Abstract

Given the climate variability of semi-arid regions, this study analysed rainfall regimes and their influence on consecutive dry days (CDDs) and cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) productivity in Ceará, Brazil. Rainfall data from 184 municipalities (1990–2019) and productivity records were used across eight homogeneous rainfall regions. Water scenarios (very dry, dry, normal, rainy, and very rainy) were defined using quantiles, and three CDD classes were considered: CDD1 (5–10 days), CDD2 (11–15 days), and CDD3 (>15 days). Statistical analyses were performed with the Kruskal–Wallis test and Spearman’s correlation, and spatial patterns were mapped with ordinary kriging. Ceará’s climate normal was 837 mm, with the Central Sertão and Inhamuns and Jaguaribana showing the lowest rainfall. A total of 39,382 CDD events were identified, with 67% as CDD1, 16% as CDD2, and 17% as CDD3. Cariri had the highest CDD1 occurrences, while Central Sertão and Inhamuns recorded the highest CDD3. Cowpea yield averaged 286 ± 85 kg ha−1, with the lowest productivity in Central Sertão and Inhamuns due to reduced rainfall and frequent CDD3. Productivity correlated positively with CDD1 in one very dry scenario and negatively with CDD3 in very dry, dry, and normal conditions. The findings highlight regional vulnerabilities and the strong link between CDD and crop yield.

1. Introduction

Rainfed agriculture plays a crucial role in food production [1], corresponding to 60% of all cultivated areas and accounting for 80% of the food produced [2]. This type of agriculture is closely linked to climate conditions and faces significant challenges due to the variability and unpredictability of rainfall events [3,4,5].

This uncertainty is more obvious in arid and semi-arid regions and is related not only to the total rainfall but also to its spatial and temporal distribution [6,7,8,9]. In these regions, very dry and very rainy years often alternate with normal years [10,11,12,13,14].

Among the dry regions of the world, the semi-arid region of Brazil (SAB), which covers an area of 1,335,298 km2, is the most populated in the world, with 28 million inhabitants [15,16]. Despite the uncertainties of the rainfall regime, rainfed agriculture in the SAB is found in 89% of all rural establishments, where the main crop is the cowpea (Vigna unguiculata), with a production area of 743,443 hectares [17,18]. The cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) is adapted to various types of soil and has a short cycle, together with a water requirement of between 300 and 450 mm cycle−1 [19,20]. Although the water demand of this crop is low, it is sensitive to long periods of consecutive dry days (CDDs), so it is essential to understand and monitor the distribution of rainfall events to ensure satisfactory yields [21].

The impact of consecutive dry days depends on such factors as the duration of the phenomenon and the phenological stage of the crop [22,23,24,25], as seen by Cavalcante et al. [26], who observed changes in the rate of photosynthesis and in stomatal functions during CDD. Furthermore, in the current scenario of climate change, the trend is towards changes in rainfall patterns [27,28,29].

Researchers have seen an increase in extreme events, such as droughts and floods, as well as an increase in the number of consecutive dry days [27,28,30,31], which changes depending on the following regional characteristics: location, climate, and season [4,5,32,33,34].

There have been several studies on rainfall regimes and their effect on rainfed agriculture [33,35,36]. Fernandes et al. [22] found a significant reduction in the physiological functioning of the cowpea subjected to 10 consecutive dry days, whereas 2 mm of rainfall had a positive effect on the metabolic activity of the crop. Rocha et al. [24] employed dry, normal, and rainy scenarios to correlate agricultural losses with the number of CDDs. Similarly, Nogueira et al. [8] verified the occurrence of consecutive dry days under dry, normal, and rainy regimes, with a reduction of 69% in agricultural production subjected to CDDs > 15 days.

While earlier research addresses dry, normal, and rainy scenarios and their impact on agriculture, the semi-arid region goes beyond these scenarios, being characterised by its susceptibility to extreme conditions, such as severely dry and excessively rainy years. Furthermore, existing studies do not detail the exact number of CDDs in each water scenario, which is crucial for understanding the pattern of dry periods during the rainy season and their impact on rainfed agriculture. We, therefore, assumed that the amount and duration of consecutive dry days affect cowpea production under different rainfall regimes.

This study aimed to understand climate and production patterns in different water scenarios in a semi-arid region and to correlate the variables to determine the influence of each element. The specific objectives were (i) to evaluate the spatial and temporal distribution of the rainfall, (ii) to quantify and evaluate the spatial distribution of consecutive dry days in different water scenarios, (iii) to quantify and evaluate the spatial distribution of cowpea productivity under different rainfall regimes and (iv) to verify the correlation between the variables that characterise rainfall regimes and cowpea productivity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

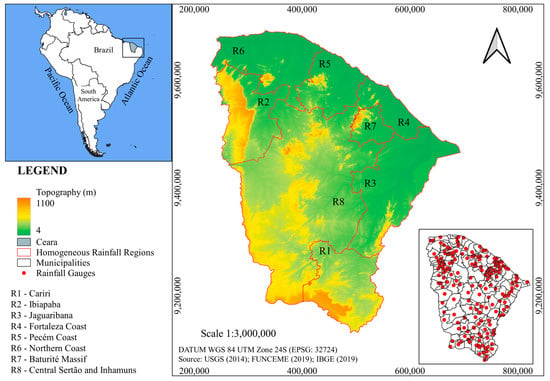

The state of Ceará is located in the northeast of Brazil and covers an area of 148,894 km2 with approximately 8.8 million inhabitants [37]. The region has a unimodal rainfall regime, with 60% of the rainfall concentrated from February to April, a result of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), which is the main meteorological system responsible for precipitation [38]. Potential evapotranspiration ranges from 1243 to 2212 mm yr−1 [39]. The predominant climate in the region is type BSh’, dry semi-arid, characterised by high evaporation, high average temperatures, and low rainfall [40].

The aridity index in 76.16% of the area of Ceará ranges from 0.21 to 0.50, classifying it as semi-arid; the extensive area includes dry sub-humid and humid sub-humid climates [39]. Given the different climate types, Xavier [41] adopted the quantile technique, subdividing Ceará into eight homogeneous rainfall regions (HRRs) with similar rainfall patterns. These zones are the Northern Coastal Region, the Coastal Region of Pecém, the Coastal Region of Fortaleza, Ibiapaba, the Baturité Massif, Jaguaribana, the Central Sertão and Inhamuns, and Cariri (Figure 1), regions monitored by the Ceará Foundation for Meteorology and Water Resources [42].

Figure 1.

Location of the study area.

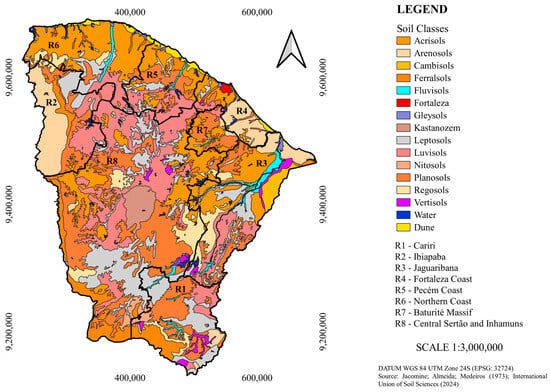

The study area exhibits a wide spatial variability of soil classes (Figure 2) [43], with emphasis on Planosols, Acrisols, Luvisols, and Leptosols, according to the World Reference Base (WRB) classes [44], which cover 22%, 19%, 18%, and 14% of the territorial area, respectively.

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of soil classes in the state of Ceará.

In soil management, rural properties are divided into two categories: those without soil tillage and those with soil tillage. In Ceará, 44% of agricultural properties do not perform soil tillage, while 27% adopt conventional tillage, 26% use minimum tillage, and 3% employ no-tillage systems, Table 1 [17].

Table 1.

Tipos de sistemas de preparo do solo, por região, no Ceará.

2.2. Hydrological Regime

2.2.1. Rainfall

Daily rainfall data (1990–2019) were obtained from the Foundation for Meteorology and Water Resources of Ceará [42] and included 184 rainfall stations (Figure 1), one in each municipality, where the criterion for using the information was the consistency of the data. The process involved analysing the historical series from 1990 to 2019 for each rainfall station. Whenever daily data were missing, the corresponding year was completely excluded.

Of the 184 stations, 88% had 30 years of data; 9% had 25 to 30 years of data; and 3% had 25 to 20 years of data. The data were homogeneous at a level of 95% [8,45].

2.2.2. Consecutive Dry Days (CDDs)

The number of consecutive dry days was calculated using the daily rainfall data, defining the CDD as a period of at least five consecutive dry days with less than 2 mm of rainfall [22], considering that rainfall values above 2 mm positively influence the physiological activities of cowpea cultivation [35]. The consecutive dry days were classified based on duration: CDD1 (5–10 days), CDD2 (11–15 days), and CDD3 (>15 days). The evaluation period lasted from January to May.

January was included in the evaluation, as this is when seed is distributed to farmers by the Rural Assistance and Extension Company of Ceará (EMATERCE), Ceará, Brazil. January in Ceará is characterised by increasing rainfall and consecutive wet days [27], with farmers planting their crops immediately after the first rains, with January to May being the period of rainfed farming in the region [46].

Finally, the CDDs were quantified using a routine written in the Python version 3.11 programming language. The daily rainfall data were then input into the program for the algorithm to count and classify the number of consecutive dry days. The script is shown in Appendix A.

2.2.3. Water Scenarios

The water scenarios were defined using Pinkayan’s Quantile Technique. The method is based on arranging the annual rainfall in ascending order and calculating the quartile position to categorise the years into their respective scenarios [41,47]. Years with the lowest 15% of the total annual rainfall were categorised as ‘very dry’, years with between 15% and 35% were classified as ‘dry’, years with between 35% and 65% were classified as ‘normal’, years with from 65% to 85% were classified as ‘rainy’, and years above 85% were classified as ‘very rainy’ [48].

2.3. Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) Yield

Yield data (kg ha−1) on the cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) between 1990 and 2019 were obtained from the IBGE Automatic Recovery System (SIDRA) [49]. The system provides statistical information on municipal agricultural production in Brazil, including data on annual and perennial crops relating to production, yield, planted area, harvested area, and production value.

Cowpea cultivation in Ceará follows a uniform pattern among farmers, with planting carried out shortly after the first rains of the year [46]. The seeds used belong to the same cultivar, being provided by the government through the Hora de Plantar program and distributed simultaneously throughout the state by the Empresa de Assistência Técnica e Extensão Rural do Ceará [50].

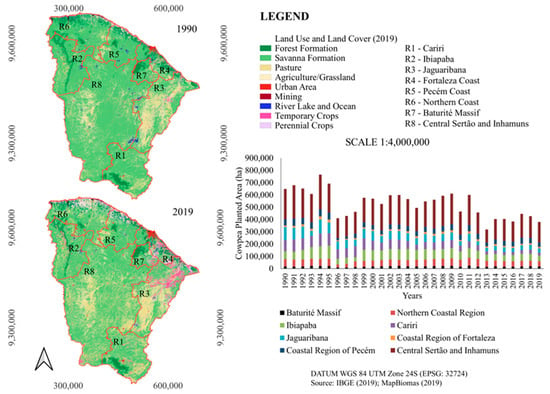

Additionally, to complement this information, the land use and land cover dataset from the MAPBIOMAS project for the years 1990 and 2019 was used, aiming to visualise the spatial arrangement of cultivated areas in the state of Ceará [51].

2.4. Interpolation of the Data

Ordinary kriging was applied to generate the maps of the hydrologic regime and cowpea yield in the Quantum GIS (QGIS) 3.10 software using the Processing R Provider plugin [52]. It should be noted that a semivariogram was calculated for each variable to select the best-fitted model [53], which was chosen based on the spatial dependence of the data [54].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The return period was calculated as the inverse of the probability of occurrence of consecutive dry days (CDDs). The probability was obtained as the ratio between the number of years in which the CDD occurred within its respective duration class and the total years of the studied historical series [55].

The data (rainfall, CDD1, CDD2, CDD3, cowpea yield) were submitted to the Shapiro–Wilk test, which confirmed the lack of normality. Therefore, nonparametric statistical methods were adopted. The Kruskal–Wallis [56] test was used to verify statistical differences between the variables in the homogeneous rainfall regions in each water scenario. After rejecting the null hypothesis, the groups were submitted to Dunn’s post hoc test to identify regions that differed from each other.

Finally, Spearman’s coefficient was used to verify the degree of association between the parameters under study. The test generates values between −1 ≤ R ≤ 1, with the correlation coefficients considered significant when p < 0.01 [57,58]. The statistical tests were conducted using the SPSS Statistics software, version 23.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Hydrological Regime

3.1.1. Rainfall

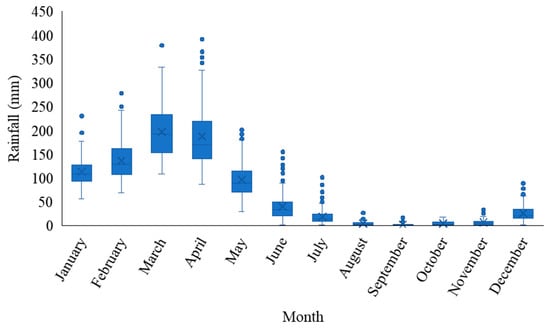

The climate normal for the state of Ceará is 837 mm yr−1, with irregular temporal rainfall distribution and the presence of two distinct periods: the rainy season and the dry season. The rainy season, which begins in January and lasts until May (Figure 3), accounted for 62% of the total rainfall for the state, with 521 mm distributed during February, March, and April (137, 197, and 188 mm, respectively). December with 26.3 mm of rain and January with 113.7 mm represent the pre-rainy season, while June (40.4 mm) and July (19.1 mm) mark the transition between the rainy and the dry seasons.

Figure 3.

Climate normal for the state of Ceará (1990–2019).

February, March, and April correspond to the rainy season in the semi-arid region of Brazil [38,59,60,61,62]. The greater rainfall during these three months is due to the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) being positioned to the south, which favours increased rainfall in the region. However, during May, the ITCZ shifts to the northern hemisphere, resulting in less rainfall [63,64].

In addition to the ITCZ, other atmospheric phenomena contribute to the rainfall in Ceará. From December to January, cold fronts occur due to the meeting of two air masses with different temperatures, while easterly waves occur due to changes in wind circulation, generating intense rainfall from June to August [27,65,66].

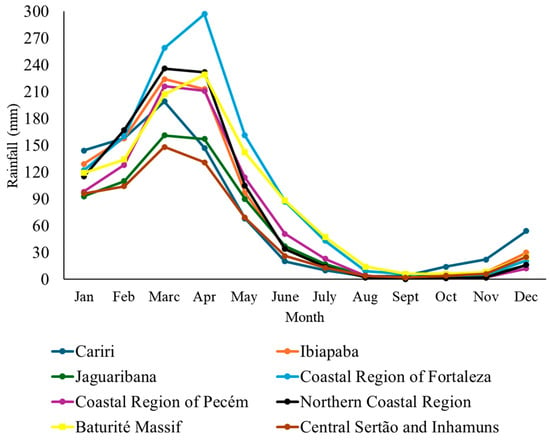

To illustrate the predominant differences in the climate of Ceará, the climate normal was verified for each homogeneous rainfall region (Figure 4). The Central Sertão and Inhamuns and Jaguaribana had rainfall of 628 and 693 mm yr−1, respectively, and were, therefore, the regions with the lowest rainfall indices, remaining below the climate average for the state.

Figure 4.

Climate normal by homogeneous rainfall region in the state of Ceará from 1990 to 2019.

Using the Kruskal–Wallis method, the rainfall showed statistically significant differences between the homogeneous rainfall regions under the very dry [X2(2) = 73.202; p < 0.01], dry [X2(2) = 87.670; p < 0.01], normal [X2(2) = 93.229; p < 0.01], rainy [X2(2) = 103.092; p < 0.01], and very rainy [X2(2) = 96.025; p < 0.01] regimes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Analysis of the rainfall by homogeneous rainfall region in the state of Ceará for different water scenarios.

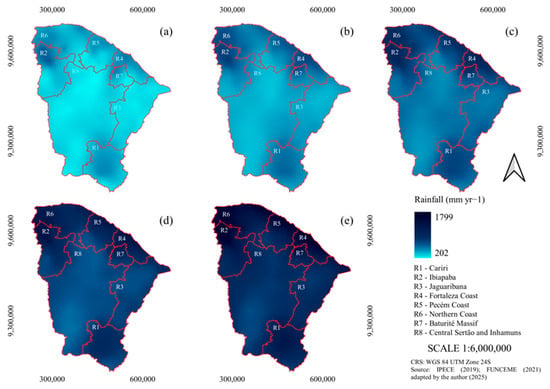

The results of the Kruskal–Wallis analysis (Table 2) are corroborated by the spatial distribution of the rainfall (Figure 5), where, in the very dry (Figure 5a) and dry (Figure 5b) scenarios, the lowest rainfall indices were seen in municipalities located in the regions of Jaguaribana and Central Sertão and Inhamuns. These locations are noteworthy due to the reduction in rainfall.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of the rainfall in Ceará by scenario: (a) very dry; (b) dry; (c) normal; (d) rainy; (e) very rainy.

Under the very dry regime, the regions of Jaguaribana and Central Sertão and Inhamuns recorded 246 and 263 mm, respectively, while under the dry regime, the values were 387 and 377 mm, respectively, differing from the other regions. As a result, the inhabitants of these areas are susceptible to problems caused by water scarcity, compromising agricultural production and the recharge of bodies of water [21,67]. Emergency measures should be adopted by the government to reduce the effects of drought and ensure the survival of the population [12].

Given the increase in water levels under the normal (Figure 5c), rainy (Figure 5d), and very rainy (Figure 5e) regimes, rainfall distribution tended to be similar, with the lowest values recorded in the centre and east of the state and the highest values along the coast and in the mountains and plateaus.

In this respect, of all the regions, Central Sertão and Inhamuns and Jaguaribana differed the most, with the lowest rainfall indices in each of the scenarios. Similar results were found by Andrade et al. [32], Rocha et al. [24], and Nogueira et al. [8] and are associated with the geomorphological model characteristic of these regions, known as the Sertaneja Depression [68].

The Sertaneja Depression is characterised by flat to undulating terrain with crystalline bedrock and low altitudes, and it is surrounded by massifs and plateaus [68]. Since altitude is a major factor in the formation of rainfall, areas at higher altitudes have higher rainfall indices, while areas at lower altitudes are associated with less rainfall [69].

It should be noted that interannual rainfall variability in Ceará is influenced by the sea surface temperature (SST) of the Equatorial Pacific Ocean and the Tropical Atlantic [11,59,60]. An increase in the SST of the Pacific Ocean is known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), and it interferes with the global circulation of air masses, resulting in limited cloud formation in the northeast of Brazil. This means that dry years in the semi-arid region of Brazil are associated with the ENSO phenomenon [70,71].

Furthermore, the SST of the South Atlantic, which is warmer than that further north, also affects the rainfall regime in Ceará [27]. This condition, known as a negative dipole, causes the Intertropical Convergence Zone to migrate to the southern hemisphere, leaving it in the right position to produce rainfall in the region [13,61,72]. Dry and very dry years result from a medium- to high-intensity El Niño associated with a neutral to positive dipole [54], while normal and rainy years occur when a neutral to weak El Niño is associated with a negative dipole.

In addition to these phenomena, La Niña also influences rainfall patterns in the region, producing rainy years when occurring with moderate or weak intensity together with a negative dipole, whereas a neutral to weak La Niña associated with a neutral to positive dipole tends to result in average or below-average rainfall [13,73].

Ceará is, therefore, characterised by temporal and spatial rainfall uncertainty (Table 2; Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). Despite the total annual rainfall being an important factor, its regular distribution plays a critical role, especially since consecutive dry days are common during the rainy season [3,24,74].

3.1.2. Consecutive Dry Days

There was a marked number of consecutive dry days in Ceará throughout the period under evaluation (1990 to 2019). A total of 39,382 CDDs were recorded, classified as follows: 26,386 (67%) lasting from 5 to 10 days (CDD1); 6219 (16%) lasting from 11 to 15 days (CDD2); and 6777 (17%) lasting more than 15 days (CDD3) (Table 3). Consecutive dry days are caused by environmental conditions that prevent the formation of rain clouds, such as the presence of warm, dry air, where a lack of humidity prevents the air from rising into the atmosphere to form clouds [5].

Table 3.

Total CDDs (1990–2019) by homogeneous rainfall region in the state of Ceará.

The highest incidences of consecutive dry days were recorded in the Central Sertão and Inhamuns, Cariri, and Jaguaribana regions, with 9562, 6734, and 5575 phenomena, respectively. It should be noted that the regions with the lowest rainfall indices recorded a greater frequency of consecutive dry days. Furthermore, consecutive dry days lasting 11 to 15 days and over 15 days showed an annual return period in the semi-arid regions such as Central Sertão and Inhamuns, Cariri, and Jaguaribana. Meanwhile, in the mountainous regions, such as the Baturité Massif and Ibiapaba, as well as in the coastal areas, including the Coastal Region of Fortaleza and the Northern Coast, medium and long CDDs recorded a return period of 2 years (Table 3).

Oliveira et al. [75] and Fernandes [35] analysed rainfall data from 1974 to 2012 for Ceará, obtaining approximate values for the frequency of consecutive dry days of 66% for CDD1, 20% for CDD2, and 14% for CDD3. However, according to the authors, there was a total of 12,061 CDD events, fewer than the 39,382 CDDs in the present study.

The difference in the number of events may be associated with two factors: sample size and the period under evaluation. Despite Oliveira et al. [75] and Fernandes [35] considering a period of 39 years, they used only 77 rainfall stations distributed throughout Ceará. In this study, we used 184 rainfall stations with a historical series from 1990 to 2019, including the droughts of 2012 and 2019, factors that may have directly influenced the count of drought events.

Corroborating the results in Table 4, the Kruskal–Wallis test showed that the rainfall regions differed in the number of CDDs lasting from 5 to 10 days in the very dry [X2(2) = 28.092; p < 0.01]; dry [X2(2) = 22.965; p < 0.01]; normal [X2(2) = 33.056; p < 0.01]; rainy [X2(2) = 45.029; p < 0.01]; and very rainy [X2(2) = 69.512; p < 0.01] water scenarios (Table 4).

Table 4.

Number of CDDs lasting from 5 to 10 days by homogeneous rainfall region for different water scenarios.

In addition to the differences between the homogeneous rainfall regions, the spatial positioning of CDDs is important for visualising areas of climate risk that require interventions and alternative actions to guarantee a water supply and increase agricultural production [4,21,75,76].

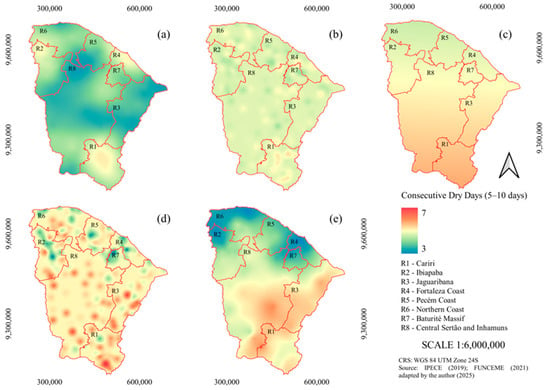

In the very dry scenario, there were between three and five CDD1 events, which were more frequent in the coastal area of Fortaleza and in Cariri (Figure 6a), regions that differed statistically from Jaguaribana (Table 4). This can be attributed to the fact that in these regions, the greatest volume of rainfall is concentrated in the very dry scenario (Figure 5a). The smallest number of CDD1 events was recorded in the central, eastern, and northwestern regions of the state, or more precisely, in parts of the Central Sertão and Inhamuns and Jaguaribana. It is important to remember that in years of reduced rainfall, the lower occurrence of short CDDs suggests an increase in prolonged drought events [24,36,76].

Figure 6.

Mean number of CDDs lasting from 5 to 10 days under the (a) very dry, (b) dry, (c) normal, (d) rainy, and (e) very rainy regimes.

In the dry regime, CDD1 had between four and five events, with Cariri standing out in relation to Ibiapaba and the Coastal Region of Pecém (Figure 6b). Cariri had the greatest occurrence of consecutive dry days (5 to 10 days), while in Ibiapaba and the Coastal Region of Pecém, the number of CDD1 events was lower (Table 4). It should also be noted that in scenarios with a water restriction, the presence of CDD1 indicates shorter periods with no rainfall, i.e., more uniform rainfall even in the face of water scarcity [4].

In normal years, there were four to six CDD1 phenomena (Figure 6c), with an increase in consecutive dry days when approaching the southern part of Ceará. The frequency of CDD1 events in the Cariri region was higher than recorded in the coastal region and mountainous areas (Table 4). This may be associated with the reduced influence of ocean humidity in the Cariri region due to being further from the coast, which intensifies the effects of phenomena such as the positive dipole and El Niño [65,77].

Dunn’s test showed that for CDD1, there were few differences between the regions, especially in the very dry, dry, and normal water scenarios (Table 4). The slight variation between the homogeneous rainfall regions shows that the entire state of Ceará is affected by consecutive dry days in extreme drought scenarios.

During rainy years, there were three to seven CDD1 events (Figure 6d). The lowest frequencies were generally seen in the coastal region of Fortaleza, the Baturité Massif, and in the northern and southern regions of Ibiapaba. This may be due to the coastal area being the most influenced by the Intertropical Convergence Zone, which results in regular and intense rainfall [70], whereas mountainous regions experience orographic rainfall, where obstacles, such as mountains, cause the humid air mass to rise, leading to vapour condensation, cloud formation, and rainfall [3,5,31,78].

Finally, under the very rainy regime, there were between three and six CDD1 events (Figure 6e), with a greater difference between locations (Table 4). The Cariri, Jaguaribana, and Central Sertão and Inhamuns regions recorded a higher frequency of CDDs lasting from 5 to 10 days compared to the other regions.

As to the behaviour of CDDs lasting from 5 to 10 days, it should be noted that the Central Sertão and Inhamuns and Jaguaribana regions saw an increase in the number of short-duration CDDs as the rainfall increased, meaning a reduction in events of longer duration. According to Nogueira et al. [8], CDDs of from 5 to 10 days are the most frequent all over Ceará; however, the number of short-duration CDDs tends to decrease as the number of consecutive dry days increases.

In all the water scenarios, ranging from extremely dry to very rainy conditions, Cariri stood out with a predominance of CDDs lasting from 5 to 10 days (CDD1). It should be noted that the Cariri region is characterised by the presence of the Araripe Plateau, a geomorphological structure that acts as a barrier to the movement of the humid winds of the Intertropical Convergence Zone [68], such that the spatial distribution of the rainfall depends on the location of the municipalities in the region in relation to the plateau [79]. As a result, the number of CDD1 events between leeward and windward regions can vary by ±2 events.

For consecutive dry days lasting from 11 to 15 days, the Kruskal–Wallis test showed significant statistical differences between the homogeneous rainfall regions under the very dry [X2(2) = 21.916; p < 0.01], normal [X2(2) = 64.887; p < 0.01], rainy [X2(2) = 56.549; p < 0.01], and very rainy [X2(2) = 98.849; p < 0.01] regimes (Table 5).

Table 5.

Number of CDDs lasting from 11 to 15 days by homogeneous rainfall region for different water scenarios.

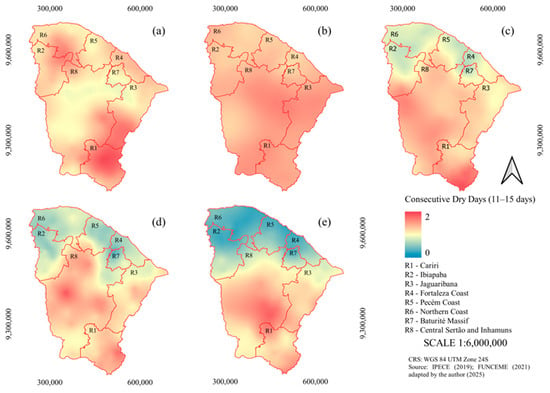

CDD2 varied from one to two phenomena under very dry (Figure 7a), dry (Figure 7b), and normal conditions (Figure 7c). Under the very dry regime, the only difference was seen in Cariri, which stood out for the number of CDD2 events compared to the Baturité Massif and the Central Sertão and Inhamuns regions (Table 5), while under the dry regime, there were no differences between the homogeneous rainfall regions (Table 5). Under the normal regime, Cariri and Central Sertão and Inhamuns differed from the other locations, and they were found to have the highest number of CDDs.

Figure 7.

Mean number of CDDs lasting from 11 to 15 days under the (a) very dry, (b) dry, (c) normal, (d) rainy, and (e) very rainy regimes.

Under the rainy (Figure 7d) and very rainy (Figure 7e) regimes, there were from zero to two CDD2 events. Cariri and Central Sertão and Inhamuns differed from the other homogeneous rainfall regions, with the exception of Jaguaribana. There was a reduction in the number of CDD2 events in the coastal and mountainous regions as water availability increased, with the Central Sertão and Inhamuns and Cariri regions being the most affected by CDDs lasting from 11 to 15 days.

Despite the increase in rainfall, the Central Sertão and Inhamuns region continues to experience difficulties with cloud formation and poor rainfall distribution. Similar results were found by Rocha et al. [18], who studied the occurrence of CDDs and found that CDD2-type events were limited to the southern part of the Central Sertão and Inhamuns region.

Furthermore, Sakamoto et al. [46] observed the same pattern and correlated CDDs of more than 10 days with a loss of up to 73% in temporary-crop production. For Mbanyele et al. [23], medium and long dry periods had a negative impact on rainfed agriculture, resulting in a significant loss in crop productivity.

For CDDs of more than 15 days, the Kruskal–Wallis test showed differences in the homogeneous rainfall regions for each of the scenarios, with CDD3 differing statistically under the very dry [X2(2) = 58.660; p < 0.01], dry [X2(2) = 67.310; p < 0.01], normal [X2(2) = 71.085; p < 0.01], rainy [X2(2) = 82.537; p < 0.01], and very rainy [X2(2) = 44.516; p < 0.01] regimes (Table 6).

Table 6.

Number of CDDs lasting longer than 15 days by homogeneous rainfall region for different water scenarios.

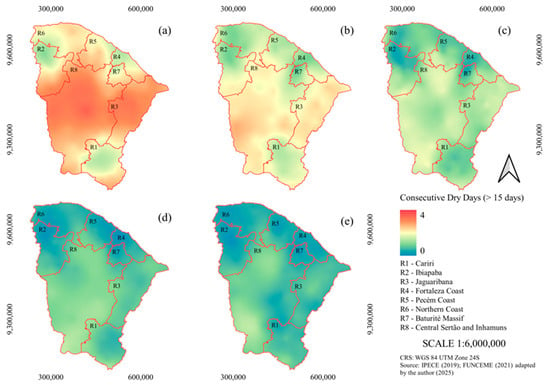

When evaluating the spatial distribution of CDDs of more than 15 days (CDD3), the highest occurrence was recorded during very dry years, with values of one to four phenomena (Figure 8). The highest frequencies of CDD3 were concentrated in the Central Sertão and Inhamuns and Jaguaribana regions (Figure 8a), compared to the other areas (Table 4). It should be noted that locations with a greater number of CDD3 events had fewer CDD1 events, indicating that the lower the number of short CDDs, the greater the possibility of CDDs of longer duration.

Figure 8.

Mean number of CDDs of more than 15 days under the (a) very dry, (b) dry, (c) normal, (d) rainy, and (e) very rainy regimes.

In the dry scenario, the frequency of CDD3 varied from one to three events (Figure 8b). In addition, the spatial distribution under the dry regime followed the same behaviour as in the previous scenario. The regions most affected by CDD3 were Jaguaribana and Central Sertão and Inhamuns, characterised by negative rainfall and the frequent occurrence of CDD3 [18].

Under the normal regime, CDD3 varied between zero and two events (Figure 8c), following the same pattern as the previous regimes, in which the Central Sertão and Inhamuns and Jaguaribana regions differed from the other locations. These regions are characterised by poor rainfall distribution, even in years of normal rainfall, where the irregularity of the rainfall during the rainy season results in long dry periods at these locations [24]. As such, even in scenarios where the water supply is greater, these regions experience no temporal changes in rainfall, only an increase in rainfall depth [8].

Under rainy conditions, the number of CDD3 events varied from zero to two (Figure 8d). In this scenario, the Central Sertão and Inhamuns region stood out for the high frequency of drought events lasting more than 15 days. On the other hand, the lowest number of CDD3 events was recorded in the coastal region, the mountains (Ibiapaba and the Baturité Massif), southern Jaguaribana, and central Cariri.

Under the very rainy regime, there were from zero to two CDD3 events (Figure 8e), with weaker events in more than half the state. However, even in the high rainfall scenario, some municipalities are still likely to face problems due to the uneven rainfall distribution. Similar issues were found by Sakamoto et al. [46], Andrade et al. [32], Rocha et al. [24], and Souza et al. [36].

The Central Sertão and Inhamuns region had the greatest number of CDDs of more than 15 days in each of the water scenarios. In addition to the above issues, this is associated with problems of cloud formation and rainfall distribution in the region [80]. As a result, the location is particularly susceptible to longer-term CDDs [8]. According to Seigerman et al. [67], the Sertão is the region most impacted by natural disasters: of the 3438 drought events recorded between 1991 and 2019, approximately 1480 occurred at this location, corresponding to around 40% of the natural disasters in the state of Ceará during this period [13].

The increase in prolonged periods of drought in the Central Sertão and Inhamuns region shows how difficult it is to develop rainfed agriculture in the area [18,24,35,46]. It should also be noted that the increase in consecutive dry days increases the possibility of affecting different phases of the phenological cycle, especially those most sensitive to water shortage [23,81]. The longer the dry period, the less the soil water is replenished, and the smaller the guarantee of an adequate supply of water for the plant, affecting both metabolic activity and crop productivity [7,22].

3.2. Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) Productivity

The average area planted with cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) was 529,000 hectares per year, distributed across the eight pluviometrically homogeneous regions. In this context, the Central Sertão and Inhamuns region stands out, with approximately 20% of its area dedicated to the crop each year, while the other regions allocate around 2 to 5% of their territory (Figure 9). The low values are associated with the fact that cowpea is predominantly grown for family consumption [17], playing an important role in combating malnutrition and supporting the food sovereignty of the population [82].

Figure 9.

Land use and land cover in the state of Ceará in 1990 and 2019 and the area planted with cowpea from 1990 to 2019.

Average cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) productivity in the state of Ceará was 286 ± 85 kg ha−1, a value below the productive potential of the species. Similar results were obtained in research carried out in the semi-arid region of Brazil, where Vasconcelos et al. [83] found an average yield of 273 ± 93 kg ha−1 for Ceará, and Silva et al. [20] found a productivity of 360 kg ha−1 in Paraíba. Compare this to other regions of Brazil, such as the Central-West, where productivity reached 1008 kg ha−1 under a rainfed regime [84].

The low yield in the region may be associated with extensive crop management, the poor use of technology by producers, and climate variability [7,85]. It should also be noted that Ceará had 39,382 CDDs between 1990 and 2019, which, together with the above factors, affects the productive capacity of the state. Other contributing factors are the low level of education of the farmers and the lack of technical assistance and rural extension [86,87].

The yield of temporary crops, such as Vigna unguiculata, changes each year depending on the spatial and temporal distribution of the rainfall [83]. Based on the results for rainfall distribution and consecutive dry days, cowpea yields differed between the homogeneous rainfall regions in each of the water scenarios: very dry [X2(2) = 46.458; p < 0.01], dry [X2(2) = 43.185; p < 0.01], normal [X2(2) = 49.990; p < 0.01], rainy [X2(2) = 73.103; p < 0.01], and very rainy [X2(2) = 87.054; p < 0.01] (Table 7).

Table 7.

Analysis of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) productivity by homogeneous rainfall region for different water scenarios in the state of Ceará.

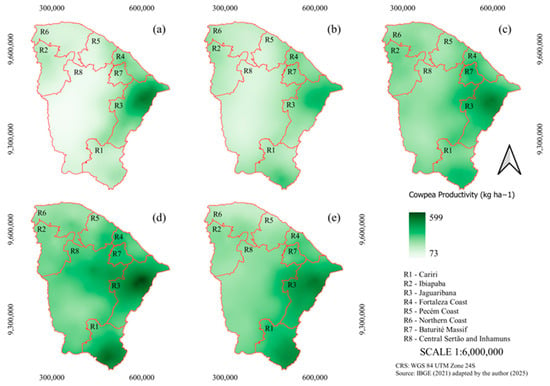

From a spatial perspective, in one very dry (Figure 10a) and one dry (Figure 10b) scenario, the productivity recorded in the Central Sertão and Inhamuns region was lower than in Jaguaribana, the Coastal Region of Fortaleza, or the Baturité Massif, as shown in Table 7. In addition to the factors already discussed, approximately 25% of the Central Sertão and Inhamuns region is occupied by Leptosols (Figure 2). These soils are characterised by low depth, high stoniness, and reduced water-holding capacity, which exacerbate the effects of water scarcity in the region [44].

Figure 10.

Average cowpea productivity (kg ha−1) under (a) very dry, (b) dry, (c) normal, (d) rainy, and (e) very rainy regimes.

In a normal year (Figure 10e), the homogeneous rainfall regions of Jaguaribana and the Baturité Massif achieved the highest values for cowpea productivity (Table 7). It should be noted that the Baturité Massif benefits from deep soils that allow water to be stored and reduce water stress during consecutive dry days [17]. Thus, the presence of Acrisols, covering 36% and 25% of the Baturité Massif and Jaguaribana areas, respectively (Figure 2), contributes to more favourable agricultural conditions in these regions. Furthermore, Jaguaribana relies on the River Jaguaribe to supply water to the region [82].

During the rainy season (Figure 10d), cowpea productivity increased in Jaguaribana, Cariri, and the Baturité Massif, while during the very rainy season (Figure 7e), productivity in the Cariri and Jaguaribana regions was higher than that of the other regions (Table 7).

It should be noted that the positive performance seen in Jaguaribana is dependent on the presence of the Jaguaribe Apodi Irrigated Perimeter, where the water supply is guaranteed by the River Jaguaribe [88]. Conversely, Cariri experiences a reduced number of long CDDs (Figure 6), guaranteeing the water supply throughout the crop cycle.

Furthermore, the very rainy scenario saw a fall in productivity, especially in municipalities located in the Central Sertão and Inhamuns region, as well as in regions along the coast; this is linked to the high intensity of the rainfall throughout this scenario, resulting in torrential downpours that can saturate and erode the soil. Excess water in the soil can carry away nutrients, cause the plants to rot, and encourage the proliferation of pests and diseases [12,20,24].

3.3. Correlation Between Variables of the Rainfall Regime

Under very dry to normal water conditions, CDD3 showed a negative correlation with CDD1, CDD2, rainfall, and cowpea productivity (Table 8). The occurrence of long dry spells is, therefore, linked to reduced rainfall and has a negative impact on productivity. It should also be noted that the occurrence of CDD3 indicates a reduction in the number of short and moderate events, such as CDD1 and CDD2.

Table 8.

Spearman’s correlation coefficient between the variables CDD1, CDD2, CDD3, rainfall, and cowpea productivity under the very dry, dry, normal, rainy, and very rainy regimes.

Under very dry conditions, CDD1 showed a positive correlation with rainfall. This suggests that the occurrence of CDDs of up to 10 days under conditions of water scarcity is a positive factor, leading to more regular rainfall distribution due to the small number of days with no rainfall [8,22]. However, under the rainy and very rainy regimes, the negative correlation between rainfall and consecutive dry days intensified regardless of the duration. This shows that scenarios with more rainfall are linked to fewer consecutive dry days.

Productivity and rainfall showed a positive association in the very dry, dry, and normal water scenarios; however, in the rainy and very rainy scenarios, the correlations between the variables were negative. This is related to the greater regularity and intensity of the rainfall, which often results in torrential downpours and flooding [13], while the cowpea is sensitive to water surplus [20,89]. The effects of extreme rainfall on agriculture can be as damaging as those caused by dry periods [90].

In this respect, consecutive dry days can help mitigate the effects of heavy rainfall on agriculture given the positive correlation between cowpea productivity and both CDD1 and CDD2 (Table 8). This shows that the crop benefited from CDDs of up to 15 days during its development cycle under extremely rainy conditions. This is linked to the potential for CDDs to contribute to soil drainage and water evaporation, helping to reduce flooding and minimise prolonged crop damage.

Extremely dry or rainy years are, therefore, subject to a marked fall in productivity. In the very dry scenario, this is due to prolonged CDDs and lower rainfall, while during rainy years, there is an excess of water [31], which hampers the establishment and growth of the crops [24]. Under such conditions, it is essential to adopt measures that are adapted to climate variability to reduce the uncertainty surrounding rainfed agriculture [3,7,29].

Correlations that showed low yet significant values reflect the limited influence of other factors not directly considered, such as soil classes, temperature, topography, and the presence of pests and diseases.

4. Conclusions

This study allowed for a comprehensive understanding of rainfall dynamics, consecutive dry days, and cowpea productivity under different water-availability scenarios in the semi-arid region of Ceará. The results demonstrated that the distribution of rainfall and the duration of consecutive dry days are spatially heterogeneous, directly influencing agricultural productivity.

The Central Sertão and Inhamuns region showed greater susceptibility to water deficits and lower cowpea productivity, highlighting the need for preventive planning and adaptive management strategies to mitigate the impacts of drought. Under extreme conditions, the relationship between consecutive dry days and rainfall revealed complex patterns, with positive correlations in very dry years and behavioural shifts under wetter regimes.

Furthermore, the correlations between rainfall regime variables and cowpea productivity confirmed that both water deficit and surplus negatively affect yields. Future studies may include additional variables, such as temperature and soil characteristics, or apply this methodology to other crops, thereby expanding its analytical potential and contributing to improving the climate resilience of agricultural systems in the semi-arid region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.d.S.d.S., F.B.L. and E.M.d.A.; methodology, M.d.S.d.S., F.B.L. and F.J.d.O.L.; software, F.J.d.O.L.; validation, M.d.S.d.S. and F.J.d.O.L.; formal analysis, M.d.S.d.S., F.B.L., F.J.d.O.L. and F.T.F.N.; investigation, M.d.S.d.S. and F.B.L.; resources, F.B.L. and E.M.d.A.; data curation, M.d.S.d.S. and F.T.F.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.d.S.d.S.; writing—review and editing, M.d.S.d.S., F.B.L., E.M.d.A., F.J.d.O.L., F.T.F.N., F.H.O.d.S., A.C.M.M., N.R.d.S.L., M.C.P., L.C.P. and E.T.C.; visualization, M.d.S.d.S., F.B.L., E.M.d.A., F.J.d.O.L., F.T.F.N., F.H.O.d.S., A.C.M.M., N.R.d.S.L., M.C.P., L.C.P. and E.T.C.; supervision, F.B.L. and E.M.d.A.; project administration, F.B.L. and E.M.d.A.; funding acquisition, F.B.L. and E.M.d.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed in part by the National Council for Scientific and Technology Development (CNPq), process no. 130701/2020-3; the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), process no. 8887.705369/2022-0; Project Brazil and Trentino: news opportunities for co-development 2019; and the Graduate in Agricultural Engineering of the Federal University of Ceará—PPGEA/UFC.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the Graduate Program in Agricultural Engineering of the Federal University of Ceará (PPGEA-UFC) and to the Extension Group on Water and Soil Management in the Semi-Arid Region (MASSA) of the same institution for their support and contribution to academic and scientific development. The authors also thank the project “Brasil e Trentino: new opportunities for co-development 2019” for the valuable opportunity for international cooperation, exchange of experiences, and acquisition of knowledge, which greatly enriched the development of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| BSh’ | A type of dry semi-arid climate according to the Köppen classification |

| CDD | Consecutive Dry Days |

| CDD1 | Consecutive Dry Days (5–10 days) |

| CDD2 | Consecutive Dry Days (11–15 days) |

| CDD3 | Consecutive Dry Days (>15 days) |

| CENTEC | Technological Education Center Institute |

| CRS | Coordinate Reference System |

| EMATERCE | Rural Assistance and Extension Company of Ceará |

| HRR | Homogeneous Rainfall Regions |

| IBGE | Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics |

| IDAM | Institute for Sustainable Agricultural and Forestry Development of the State of Amazonas |

| IPECE | Ceará Institute of Economic Research and Strategy |

| ITCZ | Intertropical Convergence Zone |

| IUSS | International Union of Soil Sciences |

| QGIS | Quantum Geographic Information System |

| R | Correlation Coefficients |

| R1 | Cariri |

| R2 | Ibiapaba |

| R3 | Jaguaribana |

| R4 | Coastal Region of Fortaleza |

| R5 | Coastal Region of Pecém |

| R6 | Northern Coastal Region |

| R7 | Baturité Massif |

| R8 | Central Sertão and Inhamuns |

| SAB | Brazilian Semi-Arid |

| SIDRA | IBGE Automatic Recovery System |

| SST | Sea Surface Temperature |

| UFC | Federal University of Ceará |

| UFCA | Federal University of Cariri |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

| UTM | Universal Transverse Mercator |

| WGS 84 | World Geodetic System 1984 |

Appendix A. Script for Quantifying Consecutive Dry Days

- Note: The square brackets used in the code (e.g., row [4], row [5]) are part of the Python syntax for accessing list elements and are not related to bibliographic references.

| import csv import numpy as np d = [] dia = 0 mes = 0 ano = 0 prec = [] precipitacao = 0 count = 0 V1 = 0 V2 = 0 V3 = 0 lista_postos = [‘60-independencia1’, ‘115-Pentecoste’] for jj in range (0, len (lista_postos)): # print (‘C:\\Users\\josiv\\Documents\\programas_python\\{0}.txt’.format (lista_postos [j])) arquivo = open (‘C:\\Users\\josiv\\Documents\\programas_python\\veranicos\\{0}.txt’.format (lista_postos [jj]), ‘w’) arquivo.write (‘ano; CDD1; CDD2; CDD3\n’) with open (‘C:\\Users\\josiv\\Documents\\programas_python\\{0}.txt’.format (lista_postos [jj])) as f: csv_reader = csv.reader (f, delimiter = ‘;’) cabecalho = next (csv_reader, None) prec = [] for row in csv_reader: ano = int (row [4]) mes = int (row [5]) prec.append (ano) prec.append (mes) prec.append (row [7:]) # print (prec) for z in range (0, len (prec), 3): # print (prec [z]) #printa o ano # print (prec [z + 1]) #printa o mes # print (prec [z + 2]) #printa a precipitacao for j in prec [z + 2]: precipitacao = float (j) if np.isnan (precipitacao) == True or precipitacao == 888.0 or precipitacao == 999.0 or prec [z] < 1990 or prec [z] > 2019: pass else: if prec [z + 1] <= 5 and precipitacao < 2.0: # print (‘mes = ’, prec [z + 1], ‘ano =’, prec [z], precipitacao) count += 1 # print (count) if 5 == count: V1 += 1 # print (‘V1 =’, V1, ‘V2 =’, V2, ‘V3 =’, V3) elif 11 == count: V2 += 1 # print (‘V1 =’, V1, ‘V2 =’, V2, ‘V3 =’, V3) elif 15 == count: V3 += 1 # print (‘V1 =’, V1, ‘V2 =’, V2, ‘V3 =’, V3) else: count = 0 # pass # print (prec [z], prec [z + 1], ‘V1 =’, V1, ‘V2 =’, V2, ‘V3 =’, V3) if prec [z + 1] == 5: if V2 >= 1 and V1 >= V2: V1 = V1 − V2 # print (prec [z], prec [z + 1], ‘V1 =’, V1, ‘V2 =’, V2, ‘V3 =’, V3) if V3 >= 1 and V2 >= V3: V2 = V2 − V3 arquivo.write (‘{0}; {1}; {2}; {3}\n’.format (prec [z], V1, V2, V3)) print (lista_postos [jj], prec [z], prec [z + 1], ‘V1 =’, V1, ‘V2 =’, V2, ‘V3 =’, V3) V1 = 0 V2 = 0 V3 = 0 |

References

- Coppus, R. The Global Distribution of Human-Induced Land Degradation and Areas at Risk: SOLAW21 Technical Background Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023; pp. 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rockstrom, J.; Hatibu, N.; Oweis, T.Y.; Wani, S.; Barron, J.; Bruggeman, A.; Farahani, J.; Karlberg, L.; Qiang, Z. Managing water in rainfed agriculture. In Water for Food, Water for Life a Comprehensive Assessment of Water Managament in Agriculture; Molden, D., Ed.; Earthscan: London, UK; International Water Management Institute (IWMI): Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2007; pp. 315–352. [Google Scholar]

- Gobin, A.; Vyver, H. Spatio-temporal variability of dry and wet spells and their influence on crop yields. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 308, 108565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, B.C.C.; Oliveira Júnior, J.F.; Pereira, C.R.; Sobral, B.S.; Gois, G.; Lyra, G.B.; Machado, E.A.; Correia Filho, W.L.F.; Souza, A. Spatiotemporal variation of dry spells in the State of Rio de Janeiro: Geospatialization and multivariate analysis. Atmos. Res. 2021, 257, 105612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltaci, H.; Arslan, H. Seasonal and regional variability of wet and dry spell characteristics over Turkey. Atmos. Res. 2022, 270, 106083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marumbwa, F.M.; Cho, M.A.; Chirwa, P.W. Analysis of spatio-temporal rainfall trends across southern African biomes between 1981 and 2016. Phys. Chem. Earth (Pt A B C) 2019, 114, 102808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, S.K.; Sandeep, V.M.; Kumar, P.V.; Pramod, V.P.; Manikandan, N.; Rao, C.S.; Singh, N.P.; Bhaskar, S. Assessing impact of dry spells on the principal rainfed crops in major dryland regions of India. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 313, 108768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, D.B.; Silva, A.O.; Giroldo, A.B.; Silva, A.P.N.; Costa, B.R.S. Dry spells in a semi-arid region of Brazil and their influence on maize productivity. J. Arid Environ. 2023, 209, 104892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.H.O.; Lopes, F.B.; Bezerra, B.G.M.; Viana, N.S.; Araújo, I.C.S.; Luna, N.R.S.; Pontes, M.C.; Cavalcante, R.R.; Aragão, F.T.A.; Andrade, E.M. Impact of Permanent Preservation Areas on Water Quality in a Semi-Arid Watershed. Environments 2025, 12, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.N.; Becker, C.T.; Brito, J.I.B. Análise das séries temporais de precipitação do semiárido paraibano em um período de 100 anos-1911 a 2010. Rev. Bras. Geogr. Fís. 2013, 6, 680–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, E.M. Caatinga, the tropical dry forest: The certainties and uncertainties of water. TRIM 2017, 12. Available online: https://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/23593 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Coutinho, M.D.L.; Gomes, A.C.S.; Morais, M.D.C.; Sakamoto, M.S. Análise comparativa do regime pluviométrico entre anos secos e chuvosos na bacia do Rio Piranhas Açu. Anu. Inst. Geociênc. 2018, 41, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.A.S.; Lira, M.A.T. A Variabilidade Climática e os Desastres Naturais no Estado do Ceará (1991–2019). Rev. Bras. Meteorol. 2021, 36, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, B.D.; Coutinho, M.D.L.; Sakamoto, M.S.; Jacinto, L.V. Uma análise sobre as chuvas no Ceará baseada nos eventos de el niño, la niña e no dipolo do servain durante a estação chuvosa. RBClima 2021, 28. Available online: https://revistas.ufpr.br/revistaabclima/article/view/76238/43620 (accessed on 30 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations, Trees, Forests and Land Use in Drylands the First Global Assessment—Full Report; FAO Forestry: Rome, Italy, 2019; pp. 11–20.

- Superintendência Do Desenvolvimento Do Nordeste. Delimitação do Semiárido. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.br/sudene/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/02semiaridorelatorionv.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Instituto Brasileiro De Geografia E Estatística. Censo Agropecuário 2017; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2017.

- Rocha, T.B.C.; Vasconcelos Júnior, F.C.; Silveira, C.S.; Martins, E.S.P.R.; Silva, R.F.V. Veranicos no Ceará e Aplicações para Agricultura de Sequeiro. Rev. Bras. Meteorol. 2020, 35, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.M.; Martins, S.C.; Borges, W.L. Correção da acidez, adubação e fixação biológica. In Feijão-Caupi do Plantio à Colheita, 1st ed.; Vale, J.C., Bertini, C., Borém, A., Eds.; Ed. UFV: Viçosa, Brasil, 2017; pp. 52–69. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A.B.; Mesquita, R.M.; Guimarães, M.A.; Lemos Neto, H.S.; Silva, T.M. Exigências edafoclimáticas e ecofisiologia. In Feijão-Caupi do Plantio à Colheita, 1st ed.; Vale, J.C., Bertini, C., Borém, A., Eds.; Ed. UFV: Viçosa, Brasil, 2017; pp. 52–69. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L.D.R.; Cartaxo, P.H.A.; Silva, M.C.; Gonzaga, K.S.; Araújo, D.B.; Sousa, E.S.; Santos, J.P.O. Efeito da variabilidade pluviométrica na produção de Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp. no Semiárido da Paraíba. Sci. Electron. Arch. 2020, 13, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, F.B.P.; Lacerda, C.F.; Andrade, E.M.; Neves, A.L.R.; Sousa, C.H.C. Efeito de manejos do solo no déficit hídrico, trocas gasosas e rendimento do feijão-de-corda no semiárido. Rev. Ciênc. Agron. 2015, 46, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mbanyele, V.; Mtambanengwe, F.; Nezomba, H.; Groot, J.C.J.; Mapfumo, P. Combinations of in-field moisture conservation and soil fertility management reduce effect of intra-seasonal dry spells on maize under semi-arid conditions. Field Crops Res. 2021, 270, 108218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, T.B.C.; Vasconcelos Junior, F.C.; Silveira, C.S.; Martins, E.S.P.R.; Gonçalves, S.T.N.; Silva, E.M.; Alves, J.M.B.; Sakamoto, M.S. Indicadores de Veranicos e de Distribuição de Chuva no Ceará e os Impactos na Agricultura de Sequeiro. Rev. Bras. Meteorol. 2021, 36, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y. Effects of rainfall regime during the growing season on the annual plant communities in semiarid sandy land, northeast China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 43, 02456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, E.S.; Lacerda, C.F.; Mesquita, R.O.; Melo, A.S.; Ferreira, J.F.S.; Teixeira, A.S.; Lima, S.C.R.V.; Sales, J.R.S.; Silva, J.S.; Gheyi, H.R. Supplemental irrigation with brackish water improves carbon assimilation and water use efficiency in maize under tropical dryland conditions. Agriculture 2022, 12, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, M.J.S.; Andrade, E.M.; Abreu, I.; Lajinha, T. Long-term variation of precipitation indices in Ceará State, Northeast Brazil. Int. J. Climatol. 2013, 33, 2929–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liu, F.; Xue, Y.; Sun, S. The spatial and temporal analysis of precipitation concentration and dry spell in Qinghai, northwest China. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2015, 29, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, S.Q.; Alobaidy, M.N.; Grigg, N.S. Resilience Appraisal of Water Resources System under Climate Change Influence Using a Probabilistic-Nonstationary Approach. Environments 2023, 10, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferijal, T.; Batelaan, O.; Shanafield, M. Spatial and temporal variation in rainy season droughts in the Indonesian Maritime Continent. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 126999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.S.; Lu, J.; Yeh, H. Multi-Index Drought Analysis in Choushui River Alluvial Fan, Taiwan. Environments 2024, 11, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, E.M.; Sena, M.G.T.; Silva, A.G.R.; Pereira, F.J.S.; Lopes, F.B. Uncertainties of the rainfall regime in a tropical semi-arid region: The case of the State of Ceará. Agro@mbiente On-Line 2016, 10, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, D.A.; Andrade, E.M. Seasonal trend of climate variables in an area of the Caatinga phytogeographic domain. Revista Agro@mbiente 2021, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Gao, Y.; Hou, E. Spatial and temporal variation of precipitation during 1960–2015 in Northwestern China. Nat. Hazards Obs. 2021, 109, 2173–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, F.B.P. Disponibilidade Hídrica para a Cultura do Feijão-de-Corda em Função do Manejo de Solo no Semiárido Cearense. Ph.D. Thesis, Centro de Ciências Agrárias, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, M.S.; Campos, K.C.; Braga, F.L.P.; Lopes, F.B. Determinantes do regime pluviométrico no Semiárido Cearense (1990–2019). RBClima 2024, 34, 533–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro De Geografia E Estatística. Censo 2022: População e Domicílios; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2023.

- Andrade, E.M.; Aquino, D.N.; Chaves, L.C.G.; Lopes, F.B. Water as Capital and Its Uses in the Caatinga. In Caatinga, 1st ed.; Silva, J.M.C.S., Leal, I.R., Tabarelli, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 281–302. [Google Scholar]

- Caitano, R.F.; Lopes, F.B.; Teixeira, A.S. Estimativa da aridez no Estado do Ceará usando Sistemas de Informação Geográfica. In Proceedings of the XV Simpósio Brasileiro de Sensoriamento Remoto, Curitiba, Brasil, 30 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Koeppen, W. Climatologia: Con un Studio de los Climas de la Tierra; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Mexico City, Mexico, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Xavier, T.M.B.S. Tempo de Chuva: Estudos Climáticos e de Previsão para o Ceará e Nordeste Setentrional; Ed. ABC: Fortaleza, Brazil, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rainfall Gauges of the Ceará Foundation for Meteorology and Water Resources. Available online: http://www.funceme.br/?page_id=2694 (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Jacomine, P.K.T.; Almeida, J.C.; Medeiros, L.A.R. Levantamento Exploratório—Reconhecimento de Solos do Estado do Ceará, 1st ed.; SUDENE: Recife, Brazil, 1973.

- International Union of Soil Sciences, World Reference Base for Soil Resources, 4th ed.; IUSS: Vienna, Austria, 2004.

- Wang, W.; Shao, Q.; Peng, S.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, W.; An, G.; Yong, B. Spatial and temporal characteristics of changes in precipitation during 1957–2007 in the Haihe River basin, China. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2011, 25, 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, M.S.; Ferreira, A.G.; Costa, A.C.; Olivas, E.S. Rainy season pattern and impacts on agriculture and water resources in Northeastern Brazil. In Drought: Research and Science-Policy Interfacing, 1st ed.; Andreu, J., Solera, A., Paredes-Arquiola, J., Haro-Monteagudom, D., Lanen, H., Eds.; CRC Press/Balkema: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante, E.S.; Lacerda, C.F.; Costa, R.N.T.; Gheyi, H.R.; Pinho, L.L.; Bezerra, F.M.S.; Oliveira, A.C.; Canjá, J.F. Supplemental irrigation using brackish water on maize in tropical semi-arid regions of Brazil: Yield and economic analysis. Sci. Agric. 2021, 78, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkayan, S. Conditional probabilities of ocurrence of Rainy and Dry Years Over a Large Continental Area. Hidrol. Pap. 1966, 12, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Brasileiro De Geografia E Estatística. Produção Agrícola Municipal; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2019.

- Hora de Plantar Program. Available online: https://www.sda.ce.gov.br/2014/08/21/programa-hora-de-plantar-hpnet/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- MapBiomas Land Use and Land Cover Platform. Available online: https://brasil.mapbiomas.org/colecoes-mapbiomas/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System; Open Source Geospatial Foundation: Beaverton, OR, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Caitano, R.F. Geoprocessamento na Análise de Risco de Salinização dos Solos do Estado do Ceará. Master’s Thesis, Mestrado em Engenharia Agrícola—Centro de Ciências Agrárias, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cambardella, C.A.; Moorman, T.B.; Novak, J.M.; Parkin, T.B.; Karlen, D.L.; Turco, R.F.; Konopka, A.E. Field-scale variability of soil properties in Central Iowa soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1994, 58, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, V.T.; Maidment, D.R.; Mays, L.W. Applied Hydrology, 1st ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of ranks in on-criterion variance analyses. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, W.J. Estatística Aplicada à Administração, 1st ed.; Ed. Harbra: São Paulo, Brazil, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Pires, M.C.; Castro, M.B.; Lieber, Z.V.; Menezes, T.P.; Aoki, R.Y.S. Estatística não Paramétrica Básica no Software R: Uma Abordagem por Resolução de Problemas, 1st ed.; UFMG: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2018; pp. 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, J.A.; Silva, D.F. Distribuição espaço-temporal do Índice de anomalia de chuva para o Estado do Ceará. Rev. Bras. Geogr. Fís. 2017, 10, 1002–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Souza, C.L.O.; Nogueira, V.F.B.; Nogueira, V.S. Variabilidade interanual da precipitação em cidades do semiárido brasileiro entre os anos de 1984 e 2015. Rev. Verde Agroecol. Desenvolv. Sustent. 2017, 12, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.T.F. Caracterização climática da quadra chuvosa de município do semiárido brasileiro, entre os anos de 2013 a 2017. Geogr. Atos 2020, 2, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, J.F.; Cestaro, L.A.; Queiroz, L.S. Caracterização climática da serra de Martins-RN. Rev. Geociênc. Nordeste 2021, 7, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, A.F.S.; Xavier, T.M.B.S.; Malveira, E.C.H. A Zona De Convergência Intertropical—Zcit E Sua Relação Com A Chuva Nas Principais Bacias Hidrográficas Do Ceará. In Proceedings of the XIII Simpósio Brasileiro de Recursos Hídricos, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 28 April 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Moura, M.S.B.; Sobrinho, J.E.; Silva, T.G.F. Aspectos meteorológicos do semiárido brasileiro. In Tecnologia de Convivência com o Semiárido Brasileiro; Ximenes, L.F., Silva, M.S.L., Brito, L.T.L., Eds.; Banco do Nordeste: Fortaleza, Brazil, 2019; pp. 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, A.G.; Mello, N.G.M. Principais sistemas atmosféricos atuantes sobre a região Nordeste do Brasil e a influência dos oceanos Pacífico e Atlântico no clima da região. RBClima 2005, 1, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sistemas Atmosféricos Atuantes Sobre o Nordeste. Available online: http://www.funceme.br/?p=967 (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Seigerman, C.K.; Leite, N.S.; Martins, E.S.P.R.; Nelson, D.R. At the extremes: Assessing interrelations among the impacts of and responses to extreme hydroclimatic events in Ceará, Northeast Brazil. J. Hydrol. 2024, 632, 130850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, M.E.; Shinzato, E.; Brandão, R.L.; Freitas, R.L.; Freitas, L.C.B.; Teixeira, W.G. Origem Das Paisagens. In Geodiversidade do Estado do Ceará, 1st ed.; Brandão, R.L., Freitas, L.C.B., Eds.; CPRM: Fortaleza, Brazil, 2014; pp. 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, J.O.P.; Almeida, J.D.M.; Correa, A.C.B. Caracterização e espacialização da precipitação em bacia hidrográfica com relevo complexo: Central Sertão Pernambucano–Bacia do Riacho do Saco. Rev. Geogr. 2015, 32, 2105. [Google Scholar]

- Marengo, J.A.; Alves, L.M.; Beserra, E.A.; Lacerda, F.F. Variabilidade e mudanças climáticas no semiárido brasileiro. In Recursos Hídricos em Regiões Áridas e Semiáridas, 1st ed.; Medeiros, S.S., Gheyi, H.R., Galvão, C.O., Paz, V.P.S., Eds.; Instituto Nacional do Semiárido: Campina Grande, Brazil, 2011; pp. 383–422. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, D.F.; Sousa, A.B.; Maia, L.M.; Rufino, L.L. Efeitos da associação de eventos de ENOS e ODP sobre o Estado do Ceará. Rev. Geogr. 2012, 29, 14–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, P.S.; Souza, W.M.; Silva, J.F.; Gomes, V.P. Variabilidade espaço-temporal das tendências de precipitação na mesorregião sul Cearense e sua relação com as anomalias de TSM. Rev. Bras. Meteorol. 2018, 33, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.A.; Mendes, L.M.S.; Cruz, M.L.B. Análise estatística dos anos secos e chuvosos da Sub-bacia Hidrográfica do rio Piracuruca, divisa entre os estados do Ceará e do Piauí, Brasil. Rev. Geogr. 2020, 28, 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, J.R.F.; Dantas, M.P.; Ferreira, F.E.P. Variabilidade da precipitação pluvial e produtividade do milho no semiárido brasileiro através da análise multivariada. Nativa 2019, 7, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.C.; Andrade, E.M.; Chaves, L.C.G.; Fernandes, F.B.P. Frequência e distribuição espacial de veranicos no estado do Ceará. In Proceedings of the II Simpósio Brasileiro de Recursos Naturais do Semiárido, Quixadá, Brazil, 27 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, D.B.; Nóbrega, R.S. Análise espacial e climatológica da ocorrência de veranicos no Sertão de Pernambuco. Rev. Geogr. 2010, 27, 94–106. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, D.F. Influência da variabilidade interdecadal do clima associada ao ENOS sobre o Estado do Ceará. Rev. Ibero-Am. Ciênc. Ambient. 2013, 4, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villela, H.A.S.M.; Matos, A. Hidrologia Aplicada, 1st ed.; Editora McGraw-Hil: São Paulo, Brazil, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ramires, J.; Armond, N.B.; Salgado, C.M. A variabilidade pluviométrica no Cariri cearense e a influência das teleconexões ENOS e ODP. In Proceedings of the XVII Simpósio Brasileiro de Geografia Física Aplicada, Campinas, Brazil, 29 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moro, M.F.; Macedo, M.B.; Moura-Fé, M.M.; Castro, A.S.F.; Costa, R.C. Vegetation, phytoecological regions and landscape diversity in Ceará state, northeastern Brazil. Rodriguésia 2015, 66, 717–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryanto, S.; Wang, L.; Jacinthe, P. Global synthesis of drought effects on maize and wheat production. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevkani, K.; Shivani, B.; Dhaka, S.S.; Patil, C. Cowpeas for sustainable agriculture and nutrition security: An overview of their nutritional quality and agroeconomic advantages. Discov. Food 2025, 1, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, T.S.; Moraes, J.G.L.; Alves, J.M.B.; Jacinto Júnior, S.G.; Oliveira, L.L.B.; Silva, E.M.; Sousa, G.G. Variabilidade Pluviométrica no Ceará e suas Relações com o Cultivo de Milho, Feijão-Caupi e Mandioca (1987–2016). Rev. Bras. Meteorol. 2019, 34, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Companhia Nacional De Abastecimento. Acompanhamento da Safra Brasileira de Grãos, 6th ed.; CONAB: Brasília, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Menezes, H.E.A.; Brito, J.I.B.; Lima, R.A.F.A. Veranico e a produção agrícola no Estado da Paraíba, Brasil. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agríc. Ambient. 2010, 14, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lopes, F.B.; Andrade, E.M.; Aquino, D.N.; Lopes, B.; Frédson, J. Proposta de um índice de sustentabilidade do Perímetro Irrigado Baixo Acaraú, Ceará, Brasil. Rev. Ciênc. Agron. 2009, 40, 185–193. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Lopes, F.B.; Andrade, E.M.; Oliveira, L.J.; Canafístula, F.J.F.; Soares, R.B. Indicadores de sustentabilidade da bacia hidrográfica do riacho Faé, Ceará, a partir de análise multivariada. Rev. Caatinga 2010, 23, 84–92. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Perímetros Públicos Irrigados do Ceará. 2011. Available online: https://www.adece.ce.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/sites/98/2012/10/perimetros_publicos_do_ceara_sb-7.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2022).[Green Version]

- Francisco, P.R.M.; Santos, D.; Lima, E.R.V.; Oliveira, F.P. Aptidão Climática e Pedológica da Cultura do Feijão Caupi para as Regiões do Agreste e Brejo Paraibano. Rev. Bras. Agric. Irrig. 2017, 11, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, Y.; Guan, K.; Schnitkey, G.D.; Lucia, E.; Peng, B. Excessive rainfall leads to maize yield loss of a comparable magnitude to extreme drought in the United States. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 2325–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).