Abstract

Morphological variability on Mediterranean embayed sandy beaches is largely driven by wave storms and episodic sediment inputs from local streams during intense rainfall. While storm impacts are well documented, the combined influence of stream discharge, wave forcing and morphological response remains poorly understood. This study examines these interactions at Castell beach, one of the few non-urbanised, stream-fed embayed beaches on the northwestern Mediterranean, during two high-energy storms with heavy rainfall: December 2019 and January 2020 (Storm Gloria). Morphological changes in the subaerial and submerged beach, and stream dynamics were assessed using repeated RTK–GNSS surveys, orthophotos and echo-sounder bathymetry. Results show the stream mouth shifted along the beach (east, central or west) during heavy rainfall episodes depending on wave direction and pre-existing topography, tending toward more wave-sheltered zones. The storms induced contrasting responses: the first caused slight subaerial accretion, whereas Storm Gloria produced subaerial erosion and nearshore sediment deposition from both beach and stream sources. This material was subsequently reworked and reincorporated into the subaerial beach under calmer conditions, with full recovery by February 2022. These findings highlight the role of stream–wave interactions in sediment dynamics and the capacity of highly protected embayed beaches to adapt to extreme events.

1. Introduction

Embayed beaches, bounded by rocky headlands and outcrops, are primarily controlled by their geological framework [1]. These boundaries influence beach dynamics by constraining longshore sediment transport within the embayment and limiting the impact of high-angle incoming waves [2,3]. It has been observed that these beaches exhibit common behaviours on a regional scale, such as shoreline retreat due to sea level rise or a reduction on sediment input [4,5]; or in terms of shoreline rotation on monthly to decadal time scales, caused by variations in wave directions due to mesoscale climate fluctuations, seasonal changes in wave climate or offshore bathymetric changes [6,7,8,9]. However, many studies highlight variable beach behaviour at short-term scale at both regional [10] and local scale, with even distinct responses to the same forcing observed among embayed beaches within the same bay [3]. These differences underscore the interest of studying the embayed beaches individually at short-term due to their great variability in wave exposure, sediment size, beach slope, sediment inputs and seabed geomorphology [11].

Beyond geological constraints, natural embayed beaches are often fed by streams, providing their primary sediment source [2]. In Mediterranean climates, most discharge is associated with episodic high-flow events, when even small streams can deliver significant amounts of sediment to these beaches over short periods of intense rainfall [12]. These sediment inputs may lead to beach accretion periods following floods and can alter both beach morphology and sediment texture, potentially influencing coastal dynamics for decades [2,13,14]. Coastal storms are another major driver of morphological change on microtidal sandy embayed beaches [15,16,17], generating beach and dune erosion, inundation and overwash, shoreline rotation, rip currents, and cross-shore sediment transport beyond the bay (e.g., [10,16,18]). When a coastal storm coincides with a heavy rainfall episode, wave-induced erosion can be counterbalanced by sediment supplied from streams [14]. However, the contribution of sediment from small streams to the beach remains largely unknown, and the interactions between the stream, the nearshore, and the shoreface under storm conditions have been scarcely studied, particularly in the latter. Given the projected climate change scenarios, in which storm impacts are expected to be exacerbated by rising sea levels and shifts in rainfall patterns affecting sediment delivery, it is crucial to understand not only the beach’s response to storm events but also its subsequent recovery, strongly influenced by these sediment inputs. This understanding is essential for effective coastal management.

This work examines the geomorphological response of a microtidal, natural embayed beach fed by a small stream on the NW Mediterranean to extreme waves and rainfall events between December 2019 and January 2020, as well as its post-storm recovery. The aim of this study is to investigate the interactions between coastal storms and stream dynamics during extreme events and their influence on the morphodynamics of the subaerial beach and shoreface. Our results reveal how the stream mouth shifts along the beach in response to wave and topographic conditions, how sediment from both the stream and the beach is redistributed during storm events, and how the beach subsequently recovers, providing new insights into the resilience of natural embayed beaches to extreme events.

2. Study Site

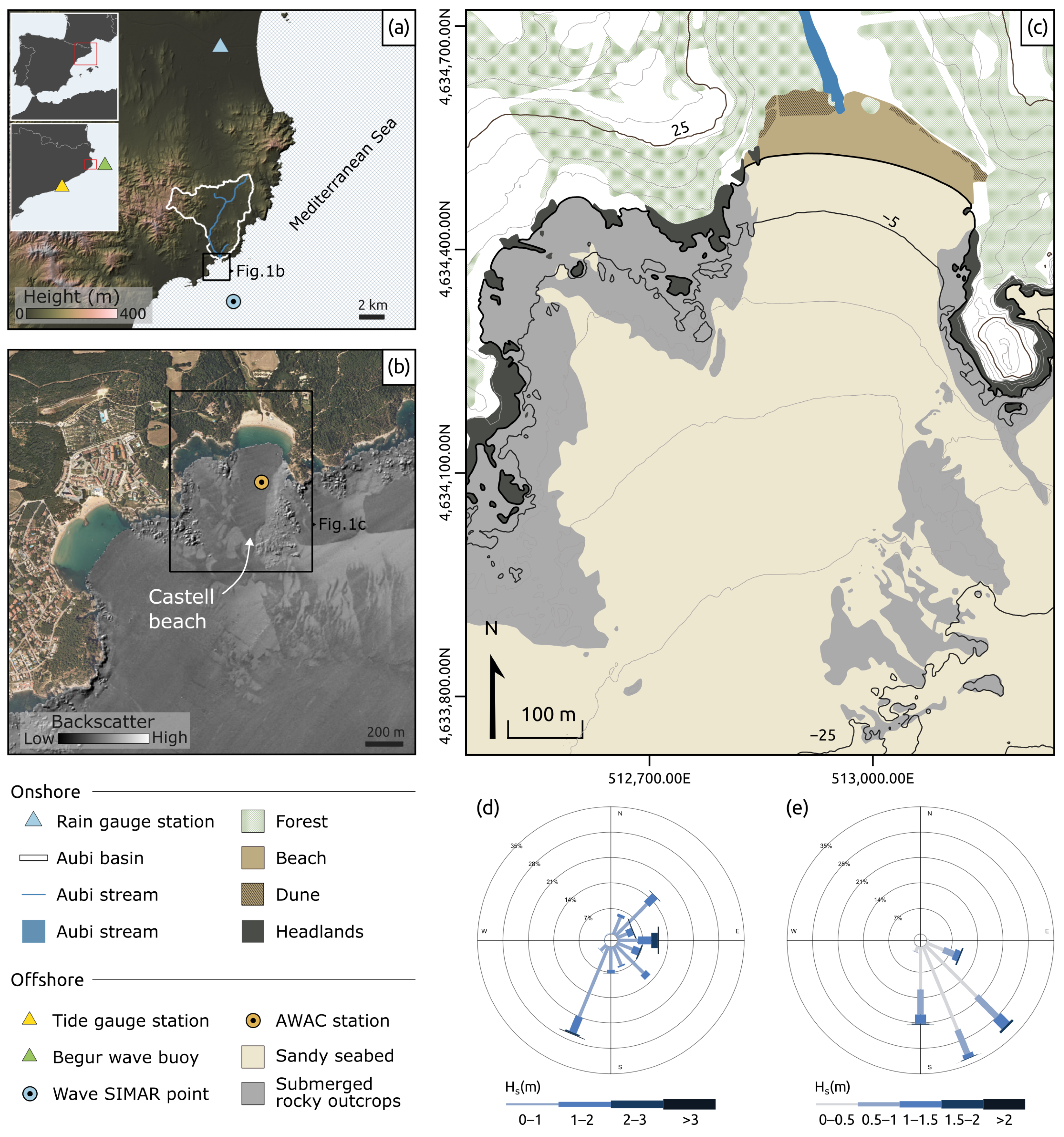

Castell beach is a low-lying, sandy embayed beach located on the northern coast of Catalonia (NW Mediterranean) (Figure 1a). It stretches 320 m in length, is approximately 87 m wide, and has an average median grain size of 490 µm [5]. The beach is backed by a small area of vegetated dunes, which have been cordoned off for protection since 2019, and a wetland area in the central sector associated with the Aubi stream, which discharges into the beach (Figure 1c). It is framed by headlands 10–30 m high, extending to submerged depths of 20–25 m and reaching approximately 270 m and 710 m seaward from the shoreline on the western and eastern sides, respectively, in plan view (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

(a) Location map of Castell beach, including the location of the tide gauge station (Barcelona II), Begur buoy, Torroella de Montgrí rainfall station and SIMAR 2122142 point; and Aubi stream and its drainage basin. (b) Orthophoto collected in 2020 and a backscatter map of shoreface, including the location of the AWAC. (c) Cartographic map of the main features of the area. (d,e) Wave roses of SIMAR 2122142 point (d) and AWAC (e) during the AWAC deployment period (March–July 2020). Subaerial topography in (a), orthophoto in (b) and forest land use in (c) were provided by the Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya; while backscatter data in (b) are part of the ESPACE Project dataset (2004).

One uncommon value of Castell beach stems from its almost non-urbanised landscape, which preserves agricultural and forestry land uses, in contrast to the predominantly urbanised Catalan coast, providing an example of the Catalan coastal landscape before urbanisation began in the 1950s [19]. The preservation of Castell beach and its surrounding landscape was driven by local civic action that successfully halted urban development in the 1990s, leading to its classification as non-developable land and its inclusion in the PEIN Castell–Cap Roig since 2003 [20].

A previous analysis of Castell beach’s medium-term evolution from 1945 to 2021 revealed an overall shoreline stability, with a mean rate of change of per year. Within this generally stable trend, the shoreline advanced between 1990 and 1996 before experiencing a net retreat from the late 1990s onwards, with a shoreline change rate of [5].

The main source of sediment is the material provided by the Aubi stream [19], which drains a catchment area of over a length of approximately 8 km (Figure 1a). The stream is characterised by a Mediterranean torrential regime with a seasonal behaviour. Its flow to the sea is typically obstructed by a sandy mouth bar, leaving the stream stagnant in the central wetland area (Figure 1c) and seaward discharges occur during short, intense flood events. Alongside the stream, poorly consolidated alluvial deposits are found [19]. Average annual precipitation in the surrounding area is ~600 mm, based on data from the Torroella de Montgrí rain gauge station between 2012 and 2022 (Figure 1a).

Castell area is a microtidal coast, with a tidal range lower than 0.2 m. It has a seasonal wave climate with higher energy conditions during fall and winter [21]. In deep waters, the most severe storms are from the north, northeast and east, while less-energetic storms arrive from the south [22]. Due to the headlands that enclose the Castell beach, only waves approaching from directions between south and east can enter the embayment, with those from the east refracting into a south-easterly direction upon reaching the shore [23] (Figure 1d,e). The geometry of the headlands also leads to limited longshore sediment transport.

Statistical analysis of wave conditions offshore of Castell beach, based on data from the Begur wave buoy (Puertos del Estado, www.puertos.es (accessed on 4 December 2024)) from 2012 to 2022, revealed a mean significant wave height () of , a maximum of , and an absolute maximum wave height of . Even though most frequent storms had an between and , severe and extreme events ( up to or higher than , respectively) also impacted this sector of the Catalan coast [24,25]. Notably, the extreme storm of January 2020, known as Storm Gloria, stands out as the most severe event recorded along the Catalan Coast, with a recurrence period exceeding 30 years [26]. This storm was characterised by strong north-easterly winds (mean speed of 15 m s−1) that triggered storm surges of up to 70 cm and significant wave heights exceeding 8 m in deep waters [25,27]. Additionally, it was accompanied by intense rainfall, up to 400 mm in one day [28]. Observations at Castell beach indicate that the impact of Storm Gloria reached the seabed down to ~25 m water depth, destroying submerged infrastructures, such as the outfall that discharges at this depth, and altering the seafloor morphology, resulting in a pronounced attenuation of bedforms and the partial disappearance of ripples (see Supplementary Material, Figure S1).

3. Data Sets and Methods

3.1. Storm and Rainfall Events

Wave hourly data between November 2019 and February 2022 from the SIMAR dataset (Puertos del Estado, www.puertos.es (accessed on 20 September 2024)) were analysed to identify coastal storms. The dataset is made up of a time series of wind and wave parameters obtained through numerical modelling (further details available at the same website). Time series of significant wave height (), peak period () and wave direction () were extracted from the nearest SIMAR point to Castell beach (2122142), located ~4 km offshore (Figure 1a). To assess the accuracy of the SIMAR dataset, its values were compared to observational data from the Begur wave buoy (Puertos del Estado), positioned ~35 km offshore at a depth of (Figure 1a). During the study period, the analysis revealed a correlation coefficient of 0.80 for (0.76 for and 0.72 for wave direction), with the mean difference between observed and modelled values calculated as . A significant coastal storm is defined here according to the criteria proposed by [22] for the Catalan coast: higher than at the peak of the storm and a minimum duration of 12 h above a threshold of . Wave height can be below the threshold for 6 h during the storm. Further, if the interval between two consecutive storms was shorter than 12 h, it was considered as a single double-peaked storm, as proposed by [29]. The erosive potential of storms was assessed using the storm power index () proposed by [30]:

where and define the beginning and the end of the storm (). Storm-induced water level () was estimated following [31] to assess hydrodynamic conditions during the study period. represents the highest elevation of the landward margin of swash relative to a defined vertical datum, accounting for the astronomical tide, storm surge and the wave induced runup (). The runup component () was calculated using Stockdon’s empirical parametrisation [32] for offshore wave conditions, which depends on the foreshore slope, deep-water wave height, and wavelength. A constant foreshore slope of , estimated by [5], was used. Water levels (), which include both astronomical tide and storm surge, were obtained from hourly records of Barcelona II tide gauge (Puertos del Estado) (Figure 1a).

Precipitation data were obtained from the Torroella de Montgrí station (Figure 1a), an automatic meteorological station from the Servei Meteorològic de Catalunya (www.meteo.cat (accessed on 23 September 2024)). This is the nearest available station, located north of the beach and outside the Aubi stream drainage basin. The data consist of semi-hourly accumulated rainfall (mm). Although there is no straightforward relationship between rainfall and sediment yield to the coast, the reactivation of the stream at Castell beach clearly coincides with periods of high rainfall, so sediment delivery to the beach can only occur during such events. Comparison with the current rain gauge within the Aubi drainage basin, available from 2021, shows a correlation of 0.75 on rainy days and an RMSE of 4.3 mm.

3.2. Morphological Data

The study considers topo-bathymetric surveys (Table 1) from the subaerial beach to a depth 27 m carried out during the study period. Five field campaigns took place at Castell beach between November 2019 and October 2020 (Table 1). The data used to characterise the morphological beach response to extreme events include repeated RTK–GNSS topographies, single and multibeam echosounder bathymetries. Additionally, two topographies surveys were performed in 2021 and 2022. All data were recorded in the European Terrestrial Reference System 1989 (ETRS89) projected to the Universal Transverse Mercator system (zone 31N) and referenced to the geoid EGM08D595. Survey domains are shown at Figure S2.

Table 1.

Field campaigns at Castell beach during the study period. Dashed lines separate surveys from storm events.

Topographic data were collected using a real-time kinematic global positioning system (RTK–GNSS) mounted on a backpack. Continuous walking measurements were conducted along the dry beach and the swash zone, following a series of U-shaped paths that extended down to approximately ~0.1 m, with an average spacing of 10–15 m between paths (Figure S2b). During two of the surveys that coincided with bathymetric campaigns (Surveys 3 and 4, Table 1), additional cross-shore profiles were collected in the swash zone with an approximate spacing of 10 m between profiles, covering a vertical range from ~0.5 m to −1 m (Figure S2b). RTK–GNSS data have a horizontal accuracy of <1 cm and a vertical accuracy of <2 cm. Digital elevation models (DEMs) with a 1 m grid resolution were generated from the processed topographic data using the TIN interpolation function (Triangulated Irregular Network) in QGIS 3.22 software.

Bathymetric data were recorded using a single beam echosounder in the November 2019 campaign and a R2Sonic multibeam echosounder in January and July 2020 campaign. Bathymetry datasets were post-processed using HYPACK 2019 software. Corrections for heading, pitch, roll, and heave, as well as navigation adjustments were applied. Erroneous soundings were removed, and the filtered data were then gridded into 2 m digital elevation models (DEMs). For the multibeam surveys, data acquired with the R2Sonic system achieved a typical vertical accuracy of ~1.5 cm (1.5 cm + 1 ppm) using RTK–GNSS, supported by precise motion sensors and heave compensation.

Complementary data sources used to characterise stream position and subaerial beach variability included:

- LiDAR-derived topographic data: Six airborne LiDAR surveys conducted between 2012 and 2017, provided by ICGC, produced 1 m resolution digital elevation models (DEMs). The vertical accuracy of LiDAR data was evaluated by [16]; additional details on acquisition dates are available in [5].

- Sentinel-2 satellite imagery: Orthorectified satellite images with a spatial resolution of 10 m, spanning from 2015 to 2024. The images used were filtered based on a cloud coverage threshold to ensure data quality.

- Orthophotos: High-resolution aerial orthophotos provided by ICGC, available annually throughout the study period. Additionally, orthophotos acquired just after storm events (e.g., 24 January 2017, 7 December 2019, and 27 January 2020) were also employed.

3.3. Morphological Analysis

Morphological changes were assessed using QGIS 3.22 software by integrating the processed topographic and bathymetric data. Analyses were conducted separately for the emerged (subaerial) and submerged areas of the beach. For the subaerial beach, volumetric changes were calculated by subtracting the DEMs obtained from consecutive surveys. For each survey, the subaerial beach was defined as the area between the shoreline and the landward limit, taken as the first line of vegetation or the start of the dune zone (Figure S2a), with the same landward limit applied across all datasets. Shoreline was defined as the horizontal position corresponding to the maximum high sea level measured during the survey days, referred to the geoid EGM08D595 and derived from historical records of the Barcelona II tide gauge (Figure 1a), resulting in an elevation of 0.542 m. Subaerial beach volume was calculated above m, considering a beach length of 320 m for the computation of volume per linear metre. The stream outlet position was visually identified from slope and elevation distributions in the topographic data. The dune area was excluded from volume change analysis between survey 1 (29 November 2019) and survey 2 (11 December 2019) due to missing data, but included for subsequent surveys (Figure S2a). For the submerged beach, altimetric changes were obtained by subtracting DEMs between surveys. Changes within the first 30 m from the shoreline (approximately −1.5 m depth) could not be assessed between the bathymetric data of survey 1 (29 November 2019) and survey 3 (29 January 2020) due to a lack of data in this area in survey 1.

4. Results

4.1. Forcing Conditions

Based on wave conditions, two major storms impacted Castell beach during the study period, with onsets on 3 December 2019 and 19 January 2020 (Figure 2, Table 2).

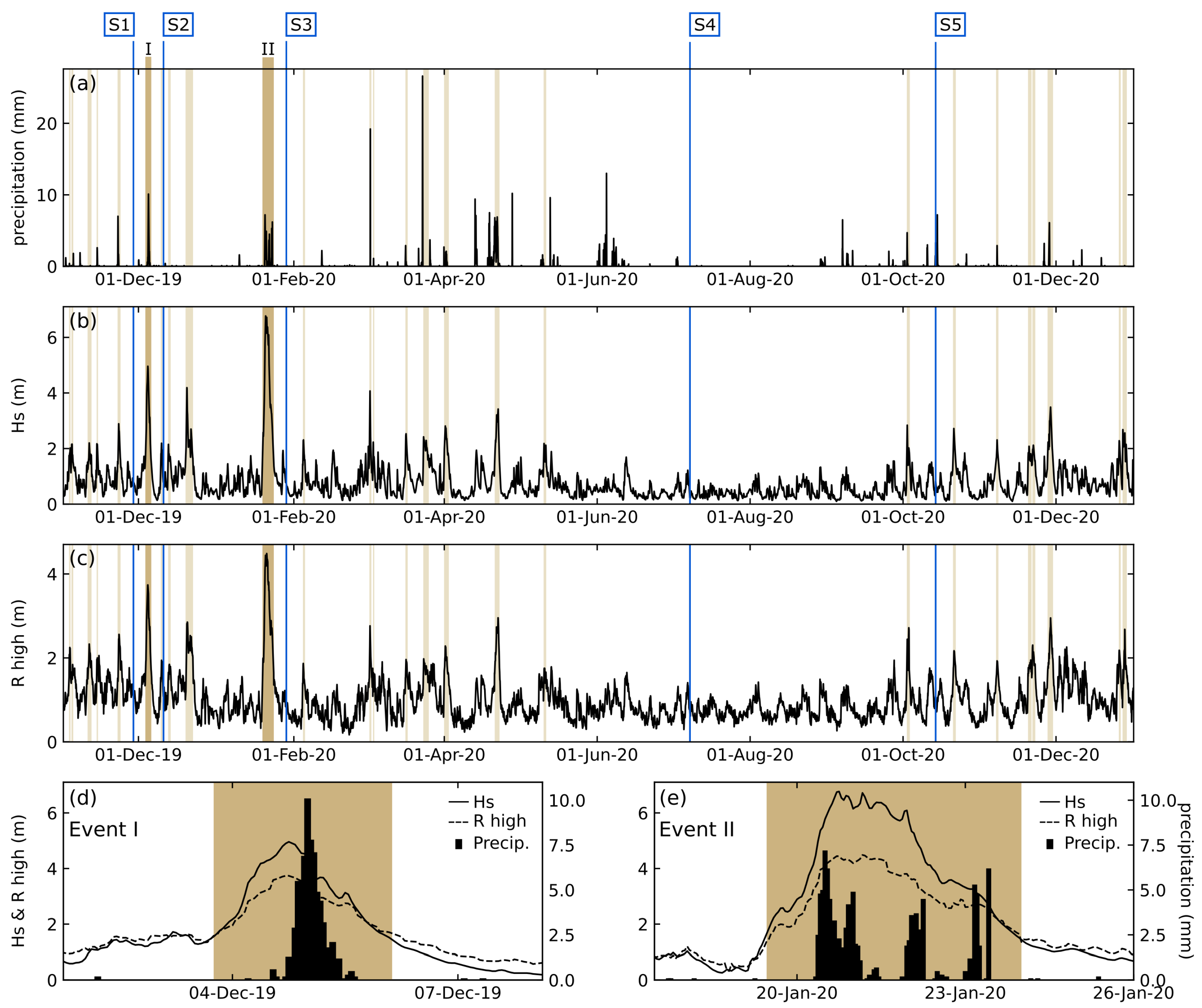

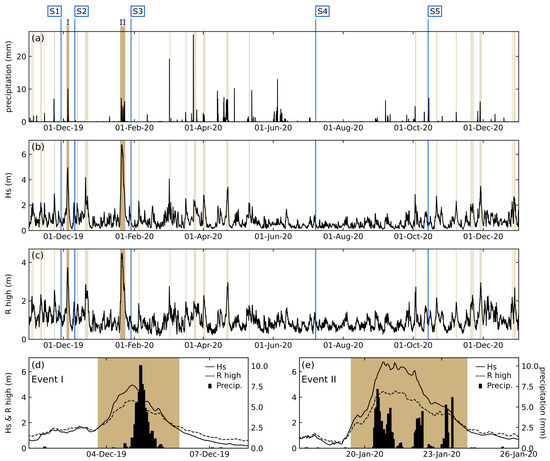

Figure 2.

Time series of (a) hourly precipitation and (b) significant wave height , derived from Torroella de Montgrí precipitation station and SIMAR point 2122142, respectively (see Figure 1a for location). (c) Maximum storm-induced water level () considering the mean foreshore slope () during the study period. (d,e) Zoomed-in time series of (solid line), (dashed line), and precipitation (black bars) during Events I and II. Yellow bars indicate storm events over the study period, with the most energetic storm highlighted in dark yellow. Survey campaigns (S1 to S5) are indicated by blue boxes above the panels and by blue vertical lines in (a–c); see Table 1 for details.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the most energetic wave events identified during the study period based on wave features.

The most energetic storm, known as ’Gloria’, occurred on 19 January 2020 and hereafter referred to as Event II (Figure 2e). It was characterised by a of 6.8 m, an associated of 12.1 s, and an easterly wave direction. Due to diffraction by the headlands, the waves entered the embayment from the southeast, as evidenced by Sentinel-2 satellite imagery from 23 January 2020 (Figure 3b). According to the storm intensity scale for the Catalan coast proposed by [22], this storm was classified as a Category V (Extreme event), the highest category in the five-level scale. Rainfall associated with the storm began 21 h after the onset of the maritime event and persisted intermittently throughout its duration, reaching a peak intensity of 7.2 mm/h (Figure 2e).

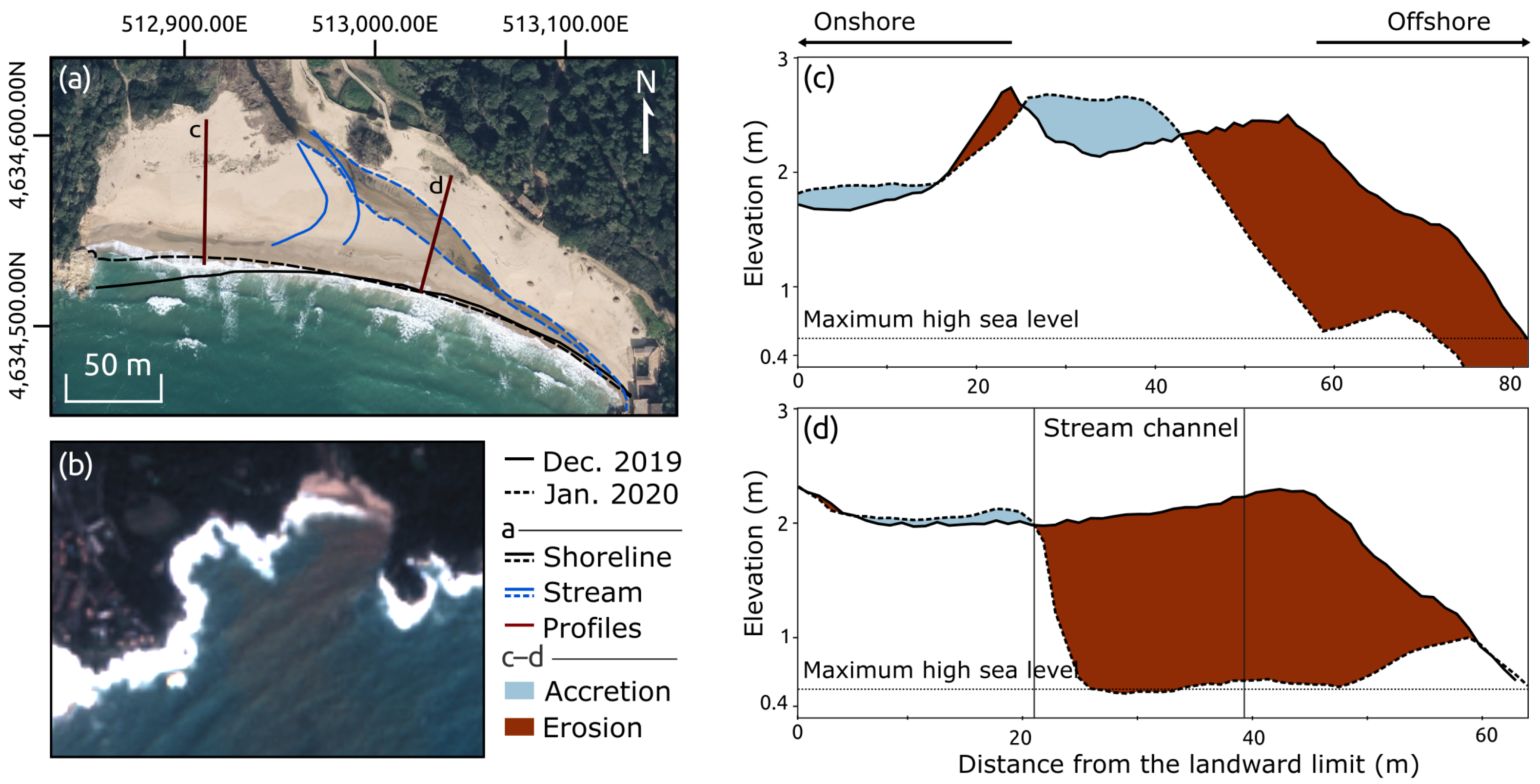

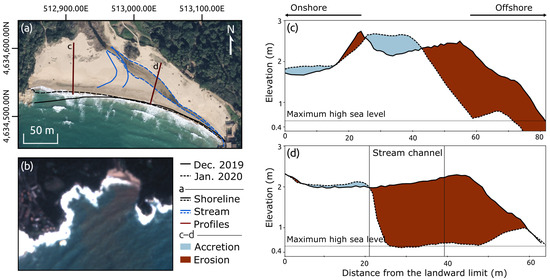

Figure 3.

Summary of Castell beach state surrounding Event II (19 January 2020, Gloria storm). Solid lines indicate the initial state (Survey 2: 12 December 2019), and dotted lines the final state (Survey 3: 29 January 2020). (a) Orthophoto from ICGC on 27 January 2020, including the shoreline and stream position. (b) Sentinel-2 satellite image from 23 January 2020. (c,d) Initial and final beach profiles at Castell beach (locations shown in (a)).

The second most energetic storm began on 3 December 2019, about a month and a half before Event II, and is hereafter referred to as Event I (Figure 2d). It was classified as Category III (Significant event), with a of 3.2 m, an associated of 11.0 s, and an east-northeast wave direction. Rainfall associated with the storm began 19 h after the onset of the maritime event. The precipitation occurred as a short, intense episode, peaking around 10 mm/h shortly after the peak wave conditions.

The remaining maritime storms were lower-intensity events (Category I and II), with maximum significant wave heights () ranging between 2.0 and 4.0 m (Supplementary Material, Table S1). Regarding rainfall events, starting on 19 April 2020, a 50-h precipitation episode occurred alongside a Category II maritime storm, reaching a peak intensity of 5 mm/h and resulting in a total accumulation of 195 mm (Figure 2a; Supplementary Material, Table S1).

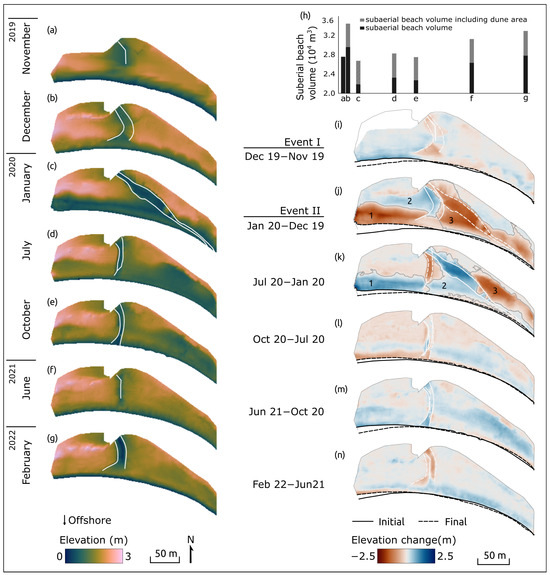

4.2. Morphological Changes in the Subaerial Beach

Between Survey 1 and Survey 2, pre- and post-Event I, respectively (Figure 4a,b), Castell beach experienced subaerial volume gain of (Figure 4h; Table 3). Sediment accumulation was primarily observed on the western sector, along with a mean shoreline advancement of . During this interval, the stream transitioned from being inactive at the back wetland area of the beach to discharging at the central part of the beach, aligning with an erosional zone identified in the same area (Figure 4i).

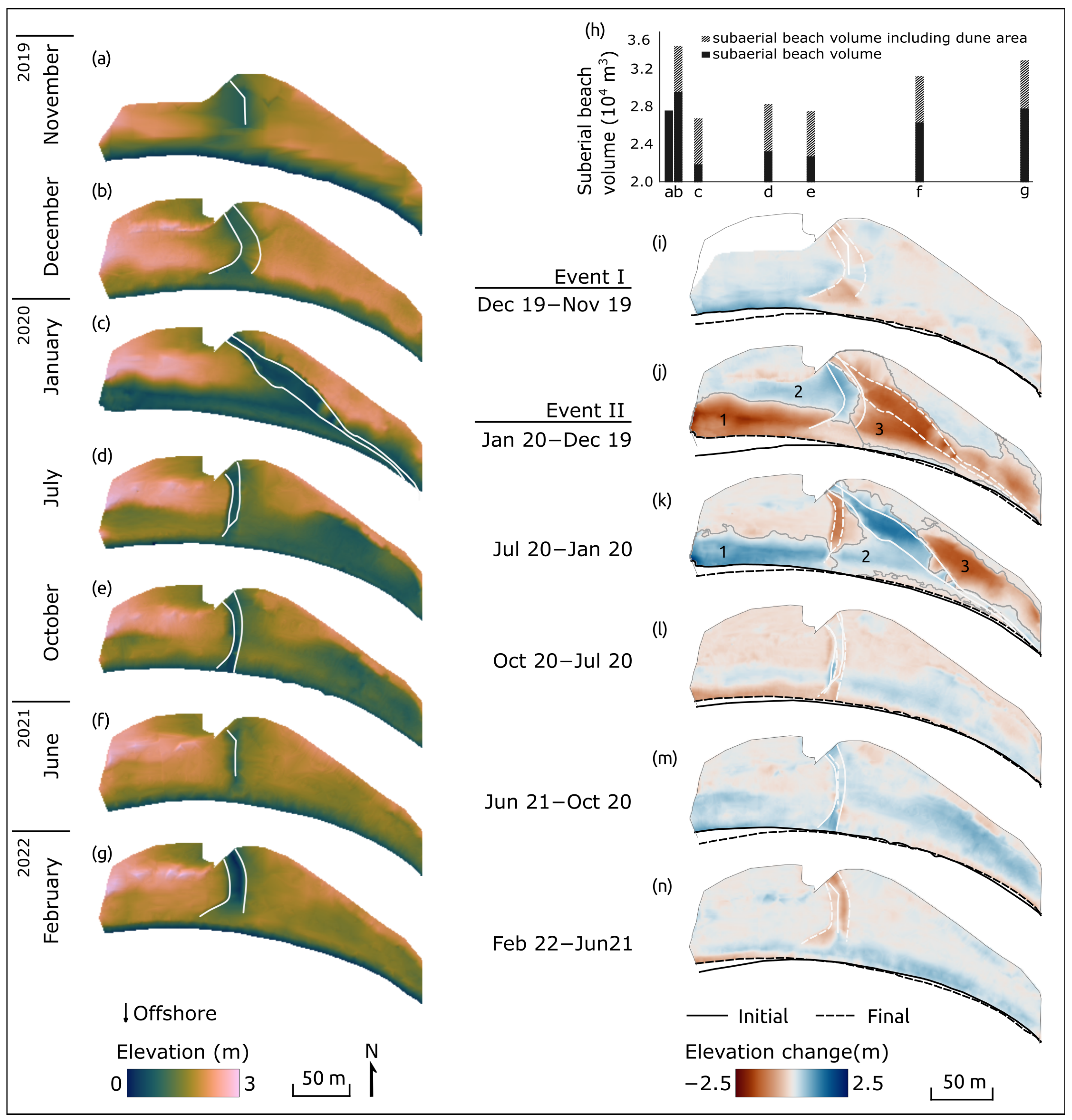

Figure 4.

(a–g) Digital elevation models of the subaerial beach; (h) subaerial beach volume (black bars) and subaerial beach volume including the dune area (hatched bars) for each survey (a–g); and (i–n) morphological changes between campaigns (final−initial; Month yy−Month yy), including differential elevation, shoreline and stream positions (black and white, respectively), with initial (solid line) and final (dashed line) states.

Table 3.

Summary of morphological results of the subaerial beach at Castell. Volume and surface changes are calculated with respect to the previous survey. The highest change is indicated in bold. Dashed lines separate surveys from storm events.

Between Survey 2 and Survey 3, pre-Event II and post-Event II, respectively (Figure 4b,c), Castell beach experienced a net loss of , corresponding to a decrease in subaerial beach volume of (Figure 4h; Table 3). Morphological responses varied along the beach: in the western sector, the beach experienced sediment loss along the beach face (; Figure 3c and Figure 4j, zone 1), accompanied by a shoreline retreat , while sediment deposition occurred on the backshore (; Figure 4j, zone 2). In the eastern sector, erosion coincided with the migration of the stream outlet from the central to the eastern part of the beach, forming an erosive trench that extended from the beach face to the inner boundary of the stream course (; Figure 3d and Figure 4j, zone 3).

During the post-events period, an increase of was noted between Survey 3 and Survey 4 (Figure 4c,d), reflecting a rise in subaerial beach volume (Figure 4h; Table 3). Sediment accumulation was predominantly located along the beach face, extending across the entire length of the beach, and along the previous stream course (Figure 4k, zone 1–2). The effect was most pronounced in the western zone, where a gain of of sediment was recorded (Figure 4k, zone 1), coinciding with a seaward displacement of the shoreline. In the eastern sector, a redistribution of sediment was observed between the backshore (; Figure 4h, zone 3) and the stream course infill and eastern beach face (; Figure 4k, zone 2).

By October 2020 (Survey 5, Figure 4e), the beach showed a slight decrease of approximately in volume and in the subaerial beach surface relative to Survey 4 (Table 3). Despite this decrease since July 2020, the sediment volume remained higher than in Survey 3, representing a net gain of relative to the post-Event II beach condition (Figure 4h). In the following months, the volume of the beach increased by and the area of the subaerial beach increased by by June 2021 (Survey 6) (Figure 4h,m; Table 3). By February 2022 (Survey 7), the beach had almost the same volume as the previous survey (), representing a gain of relative to the previous survey (Figure 4h,n; Table 3). Comparing the initial and final surveys during the study period, the net change in subaerial volume was very small, representing only a variation (), suggesting a complete recovery of the beach from the erosion caused by the Event II (Figure 4h).

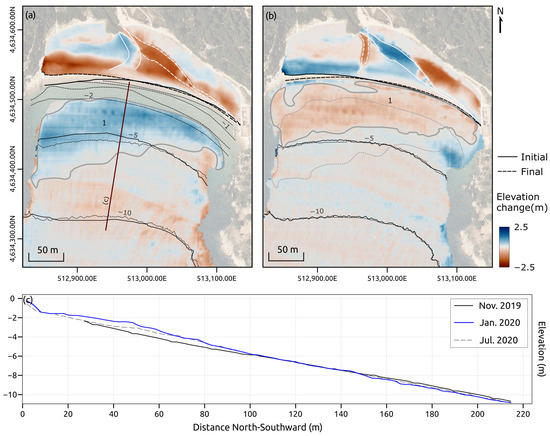

4.3. Morphological Changes in the Shoreface

Regarding bathymetric changes in the submerged zone between Survey 1 (29 November 2019, pre-Event I and II) and Survey 3 (29 January 2020, post-Event I and II), a sediment accumulation of approximately was detected in the nearshore at depths of 1.75 m to 4.5 m in the east and 2 m to 7.5 m in the west (Figure 5a, zone 1). The seabed bathymetry increased on average by , reaching a maximum of . No other major differences were observed, as values remained close to zero (ranging from to ), likely due to the sounding banding effect, an artifact of the data acquisition process (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

Differential elevation at the shoreface of Castell beach between campaigns. (a) Differences between survey 3 (29 January 2020) and survey 1 (29 November 2019) at the shoreface, and between survey 3 and survey 2 (11 December 2019) at the subaerial beach. (b) Differences between survey 4 (08 July 2020) and survey 3 at both subaerial beach and shoreface. (c) Cross-shore profile evolution, profile position is indicated at (a). Changes in the subaerial beach at (a,b) are the same as Figure 4j and Figure 4k, respectively.

Between Survey 3 (29 January 2020) and Survey 4 (8 July 2020), bathymetric differences indicated sediment losses of approximately from the deposit formed by Event II at depths between 1 m and 4 m (Figure 5b, zone 1). The seabed lowered on average by , reaching a maximum of . Beyond 4 m depth, no significant changes were observed, apart from the banding effect (Figure 5b).

5. Discussion

5.1. Modes of Stream Delivery

Small streams and their sediment input during extreme events can play a key role in the sediment budget of small embayed beaches [14]. In these beaches, where headlands and capes regulate wave exposure, the beach response depends not only on the magnitude of sediment input but also on the stream’s position within the bay, which controls sediment availability for redistribution across the embayment [2]. At Castell, the stream is centrally located at the back of the beach, but when activated its outlet can shift alongshore. Consequently, the stream emerges as one of the main drivers of morphological variability across the subaerial beach, as evidenced by subaerial surveys and annual LiDAR data (2012–2017) (Figure 6), rather than affecting only the adjacent beach sector as already reported in other locations [33]. Identifying the mechanisms behind such alongshore shifts is therefore necessary to achieve a better understanding of morphodynamic evolution in embayed beaches.

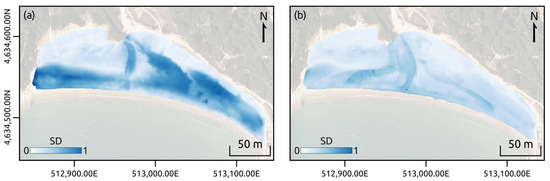

Figure 6.

Beach elevation variability expressed as standard deviation (SD). (a) SD calculated from the study surveys (Table 1, excluding Survey 1 due to differences in spatial coverage compared with the other campaigns). (b) SD calculated from annual LiDAR surveys (2012–2017).

Sentinel-2 imagery from 2015 to 2024 was used to document the configuration of the stream outlet. The satellite data show that the stream discharged onto the beach in only 26 of the 393 cloud-free scenes (72% of the total), highlighting its sporadic activation. Stream activation, defined here as the observed state when the stream reaches the beach, typically occurs either following accumulated precipitation exceeding 40 mm over a few days, or during intense, short-duration rainfall events. As the outlet shifts alongshore, its position could be classified into three main configurations: central, west, and east outlet.

Central outlet position (Figure 7b,f). During most active periods, the stream mouth is located in the central sector of the beach. It flows in a nearly straight line from the stagnant wetland behind (inactive state, Figure 7a,e) until it reaches the sea, approximately perpendicular to the shoreline, as observed in October 2020 during Survey 5 (Figure 4e). Accumulated precipitation during the five days preceding the satellite image showing this stream configuration did not exceed 50 mm. However, during heavy rainfall events, the stream outlet shift from the central sector of the beach toward one of its extremities.

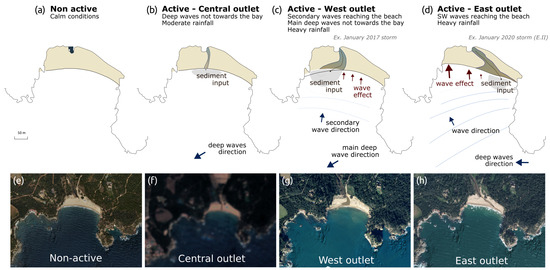

Figure 7.

(a–d) Conceptual diagrams illustrating stream outlet configurations: (a) non-active, (b) central outlet, (c) west outlet, (d) east outlet. (e–h) Corresponding imagery of each configuration: (e) ICGC orthophoto from 16 May 2019, (f) Sentinel-2 image from 17 July 2018, (g) ICGC orthophoto from 24 January 2017, and (h) ICGC orthophoto from 27 January 2020. Arrows indicate wave direction and coastal impact, whereas shaded areas denote sediment accumulation associated with stream input.

West outlet position (Figure 7c,g). The west outlet typically develops after intense rainfall events combined with coastal storms with northeast or east-northeast deep-water waves. The headlands prevent the dominant waves from entering the bay. Secondary low-energy waves still reach the beach, preventing discharge through the central sector and causing the outlet to shift slightly westward. Such conditions were recorded during Event I, with a slight westward outlet migration. A more pronounced case occurred in January 2017, when rainfall comparable to Event II (~120 mm) triggered a clear westward migration of the stream and sediment accumulation on the adjacent subaerial beach (Figure 7g). Consistent with Event I (Table 3), ref. [5] reported an increase in subaerial beach volume between the LiDAR-derived topography of 2016 and that of 2017, after the storm. These observations suggest that under such conditions, the maritime storm does not directly impact the beach but affects the stream mouth position, and the sediment delivered by the stream remains near the outlet, becoming readily available to the subaerial beach.

East outlet position (Figure 7d,h). The east outlet has been observed during concomitant stream activation and maritime storm impacts. For rivers, it is well established that under such conditions there is a temporal shift between the peak of the maritime coastal impact, which occurs first, and the peak of river discharge [34]. Castell beach likely behaves similarly, being partially impacted by waves before stream activation. Eastward outlet migrations of the stream have been observed during storms with easterly or south-easterly wave conditions combined with intense rainfall, such as Event II in January 2020 (Gloria Storm). Under these conditions, the stream could not discharge at its usual outlet due to opposing seawater flow and elevated wave energy. Although the shortest alternative route would have been toward the western sector, its high exposure made it unsuitable for discharge. Consequently, the stream mouth migrated toward the more sheltered eastern sector, following a longer, less direct path until freshwater flow overcame opposing wave forces and allowed discharge.

Other eastward shifts were recorded after coastal storms with deep-water waves from the east combined with rainfall, as observed in the 2013 LiDAR data, with ~85 mm of accumulated rainfall in the preceding days, resulting in a configuration similar to Event II. Another case occurred on 14 March 2018 during a less intense storm with southeasterly wave conditions and ~55 mm of rainfall, when the stream shifted eastward, although it did not reach the easternmost extreme. These observations show that, in addition to precipitation, the stream’s position depends on wave direction and rainfall intensity.

In addition to natural processes, human intervention also influences the configuration of the stream outlet at Castell beach. During the summer season, when the beach is levelled for recreational purposes, the stream mouth is often artificially closed and redirected back toward the central sector of the beach. However, when the stream channel is not actively reshaped along with the beach, it tends to reactivate following its pre-existing, storm-influenced course, as observed in the months after Event II. Following the eastward outlet formation during this storm, subsequent stream activations, up until its artificial closure in May 2020, occurred along the same morphological trace. This inherited configuration was particularly evident during the 21 April 2020 storm (Supplementary Material, Figure S3), when cumulative rainfall was comparable to that recorded during Event II (Supplementary Material, Table S1). Such inherited morphology becomes especially relevant after extreme events, as the stream’s migration toward the more wave-sheltered end of the beach not only facilitates discharge during high-energy conditions but also promotes sediment deposition in the protected sector during subsequent reactivations, thereby contributing to the recovery of the subaerial beach.

5.2. Coastal Sediment Balance

Sediment dynamics in coastal areas vary depending on the relative dominance of wave action or fluvial discharge. In the absence of fluvial discharges, dry storms typically induce bottom sediment resuspension and offshore transport. When storms coincide with fluvial discharges (wet storms), the interaction between riverine inputs (derived from basin and channel erosion) and wave-induced resuspension can lead to the formation of ephemeral, poorly consolidated deposits on the shoreface [35]. In embayed beaches, most studies have focused on wave-driven processes, while stream-related inputs have received comparatively little attention and are usually limited to extreme flood events. In Elba Island, ref. [14] reported that an extreme flood of 300 mm in 4 h resulted in immediate accretion and shoreline progradation of 2 m.

At Castell, concomitant storm impacts and stream activation jointly influences the sediment balance. This is particularly evident during Event II (January 2020), when stream and wave forcing jointly affected both the subaerial and submerged sectors of the beach, producing an uneven distribution of morphological changes and altering sediment redistribution across the system. Eastward waves entered the bay obliquely from the southeast, generating an alongshore gradient in cross-shore sediment exchange proportional to wave exposure [7]. On the emerged beach, the exposed western sector underwent intense cross-shore exchange and shoreline retreat, whereas in the eastern sector, the change in the stream mouth location led to the formation of a new channel and a loss of sediment volume. In the submerged part, this resulted in an asymmetric deposit extending further offshore and reaching greater depths in the exposed western (~7.5 m) than in the sheltered eastern (~4.5 m).

On the other hand, stream sediment delivery was evidenced mainly by two features. Firstly by the plume observed beyond the bay on 23 January 2020 (Figure 3b), two days after the peak of Event II, which likely corresponds to offshore export of fine sediments supplied by the stream [34]. Secondly by the subaqueous delta that formed near the stream outlet, inferred from the seaward displacement of the 1–1.5 m depth contours observed after Event II (Figure 5a), resulted from the deposition of the sandy fraction supplied by the stream.

This suggests that part of the apparent sediment loss was partly offset by new sediment supplied by the stream during the storm. This is further supported by the positive balance between the sediment eroded from the subaerial beach () and the volume of the submerged deposit (). Similar to the findings of ref. [34], where up to 30% of a submerged delta volume originated from new sediment input and approximately 50% from reworking of the river mouth, the Castell case suggests a combined marine–fluvial contribution on the nearshore deposit, although quantification is not possible here. Beyond the shared sediment contribution, wave–stream interactions influenced nearshore sediment delivery patterns, as mentioned in the previous section, with waves driving the migration of the stream channel and positioning the stream delta in a wave-sheltered sector.

The formation of these deposits is relevant because they may influence the subsequent response of the beach to later events, affecting sediment redistribution and nearshore morphodynamics. For instance, ref. [36] observed contrasting responses to two moderate storms: the one following a flood event, which had generated a submerged deposit, led to the redistribution of fine sediment accumulated during the flood; whereas the one following a dry storm (with no fluvial inputs) caused seabed erosion. At Castell, the redistribution of the shallower portion of the submerged deposit in the nearshore zone (down to 4 m water depth) likely explains the rapid partial recovery of the beach observed six months after Event II. By July 2020, cross-shore transport and eastward longshore drift had progressively returned this sediment to the subaerial beach, driven by wave conditions within the embayment (AWAC wave rose, Figure 1e). The mild wave climate following the Event II, along with moderate winter storms (none exceeding Class II), facilitated a multiannual transfer of nearshore sediment toward the beachface, contributing to the full recovery of the subaerial beach to its pre-storm configuration by February 2022. In this way, the submerged deposit acted as a sediment buffer, supplying material to the beach and enhancing its resilience to subsequent events, consistent with findings from other studies [37].

Overall, these observations highlight the interlinked role of marine and fluvial processes in shaping the sediment budget of small embayed beaches. While wave action governs cross-shore and alongshore sediment redistribution, nearshore sediment dynamics vary with the modes of riverine sediment delivery. The combined analysis of an extreme storm (Event II) and the subsequent recovery at Castell provides valuable insight into beach resilience, offering a useful reference for coastal management under climate change. The morphological evolution of Castell beach demonstrates the autonomous capacity of these small natural systems to maintain and recover after storms, suggesting that the beach is in a good state of health according to [38]. This observation reinforces the notion that coastal management should prioritise the preservation of natural dynamics to enhance resilience and allow beaches to adapt to changing environmental forcings.

6. Conclusions

The geomorphological response and post-storm recovery of a natural embayed beach fed by a stream in the NW Mediterranean, Castell beach, were evaluated after extreme waves and rainfall events on 3 December 2019 (Event I) and 19 January 2020 (Event II). Event I had minor impact, whereas Event II led to significant morphological changes, although the beach had fully recovered to its pre-storm state by February 2022.

Results highlight that understanding stream–wave interactions is key for assessing sediment dynamics and morphological responses in highly protected embayed beaches. In addition to rainfall intensity, the position of the stream mouth is influenced by both the intensity and direction of incoming waves, generally shifting toward the more wave-sheltered sector. Variations in the position of the stream mouth therefore exert a direct influence on sediment delivery and, consequently, on beach recovery. During Event II, this shift in the outlet position triggered the formation of a new channel across the subaerial beach and the development of a nearshore sediment deposit in the sheltered sector of the bay. This deposit acts as a temporary sediment buffer, facilitating the progressive recovery of the beach following storm conditions. These findings confirm that small streams can act as major drivers of morphological variability across the entire subaerial beach.

Castell beach exemplifies a Good Health beach [38], minimally urbanised and capable of naturally recovering from exceptional extreme events. Sustained by sediment supplied by small streams, such coastal systems can dynamically adapt even to extreme conditions. These results emphasise that coastal management should prioritise renaturalisation to enhance resilience and allow beaches to adapt and recover autonomously.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/geosciences16010027/s1, Figure S1: Bedforms changes; Figure S2: Surveys domain; Table S1: Wave events between November 2019 and February 2022; Figure S3: Stream evolution during April 2020.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.-P., R.D., G.S. and J.G.; methodology, C.M.-P., R.D., G.S. and J.G.; validation, C.M.-P., R.D., G.S. and J.G.; formal analysis, C.M.-P., R.D., G.S. and J.G.; investigation, C.M.-P., R.D., G.S. and J.G.; data curation, C.M.-P., R.D., G.S. and J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.-P.; writing—review and editing, C.M.-P., R.D., G.S. and J.G.; visualization, C.M.-P.; supervision, R.D., G.S. and J.G.; project administration, G.S. and J.G.; funding acquisition, G.S. and J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been carried out in the framework of the MOLLY (PID2021-124272) and SOLDEMOR (TED2021-130321B-I00) research projects funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities and the Catalan Government Excellent Research Groups (2021-SGR-00433). It contributes to the Severo Ochoa Centre of Excellence programme through Grant CEX2024-001494-S funded by AEI 10.13039/501100011033. C. Marco-Peretó is supported by Spanish FPI grant (PRE2022-101492).

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study include LiDAR data provided by the Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya, and bathymetric data from the ESPACE Project dataset (2004). Data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors in the repository https://doi.org/10.20350/digitalCSIC/17833 (accessed on 20 December 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Angels Fernández-Mora for the acquisition and treatment of the bathymetric surveys, the Secretariat General of the Sea (SGP) of the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food and TRAGSA for the ESPACE Project dataset (2004), as well as the Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya for providing the LiDAR data. Scientific colour maps by [39] were used in Figure 1a and Figure 4a–g (Batlow colour map), and in Figure 4i–n and Figure 5a–b (Vik colour map). PlanetScope imagery © 2023 Planet Labs PBC [40] was used in Figure S3 of the Supplementary Material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gallop, S.L.; Kennedy, D.M.; Loureiro, C.; Naylor, L.A.; Muñoz-Pérez, J.J.; Jackson, D.W.T.; Fellowes, T.E. Geologically controlled sandy beaches: Their geomorphology, morphodynamics and classification. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 731, 139123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pranzini, E.; Rosas, V.; Jackson, N.L.; Nordstrom, K.F. Beach changes from sediment delivered by streams to pocket beaches during a major flood. Geomorphology 2013, 199, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, R.C.; Woodroffe, C.D. Coastal compartments: The role of sediment supply and morphodynamics in a beach management context. J. Coast. Conserv. 2023, 27, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, L.; Pranzini, E.; Rosas, V.; L., W. Landuse changes and erosion of pocket beaches in Elba Island (Tuscany, Italy). J. Coast. Res. 2011, 1774–1778. [Google Scholar]

- Marco-Peretó, C.; Durán, R.; Toomey, T.; Guillén, J. Controls on the morphological evolution of embayed beaches: Morphometry versus external forcing. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2024, 49, 1289–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, R.; McLoughlin, R.; Short, A.; Symonds, G. The Southern Oscillation Index, wave climate, and beach rotation. Mar. Geol. 2004, 204, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, M.D.; Turner, I.L.; Short, A.D. New insights into embayed beach rotation: The importance of wave exposure and cross-shore processes. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2015, 120, 1470–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, C.; Ferreira, Ó. 24—Mechanisms and timescales of beach rotation. In Sandy Beach Morphodynamics; Jackson, D.W.T., Short, A.D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 593–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usai, A.; Simeone, S.; Trogu, D.; Porta, M.; De Muro, S. A morphometric analysis of embayed beaches: Southern Sardinia Island. Geomorphology 2025, 483, 109838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, M.D.; Turner, I.L.; Kinsela, M.A.; Middleton, J.H.; Mumford, P.J.; Splinter, K.D.; Phillips, M.S.; Simmons, J.A.; Hanslow, D.J.; Short, A.D. Extreme coastal erosion enhanced by anomalous extratropical storm wave direction. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, D.; Rosas, V.; Pranzini, E. Pocket beaches of Elba Island (Italy)—Planview geometry, depth of closure and sediment dispersal. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2014, 138, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, P.L.; Warrick, J.A. Dramatic beach and nearshore morphological changes due to extreme flooding at a wave-dominated river mouth. Mar. Geol. 2010, 271, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.A.G. The role of extreme floods in estuary-coastal behaviour: Contrasts between river- and tide-dominated microtidal estuaries. Sediment. Geol. 2002, 150, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranzini, E.; Rosas, V. Pocket beach response to high magnitude–low frequency floods (Elba Island, Italy). J. Coast. Res. 2007, 50, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basterretxea, G.; Orfila, A.; Jordi, A.; Casas, B.; Lynett, P.; Liu, P.L.F.; Duarte, C.M.; Tintoré, J. Seasonal Dynamics of a Microtidal Pocket Beach with Posidonia oceanica Seabeds (Mallorca, Spain). J. Coast. Res. 2004, 20, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, R.; Guillén, J.; Ruiz, A.; Jiménez, J.A.; Sagristà, E. Morphological changes, beach inundation and overwash caused by an extreme storm on a low-lying embayed beach bounded by a dune system (NW Mediterranean). Geomorphology 2016, 274, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeone, S.; Palombo, L.; Molinaroli, E.; Brambilla, W.; Conforti, A.; De Falco, G. Shoreline Response to Wave Forcing and Sea Level Rise along a Geomorphological Complex Coastline (Western Sardinia, Mediterranean Sea). Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelle, B.; Marieu, V.; Bujan, S.; Splinter, K.D.; Robinet, A.; Sénéchal, N.; Ferreira, S. Impact of the winter 2013–2014 series of severe Western Europe storms on a double-barred sandy coast: Beach and dune erosion and megacusp embayments. Geomorphology 2015, 238, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintó, J.; Garcia-Lozano, C.; Roig-Munar, F.X. Itinerario Geomorfológico y Paisajístico por la Costa Brava: Bahía de Pals y Playa de Castell (Palamós); CSIC—Instituto de Ciencias del Mar (ICM): Barcelona, Sapin, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Generalitat de Catalunya. Decret 23/2003, de 21 de gener, pel qual s’inclou l’espai Castell-Cap Roig en el Pla d’espais d’interès natural, aprovat pel Decret 328/1992, de 14 de desembre, i es modifiquen els límits de l’espai Muntanyes de Begur. D. Of. General. Catalunya 2003, 3810, 1637–1638. Available online: https://portaljuridic.gencat.cat/eli/es-ct/d/2003/01/21/23 (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Bolaños, R.; Jorda, G.; Cateura, J.; Lopez, J.; Puigdefabregas, J.; Gomez, J.; Espino, M. The XIOM: 20 years of a regional coastal observatory in the Spanish Catalan coast. J. Mar. Syst. 2009, 77, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, E.T.; Jimenez, J.A.; Mateo, J. A coastal storms intensity scale for the Catalan sea (NW Mediterranean). Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 11, 2453–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrion-Bertran, N.; Falqués, A.; Ribas, F.; Calvete, D.; de Swart, R.; Durán, R.; Marco-Peretó, C.; Marcos, M.; Amores, A.; Toomey, T.; et al. Role of the forcing sources in morphodynamic modelling of an embayed beach. Earth Surf. Dyn. 2024, 12, 819–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J.A.; Sancho-García, A.; Bosom, E.; Valdemoro, H.I.; Guillén, J. Storm-induced damages along the Catalan coast (NW Mediterranean) during the period 1958–2008. Geomorphology 2012, 143–144, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amores, A.; Marcos, M.; Carrió, D.S.; Gómez-Pujol, L. Coastal impacts of Storm Gloria (January 2020) over the north-western Mediterranean. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 20, 1955–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho-García, A.; Guillén, J.; Gracia, V.; Rodríguez-Gómez, A.C.; Rubio-Nicolás, B. The Use of News Information Published in Newspapers to Estimate the Impact of Coastal Storms at a Regional Scale. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdalet, E.; Marrasé, C.; Pelegrí, J.L. Resumen sobre la Formación y Consecuencias de la Borrasca Gloria (19–24 Enero 2020); CSIC—Instituto de Ciencias del Mar (ICM): Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Alfonso, M.; Lin-Ye, J.; García-Valdecasas, J.M.; Pérez-Rubio, S.; Luna, M.Y.; Santos-Muñoz, D.; Ruiz, M.I.; Pérez-Gómez, B.; Álvarez Fanjul, E. Storm Gloria: Sea State Evolution Based on in situ Measurements and Modeled Data and Its Impact on Extreme Values. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 646873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, E.T.; Jiménez, J.A. Regional vulnerability analysis of Catalan beaches to storms. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Eng. 2009, 162, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, R.; Davis, R.E. An Intensity Scale for Atlantic Coast Northeast Storms. J. Coast. Res. 1992, 8, 840–853. [Google Scholar]

- Stockdon, H.F.; Sallenger, A.H.; Holman, R.A.; Howd, P.A. A simple model for the spatially-variable coastal response to hurricanes. Mar. Geol. 2007, 238, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdon, H.F.; Holman, R.A.; Howd, P.A.; Sallenger, A.H. Empirical parameterization of setup, swash, and runup. Coast. Eng. 2006, 53, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viñes, M.; Sánchez-Arcilla, A.; Epelde, I.; Mösso, C.; Franco, J.; Sospedra, J.; Abalia, A.; Líria, P.; Grifoll, M.; Ojanguren, A.; et al. Morphodynamic predictions based on Machine Learning. Performance and limits for pocket beaches near the Bilbao port. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1600473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meslard, F.; Balouin, Y.; Robin, N.; Bourrin, F. Assessing the Role of Extreme Mediterranean Events on Coastal River Outlet Dynamics. Water 2022, 14, 2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zăinescu, F.; Vespremeanu-Stroe, A.; Anthony, E.; Tătui, F.; Preoteasa, L.; Mateescu, R. Flood deposition and storm removal of sediments in front of a deltaic wave-influenced river mouth. Mar. Geol. 2019, 417, 106015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén, J.; Bourrin, F.; Palanques, A.; Durrieu de Madron, X.; Puig, P.; Buscail, R. Sediment dynamics during wet and dry storm events on the Têt inner shelf (SW Gulf of Lions). Mar. Geol. 2006, 234, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T.; Masselink, G.; O’Hare, T.; Saulter, A.; Poate, T.; Russell, P.; Davidson, M.; Conley, D. The extreme 2013/2014 winter storms: Beach recovery along the southwest coast of England. Mar. Geol. 2016, 382, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.a.G.; Jackson, D.W.T. Coasts in Peril? A Shoreline Health Perspective. Front. Earth Sci. 2019, 7, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crameri, F. Scientific colour maps. Zenodo 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planet Labs PBC. PlanetScope Imagery © 2023. Available online: https://www.planet.com/ (accessed on 18 June 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.