1. Introduction

The purpose of educational practices is to deliver comprehensive knowledge in students’ chosen areas, fostering readiness for professional responsibilities, civic engagement, and life beyond the classroom. These methods focus on promoting critical thinking, research skills, and the ability to apply theoretical concepts to real-world scenarios, thus creating a dynamic and engaging learning environment, fostering intellectual growth, and preparing students for professional success. Nevertheless, certain subjects face challenges in engaging students, as the instructional methods employed have largely remained unchanged over the past two decades [

1,

2,

3].

One particular field of interest is Geoscience education, involving a combination of various methods for lecture-based learning. Geology courses often begin with foundational lectures that cover theoretical concepts, principles, and the Earth’s history. Typically, teachers use slides, presentations, and other materials to convey information to students. Additionally, laboratory sessions, where students can develop practical skills in mineral and rock identification, geological mapping, and other hands-on activities, including collecting data and analyzing the geological phenomena. These sessions reinforce concepts learned in theoretical lectures and provide valuable field preparation. Another method is field trips, which are an essential part of geology education. By visiting geological sites, students can observe and analyze different lithological units, structures, and mineralogical associations [

4,

5]. Field trips offer a unique learning experience, but they can be logistically challenging and may require significant funding, which most schools and institutes may struggle to accomplish. These led to a decrease in the number of field trips conducted around the world, which can lead to a reduction in the skills acquired by the students [

6,

7].

To address most theoretical lectures and laboratory sessions, current approaches rely on traditional means like textbooks, paper maps, and others, which offer limited insight into the spatial extent of the geological processes involved (like the one described in

Figure 1), lacking the capacity to generate 3D spatial awareness. To elaborate, geological sites, with their intricate formations and unique characteristics, present a level of complexity that surpasses the limitations of traditional modes of representation such as images, text, or paper maps. These sites are geological wonders shaped over vast periods, exhibiting distinct features and intricate patterns that are challenging to convey adequately through static visual mediums (see

Figure 1). The three-dimensional nature of geological formations, such as the intricate layering of sedimentary rocks or the dynamic folds in mountain ranges, demands a more immersive approach to comprehension [

5,

6]. Attempting to articulate the essence of geological sites solely through images can fall short in capturing the true depth and intricacy of these natural wonders. While a photograph may convey a snapshot of a specific geological feature, it often lacks the ability to communicate the spatial relationships, scale, and geological processes that have shaped the site over geological time scales. Likewise, textual descriptions may struggle to convey the sheer complexity of geological formations, leading to potential misunderstandings or oversimplifications. Paper maps, though valuable for spatial orientation, may not fully encapsulate the dynamic and evolving nature of geological landscapes [

7,

8].

One technology that gained popularity in recent years for education is Virtual Reality (VR) [

9], allowing to immerse users in an interactive three-dimensional digital environment [

10,

11,

12,

13]. This growing interest is caused by its immersive features, the advances of the enabling software/hardware, and the lowering of costs, among others [

1,

14,

15]. Using VR allows students to be immersed in distinct 3D environments with a level of realism that could never be attained through the use of traditional methods. It changes the paradigm, switching from a flat text-based one-dimensional interface to a rich, immersive 3D environment, capable of being used for educational purposes at all educational levels and in all disciplines from sciences to humanities [

6,

16,

17].

Despite this, Geoscience education supported by VR has been the target of very reduced work [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Thus far, VR studies have explored virtual worlds where students/teachers are represented through avatars, being able to learn about Geoscience concepts while exposed to images and virtual models using VR headsets [

3]. Regardless, interaction with the environment was limited to answering surveys, lacking manipulation features, which seem paramount to fully grasp the geological phenomena. Following this, ref. [

5] has explored the use of 360º images, captured at strategic geological sites, merged into a single path for students to jump through various points of interest. This ran in a smartphone integrated into a VR headset. Due to this, the size of the content displayed influenced the smartphone performance, and in turn, the overall experience. As before, limited interaction features existed. Similarly, ref. [

4] used 360º images were also used to re-create field trips, this time, combined with audio guidance and a 3D model of an outcrop for measuring stratigraphy with the assistance of a humanoid robot. This created a lack of human element, which could be introduced by a teacher, but, instead, an automatic process was used, being an individual experience only for students. It also missed navigation for inspecting virtual objects. Plus, filling in a detailed stratigraphic column (i.e., including information about bed thickness, sedimentary structures, and color) was conducted afterward and not in the VR environment.

Building on these ideas, other works have explored similar approaches, using 360 videos, animations, and knowledge interactive quizzes, providing interaction possibilities, but maintaining an isolated experience approach, not having the presence of a teacher in real-time [

23,

24]. Expanding the focus to immersive tools, [

25] developed an interactive VR tool for visualizing geological folds, allowing students to explore key features such as wavelength, amplitude, and fold orientation. The system is low-cost and supports active learning of complex 3D structures. Usability testing with 11 participants showed promising results, highlighting the tool’s potential to improve understanding of fold geometry while suggesting areas for future enhancement. In a related study, [

26] developed a VR module to introduce undergraduate students to geological structures, from micro- to macro-scales. A small study (N = 10) included both VR and non-VR participants during an 11-day field mapping trip. Students reported positive experiences and perceived learning transfer, but observations indicated that guidance from instructors was needed to fully apply the VR learning in the field. The study highlights the potential of immersive tools for 3D-thinking skills while emphasizing the importance of repetition and structured support within VR. More recently, [

27] presented a system combining 360° video, photogrammetry, and virtual content to teach practical geology field skills. Evaluation with first- and second-year students showed that only those with prior experience benefited, suggesting the tool is more effective for revision than first-time learning. The study highlights both the potential of virtual training for skill transfer and the challenges of implementing such systems in university settings.

These works illustrate that although meaningful progress has been made by the research community, several important opportunities remain. For example, there is still a lack of interaction, manipulation, and authoring features that both students and teachers can use to explore digital content and express themselves, for instance, by posing questions, marking regions of interest, or adding interpretable annotations (including features that support reusing such content in subsequent lectures if needed). Furthermore, most existing solutions rely on individual use of VR headsets (a costly approach that not all universities can support) and primarily employ standard or 360° images or videos, which inherently lack the spatial richness required to fully convey complex geological processes. Equally relevant, many systems do not provide collaborative or social features that support teachers and students engagement in shared spaces. Instead, they typically employ symmetric setups in which all participants use similar immersive devices, limiting the exploration of alternative instructional configurations such as asymmetric, teacher-led approaches, where students may observe, reflect, and engage collectively while benefiting from the teacher’s expert guidance within the immersive environment. In this vein, the following research question was established to help guide our research: ‘RQ—Can 3D reconstruction, VR, and a Large Display be used to assist teachers with the educational process of specific geological phenomenons?’.

We propose combining 3D reconstruction, with VR, and large-display technology to improve Geoscience education for university students, applying a Human-Centered Design (HCD) methodology with input from domain experts. The scenario explored adopts a teacher-centric model, in which the instructor interacts with virtual replicas in an immersive VR environment, while students follow the experience on a large display. To the best of our knowledge, this is among the first studies to investigate an asymmetric immersive collaborative teaching model within a classroom context. In this approach, virtual replicas, captured using mobile devices or other acquisition hardware, can be integrated into the framework, enabling students to access geological sites that would otherwise be unreachable. During class, students observe the teacher’s actions in real time, gaining insight into how the immersive environment’s 3D nature supports explanations, object manipulation, spatial inspection, and annotation, thereby enriching the instructional process. To evaluate how the target audience would respond to this model, and to assess usability and key dimensions of social interaction, a user study with 20 participants was conducted comparing this approach to a traditional method. This paper reports and critically discusses the results obtained through statistical analysis, and concludes by outlining future research opportunities informed by these findings.

2. Using an Asymmetric Immersive Collaborative Setting

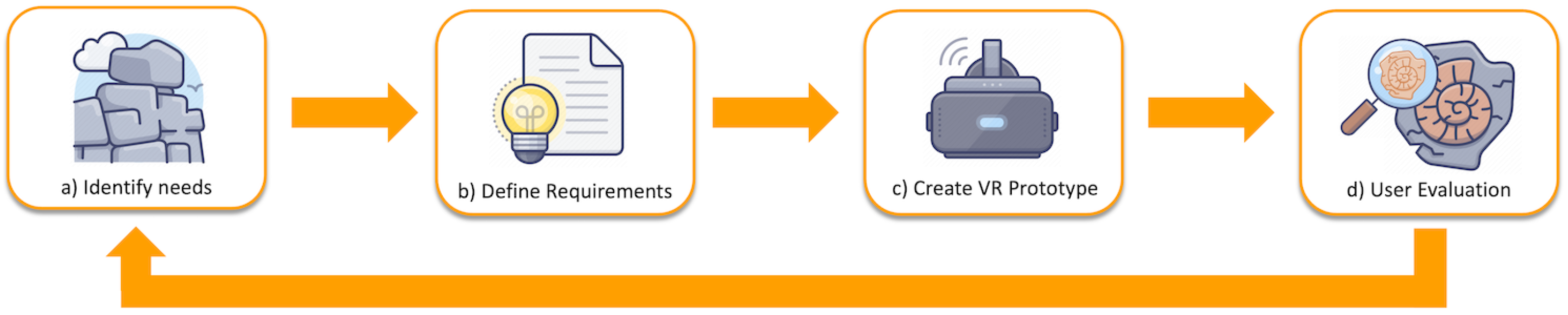

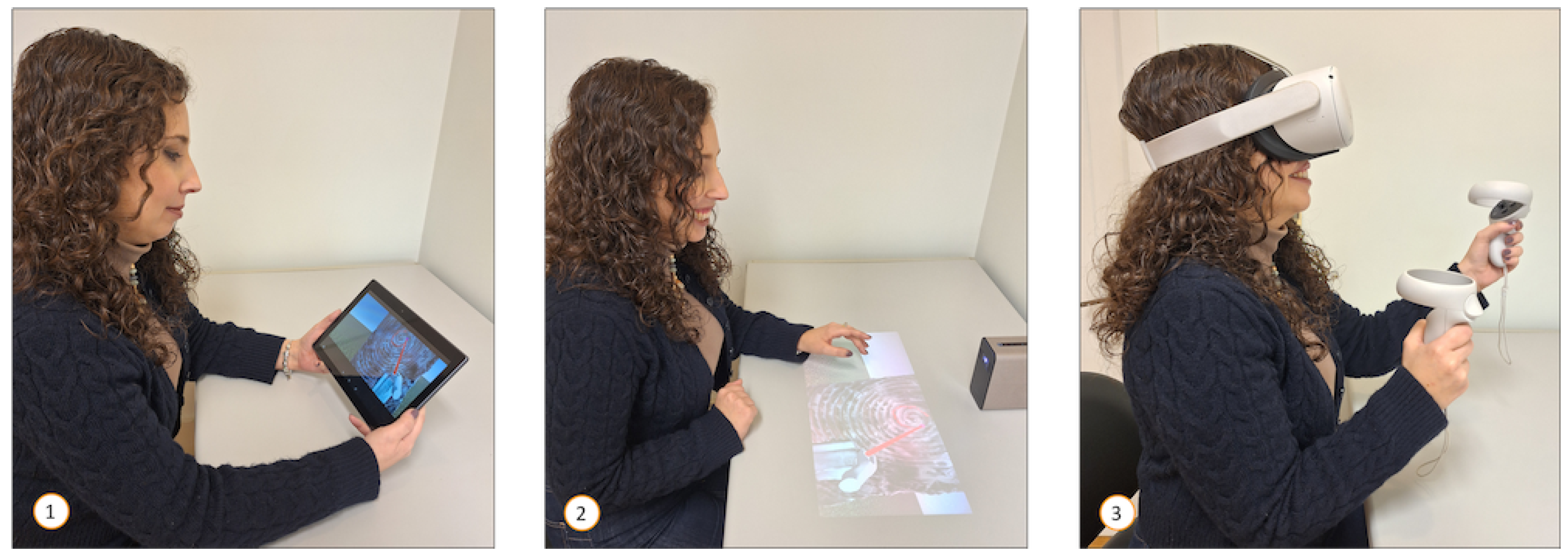

A HCD approach was employed with university students and teachers in Geoscience to identify their needs and limitations (as illustrated in

Figure 2). Overall, 13 individuals participated in this process, including 1 teacher, 1 researcher, 2 PhD, and 3 MSc students from the Geoscience field. Also, 2 teachers, 1 researcher, and 2 MSc. students from computer science engineering, having experience in Human-Centered Computing (HCC), and immersive solutions, in addition to a strong track record in conducting user studies in varied application contexts [

28,

29].

After conducting various meetings with the target users, a set of requirements was defined, allowing to guide the design of a framework for Geoscience education. To elaborate, given the current financial constraints faced by universities, having a low-cost solution was defined as paramount for increasing the adoption of a novel method. Providing each student with an VR HMD, while valuable for full immersion, is financially unfeasible. Plus, although a non-immersive solution for the teacher would certainly be feasible, it would limit depth perception, reduce the fidelity of spatial understanding, and diminish the naturalness of interacting with 3D content, which were key requirements identified by the target audience during our design process.

Moreover, they also emphasized the need to support multiple 3D models from remote geological processes as a key aspect, to avoid being limited to default models, providing the possibility to add their own models as desired. Also, have the capacity to select, manipulate, and even navigate through distinct points of interest in these models. Equally important, integrate authoring features, allowing placement of additional information in the respective models. It was also manifested the need for students and teachers to visualize the same virtual content. In this vein, next, a first effort towards assisting students and teachers with Geoscience education is proposed, adopting a teacher-centric model.

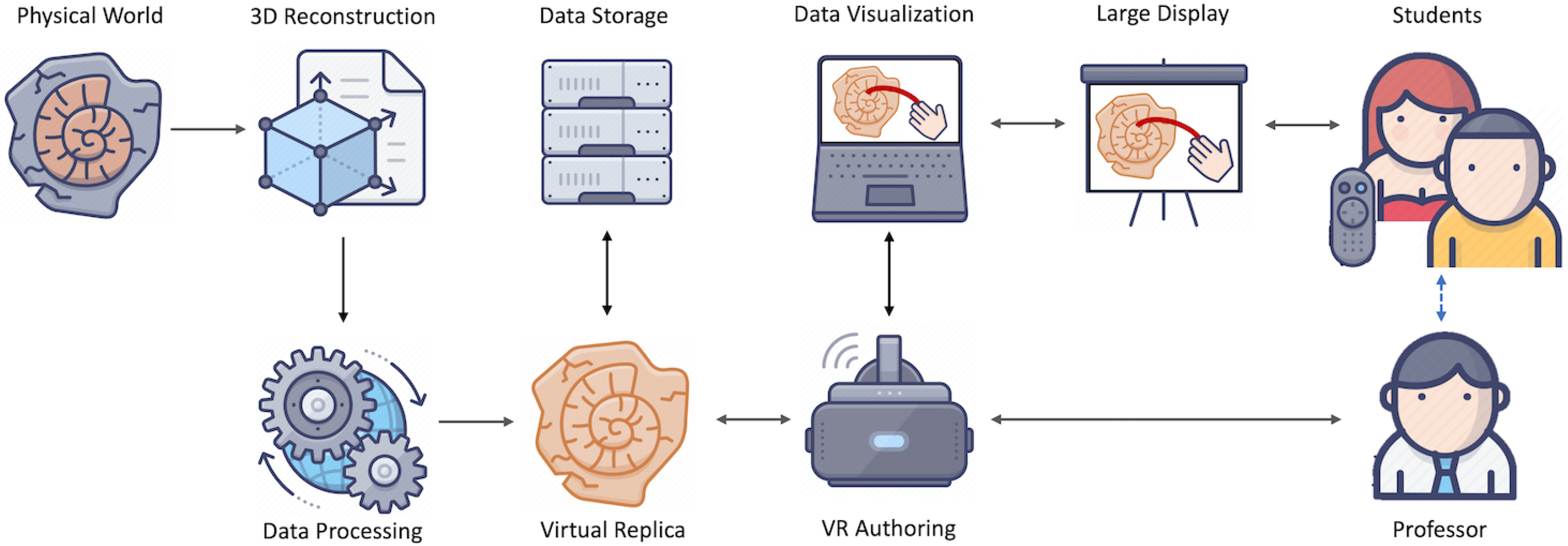

Figure 3 displays an overview of the main modules of the proposed solution, designed with the previous requirements in mind.

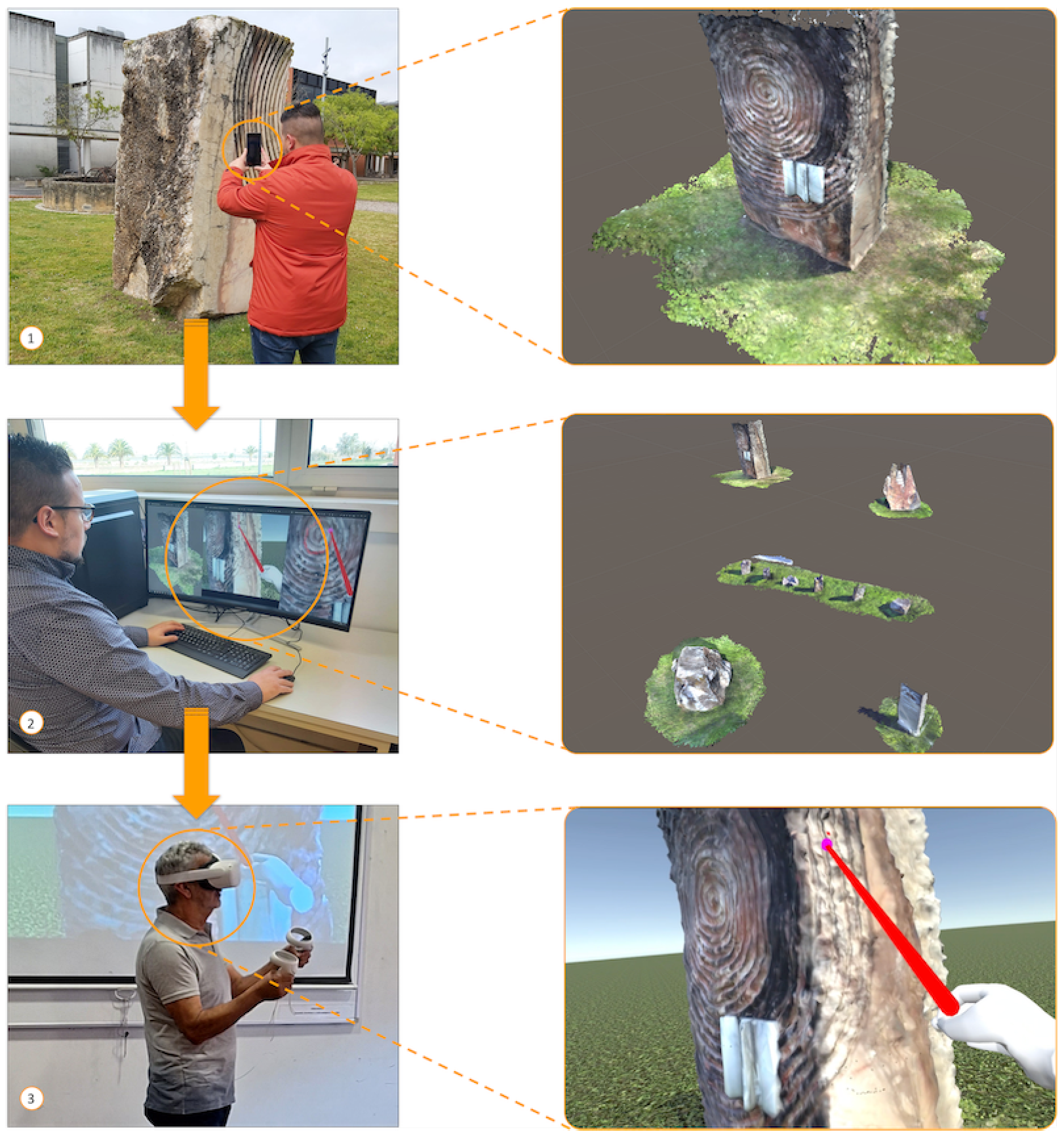

First, a Handheld Device (HHD) can be used to perform in-situ 3D reconstruction of selected geological processes based on depth sensors, cameras, and other spatial mapping technologies. During this data collection, a comprehensive survey of the target structure is obtained, capturing detailed images and spatial information from different angles. This initial step enables users to record the characteristics of the region of interest, requiring multiple captures to iteratively create the final model, with a higher level of detail and quality, as shown in

Figure 4. The data captured can be processed using advanced algorithms to create a 3D reconstruction of the physical space, i.e., a virtual replica with optimized parameters like texture, and others. Although an HHD is considered for this proposal, other sensors may also be applied to generate 3D reconstructions (e.g., Leica BLK 360 [

30]). The selection of this device was to maintain the overall cost as low as possible, as well as having a high level of portability, allowing the creation of new 3D reconstructions anywhere. Another possibility is to analyze available databases for existing 3D models that incorporate all the necessary characteristics from a Geoscience point of view.

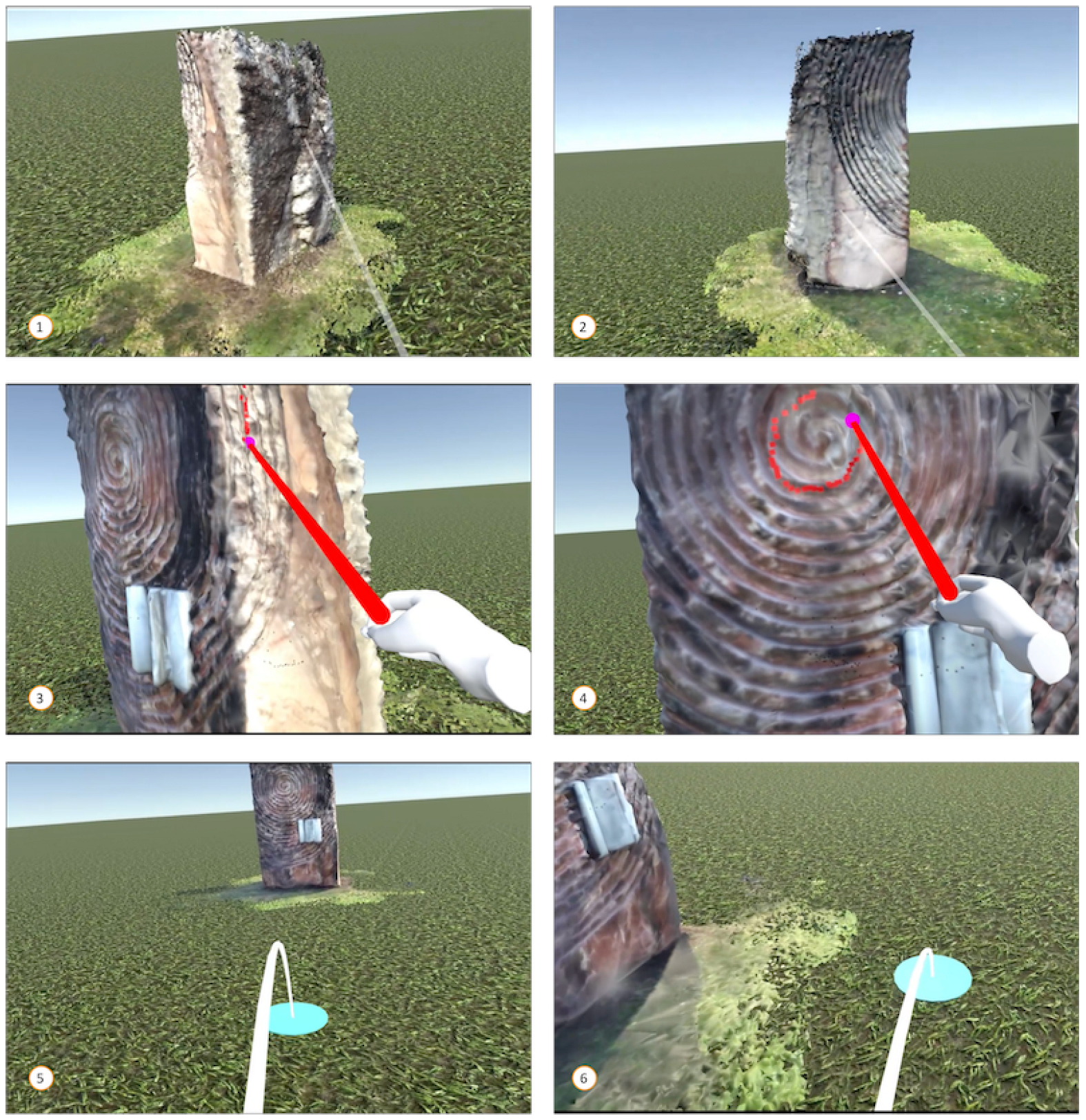

Following this step, the virtual replicas can be exported using a standard game engine, such as Unity, and integrated into a pre-configured virtual environment. All modifications are automatically saved on a dedicated server, ensuring data persistence. Once all replicas are positioned in their intended locations, the complete environment can be deployed to a VR headset. Within the VR experience, users can explore geologically significant sites, analyze complex 3D structures, and simulate geological processes (

Figure 5). Interaction is facilitated through selection, navigation, and authoring tools, as depicted in

Figure 6, allowing participants to manipulate virtual replicas, adjusting their placement to create customized learning scenarios. They can also point to a location and teleport directly to it, enabling efficient navigation and close examination of multiple structures. This interactivity enhances users’ understanding of spatial relationships and promotes a deeper comprehension of Geoscience processes.

Additionally, through a set of authoring processes, users can create drawings, highlighting important areas of interest (e.g., such as cracks or particular structural details) or place notes with additional information, among other possibilities. These annotations can be stored and reused in later lectures if needed, enabling the persistence and continuity of instructional content across multiple teaching sessions. This not only reduces preparation time for instructors but also allows them to progressively refine and enrich their explanations by building on previously created materials. Moreover, the ability to preserve and revisit annotations supports more coherent learning pathways for students, who can see how concepts evolve over time or across different geological contexts. Such persistence of authored content follows a principle previously explored in remote industrial settings, where saved annotations enhance communication, facilitate troubleshooting, and support long-term knowledge transfer. This hands-on approach promotes engaging and impactful learning experiences, especially for students.

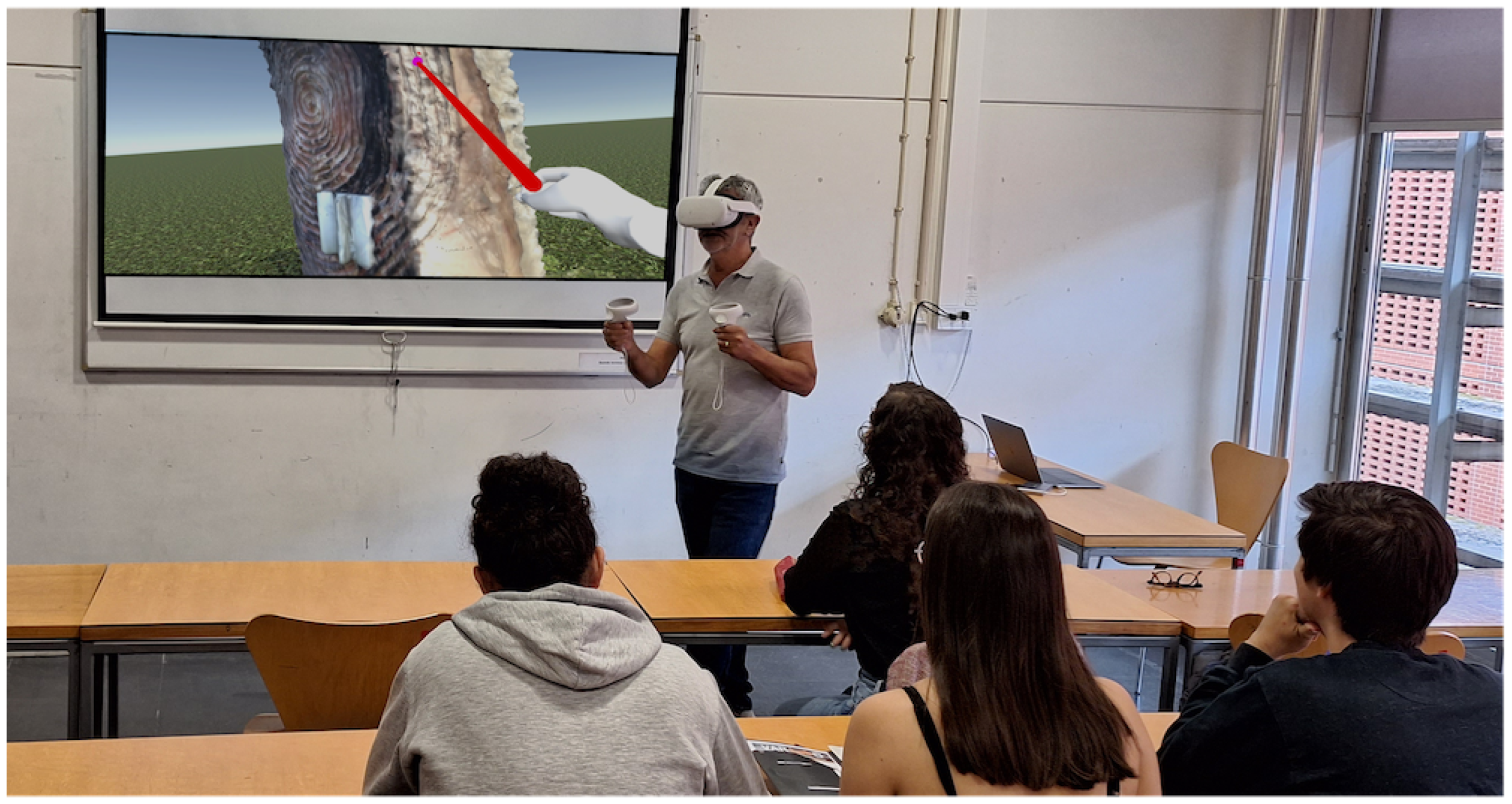

The last step of the framework includes casting the VR experience directly to a smart projector (if available), or to a computer, which in turn must be connected to a standard projector (Large Display). This way, a teacher can educate by demonstration, interacting with the virtual environment, while students observe the session on a large display, following the instructor’s actions, listening to explanations, and acquiring insights into Geoscience concepts. Students can also pose questions, participate in discussions, and receive immediate feedback, thereby supporting comprehension and knowledge retention. Students may also ask questions, engage in discussions, and receive immediate feedback from the teacher, enhancing their understanding and retention of the subject matter. Furthermore, the Large Display facilitates group learning, enabling the entire class to benefit from the teacher’s expertise and fostering collaboration among students. Notwithstanding, a student can also take the teacher’s role in conducting exercises. This way, all students can learn from each other’s experiences. Overall, this educational scenario offers students a unique opportunity to learn from the teacher’s firsthand experiences and foster a more immersive and collaborative learning environment.

The 3D models were created using the Constructor Developer Tool, an Android application, while the proposed virtual environment was developed in the Unity engine with C# scripts. The Meta Quest SDK was subsequently employed to build and deploy the environment to the headset. Casting to the Large Display occurred using the Meta Quest native support for such a purpose. Also relevant, in time, we intend to expand the aforementioned pipeline to enable teachers and students to utilize it and create their own learning experiences, which was not the focus of the current study. While our primary aim was to establish a proof of concept, we recognize the significance of broadening authorship capabilities and aim to develop a platform that facilitates the integration of 3D models. This platform will also include authoring features to enable the creation of educational activities.

4. Results and Discussion

Next, the results from the user study are described and discussed. These were obtained through a data analysis using SPSS and Statistica S/W. Exploratory, descriptive, and inferential (non-parametric tests due to the ordinal data of the assessed dimensions) statistical techniques were used.

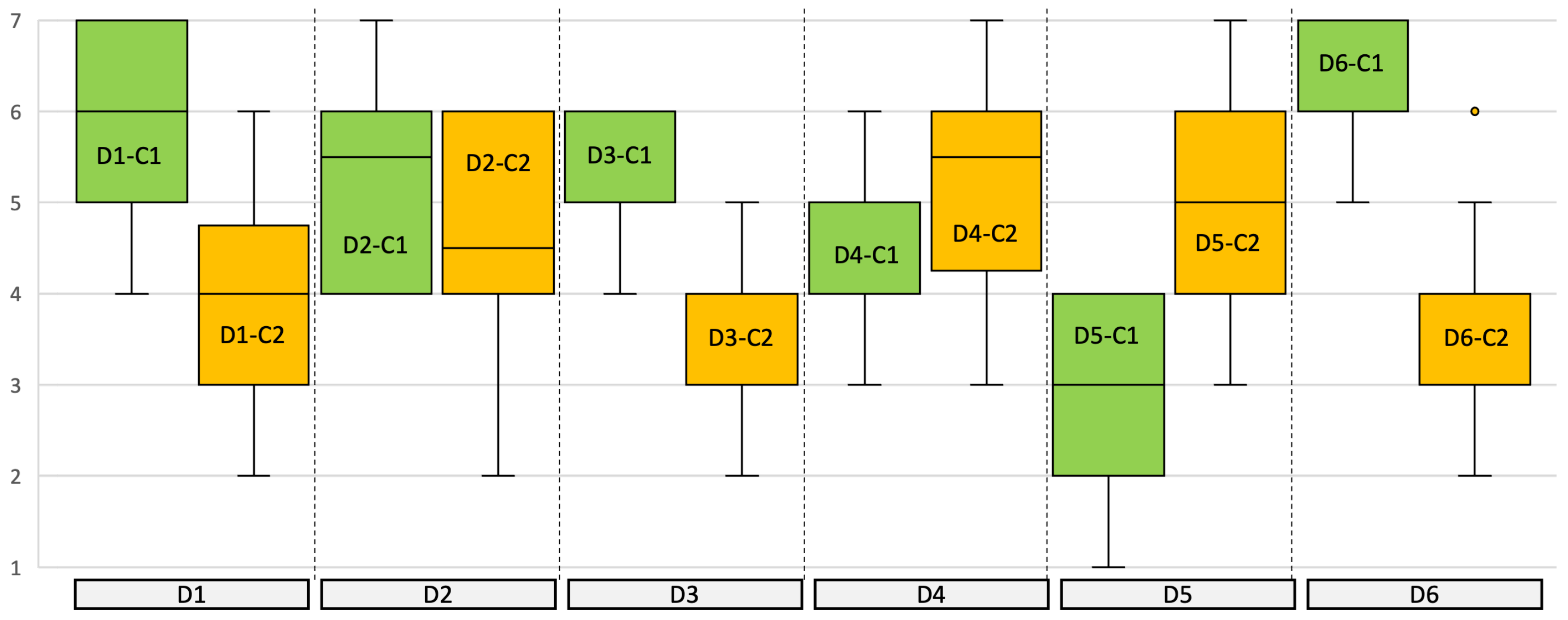

Figure 7 displays an overview of participants’ evaluation of the dimensions of collaboration considered, while using both conditions, rated using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1-Low to 7-High). Furthermore,

Table 1 summarizes the main results of the data analysis. It shows that there were significant differences between the two conditions in all dimensions except D2—Effectiveness in perceived information understanding and D4—Level of social presence. Considering the dimensions of the two dependent samples (matched conditions or within-subject design), the nonparametric Wilcoxon test was used to compare the equality of medians.

4.1. Overall Experience with Both Conditions

The findings related to the level of attentional allocation (D1) underscore a distinct advantage for C1, the VR solution, over C2, which involves static images/videos. Wilcoxon test showed a significant difference between conditions, with attentional allocation decreasing from C1 (median = 6) to C2 (median = 4) (Z = −3.61, p < 0.001). This disparity in attention allocation suggests that the nature of the VR solution effectively captivated participants’ attention during the learning experience. In C1, three-dimensional and dynamic elements of the virtual environment likely contributed to the observed higher level of attention. The ability to navigate, manipulate objects, and engage with the content in a more interactive manner may have resulted in a more engaging and captivating learning experience, as emphasized by one participant, stating that “the 3D models enable me to have a better understanding of the geological site, particular since the teacher could grab the model, scale and rotate it, allowing to focus on specific regions of interest”. In contrast, static images/videos in C2 may have struggled to elicit the same level of sustained attention, given their limited capacity for user interaction and engagement.

The evaluation of effectiveness in perceived information understanding (D2) shows a similar result for both conditions. A Wilcoxon test did not show a significant difference between conditions C1 (median = 5.5) and C2 (median = 4.5) (Z = −1.75, p = 0.080). Despite this, approximately half of the participants (11 out of 20) reported that C1 captured their attention more effortlessly than condition C2, e.g., “I felt like the static images and videos were helpful, but they didn’t fully capture the spatial aspects of the content as the alternative did”. It seems that the dynamic nature of the virtual replicas, coupled with the ability to be manipulated in real-time, significantly contributed to the enhanced appeal of C1, at least, regarding participant feedback. Moreover, participants highlighted the role of in-situ content creation in C1, emphasizing its impact on understanding major areas of interest, allowing participants to grasp complex concepts with greater ease. Participants’ suggestions for additional features, for example, using a controller to point to specific content or to add annotations, reflect a keen awareness of the potential for further enhancing communication and expression within the VR environment. The desire for tools that facilitate expression not only on the part of the students but also for the teacher, who can view this content while wearing the VR headset, underscores the collaborative potential of VR in educational settings.

The assessment of effectiveness in communicating about the task (D3) highlights an advantage for the VR solution in contrast to the static images and videos alternative. A Wilcoxon test showed a significant difference between conditions, with scores decreasing from C1 (median = 5) to C2 (median = 4) (Z = −3.81, p < 0.001). This distinct ratings is further elucidated by participant feedback, where 8 out of 20 individuals expressed challenges in communication when using C2, e.g., “despite the teacher’s effort, images and videos cannot be adapted to what he is trying to explain. So, he needed to keep pointing and zooming, as well as pause/play the videos in selected moments, aiming to explain concepts more easily”. This limitation stands in contrast to the flexibility provided by C1, where the teacher could manipulate elements, such as scaling up and down or changing perspectives. These interactive features offered greater freedom to enhance their explanations and complement their thoughts, contributing to a more effective communication process.

The examination of the level of social presence (D4) reveals an intriguing dynamic between conditions, with C2 rated slightly higher (median = 5.5) than the VR solution in C1 (median = 5). However, a Wilcoxon test indicated no significant difference between conditions (Z = 0.671, p = 0.502). Despite this lack of significant differences, a noteworthy factor is the fact that the teacher in C1 uses a VR headset. While this device creates an immersive experience for the teacher, it seemingly hampers the teacher’s ability to view and establish empathy toward the students, which is important to reflect upon. The use of the VR headset limits the teacher’s capacity to receive non-verbal cues from students, such as facial expressions, body language, and gestures, which play a crucial role in communication and interpersonal interaction, enabling teachers to gauge students’ comprehension, engagement, and emotional state, as well as make adjustments to the educational process on demand. This limitation, imposed by the VR headset, might have influenced participants to perceive a slightly lower social presence in C1 compared to the alternative condition with static images and videos. However, the acknowledgment of this constraint is balanced by the recognition that, despite the imposed limitation, the overall results for C1 were very positive. This suggests that the benefits and positive aspects of the VR solution, such as its immersive and interactive features, outweighed the potential drawbacks related to social presence, which is corroborated by the statistical analysis, showing no differences among conditions. This was also mentioned by some participants, expressing that “although I was able to understand better the concepts transmitted by the teacher using VR, I missed having his face visible to receive visual cues”, and “At first, I needed to adapt to the lack of direct communication, but then I was able to adjust. In time, I believe the quality of the explanations overshadows the absence of teacher representation”. During interviews, participant feedback further illuminates the potential for improvement. Seven out of 20 participants raised concerns and questioned whether using a distinct headset could address the social presence issue in C1. Two participants, familiar with digital realities, specifically recommended exploring the HoloLens 2 as a potential alternative. This suggestion opens up an interesting avenue for future assessment and development. Evaluating the feasibility and benefits of employing a different headset, such as the HoloLens 2, could address social presence concerns in C1 without compromising the positive aspects of the VR experience. Factors such as device cost, compatibility with educational requirements, and overall classroom feasibility will play a crucial role in determining the practicality of this alternative.

The evaluation of the level of mental effort (D5) reveals an interesting contrast, with participants rating C2—static images and videos higher than C1—the VR solution (it should be noted that for this D5 dimension, the ‘preferred’ mark should be 1—Low). A Wilcoxon test showed a significant difference between conditions, with scores increasing from C1 (median = 3) to C2 (median = 5) (Z = 3.59, p < 0.001). This discrepancy in mental effort ratings may be attributed to the perception that C2 limits students’ capacity to understand content in a 3D perspective. Although the VR solution may introduce an additional layer of complexity, requiring students to adapt to a 3D perspective, the authoring features in C1 allow the teacher to create in-situ information on the spot, a factor that can enhance the learning process by providing real-time, contextualized information. Additionally, the ability to export this content offers students the opportunity to revisit and engage with the material on their personal computers, providing flexibility and reinforcement of learning. This was highlighted by one participant, stating that “the VR solution helped me better comprehend what the teacher was trying to explain. On the other hand, the alternative made it harder to have a 3D understanding of the geological phenomena. I need to make a greater effort”. Emphasizing the complementary nature of C1 to the traditional approach in C2 is paramount. Rather than positioning C1 as a replacement, it should be regarded as a supplementary tool, strategically employed for specific subjects where its unique features can be maximized to improve the overall learning process. Acknowledging the dual role of these conditions allows for a more nuanced understanding of their respective strengths and underscores the importance of tailoring educational tools to suit the distinct requirements of various subjects and learning objectives.

The analysis of the level of satisfaction (D6) further solidifies the favorable outcomes associated with C1 compared to C2. A Wilcoxon test showed a significant difference between conditions, with scores decreasing from C1 (median = 6) to C2 (median = 4) (Z = −3.866, p < 0.001). These ratings align with the trends observed across the previously discussed dimensions, reinforcing the positive impact of the VR solution on participants’ overall learning experience. By equipping teachers with authoring features that enable the creation of personalized content, C1 empowers educators to tailor the learning experience to the specific needs and preferences of their students. The in-situ information associated with the virtual replicas enhances the quality of the educational content. Traditional static images and videos may lack the necessary depth and perspective for a comprehensive understanding of certain materials. In contrast, the virtual replicas in C1 offer a more dynamic and spatial representation, potentially bridging gaps in comprehension that might arise with traditional media. This is reinforced by one participant saying that “I was happy to see included small and larger environments. With images, it is very time-consuming to analyze larger environments. This can be very useful for multiple courses besides this one. Perhaps even models captured by drones can be seen? I saw something in the news that reminded me of this. Is it possible?”.

4.2. Participants’ Preferences and Profile Analysis

In addition, regarding participants’ preferences towards the conditions used, the Wilcoxon test rejected the null hypothesis (p-value < 0.000), indicating differences among methods, in this case, a significantly better rating of C1 (median = 6) compared to C2 (median = 3) ( = 10.50; = 0.00; Z = 3.98 (when N >= 20); p-value = 0.000089). Furthermore, categorizing the preference by gender and by experience with VR, we did not find a significant difference between males and females for both conditions, and participants with and without VR experience achieved the same median in each condition. Due to the small dimension of the two independent samples (categorized ones) and the use of an ordinal scale, the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the equality of the medians. Nevertheless, categorizing the preference by gender, it is worthwhile to see that in the traditional method, women assigned better values than men; on the other hand, concerning VR, there was a smaller dispersion for women. Categorizing by experience with VR, the ones with VR experience expressed smaller dispersion in both conditions. Furthermore, regarding participants’ profile (i.e., (Geoscience (15) vs. Computer Science (5)), the results indicate that participants’ preferences and ratings, as well as their reported values for all selected dimensions, did not differ significantly between the two groups when using condition C1. A similar pattern was observed for condition C2, with one exception: dimension D2—Effectiveness in perceived information understanding, which showed a statistically significant difference (Z= −2.359; p-value = 0.019), with Geoscience participants assigning higher ratings (median = 5) than Computer Science participants (median = 4). However, for all other dimensions, no significant differences were found. Overall, this analysis indicates that the participant profile had minimal impact on the study outcomes, supporting the robustness of the findings across disciplinary backgrounds.

4.3. Addressing the Research Question

Going back to the RQ: ‘Can 3D reconstruction, VR, and a Large Display be used to assist teachers with the educational process of specific geological phenomenons?’, the insights provided by participants underscore the value of the teacher-centric model.

The proposed VR-based framework reshapes traditional teacher–student interaction and knowledge transfer by enabling a shared, dynamic, and embodied exploration of geological phenomena rather than functioning merely as an enhanced display tool. Unlike traditional projection-based instruction, the author’s proposal allows the teacher to physically interact with spatially accurate geological replicas, rotating, scaling, annotating, and dissecting them in real time, while students collectively witness these actions on the large display. This creates a form of embodied teaching in which students observe not only the content but also the teacher’s spatial reasoning process, thereby supporting the development of their own spatial cognition. According to the data analyzed, the ability to manipulate and interact with content in real-time appears to be a crucial factor in improving communication regarding geological phenomena, offering the teacher a versatile toolkit to convey complex concepts. The asymmetric setup further enhances instructional dialogue, with the teacher’s manipulations guiding attention and understanding, while the students remain fully engaged as a group, able to ask questions, request specific views, or request clarifications without being isolated behind individual HMDs, as it happens with other existing approaches. In this way, the framework transforms the classroom into an interactive 3D reasoning space where knowledge is co-constructed through shared visualization, expert demonstration, and collective interpretation, going beyond the affordances of a conventional display.

Moreover, the insights collected underscore the importance of continuous improvement and customization of VR tools to meet the diverse needs of both teachers and students, emphasizing the significance of user feedback in refining and optimizing virtual learning environments. A key limitation identified in the current approach is the lack of opportunities for students to actively manipulate or contribute to the shared virtual content in real time, which some participants felt could further enrich the collaborative learning experience. Moving forward, new developments should explore alternative interaction methods, for example, by incorporating a shared tablet for student inputs, integrating an interactive projector (e.g., Sony Xperia Projector Touch) to enable direct manipulation on the classroom display, or even introducing a second VR headset to allow selective student immersion when pedagogically appropriate. Any extension of the framework must remain aligned with the low-cost requirement established early in the design process, as this constraint was emphasized by domain experts as essential for ensuring feasibility and broad adoption within the academic community.

6. Concluding Remarks and Future Work

This work explored a teacher-centric model exploring an asymmetric immersive collaborative setting within a classroom context. It focused on the use of a Virtual environment, incorporating 3D reconstructed models, which could be presented in a Large Display, besides the headset, for enhancing the education process of learning Geoscience. To understand if the proposed solution had the potential to be used in a real-life scenario, a user study with 20 participants was conducted, comparing said solution with the use of static images and videos, i.e., the traditional approach. The analysis of the study results reveals a clear tendency among participants toward the VR condition (C1) rather than the traditional condition (C2). All in all, the VR condition was characterized by having higher levels of attentional allocation (D1), effectiveness in communicating about the task (D3), as well as satisfaction (D6), as well as lower levels of mental effort (D5). As for the level of social presence (D4), C2 was rated higher, although with little representation, which may be explained by the fact that the traditional approach elicits a co-located communication mode, which C1 appears to affect, possibly by having the teacher immersed in the VR environment.

Our future work aims to empower students within the virtual learning environment. It will focus on incorporating content-authoring capabilities that enable students to develop their own materials within the virtual environment, in a manner comparable to instructors. This will not only foster a more interactive learning environment but also provide students with the tools to express their assumptions and questions. We are considering the use of a shared device by the students, which must be synchronized with the teacher interface to facilitate a collaborative environment in the classroom. Subsequently, we envision conducting an extensive user study involving a larger number of target users. This expanded study will enable us to thoroughly examine the potential distractions posed by the novelty of VR technology and its impact on the learning process. We also plan to evaluate various methods of interaction from the student’s perspective, assessing their effectiveness and user experience within the virtual environment. This comprehensive investigation will contribute valuable insights into the potential benefits and challenges of VR in educational settings.