Within My Walls, I Escape Being Underestimated: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Stigma and Help-Seeking in Dementia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To analyze the impact of stigma on the help-seeking attitudes and behaviors of people with dementia.

- To identify the factors that influence the relationship between stigma and help-seeking behavior.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Quality Appraisal

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

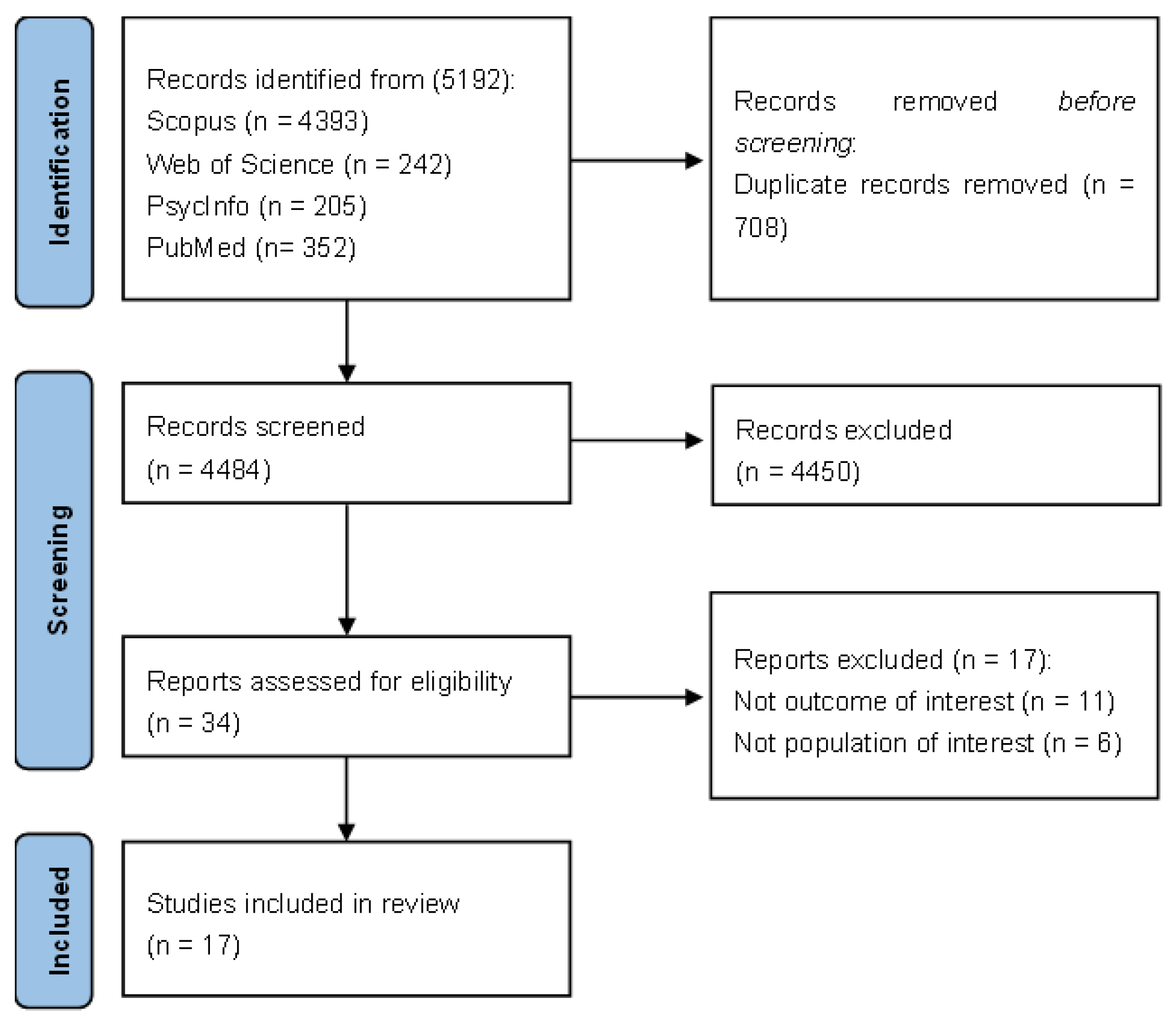

3.1. Study Selection

3.1.1. Risk of Bias in Studies

3.1.2. Study Characteristics

3.2. Thematic Synthesis

3.2.1. Impact of Stigma on Help-Seeking

From Public Perception to Internalization or Rejection of Stigmatizing Beliefs

How Family and Community Shape the Experience of Seeking-Help of People with Dementia

Professional Attitudes and Eligibility Processes in Dementia Services

Stigma Stems from Lack of Awareness and Knowledge of Dementia

3.2.2. Factors That Influence the Relationship Between Stigma and Help-Seeking Attitudes and Behaviors

The Impact of Psychological Decline, Isolation, and Loss of Autonomy on Help-Seeking Behaviors

A Gap in Accessible and Supportive Services

Caregiver Support, Professional Relationships, and Peer Support Along Help-Seeking Path

What Government Can Do to Tackle Dementia and to Promote Help-Seeking

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2011). The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychology & Health, 26(9), 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I., & Kruglanski, A. W. (2019). Reasoned action in the service of goal pursuit. Psychological Review, 126(5), 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. (2024). World alzheimer report 2024: Global changes in attitudes to dementia. Alzheimer’s Disease International. [Google Scholar]

- Bacsu, J.-D., Johnson, S., O’Connell, M. E., Viger, M., Muhajarine, N., Hackett, P., Jeffery, B., Novik, N., & McIntosh, T. (2022). Stigma reduction interventions of dementia: A scoping review. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 41(2), 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer, R. (2008). Stigma and the ethics of public health: Not can we but should we. Social Science & Medicine, 67(3), 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S., Sun, W., Stanyon, W., Nonoyama, M., & Ashtarieh, B. (2022). Exploring the factors that influence equitable access to and social participation in dementia care programs by foreign-born population living in Toronto and Durham region. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 34(9), 2231–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, D., Evans, S., Evans, S., Bray, J., Saibene, F. L., Scorolli, C., Szcześniak, D., d’Arma, A., Urbańska, K. M., Atkinson, T., Farina, E., Rymaszewska, J., Chattat, R., Henderson, C., Rehill, A., Hendriks, I., Meiland, F., & Dröes, R.-M. (2018). Evaluation of the implementation of the meeting centres support program in Italy, Poland, and the UK; exploration of the effects on people with dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(7), 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookman, R., Shatnawi, E., Lukic, K., Sirota, S., & Harris, C. B. (2025). Dementia-related stigma across age groups and perspectives: Similarities and differences suggest the need for tailored anti-stigma interventions. Current Research in Behavioral Sciences, 8, 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgener, S. C., Buckwalter, K., Perkhounkova, Y., & Liu, M. F. (2015a). The effects of perceived stigma on quality of life outcomes in persons with early-stage dementia: Longitudinal findings: Part 2. Dementia, 14(5), 609–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgener, S. C., Buckwalter, K., Perkhounkova, Y., Liu, M. F., Riley, R., Einhorn, C. J., Fitzsimmons, S., & Hahn-Swanson, C. (2015b). Perceived stigma in persons with early-stage dementia: Longitudinal findings: Part 1. Dementia, 14(5), 589–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C., Roche, M., Whitfield, E., Budgett, J., Morgan-Trimmer, S., Zabihi, S., Birks, Y., Walter, F., Wilberforce, M., Jiang, J., Ahmed, R., Dowridge, W., Marshall, C. R., & Cooper, C. (2024). Equality of opportunity for timely dementia diagnosis (EQUATED): A qualitative study of how people from minoritised ethnic groups experience the early symptoms of dementia and seek help. Age and Ageing, 53(11), afae244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, G., Su, A. Y., Wu, K., Yue, B., Yates, S., Martinez Ruiz, A., Krishnamurthi, R., & Cullum, S. (2022). The understanding and experiences of living with dementia in Chinese New Zealanders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, P. W., & Fong, M. W. M. (2014). Competing perspectives on erasing the stigma of illness: What says the dodo bird? Social Science & Medicine, 103, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P. W., Kerr, A., & Knudsen, L. (2005). The stigma of mental illness: Explanatory models and methods for change. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 11(3), 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P. W., & Kleinlein, P. (2005). The impact of mental illness stigma. In On the stigma of mental illness: Practical strategies for research and social change (pp. 11–44). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P. W., & Watson, A. C. (2002). The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 9(1), 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P. W., Watson, A. C., & Barr, L. (2006). The self–Stigma of mental illness: Implications for self–Esteem and self–Efficacy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25(8), 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2018). CASP qualitative checklist. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Dooley, J., Webb, J., James, R., Davis, H., & Read, S. (2025). Exploring experiences of dementia post-diagnosis support and ideas for improving practice: A co-produced study. Dementia (London, England). Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dröes, R.-M., Breebaart, E., Meiland, F. J. M., van Tilburg, W., & Mellenbergh, G. J. (2004). Effect of meeting centres support program on feelings of competence of family carers and delay of institutionalization of people with dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 8(3), 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dröes, R. M., Chattat, R., Diaz, A., Gove, D., Graff, M., Murphy, K., Verbeek, H., Vernooij-Dassen, M., Clare, L., Johannessen, A., Roes, M., Verhey, F., & Charras, K. (2017). Social health and dementia: A European consensus on the operationalization of the concept and directions for research and practice. Aging & Mental Health, 21(1), 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dröes, R. M., Meiland, F. J., Schmitz, M. J., & van Tilburg, W. (2011). How do people with dementia and their carers evaluate the meeting centers support programme? Non-Pharmacological Therapies in Dementia, 2(1), 19. [Google Scholar]

- Dröes, R.-M., Meiland, F. J. M., de Lange, J., Vernooij-Dassen, M. J. F. J., & van Tilburg, W. (2003). The meeting centres support programme: An effective way of supporting people with dementia who live at home and their carers. Dementia, 2(3), 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S., Evans, S., Brooker, D., Henderson, C., Szcześniak, D., Atkinson, T., Bray, J., Amritpal, R., Saibene, F. L., D’arma, A., Scorolli, C., Chattat, R., Farina, E., Urbańska, K., Rymaszewska, J., Meiland, F., & Dröes, R.-M. (2020). The impact of the implementation of the dutch combined meeting centres support programme for family caregivers of people with dementia in Italy, Poland and UK. Aging & Mental Health, 24(2), 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhana, N., Peckham, A., Marani, H., Roerig, M., & Marchildon, G. (2023). The social construction of dementia: Implications for healthcare experiences of caregivers and people living with dementia. Journal of Patient Experience, 10, 23743735231211066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo Da Mata, F. A., Oliveira, D., Mateus, E., Franzon, A. C. A., Godoy, C., Salcher-Konrad, M., De-Poli, C., Comas-Herrera, A., Ferri, C. P., & Lorenz-Dant, K. (2024). Accessing dementia care in Brazil: An analysis of case vignettes. Dementia, 23(3), 378–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajardo, J., Alvarado, R., Slachevsky, A., & Gitlin, L. N. (2022). Self-stigma in people living with dementia in Chile: A qualitative exploratory study. Aging & Mental Health, 26(12), 2481–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, M. H., Azar, D., Goeman, D., Thomas, M., Craig, E. A., & Maybery, D. (2024). Health and social care needs of people living with dementia: A qualitative study of dementia support in the Victorian region of Gippsland, Australia. Rural and Remote Health, 24(1), 8244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hailstone, J., Mukadam, N., Owen, T., Cooper, C., & Livingston, G. (2017). The development of attitudes of people from ethnic minorities to help-seeking for dementia (APEND): A questionnaire to measure attitudes to help-seeking for dementia in people from South Asian backgrounds in the UK. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(3), 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, L., Dobbs, B. M., Stites, S. D., Sajatovic, M., Buckwalter, K., & Burgener, S. C. (2019). Stigma in dementia: It’s time to talk about it. Current Psychiatry, 18(7), 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Phelan, J. C., & Link, B. G. (2013). Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, L. K., Welter, E., Leverenz, J., Lerner, A. J., Udelson, N., Kanetsky, C., & Sajatovic, M. (2018). A systematic review of dementia-related stigma research: Can we move the stigma dial? The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(3), 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, B., Innes, A., & Nyman, S. R. (2021). Experiences of rural life among community-dwelling older men with dementia and their implications for social inclusion. Dementia, 20(2), 444–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. P., & Altman, D. G. (2008). Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (pp. 187–241). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurzuk, S., Farina, N., Pattabiraman, M., Ramasamy, N., Alladi, S., Rajagopalan, J., Comas-Herrera, A., Thomas, P. T., & Evans-Lacko, S. (2022). Understanding, experiences and attitudes of dementia in India: A qualitative study. Dementia-International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 21(7), 2288–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, A., Lavidor, M., Igra, L., & Hasson-Ohayon, I. (2025). Cultural aspects of stigma toward people with serious mental illness: A meta-analysis of the association between individualism-collectivism and social distance. Stigma and Health. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, S., Booth, A., Glenton, C., Munthe-Kaas, H., Rashidian, A., Wainwright, M., Bohren, M. A., Tunçalp, Ö., Colvin, C. J., Garside, R., Carlsen, B., Langlois, E. V., & Noyes, J. (2018). Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualita tive evidence synthesis findings: Introduction to the series. Implementation Science, 13(Suppl. 1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, Y., Xiao, L. D., Zeng, F., Wu, X., Wang, Z., & Ren, H. (2017). The experiences of people with dementia and their caregivers in dementia diagnosis. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 59(4), 1203–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lion, K. M., Szcześniak, D., Bulińska, K., Evans, S. B., Evans, S. C., Saibene, F. L., D’arma, A., Farina, E., Brooker, D. J., Chattat, R., Meiland, F. J. M., Dröes, R., & Rymaszewska, J. (2020). Do people with dementia and mild cognitive impairments experience stigma? A cross-cultural investigation between Italy, Poland and the UK. Aging & Mental Health, 24(6), 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G., Huntley, J., Sommerlad, A., Ames, D., Ballard, C., Banerjee, S., Baryne, C., Burns, A., Cohen-Mansfield, J., Cooper, C., Costafreda, S. G., Dias, A., Fox, N., Gitlin, L. N., Howard, R., Kales, H. C., Kivimäki, M., Larson, E. B., Ogunniyi, A., … Mukadam, N. (2020). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The lancet, 396(10248), 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, L.-F., & Purwaningrum, F. (2020). Negative stereotypes, fear and social distance: A systematic review of depictions of dementia in popular culture in the context of stigma. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, W. W. S., & Cheung, R. Y. M. (2008). Affiliate stigma among caregivers of people with intellectual disability or mental illness. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 21(6), 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F., Turner, A., Wallace, L. M., Choudhry, K., & Bradbury, N. (2013). Perceived barriers to self-management for people with dementia in the early stages. Dementia-International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 12(4), 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, G., McTurk, V., Carter, G., & Brown-Wilson, C. (2020). Emphasise capability, not disability: Exploring public perceptions, facilitators and barriers to living well with dementia in Northern Ireland. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molvik, I., Kjelvik, G., Selbæk, G., & Rokstad, A. M. M. (2024). Exploring the lived experience: Impact of dementia diagnosis on individuals with cognitive impairment—A qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics, 24(1), 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukadam, N., Cooper, C., Kherani, N., & Livingston, G. (2015). A systematic review of interventions to detect dementia or cognitive impairment. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(1), 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukadam, N., & Livingston, G. (2012). Reducing the stigma associated with dementia: Approaches and goals. Aging Health, 8(4), 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T., & Li, X. (2020). Understanding public-stigma and self-stigma in the context of dementia: A systematic review of the global literature. Dementia, 19(2), 148–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D., Sakamoto, M., Seetharaman, K., Chaudhury, H., & Phinney, A. (2022). Conceptualizing citizenship in dementia: A scoping review of the literature. Dementia, 21(7), 2310–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … McKenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M., Barlow, S., Hoe, J., & Aitken, L. (2020). Persistent barriers and facilitators to seeking help for a dementia diagnosis: A systematic review of 30 years of the perspectives of carers and people with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 32(5), 611–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavković, S., Goldberg, L. R., Farrow, M., Alty, J., Abela, M., & Low, L. F. (2025). Post-diagnostic support in Australia: Perspectives of people recently diagnosed with dementia and their carers. Dementia (London, England), 14713012251333880, Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, G., Savundranayagam, M. Y., Kothari, A., & Orange, J. B. (2024). Exploring stigmatizing perceptions of dementia among racialized groups living in the Anglosphere: A scoping review. Aging and Health Research, 4(1), 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, K. A., & Hill, M. R. (2021). The silence of Alzheimer’s disease: Stigma, epistemic injustice, and the inequity of those with progressive cognitive impairment. Communication Research and Practice, 7(4), 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putland, E., & Brookes, G. (2024). Dementia stigma: Representation and language use. Journal of Language and Aging Research, 2(1), 5–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickwood, D., & Thomas, K. (2012). Conceptual measurement framework for help-seeking for mental health problems. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 5, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R. J., Burgener, S., & Buckwalter, K. C. (2014). Anxiety and stigma in dementia: A threat to aging in place. Nursing Clinics, 49(2), 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogler, L. H., & Cortes, D. E. (1993). Help-seeking pathways: A unifying concept in mental health care. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 150(4), 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosin, E. R., Blasco, D., Pilozzi, A. R., Yang, L. H., & Huang, X. (2020). A narrative review of alzheimer’s disease stigma. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 78(2), 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rüsch, N., Hölzer, A., Hermann, C., Schramm, E., Jacob, G. A., Bohus, M., Lieb, K., & Corrigan, P. W. (2006). Self-stigma in women with borderline personality disorder and women with social phobia. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194(10), 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schauman, O., MacLeod, A. K., Thornicroft, G., & Clement, S. (2019). Mental illness related discrimination: The role of self-devaluation and anticipated discrimination for decreased well-being. Stigma and Health, 4(1), 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schomerus, G., & Angermeyer, M. C. (2008). Stigma and its impact on help-seeking for mental disorders: What do we know? Epidemiologia E Psichiatria Sociale, 17(1), 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S., & Walter, F. (2010). Studying help-seeking for symptoms: The challenges of methods and models. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(8), 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, I., Wiegelmann, H., Lenart-Bugla, M., Łuc, M., Pawłowski, M., Rouwette, E., Rymaszewska, J., Szcześniak, D., Vernooij-Dassen, M., Perry, M., Melis, R., Wolf-Ostermann, K., Gerhardus, A., & on behalf of the SHARED consortium. (2022). Mapping the complexity of dementia: Factors influencing cognitive function at the onset of dementia. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siette, J., Meka, A., & Antoniades, J. (2023). Breaking the barriers: Overcoming dementia-related stigma in minority communities. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1278944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strier, R., & Werner, P. (2015). Tracing stigma in long term care insurance in Israel: Stakeholders’ views of policy implementation. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 28, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toms, G. R., Quinn, C., Anderson, D. E., & Clare, L. (2015). Help yourself: Perspectives on self-management from people with dementia and their caregivers. Qualitative Health Research, 25(1), 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A., Flemming, K., McInnes, E., Oliver, S., & Craig, J. (2012). Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernooij-Dassen, M. J. F. J., Moniz-Cook, E. D., Woods, R. T., Lepeleire, J. D., Leuschner, A., Zanetti, O., Rotrou, J. de, Kenny, G., Franco, M., Peters, V., & Iliffe, S. (2005). Factors affecting timely recognition and diagnosis of dementia across Europe: From awareness to stigma. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(4), 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J., Dotchin, C., Breckons, M., Fisher, E., Lyimo, G., Mkenda, S., Walker, R., Urasa, S., Rogathi, J., & Spector, A. (2023). Patient and caregiver experiences of living with dementia in Tanzania. Dementia, 22(8), 1900–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, P. (2014). Stigma and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of evidence, theory, and methods. In The stigma of disease and disability: Understanding causes and overcoming injustices (pp. 223–244). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, P., Gur, A., Porat, A., Zubedat, M., & Shinan-Altman, S. (2020). Medical students’ help-seeking recommendations for a person with Alzheimer’s disease: Relationships with knowledge and stigmatic beliefs. Educational Gerontology, 46(5), 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, P., Ulitsa, N., Alpinar-Sencan, Z., Shefet, D., & Schicktanz, S. (2024). Identifying stigmatizing language used by Israelis and Germans with a Mild Neurocognitive Disorder, their relatives, and caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 38(1), 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, R., Zaidi, A., Balouch, S., & Farina, N. (2020). Experiences of people with dementia in Pakistan: Help-seeking, understanding, stigma, and religion. The Gerontologist, 60(1), 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.-A., & Anstey, K. J. (2024). Dementia prevention and individual and socioeconomic barriers: Avoiding “lifestyle” stigma. The Gerontologist, 64(5), gnad130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2021). Global status report on the public health response to dementia. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J. A., Lind, C., Orange, J. B., & Savundranayagam, M. Y. (2019). Expanding current understandings of epistemic injustice and dementia: Learning from stigma theory. Journal of Aging Studies, 48, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Clarke, C. L., & Rhynas, S. J. (2020). Tensions in dementia care in China: An interpretative phenomenological study from Shandong province. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 15(1), e12291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search terms corresponding to ‘exposure’ included ‘stigma’, ‘stigmatization’, ‘self-stigma’, ‘internalized stigma’, ‘subjective stigma’, ‘public-stigma’, ‘social stigma’, and ‘societal stigma’, as well as terms related to help-seeking attitudes and behaviors, respectively, ‘help-seeking’, ‘treatment-seeking’, ‘care-seeking’, ‘healthcare utilization’, ‘seeking assistance’, ‘seeking support’, ‘seeking help’, ‘utilization of services’, and ‘barrier’. The basic search string based on Boolean operators was applied into each database as follow: [Dementia OR “Alzheimer’s disease” OR “Neurocognitive disorder” OR “Neurodegenerative disease”] AND [Stigma OR Stigmatization OR Self-stigma OR “Internalized stigma” OR “Subjective stigma” OR Public-stigma OR “Social stigma” OR “Societal stigma”] AND [Help-seeking OR Treatment-seeking OR Care-seeking OR “Healthcare utilization” OR “Seeking assistance” OR “Seeking support” OR “Seeking help” OR “Utilization of services” OR Barrier*]. |

| Section A: Are the Results Valid? | Section B: What Are the Results? | Section C: Will the Results Help Locally? | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | 2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | 3. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | 4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | 5. Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | 6. Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | 7. Have the ethical issues been taken into consideration? | 8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | 9. Is there a clear statement of findings? | 10. How valuable is the research? | |

| (Biswas et al., 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (Carter et al., 2024) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes |

| (Cheung et al., 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (Dooley et al., 2025) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (Farhana et al., 2023) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (Garrett et al., 2024) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (Hurzuk et al., 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (Lian et al., 2017) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (Martin et al., 2013) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (Mitchell et al., 2020) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (Molvik et al., 2024) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (Pavković et al., 2025) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (Strier and Werner, 2015) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Cannot tell | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (Toms et al., 2015) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (Walker et al., 2023) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (Willis et al., 2020) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (Zhang et al., 2020) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Authors (Year) and Country | Aim | Study Design and Methodology | Sample | Key Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biswas et al. (2022) Canada | To address the factors that influence equitable access to and social participation in dementia care and support programs among foreign-born individuals including recent and non-recent immigrants and refugees | Qualitative—Interviews | Seven participants: two people with dementia, three caregivers, and two healthcare professionals |

|

| Carter et al. (2024) United Kingdom | To explore how experiences of immigration and effects of globalization on family life and traditional kinships might explain delayed diagnosis and engagement with and by health services | Qualitative—Semi-structured interviews | A total of 61 participants: 10 people with dementia; 30 family members; 16 healthcare professionals; 2 interpreters; and 3 paid carers |

|

| Cheung et al. (2022) New Zealand | To explore their understanding of dementia and experiences of living with dementia | Qualitative—Semi-structured interviews | A total of 16 participants: 5 dyads of people with dementia and a family member, 6 people with dementia, and 5 family members of people with dementia |

|

| Dooley et al. (2025) United Kingdom | (1) To find out about the experiences of current post-diagnosis support from people living with dementia (2) To explore ideas and suggestions of people living with dementia to improve post-diagnosis support | Qualitative—Focus groups | A total of 28 participants: 18 people with dementia and 10 spouses who were there to provide support |

|

| Farhana et al. (2023) United States | To discuss how the social construction of dementia shapes the health and social care interactions and experiences of people living with an AD/ADRD and their caregivers | Qualitative—Interviews | A total of 11 participants: 3 people with dementia and 8 caregivers |

|

| Garrett et al. (2024) Australia | To increase the knowledge of the needs of people living with dementia and those who provide informal or formal support to someone living with dementia in the Gippsland region | Qualitative—Interviews | A total of 26 participants: 25 people with dementia and 1 dyad |

|

| Hurzuk et al. (2022) India | To understand attitudes and perceptions concerning people living with dementia residing in India from two diverse metropolitan cities, Delhi and Chennai | Qualitative—focus group discussions and individual interviews | A total of 58 participants: 15 from the public, 16 healthcare practitioners, 19 dementia carers, and 8 people with dementia |

|

| Lian et al. (2017) China | To understand the experiences of people with dementia and their caregivers in engaging in dementia diagnosis | Qualitative—focus group discussions and individual interviews | A total of 18 people with dementia |

|

| Martin et al. (2013) United Kingdom | To explore barriers to self-management among people living with dementia | Qualitative—Interviews | A total of 11 participants: 7 people with dementia, 2 family members, and 2 charity representatives |

|

| Mitchell et al. (2020) Northern Ireland | To explore current public perceptions of living well with dementia from the perspective of people with dementia | Qualitative—Focus group | A total of 20 people with dementia |

|

| Molvik et al. (2024) Norway | To explore the experience of living with cognitive impairment compatible with a possible dementia and the impact of being diagnosed with dementia | Qualitative—Semi-structured interviews | A total of 15 participants: 6 people with dementia, and 9 with cognitive impairment compatible with possible dementia (not diagnosed with dementia) |

|

| Pavković et al. (2025) Australia | What support was offered to people with dementia and their carers in Australian memory clinics in the year following the diagnosis? 2) What do people with dementia and carers think are the barriers and facilitators to accessing and utilizing post-diagnostic services? 3) What do people with dementia and carers think should be the ideal post-diagnostic support offered by memory clinics in the first year following diagnosis? | Qualitative—Semi-structured interviews | A total of 30 participants: 10 people with dementia; 13 caregivers of people with dementia; 3 people with young-onset dementia; and 4 caregivers of people with young-onset dementia |

|

| Strier and Werner (2015) Israel | To investigate the existence of identity and treatment stigma and if so, how stigmatic views influence on the presence of welfare stigma | Qualitative—Interviews and focus groups | A total of 50 participants: 10 people with dementia, 25 relatives, and 15 professionals |

|

| Toms et al. (2015) North Wales, United Kingdom | (1) To explore the attitudes toward self-management held by people with early-stage dementia and their family caregivers; (2) to examine their views and perceptions of self-management and explored factors that could make self-management difficult | Qualitative—Semi-structured interviews | A total of 24 participants: 13 people with dementia, and 11 caregivers |

|

| Walker et al. (2023) Tanzania | To understand people with dementia and their caregivers’ experiences, identify challenges of living with dementia in Tanzania, and explore perceived support needs | Qualitative—Semi-structured interviews | A total of 26 participants: 14 people with dementia (2 of them were interviewed with their caregivers to support communication), and 12 caregivers |

|

| Willis et al. (2020) Pakistan | To explore respondents’ experiences with help-seeking, understandings of dementia, experiences with stigma, and the role of religion | Qualitative—Semi-structured interviews | A total of 20 people with dementia |

|

| Zhang et al. (2020) China | To understand what challenges and tensions people with dementia and their family caregivers are facing in the context of dementia care services | Qualitative—Interviews | A total of 24 participants: 14 caregivers, and 10 people with dementia (2 participants were a care dyad) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brigiano, M.; Calabrese, L.; Chirico, I.; Trolese, S.; Quartarone, M.; Forte, L.; Annini, A.; Murri, M.B.; Chattat, R. Within My Walls, I Escape Being Underestimated: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Stigma and Help-Seeking in Dementia. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 774. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060774

Brigiano M, Calabrese L, Chirico I, Trolese S, Quartarone M, Forte L, Annini A, Murri MB, Chattat R. Within My Walls, I Escape Being Underestimated: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Stigma and Help-Seeking in Dementia. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):774. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060774

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrigiano, Marco, Lara Calabrese, Ilaria Chirico, Sara Trolese, Martina Quartarone, Ludovica Forte, Alice Annini, Martino Belvederi Murri, and Rabih Chattat. 2025. "Within My Walls, I Escape Being Underestimated: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Stigma and Help-Seeking in Dementia" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 774. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060774

APA StyleBrigiano, M., Calabrese, L., Chirico, I., Trolese, S., Quartarone, M., Forte, L., Annini, A., Murri, M. B., & Chattat, R. (2025). Within My Walls, I Escape Being Underestimated: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Stigma and Help-Seeking in Dementia. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 774. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060774