Something Old, Something New: Revisiting Terranes of the Western Paleozoic and Triassic Belt, Klamath Mountains, Northern California

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geologic Background

2.1. North Fork Terrane

2.2. Eastern Hayfork Terrane

2.3. Western Hayfork Terrane

2.4. Klamath and Sierra Nevada Offset

3. Geology of the Study Area

3.1. North Fork Terrane

3.2. Eastern Hayfork Terrane

3.3. Western Hayfork Terrane

3.4. Igneous and Metaigneous Units

4. Methods

5. Results

5.1. Salmon River Area

5.2. Wildwood Area

6. Discussion

6.1. Petrography and Geochronology

6.2. Comparing the North Fork and Eastern Hayfork Terranes

6.3. Magmatism and Metamorphism

7. Conclusions

- In the Wildwood area of the southern Klamath Mountains, the petrography of the EHT matrix and NFT siliciclastic strata is consistent with previous studies and with the poor zircon yields from many of these rocks.

- Detrital zircon ages in the southern EHT matrix are consistent with exotic olistostromal material.

- Detrital zircon U-Pb ages from the WHT yield an MDA of ~171 Ma and minor pre-Mesozoic ages, consistent with detrital hornblende K-Ar and 40Ar/39Ar ages, crosscutting intrusions at 170 Ma, and terrigenous input from older accreted terranes.

- A 143 Ma dike crosscutting the southern EHT is consistent with offset of the Klamath Mountains and Sierra Nevada after 140 Ma.

- 5.

- Within the central EHT, a sequence of layered metavolcanic/metavolcaniclastic rocks is 158 Ma and may represent a volcanic component of the Wooley Creek intrusive suite, which may have covered much of the Western Paleozoic and Triassic belt. Significant deformation occurred since deposition to rotate it into its current subvertical orientation.

- 6.

- A young ~145 Ma population of detrital zircon ages in the central WHT is younger than crosscutting intrusions and suggests Pb loss during an episode of metamorphism, possibly related to the intrusion of the Western Klamath suite.

- 7.

- The southern EHT matrix includes mafic volcanic rocks and olistostromal sandstone, which are locally mixed. One matrix sample has detrital zircon ages similar to olistostromal blocks and matrix in the EHT, but it is significantly more metamorphosed, and the youngest zircon age population is 69 Ma, consistent with minor Late Cretaceous detrital zircons in the Klamath Mountains from previous studies, which is difficult to explain by contamination. The young grains may have experienced lead loss during metamorphism, but this does not match any known episode of magmatism or metamorphism. We tentatively suggest that the young grains record previously unrecognized local metamorphism and/or magmatism ≤69 Ma, potentially related to local dikes and/or hydrothermal fluids.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A | Archean |

| act/trm | Actinolite/tremolite |

| amph | Amphibole |

| BSE | Backscattered electron |

| CDP | Cumulative distribution plot |

| chl | Chlorite |

| CMZ | Condrey Mountain shear zone |

| EHT | Eastern Hayfork terrane |

| fel | Feldspar |

| grt | Garnet |

| IAT | Island arc tholeiite |

| KDE | Kernel density estimation |

| LA-MC-ICPMS | Laser ablation multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry |

| Lk | Lake |

| MDA | Maximum depositional age |

| MDS | Multi-dimensional scaling |

| MLA | Maximum likelihood age |

| MORB | Mid-ocean ridge basalt |

| MSWD | Mean square of weighted deviates |

| Mtn | Mountain |

| Mz | Mesozoic |

| N | Number of samples in a compilation |

| n | Number of analyses |

| NFT | North Fork terrane |

| OF | Orleans fault |

| OIB | Ocean island basalt |

| PDP | Probability distribution plot |

| Pk | Peak |

| Pt | Point |

| Ptz | Proterozoic |

| Pz | Paleozoic |

| qtz | quartz |

| SCRT/SRT | Soap Creek Ridge thrust/Salmon River thrust |

| SCT | Salt Creek thrust |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| ST | Siskiyou thrust |

| TiO | Titanium oxide |

| TST | Twin Sisters thrust |

| TT | Trinity thrust |

| ttg | tonalite–trondhjemite–granodiorite |

| WHT | Western Hayfork terrane |

| WPT | Wilson Point thrust |

| YGC3+ (2σ) | Youngest grain cluster of three or more grains overlapping in 2σ error |

| YSG | Youngest single grain |

| YSP | Youngest statistical population |

References

- Irwin, W.P. Terranes of the Western Paleozoic and Triassic Belt in the Southern Klamath Mountains, California. In Geological Survey Research 1972; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1972; pp. C103–C111. [Google Scholar]

- Saleeby, J.B. Accretionary Tectonics of the North American Cordillera. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1983, 11, 45–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoke, A.W.; Barnes, C.G. The Development of Tectonic Concepts for the Klamath Mountains Province, California and Oregon. In Geological Studies in the Klamath Mountains Province, California and Oregon: A Volume in Honor of William P. Irwin; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-8137-2410-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, J.E. Permo-Triassic Accretionary Subduction Complex, Southwestern Klamath Mountains, Northern California. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1982, 87, 3805–3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, W.P. Correlation of the Klamath Mountains and Sierra Nevada; Open-File Report; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2003; Volume 2002–490. [Google Scholar]

- Surpless, K.D.; Alford, R.W.; Barnes, C.; Yoshinobu, A.; Weis, N.E. Late Jurassic Paleogeography of the U.S. Cordillera from Detrital Zircon Age and Hafnium Analysis of the Galice Formation, Klamath Mountains, Oregon and California, USA. GSA Bull. 2024, 136, 1488–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, H.H.; Ernst, W.G. North Fork Terrane, Klamath Mountains, California: Geologic, Geochemical, and Geochronologic Evidence for an Early Mesozoic Forearc. In Special Paper 438: Ophiolites, Arcs, and Batholiths: A Tribute to Cliff Hopson; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2008; Volume 438, pp. 289–309. ISBN 978-0-8137-2438-6. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, H.H.; Ernst, W.G.; Wooden, J.L. Regional Detrital Zircon Provenance of Exotic Metasandstone Blocks, Eastern Hayfork Terrane, Western Paleozoic and Triassic Belt, Klamath Mountains, California. J. Geol. 2010, 118, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, W.G.; Wu, C.; Lai, M.; Zhang, X. U-Pb Ages and Sedimentary Provenance of Detrital Zircons from Eastern Hayfork Meta-Argillites, Sawyers Bar Area, Northwestern California. J. Geol. 2017, 125, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.E.; Fahan, M.R. An Expanded View of Jurassic Orogenesis in the Western United States Cordillera: Middle Jurassic (Pre-Nevadan) Regional Metamorphism and Thrust Faulting within an Active Arc Environment, Klamath Mountains, California. GSA Bull. 1988, 100, 859–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, M.M.; Barnes, C.G.; Tomlinson, S.L. The Enigmatic Applegate Group of Southwestern Oregon: Age, Correlation, and Tectonic Affinity. Or. Geol. 1996, 58, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Surpless, K.D.; Barnes, C.; Yoshinobu, A. Record of the Late Jurassic Cordilleran Margin from Detrital Zircon Analysis of the Galice and Mariposa Formations, California and Oregon. In Jurassic–Paleogene Tectonic Evolution of the North American Cordillera; Gordon, S.M., Miller, R.B., Rusmore, M.E., Tikoff, B., Eds.; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2025; pp. 1–40. ISBN 978-0-8137-2565-9. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, A.E. Space/Time Evolution of Magmatism in the Klamath Mountains Province, CA/OR: Implications for Cordilleran Arc Magma Periodicity. Master’s Thesis, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, B.R.; Ernst, W.G.; McWilliams, M.O. Genesis and Evolution of a Permian-Jurassic Magmatic Arc/Accretionary Wedge, and Reevaluation of Terranes in the Central Klamath Mountains. Tectonics 1993, 12, 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, W.G. Mesozoic Petrotectonic Development of the Sawyers Bar Suprasubduction-Zone Arc, Central Klamath Mountains, Northern California. GSA Bull. 1999, 111, 1217–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, C.J.; Irwin, W.P.; Jones, D.L.; Saleeby, J.B. The Ophiolitic North Fork Terrane in the Salmon River Region, Central Klamath Mountains, California. GSA Bull. 1983, 94, 236–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, W.P.; Blome, C.D. Fossil Localities of the Rattlesnake Creek, Western and Eastern Hayfork, and North Fork Terranes of the Klamath Mountains; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2004; p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, H.H.; Snow, C.A.; Ernst, W.G. Geologic-Petrochemical Comparison of Early Mesozoic Mafic Arc Terranes: Western Paleozoic and Triassic Belt, Klamath Mountains, and Jura–Triassic Arc Belt, Sierran Foothills. In Geological Studies in the Klamath Mountains Province, California and Oregon: A Volume in Honor of William P. Irwin; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-8137-2410-2. [Google Scholar]

- Goodge, J.W. Pre-Middle Jurassic Accretionary Metamorphism in the Southern Klamath Mountains of Northern California, USA. J. Metamorph. Geol. 1995, 13, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodge, J.W.; Renne, P.R. Mid-Paleozoic Olistoliths in Eastern Hayfork Terrane Mélange, Klamath Mountains: Implications for Late Paleozoic-Early Mesozoic Cordilleran Forearc Development. Tectonics 1993, 12, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.M.; Saleeby, J.B. Permian and Triassic Paleogeography of the Eastern Klamath Arc and Eastern Hayfork Subduction Complex, Klamath Mountains, California: Evidence from Lithotectonic Associations and Detrital Zircon; Pacific Section SEPM: Fullerton, CA, USA, 1991; pp. 643–652. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, C.G.; Coint, N.; Barnes, M.A.; Chamberlain, K.R.; Cottle, J.M.; Rämö, O.T.; Strickland, A.; Valley, J.W. Open-System Evolution of a Crustal-Scale Magma Column, Klamath Mountains, California. J. Petrol. 2021, 62, egab065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, W.G. Accretionary Terrane in the Sawyers Bar Area of the Western Triassic and Paleozoic Belt, Central Klamath Mountains, Northern California. In Paleozoic and Early Mesozoic Paleogeographic Relations; Sierra Nevada, Klamath Mountains, and Related Terranes; Harwood, D.S., Miller, M.M., Eds.; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 1990; Volume 255, ISBN 978-0-8137-2255-9. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, C.G.; Barnes, M.A. The Western Hayfork Terrane: Remnants of the Middle Jurassic Arc in the Klamath Mountain Province, California and Oregon. Geosphere 2020, 16, 1769–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, W.G. Earliest Cretaceous Pacificward Offset of the Klamath Mountains Salient, NW California–SW Oregon. Lithosphere 2013, 5, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.L.; Irwin, W.P. Structural Implications of an Offset Early Cretaceous Shoreline in Northern California. GSA Bull. 1971, 82, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.D.; Grischuk, J.; Klapper, M.; Schmidt, W.; LaMaskin, T. Middle Jurassic to Early Cretaceous Orogenesis in the Klamath Mountains Province (Northern California–Southern Oregon, USA) Occurred by Tectonic Switching: Insights from Detrital Zircon U-Pb Geochronology of the Condrey Mountain Schist. Geosphere 2024, 20, 749–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, M.C., Jr.; Harwood, D.S.; Helley, E.J.; Irwin, W.P.; Jayko, A.S.; Jones, D.L. Geologic Map of the Red Bluff 30’ × 60’ Quadrangle, California 1999. Available online: https://pubs.usgs.gov/imap/2542/ (accessed on 17 January 2026).

- Sundell, K.E.; Gehrels, G.E.; Pecha, M.E. Rapid U-Pb Geochronology by Laser Ablation Multi-Collector ICP-MS. Geostand. Geoanalytical Res. 2021, 45, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubatto, D. Zircon: The Metamorphic Mineral. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2017, 83, 261–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakymchuk, C.; Kirkland, C.L.; Clark, C. Th/U Ratios in Metamorphic Zircon. J. Metamorph. Geol. 2018, 36, 715–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharman, G.R.; Sharman, J.P.; Sylvester, Z. detritalPy: A Python-Based Toolset for Visualizing and Analysing Detrital Geo-Thermochronologic Data. Depos. Rec. 2018, 4, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutts, D.S.; Matthews, W.A.; Hubbard, S.M. Assessment of Widely Used Methods to Derive Depositional Ages from Detrital Zircon Populations. Geosci. Front. 2019, 10, 1421–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeesch, P. Maximum Depositional Age Estimation Revisited. Geosci. Front. 2021, 12, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeesch, P. IsoplotR: A Free and Open Toolbox for Geochronology. Geosci. Front. 2018, 9, 1479–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, T. Detrital Zircons as Tracers of Sedimentary Provenance: Limiting Conditions from Statistics and Numerical Simulation. Chem. Geol. 2005, 216, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleeby, J.B.; Harper, G.D. Tectonic Relations Between the Galice Formation and the Condrey Mountain Schist, Klamath Mountains, Northern California. In Mesozoic Paleogeography of the Western United States—II; Dunne, G.C., McDougall, K.A., Eds.; SEPM (Society for Sedimentary Geology): Claremore, OK, USA, 1993; pp. 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, G.D. Structure of Syn-Nevadan Dikes and Their Relationship to Deformation of the Galice Formation, Western Klamath Terrane, Northwestern California. In Geological Studies in the Klamath Mountains Province, California and Oregon: A Volume in Honor of William P. Irwin; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-8137-2410-2. [Google Scholar]

- Lanphere, M.A.; Jones, D.L. Cretaceous Time Scale from North America. In Contributions to the Geologic Time Scale; Cohee, G.V., Glaessner, M.F., Hedberg, H.D., Eds.; American Association of Petroleum Geologists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1978; Volume 6, ISBN 978-1-62981-200-7. [Google Scholar]

- Urda, D.; Metcalf, K.; Diaz, J. Development and Evolution of the Rattlesnake Creek Terrane, Klamath Mountains, Northern California. Geosciences 2026, 16, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankinen, E.A.; Irwin, W.P. Review of Paleomagnetic Data from the Klamath Mountains, Blue Mountains, and Sierra Nevada; Implications for Paleogeographic Reconstructions. In Paleozoic and Early Mesozoic Paleogeographic Relations; Sierra Nevada, Klamath Mountains, and Related Terranes; Harwood, D.S., Miller, M.M., Eds.; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 1990; Volume 255, ISBN 978-0-8137-2255-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mankinen, E.A.; Grommé, C.S.; Irwin, W.P. Paleomagnetic Contributions to the Klamath Mountains Terrane Puzzle—A New Piece from the Ironside Mountain Batholith, Northern California. Tectonophysics 2013, 608, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, W.R. Geodynamic Interpretation of Paleozoic Tectonic Trends Oriented Oblique to the Mesozoic Klamath-Sierran Continental Margin in California. In Paleozoic and Triassic Paleogeography and Tectonics of Western Nevada and Northern California; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-8137-2347-1. [Google Scholar]

- Schweickert, R.A. Jurassic Evolution of the Western Sierra Nevada Metamorphic Province. In Late Jurassic Margin of Laurasia—A Record of Faulting Accommodating Plate Rotation; Anderson, T.H., Didenko, A.N., Johnson, Khanchuk, A.I., MacDonald, J.H., Jr., Eds.; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2015; Volume 513, pp. 299–358. ISBN 978-0-8137-2513-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mankinen, E.A.; Irwin, W.P.; Blome, C.D. Far-Travelled Permian Chert of the North Fork Terrane, Klamath Mountains, California. Tectonics 1996, 15, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinny, P.D.; Clark, C.; Kirkland, C.L.; Hartnady, M.; Gillespie, J.; Johnson, T.E.; McDonald, B. How Old Are the Jack Hills Metasediments Really?: The Case for Contamination of Bedrock by Zircon Grains in Transported Regolith. Geology 2022, 50, 721–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surpless, K.D. Hornbrook Formation, Oregon and California: A Sedimentary Record of the Late Cretaceous Sierran Magmatic Flare-up Event. Geosphere 2015, 11, 1770–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surpless, K.D.; Beverly, E.J. Understanding a Critical Basinal Link in Cretaceous Cordilleran Paleogeography: Detailed Provenance of the Hornbrook Formation, Oregon and California. GSA Bull. 2013, 125, 709–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, T.H. Stratigraphy of the Cretaceous Hornbrook Formation, Southern Oregon and Northern California; U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, I.-C.; Niem, A.R.; Niem, W.A. Schematic Fence Diagram of the Southern Tyee Basin, Oregon Coast Range, Showing Stratigraphic Relationships of Exploration Wells to Surface Measured Sections; Department of Geology and Mineral Industries: Portland, OR, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, R.J.; Dumitru, T.A. Eocene Initiation of the Cascadia Subduction Zone: A Second Example of Plume-Induced Subduction Initiation? Geosphere 2019, 15, 659–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, R.; Bukry, D.; Friedman, R.; Pyle, D.; Duncan, R.; Haeussler, P.; Wooden, J. Geologic History of Siletzia, a Large Igneous Province in the Oregon and Washington Coast Range: Correlation to the Geomagnetic Polarity Time Scale and Implications for a Long-Lived Yellowstone Hotspot. Geosphere 2014, 10, 692–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, M.J.; Cashman, S.M.; Langenheim, V.E.; Team, T.C.; Christensen, D.J. Neogene Faulting, Basin Development, and Relief Generation in the Southern Klamath Mountains (USA). Geosphere 2023, 20, 137–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J. Palynology and Paleoecology of the Tertiary Weaverville Formation, Northwestern California, USA. Palynology 1989, 13, 195–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, W.P. Geologic Map of the Weaverville 15’ Quadrangle, Trinity County, California; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, W.P. Reconnaissance Geologic Map of the Hayfork 15’ Quadrangle, Trinity County, California; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aalto, K.R. The Klamath Peneplain: A Review of J.S. Diller’s Classic Erosion Surface. In Geological Studies in the Klamath Mountains Province, California and Oregon: A Volume in Honor of William P. Irwin; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-8137-2410-2. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, L. Depositional/Tectonic History of the Plio-Pleistocene Crescent City/Smith River, Del Norte County, California. In Field Guide to the Late Cenozoic Subduction Tectonics & Sedimentation of Northern Coastal California; Carver, G.A., Aalto, K.R., Eds.; The Pacific Section American Association of Petroleum Geologist: Bakersfield CA, USA, 1992; Volume GB 71, ISBN 978-1-7320148-2-4. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitru, T.A.; Ernst, W.G.; Wright, J.E.; Wooden, J.L.; Wells, R.E.; Farmer, L.P.; Kent, A.J.R.; Graham, S.A. Eocene Extension in Idaho Generated Massive Sediment Floods into the Franciscan Trench and into the Tyee, Great Valley, and Green River Basins. Geology 2013, 41, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, T.A.; Elder, W.P.; Hourigan, J.K.; Chapman, A.D.; Graham, S.A.; Wakabayashi, J. Four Cordilleran Paleorivers That Connected Sevier Thrust Zones in Idaho to Depocenters in California, Washington, Wyoming, and, Indirectly, Alaska. Geology 2016, 44, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleeby, J.; Ducea, M.; Clemens-Knott, D. Production and Loss of High-Density Batholithic Root, Southern Sierra Nevada, California. Tectonics 2003, 22, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt, G.E.; Cashman, S.M.; Garver, J.I.; Bigelow, J.J. Thermotectonic Evidence for Two-Stage Extension on the Trinity Detachment Surface, Eastern Klamath Mountains, California. Am. J. Sci. 2010, 310, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt, G.E.; Harper, G.D.; Heizler, M.; Roden-Tice, M. Cretaceous Sedimentary Blanketing and Tectonic Rejuvenation in the Western Klamath Moutains: Insights from Thermochronology. Cent. Eur. J. Geosci. 2010, 2, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Name | Location | Unit | Rock type | Age (Ma) | Age Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude | Longitude | Study Area | |||||

| 7.11.20.1KM | 41.37426° | −123.45321° | Salmon River | WHT | Metavolcaniclastic | 171 (145) | Deposition (Pb loss) |

| 7.9.20.3KM | 41.27406° | −123.28116° | Salmon River | Wooley Creek suite | Intermediate volcanic | 158 | Deposition |

| WW23005 | 40.44735° | −122.90014° | Wildwood | NFT | Sandstone | - | - |

| WW23020 | 40.44835° | −122.89793° | Wildwood | NFT | Sandstone | - | - |

| WW23021 | 40.44966° | −122.89394° | Wildwood | NFT | Sandstone | - | - |

| WW23002 | 40.42667° | −122.94772° | Wildwood | EHT | Amphibolite matrix | 69 | Pb loss |

| WW23007 | 40.40872° | −122.99464° | Wildwood | EHT | Mafic volcanic matrix | - | - |

| WW23011 | 40.42701° | −122.96702° | Wildwood | EHT | Sandstone matrix | - | - |

| WW23014 | 40.43134° | −122.96192° | Wildwood | EHT | Mafic volcanic matrix | - | - |

| WW23015 | 40.43312° | −122.95611° | Wildwood | EHT | Sandstone matrix | - | - |

| WW23016 | 40.43840° | −122.95302° | Wildwood | EHT | Sandstone matrix | - | - |

| WW23019 | 40.45584° | −122.94307° | Wildwood | Granodiorite suite | Felsic dike | 143 | Intrusion |

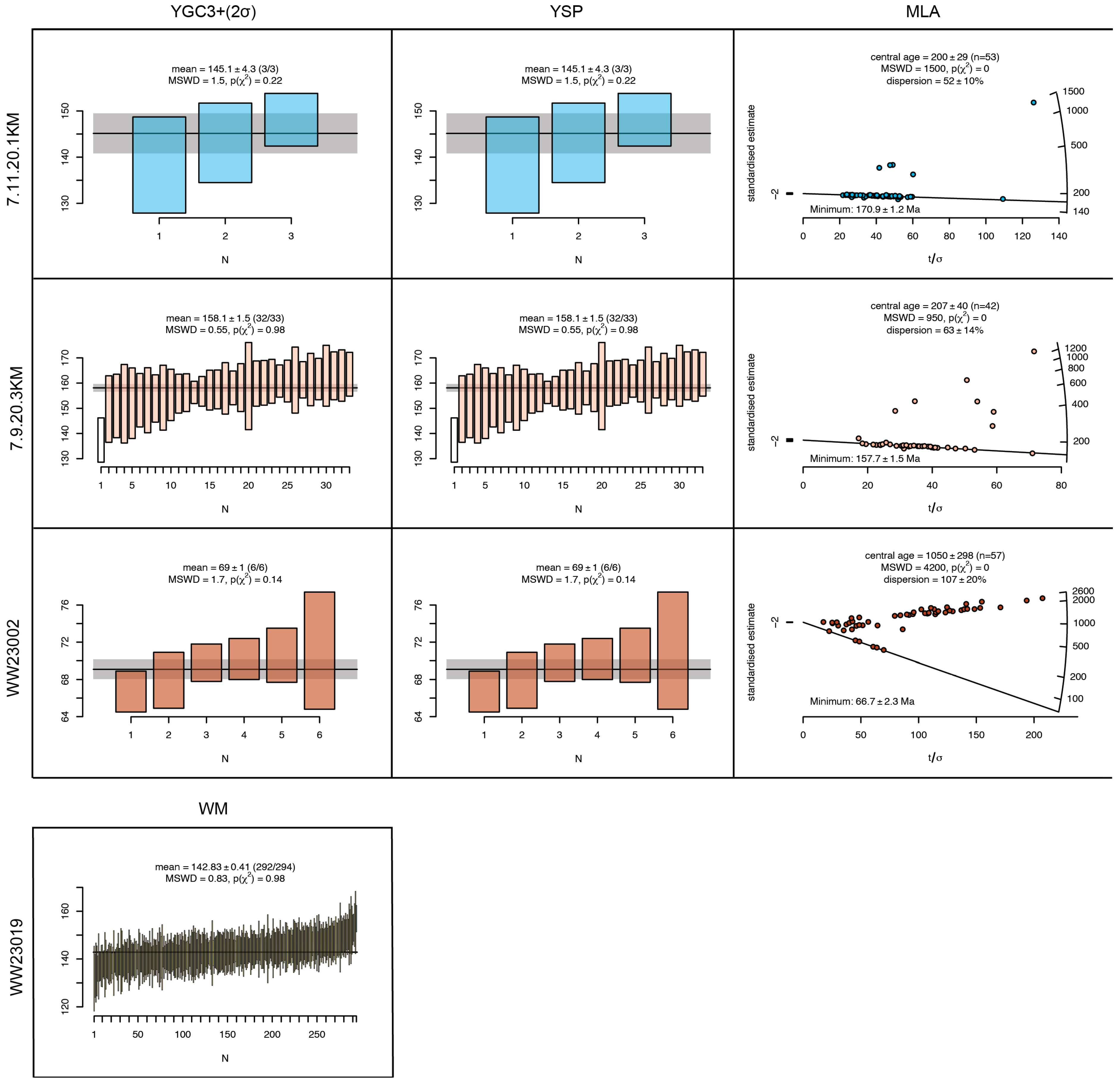

| Sample Name | YSG (2σ) | YGC3+ (2σ) | YSP | MLA | n | % | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ± 2σ (Ma) | Age ± 2σ (Ma) | MSWD | n | Age ± 2σ (Ma) | MSWD | n | Age ± 2σ (Ma) | Mz | Pz | Ptz | A | pre-Mz | ||

| 7.11.20.1KM | 138.3 ± 10.4 | 145.1 ± 4.3 | 1.5 | 3 | 145.1 ± 4.3 | 1.5 | 3 | 170.9 ± 1.2 | 53 | 91 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 9 |

| 7.9.20.3KM | 137.4 ± 8.8 | 158.1 ± 1.5 | 0.55 | 32 | 158.1 ± 1.5 | 0.55 | 32 | 157.7 ± 1.5 | 42 | 83 | 5 | 12 | 0 | 17 |

| WW23015 | 232 | 0 | <1 | 74 | 25 | 100 | ||||||||

| WW23016 | 269 | 0 | 0 | 75 | 25 | 100 | ||||||||

| WW23002 | 66.7 ± 2.2 | 69 ± 1 | 1.7 | 6 | 69 ± 1 | 1.7 | 6 | 66.7 ± 2.3 | 57 | 12 | 4 | 79 | 5 | 88 |

| Sample Name | Weighted mean | n | % | |||||||||||

| Age ± 2σ (Ma) | MSWD | n | Mz | Pz | PtZ | A | pre-Mz | |||||||

| WW23019 | 142.83 ± 0.41 | 0.83 | 292 | 294 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Metcalf, K.; Guyer, J.; Camargo Ramirez, J. Something Old, Something New: Revisiting Terranes of the Western Paleozoic and Triassic Belt, Klamath Mountains, Northern California. Geosciences 2026, 16, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16020054

Metcalf K, Guyer J, Camargo Ramirez J. Something Old, Something New: Revisiting Terranes of the Western Paleozoic and Triassic Belt, Klamath Mountains, Northern California. Geosciences. 2026; 16(2):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16020054

Chicago/Turabian StyleMetcalf, Kathryn, Jenna Guyer, and Joana Camargo Ramirez. 2026. "Something Old, Something New: Revisiting Terranes of the Western Paleozoic and Triassic Belt, Klamath Mountains, Northern California" Geosciences 16, no. 2: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16020054

APA StyleMetcalf, K., Guyer, J., & Camargo Ramirez, J. (2026). Something Old, Something New: Revisiting Terranes of the Western Paleozoic and Triassic Belt, Klamath Mountains, Northern California. Geosciences, 16(2), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16020054