Non-Suicidal Self-Injury among Adolescents: Effect of Knowledge, Attitudes, Role Perceptions, and Barriers in Mental Health Care on Teachers’ Responses

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Teachers’ Perceptions of Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in the Schools

1.2. The Current Research

2. Methods

2.1. Research Process

2.2. Participants

2.3. Research Tool

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

4.2. Practical Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Riggi, M.E.; Moumne, S.; Heath, N.L.; Lewis, S.P. Non-suicidal self-injury in our schools: A review and research-informed guidelines for school mental health professionals. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 2017, 32, 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madjar, N.; Sarel-Mahlev, E.; Klomek, A.B. Depression symptoms as mediator between adolescents’ sense of loneliness at school and nonsuicidal self-injury behaviors. Crisis 2020, 42, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streeto, C.; Phillips, K.E. Compassion satisfaction and burnout are related to psychiatric nurses’ antipathy towards nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI). J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2022, 30, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmakar, S.; Duggal, C. Trauma-informed approach to qualitative interviewing in non-suicidal self-injury research. Qual. Health Res. 2024, 34, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooley, J.M.; Fox, K.R.; Boccagno, C. Nonsuicidal self-injury: Diagnostic challenges and current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 10, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Yang, X.; Xin, M. Impact of violent experiences and social support on R-NSSI behavior among middle school students in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serafini, G.; Aguglia, A.; Amerio, A.; Canepa, G.; Adavastro, G.; Conigliaro, C.; Nebbia, J.; Franchi, L.; Flouri, E.; Amore, M. The relationship between bullying victimization and perpetration and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2023, 54, 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brager-Larsen, A.; Zeiner, P.; Mehlum, L. Sub-threshold or full-syndrome borderline personality disorder in adolescents with recurrent self-harm–distinctly or dimensionally different? Borderline Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregulation 2023, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crone, E.A.; Fuligni, A.J. Self and others in adolescence. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2020, 71, 447–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K.; Prinstein, M.J.; Sterba, S.K. Revealing the form and function of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: A real-time ecological assessment study among adolescents and young adults. Psychol. Violence 2010, 1, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L.; Sheridan, A.; Treacy, M.P. Motivations for adolescent self-harm and the implications for mental health nurses. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 24, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.; Ammerman, B.A. How should we respond to non-suicidal self-injury disclosures?: An examination of perceived reactions to disclosure, depression, and suicide risk. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, E.; Reupert, A.; Hasking, P. Pre-service and in-service teachers’ knowledge, attitudes and confidence towards self-injury among pupils. J. Educ. Teach. 2015, 41, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, K.; Xue, C.; Li, C.; Gu, C. The impact of self-consistency congruence on Non-suicidal self-injury in college students: The mediating role of negative emotion and the moderating role of gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, R.H.; Shahwan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Sambasivam, R.; Ong, S.H.; Subramaniam, M. How do professionals and non-professionals respond to non-suicidal self-injury? Lived experiences of psychiatric outpatients in Singapore. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, E.; Hasking, P.; Martin, G. ‘Listen to them’: Adolescents’ views on helping young people who self-injure. J. Adolesc. 2013, 36, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, E.; Hasking, P.; Reupert, A. Developing a policy to address nonsuicidal self-injury in schools. J. Sch. Health 2015, 85, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiekens, G.; Hasking, P.; Nock, M.K.; Boyes, M.; Kirtley, O.; Bruffaerts, R.; Myin-Germeys, I.; Claes, L. Fluctuations in affective states and self-efficacy to resist non-suicidal self-injury as real-time predictors of non-suicidal self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.H.; Jeong, Y.W.; Kang, Y.H.; Kim, S.W.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, K.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Choi, D.B. Mediating the effects of depression in the relationship between university students’ attitude toward suicide, frustrated interpersonal needs, and non-suicidal self-injury during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2022, 37, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grové, C.; Marinucci, A.; Riebschleger, J. Development of an American and Australian co-designed youth mental health literacy program. Front. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 1, 1018173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groschwitz, R.; Munz, L.; Straub, J.; Bohnacker, I.; Plener, P.L. Strong schools against suicidality and self-injury: Evaluation of a workshop for school staff. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2017, 32, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, C.; Satherley, R.M.; Jones, C.J.; John, M. Development and Evaluation of an eLearning Training Module to Improve United Kingdom Secondary School Teachers’ Knowledge and Confidence in Supporting Young People Who Self-Harm. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 889659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, K.; Deane, F.P.; Miller, L. Attributions about self-harm: A comparison between young people’s self-report and the functions ascribed by preservice teachers and school counsellors. J. Psychol. Couns. Sch. 2023, 33, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, C.A.; Robinson, K.; Hasking, P.A.; Heath, N.L.; Lewis, S.P.; Lloyd-Richardson, E.; Whitlock, J.; Wilson, M.S. Educational stakeholders’ attitudes and knowledge about nonsuicidal self-injury among university students: A cross-national study. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 2140–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riebschleger, J.; Grové, C.; Cavanaugh, D.; Costello, S. Mental health literacy content for children of parents with a mental illness: Thematic analysis of a literature review. Brain Sci. 2017, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinucci, A.; Grové, C.; Rozendorn, G. “It’s something that we all need to know”: Australian youth perspectives of mental health literacy and action in schools. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 829578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyoseph, Z.; Levkovich, I. Beyond the Surface: Teachers’ Perceptions and Experiences in Cases of Non-Suicidal Self-Injury among High School Students. OMEGA-J. Death Dying 2024, 302228231223275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillippo, K.L.; Kelly, M.S. On the fault line: A qualitative exploration of high school teachers’ involvement with student mental health issues. Sch. Ment. Health 2014, 6, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, M.L.; Gray, A.S.; Lancaster, T.M.; Grenyer, B.F. A whole of school intervention for personality disorder and self-harm in youth: A pilot study of changes in teachers’ attitudes, knowledge and skills. Borderline Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregulation 2018, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro-Coimbra, L.R.; Noakes, A. A systematic review into healthcare professionals’ attitudes towards self-harm in children and young people and its impact on care provision. J. Child Health Care 2022, 26, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Yim, M.; Hur, J.W. Beneath the surface: Clinical and psychosocial correlates of posting nonsuicidal self-injury content online among female young adults. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 132, 107262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, B.; Blazely, A.; Phillips, L. Stigma towards individuals who self harm: Impact of gender and disclosure. J. Public Ment. Health 2018, 17, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Manktelow, R.; Tracey, A. The healing journey: Help seeking for self-injury among a community population. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 932–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maclean, L.; Law, J.M. Supporting primary school students’ mental health needs: Teachers’ perceptions of roles, barriers, and abilities. Psychol. Sch. 2022, 59, 2359–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semchuk, J.C.; McCullough, S.L.; Lever, N.A.; Gotham, H.J.; Gonzalez, J.E.; Hoover, S.A. Educator-informed development of a mental health literacy course for school staff: Classroom well-being information and strategies for educators (Classroom WISE). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzer, K.R.; Rickwood, D.J. Teachers’ role breadth and perceived efficacy in supporting student mental health. Adv. Sch. Ment. Health Promot. 2015, 8, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simundic, A.; Hove, L.V.; Baetens, I.; Bloom, E.; Heath, N. Nonsuicidal self-injury in elementary schools: School educators’ knowledge and professional development needs. Psychol. Sch. 2024, 61, 1868–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plener, P.L.; Schumacher, T.S.; Munz, L.M.; Groschwitz, R.C. The longitudinal course of non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm: A systematic review of the literature. Borderline Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregulation 2015, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamama, L.; Ronen, T.; Shachar, K.; Rosenbaum, M. Links between stress, positive and negative affect, and life satisfaction among teachers in special education schools. J. Happiness Stud. 2013, 14, 731–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelemy, L.; Harvey, K.; Waite, P. Secondary school teachers’ experiences of supporting mental health. J. Ment. Health Train. Educ. Pract. 2019, 14, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; Parker, R.; Russell, A.E.; Mathews, F.; Ford, T.; Hewitt, G.; Scourfield, J.; Janssens, A. Adolescent self-harm prevention and intervention in secondary schools: A survey of staff in England and Wales. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2019, 24, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, M.; Manktelow, R.; Tracey, A. We are all in this together: Working towards a holistic understanding of self-harm. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2013, 20, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenrot, S.A.; Lewis, S.P. Barriers and responses to the disclosure of non-suicidal self-injury: A thematic analysis. Couns. Psychol. Q. 2020, 33, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.C.; Straub, J.; Bohnacker, I.; Plener, P.L. Increasing knowledge, skills, and confidence concerning students’ suicidality through a gatekeeper workshop for school staff. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, S.A.; Alenezi, S.; Alanzan, A.; AlHawamdeh, A.; Alsulaiman, O.; Alqarni, N.; Aldraihem, S.; Alsunbul, N. Knowledge, attitudes and practice among high school teachers toward students with mental disorders in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, M.; Creedy, D.; Moyle, W.; Farrugia, C. Nurses’ attitudes towards clients who self-harm. J. Adv. Nurs. 2002, 40, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, D.; Warm, A. A study of service providers’ understanding of self-harm. J. Ment. Health 2002, 11, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, T.; Geraghty, W.; Street, K.; Simonoff, E. Staff knowledge and attitudes towards deliberate self-harm in adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2003, 26, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinke, W.M.; Stormont, M.; Herman, K.C.; Puri, R.; Goel, N. Supporting children’s mental health in schools: Teacher perceptions of needs, roles, and barriers. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2011, 26, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Introd. Mediat. Moderat. Cond. Process Anal. A Regres.-Based Approach 2013, 1, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson New International Edition; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biringen, Z.; Derscheid, D.; Vliegen NClosson, L.; Easterbrooks, M.A. Emotional availability (EA): Theoretical background, empirical research using the EA Scales, and clinical applications. Dev. Rev. 2014, 34, 114–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, M.S.; Pine, F.; Bergman, A. The Psychological Birth of the Human Infant: Symbiosis and Individuation; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Levkovich, I.; Vigdor, I. How school counsellors cope with suicide attempts among adolescents—A qualitative study in Israel. J. Psychol. Couns. Sch. 2021, 31, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; FT Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| f | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 15 | 7.4 |

| Female | 188 | 92.6 | |

| Family status | Single | 24 | 13.1 |

| Married | 142 | 77.6 | |

| Divorced | 13 | 7.1 | |

| Widowed | 2 | 1.1 | |

| Other | 2 | 1.1 | |

| Education | BA | 73 | 36.0 |

| MA | 128 | 63.0 | |

| PHD | 2 | 1.0 | |

| Education type | Regular education | 124 | 61.1 |

| Special education | 79 | 38.9 | |

| Past experience with NSSI? | No | 86 | 42.4 |

| Yes | 117 | 57.6 | |

| Mean | SD | Range | |

| Age | 39.99 | 9.18 | 24–64 |

| Education seniority | 12.73 | 9.16 | 1–35 |

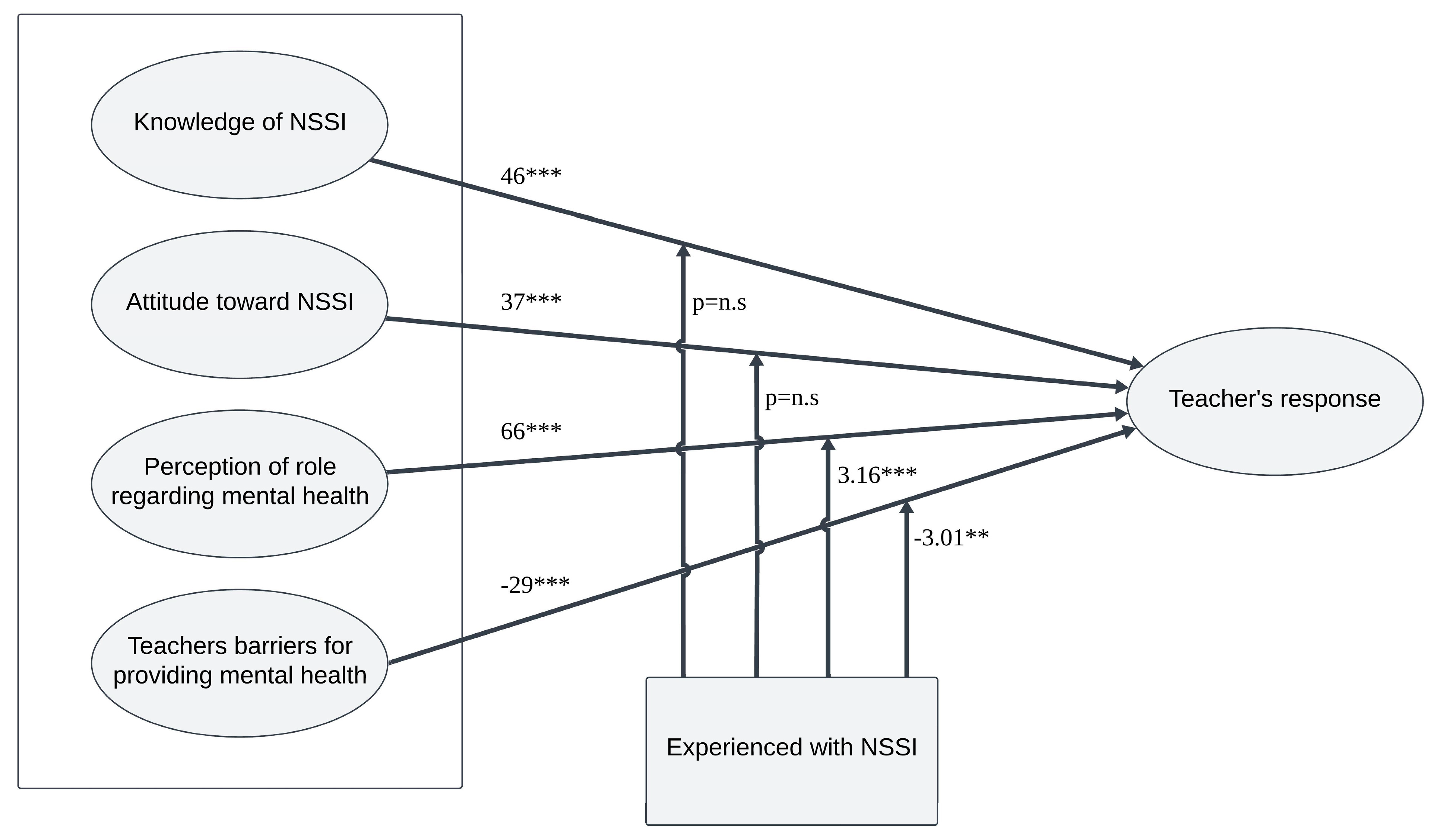

| Mean | SD | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Knowledge | 3.68 | 0.78 | 1–5 | - | ||||

| 2. Attitudes | 3.75 | 0.60 | 1–5 | 0.12 | - | |||

| 3. Perception of Role | 3.74 | 0.61 | 1–5 | 0.28 *** | 0.32 *** | - | ||

| 4. Barriers | 3.48 | 0.71 | 1–5 | −0.12 | −0.20 ** | −0.31 *** | - | |

| 5. Teacher’s Response | 2.99 | 0.43 | 1–5 | 0.46 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.66 *** | −0.29 *** | - |

| B | SE | β | t | R2 | F Model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Education type | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 1.78 | 0.09 | 10.43 *** |

| Seniority | 0.27 | 0.06 | 0.30 | 4.44 *** | ||

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Education type | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.55 | 40.09 *** |

| Seniority | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.47 | ||

| Knowledge | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.28 | 5.61 *** | ||

| Attitude | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 3.03 ** | ||

| Perception of Role | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.50 | 8.98 *** | ||

| Barriers | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.06 | −1.29 | ||

| Coeff | SE | t | LLCI | ULCI | R2 | F Model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

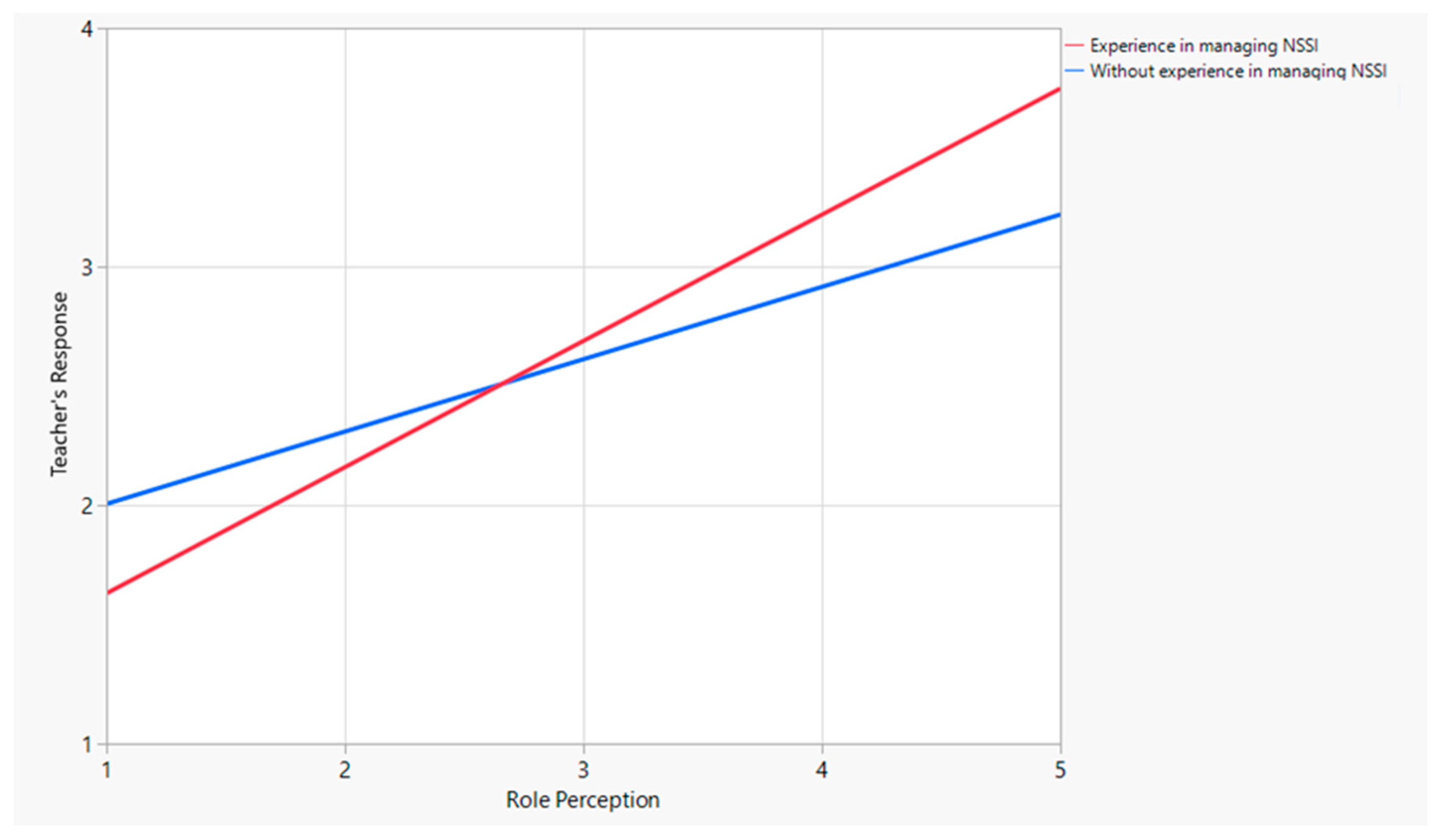

| Role Perception | 0.30 | 0.05 | 5.64 *** | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.53 | 75.02 *** |

| Experienced with NSSI | −0.60 | 0.26 | −2.24 * | −1.13 | −0.07 | ||

| Perception of Role * Experienced with NSSI | 0.22 | 0.07 | 3.16 ** | 0.08 | 0.36 |

| Coeff | SE | t | LLCI | ULCI | R2 | F Model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

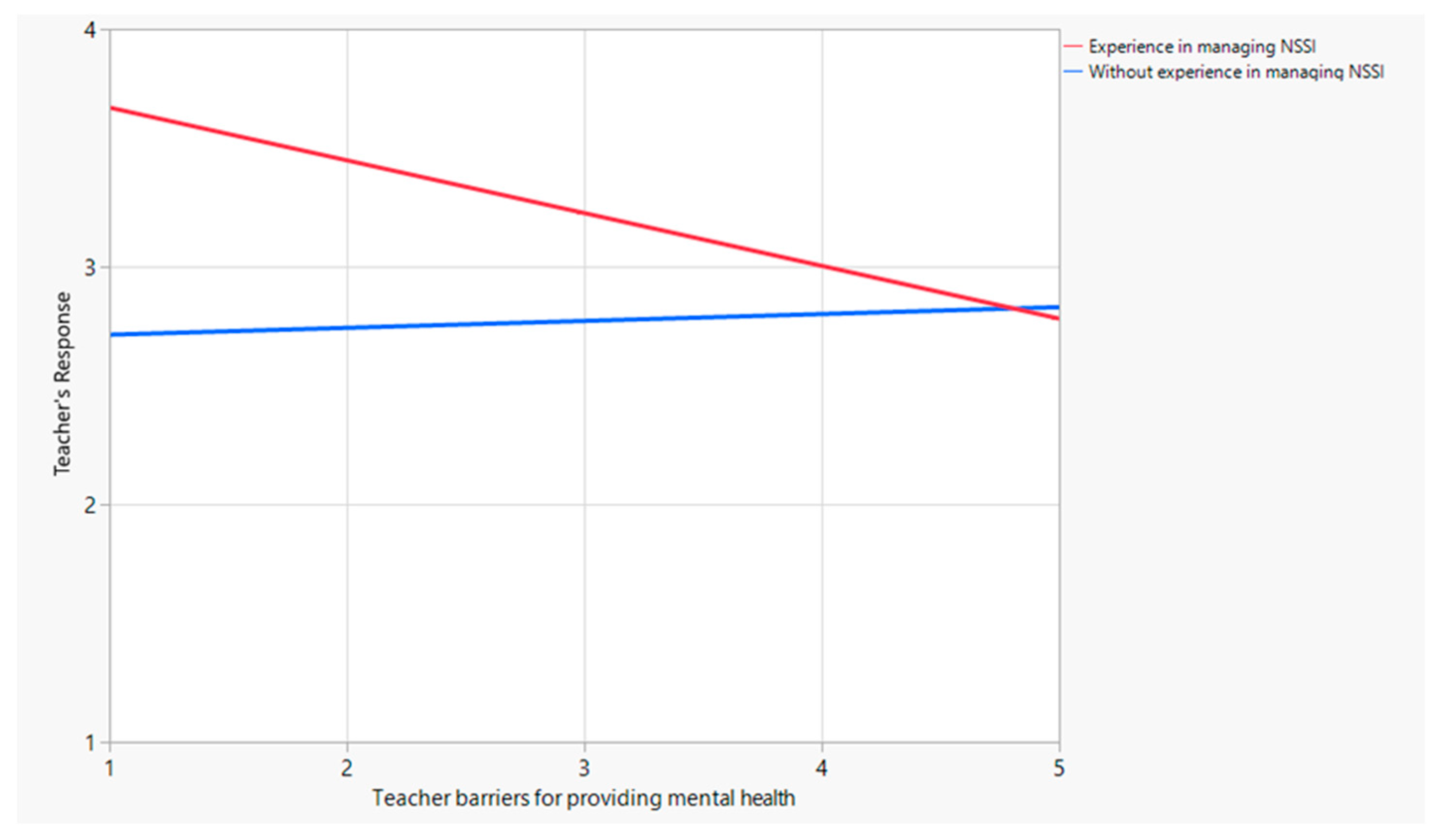

| Barriers | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.41 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 21.75 *** |

| Experienced with NSSI | 1.20 | 0.30 | 4.02 *** | 0.61 | 1.79 | ||

| Barriers * Experienced with NSSI | −0.25 | 0.08 | −3.01 ** | −0.41 | −0.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Levkovich, I.; Stregolev, B. Non-Suicidal Self-Injury among Adolescents: Effect of Knowledge, Attitudes, Role Perceptions, and Barriers in Mental Health Care on Teachers’ Responses. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 617. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070617

Levkovich I, Stregolev B. Non-Suicidal Self-Injury among Adolescents: Effect of Knowledge, Attitudes, Role Perceptions, and Barriers in Mental Health Care on Teachers’ Responses. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(7):617. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070617

Chicago/Turabian StyleLevkovich, Inbar, and Batel Stregolev. 2024. "Non-Suicidal Self-Injury among Adolescents: Effect of Knowledge, Attitudes, Role Perceptions, and Barriers in Mental Health Care on Teachers’ Responses" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 7: 617. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070617

APA StyleLevkovich, I., & Stregolev, B. (2024). Non-Suicidal Self-Injury among Adolescents: Effect of Knowledge, Attitudes, Role Perceptions, and Barriers in Mental Health Care on Teachers’ Responses. Behavioral Sciences, 14(7), 617. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070617