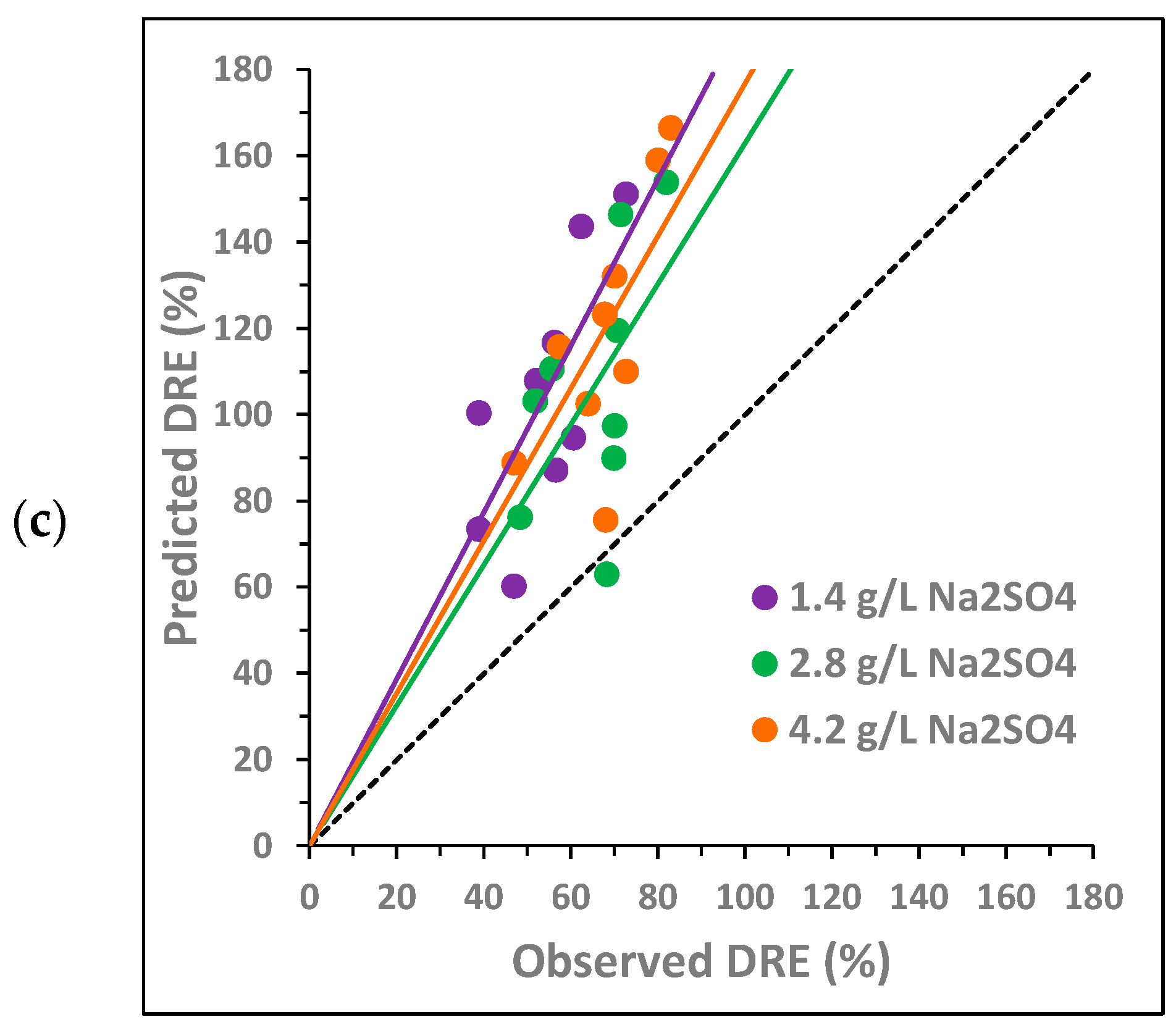

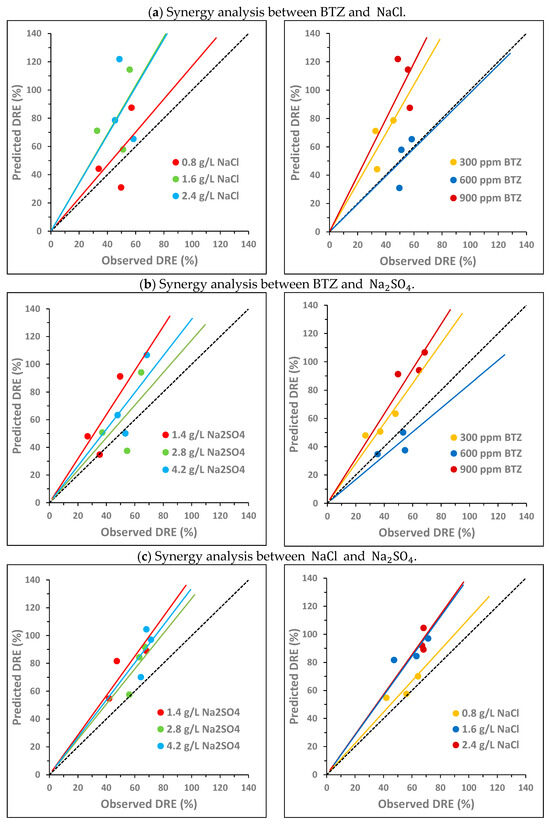

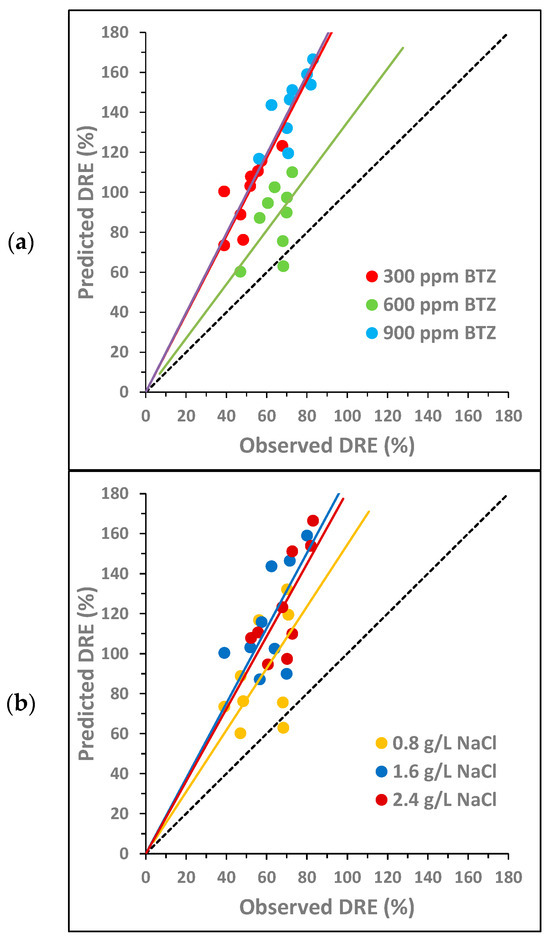

To analyze the potential synergy between the three compounds under study, the following two variables were compared: the observed DRE and the predicted DRE, both defined in Section 2.2. Figure 3 and Figure 4 plot the predicted DRE versus the observed DRE for the samples from the experimental design described in Section 2.1 (Table S1 shows the data used to obtain these values). In the graphs, the black dashed line represents the bisector, which is the area in which the observed DRE equals the predicted DRE. Each point in the graph corresponds to one of the concentration combinations studied. None of the points above the bisector show synergy, since the additive effect is greater than the observed effect. In this case, an antagonistic effect occurs between the compounds. Conversely, if a point is below the bisector, this implies that the observed effect is greater than the additive effect. Therefore, there is synergy between the compounds, since the experimental decrease is greater than the predicted decrease as a sum of the individual decreases. Finally, when a point is located on the bisector, then the effect is additive; that is, the observed decrease is equal to the sum of the individual decreases.

Figure 3.

Pairwise synergy analysis between BTZ, and on toxicity towards Lactuca sativa: comparison between the predicted decrease in root elongation (DRE), calculated as the sum of the individual effects, and the observed DRE. The black dashed line corresponds to the bisector. The solid lines show the general trend of the points with the same color.

Figure 4.

Combined synergy analysis between BTZ, , and on toxicity towards Lactuca sativa for different concentrations of (a) BTZ, (b) , and (c) : comparison between the predicted decrease in root elongation (DRE), calculated as the sum of the individual effects, and the observed DRE. The dotted line corresponds to the bisector. The solid lines show the general trend of the points with the same color.

Figure 3 analyzes the potential pairwise synergy of BTZ, , and using nine combinations of BTZ and (Figure 3a); nine combinations of BTZ and (Figure 3b); and nine combinations of and (Figure 3c). The concentrations of the compounds are as follows: 300, 600, and 900 mg L−1 of BTZ; 0.8, 1.6, and 2.4 g L−1 of ; and 1.4, 2.8, and 4.2 g L−1 of Na2SO4. For each pair of compounds, two graphs are shown, each with the same points but colored differently depending on the concentration of each substance. The solid lines indicate the general trend of points with the same color, i.e., with the same concentration of a given compound.

For the BTZ– pair, Figure 3a shows that, in general, there is no synergy between the compounds in the range of concentrations studied. In Figure 3a (left), it is observed that, as the NaCl concentration increases, the points move further away from the bisector, increasing the antagonistic effect between both compounds. In Figure 3a (right), it is also observed that, as the BTZ concentration increases, the antagonistic effect between both compounds is greater. However, at the intermediate BTZ concentration (600 mg L−1), the general trend of the points overlaps with the bisector, indicating an additive effect. In fact, the point corresponding to the combination of 600 mg L−1 of BTZ and the lowest concentration (0.8 g L−1) is below the bisector, suggesting a synergistic effect between BTZ and under these conditions. The interactions between pesticides and sodium chloride in freshwater systems are complex and can exhibit synergistic, additive, or antagonistic effects on toxicity [47]. Other authors observed that the presence of in irrigation water, at a higher concentration than those analyzed in this study (11.7 g L−1 of ), provided partial protection against Cd- and Cu-induced toxicity in the halophyte species Atriplex halimus [48].

For the BTZ– pair, in general, Figure 3b does not show a significant synergistic effect between both compounds in the range of concentrations analyzed. In Figure 3b (left), it is observed that, at the highest concentrations, the points get closer to the bisector, decreasing the antagonistic effect between both compounds. This behavior is contrary to that observed for . In Figure 3b (right), the behavior of BTZ is very similar to that observed in combination with : the higher the BTZ concentration, the greater the antagonistic effect with . And again, an exception is observed at 600 mg L−1 of BTZ. For this intermediate BTZ concentration, the points are slightly below the bisector for the three concentrations evaluated, indicating that there is a slight synergistic effect between both compounds, especially at 2.8 g L−1 of . In a previous study of atenolol toxicity towards Lactuca sativa, a clear antagonistic effect was also observed at the lowest concentration studied (2 g L−1). Furthermore, the magnitude of the antagonistic effect also decreased as the concentration increased until an additive effect was observed at the highest concentration analyzed (6 g L−1) [49]. Other authors have studied the toxicity of Cd towards a microalga (Chlamydomonas moewussi) and have also observed that produces an antagonistic/synergistic effect depending on its concentration [50]. They attribute this behavior to the fact that sulfate is an important nutrient that can induce physiological responses to mitigate Cd toxicity. However, an excess of nutrients can be toxic to microorganisms, increasing the toxic behavior of Cd.

Finally, for the – pair, Figure 3c shows that no synergy occurs between both compounds in the range of concentrations studied. Figure 3c (left) shows that, at higher concentrations, the antagonistic effect between both compounds decreases. However, Figure 3c (right) shows that as the concentration increases, the antagonistic effect increases. Therefore, the behavior of both compounds is similar to that observed for each of them in combination with BTZ. The point closest to the bisector (additive effect) corresponds to the combination of 0.8 g L−1 of and 2.8 g L−1 of . Other authors have also observed a similar behavior of both compounds when analyzing their toxicity towards two crustaceans (Hyalella azteca and Ceriodaphnia dubia). At low concentrations, the toxicity of showed a positive correlation with the chloride concentration. In contrast, at high concentrations, toxicity showed a negative correlation with chloride concentration [51].

In summary, the pairwise analysis of the potential synergistic effect of the three compounds shows that, in general, their behavior is antagonistic. However, pairwise synergy could occur at concentrations of 600 mg L−1 of BTZ, 0.8 g L−1 of , and 2.8 g L−1 of . The statistical analysis of the pairwise interactions by ANOVA is shown in Section 3.3.

Figure 4 analyzes the potential synergy of the three compounds (BTZ, , and ) using 27 concentration combinations. The three graphs represent the same points, but they are colored differently depending on the concentration of each compound. Again, the solid lines indicate the general trend of points with the same color, i.e., at the same concentration of a given compound.

For the joint combination of BTZ–, Figure 4 shows that no synergy occurs between the three compounds in the range of concentrations analyzed. As observed in the pairwise analysis, the antagonistic effect is lower at the concentration of 600 mg L−1 of BTZ (Figure 4a), the lower NaCl concentration (Figure 4b), and the higher concentrations of Na2SO4 (Figure 4c). The only point below the bisector corresponds to the combination of 600 mg L−1 of BTZ, 0.8 g L−1 of , and 2.8 g L−1 of , and a synergistic effect between the three compounds may occur under these conditions. These concentrations are the same as those observed in the pairwise analysis as potential inducers of a synergistic effect.

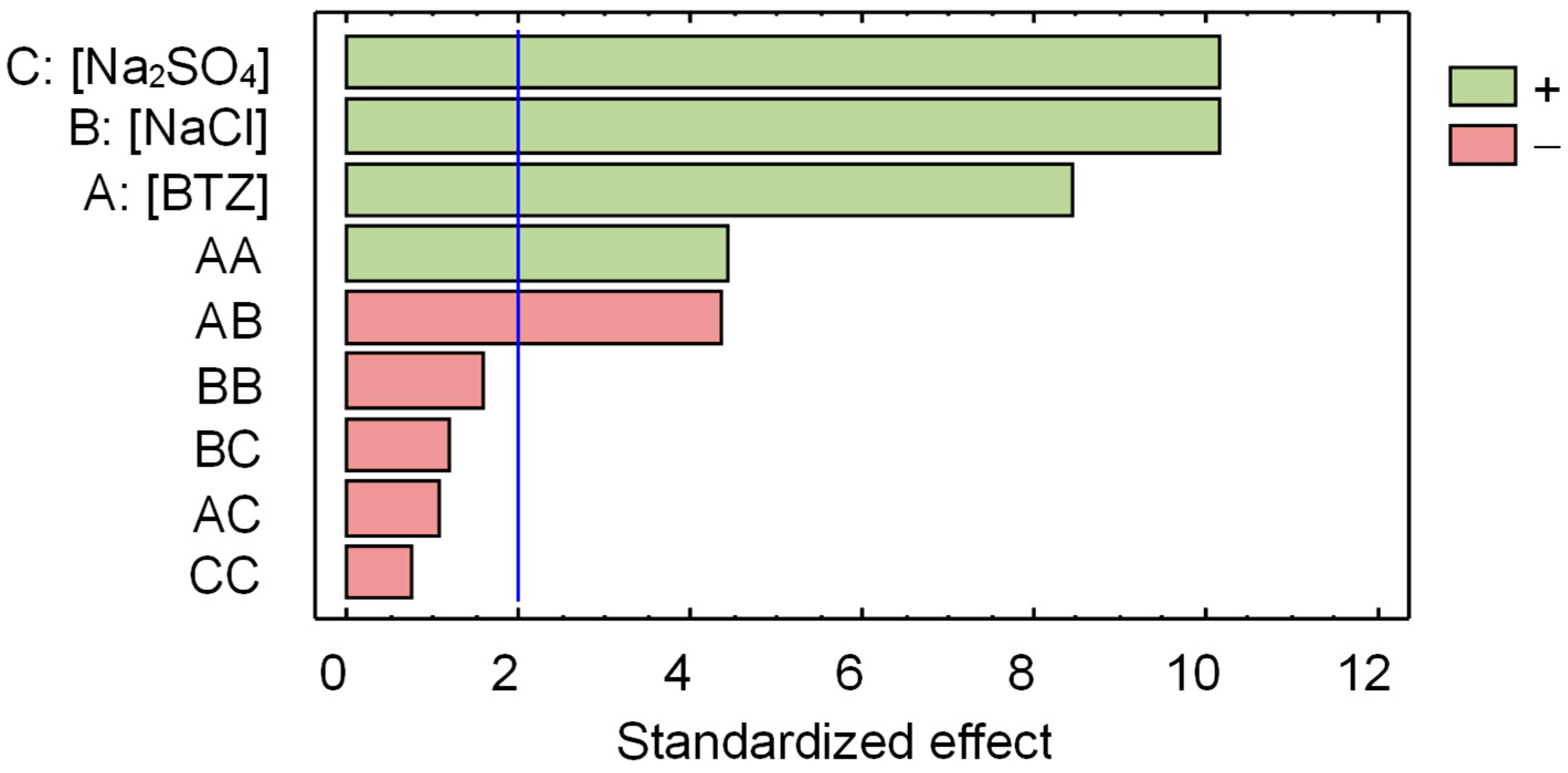

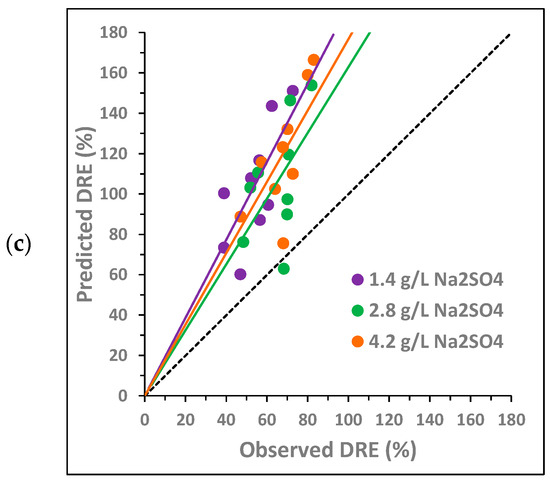

3.3. Ecotoxicity Threshold Towards Lactuca sativa for Mixtures of BTZ, NaCl, and Na2SO4

The statistical analysis of the observed DRE identified only one outlier, and the corresponding sample was discarded from the study. Figure 5 shows the Pareto chart obtained using ANOVA. This is a bar graph that quantifies the effect of the three compounds’ concentrations and their interactions on the observed DRE. The vertical blue line represents the significance threshold at a 95% confidence level. Factors and interactions that do not exceed this line are considered statistically insignificant. As can be seen in Figure 5, the concentrations of all three compounds have a statistically significant effect on the DRE. Moreover, their effects are positive, indicating that as their values increase, the DRE value increases. It should be noted that the effect of and concentrations has the same significance on the DRE; and this is greater than the effect of BTZ concentration. Regarding the pairwise interactions between the three compounds’ concentrations, only the pair BTZ– (AB in Figure 5) has a statistically significant effect on the DRE.

Figure 5.

Pareto chart for the decrease in root elongation (DRE) of Lactuca sativa seeds. The vertical line identifies the 95% significance threshold. Table S2 shows the corresponding ANOVA table.

After discarding the statistically non-significant interactions between factors identified by ANOVA (see BB, BC, AC, and CC in Figure 5), the RSM methodology was applied. The result was the following second-order regression model that relates the DRE, expressed as a percentage, to the concentrations of the three compounds (Equation (2)):

where [BTZ] is the concentration of BTZ, expressed in mg L−1; and [] and [] are the concentrations of and , respectively, both expressed in g L−1. Equation (2) has an R2 value of 84.1%, indicating that it can model almost all the variability in the experimental data. Table S3 shows the standard error for the coefficients of Equation (2), p-values, and confidence limits.

DRE (%) = 19.1391 − 0.000942955 × [BTZ] + 14.8174 × [NaCl] + 5.3951 × [Na2SO4] + 0.0000401872 × [BTZ]2 − 0.0120007 × [BTZ] × [NaCl]

The mathematical model in Equation (2) was used to estimate the EC50 (5 days). It is defined as the concentrations of BTZ, , and that produce a 50% inhibition of root elongation in Lactuca sativa seeds relative to the ultrapure water control. To this end, the DRE in Equation (2) was set equal to 50%, and the terms were rearranged, yielding Equation (3):

[Na2SO4] = (30.8609 + 0.000942955 × [BTZ] − 14.8174 × [NaCl] − 0.0000401872 × [BTZ]2 + 0.0120007 × [BTZ] × [NaCl])/5.39351

Equation (3) represents a surface whose points are all combinations of BTZ, , and concentrations that produce a 50% inhibition of root elongation in Lactuca sativa seeds relative to the ultrapure water control. If the concentrations of the compounds are set equal to zero two by two in Equation (3), the ecotoxicity of the third compound is obtained, expressed as EC50 (5 days): 888.1 mg L−1 for BTZ, 2.1 g L−1 for , and 5.7 g L−1 for . These values calculated with the mathematical model (Equation (3)) are of the same order of magnitude as those obtained by linear interpolation from the experimental data (Section 3.1). This fact demonstrates the goodness of the model.

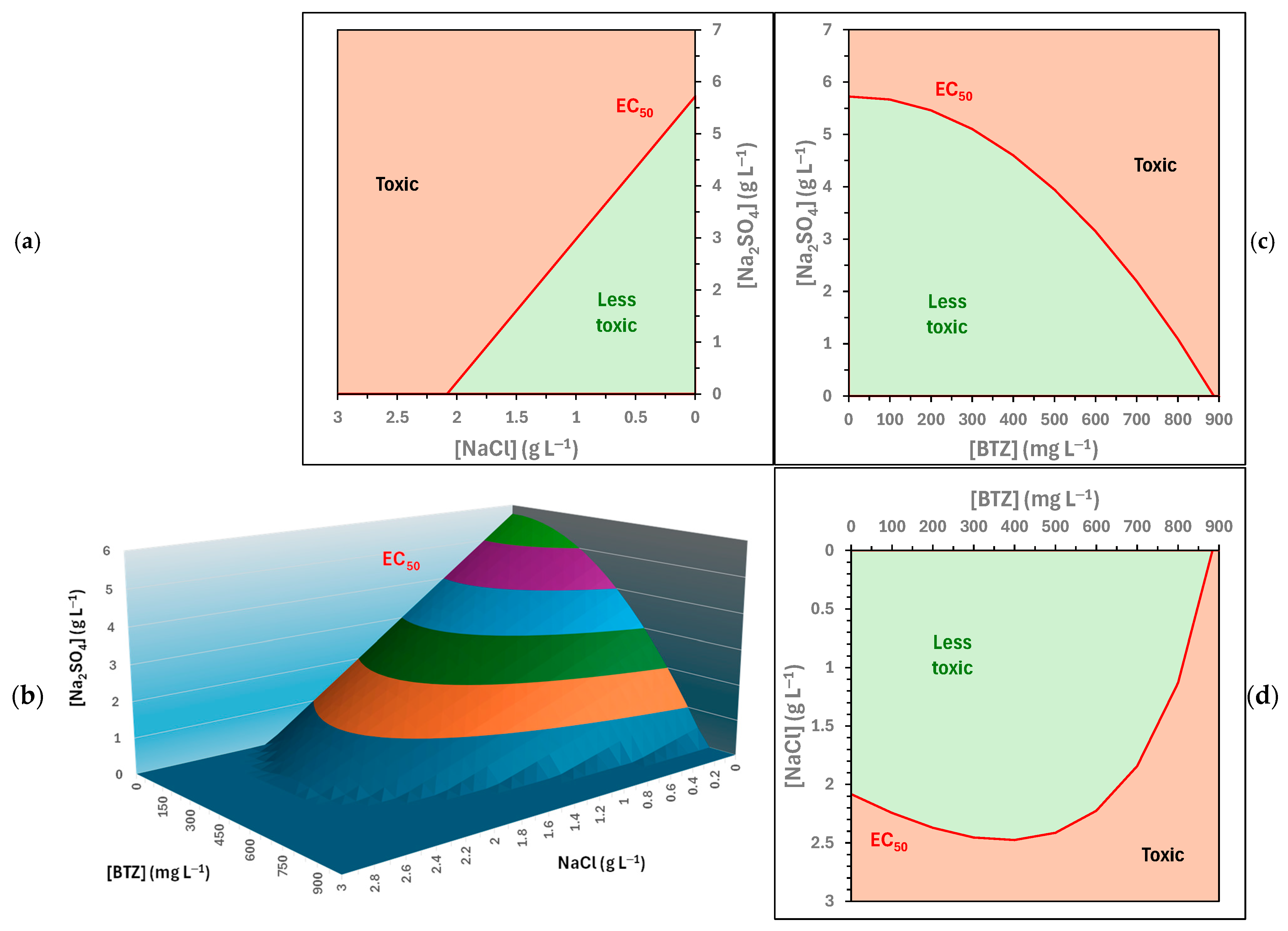

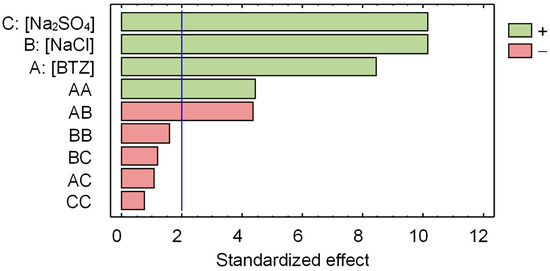

Figure 6 presents Equation (3) for positive values of the concentrations of the three compounds. All combinations of BTZ, , and concentrations above the three-dimensional surface represent toxic solutions towards Lactuca sativa. Figure 6 also shows the intersections between this surface and the Cartesian planes; the red lines represent the ecotoxicity thresholds for the substances in pairs.

Figure 6.

Predicted EC50 (5 days) values towards Lactuca sativa for solutions containing BTZ, , and . (b) Three-dimensional graph; (a,c,d) are intersections between this surface and the Cartesian planes.

The ecotoxicity threshold (EC50 (5 days)) towards Lactuca sativa for combinations of and (Figure 6b) exhibits a linear relationship with a negative slope. That is, a higher concentration of requires a lower concentration of for a sample to be considered toxic, and vice versa. Since the relationship is linear, it can be concluded that the two compounds have a simple and direct combined effect on ecotoxicity.

Regarding the ecotoxicity threshold (EC50 (5 days)) towards Lactuca sativa for combinations of and BTZ (Figure 6c), this exhibits a convex parabolic relationship. Therefore, when the BTZ concentration is low, higher concentrations of are required to reach toxic levels compared to a linear relationship. And, as the BTZ concentration increases, a progressively lower concentration of is required to cause toxic effects, with this decrease being smaller than if the relationship was linear. This behavior could be attributed to the fact that is a nutrient.

Finally, the ecotoxicity threshold (EC50 (5 days)) towards Lactuca sativa for combinations of and BTZ (Figure 6d) also shows a convex curve; but in this case, it exhibits an inflection point at a BTZ concentration equal to 381.7 mg L−1. This fact implies that, below 381.7 mg L−1, as the BTZ concentration increases, the concentration must also increase for the samples to be toxic. However, above 381.7 mg L−1, as the BTZ concentration increases, a lower concentration is required for the sample to be toxic, and vice versa. The behavior at low BTZ concentrations can be attributed to a possible hormetic effect of this herbicide. This fact was confirmed by ecotoxicity analysis (Figure 2a), since at low BTZ concentrations the root elongation of the seeds was greater than with the ultrapure water control.

Lastly, the three-dimensional graphical representation of the ecotoxicity thresholds (EC50 (5 days)) towards Lactuca sativa (Figure 6a) is not a plane, but a surface of greater complexity, as expected from its intersections with the Cartesian planes. In general, it is observed that the progressive increase in the concentrations of the three substances leads to an increase in the ecotoxicity of the system. Regarding the inflection point detected for BTZ combined with , it shifts towards lower concentrations of BTZ as the concentration increases.

3.4. Ecotoxicity of Solutions After Applying Electrooxidation and Photoelectrooxidation Processes

The second objective of this study is to analyze the efficacy in ecotoxicity reduction for electrooxidation and photoelectrooxidation processes using an Sb- ceramic anode coated with a photocatalyst.

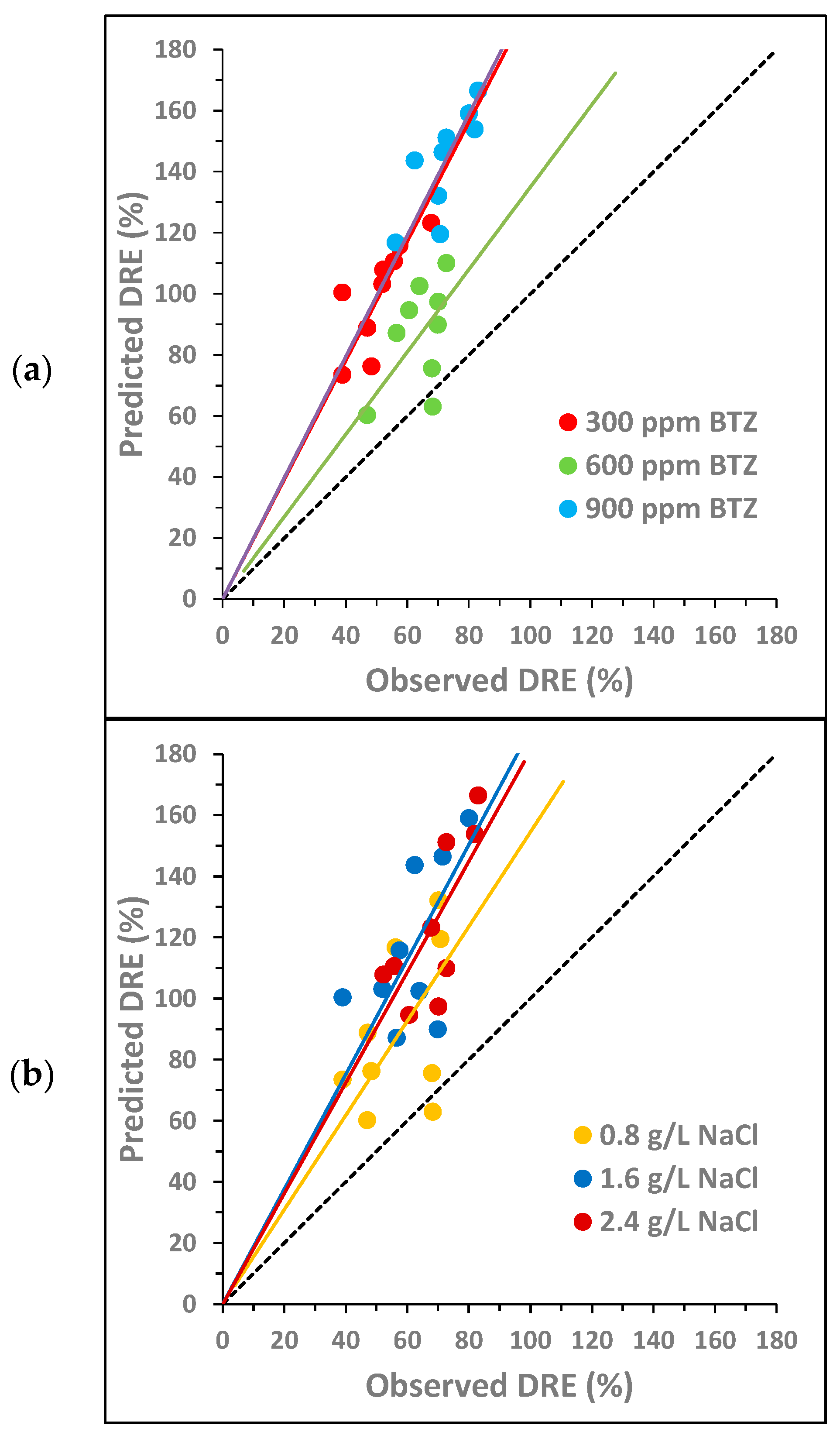

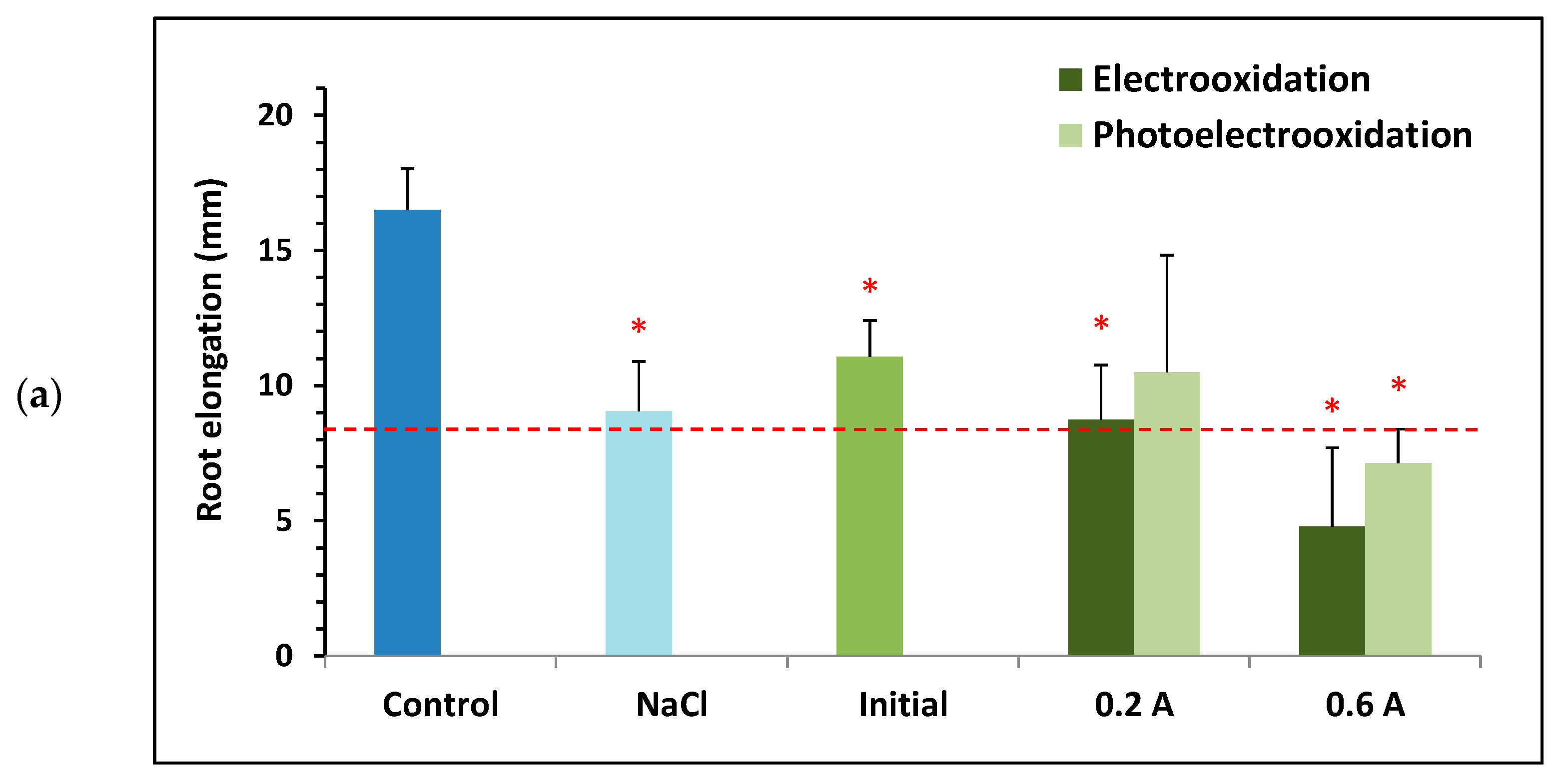

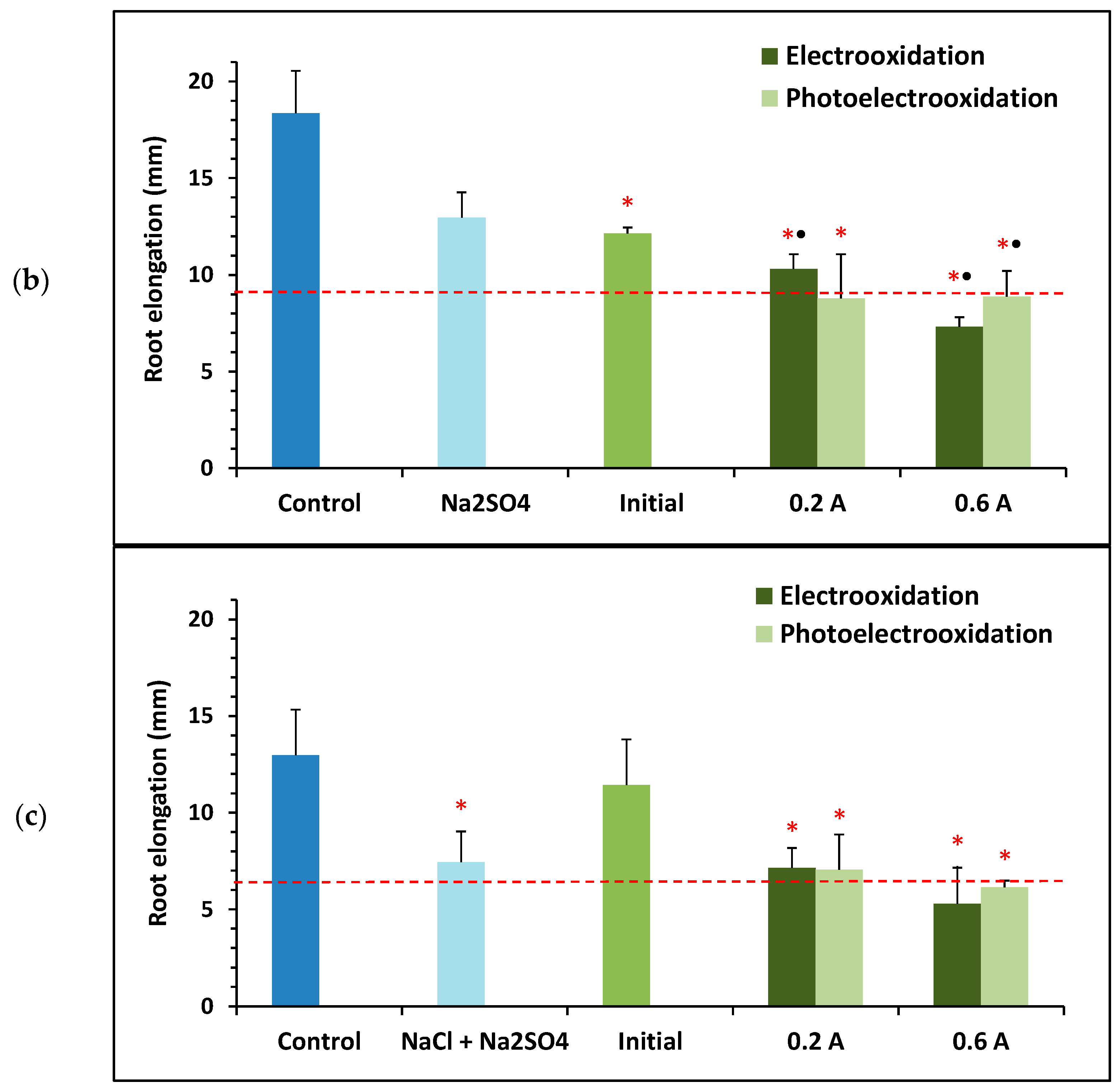

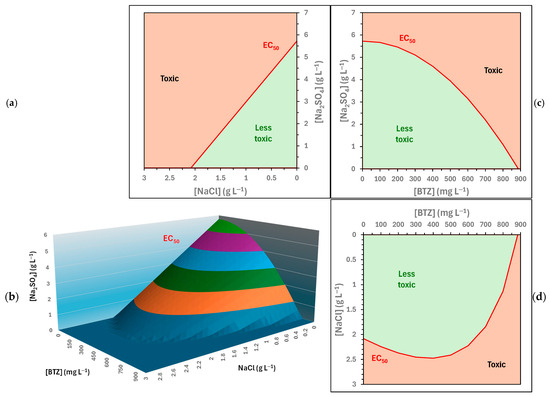

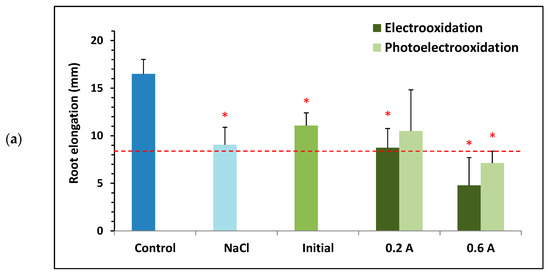

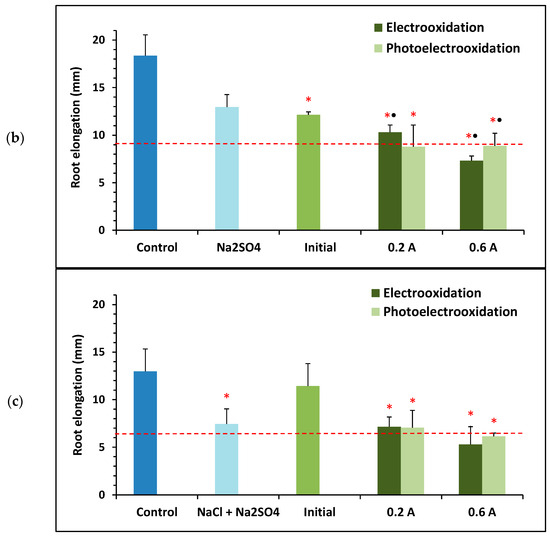

Figure 7 shows the mean root elongation results of Lactuca sativa seeds obtained for the initial BTZ sample and those treated under different operating conditions (green bars), that is, using different supporting electrolytes (, , and a mixture of both), applying current intensities of 0.2 and 0.6 A, and in the presence or absence of ultraviolet light provided by a lamp. Also shown is the root elongation of the seeds for the control sample corresponding to ultrapure water (dark blue bars) and for each of the supporting electrolytes tested (light blue bars). As in Figure 2, the error bars show the standard deviation of root elongation, and the red asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference from the control sample at a 95% confidence level. Figure 7 also includes a black dot when root elongation shows a statistically significant difference from the supporting electrolyte (in the absence of BTZ) at a 95% confidence level. Finally, the horizontal dashed red line marks 50% of the root elongation observed for the control sample. Therefore, samples with a mean root elongation below the red line and marked with an asterisk are considered toxic.

Figure 7.

Toxicity towards Lactuca sativa of solutions containing 100 mg L−1 of BTZ and different supporting electrolytes: (a) 1.65 g L−1 of , (b) 2 g L−1 of , (c) 0.46 g L−1 of , and 1.3 g L−1 of . Toxicity results before and after treatment with electrooxidation and photoelectrooxidation processes at two current intensities: 0.2 and 0.6 A. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three replicates; red asterisks and black points indicate statistically significant difference from the control (ultrapure water) and from the electrolyte, respectively, for a confidence level of 95%; and the red dashed line defines the threshold for determining if a sample is toxic.

Figure 7 shows that the control sample (ultrapure water) exhibits the greatest root elongation in all assays. Furthermore, none of the three initial samples are considered toxic, as predicted by the mathematical model obtained with the Statgraphics Plus 5.1 software (Figure 6). Regardless of the supporting electrolyte tested, all electrochemically treated samples show greater ecotoxicity than the untreated initial sample, although not all are considered toxic towards Lactuca sativa. Furthermore, in general, applying 0.6 A leads to a higher final toxicity than applying 0.2 A; and with the electrooxidation process, the final toxicity is higher than with the photoelectrooxidation process.

When analyzing each supporting electrolyte tested, Figure 7a shows that root elongation for the initial solution of 100 mg L−1 of BTZ and 1.65 g L−1 of is lower than that for the control (showing a statistically significant difference), but higher than that for the sample containing only . This is consistent with the hormetic effect of BTZ observed in previous sections, since at low concentrations of this herbicide greater root elongation is favored compared to its absence. When is used as the supporting electrolyte, the two samples treated at the highest current intensity (0.6 A) are considered toxic because they show root elongation below 50% of the control. Furthermore, for the two current intensities tested, when ultraviolet light is applied the samples are less toxic than if treated in the absence of light. In fact, the sample treated at 0.2 A by photoelectrooxidation is the least toxic of all, with root elongation very close to that of the initial sample. Finally, comparing the treated samples with the solution containing only , only those subjected to the highest current intensity (0.6 A) show greater toxicity, although the difference is not statistically significant.

Figure 7b shows that the initial sample containing 100 mg L−1 of BTZ and 2 g L−1 of showed less root elongation than the control (with a statistically significant difference), but similar to that of the sample containing only . At this concentration, the hormetic effect of BTZ does not appear to be observed. When is used as the supporting electrolyte, most of the electrochemically treated samples are toxic compared to the control. And compared with the solution containing only , all samples are found to be more toxic with a statistically significant difference.

Finally, Figure 7c shows that root elongation for the initial sample containing 100 mg L−1 of BTZ, 0.46 g L−1 of , and 1.3 g L−1 of is somewhat lower than that for the control but greater than root elongation for the sample containing only the supporting electrolyte. In this case, the presence of allows the hormetic effect of BTZ to be observed again. When using a mixture of and as the supporting electrolyte, only the samples treated at the highest current intensity of 0.6 A are toxic, as when using individually. Similarly, root elongation for these two samples is also lower than that for the sample containing only and , although the difference is not statistically significant.

In summary, whether the supporting electrolytes are tested individually or together, treatment with a lower current intensity and applying ultraviolet light appears to result in greater root elongation, i.e., the final samples are less toxic.

Table 1 shows the degradation and mineralization percentages achieved with each of the electrochemical tests after 4 h of treatment. It also shows ecotoxicity towards Vibrio fischeri determined with the Microtox equipment. The degradation degree refers to the disappearance of BTZ due to oxidation of this compound, forming other species. The mineralization degree refers to the disappearance of BTZ due to complete oxidation according to Equation (4) [40] and was determined by measuring total organic carbon (TOC). Based on these definitions, a percentage of mineralization lower than the degradation percentage implies that not all BTZ that has disappeared has undergone complete oxidation. That is, intermediate organic products have been formed.

Table 1.

Degradation degree and mineralization degree of solutions containing 100 mg L−1 of BTZ and different supporting electrolytes, treated by electrooxidation and photoelectrooxidation processes for 4 h, and the ecotoxicity towards Vibrio fischeri of these solutions.

For all experiments, Table 1 shows that the mineralization degree achieved is lower than the degradation degree. Therefore, intermediate organic products are formed. Among them, acetate and formate have been identified, but chlorinated organic compounds can also be formed by direct chlorination of BTZ [40]. The formation of these compounds could explain the increased toxicity of the treated samples compared to the initial solution (Figure 7). However, an analysis of the degradation and mineralization values in Table 1 shows that a higher percentage of degradation and mineralization does not always translate into lower final toxicity. When is used as the supporting electrolyte, on the one hand, the samples treated at 0.6 A show the highest degradation and mineralization values. However, as seen in Figure 7, they also show the highest toxicity towards Lactuca sativa, which is corroborated by the Microtox analysis. On the other hand, for the two current intensities tested, the application of ultraviolet light results in an increase in the degradation and mineralization percentages. However, according to the seed tests, in this case the toxicity of the final samples is lower. This behavior can be justified by considering the by-products formed during the electrochemical oxidation process. Comparing the two tests with a similar degradation percentage (0.6 A without light and 0.2 A with light), the one with the lower percentage of mineralization shows lower toxicity. This implies that the higher toxicity cannot be attributed to the organic intermediates formed since, if these were more toxic than BTZ, the sample with the lower percentage of mineralization should be more toxic, which is not the case. This fact suggests that during these treatments other by-products are generated that come from the oxidation of the supporting electrolyte (, in this case), such as chlorate ions [40], which contribute to the oxidation of BTZ but are more toxic than the starting chlorides. According to the literature, the EC50 (48 h) for Daphnia magna of sodium chlorate is 1.093 g L−1 (10.27 mmol L−1) [52] compared to 0.874 g L−1 (14.96 mmol L−1) for [45]. This would explain the increase in ecotoxicity at higher applied intensities, since a greater amount of chlorinated by-products would be formed, contributing at the same time to improved BTZ elimination. Regarding the application of ultraviolet light, it favors the photogeneration of reactive chlorinated species, such as ●Cl and ●HClO radicals [40]. These species are highly reactive with organic pollutants so they quickly disappear, contributing to BTZ degradation but without increasing toxicity.

In summary, the results suggest that electrochemical treatments of BTZ with at 0.6 A generally provide more toxic final effluents than applying 0.2 A and that the use of ultraviolet light in the process may have a mitigating effect on toxicity. Thus, the choice of the most favorable treatment should not depend solely on its efficiency, but also on the nature of the by-products generated as these can increase the final toxicity of the treated effluents.

When is used as the supporting electrolyte, when comparing the results obtained with Lactuca sativa with those of the Microtox assay (Table 1), some similarities are identified. The sample treated at 0.6 A without light shows moderate toxicity (5 TU), consistent with the reduced root elongation observed in Figure 7. The samples with zero toxicity (0.6 A with light and 0.2 A without light) correspond to those that show the greatest root elongation. It should be noted that for low toxicity values, the test with lettuce seeds is more sensitive than the Microtox assay. Therefore, lettuce seeds allow us to observe that the sample treated at 0.6 A with light presents greater toxicity than the sample treated at 0.2 A without light. Finally, the high toxicity observed with Microtox for the sample treated at 0.2 A with light is inconclusive, since in Figure 7 this sample shows one of the greatest root elongations.

Analyzing the degradation and mineralization percentages in Table 1 when working with as the supporting electrolyte, the samples treated at 0.6 A show the highest degradation and mineralization values. However, as seen in Figure 7, they also show the highest toxicity values with Lactuca sativa, as occurred when working with as the supporting electrolyte. Regarding the treatment carried out by applying light, greater degradation is observed for both current intensities and greater mineralization also occurs at 0.6 A. In the latter case, the higher degradation and mineralization percentages do not lead to greater toxicity, but quite the opposite (corroborated with both seeds and Microtox), as was observed when working with . This behavior can be justified by considering the by-products formed during the electrochemical oxidation process. In previous works it was verified that, when working with as the supporting electrolyte, persulfates are formed during the electrochemical process, which contribute to the indirect oxidation of the organic pollutant but increase the toxicity of the samples [49]. This is because the toxicity of sodium persulfate is higher than that of sodium sulfate. According to the literature, the EC50 (48 h) for Daphnia magna of sodium persulfate is 0.120 g L−1 (0.5 mmol L−1) [53] compared to 1.766 g L−1 (12.43 mmol L−1) of [46]. The formation of persulfates would explain the increase in ecotoxicity at higher applied intensities, since a greater amount of these by-products would be formed. Regarding the application of light, it can activate persulfates towards the formation of sulfate radicals (), which are highly oxidizing [40]. Therefore, as they disappear quickly, they contribute to the degradation of BTZ and its intermediate degradation products but do not increase toxicity.

In summary, as observed using as the supporting electrolyte, the results obtained with suggest that electrochemical treatments at 0.6 A generally provide more toxic final effluents than applying 0.2 A. Moreover, the use of ultraviolet light in the process may have a mitigating effect on toxicity.

Finally, when a mixture of and is used as the supporting electrolyte, comparing the results obtained with Lactuca sativa with those of the Microtox assay (Table 1), no clear trends are observed. This could be attributed to the fact that the toxicity values detected are low and, as indicated above, the test with lettuce seeds is more sensitive for low toxicity values, allowing differences to be observed that are not appreciated with Microtox.

Analyzing the degradation and mineralization percentages in Table 1, the samples treated at 0.6 A exhibit the highest degradation and mineralization values. However, as seen in Figure 7, they also exhibit the highest toxicity values with Lactuca sativa. Regarding the application of light during treatment, greater degradation and mineralization are achieved for both current intensities. However, in this case, the toxicity is lower than or of the same order of magnitude as in the absence of light, according to the seed tests. These trends are generally the same as those observed when working with or separately, and the same explanation regarding the formation of by-products from the two compounds used as supporting electrolytes is valid.

The results obtained with the mixed electrolyte for BTZ show intermediate degradation and mineralization values between those achieved with the two pure electrolytes; applying 0.6 A, they are very close to the maximum values achieved with pure . Furthermore, for this current intensity, the toxicity of the final effluents achieved with the mixed electrolyte is significantly lower than working with pure , especially when light is applied, since in this case root elongation is very close to 50% of the control. Therefore, working with the mixed electrolyte has shown that the results for BTZ from the combined perspective of final degradation/mineralization and toxicity, are better, in addition to more closely resembling the conditions found in the Albufera lake.

In summary, the photoelectrooxidation process applying 0.6 A with the mixed electrolyte is the most effective technique from the combined point of view of final degradation (90.9%), mineralization (62.4%), and toxicity. Moreover, the degradation degree achieved is greater than 80%, which is the minimum value required by Directive (EU) 2024/3019 to reduce the concentration of micropollutants [3]. Therefore, the photoelectrooxidation could be used as a quaternary treatment in WWTPs with the following additional advantages. This technique does not need the addition of chemical additives, and energy consumption could be supplied by alternative energy sources, especially in small communities [54].

4. Conclusions

BTZ is an herbicide detected as a micropollutant in the Albufera Natural Park. The study of the ecotoxicity of BTZ towards Lactuca sativa shows a hormetic effect. At low concentrations of BTZ, an increase in herbicide concentration can stimulate root growth of the seeds (reaching a maximum at 100 mg L−1). However, at higher concentrations, an increase in the BTZ concentration causes a decrease in root elongation. The ecotoxicity value of BTZ towards Lactuca sativa is 900 mg L−1, expressed as EC50 (5 days). The study of the herbicide ecotoxicity in the presence of and shows, in general, an antagonistic effect between these substances, both in pairs and jointly. The antagonistic effect is lower at the BTZ intermediate concentration of 600 mg L−1, the lowest concentration, and at the highest concentrations. However, a possible synergistic behavior is observed at 600 mg L−1 of BTZ in the presence of 2.8 g L−1 of and 0.8 g L−1 of . Statistical analysis shows that the concentrations of the three compounds have a statistically significant positive effect on the decrease in root elongation (DRE). The effect of the concentrations of and has the same significance on the DRE, and this is greater than the effect of the BTZ concentration. Finally, a mathematical model has been obtained for the set of BTZ, , and that predicts whether a combination of these three compounds’ concentrations is ecotoxic towards Lactuca sativa. In general, when the concentration of one compound increases, a lower concentration of the others is necessary for the mixture to be toxic. However, in the presence of , below 382 mg L−1 of BTZ, the concentrations of both compounds need to be increased. This is attributable to the hormetic behavior of BTZ. This BTZ concentration value decreases as the concentration increases.

Regarding the second objective of this study, the treatment of effluents containing BTZ by electrooxidation and photoelectrooxidation processes using a Sb- ceramic anode coated with a photocatalyst has shown good results. The choice of the most favorable operating conditions should not depend solely on efficiency, but also on the nature of the by-products generated. This is because they can increase the final toxicity of the treated effluents. Regardless of the supporting electrolyte tested (, , or a mixture of both), all electrochemically treated samples showed greater ecotoxicity than the untreated initial sample. However, not all were considered toxic towards Lactuca sativa. In general, applying a current intensity of 0.6 A resulted in higher final toxicity than applying 0.2 A; with the electrooxidation process, the final toxicity was higher than that obtained with the photoelectrooxidation process. The results obtained with the mixed electrolyte for the BTZ showed intermediate degradation and mineralization values between those achieved with the two pure electrolytes. Moreover, applying 0.6 A, they are very close to the maximum values achieved with pure . Furthermore, for 0.6 A, the toxicity of the final effluents achieved with the mixed electrolyte is significantly lower than working with pure , especially when light is applied. Taking into account the limitations of this study, the photoelectrooxidation process applying 0.6 A with the mixed electrolyte (0.46 g L−1 of and 1.3 g L−1 of ) is the most effective technique from the combined point of view of final degradation (90.9%), mineralization (62.4%), and toxicity, in addition to more closely resembling the conditions found in the Albufera lake. The degradation degree achieved is greater than the 80% required by Directive (EU) 2024/3019 to eliminate micropollutants. Therefore, the photoelectrooxidation could be used as a quaternary treatment in WWTPs with the following additional advantages. This technique does not need the addition of chemical additives, and energy consumption could be supplied by alternative energy sources, especially in small communities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/environments13010008/s1, Table S1: Average root elongation of Lactuca sativa seeds for the samples from the experimental design described in Section 2.1. Calculation of the observed decrease in root elongation (DRE) and the predicted DRE; Table S2: ANOVA table for the effect of BTZ, NaCl and Na2SO4 concentrations (factors A, B and C, respectively) and their interactions on the experimental decrease in root elongation (DRE); Table S3: Statistical parameters for the coefficients of Equation (2).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T.M.S. and M.G.G.; methodology, M.T.M.S. and M.G.G.; validation, T.G.A. and M.T.M.S.; formal analysis, T.G.A. and M.T.M.S.; investigation, T.G.A. and C.D.T.; resources, V.P.H.; writing—original draft preparation, T.G.A. and M.T.M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.T.M.S., M.G.G. and V.P.H.; visualization, T.G.A. and M.T.M.S.; supervision, M.T.M.S.; funding acquisition, V.P.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study forms part of the ThinkInAzul program and was supported by MCIN with funding from the European Union NextGenerationEU (PRTR-C17.I1) and by Generalitat Valenciana (GVA-THINKINAZUL/2021/013; principal investigators: Valentín Pérez Herranz and Maria Teresa Montañés Sanjuan, Universitat Politècnica de València).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AOP | Advanced oxidation process |

| BTZ | Bentazone |

| DRE | Decrease in root elongation |

| WWTP | Wastewater treatment plant |

References

- Hussien, W.A.; Memon, F.A.; Savic, D.A. Assessing and Modelling the Influence of Household Characteristics on Per Capita Water Consumption. Water Resour. Manag. 2016, 30, 2931–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voukkali, I.; Papamichael, I.; Loizia, P.; Zorpas, A.A. Urbanization and Solid Waste Production: Prospects and Challenges. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 17678–17689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU) 2024/3019 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2024 concerning urban wastewater treatment. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/3019/oj/eng (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- INE. Destino de Las Aguas Residuales Tratadas Por Comunidades y Ciudades Autónomas, Lugar de Destino y Periodo. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?path=/t26/p067/p01/serie/l0/&file=01006.px (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- INE. Usos Del Agua Reutilizada Por Comunidades y Ciudades Autónomas, Tipo de Uso y Periodo. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?path=/t26/p067/p01/serie/l0/&file=01007.px (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- The List of Wetlands of International Importance. Available online: https://www.ramsar.org/sites/default/files/documents/library/sitelist.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- GVA. PN L’Albufera. Available online: https://parquesnaturales.gva.es/es/web/pn-l-albufera/conocenos (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Calvo, S.; Romo, S.; Soria, J.; Picó, Y. Pesticide Contamination in Water and Sediment of the Aquatic Systems of the Natural Park of the Albufera of Valencia (Spain) during the Rice Cultivation Period. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 145009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Megías, C.; Mentzel, S.; Fuentes-Edfuf, Y.; Moe, S.J.; Rico, A. Influence of Climate Change and Pesticide Use Practices on the Ecological Risks of Pesticides in a Protected Mediterranean Wetland: A Bayesian Network Approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 878, 163018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CymitQuimica. Available online: https://cymitquimica.com/es/cas/25057-89-0/ (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Cho, B.; Kim, S.; In, S.; Choe, S. Simultaneous Determination of Bentazone and Its Metabolites in Postmortem Whole Blood Using Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Forensic Sci. Int. 2017, 278, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, I.B.; Petersen, H.W.; Johansen, S.S.; Theilade, P. Fatal Overdose of the Herbicide Bentazone. Forensic Sci. Int. 2003, 135, 235–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, M.; Jonidi-Jafari, A.; Farzadkia, M.; Esrafili, A.; Godini, K.; Shirzad-Siboni, M. Photocatalytic Removal of Bentazon by Copper Doped Zinc Oxide Nanorods: Reaction Pathways and Toxicity Studies. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 294, 112962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, D.C.; Noldin, J.A.; Deschamps, F.C.; Resgalla, C. Ecological Risk Analysis of Pesticides Used on Irrigated Rice Crops in Southern Brazil. Chemosphere 2016, 162, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberle, A.N.A.; Alves, M.E.P.; da Silva, S.W.; Klauck, C.R.; Rodrigues, M.A.S.; Bernardes, A.M. Phytotoxicity and Genotoxicity Evaluation of 2,4,6-Tribromophenol Solution Treated by UV-Based Oxidation Processes. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 249, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Carolis, C.; Iori, V.; Narciso, A.; Gentile, D.; Casentini, B.; Pietrini, F.; Grenni, P.; Barra Caracciolo, A.; Iannelli, M.A. The Effects of Different Combinations of Cattle Organic Soil Amendments and Copper on Lettuce (Cv. Rufus) Plant Growth. Environments 2024, 11, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priac, A.; Badot, P.M.; Crini, G. Treated Wastewater Phytotoxicity Assessment Using Lactuca Sativa: Focus on Germination and Root Elongation Test Parameters. Comptes Rendus Biol. 2017, 340, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, R.Y.; Manikandan, S.; Subbaiya, R.; Biruntha, M.; Govarthanan, M.; Karmegam, N. Removal of Emerging Micropollutants Originating from Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) in Water and Wastewater by Advanced Oxidation Processes: A Review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 23, 101757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Huitle, C.A.; Hernandez, F.; Ferro, S.; Antonio, M.; Alfaro, Q.; De Battisti, A. Electrochemical Oxidation: An Alternative for the Wastewater Treatment with Organic Pollutants Agents. Afinidad 2006, 63, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Karim, A.V.; Nidheesh, P.V.; Oturan, M.A. Boron-Doped Diamond Electrodes for the Mineralization of Organic Pollutants in the Real Wastewater. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2021, 30, 100855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Gomez, J.; Ortega, E.; Mestre, S.; Pérez-Herranz, V.; García-Gabaldón, M. Electrochemical Degradation of Norfloxacin Using BDD and New Sb-Doped SnO2 Ceramic Anodes in an Electrochemical Reactor in the Presence and Absence of a Cation-Exchange Membrane. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 208, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Gómez, J.; García-Gabaldón, M.; Carrillo-Abad, J.; Montañés, M.T.; Mestre, S.; Pérez-Herranz, V. Influence of the Reactor Configuration and the Supporting Electrolyte Concentration on the Electrochemical Oxidation of Atenolol Using BDD and SnO2 Ceramic Electrodes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 241, 116684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Gómez, J.; Escribá-Jiménez, S.; Carrillo-Abad, J.; García-Gabaldón, M.; Montañés, M.T.; Mestre, S.; Pérez-Herranz, V. Study of the Chlorfenvinphos Pesticide Removal under Different Anodic Materials and Different Reactor Configuration. Chemosphere 2022, 290, 133294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balseviciute, A.; Martí-Calatayud, M.C.; Pérez-Herranz, V.; Mestre, S.; García-Gabaldón, M. Novel Sb-Doped SnO2 Ceramic Anode Coated with a Photoactive BiPO4 Layer for the Photoelectrochemical Degradation of an Emerging Pollutant. Chemosphere 2023, 335, 139173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, G.T.; Giacobbo, A.; dos Santos Chiaramonte, E.A.; Rodrigues, M.A.S.; Meneguzzi, A.; Bernardes, A.M. The Effect of Sanitary Landfill Leachate Aging on the Biological Treatment and Assessment of Photoelectrooxidation as a Pre-Treatment Process. Waste Manag. 2015, 36, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Casas, M.P.; Pérez-Herranz, V.; Giner-Sanz, J.J.; Mestre, S.; García-Gabaldón, M. Statistical Comparison of the Photoelectrochemical Degradation of an Antibiotic Pollutant Using Two Sb-Doped SnO2 Ceramic Anodes Coated with Photoactive CdFe2O4 and ZnFe2O4 Layers. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 360, 130954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carena, L.; Fabbri, D.; Passananti, M.; Minella, M.; Pazzi, M.; Vione, D. The Role of Direct Photolysis in the Photodegradation of the Herbicide Bentazone in Natural Surface Waters. Chemosphere 2020, 246, 125705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Z.; Wei, J.; Tan, H.; Li, X. Hydrolysis and Photolysis of Bentazone in Aqueous Abiotic Solutions and Identification of Its Degradation Products Using Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 10127–10135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berberidou, C.; Kitsiou, V.; Kazala, E.; Lambropoulou, D.A.; Kouras, A.; Kosma, C.I.; Albanis, T.A.; Poulios, I. Study of the Decomposition and Detoxification of the Herbicide Bentazon by Heterogeneous Photocatalysis: Kinetics, Intermediates and Transformation Pathways. Appl. Catal. B 2017, 200, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, N.A.; Haque, M.M.; Khan, A.; Muneer, M.; Vijayalakshmi, S. Photocatalytic Degradation of Herbicide Bentazone in Aqueous Suspension of TiO2: Mineralization, Identification of Intermediates and Reaction Pathways. Environ. Technol. 2014, 35, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, M.V.; Rosa, M.F.; Lobo, V.d.S.; Bariccatti, R.A. Degradação Fotocalítica de Bentazona Com TiO2. Eng. Sanit. Ambient. 2014, 19, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessegato, G.G.; Santos, V.P.; Lindino, C.A. Degradação Fotoeletroquímica Do Herbicida Bentazona Sobre Eletrodos de Carbono Modificados Por TiO2. Quim. Nova 2012, 35, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IZONASH GVA. Programa de Seguimiento de Zonas Húmedas—Espacios Naturales Protegidos—Generalitat Valenciana. Available online: https://mediambient.gva.es/es/web/espacios-naturales-protegidos/programa-de-seguimiento-de-zonas-humedas (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Bureš, M.S.; Ukić, Š.; Cvetnić, M.; Prevarić, V.; Markić, M.; Rogošić, M.; Kušić, H.; Bolanča, T. Toxicity of Binary Mixtures of Pesticides and Pharmaceuticals toward Vibrio Fischeri: Assessment by Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 275, 115885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montañés, M.T.; García-Gabaldón, M.; Roca-Pérez, L.; Giner-Sanz, J.J.; Mora-Gómez, J.; Pérez-Herranz, V. Analysis of Norfloxacin Ecotoxicity and the Relation with Its Degradation by Means of Electrochemical Oxidation Using Different Anodes. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 188, 109923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D1193-06; Standard Specification for Reagent Water. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- Wassertein, R.L. Declaración de La ASA Sobre La Significancia Estadística y Los P-Valores. Available online: https://soce.iec.cat/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/efba1672f6161e2bbedc6acf6a6f8d45.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Thiese, M.S.; Ronna, B.; Ott, U. P Value Interpretations and Considerations. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, E928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukić, S.; Sigurnjak, M.; Cvetnić, M.; Markić, M.; Stankov, M.N.; Rogošić, M.; Rasulev, B.; Lončarić Božić, A.; Kušić, H.; Bolanča, T. Toxicity of Pharmaceuticals in Binary Mixtures: Assessment by Additive and Non-Additive Toxicity Models. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 185, 109696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo-Torner, C.; Pérez-Herranz, V.; Mestre, S.; García-Gabaldón, M. Electrolyte Influence on Light-Assisted Electrooxidation of an Herbicide Employing an Sb-SnO2 Electrode Coated with a Bi2WO6 Photocatalyst. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 366, 132859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA OPPTS 850.4200; Terrestrial Plant Toxicity, Tier I (Seedling Emergence). United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1996.

- Duke, S.O.; Belz, R.G.; Carbonari, C.A.; Velini, E.D. Understanding Herbicide Hormesis: Evaluating Its Positive and Negative Aspects with Emphasis on Glyphosate. Adv. Weed Sci. 2025, 43, e020250104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimouri Jervekani, M.; Karimmojeni, H.; Razmjo, J.; Tseng, T.M. Common Sage (Salvia officinalis L.) Tolerance to Herbicides. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 121, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna-Fernandes, A.F.; Marin, E.B.; Penha, T.H.F.L. Application of Root Growth Endpoint in Toxicity Tests with Lettuce (Lactuca Sativa). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Contam. 2016, 11, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigma-Aldrich. Safety Data Sheet Sodium Chloride. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/ES/en/sds/sigald/s9888?userType=undefined (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Sigma-Aldrich. Safety Data Sheet Sodium Sulfate. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/ES/en/sds/sigald/793531?userType=undefined (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Ahmed, A.; Knoble, C.; Schuler, M.S. Effects of Pesticides and Road Salt on Freshwater Quality and Nutrient Dynamics: A Review. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 382, 126787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankaji, I.; Sleimi, N.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Pérez-Clemente, R.M. NaCl Protects against Cd and Cu-Induced Toxicity in the Halophyte Atriplex Halimus. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2016, 14, e0810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montañés, M.T.; García-Gabaldón, M.; Giner-Sanz, J.J.; Mora-Gómez, J.; Pérez-Herranz, V. Effect of the Anode Material, Applied Current and Reactor Configuration on the Atenolol Toxicity during an Electrooxidation Process. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mera, R.; Torres, E.; Abalde, J. Isobolographic Analysis of the Interaction between Cadmium (II) and Sodium Sulphate: Toxicological Consequences. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 2264–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soucek, D.J. Comparison of Hardness- and Chloride-regulated Acute Effects of Sodium Sulfate on Two Freshwater Crustaceans. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2007, 26, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SupelCo. Safety Data Sheet Sodium Chlorate. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/ES/en/sds/mm/1.06420?userType=anonymous (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Sigma-Aldrich. Safety Data Sheet Sodium Persulfate. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/ES/en/sds/sigma/71889?userType=undefined (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Marmanis, D.; Emmanouil, C.; Fantidis, J.G.; Thysiadou, A.; Marmani, K. Description of a Fe/Al Electrocoagulation Method Powered by a Photovoltaic System, for the (Pre-)Treatment of Municipal Wastewater of a Small Community in Northern Greece. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.