1. Introduction

Recent years have witnessed intensified global economic divergence and a transformation of China’s economy, resulting in heightened competition in the labor market and underscoring structural employment contradictions and talent mismatch issues. The devaluation of degrees resulting from the extensive proliferation of higher education intensifies supply–demand disparities. By 2025, the college graduate population in China is expected to reach 12.22 million, reflecting an annual increase of 430,000 (the 2025 national conference on the employment and entrepreneurship of graduates from regular institutions of higher learning was held (

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, 2025)). This trend is likely to intensify the existing “oversupply” in the labor market. In this environment, companies tend to prioritize highly qualified talent, while employees have to respond to competition through “downward-compatible” job choices or “involution-style” self-improvement, resulting in widespread talent “downskilling”. Perceived overqualification (POQ) has become an increasingly prevalent phenomenon. POQ is defined as employees’ perception that their jobs require lower knowledge and skills than they actually possess (

Shang et al., 2024). Surveys revealed that approximately 50% of employees globally (and 84% in China) perceive their qualifications to surpass job requirements (

M. J. Zhang et al., 2016), indicating the prevalence of perceived overqualification. Subjective perceptions of overqualification may differ from objective conditions; however, it is subjective experiences of employees that effectively predict work attitudes and behaviors (

Erdogan & Bauer, 2021;

Yang & Li, 2021). Therefore, perceived overqualification is an essential area for research and practice.

Current research on POQ focuses on singular perspectives, specifically negative effects represent the key scope of earlier studies that defined overqualification as a misallocation of human capital. Such misallocation cultivates perceptions of job mismatch, feelings of inequity, increased turnover intentions, and lower job satisfaction (

Erdogan et al., 2018). Counterproductive behaviors such as cyberloafing, work withdrawal, and workplace deviance may also result from it (

M. Wang et al., 2025;

W. Zhang et al., 2024). However, positive organizational scholarship indicates that high qualifications can elicit proactive cognitive appraisals. These appraisals may then transform into self-development drivers, motivating employees towards constructive behaviors such as innovation, organizational citizenship, and bootleg innovation (

Hu et al., 2015;

Luksyte & Spitzmueller, 2016;

Ma & Wang, 2024;

Shang et al., 2024). These contradictions suggest that perceived overqualification operates as a double-edged sword. Its effects are contingent upon how employees cognitively appraise and affectively react to job-person mismatch (

Yang & Li, 2021). Existing research, however, has primarily utilized single-path explanations (e.g., cognitive or affective mechanisms). Therefore, it is often insufficient in explaining the interaction of these parallel processes in driving divergent behavioral outcomes (

P. Li et al., 2021). An integrative framework is therefore needed to reconcile the dual effects of perceived overqualification due to this theoretical fragmentation. A promising perspective is offered by the Cognitive–Affective Personality System (CAPS) theory. This theory hypothesizes that situational features (including both external organizational contexts and internal psychological states) simultaneously activate individuals’ cognitive and affective systems, which jointly shape behavioral responses (

Walter & Yuichi, 1995). Moreover, the relative dominance of cognitive versus affective unit activation determines ultimate behavioral choices (

Walter & Yuichi, 1995).

Job crafting refers to the proactive modifications made by employees to their job content and responsibilities from a bottom–up perspective (

Dutton, 2001;

R. Liu & Yin, 2024). This concept comprises both approach and avoidance behavioral dimensions (

Bruning & Campion, 2018). The mismatch in overqualification can be mitigated by this adaptive behavior; in addition, it offers a critical perspective through which to analyze the dual-edged effects of perceived overqualification. When employees are effectively incentivized to improve job-person fit, negative outcomes may be mitigated, and their latent potential can be unlocked (

Xie et al., 2015). Thus, directing POQ employees toward approach job crafting has emerged as a pivotal organizational challenge. However, achieving academic consensus regarding the relationships between POQ and job crafting continues to be elusive. It is contended by certain studies that employees with perceived overqualification often lower their job crafting efforts. This reduction aims to restore psychological balance which is disrupted by perceived breaches of psychological contracts and inequity (

Z. Wang et al., 2019). Conversely, others propose that employees who feel overqualified leverage their qualifications to actively improve job–person fit through proactive job crafting (

F. Zhang et al., 2021). A nonlinear mechanism has also been proposed, indicating that moderate POQ fosters job crafting via resource accumulation, while excessive POQ triggers emotional depletion and inhibits such efforts (

Woo, 2020). These inconsistencies may arise from three gaps: (1) Prior studies often do not distinguish between approach job crafting (motivated by growth) and avoidance job crafting (driven by stress avoidance), despite their divergent motivational roots; (2) Integrated perspectives are frequently neglected in existing research, which primarily isolates cognitive or affective pathways (

P. Li et al., 2021); thus, the fundamental question regarding whether perceived overqualification exerts overall positive or negative effects on job crafting lacks adequate resolution; (3) The role of contextual factors, such as organizational interventions, remain understudied in the dynamics between POQ and job crafting.

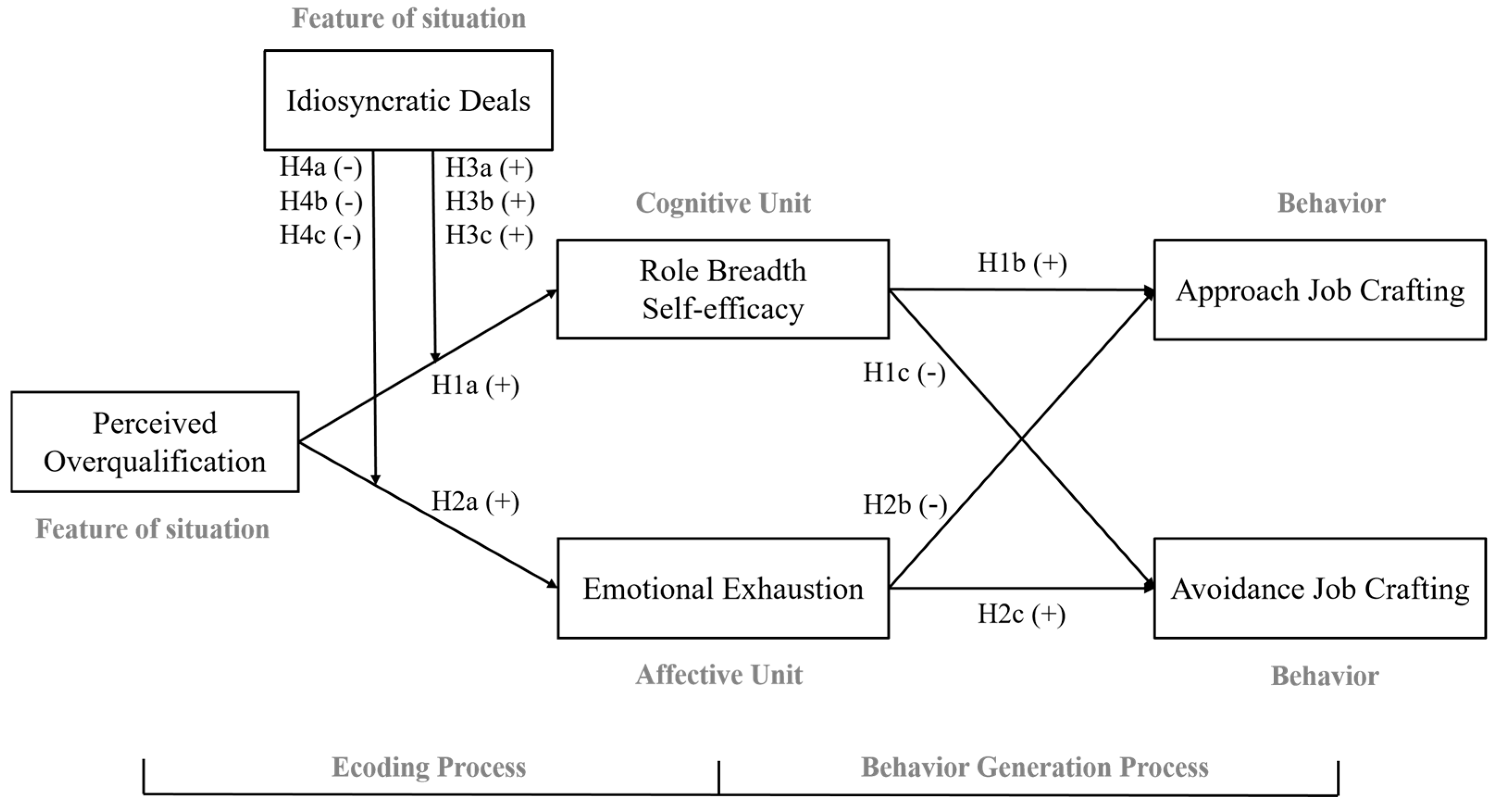

To address the aforementioned gaps, this study puts forward a dual-path model based on the Cognitive–Affective Personality System theory. The theory posits that situational features dynamically drive behavioral choices by activating individuals’ parallel cognitive and affective processing units (

Walter & Yuichi, 1995). More specifically, perceived overqualification, understood as an internal psychological state of perceived person–job misfit, can have two primary effects: (1) it may enhance employees’ positive cognitive appraisals of their capabilities and role expansion (

Chu et al., 2021;

M. J. Zhang et al., 2016), which amounts to role breadth self-efficacy (RBSE, cognitive unit), and (2) it can trigger negative emotional responses such as anger, boredom, and anxiety (

Arvan et al., 2022;

Chen et al., 2017;

Peng et al., 2023), thereby exacerbating emotional exhaustion (EE, affective unit). Approach and avoidance job crafting are differentially driven by these dual psychological mechanisms. Along the cognitive pathway, POQ elevates role breadth self-efficacy, thereby bolstering confidence to pursue approach crafting and inhibiting avoidance behaviors. Along the affective pathway, POQ intensifies emotional exhaustion, suppressing approach crafting and amplifying avoidance tendencies. The capacity of situational interventions to modulate cognitive–affective dynamics is also emphasized by the CAPS theory (

Walter & Yuichi, 1995). This premise underpins our introduction of idiosyncratic deals (i-deals) as a contextual intervention mechanism; i-deals are designed to recalibrate employees’ psychological responses and behavioral choices regarding POQ. In organizations, overqualified employees often represent underutilized high-quality resources. I-deals refer to mutually beneficial, negotiated work arrangements featuring customized terms between organizations and employees (

D. Rousseau, 2001). Such i-deals, when tailored for these high-potential employees, have the capability to enhance positive cognitive appraisals while mitigating negative affective reactions, ultimately fostering proactive work behaviors.

In summary, this study develops a dual-path integrated model grounded in the Cognitive–Affective Personality System theory to resolve three core questions: (1) Does POQ drive approach and avoidance job crafting? (2) What cognitive and affective mechanisms underlie these effects? (3) Under what boundary conditions do these pathways yield positive outcomes? This research seeks to offer three key contributions through addressing these questions. (1) It integrates theoretical perspectives. The introduction of CAPS theory into the study of POQ and job crafting allows for the construction of a parallel cognitive–affective mediation mechanism. This mechanism indicates the competitive interaction between cognitive and affective pathways, and such a dynamic framework helps reconcile paradoxical behavioral outcomes, thereby advancing a holistic understanding of POQ’s dual-edged nature. (2) The study achieves contextual boundary expansion. It elucidates how idiosyncratic deals (i-deals) serve as contextual interventions that differentially moderate the dual pathways, which expands the boundary conditions for how perceived overqualification influences job crafting. (3) Practical implications are offered. This research offers actionable guidance for organizations to implement targeted interventions that unlock the potential of overqualified employees.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedures

Questionnaires were distributed through both online and offline channels, and the Wenjuanxing platform (a widely used Chinese survey tool) was utilized for all data collection. On the one hand, human resource department managers from organizations were contacted via phone calls and emails. After obtaining consent, electronic survey links were randomly distributed to employees. On the other hand, working professionals within the authors’ personal networks (e.g., friends, family members, and colleagues) were invited to participate, and the survey was further disseminated through snowball sampling. To ensure broader sample diversity and improved representativeness, initial respondents were asked to recommend potential participants with the following characteristics: (1) colleagues from different departments; (2) a difference in work experience of more than two years; and (3) different educational levels. To mitigate common method bias, data were collected in two phases. In Phase 1 (May 2024), 700 questionnaires were distributed, yielding 651 valid responses. This phase focused on measuring perceived overqualification, idiosyncratic deals, and demographic variables (e.g., age, gender). In Phase 2 (July 2024), the same 651 participants received follow-up questionnaires, achieving 597 valid responses. This phase targeted role breadth self-efficacy, emotional exhaustion, approach job crafting, and avoidance job crafting. After pairing data from the two phases and eliminating invalid responses (e.g., patterned answers, completion time < 120 s), a final sample of 556 participants was retained for analysis.

Among the 556 valid participants, 43.53% identified as male and 56.47% as female. Regarding age, 37.77% were 25 years old or younger, 42.81% were between 26 and 35 years old, and 19.42% were 36 years old or above. In terms of educational attainment, 86.33% held a bachelor’s degree or higher, including master’s and doctoral degrees. For marital status, 63.67% were unmarried, while 36.33% were married. With respect to work experience, 61.15% had three years or less of tenure, and 38.85% had more than three years. In the distribution of job categories, 38.85% worked in administrative/functional roles, 23.74% in professional/technical roles, 18.18% in marketing/sales roles, 10.97% in production/operations roles, and 8.27% in other roles. Hierarchically, 56.29% were non-managerial employees, 24.28% were frontline supervisors, and 19.42% were middle-to-senior managers. Participants were employed across diverse organizational types: 24.82% in state-owned enterprises, 41.19% in private enterprises, 10.79% in joint-venture/foreign-funded companies, 13.85% in government/public institutions, and 9.35% in other sectors. Overall, the sample exhibited balanced diversity across demographic categories, hierarchical levels, and organizational contexts. The high proportion of highly educated individuals aligns with the study’s focus, as prior research suggests that those with advanced education are more prone to perceive overqualification in situations of person–job mismatch. This characteristic underscores the validity of the sample for addressing the research objectives.

3.2. Measurement

Well-validated scales, widely recognized in prior research and once applied in the Chinese context, were employed in this study. To enhance contextual applicability in Chinese organizational settings for Western-developed scales originally situated in non-Chinese contexts, translation and contextual adaptation of measurement items were conducted; this was achieved through referencing domestic localization studies and adhering to Chinese linguistic conventions. The questionnaire was designed using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly Agree”), with higher scores indicating greater agreement. The questionnaire is presented in

Appendix A.

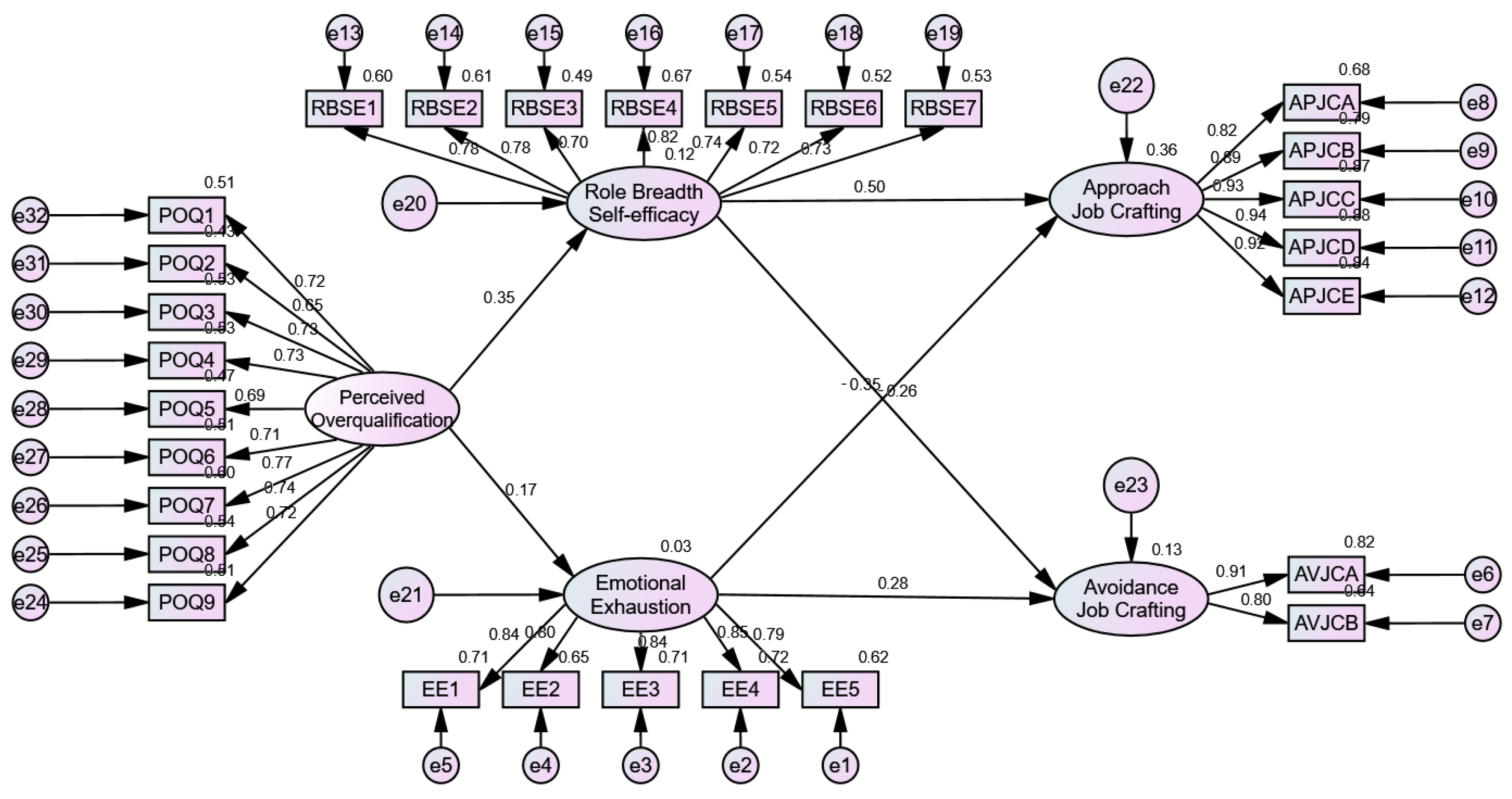

Perceived Overqualification was measured with the unidimensional 9-item scale developed by

Maynard et al. (

2006). A sample item includes “My skill level exceeds what is required to perform my job”.

Role Breadth Self-Efficacy was assessed using

Parker et al.’s (

2006) 7-item unidimensional scale. A representative item is “I can design new procedures for my work area”.

Emotional Exhaustion was evaluated through a unidimensional 5-item scale translated and adapted by Chinese scholars

C. Li and Shi (

2003). A sample item states “My job leaves me feeling emotionally and physically drained”.

Approach Job Crafting was measured using

Bruning and Campion’s (

2018) 23-item scale comprising five dimensions: work organization, adaptability, metacognition, role expansion, and social expansion. An example item is “I apply new knowledge or technology to automate tasks and enhance efficiency”.

Avoidance Job Crafting was captured via

Bruning and Campion’s (

2018) 7-item scale, including dimensions of role reduction and withdrawal. A sample item reads “I find ways to avoid time-consuming work tasks”.

Idiosyncratic Deals were assessed using

Rosen et al.’s (

2013) 16-item scale with four dimensions: task customization, schedule flexibility, location flexibility, and compensation incentives. An example item is “My supervisor considers my personal needs when assigning work schedules”.

Prior studies suggest that demographic differences (e.g., gender, age, education) may influence perceived overqualification and job crafting behaviors. To isolate the effects of core variables, this study controlled for employees’ gender, age, education, marital status, years of work, position category, position level, and nature of organization in the analysis. These controls ensure that observed relationships are not confounded by extraneous demographic factors.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to reconcile inconsistent findings regarding the relationship between perceived overqualification and job crafting; for this purpose, an integrated “dual-pathway dual-outcome” model based on the Cognitive–Affective Personality System (CAPS) theory was constructed. Validation for all 12 proposed hypotheses was offered by the empirical results, and the principal findings are outlined as follows:

- (1)

Perceived overqualification differentially influences approach and avoidance job crafting through the dual pathways of “cognitive drive” and “affective inhibition”.

Perceived overqualification (POQ), as an internal psychological state of person–job mismatch, can simultaneously activate employees’ cognitive perceptions and affective experiences (

Yang & Li, 2021), leading to divergent behavioral choices. Along the cognitive pathway, perceived overqualification positively promotes approach job crafting and negatively inhibits avoidance job crafting by enhancing role breadth self-efficacy (RBSE). Employees who perceive themselves as overqualified develop positive self-perceptions of capability surplus (manifested as RBSE), motivating proactive role expansion to resolve mismatch, aligning with the findings of

M. J. Zhang et al. (

2016). Notably, this study extends prior research by revealing RBSE’s negative impact on avoidance job crafting, which is a novel contribution to understanding inhibitory antecedents of passive work behaviors. Along the affective pathway, perceived overqualification negatively inhibits approach job crafting and positively influences avoidance job crafting by exacerbating emotional exhaustion. Overqualified employees who fixate on external job–person mismatch rather than internal self-regulation are susceptible to negative emotions, including boredom, anxiety, and anger, which can result in emotional exhaustion. This is consistent with the findings of

Erdogan et al. (

2018) and

X. Li et al. (

2021). Proactive approach behaviors are excluded by emotionally depleted employees due to resource depletion; these employees instead adopt avoidance strategies such as task simplification and social withdrawal to alleviate stress. While the positive effect of emotional exhaustion on negative behaviors such as work withdrawal has been the predominant focus of prior research (

Xin et al., 2024), its influence on proactive behaviors such as approach job crafting has received less attention. This study therefore not only validates the positive impact of emotional exhaustion on avoidance job crafting but also confirms its significant negative impact on approach job crafting, addressing the call by

Zeijen et al. (

2018) to explore diverse antecedents of job crafting.

Building upon these findings, the interactive effects between cognitive and affective pathways were further analyzed in this study. A positive and significant overall indirect effect of perceived overqualification on approach job crafting is indicated by the results; this effect operates through the combined cognitive gain pathway of role breadth self-efficacy and the affective depletion pathway of emotional exhaustion, indicating the dominance of cognitive unit’s enhancement effects in behavioral choices. However, through the inhibitory pathway of role breadth self-efficacy and the reinforcing pathway of emotional exhaustion, perceived overqualification generates opposing effects that cancel each other out, resulting in non-significant overall indirect effects on avoidance job crafting. The competitive interaction mechanism between cognitive and affective units in CAPS theory (

Walter & Yuichi, 1995) is verified by this result. To explain the non-significant effects on avoidance job crafting, dual theoretical explanations are proposed. First, behavioral inhibition may be created by the conflicting coexistence of empowerment and strain. Role breadth self-efficacy from competence surplus and emotional exhaustion from needs–abilities imbalance are also developed by overqualified employees. Psychological conflict during avoidance decision-making is triggered by this empowerment strain paradox—cognitive control suppresses withdrawal tendencies while affective fatigue reinforces avoidance motives—which amounts to statistical neutrality in behavioral outcomes. Second, floor effects due to organizational thresholds may constrain avoidance behaviors. Minimum job performance standards are mandated by workplace norms, meaning that a reduction in task engagement below functional baselines by even emotionally exhausted employees is unlikely. The oversimplified “either positive or negative” dichotomy regarding perceived overqualification is challenged by these findings; they confirm that its impact direction and intensity on job crafting depend on specific behavioral types (approach vs. avoidance) and the relative dominance of cognitive–affective pathways. The complexity of dual-path mechanisms is indicated by this research, which also demonstrates that integrating cognitive and affective pathways is necessary to interpret complex behavioral outcomes. Dynamic effects of situational features might be obscured by relying solely on single mechanisms, whereas the CAPS framework offers a theoretical tool for unraveling such complexities.

- (2)

Idiosyncratic deals (i-deals) serve as a positive moderator in the mechanisms of perceived overqualification.

Organizational contextual interventions can reshape individuals’ cognitive and affective responses, as hypothesized by the Cognitive–Affective Personality System theory (

Walter & Yuichi, 1995). As a differentiated and flexible organizational support mechanism, i-deals significantly moderate the interaction between perceived overqualification and employees’ cognitive–affective responses. Although overqualified employees operate in a psychological context of perceived mismatch, organizations can amplify cognitive gains (enhancing role breadth self-efficacy) and buffer affective depletion (mitigating emotional exhaustion) through personalized job arrangements that provide resource-rich external contexts. This subsequently motivates overqualified employees to adopt approach job crafting for proactive breakthroughs while suppressing avoidance job crafting. This aligns with the “if–then” pattern proposed by CAPS theory (

Walter & Yuichi, 1995): if contextualized support (i-deals) is provided, then the cognitive–affective system generates adaptive behaviors.

In the Chinese context, the effectiveness of i-deals can be interpreted through the cultural sensitivity of CAPS. The theory emphasizes that situational characteristics are interpreted through culturally shaped cognitive–affective filters (

Walter & Yuichi, 1995). In Confucian-influenced societies valuing “people-oriented philosophy” and “harmony in diversity”, employees may perceive i-deals not merely as transactional arrangements but as symbolic gestures respecting individual uniqueness. This cultural lens amplifies i-deals’ capacity to activate positive cognitive schemas (e.g., “I am recognized”) and inhibit negative affective responses (e.g., “I feel constrained”), thereby strengthening their moderating effects within the CAPS framework. Therefore, by incorporating i-deals as a moderating variable, this study not only responds to

Yang and Li ’s (

2021) appeal to examine the interaction between organizational contextual factors and perceived overqualification but also demonstrates the application of ancient Chinese philosophies in contemporary human resource management practices.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Theoretical understanding is advanced by this study utilizing a dual-path integrated model that elucidates the intricate relationship between perceived overqualification and job crafting; two primary theoretical contributions are offered:

- (1)

Integration of dual pathways within the CAPS framework

Theoretically, single-perspective limitations are transcended by this research through the introduction of the Cognitive–Affective Personality System (CAPS) theory for integrating cognitive and affective pathways. A dynamic explanatory framework for conflicting behavioral outcomes is offered by its revelation of the competitive relationship between these pathways. Previous research primarily carried out analyses of the effect of perceived overqualification on job crafting through isolated cognitive or affective mechanisms, thereby neglecting their concurrent effects (

P. Li et al., 2021). Grounded in the CAPS theory, this study delineates the dynamic process whereby individuals translate perceived overqualification into distinct job crafting strategies; this occurs through dual mechanisms of cognitive appraisal and emotional regulation. Cognitive and affective pathways operate in competition, as demonstrated by the findings, and approach/avoidance job crafting are not mutually exclusive but coexist as products of cognitive–affective tension, which is a novel insight unattainable through single-path models. Therefore, the proposed “dual-pathway dual-outcome” model provides a holistic theoretical explanation for understanding the nuanced relationship between perceived overqualification and job crafting behaviors. Furthermore, the analysis of overall indirect effects uncovers the competitive dynamics between cognitive and affective pathways, resonating with CAPS’ emphasis on the dynamic interaction of cognition and emotion.

- (2)

Contextual moderating mechanisms within the CAPS framework

Regarding contextual mechanisms, idiosyncratic deals (i-deals) are introduced by this study as situational amplifiers/buffers within the CAPS framework; their differential moderating effects are explored to expand the boundary conditions of how perceived overqualification influences job crafting. While exploration of i-deals as moderators of work behaviors has occurred in existing research (

Xiang et al., 2023), their differential impacts across cognitive and affective pathways remained unclear. This work clarifies how i-deals shape boundary conditions for approach and avoidance job crafting along both pathways, demonstrating how tailored organizational interventions tilt the cognitive–affective equilibrium toward desired outcomes. These findings not only broaden the theoretical scope of perceived overqualification research but also offer targeted theoretical guidance for organizations to optimize employee management strategies and effectively motivate overqualified employees through contextual interventions.

5.2. Managerial Implications

Perceived overqualification is a prevalent issue with challenges, necessitating proactive organizational responses through systematic human resource management practices to address its dual effects. Actionable insights are offered by this study, enabling organizations to leverage the positive outcomes of perceived overqualification while working to lessen its negative effects.

First, an acknowledgement of perceived overqualification’s dual nature is crucial for organizations, which should also adopt prudent matching strategies during recruitment. If person–job fit is prioritized, organizations should conduct rigorous job analyses and competency assessments to ensure alignment between candidates and job requirements, thereby minimizing perceived overqualification at its origin. If hiring highly qualified and promising employees is necessary for organizational development, organizations should engage in thorough communication with these employees, establish clear career development plans, and provide diversified support for career growth (e.g., cross-departmental rotations, internal promotions) to help them envision future growth opportunities.

Second, the implementation of training programs by organizations can enhance employees’ positive cognitive appraisals of perceived overqualification and strengthen their self-efficacy. For instance, case studies and scenario-based workshops are effective tools for demonstrating how surplus qualifications can be utilized extend beyond formal job descriptions. Employees can be guided to apply their excess skills in cross-functional collaborations, innovation initiatives, or internal consulting roles. Such interventions not only reframe perceived overqualification as an organizational asset but also stimulate proactive job crafting behaviors.

Third, proactive monitoring and addressing of emotional exhaustion, which can be triggered by perceived overqualification, are essential organizational responsibilities. The institutionalization of regular mental health assessments and targeted counseling services can aid in identifying and mitigating negative emotions. Open communication channels, such as supervisor–employee dialogues, peer support groups, or anonymous feedback platforms, can help employees voice their concerns and reduce feelings of stagnation. Cultivating an empathetic work environment allows organizations to redirect employees’ frustration into constructive work adaptation efforts, thereby achieving mutually beneficial outcomes.

Finally, idiosyncratic deals (i-deals) should be strategically designed and dynamically adjusted to maximize their moderating effects. Periodic interviews or surveys can be conducted by organizations to capture employees’ evolving preferences for work content, career development, and work–life balance. Developing tailored i-deals based on individual needs is crucial for employees who value autonomy and challenge, offering high-responsibility projects and flexible task ownership can enhance engagement, and for those prioritizing work–life balance, in which case remote work options or adjustable schedules can mitigate perceptions of wasted potential. It is essential to periodically review and refine i-deals to maintain alignment with employee aspirations and organizational objectives, thus ensuring their continued motivational effectiveness.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Notwithstanding its contributions, this study is not without certain limitations for future improvement.

Initially, the first set of limitations related to methodological constraints, as all variables were measured with self-reported assessments, which carries the potential for common method bias. Although multi-wave data collection through blended online and offline channels was implemented and statistical tests indicated no severe bias, future research should incorporate more objective evaluation methods; for instance, supervisor or peer assessments could be utilized for employees’ job crafting behaviors. Another methodological concern is that, notwithstanding the two-wave data collection, mediators (role breadth self-efficacy and emotional exhaustion) and outcomes (approach and avoidance job crafting) were measured simultaneously. Even though mediators were placed before outcome variables in the questionnaire, this design cannot fully establish temporal precedence. Therefore, our recommendation for future studies is the adoption of three-phase longitudinal designs. Finally, longitudinal and tracking studies could be combined, supplemented by case analysis, experimental methods, and meta-analysis, to cross-validate findings and ensure the robustness of conclusions.

Secondly, there are content limitations. For instance,

Maltarich et al. (

2011) proposed the notion of “voluntary mismatch”, positing that certain underemployed individuals might deliberately choose simpler jobs or lower positions to engage in activities of genuine interest or to allocate more time for family. Therefore, future research could benefit from exploring different types of POQ. Moreover, while this model focuses on organizational contextual moderators (i-deals) due to the relative stability of individual traits, personal characteristics such as mindfulness and proactive personality could potentially interact with situational factors to shape job crafting responses. Accordingly, the effect analysis of trait–situation interactions on the mechanisms between perceived overqualification and job crafting behaviors is a valuable area for further studies. Finally, employees predisposed to proactive job crafting may be more likely to initiate negotiations for i-deals, suggesting a potential reverse causality between the two constructs. Longitudinal designs or experimental approaches are recommended for future studies to further examine the temporal dynamics of this relationship.

Thirdly, the cultural applicability of the findings presents a limitation due to the scope of this study on variable relationships being confined to China’s Confucian culture, potentially restricting the cross-cultural generalizability of the results. Future research could test the reliability and universality of our conclusions by examining the relationship between perceived overqualification and job crafting across diverse cultural settings, using samples from different cultural backgrounds.