From Policy Reform to Public Reckoning: Exploring Shifts in the Reporting of Sexual-Violence-Against-Women Victimizations in the United States Between 1992 and 2021

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Historical Context of Sexual VAW Reporting (Pre-1992)

1.2. Barriers to Reporting Sexual VAW

1.3. Trends in Reporting Patterns (1992–2021)

1.4. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. National Crime Victimization Survey

2.2. Variables

2.2.1. Sexual Victimization

2.2.2. Reporting

2.2.3. Year

2.3. Analytical Plan

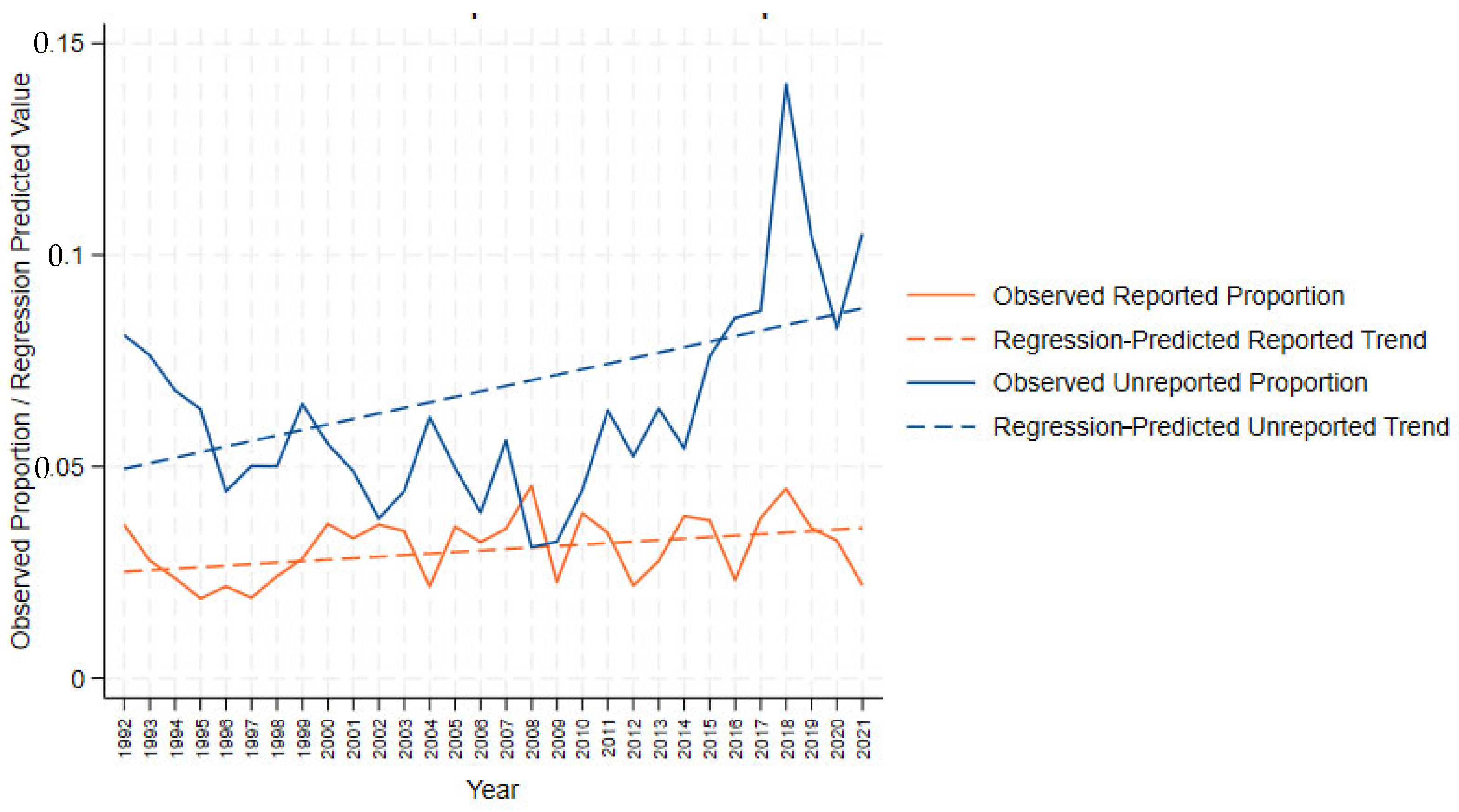

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Research Directions

4.2. Policy Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Smith et al. (2018) defines contact sexual violence as including rape, being made to penetrate someone else, sexual coercion resulting in physical contact, and/or unwanted sexual contact (p. 17). |

| 2 | The “prompt complaint rule” required victims to report sexual violence immediately to maintain credibility in court, ignoring factors like trauma and stigma that delay reporting (Anderson, 2004; Tuerkheimer, 2017). |

| 3 | “Rape shield laws” were established to protect victims from having their past sexual conduct scrutinized. |

| 4 | Responsible media reporting of VAW has been defined as providing accurate, sensitive, and ethical journalism that avoids sensationalism, victim-blaming, and perpetrator justification (Impe, 2019; Sutherland et al., 2016). Further, responsible media reporting includes protecting survivor safety and confidentiality; challenging harmful myths; using thoughtful language, imagery, and social context; and providing information on available support resources—all with the aim of promoting understanding, preventing harm, and addressing VAW as a serious social issue (Impe, 2019; Sutherland et al., 2016). |

| 5 | Levy and Mattsson (2019) employed a difference-in-differences specification analysis, utilizing UCR and NIBRIS datasets to quantify the #MeToo movement’s effect on the reporting rates of sexual violence to law enforcement agencies in the United States. Their approach allowed for a robust empirical examination of the period before and after the movement’s gain in popularity, revealing a notable uptick in reports following the #MeToo movement. |

| 6 | Rotenberg and Cotter (2018) observed a marked increase in formal reports of sexual assaults to Canadian police forces in October 2017, coinciding with the #MeToo movement’s viral spread. This period saw an unprecedented spike in the number of reports in October and November, the highest since the commencement of comparable data collection in 2009. |

| 7 | The 2006 and 2016 redesigns were completed in response to U.S. Census Bureau population data and the sample adjusted to account for demographic changes. Additionally, the shift from paper-and-pencil data collection to computer-assisted interviewing impacted 2006 reporting trends, but these were stablized by 2007. |

| 8 | See pages 6–7 of the 2016 Technical Documentation for more detail on NCVS crime classification. The criteria for this classification were drawn from the values in NCVS variable V4529 in which violent crimes are defined as those involving physical attacks, attempted attacks, and threats of harm with direct contact between the victim and offender, while property crimes do not involve direct contact. Sexual crimes, including rape and sexual assault, are categorized based on the type of attack, injury, or threat, while non-sexual victimizations such as robbery and assault do not include these specific sexual elements (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2017). |

| 9 | This crime type was added midway through the 1992 collection data collection and, as such, is not available for two quarters of the data, or 1.67% of the dataset’s time frame. |

| 10 | From 1992 to 2021, additional items measuring this variable were added to the NCVS, but the item used here allowed for the most consistent analysis of the data over the time period of interest. |

References

- AbiNader, M. A., Thomas, M. M. C., & Carolan, K. (2024). ‘This happened once before’: Sexual violence and US Supreme Court nominees. Journal of Gender-Based Violence, 8(1), 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addington, L. A., & Rennison, C. M. (2008). Rape co-occurrence: Do additional crimes affect victim reporting and police clearance of rape? Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 24(2), 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ake, J., & Arnold, G. (2016). A brief history of anti-violence-against-women movements in the US. In Sourcebook on violence against women (2nd ed., pp. 3–26). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M. J. (2004). The legacy of the prompt complaint requirement, corroboration requirement, and cautionary instructions on campus sexual assault. Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law, 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, P. (1955). Tests for linear trends in proportions and frequencies. Biometrics, 11(3), 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroustamian, C. (2020). Time’s up: Recognizing sexual violence as a public policy issue: A qualitative content analysis of sexual violence cases and the media. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 50, 101341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascherio, M. (2023). An intersectional analysis of system avoidance. Gender & Society, 37(3), 361–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiama, A. A., & Zhong, H. (2022). Victims rational decision: A theoretical and empirical explanation of dark figures in crime statistics. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), 2029249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachman, R. (1993). Predicting the reporting of rape victimizations: Have rape reforms made a difference? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 20(3), 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachman, R. (1998). The factors related to rape reporting behavior and arrest: New evidence from the national crime victimization survey. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 25(1), 8–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A., & Rodrigues, U. M. (2022). Reporting on sexual violence during the #MeToo 2.0 hashtag era: Can the media be an agent of social change? In Reporting on sexual violence in the #MeToo era. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Baumer, E. P. (2004). Temporal variation in the likelihood of police notification by victims of rapes, 1973–2000. U.S. National Institute of Justice. [CrossRef]

- Baumer, E. P., & Lauritsen, J. L. (2010). Reporting crime to the police, 1973–2005: A multivariate analysis of long-term trends in the national crime survey (ncs) and national crime victimization survey (ncvs). Criminology, 48(1), 131–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC. (2018, September 23). #WhyIDidntReport: The hashtag supporting Christine Blasey Ford. BBC. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-45621124 (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Bevacqua, M. (2000). Rape on the public agenda: Feminism and the politics of sexual assault. Northeastern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua, K. G., Arciniegas, S., Page, K., Steinberg, A. K., Stellmann, J., Flores-Miller, A., & Wirtz, A. L. (2022). Contexts of violence victimization and service-seeking among Latino/a/x immigrant adults in Maryland and the District of Columbia: A qualitative study. Journal of Migration and Health, 7, 100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boba, R., & Lilley, D. (2009). Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) funding: A nationwide assessment of effects on rape and assault. Violence Against Women, 15(2), 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogen, K. W., Bleiweiss, K. K., Leach, N. R., & Orchowski, L. M. (2021). #MeToo: Disclosure and response to sexual victimization on twitter. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(17–18), 8257–8288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M., Ray, R., Summers, E., & Fraistat, N. (2017). #SayHerName: A case study of intersectional social media activism. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(11), 1831–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownmiller, S. (1977). Against our will: Men, women and rape. Repr. [d. Ausg.] 1976. Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bryden, D. P., & Lengnick, S. (1997). Rape in the criminal justice system. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 87(4), 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubala, M. (2014, September 29). “No More” PSA campaigns to stop silence on domestic violence. CBS News. Available online: https://www.cbsnews.com/baltimore/news/no-more-psa-campaigns-to-stop-silence-on-domestic-violence/ (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2017). National crime victimization survey, [United States], 2016: Version 4, codebook (Version v4). ICPSR—Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research. [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2022). National crime victimization survey, concatenated file, [United States], 1992–2021: Codebook. ICPSR—Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R., Wasco, S. M., Ahrens, C. E., Sefl, T., & Barnes, H. E. (2001). Preventing the “second rape”: Rape survivors’ experiences with community service providers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 16(12), 1239–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carll, E. K. (2005). Violence and women: News coverage of victims and perpetrators. In E. Cole, & J. H. Daniel (Eds.), Featuring females: Feminist analyses of media (pp. 143–153). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, J. J., Jenkins, S., Ortbals, C. D., Poloni-Staudinger, L., & Strachan, J. C. (2020). The effect of the #MeToo movement on political engagement and ambition in 2018. Political Research Quarterly, 73(4), 926–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceelen, M., Dorn, T., Van Huis, F. S., & Reijnders, U. J. L. (2019). Characteristics and post-decision attitudes of non-reporting sexual violence victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(9), 1961–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay-Warner, J., & Burt, C. H. (2005). Rape reporting after reforms: Have times really changed? Violence Against Women, 11(2), 150–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, W. S. (1979). Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(368), 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W. G. (1954). Some methods for strengthening the common χ2 tests. Biometrics, 10(4), 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). (1992). CEDAW general recommendations nos. 19 and 20, adopted at the eleventh session, 1992 (contained in Document A/47/38), A/47/38, 1992. UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/legal/general/cedaw/1992/en/14045 (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Davis v. Washington, 547 U.S. 813. (2006).

- Decker, M. R., Holliday, C. N., Hameeduddin, Z., Shah, R., Miller, J., Dantzler, J., & Goodmark, L. (2019). “You do not think of me as a human being”: Race and gender inequities intersect to discourage police reporting of violence against women. Journal of Urban Health, 96(5), 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denim Day. (2019, April 19). TAKE ACTION: Violence against women act reauthorization. Available online: https://denimday.org/blog/take-action-vawa-2019 (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- DePrince, A. P., Wright, N., Gagnon, K. L., Srinivas, T., & Labus, J. (2020). Social reactions and women’s decisions to report sexual assault to law enforcement. Violence Against Women, 26(5), 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, J. J., & Levitt, S. D. (2001). The impact of legalized abortion on crime. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(2), 379–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunford, F. W., Huizinga, D., & Elliott, D. S. (1990). The role of arrest in domestic assault: The Omaha police experiment. Criminology, 28(2), 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easteal, P., Holland, K., & Judd, K. (2015). Enduring themes and silences in media portrayals of violence against women. Women’s Studies International Forum, 48, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckroth, S. (2023). Historical perspective on the national crime victimization survey…50 years of data and counting. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/blogs/historical-perspective-national-crime-victimization-survey50-years-data-and-counting (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Egen, O., Mercer Kollar, L. M., Dills, J., Basile, K. C., Besrat, B., Palumbo, L., & Carlyle, K. E. (2020). Sexual violence in the media: An exploration of traditional print media reporting in the United States, 2014–2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(47), 1757–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbairn, J. (2020). Before #MeToo: Violence against women social media work, bystander intervention, and social change. Societies, 10(3), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fansher, A., Self, M., & Zedaker, S. (2023). Sexual assault reporting trends during COVID-19 lockdown: Results from a metropolitan city. Violence and Gender, 10(3), 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, G., Tilley, N., & Tseloni, A. (2014). Why the crime drop? Crime and Justice, 43(1), 421–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felson, R. B., & Feld, S. L. (2009). When a man hits a woman: Moral evaluations and reporting violence to the police. Aggressive Behavior, 35(6), 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felson, R. B., & Paré, P. (2005). The reporting of domestic violence and sexual assault by nonstrangers to the police. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(3), 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fileborn, B., & Loney-Howes, R. (Eds.). (2019). #MeToo and the politics of social change. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, B. S., Daigle, L. E., Cullen, F. T., & Turner, M. G. (2003). Reporting sexual victimization to the police and others: Results from a national-level study of college women. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 30(1), 6–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, J. (2018, September 23). #WhyIDidntReport: Survivors of sexual assault share their stories after Trump tweet. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/23/us/why-i-didnt-report-assault-stories.html (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Frye, V., Haviland, M., & Rajah, V. (2007). Dual arrest and other unintended consequences of mandatory arrest in New York city: A brief report. Journal of Family Violence, 22(6), 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezinski, L. B. (2022). “It’s kind of hit and miss with them”: A qualitative investigation of police response to intimate partner violence in a mandatory arrest state. Journal of Family Violence, 37(1), 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodmark, L. (2022). Assessing the impact of the violence against women act. Annual Review of Criminology, 5(1), 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gover, A. R., & Moore, A. M. (2021). The 1994 violence against women act: A historic response to gender violence. Violence Against Women, 27(1), 8–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gover, A. R., Welton-Mitchell, C., Belknap, J., & Deprince, A. P. (2013). When abuse happens again: Women’s reasons for not reporting new incidents of intimate partner abuse to law enforcement. Women & Criminal Justice, 23(2), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidry, J. P. D., Sawyer, A. N., Carlyle, K. E., & Burton, C. W. (2021). #WhyIDidntReport: Women speak out about sexual assault on twitter. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 17(3), 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, C. M., & Kirk, D. S. (2017). Silence speaks: The relationship between immigration and the underreporting of crime. Crime & Delinquency, 63(8), 926–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewa, N. (2022). The mouth of the internet, the eyes of the public: Sexual violence survivorship in an economy of visibility. Feminist Media Studies, 22(8), 1990–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, C. N., Kahn, G., Thorpe, R. J., Shah, R., Hameeduddin, Z., & Decker, M. R. (2020). Racial/ethnic disparities in police reporting for partner violence in the national crime victimization survey and survivor-led interpretation. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 7(3), 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, S. J., Zhang, Y., Hayes, B. E., & Bills, M. A. (2020). Mandatory arrest for domestic violence and repeat offending: A meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 53, 101430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htun, M., & Jensenius, F. R. (2020). Fighting violence against women: Laws, norms & challenges ahead. Daedalus, 149(1), 144–159. [Google Scholar]

- Impe, A. M. (2019). Reporting on violence against women and girls: A handbook for journalists. UNESCO. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=tDnLDwAAQBAJ (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Indian Country Today. (n.d.). RAINN and Debbie smith call on congress to reauthorize the Debbie smith act. Available online: https://ictnews.org/the-press-pool/rainn-and-debbie-smith-call-on-congress-to-reauthorize-the-debbie-smith-act (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Jennings, W. G., Powers, R. A., & Perez, N. M. (2021). A review of the effects of the violence against women act on law enforcement. Violence Against Women, 27(1), 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, T. (2009). A simple test of abortion and crime. Review of Economics and Statistics, 91(1), 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Z., Caetano, R., Vaeth, P., Gruenewald, P., Ponicki, W., Annechino, R., & Laqueur, H. (2024). The association between the percentage of female law enforcement officers and rape report, clearance, and arrest rates: A spatiotemporal analysis of California. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 39(1–2), 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, M. (2011). The day the white ribbon campaign changed the game: A new direction in working to engage men and boys. Available online: https://www.michaelkaufman.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/12/The-Day-the-White-Ribbon-Campaign-Changed-the-Game.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Kirker, A. (2021). Weathering fiscal uncertainty: A study of the effects of the Illinois budget impasse on rape crisis centers. Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority. Available online: https://icjia.illinois.gov/researchhub/articles/weathering-fiscal-uncertainty-a-study-of-the-effects-of-the-illinois-budget-impasse-on-rape-crisis-centers?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Koblin, J. (2015, January 2). The team behind the N.F.L.’s ‘No More’ campaign. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/04/style/the-team-behind-the-nfls-no-more-campaign.html (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Kwong, D. (2002). Removing barriers for battered immigrant women: A comparison of immigrant protections under VAWA. Berkeley Women’s Law Journal, 17, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, S. D. (2004). Understanding why crime fell in the 1990s: Four factors that explain the decline and six that do not. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(1), 163–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, R., & Mattsson, M. (2019). The effects of social movements: Evidence from #MeToo. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, B., & Johnson, I. M. (2009). Older African American women and barriers to reporting domestic violence to law enforcement in the rural deep south. Women & Criminal Justice, 19(4), 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, T., Evans, L., Stevenson, E., & Jordan, C. E. (2005). Barriers to services for rural and urban survivors of rape. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(5), 591–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, K., Dewald, S., & Venema, R. (2021). “I was worried I wouldn’t be believed”: Sexual assault victims’ perceptions of the police in the decision to not report. Violence and Victims, 36(3), 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, K., & Jacobsen, C. (2024). Sexual violence survivors’ experiences with the police and willingness to report future victimization. Women & Criminal Justice, 34(2), 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykke, L. C. (2016). Visibility and denial: Accounts of sexual violence in race-and gender-specific magazines. Feminist Media Studies, 16(2), 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łyś, A. E., Bargiel-Matusiewicz, K., & Studzińska, A. (2023). Perception of the presumption of innocence in the context of media depictions of violence: The role of participant’s gender, type of crime, and defendant’s socioeconomic status. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(11–12), 7824–7842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, C. D., Garner, J. H., & Fagan, J. A. (2002). The preventive effects of arrest on intimate partner violence: Research, policy and theory. Criminology & Public Policy, 2(1), 51–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, P., & Charlesworth, S. (2013). Framing sexual harassment through media representations. Women’s Studies International Forum, 37, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, K., Ringrose, J., & Keller, J. (2018). #MeToo and the promise and pitfalls of challenging rape culture through digital feminist activism. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 25(2), 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, V., Pattnaik, J. I., Bascarane, S., & Padhy, S. K. (2020). Role of media in preventing gender-based violence and crimes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 54, 102449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messing, J. T., Ward-Lasher, A., Thaller, J., & Bagwell-Gray, M. E. (2015). The state of intimate partner violence intervention: Progress and continuing challenges. Social Work, 60(4), 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Emerick, N. (2001). The violence against women act of 1994: An analysis of intent and perception. Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Modi, M. N., Palmer, S., & Armstrong, A. (2014). The role of violence against women act in addressing intimate partner violence: A public health issue. Journal of Women’s Health, 23(3), 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, A. M., & Gover, A. R. (2021). Violence against women: Reflecting on 25 years of the violence against women act and directions for the future. Violence Against Women, 27(1), 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Domestic Violence Hotline. (2018). Protect violence against women act: Ways to take action. Available online: https://www.thehotline.org/news/protect-violence-against-women-act-ways-to-take-action/ (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- National Organization for Women. (n.d.). ACTION ALERT: Reauthorize VAWA NOW. National Organization for Women. Available online: https://now.org/action-alert-reauthorize-vawa-now/ (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Novkov, J. (2019). The troubled confirmation of Justice Brett Kavanaugh. In D. Klein, & M. Marietta (Eds.), SCOTUS 2018 (pp. 125–141). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchowski, L. M., Grocott, L., Bogen, K. W., Ilegbusi, A., Amstadter, A. B., & Nugent, N. R. (2022). Barriers to reporting sexual violence: A qualitative analysis of #WhyIDidntReport. Violence Against Women, 28(14), 3530–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, L. A., Zinzow, H. M., Mccauley, J. L., Kilpatrick, D. G., & Resnick, H. S. (2014). Does encouragement by others increase rape reporting? Findings from a national sample of women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38(2), 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, K. M. (2014). Latina immigrants, interpersonal violence, and the decision to report to police. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(9), 1661–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RAINN. (n.d.). Sustaining and expanding services. RAINN. Available online: https://rainn.org/articles/sustaining-and-expanding-services (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Ranapurwala, S. I., Berg, M. T., & Casteel, C. (2016). Reporting crime victimizations to the police and the incidence of future victimizations: A longitudinal study. PLoS ONE, 11(7), e0160072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RedCorn, P. (2018). After delays halt reauthorization of violence against women act, native advocates urge action during domestic violence awareness month. National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center. Available online: https://www.niwrc.org/news/after-delays-halt-reauthorization-violence-against-women-act-native-advocates-urge-action (accessed on 14 August 2023).

- Rennison, C. M. (2002). Rape and sexual assault: Reporting to police and medical attention, 1992–2000 (NCJ 194530). U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/rsarp00.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Rennison, C. M. (2007). Reporting to the police by Hispanic victims of violence. Violence and Victims, 22(6), 754–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennison, C. M., DeKeseredy, W. S., & Dragiewicz, M. (2012). Urban, suburban, and rural variations in separation/divorce rape/sexual assault: Results from the national crime victimization survey. Feminist Criminology, 7(4), 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennison, C. M., Dragiewicz, M., & DeKeseredy, W. S. (2013). Context matters: Violence against women and reporting to police in rural, suburban and urban areas. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 38(1), 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezey, M. L., & Lauritsen, J. L. (2023). Crime reporting in Chicago: A comparison of police and victim survey data, 1999–2018. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 60(5), 664–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, L. (2020, February 19). The violence against women act—An ongoing fixture in the Nation’s response to domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking. Archives U.S. Department of Justice. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/archives/ovw/blog/violence-against-women-act-ongoing-fixture-nation-s-response-domestic-violence-dating (accessed on 14 August 2023).

- Rotenberg, C., & Cotter, A. (2018). Police-reported sexual assaults in Canada before and after #MeToo, 2016 and 2017 (pp. 1–27). Catalogue no. 85-002-X. Statistics Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, L. N. (2019). The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA): Historical overview, funding, and reauthorization. Available online: https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20190423_R45410_672f9e33bc12ac7ff52d47a8e6bd974d96e92f02.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2023).

- Sacco, L. N., & Hanson, E. J. (2019). The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA): Historical overview, funding, and reauthorization (CRS Report R45410). Congressional Research Service. pp. 1–42. Available online: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45410 (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Siefkes-Andrew, A. J., & Alexopoulos, C. (2019). Framing blame in sexual assault: An analysis of attribution in news stories about sexual assault on college campuses. Violence Against Women, 25(6), 743–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. R., & Bullock, H. E. (2020). An intersectional analysis of newspaper portrayals of the 2013 reauthorization of the violence against women act. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 6(4), 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slocum, L. A. (2018). The effect of prior police contact on victimization reporting: Results from the police–public contact and National Crime Victimization Surveys. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 34(2), 535–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. G., Zhang, X., Basile, K. C., Merrick, M. T., Wang, J., Kresnow, M. J., Chen, J., & National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (U.S.), Division of Violence Prevention. (2018). The national intimate partner and sexual violence Survey: 2015 data brief—Updated release. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/60893 (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Stanek, K. A., Fox, K. A., Telep, C. W., & Trinkner, R. (2023). Who can you trust? The impact of procedural justice, trust, and police officer sex on women’s sexual assault victimization reporting likelihood. Violence Against Women, 29(5), 860–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianou, A. M. (2016). Violence against women act. In C. L. Shehan (Ed.), Encyclopedia of family studies (1st ed., pp. 1–4). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, G., McCormack, A., Easteal, P., Holland, K., & Pirkis, J. (2016). Media guidelines for the responsible reporting of violence against women: A review of evidence and issues. Australian Journalism, 38(1), 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- The White House. (2022, March 16). Fact sheet: Reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA). The White House. Available online: https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/03/16/fact-sheet-reauthorization-of-the-violence-against-women-act-vawa/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Thomson, K. (2018, June 12). Social media activism and the #MeToo movement. Medium. Available online: https://medium.com/@kmthomson.11/social-media-activism-and-the-metoo-movement-166f452d7fd2 (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Tuerkheimer, D. (2017). Incredible women: Sexual violence and the credibility discount. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 166, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, S. E., & Filipas, H. H. (2001). Correlates of formal and informal support seeking in sexual assault victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 16(10), 1028–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (1994). United nations: General assembly resolution 48/104 containing the declaration on the elimination of violence against women. International Legal Materials, 33(4), 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Women, Molyneux, M., Dey, A., Gatto, M. A. C., & Rowden, H. (2021). New feminist activism, waves and generations. United Nations Women. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States v. Morrison, 529 U.S. 598. (2000).

- Viero, A., Barbara, G., Montisci, M., Kustermann, K., & Cattaneo, C. (2021). Violence against women in the COVID-19 pandemic: A review of the literature and a call for shared strategies to tackle health and social emergencies. Forensic Science International, 319, 110650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, K. G. (2011). Neutralizing sexual victimization: A typology of victims’ non-reporting accounts. Theoretical Criminology, 15(4), 445–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldon, S. L. (2002). Protest, policy, and the problem of violence against women: A cross-national comparison. University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldon, S. L., Lusvardi, A., Kelly-Thompson, K., & Forester, S. (2023). Feminist waves, global activism, and gender violence regimes: Genealogy and impact of a global wave. Women’s Studies International Forum, 99, 102781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2021). Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: Global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. World Health Organization. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/341337/9789240022256-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 14 August 2023).

- Wolitzky-Taylor, K. B., Resnick, H. S., McCauley, J. L., Amstadter, A. B., Kilpatrick, D. G., & Ruggiero, K. J. (2011). Is reporting of rape on the rise? A comparison of women with reported versus unreported rape experiences in the National Women’s Study-replication. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(4), 807–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2022). Violence against women and girls—What the data tell us. World Bank Gender Data Portal. Available online: https://genderdata.worldbank.org/data-stories/overview-of-gender-based-violence/ (accessed on 14 August 2023).

- Xie, M. (2014). Area differences and time trends in crime reporting: Comparing New York with other metropolitan areas. Justice Quarterly, 31(1), 43–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M., & Baumer, E. P. (2019). Crime victims’ decisions to call the police: Past research and new directions. Annual Review of Criminology, 2(1), 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M., Ortiz Solis, V., & Chauhan, P. (2023). Declining trends in crime reporting and victims’ trust of police in the United States and major metropolitan areas in the 21st century. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 40(1), 138–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaykowski, H., Allain, E. C., & Campagna, L. M. (2019). Examining the paradox of crime reporting: Are disadvantaged victims more likely to report to the police? Law & Society Review, 53(4), 1305–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweig, J., Farrell, L., Walsh, K., & Yu, L. (2021). Community approaches to sexual assault: VAWA’s role and survivors’ experiences. Violence Against Women, 27(1), 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Sexual Crime Count | % Sexual Crimes Within Year | % of Sexual Crimes Across Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 97 | 11.74 | 3.91 |

| 1993 | 131 | 10.41 | 5.28 |

| 1994 | 155 | 9.16 | 6.24 |

| 1995 | 118 | 8.24 | 4.75 |

| 1996 | 85 | 6.59 | 3.42 |

| 1997 | 80 | 6.92 | 3.22 |

| 1998 | 77 | 7.42 | 3.10 |

| 1999 | 89 | 9.31 | 3.58 |

| 2000 | 73 | 9.18 | 2.94 |

| 2001 | 62 | 8.20 | 2.50 |

| 2002 | 51 | 7.40 | 2.05 |

| 2003 | 50 | 7.90 | 2.01 |

| 2004 | 50 | 8.33 | 2.01 |

| 2005 | 43 | 8.55 | 1.73 |

| 2006 | 51 | 7.13 | 2.05 |

| 2007 | 57 | 9.15 | 2.30 |

| 2008 | 42 | 7.64 | 1.69 |

| 2009 | 29 | 5.50 | 1.17 |

| 2010 | 45 | 8.35 | 1.81 |

| 2011 | 54 | 9.76 | 2.17 |

| 2012 | 51 | 7.42 | 2.05 |

| 2013 | 56 | 9.15 | 2.26 |

| 2014 | 58 | 9.27 | 2.34 |

| 2015 | 79 | 11.33 | 3.18 |

| 2016 | 98 | 10.84 | 3.95 |

| 2017 | 135 | 12.45 | 5.44 |

| 2018 | 219 | 18.53 | 8.82 |

| 2019 | 146 | 13.98 | 5.88 |

| 2020 | 92 | 11.51 | 3.71 |

| 2021 | 110 | 12.70 | 4.43 |

| Total | 2483 | 9.69 | 100.00 |

| Reported Sexual Crimes | M | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992–2001 | 0.026 | 0.006 | 0.019 | 0.036 |

| 2002–2017 | 0.033 | 0.007 | 0.022 | 0.045 |

| 2018–2021 | 0.035 | 0.008 | 0.022 | 0.045 |

| Unreported Sexual Crimes | ||||

| 1992–2001 | 0.061 | 0.012 | 0.045 | 0.081 |

| 2002–2017 | 0.057 | 0.018 | 0.031 | 0.087 |

| 2018–2021 | 0.111 | 0.021 | 0.031 | 0.140 |

| Time Period | Predicted Probability | SE | z-Value | 95% CI [LL, UL] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992–2001 | 0.298 *** | 0.015 | 20.25 | [0.269, 0.327] |

| 2002–2017 | 0.362 *** | 0.016 | 23.23 | [0.332, 0.393] |

| 2018–2021 | 0.238 *** | 0.018 | 13.31 | [0.203, 0.273] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fleming, J.C.; Fansher, A.K.; Randa, R. From Policy Reform to Public Reckoning: Exploring Shifts in the Reporting of Sexual-Violence-Against-Women Victimizations in the United States Between 1992 and 2021. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 701. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050701

Fleming JC, Fansher AK, Randa R. From Policy Reform to Public Reckoning: Exploring Shifts in the Reporting of Sexual-Violence-Against-Women Victimizations in the United States Between 1992 and 2021. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):701. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050701

Chicago/Turabian StyleFleming, Jessica C., Ashley K. Fansher, and Ryan Randa. 2025. "From Policy Reform to Public Reckoning: Exploring Shifts in the Reporting of Sexual-Violence-Against-Women Victimizations in the United States Between 1992 and 2021" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 701. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050701

APA StyleFleming, J. C., Fansher, A. K., & Randa, R. (2025). From Policy Reform to Public Reckoning: Exploring Shifts in the Reporting of Sexual-Violence-Against-Women Victimizations in the United States Between 1992 and 2021. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 701. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050701