Abstract

Conventional wisdom posits that smog suppresses outdoor activity while shifting peoples’ activities indoors. Using anonymized Mobile Phone Data Provider Records fused with Point-of-Interest (POI) data sourced from the Gaode (Amap) open database for Beijing (2–22 February 2015), we test this substitution hypothesis at an hourly resolution across 12 POI-defined activity categories. We estimate the adjusted population density (APD) from mobile phone data via usage-bias calibration, interpolate city-wide AQI (Air Quality Index) and PM2.5 fields, and identify associations with a two-way fixed-effects design (Voronoi polygon (VP), day × hour model. We also handle time-invariant POI activities, while factoring in weather and day types. We find a dual suppression of both outdoor and indoor physical activities: worsening air quality is associated with lower participation in most outdoor and indoor activities. Effects are heterogeneous across categories and hours; shopping shows all-day negative marginal effects, whereas a few categories (e.g., sightseeing) display positive correlations in select afternoon hours consistent with congestion-avoidance rather than health-driven indoor substitution. Quantitatively, a 100-point AQI increase is associated with an order of 1–5 persons/km2 decline at peak hours for most activities. A Comprehensive Impact Index (CII) summarizes the spatial heterogeneity across the city. POI venue operators should anticipate city-wide activity reduction both indoors and outdoors under heavy pollution, rather than plan solely for outdoor-to-indoor activity shifts.

1. Introduction

Air pollution, particularly in developing countries, threatens the sustainability of urbanisation [1]. Elevated concentrations of pollutants, such as a higher air quality index (AQI) readings or fine particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter < 2.5 µm (PM2.5), have been shown to affect public health [2,3,4], cognitive function [5,6,7], labour productivity [8,9], educational outcomes later in life [10], and even subjective well-being [11].

Accurate, timely feedback on physical activity behaviour (PAB) and lifestyle is crucial for health promotion. Both exposure to polluted air and insufficient physical activity are major risk factors for noncommunicable diseases [12]. Prolonged exposure to air pollution increases the risks of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, type 2 diabetes, various cancers, and premature mortality [13,14], whereas engaging in physical activity yields immediate benefits that effectively reduce these risks [15,16].

The relationship between air pollution and physical activity behaviour is more complex than traditionally expected. Because air pollution can have substantial physiological and psychological effects on urban residents, it has often been assumed that deteriorating air quality will discourage outdoor activities and lead people to substitute them with indoor activities [17,18]. However, empirical evidence on this “indoor substitution” hypothesis is mixed: some studies document partial shifts from outdoor to indoor activities, whereas others find reductions in overall physical activity even when indoor options are available.

Traditional research on the relationship between air pollution and physical activity behaviour has relied predominantly on survey-based data sources, such as time-use surveys, health questionnaires, and retrospective self-reports. These approaches provide valuable individual-level information and have been instrumental in establishing long-run associations between pollution exposure and activity patterns. However, survey data are typically limited by coarse temporal resolution, recall bias, and infrequent sampling intervals, making them poorly suited to capturing short-term, hour-by-hour behavioural responses to rapidly fluctuating air quality. Moreover, self-reported measures may underrepresent spontaneous activity suppression or avoidance behaviour during pollution episodes, especially in dense urban environments.

To overcome the limitations of intermittent survey data in capturing these swift behavioural shifts, geolocated Big Data have become an important resource for analysing urban activity dynamics. Specifically, mobile phone CDRs and POI datasets function as primary sources that exhibit the classic “three-V” characteristics of Big Data—volume, velocity, and variety—because they capture large-scale, high-frequency, and semantically diverse information anchored to specific geographic locations. Unlike traditional self-reported surveys, these data sources offer the advantages of passive sensing, objective recording, and high spatiotemporal continuity. Their geospatial nature enables fine-grained inference of population presence and activity intensity, offering a strong complement to conventional survey-based approaches.

In this study, we analyse fine-grained, hourly behavioural data of Beijing residents to investigate the association between air pollution and multiple types of human physical activity. Specifically, using anonymised Call Detail Record (CDR) data combined with Point of Interest (POI) information, we employ a Fixed Effect Model to evaluate the spatiotemporal impact of air pollution on different categories of PABs. This approach allows us to capture changes in residents’ activity patterns across different areas and time periods in Beijing, and to quantitatively assess how fluctuations in air quality affect various activities. It also allows us to address an important research gap, as prior studies have rarely examined multiple POI-resolved activity categories simultaneously at an hourly resolution, leaving cross-category responses of behaviours to pollution largely uncharacterised.

Contrary to this simple “indoor substitution” view, our results indicate a dualsuppression: as air quality worsens, participation declines across most outdoor and indoor activities. Limited hour-specific positive correlations (e.g., sightseeing in some afternoons) appear consistent with congestion-avoidance or scheduling effects—not with a general outdoor-to-indoor substitution. In this sense, we provide a direct behavioural answer to the open question of whether urban residents respond to pollution primarily by substituting locations or by reducing overall activity levels.

From a psychosocial perspective, dual suppression may reflect heightened risk perception, negative affect, effort-avoidance under perceived hazard, and social learning [19,20,21]. These are plausible mechanisms, not causal claims, given our observational design.

Building on this debate, we explicitly ask two research questions. First, does worsening air pollution lead mainly to a simple outdoor-to-indoor substitution in PAB, or to a different behavioural pattern such as dual suppression? Second, how do these behavioural responses vary across activity categories (POIs) and across hours of the day within the city? Answering these questions clarifies the structure of behavioural responses to pollution and motivates our empirical design.

To address these questions, we (i) analyse multiple activity categories concurrently to compare hour-specific marginal effects; (ii) estimate absolute APD via CDR calibration to mitigate phone-usage bias; and (iii) map city-wide heterogeneity via a CII. This combination of hourly CDR calibration with POI-resolved FE modelling provides a level of behavioural resolution that is uncommon in earlier air pollution PAB studies. The remainder is organised as follows: Section 2 reviews related literature; Section 3 defines PABs and data; Section 4 details the fixed-effects identification and CII; Section 5 reports results; and Section 6 presents the conclusions and limitations of the study.

2. Related Work

A substantial body of environmental-health research has shown that outdoor air pollution can readily infiltrate indoor spaces through ventilation systems, building envelopes, and human movement, leading to indoor pollutant concentrations that partially track ambient levels. This indoor–outdoor coupling has been documented across diverse urban environments, including homes, schools, and workplaces [22]. Evidence from transport and commuting contexts also suggests that individuals may experience elevated exposure during routine daily activities [23,24]. These findings highlight that indoor settings are not insulated from ambient pollution, providing an important foundation for understanding why both indoor and outdoor PAB may respond to changing air quality.

Early work established that poor air quality suppresses outdoor activity [17]. Subsequent studies show that outdoor pollution penetrates indoors and can directly affect physical activity behaviours (PABs) [21]; others document behavioural shifts such as staying indoors on polluted days [18]. Overall, both outdoor and indoor contexts can be affected, but whether indoor activity compensates for outdoor losses remains unsettled, highlighting a central behavioural debate between substitution (shifting time to indoor or alternative activities) and suppression (reductions in overall activity).

To synthesise the behavioural-response literature, a recent review [25] shows that most studies examine PM2.5/PM10, O3, and NOx, with a few using composite air quality measures. Across designs, worse air quality is generally associated with lower overall physical activity; for example, a one-unit (µg/m3) increase in ambient PM2.5 correlates with a 1.1% reduction among adults (survey estimates summarised in [25]). Follow-up evidence from China similarly links higher PM2.5 to shorter outdoor leisure/transport activity [26]. Importantly, evidence on indoor or sedentary behaviours is mixed: some studies document increased sedentary time or sleep on more polluted days [27,28], consistent with partial substitution into indoor or low-intensity activities, whereas others find little change in such behaviours, leaving open whether indoor time increases enough to offset outdoor declines.

Survey and observational studies offer complementary perspectives, Wells et al. [29] analysed the survey data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in the U.S., then their conclusion suggests that individuals afflicted with respiratory conditions are more prone to adjust activities in response to inferior air quality. Nevertheless, health and public health professionals could amplify their efforts to motivate those vulnerable to the impacts of air pollution to implement changes that would diminish their exposure to such pollutants. Hu et al. [30] used outdoor exercise data spanning 160 days collected from 153 users of an exercise app, in Tulipsport in China (http://www.tulipsport.com/). They utilise multivariate models and find that the users were less likely to participate in outdoor running, biking, and walking as levels of air pollution increased. However, there is no difference in terms of average distance and duration of exercise across different air pollution categories. Zhao et al. [31] carried out a survey involving 307 cyclists on days with varying air quality levels, gauged by PM2.5 concentrations, in 2015. The results indicated that amidst pollution, those who continued cycling were predominantly male, over 30 years of age, of lower income, or those who traversed short distances. Specifically, female cyclists exhibited a higher propensity to transition from cycling to public transit compared to their male counterparts. Individuals with medium and high incomes demonstrated a higher likelihood of switching to car use compared to those with lower incomes. Park-use analysis combining social media and counts showed particulate pollution depresses peak visitation and recreational services [32]. Together, these survey and observational designs reveal both suppression of outdoor exercise and cycling and substitution across travel modes (from cycling to public transit or car use), yet they do not directly observe whether reduced outdoor activity is compensated by increases in indoor or sedentary behaviours.

Within survey-based research, several related studies provide quantification analysis of behavioural responses to pollution. Wen et al. [33] analysed the data from a Behavioural Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) in 2005 and found that a 10-unit (µg/m3) increase in-state annual average PM2.5 concentration was found to be associated with a 16% decrease in the odds of undertaking physical activity. Based on using multilevel logistic regression on the dataset from the same platform, BRFSS, during 2003–2011, to examine the effect of ambient PM2.5 air pollution on participants’ leisure-time physical inactivity, An et al. [34] find that a one unit (µg/m3) increase in county monthly average PM2.5 concentration was found to be associated with a decrease in the odds of physical activity by 0.46% (95% confidence interval = 0.34%–0.59%). There are also some studies with absolute quantification results in this field, e.g., the study in [27] using survey data in Beijing, China, indicates that an increase in the ambient PM2.5 concentration by one standard deviation (36.5 µg/m3) was associated with a reduction in weekly total minutes of walking by 7.3, a reduction in weekly total minutes of vigorous PAB by 10.1, a reduction in daily average hours of sedentary behaviour by 0.06, but an increase in daily average hours of nighttime/daytime sleep by 1.07, highlighting a shift from active to restorative or passive behaviours rather than compensatory active indoor substitution. Yu et al. [28] conducted linear individual fixed-effect regression analyses to assess the effect of ambient PM2.5 concentration on physical activity-related health behaviours among survey participants in Beijing. The findings revealed that a surge in ambient PM2.5 concentration by 1 standard deviation (56.6 µg/m3) was linked with a reduction in weekly total walking hours by 4.69, a decrease in leisure-time Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) score by 71.16, and a decrease in the overall PASE score by 110.67. An increase in ambient PM2.5 concentration by one standard deviation was correlated with an escalation in daily average hours of nighttime/daytime sleep by 1.75, again suggesting substitution towards additional sleep rather than increased active indoor PAB. Taken together, these quantified survey results indicate sizeable suppression of outdoor and vigorous activity, partial substitution into sleep, and limited evidence for full indoor compensation.

In terms of methodologies to model the relationship between air pollution and PAB, the issue of omitted variable bias poses a significant statistical challenge in non-experimental research (a research approach that lacks manipulation of an independent variable, control of extraneous variables through random assignment, or both). Fixed Effects (FE) models with panel data were designed to address the issue of omitted variable bias in non-experimental research [35]. Consequently, FE models can be utilised to identify the relationship between PABs and air pollution. In this context, the FE model is an estimation technique applied to panel data, enabling the consideration of time-invariant unobserved individual characteristics. That is, additional factors such as exclusive offers at varying times of day, among others, can correlate with the observed independent variables (AQI or PM2.5) [36]. These panel-data strategies complement the above measurement approaches and underpin our own two-way fixed-effects specification.

Beyond self-reported surveys of physical activity, for dining-out, Gao et al. [37] and Zheng et al. [38] use review data (e.g., https://www.dianping.com/) and find air pollution reduces frequency and satisfaction, with urban–suburban differences. However, such data are not fully representative or objective (selection into reviewing) and may suffer from omitted-variable endogeneity [39]. In contrast, CDRs provide objective, high-frequency coverage of visits across venues, better suited for population-level activity inference and central to our measurement approach.

Relative to our prior work [40], we (1) use the full CDR corpus rather than a sample; (2) refine and broaden POI-based activity taxonomy to 12 classes at hourly resolution; (3) calibrate APD from CDRs to mitigate time-of-day usage bias and produce absolute levels; and (4) augment TWFE with POI density and AQ×POI interactions to quantify category-specific marginal effects with improved robustness, thereby enabling a city-wide, category-specific test of substitution versus suppression.

In summary, prior research consistently shows that air pollution tends to discourage outdoor physical activity. However, whether people compensate by increasing indoor or alternative activities remains unclear: some evidence points to partial substitution, while other work suggests that overall activity may decline without full compensation. Addressing this gap, we explicitly revisit the “indoor substitution” hypothesis and contrast it with a “dual suppression” scenario in which both indoor and outdoor activities fall. Our study builds on previous work by examining a broad array of PABs (encompassing both indoor and outdoor activities) and their temporal dynamics under varying air quality. By doing so, we provide a more comprehensive, absolute quantification of pollution’s impact on human behaviour over time and situate our empirical findings of dual suppression within the broader substitution-versus-suppression debate. Recent work has also begun to incorporate geolocated Big Data—such as mobile phone CDRs, GPS traces, smart-card transactions, and social-media check-ins—to examine how pollution shapes urban mobility patterns [41,42,43], although most such studies analyse coarse origin–destination flows rather than POI-specific activity behaviours. Our study extends this emerging line of research by providing POI-resolved, hourly behavioural responses to pollution at a city-wide scale.

3. PAB Definition, Data and Pre-Processing

This section defines the PAB taxonomy used in this study and introduces the datasets and preprocessing steps: CDRs (for APD), air pollution (AQI, PM2.5), weather (hourly), POIs (activity mapping), and ancillary geometry (Voronoi Polygons).

3.1. The Definition of PAB

When there is serious haze (due to very bad air pollution), multiple human PABs may be influenced [27,34,44,45], where it is rare for the spatiotemporal impacts of air quality on multiple PABs to be qualitatively and quantitatively estimated [40]. By combining urban computing [46] with GIS (Geographical Information Science) and spatial statistical analysis, these impacts can help provide travel advice where haze affects human activities. Haze can facilitate authorities to warn citizens about unnecessary travel, provide a decision-making basis for urban managers, and reveal the impact of haze on human beings. The impact of health providers’ technical support has an important practical significance of social decision-making and the promotion of citizens’ disaster awareness.

As per the 2018 National Time Use Survey Bulletin of China, which was carried out by the National Bureau of Statistics of China (https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202302/t20230203_1900224.html, accessed on 15 November 2025), the average time for the main activities of residents has been shown in Table 1. Because the PAB can be captured by the observed human visits at a specific POI [40], e.g., somebody who visited a restaurant in the morning for 1 h, it can be inferred that he or she had breakfast at that time and place. Hence, PAB types can be classified into three categories according to whether and how they can be represented by the observed human visits at a relevant POI: (1), the PAB can be mostly linked to relevant specific POI(s), which is defined as POI-based PAB (PB-PAB). (2), the PAB can be partly linked to relevant specific POI(s), defined as Partly PB-PAB (PPB-PAB). (3), the PAB cannot or is hardly linked to relevant specific POI(s), defined as Not PB-PAB (NPB-PAB). In Table 1, the PB-PAB category accounts for about 56.11%, while the PPB-PAB category accounts for about 10.21% but whose total accounts for over 65% per day [2]. Although Table 1 reports nine broad time-use categories from the national survey, the twelve PAB sub-types analysed in this study represent only those activities that can be reliably linked to specific POI types and therefore observed via the CDR–POI framework. Consequently, the analytical taxonomy is a refined, POI-based subset of the broader survey categories rather than a direct one-to-one correspondence.

Table 1.

Residents’ average time of PB-PAB and PPB-PAB in 2018 China.

According to the accessible POI dataset (see Section 3.5), there are 17 types of POIs—e.g., types of outdoor leisure sites, including the botanical gardens, parks, squares, etc.—including different types of accommodation such as private homes, hotels, etc. However, not all the types of POIs can correspond to a specific PPB-PAB or PB-PAB. Sometimes multiple PABs can happen at a single POI, for example, at home, people can sleep, watch TV, read books, and do housework. Some PABs may not be easily distinguishable via their POI location alone, so many-to-many correspondences can cause biases in the study. Further, because the study period focuses on daytime, some PABs that mostly happen at nighttime, such as sleeping, are ignored in this study. Meanwhile, there are some PABs that are not shown to be impacted by air quality directly, e.g., air pollution impacts less the PAB of drivers who refuel their cars at gas stations, and so these are also not considered in this study.

Thus, the selection of the PABs that are studied in this study is based on the following rules. (1), The PAB should be PB-PAB or PPB-PAB. (2), The corresponding POIs data can be accessed. (3), The PAB and POI have a relatively simple correspondence, preferably one-to-one. (4), The PAB happens during the study period (daytime). (5), The PABs might be impacted by air pollution directly. Based on the above selection rules, in this study, five types of PB-PAB or PPB-PAB are considered to be of interest to be studied, including 12 sub-types of PAB. The first type of PAB is eating out, which includes two sub-types of eating out for meals in restaurants (defined as PAB-1) or for (smaller food) snacks, e.g., for a coffee and cake (defined as PAB-2). The second type of PAB is outdoor leisure, including going to the park (defined as PAB-3) and sightseeing (defined as PAB-4). The third one is fitness, including indoor sport or fitness (PAB-5), and outdoor sport or fitness (PAB-6). The transportation type of PAB consists of travel by bus (PAB-7), by subway (PAB-8), and by private car or taxi (PAB-9). The remaining types of PAB in this study focus on education and science services (PAB-10), e.g., going to the library or museum, healthcare services (PAB-11), and shopping (PAB-12). The corresponding POI selection will be introduced in Section 3.5.

3.2. Call Detail Record (CDR)

This study utilised an anonymous CDR dataset from China Mobile of Beijing (https://www.chinamobileltd.com/en/global/home.php, accessed on 15 November 2025), spanning from Monday, 2 February to Sunday, 22 February 2015 (3 weeks). The dataset encompasses over 4.8 billion records of more than 300 million users per day, incorporating the 2015 Spring Festival Holiday from 18th to 22nd February. Each hourly CDR file in CSV format averages 2 Gigabytes in size. CDRs comprise the International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI) number, a unique international code for every Subscriber Identity Module (SIM) card that identifies users on the network, a timestamp that documents interactive communication events, and Cell Identity (CI) that corresponds to the base station location (Table 2).

Table 2.

Recorded data structure.

The dataset was collected from 51,216 mobile base stations, and the location attribute was recorded using the Global System for Mobile communications (GSM) engineering parameters (Table 3). However, due to the proximity of some base stations, their identified latitude and longitude were identical. To address this, we combined “collocated” base stations, reducing their number by approximately from 51,216 to 17,446. The Voronoi Polygon (VP) approximates the coverage area of each mobile base station [47] that surrounds it. When a phone initiates a call or sends a text message, its location is determined by its connection to the specific mobile base station within range.

Table 3.

The inner structure of GSM engineering parameters.

The IMSI number, CI, and Timestamp collectively ascertain the CI of each user for every record, and the corresponding base station location is utilised as the user’s location. In this study, the precision of the Timestamp in CDRs is defined as the temporal resolution of recording, which is 1 s in this dataset. CDRs are housed in a Comma-Separated Values (CSV) file, with one file for each hour (3600 s).

CDRs record personal information, including the location and contact network of mobile phone users, which could pose a significant threat to their privacy. The movements of an individual can reveal their points of interest [48], predict their past, present, and future locations [49], or facilitate de-anonymisation attacks [50]. Therefore, telecom companies only allow access to CDR data through specific licences and agreements that restrict the use of such data for private or commercial purposes [51]. However, certain big telecom companies in China, such as China Mobile Communications, have released certain datasets for research purposes only, subject to specific licences and agreements. The permission to use the CDR data in this study was based on such an agreement, where the records’ codes, such as IMSI, are encrypted. Thus, anonymous data of this kind avoids the privacy issue. In addition, all analyses are conducted on hourly, VP-level aggregated counts of unique IMSIs, rather than individual trajectories, which further prevents re-identification and provides an additional layer of privacy protection inherent in the study design.

Furthermore, due to the considerations outlined in Section 3.3, the emphasis is placed on analysing the relationship between individuals’ PAB and air quality from sunrise (approximately 6:30 a.m.) to sunset (roughly 5:30 p.m.), and where the analysis of the corresponding relationship at nighttime is omitted. To distinguish the impact of air quality on multiple PABs in a day, the definition concerning daytime has been rounded to be from 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. 12 h, then divided into the hourly unit, e.g., from 6:00 a.m. to 7:00 a.m. is defined as the first time period (TP), and so on.

Then, the unique IMSI within each VP in each TP is computed. Here, two strategies to determine the user’s location (concerning a VP) have been proposed in each TP because a user can move between different locations and be recognised at multiple VPs. First, in terms of a user with a unique IMSI, in a specific TP, the highest records of CI correspond to a base station area (VP), the user is determined to be at the VP in this TP because he or she might stay in the area most of the time. For example, one user calls 50 times in a TP at the first VP but calls only 5 times in the same TP at the second VP, and then the first TP is regarded as the location determined for the user. However, this strategy ignores the stay time effect, e.g., if the user calls 50 times within 20 min at the TP, but in the remaining 40 min, he or she only calls 5 times, then the determined location of the user should be the second VP, not the first one. Thus, another strategy has been proposed. That is, based on strategy one, computing the time interval between every two calls in the same CI, then obtaining the largest interval of the CI, then comparing all the intervals, the CI with the longest time interval would be regarded as the CI determined (concerning the VP). For example, if the largest interval is 40 min in the second VP (computed from the 5 calls), but the largest interval is 20 min in the first VP (computed from the 50 calls), the user would be determined to be at the second VP in that TP. These two strategies are defined as the Strategy of IMSI Location Determination 1 and 2 (SILD1 and SILD2).

Because our window is 06:00–18:00, uneven phone use and carrier market share can undercount daytime presence. Following [52,53], we scale hourly unique-IMSI counts by the daily ratio (unique mobile users)/(actual population) to obtain an Adjusted Population Number (APN); dividing APN by VP area yields APD.

3.3. Air Pollution

In 2013, the Chinese Ministry of Environmental Protection (CMEP) established its national air quality monitoring centre. This ministry reports real-time hourly concentrations of major air pollutants, such as PM2.5, PM10, SO2, O3, NO2 and CO, at approximately 1000 monitoring stations throughout China in 2015, of which 35 are in Beijing. Among these six contaminants, the CMEP identifies a city’s “primary pollutant” as the pollutant contributing the most to the degradation of that city’s air quality on an hourly basis. The CMEP also offers a composite measure of air quality, AQI, which is calculated on an hourly basis contingent on the primary pollutant. In this study, the hourly AQI values are taken directly from the 35 monitoring stations in Beijing, and these station-level observations serve as the input for subsequent spatial interpolation.

To obtain the spatiotemporal values of pollutant concentrations and AQI, we employ the Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) method, which is a widely used spatial interpolation algorithm [54] that has been implemented in previous research studies [55,56,57]. IDW has proven to be efficient in interpolating surface pollutants like PM2.5, covering the entire study area of Beijing [58,59]. In our implementation, we set the IDW power parameter to 2 and, for each VP centroid, interpolate from up to the 12 nearest monitoring stations, which is a common choice for urban-scale air quality studies. We chose IDW rather than kriging because, given the relatively dense monitoring network in Beijing and the large number of hourly surfaces to be generated, this specification offers a good compromise between interpolation accuracy and computational efficiency. After processing, we compute and map hourly distributions of pollutants covering the entire city of Beijing.

To investigate the impact of air pollution on human activity, this study focuses on several criteria for pollutants, particularly PM2.5, which has been widely recognised as a central pollutant due to its association with increased mortality and morbidity risk in previous research studies [4,11,60,61,62,63,64,65].

Table 4 provides information on the concentrations of key air pollutants (PM2.5, PM10, SO2, O3, NO2, and ) and their correlations in Beijing. We will then discuss how to interpret our model based on this information.

Table 4.

Air pollution statistics based on Beijing data.

Recent scientific investigations have established the pervasive impact of particulate matter on air pollution severity across Chinese urban spaces, with Beijing exhibiting the most significant pollution levels for PM2.5 and PM10 [66,67]. The Clean Air Alliance of China Clean Air Management Report in 2016 (CAAC Clean Air Management Report. Bulletin on Clean Air Alliance of China in 2016, available at http://www.cleanairchina.org/file/loadFile/145.html, accessed on 15 November 2025), corroborates this, noting PM2.5 as the primary pollutant for over 64% of the time during the study period, despite compliance with China’s National Ambient Air Quality Standard. Emissions of O3 and NO2 marginally breached the standard, accounting for 1.79% and 15.48% of the hours, respectively. PM10 still represented a substantial polluting factor, constituting 18.65% of the hours, despite the reduction in its occurrence relative to PM2.5.

Airborne particulate matter, with high concentrations of SO2, is perceptible due to its odour and coloured sulphides accompanying industrial smoke emissions. Conversely, ground-level O3 and CO, being both invisible and odourless, are less discernible [68,69]. Although NO2 consistently maintained low concentration levels, its reaction with organic compounds could escalate other pollutants such as O3 and PM2.5, thus indirectly influencing perception.

PM2.5 demonstrated strong correlation with PM10, AQI, and NO2, except for consistently low SO2 and CO, as indicated in Table 4. The negative correlation between O3 and PM2.5 was also noteworthy. Considering PM2.5 as the dominant pollutant and AQI as the global air quality index during the study period, both were selected to analyse their influence on people’s activities.

Therefore, the average AQI and PM2.5 values were calculated for 12 hourly time points per day throughout the study period for each variable point.

3.4. Weather Conditions

Hourly weather is from NOAA/NCDC (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/), using the Beijing Capital International Airport station (NOAA/NCDC station ID ZBAA) as a representative site for the city. Because POIs are concentrated in Beijing’s urban core, the study period (21 days) had no rain/snow events, and our controls are temperature, wind, and cloud cover, we use a representative station for the city; at this temporal scale, the spatial gradients are limited and unlikely to bias within-hour comparisons. As a simple robustness check, we repeated the FE regressions with hourly weather from a second Beijing-area station and obtained very similar coefficients, indicating that the choice of representative station does not materially affect our findings.

3.5. POI

A Point of Interest (POI) represents a geographically specific entity that garners interest or serves a useful purpose for a significant group of individuals [70]. Given that POI density has a positive correlation with the density of human activity, it can be construed as a continuous surface mirroring the intensity of human activity in a region. In this context, the terrain corresponding to an urban centre could be likened to a mountaintop [71].

A third-party platform, such as Google Map (https://maps.google.com), Gaode Map v5.2, publishes POI information, e.g., accurate number of POIs and location [70]. Such companies use four main ways to generate POI data: (1) data extraction from web sources; (2) user-generated; (3) government directories; (4) manual verification.

In this study, the open-source POI dataset comes from Gaode Map (AutoNavi Limited Company, Beijing, China) (https://mobile.amap.com/) and was downloaded on the platform of Peking University Open Research Data [72]. It covers the total data up to 2017, and the whole of Beijing city has a total of more than 1.4 million POIs. In a GIS, a POI can be a house, a shop, a mailbox, a bus stop, etc. This data contains eight core fields, including POI name, type, address, location, province name, city name, etc.

The POI dataset used in this study was published in cooperation with the State Information Centre of China (https://doi.org/10.18170/DVN/WSXCNM, accessed on 15 November 2025), which can provide more authoritative information. There are plenty of studies that have used the open POI data published by AutoNavi Limited Company, e.g., to precisely identify urban functional areas [73,74,75], to evaluate the economic and society effect (e.g., poverty, life convenience, house price) [76,77,78], etc.

Each type including the sub-type of PAB is associated with a POI type. The correspondence is shown in Table 5. In order to compare the impact of the air quality on different types of PAB, the absolute POI number in an area cannot reflect the relative relationship between each two POI types, thus, the proportion of a specific type of POI number of all POI number in a VP is calculated. For each POI type, the POI proportion in every VP has been counted at 12 TPs over the study period (from 2 to 22 February 2015).

Table 5.

The correspondence of PAB and POI.

3.6. Technical Parameters

Spatial data processing, including the construction of Voronoi Polygons, IDW interpolation, and mapping, was carried out in ArcGIS (version 10.4). Fixed-effect regressions and the computation of marginal effects were implemented in Stata (version 16), using heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors clustered at the VP level for all specifications.

4. Method

In this section, to detect the impact of air quality on human activity behaviours, Fixed Effect (FE) models are used to build the regression equations between the AQI/PM2.5 and the PAB that are reflected by observing (human) visits (APD) at POIs, i.e., parks and restaurants, also with necessary supplementary variables such as weather conditions. According to the results of the FE model, first, the qualified impact of air pollution in different time periods for each type of PAB can be estimated, to illustrate if and how the PABs are impacted by the air pollution varying during daytime. Then, by fixing the POI effect, the impact of air quality on multiple types of PAB can be compared quantitatively as well. This study proposes an index computation method to show the summarised impact over the study area, which can quantitatively give an intuitive map. In terms of the prediction work, because air pollutant prediction and PDD have already been widely studied, the impact of the distribution transform before a prediction and the need for using a spatiotemporal deep learning model still needs to be evaluated.

4.1. Fixed Effects (FE) Model

There is a range of methods that can be used to correlate the effect of changes in the environment, such as air quality, on PABs, for example, single linear regression, quantile regression and a FE regression for panel structured data. FE models are a class of statistical models in which the levels (i.e., values) of independent variables are assumed to be fixed (i.e., constant), unless it changes in response to the levels of independent variables [79]. Models that work on the panel data structure can assist in managing any omitted variable bias due to any unobserved heterogeneity when this heterogeneity is constant over time [36]. And the main benefit of FE models is that the potential sources of biases in the estimations are limited in comparison to classical OLS models [80].

Although the FE model for panel data is now widely recognised as a powerful tool for longitudinal data analysis, limitations still exist and are rarely explored, e.g., low statistical power, time invariance, etc. [81]. First, when the analytic sample is essentially limited to variables and cases that change, the sample size is reduced, variation across cases is constrained, and statistical power is a cause for concern [82,83]. Reliable FE estimation requires “sufficient variability over time in the predictor variables” [83]; hence, FE models should be used with caution when there is little variation in the focal variables. However, in this study, the observation number in the FM models is the total number of VPs that contains at least one POI (for a specific PAB) multiplying the time (in days), which is at least = 22,533 (1073 is the VP number where at least one outdoor leisure site locates, which is the least number among all types of POI), and the PDD values of the observation during the Spring Festival contain a drastic variation, which can well overcome the first issue (stated above). Second, Allison [84] notes that FE methods are rarely useful for estimating the effects of variables that do not change over time. Even though now the simultaneous estimation of time-invariant variables is allowed, an important source of potential bias is retained because the estimates for time-invariant variables do not account for unobserved heterogeneity. The time-invariant variable in this study is mainly the POI percentage in a VP (Section 3.2), where the qualitative results are needed more than the quantitative ones in terms of the impact of POI percentage on human PABs. There are other limitations, such as measurement error, undefined variables, and unobserved heterogeneity. The proposers [81] highlight that “instead of discouraging the use of fixed-effect models, we encourage more thoughtful and discriminating applications of this rigorous and promising methodology”. Thus, according to classical experience, a rigorous experimental design and implementation can effectively alleviate these problems.

Because the datasets are structured as panel data in this study, which refers to data that tracks the same group of individuals in a period, which has both spatial dimensions and time dimensions, FE models are primarily utilised to discern the relationship between PABs and air quality. These models serve as estimation techniques used on panel data structures, enabling the consideration of time-invariant unobserved individual characteristics. These include, but are not limited to, other variables such as special offers at various times of the day, which can correlate with the observed independent variables (AQI or PM2.5) [35].

To estimate the impact of air quality on multiple PABs in Beijing, we fit the FE model shown in Equation (1) repeatedly on the different TPs, different air pollution indicators (AQI and PM2.5), and different types of POIs. The panel data constructs the individual dimension as the VP () where n is the number of VPs that contain at least one type of POI, while the time dimension is daily from 2 to 22 February 2015 ().

where and represent the adjusted population density and the air pollution indicator (AQI value and PM2.5 concentration) of the at , respectively. represents the POI proportion of the VP, while is the interaction term to observe the interaction effect between AQ and POI proportion. Because the number of POIs can indicate the development level of the area, in the equation, the POI density (), which is the quotient of the total POI number and the area of the VP, is controlled. , , and represent temperature, wind speed, and cloud cover rate (it only has a t index because the weather data is only from one monitoring station in Beijing, as all the POIs have the same weather values at the same time). Temperature squared () is used to examine the non-linear effect of the temperature on PABs [11]. Furthermore, because there is no rainfall or snowfall during the study period, the rain and snow factors are not included in this equation. and refer to the type of a day dummy variable to indicate the day as a weekday or weekend, or if a holiday. To control the time-invariant unobserved factors that vary across cities, we include the Fixed Effect . Note that unobserved factors are not classified; they are known unknowns and just grouped. The definitions of the variables are provided in Table 6. All FE specifications are estimated with heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors clustered at the VP level to allow for arbitrary serial correlation within each polygon over time.

Table 6.

Variable definitions.

The coefficients in Equation (1) can indicate the impact of the factors on the . Within them, the , , and with their p-values are the main concern. The coefficient of the interaction term can contribute to computing the marginal effect (ME) of the AQ and PP on , respectively, as shown below:

Equation (2) indicates that the impact of AP on is also influenced by , where the significant and mean that if the POI proportion is fixed as A, when increases by one unit, the will increase units. Similarly, in Equation (3), if is fixed as B, then increases by one percent, the will increase units under the significant conditions. Thus, according to the sign of the coefficient and the p-value of , , and , the qualitative and quantitative impact of air quality on multiple PABs would be computed.

Note that, because not all the types of POI exist in every VP when estimating the coefficient for different PAB, only the VPs that have at least one corresponding POI are kept, whereas the observation numbers in different FE models for different types of POI are different as well. For example, for the restaurant for meal POI, there are 9398 VPs having at least one POI, thus the observation number in this FE model is = 197,358.

4.2. Comprehensive Impact Index (CII)

With POI distributions treated as static over the study window, we summarise per-VP net sensitivity by a Comprehensive Impact Index (CII):

where is the actual proportion of POIs for activity n in the VP, and are estimated from hour-specific panels. aggregates category-wise at observed , producing 12 maps (one per hour).

The CII offers an intuitive, single-value summary of how the POI composition of each VP shapes its overall behavioural sensitivity to air pollution. By weighting category-specific marginal effects using the VP’s actual POI proportions, the index captures the structural exposure of different urban areas to pollution-induced activity change. This aggregation makes the CII especially useful for city-wide comparison and spatial visualisation of heterogeneous impact patterns.

5. Results and Discussion

We directly test the substitution hypothesis using hourly marginal effects across 12 POI-defined activities. Three findings emerge. (i) Most activities—outdoor and indoor—exhibit negative as AQI worsens (dual suppression). (ii) Effects are hour-specific: suppression peaks in the morning (≈08:00–11:00) for eating, fitness, healthcare, and shopping. (iii) A few categories (e.g., sightseeing) show positive correlations in select afternoon hours, consistent with congestion-avoidance rather than systematic indoor substitution. CII maps reveal pronounced spatial heterogeneity, with stronger negative effects in inner-city VPs during morning peaks.

5.1. Spatiotemporal People Density Distribution Description

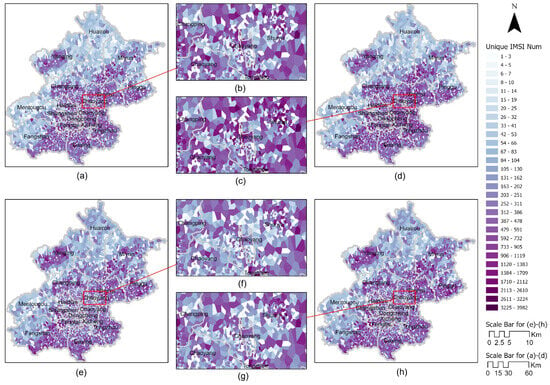

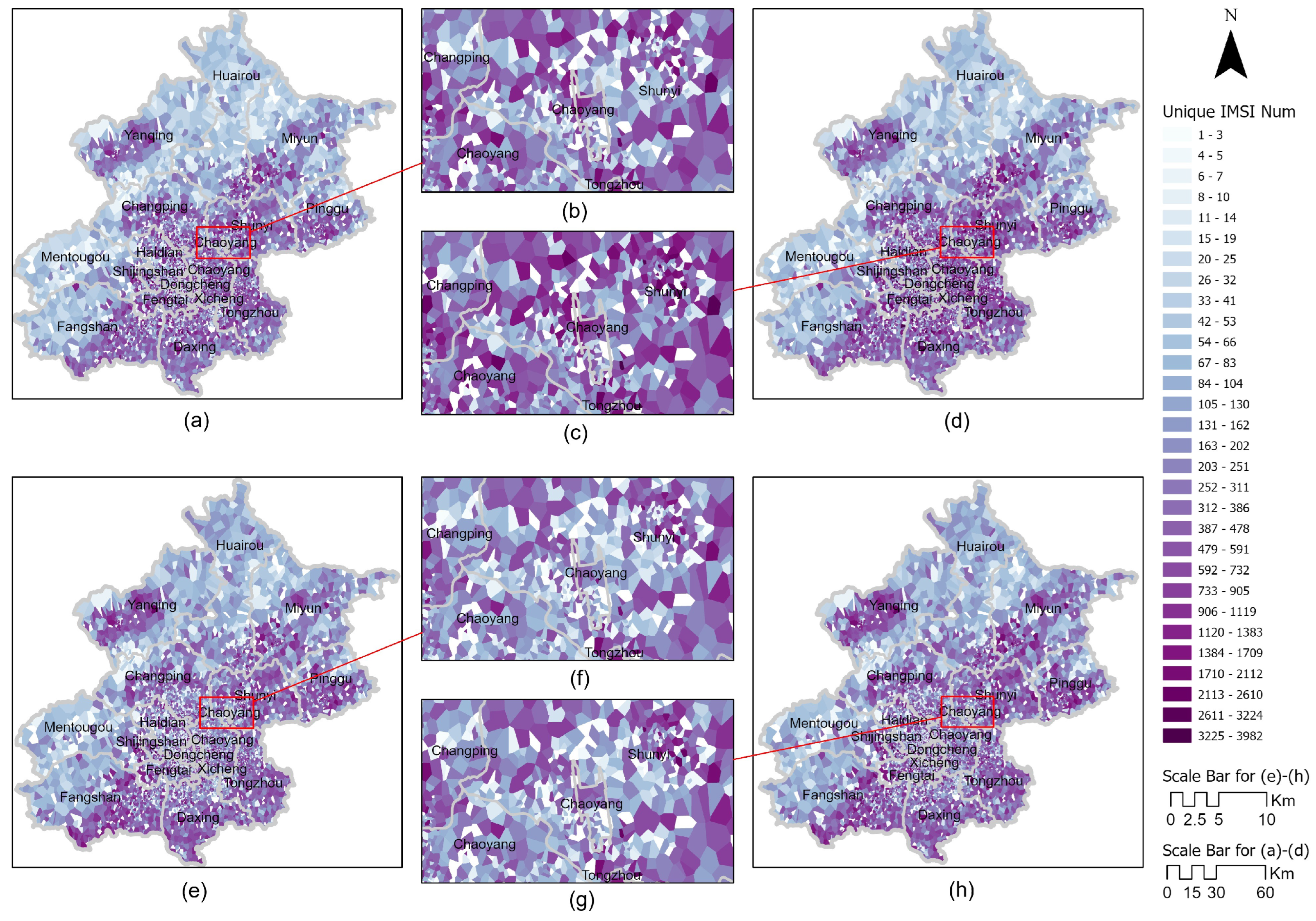

When considering the spatial scale of people density distribution based on Call Detail Records (CDRs) (Figure 1), urban areas such as Dongcheng and Xicheng Districts exhibit significantly higher population densities compared to suburban regions like Huairou and Yanqing Districts. This pattern essentially aligns with crowd aggregation characteristics, where the density gradually declines from the city centre towards the outskirts. On a temporal scale, people’s daily activities tend to be minimal early in the morning (e.g., 6:00 a.m. as depicted in Figure 1a,e), while population density intensifies in the same urban central locations during the afternoon (e.g., 6:00 p.m., illustrated in Figure 1b,f). From a comprehensive study period perspective, the population density during the Spring Festival period is lower than on usual working days. This is due to a significant number of people in Beijing, who originally migrated from other provinces, returning to their hometowns for the Spring Festival, a significant Chinese tradition. However, the daily pattern remains consistent, with a lower population density observed in the morning, which escalates in the afternoon.

Figure 1 displays population distributions, with panels (a–d) illustrating patterns across all of Beijing, and (e–h) focusing on a more localised inner area of Beijing for a detailed view. Snapshots at 6:00 a.m. on 2 February 2015 are presented in panels (a,e), while 6:00 p.m. distributions on the same day are depicted in panels (b,f). Similarly, panels (c,g) represent the distributions at 6:00 a.m. on 19 February 2015 (Spring Festival), and panels (d,h) present the distributions at 6:00 p.m. on the same day.

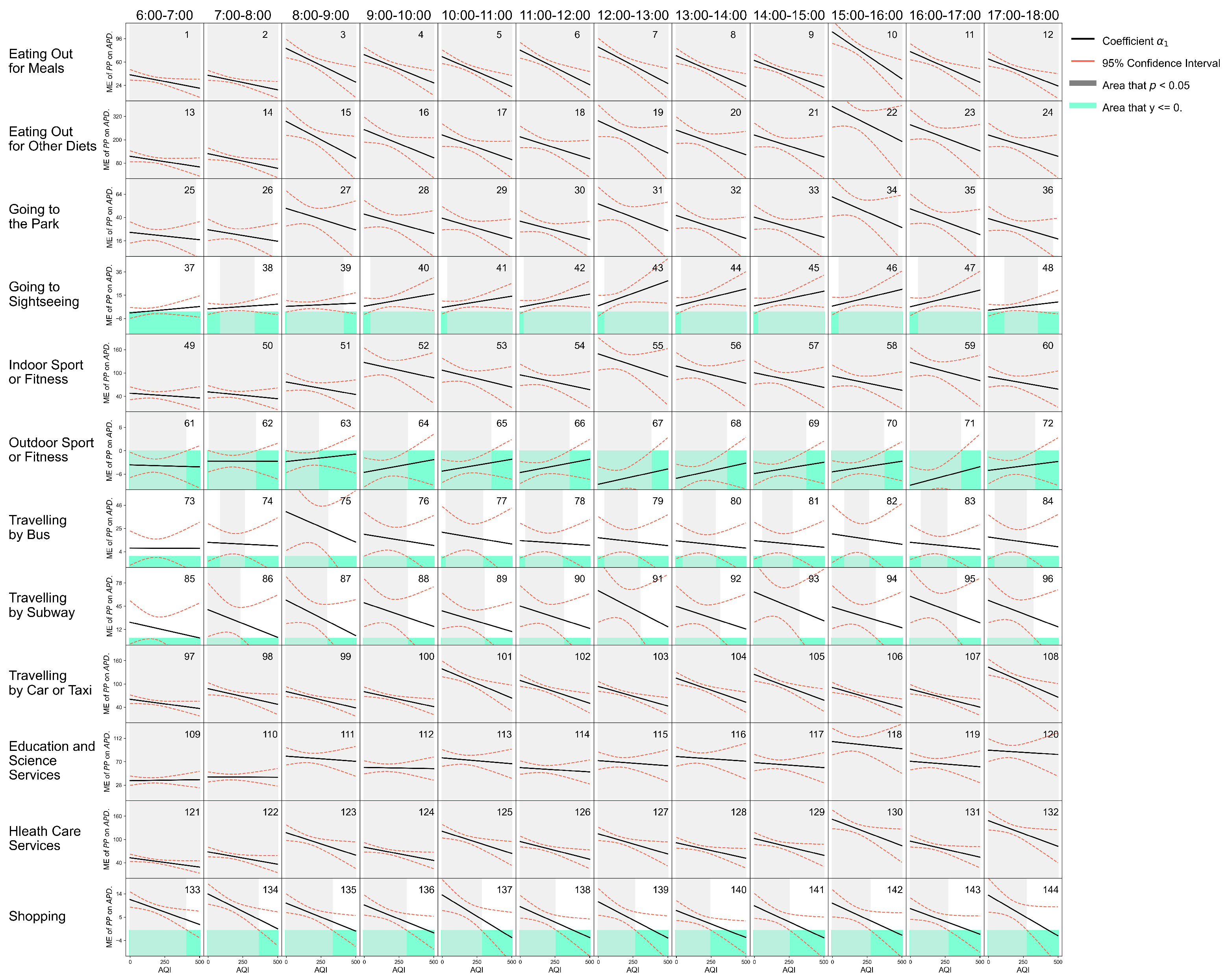

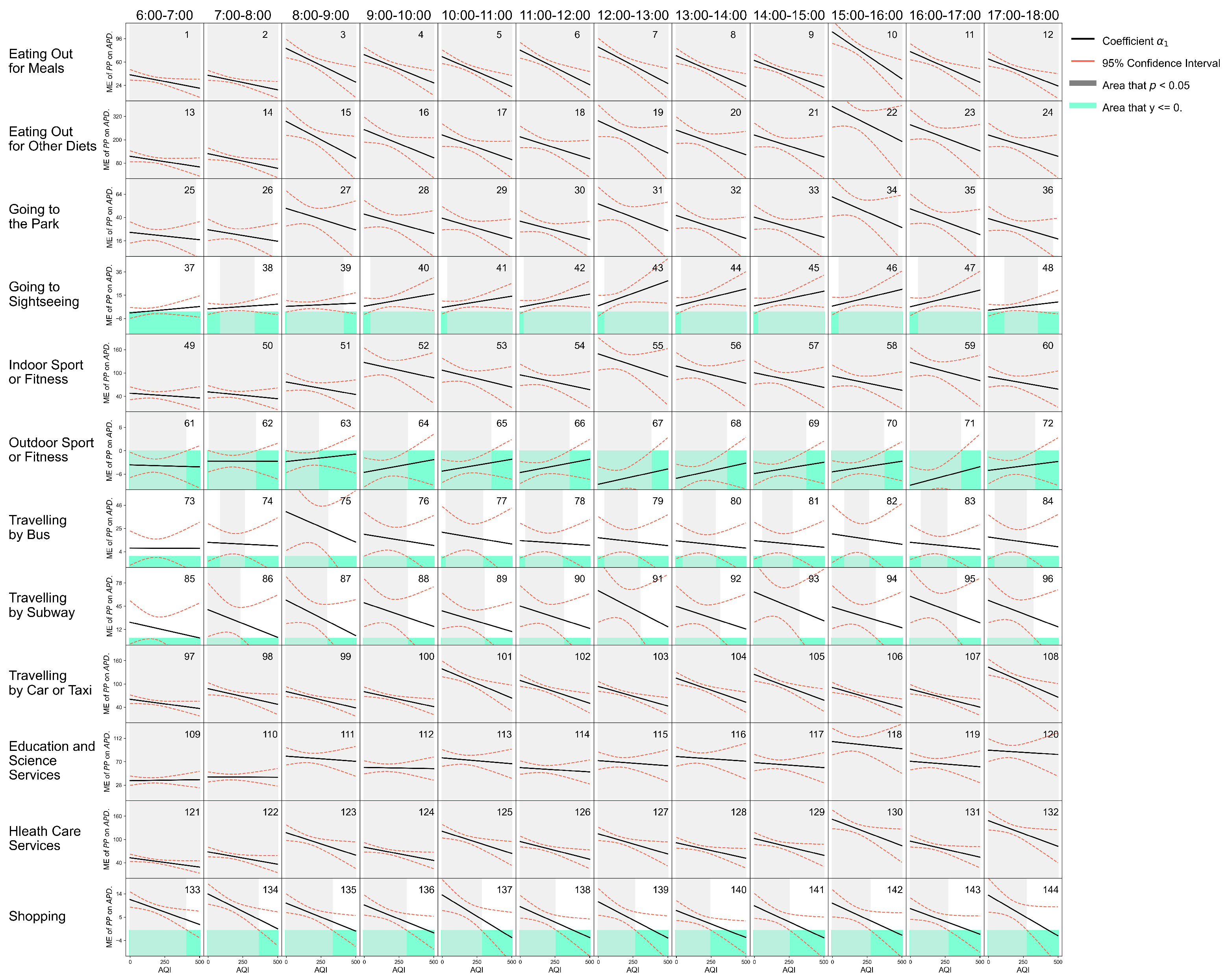

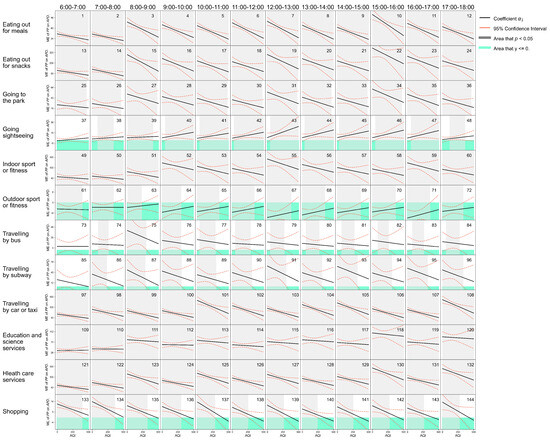

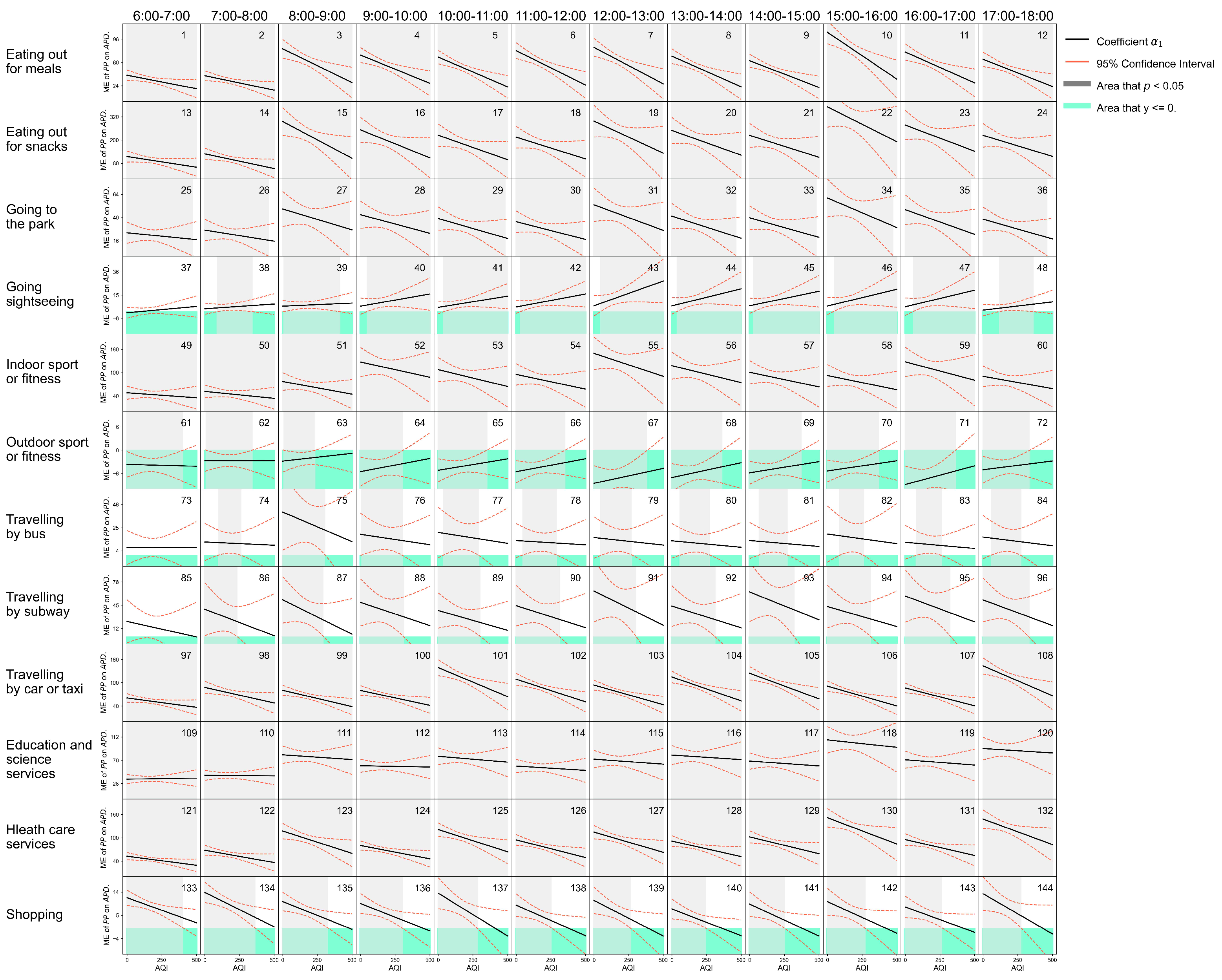

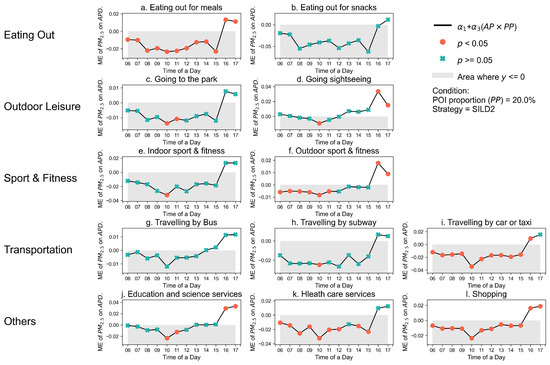

5.2. Qualitative Impact of Air Pollution on PABs

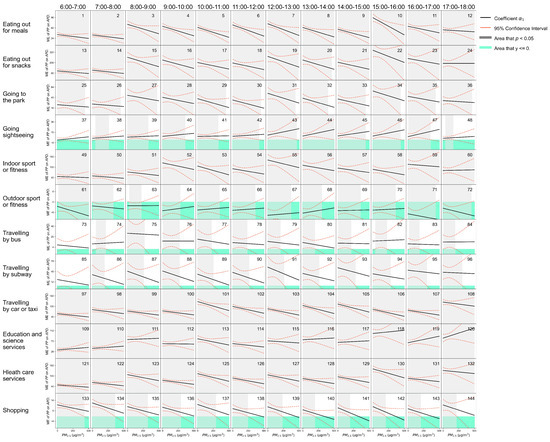

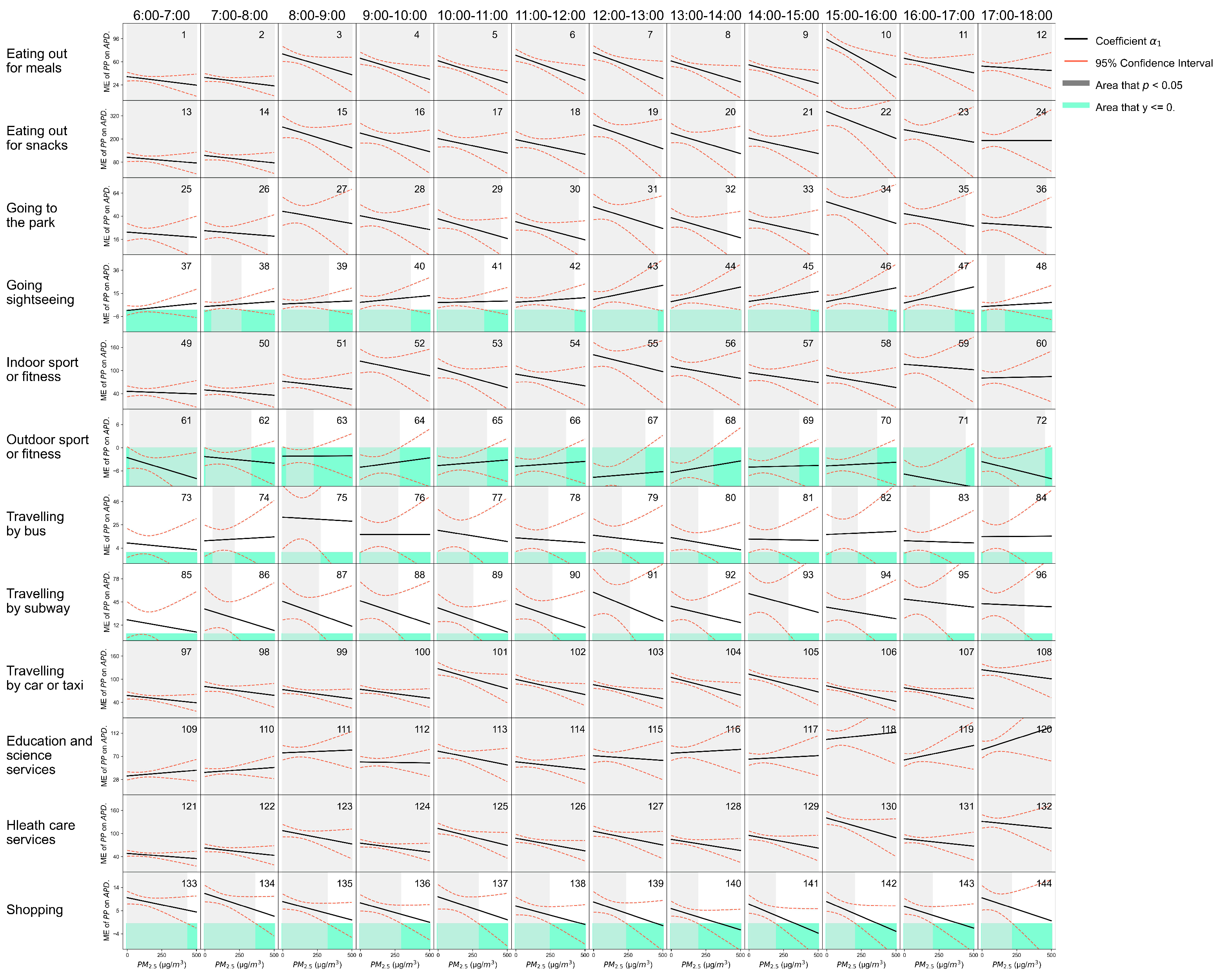

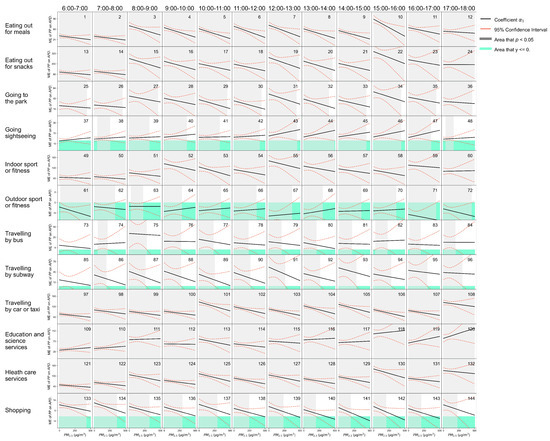

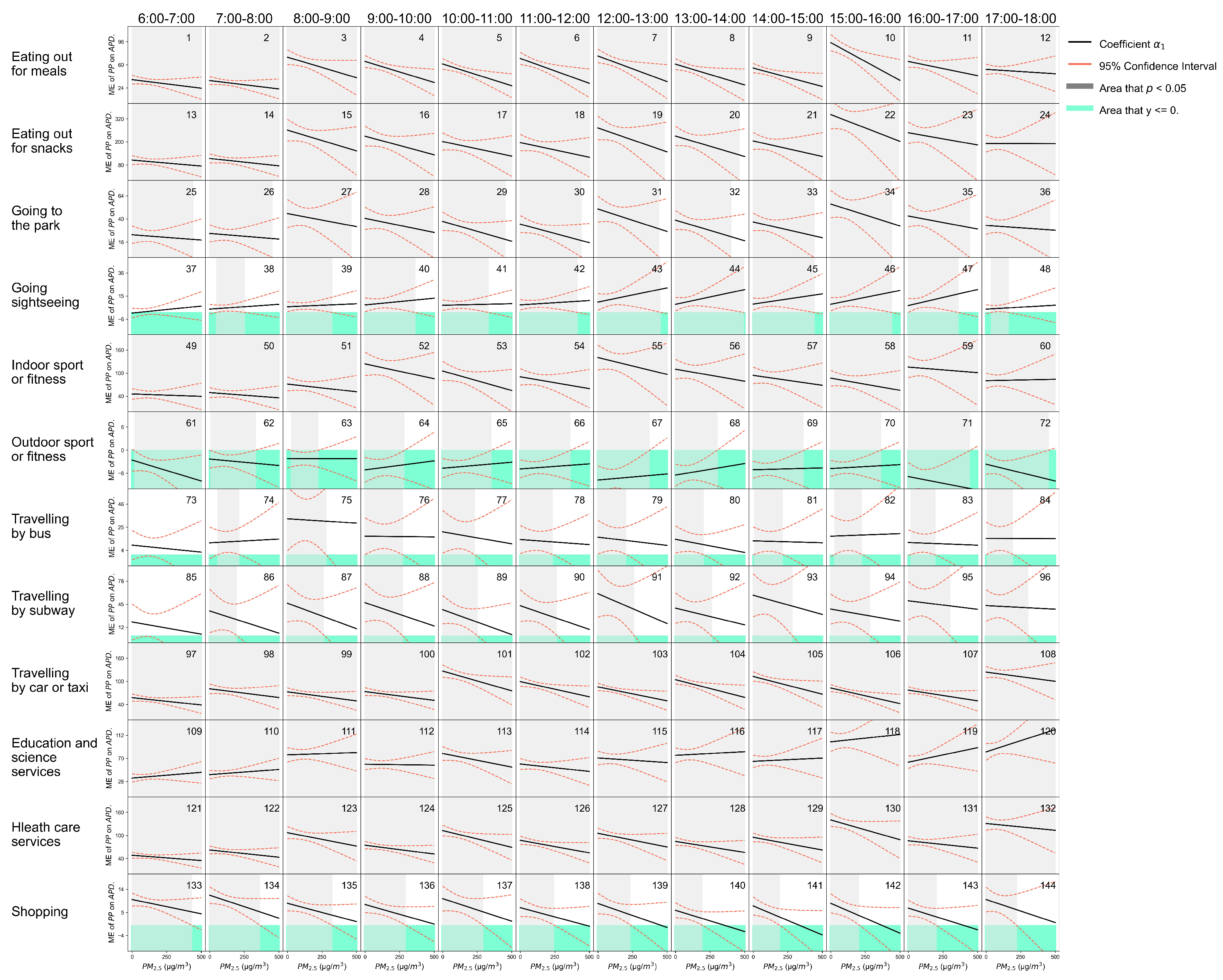

Figure 2 (1) to (144) shows the changes by AQI for multi-PABs at different TPs by using SILD2. From left to right for each row, they are arranged in TP order from 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. for each PAB. For each subplot, the x-axis is the AQI, while the y-axis is the marginal effect of PP on APB. When the value of y is less than zero, the area in the plot is displayed in aquamarine, and when the coefficients are significant within a 95% confidence interval (), the area in the plot is displayed as grey. Similar results that use PM2.5 as a pollution indicator and SILD2 are also given in Appendix A (Figure A3), where the results by using SILD1 are also given (Figure A1 and Figure A2). Given that Figure 2 reports 144 h-by-activity estimates, we do not apply a formal multiple-testing correction and instead interpret isolated significant coefficients cautiously, focusing on patterns that are consistent across adjacent TPs, across AQI and PM2.5 indicators, and across SILD1/SILD2 specifications; all marginal effects are accompanied by heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors, clustered at the VP level, and statistical significance is evaluated at the 5% level.

Figure 2 documents that, with the AQI increase, the impact of the POI proportion on APD changes significantly for the grey area, which means the AQI impacts the number of people visiting that type of POI. The simple overall result can qualitatively conclude that the AQI impacts multiple PABs at the same time. However, their impact also depends on the time and the AQI value itself. It means that over a day, the impact of air pollution on a type of PAB changes as time goes by. Further, not all the changes in AQI can cause a significant impact of air pollution on PABs. Also, not all people who participate in the types of PABs will decrease when the air quality becomes worse, some of the PABs, such as going sightseeing are positively impacted by the air pollution, where the positive impact is defined as when the air pollution indicator increases (the air quality becomes worse), and the PAB becomes more active (with a higher people density); the negative impact is defined oppositely.

Figure 1.

Four examples of the CDR-based population distribution (unique IMSI number) at different time points. (a) Description of population distributions across all of Beijing at 6:00 a.m. on 2 February 2015; (b) Description of population distributions across all of Beijing at 6:00 p.m. on 2 February 2015; (c) Description of population distributions across all of Beijing at 6:00 a.m. on 19 February 2015; (d) Description of population distributions across all of Beijing at 6:00 p.m. on 19 February 2015; (e) Description of population distributions in the localised inner area at 6:00 a.m. on 2 February 2015; (f) Description of population distributions in the localised inner area at 6:00 p.m. on 2 February 2015; (g) Description of population distributions in the localised inner area at 6:00 a.m. on 19 February 2015; (h) Description of population distributions in the localised inner area at 6:00 p.m. on 19 February 2015.

Figure 1.

Four examples of the CDR-based population distribution (unique IMSI number) at different time points. (a) Description of population distributions across all of Beijing at 6:00 a.m. on 2 February 2015; (b) Description of population distributions across all of Beijing at 6:00 p.m. on 2 February 2015; (c) Description of population distributions across all of Beijing at 6:00 a.m. on 19 February 2015; (d) Description of population distributions across all of Beijing at 6:00 p.m. on 19 February 2015; (e) Description of population distributions in the localised inner area at 6:00 a.m. on 2 February 2015; (f) Description of population distributions in the localised inner area at 6:00 p.m. on 2 February 2015; (g) Description of population distributions in the localised inner area at 6:00 a.m. on 19 February 2015; (h) Description of population distributions in the localised inner area at 6:00 p.m. on 19 February 2015.

Specifically, in terms of the PABs of eating out (for restaurant meals or snacks), outdoor leisure of going to the park, indoor sports or fitness, education and science services, travelling by car or taxi, education and science services, and healthcare services, the impact of air pollution indicated by AQI is persistent during a day and almost the whole of the AQI range from 0 to 500. Also, all the types of PAB have a negative relationship with air quality, that is, with an increase in the AQI, the impact of the POI proportion on the density of people becomes lower, which means air pollution decreases the desire of people to visit these POIs to participate in these PABs. At the same time, the degree of the impact of the AQI that is, represented by increases when the time goes from morning to afternoon, indicated by , and becomes higher, leading to the slope of the line in the subplots getting steeper, while the impact decreases from the afternoon to the evening.

Figure 2.

The marginal effects of AQI on PABs by using SILD2.

Figure 2.

The marginal effects of AQI on PABs by using SILD2.

But in terms of other PABs, including outdoor leisure of going sightseeing, outdoor sport or fitness, travelling by bus and subway, and shopping, the significance of the impact of air pollution varies both with AQI and TP. The positive association for sightseeing in certain afternoon hours likely reflects behavioural selection: some visitors may target smoggy periods to avoid crowds and fixed ticket prices. However, this interpretation is correlative. Alternative mechanisms include venue scheduling (e.g., indoor exhibits), AQI misperception, and data-driven density dilution in large scenic VPs. We therefore (i) replicate using PM2.5, (ii) re-estimate with alternative spatial aggregation, and (iii) conduct leave-one-district-out checks. The sign persists but attenuates, suggesting a real yet context-dependent effect that merits targeted field validation.

A similar trend of the impact is on outdoor sport or fitness, the rising line indicates that when the AQI gets higher, the impact of POI proportion on population density increases as well. However, the effect of the impact is coloured aquamarine, indicating that the impact of the POI proportion itself is negative, which means that, in terms of this type of POI, a greater number of the POI, causes less visitor density. This is because an outdoor sports place is normally has a greater area, e.g., a football field, compared with other types of POI, the point of the place accounts for a higher percentage of a VP. Thus, if more of such an POI exists, the density of people is less than where there is another POI with less area. In terms of the two transportation modes, travelling by bus and subway, the impact of the AQI on both PABs is insignificant in the early morning, and only when the AQI is less than 280, then the number of people who participate in the PABs decreases as the air quality gets worse. The results of all three transportation PABs show that people decrease their travel outdoors no matter which of the three modes of transportation is used during the daytime. Furthermore, in terms of the shopping PAB, AQI that is lower than about 350 can cause a significant negative impact on the PAB, and such an impact can last all day.

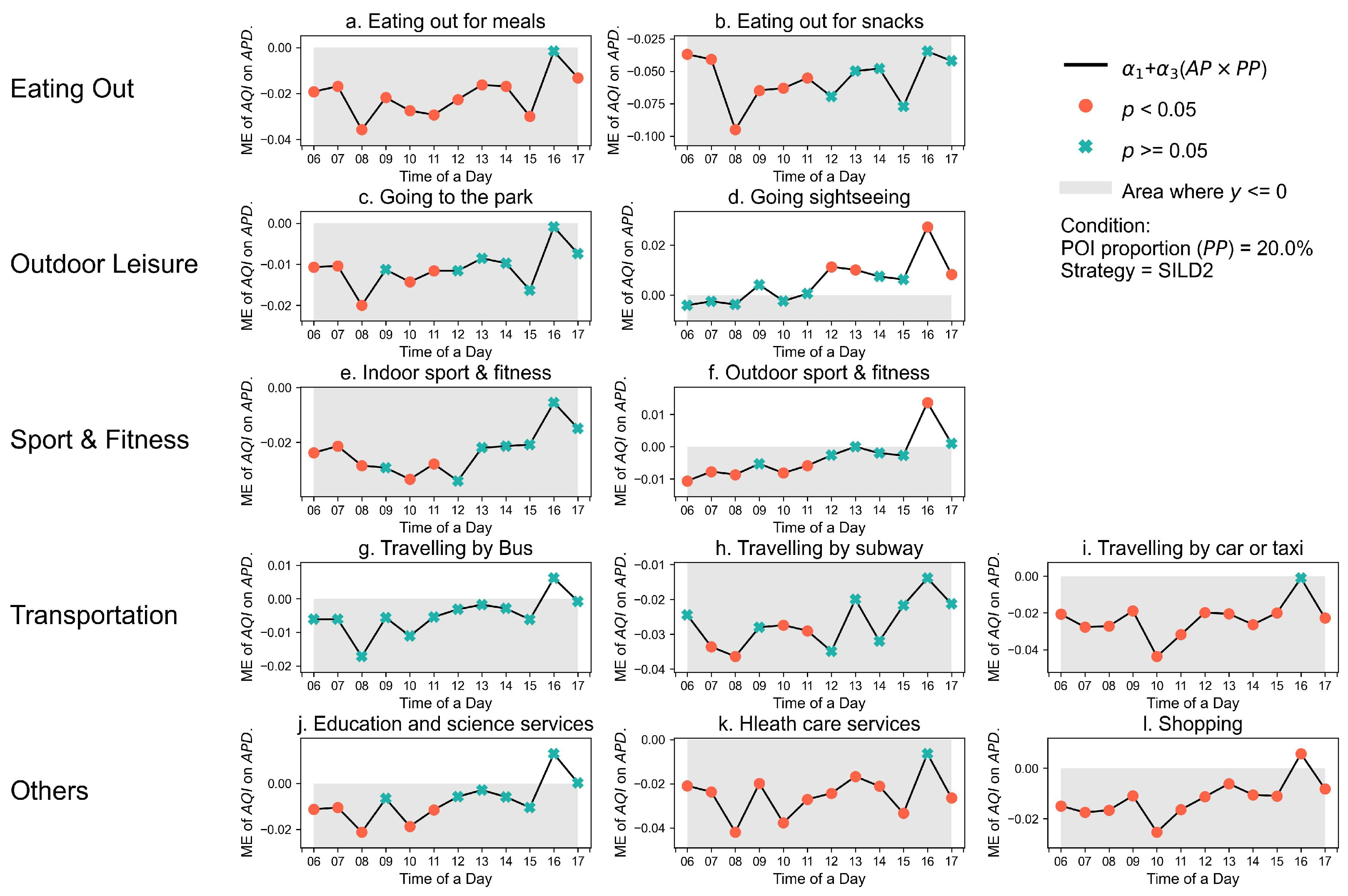

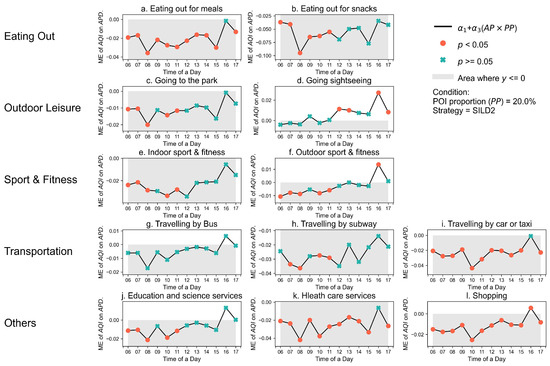

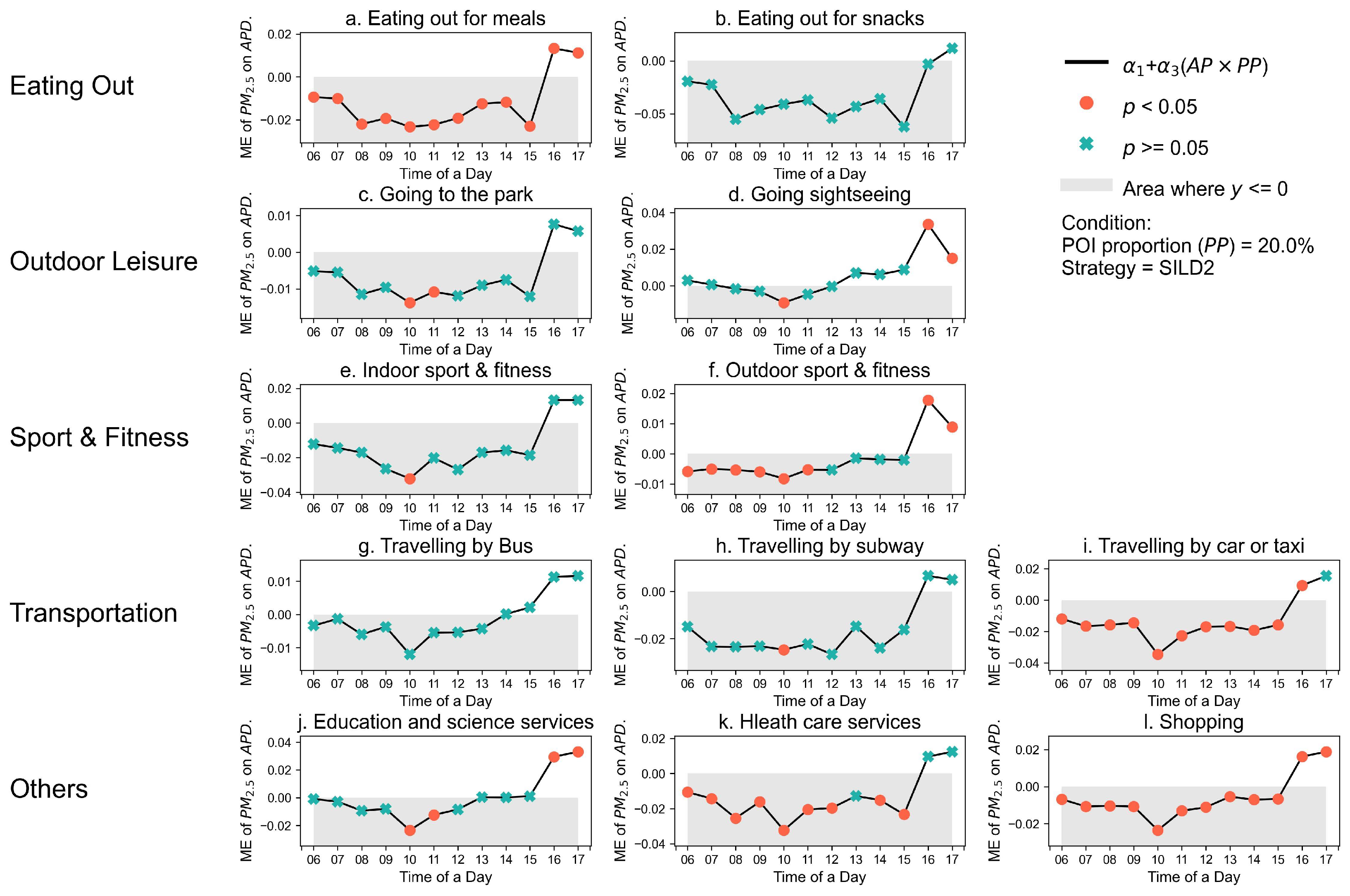

5.3. Quantitative Impact of Air Pollution on Multiple Types of PAB in Different TPs

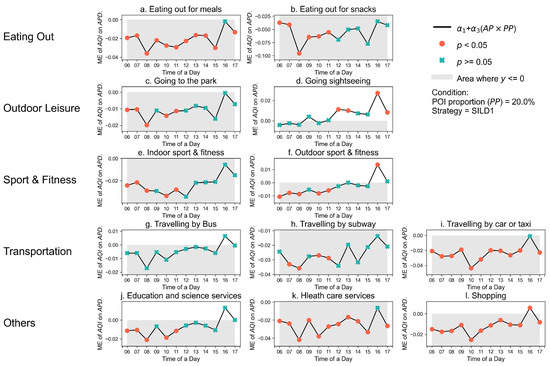

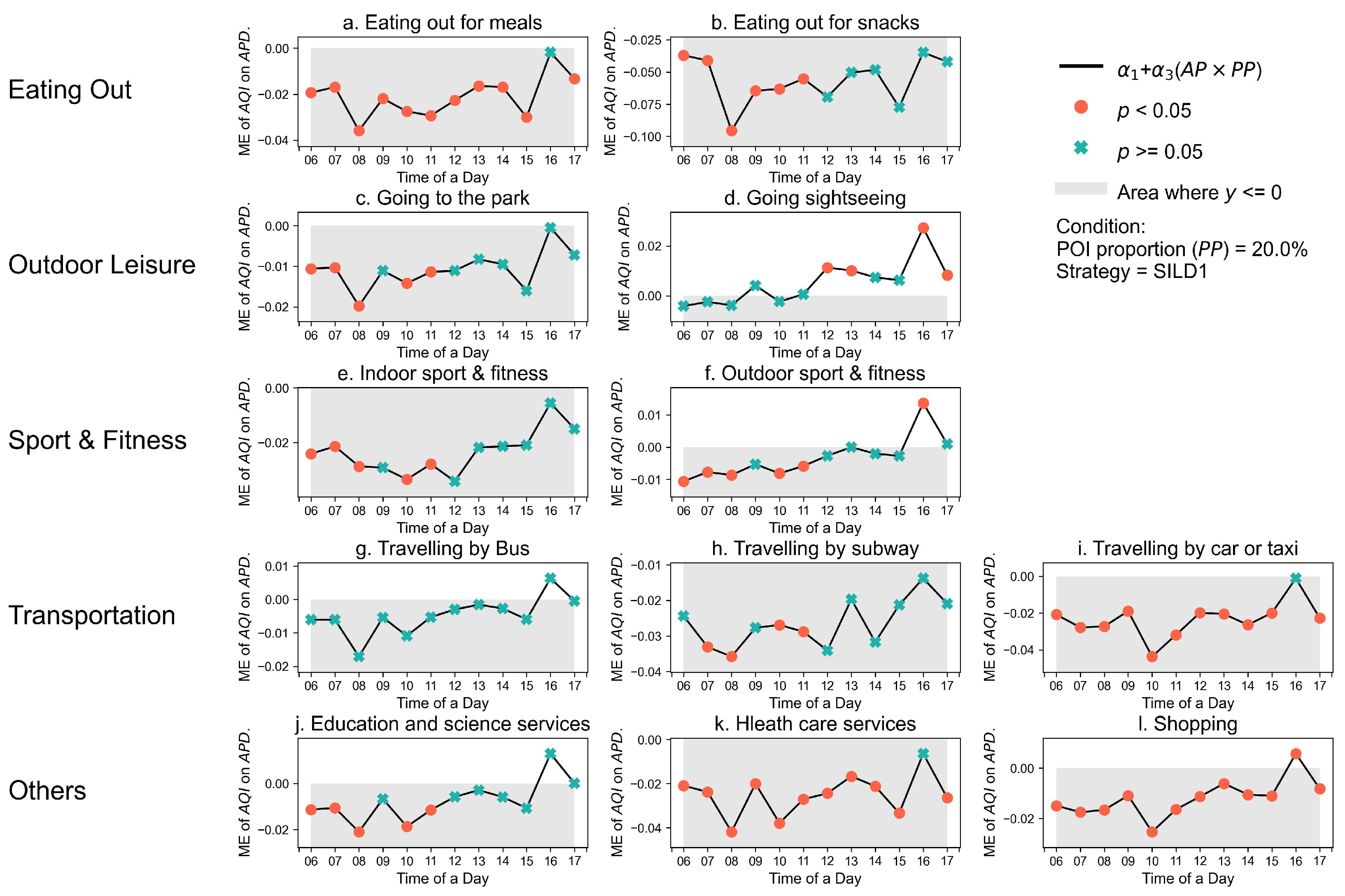

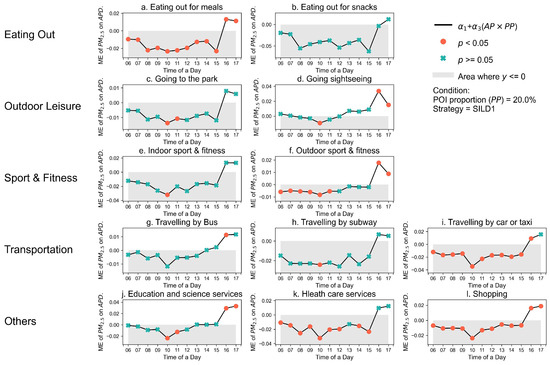

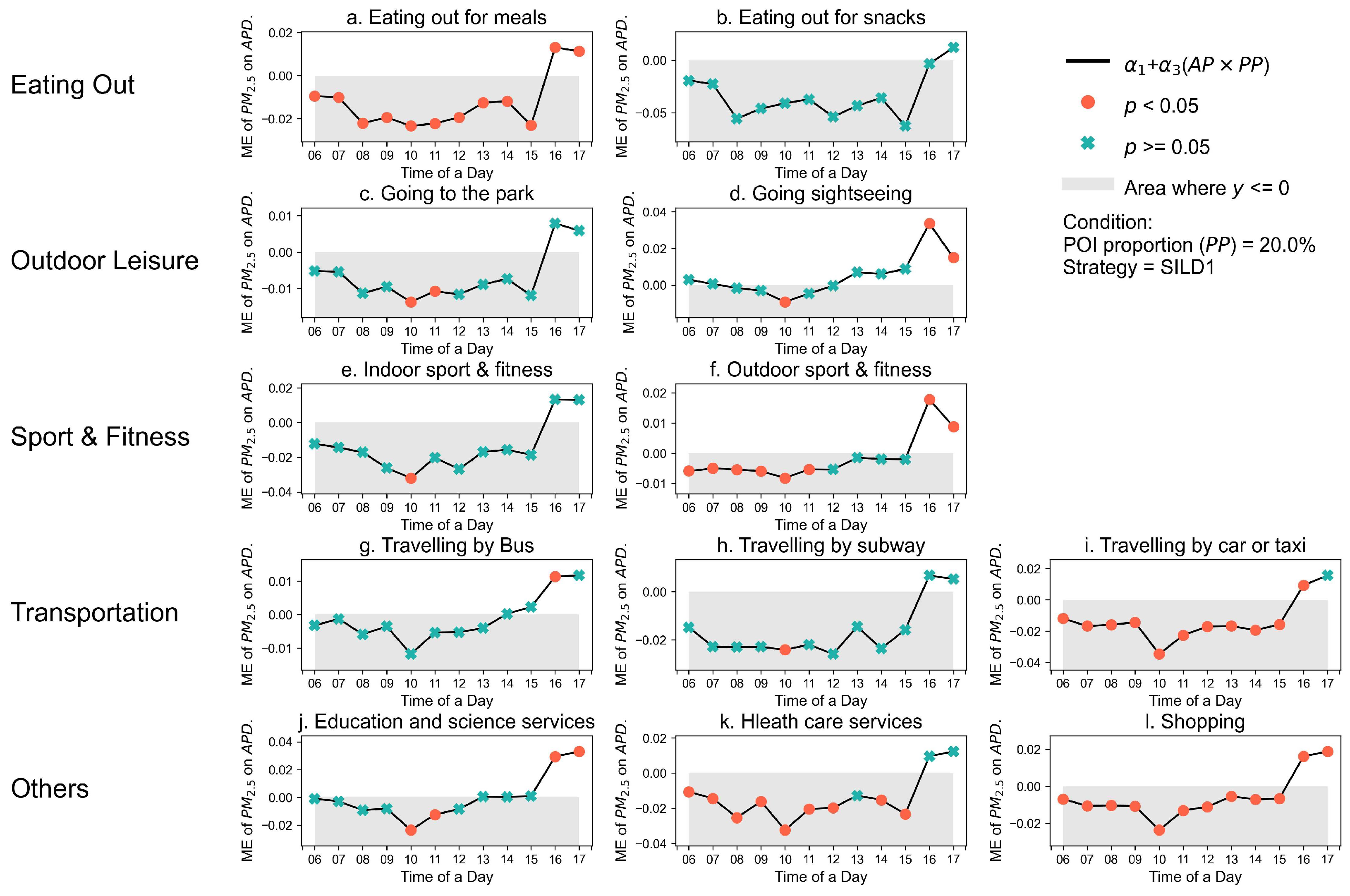

Figure 3a–l illustrate the quantitative of AQI changes by TPs for multi-PABs by using SILD2, with the fixed POI proportion of 20%. For each subplot, the x-axis is the time of a day (TPs), while the y-axis is the marginal effect of AQI on APB. When the value of is less than zero, the area in the plot is displayed in grey, and when the coefficient is significant within a 95% confidence interval (), the node in the line is displayed as a red circle, while the insignificant coefficient is displayed as a green cross. Similar results that use PM2.5 as a pollution indicator and SILD2 are also given in Appendix A (Figure A6), where the results using SILD1 are also given (Figure A4 and Figure A5).

Figure 3.

The marginal effects of AQI on PABs with a fixed POI proportion of 20% by using SILD2.

In order to compare the impact of air pollution on multiple types of PAB in a quantitative way, the POI proportion is fixed as 20%, which is the maximum proportion (of bus stops) among all types of POI. Under this condition, the description of the impact of air pollution is given as follows.

In terms of the eating out activity, air pollution decreases the desire of people to have a meal out over a day, except at the TP of 16:00–17:00. At a normal lunchtime (12:00–13:00), when AQI increases by 100 units, the density of people decreases by about 2.5 people/km2 for a VP, on average. The biggest influence over a day happens at 8:00, when the people density will decrease by about 4 people/km2 when the AQI increases by 100. While the least influence happens at 17:00, when the density decreases by 1 person/km2 under the same change of AQI. However, air pollution only has a significant impact on the eating out activity for snacks before 12:00. The most impact happens at 8:00 as well, when the people density will decrease by 10 people/km2 when AQI increases by 100.

In terms of outdoor leisure activities, people are impacted by air pollution only in the morning when they plan to go to the park (9:00 is an exception). The maximum influence of air pollution is present at 8:00, with 2 people/km2 decreasing when the AQI increases by 100. However, th epeople going sightseeing activity has a positive relationship with AQI after 12:00 At 16:00, an increase of 100 AQI can cause 3 people/km2 more to visit the sightseeing sites, which can avoid more crowded occasions yet pay the same ticket price.

In terms of the sport and fitness activities, people who attend both indoor and outdoor locations can be impacted by AQI in the morning period (before 12:00), where the top impact for indoor sports or fitness activities happens at 10:00, about people/km2 decreases when the AQI increases by 100. In terms of the TP in the afternoon and evening (after 12:00), indoor sport and fitness seem not to be impacted by the air pollution, but at 16:00, a rise of 100 in the AQI can result in an increase of people/km2 in a VP on average.

In terms of the transportation modes, travelling by bus changes little with AQI changing over a day where travelling by bus via stops as POIs has the highest proportion, accounting for of the total POIs in the area. It might be caused by the outdoor air pollution decreasing the number of people who travel by bike or walk, who consider that travelling by bus can partly lessen the exposure to pollution. But for travelling by subway, the impact is most significant at TPs of 7:00, 8:00, 10:00 and 11:00, when the biggest impact of AQI increases by 100 and is linked to a decrease in 4 people/km2. Travel by car or taxi is significantly impacted by air pollution over the whole day except at 16:00, where at 10:00 the impact is the most, which can cause a 5 people/km2 decrease when the 100 AQI increases.

For education and science services activities, such PABs are impacted by air pollution in the morning before the TP of 11:00, except for the TP of 8:00 a.m. to 9:00 a.m. when air pollution affects travel, where about 2.5 people/km2 of people who attend the activity decreases when the AQI increases by 100. In terms of the healthcare services, the impact of air pollution significantly exists over the whole of the day except at 16:00, where most of the impact happens at 8:00, causing a people/km2 decrease as the AQI increases. In terms of shopping, the impact of air pollution on the PAB is significant over a day. However, at 16:00, the impact is positive against the negative impact in other TPs. The reason for the pattern might be the same as the PAB of going sightseeing. Among the negative influences, the top impact happens at 10:00, where 100 AQI can cause a 3 people/km2 decrease in a VP on average.

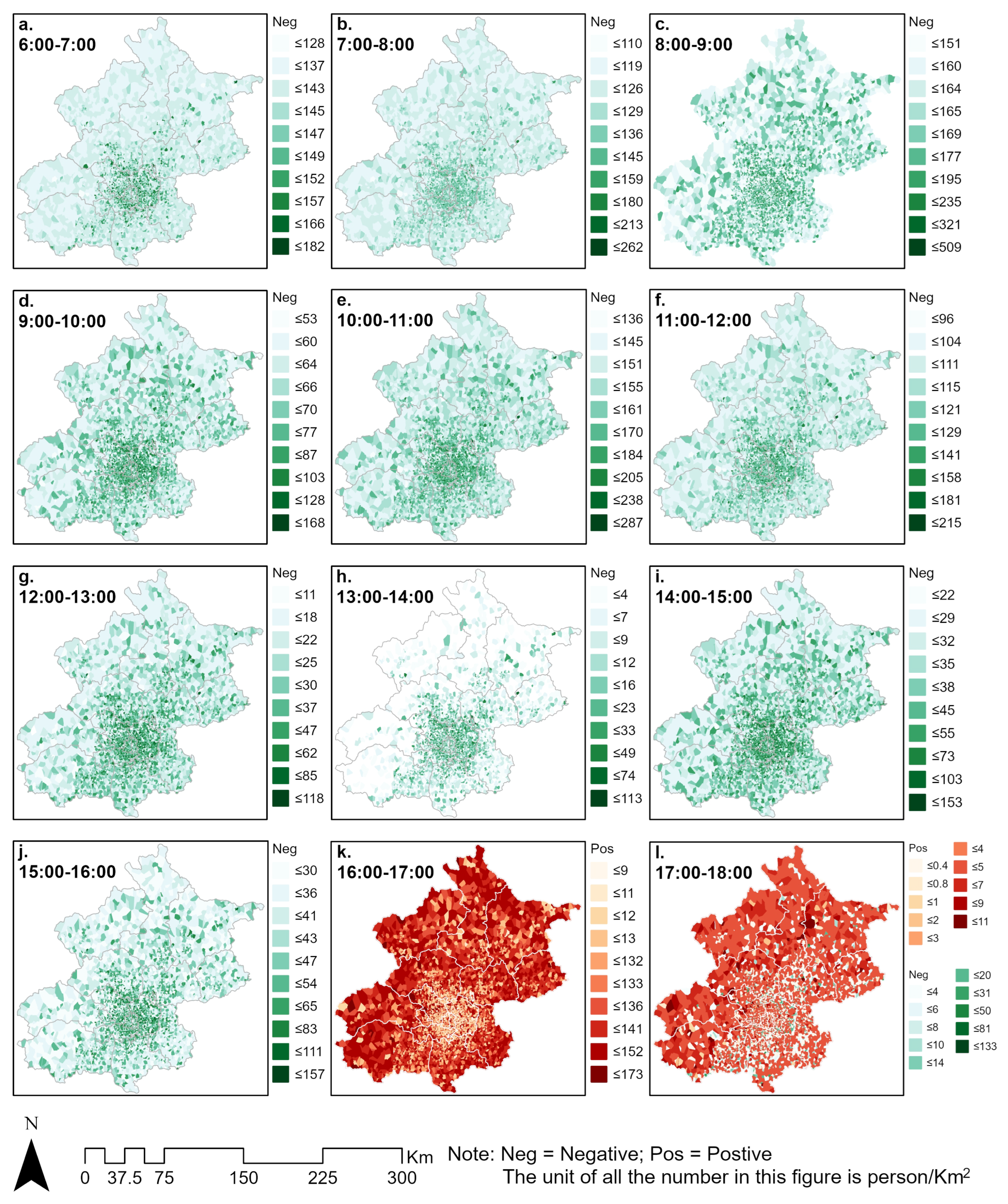

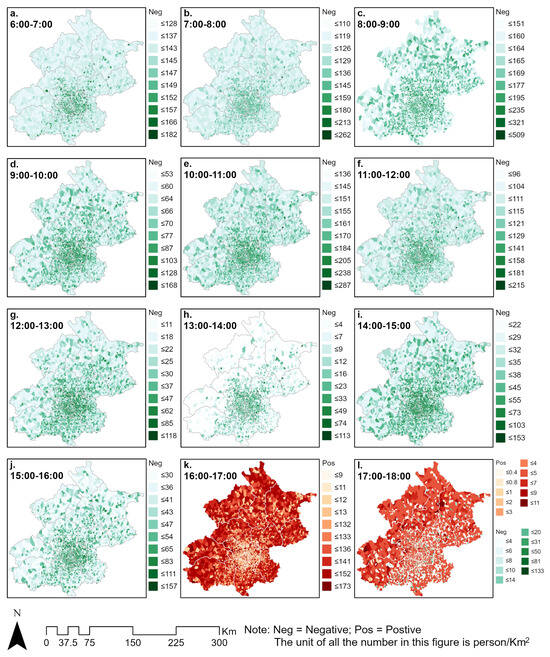

5.4. Spatial Distributions of CII During a Day

Based on Equation (4), the CII for each VP at different TPs is computed. Figure 4 illustrates that the spatial distribution of CII in Beijing, where subplots (a–l) correspond to the distributions at 12 TPs. In the figure, the negative impact is shown in green, while the red parts illustrate that the impact of air pollution has a positive relationship with the total PABs.

Figure 4.

CII distributions over a day.

It is obvious that the impact of air pollution on overall PABs is spatially unevenly distributed. At the first two TPs from 6:00–8:00 a.m., the CII distribution indicates the impact is relatively concentrated around the centre of Beijing. Then, from the third TP (8:00–9:00 a.m.), the impact starts to be scattered over the whole of Beijing, with the absolute people density value of PAB overall growing from the maximum of to people/km2 when AQI increases by 100. After this time, the CII is still dispersedly distributed, but the overall absolute quantity of the CII becomes less compared to that of the last TP. This situation persists until 13:00 (Figure 4h). The overall quantity of CII becomes much less and the impact changes back to be relatively concentrated around the centre of Beijing, but in the suburbs, the impact vanishes in most areas. However, after a noon break, the distribution of CII rejuvenates in the late morning.

Dramatically, at the TP of 16:00–17:00, the overall impact of air pollution on 12 PABs becomes positive for the whole area of Beijing. It is because multiple impacts of air pollution on every single PAB accumulate in the afternoon. This is illustrated as multiple positive relationships between PAB and air pollution exist, such as going sightseeing, and outdoor sports and fitness activities. However, after 17:00, the total positive impact has been neutralised by plenty of negative impacts, causing a mixed situation of both negative and positive impacts of PAB (CII) distributed across Beijing. Among them, the negative impact is mainly distributed in the city centre, while in the suburb area, the CII is mainly positively distributed.

6. Conclusions

Our dual suppression pattern also helps to clarify the broader debate on indoor substitution. Previous studies discussed in the Section 2 have documented pollution-induced increases in specific indoor or sedentary behaviours, such as gym attendance, online shopping, or time spent at home, even as outdoor activity declines. In contrast, our city-wide adjusted population density across twelve public activity types shows mostly simultaneous reductions in both outdoor and indoor PABs, with only a few categories (for example, sightseeing on some afternoons) displaying positive responses that we interpret as congestion-avoidance. At least three features of our design may contribute to this difference: we observe a much broader set of public activities rather than a single behaviour, we focus on a major holiday period when schedules are relatively flexible, and we model short-run, hourly responses at the VP level rather than via daily aggregates. Taken together, these results suggest that indoor substitution is far from universal; in some urban contexts, a defensive “stay-at-home” response that suppresses most public activities appears to dominate reallocation between venues.

This study aims to investigate the spatiotemporal qualitative and quantitative impact of air pollution on multiple human activity behaviours in the same space and time based on the CDR data in Beijing as a case study. The 12 types of PABs are selected to be analysed. The outputs of the study illustrate that, first, the qualified impact of air pollution in different TPs, i.e., for each type of PAB, if and how the PABs are impacted by air pollution, which can vary from the start to the end of daytime. Then by fixing the individual (POI) effect (using a specific POI number to compute the impact of air quality on PABs), the impact of air quality on multiple types of PAB is compared quantitatively as well. Index CII representing the summarised impact for each VP, is computed and mapped over the study area.

Using the adjusted population density (APD) measure, this study qualitatively and quantitatively evaluated how air pollution affects multiple types of physical activity behaviours across Beijing. Our results indicate that the influence of air pollution on any given activity type varies by time of day. Not every change in AQI produces a statistically significant behaviour change, and the magnitude of impact differs among activities. While most activities (both outdoor and indoor) show decreased participation as air quality worsens, a few activities (such as sightseeing) exhibited a counter-intuitive increase in participation under high pollution. Here, a “positive” impact means that as the pollution indicator rises (air quality deteriorates), the activity becomes more active (people density increases), whereas a “negative” impact means activity levels drop with worse air quality. We quantified these impacts for each PAB category and also mapped their spatial distribution. The findings demonstrate the varying degrees of pollution’s impact on different activities and highlight distinct spatial patterns of this impact across the city.

Our work offers important insights for urban planners and public health policymakers by providing concrete, quantitative evidence of how fluctuations in air quality affect human physical activity. These findings supply a scientific basis for crafting targeted environmental interventions and health promotion strategies. Moreover, the fact that certain leisure activities paradoxically increase during heavy pollution highlights a critical need for better risk communication and protective measures. It appears that some individuals may underestimate or ignore health risks on polluted days (for instance, venturing out to tourist sites despite smog), underscoring the urgency for public health officials and city authorities to raise awareness and protect citizens. In sum, our conclusions are relevant not only to government decision-makers, but also to environmental organisations and the general public, who all play a role in mitigating pollution’s impact on daily life. This study also has limitations, including the reliance on aggregated CDR-derived activity measures and observational fixed-effects associations, which may not fully capture individual behaviours or establish causality; moreover, the use of mobile-phone-based CDRs may introduce sampling and usage biases, the mapping between POI categories and actual physical activities may involve classification uncertainty, and the study period, limited to a short winter window around the Spring Festival, may restrict the generalisability of the findings.

Future directions of the investigation are as follows: First, the study period and case study region could be extended to detect if there are more obvious and varied spatiotemporal disparities, which is important to provide a more flexible methodology to apply to other spatial regions, e.g., to another city in another country. Second, more types of PAB would be considered to model the quantitative and qualitative relationship between air pollution and human mobility. At the same time, because there are some limitations of mobile phone data, more categories of the dataset that can represent the human PABs, e.g., social media data and economic data, can be fused and modelled. In addition, integrating land-use information to better capture spatial context and activity; environment interactions will be explored as an important extension in future work.

Author Contributions

T.L.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Visualisation; G.Y.: Conceptualisation, Project administration; Funding acquisition, Writing—review and editing; S.Y.: Conceptualisation, Investigation; J.Q.: Validation, Software; X.H.: Methodology, Resources; Z.Z.: Methodology, Validation, Visualisation; J.L.: Software, Resources; S.P.: Methodology, Validation; X.Z.: Visualisation, Supervision; G.Z.: Formal analysis, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from Peking University and Queen Mary University of London.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

The marginal effects of AQI on PABs by using SILD1.

Figure A1.

The marginal effects of AQI on PABs by using SILD1.

Figure A2.

The marginal effects of PM2.5 on PABs by using SILD1.

Figure A2.

The marginal effects of PM2.5 on PABs by using SILD1.

Figure A3.

The marginal effects of PM2.5 on PABs by using SILD2.

Figure A3.

The marginal effects of PM2.5 on PABs by using SILD2.

Figure A4.

The marginal effects of AQI on PABs with a fixed POI proportion of 20% by using SILD1.

Figure A4.

The marginal effects of AQI on PABs with a fixed POI proportion of 20% by using SILD1.

Figure A5.

The marginal effects of PM2.5 on PABs with a fixed POI proportion of 20% by using SILD1.

Figure A5.

The marginal effects of PM2.5 on PABs with a fixed POI proportion of 20% by using SILD1.

Figure A6.

The marginal effects of PM2.5 on PABs with a fixed POI proportion of 20% by using SILD2.

Figure A6.

The marginal effects of PM2.5 on PABs with a fixed POI proportion of 20% by using SILD2.

References

- Shen, L.; Shuai, C.; Jiao, L.; Tan, Y.; Song, X. Dynamic sustainability performance during urbanization process between BRICS countries. Habitat Int. 2017, 60, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebenstein, A.; Fan, M.; Greenstone, M.; He, G.; Zhou, M. New evidence on the impact of sustained exposure to air pollution on life expectancy from China’s Huai River Policy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 10384–10389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dockery, D.W.; Pope, C.A.; Xu, X.; Spengler, J.D.; Ware, J.H.; Fay, M.E.; Ferris, B.G., Jr.; Speizer, F.E. An association between air pollution and mortality in six US cities. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 329, 1753–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lelieveld, J.; Evans, J.S.; Fnais, M.; Giannadaki, D.; Pozzer, A. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature 2015, 525, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X. Smog in our brains: Gender differences in the impact of exposure to air pollution on cognitive performance. In IZA Discussion Papers; Technical Report; Institute of Labor Economics: Bonn, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lavy, V.; Ebenstein, A.; Roth, S. The Impact of Short Term Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution on Cognitive Performance and Human Capital Formation; Technical Report; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X. The impact of exposure to air pollution on cognitive performance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 9193–9197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivin, J.G.; Neidell, M. The impact of pollution on worker productivity. Am. Econ. Rev. 2012, 102, 3652–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.Y.; Graff Zivin, J.; Gross, T.; Neidell, M. The effect of pollution on worker productivity: Evidence from call center workers in China. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2019, 11, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, J.; Zivin, J.G.; Mullins, J.; Neidell, M. What do we know about short-and long-term effects of early-life exposure to pollution? Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2014, 6, 217–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wang, J.; Sun, C.; Zhang, X.; Kahn, M.E. Air pollution lowers Chinese urbanites’ expressed happiness on social media. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2019, 3, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tainio, M.; Andersen, Z.J.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Hu, L.; De Nazelle, A.; An, R.; Garcia, L.M.; Goenka, S.; Zapata-Diomedi, B.; Bull, F.; et al. Air pollution, physical activity and health: A mapping review of the evidence. Environ. Int. 2021, 147, 105954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, D.E.; Mannucci, P.M.; Tell, G.S.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Brook, R.D.; Donaldson, K.; Forastiere, F.; Franchini, M.; Franco, O.H.; Graham, I.; et al. Expert position paper on air pollution and cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, R.D.; Newby, D.E.; Rajagopalan, S. Air pollution and cardiometabolic disease: An update and call for clinical trials. Am. J. Hypertens. 2018, 31, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnsen, N.F.; Ekblond, A.; Thomsen, B.L.; Overvad, K.; Tjønneland, A. Leisure time physical activity and mortality. Epidemiology 2013, 24, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodcock, J.; Franco, O.H.; Orsini, N.; Roberts, I. Non-vigorous physical activity and all-cause mortality: Systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 40, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokols, D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am. J. Health Promot. 1996, 10, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Huangfu, Y.; Lima, N.; Jobson, B.; Kirk, M.; O’Keeffe, P.; Pressley, S.N.; Walden, V.; Lamb, B.; Cook, D.J. Analyzing the relationship between human behavior and indoor air quality. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2017, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report; US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Volume 2008.

- Yu, H.; Yu, M.; Gordon, S.P.; Zhang, R. The association between ambient fine particulate air pollution and physical activity: A cohort study of university students living in Beijing. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, N.R.; Da Graca, G.C. Impact of PM2.5 in indoor urban environments: A review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 42, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichmann, J.; Lind, T.; Nilsson, M.M.; Bellander, T. PM2.5, soot and NO2 indoor–outdoor relationships at homes, pre-schools and schools in Stockholm, Sweden. Atmos. Environ. 2010, 44, 4536–4544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghestani, A.; Tayarani, M.; Allahviranloo, M.; Gao, H.O. Cordon pricing, daily activity pattern, and exposure to traffic-related air pollution: A case study of New York City. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engström, E.; Forsberg, B. Health impacts of active commuters’ exposure to traffic-related air pollution in Stockholm, Sweden. J. Transp. Health 2019, 14, 100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, R.; Ji, M.; Yan, H.; Guan, C. Impact of ambient air pollution on obesity: A systematic review. Int. J. Obes. 2018, 42, 1112–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, R.; Shen, J.; Ying, B.; Tainio, M.; Andersen, Z.J.; de Nazelle, A. Impact of ambient air pollution on physical activity and sedentary behavior in China: A systematic review. Environ. Res. 2019, 176, 108545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, R.; Yu, H. Impact of ambient fine particulate matter air pollution on health behaviors: A longitudinal study of university students in Beijing, China. Public Health 2018, 159, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; An, R.; Andrade, F. Ambient fine particulate matter air pollution and physical activity: A longitudinal study of university retirees in Beijing, China. Am. J. Health Behav. 2017, 41, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, E.M.; Dearborn, D.G.; Jackson, L.W. Activity change in response to bad air quality, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007–2010. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhu, L.; Xu, Y.; Lyu, J.; Imm, K.; Yang, L. Relationship between air quality and outdoor exercise behavior in China: A novel mobile-based study. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2017, 24, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Li, S.; Li, P.; Liu, J.; Long, K. How does air pollution influence cycling behaviour? Evidence from Beijing. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 63, 826–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Huang, G.; Fisher, B. Air quality, human behavior and urban park visit: A case study in Beijing. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.J.; Balluz, L.; Mokdad, A. Association between media alerts of air quality index and change of outdoor activity among adult asthma in six states, BRFSS, 2005. J. Community Health 2009, 34, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, R.; Xiang, X. Ambient fine particulate matter air pollution and leisure-time physical inactivity among US adults. Public Health 2015, 129, 1637–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Laird, N.M.; Ware, J.H. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics 1982, 38, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, R.; Ma, H.; Ma, H.; Li, J. Impacts of different air pollutants on dining-out activities and satisfaction of urban and suburban residents. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqi, Z.; Xiaonan, Z.; Zhida, S.; Cong, S. Influence of air pollution on urban residents’ outdoor activity: Empirical study based on dining-out data from the Dianping website. J. Tsinghua Univ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 56, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Berk, R.A. An introduction to sample selection bias in sociological data. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Poslad, S.; Rui, X.; Yu, G.; Fan, Y.; Song, X.; Li, R. Using an internet of behaviours to study how air pollution can affect people’s activities of daily living: A case study of Beijing, China. Sensors 2021, 21, 5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewulf, B.; Neutens, T.; Lefebvre, W.; Seynaeve, G.; Vanpoucke, C.; Beckx, C.; Van de Weghe, N. Dynamic assessment of exposure to air pollution using mobile phone data. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2016, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarakonda, S.; Sevusu, P.; Liu, H.; Liu, R.; Iftode, L.; Nath, B. Real-time air quality monitoring through mobile sensing in metropolitan areas. In Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGKDD International Workshop on Urban Computing, Chicago, IL, USA, 10 August 2013; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Tao, Y.; Kwan, M.P.; Chai, Y. Assessing mobility-based real-time air pollution exposure in space and time using smart sensors and GPS trajectories in Beijing. In Smart Spaces and Places; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2021; pp. 102–116. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Kamargianni, M. Air pollution and seasonality effects on mode choice in China. Transp. Res. Rec. 2017, 2634, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]