Cogito, Ergo Contraho: Think Big or Think Small? How Construal Level Theory Shapes Creative Agreements

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis

2.1. Creative Agreements

2.2. Low Construal Level for Creative Agreements

2.3. Mixed Construal Levels and Creative Agreements

3. Experiments: Methodology, Materials, and Results

- Overview of the Current Experiments

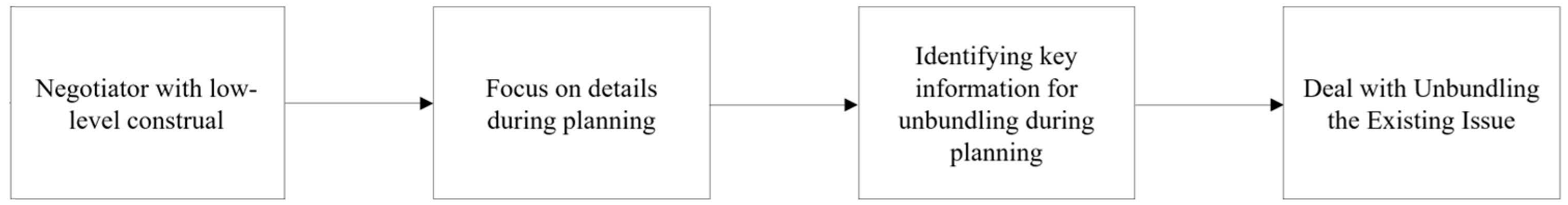

3.1. Experiment 1: Construal Level as an Influence on Unbundling

3.1.1. Method

3.1.2. Results

3.1.3. Additional Analysis

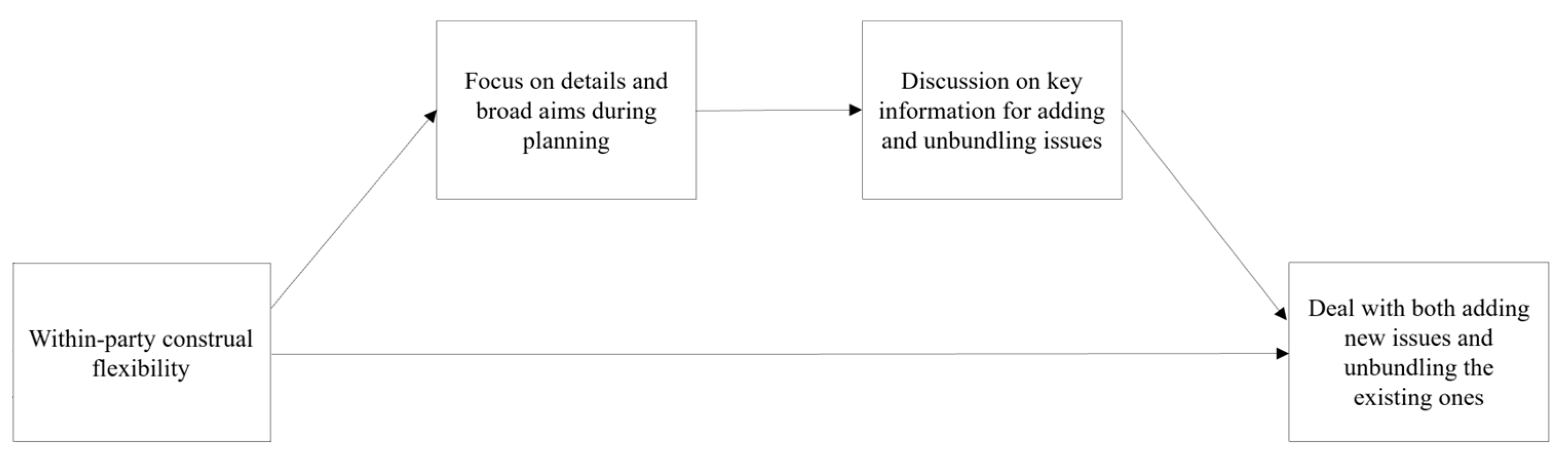

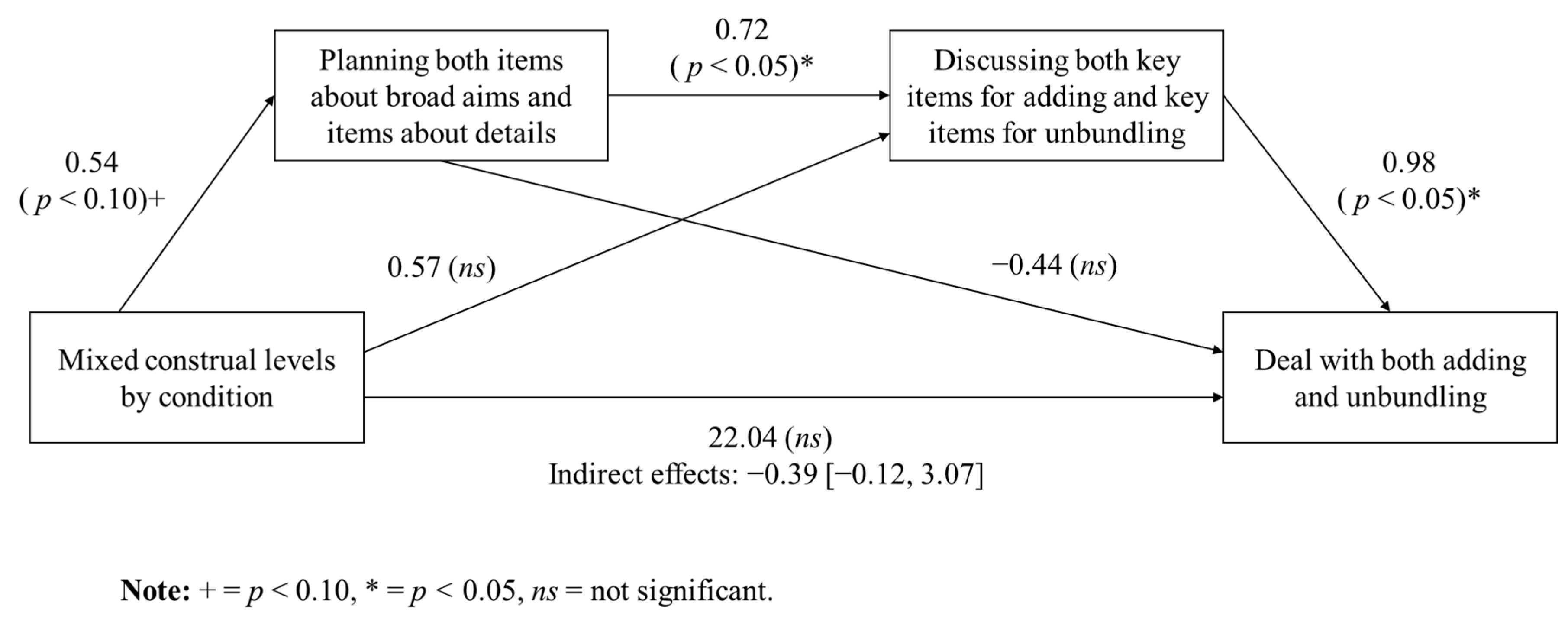

3.2. Experiment 2: Within-Party Construal Flexibility

3.2.1. Method

3.2.2. Results

3.3. Summary and Interpretation of Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Implications for Management and Practice

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alter, A. L., Oppenheimer, D. M., & Zemla, J. C. (2010). Missing the trees for the forest: A construal level account of the illusion of explanatory depth. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(3), 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C., & Thompson, L. L. (2004). Affect from the top down: How powerful individuals’ positive affect shapes negotiations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 95(2), 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Anan, Y., Liberman, N., & Trope, Y. (2006). The association between psychological distance and construal level: Evidence from an implicit association test. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 135(4), 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, B., & Friedman, R. A. (1998). Bargainer characteristics in distributive and integrative negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(2), 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazerman, M. H., Magliozzi, T., & Neale, M. A. (1985). Integrative bargaining in a competitive market. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 35(3), 294–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benetti, S., Ogliastri, E., & Caputo, A. (2021). Distributive/integrative negotiation strategies in cross-cultural contexts: A comparative study of the USA and Italy. Journal of Management & Organization, 27(4), 786–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berson, Y., Oreg, S., & Wiesenfeld, B. (2021). A construal level analysis of organizational change processes. Research in Organizational Behavior, 41, 100148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, B., & Sharma, D. (2024). Negotiation skills: How to stay stronger in negotiation. In Managing and negotiating disagreements: A contemporary approach for conflict resolution (pp. 141–151). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. In M. A. Gernsbacher, & J. R. Pomerantz (Eds.), Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society (2nd ed., pp. 56–64). Worth. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. K. (1994). Conflict styles and outcomes in a negotiation with fully-integrative potential. International Journal of Conflict Management, 5(4), 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J. K. (1999). Trust expectations, information sharing, climate of trust, and negotiation effectiveness and efficiency. Group & Organization Management, 24(2), 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Unsworth, K. L., & Zhang, L. (2023). Reciprocal exchange orientation to organization, challenge stressor and construal level: Three-way interaction effects on voice behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1119596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curhan, J. R., Elfenbein, H. A., & Xu, H. (2006). What do people value when they negotiate? Mapping the domain of subjective value in negotiation. Journal of personality and social psychology, 91(3), 493–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curhan, J. R., Labuzova, T., & Mehta, A. (2021). Cooperative criticism: When criticism enhances creativity in brainstorming and negotiation. Organization Science, 32(5), 1256–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C. K., & Carnevale, P. (2005). Laboratory experiments on negotiation and social conflict. International Negotiation, 10(1), 51–66. Available online: https://brill.com/view/journals/iner/10/1/article-p51_5.xml?ebody=abstract%2Fexcerpt (accessed on 2 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C. K., Nijstad, B. A., & van Knippenberg, D. (2008). Motivated information processing in group judgment and decision making. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12(1), 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, G., & Stadtler, H. (2005). Negotiation-based collaborative planning between supply chains partners. European Journal of Operational Research, 163(3), 668–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R. (1964). Fractionating conflict. Daedalus, 93(3), 920–941. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20026866 (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Fisher, R., Ury, W. L., & Patton, B. (2011). Getting to yes: Negotiating agreement without giving in. Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Fisk, S. T., Lin, M., & Neuberg, S. L. (1999). The continuum model: Ten years later. In S. Chaiken, & Y. Trope (Eds.), Dual-process theories in social psychology (pp. 231–254). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Flesch, R. (1950). Measuring the level of abstraction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 34, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follett, M. P. (1940). Constructive conflict. In H. C. Metcalf, & L. Urwick (Eds.), Dynamic administration: The collected papers of Mary Parker Follett. Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Fousiani, K., De Jonge, K. M. M., & Michelakis, G. (2022). Having no negotiation power does not matter as long as you can think creatively: The moderating role of age. International Journal of Conflict Management, 33(5), 956–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, J., Friedman, R. S., & Liberman, N. (2004). Temporal construal effects on abstract and concrete thinking: Consequences for insight and creative cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froman, L. A., & Cohen, M. D. (1970). Compromise and logroll: Comparing the efficiency of two bargaining processes. Behavioral Science, 15(2), 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galinsky, A. D., Leonardelli, G. J., Okhuysen, G. A., & Mussweiler, T. (2005). Regulatory focus at the bargaining table: Promoting distributive and integrative success. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(8), 1087–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galinsky, A. D., Maddux, W. W., Gilin, D., & White, J. B. (2008). Why it pays to get inside the head of your opponent the differential effects of perspective taking and empathy in negotiations. Psychological Science, 19(4), 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelfand, M. J., & Brett, J. M. (2004). The handbook of negotiation and culture. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand, M. J., Severance, L., Lee, T., Bruss, C. B., Lun, J., Abdel-Latif, A. H., Al-Moghazy, A. A., & Moustafa Ahmed, S. (2015). Culture and getting to yes: The linguistic signature of creative agreements in the United States and Egypt. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(7), 967–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomantonio, M., De Dreu, C. K., & Mannetti, L. (2010a). Now you see it, now you don’t: Interests, issues, and psychological distance in integrative negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(5), 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacomantonio, M., De Dreu, C. K., Shalvi, S., Sligte, D., & Leder, S. (2010b). Psychological distance boosts value-behavior correspondence in ultimatum bargaining and integrative negotiation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(5), 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J. K., & Malkoc, S. A. (2012). Choosing here and now versus there and later: The moderating role of psychological distance on assortment size preferences. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(4), 751–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, I., Gerlach, T. M., & Denissen, J. J. (2016). Wise reasoning in the face of everyday life challenges. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(7), 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediationmoderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, M. D., & Trope, Y. (2009). The effects of abstraction on integrative agreements: When seeing the forest helps avoid getting tangled in the trees. Social Cognition, 27(3), 402–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D., Choi, H., & Loewenstein, J. (2021). Integration through redefinition: Revisiting the role of negotiators’ goals. Group Decision and Negotiation, 30(5), 1113–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. FT press. [Google Scholar]

- Kray, L. J., Galinsky, A. D., & Markman, K. D. (2009). Counterfactual structure and learning from experience in negotiations. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 979–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lax, D. A., & Sebenius, J. K. (1986). The manager as negotiator: Bargaining for competitive gain. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lax, D. A., & Sebenius, J. K. (2006). 3-D Negotiation: Powerful tools to change the game in your most important deals. Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicki, R. J., Barry, B., & Saunders, D. M. (2011). Essentials of negotiation. McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman, N., & Trope, Y. (1998). The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, G., & Moore, D. A. (2004). When ignorance is bliss: Information exchange and inefficiency in bargaining. The Journal of Legal Studies, 33(1), 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, J., & Howell, T. (2010, February 8). Understanding and using what we want: Interests and exploitation in negotiations. IACM 23rd International Association for Conflict Management, Boston, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Luan, J., Filieri, R., Xiao, J., & Sun, Y. (2023). Consumer–brand relationships and social distance: A construal level theory perspective. Psychology & Marketing, 40(7), 1299–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddux, W. W., Adam, H., & Galinsky, A. D. (2010). When in Rome … Learn why the Romans do what they do: How multicultural learning experiences facilitate creativity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(6), 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddux, W. W., & Galinsky, A. D. (2009). Cultural borders and mental barriers: The relationship between living abroad and creativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 1047–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddux, W. W., Mullen, E., & Galinsky, A. D. (2008). Chameleons bake bigger pies and take bigger pieces: Strategic behavioral mimicry facilitates negotiation outcomes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(2), 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M. (2025). How, when, and why do Negotiators Use Reference Points? A Qualitative Interview Study with Negotiation Practitioners. In Navigating through the fog of negotiation (pp. 35–80). Springer Gabler. [Google Scholar]

- Miron-Spektor, E., Gino, F., & Argote, L. (2011). Paradoxical frames and creative sparks: Enhancing individual creativity through conflict and integration. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 116(2), 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J. S., Wakslak, C. J., & Krishnan, V. (2014). Construing creativity: The how and why of recognizing creative ideas. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 51, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C. H., Baer, M., & Nickerson, J. (2025). Looking at the trees to see the forest: Construal level shift in strategic problem framing and formulation. Organization Science, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, B. E., Deval, H., Kardes, F. R., Ewing, D. R., Han, X., & Cronley, M. L. (2014). Effects of construal level on omission detection and multiattribute evaluation. Psychology & Marketing, 31(11), 992–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruitt, D. G. (1981). Negotiation behavior. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt, D. G. (1983). Integrative agreements: Nature and antecedents. In M. H. Bazerman, & R. J. Lewicki (Eds.), Negotiation in organizations. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt, D. G., & Carnevale, P. J. (1993). Negotiation in social conflict. Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt, D. G., & Lewis, S. A. (1975). Development of integrative solutions in bilateral negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31(4), 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, L. L., & Holmer, M. (1992). Framing, reframing, and issue development. In L. L. Putnam, & M. E. Roloff (Eds.), Communication and negotiation (pp. 128–155). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, D. M. (2001). Schema, promise and mutuality: The building blocks of the psychological contract. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 74(4), 511–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shani, Y., Igou, E. R., & Zeelenberg, M. (2009). Different ways of looking at unpleasant truths: How construal levels influence information search. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 110(1), 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simosi, M., Rousseau, D. M., & Weingart, L. R. (2021). Opening the black box of i-deals negotiation: Integrating i-deals and negotiation research. Group & Organization Management, 46(2), 186–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinaceur, M., Maddux, W. W., Vasiljevic, D., Nückel, R. P., & Galinsky, A. D. (2013). Good things come to those who wait late first offers facilitate creative agreements in negotiation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(6), 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbach, A. L., Gamache, D. L., & Johnson, R. E. (2019). Don’t get it misconstrued: Executive construal-level shifts and flexibility in the upper echelons. Academy of Management Review, 44(4), 871–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L. L. (1991). Information exchange in negotiation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 27(2), 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L. L. (1998). The mind and heart of the negotiation. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, L. L., & Hastie, R. (1990). Social perception in negotiation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 47(1), 98–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117(2), 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, R. E., & McKersie, R. B. (1965). A behavioral theory of labor negotiations: An analysis of a social interaction system. Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weingart, L. R., Brett, J. M., Olekalns, M., & Smith, P. L. (2007). Conflicting social motives in negotiating groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(6), 994–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wening, S., Keith, N., & Abele, A. E. (2015). High construal level can help negotiators to reach integrative agreements: The role of information exchange and judgement accuracy. British Journal of Social Psychology, 55(2), 206–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesenfeld, B. M., Reyt, J. N., Brockner, J., & Trope, Y. (2017). Construal level theory in organizational research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4(1), 367–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wronowska, G. (2023). Determination of the importance of job offer characteristics by students of economic studies: Factor analysis. Ekonomia i Prawo. Economics and Law, 22(4), 861–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J., Zhang, Z. X., & Liu, L. A. (2020). When there is NO ZOPA: Mental fatigue, integrative complexity, and creative agreement in negotiations. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Wang, X., Zhang, A., Zhou, J., Xu, X., & Pang, W. (2025). Greater psychological distance, better creative-idea selection: The mediating role of construal level. BMC Psychology, 13, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhbanova, K. S., & Rule, A. C. (2014). Construal level theory applied to sixth graders’ creativity in craft constructions with integrated proximal or distal academic content. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 13, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, H. Cogito, Ergo Contraho: Think Big or Think Small? How Construal Level Theory Shapes Creative Agreements. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060775

Choi H. Cogito, Ergo Contraho: Think Big or Think Small? How Construal Level Theory Shapes Creative Agreements. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):775. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060775

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Hyeran. 2025. "Cogito, Ergo Contraho: Think Big or Think Small? How Construal Level Theory Shapes Creative Agreements" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060775

APA StyleChoi, H. (2025). Cogito, Ergo Contraho: Think Big or Think Small? How Construal Level Theory Shapes Creative Agreements. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060775