Abstract

This paper aims to provide an analytical assessment of country-level experience in moving towards agricultural decarbonization—from ideas around decarbonization measures to assessment of their potential, including evaluations of political goals and practical implementation success. This paper is based on 10-year cycle that highlights the main steps in building decarbonization awareness using an approach that can monitor, quantify, and evaluate the contribution of agricultural practices to climate change mitigation. This approach is based on a marginal abatement cost curve (MACC), which serves as a convenient visual tool for evaluating the effectiveness of various greenhouse gas emission reduction measures in agriculture, as well as climate policy planning. This study reveals the experiences to date and the main directions for developing the MACC approach, which serves as a basis for analyzing the potential of moving towards decarbonization in agriculture for a specific European Union Member state, i.e., Latvia. The results of the study are of practical use for the development of agricultural, environmental, and climate policies or legal frameworks, policy analysis, and impact assessment. Additionally, the findings are useful for educating farmers and the public about measures to reduce GHG and ammonia emissions.

1. Introduction

An analysis of statistics on world population changes and United Nations projections of population changes reveals that the demand for resources and emissions from the consumption thereof will be a long-term global problem. The growing population is stimulating global food demand, and to meet it, the amount of fossil mineral fertilizers used in agriculture in Latvia increased by 83% [1] between 2005 and 2024. In addition, the global population is projected to peak at a total of 10.3 billion at the end of this century [2].

An additional factor behind the increase in resource consumption is the convergence of global economic growth, with less developed regions maintaining a faster rate of economic growth compared with the developed world [3]. Global economic growth raises the need to assess options for mitigating this impact. Unfortunately, global economic growth is subject to significant externalities. The present research highlights two of the most important externalities: the continuing global industrialization process and the increasing demand for food [4]. Economic growth externalities continue to result in increased overexploitation of non-renewable resources, thereby leading to increased greenhouse gas emissions (greenhouse gases include carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide) into the natural environment, causing global temperatures to rise and contributing to a range of environmental degradation and social problems [5]. Identifying greenhouse gas emissions hotspots and selecting appropriate mitigation measures is a prerequisite for achieving carbon neutrality. Global monitoring data on the atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases (carbon dioxide (CO2)) show a significant increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration from 285 parts per million (ppm) in 1850 to 425.79 ppm in 2024 [6]. Under current economic growth trends, resource extraction and consumption are projected to increase by 119% between 2015 and 2050, from 84 to 184 billion tons per year, while greenhouse gas emissions are projected to increase by 41% [7].

The growth of the global economy has a significant impact on consumer food choices. Statistical evidence and projections point to a significant increase in meat consumption in regions of economic growth. The average global demand for beef, sheep, goat, pig and poultry meat, as well as milk and eggs, is projected to increase by 14% per capita between 2020 and 2050 and by 38% overall if consumer income and population growth trends continue at current rates [8].

The increase in global temperatures driven by greenhouse gases has already resulted in significant damage to the living environment, including species extinction, loss of biodiversity, drought, food insecurity, forest fires, ocean acidification, melting of the North and South Pole Glaciers and rising sea levels [9,10].

On 12 December 2015, 197 Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change unanimously agreed, at the Paris Climate Change Conference, to adopt the Paris Agreement, which sets out plans for global action to tackle climate change beyond 2020. Under the Paris Agreement, each country agreed to limit global temperature increases to less than 2 °C and to work on limiting global temperature increases to less than 1.5 °C [11]. By February 2021, 124 countries had declared their intention to become carbon neutral and achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050 or 2060 [12].

Thus, the transformation of the traditional economy towards a climate-neutral or net-zero economy has become a global initiative and a feature of the 21st century. The terms carbon neutrality and net-zero carbon emissions are frequently referenced in climate change mitigation policy documents. The terms are used to describe the mitigation actions that are included in the policy documents and the measures taken. A correct understanding of these terms is the basis for ensuring coherent national action to mitigate climate change. Carbon neutrality refers to the point at which CO2 emissions into the atmosphere, in per unit terms, are offset by sequestration over a given period, thus achieving a CO2 balance in the atmosphere. Carbon neutrality is a term describing a system in which all carbon emitters and sinks participate. The cooperation between emitters and sinks results in a balance of CO2 emissions, thus having no impact on climate change [13].

The term net-zero carbon emissions has a different meaning, as it is the responsibility of all CO2 emitters to reduce their emissions into the atmosphere. This means that every single resource consumer must develop a Net-Zero Carbon Emissions Resource Use System, which involves storing or sequestering all the emissions from economic activities into the atmosphere [13,14]. The two theoretical terms referred to in policy documents allow us to explain the EU’s overall goal of achieving climate neutrality, i.e., a net-zero carbon economy by 2050. This goal is at the heart of the European Green Deal and, through the European Climate Act, is a legally binding target for all EU Member States [15].

At the end of 2023, around 145 countries, including China, the European Union, the United States of America and India, had announced or were considering net-zero targets. These targets are key to reducing global carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050 and 2070 [16].

The topic of net-zero targets in scientific discussion emerged in the first decade of the 21st century, when scientists began to focus on the close relationship between the total amount of anthropogenic CO2 emissions and global temperature changes [17,18]. In 2014, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) highlighted this finding, along with the implication that limiting global temperature change to a given level requires a point at which net additions of CO2 into the atmosphere reach zero [19]. This posed a challenge for many countries regarding how to develop and implement ambitious net-zero targets so their national economies could meet global commitments and achieve national greenhouse gas reduction targets.

A comparison of adopted net-zero targets and analysis of existing experience [20] reveals that when developing plans to reach net zero emissions, countries face a number of critical decisions and are required to answer to several key questions. These include what exactly “net zero” means for them, how long it will take to get there, which sectors and greenhouse gases to focus on, and whether they will rely on capturing carbon or international cooperation to achieve their goals. The World Resource Institute [20] argues that, to maximize the contribution of net-zero targets to drive decarbonization in line with climate science, countries should consider the following recommendations: achieving net-zero emissions will require fundamental shifts in how society operates; net-zero targets should be comprehensive and cover all greenhouse gases and all sectors; governments should establish specific time frames for achieving targets; countries with the highest emissions and greatest responsibility and capability should adopt the most ambitious target time frames; separate targets should be set for GHG emissions reductions and net-zero or net-negative emissions; and countries should transparently communicate their net-zero targets.

To obtain the answers to specific questions and implement recommendations related to net-zero targets, close communication and cooperation between policymakers and scientists is essential. This leads to central theme of this study and its focus on key analytical steps and country-level experience in assessing the potential of agricultural decarbonatization measures, from initial conceptualization to final potential quantification. The course of this study is guided by two research questions: (1) what is the utility and effective application of marginal abatement cost curves (MACCs) as a supportive tool for evaluating the economic and practical success of implemented agricultural decarbonization measures? (2) To what extent do the analytical assessments of agricultural decarbonization potential—including the use of MACCs—align with and successfully inform practical implementation strategies and policy outcomes across different countries?

2. Materials and Methods

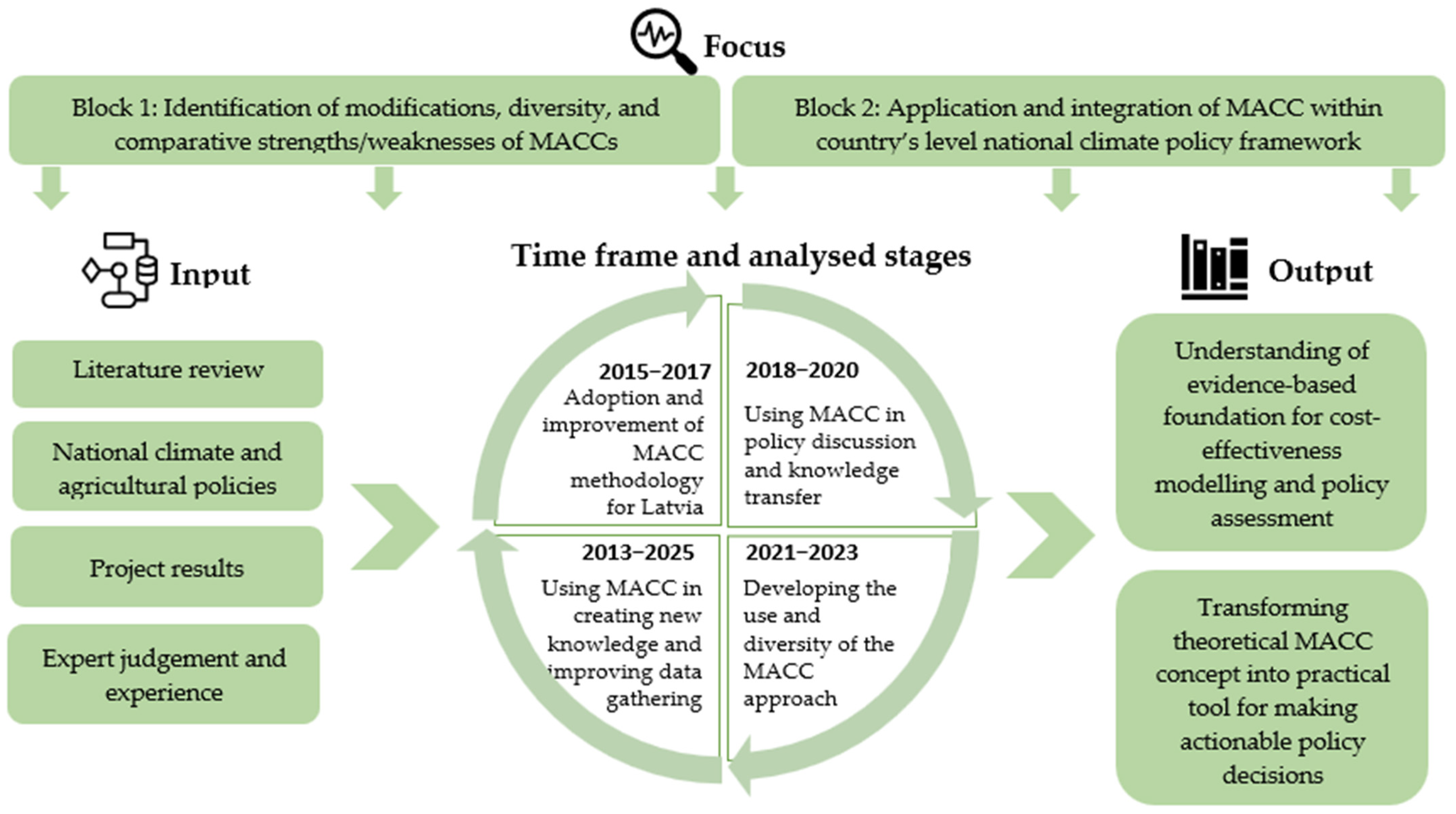

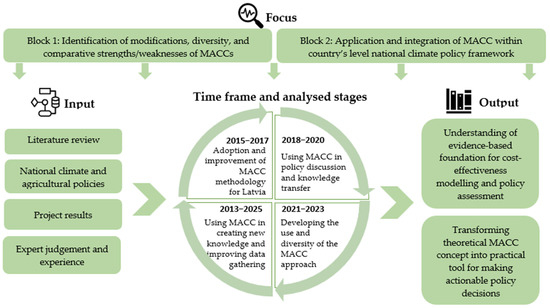

The contribution of agriculture to climate change mitigation and the achievement of the climate and environmental objectives set by the European Union depends on how successfully and to what extent measures to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are implemented in practice, as well as on how their impact is assessed and monitored. The subject of this study is MACC—a tool used for planning and implementing agricultural decarbonization strategies. The purpose of this paper is to provide an analytical assessment of country-level experience in moving towards agricultural decarbonization:

- Block 1: MACC theoretical and historical analysis starting from early 1990s summarizes, describes and reveals the modifications and diversity of MACCs;

- Block 2: MACC case study application focuses on a case study illustrating different uses and levels of integration of MACC into national climate policymaking processes, serving as a demonstration of a full-cycle approach towards carbon neutrality.

Table 1 summarizes the two blocks of this study and the main methods, approach, focus, and outcome of each thematic block.

Table 1.

Main methods, approach, focus and outcome of each thematic block of study.

In order to understand the scope and possible nuances of using the MACC tool in thematic Block 1 (MACC theoretical and historical analysis), we have analyzed the existing modifications and diversity of MACCs from the early 1990s to 2018 that can be considered as the most active time in the use of the MACC approach. For the literature search, SCOPUS and Web of Sciences databases were used. Specific keywords and combinations were used in the literature search, like “marginal abatement cost curve”, “MACC”, “abatement cost curve”, and “cost-effectiveness modelling”. Additionally, from the initial literature screening, only papers that responded to one of the following criteria were selected for analysis:

- The paper must present a marginal abatement cost curve (either measure-explicit or model-derived) and must focus on GHG abatement.

- The paper must provide clear description of the modelling methodology.

The results of this literature review highlight the historical development of MACCs, the diversity of their usage, as well as the strengths and weaknesses of expert judgement-based MACCs and model-derived MACCs. This thematic block is built on a comprehensive evaluation of MACC development over time from the scientific literature. This overview helps to determine how MACC has evolved over time, which sheds light on the limitations, advantages, and policy integration opportunities of the model. The described evolution and change provide a transition to Block 2 of the study, which evaluates the different stages of using the MACC approach in a specific country example over a longer period of time.

In thematic Block 2 (MACC case study application), we focused on a 10-year period (from 2015 to 2025) and identified the main stages in the development of the MACC approach. These development stages, as well as the relevant time periods, are summarized in Figure 1, which reflects the study time frame and the main issues analyzed in this research. Each analyzed stage reflects specific research results [21,22,23,24,25,26] that sequentially follow from each other and form a long-term vision of the different variations and results of using the MACC approach.

Figure 1.

Main stages in the development of the MACC approach as supportive tool in building a national pathway towards decarbonization.

The information summarized and analyzed in this thematic block highlights the experience of a full-cycle approach (i.e., from the initial technical construction of MACCs, through their integration into political plans, to later extensions for CAP funding and ecosystem services) towards carbon neutrality by utilizing project results from Latvian climate policy initiatives and strategic actions for advancing MACC research and policy applications.

3. Results

3.1. Modifications and Diversity of Marginal Abatement Cost Curves

Cost curves have been used to help reduce energy consumption or emissions since the early 1980s [27]. Marginal abatement cost curves (MACCs) were first developed in the 1970s following the two oil price shocks, initially targeting reductions in crude oil consumption and, later, electricity consumption [28]. In response to the oil price crises of the 1970s, Meier [29] introduced the first cost curves for decreasing electricity consumption (measured in USD/kWh). These saving curves, also known as conservation supply curves, quickly became essential analytical tools for evaluating energy-efficiency improvements across various sectors, including transport, industry, and buildings [30,31,32]. Blumstein & Stoft [30] highlighted the connection between technical efficiency, production, and conservation supply curves, strengthening the theoretical basis of the instrument. Difiglio and co-authors [31] demonstrated how cost-effectiveness analysis can identify potential energy efficiency improvement reserves in transport. Rosenfeld and co-authors [32] developed an application for the building sector, systematically showing energy-saving potential and costs. The common approach of these sources is that they provide the methodological origins of MACC and show how cost curves became a widely used tool in energy efficiency policy. They were also widely applied to assess the abatement potential and costs of air pollutants like SO2 (USD/kt) [33]. The first carbon-focused curves, which utilized methods similar to those of earlier energy-saving cost curves, emerged in the early 1990s [34,35,36]. Jackson [34] adapted and conceptually developed the existing “least-cost greenhouse planning supply curve” approach and applied it directly for the first time to compare CO2 emission reduction technologies in the context of national energy systems. Mills and co-authors [35] introduced no-regrets strategies, emphasizing measures with negative or zero costs. Sitnicki and co-authors [36] demonstrated the applicability of MACC in transition economies, focusing on emission reduction opportunities in Poland. These authors demonstrate the transition of MACC from an energy efficiency tool to an early climate policy tool for reducing CO2 emissions. Over time, MACCs were applied to various areas, including the assessment of abatement potential and costs for air pollutants and water availability. Eventually, MACCs began to be used in the agricultural sector, where they involved qualitative judgements and more empirical methods [28].

Recently, researchers and policymakers focused on climate change mitigation have increasingly turned their attention to MACCs, mainly due to the influential work of McKinsey & Company. From 2007 to 2009, McKinsey released and published 14 cost curves for various countries, as well as developing a global cost curve, which significantly contributed to the prominence of this tool in climate policy discussions [37]. In the UK, MACCs have significantly influenced governmental climate change policy. This is highlighted in governmental reports that incorporate MACCs, like the UK Low-Carbon Transition plan. The UK Department for Energy and Climate Change (DECC) utilizes the Global Carbon Finance (GLOCAF) model, which is based on MACCs, to predict financial flows between different global regions. MACCs have also been applied in many other countries and regions, such as the Netherlands, Ireland, and the European Union [38], California (USA), and China [39]. Beyond these practical uses, MACCs have been applied in theoretical policy analyses of emission reductions and the impact of innovation [40,41].

Several agricultural engineering greenhouse gas emission (GHG) MACCs have been published over the past decade. The UK Government has commissioned a series of these studies as part of a broader economic analysis [42,43]. MACCs have also been developed for the agricultural sectors in Ireland [44], France [45], New Zealand [46], and China [47], as well as for the dairy sector in the Netherlands. The Danish and Belgian MACCs cover the entire economy, with Denmark currently updating its MACC for the agricultural sector. In Finland, GHG abatement costs have been calculated for various potential measures. Moreover, due to the context-specific nature of these estimates, recent MACCs also include uncertainty estimates [48]. Latvia developed MACCs in early 2018, with some preliminary results and the research approach available in 2016 and 2017 [21,22,23]. Lenerts and co-authors [21] identified the impact of fertilization efficiency on emissions—an essential prerequisite for assessing technical options in the MACC approach. Naglis-Liepa and co-authors 22] developed a farm typology specific to Latvia, which later became the basis for the cluster MACC methodology. Popluga and co-authors [23] presented the first sectoral MACC case study conducted in Latvia (agricultural crop production). The contribution of these scientists forms and provides a unique MACC methodology framework for Latvia.

MACCs have served as catalysts for the exchange of information between science and policy. Their findings have contributed to national carbon budgets and sector-specific policies, often highlighting key gaps in implementation. The ensuing debates have driven research and policy efforts to address these gaps by reducing barriers and enhancing national GHG inventories. This improvement ensures that mitigation efforts are captured, credited and incentivized effectively [49].

MACCs are commonly used to assess the cost-effectiveness of various emission reduction strategies. Nevertheless, their use and adoption differ greatly across regions, influenced by factors like economic development, data accessibility, technical expertise, and policy priorities. MACCs are most commonly used in Europe, North America, and China. Specifically, in Europe, their use is prevalent in the Netherlands, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Ireland, etc.

Studies that have assessed empirical MACCs in agriculture vary considerably in scope (source of emissions, gasses and mitigation options considered) modelling approaches, assumptions, and geographic scale and resolution [50,51]. De Cara & Jayet [50] demonstrated the use of MACC for the cost-effectiveness of European agricultural emissions, with particular emphasis on the importance of market response. In another study De Cara, Houze & Jayet [51] provided a spatial and sectoral analysis of emission sources, demonstrating the adaptation of MACC to different biogeographical conditions. This illustrates the empirical, model-based MACC approach in Europe and provides a context for comparison with Latvia. MACCs in agriculture can be classified into three main categories based on the modelling approach utilized [50]. Firstly, studies using microeconomic supply-side models incorporate a detailed representation of the technical and economic constraints that define the production possibilities at the farm level [51,52]. Secondly, MACCs obtained from studies using partial or general equilibrium models [53,54,55] consider the impact of market responses, such as changes in input and output prices on marginal abatement costs [55]. Golub and co-authors [53] modelized land use opportunity costs and global MACC integration in agriculture and forestry. Pérez Dominguez and co-authors [54] analyzed the impact of emissions trading schemes, illustrating how policy instruments change the form of MACC. Schneider and co-authors [55] demonstrated the use of models for US agricultural MACC scenarios. Market and price elasticity are significant in MACC modelling. These studies typically have broader geographic coverage but lower resolution compared to those based on supply-chain models. Thirdly, studies applying an engineering approach offer detailed [42,56,57], bottom-up evaluations of the carbon price required to incentivize the adoption of available technologies, along with their associated mitigation potential. As is already known, engineering studies assess the costs and emission reduction potential of specific technologies and create MACCs by combining the results of the technology level and offering a detailed view of possible measures. Beach and co-authors [56] provide a global-level MACC analysis for agriculture and forestry using an engineering approach, where specific technologies and practices (from soil management to livestock technologies) are evaluated; calculate marginal abatement costs for each technology; and determine the global abatement potential (for CO2, CH4, and N2O). Höglund-Isaksson and co-authors [57] focus on non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions in the EU, providing a technologically detailed assessment of CH4 and N2O emission sources, abatement costs and potential in MACC EU climate policy planning until 2050. Moran and co-authors [42] developed a technologically explained MACC for the UK ALULUCF sector, identifying dozens of specific technologies and management measures, calculating costs and potential, and providing sector-specific MACCs in Europe. These studies handle the effects of adopting new technologies or investing in environmentally friendly equipment more effectively than economic approaches. However, they do not model the competition and interactions among various mitigation options as transparently as economic models, which complicates the economic interpretation of the resulting abatement cost as an opportunity cost [50].

Marginal abatement cost curves (MACCs) are utilized in multiple sectors to assess the cost-effectiveness of emission reduction strategies and guide climate policy decisions. The sectors where MACCs are frequently applied include the energy sector, agriculture, the industrial sector, transportation, and residential and commercial buildings.

Experience from various countries demonstrates that multiple approaches can be used to analyze GHG reduction activities. The choice of methodology depends on the purpose of the assessment, the types of emissions considered, the types of costs calculated, and the information available.

Two different approaches are typically used to build these curves: an economy-oriented top-down model or an engineering-oriented bottom-up-model. The top-down analysis relies on a macroeconomic general equilibrium model, which provides an overall cost to the economy and is favoured for studying macroeconomic and fiscal policies. It also models the abatement potential and cost for individual technologies or measures, making it more useful for examining options with sectoral and technological implications. To ensure rigour and consistency, MACC appraisals must follow a commonly recognized methodology that accounts for agriculture, forestry, and land use (AFOLU) specificities. The results must also be transparent and comparable to those from other sectors, such as energy, transportation and manufacturing.

Marginal abatement cost curves vary widely in shape, differing in regional scope, time zone, included sectors, and the approach used for their generation. A MACC graph shows the cost associated with the last unit (the marginal cost) of emission reduction for different levels of emission abatement, typically measured in million or billion tons of CO2. To assess the marginal abatement cost, a baseline without CO2 constraints must be defined for comparison. MACCs allow analysis of the cost of the last abated unit of CO2 at a specified abatement level and provide insights into the total abatement costs through the area under the curve. Average abatement costs can be determined by dividing the total abatement cost by the total amount of emissions abated. Based on the methodology used, MACCs can be categorized into expert judgement-based and model-derived curves.

Expert judgement-based curves evaluate the cost and reduction potential of each abatement measure based on informed opinions, whereas model-derived curves are calculated using energy models. MACCs are particularly popular with policymakers due to their straightforward presentation of the economics of climate change mitigation. Policymakers can easily identify the marginal abatement cost for any given total reduction amount and, in the case of expert judgement-based curves, can also see the specific mitigation measures responsible for the reduction in CO2 emissions [27]. Previous discussions have identified that MACCs, like most things, have their pros and cons. These are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Strengths and weaknesses of expert judgement-based and model-derived MACCs.

Unlike top-down models, which encompass endogenous economic responses across the entire economy, bottom-up energy models are partial equilibrium models focused solely on the energy sector. Bottom-up models can be either simulation or optimization models, achieving partial equilibrium by minimizing system costs or maximizing consumer and producer surplus. In comparison to top-down models, bottom-up models provide more detailed representation of energy technologies throughout the transition from primary to useful energy. Top-down models, on the other hand, depend on substitution elasticities, which are primarily estimated from historical rates and assumed to remain valid over time [27].

To leverage the strengths of both bottom-up and top-down approaches, a practical alternative is to first use a bottom-up model, which provides the necessary technological detail, to create a consistent MACC. Index decomposition analysis can then be applied to the results of the energy system model to attribute emission reductions to specific changes in the energy system. This approach allows identification of the measures responsible for emission reductions while maintaining a coherent framework capable of considering system-wide interactions. This method significantly enhances the usefulness of MACCs for policymakers, addressing several shortcomings of existing approaches while remaining easy to understand.

In summary, this review of MACC modifications and applications highlights a gap in the existing international literature: while many studies focus on MACC in specific sectors or on modelled calculations, very few explore the longitudinal, full-cycle evolution of MACC development within a single country, and few integrate MACC into the pathways of actual policy implementation. This study expands current understanding by offering a unique, ten-year analysis of how MACC has been adapted, expanded, and implemented in Latvia. In contrast to previous compilations, this research shows how MACC can evolve from a purely analytical tool to a strategic system for the decarbonization of agriculture. Thus, the Latvian case provides original insights into the methodological innovations required for agricultural systems, the institutional and data requirements necessary for the effective integration of MACC into national policy, and the added value of MACC expansion beyond greenhouse gas reduction, including additional social and environmental benefits. These investments provide internationally relevant insights for countries seeking to develop comprehensive, evidence-based decarbonization pathways for agriculture.

3.2. Historical Insights into Experience of a Full-Cycle Approach to Carbon Neutrality

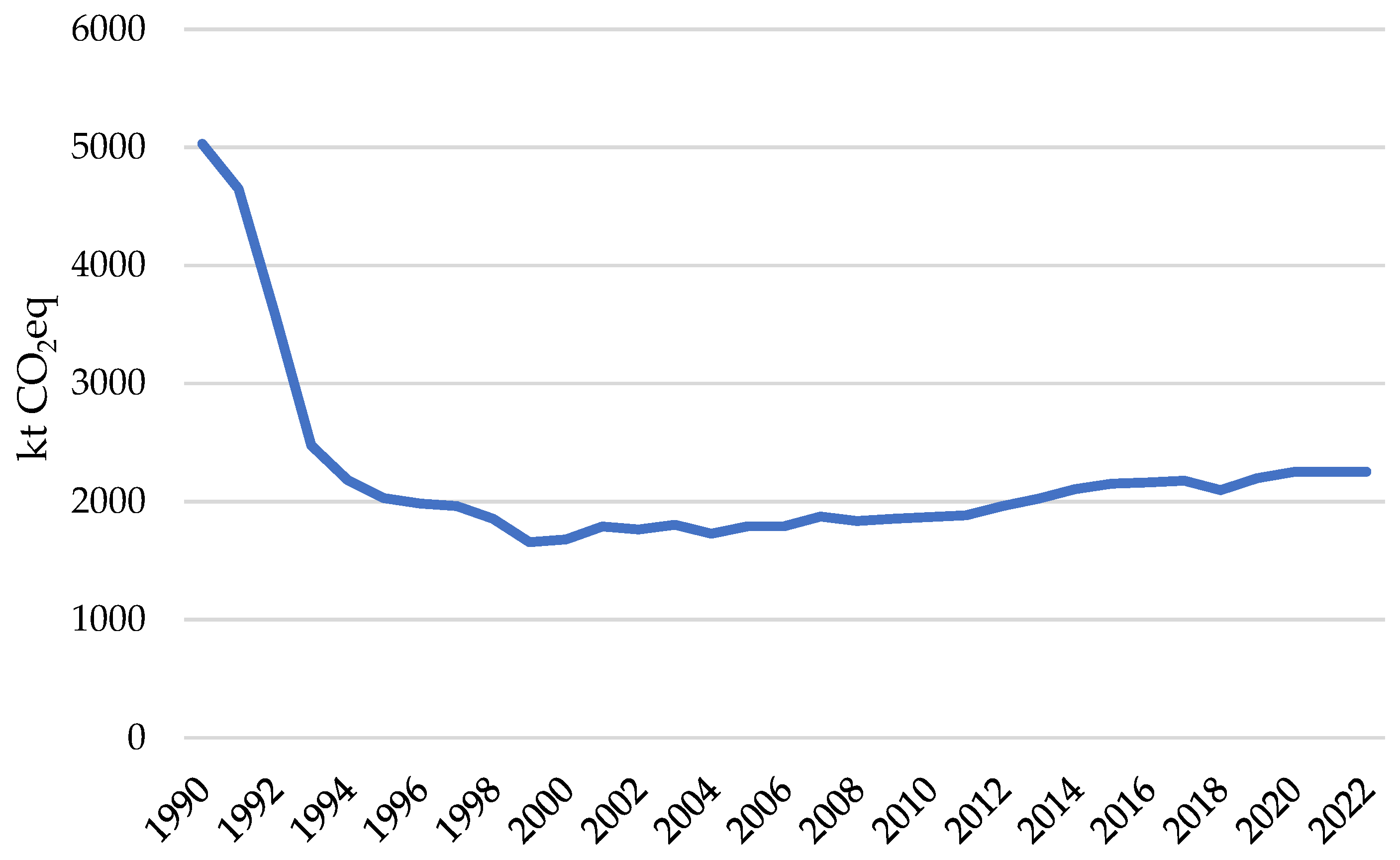

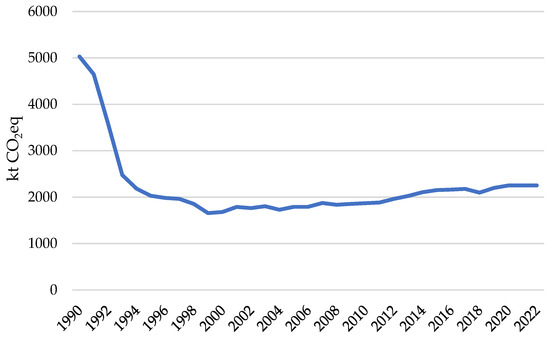

In the middle of the last decade, climate problems were not considered urgent for Latvian society, because the country was considered very green due to its low level of industrialization and low population density. In Latvia, climate problems became part of the political agenda later than in other parts of the EU because in 1990, the reference period for policy documents, Latvia was still occupied by the USSR and had an economically unsound planned economy that disintegrated immediately after the USSR collapsed. As a result, Latvia ceased producing products that were non-competitive outside the USSR in energy-inefficient factories and plants; moreover, farming no longer needed to be performed on the collective farms that were established as a result of forced collectivisation. Naturally, alongside the decrease in energy consumption and number of livestock, as well as the change in ownership that led to the restructuring of the economy and the conversion to the Western model of farming, GHG emissions also decreased significantly. In Latvia, after rapid privatization of various sectors, a new economy oriented towards the production, technological and investment patterns of western EU countries began to emerge. In agriculture, the descendants of farmers reclaimed their ancestral land and tried to find their place in the food market; this was successful, with both the output of agricultural products and the intensity of production slowly increasing. Consequently, GHG emissions began to increase (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Agricultural GHG emissions in Latvia, 1990–2022.

Therefore, after EU accession, climate problems became part of the agenda for policymakers. This meant that, in the following decade, the need for science-based expertise regarding measures for GHG emissions reduction increased.

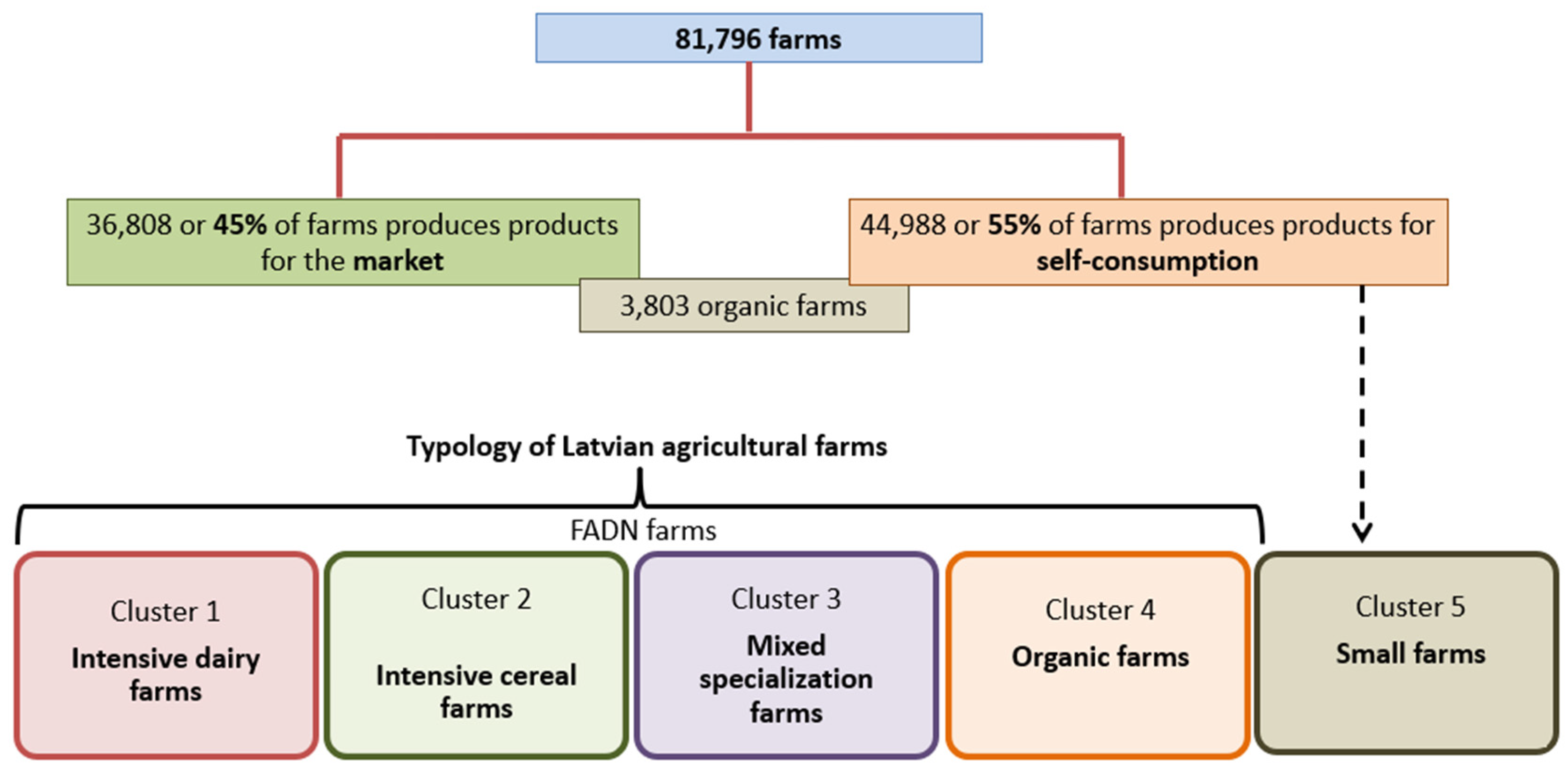

3.2.1. Adoption and Improvement of MACC Methodology for Latvia

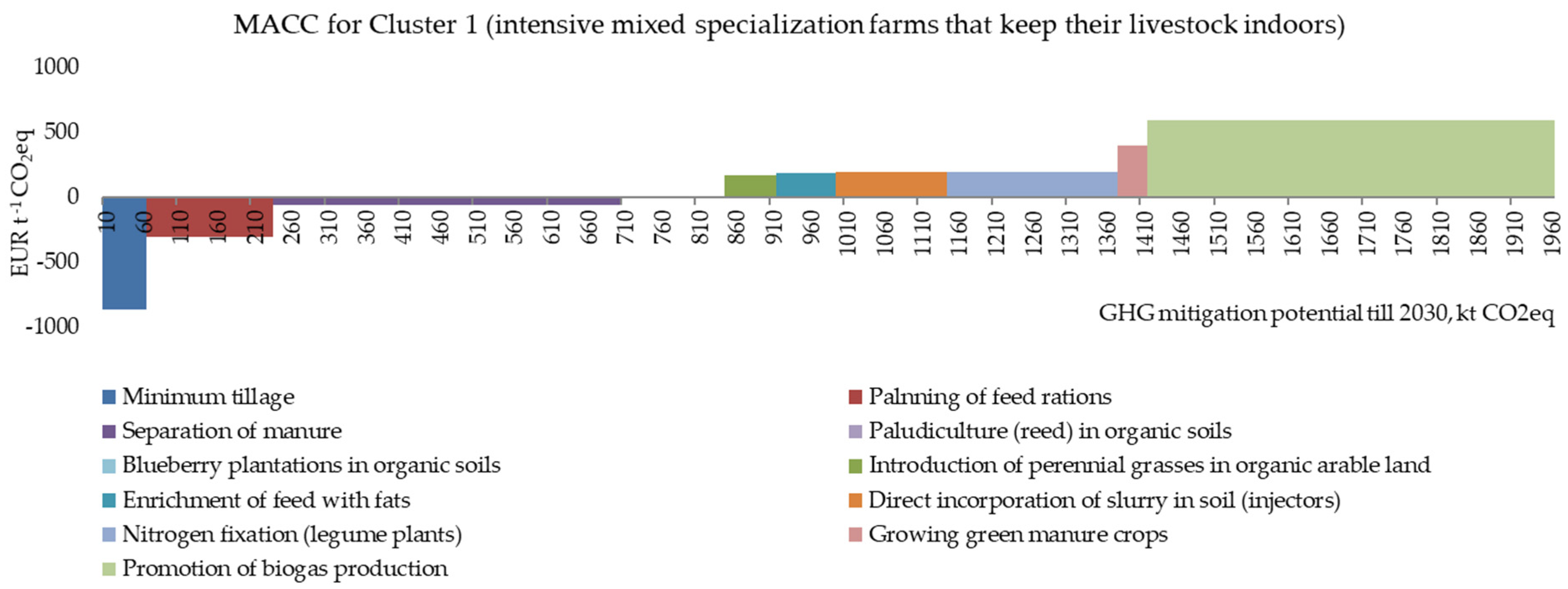

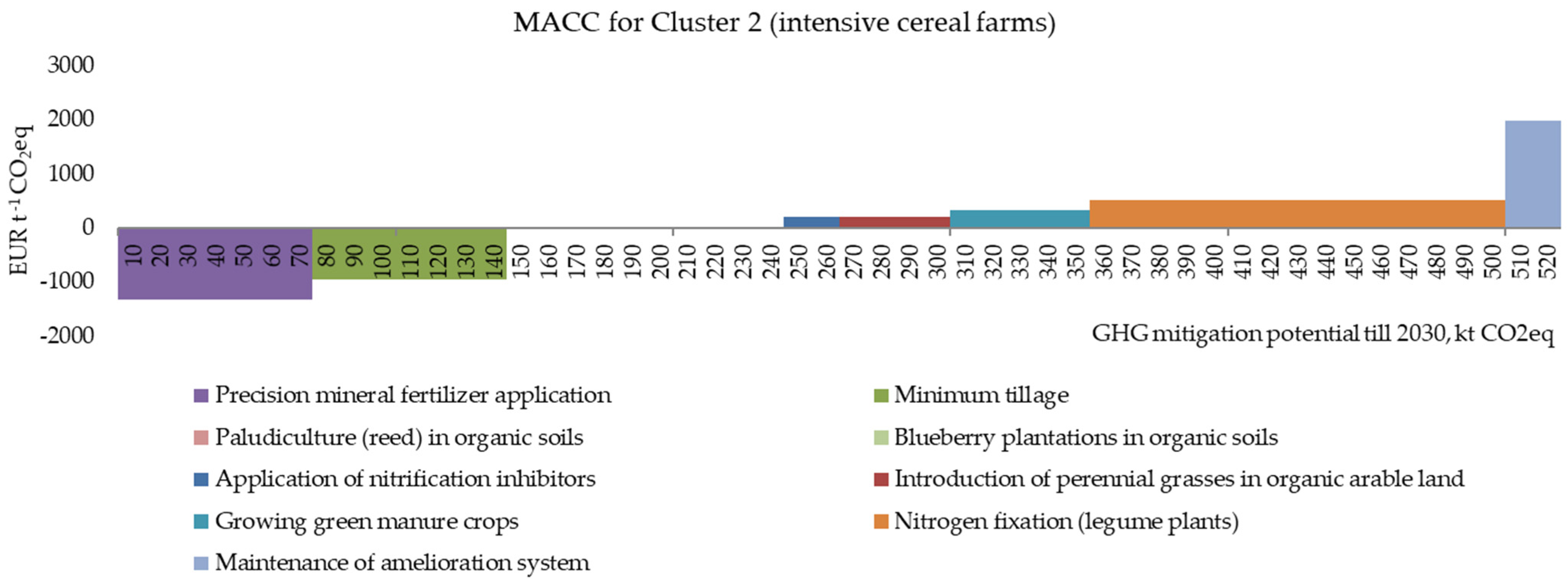

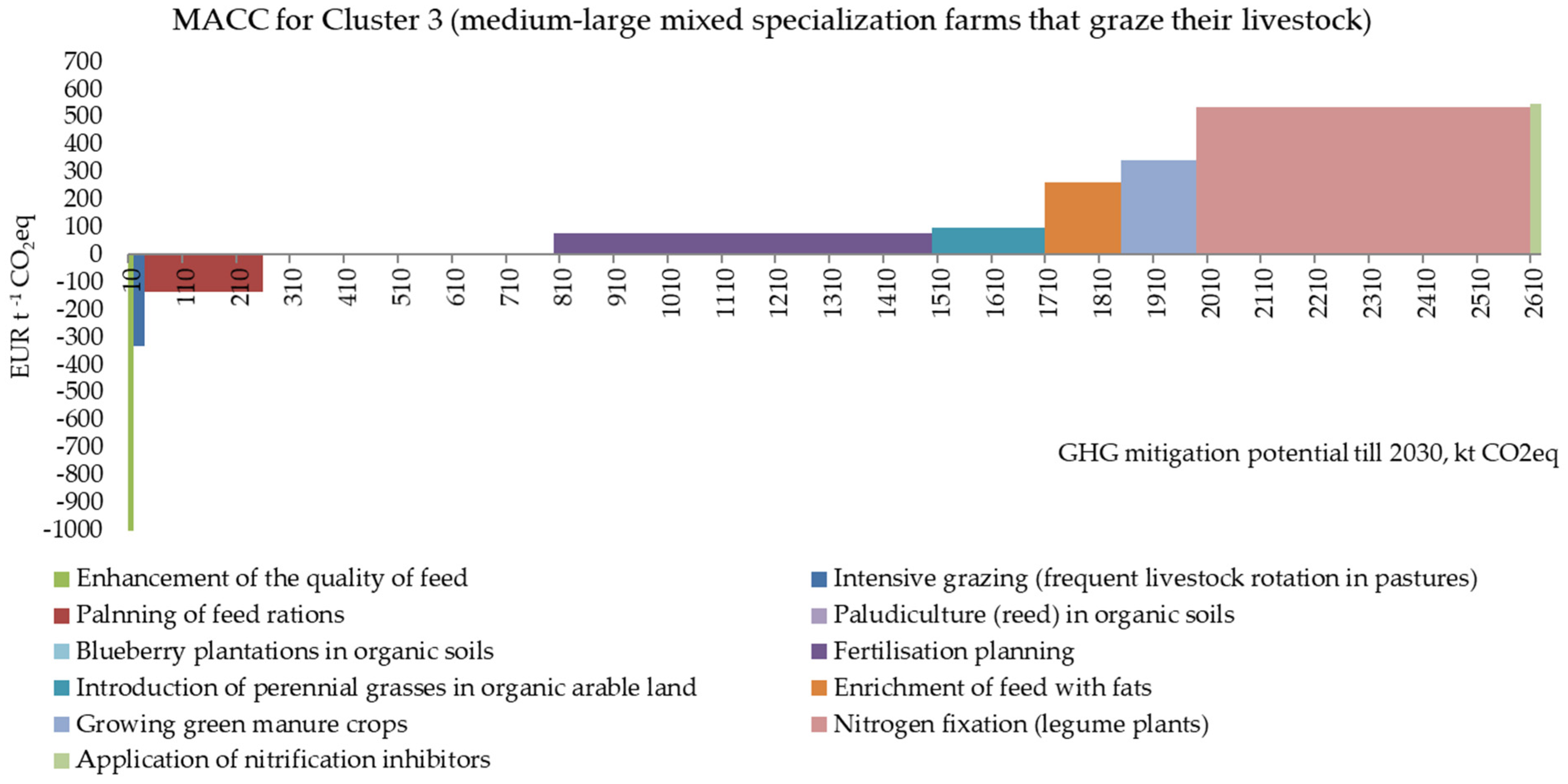

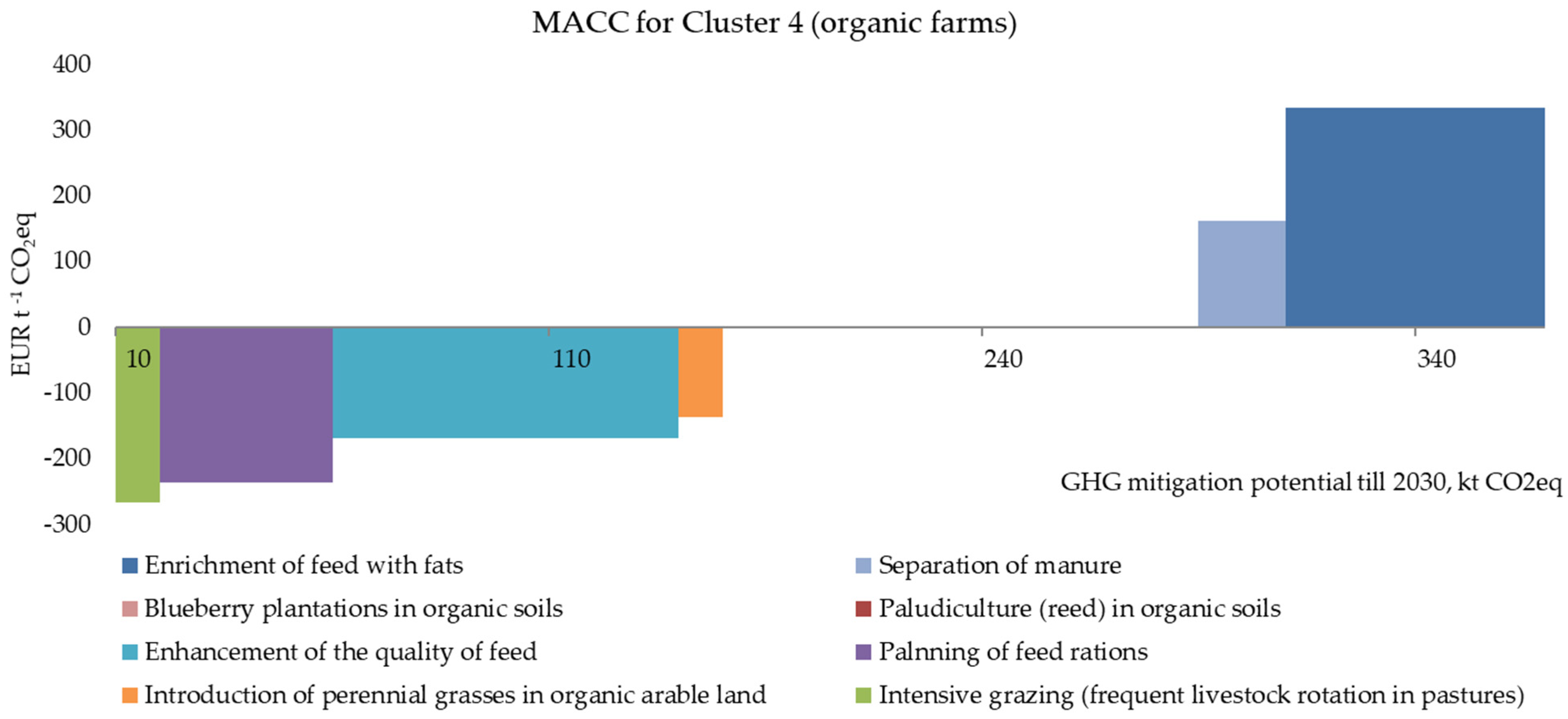

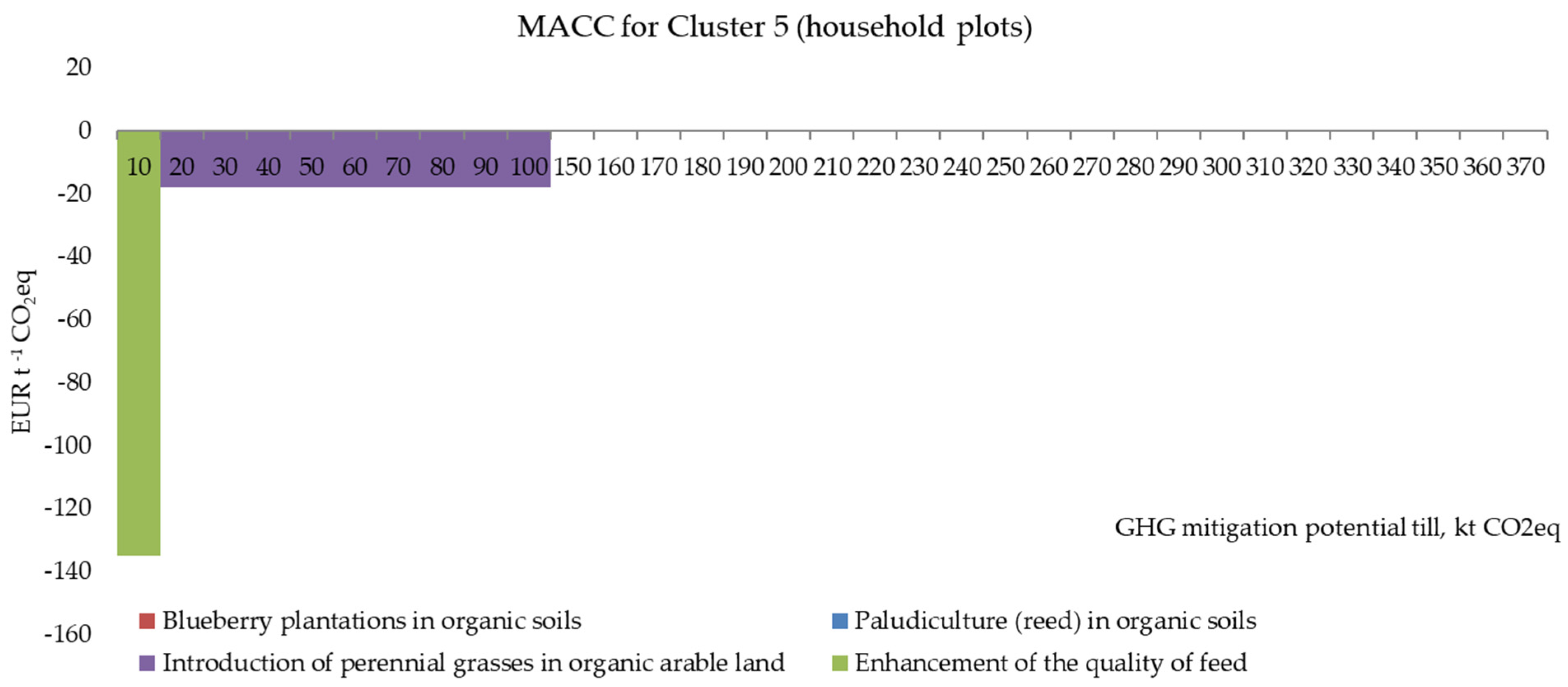

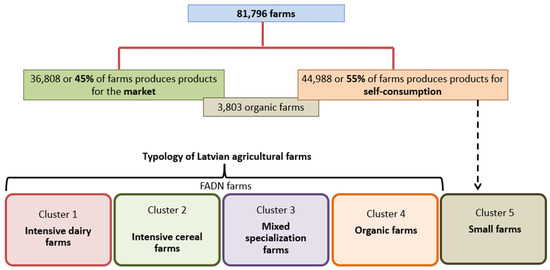

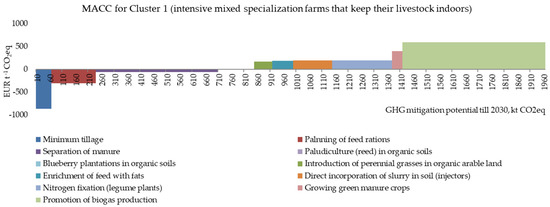

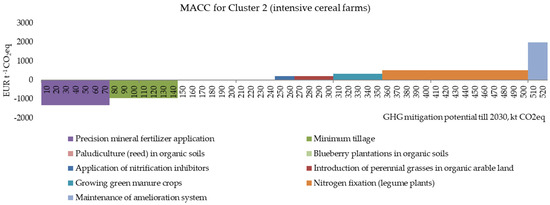

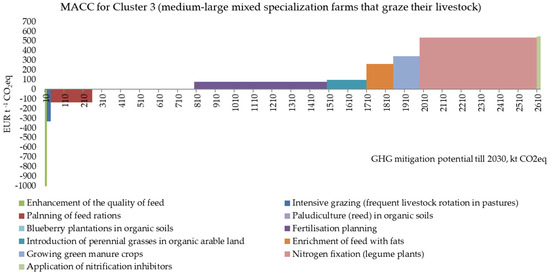

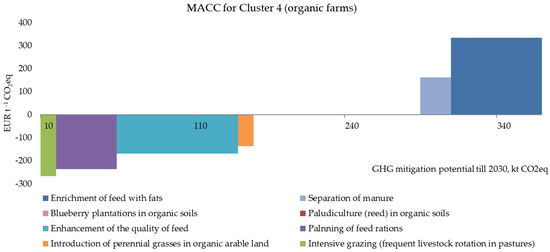

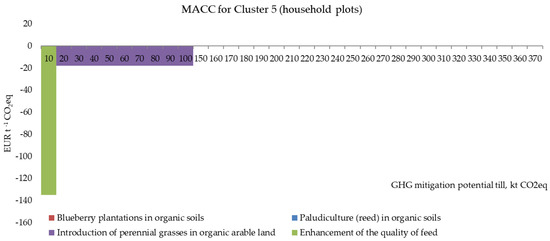

In 2015, the Latvian government launched the national scientific project “Value of Latvian Ecosystem and Its Dynamics in the Influence of Climate” (EVIDEnT) investigating the impacts of climate change on economic growth. One of the project’s components was the development of the first GHG MACC for the agricultural sector in Latvia. As part of the project, the Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Latvia held a MACC workshop aiming to share experiences and identify the best pathway for developing an agricultural MACC for Latvia. The results of the workshop and the insights of MACC designers were published in a research paper [49] describing the diverse experiences of using MACCs within the EU. The EVIDENT project developed a MACC for GHG mitigation measures in agriculture, which contained innovative features. From the very beginning, it was clear that MACCs would be used in policymaking. Previous experience indicated the benefit of using the Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN) database for evaluating MACC measures; however, the FADN database only covers the portion of the agricultural section affecting the agricultural market. To improve this situation, a typology of Latvian farms was developed via applying a clustering approach [22] (see Figure 3). The result was a MACC for five types (or clusters) of farms characteristic of Latvia [23] (see Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8).

Figure 3.

Results of typology of Latvia agricultural farms and farm types included in MACC analysis.

Figure 4.

MACC for Cluster 1 (intensive mixed specialization farms that keep their livestock indoors).

Figure 5.

MACC for Cluster 2 (intensive cereal farms).

Figure 6.

MACC for Cluster 3 (medium-large mixed specialization farms that graze their livestock).

Figure 7.

MACC for Cluster 4 (organic farms).

Figure 8.

MACC for Cluster 5 (small farms).

It should be noted, however, that this approach is itself time-consuming and adds significant complexity to the construction of a MACC, as data from various databases needed to be harmonized in order to overcome potential representativeness problems. Nevertheless, the inclusion of personal farm plots and organic farms in a MACC actually only increased MACC coverage by a negligible 3%, i.e., the GHG reduction potential increased by 3%.

The results of farm clustering showed that each farm cluster has its own potential and role in reducing GHG emissions and this approach allowed authors to draw specific conclusions relevant for agricultural and climate policy design. Firstly, it is clear that if policy support measures are proposed, the focus is on intensive farms, which are usually economically stronger. In later discussions, the owners of organic and small farms pointed out that they were denied specific support to develop their farms. In other words, the farmers felt penalized for already being less GHG-intensive. Secondly, the number of measures that could be defined as suitable for a certain type of cluster increased. This made the calculations more meaningful and more specific to farming practices in Latvia [21]. Thirdly, the MACC that was constructed became a platform that enabled more detailed discussions with farmers’ associations, policymakers and various authorities. What became clear in the selection of measures was that the measures not only have a positive impact on GHG emissions reduction but also provide other environmental or economic benefits. To verify this, an integrated impact assessment of the GHG emissions reduction measures included in the MACC was performed [22]. It was found that climate actions predominantly had an impact on the strategic economic benefits of farms, as well as bringing additional environmental benefits to society. Overall, it should be noted that the use of MACCs in assessing agricultural GHG emissions was successful, which encouraged further activities. In addition to GHG emissions reduction, the problem of increased C (carbon) sequestration and the interaction between land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) and agriculture was also a major challenge. These were the key tasks for constructing the next MACC.

3.2.2. Developing the Use and Diversity of the MACC Approach

The MACC for agricultural GHG emissions mitigation measures developed as part of the national research programme EVIDEnT were further supplemented with two new measures —“Paludiculture (reed (for construction)) on arable land on organic soils” and “Establishment of perennial plantations (bush blueberry) on organic arable land”—which related to land use and land use change. In addition, 23 previously analyzed measures were revised and analyzed with regard to their interaction with LULUCF. Overall, most of the measures had a neutral impact on each other (12 measures). Only three measures had a positive impact on both sectors, which means that both sectors contributed to GHG reductions. For two measures, the impact was unclear due to the paucity of research on them. For six measures, a negative interaction was found, mainly due to the fact that an increase in green mass in the agricultural sector leads to additional emissions, while an increase in green mass in the LULUCF sector leads to an increase in CO2 sequestration. This research [25] found that some of the measures included in the updated MACC, in addition to having GHG emissions reduction potential, also have CO2 sequestration and C storage potential. Therefore, an assessment of the CO2 sequestration and C storage efficiency of the measures was performed.

In Latvia, the next stage of using MACCs is associated with the European Commission’s Clean Air programme for Europe, whose legal basis is Directive 2016/2284. The directive sets strict anthropogenic emission ceilings for Member States for the main pollutants—sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxide, non-methane volatile organic compounds, ammonia and fine particulate matter (PM2.5)—for the periods from 2020 to 2029 and beyond 2030. In addition, Article 6 of Directive 2016/2284 requires Member States to develop and submit their national action plans to limit air pollution to the European Commission by 1 April 2019. An action plan must be updated at least every four years or more frequently if, according to the annual emissions report, the targets for reducing emissions from air pollutants are not met or are at risk of not being met. Given that 86% of the total NH3 emissions in Latvia in 2016 were attributable to agricultural production, measures need to be implemented in the agriculture section reduce air pollution. A MACC was suitable for this purpose, resulting in an ammonia MACC designed for agriculture. The research [26] adapted an already designed MACC for ammonia emissions abatement measures and constructed a new MACC. The research analyzed 17 ammonia abatement measures, focusing on the efficient use of nitrogen (N) fertilizers, efficient off-site manure management, and the development of organic farming. The research identified the impacts and cost-effectiveness of the measures on reducing ammonia emissions and published the results [21]. In addition, it is important to note that the measures and approach analyzed were incorporated into the policy document “Air Pollution Reduction Action Plan for 2019–2030”.

3.2.3. Using MACC in Policy Discussions and Knowledge Transfer

In addition, as preparations for the new European Union financial programming period (2021–2027) began, there was a need for a deeper and more detailed understanding of practical implementation constraints and solutions for GHG and ammonia emissions abatement measures. Given the commitments of Latvia in relation to the EU GHG and ammonia emissions abatement targets, it is important to identify the necessary improvements in data inventory and knowledge accumulation, so that the impacts of GHG and ammonia emissions abatement measures are included in GHG and ammonia emissions inventory reports. Basically, the MACC initiated a discussion between scientists, farmer lobby organizations, farmers, consultancy services, and policymakers. During the project, nine interactive workshops were held, bringing together more than 160 participants. The purpose of the workshops was to build a common understanding (among farmers, scientists, agricultural, environmental, and climate policymakers) regarding GHG and ammonia abatement measures in agriculture, as well as to identify potential constraints and requirements for practical implementation. The project team presented 20 GHG and ammonia abatement measures to the workshop participants and held discussions on positive and negative experiences and technological, environmental, social, and economic constraints and solutions to implementing the measures. The interactive workshops contributed to the farmers’ understanding of the nature of GHG and ammonia abatement measures and their suitability for various types of farming, as well as identifying concrete actions for their implementation. One important area of application of the MACC for Latvian agriculture was the opportunity to improve national GHG inventory reports. A major challenge was to identify new measures that could be integrated into policies and make the national GHG inventory report more realistic. The IPCC sets strict guidelines (2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories) for drawing up a report, including a requirement for reliable and verifiable data. In Latvia, the challenge was incomplete livestock feed statistics, which led to the use of relatively old data from the feed catalogue. These were the basic challenges related to constructing an agricultural MACC for Latvia.

Unfortunately, the project was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which prevented the collection of sufficiently extensive and reliable data on changes in cattle feed consumption. At the same time, a new approach was designed for reducing both ammonia and GHG emissions. The project designed six new feed ration models, each comprising a feed recipe and ration for a particular lactation phase of cows. The models provide several benefits, including improved animal welfare, higher productivity, and reduced GHG and ammonia emissions, depending on the situation in the country [24]. The measures complemented the updated GHG MACC and ammonia MACC. However, there are some indications that sustainable agricultural production needs in Latvia should be shifted towards a more integrated and circular pattern, taking into account the current geographical, biological, social, and economic considerations [22]. The collected information was the basis for a discussion on a Strategic Plan for the Common Agricultural Policy of Latvia for 2023–2027 (CAP SP), the National Climate and Energy Plan 2021–2030 (NECP), and the Air Pollution Action Plan 2020–2030. In Table 3, the authors have summarized ammonia- and GHG emission-reducing measures that were included in national policy documents where decisions were made using results of MACC analysis.

Table 3.

Internalization of GHG and ammonia measures into agricultural policy plans.

The scientifically justified GHG and ammonia abatement measures posed significant challenges for both policymakers and farmer lobby organizations. On the one hand, the measures were essential for the implementation of the EU Farm to Fork strategy and the National GHG and Air Quality Commitments. On the other hand, it was difficult to link the measures to specific types of support. Policymakers had to design a mechanism for implementation and control of the measures, as they had to ensure that public funding was used properly. However, this control mechanism should not become too bureaucratic and burdensome for farmers, which would undermine their involvement in the implementation of the measures. The influence of lobby organizations, which wanted to change the intensity of implementation and eligibility criteria for the measures and increase the amount and intensity of financial support, should also be taken into account. In light of the above, a new Strategic Plan for the Common Agricultural Policy of Latvia for 2023–2027 was drawn up. This document did not satisfy anyone and was therefore considered to be a good trade-off. At the same time, a question arose as to what extent the national CAP Strategic Plan is able to influence climate policy goals. Modifying the MACC approach also makes it possible to analyze current GHG abatement measures. The most important incentive for farmers to make changes on their farms is the availability of public funding to implement the measures. At the same time, the availability of such funding also provides opportunities for requesting information on the effect of GHG measures or for documenting their effects.

Therefore, the targets set by the National Energy and Climate Plan for 2021–2030 have mainly theoretical potential, and the measures and targets set by the Strategic Plan for the Common Agricultural Policy of Latvia for 2023–2027 (CAP) are measurable. Unlike the previous versions of the MACC, this one does not consider the marginal cost for farmers to implement the measure but the relative public cost (CAP funding) per ton of GHG (CO2eq) emissions reduced. The CAP targets, the assumptions of previous MACC projects on changes in the characteristics of emissions during the implementation of a measure, and the current IPCC characteristics were used to determine the potential for GHG abatement. In total, the GHG abatement measures supported by the CAP contributed to 516 ktCO2eq reductions over five years. For comparison, a GHG emissions reduction calculated for the first MACC project totalled 7653 ktCO2eq over a period of 13 years, which is five times less per year. It must be acknowledged that the CAP MACC calculations do not include investment measures. For several measures, the CAP targets are lower than the real results achieved through implementing the measures. It is therefore difficult to identify the real impacts of the current CAP measures on achieving the Climate Action targets. At the same time, the MACC shows how much a reduction of 1 ton of CO2eq costs the public, allowing the public to assess the effectiveness of a policy according to the interests of a particular social group. Although the scientifically selected and evaluated GHG abatement measures are predicted to be useful, the actual implementation may be more complex, significantly reducing the technological potential. However, this provides a basis for discussion and indicates tactical priorities in policymaking.

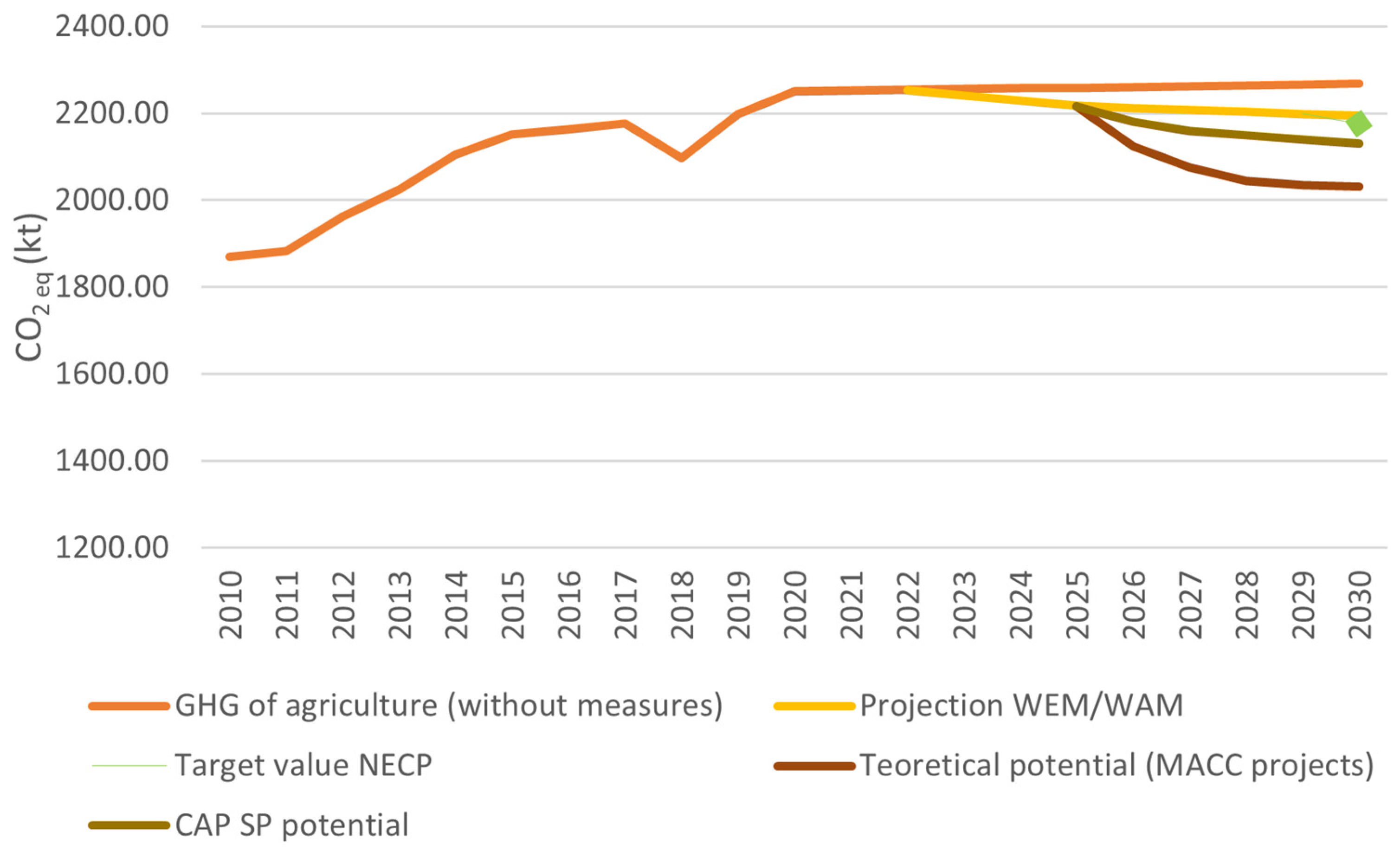

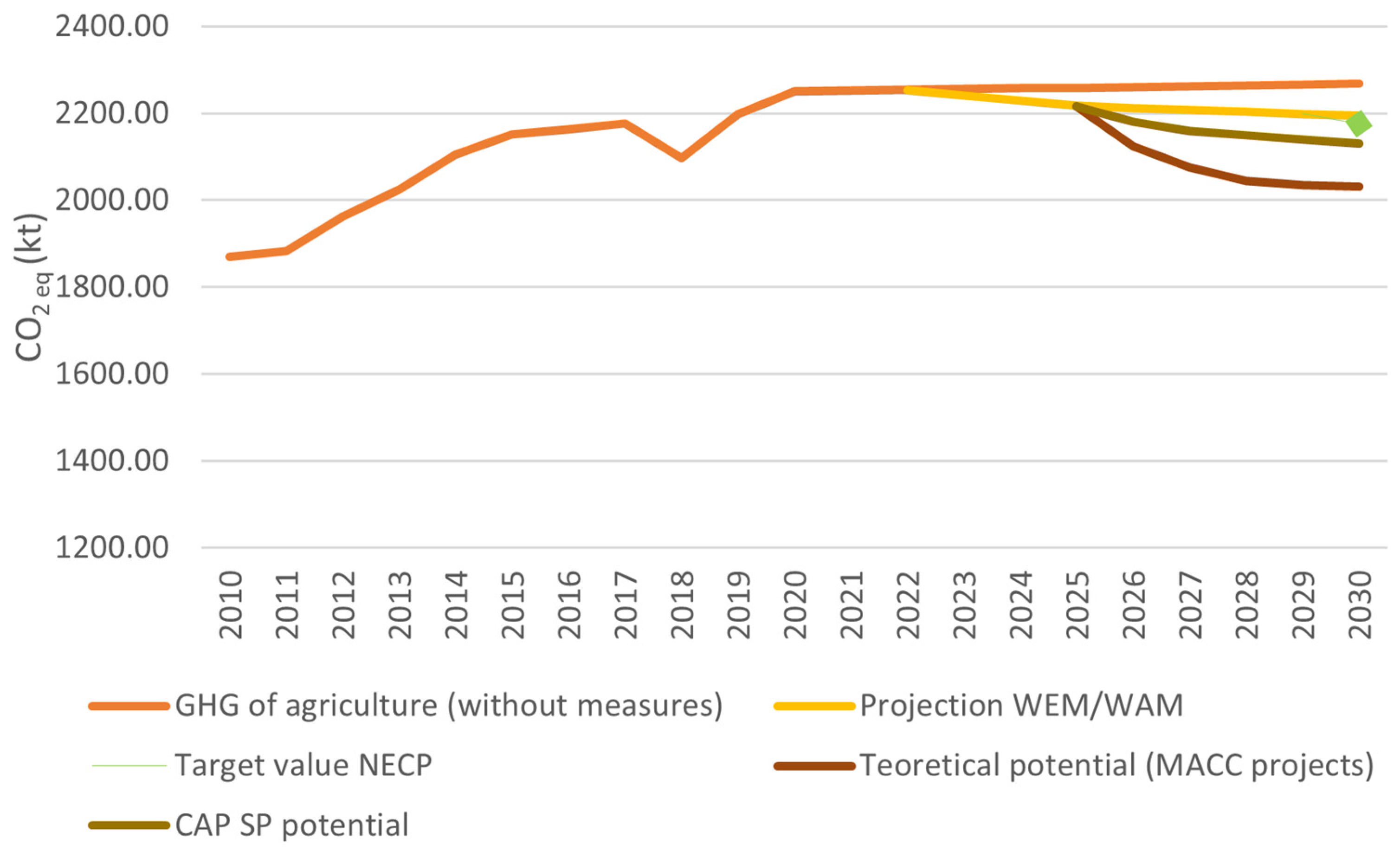

In order to demonstrate this, the authors have developed four scenarios (see Figure 9) for reducing agricultural GHG emissions, resulting from the most important documents influencing this process:

Scenario 1 GHG of agriculture (without measures): agriculture without GHG mitigation measures, which assumes that the general trends in agriculture continue as they are and there are no specific measures to reduce GHG emissions:

Scenario 2 Theoretical potential (MACC projects): the theoretical potential scenario, which assumes that all the previously described GHG mitigation measures are implemented and in accordance with a certain level of activity;

Scenario 3 Projection WEM/WAM: UN-reported scenario, which is the country’s officially reported GHG emission reduction projections to the UN, in connection with the Paris Agreement commitment;

Scenario 4 CAP SP potential: scenario, which assumes the implementation of the GHG mitigation measures included in the Latvian CAP Strategic Plan for 2020–2027.

Figure 9.

GHG reduction scenarios for Latvian agriculture.

Figure 9.

GHG reduction scenarios for Latvian agriculture.

The WEM/WAM projection that is based on Latvia 2024 Biennial Transparency Report [58] (with existing measures (WEMs)/with additional measures (WAMs)) is actually based on the measures mentioned in the NECP 2021–2030; however, due to the selected measures (a measure that provides for the use of biomethane is not included, as no funding has been allocated for it), as well as slightly different GHG savings methodologies, the results differ. Current policy measures do not ensure that the NECP target will be achieved. The NECP predicts that in 2030, Latvian agriculture will produce 2176.33 kt CO2eq; however, according to the WEM/WAM projections, agricultural sector will produce 2194.13 kt CO2ek, or 17.80 kt CO2eq more. The difference in forecasts is not large and it is possible to achieve the set target indicator. At the same time, if provided that the measures in the CAP SP 2020–2027 are actually implemented in the planned volume, the reduction could also be ensured by indirect measures or changes in agricultural indicators, such as a more rapid decrease in the number of dairy cows. The theoretical potential provides opportunities to review possible CAP SP 2020–2027 interventions by offering new support measures from the range of theoretical potential measures or increasing the target indicators for more popular and, at the same time, more effective GHG emission reduction measures. It is important to note that the inclusion of theoretically determined GHG reduction measures in official reporting documents is a challenge, as the situation before the measure, the effect of the measure’s implementation, and the magnitude of the activity must be clear. At the same time, the already incompletely listed CAP SP 2020–2027 GHG emission reduction potential would ensure the achievement of the NECP target indicator, provided that the effect of the measure and the activity indicators could be reliably determined and they would be available to international auditors.

3.2.4. Using MACC for Creating New Knowledge and Improving Data Gathering

Further development of MACC methodology proceeded with the inclusion of ecosystem services value in the evaluation of measures to reduce GHG and ammonia emissions and increase CO2 sequestration. MACC methodologies were prepared for the inclusion of ecosystem services value in the evaluation of measures to reduce GHG and ammonia emissions and increase CO2 sequestration. The use of ecosystem services value in MACC analysis has not previously been used in research and is considered an innovative approach. The inclusion of the social aspect in MACC analysis expands the scope of the analysis and can theoretically expand the applicability of MACCs for the development of agricultural, environmental, and climate policies or legal frameworks, policy analysis, and impact assessments.

Climate change mitigation measures do not/cannot in themselves create ecosystem services, but their implementation may have a positive or negative impact on the volume and value of the ecosystem services concerned. Primarily, the assessment of ecosystem services is carried out at the ecosystem level and creates international databases—when selecting a specific ecosystem, one can look for its association with a specific service and then determine the value of the service/service set. When using a similar approach for MACC measures, it is important to do the following:

- To identify, for each measure, the type of land management/biome/ecosystem to which it relates;

- To understand which services of the relevant ecosystem are affected by the measure if it is introduced (assuming that the impact is positive);

- To find the value of the ecosystem service(s) to be linked to the relevant ecosystem.

Regarding the use of the value of ecosystem services in MACC analysis, studies show that when there are negative costs (as in the case of ecosystem services, unless it is non-services (disservices)), caution is desirable in the use of MACCs [59,60,61,62,63], for the following reasons:

- The climate change mitigation potential of cost-negative measures may be overestimated without paying sufficient attention to measures that are less cost-effective;

- Negative cost measures are adequately assessed as the most cost-effective or income-generating, but their mutual ranking may not be correct due to the peculiarities of the mathematical algorithm in the method.

At present, there is no well-established approach to address this shortcoming of the MACC method, so it can be assumed that “negative cost measures” are perceived as equal in ranking. Because of this, the results from the MACC analysis with embedded ecosystem services should not be directly interpreted in the form of a ranking of the measure but instead as an indication of the existence and significance of goodwill (the result of the calculations changes significantly), drawing the attention of decisionmakers to the need to consider the inclusion of this type of value in policymaking processes, as well as to consider support for further research.

Table 4 provides a synthesis of the main stages in the development of the MACC approach.

Table 4.

Summary of contributions from the main stages in the development of the MACC approach.

4. Discussion

The use of the MACC approach in agricultural policymaking dates back to 2016, when the Latvian Ministry of Agriculture felt the need to actively work on reducing GHG and ammonia emissions. When analyzing measures that could promote GHG decoupling from agricultural production using MACC, researchers in Ireland [64], the UK [65], Spain [66], France [45], as well as elsewhere, the existing state of the art was characterized. Different approaches have been used to determine the emission reduction potential, which affects the interpretation and application of the results [67]. It is clear that MACC includes nation state-specific conditions, as is the case with the already mentioned UK’s or Ireland’s MACC, which focuses on national GHG reduction policies, similar to China [68] or some indicators of side effects such as livestock health measures [69]. The Latvian MACC, at least the first version, fits into the types of MACC used: it focuses on achieving national policy goals, uses a bottom-up approach, and uses IPCC methodology, which makes it relatively easy to adapt to national policy documents focused on farms (such as restrictions and support measures). It should be noted that Latvia is a relatively small country and the exchange of information between scientists, policymakers and non-governmental organizations is intense and fast [70]. Short and small MACC projects, only coordinated and supported by the Latvian Ministry of Agriculture, conducted focused research in accordance with the policy situation, both in defining tasks and in the formation of a discussion between policymakers and non-governmental organizations. Due to this, several types of MACC have been created in a relatively short time, both for reducing GHG and ammonia emissions, focusing on a certain agricultural sector and emission gas (methane), and for carbon sequestration, as well as for analyzing policy measures (CAP SP). Consulting and education are also significant advantages, because when thinking about climate policy, farmers are primarily interested in understanding which changes in existing practices are binding for them, how much they will cost, and how they will affect production as a whole. This is similar to how Teagasc in Ireland uses MACC to educate and train consultants [64]. For farmers, the cost and implementation can be determined both by the region [68], the intensity of agricultural production, and specialization. Therefore, the cluster approach introduced by the Latvian MACC provides a more accurate calculation of the emission reduction potential, as it takes into account several of the above considerations. A significant advantage of this approach is that the activity values used to determine the potential can be purposefully incorporated into policy documents as target indicators [71]. Thus, policy support measures are associated with financial support, and non-governmental organizations and farmers’ interest lobbies are active and are not going to stick to the theoretical price of carbon conservation, as was the case in the Latvian CAP SP. Moreover, farmers have significant inertia to continue existing farming practices, even on the basis of scientific evidence of the economic benefits of the measures, so they demand that sustainability be combined with agri-environmental requirements. This situation is not only characteristic of Latvia, but has also been observed in Germany [72] and, the authors assume, throughout the EU. This highlights principles that should be guided—if governments want to use GHG reduction measures as policy measures, then public funding needs to ensure cost-effectiveness and the extent to which public spending helps to meet decarbonization targets must be clarified. In meeting this principle, MACC can play a certain role, using limiting factors and data availability and their reliability. The measures included in the Latvian MACC are mostly based on sufficiently reliable data that meet the IPCC requirements, and thus are incorporated into official forecasts and policies. However, Latvia also faced certain challenges with regard to data availability, which are more related to non-EU countries; for example, in Africa or Asia [73]. Latvia lacks data on the true GHG reduction effect of the implemented measures, thus far reducing their ability to include the full reduction potential in policy documents. However, this is being worked on by integrating data submitted by farmers from various state databases into a single system [74]. It should be noted that the availability of data forces the choice of more advanced models like integrated assessment models [75] that can replace and complement the MACC for use in policy analysis and development.

5. Conclusions

An analytical assessment of Latvia’s experience in moving towards agricultural decarbonization by using MACCs as a supportive tool showed that MACCs can be used to help prepare strategic documents, including the Rural Development Programme, National Inventory Reports of GHG and Ammonia Emissions, National Energy and Climate Plan, and the Air Pollution Action Plan. MACCs have also been used as supportive tools for farmer education and as platforms for conversations with non-ETS sectors, and have provided necessary information for economic models of climate and agricultural development.

By tracking the main points in Latvia’s experience of developing a theoretical background via generating different versions of MACC analysis and transferring the gained theoretical knowledge into the political agenda and national targets, the following recommendations useful for other countries can be made:

- By recognizing the unique characteristics of different farm types (e.g., intensive, extensive, organic, etc.), the principle of targeted and equitable distribution of support should be implemented when developing climate-related policies and frameworks for support measures.

- Comprehensive assessment of GHG mitigation measures—considering their economic, environmental and social impacts, as well as understanding their multiple benefits—and robust data collection and analysis can serve as the background for data-driven policymaking.

- Facilitation of knowledge sharing, such as knowledge exchange between scientists, policymakers, farmers and other stakeholders, and capacity building, such as training and technical assistance to farmers to implement climate-friendly practices, can result in a more rapid transition to carbon neutrality.

This study’s retrospective insight into the role of MACC in policy planning and the nuances of using this tool allow the authors to identify future challenges in research aimed at achieving decarbonization goals. One important aspect that has not been taken into account so far in Latvia’s experience is the social aspects and the social costs of carbon. This highlights next development level of MACC approach and its integration in more broader models, like integrated assessment models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.P. and K.N.-L.; methodology, D.P.; validation, K.N.-L. and A.L.; formal analysis, K.F.; investigation, A.L.; resources, K.F., A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, K.F., K.N.-L., A.L. and D.P.; writing—review and editing, D.P.; visualization, D.P. and K.F.; supervision, D.P.; project administration, D.P.; funding acquisition, D.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was carried out with the financial support of the Latvian Ministry of Agriculture and the Rural Support Service project “Updating the marginal abatement cost curves (MACC) of Latvian agriculture for the decarbonization of agriculture”, research funding No. 25-00-S0INZ03-000034.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Statistical Database. Use of Mineral Fertilizers on Agricultural Crops. Available online: https://data.stat.gov.lv/pxweb/en/OSP_PUB/START__ENV__AV__AVZ/LAV020/ (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Economic Situation and Prospects 2024; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2024; 196p, Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/WESP_2024_Web.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Fukase, E.; Will, M. Economic growth, convergence, and world food demand and supply. World Dev. 2020, 132, 104954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, J. Meeting projected food demands by 2050: Understanding and enhancing the role of grazing ruminants. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.; Hamza, M.; Oliver-Smith, A.; Renaud, F.; Julca, A. Climate change, environmental degradation and migration. Nat. Hazards 2009, 55, 689–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pro Oxygen. Latest Daily CO2. 2024. Available online: https://www.co2.earth/daily-co2 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Hatfield-Dodds, S.; Schandl, H.; Newth, D.; Obersteiner, M.; Cai, Y.; Baynes, T.; West, J.; Havlik, P. Assessing global resource use and greenhouse emissions to 2050, with ambitious resource efficiency and climate mitigation policies. Clean. Prod. 2017, 144, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarek, A.M.; Dunston, S.; Enahoro, D.; Charles, J.; Godfray, H.; Herrero, M.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Rich, M.K.; Scarborough, P.; Springmann, M.; et al. Income, consumer preferences, and the future of livestock-derived food demand. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 70, 102343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximillian, J.; Brusseau, M.L.; Glenn, E.P.; Matthias, A.D. Pollution and environmental perturbations in the global system. In Environmental and Pollution Science, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 457–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, C.; Rollins, R.L.; Taladay, K.; Kantar, M.B.; Chock, M.; Shimada, M.; Franklin, E.C. Bitcoin emissions alone could push global warming above 2 °C. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 931–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Paris Agreement; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; 27p, Available online: https://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/convention/application/pdf/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Chen, L.; Msigwa, G.; Yang, M.; Osman, I.A.; Fawzy, S.; Rooney, W.D.; Yap, P.S. Strategies to achieve a carbon neutral society: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 2277–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.M.; Chen, K.; Kang, J.N.; Chen, W.; Wang, X.Y.; Zhang, X. Policy and Management of Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality: A Literature Review. Engineering 2022, 14, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, I.M.T.; Ho, Y.C.; Baloo, L.; Lam, M.K.; Sujarwo, W. A comprehensive review on the advances of bioproducts from biomass towards meeting net zero carbon emissions (NZCE). Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 366, 128167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union. Clean Planet for all A European Strategic Long-Term Vision for a Prosperous, Modern, Competitive and Climate Neutral Economy. COM/2018/773. 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0773 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Climate Action Tracker. CAT Net Zero Target Evaluation. 2023. Available online: https://climateactiontracker.org/global/cat-net-zero-target-evaluations/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Allen, M.; Frame, D.; Huntingford, C.; Huntingford, C.; Jones, C.D.; Lowe, J.A.; Meinshausen, M.; Meinshausen, N. Warming caused by cumulative carbon emissions towards the trillionth tonne. Nature 2009, 458, 1163–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, T.; Smith, S.M.; Black, R.; Cullen, K.; Fay, B.; Lang, J.; Mahmood, S. Assessing the rapidly-emerging landscape of net zero targets. Clim. Policy 2021, 22, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. In Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K., Meyer, L.A., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; 151p, Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/05/SYR_AR5_FINAL_full_wcover.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Levin, K.; Rich, D.; Ross, K.; Fransen, T.; Elliott, C. Designing and Communicating Net-Zero Targets; Working Paper: Washington DC, USA, 2020; 30p, Available online: https://www.wri.org/research/designing-and-communicating-net-zero-targets (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Lēnerts, A.; Popluga, D.; Naglis-Liepa, K.; Rivža, P. Fertilizer use efficiency impact on GHG emissions in the Latvian crop sector. Agron. Res. 2016, 14, 123–133. Available online: https://agronomy.emu.ee/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Vol14-_nr1_Lenerts.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Naglis-Liepa, K.; Popluga, D.; Rivža, P. Typology of Latvian Agricultural Farms in the Context of Mitigation of Agricultural GHG Emissions. In Proceedings of the 15th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Geoconference SGEM 2015 “Ecology, Economics, Education and Legislation”, Albena, Bulgaria, 18–24 June 2015; Volume II, pp. 513–520. [Google Scholar]

- Popluga, D.; Naglis-Liepa, K.; Lenerts, A.; Rivza, P. Marginal abatement cost curve for assessing mitigation potential of Latvian agricultural greenhouse gas emissions: Case study of crop sector. In Proceedings of the 17th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference SGEM 2017, Albena, Bulgaria, 29 June–5 July 2017; Volume 17, pp. 511–518. [Google Scholar]

- Kreišmane Dz Aplociņa, E.; Naglis-Liepa, K.; Bērziņa, L.; Frolova, O.; Lēnerts, A. Diet optimization for dairy cows to reduce ammonia emissions. Res. Rural Dev. 2021, 36, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popluga, D. Pārskats par Projektu “Latvijas Lauksaimniecības Siltumnīcefekta Gāzu Emisiju Robežsamazinājuma Izmaksu Līkņu (MACC) Sasaiste ar Oglekļa Piesaisti un tā Uzkrāšanu Aramzemēs, Ilggadīgajos Zālājos un Mitrājos”. 2018. Available online: https://www.lbtu.lv/sites/default/files/files/projects/P%C4%93t%C4%ABjuma%20p%C4%81rskats_S330_Atskaite%202018.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025). (In Latvian).

- Naglis-Liepa, K. Pārskats Par Projektu “Latvijas Lauksaimniecības Siltumnīcefekta Gāzu un Amonjaka Emisijas, kā arī CO2 Piesaistes (Aramzemēs un Zālājos) Robežsamazinājuma Izmaksu Līkņu (MACC) Pielāgošana Izmantošanai Lauksaimniecības, Vides un Klimata Politikas Veidošanā”. 2021. Available online: https://www.lbtu.lv/sites/default/files/files/projects/20-00-SOINV05-000013_LLU_K_Naglis-Liepa_0.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025). (In Latvian).

- Kesicki, F.; Strachan, N. Marginal abatement cost (MAC) curves: Confronting theory and practice. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 1195–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockel, L.; Sutter, P.; Jonsson, M. Using Marginal Abatement Cost Curves to Realize the Economic Appraisal of Climate Smart Agriculture Policy Options. The EX Ante Carbon-Balance Tool. 2012. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/33830c17-609f-4f0f-a034-b471818ecb59/content (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Meier, A.K. Supply Curves of Conserved Energy, Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, University of California. Available online: https://escholarship.org/content/qt20b1j10d/qt20b1j10d_noSplash_d9c1759a15cb0579ffb9871dacdad972.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Blumstein, C.; Stoft, S.E. Technical efficiency, production functions and conservation supply curves. Energy Policy 1995, 23, 765–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Difiglio, C.; Duleep, K.G.; Greene, D.L. Cost Effectiveness of Future Fuel Economy Improvements. Energy J. 1990, 11, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, A.; Atkinson, C.; Koomey, J.; Meier, A.; Mowris, R.J.; Price, L. Conserved energy supply curves for U.S. Build. Contemp. Econ. Policy 1993, 11, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentz, O.; Haasis, H.-D.; Jattke, A.; Ruβ, P.; Wietschel, M.; Amann, M. Influence of energy-supply structure on emission-reduction costs. Energy 1994, 19, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Least-cost greenhouse planning supply curves for global warming abatement. Energy Policy 1991, 19, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, E.; Wilson, D.; Johansson, T.B. Getting started: No-regrets strategies for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Energy Policy 1991, 19, 526–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitnicki, S.; Budzinski, K.; Juda, J.; Michna, J.; Szpilewicz, A. Opportunities for carbon emissions control in Poland. Energy Policy 1991, 19, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesicki, F.; Ekins, P. Marginal abatement cost curves: A call for caution. Clim. Policy 2012, 12, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blok, K.; Worrell, E.; Cuelenaere, R.; Turkenburg, W. The cost effectiveness of CO2 emission reduction achieved by energy conservation. Energy Policy 1993, 21, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haoqi, Q.; Libo, W.; Weiqi, T. “Lock-in” effect of emission standard and its impact on the choice of market based instruments. Energy Econ. 2017, 63, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Y.; Lee, M.; Seeley, K. Does Technological Innovation Really Reduce Marginal Abatement Costs? Some Theory, Algebraic Evidence, and Policy Implications. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2007, 40, 507–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, P.B.; White, L.J. Innovation in pollution control. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1986, 13, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, D.; Macleod, M.; Wall, E.; Eory, V.; Mcvittie, A.; Barnes, A.; Rees, B.; Pajot, G.; Matthews, R.; Smith, P.; et al. Marginal abatement cost curves for UK agriculture, forestry, land-use and land-use change sector out to 2022. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2009, 6, 242002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, D.; MacLeod, M.; Wall, E.; Eory, V.; McVittie, A.; Barnes, A.; Rees, R.M.; Topp, C.F.E.; Pajot, G.; Matthews, R.; et al. Developing carbon budgets for UK agriculture, land-use, land-use change and forestry out to 2022. Clim. Change 2010, 105, 529–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, D.; Shalloo, L.; Crosson, P.; Donnellan, T.; Farrelly, N.; Finnan, J.; Hanrahan, K.; Lalor, S.; Lanigan, G.; Thorne, F.; et al. An evaluation of the effect of greenhouse gas accounting methods on a marginal abatement cost curve for Irish agricultural greenhouse gas emissions. Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 39, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellerin, S.; Bamière, L.; Angers, D.; Béline, F.; Benoit, M.; Butault, J.-P.; Chenu, C.; Colnenne-David, C.; De Cara, S.; Delame, N.; et al. Identifying cost-competitive greenhouse gas mitigation potential of French agriculture. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 77, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikkatai, S. Emission reductions policy mix: Industrial sector greenhouse gas emission reductions. In Climate Change and Global Sustainability; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Koslowski, F.; Nayak, D.R.; Smith, P.; Saetnan, E.; Ju, X.; Guo, L.; Han, G.; de Perthuis, C.; Lin, E.; et al. Greenhouse gas mitigation in Chinese agriculture: Distinguishing technical and economic potentials. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 26, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGetrick, J.A.; Bubela, T.; Hik, D.S. Automated content analysis as a tool for research and practice: A case illustration from the Prairie Creek and Nico environmental assessments in the Northwest Territories, Canada. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2016, 35, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eory, V.; Pellerin, S.; Carmona Garcia, G.; Lehtonen, H.; Licite, I.; Mattila, H.; Lund-Sørensen, T.; Muldowney, J.; Popluga, D.; Strandmark, L.; et al. Marginal abatement cost curves for agricultural climate policy: State-of-the art, lessons learnt and future potential. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cara, S.; Jayet, P.-A. Marginal abatement costs of greenhouse gas emissions from European agriculture, cost effectiveness, and the EU non-ETS burden sharing agreement. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1680–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cara, S.; Houzé, M.; Jayet, P.-A. Methane and Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Agriculture in the EU: A Spatial Assessment of Sources and Abatement Costs. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2005, 32, 551–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hediger, W. Modeling GHG emissions and carbon sequestration in Swiss agriculture: An integrated economic approach. Int. Congr. Ser. 2006, 1293, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, A.; Hertel, T.; Lee, H.-L.; Rose, S.; Sohngen, B. The opportunity cost of land use and the global potential for greenhouse gas mitigation in agriculture and forestry. Resour. Energy Econ. 2009, 31, 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Dominguez, I.; Britz, W.; Holm-Müller, K. Trading schemes for greenhouse gas emissions from European agriculture: A comparative analysis based on different implementation options. Rev. D’études Agric. Environ. 2009, 90, 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, U.A.; McCarl, B.A.; Schmid, E. Agricultural sector analysis on greenhouse gas mitigation in US agriculture and forestry. Agric. Syst. 2007, 94, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, R.H.; DeAngelo, B.J.; Rose, S.; Li, C.; Salas, W.; DelGrosso, S.J. Mitigation potential and costs for global agricultural greenhouse gas emissions. Agric. Econ. 2008, 38, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höglund-Isaksson, L.; Winiwarter, W.; Purohit, P.; Rafaj, P.; Schöpp, W.; Klimont, Z. EU low carbon roadmap 2050: Potentials and costs for mitigation of non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions. Energy Strategy Rev. 2012, 1, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekins, P.; Kesicki, F.; Smith, A.Z.P. Marginal Abatement Cost Curves: A Call for Caution. 2011. [A Report from the UCL Energy Institute to, and Commissioned by, Greenpeace UK]. Available online: https://www.homepages.ucl.ac.uk/~ucft347/MACCCritGPUKFin.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Levihn, F.; Nuur, C.; Laestadius, S. Marginal abatement cost curves and abatement strategies: Taking option interdependency and investments unrelated to climate change into account. Energy 2014, 76, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponz-Tienda, J.L.; Prada-Hernández, A.V.; Salcedo-Bernal, A.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D. Marginal Abatement Cost Curves (MACC): Unsolved Issues, Anomalies, and Alternative Proposals. In Carbon Footprint and the Industrial Life Cycle; Fernández, R.Á., Zubelzu, S., Martínez, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. The ranking of negative-cost emissions reduction measures. Energy Policy 2012, 48, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D.J. The failure of marginal abatement cost curves in optimising a transition to a low carbon energy supply. Energy Policy 2014, 73, 820–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latvia. 2024 Biennial Transparency Report (BTR). BTR1. Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents/645013 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Moran, D.; Macleod, M.; Wall, E.; Eory, V.; McVittie, A.; Barnes, A.; Rees, R.; Topp, C.F.E.; Moxey, A. Marginal Abatement Cost Curves for UK Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Emissions. J. Agric. Econ. 2011, 62, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A.; Iglesias, A.; McVittie, J.; Álvaro-Fuentes, J.; Ingram, J.; Mills, J.P.; Lesschen, P.J.; Kuikman, J. Management of agricultural soils for greenhouse gas mitigation: Learning from a case study in NE Spain. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 170, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamière, L.; Bellassen, V.; Angers, D.; Cardinael, R.; Ceschia, R.; Chenu, C.; Constantin, J.; Delame, N.; Diallo, A.; Graux, A.-I.; et al. A marginal abatement cost curve for climate change mitigation by additional carbon storage in French agricultural land. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 383, 135423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Hailu, A.; Yang, Y. Agricultural chemical oxygen demand mitigation under various policies in China: A scenario analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 250, 119513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macleod, M.; Moran, D. Integrating livestock health measures into marginal abatement cost curves. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2017, 36, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valujeva, K.; Freed, E.K.; Nipers, A.; Jauhiainen, J.; Schulte, R.P.O. Pathways for governance opportunities: Social network analysis to create targeted and effective policies for agricultural and environmental development. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teagasc. Explainer: What Is and Why Is a New MACC Needed? Teagasc: Carlow, Ireland, 2023; Available online: https://teagasc.ie/news--events/daily/explainer-what-is-and-why-is-a-new-macc-needed/#:~:text=The%20third%20iteration%20of%20the,the%20most%20cost%20effective%20measures.%E2%80%9D (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Latvia Air pollution Action Plan 2020–2030. Regulation of Minister Cabinet of Republic of Latvia. Nr.197. Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/314078-par-gaisa-piesarnojuma-samazinasanas-ricibas-planu-2020-2030-gadam (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Hannus, V.; Venus, T.J.; Sauer, J. Acceptance of sustainability standards by farmers—Empirical evidence from Germany. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 267, 110617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julian Ramirez-Villegas, J.; Challinor, A. Assessing relevant climate data for agricultural applications. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2012, 161, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture of Republic of Latvia. Various Agricultural Data Will Be Linked into a Single System—Entrepreneurs Will Not Have to Enter It Repeatedly. Available online: https://www.zm.gov.lv/lv/jaunums/dazadi-lauksaimniecibas-dati-bus-saistiti-vienota-sistema-uznemejiem-tie-nebus-jaievada-atkartoti (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Lefèvre, J. Integrated assessment models and input–output analysis: Bridging fields for advancing sustainability scenarios research. Econ. Syst. Res. 2023, 36, 675–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |