Abstract

Microplastic pollution of ecosystems is considered a modern problem. Freshwater ecosystems, despite the interest shown in their study, remain poorly understood. Lake Baikal (Russia) is one of the least studied freshwater ecosystems in this regard. This large lake is distinguished from others by its high level of biodiversity and clean drinking water. The aim of this study is a multi-matrix investigation of microplastic pollution in one of the lake’s bay. The following matrices are used: surface water, water column, sediment, macrophytes, macroinvertebrates, and fish, as well as ice and snow during the winter. The results show that certain locations exhibit high concentrations of microplastic particles. In some cases, this was due to the properties or characteristics of these locations (littoral zones near the water’s edge, macrophytes with mucus sheaths, ice and snow (potentially, the near-surface water layer after ice melt)), while in others, it was due to localized pollution (pier and ship mooring areas). An analysis of the polymer types of the detected microplastic particles reveals the presence of both common (polypropylene, polyethylene terephthalate, polystyrene, polyethylene, polyvinyl chloride) and rare (polyvinyl alcohol and alkyd resin). Moreover, in some locations, the latter two polymers predominate, a phenomenon rarely observed in other studies. Further research was recommended to focus on the chronic effects of microplastic particles on organisms associated with areas of elevated particle concentrations.

1. Introduction

In the classical sense, microplastics are microparticles of artificial polymers with a size from 300 µm to 5 mm [1,2]. This lower limit was determined by the use of hydrobiological tools (plankton and neuston nets) with corresponding mesh sizes [1,2]. However, a number of studies have emerged recently showing that the number of particles below this limit is many times greater than the amount typically detected [3]. This serves as evidence that both field work and laboratory experiments require lowering the lower limit of detectable plastic particles. Moreover, the modern size classification of plastic particles is as follows: >5 mm—macroplastic, from 1 µm to 5 mm—microplastic, from 1 nm to 1 µm—nanoplastic. It is worth noting that, based on their morphological structure, the particles themselves are divided into a number of types: foam, granules, films, fibers, and fragments [4]. The most common are fragments (formed as a result of the physical degradation of plastic waste) and fibers (resulting from washing clothes) [1,2,5,6].

Nowadays, microplastic particles can be found everywhere, even in remote areas [1,2,7,8,9,10]. However, the problem of pollution of aquatic ecosystems with microplastic particles was first raised just over 50 years ago [11,12]. The main focus has been on the pollution of marine ecosystems by microplastic particles [4,13,14], or more precisely, even individual parts of them—the near-surface water layer (and, accordingly, experiments have begun to be conducted on the effect of microplastics on planktonic and pelagic organisms) [15]. However, over time, it became clear that freshwater bodies are even more susceptible to microplastic pollution, since they are much more closely related to urbanized areas, unlike marine ecosystems [16]. In addition, it has become obvious that microplastics settle over time and their concentration must be assessed not only at the surface of a reservoir, but also at different horizons, with the final place of accumulation of microplastic particles being the bottom sediments [10,14,17,18].

Currently, the vast majority of experiments assessing the impact of microplastics on living organisms significantly overestimate their concentrations compared to those found in natural environments. However, reports have begun to emerge describing ecologically significant concentrations of microplastics in the wild, which may already be affecting resident organisms [18]. Therefore, studies that simultaneously analyze microplastic concentrations in both environmental samples and living organisms are of particular interest [10,19].

Regarding the impact of microplastics on living organisms, at present, a considerable amount of periodically contradictory and ambiguous information exists. This can be interpreted as the fact that the impact of plastic particles depends on their morphological shape, size, type of polymer and is species-specific [5,6,20,21]. To date, microplastics have been detected in natural environments in many organisms, from zooplankton to aquatic mammals [10,19], with most research still focusing on marine organisms [4,22]. Microplastic particles are transferred through the food chain [10,16,18,19], with organisms at higher levels consequently harboring higher numbers of particles. Moreover, in the same ecosystems, for example, bottom-dwelling fish are found to have a greater number of particles than pelagic fish [23], which confirms that plastics tend to accumulate in bottom sediments and enter the food web.

Microplastics are also consumed by herbivores [22], which can be facilitated by their adsorption onto aquatic plants [23]. Microplastics adsorbed onto macrophytes are subsequently consumed by mollusks. It is worth noting that mollusks and crustaceans (in particular, amphipods) are currently the most convenient and frequently used organisms both in studying microplastic consumption in natural settings and as model organisms for microplastic experiments [18,24,25,26]. In fact, the ability of microplastics to be adsorbed on plants is in itself capable of influencing these plants, both phytoplankton and macroalgae [21,23], and higher aquatic plants [27], where an obstruction of photosynthesis and a reduction in root length are observed (while everything, apparently, will again depend on both the morphology and size of the particles, and on the specific species). Microplastics can also be adsorbed onto the underside of ice [9,28], which can be an additional habitat for many species of animals and plants [29].

The first studies of microplastic pollution in Lake Baikal (Russia) began only in 2015 [30,31], with some work conducted in 2016 [32], and the first published data only appeared in 2020 [33]. Until now, studies conducted on Lake Baikal have been unsystematic, sporadic, and primarily conducted during the summer months [30,31,32,33,34]. Only one preliminary study has examined microplastic pollution of the lake during the winter season [28]. Several other studies have assessed microplastic contamination within the lake’s watershed [2,33,35]. These studies show that fibers are the most common type of microplastic particle in the lake, with fragments being the second most common [30,31,32,33], while the amount of microplastic particles is significant and comparable to that found in the North American Great Lakes [1,32]. It is worth noting that almost all of the studies cited relate exclusively to the collection and analysis of samples in the surface water layer [28,30,31,32,33].

There is even less data on the ingestion of microplastics by living organisms. There is evidence of microplastics in the Baikal planktonic crustacean Epischura baicalensis Sars, 1900 [36], as well as data on the incorporation of large quantities of microplastic particles into the cases of caddisfly larvae [37]. Experimental conditions have confirmed the ability of gastropods from Lake Baikal to consume microplastics of various morphological structures [38].

Thus, to summarize all of the above, we see a lack of data on microplastic pollution in Lake Baikal across many topics. Given the lake’s size and unique biodiversity, the aim of our study is to assess microplastic pollution in one of the lake’s bay using multiple matrices. We decide to use as matrices: (1) the near-surface water layer at different distances from the shoreline, (2) different layers in the water column, (3) sediments, (4) macrophytes, (5) gastropods, amphipods and fish; and in addition, (6) the underside of the ice in winter and (7) snow cover on top of the ice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Lake Baikal is a large continental lake. It contains 20% of the world’s fresh drinking water. The lake is located in the southern part of Eastern Siberia (Russia), between the Irkutsk region and the Republic of Buryatia. The lake is home to over 2500 animals and plants, approximately two-thirds of which are endemic.

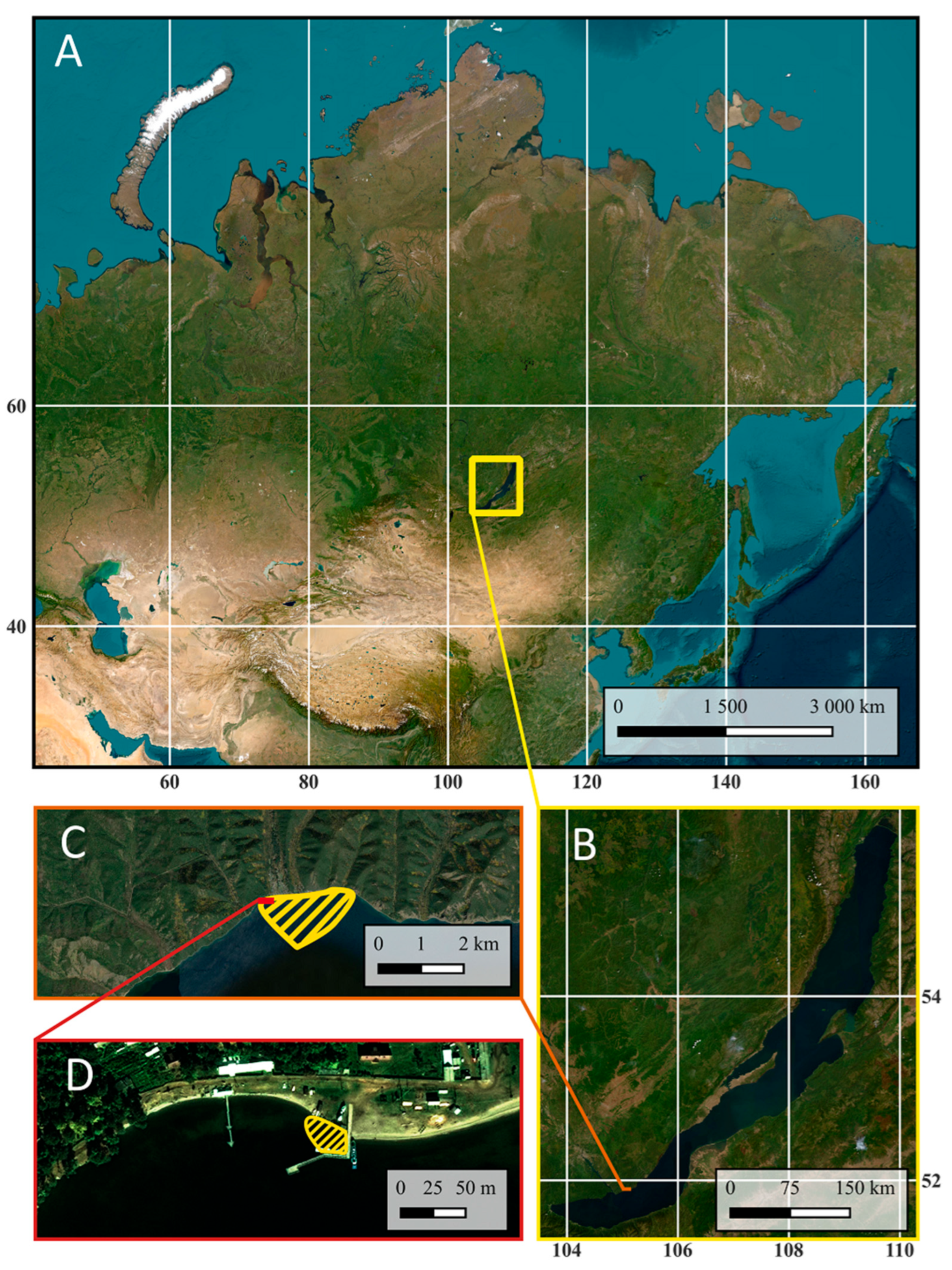

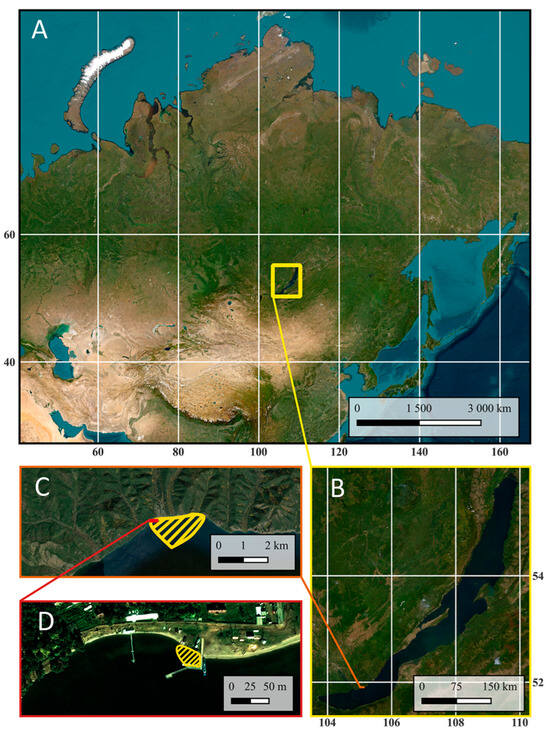

Bolshie Koty Bay is located in the southern part of Lake Baikal in Irkutsk region (Figure 1). The distance to the opposite shore is approximately 40 km, and the distance to the southern end of the lake is approximately 90 km. A pier and ship mooring are located deep within the bay. The bay and the village of the same name are difficult to access. There is no road to the village; access is by water (or across ice in winter) or on foot along a hiking trail.

Figure 1.

Location of Lake Baikal and Bolshie Koty Bay: (A)—general plan, (B)—Lake Baikal, (C)—Bolshie Koty Bay (the study area is highlighted with shading), (D)—pier and ship mooring area in Bolshie Koty Bay (the study area is highlighted with shading) (an ESRI satellite was used as a baseline).

2.2. Sampling in Winter

Snow samples were collected from the ice surface, as well as samples of ice and aquatic organisms living near the ice-water interface. Sampling took place in late February 2024. For sampling, ice was cut along a transect at six locations (in Bolshie Koty Bay, Southern Baikal) ranging in distance from the shore (Table 1). Three ice samples were collected at each location (ice was taken from the bottom 20 cm of the ice layer). In addition, snow samples were collected from the ice surface at the first three locations (at least three samples at each location).

Table 1.

Characteristics of ice, snow and aquatic organism sampling sites.

At all sites, after ice and snow sampling, at least three aquatic organism samples were collected using a Juday plankton net (UfaPribor, Ufa, Russia) (mesh size 100 µm). This was done to identify the aquatic organism community associated with the lower ice layer and, therefore, most susceptible to the potential impact of microplastics.

After collection, ice and snow samples were melted indoors at room temperature, filtered using a mesh sieve (100 µm), and concentrated. The volume of filtered water was measured using a graduated cylinder. Samples collected with the Juday net were fixed in a 4% formalin solution.

2.3. Sampling in Summer

Samples were collected in the near-surface water layer and at various depths in Bolshie Koty Bay, including bottom sediment sampling, macrophyte sampling, macroinvertebrate sampling (amphipods and mollusks), and fish. Additionally, we collected bottom sediment samples in the pier and ship mooring area, as well as samples from the near-surface water layer (under wave and calm conditions), and qualitatively assessed the biodiversity in this area. Sampling was conducted in August 2024.

2.3.1. Sampling in the Surface Layer of Water and at Various Depths, as Well as Sampling of Sediments

Samples over the littoral and pelagic zones were collected in summer using a neuston net with an entrance area of 0.1 m2 (100 μm). This sampling was carried out in several replicates (at least 3) along the transect with increasing distance from the shore (starting from the water’s edge and ending at a distance of 1 km). The trawling length at the water’s edge was 10 m, above the pelagic zone 200 m. There were 5 locations in total, which differed in their distance from the coastline: 1. at the water’s edge along the shore; 2. at a distance of 70–200 m along the shore; 3. at a distance of 360–510 m along the shore; 4. at a distance of 600–700 m along the shore; 5. at a distance of 900–1000 m along the shore.

Sampling at different depths (in different layers of the pelagic zone) of Lake Baikal was carried out at a point with coordinates: 51°52′44.5′′ N 105°04′52.8′′ E. This sampling was carried out using a Juday closing net (inlet diameter 37.5 cm, 100 µm) in the following layers: 0–5, 5–10, 10–25, 25–50, 50–100 m.

Bottom sediment samples were collected at points with coordinates: 51°54′10.9′′ N 105°06′12.8′′ E (near the Varnachka area) and 51°54′11.6′′ N 105°04′12.1′′ E (directly near Bolshie Koty settlement). The depth at the sampling site was 0.5 m, and three samples were collected in total. These samples were collected using a manual bottom grab. After collection, the sediment samples were placed in a glass container.

2.3.2. Sampling of Macrophytes, Macroinvertebrates and Fish

Macrophyte samples (at least three samples of each species) were collected to study the adsorption of microplastic particles on plants in natural conditions. A total of six species were sampled: Elodea canadensis Michx., Draparnaldioides baicalensis (K.I. Meyer) Vishnyakov, Ulothrix zonata (F. Weber et Mohr) Kützing, Stuckenia sp., Myriophyllum spicatum L., and Bryophyta (from partially submerged rocks near the shore). Plant samples were cut directly in the water and carefully transferred to a glass container without removing them from the water. Near the shore (E. canadensis, U. zonata, Bryophyta), this was done by entering the water in boots, at a depth of 2–3 m (D. baicalensis, Stuckenia sp., M. spicatum) with the help of divers.

In addition to macrophytes, individuals of five amphipod species (Eulimnogammarus cyaneus (Dybowski, 1874), Eulimnogammarus vittatus (Dybowski, 1874), Eulimnogammarus verrucosus (Gerstf., 1858), Pallasea cancellus (Pallas, 1772) and Macrohectopus branickii (Dybowski, 1874)) and two mollusc species (Radix auricularia (L., 1758), Benedictia baicalensis (Gerstfeldt, 1859)) were collected. Amphipods and mollusks were collected in quantities of at least 30 individuals of each species. All organisms were placed in glass containers and fixed with 96% ethanol.

Fish were captured using a hydrobiological net. We specifically targeted Paracottus knerii (Dybowski, 1874). This species is abundant in the littoral zone of Lake Baikal and is also benthic. A total of six specimens were captured. All were fixed in individual vials in 96% ethanol.

2.3.3. Sampling in the Pier and Ship Mooring Area

In the pier and ship mooring area, we collected samples from the near-surface water layer both during wave activity and in calm conditions. Sediment samples were also collected at this location. All samples were collected in the same manner as described in the previous sections and were collected in quantities of at least three.

Furthermore, we collected qualitative samples at this location to assess biodiversity in this area. After collection, these samples were fixed with 96% ethanol.

2.4. Processing of Samples

2.4.1. Processing of Snow, Ice, Water and Sediment Samples

The samples were processed in accordance with a well-known protocol [39] with some modifications. These modifications were introduced due to the fact that we initially suspected the presence of a number of potentially brittle polymers in the samples [34,37]. Therefore, to minimize potential damage or destruction of these polymers, the samples were processed and dried at 55 °C, and KOH was used instead of H2O2 and 0.05 M Fe(II) [34,40,41].

Glass fiber filters (with a pore diameter of 1 μm) obtained after vacuum filtration were analyzed for microplastic particles under a stereo microscope (Unitron Z850, Boston, MA, USA). The lower limit of the analyzed particles in this study was 100 μm and was determined by the mesh size used in the plankton and neuston nets. In addition to particle size, particle color was also analyzed. The polymer type of the microplastic particles was determined using an M532 Raman microscope (EnSpectr, Chernogolovka, Russia) with a similarity coefficient of at least 0.7 [34]. This model has a laser wavelength of 532 nm and a spectral resolution of 6–8 cm−1. EnSpectr PRO spectral libraries (e.g., RamanLife (~24,000 spectra), Polymers (~2200 spectra)) were used for analysis.

2.4.2. Processing of Samples Containing Living Organisms

After collection, the samples were transported to the laboratory. In the laboratory, the plants were transferred to beakers containing 200 mL of a 5 M NaCl solution. The water in the containers with the plants was filtered through a mesh sieve (100 μm), and the contents were transferred to the beakers with the macrophytes. The beakers were then covered with foil and placed on an orbital shaker at 130 rpm for 2 h. After this, the contents were pipetted into a funnel with a filter and filtered using a vacuum pump. When 50 mL remained, the plants were removed, washed in distilled water, transferred to the filter in a Petri dish, and placed in a drying oven until completely dry (all samples were subsequently examined under a microscope to minimize the “loss” of microplastic particles; after this, the dry weight of the samples was determined on an analytical balance). The remaining water, as well as that in which the plants were washed, was also filtered. The resulting filters were placed in Petri dishes and examined for microplastic particles under a stereomicroscope. This technique had previously been tested [42].

In the laboratory, the mollusks were removed from their shells, and the length and width of each shell were measured. The collected mollusks and amphipods were then divided into separate samples of five specimens each. Each sample was placed in a separate 250 mL beaker. 100 mL of a 10% KOH solution (56 g/mol) was added, the beakers were covered with foil, and left for 24–48 h in a drying oven at 55 °C until the organic matter was completely dissolved (some samples with large amounts of organic matter were additionally shaken to improve the dissolution process). As a control, at least three beakers of KOH solution were poured and the same manipulations were performed as with the samples. After the organics had dissolved, 100 mL of hot water and NaCl were added to each sample until saturation (until the salt ceased to dissolve, approximately 60 g per 200 mL). This was then left to settle for another 24 h. After settling, the supernatant was transferred to a filter funnel using a pipette and filtered using a vacuum pump. After each sample, the funnel and pipette were rinsed with distilled water. Glass fiber filters with a pore diameter of 1 µm, similar to those described above, were used for filtration. The resulting filters were placed in Petri dishes for subsequent microplastic particle counting under a stereomicroscope at x96 magnification. All detected particles were counted and categorized into groups based on their morphological structure. Further analysis of the synthetic polymer types was performed using a Raman microscope, similar to the one described above.

Fish samples were processed in a similar manner. The exception in this case was that only the gills and gastrointestinal tract, rather than the entire fish tissue, were subjected to alkaline hydrolysis. The gills and gastrointestinal tract were processed separately. Ethanol was used to remove saponified fats [43].

2.4.3. Processing of Hydrobiological Samples

Quantitative samples collected at six locations during the winter, as well as qualitative samples collected during the summer in the pier and anchorage areas, were processed using standard hydrobiological methods. Samples were processed in small portions under a UNITRON Z850 stereomicroscope. All organisms were sorted into groups, and, where possible, organisms were identified to species level.

2.5. Precautionary Measures

All samples were collected and processed with utmost care. Sampling was performed wearing cotton clothing or using cotton capes over clothing (in winter). All sampling equipment was rinsed with water before and after use. Sample processing took place under a pre-prepared fume hood. Contamination monitoring was performed during sample processing.

2.6. Data Analysis

Data analysis and visualization were performed in the R software environment (V. 4.4.2). The Mann–Whitney test was used for statistical comparisons of two samples. For comparisons of three or more samples, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test with Holm’s correction. Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to clarify the relationship between particle number and depth. The strength of the relationship was determined using the Chaddock scale [37,38]. Additional data visualization was performed using multidimensional scaling. The Euclidean distance was used as a measure of similarity.

3. Results

3.1. Results of Sampling During the Winter Period

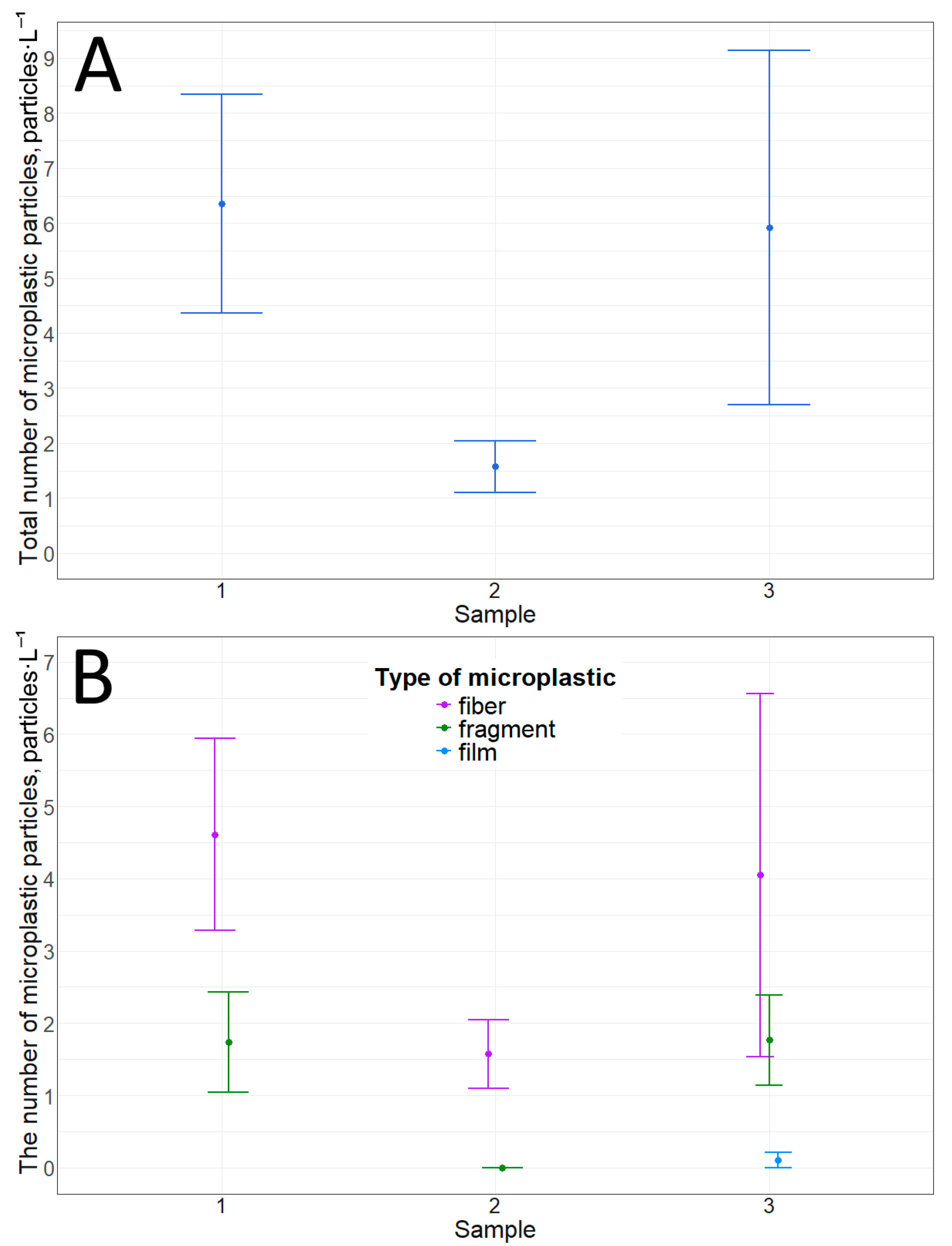

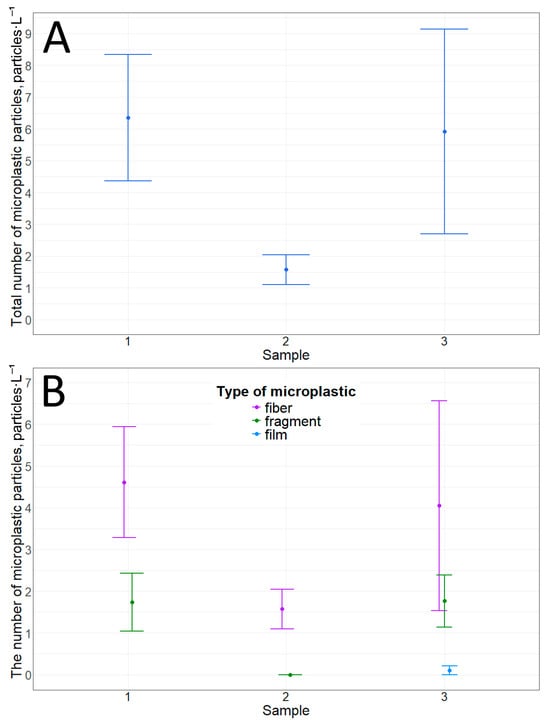

Three types of particles were detected in snow samples based on their morphological structure: fibers, fragments, and films. The number of microplastic particles in snow over ice cover ranged on average from 1.6 ± 0.5 to 6.4 ± 2.0 particles·L−1 (Table 2, Figure 2). Although fibers predominate over fragments (Table 2, Figure 2 and Figure 3), there are no statistically significant differences in the number of microplastic particles between the points. This statement corresponds to both the comparison of the total number of particles (p-value = 0.1) and the comparison of the same types of particles by morphological structure (between fibers (p-value = 0.2), between fragments (p-value = 0.06)). There are also no significant differences between the number of fibers and fragments.

Table 2.

Microplastic particles in snow on top of ice.

Figure 2.

Microplastic particles in snow cover on top of ice: (A)—total amount; (B)—number of particles with different morphological structures.

Figure 3.

Visualization of the distribution of microplastic particles with different morphological structures in snow cover using multidimensional scaling (the first digit corresponds to the sampling point number, and the second digit indicates the sample number).

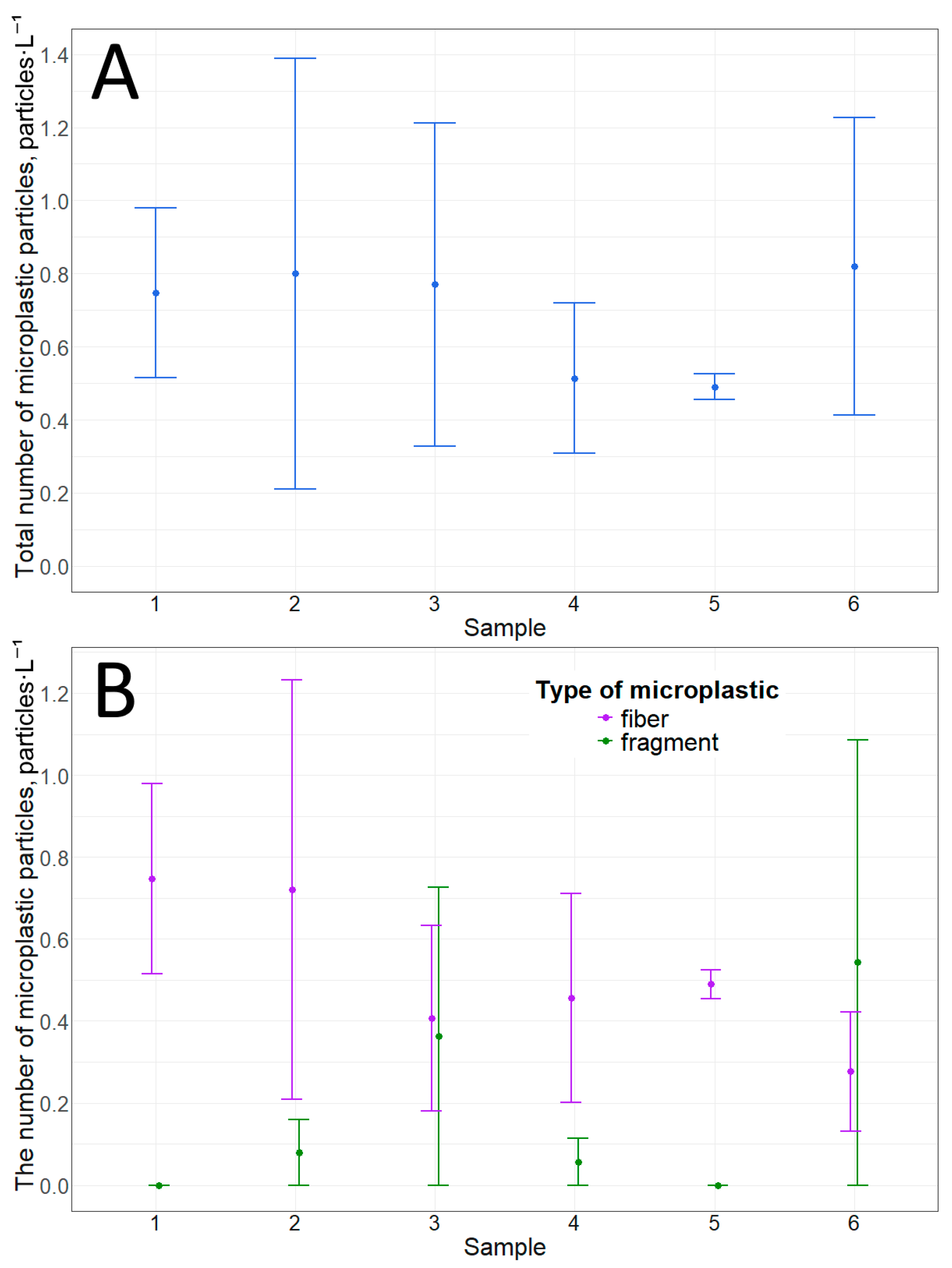

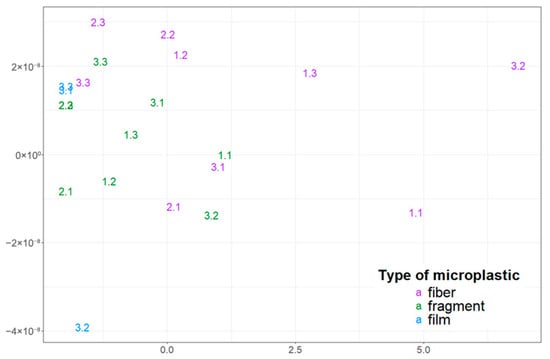

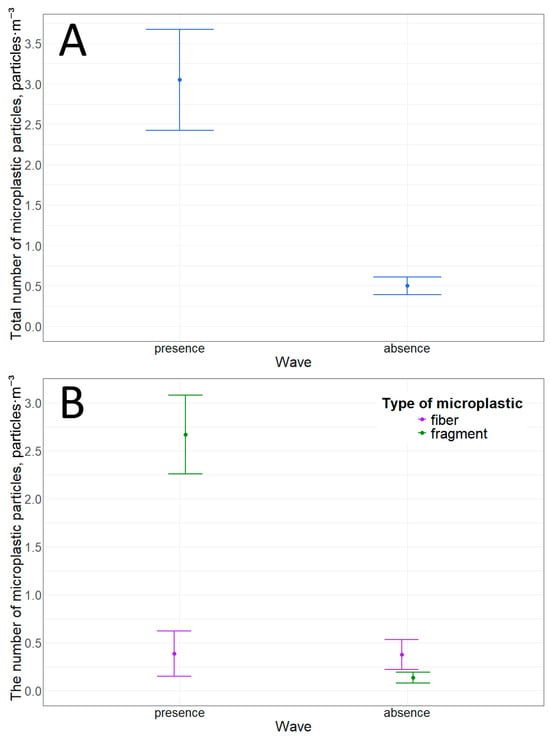

Ice sample analysis showed that the total number of microplastic particles at any distance from the shore in this study did not differ statistically (p-value = 0.9) (Figure 4). The number of microplastic particles ranged from 0.5 ± 0.04 to 0.8 ± 0.6 particles·L−1 (Table 3). Only two types of particles were detected in the samples: fibers and fragments. Moreover, in most cases, fibers were the predominant type of microplastic particle (based on average values) in terms of morphological structure (Figure 4). It is worth noting that there are no statistically significant differences between the number of fibers and fragments at each point (Table 4). Overall, the analysis confirms our previous preliminary data on microplastic particles from the underside of ice [28]. The available data lead us to believe that microplastic particles are most likely brought into Bolshie Koty Bay by gyre currents (which are present in Lake Baikal), which in turn are transported from the waters of the Selenga River.

Figure 4.

Microplastic particles from the underside of ice: (A)—total amount; (B)—number of particles with different morphological structures.

Table 3.

Microplastic particles from the underside of ice.

Table 4.

Comparison of the number of microplastic fragments with the number of microplastic fibers in ice samples using the Mann–Whitney test.

Analysis of zooplankton samples collected by the Juday net near the ice-water boundary showed that the absolute majority (in percentage terms) of organisms at this boundary are Copepoda nauplii (namely, E. baikalensis (the number of which fluctuates in the range from 1209 ± 611 to 24,757 ± 6205 specimens·m−3 and is 99–100%)) (Table 5). Cyclops kolensis Lilljeborg, 1901, and representatives of Cladocera, Ostracoda, and Harpacticoida were also present in small percentages at various sites. The last two groups are benthic organisms, but are occasionally observed in plankton, which may be due to passive transport by currents (during diurnal vertical migrations) [44,45].

Table 5.

Occurrence of different groups of organisms in the community under ice, %.

3.2. Microplastic Particles in Water and Sediments During Summer

Two types of microplastic particles based on their morphological structure (fibers and fragments) were detected in the near-surface water layer. The total number of microplastic particles in the near-surface water layer ranged on average from 2.7 ± 0.9 to 17.0 ± 3.2 particles·m−3 (Table 6). Analysis of the obtained data on tracks in the near-surface water layer with increasing distance from the shoreline showed that there were no statistically significant differences in the total number of microplastic particles (p-value = 0.7). Moreover, microplastic fragments were present in only one of the samples collected at a distance of 360–510 m from the shore. Microplastic fibers were observed in all samples collected, with the highest concentrations observed near the water’s edge. Given a number of factors (shallow depth and active wave action), microplastic particles cannot settle quietly to the bottom in this location and remain suspended. A pairwise comparison revealed some statistically significant differences in fiber concentrations (near the water’s edge). Thus, the concentration at location #1 was statistically significantly different from the concentrations at locations #2 (600–700 m from the shore) and #5 (900–1000 m from the shore). It is possible that with a larger number of samples collected, differences would also be observed at locations #3 and #4. However, confirming this pattern would require a larger number of samples.

Table 6.

Microplastic particles in the surface layer of water.

In turn, analysis of the obtained data on the distribution of microplastic particles in the pelagic layers showed that there may be a slight tendency for the concentration of microplastic particles to decrease with increasing depth (Table 7). Fibers remain the predominant type of microplastic particles in terms of morphological structure. The analysis reveals a fairly high (RS = −0.9), but statistically insignificant correlation coefficient (p-value = 0.08).

Table 7.

Microplastic particles in different layers of the water column.

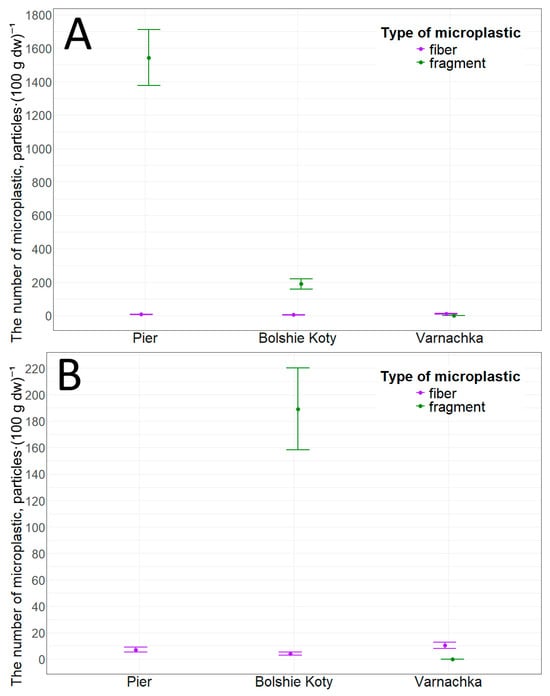

Sediment sampling took place at two sites: a relatively undisturbed area near Varnachka and directly near the village of Bolshie Koty. Significant concentrations of microplastic fragments were detected near the water’s edge near the village of Bolshie Koty (Table 8). It is worth noting that no statistically significant differences in the number of microplastic fragments and fibers were found near the village of Bolshie Koty (Table 9).

Table 8.

Microplastic particles in sediments.

Table 9.

Comparison of the number of microplastic fragments with the number of microplastic fibers.

3.3. Microplastic Particles in the Pier and Ship Mooring Area

An additional sampling site was the pier and ship mooring area. Water and sediment samples were collected here. Water samples were collected both during wave activity and in calm conditions.

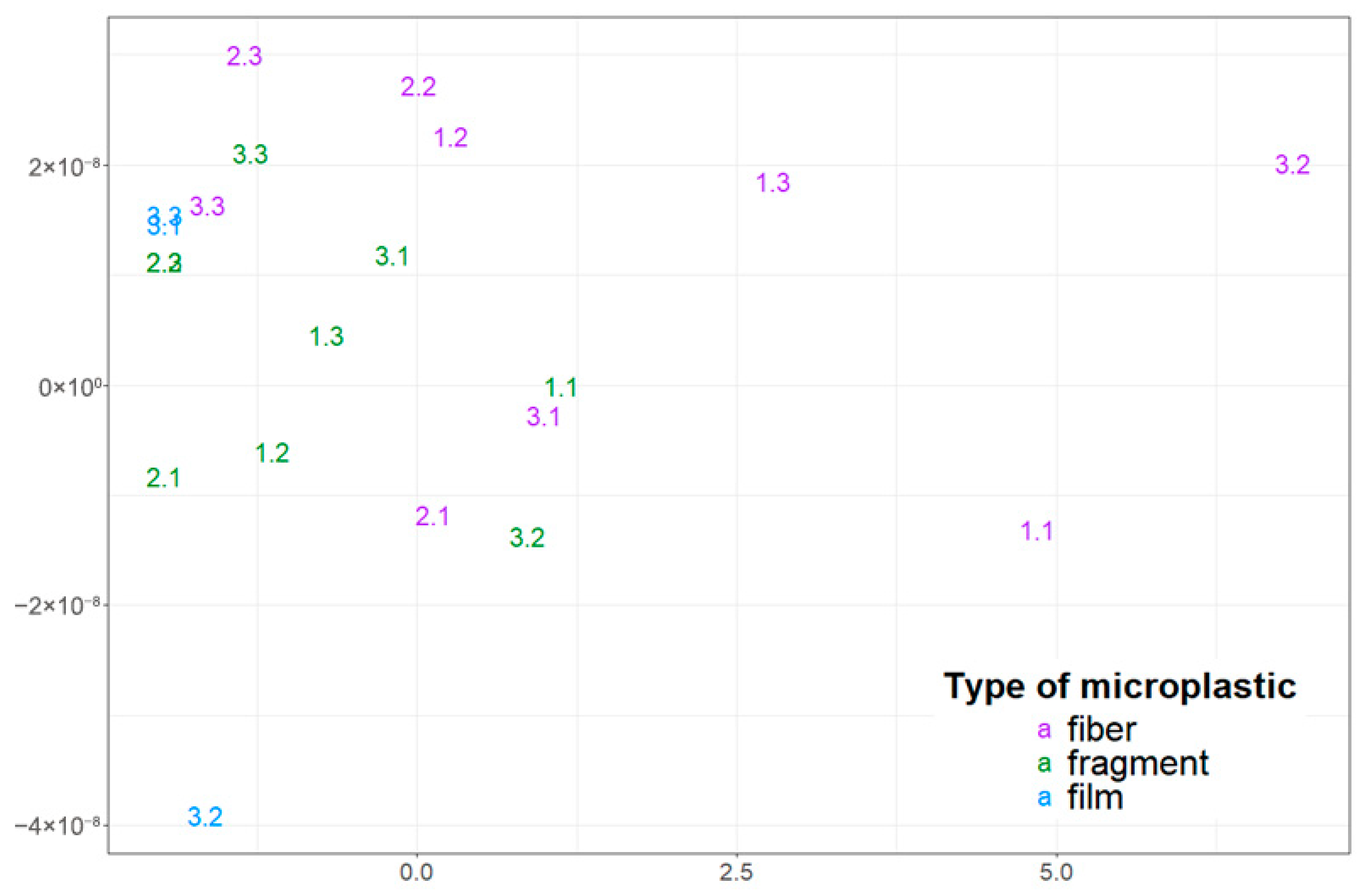

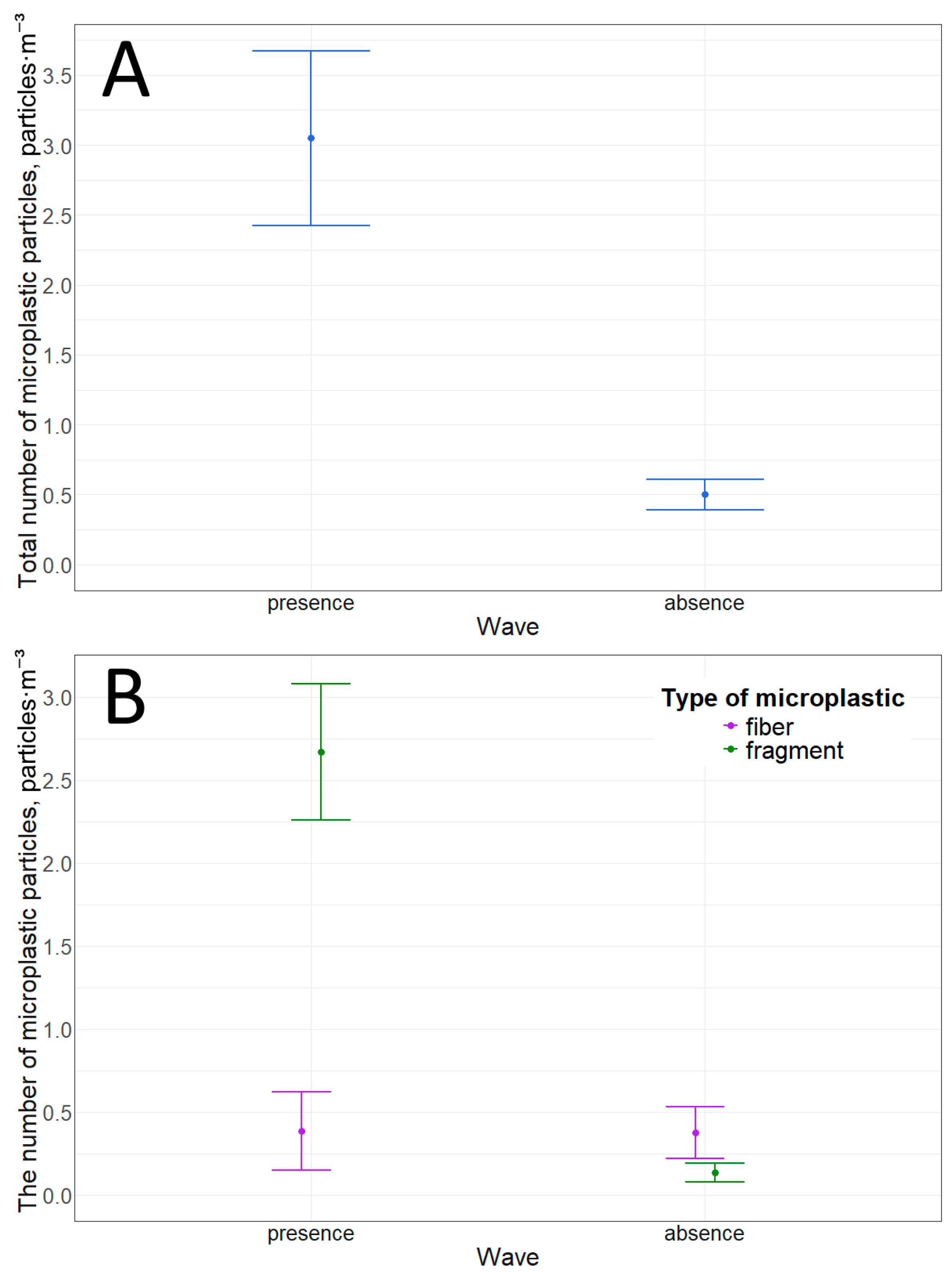

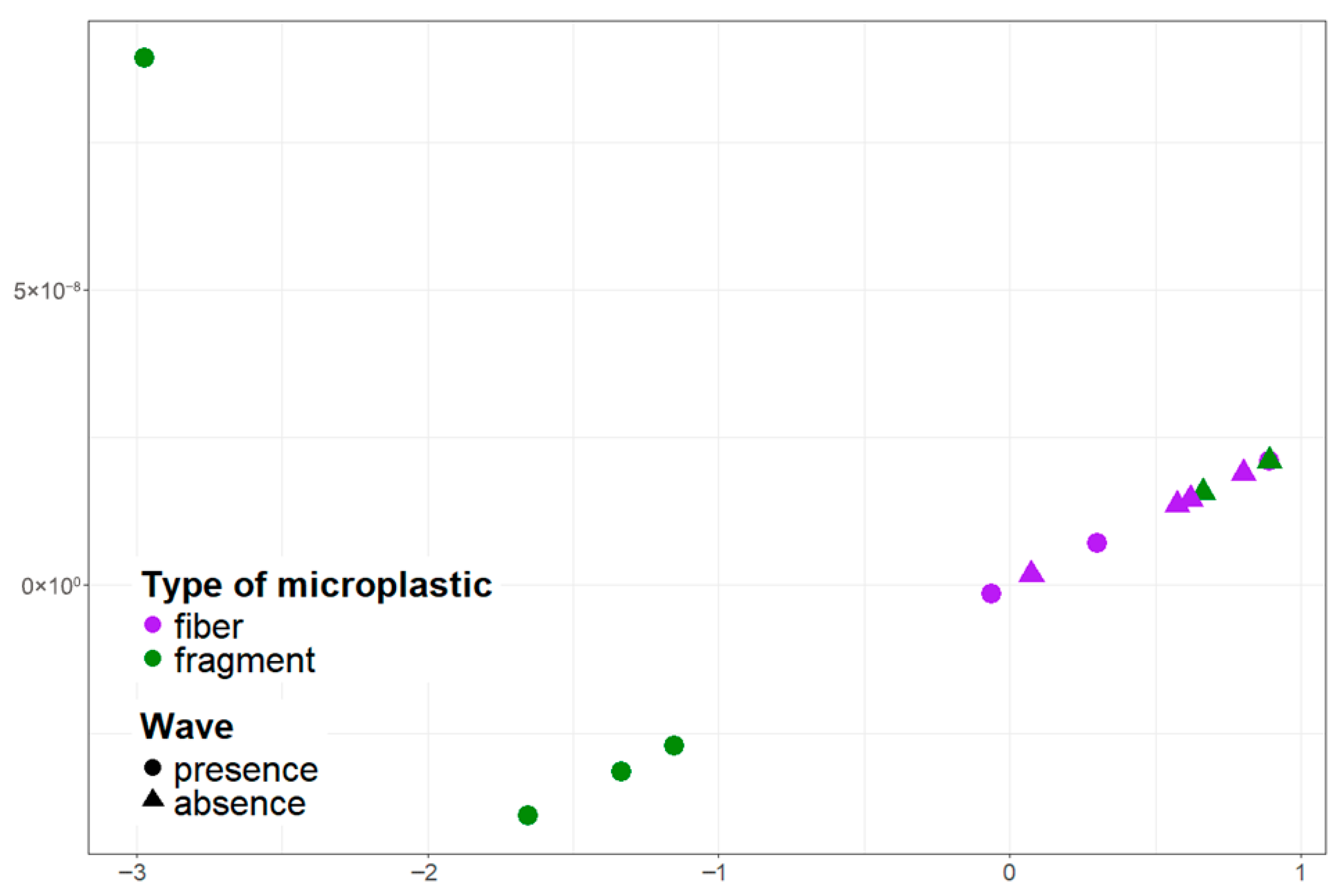

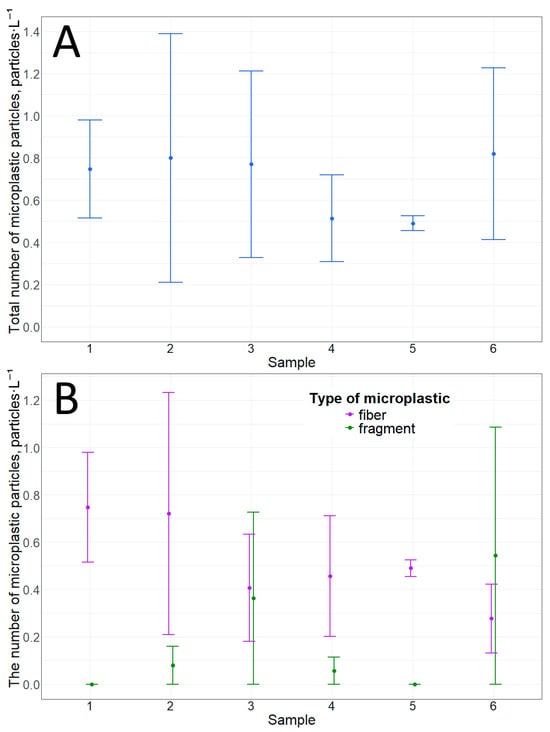

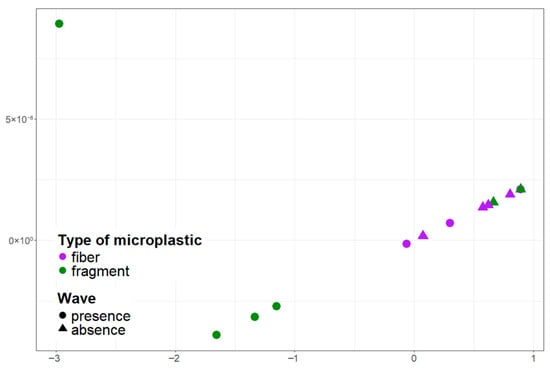

Microplastic fibers and fragments were detected at this location. Furthermore, stormy weather significantly increases the concentration of microplastic particles in the water (Table 10). The total particle concentration increases sixfold. This increase is due to the increased concentration of microplastic fragments. Wave activity increases the concentration of microplastic fragments by more than 20 times (Table 10, Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Table 10.

Microplastic particles in the water in the pier and ship mooring area.

Figure 5.

Microplastic particles in the surface water layer in the pier and ship mooring area: (A)—total quantity; (B)—quantity of particles with different morphological structures.

Figure 6.

Visualization of the distribution of microplastic particles with different morphological structures in the near-surface water layer in the pier and ship mooring area using multidimensional scaling.

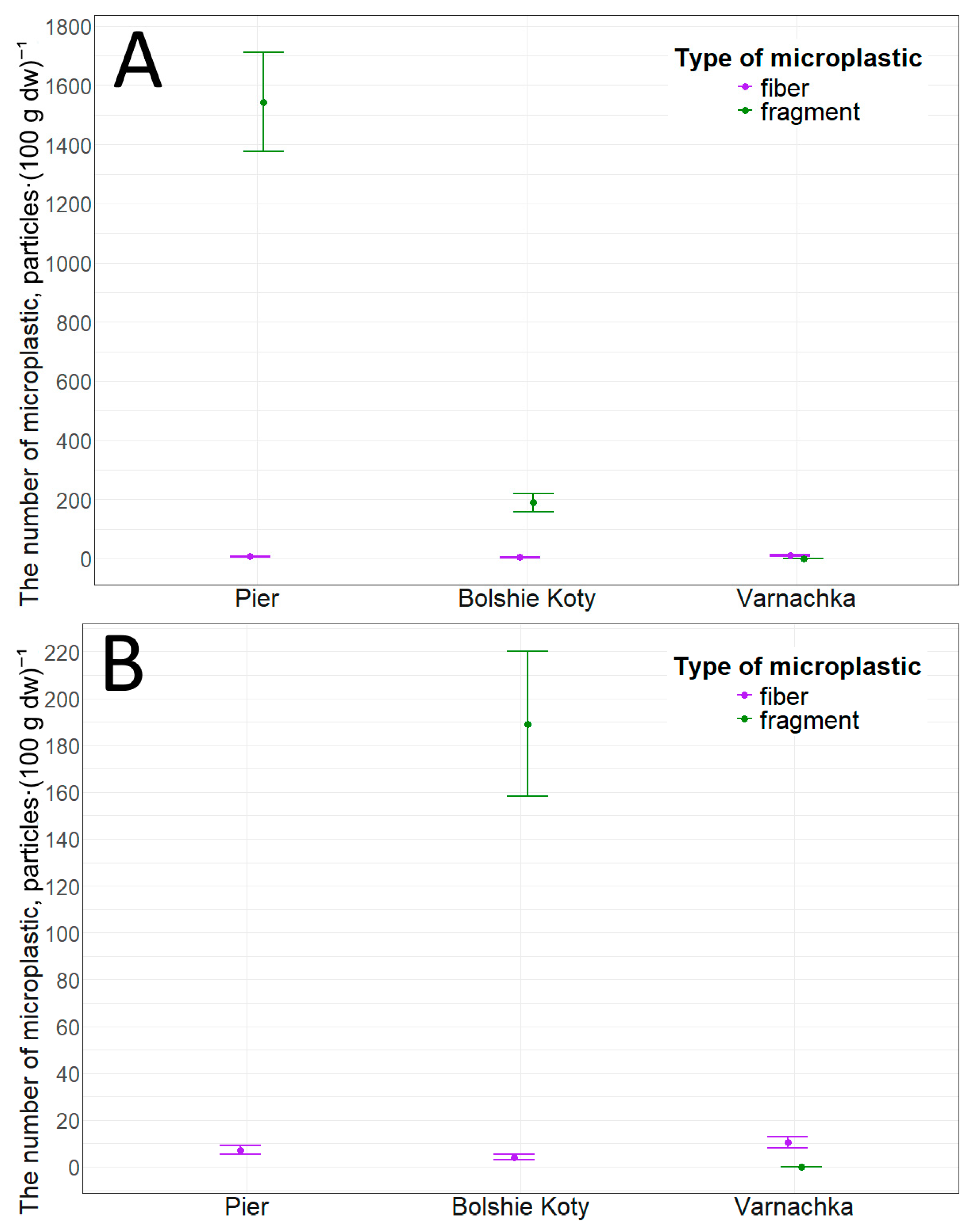

We also collected sediment samples at this location. Data analysis revealed that the concentration of microplastic particles in sediments at this site was 1550.9 ± 168.0 particles·(100 g dw)−1 (min—1238.0, max—1813.5). This concentration was primarily composed of fragments—1543.7 ± 167.4 particles·(100 g dw)−1 (min—1230.8, max—1803.1). Fibers account for a minority of particles—7.2 ± 1.8 particles·(100 g dw)−1 (min—4.1, max—10.4). The obtained values of microplastic particle concentration significantly exceed the values obtained in this study for other locations (Figure 7). However, statistically significant differences were found only between particle concentrations in the pier area and the Varnachka area (p-value = 0.01, r = 0.62).

Figure 7.

Microplastic particles in littoral sediments: (A)—general plan; (B)—close-up plan.

Analysis of qualitative samples (combined with visual observations) showed that despite the high level of pollution (evidently caused not only by microplastic particles), a fairly large number of aquatic organism species are observed in this location. We recorded more than 25 species (Table 11). Some of the organisms are planktonic or nektonic. However, the majority of the species are benthic organisms native to this location.

Table 11.

Biodiversity in the pier and ship mooring area, as determined by qualitative sampling and visual observations.

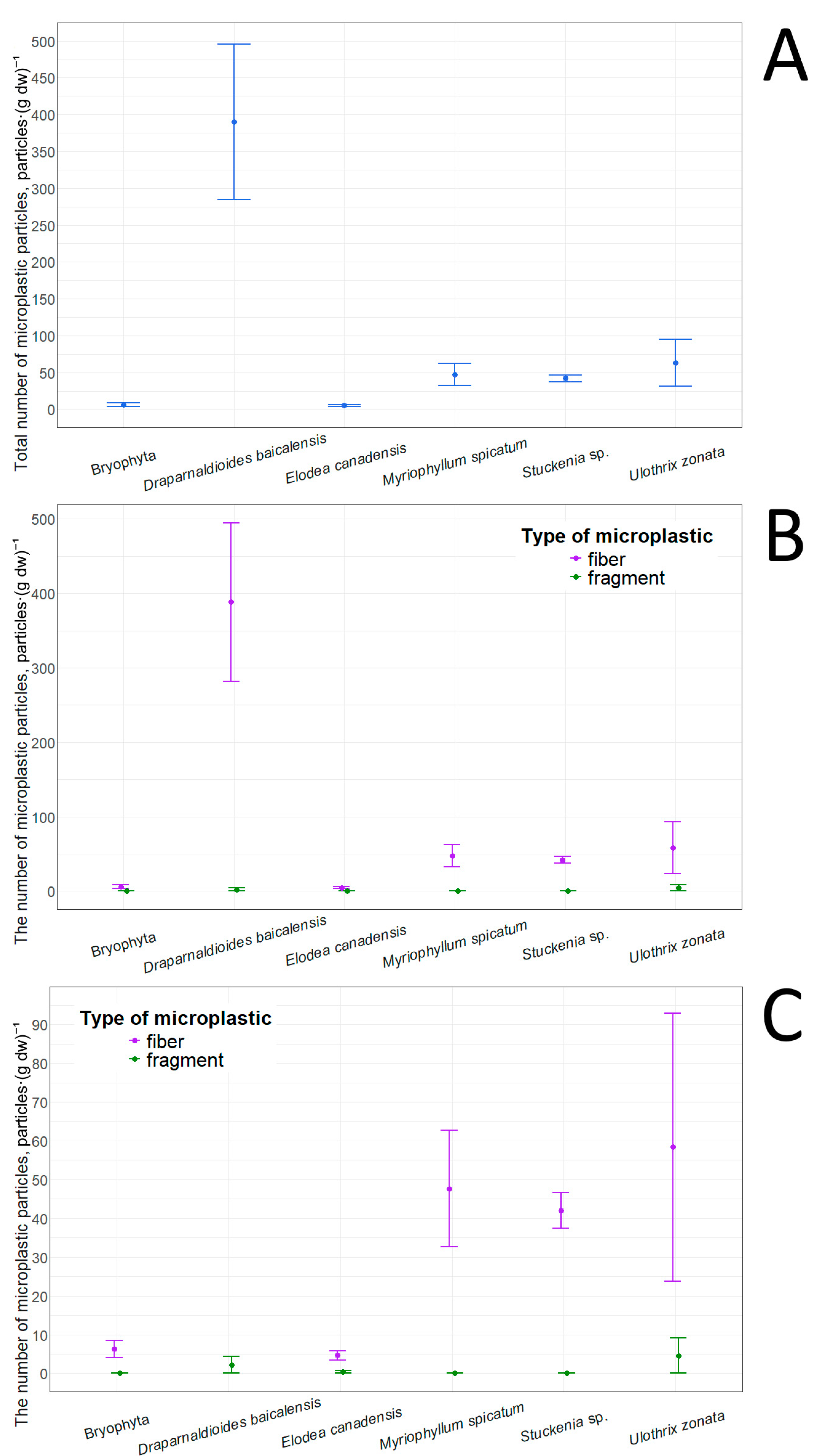

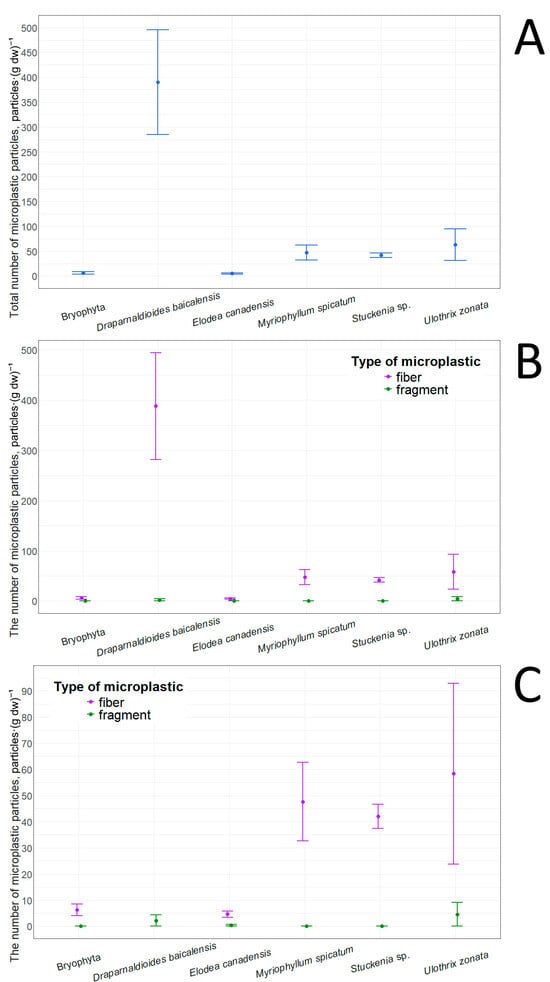

3.4. Adsorption of Microplastic Particles by Macrophytes

The lowest total number of adsorbed microplastic particles was found in E. canadensis (5.1 ± 1.4 particles·(g dw)−1), while the highest was found in D. baicalensis (390.4 ± 105.3) (Table 12). The number of adsorbed particles in Bryophyta was close to that in E. canadensis. In contrast, Stuckenia sp. and Myriophyllum spicatum occupied an intermediate position in terms of the number of adsorbed microplastic particles, but tended overall toward E. canadensis (Figure 8). However, U. zonata and D. baicalensis showed the opposite pattern. Pairwise comparisons of the total number of adsorbed particles revealed statistically significant differences only between Bryophyta and D. baicalensis (p-value = 0.04, r = 0.62), and between D. baicalensis and E. canadensis (p-value = 0.02, r = 0.64). Examination of particle types showed that fibers predominated in all taxa (Table 12), and in some cases (Stuckenia sp., M. spicatum, Bryophyta) they were the only type. This pattern likely reflects difficulty for fragments to adhere to the macrophyte surface, especially under conditions of wave activity, and also by the fact that their overall abundance in the lake water is significantly lower. In E. canadensis, the presence of adsorbed fragments can be explained by the relatively wide leaf blades (at least when compared with other species presented in this study). The highest concentrations of both fragments and fibers were found in D. baicalensis and U. zonata. This increased adsorption capacity can be explained by the presence of mucus on the surface of these algae. It should be noted that E. canadensis does not have mucus, while D. baicalensis and U. zonata are filamentous algae. It is worth noting that a comparison of adsorbed fibers and fragments between each taxon did not reveal statistically significant differences. Pairwise comparison of the number of adsorbed fragments between taxa also revealed no differences, and pairwise analysis of the number of fibers revealed differences only between D. baicalensis and E. canadensis (p-value = 0.01, r = 0.62).

Table 12.

The amount of microplastic particles adsorbed by plants.

Figure 8.

Microplastic particles adsorbed on macrophytes: (A)—total quantity; (B)—quantity of particles with different morphological structures; (C)—quantity of particles with different morphological structures in an enlarged format.

3.5. Microplastics in Macroinvertebrates and Fish

Among amphipod species, the highest concentrations were recorded for E. verrucosus (0.3 ± 0.02 particles·individual−1) and M. branickii (0.33 ± 0.05 particles·individual−1) (Table 13). In addition, the recorded concentrations statistically differed significantly from concentrations in other amphipod species (Table 14). It is worth noting that microplastic fibers were detected in all species, fragments only in E. vittatus and E. verrucosus, and films only in M. branickii.

Table 13.

The amount of microplastic particles ingested by aquatic organisms.

Table 14.

Comparison of microplastic particle counts between amphipod species.

Only microplastic fibers were detected in the mollusks (Table 13). However, statistically significant differences in the number of microplastic particles ingested were observed between mollusks (p-value = 0.04, r = 0.51).

Of the six P. knerii individuals, microplastic particles were detected in three. In two cases, particles were found in the gills (1 and 2 fibers, respectively) (Table 15), and in one case, in the gastrointestinal tract. The number of microplastic particles detected was 48. All particles were fragments.

Table 15.

The amount of microplastic particles in fish.

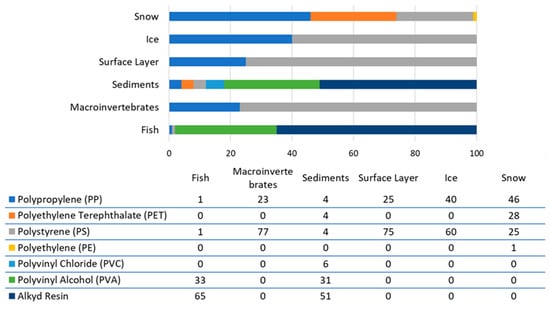

3.6. Size, Color, and Polymer Composition of Microplastic Particles

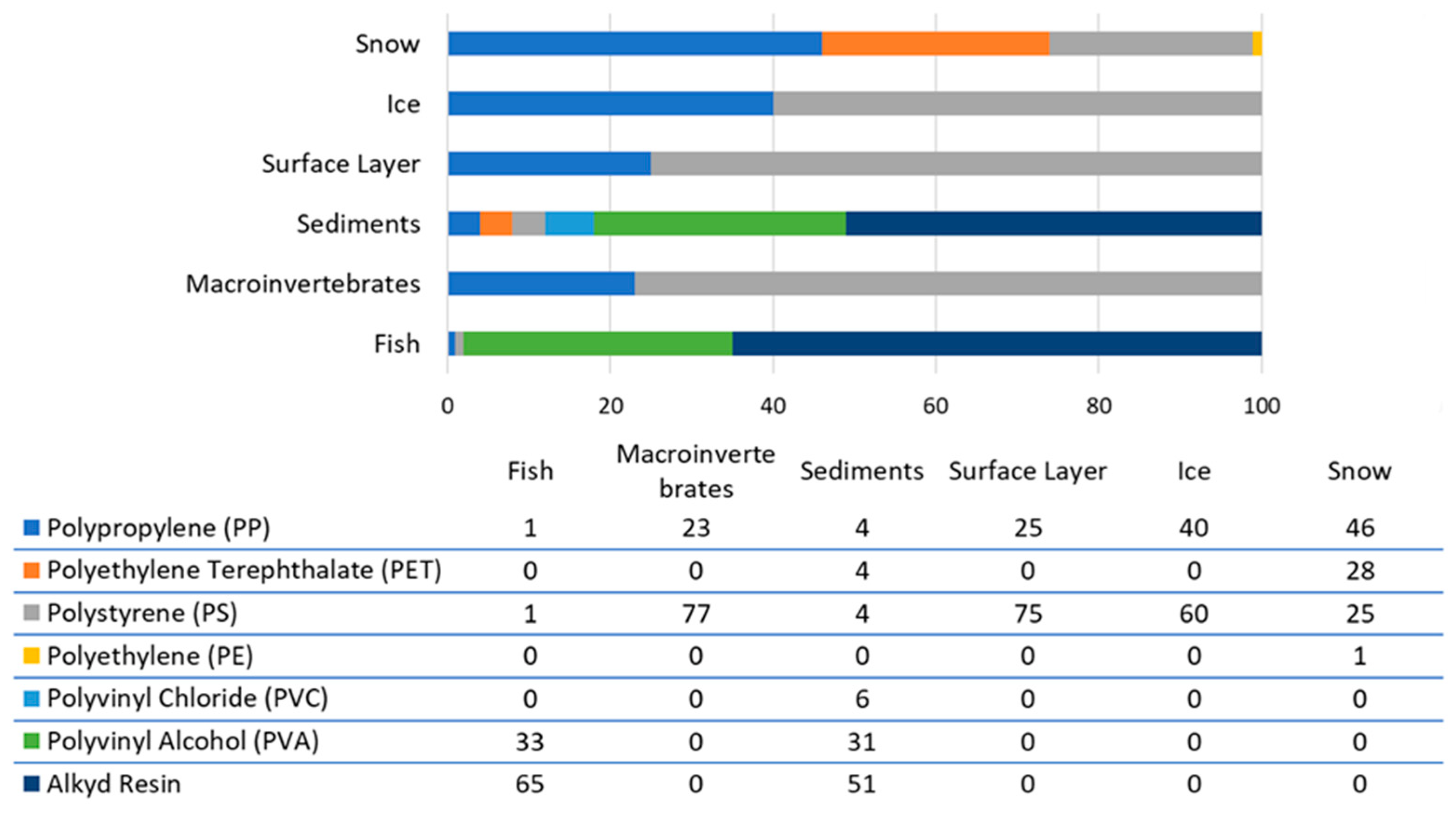

Analysis of microplastic particles revealed the presence of seven types of synthetic polymers (Figure 9): polypropylene (PP), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polystyrene (PS), polyethylene (PE), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), and alkyd resin. Different polymers predominate in different matrices. For example, polystyrene is found in ice, the surface layer, and macroinvertebrates; alkyd resin is found in sediments and fish; and polypropylene is found in snow.

Figure 9.

Polymer composition of microplastic particles (%).

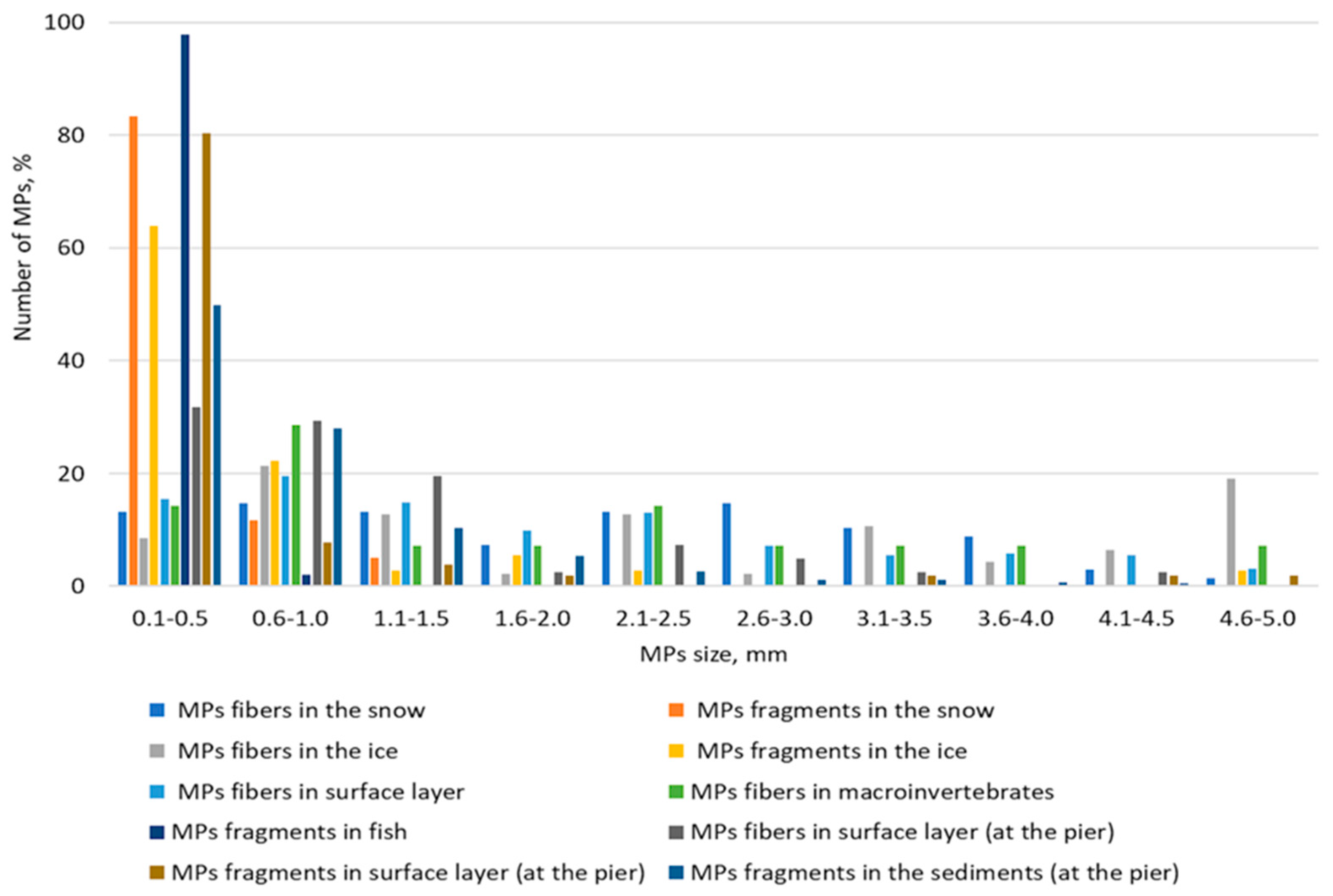

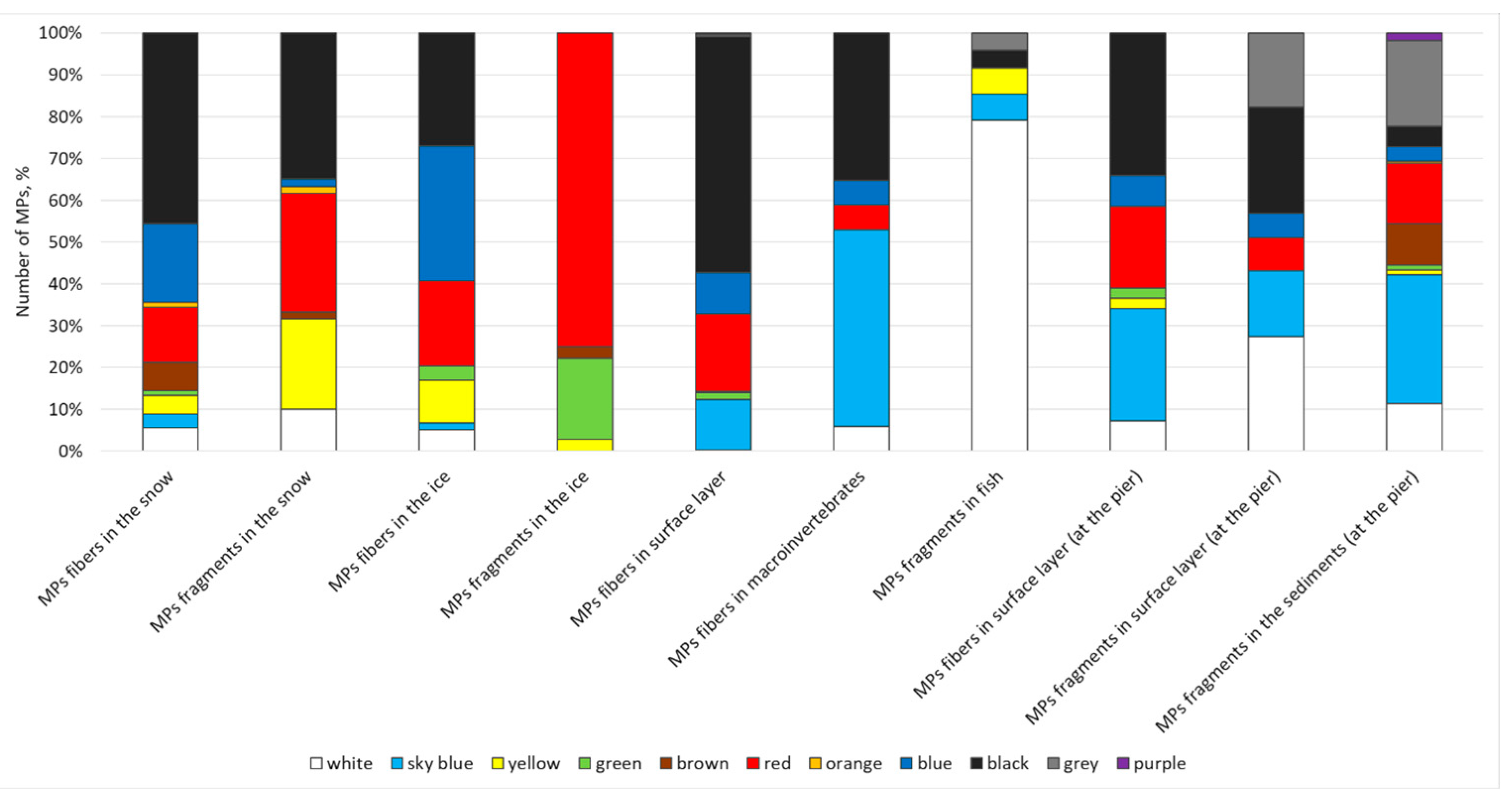

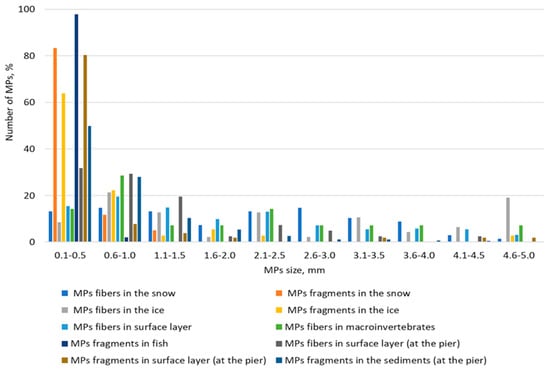

The results of this study show that in most cases, particles in the 0.1–0.5 mm size range predominate (Figure 10). However, in some cases, a relatively even distribution between the ranges is evident. Turning to color, it can be said that the color spectrum of microplastic particles is quite diverse (Figure 11). The most common colors are black, red, blue, white, light blue, and yellow.

Figure 10.

Particle size distribution of microplastics (%).

Figure 11.

Color range of microplastic particles (%).

4. Discussion

4.1. Microplastics in Snow and Ice

Atmospheric precipitation is one source of microplastic particles [46]. Wind also influences the transport of microplastic particles. Therefore, snow cover is often used as a matrix for determining microplastic concentrations among researchers. Our study analyzed the concentration of microplastic particles in snow over ice cover with increasing distance from the coastline. Microplastic particle concentrations in this study are comparable [47] or significantly lower than those reported in other studies [48,49]. Some studies [49] note that snow concentrations may decrease with distance from the coastline (or settlement). This is not reliably confirmed in this study, but the distance from the coast was also insignificant.

The concentration of microplastic fibers in Lake Baikal ice in this study was slightly lower than in our earlier study [28]. However, a comparable number of fragments was observed. Studies of other lake ecosystems have reported varying concentrations of microplastics, for example, 7.8 ± 1.2 particles·L−1 (Vesijärvi lake and Pikku Vesijärvi pond (Finland)) [50], from 269 ± 84 to 915 ± 117 particles·L−1 (Lake Ulansuhai (China)) [51]. It is worth noting that ice typically contains higher concentrations than water beneath it. Moreover, according to our data, microplastic concentrations are higher on the underside of the ice, near the boundary between the two aggregation states [28]. The danger in this case is that many organisms use the underside of the ice as a habitat during the winter [29]. With this in mind, we conducted water sampling directly under the ice to determine the composition of aquatic communities that may be in direct contact with, and therefore potentially exposed to, microplastics. This study showed that 99 to 100% of the community was represented by E. baikalensis nauplii. A recent study [36] demonstrated a relatively high frequency of microplastic particles among individuals of this species. Is it possible that microplastic particles are ingested by nauplii during the winter? This question remains unanswered.

4.2. Microplastics in Water and Sediments

In this study, the concentration of microplastic particles in the near-surface layer ranged from 2.7 ± 0.9 to 17.0 ± 3.2 particles·m−3. These concentration values are consistent with those in previous studies, where the average concentration in Lake Baikal ranged from 0.27 to 291 particles·m−3 [3,30,31,32,33]. However, it is worth noting that these studies used different sampling methods, filtered different volumes of water, and identified particles using different methods. Furthermore, the lower detection limits for particles also varied. Moreover, these concentration values (even taking into account the maximum values) are currently significantly lower than concentrations observed for a number of other lakes. For example, for Lake Ladoga with its tributaries (Russia) the value is 20–2400 particles·m−3 [52], for Lakes Al-Asfar and Al-Hubail (Saudi Arabia)—700–9000 particles·m−3 [53], for the Altai lakes (Russia)—11,000 particles·m−3 [54], for Lake Poyang (China)—5000–34,000 particles·m−3 [55], for the Great American Lakes basin with tributaries from less than 10 to 100,000 particles·m−3 [56], for Rewalsar Lake (India)—130,000 particles·m−3 [57].

Microplastic concentrations in different layers of Lake Baikal’s water column likely demonstrate a decrease in the number of microplastic particles with increasing depth (Table 7). Similar decreases in concentrations are generally observed in other aquatic ecosystems [58].

It is worth noting that the concentration of microplastic particles in lake water is significantly lower than in snow or ice. This has been observed in other studies and is due to the fact that microplastics are adsorbed and concentrated in ice [51,59], and also accumulate in snow over the winter. Despite low concentrations in the near-surface water layer, the concentration of microplastic particles apparently increases significantly in late spring. This is because melting ice and snow leads to a massive release of microplastic particles into the near-surface water layer [59].

The recorded average concentration of microplastic particles in lake sediments is currently 129 particles·(100 g dw)−1 [60]. In our case, the concentration away from the village is 10.6 ± 2.4 particles·(100 g dw)−1 (which is significantly less than the average), and the concentration directly near the village (on the contrary, slightly higher than the average) is 193.2 ± 30.2 particles·(100 g dw)−1. At the same time, for lakes around the world, concentrations of microplastic particles in sediments range from 0.5–1 to 1810 particles·(100 g dw)−1 [61,62,63,64,65,66].

4.3. High Concentrations of Microplastic Particles in the Pier and Ship Mooring Area

The concentrations of microplastic particles we found in the pier and ship mooring area deserve special attention. The maximum recorded amount of microplastic particles in this location was 1813.5 particles·(100 g dw)−1, similar to the maximum concentration recorded for lake sediments (1810 particles·(100 g dw)−1) [66]. Furthermore, it has long been known that microplastics in sediments can be displaced into the water column by wave activity [67]. In our case, wave activity causes the concentration of microplastics in the water column in this local area to increase more than 20-fold. Apparently, despite the fact that this area is very local, wave activity causes the displaced particles to settle over a larger area. Also, given the relatively large number of both benthic and planktonic organisms in this location, the potential risk of ingesting these particles also increases. Relatively recently, we recorded caddisfly larvae utilizing microplastic particles and incorporating them into their cases in large quantities [37]. Locations such as this are precisely the source of microplastics for caddisflies.

4.4. Adsorption of Microplastics on Macrophytes, as Well as Microplastics in Macroinvertebrates and Fish

In this study, the highest concentrations on a dry weight basis were observed for D. baicalensis and U. zonata. Both macrophyte species are among the most dominant in Lake Baikal. Furthermore, U. zonata forms a vegetation belt right at the lake’s edge, the same zone where we observed elevated concentrations of microplastic particles in the water. Both species have a mucous sheath [68], which apparently determines their enhanced adhesive properties. Published data fully confirms these assertions, indicating that the morphological and physiological characteristics of plants determine their adsorption capacity [42,69,70].

The amount of microplastic ingested by organisms depends on its concentration in water and sediment [26]. Given the low concentrations in these matrices in our study, we also recorded low concentrations in the organisms themselves. In our case, the highest concentrations were observed in E. verrucosus and M. branickii. We previously noted that in summer, E. verrucosus can be found near the water’s edge, where concentrations of microplastic particles in the water are significantly higher. The second species, in turn, is a pelagobiont and actively feeds on the planktonic copepod E. baicalensis. Furthermore, this species undergoes diurnal vertical migrations, including during the winter period, to the upper water layers and to the water-ice boundary [44]. Both of these circumstances could have led to our results. Furthermore, given that the sample sizes in this study were small, the data obtained should be considered preliminary and require further verification.

4.5. Types of Artificial Polymers, Morphological Structure, Size and Color

The types of artificial polymers we discovered have already been noted for Lake Baikal in various studies [3,32,34,36]. The type of matrix and the location of the study points can apparently influence the polymer ratio to some extent.

In this study, artificial polymers such as PVA and alkyd resin were observed in the pier area. This is directly related to the permanent mooring of ships in this area, as PVA and alkyd resin are components of modern paints. Similar findings have been observed in other areas of the lake [34]. The presence of these polymers in the fish’s stomach can be explained by the fact that at some point, the fish swam into this area and hunted there. It is worth noting that these fish are unique in that they are benthic and have wide jaws. When hunting, they make sharp movements toward their prey, thereby stirring up silt from the bottom (suspending it in the water). Given this, it is most likely that the microplastic particles were accidentally ingested by the fish while hunting.

The consumption of PP and PS by macroinvertebrates can be explained by their predominance in Lake Baikal water. These types of synthetic polymers are widely used in industry. Furthermore, due to their density, these polymers do not sink well and concentrate near the surface of water.

Although we identified three particle types based on morphological structure in this study (fibers, fragments, and films), fibers are the predominant type. This has been confirmed for many water bodies [6,7,71], including Lake Baikal [28,33,34]. The predominance of microplastic fragments in the pier and mooring area is associated with localized contamination [34].

In our study, the largest percentage of particles in many cases falls within the 100–500 µm range. This is confirmed in many studies [34,43]. Moreover, there is currently a need to shift the particle detection limit downwards [3]. The latter requires improvement and standardization of sampling and processing methods.

The diverse color range of microplastic particles primarily demonstrates the diversity of different dyes, which can also (and perhaps to a greater extent than the plastic itself) affect organisms [72,73,74]. This circumstance, in combination with the different types of artificial polymers, highlights the complexity and ambiguity in interpreting the obtained data.

4.6. Resume

Lake Baikal currently exhibits relatively low concentrations of microplastic particles in many matrices. These concentrations are expected to be even lower away from human impacts and populated areas [49]. However, summarizing the accumulated literature and based on the results of this study, it can be concluded that there are a number of zones of the lake where elevated concentrations of microplastic particles may be present. Four such zones can be identified. First, there are the ice and snow covers. In the former, particles are adsorbed from the water, while in the latter, microplastics, carried by wind and precipitation, accumulate. When the ice melts, all this plastic instantly ends up in the surface water layer. Second, there is the water’s edge zone. Due to wave activity, microplastics are constantly suspended here. Furthermore, microplastics accumulated in snow on land during the winter also end up here. Third, attention should be paid to macrophytes with a slimy sheath. This feature allows them to adsorb more microplastic particles than other macrophytes. Fourth, these are areas around piers and long-term moorings of ships. Artificial polymers from paints and varnishes are released into the water during the painting process or during the degradation of old coatings, and then settle and accumulate on the bottom in these areas. The detected concentrations are comparable to the highest concentrations recorded worldwide.

Regarding the potential toxicological impact of microplastics, it should be noted that this issue is quite complex [58]. On the one hand, the toxicological effects of “large” microplastic particles themselves have not yet been demonstrated (apparently, after ingestion, they pass through the gastrointestinal tract and are eliminated from the body naturally). In turn, “small” microplastic particles (several microns in size) can be retained and accumulate in the body and even pass through the walls of organs and individual cells, potentially remaining there for long periods [75]. An additional danger here is associated, among other things, with the fact that organisms (mainly crustaceans and, in particular, amphipods) have been observed that are capable of fragmenting large microplastic particles and converting them into smaller fractions [26,76]. On the other hand, the term microplastic encompasses a fairly broad range of substances. However, it is important to understand that the toxicological effects will depend on the type of synthetic polymer, as well as on the dyes, additives, and contaminants that can adsorb to the polymer surface [72,73,74]. Furthermore, pathogenic microorganisms can settle on the surface of plastic [9].

Our study was not designed to examine toxicological impacts, but it does provide insight into both the types of polymers encountered and the variety of colors (and, consequently, dyes). Furthermore, given the location in the pier and ship mooring area, it is clear that paints and varnishes are not the only contaminants there. Particles in this zone can potentially adsorb fuels and lubricants and many other substances, which must be taken into account when assessing toxicological effects under natural and experimental conditions. Furthermore, some studies note that low concentrations of particles may pose a hazard, but only under conditions of chronic exposure [77]. It is worth noting that the results of some recent experiments show that microplastic particles, for example, can mitigate the toxic effects of copper, while the results for other pollutants are highly variable [78]. Such results confirm the ambiguity and difficulty of interpreting the effects of microplastic particles and the need for further research (including studies on the occurrence of oxidative stress) [77].

5. Conclusions

This study was the first for Lake Baikal to utilize a multi-matrix approach. The results demonstrate the presence of distinct pockets of microplastic particle concentration. In this case, four such pockets were identified: ice and snow cover (potentially the near-surface layer during ice and snow melt), the lakeshore, macrophytes with mucus, and the pier and mooring area. The dominant type in terms of morphological structure is fibers; however, in some cases associated with localized contamination, microplastic fragments may predominate. Regarding the polymer composition, in the case of fragments, it was found that polymers such as alkyd resin and polyvinyl alcohol can be found in large quantities in localized areas.

A multi-matrix approach to studying microplastic pollution in aquatic ecosystems provides a more comprehensive picture than studies that analyze concentrations using only a single matrix. We recommend that future research focus on the effects of microplastic particles on organisms associated with areas of highest concentrations, taking into account chronic exposure to both microplastic particles and associated factors (other pollutants, dyes, etc.).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K. and A.L.; methodology, D.K., A.L., S.B., A.G., A.S. and Y.F.; software, Y.E.; validation, D.K. and Y.E.; formal analysis, Y.E.; investigation, A.S., A.G., R.A., V.V., E.G. and M.M.; resources, Y.E., S.B. and A.L.; data curation, D.K. and Y.E.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K. and Y.E.; writing—review and editing, D.K. and Y.E.; visualization, D.G., Y.E. and S.B.; supervision, D.K. and E.S.; project administration, D.K.; funding acquisition, D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from the Russian Science Foundation No. 24-24-00371, “https://rscf.ru/project/24-24-00371/ (accessed on 12 November 2025)”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data used are included in the article. In addition, any data used for this study will be provided upon request by the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alena Slepchenko, Alexander Bashkirtsev, Diana Rechile, Ivan Kodatenko, Kirill Salovarov, Anastasia Olimova, Darya Kondratieva, Anna Solomka, Svetlana Vorobieva, Danil Vorobiev and Natalia Kulbachnaya for their assistance in conducting the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Eriksen, M.; Mason, S.; Wilson, S.; Box, C.; Zellers, A.; Edwards, W.; Farley, H.; Amato, S. Microplastic Pollution in the Surface Waters of the Laurentian Great Lakes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 77, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Free, C.M.; Jensen, O.P.; Mason, S.A.; Eriksen, M.; Williamson, N.J.; Boldgiv, B. High-Levels of Microplastic Pollution in a Large, Remote, Mountain Lake. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 85, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, M.V.; Yamamuro, M.; Timoshkin, O.A.; Shirokaya, A.A.; Kameda, Y. Lake-Wide Assessment of Microplastics in the Surface Waters of Lake Baikal, Siberia. Limnology 2022, 23, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala-Alarcón, F.L.; Huchin-Mian, J.P.; González-Muñoz, M.D.P.; Kozak, E.R. In Situ Microplastic Ingestion by Neritic Zooplankton of the Central Mexican Pacific. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 319, 120994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wong, C.Y.; Tam, N.F.Y.; Lo, H.S.; Cheung, S.G. Microplastics in Invertebrates on Soft Shores in Hong Kong: Influence of Habitat, Taxa and Feeding Mode. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 715, 136999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelein, A.; Int-Veen, I.; Kammann, U.; Scharsack, J.P. Microplastic Fibers—Underestimated Threat to Aquatic Organisms? Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 777, 146045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, Y.; Ershova, A.; Batasheva, S.; Vorobiev, E.; Rakhmatullina, S.; Vorobiev, D.; Fakhrullin, R. Microplastics in Freshwater: A Focus on the Russian Inland Waters. Water 2022, 14, 3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.; Fowler, S.W.; Habibi, N.; Behbehani, M. Micro-Nano Plastic in the Aquatic Environment: Methodological Problems and Challenges. Animals 2022, 12, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citterich, F.; Lo Giudice, A.; Azzaro, M. A Plastic World: A Review of Microplastic Pollution in the Freshwaters of the Earth’s Poles. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 869, 161847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorino, P.; Anselmi, S.; Esposito, G.; Bertoli, M.; Pizzul, E.; Barceló, D.; Elia, A.C.; Dondo, A.; Prearo, M.; Renzi, M. Microplastics in Biotic and Abiotic Compartments of High-Mountain Lakes from Alps. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 150, 110215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, E.J.; Smith, K.L. Plastics on the Sargasso Sea Surface. Science 1972, 175, 1240–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, E.J.; Anderson, S.J.; Harvey, G.R.; Miklas, H.P.; Peck, B.B. Polystyrene Spherules in Coastal Waters. Science 1972, 17, 749–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikitin, O.V.; Latypova, V.Z.; Ashikhmina, T.Y.; Kuzmin, R.S.; Nasyrova, E.I.; Haripov, I.I. Microscopic Particles of Synthetic Polymers in Freshwater Ecosystems: Review and the Current State of the Problem. Theor. Appl. Ecol. 2020, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Vidal, A.; Canals, M.; De Haan, W.P.; Romero, J.; Veny, M. Seagrasses Provide a Novel Ecosystem Service by Trapping Marine Plastics. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haegerbaeumer, A.; Mueller, M.-T.; Fueser, H.; Traunspurger, W. Impacts of Micro- and Nano-Sized Plastic Particles on Benthic Invertebrates: A Literature Review and Gap Analysis. Front. Environ. Sci. 2019, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, F.M.; Tilley, R.M.; Tyler, C.R.; Ormerod, S.J. Microplastic Ingestion by Riverine Macroinvertebrates. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 646, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, M.; Van Cauwenberghe, L.; Vandegehuchte, M.B.; Janssen, C.R. New Techniques for the Detection of Microplastics in Sediments and Field Collected Organisms. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 70, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, L.M.; Ivar Do Sul, J.A.; Costa, M.F. Uptake and Ingestion Are the Main Pathways for Microplastics to Enter Marine Benthos: A Review. Food Webs 2020, 24, e00150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, A.; Antonioli, D.; Masseroni, A.; Chiarcos, R.; Laus, M.; Tremolada, P. Following the Fate of Microplastic in Four Abiotic and Biotic Matrices along the Ticino River (North Italy). Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 823, 153638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.-T.; Fueser, H.; Höss, S.; Traunspurger, W. Species-Specific Effects of Long-Term Microplastic Exposure on the Population Growth of Nematodes, with a Focus on Microplastic Ingestion. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 118, 106698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P.; Lin, S.; Turner, J.P.; Ke, P.C. Physical Adsorption of Charged Plastic Nanoparticles Affects Algal Photosynthesis. J. Phys. Chem. 2010, 114, 16556–16561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutow, L.; Eckerlebe, A.; Giménez, L.; Saborowski, R. Experimental Evaluation of Seaweeds as a Vector for Microplastics into Marine Food Webs. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goss, H.; Jaskiel, J.; Rotjan, R. Thalassia Testudinum as a Potential Vector for Incorporating Microplastics into Benthic Marine Food Webs. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 135, 1085–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, S.Y.; Bruce, T.F.; Bridges, W.C.; Klaine, S.J. Responses of Hyalella azteca to Acute and Chronic Microplastic Exposures. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2015, 34, 2564–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, S.M.; Maxein, J.; Koop, J.H.E. Low-cost Microplastic Visualization in Feeding Experiments Using an Ultraviolet Light-emitting Flashlight. Ecol. Res. 2020, 35, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos-Cárdenas, A.; O’Halloran, J.; Van Pelt, F.N.A.M.; Jansen, M.A.K. Rapid Fragmentation of Microplastics by the Freshwater Amphipod Gammarus Duebeni (Lillj.). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Weert, S.; Redondo-Hasselerharm, P.E.; Diepens, N.J.; Koelmans, A.A. Effects of Nanoplastics and Microplastics on the Growth of Sediment-Rooted Macrophytes. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 654, 1040–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnaukhov, D.; Biritskaya, S.; Dolinskaya, E.; Teplykh, M.; Ermolaeva, Y.; Pushnica, V.; Bukhaeva, L.; Kuznetsova, I.; Okholina, A.; Silow, E. Distribution Features of Microplastic Particles in the Bolshiye Koty Bay (Lake Baikal, Russia) in Winter. Pollution 2022, 8, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoshkin, O.A. Lake Baikal: Diversity of Fauna, the Problem of Its Immiscibility and Origin, Ecology and “Exotic” Communities. In Index of Animal Species Inhabiting Lake Baikal and Its Catchment Area: Lake Baikal; Nauka: Novosibirsk, Russia, 2001; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, M.F.; Ozersky, T.; Woo, K.H.; Shchapov, K.; Galloway, A.W.E.; Schram, J.B.; Snow, D.D.; Timofeyev, M.A.; Karnaukhov, D.Y.; Brousil, M.R.; et al. A Unified Dataset of Colocated Sewage Pollution, Periphyton, and Benthic Macroinvertebrate Community and Food Web Structure from Lake Baikal (Siberia). Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 2022, 7, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.F.; Ozersky, T.; Woo, K.H.; Shchapov, K.; Galloway, A.W.E.; Schram, J.B.; Rosi, E.J.; Snow, D.D.; Timofeyev, M.A.; Karnaukhov, D.Y.; et al. Effects of Spatially Heterogeneous Lakeside Development on Nearshore Biotic Communities in a Large, Deep, Oligotrophic Lake. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2022, 67, 2649–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Il’ina, O.V.; Kolobov, M.Y.; Il’inskii, V.V. Plastic Pollution of the Coastal Surface Water in the Middle and Southern Baikal. Water Resour. 2021, 48, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnaukhov, D.Y.; Biritskaya, S.A.; Dolinskaya, E.M.; Teplykh, M.A.; Silenko, N.; Ermolaeva, Y.K.; Silow, E.A. Pollution by Macro-and Microplastic of Large Lacustrine Ecosystems in Eastern Asia. Pollut. Res. 2020, 39, 353–355. [Google Scholar]

- Solodkova, A.; Biritskaya, S.; Guliguev, A.; Rechile, D.; Ermolaeva, Y.; Lavnikova, A.; Golubets, D.; Slepchenko, A.; Kodatenko, I.; Bashkircev, A.; et al. Microplastics in Sediments of the Littoral Zone and Beach of Lake Baikal. Limnol. Rev. 2025, 25, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battulga, B.; Kawahigashi, M.; Oyuntsetseg, B. Distribution and Composition of Plastic Debris along the River Shore in the Selenga River Basin in Mongolia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 14059–14072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.; Yamashita, R.; Ogawa, H.; Sheveleva, N.G.; Penkova, O.G.; Yamamuro, M.; Moore, M.V. Microplastics in Freshwater Copepods of Lake Baikal. J. Gt. Lakes Res. 2025, 51, 102495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnaukhov, D.Y.; Lavnikova, A.V.; Nepokrytykh, A.V.; Zhdanov, I.A.; Salovarov, K.V.; Guliguev, A.T.; Osadchy, B.V.; Biritskaya, S.A.; Ermolaeva, Y.K.; Maslennikova, M.A.; et al. Baikal Endemic and Palearctic Species of Caddisflies (Trichoptera) Build Cases from Microplastics. Acta Biol. Sib. 2024, 10, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biritskaya, S.A.; Dolinskaya, E.M.; Maslennikova, M.A.; Bukhaeva, L.B.; Pushnitsa, V.A.; Ermolaeva, Y.K.; Lavnikova, A.V.; Golubets, D.I.; Nazarova, S.A.; Karnaukhov, D.Y.; et al. The Ability of Gastropods of Lake Baikal to Consume and Excrete Microplastic Particles of Different Morphological Structures. Inland Water Biol. 2024, 17, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masura, J.; Baker, J.; Foster, G.; Arthur, C.; Herring, C. Laboratory Methods for the Analysis of Microplastics in the Marine Environment: Recommendations for Quantifying Synthetic Particles in Waters and Sediments; NOAA Marine Debris Division: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2015.

- Gulizia, A.M.; Brodie, E.; Daumuller, R.; Bloom, S.B.; Corbett, T.; Santana, M.M.F.; Motti, C.A.; Vamvounis, G. Evaluating the Effect of Chemical Digestion Treatments on Polystyrene Microplastics: Recommended Updates to Chemical Digestion Protocols. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2022, 223, 2100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fiore, C.; Ishikawa, Y.; Wright, S.L. A Review on Methods for Extracting and Quantifying Microplastic in Biological Tissues. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 464, 132991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guliguev, A.; Solodkova, A.; Kodatenko, I.; Kondratieva, D.; Biritskaya, S.; Lavnikova, A.; Ermolaeva, Y.; Solomka, A.; Kulbachnaya, N.; Olimova, A.; et al. Adsorption of Different Types of Microplastic Particles by Macrophytes of Lake Baikal. Acta Biol. Sib. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, Y.A. Pollution of Surface Waters and Bottom Sediments of the Ob and Yenisei River Basins with Microplastics and Its Interaction with Hydrobionts. Ph.D. Thesis, Tomsk State University, Tomsk, Russia, 2024. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Karnaukhov, D.Y.; Dolinskaya, E.M.; Biritskaya, S.A.; Teplykh, M.A.; Ermolaeva, Y.K.; Pushnica, V.A.; Bukhaeva, L.B.; Makhov, I.A.; Silow, E.A.; Lavnikova, A.V. Daily Vertical Migrations of Lake Baikal Amphipods: Major Players, Seasonal Dynamics and Potential Causes. Int. J. Aquat. Biol. 2023, 11, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ermolaeva, Y.K.; Dolinskaya, E.M.; Biritskaya, S.A.; Maslennikova, M.A.; Bukhaeva, L.B.; Lavnikova, A.V.; Golubets, D.I.; Kulbachnaya, N.A.; Okholina, A.I.; Milovidova, I.V.; et al. Daily Vertical Migrations of Aquatic Organisms and Water Transparency as Indicators of the Potential Exposure of Freshwater Lakes to Light Pollution. Acta Biol. Sib. 2024, 10, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanova-Solano, C.; Hernández-Sánchez, C.; Díaz-Peña, F.J.; González-Sálamo, J.; González-Pleiter, M.; Hernández-Borges, J. Microplastics in Snow of a High Mountain National Park: El Teide, Tenerife (Canary Islands, Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 873, 162276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parolini, M.; Antonioli, D.; Borgogno, F.; Gibellino, M.C.; Fresta, J.; Albonico, C.; De Felice, B.; Canuto, S.; Concedi, D.; Romani, A.; et al. Microplastic Contamination in Snow from Western Italian Alps. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, H.; Xu, H.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, D.; Wang, X. Diverse and High Pollution of Microplastics in Seasonal Snow across Northeastern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, S.; Schwarz, D.; Rashedin, M.; Hasan, M.I.; Kholodova, D.; Billings, S.; Barnes, D.L.; Misarti, N.; Saleh, N.B.; Aggarwal, S. Unveiling Microplastics Pollution in Alaskan Waters and Snow. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2024, 10, 2020–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopetani, C.; Chelazzi, D.; Cincinelli, A.; Esterhuizen-Londt, M. Assessment of Microplastic Pollution: Occurrence and Characterisation in Vesijärvi Lake and Pikku Vesijärvi Pond, Finland. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhang, S.; Lu, J.; Li, W.; Sun, B.; Zhao, S.; Yao, D.; Huotari, J. The Spatial Distribution and Abundance of Microplastics in Lake Waters and Ice during Ice-Free and Ice-Covered Periods. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 323, 121268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozdnyakov, S.R.; Institute of Limnology, Russian Academy of Sciences; Ivanova, E.V. Estimation of the Microplastics Concentrations in the Water Column and Bottom Sediments of Ladoga Lake. Reg. Ecol. 2018, 54, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picó, Y.; Alvarez-Ruiz, R.; Alfarhan, A.H.; El-Sheikh, M.A.; Alshahrani, H.O.; Barceló, D. Pharmaceuticals, Pesticides, Personal Care Products and Microplastics Contamination Assessment of Al-Hassa Irrigation Network (Saudi Arabia) and Its Shallow Lakes. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 701, 135021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malygina, N.; Mitrofanova, E.; Kuryatnikova, N.; Biryukov, R.; Zolotov, D.; Pershin, D.; Chernykh, D. Microplastic Pollution in the Surface Waters from Plain and Mountainous Lakes in Siberia, Russia. Water 2021, 13, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Di, M.; Wang, J. Microplastic Abundance, Distribution and Composition in Water, Sediments, and Wild Fish from Poyang Lake, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 170, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karen, K.; Rooney, R.; Rochman, C.; Hataley, E. Final Report of the IJC Great Lakes Science Advisory Broad Work Group on Microplastics. 2024. Available online: https://ijc.org/sites/default/files/SAB_MicroplasticsReport_2024.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Bulbul, M.; Kumar, S.; Ajay, K.; Anoop, A. Spatial Distribution and Characteristics of Microplastics and Associated Contaminants from Mid-Altitude Lake in NW Himalaya. Chemosphere 2023, 326, 138415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Kvale, K.F.; Zhu, L.; Zettler, E.R.; Egger, M.; Mincer, T.J.; Amaral-Zettler, L.A.; Lebreton, L.; Niemann, H.; Nakajima, R.; et al. The Distribution of Subsurface Microplastics in the Ocean. Nature 2025, 641, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.C.; Yang, J.L.; Yang, F.; Yang, W.H.; Li, W.P.; Li, X. Distribution Characteristics of Microplastics in Ice Sheets and Its Response to Salinity and Chlorophyll a in the Lake Wuliangsuhai. Environ. Sci. Resour. Util. 2021, 42, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Zhao, Y. Microplastics Pollution in Freshwater Sediments: The Pollution Status Assessment and Sustainable Management Measures. Chemosphere 2023, 314, 137727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Luo, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Xing, X.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, Y. The Rapid Increases in Microplastics in Urban Lake Sediments. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla-Pradhan, R.; Phoungthong, K.; Suwunwong, T.; Joshi, T.P.; Pradhan, B.L. Microplastic Pollution in Lakeshore Sediments: The First Report on Abundance and Composition of Phewa Lake, Nepal. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 70065–70075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fojutowski, M. Lake Sediments as Microplastic Sink: The Case of Three Lakes from Northern and Central Poland. Quaest. Geogr. 2024, 43, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdhani, H.; Maleni, R.; Eppehimer, D.E.; Abdunnur, A.; Rizal, S.; Ardianor, A. Microplastic Pollution in Waters and Sediments in a Lentic System: A Case Study in a Tropical Wet Urban Lake of Samarinda, Indonesia. Lakes Reserv. Sci. Policy Manag. Sustain. Use 2025, 30, e70008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cao, J.; Zhao, W.; Jiang, J.; Wu, H.; Du, C.; Deng, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhu, H.; Li, L. Unveiling the Co-Occurrence of Microplastics and Heavy Metals in Surface Sediments of Dongting Lake: Distribution Characterizations and Integrated Ecological Risk Assessment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wang, P.; Liu, S.; Wang, R.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, A.-X.; Deng, C. Global Patterns of Lake Microplastic Pollution: Insights from Regional Human Development Levels. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ockelford, A.; Cundy, A.; Ebdon, J.E. Storm Response of Fluvial Sedimentary Microplastics. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izhboldina, L.A.; Timoshkin, O.A.; Genkal, S.I. Atlas and Guide to Benthos and Periphyton Algae of Lake Baikal (Meio- and Macrophytes): With Brief Essays on Their Ecology; Nauka: Novosibirsk, Russia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Fu, D.; Lü, S.; Liu, Z. Interaction between Macroalgae and Microplastics: Caulerpa Lentillifera and Gracilaria Tenuistipitata as Microplastic Bio-Elimination Vectors. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2023, 41, 2249–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, N.B.; Villaro, C.G.; Koch, I.D.W.; Sundbæk, K.B.; Rasmussen, N.S.; Holdt, S.L. Adsorption of Microplastics to the Edible Fucus Vesiculosus and Possible Wash off before Food Application. In Proceedings of the 6th Congress of the International Society for Applied Phycology, Nantes, France, 18–23 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dodson, G.Z.; Shotorban, A.K.; Hatcher, P.G.; Waggoner, D.C.; Ghosal, S.; Noffke, N. Microplastic Fragment and Fiber Contamination of Beach Sediments from Selected Sites in Virginia and North Carolina, USA. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 151, 110869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrick, A.; Champeau, O.; Chatel, A.; Manier, N.; Northcott, G.; Tremblay, L.A. Plastic Additives: Challenges in Ecotox Hazard Assessment. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mato, Y.; Isobe, T.; Takada, H.; Kanehiro, H.; Ohtake, C.; Kaminuma, T. Plastic Resin Pellets as a Transport Medium for Toxic Chemicals in the Marine Environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001, 35, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Khare, S.K. Ecological and Toxicological Manifestations of Microplastics: Current Scenario, Research Gaps, and Possible Alleviation Measures. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part C 2020, 38, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annenkov, V.V.; Danilovtseva, E.N.; Zelinskiy, S.N.; Pal’shin, V.A. Submicro- and Nanoplastics: How Much Can Be Expected in Water Bodies? Environ. Pollut. 2021, 278, 116910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, A.L.; Kawaguchi, S.; King, C.K.; Townsend, K.A.; King, R.; Huston, W.M.; Bengtson Nash, S.M. Turning Microplastics into Nanoplastics through Digestive Fragmentation by Antarctic Krill. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani-Borges, B.; Meitern, R.; Teesalu, P.; Raudna-Kristoffersen, M.; Kreitsberg, R.; Heinlaan, M.; Tuvikene, A.; Ivask, A. Effects of Environmentally Relevant Concentrations of Microplastics on Amphipods. Chemosphere 2022, 309, 136599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadereev, E.S.; Lopatina, T.S.; Yaskelyainen, D.D.; Lyubimtseva, S.A. The Effect of Microplastics and Co-Occurring Toxicants on Survival and Life-History Traits of the Cladoceran Moina Macrocopa. Limnol. Freshw. Biol. 2025, 2025, 1083–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.