Abstract

Accurate numerical simulation of debris flows is essential for hazard assessment and early-warning design, yet high-fidelity solvers remain computationally expensive, especially when large ensembles must be explored under epistemic uncertainty in rheology, initial conditions, and topography. At the same time, field observations are typically sparse and heterogeneous, limiting purely data-driven approaches. In this work, we develop a deep-learning Fourier Neural Operator (FNO) as a fast, physics-consistent surrogate for one-dimensional shallow-water debris-flow simulations and demonstrate its application to the Rendinara–Morino system in central Italy. A validated finite-volume solver, equipped with HLLC and Rusanov fluxes, hydrostatic reconstruction, Voellmy-type basal friction, and robust wet–dry treatment, is used to generate a large ensemble of synthetic simulations over longitudinal profiles representative of the study area. The parameter space of bulk density, initial flow thickness, and Voellmy friction coefficients is systematically sampled, and the resulting space–time fields of flow depth and velocity form the training dataset. A two-dimensional FNO in the domain is trained to learn the full solution operator, mapping topography, rheological parameters, and initial conditions directly to and , thereby acting as a site-specific digital twin of the numerical solver. On a held-out validation set, the surrogate achieves mean relative errors of about 6– for flow depth and 10– for velocity, and it generalizes to an unseen longitudinal profile with comparable accuracy. We further show that targeted reweighting of the training objective significantly improves the prediction of the velocity field without degrading depth accuracy, reducing the velocity error on the unseen profile by more than a factor of two. Finally, the FNO provides speed-ups of approximately with respect to the reference solver at inference time. These results demonstrate that combining physics-based synthetic data with operator-learning architectures enables the construction of accurate, computationally efficient, and site-adapted surrogates for debris-flow hazard analysis in data-scarce environments.

1. Introduction

Debris flows represent one of the most hazardous and complex mass-movement processes in steep mountainous environments. Their dynamics arise from nonlinear interactions among topographic forcing, granular–fluid rheology, sediment availability, and hydrological triggers, making accurate prediction intrinsically challenging [1,2,3]. A broad hierarchy of numerical models has therefore been developed to simulate debris-flow propagation, ranging from one-dimensional depth-averaged approaches to fully two- and three-dimensional continuum formulations [4].

Mathematical and numerical modeling plays a crucial role in the study of debris flows, enabling researchers to investigate their development, perform forecasting, and assess potential impacts. These models rely on differential equations derived from conservation laws (mass, momentum, and energy), often complemented by empirical or theoretical closure relations. Among the most sophisticated techniques is Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) [5,6], which is widely employed to simulate sediment transport under both laminar and turbulent regimes. However, fully three-dimensional models entail substantial computational demands, motivating the frequent use of simplified approaches such as the Shallow Water equations [7,8,9].

Discretizing the computational domain, typically through mesh-based techniques using simple geometric elements, is essential for evaluating physical quantities such as stress, velocity, and flow depth. Common discretization strategies include the Finite Element Method (FEM) [10], the Finite Volume Method (FVM) [11] the Smoothed-particle hydrodynamics (SPH) [12,13] and the Particle Finite Element (PFEM) [14,15]. Despite significant advances, numerical solvers often become computationally demanding or suffer from stability constraints, especially in landscapes with strong slope variability, wet–dry transitions, and rapidly evolving flow fronts [16,17].

Comparative case studies show that different numerical codes can reproduce observed runout patterns with varying sensitivity to rheological parameters and topographic resolution [18,19,20]. However, many advanced numerical solvers are distributed as proprietary software requiring paid licenses or subscriptions (e.g., FLO-2D PRO, RAMMS, DAN3D), sometimes at substantial cost [21,22,23]. At the same time, observational debris-flow datasets remain extremely sparse, typically comprising a few instrumented basins or post-event surveys [2]. This data scarcity limits the applicability of purely data-driven machine-learning approaches, which generally require large and diverse training datasets.

Recent reviews identify surrogate modelling, and in particular operator-learning methods, as a promising pathway to overcome these challenges [24,25,26,27]. Surrogate models reduce computational costs by approximating the mappings encoded by numerical solvers while retaining physical consistency when trained on synthetic or real data [28]. Within this context, Fourier Neural Operators (FNOs) have emerged as powerful architectures capable of learning mappings between infinite-dimensional function spaces and efficiently approximating the solution operators of parametric PDEs [29,30,31]. FNOs have already demonstrated excellent performance in modelling advection–diffusion systems and geophysical transport processes, producing stable, mesh-independent, and near-instantaneous predictions of full space–time fields.

In this study, the primary objective is to investigate how the Fourier Neural Operator can be effectively utilized, conditioned, and evaluated for debris-flow modelling in a hazard-oriented context. Specifically, we aim to construct and assess a physics-informed surrogate model capable of reproducing debris-flow dynamics efficiently and consistently along an entire longitudinal profile. Our fully validated numerical solver is therefore employed as a tool to generate physically consistent training data, while particular emphasis is placed on how the governing equations, their discretisation, and the choice of training objective inform the learning process of the surrogate.

In debris-flow modelling, surrogate approaches are especially attractive because they can integrate solver-generated synthetic training data, thereby circumventing the scarcity of field observations. A practical strategy is to rely on robust low-dimensional solvers to generate large ensembles of physically consistent simulations, which can then be compressed by operator-learning architectures. Although one-dimensional models represent the simplest level of the debris-flow modelling hierarchy, they offer two decisive advantages: numerical robustness and extremely efficient generation of large datasets. These features make them ideal for training operator-learning models that require broad parametric coverage, providing a controlled environment in which to develop and validate scalable surrogate strategies. Extensions to 2D and 3D solvers can naturally follow once the framework is established.

In this work, we address three fundamental challenges: the scarcity of high-quality observational debris-flow data; the high computational cost and occasional instability of classical numerical solvers; and the need for surrogate models capable of scaling to higher spatial dimensionality.

To mitigate data scarcity, we generate a comprehensive synthetic dataset using a validated one-dimensional shallow-water debris-flow solver with Voellmy-type rheology [7,32,33]. This dataset is used to train a two-dimensional Fourier Neural Operator that maps , bed elevation, and rheological parameters to the full temporal evolution of the flow. In this study, the surrogate is developed and analyzed with a specific application in mind: the characterization of the Rendinara–Morino debris-flow system for hazard assessment.

The FNO learns the space–time solution operator, mapping functional inputs (topography, rheology, and initial conditions) directly to and . Conditioned on both geometry and physical parameters, it generalizes across parameter space and profiles, acting as a site-specific digital twin of the numerical solver rather than a generic emulator.

Accordingly, the surrogate is not a universal debris-flow model but a local operator trained on data representative of a specific catchment or similar basins. Its accuracy depends on the quality and coverage of the training data, and it is expected to generalize only within the sampled geometric and physical distributions; extrapolation beyond them is unreliable, reflecting a common limitation of deep learning models.

At the same time, we explicitly acknowledge that a surrogate trained on synthetic simulations learns the numerical solver’s input–output mapping rather than the physics directly. This is a deliberate choice, as operator-learning methods require full space–time fields that are unavailable from field data. Since the training data come from a validated physics-based model, the learned operator remains a physically consistent representation of debris-flow dynamics and their parametric dependence. Although the surrogate model inherits the physics encoded in the numerical solver, it ultimately provides a new computational capability: access to solver-quality predictions at negligible marginal cost. This enables large-scale ensemble simulations, sensitivity analyses, and near-real-time hazard forecasting, tasks that traditional solvers struggle to perform efficiently even at modest spatial resolution.

Beyond applying an existing operator-learning architecture, we analyze how the training objective affects solution quality by comparing two loss functions with different weights on depth and velocity errors. While the standard formulation accurately reconstructs depth but poorly captures velocity, increasing the velocity weight significantly improves predictions of without degrading . This targeted reweighting is a methodological choice to enhance hazard-relevant performance.

If FNO demonstrates strong performance, our objective is to constructing location-specific surrogate models. Because each debris-flow catchment displays unique morphological, hydrological, and rheological signatures, we argue that dedicated operator learners trained on basin-specific synthetic datasets can deliver high-accuracy, site-adapted predictions. In this sense, the FNO surrogate acts as a lightweight, operational proxy for the numerical solver, tailored to a particular landscape and parameter regime. Ultimately, such models may supplement or replace conventional solvers in many practical applications, providing real-time forecasting and uncertainty quantification in data-scarce environments.

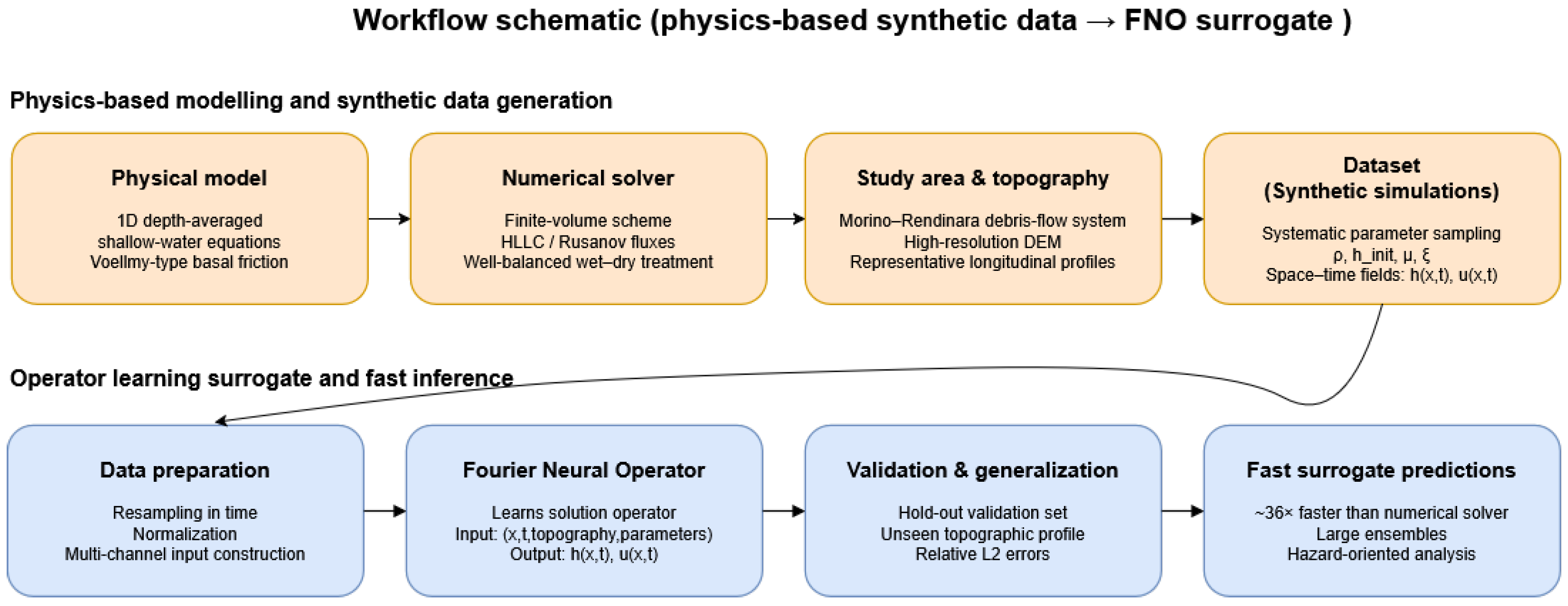

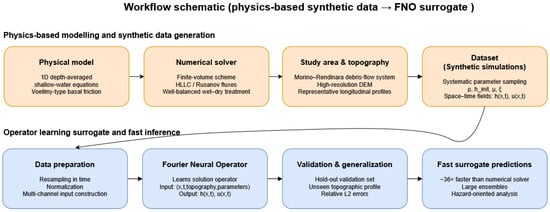

Figure 1 summarizes the workflow: topography and profiles are used to generate an ensemble of physics-based 1D debris-flow simulations by sampling key parameters; the outputs are assembled into a space–time dataset to train a Fourier Neural Operator. The trained FNO then rapidly predicts flow depth and velocity fields. The figure provides a high-level view that complements the detailed model and architecture described later.

Figure 1.

High-resolution simulations generate a synthetic dataset from sampled parameters, which is used to train a Fourier Neural Operator. Validated on unseen profiles, the trained model provides fast surrogate predictions (up to ∼36× faster) for large-ensemble hazard analyses.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the governing equations and Section 3 the numerical solver. Section 4 describes the synthetic dataset generation. Section 5 introduces the Fourier Neural Operator architecture and training strategy. Section 6 reports model performance, while Section 7 discusses implications and limitations. Finally, Section 8 summarizes the main findings.

2. Physical Model: One-Dimensional Governing Equations for Debris-Flow Modelling

Debris flows travelling along confined channels can be effectively represented using depth-averaged one-dimensional shallow-flow equations [1,2]. The formulation follows from the integral balance of mass and momentum under the standard assumption that vertical accelerations are negligible and hydrostatic pressure dominates [16]. The flow state is described by the depth and the depth-averaged velocity , collected in the conservative variables

The governing equations take the conservative form

where includes (i) hydrological inflow, (ii) gravitational forcing associated with bed topography, and (iii) basal resistance. Introducing an external inflow per unit channel length , the system becomes

with the bed elevation, the basal shear stress, and the flow bulk density. The gravitational forcing is expressed as , equivalent to for shallow slopes. Different rheological formulations may be used to evaluate , including Voellmy–Salm [32], Bingham, and Herschel–Bulkley models.

3. Numerical Solver: Finite-Volume Godunov Scheme

The governing equations are solved using a finite-volume Godunov scheme [17], equipped with well-balanced source-term discretization, basal friction, mixture-density diagnostics, and a robust treatment of wet–dry transitions. Two numerical fluxes are implemented: the HLLC approximate Riemann solver [34] and the Rusanov (local Lax–Friedrichs) flux [33,35].

3.1. HLLC Numerical Flux

Let and denote the left and right conservative states, with corresponding fluxes and . The HLLC flux is given by

where , , and denote estimates of the left, contact, and right wave speeds. The intermediate states are [17]

3.2. Rusanov Numerical Flux

The Rusanov flux [33], more dissipative but highly robust, is defined as

with

3.3. Well-Balanced Hydrostatic Reconstruction

To preserve the lake-at-rest steady state, the solver employs the hydrostatic reconstruction of [7].

The reconstructed depths at interface are

guaranteeing positivity and well-balancedness. The discretized bed-slope source term is

3.4. Treatment of Wet–Dry Transitions

Debris-flow propagation commonly involves advancing fronts, inundation of dry beds, and deposition. Since the shallow-flow system degenerates as , a positivity-preserving strategy is used. A cell is classified as dry when , in which case

For shallow but non-dry cells,

the depth is retained while the velocity is set to zero. At interfaces where both reconstructed depths satisfy

the numerical flux is set to zero. If only one side is dry, it is replaced by before flux evaluation. This treatment ensures positivity and avoids unphysical oscillations.

3.5. Diagnostic Bulk Density

Although the Voellmy–Salm rheology does not require the mixture density explicitly, a diagnostic field is computed from the water, coarse-solid, and fine-solid volume fractions:

The resulting values are bounded within user-defined physical limits,

3.6. Voellmy–Salm Basal Friction

Basal resistance is modelled through the classical Voellmy–Salm rheology [32], combining Coulomb friction and a turbulent drag term:

The resulting source term is

3.7. Temporal and Spatial Accuracy

The solver is first-order accurate in space, using piecewise-constant reconstructions, and first-order accurate in time through explicit Euler integration:

3.8. CFL Condition

The time step satisfies the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy (CFL) condition,

Our solver uses a default time step of and . For long profiles of about , the resulting CFL number is approximately , which is extremely conservative from a numerical standpoint. Such a low CFL value ensures strong numerical stability and significantly reduces the risk of spurious oscillations or divergence, although it may lead to higher computational cost.

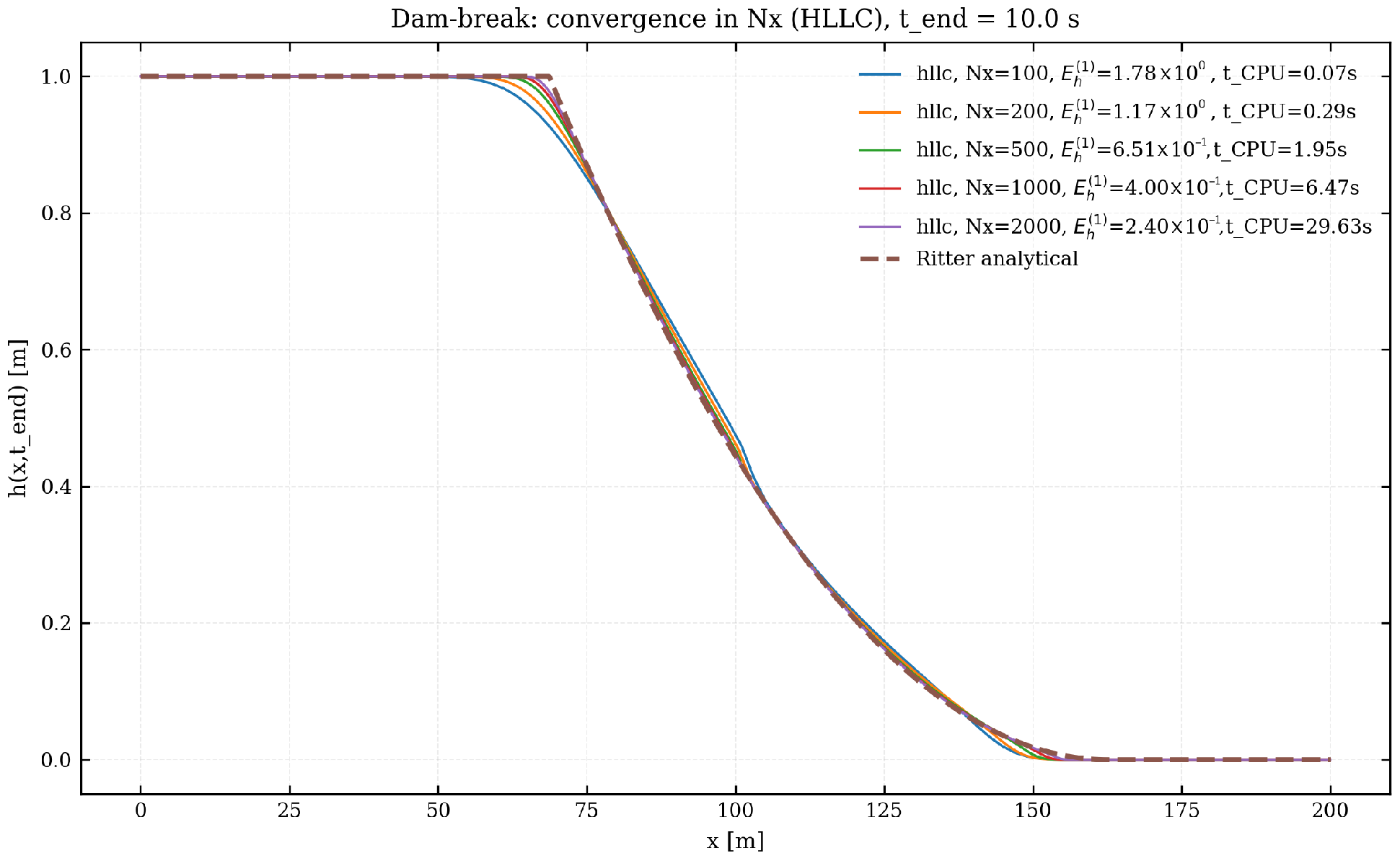

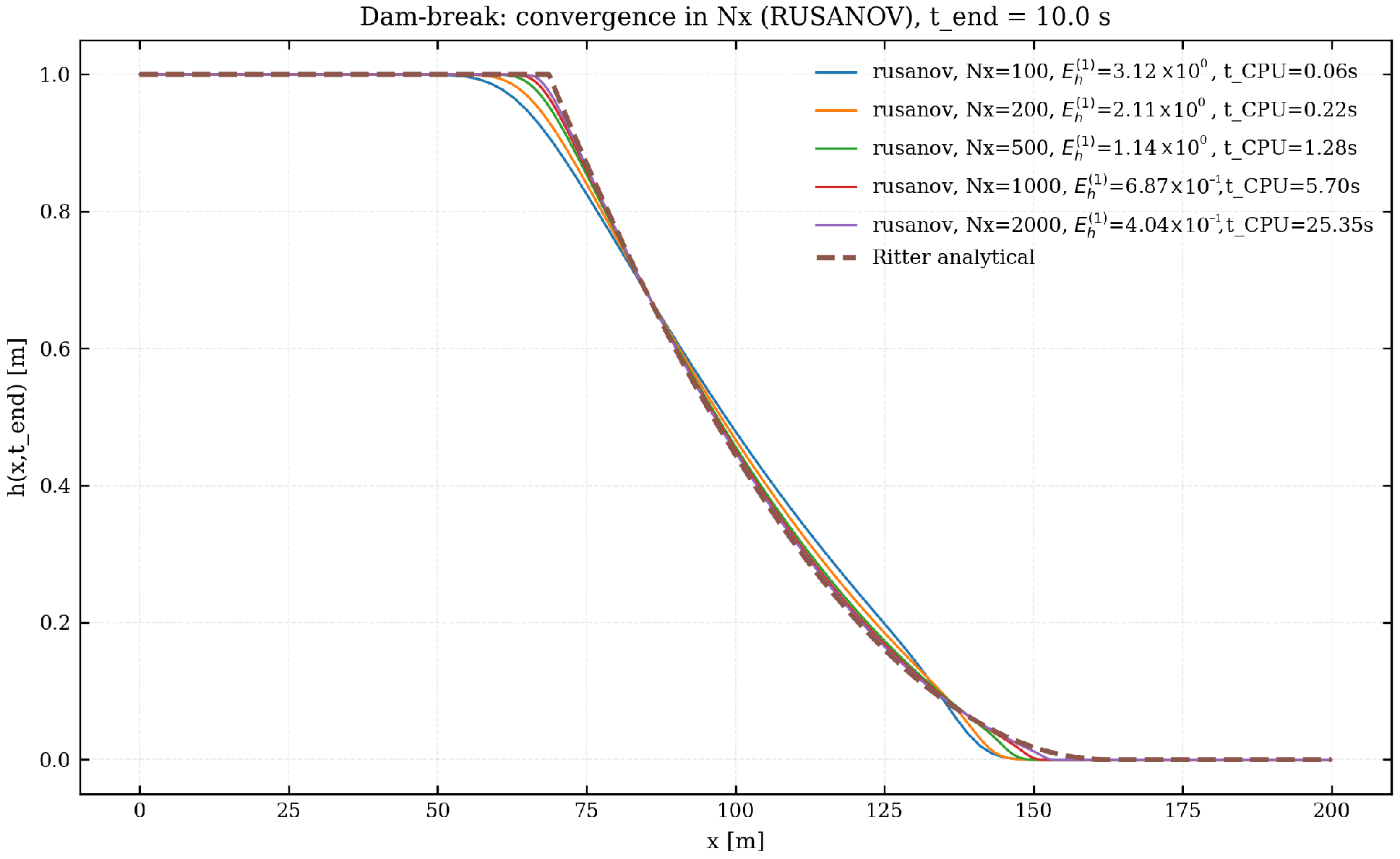

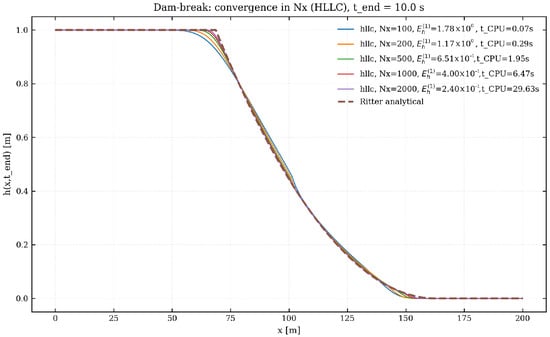

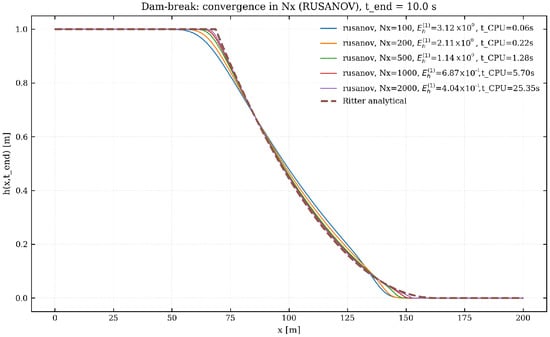

3.9. Validation of the Numerical Solver: Dam-Break Test Against Ritter’s Analytical Solution

The numerical solver is validated through a classical one-dimensional benchmark test for the shallow-water equations: the dam-break problem over a flat bed, for which Ritter’s analytical similarity solution is available [36]. The test is performed by varying the spatial resolution . A first-order finite-volume scheme is employed, with numerical fluxes computed using either the Rusanov or the HLLC approximate Riemann solver. Time integration is carried out using an explicit forward–Euler method, with the time step automatically constrained by the CFL stability condition.

Whenever bed slopes are involved, the hydrostatic reconstruction is employed to maintain non-negativity of the water depth and to improve the balance between flux and source terms near wet–dry interfaces.

The numerical error is quantified exclusively through the norm [37], which provides a robust global measure of accuracy, especially in the presence of discontinuities such as rarefaction fans and moving wet–dry fronts.

The benchmark verifies the shock-capturing capability of the solver through a classical dam-break over a flat bed.

Friction, rheology, bed evolution and internal viscosity are disabled so that the flow is governed solely by the frictionless shallow-water equations.

The numerical solution at a prescribed comparison time is sampled on the computational grid and compared with the analytical profiles through the error in water depth:

Figure 2 and Figure 3 report the water-depth profiles at s for the same set of grid resolutions and for both flux functions. The analytical solution is shown as a dashed line, while the legends list, for each , the corresponding error and CPU time.

Figure 2.

Dam-break test with HLLC flux. Water-depth profiles at s for . The dashed line corresponds to Ritter’s analytical solution.

Figure 3.

Dam-break test with Rusanov flux. Water-depth profiles at s. The dashed line corresponds to Ritter’s analytical solution.

The results exhibit a clear first-order convergence trend: refining leads to a proportional reduction of , and the numerical profiles approach the analytical solution as expected. The HLLC flux produces slightly sharper rarefaction waves than Rusanov, whereas the latter is marginally more diffusive but somewhat cheaper in terms of CPU time. In all cases, the wet–dry front is captured without spurious oscillations.

The validation campaign shows that the implemented first-order finite-volume solver accurately reproduces the dam-break dynamics described by Ritter’s analytical solution and exhibits the expected first-order convergence under spatial refinement, while maintaining a linear CPU-time scaling with the number of grid cells. The comparison between flux functions confirms that the HLLC scheme is less diffusive than Rusanov, yet comparably stable. These results demonstrate that the solver behaves consistently with the theoretical properties of first-order shallow-water finite-volume schemes and provides a reliable baseline for debris-flow modelling. Given this validation, the solver is considered sufficiently accurate and robust to generate the synthetic dataset used in Section 4.

4. Study Area and Synthetic Dataset

This section presents the characterisation of the Morino–Rendinara area, which we aim to represent using the FNO model. The objective is to describe the geomorphological and physical attributes of this debris-flow system in a form suitable for integration within an FNO framework.

Building on this characterisation, we then describe the procedure used to construct the synthetic dataset for model training. This involves defining the relevant parameter space and implementing the numerical framework required to generate the 1D simulations. By capturing the key physical controls and the spatial heterogeneity of the Morino–Rendinara environment, the resulting synthetic dataset provides a representation of the system. This ensures that the FNO model is trained on scenarios that preserve the underlying geomorphological complexity while enabling efficient learning of the processes governing debris-flow initiation and propagation.

4.1. Geographic Zone: The Morino–Rendinara Debris–Flow System

The synthetic dataset developed in this work is inspired by the debris–flow event that occurred in March 2021 in the Morino–Rendinara area (Abruzzo Region, central Italy), along the Rio Sonno channel, a tributary of the Liri River [4]. The study area is located near the hamlet of Rendinara, within the Municipality of Morino, in the upper part of the Roveto Valley on the eastern side of the Liri River valley [4]. The valley is mainly characterised by Messinian siliciclastic deposits, locally overlain by fractured carbonate rock masses; intense fracturing and meteoric erosion have led to the accumulation of extensive slope debris, deeply incised by the present-day drainage network [4].

The landslide system feeding the debris flow reaches a maximum length of about 900 m, with a head zone at approximately 850 m a.s.l. and a toe at about 403 m a.s.l. near the Liri River [4]. Upstream, the instability is controlled by a highly fractured carbonate aquifer that feeds numerous high–discharge springs located at the contact with underlying clayey formations. The resulting water supply strongly influences the saturation state of the fine–grained sediments, favouring the triggering and persistence of debris–flow conditions within the Rio Sonno channel [4]. During the March 2021 event, several thousand cubic metres of material were mobilised, partially obstructing the Liri riverbed and temporarily altering the local hydrogeological regime [4].

In the back–analysis [4] the Morino–Rendinara debris flow was simulated using the RAMMS v1.5 software, based on a Shallow–Water formulation coupled with a Voellmy–type rheological model. The calibration relied on field evidence of the runout path and of the accumulated thickness near the confluence between Rio Sonno and the Liri River, together with parametric variations of the main physical and rheological parameters (density, released volume, and Voellmy friction coefficients) [4].

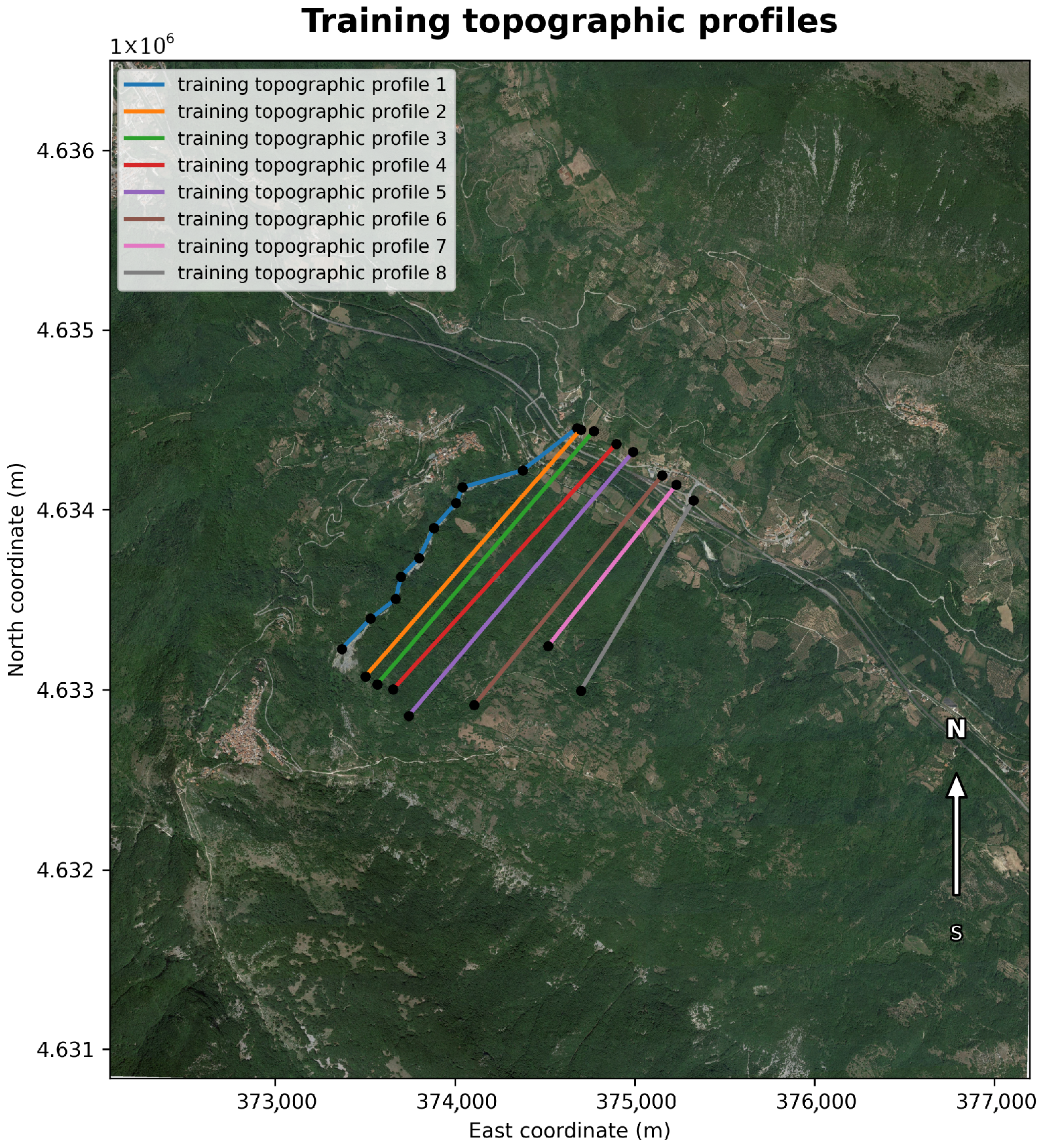

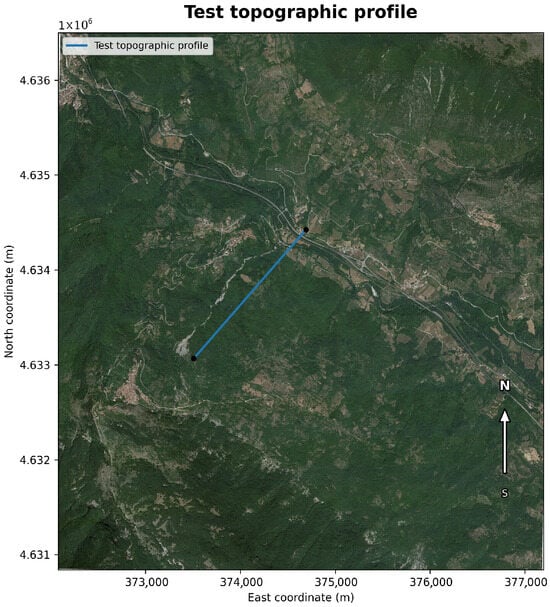

4.2. Dataset Parameter Space and Numerical Setup

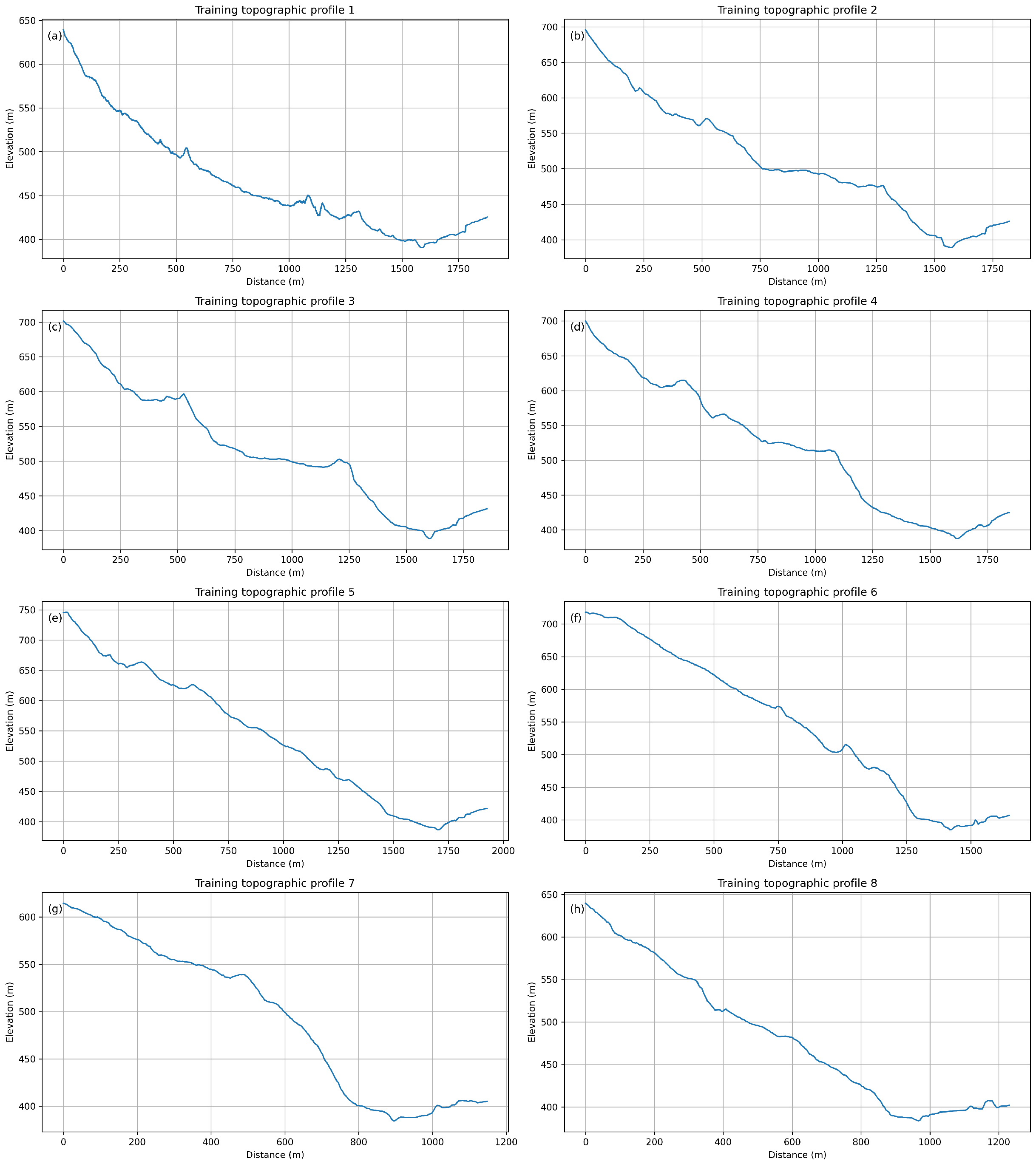

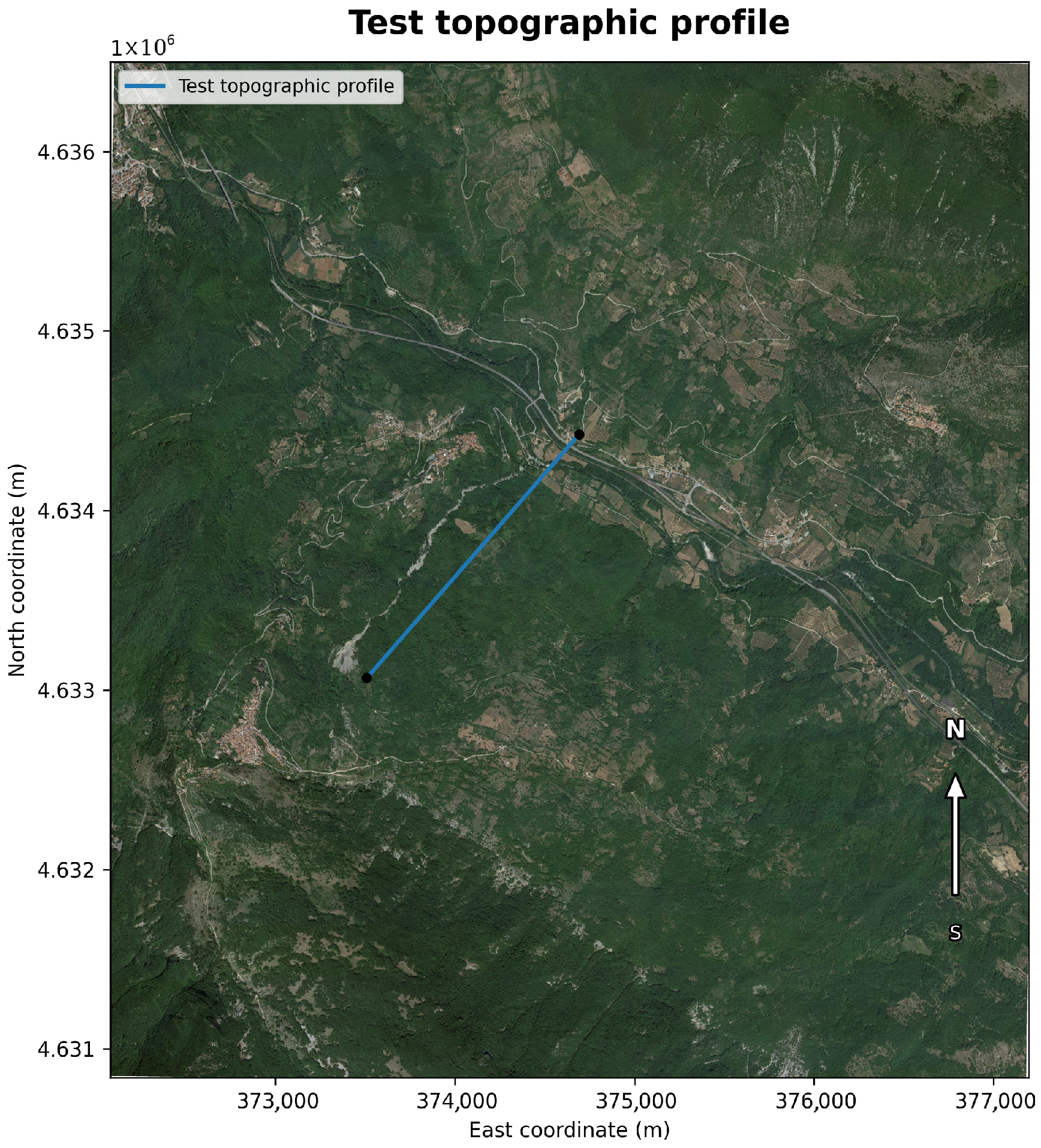

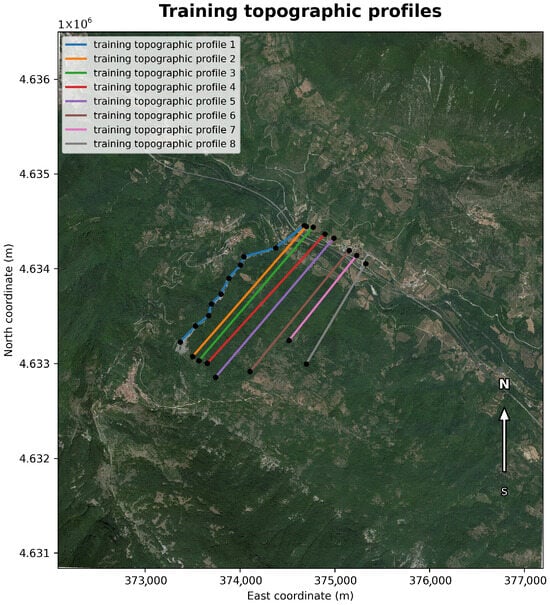

The 1D dataset used in this work is constructed by means of a depth–averaged Shallow–Water debris–flow solver explained before, applied to a set of synthetic longitudinal profiles representative of the Rio Sonno channel (profile 1 in Figure 4) and its surroundings. Eight longitudinal topographic profiles were extracted from the high–resolution DEM and orthophoto of the Morino–Rendinara area, in order to reproduce representative sections of the debris–flow path and adjacent slopes. These profiles sample a range of slope gradients and morphological conditions encountered along the debris–flow system.

Figure 4.

Locations of the eight topographic profiles used in the numerical simulations, traced over the orthophoto and DEM of the Morino–Rendinara debris–flow system. The blue profile (profile 1) represents the Rio Sonno channel. The colour code identifies the eight transects. Black dots mark the profile endpoints, and the north orientation is indicated on the right.

The orthophoto and 5 m–resolution DEM were obtained from the Abruzzo Regional Geoportal and derived from airborne LiDAR data.

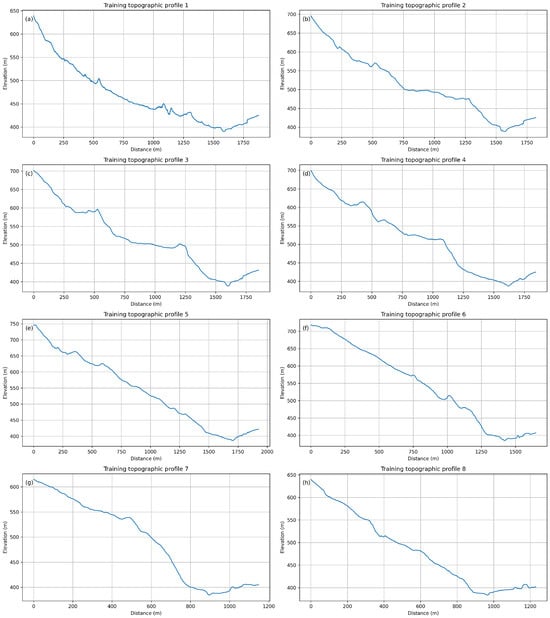

Figure 4 shows the location of the eight profiles on the orthophoto and DEM, while Figure 5 presents the extracted profiles as separate subfigures for clear visualization of channel geometry and longitudinal morphology.

Figure 5.

Training topographic profiles used to generate the synthetic dataset, shown as separate subfigures (a–h). Each panel shows bed elevation along the transect; separate display highlights channel geometry, slope variations, and local morphological features.

The initial conditions and rheological parameter ranges are chosen to be consistent with the values adopted in the back-analysis of the Morino–Rendinara event [4]. In particular:

- Bulk density of the mixture: , is sampled uniformly in the interval , in accordance with the two density levels (1200 and 1300 kg/m3) tested in their simulations [4].

- Released volume/initial thickness: Pasculli et al. consider released volumes of 100 and 200 m3 [4]. In the 1D solver, the parameter spans values uniformly distributed in m, and is thus tuned to produce 1D volumes that are consistent, in order of magnitude, with the 2D released masses reported in Pasculli et al. [4]. While denotes the global initial thickness parameter controlling the total released volume in each simulation, represents the spatially distributed initial thickness field provided by the numerical solver.

- Voellmy friction parameters: The dry (Coulomb-type) friction coefficient and the viscous–turbulent coefficient are varied coherently with the ranges suggested for simulations of granular (solid-like) and earth-flow (fluid-like) behaviour [4]. Specifically, is sampled in , while is drawn from the interval m/s2 for granular flows and m/s2 for earth-flow-type behaviour, as reported in Pasculli et al. [4].

Initial conditions are controlled via and , while boundary conditions are fixed and inherited from the numerical solver. Open boundaries with ghost-cell extrapolation are used, no external inflow is prescribed, and well-balanced and positivity-preserving treatments are applied. Accordingly, the FNO learns the solution operator under the solver’s boundary-condition regime, implicitly encoded in the training data.

The complete parameter space adopted for the synthetic dataset generation are summarised in Table 1, providing a clear overview of the material properties, rheological parameters, and the associated initial and boundary conditions.

Table 1.

Parameter space used to generate the synthetic debris-flow dataset, with ranges chosen to be physically representative of the Morino–Rendinara system and consistent with the March 2021 back-analysis [4].

The solver outputs, for each run, the arrays t, x, h, u, and (time, position, flow depth, depth-averaged velocity, and bed elevation). These fields are resampled in time with a fixed sampling interval s (during simulation was 0.1 s). Let be the number of equally spaced nodes and the number of resampled time instants; after transposition to , the following 2D fields are constructed:

- constant parameter fields: x, t, , , , and all spatially and temporally uniform over the entire computational domain for each profile).

- dynamic fields: bed elevation and .

All fields are stacked along a “channel” dimension, resulting in a multi-channel array of shape

where is the number of stored variables (constant parameters plus dynamic fields). Finally, after shuffling the list of all successful simulations, the dataset was split into training and validation subsets by assigning a fixed fraction of the simulations to validation. The dataset creation phase produced a total of 1298 samples, of which 1038 were used for training and 260 for validation, corresponding to the commonly adopted 80–20% split in machine learning workflows.

Table 2 provides the numerical setup, discretisation, temporal sampling, and dataset characteristics used to build the multi-channel space–time tensors employed for training and validation.

Table 2.

Numerical setup, discretisation, temporal sampling, and dataset characteristics used for training and validation of the Fourier Neural Operator (FNO).

The complete process of data generation, simulation, and storage required 3 h and 34 min. All operations were carried out on an HP Laptop 15s-eq3xxx (HP Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) equipped with an AMD Ryzen 5 5625U (2.30 GHz) processor, 8 GB of RAM, a 64-bit operating system, and integrated Radeon graphics.

5. Fourier Neural Operator

This section presents the Fourier Neural Operator (FNO) adopted as a data-driven surrogate for the one-dimensional shallow-water debris-flow simulations described in Section 4.

5.1. Mathematical Formulation of the Fourier Neural Operator

Neural operators (NOs) are a family of machine learning models designed to approximate operators mapping one function space into another [24]. They learn parametric approximations of infinite-dimensional operators

based on discrete training pairs , while maintaining a mesh-independent behavior [31].

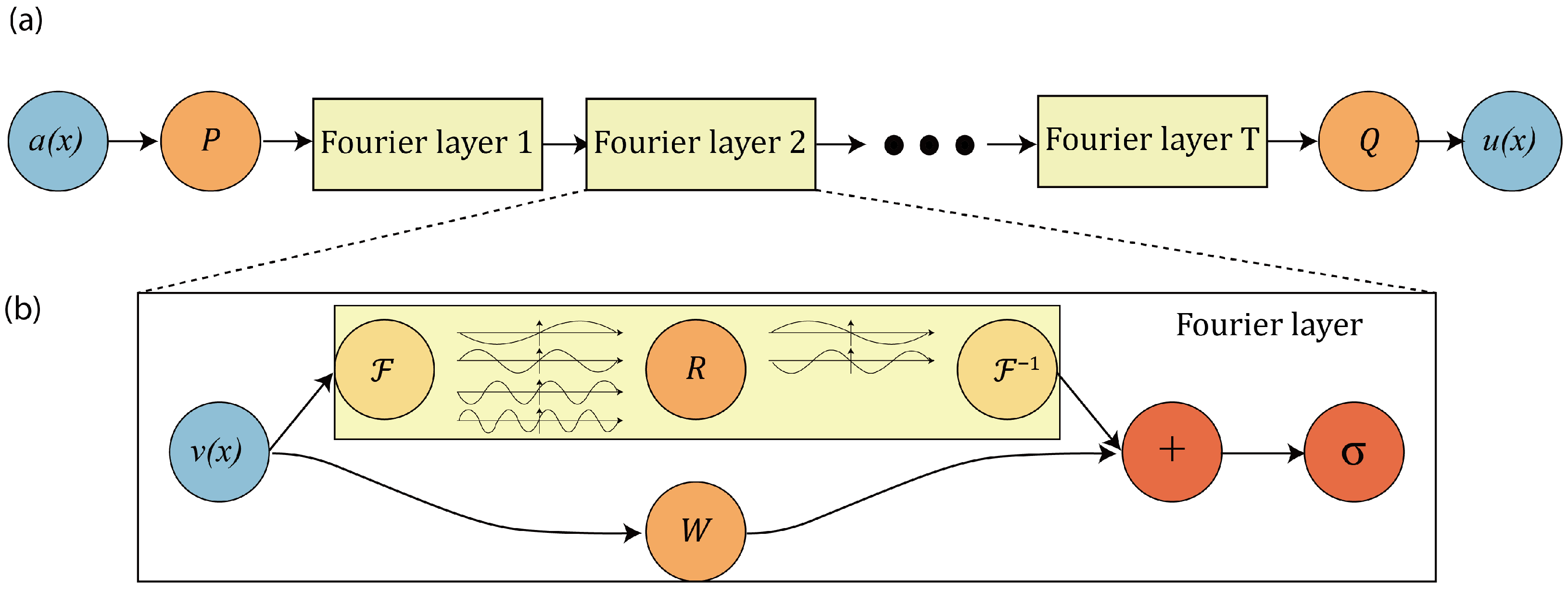

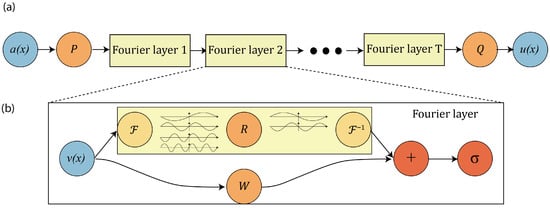

Among these models, the Fourier Neural Operator (FNO) is particularly effective for PDEs because it captures long-range interactions through spectral convolutions computed in Fourier space [29]. Before introducing the detailed mathematics, it is useful to examine the general architecture.

Figure 6 illustrates the structure of the FNO. Panel (a) shows the overall pipeline: the input function is first lifted to a higher-dimensional latent representation through a pointwise linear operator P. It then flows through a sequence of T Fourier layers, each responsible for mixing information globally across the domain, and finally the output field is obtained by a projection Q back to physical space. This pipeline corresponds conceptually to learning the operator .

Figure 6.

(a) Architecture of the Fourier Neural Operator: the input field is lifted to a latent representation via P, propagated through T Fourier layers, and projected back to obtain the output through Q [29]. (b) Internal structure of a Fourier layer: Fourier transform , learned spectral weights R, inverse transform , pointwise linear map W, and activation . The spectral pathway models nonlocal interactions while W accounts for local effects [29].

Panel (b) zooms into the internal structure of a single Fourier layer: The input field is first decomposed into Fourier modes via , which correspond to the sinusoidal components illustrated in the figure. These modes are then modified by the learned spectral multiplier R, acting only on the low-frequency coefficients (represented by the colored central block). After the inverse transform , this global interaction is combined with a local linear transformation (the bypass arrow in the figure), and the result passes through a nonlinear activation . In this way the diagram visually captures the combined local–nonlocal structure of the FNO update rule.

5.2. Training Procedure and Model Optimization

The Fourier Neural Operator is trained using standard gradient–based optimization. All components of the architecture, including the two–dimensional Fourier transform, spectral multipliers, pointwise linear operators, and nonlinear activations, are fully differentiable and therefore compatible with automatic differentiation. Although Figure 6 depicts only the forward propagation through the lifting layer, the sequence of Fourier layers, and the projection layer, the backward pass mirrors the same structure in reverse, allowing gradients to flow through every element of the computational graph.

Each sample is defined on a two–dimensional grid and is stored on disk in a non–normalized format containing the physical fields

From these raw quantities, an input tensor of shape is constructed, which is fully normalized before being passed to the network.

The definition and normalisation of each input channel are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Definition and normalisation of the eight input channels forming the FNO input tensor of shape .

Hence, all inputs reaching the model are already normalized and share a comparable dynamic range.

The target variables are the physical flow depth and velocity, and . Unlike the inputs, these are not min–max scaled; instead, they are standardized via global statistics computed exclusively on the training set. Let , and , denote the mean and standard deviation of h and u, the dataset converts the physical targets to normalized variables

The network is trained to predict the pair at all space–time locations; physical fields are reconstructed at inference time (and within the loss) through the inverse standardization.

Given a normalized input field and the corresponding normalized target , the FNO model maps a to a latent representation via a fully connected lifting layer P, propagates it through T Fourier layers, and finally projects it back to the two–channel output space through a projection operator Q:

The latent width is fixed to 128 channels in all layers, and we use Fourier blocks, as specified in the configuration layers: [64, 64, 64, 64, 64]. For each Fourier block , a spectral convolution acts on a truncated set of low–frequency modes

corresponding to modes 1: [8, 16, 16, 32, 32] and modes 2: [4, 4, 4, 4, 4]. Each spectral convolution is complemented by a convolution in physical space and a GELU activation, except for the last block.

Following standard FNO practice [38,39], only a limited number of low-frequency Fourier modes (typically 8–32 per dimension) are retained, ensuring stability and efficiency while capturing the large-scale dynamics that dominate the physical behavior.

To mitigate boundary effects, the latent field is padded by 15 cells in space and 30 time steps using replicate padding before the Fourier transform, and cropped back to the original domain at the end of the network.

The discrepancy between prediction and ground truth is measured in physical units by a specialized loss function. Given predicted and reference normalized fields and , the routine first denormalizes both to obtain the physical fields and through the stored statistics . A relative loss is then computed separately for depth and velocity:

Explicitly

These normalized relative errors for depth and velocity are those analysed in Section 6.1.1.

The overall objective function is constructed as a weighted combination of multiple error terms in order to guide the training toward an accurate approximation of the underlying operator. In particular, the data loss is defined as

where and measure the errors in h and u, and , set their relative importance. Adjusting these weights prioritizes the reduction of specific components, allowing the FNO to learn a multi-output operator with a controlled trade-off between individual variable accuracy and overall performance. By evaluating the loss in physical space rather than on normalized variables, the optimization directly targets discrepancies in meaningful physical units.

The gradient of the loss with respect to all trainable parameters is computed through reverse–mode automatic differentiation. Here, P denotes a linear lifting operator that maps the input fields to a higher–dimensional feature space, Q is a linear projection (readout) operator that maps the final feature representation back to the output space, is the pointwise linear operator in the k-th Fourier layer acting in the physical domain, and collects the learnable spectral multipliers (Fourier-domain weights) of the k-th Fourier layer. During backpropagation, the error signal travels through each Fourier layer in reverse, crossing the nonlinear activation, the pointwise operator, the inverse and forward Fourier transforms, and the spectral multipliers [29]. The parameters are updated using a custom Adam optimizer with learning rate . The optimization follows a mini–batch stochastic procedure. At each epoch, the training set is iterated with a batch size of 10; for every mini–batch, normalized inputs are propagated through the network, the predictions are denormalized to physical space, the loss is evaluated, and gradients are propagated through the entire architecture before performing a parameter update. Validation is carried out every five epochs on a separate dataset using a batch size of 1.

Every model (baseline and reweighted) was trained for 50 epochs, requiring a total of 6 h and 25 min. The training was executed entirely on the same system configuration used for dataset creation. Model selection is based on the relative error for the flow depth h over the entire spatio–temporal domain, as defined in Equation (29). After each validation step, the checkpoint corresponding to the lowest validation error on h is stored as the best model. In addition, all random number generators were initialised with a fixed seed , ensuring full reproducibility of data shuffling, network initialisation, and optimisation.

For completeness and reproducibility, the full set of architectural choices and training hyperparameters adopted in this study is summarised in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of the Fourier Neural Operator (FNO) architecture, training hyperparameters, and optimisation setup adopted in this study. The reported values fully specify the network configuration and the learning procedure used to obtain the surrogate results presented in Section 6 and Section 7.

6. Results

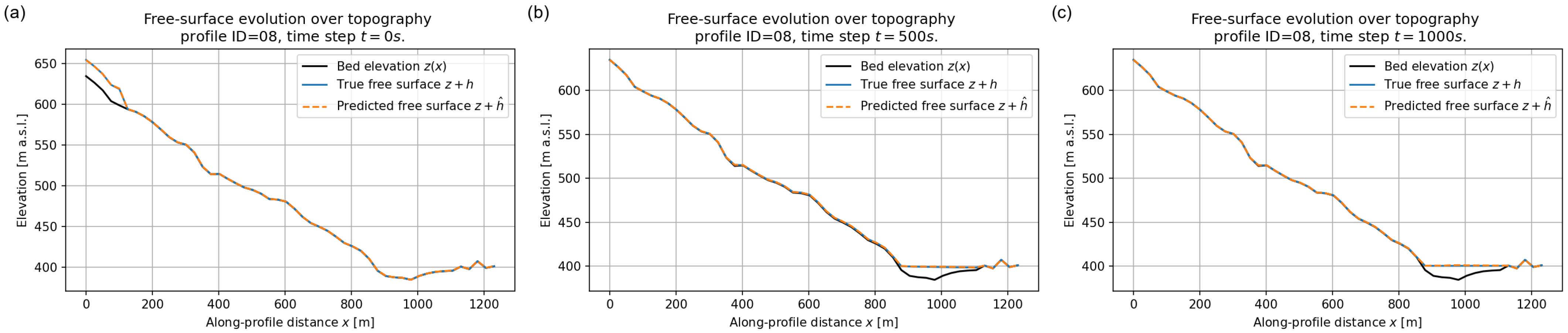

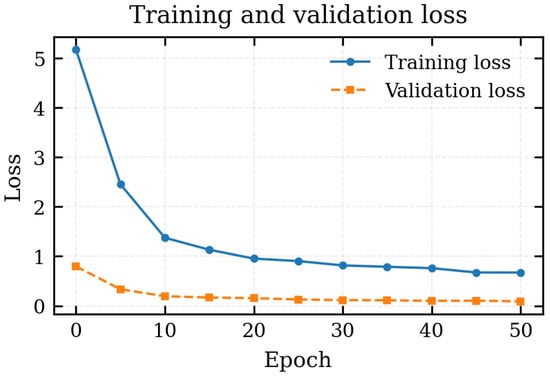

In this section we evaluate the behaviour of the Fourier Neural Operator (FNO) during training and its predictive accuracy on synthetic debris–flow simulations for two different training cases, one with and the other with , consistently with the data misfit formulation previously introduced in Equation (30), where and weight the contributions of flow depth and velocity, respectively. The larger value of is deliberately adopted to account for the greater difficulty encountered by the FNO in accurately learning the velocity field compared to the flow depth. We first analyse the learning dynamics and the evolution of the validation errors, and then discuss visual examples of the predicted spatio–temporal fields for flow depth, velocity and free surface. In the case , we therefore present only the results for the velocity u, since it is the only variable directly affected by the change in the weighting coefficient, whereas the depth component h is associated with the same weight and does not show appreciable differences. Finally, we show the generalisation capability of the model on an unseen test profile. Also in the case , only the velocity field u is reported, as the depth h is not influenced by the modified weighting and exhibits negligible variations, making it unnecessary for highlighting the differences.

6.1. Baseline Case: ,

6.1.1. Training Dynamics and Validation Errors

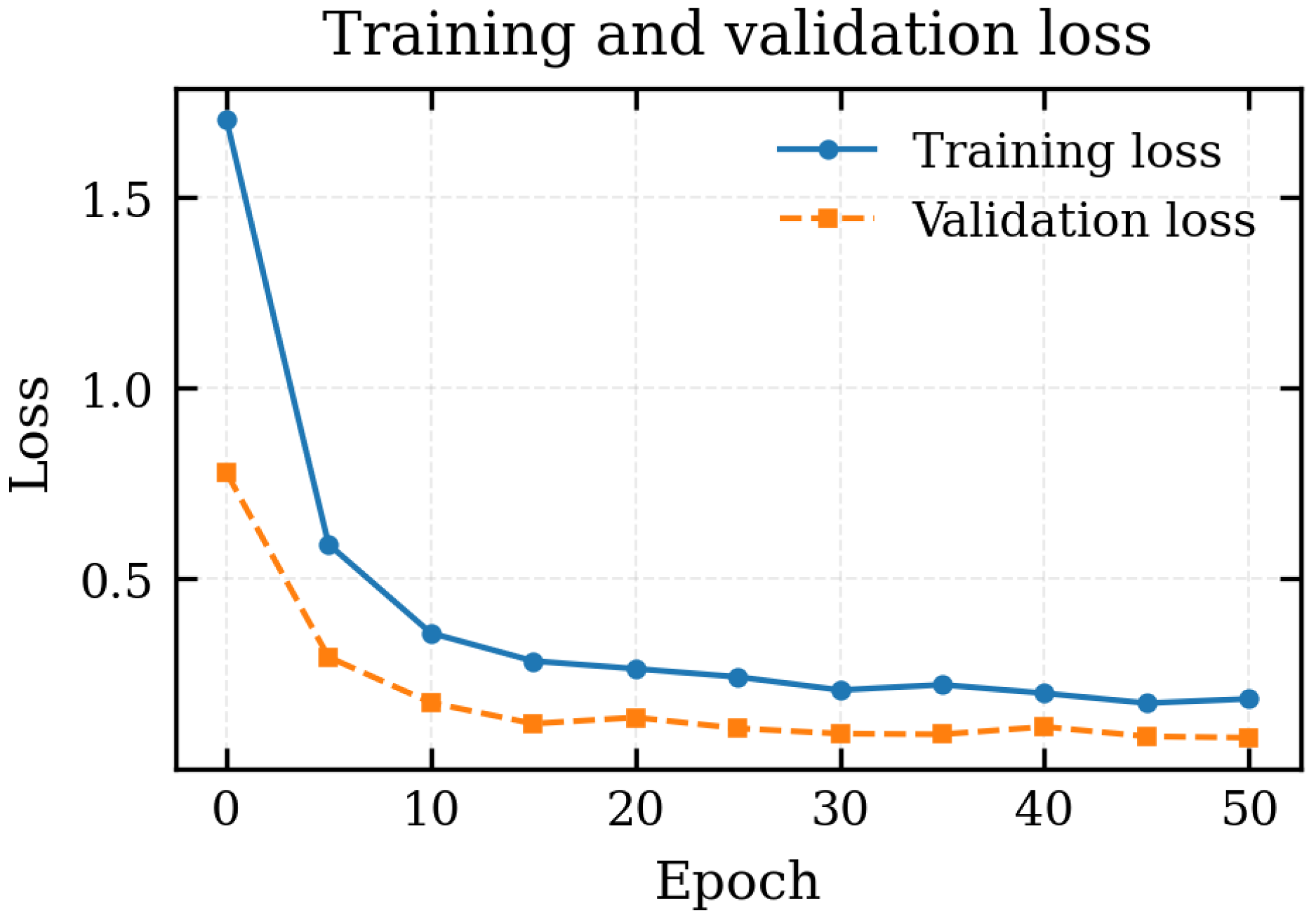

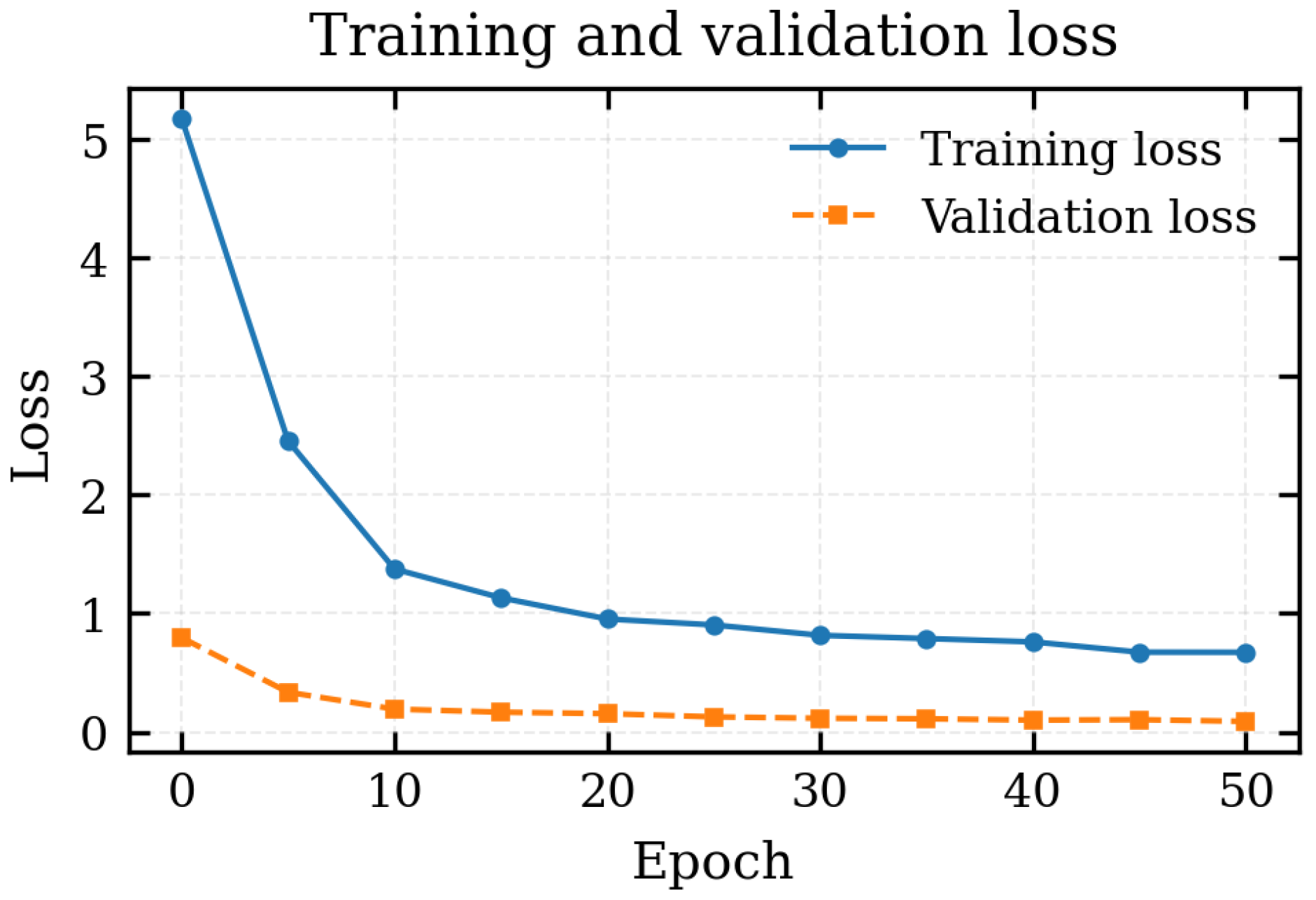

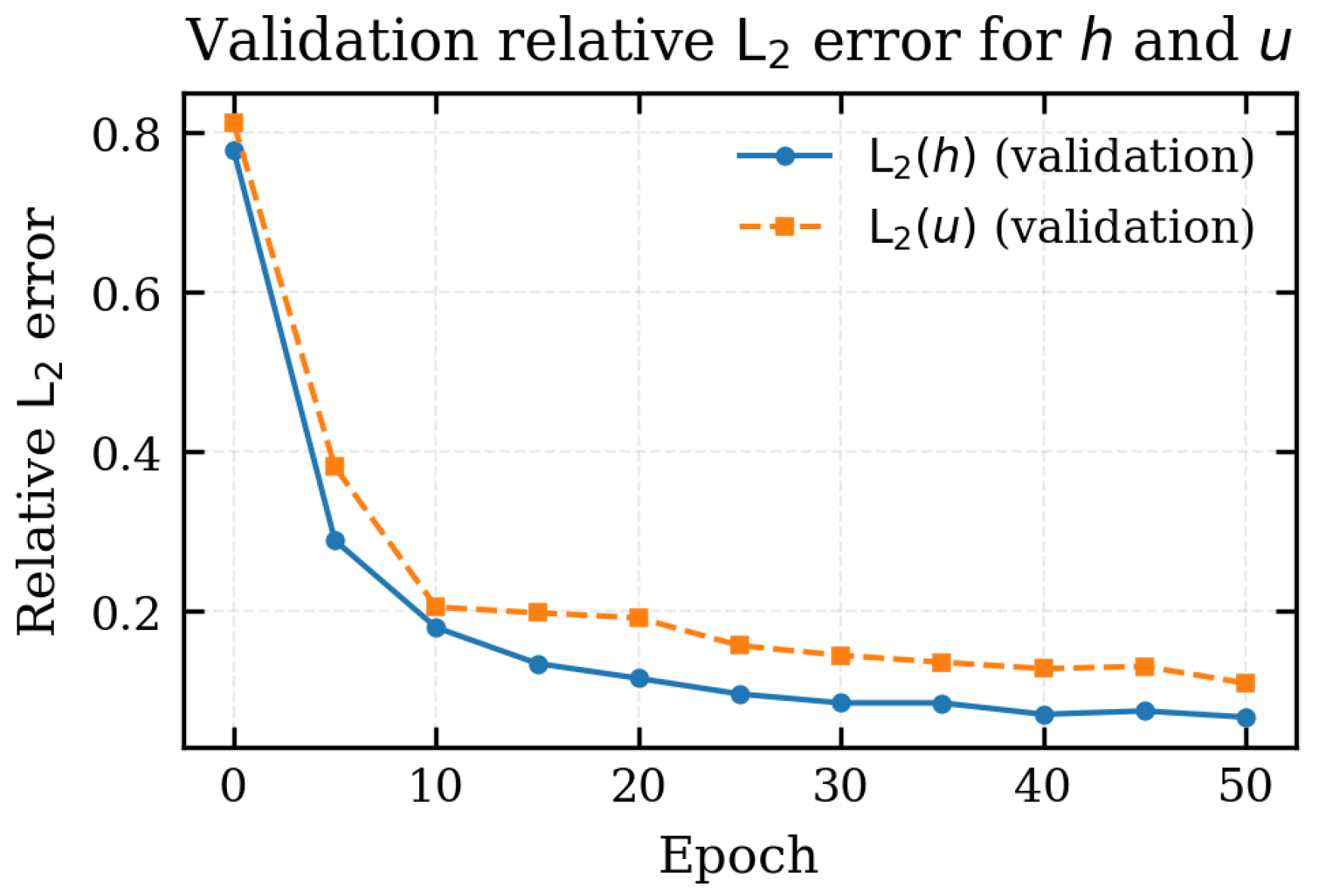

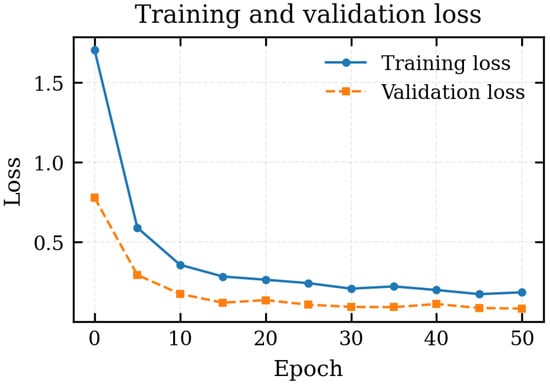

Figure 7 shows the evolution of the total training and validation loss as a function of the epoch. Both curves decrease rapidly during the first five epochs, with the validation loss dropping from approximately to . Afterwards the losses continue to decrease more gradually and reach a nearly flat regime after about 30 epochs, without any indication of overfitting. The modest gap between training and validation loss suggests good generalisation of the FNO to unseen simulations within the same parameter ranges.

Figure 7.

Total training and validation loss as a function of the epoch during FNO optimisation.

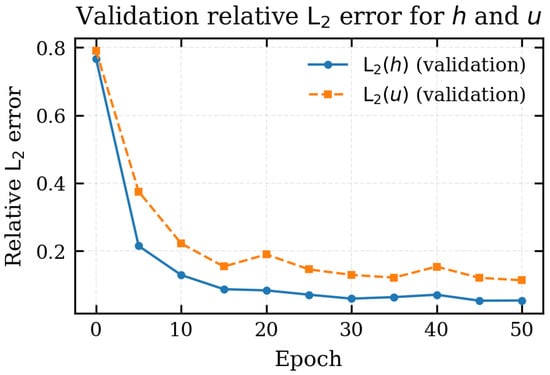

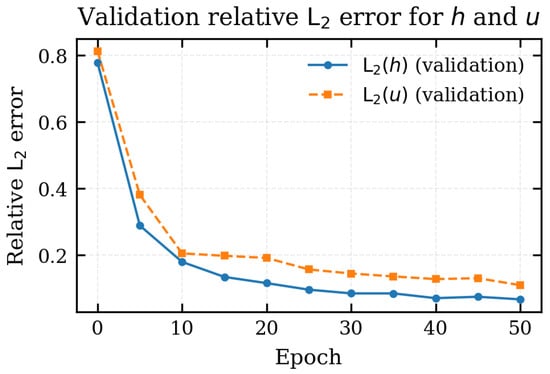

To disentangle the contributions of flow depth and velocity, Figure 8 reports the relative validation errors for h and u separately, computed over all spatial locations and times of the validation set according to the definitions in Equation (29). The norms are computed over all spatial locations and times of the validation set. The error on the flow depth decreases from about at epoch 0 to less than after 30 epochs, and eventually stabilises around . The velocity error is consistently larger but follows a similar trend, decreasing from roughly to values close to at the end of training. This confirms that the FNO attains very good accuracy on h, while the prediction of u remains more challenging. For the overall validation set, the relative errors are

Figure 8.

Relative validation errors for flow depth h and velocity u as a function of the epoch.

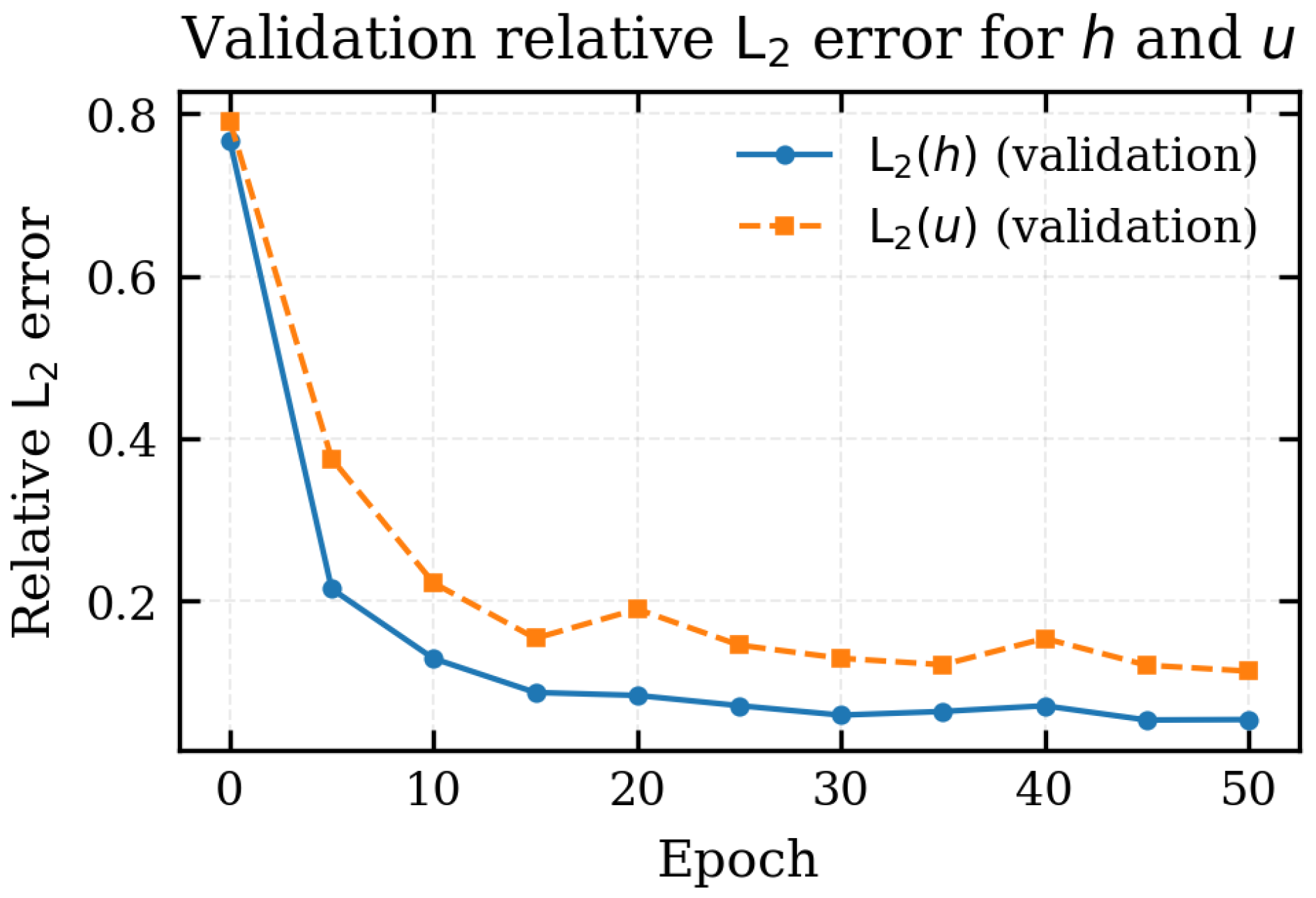

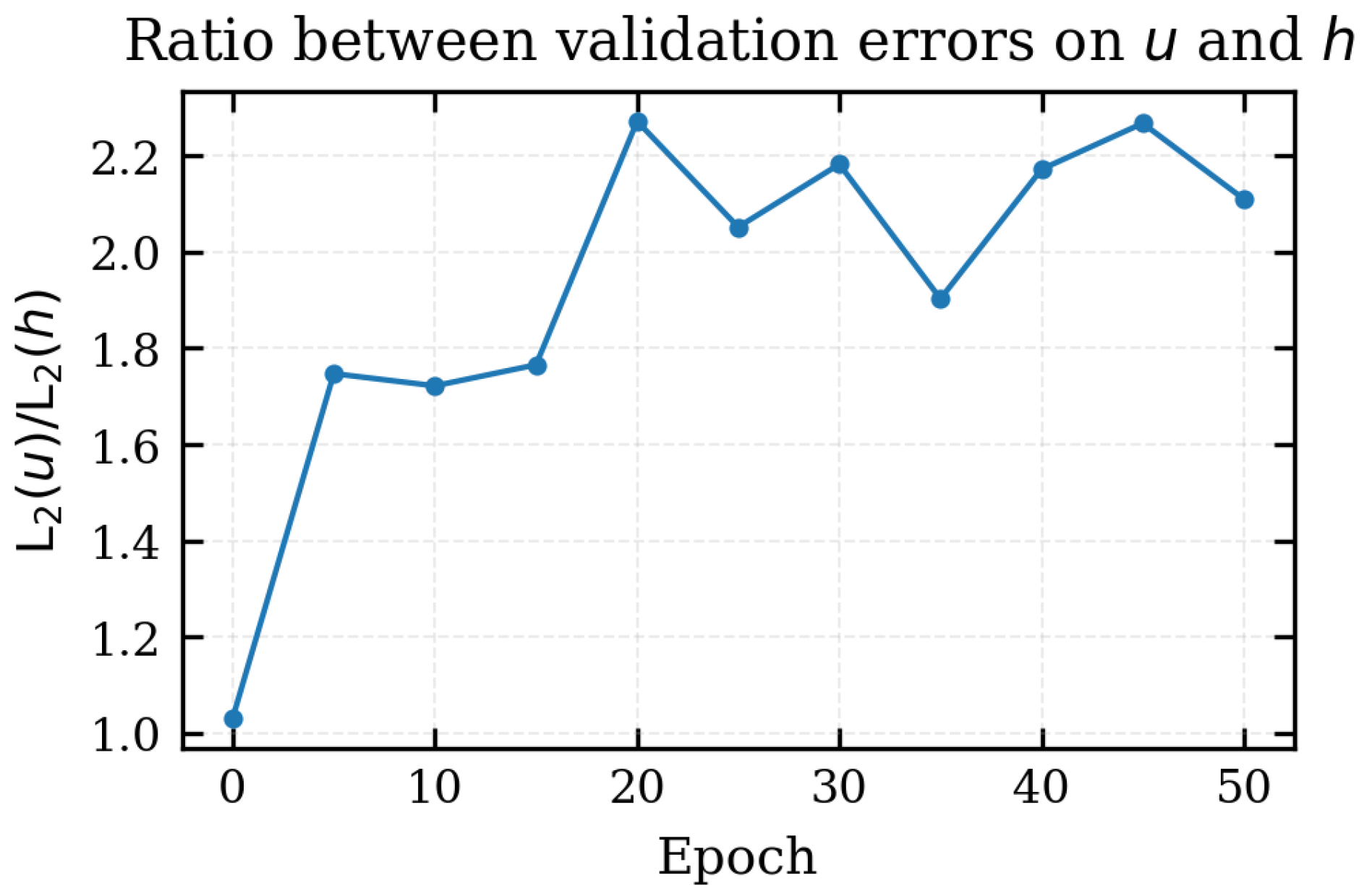

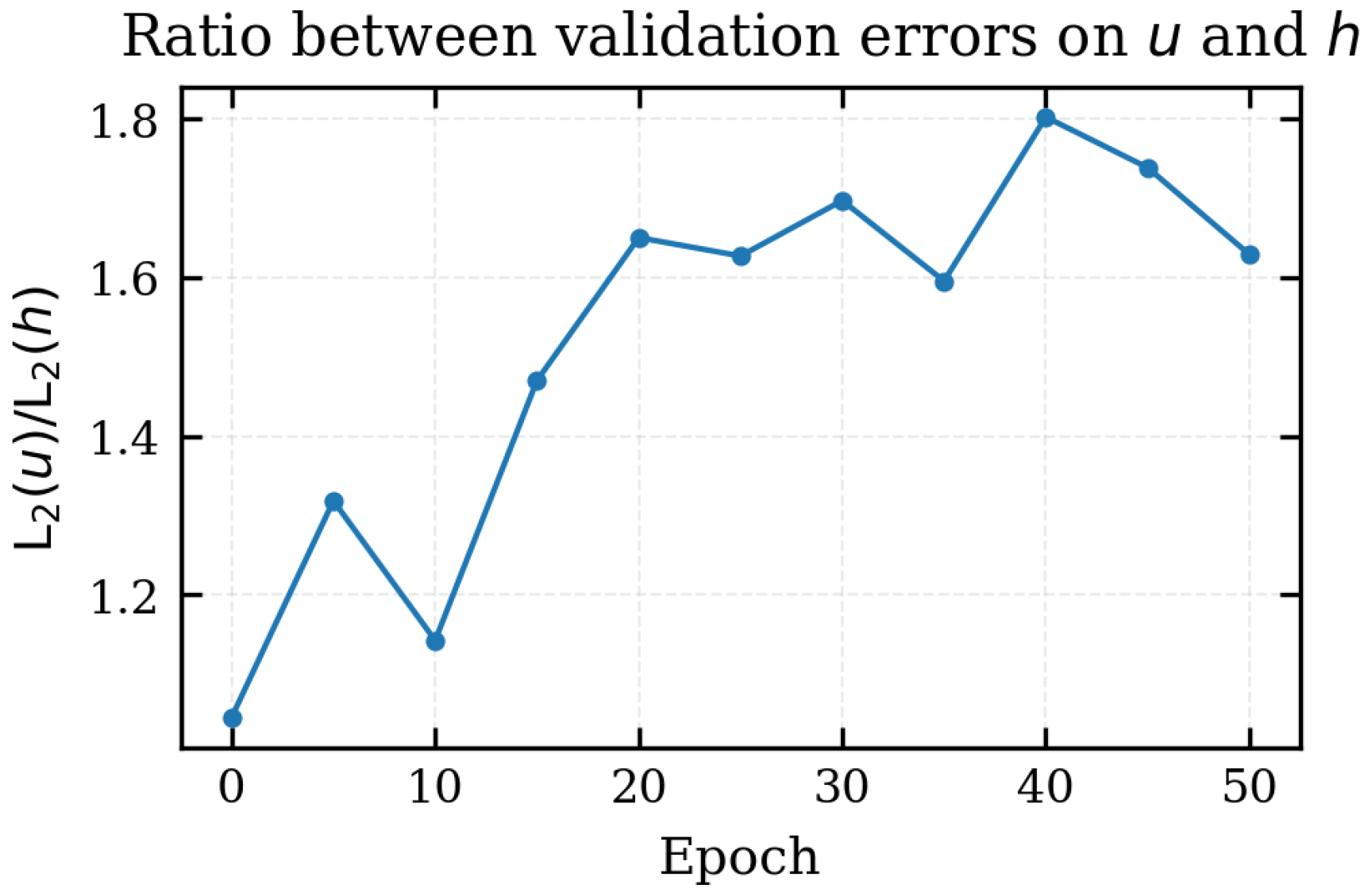

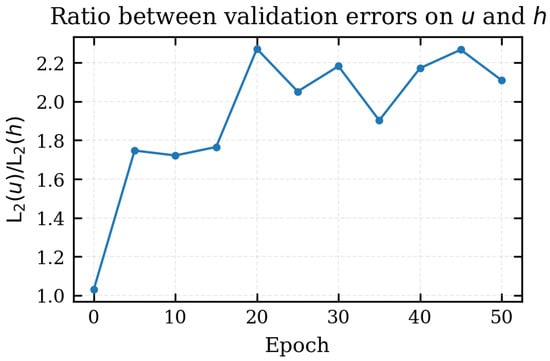

The systematic difference between the two fields is quantified in Figure 9, which plots the ratio

on the validation set. After an initial value close to unity at epoch 0, the ratio quickly increases and fluctuates between and for the remainder of the training. This behaviour reflects the fact that the FNO learns to reduce the error on h more aggressively than on u, so that, on average, the velocity predictions remain roughly twice as inaccurate as the depths in relative sense. This is physically reasonable: the velocity field is intrinsically more scattered and irregular than the flow depth, with sharper local gradients, sign changes and high–frequency oscillations, especially during rapid acceleration phases. Capturing these details is naturally more demanding for a spectral operator such as the FNO, and thus a larger error on u is expected.

Figure 9.

Ratio between the relative validation errors on velocity and depth, , as a function of the epoch.

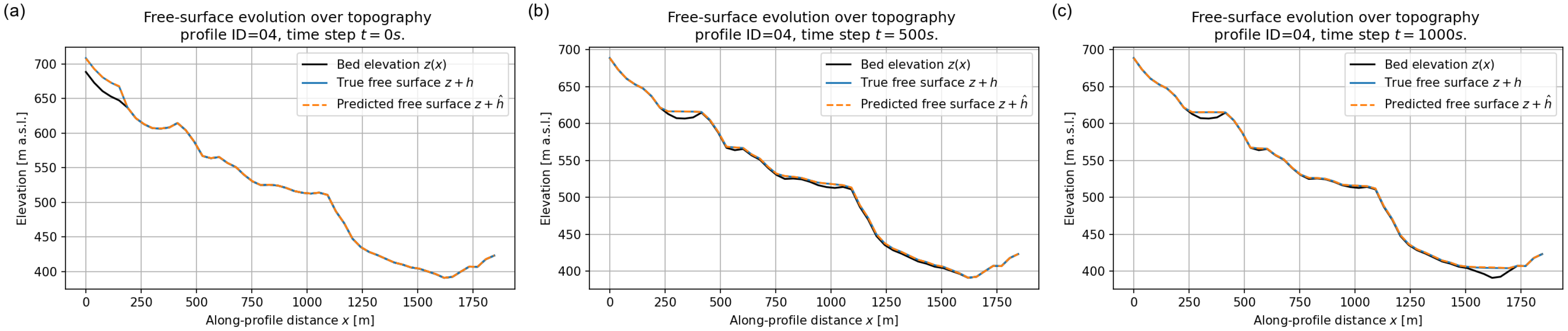

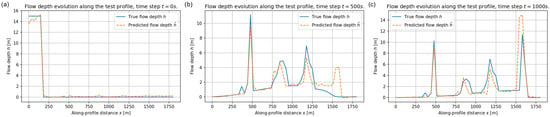

6.1.2. Flow–Depth Evolution Along Training Profiles

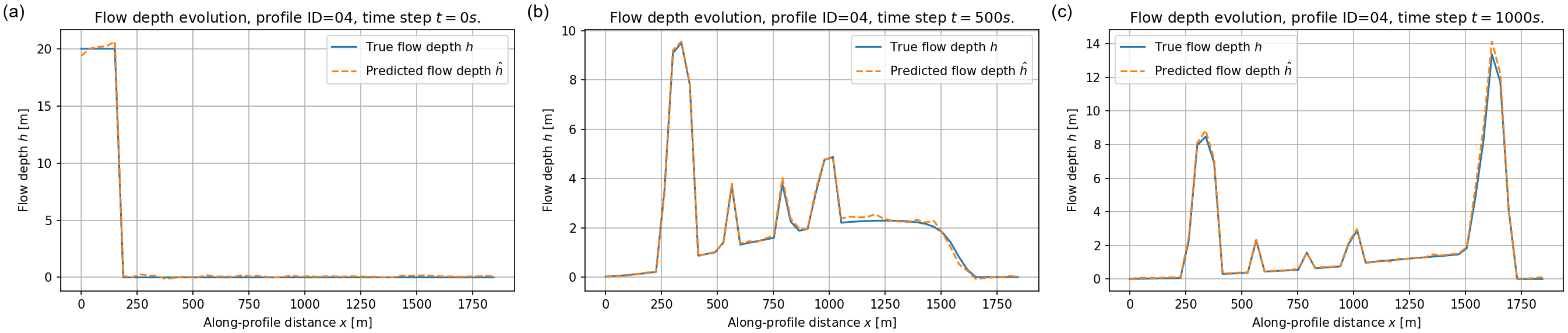

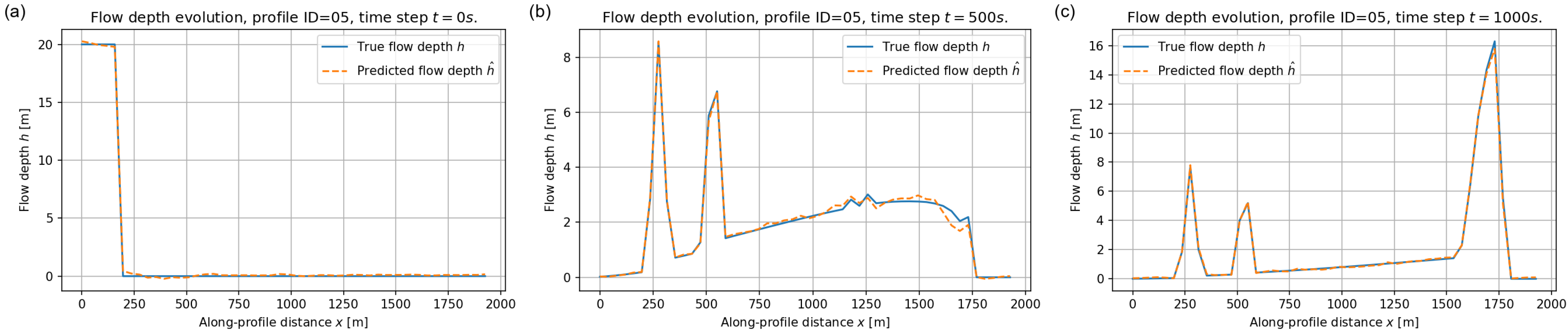

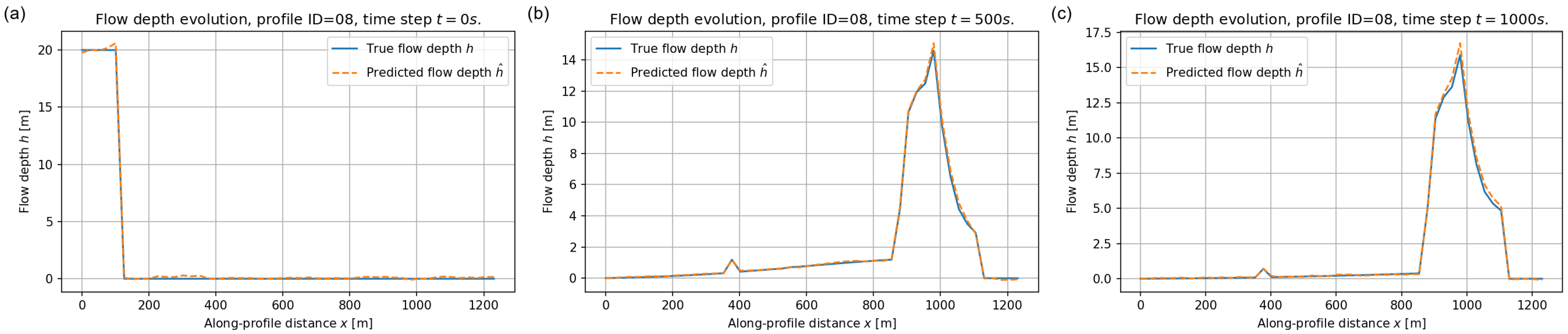

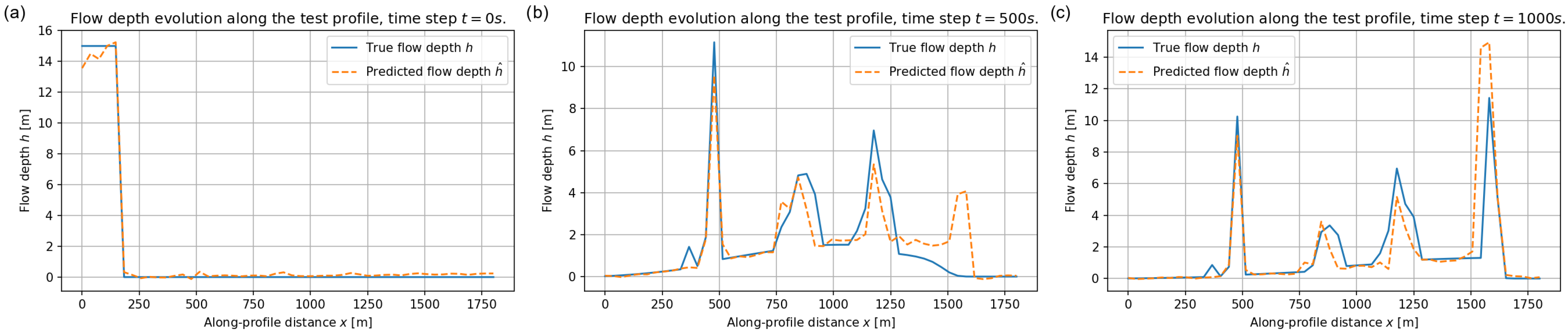

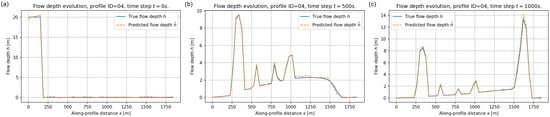

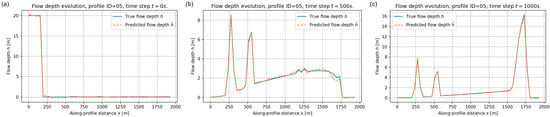

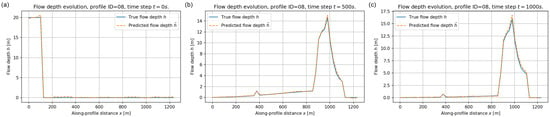

We now examine the ability of the FNO to reproduce the spatio–temporal evolution of the flow depth along representative longitudinal profiles from the validation set. For each example the model receives only the input fields described in Section 5.2 and predicts the full space–time field , which we analyse at , 500, and 1000 s.

Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12 show the results for three different profiles (ID = 04, 05 and 08). Across all profiles the FNO prediction almost coincides with the reference solution at the initial time, correctly reproducing the location and thickness of the released reservoir. At intermediate times the debris wave has propagated downstream and exhibits multiple local maxima associated with slope variations. The surrogate captures both the position and amplitude of these lobes with only small discrepancies near the sharpest peaks. By s the flow has mostly deposited and the depth profiles are dominated by residual accumulations, which are also accurately reproduced.

Figure 10.

Flow depth along validation profile ID = 04 at (a) s, (b) s, and (c) s. Blue solid lines: reference numerical solution ; orange dashed lines: FNO prediction .

Figure 11.

Flow depth along validation profile ID = 05 at (a) s, (b) s, and (c) s. Blue solid lines: reference depth ; orange dashed lines: predicted depth .

Figure 12.

Flow depth along validation profile ID = 08 at (a) s, (b) s, and (c) s. Blue solid lines: reference depth ; orange dashed lines: predicted depth .

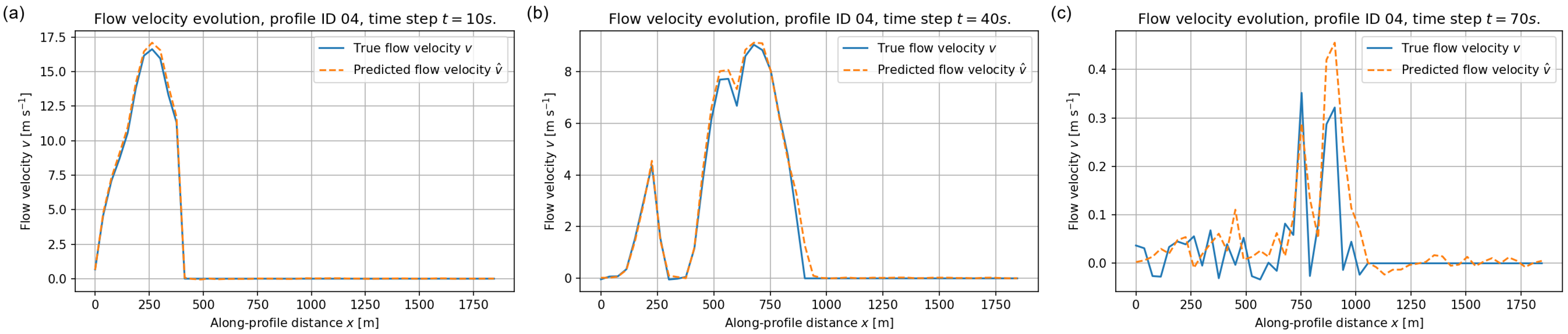

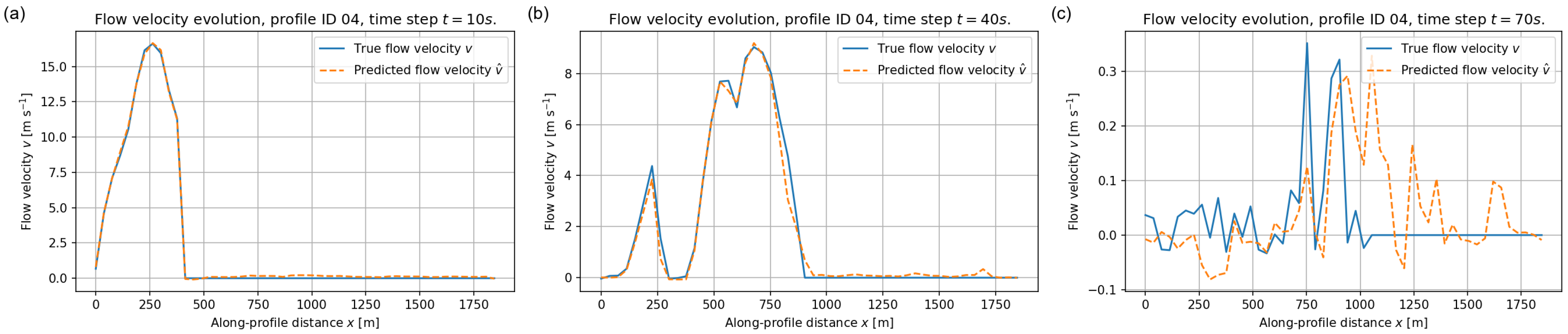

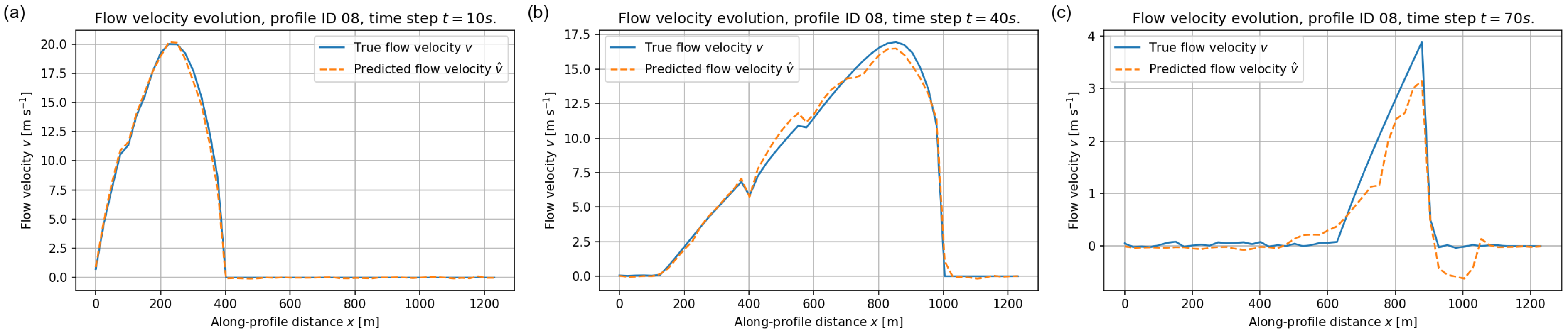

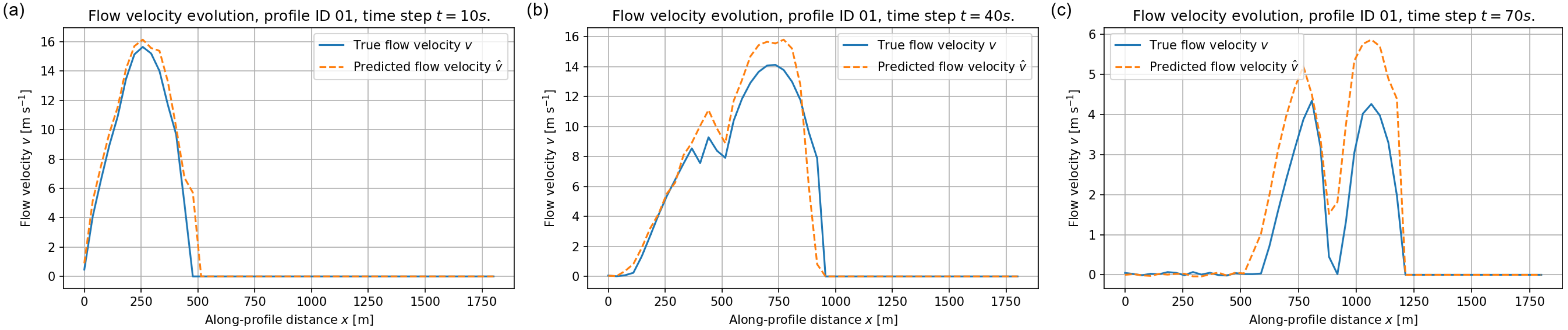

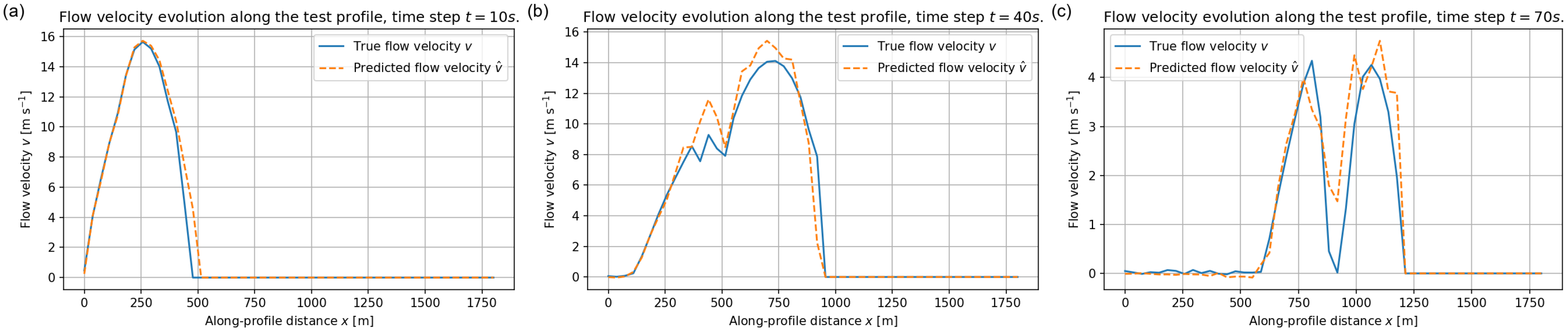

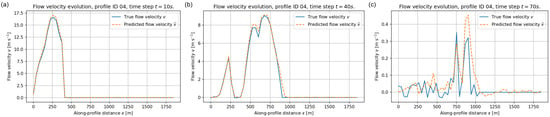

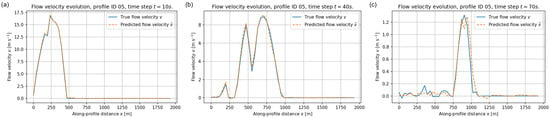

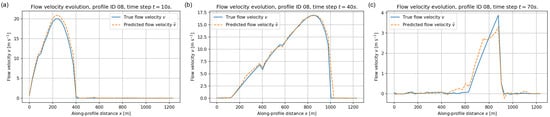

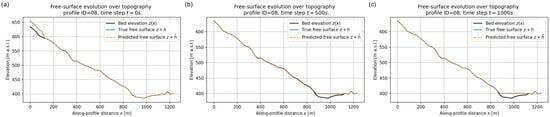

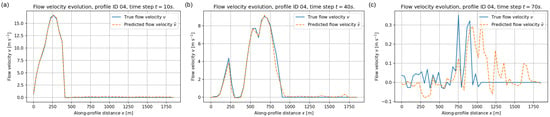

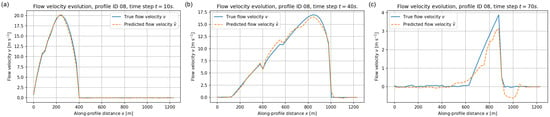

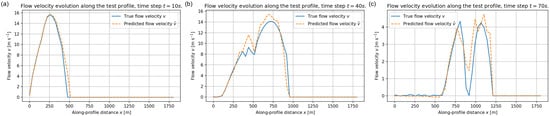

6.1.3. Flow–Velocity Evolution Along Training Profiles

The performance of the FNO on the velocity field is illustrated in Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15. These examples highlight both the strengths and the limitations of the surrogate in capturing rapid kinematic variations. For each profile we focus on three early stages of the simulation, at , 40 and 70 s, when the flow is still highly mobile and velocities attain their largest magnitudes. Later times, such as s, are not shown in the velocity plots because the flow has already come essentially to rest well before that time and is very close to zero everywhere, so that the corresponding curves would not provide additional information.

Figure 13.

Depth–averaged velocity along validation profile ID = 04 at (a) s, (b) s, and (c) s. Blue solid lines: reference velocity ; orange dashed lines: FNO prediction .

Figure 14.

Depth–averaged velocity along validation profile ID = 05 at (a) s, (b) s, and (c) s. Blue solid lines: reference solution ; orange dashed lines: FNO prediction .

Figure 15.

Depth–averaged velocity along validation profile ID = 08 at (a) s, (b) s, and (c) s. Blue solid lines: reference velocity ; orange dashed lines: FNO prediction .

Figure 13 shows the velocity evolution along profile ID = 04. During the acceleration phase at s and s the model correctly predicts the magnitude and location of the high–velocity front as well as the extent of the moving region. At s (Figure 13c), when multiple localised jets appear in the reference solution, the FNO reproduces the overall pattern but tends to slightly smooth secondary peaks.

Figure 14 reports the corresponding results for profile ID = 05. The agreement is again very good for the early high–velocity stages, with accurate amplitudes and positions of the surges. At intermediate times the FNO slightly underestimates the maximum velocities near the strongest peak, while still capturing its spatial extent.

A third example is provided in Figure 15 for profile ID = 08, which exhibits a slightly different topographic setting. The FNO maintains good accuracy in predicting the timing and amplitude of the initial high–velocity wave and its downstream propagation, again with a mild smoothing of the smallest late–time fluctuations.

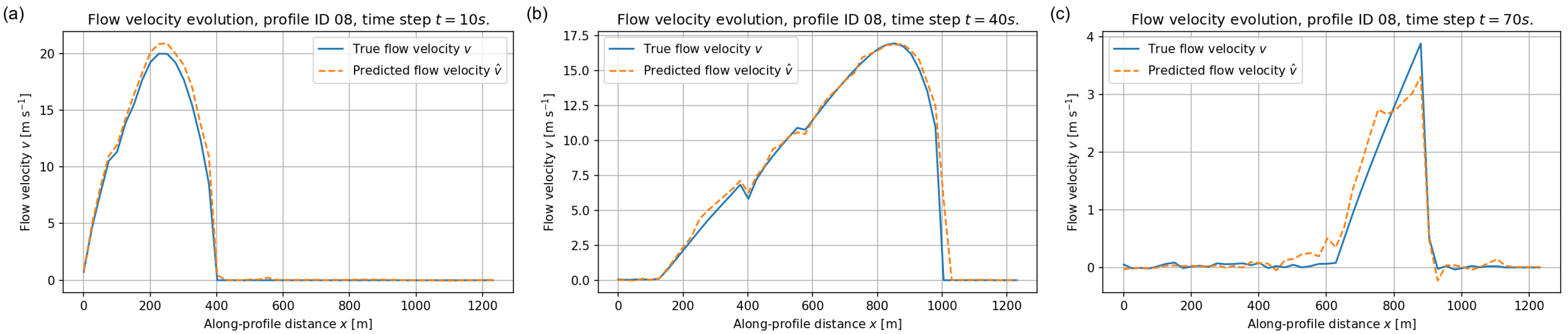

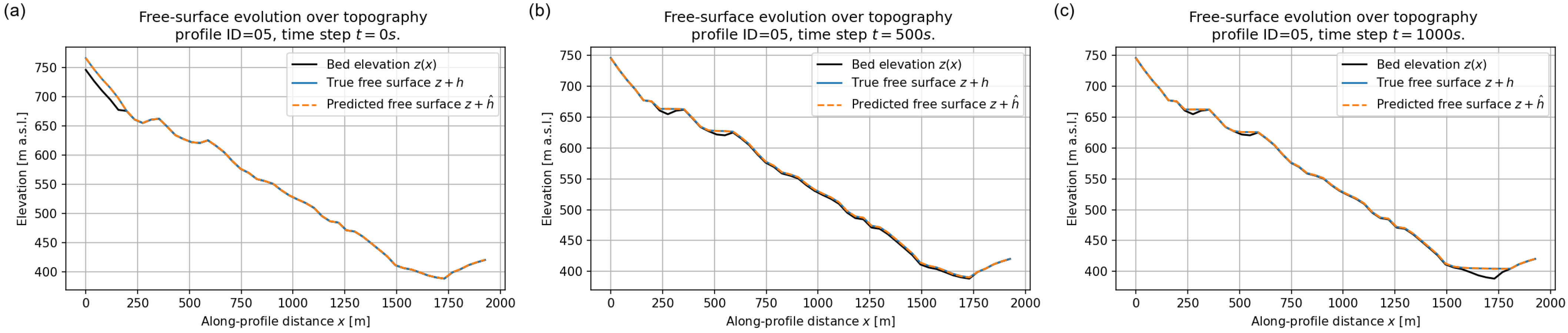

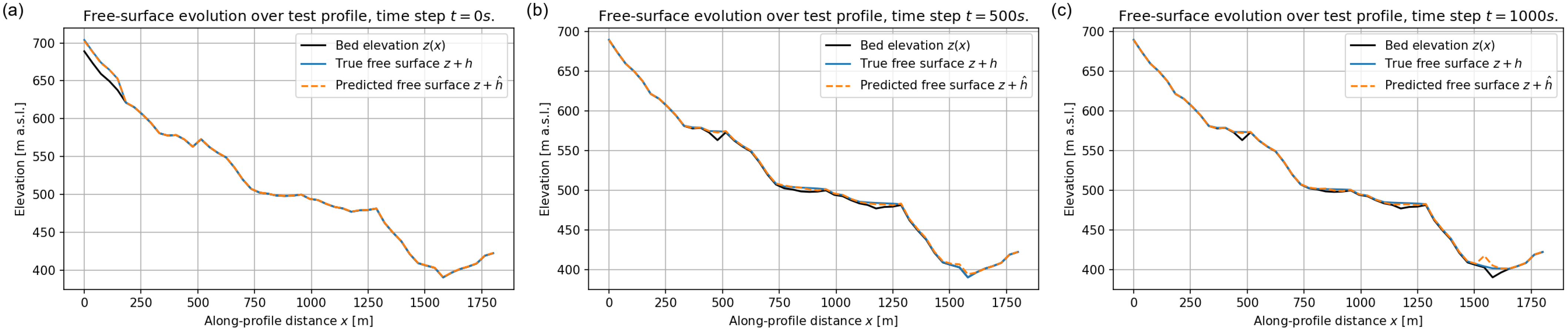

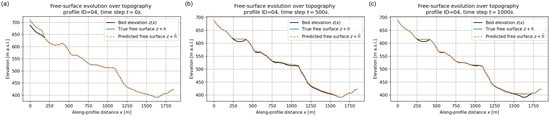

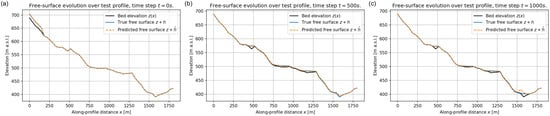

6.1.4. Free–Surface Evolution over Fixed Topography

An important diagnostic for hazard assessment is the position of the free surface relative to the bed , especially in relation to local slope breaks and depressions. Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18 compare the reference and predicted free surfaces for profiles ID = 04, 05 and 08, together with the underlying bed elevation.

Figure 16.

Free surface over topography for validation profile ID = 04 at (a) s, (b) s, and (c) s. Black line: bed elevation ; blue solid line: reference free surface ; orange dashed line: predicted free surface .

Figure 17.

Free surface over topography for validation profile ID = 05 at (a) s, (b) s, and (c) s. Black line: bed elevation ; blue solid line: reference free surface ; orange dashed line: predicted free surface .

Figure 18.

Free surface over topography for validation profile ID = 08 at (a) s, (b) s, and (c) s. Black line: bed elevation ; blue solid line: reference free surface ; orange dashed line: predicted free surface .

In Figure 16 the initial condition corresponds to an upstream reservoir resting on an otherwise dry bed. The FNO accurately reconstructs both the absolute elevation and the sharp lateral transition between wet and dry regions. At s and s (Figure 16b,c) the free surface becomes highly irregular, reflecting the interaction of the flow with the undulating bed; nonetheless, the predicted curve almost overlaps the reference one along the entire profile, including the small changes in curvature associated with topographic steps. A similar behaviour is observed for profiles ID = 05 and 08, where the surrogate correctly predicts the filling and emptying of local hollows and the overall decrease of the free–surface elevation as the flow migrates downstream and eventually deposits near the outlet. The excellent agreement between predicted and reference free–surface profiles confirms that the FNO has effectively learned the coupling between flow depth and bed elevation.

6.2. Reweighted Case: ,

6.2.1. Training Dynamics and Validation Errors

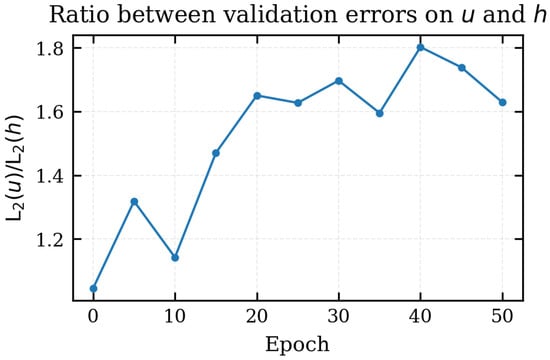

In the reweighted study we increase the velocity weight to (with ), motivated by the larger baseline errors in u. As the depth weight is unchanged, h is expected to remain unaffected, and the analysis therefore focuses on improvements in the velocity field.

Figure 19 shows stable training and validation losses, with rapid initial decrease and smooth convergence without overfitting. The behavior matches the baseline, indicating that increasing the weight on u preserves stability while encouraging improved velocity reconstruction.

Figure 19.

Total training and validation loss as a function of the epoch for the reweighted case (, ).

Figure 20 shows the relative validation errors for h and u versus epoch. Both decrease rapidly and then plateau; at convergence and –. As expected, depth accuracy matches the baseline, while velocity shows a moderate improvement.

Figure 20.

Relative validation errors for flow depth h and velocity u as a function of the epoch for the reweighted case (, ).

For the overall validation set in the reweighted case, the relative errors are

The systematic difference between the two components is further quantified in Figure 21. Compared to the baseline case (Figure 9), where R fluctuated between and , the sensitivity configuration yields a lower and more stable ratio, indicating a partial rebalancing of the learning process between h and u. Nevertheless, R remains consistently larger than one, confirming that the velocity field is still more challenging to approximate than the flow depth, due to its sharper gradients, local sign changes and higher spatial variability.

Figure 21.

Ratio between the relative validation errors on velocity and depth, , as a function of the epoch for the sensitivity case (, ).

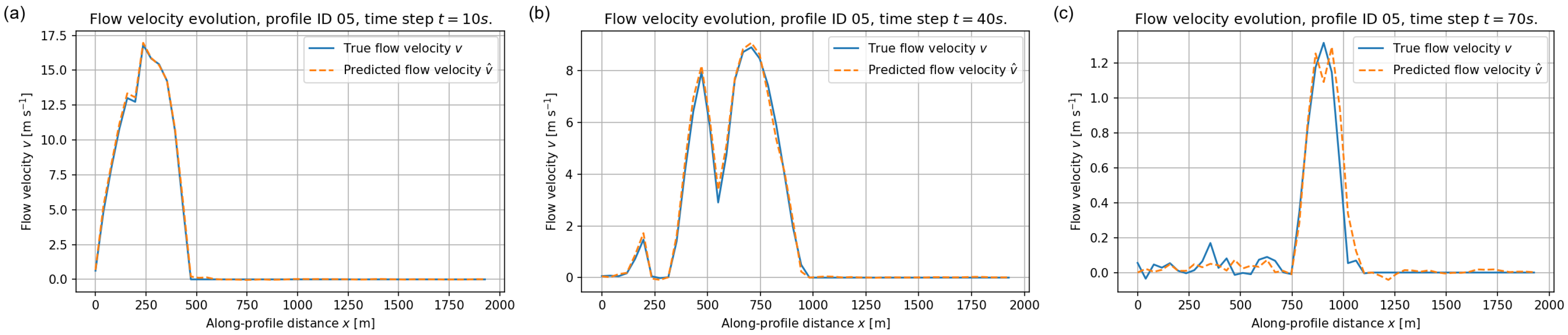

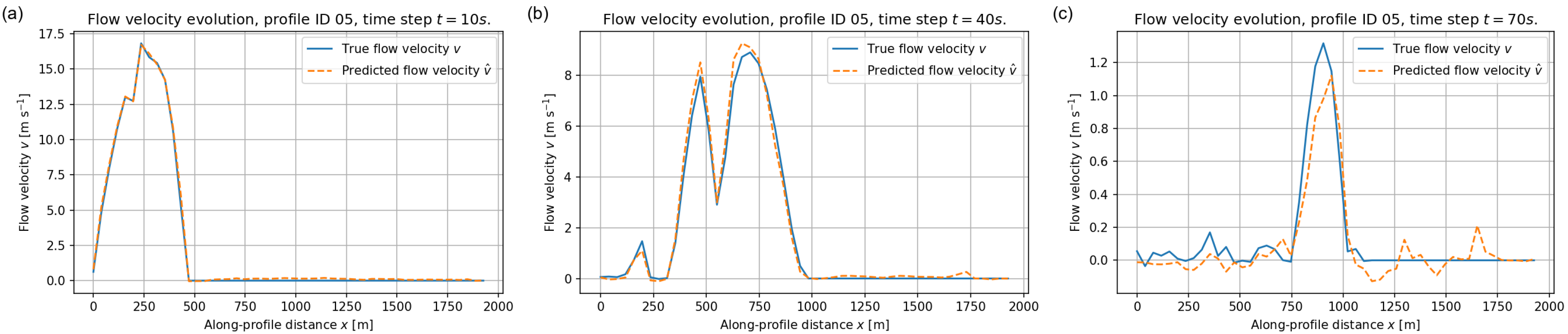

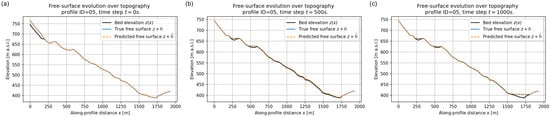

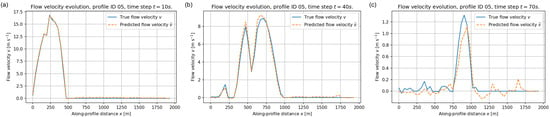

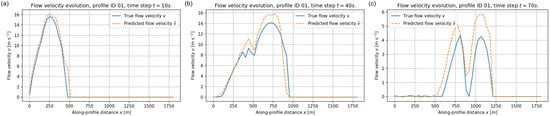

6.2.2. Flow–Velocity Evolution Along Training Profiles

We now analyse the impact of the modified weighting on the prediction of the velocity field along representative validation profiles. As in Section 6.1.3, we report snapshots at , 40 and 70 s, corresponding to the early stages of the simulation when the flow is highly mobile and velocity magnitudes are largest.

Figure 22 shows profile ID = 04. At s and s the predicted curves are almost indistinguishable from the reference solution, accurately reproducing both the magnitude and spatial extent of the high–velocity region. At s, when the reference solution displays multiple localised jets, the FNO prediction remains slightly smoother but captures the dominant peaks with improved amplitudes compared to the baseline case (Figure 13).

Figure 22.

Depth–averaged velocity along validation profile ID = 04 at (a) s, (b) s, and (c) s for the reweighted case (, ). Blue solid lines: reference velocity ; orange dashed lines: FNO prediction .

The corresponding results for profile ID = 05 are shown in Figure 23. Also in this case the agreement is excellent at early times. At s, the sensitivity training reduces the underestimation of the main surge peak that was observed in the baseline configuration (Figure 14), yielding a closer match in both amplitude and localisation of the moving front. At s the model captures the overall deceleration trend and the position of the residual high–velocity region, although minor discrepancies persist in the smallest fluctuations.

Figure 23.

Depth–averaged velocity along validation profile ID = 05 at (a) s, (b) s, and (c) s for the reweighted case (, ). Blue solid lines: reference velocity ; orange dashed lines: FNO prediction .

Figure 24 shows that for profile 08 the FNO reproduces the downstream acceleration and surge timing, with slight smoothing and underestimation of peak velocity. Compared to the baseline, peak amplitude and front localization are improved, demonstrating the benefit of increased velocity weighting in highly dynamic regimes.

Figure 24.

Depth–averaged velocity along validation profile ID = 08 at (a) s, (b) s, and (c) s for the reweighted case (, ). Blue solid lines: reference velocity ; orange dashed lines: FNO prediction .

6.3. Generalisation to an Unseen Test Profile

6.3.1. Baseline Case: ,

To evaluate the capability of the FNO to generalise beyond the set of longitudinal profiles employed during training and validation, we perform inference on an additional topographic transect that was never presented to the network. The spatial location of this transect within the study area is shown in Figure 25, where the test profile is superimposed on the orthophoto and the underlying DEM. This new transect crosses a geomorphologically complex portion of the basin, with varying slopes and local depressions, providing a suitable benchmark for assessing the robustness of the learned operator under previously unseen geometric conditions.

Figure 25.

Location of the unseen test profile (blue line) within the study area, plotted over the orthophoto and DEM.

Figure 26 shows the evolution of the flow depth along the unseen test profile at , 500, and 1000 s. The surrogate faithfully reproduces the initial reservoir and the subsequent formation of multiple surges as the flow travels downslope. At s the reference solution exhibits a complex pattern with several peaks of different heights; despite having never encountered this exact topography, the FNO captures the number, approximate position, and amplitude of these surges, with only modest underestimation of the tallest peak and smoothing of the smallest downstream lobes. By s, when deposition dominates, the predicted depths remain in very good agreement with the numerical solution, including the location and thickness of the final accumulation. For this unseen profile, the relative errors for the flow depth are

Figure 26.

Flow depth along the unseen test profile at (a) s, (b) s, and (c) s. Blue lines: reference depth ; orange dashed lines: FNO prediction .

Figure 27 reports the velocity evolution at , 40, and 70 s. As in the training examples, we purposely exclude a snapshot at s, because the flow is essentially at rest well before that time and the velocity field contains no additional information of dynamical relevance. The FNO accurately reconstructs the high–velocity front, its downstream propagation, and the emergence of secondary peaks, although with a slight smoothing of the sharpest gradients and a modest underestimation of the maximum speeds. Despite these minor differences, the predicted spatial patterns remain highly coherent with the numerical solution, confirming thatthe surrogate maintains its predictive ability also for previously unseen topographies.

Figure 27.

Depth–averaged velocity along the unseen test profile at (a) s, (b) s, and (c) s. Blue lines: reference velocity ; orange dashed lines: prediction .

Finally, the corresponding free–surface elevation is shown in Figure 28. Also in this case, the predicted free surface closely follows the reference at all times, demonstrating that the learned operator remains accurate when extrapolated to a new geometric configuration. Figure 28b,c highlight the ability of the FNO to reproduce the filling and emptying of local depressions and the gradual downstream migration of the wave crest. The excellent overlap between predicted and reference curves indicates that the coupling between flow depth and bed geometry is robustly captured.

Figure 28.

Free surface over the unseen test profile at (a) s, (b) s, and (c) s. Black lines: bed elevation ; blue lines: reference free surface ; orange dashed lines: predicted free surface .

6.3.2. Reweighted Case: ,

We now assess the generalisation capability of the FNO on the same unseen test profile for the sensitivity configuration, in which a larger weight is assigned to the velocity component in the loss function. Since the depth component is not affected by the modified weighting, we focus here exclusively on the behaviour of the predicted velocity field .

For the unseen test profile, the relative errors obtained in the sensitivity case are

Compared to the baseline configuration (Section 6.3.1), the error on the velocity is reduced by more than a factor of two (from to ), while the depth error remains of the same order of magnitude, consistently with the unchanged weight . This quantitatively confirms that the modified loss function substantially improves the generalisation performance of the surrogate with respect to the velocity field.

Figure 29 shows velocity along the unseen profile at , 40, and 70 s. At s, the FNO closely matches both magnitude and extent of the high-velocity front; compared to the baseline, reduced smoothing yields a sharper, more physically consistent leading edge. At s, the FNO with more accurately reproduces the plateau, peaks, and downstream decay, reducing peak underestimation and sharpening key kinematic features on the unseen topography. At s, the sensitivity model correctly captures the positions and relative magnitudes of the two velocity peaks; despite minor shape differences in the trough, peak amplitudes and localization are more accurate than in the baseline, which showed stronger smoothing and underestimation.

Figure 29.

Depth–averaged velocity along the unseen test profile at (a) s, (b) s, and (c) s for the reweighted case (, ). Blue lines: reference velocity ; orange dashed lines: FNO prediction .

6.4. Inference Performance Comparison

During inference, the FNO model achieved a total execution time of 0.285 s for the complete procedure, including the forward pass and denormalization. In comparison, the traditional numerical solver required 10.463 s to perform the same task. This demonstrates a performance improvement of more than 36× in favor of the neural operator for inference.

While the solver provides the baseline numerical reference, the FNO enables significantly faster evaluations once trained, making it particularly suitable for scenarios where rapid predictions are essential. All results were obtained using a CPU-based system, but the entire workflow could equally be executed on a machine equipped with a dedicated GPU. In such a configuration, both dataset generation and training times would likely decrease substantially due to higher computational throughput.

However, the proportional advantage observed during inference, where the FNO is dramatically faster than the traditional solver, would remain essentially the same, as this speed-up derives from the intrinsic difference between learned operators and numerical solvers rather than from the underlying hardware.

7. Discussion

The results presented in Section 6 demonstrate that a Fourier Neural Operator trained exclusively on synthetic one-dimensional shallow-water simulations can reproduce debris-flow dynamics with very good accuracy over a broad range of rheological parameters and topographic configurations.

7.1. Surrogate Performance and Physical Consistency

The results in Section 6 show that a Fourier Neural Operator trained solely on synthetic one-dimensional shallow-water simulations can accurately reproduce debris-flow dynamics across a wide range of rheological parameters and topographies, within the domain covered by the training data. Both validation metrics and qualitative comparisons support this conclusion. In the baseline case (), validation errors stabilise at and , with the error ratio ranging from 1.7 to 2.3, indicating systematically higher velocity errors. Visual inspections confirm that the model reproduces depth propagation and deposition accurately, while capturing the main velocity structures with slight smoothing of secondary features. Moreover, the excellent agreement of free-surface diagnostics over complex bed geometries demonstrates that the operator effectively learns the coupling between flow depth and topography.

The sensitivity study with increased velocity weighting () shows that part of the error stems from an imbalance between state variables in the loss. As expected, depth accuracy remains unchanged, while velocity error improves from to , and the ratio R decreases and stabilises around –. Profile comparisons confirm reduced underestimation of peak velocities and better localisation of high-velocity fronts, especially at early times. This supports the interpretation that velocity, being more irregular and gradient-dominated than depth, is harder to approximate with a spectral operator and benefits from explicit loss reweighting.

The generalisation test on an unseen longitudinal profile highlights both the strengths and limits of the surrogate. In the baseline case, the model produces coherent predictions on a complex, unseen geometry, with good agreement in depth and free-surface evolution, although errors increase to and , with the largest degradation in velocity. With velocity reweighting, depth accuracy remains similar (), while the velocity error drops markedly to . The corresponding snapshots show sharper fronts and more accurate peak amplitudes, indicating that the modified loss not only rebalances training errors but also substantially improves extrapolation of the kinematic field on unseen geometries.

7.2. Methodological Contribution: Objective-Function Design and Velocity Reweighting

Beyond validating solver-consistent surrogate modelling, this work highlights the importance of loss design for hazard-relevant variables. In the baseline setting (, ), the FNO achieves low errors for depth but consistently higher errors for velocity, with typically between 1.7 and 2.3. This imbalance reflects the greater complexity of , which exhibits sharper gradients, intermittent peaks, and higher-frequency features that are intrinsically harder to approximate.

To address this limitation and improve suitability for hazard assessment, where velocity is critical, we increase the velocity weight to while keeping . This reweighting remains stable but directs learning toward the more challenging variable. As a result, the validation error for u decreases from to , while depth accuracy remains unchanged (). The benefit is even clearer in generalisation: on the unseen profile, the velocity error drops from to , with depth errors remaining of similar magnitude, consistent with the unchanged weighting on h.

These results indicate that the objective-function design constitutes a non-trivial methodological degree of freedom in operator-learning for debris flows: rebalancing the loss terms can materially improve generalisation for the hazard-relevant variable without degrading the reconstruction of flow depth.

7.3. Inference Efficiency and Performance Relative to the Numerical Solver

From a practical perspective, the primary advantage of the proposed surrogate lies in its computational efficiency, as demonstrated by the direct comparison between inference times of the trained FNO and the traditional finite-volume solver. During inference, the neural operator required only to generate the full space–time fields and perform the subsequent denormalisation, whereas the numerical solver needed to complete the corresponding simulation. This corresponds to a speed-up exceeding a factor of 36, fully consistent with the qualitative considerations previously discussed and providing empirical confirmation of the transformative potential of operator-learning approaches for rapid scenario evaluation.

It is important to emphasise that these timings were obtained on a CPU-based system. Although migrating the workflow to GPU hardware would accelerate both dataset generation and network training, the relative inference advantage of the FNO over the classical solver would remain essentially unchanged. This disproportion stems not from hardware acceleration but from the intrinsic difference between learned operators, which require only a single forward pass with fixed computational cost, and numerical solvers, whose cost grows with grid resolution, stiffness of the equations, and simulation time. Consequently, even in GPU-accelerated environments, the FNO surrogate would continue to provide dramatic speed-ups, reinforcing its suitability for large ensemble simulations, real-time scenario screening, and operational early-warning systems.

7.4. Implications for Large-Scale and Probabilistic Debris-Flow Hazard Analysis

A more quantitative evaluation of the computational efficiency of the FNO highlights its potential impact on debris-flow hazard assessment. Once trained, the FNO can generate full space–time fields at essentially negligible marginal cost, achieving speed-ups of several orders of magnitude relative to the finite-volume solver. This efficiency becomes particularly valuable when large ensembles of simulations are required, for example, to propagate epistemic uncertainty in rheological properties, released volume, or initial saturation conditions. Under these circumstances, computational demands that would be prohibitive for classical solvers become tractable with a trained FNO, enabling Monte Carlo analyses, global sensitivity studies, and near real-time probabilistic hazard mapping.

7.5. Site-Specific Surrogates and Integration with Probabilistic Modelling

Another implication is the feasibility of site-specific surrogates. The synthetic dataset used in this work is tailored to the Morino–Rendinara debris-flow system, with parameter ranges informed by previous back-analyses of the March 2021 event [4]. By focusing on a single catchment, we restrict the parameter and topographic space that the operator must represent, which in turn facilitates high accuracy with a relatively compact network.

This “basin-specific” philosophy aligns with operational practice in engineering hazard assessment, where analyses are typically performed at the scale of an individual valley or infrastructure corridor. In such settings, a dedicated FNO trained on synthetic simulations for that catchment could serve as a lightweight proxy for the original solver, providing instantaneous predictions for early warning systems, scenario screening, or interactive decision-support tools. Conversely, extrapolation to geometries, slopes, or rheological regimes that fall outside the training distribution is not expected to be reliable and would likely result in performance degradation, in accordance with well-established principles of deep learning and operator learning.

The present results also complement recent efforts to use synthetic data for probabilistic debris-flow modelling [28]. In that study, synthetic simulations informed a Bayesian neural network for predicting accumulation volumes, whereas here we use synthetic simulations to train an operator that predicts full space–time fields of depth and velocity. Combining these approaches, for example, using an FNO to generate fast ensembles of fields that are subsequently post-processed by probabilistic models targeting specific impact metrics, could offer a flexible and efficient framework for quantitative risk analysis.

7.6. Limitations and Perspectives for Future Work

Although the proposed framework already demonstrates strong predictive skill and excellent computational efficiency, three main directions for further development remain: extensions of the numerical model and its underlying physical parametrisation, expansion and refinement of the dataset towards site-specific and territorial applications and a broader exploration and benchmarking of alternative neural and physics-informed surrogate architectures.

In line with the stated objective of this study, these results should be interpreted primarily as an assessment of the surrogate modelling strategy rather than as the proposal of a new neural operator architecture. The numerical solver, which has been fully validated, is employed here as a tool to generate physically consistent training data, while the central contribution lies in demonstrating how operator learning can be utilised, conditioned, and evaluated for debris-flow modelling in a hazard-oriented setting. In particular, the FNO is trained to learn the full space–time solution operator mapping continuous functional inputs (topography, rheological parameters, and initial conditions) directly to the state variables and , thereby enabling efficient scenario exploration and rapid surrogate inference.

7.6.1. Extensions of the Physical Model and Numerical Solver

The present study relies on a one-dimensional depth-averaged shallow-water formulation with Voellmy-type basal friction. This setting is well suited for synthetic ensemble generation in confined channels, but it still represents an idealised description of debris-flow dynamics. Crucially, the surrogate inherits all assumptions of the underlying solver, which operates on a longitudinal profile derived from orthophotos and DEMs; any errors in the input data therefore propagate through both the numerical model and the learned operator, which implicitly assumes their correctness. Moreover, the approach neglects lateral spreading, channel widening, and other inherently 2D/3D processes, relying instead on simplified friction laws and vertically averaged dynamics. Consequently, the framework is not directly transferable to more complex geometries or fully multidimensional flows, and the results should be interpreted not as physically validated event reconstructions but as solver-consistent approximations bounded by the assumptions of the reference model. A more comprehensive numerical framework is envisioned for development, integrating not only additional physical processes, such as internal viscosity, morphodynamic evolution through the Exner equation, spatially varying sediment density, and grain-size segregation and transport, but also a progressive extension of the governing equations and solver architecture from one-dimensional domains to fully two- and three-dimensional geometries. Furthermore, adaptive mesh refinement tailored to local topography and curvature, departing from a uniformly spaced discretization, will be introduced. Moving towards 2D and 3D formulations will allow the model to capture lateral spreading, channel bifurcations, and more complex topographic interactions that cannot be represented in a purely longitudinal framework. The consolidation of these modules, together with an extended suite of verification tests (e.g., analytical benchmarks, uniform-flow equilibrium checks, viscous diffusion tests, and density–Exner consistency evaluations), will enable the creation of richer synthetic datasets that resolve not only flow depth and velocity, but also coupled variations in bed elevation, material composition, and bulk density. These developments will naturally enhance the realism of the training data and substantially expand the operational range of the operator-learning model.

7.6.2. Dataset Expansion, Calibration, and Territorial Scalability

It must be acknowledged that the FNO is trained and validated exclusively on synthetic simulations from the same numerical solver, and thus learns the solver’s input–output mapping rather than the physical system directly. This reflects the scarcity of dense, space–time–resolved field observations required by operator-learning methods. Although the reference solver is physics-based and previously validated, and emulating it yields a physically consistent representation of debris-flow dynamics and their parametric dependence, the current surrogate is trained on a finite number of synthetic simulations based on representative profiles of the Morino–Rendinara system. While this ensures physical consistency, the next step towards robust operational performance is to broaden the dataset both geomorphologically and parametrically. This includes incorporating additional field-derived profiles, refining local geomorphological information, and sampling more densely across initial conditions, rheological parameters, and material properties. A more diversified dataset will improve calibration against real landscapes and strengthen generalisation within the basin. Moreover, this strategy provides a scalable pathway for constructing families of site-specific models: by replicating the workflow in other catchments and expanding the corresponding synthetic datasets, it becomes possible to develop territorial Fourier Neural Operators tailored to each zone of interest. Such fast, localised surrogates could then be integrated into early-warning systems, enabling rapid scenario exploration and near real-time hazard assessment at the basin scale.

7.6.3. Neural-Architecture Choices and Benchmarking Perspectives

A further limitation is the lack of a systematic quantitative comparison with alternative surrogate or physics-informed approaches. This study focuses on a single architecture, the Fourier Neural Operator, for its operator-learning capability, mesh independence, and effectiveness on parametric PDEs, leaving a broader benchmark to future work. In this context, Graph Neural Networks [40], Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) [41], and Deep Operator Networks (DeepONets) [24] remain promising alternatives, potentially offering complementary trade-offs in physical constraint enforcement, interpretability, and computational efficiency.

In addition, the Fourier-mode truncation used in the present FNO constitutes a further limitation, as it was not selected through a systematic hyperparameter search. Although this choice represents a physically motivated compromise between capturing large-scale dynamics, numerical stability, and computational efficiency [38,39], it may contribute to smoothing by under-representing high-frequency content, particularly in the velocity field. A systematic study treating the number of retained modes as a design parameter, and assessing the trade-off between resolving sharp features and maintaining stability and efficiency, is therefore left for future work.

8. Conclusions

This work investigates the feasibility of using a Fourier Neural Operator (FNO) as a physics-consistent surrogate for one-dimensional debris-flow modelling, applied to the Rendinara–Morino system in central Italy. To address limited observations and the computational cost of high-fidelity solvers, we combine a validated finite-volume shallow-water model with operator learning to build a site-specific digital twin of debris-flow dynamics.

A large synthetic dataset was created by sampling key physical and rheological parameters (e.g., bulk density, initial thickness, Voellmy friction) across multiple representative longitudinal profiles. The resulting depth and velocity fields were used to train a two-dimensional FNO in the domain, conditioned on topography, initial conditions, and material properties, to approximate the full solution operator and enable generalisation across parameters and geometries within the sampled domain.

The FNO reproduces the numerical solver with mean relative errors of about 6– for depth and 10– for velocity, accurately capturing spatio–temporal dynamics, deposition, and coupling with bed topography. It also generalises to an unseen longitudinal profile, retaining good predictive skill under moderate geometric extrapolation when the geometry remains representative of the training data.

A key methodological contribution lies in the loss design: reweighting the objective to emphasise velocity significantly improves kinematic accuracy without degrading depth predictions. With this reweighting, validation velocity errors fall below , and on the unseen profile they drop by more than a factor of two, demonstrating that targeted loss design can substantially enhance hazard-relevant surrogate performance.

Computationally, the trained FNO achieves over a speed-up relative to the finite-volume solver while retaining solver-level accuracy. This enables otherwise impractical tasks, such as large ensembles, uncertainty propagation, sensitivity analysis, and near–real-time scenario screening, making the surrogate a lightweight, site-adapted digital twin of the numerical model.

The framework also has clear limitations: trained solely on synthetic data, the surrogate learns the solver’s mapping rather than the physical system, and its validity is bounded by the assumptions of the one-dimensional shallow-water model and the representativeness of the sampled parameter and topographic space. Extrapolation beyond this domain is therefore unreliable; nonetheless, within its intended scope, the approach provides a robust and efficient alternative to repeated numerical simulations.

Overall, this study demonstrates that combining physics-based synthetic data with operator-learning architectures provides a viable pathway for constructing accurate, computationally efficient, and site-specific surrogates for debris-flow modeling in data-scarce environments. Beyond the specific case of the Rendinara–Morino system, the proposed methodology is readily transferable to other catchments through the generation of basin-specific synthetic datasets. Future work will focus on extending the framework to two- and three-dimensional solvers, enriching the physical parametrization, integrating field observations for calibration, and benchmarking against alternative architectures such as Graph Neural Networks [40], Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) [41], and Deep Operator Networks (DeepONets) [24]. These developments will further enhance the role of operator learning as a practical tool for debris-flow hazard analysis, early-warning systems, and decision support in mountainous environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and A.P.; methodology, M.S.; software, M.S. and A.P.; validation, A.P., N.S. and M.M.; formal analysis, M.S.; investigation, M.S., A.P.; resources, A.P., N.S. and M.M.; data curation, M.S. and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S. and A.P.; visualization, M.S. and A.P.; supervision, A.P. and N.S.; project administration, N.S.; funding acquisition, N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR) under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP–Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.3–D.D. 1243, 2/8/2022), within the RETURN Extended Partnership–Multi-Risk sciEnce for resilienT commUnities undeR a changiNg climate (Project Code: PE_00000005, CUP: B53C22004020002). The research was conducted as part of the project “LANdslide DAMs (LanDam): characterization, prediction and emergency management of landslide dams”.

Data Availability Statement

The synthetic datasets generated and analyzed during the current study, as well as the training and inference scripts for the Fourier Neural Operator, are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Iverson, R.M. The Physics of Debris Flows. Rev. Geophys. 1997, 35, 245–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arattano, M.; Franzi, L. Influence of Rheology on Debris-Flow Dynamics. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasculli, A.; Cinosi, J.; Turconi, P.; Sciarra, N. Learning Case Study of a Shallow-Water Model to Assess an Early-Warning System for Fast Alpine Muddy-Debris-Flow. Water 2021, 13, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasculli, A.; Zito, C.; Sciarra, N.; Mangifesta, M. Back Analysis of a Real Debris Flow, the Morino–Rendinara Test Case (Italy), Using RAMMS Software. Land 2024, 13, 2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, T.J. Computational Fluid Dynamics, 4th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; p. 1012. [Google Scholar]

- Pasculli, A. Viscosity variability impact on 2D laminar and turbulent Poiseuille velocity profiles; characteristic-based split (CBS) stabilization. In Proceedings of the 2018 5th International Conference on Mathematics and Computers in Sciences and Industry (MCSI), Corfu, Greece, 25–27 August 2018; pp. 770–771. [Google Scholar]

- Audusse, E.; Bouchut, F.; Bristeau, M.-O.; Klein, R.; Perthame, B. A fast and stable well-balanced scheme with hydrostatic reconstruction for shallow water flows. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2004, 25, 2050–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]