Automated μFTIR Imaging Demonstrates Variability in Microplastic Ingestion by Aquatic Insects in a Remote Taiwanese Mountain Stream

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andrady, A.L. Microplastics in the marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 1596–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillig, M.C.; Lehmann, A. Microplastic in terrestrial ecosystems. Science 2020, 368, 1430–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.P. Microplastics in freshwater systems: A review on occurrence, environmental effects, and methods for microplastics detection. Water Res. 2018, 137, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winiarska, E.; Jutel, M.; Zemelka-Wiacek, M. The potential impact of nano-and microplastics on human health: Understanding human health risks. Environ. Res. 2024, 251, 118535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Xu, B.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Huang, S.; Jiang, Z.; Gong, X.; Yang, H. From plankton to fish: The multifaceted threat of microplastics in freshwater environments. Aquat. Toxicol. 2025, 279, 107242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wang, H.; Liang, D.; Li, Y.; Shen, Z. How the Yangtze River transports microplastic to the east China sea. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 136112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegfried, M.; Koelmans, A.A.; Besseling, E.; Kroeze, C. Export of microplastics from land to sea. A modelling approach. Water Res. 2017, 127, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, M.; Pant, G.; Pant, K.; Aloo, B.N.; Kumar, G.; Singh, H.B.; Tripathi, V. Microplastic Pollution in Terrestrial Ecosystems and Its Interaction with Other Soil Pollutants: A Potential Threat to Soil Ecosystem Sustainability. Resources 2023, 12, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.H.; Liang, Y.; Kim, M.; Byun, J.; Choi, H. Microplastics with adsorbed contaminants: Mechanisms and treatment. Environ. Chall. 2021, 3, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanale, C.; Massarelli, C.; Savino, I.; Locaputo, V.; Uricchio, V.F. A detailed review study on potential effects of microplastics and additives of concern on human health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Huang, Q.-S.; Sun, J.; Wang, J.-Y.; Wu, S.-L.; Ni, B.-J. Polyvinyl chloride microplastics affect methane production from the anaerobic digestion of waste activated sludge through leaching toxic bisphenol-A. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 2509–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, E.M.; Shimeta, J.; Nugegoda, D.; Morrison, P.D.; Clarke, B.O. Assimilation of polybrominated diphenyl ethers from microplastics by the marine amphipod, Allorchestes compressa. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 8127–8134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochman, C.M.; Lewison, R.L.; Eriksen, M.; Allen, H.; Cook, A.-M.; Teh, S.J. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in fish tissue may be an indicator of plastic contamination in marine habitats. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 476, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granby, K.; Rainieri, S.; Rasmussen, R.R.; Kotterman, M.J.; Sloth, J.J.; Cederberg, T.L.; Barranco, A.; Marques, A.; Larsen, B.K. The influence of microplastics and halogenated contaminants in feed on toxicokinetics and gene expression in European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Environ. Res. 2018, 164, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Lu, H.; Yao, T.; Xue, Y.; Yin, C.; Tang, M. Spatial characteristics of microplastics in the high-altitude area on the Tibetan Plateau. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 417, 126034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, Y.; Govindasamy, H.; Kaur, G.; Ajith, N.; Ramasamy, K.; RS, R.; Ramachandran, P. Microplastic pollution in high-altitude Nainital lake, Uttarakhand, India. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 346, 123598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, M.; Mützel, S.; Primpke, S.; Tekman, M.B.; Trachsel, J.; Gerdts, G. White and wonderful? Microplastics prevail in snow from the Alps to the Arctic. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusher, A.L.; Tirelli, V.; O’Connor, I.; Officer, R. Microplastics in Arctic polar waters: The first reported values of particles in surface and sub-surface samples. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hee, Y.Y.; Hanif, N.M.; Weston, K.; Latif, M.T.; Suratman, S.; Rusli, M.U.; Mayes, A.G. Atmospheric microplastic transport and deposition to urban and pristine tropical locations in Southeast Asia. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 166153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Allen, D.; Phoenix, V.R.; Le Roux, G.; Durántez Jiménez, P.; Simonneau, A.; Binet, S.; Galop, D. Atmospheric transport and deposition of microplastics in a remote mountain catchment. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, E. Synthetic organohalides in the sea. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. B. Biol. Sci. 1975, 189, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, P.; Grimalt, J.O. On the global distribution of persistent organic pollutants. Chimia 2003, 57, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadzi, G.Y.; Essumang, D.K.; Adjei, J.K. Distribution and risk assessment of heavy metals in surface water from pristine environments and major mining areas in Ghana. J. Health Pollut. 2015, 5, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, J.; Wauchope, R.; Klein, A.; Dorn, E.; Zeeh, B.; Yeh, S.; Akerblom, M.; Racke, K.; Rubin, B. Significance of the long range transport of pesticides in the atmosphere. Pure Appl. Chem. 1999, 71, 1359–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhao, J.; Liu, R.; Xing, B. Interaction of microplastics with antibiotics in aquatic environment: Distribution, adsorption, and toxicity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 15579–15595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.-K.; Leung, K.S.-Y. The crucial role of heavy metals on the interaction of engineered nanoparticles with polystyrene microplastics. Water Res. 2021, 201, 117317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löder, M.G.; Gerdts, G. Methodology used for the detection and identification of microplastics—A critical appraisal. In Marine Anthropogenic Litter; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 201–227. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.K.; Hong, S.H.; Eo, S.; Shim, W.J. A comparison of spectroscopic analysis methods for microplastics: Manual, semi-automated, and automated Fourier transform infrared and Raman techniques. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 173, 113101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leusch, F.D.; Lu, H.-C.; Perera, K.; Neale, P.A.; Ziajahromi, S. Analysis of the literature shows a remarkably consistent relationship between size and abundance of microplastics across different environmental matrices. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 319, 120984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Primpke, S.; Lorenz, C.; Rascher-Friesenhausen, R.; Gerdts, G. An automated approach for microplastics analysis using focal plane array (FPA) FTIR microscopy and image analysis. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 1499–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.L.; Ulke, J.; Font, A.; Chan, K.L.A.; Kelly, F.J. Atmospheric microplastic deposition in an urban environment and an evaluation of transport. Environ. Int. 2020, 136, 105411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerasingam, S.; Ranjani, M.; Venkatachalapathy, R.; Bagaev, A.; Mukhanov, V.; Litvinyuk, D.; Mugilarasan, M.; Gurumoorthi, K.; Guganathan, L.; Aboobacker, V. Contributions of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy in microplastic pollution research: A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 51, 2681–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E.N.; Treado, P.J.; Reeder, R.C.; Story, G.M.; Dowrey, A.E.; Marcott, C.; Levin, I.W. Fourier transform spectroscopic imaging using an infrared focal-plane array detector. Anal. Chem. 1995, 67, 3377–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathore, C.; Saha, M.; Gupta, P.; Kumar, M.; Naik, A.; de Boer, J. Standardization of micro-FTIR methods and applicability for the detection and identification of microplastics in environmental matrices. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 888, 164157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, T.; Cabigliera, S.B.; Martellini, T.; Laurati, M.; Chelazzi, D.; Galassi, D.M.P.; Cincinelli, A. Ingestion of microplastics and textile cellulose particles by some meiofaunal taxa of an urban stream. Chemosphere 2023, 310, 136830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.-G.; Mintenig, S.M.; Redondo-Hasselerharm, P.E.; Neijenhuis, P.H.; Yu, K.-F.; Wang, Y.-H.; Koelmans, A.A. Automated μFTIR imaging demonstrates taxon-specific and selective uptake of microplastic by freshwater invertebrates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 9916–9925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S. Ephemeroptera of Taiwan (Excluding Baetidae); National Chung Hsing University: Taichung, Taiwan, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kawai, T.; Tanida, K. Aquatic Insects of Japan: Manual with Keys and Illustrations; Tokai University Press: Yoyogi, Tokyo, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Merritt, R.W.; Cummins, K.W.; Berg, M.B. (Eds.) An Introduction to the Aquatic Insects of North America, 5th ed.; Kendall Hunt Publishing Company: Dubuque, IA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Benke, A.C.; Huryn, A.D.; Smock, L.A.; Wallace, J.B. Length-mass relationships for freshwater macroinvertebrates in North America with particular reference to the southeastern United States. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 1999, 18, 308–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-T.; Chiu, M.-C.; Kuo, M.-H. Effects of anthropogenic activities on microplastics in deposit-feeders (Diptera: Chironomidae) in an urban river of Taiwan. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-T.; Chiu, M.-C.; Kuo, M.-H. Seasonality can override the effects of anthropogenic activities on microplastic presence in invertebrate deposit feeders in an urban river system. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 443, 130272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, M.; Van Cauwenberghe, L.; Vandegehuchte, M.B.; Janssen, C.R. New techniques for the detection of microplastics in sediments and field collected organisms. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 70, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Wei, C.-H.; Hsu, W.-T.; Proborini, W.D.; Hsiao, T.-C.; Liu, Z.-S.; Chou, H.-C.; Soo, J.-C.; Dong, G.-C.; Chen, J.-K. Impact of seasonal changes and environmental conditions on suspended and inhalable microplastics in urban air. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 362, 124994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecozzi, M.; Pietroletti, M.; Monakhova, Y.B. FTIR spectroscopy supported by statistical techniques for the structural characterization of plastic debris in the marine environment: Application to monitoring studies. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 106, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M. A novel method for preparing microplastic fibers. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Posit Team. Posit Software, 2023, RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2023.

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Song, J.; Nunes, L.M.; Zhao, H.; Wang, P.; Liang, Z.; Arp, H.P.H.; Li, G.; Xing, B. Global microplastic fiber pollution from domestic laundry. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 477, 135290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, S.; Okoffo, E.D.; O’Brien, J.W.; Ribeiro, F.; Wang, X.; Wright, S.L.; Samanipour, S.; Rauert, C.; Toapanta, T.Y.A.; Albarracin, R. Airborne emissions of microplastic fibres from domestic laundry dryers. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 747, 141175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plastics Europe. Plastics—The Fast Facts 2024. 2024. Available online: https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-fast-facts-2024/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Emblem, A. Plastics properties for packaging materials. In Packaging Technology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 287–309. [Google Scholar]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Wang, W.-X. Accumulation kinetics and gut microenvironment responses to environmentally relevant doses of micro/nanoplastics by zooplankton Daphnia magna. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 5611–5620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welden, N.A.; Cowie, P.R. Environment and gut morphology influence microplastic retention in langoustine, Nephrops norvegicus. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 214, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez Troncoso, M.R.; Gutierrez Rial, D.; Villar Comesaña, I.; Ehlers, S.M.; Soto González, B.; Mato de la Iglesia, S.; Garrido González, J. Microplastics in water, sediments and macroinvertebrates in a small river of NW Spain. Limnetica 2024, 43, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossa-Yepes, M.; Ríos-Pulgarín, M.I.; Villabona-González, S.L.; Zapata-Vahos, I.C.; Martínez, F.A.; Barletta, M. Microplastics and other anthropogenic particles contamination and their potential trophic transfer in a tropical Andean reservoir, Colombia. Hydrobiologia 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiemstra, A.-F.; van der Velden, I.; Ciliberti, P.; D’Alba, L.; Gravendeel, B.; Schilthuizen, M. Half a century of caddisfly casings (Trichoptera) with microplastic from natural history collections. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 974, 178947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, H.A.; Dalu, T.; Wasserman, R.J. Sinks and sources: Assessing microplastic abundance in river sediment and deposit feeders in an Austral temperate urban river system. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 950–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, A.; Godbold, J.A.; Lewis, C.N.; Savage, G.; Solan, M.; Galloway, T.S. Microplastic burden in marine benthic invertebrates depends on species traits and feeding ecology within biogeographical provinces. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardlaw, C.M.; Corcoran, P.L.; Neff, B.D. Factors influencing the variation of microplastic uptake in demersal fishes from the upper Thames River Ontario. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 313, 120095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, A.K.; Midway, S.R. Relationship of microplastics to body size for two estuarine fishes. Microplastics 2022, 1, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.L.; Thompson, R.C.; Galloway, T.S. The physical impacts of microplastics on marine organisms: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 178, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akindele, E.O.; Ehlers, S.M.; Koop, J.H. Freshwater insects of different feeding guilds ingest microplastics in two Gulf of Guinea tributaries in Nigeria. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 33373–33379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoli, M.; Pastorino, P.; Lesa, D.; Renzi, M.; Anselmi, S.; Prearo, M.; Pizzul, E. Microplastics accumulation in functional feeding guilds and functional habit groups of freshwater macrobenthic invertebrates: Novel insights in a riverine ecosystem. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 804, 150207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Lu, H.; Tian, P.; Xue, Y.; Lu, J.; Tang, M.; Feng, W. Analysis of microplastics in a remote region of the Tibetan Plateau: Implications for natural environmental response to human activities. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 140087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

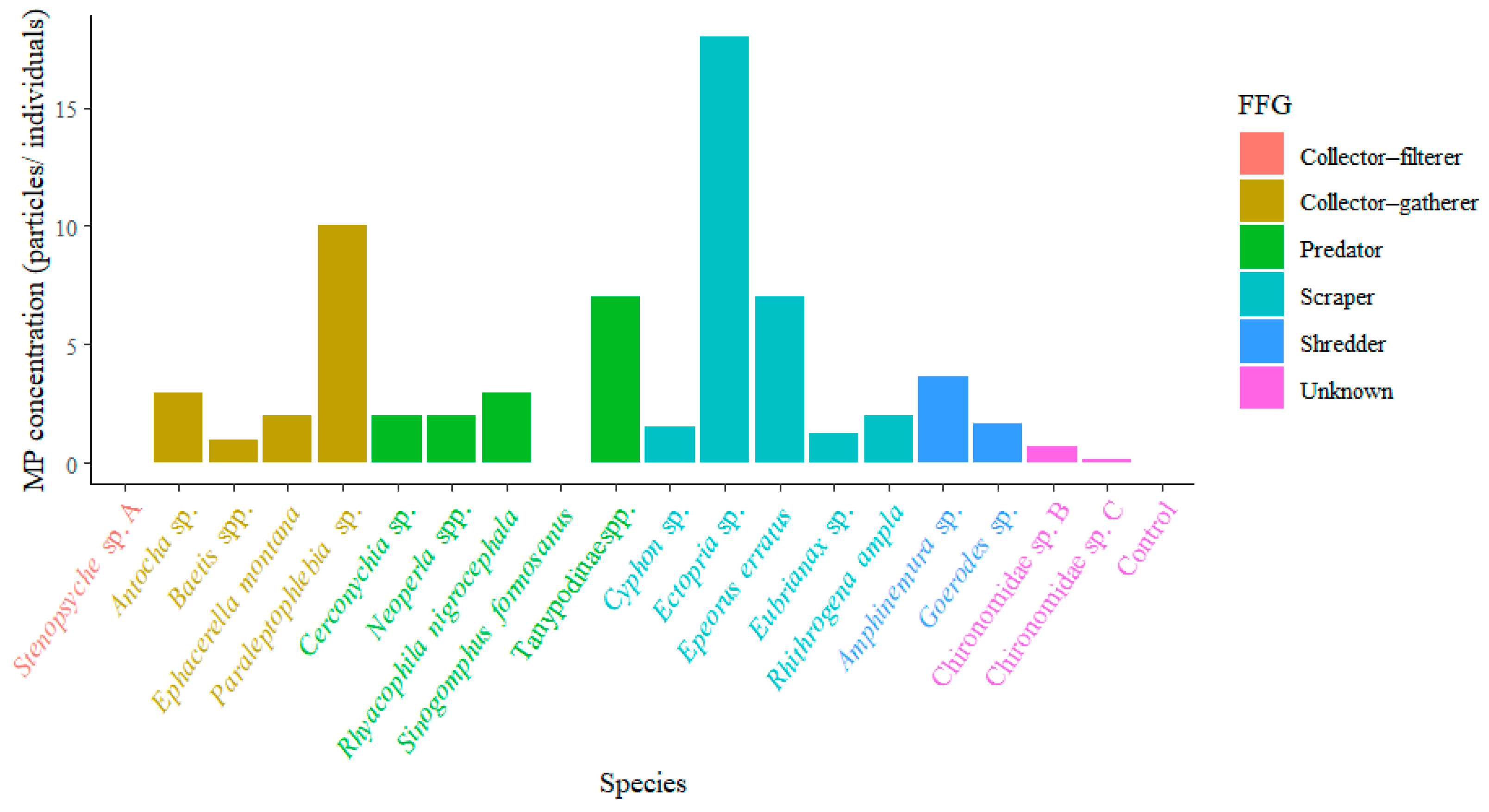

| Taxon | FFG | Total Dry Weight (mg) | Number of Insects | Number of MP Particles | MP Chemical Composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paraleptophlebia sp. | Collector–gatherer | 0.03 | 2 | 20 | PE, PP |

| Rhithrogena ampla | Scraper | 0.15 | 1 | 2 | PE, Rayon |

| Epeorus erratus | Scraper | 0.05 | 1 | 7 | PE, PP |

| Baetis spp. | Collector–gatherer | 2.11 | 7 | 7 | PE |

| Ephacerella montana | Collector–gatherer | 0.01 | 1 | 2 | PE, PP |

| Goerodes sp. | Shredder | 4.06 | 6 | 10 | PE, PP |

| Stenopsyche sp. A | Collector–filterer | 249.38 | 1 | 0 | - |

| Rhyacophila nigrocephala | Predator | 0.30 | 1 | 3 | PE, PET |

| Cerconychia sp. | Predator | 8.37 | 5 | 10 | PE, PP, Rayon |

| Amphinemura sp. | Shredder | 0.12 | 3 | 11 | PE, PET, PP |

| Neoperla sp. | Predator | 15.77 | 3 | 6 | PP |

| Cyphon sp. | Scraper | 3.12 | 6 | 9 | PE |

| Eubrianax sp. | Scraper | 15.67 | 4 | 5 | PE |

| Ectopria sp. | Scraper | 0.20 | 1 | 18 | PE, PET, PP |

| Antocha sp. | Collector–gatherer | 0.10 | 2 | 6 | PA, PE, PP |

| Tanypodinae spp. | Predator | 0.02 | 1 | 7 | PE, PP |

| Chironomidae sp. B | Unknown | 0.16 | 7 | 5 | PP, Rayon |

| Chironomidae sp. C | Unknown | 0.50 | 11 | 2 | PE |

| Sinogomphus formosanus | Predator | 2.21 | 1 | 0 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.-C.; Wei, C.-H.; Chiu, M.-C.; Chen, Y.-C.; Kuo, M.-H.; Resh, V.H. Automated μFTIR Imaging Demonstrates Variability in Microplastic Ingestion by Aquatic Insects in a Remote Taiwanese Mountain Stream. Environments 2026, 13, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010003

Wu Y-C, Wei C-H, Chiu M-C, Chen Y-C, Kuo M-H, Resh VH. Automated μFTIR Imaging Demonstrates Variability in Microplastic Ingestion by Aquatic Insects in a Remote Taiwanese Mountain Stream. Environments. 2026; 13(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Yu-Cheng, Chun-Hsuan Wei, Ming-Chih Chiu, Yu-Cheng Chen, Mei-Hwa Kuo, and Vincent H. Resh. 2026. "Automated μFTIR Imaging Demonstrates Variability in Microplastic Ingestion by Aquatic Insects in a Remote Taiwanese Mountain Stream" Environments 13, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010003

APA StyleWu, Y.-C., Wei, C.-H., Chiu, M.-C., Chen, Y.-C., Kuo, M.-H., & Resh, V. H. (2026). Automated μFTIR Imaging Demonstrates Variability in Microplastic Ingestion by Aquatic Insects in a Remote Taiwanese Mountain Stream. Environments, 13(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010003