Abstract

The correct assessment of slope stability under seismic loading requires not only the magnitude of ground acceleration to be considered but also its frequency content. In this study, a hybrid finite element/limit equilibrium (FEM–LEM) approach is used to quantify how the dominant frequency of harmonic ground motion affects the dynamic factor of safety, FSdyn, of a large homogeneous slope. Dynamic stresses are computed in QUAKE/W and transferred to SLOPE/W, where a FS calculation is performed at each time step to obtain FSdyn(t). A design-of-experiment framework is applied to explore combinations of peak ground acceleration and dominant frequency. The results show that FSdyn is much more sensitive to dominant frequency than to acceleration amplitude within the analyzed ranges, with the strongest reduction in stability occurring with the low input frequencies. Comparison with conventional pseudo-static analysis demonstrates that pseudo-static factors of safety can significantly overestimate stability at low dominant frequencies, and frequency thresholds are identified above which pseudo-static results become closer to the hybrid solution for the studied configuration. Although the model is intentionally simplified (homogeneous, drained conditions and single-frequency excitation), the findings highlight that dominant frequency is a decisive control parameter and should not be neglected in the seismic assessment of large earth structures.

1. Introduction

The occurrence of tailings storage facility (TSF) failures has drawn significant attention in recent years. Over the past 15 years, there have been a number of serious failures of Tailings Storage Facilities (TSFs) with devastating environmental, social and economic consequences [1,2]. The most tragic recent ones include the disasters in Mount Polley—Canada, 2014 [3]; Fundão/Samarco—Brazil, 2015 [4] and Brumadinho—Brazil, 2019 [5] which resulted in significant infrastructure damage, environmental pollution and numerous fatalities. The common factor contributed to many of these events was poor management practices, underestimation of geotechnical risks and lack of effective monitoring and assessment of embankment stability in dynamic conditions, including seismic events or heavy rainfall [6]; Databases and statistics developed by international organizations such as ICOLD [7] and GRID-Arendal [8] indicate that the frequency of TSF failures is not decreasing despite technological progress, which highlights the need to implement more advanced monitoring and risk analysis methods. Particular concern should be paid to the implications of seismic activities. Studies have reported that seismic events are a direct catalyst for approximately 17% of global TSF failures, with additional contributing factors including heavy rainfall and construction defects [9]. The catastrophic failures at notable sites such as Brumadinho and Mount Polley have served as crucial learning points for geotechnical engineering practices. These incidents underscored the inadequacies of traditional stability assessments, particularly the pseudostatic methods employed, which often disregard the complex dynamic interactions between seismic forces and material behavior [10].

Currently most of geotechnical stability calculations are conducted in pseudostatic approach. The pseudostatic calculation method has been widely adopted due to its simplicity and applicability in seismic stability evaluation. Initially introduced by Terzaghi, the pseudostatic approach simplifies the seismic loading conditions by replacing dynamic earthquake effects with equivalent static forces Lu et al. [11]. This method may incorporate two key forces: the vertical and horizontal inertial forces, representing the effects of seismic acceleration on slope stability [12]. Although this method allows for straightforward calculations and has been integrated into several engineering guidelines, it has notable limitations, particularly in its inability to account for dynamic characteristics such as frequency and wave propagation effects [13]. Research indicates that relying solely on this method can lead to an inaccurate assessment of safety factors, especially in complex geological settings [14,15]. Recent advancements highlight an essential contrast between traditional pseudostatic analysis and more sophisticated approaches, like probabilistic methods and finite element analysis, which consider the stochastic nature of seismic events more comprehensively [16]. Moreover, studies demonstrate a critical need for integrating dynamic response considerations into slope stability evaluations, as seismic waves can induce failures that are not captured by the static equivalents used in pseudostatic analysis [17]. Additional investigations underscore the significance of incorporating site-specific conditions, such as soil behavior during seismic loading, which can inform the limitations of the pseudostatic method when dealing with heterogeneous soil profiles [18]. Another research indicates that incorporating frequency-dependent analyses can significantly enhance prediction accuracy concerning TSF response during seismic events, as dynamic interactions can amplify the strength loss observed in water-saturated tailings [19]. Consequently, while the pseudostatic method remains a foundational tool in slope stability assessment, its limitations necessitate a transition towards dynamic analyses that can more accurately reflect the complex interactions between seismic forces and slope materials [20,21].

It must be highlighted that the challenge of accurately assessing slope stability is particularly critical in the context of TSFs, which are often situated—due to economic and logistical constraints—within zones affected by dynamic loading, such as those impacted by mining-induced seismicity. One of the most prominent examples of such a structure is the Żelazny Most TSF, located in southwestern Poland (Figure 1). It is not only the largest tailings impoundment in Europe, but also ranks among the largest facilities of its kind worldwide.

Figure 1.

Satellite view of the largest TSF in Europe—Zelazny Most.

Despite numerous studies focused on the stability of the Żelazny Most facility [20,22,23,24,25,26], none of the existing methodologies account for the influence of the dominant frequency of ground motion in their stability assessments. Instead, conventional analyses typically rely on pseudostatic or simplified dynamic approaches that may overlook the frequency-dependent amplification effects critical for accurately evaluating the response of large-scale earth structures under seismic excitation. This gap highlights the urgent need for more advanced, frequency-sensitive modeling frameworks-particularly for facilities like Żelazny Most, where the interaction between anthropogenic seismicity and embankment behavior represents a major safety concern.

This article presents a comprehensive analysis of the influence of the dominant frequency of seismic vibrations on the stability of slopes and large geotechnical structures. The research used a hybrid computational approach combining the finite element method (FEM) with the limit equilibrium method (LEM), which allowed for the dynamic determination of the stability factor FS under variable seismic load conditions. A series of numerical simulations were carried out using synthetic vibration courses with different dominant frequency, amplitude, duration and slope inclination. Based on the experimental plan and variance analysis, the influence of individual parameters on the FS value was determined. The obtained results were compared with the results of the classic pseudo-static analysis. The geometry of the slope considered in the analysis corresponds to the geometry of the TSF Żelazny Most, while the seismic wave characteristics (range of amplitudes, frequencies and durations) describing the interaction in the near wave field were prepared for the conditions prevailing in the Lower Silesian Copper Basin (LSCB) in accordance with the analysis presented in the article [2].

2. Material and Methods

In order to determine the influence of individual dynamic parameters of seismic waves on slope stability, a hybrid approach was employed by combining numerical analysis using the finite element method (FEM) with an analytical approach based on the limit equilibrium method (LEM). The results obtained from the hybrid calculations were subsequently used to conduct a statistical analysis of the impact of selected parameters on the FS value. The loading scenarios required to ensure the reliability of the results were determined using the Design-of-Experiment (DOE) method.

2.1. Numerical Model Preparation

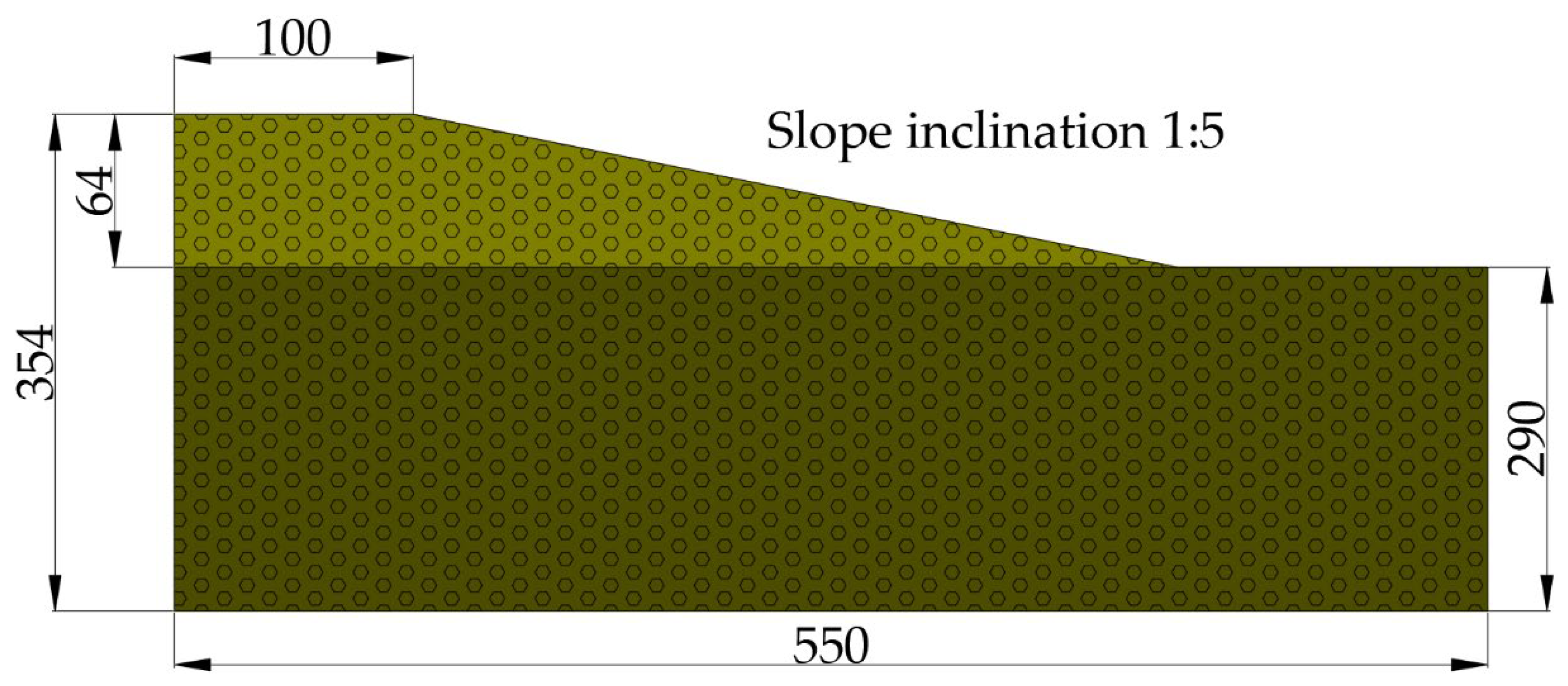

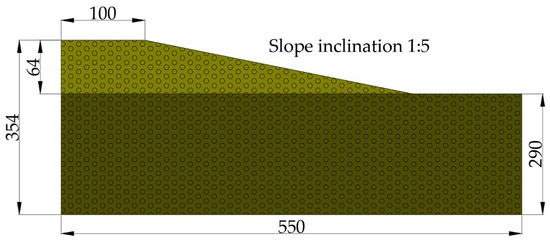

For the purpose of the analysis, a simplified geotechnical model of a slope was prepared, featuring a slope inclination of 1:5 and a total height of 64 m (Figure 2). It was assumed that both the subsoil and the embankment were composed of the same type of material-consolidated cohesive glacial till intermixed with coarse- and fine-grained sands. The geotechnical properties of the material were defined as follows: bulk unit weight γ = 20 kN/m3, Young’s modulus E0 = 100 MPa, Poisson’s ratio ν = 0.33, internal friction angle φ = 30°, and cohesion c = 5 kPa. These parameters were selected to reflect typical conditions observed in postglacial terrains and to ensure numerical stability of the model under dynamic loading conditions.

Figure 2.

Geometric configuration of the simplified slope model with an inclination of 1:5 and a total height of 64 m; the embankment and subsoil are composed of the same material. Dimensions are in meters.

The above material definition corresponds to a homogeneous Mohr–Coulomb model applied both to the embankment and the foundation. This choice was a deliberate simplification rather than a limitation of the software. The primary objective of the present work is not to reproduce a specific case history in full constitutive detail, but to clearly isolate and quantify the influence of the dominant frequency of ground motion on the FS. Introducing advanced, strongly nonlinear constitutive models with strain-dependent stiffness, cyclic degradation or liquefaction mechanisms would inevitably couple the response to a large number of additional parameters, making it difficult to attribute changes in FS solely to the frequency content of the excitation.

In other words, the numerical set-up was intentionally kept simple and transparent: a single material forming both the dam and the subsoil, a fixed geometry representative of large earth structures such as the Żelazny Most TSF, and a Mohr–Coulomb envelope with constant small-strain stiffness E0. Within this framework, all variations in FSdyn can be traced back directly to changes in the seismic input (frequency, amplitude and duration) rather than to constitutive details. This is consistent with the methodological goal of the paper, which is to demonstrate that the dominant frequency of ground motion cannot be neglected in stability assessments, especially in contrast to widely used pseudostatic approaches that ignore it by construction.

It should also be emphasized that, at present, commonly available dynamic analysis tools do not natively provide a time-dependent factor of safety for fully nonlinear constitutive models. The hybrid FEM–LEM workflow adopted here derives FSdyn indirectly from stress histories computed in QUAKE/W [27] and mapped to SLOPE/W [28]. Keeping the constitutive description as a homogeneous soil with constant elastic stiffness and Mohr–Coulomb strength parameters, i.e., without any modulus-reduction or cyclic degradation model ensures that this coupling remains numerically stable and that the obtained FSdyn(t) curves are not affected by additional numerical artifacts related to complex nonlinear soil models.

The algorithms used for the stability calculations using the limit equilibrium method are based on the determination of stress and force values that:

- Tend to ensure force equilibrium for each strip of the model;

- Define the same stability coefficient for each strip.

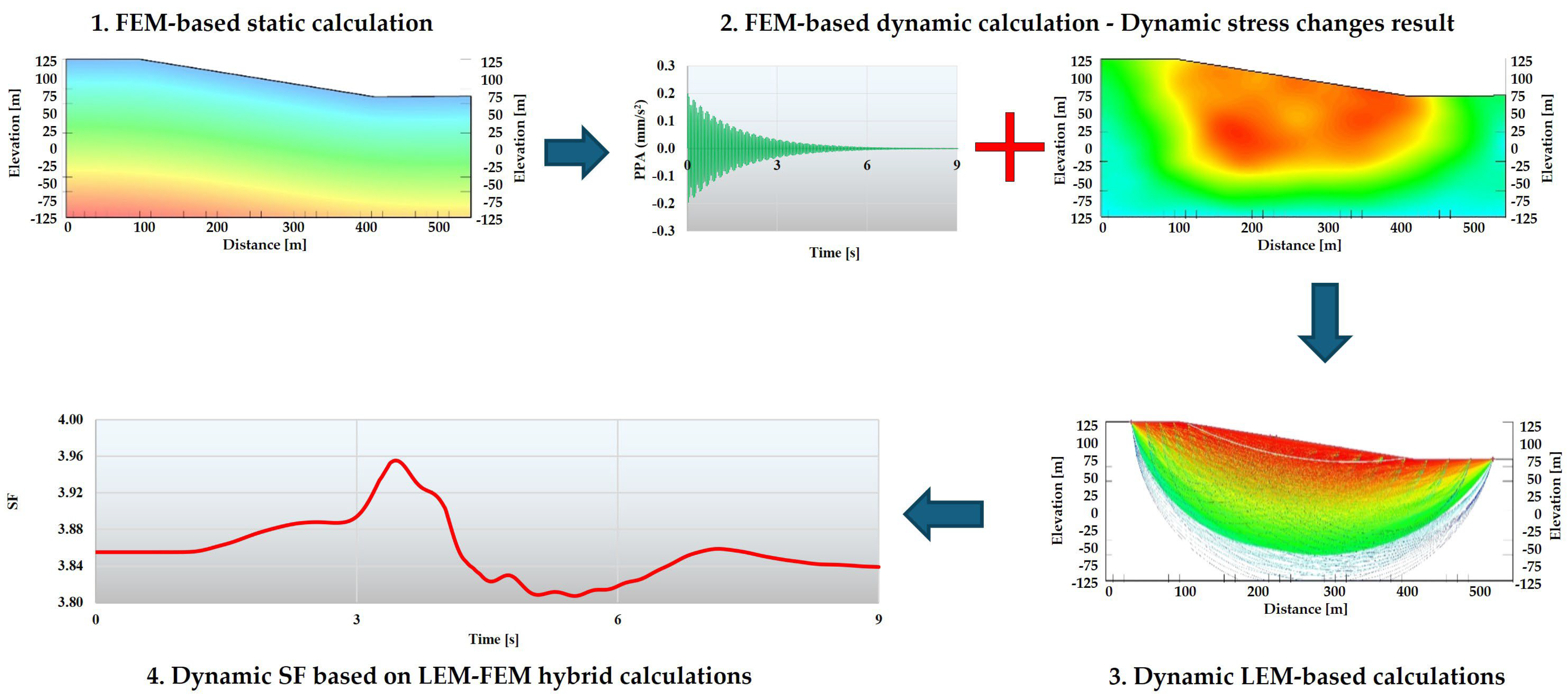

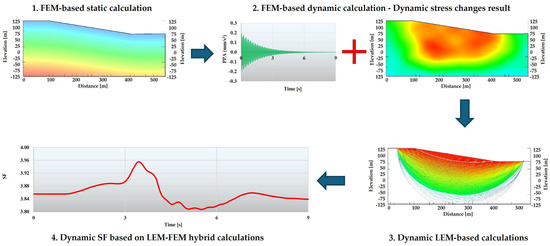

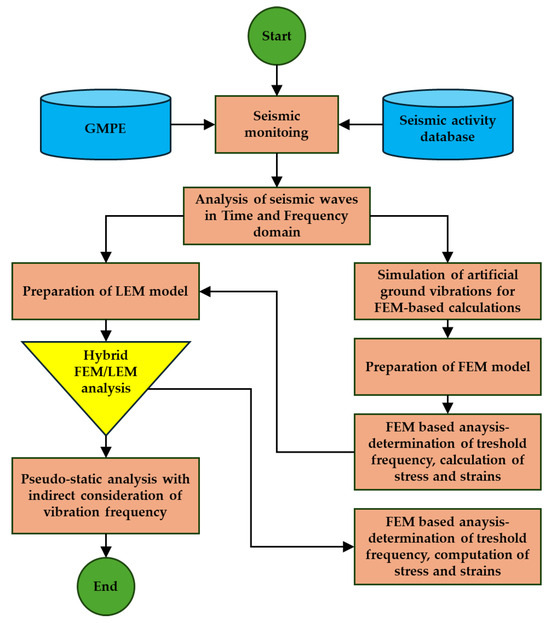

These simplifications and assumptions of the limit equilibrium method mean that it is not always possible to obtain a reliable stress distribution along the slip surface. Such an up-simplification can be bypassed in the case of implementing a relationship describing the stress–strain characteristics of the soil under the analyzed geometric, loading and material conditions. Considering such a relationship means ensuring the consistency of displacements in neighboring slices, which in turn leads to much more realistic stress distributions. One way to take into account the stress–strain relationship in the stability analysis is to first determine the stress distribution in the soil using the FEM analysis and then use these stresses in the stability analysis using the LEM, which, on the one hand, will allow for determining the permanent displacements within the calculation model, and on the other hand will be the basis for determining the dynamic change in the safety factor FS. A simplified procedure for calculating the dynamic change in the stability coefficient is shown schematically in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic procedure for determining the dynamic variation in the slope stability factor using the hybrid LEM–FEM approach.

The total stresses calculated in QUAKE/W represent the combined effect of both static and dynamic components. The static stresses are known from the predefined in situ stress conditions. Therefore, by subtracting the initial static stresses from the total stresses obtained in QUAKE/W, one can isolate the dynamic stress component:

These dynamic stresses can be computed at the base of each slice in the slope model. By integrating the shear stresses along the entire slip surface, it is possible to determine the total mobilized dynamic shear, which reflects the additional shear force induced by seismic shaking. Dividing this total dynamic shear by the mass of the potential sliding block yields the average acceleration of the sliding mass at each time step during the ground motion. Plotting this average acceleration against the corresponding factor of safety (FS) over time produces a dynamic response curve.

2.2. Simulation of Artificial Waveforms

In this study, synthetic seismic waveforms were employed to ensure a controlled and consistent basis for assessing the influence of dominant frequency on slope stability. The primary rationale behind this decision was the need to isolate and analyze the individual effect of frequency from other seismic signal parameters. In real-world seismic records, characteristics such as amplitude, duration, damping, and frequency content are highly variable and interdependent, making it difficult to determine the singular influence of one parameter on the FS.

To overcome this limitation, the synthetic waveforms were designed with fixed amplitudes, damping characteristics, and durations across all scenarios. Only the dominant frequency of the vibration was systematically modified. This approach allowed for the creation of a reproducible experimental framework in which the impact of frequency could be clearly identified, quantified, and interpreted without interference from confounding variables.

where a(t) is the amplitude of seismic wave acceleration in each time step (m/s2); amax is the maximum amplitude of seismic wave acceleration before attenuation (m/s2); β is the attenuation factor (1/s); t is time (s); ω is the natural frequency (rad/s); and φ is the initial phase (rad).

2.3. Safety Factor and Dynamic Safety Factor Calculations

The dynamic safety factor was calculated by coupling FEM-based QUAKE/W with LEM-based SLOPE/W software. Both software are part of GeoStudio package. In the first stage, the ground response to the input acceleration record was computed in QUAKE/W by solving the equation of motion:

where , , and are the mass, damping, and stiffness matrices, is the nodal displacement vector, and represents the seismic excitation applied at the model boundary. During calculation linear Rayleigh damping was used:

with and selected to match target modal damping over the frequency range of interest. From the transient solution element stress histories and a static reference state were extracted. Dynamic increments were defined as:

Then the acceleration-based (pseudo-dynamic) approach was implemented. Therefore, instantaneous inertial forces were applied to each slice of weight:

where and are the horizontal and vertical accelerations obtained from QUAKE/W and is gravity. Then from (5) was mapped to the candidate slip surface and converted internally by SLOPE/W into equivalent shear and normal loads acting along slice bases.

For each time step t, the limit equilibrium method (Morgenstern–Price) was solved. The available shear resistance on slice i followed the Mohr–Coulomb envelope:

with and are the effective strength parameters, is the slice-base length, is the effective normal force, and the method-dependent geometric factor. The instantaneous factor of safety was then:

where collects the driving components (static plus dynamic). The dynamic safety factor reported herein is the minimum over the excitation:

This workflow provides a full-time history FS(t) and the associated critical slip surface at the time t.

In practical terms, the coupling between QUAKE/W and SLOPE/W follows the standard workflow implemented in GeoStudio. Dynamic stresses are transferred using the built-in option in SLOPE/W. The procedure is as follows:

- In QUAKE/W, element stress histories are stored for the finite elements located along the potential sliding region;

- In SLOPE/W, the same mesh and candidate slip surfaces are defined and the import of stress values from the QUAKE/W results file is activated;

- For each time step t, SLOPE/W interpolates the imported stresses to the base of each slice and resolves them into normal and shear components acting on the slice base, which are then combined with the instantaneous inertial forces from Equations (6) and (7) in the Morgenstern–Price formulation.

This sequence of operations follows the step-by-step procedure described in the official QUAKE/W and SLOPE/W user manuals, so that any user with access to GeoStudio can reproduce the hybrid analysis by following the same series of commands. At each time step t, SLOPE/W performs a full search over a dense set of candidate slip surfaces. Consequently, the critical slip surface associated with FSdyn(t) is not fixed a priori, but may change its position and shape during the seismic excitation as the stress field evolves. All FSdyn values reported in this paper therefore correspond to the minimum factor of safety identified over all candidate slip surfaces.

To quantify the difference between the dynamic factor of safety—accounting for the ground-motion frequency content—and the frequency-independent pseudostatic factor of safety, a series of supplementary slope-stability analyses using the Morgenstern–Price method were performed. In this approach, constant seismic coefficients were defined based on peak acceleration values:

where and are horizontal and vertical seismic coefficients, while and are, respectively, horizontal and vertical peak ground accelerations.

Then, internal loads in subsequent slices of the model are calculated with:

Inter-slice shear was related to inter-slice normal by the MP (GLE) assumption:

where is unknown scale solved with FS, while is user-selected function evaluated at slice i.

Subsequently mobilized base shear on slice i was tied to available strength through:

where and φ′ denote the effective cohesion and friction angle, li denotes the slice-base length, and Ni′ = Ni − Ui denotes the effective base normal force (total normal Ni minus pore-pressure resultant Ui).

Ultimately FS is defined as the ratio of the available shear capacity summed along the slip surface to the shear demand required by slice equilibrium. For a given interslice closure scale λ from Equation (15), let denote the required base shear on slice i obtained after resolving all loads (slice weight, external actions, pore-pressure resultant):

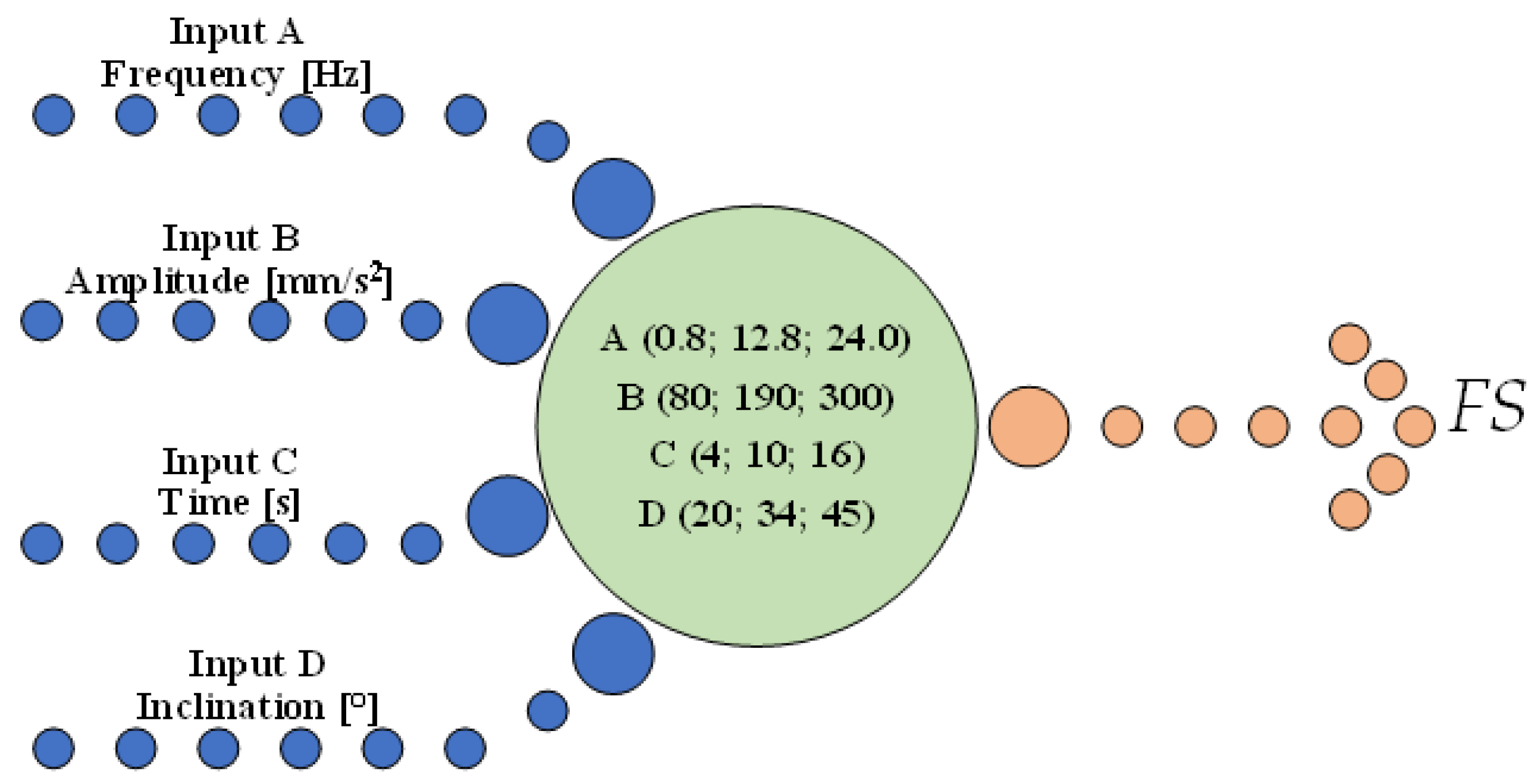

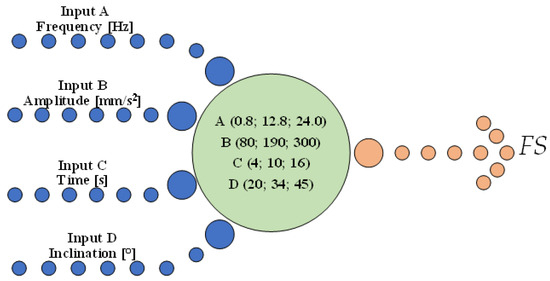

2.4. Design of Experiment (DOE)

The experiment was planned using the DOE procedure. For the purposes of this study, a fractional three-value plan 3(k-p) was used. To simplify the calculations, it was assumed that the factors influencing the slope stability take only three values—minimum, middle and maximum. Finally, a plan was selected that included 4 input parameters, i.e., frequency, amplitude, time and slope (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Values used in DOE.

The use of synthetic waveforms aligns with best practices in parametric numerical studies, where the Design-of-Experiment (DOE) methodology demands strict control of input variables to derive statistically meaningful conclusions. By applying a tri-level full factorial experimental plan, the analysis covered a broad spectrum of frequency values representative of seismic activity observed in the LSCB over the past two decades [2]. Since the analysis is based on numerical techniques, increasing the number of simulation scenarios does not generate significant additional costs. As a result, a full factorial design was adopted, comprising one block and a total of 27 computational configurations. The distribution of input parameters for each configuration is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of input parameter values used in individual computational configurations.

3. Results

3.1. Impact of Seismic Vibration Frequency on the Structural Integrity of an Embankment

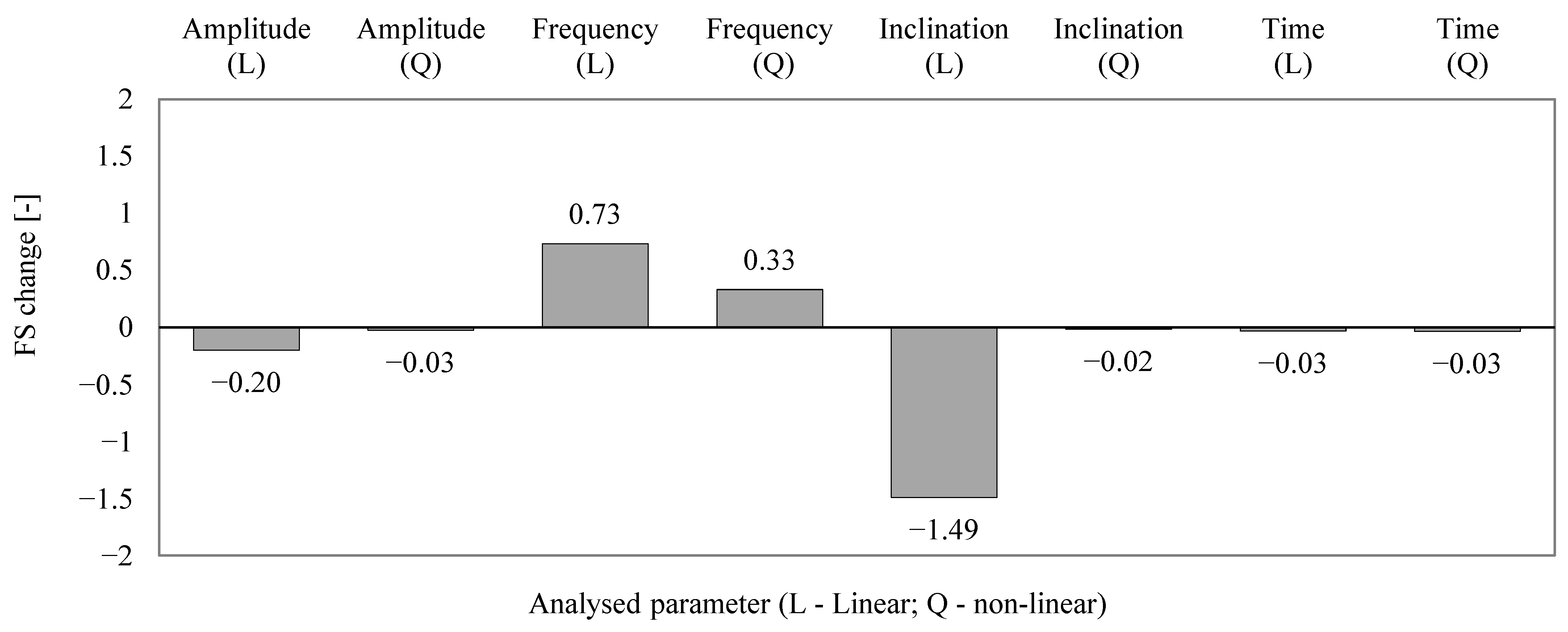

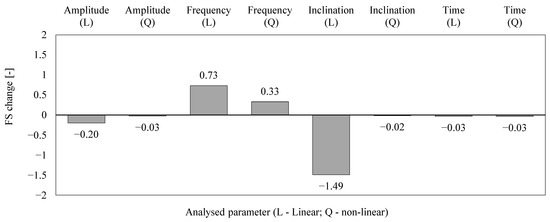

After completing calculations for all 27 models, the results necessary to implement the full three-level factorial design 3(k-p) were obtained. The computed safety factor values for each configuration are presented in Table 2. Based on the distribution of the dynamic safety factor FSdyn, a statistical analysis of variance was performed. The applied 3(k-p) factorial design allowed for the assessment of both linear (L) and quadratic (Q-nonlinear) effects of each input parameter (Figure 5). Ultimately, the variance analysis made it possible to determine which parameters have a statistically significant influence on the safety factor FS. According to the results, in addition to amplitude, the dominant frequency of seismic vibrations should also be considered a key parameter in numerical stability analyses.

Table 2.

Minimum safety factor (FS) values derived from the hybrid Finite Element Method (FEM) and Limit Equilibrium Method (LEM) analysis.

Figure 5.

Main effects plot illustrating the influence of input parameters on slope stability.

3.2. Hybrid FEM–LEM vs. Classical LEM Approach

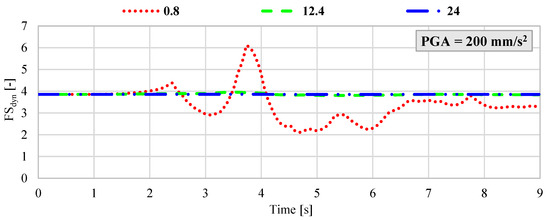

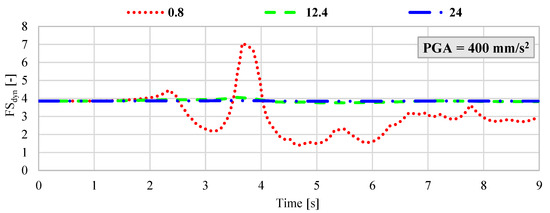

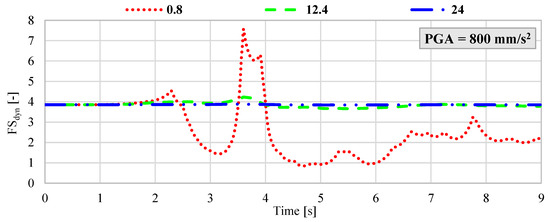

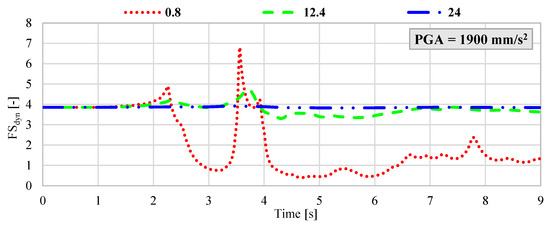

The analysis was carried out in accordance with the procedure illustrated in Figure 2, assuming conservative scenarios for peak ground acceleration (PGA). As indicated in work [15] in the case of the western dam of the Żelazny Most Tailings Storage Facility (TSF), recorded amplitudes of mining-induced ground vibrations generally do not exceed 800 mm/s2.

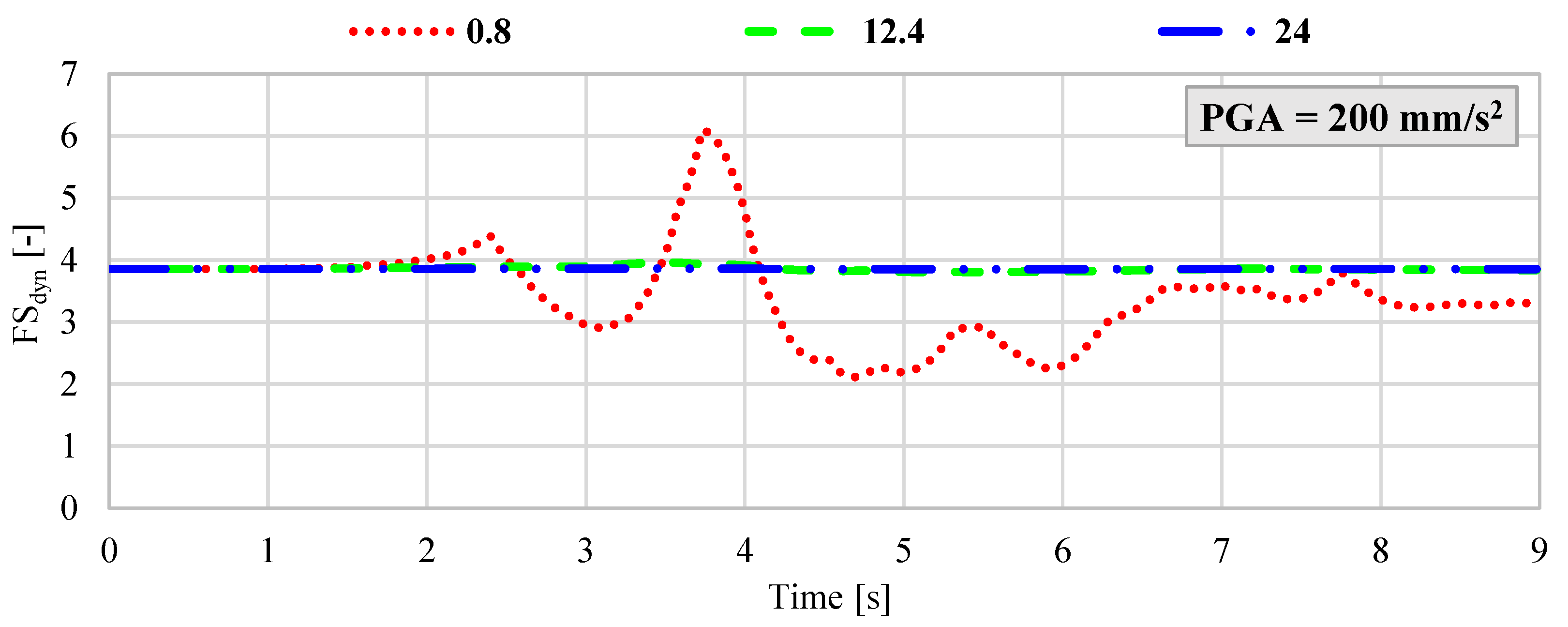

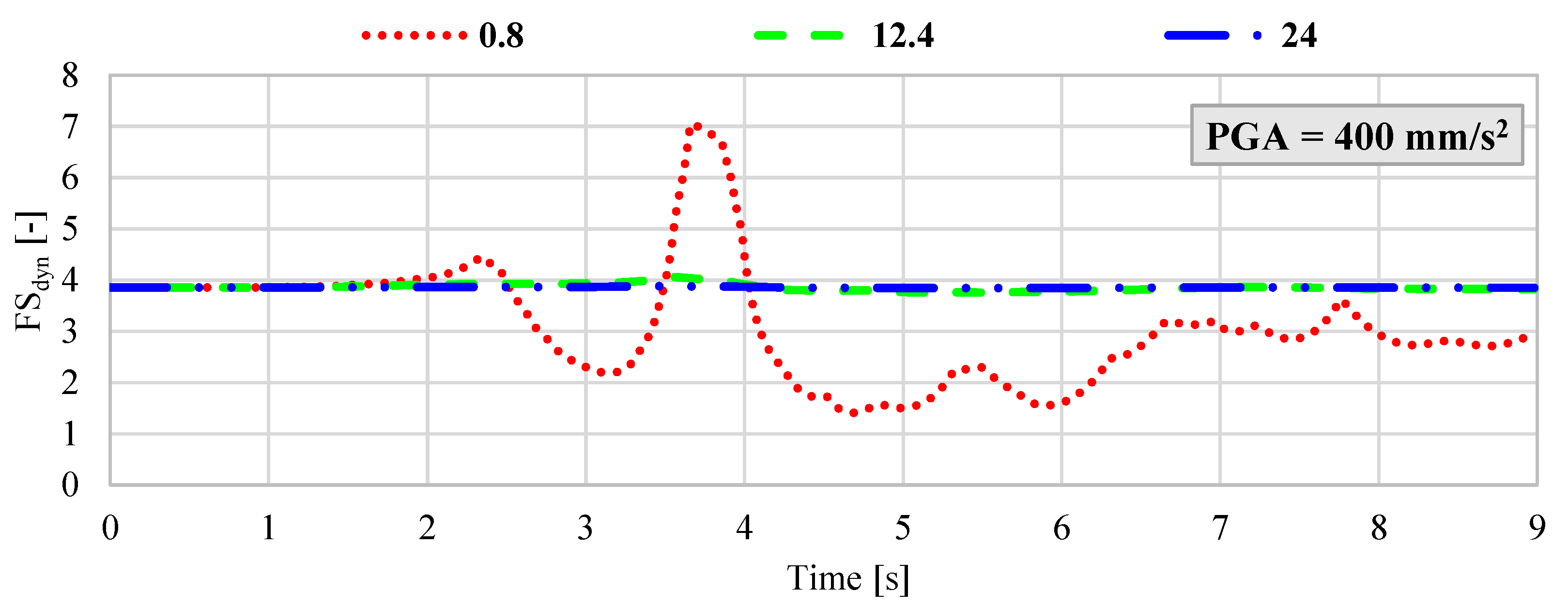

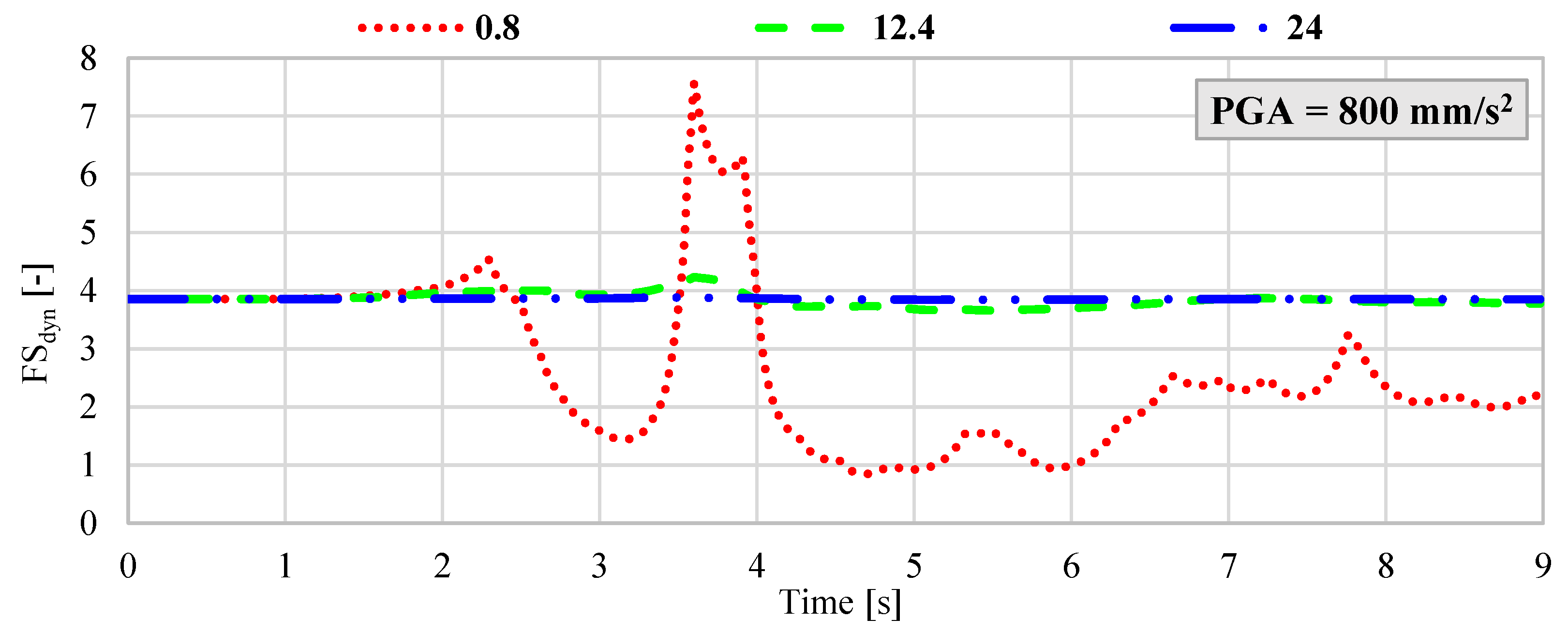

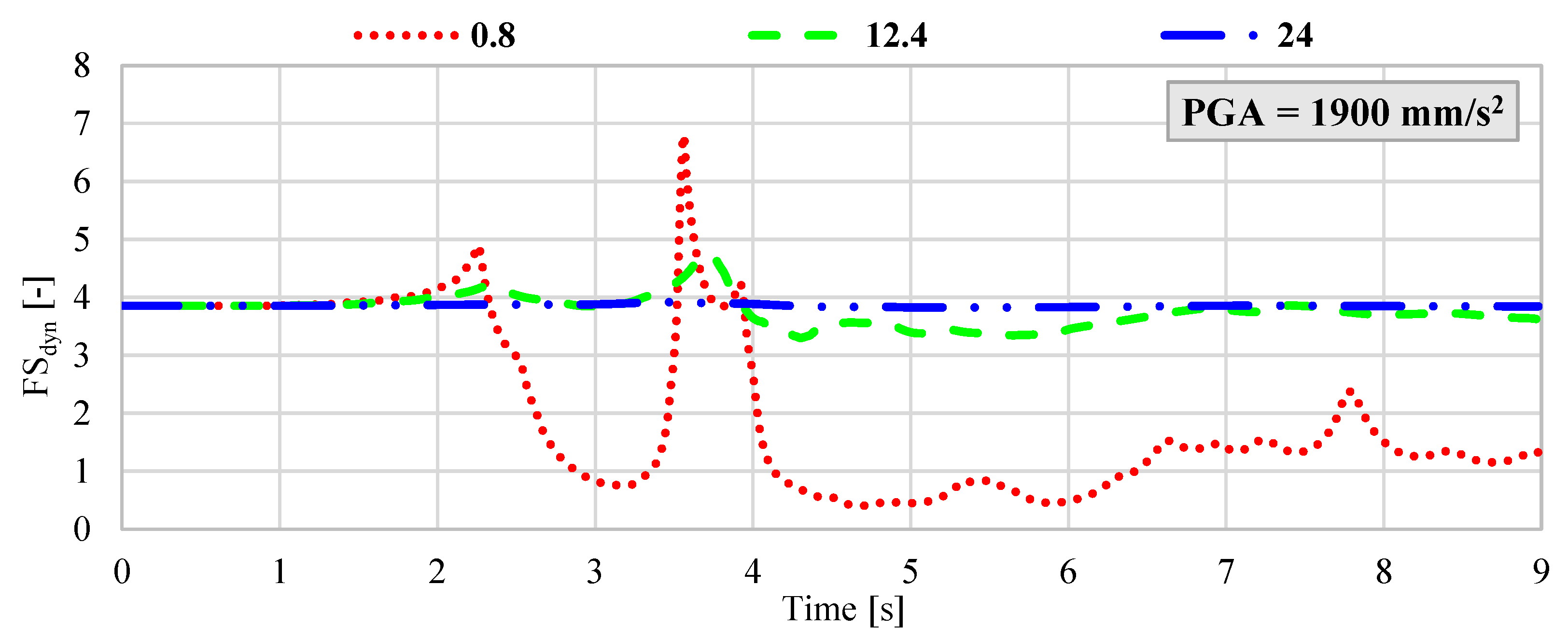

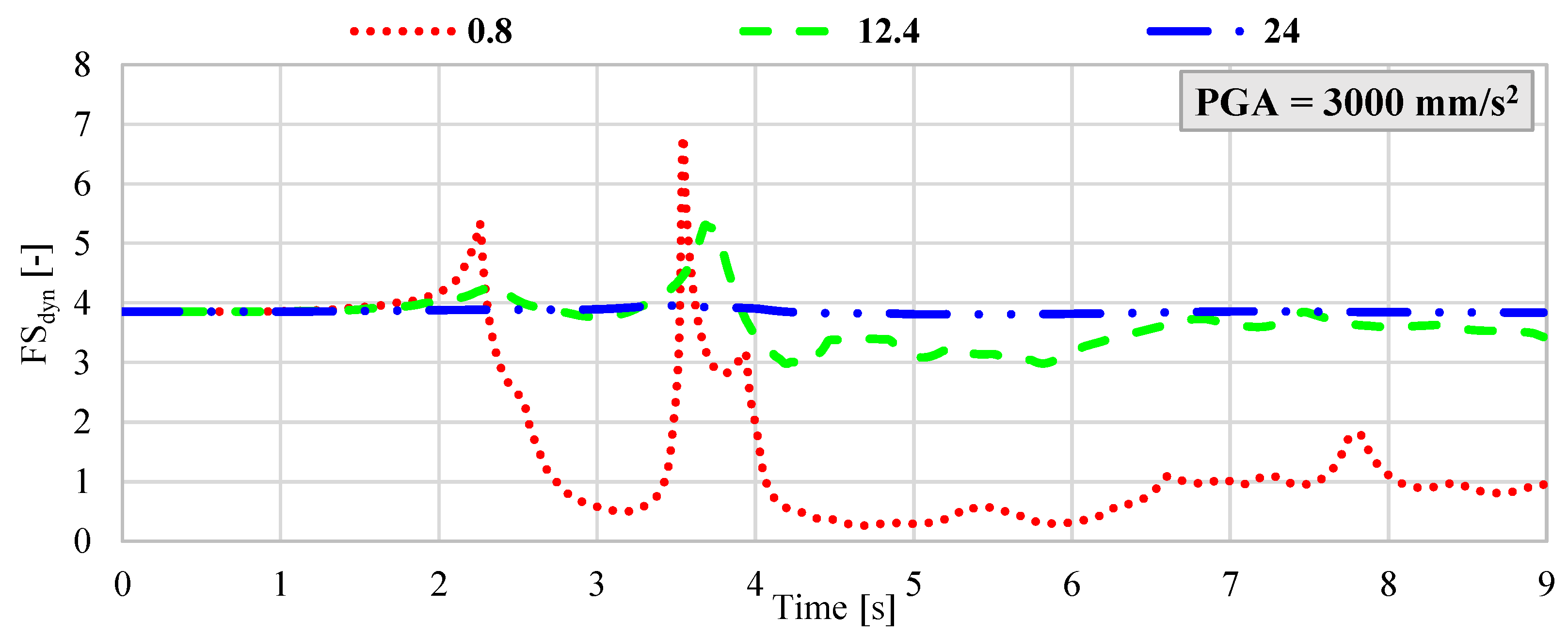

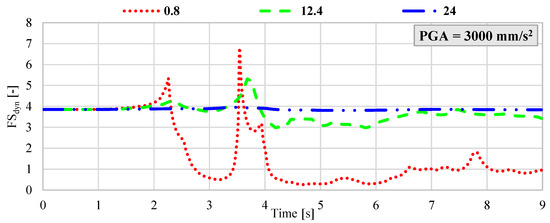

However, considering the ongoing mining operations in the vicinity of the protective pillar surrounding the Żelazny Most TSF, a reasonable scenario involves the occurrence of a seismic event with an energy release on the order of 5 × 108 J at a hypocentral distance of approximately 1500 m from the measurement station located on the dam. Under such circumstances, the estimated peak ground acceleration could reach values as high as 3000 mm/s2 [15]. Given this potential range, a hybrid FEM–LEM analysis was performed for the following maximum PGA values: 200 mm/s2; 400 mm/s2; 800 mm/s2; 1900 mm/s2; 3000 mm/s2. For each acceleration level, synthetic ground motion records were generated with dominant frequencies of 0.8 Hz, 12.4 Hz, and 24 Hz. The results, presented in Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10, illustrate the dynamic variation in FSdyn for each analyzed scenario.

Figure 6.

Dynamic variation in FSdyn for a large-scale geotechnical slope model subjected to seismic excitation with a PGA of 200 mm/s2 and dominant frequencies of 0.8 Hz, 12.4 Hz, and 24 Hz.

Figure 7.

Dynamic variation in the FSdyn for a large-scale geotechnical slope model subjected to seismic excitation with a PGA of 400 mm/s2 and dominant frequencies of 0.8 Hz, 12.4 Hz, and 24 Hz.

Figure 8.

Dynamic variation in the FSdyn for a large-scale geotechnical slope model subjected to seismic excitation with a PGA of 800 mm/s2 and dominant frequencies of 0.8 Hz, 12.4 Hz, and 24 Hz.

Figure 9.

Dynamic variation in the FSdyn for a large-scale geotechnical slope model subjected to seismic excitation with a PGA of 1900 mm/s2 and dominant frequencies of 0.8 Hz, 12.4 Hz, and 24 Hz.

Figure 10.

Dynamic variation in the FSdyn for a large-scale geotechnical slope model subjected to seismic excitation with a PGA of 3000 mm/s2 and dominant frequencies of 0.8 Hz, 12.4 Hz, and 24 Hz.

The results of the hybrid dynamic analysis clearly demonstrate that the dominant frequency of seismic vibrations has a significant impact on the stability of large-scale geotechnical structures. In particular, low-frequency vibrations below 1 Hz were found to be the most detrimental. When the dominant frequency was 0.8 Hz and the velocity amplitude exceeded 800 mm/s2, the analyzed system exhibited FSdyn values below 1.0, indicating a high likelihood of instability and potential failure. In contrast, for ground motions with dominant frequencies of 12.4 Hz and 24 Hz and PGA levels ranging from 200 mm/s2 to 800 mm/s2, the impact on FSdyn was minimal. The decrease in the safety factor was only marginal compared to the static load case, suggesting that higher-frequency vibrations within this amplitude range do not pose a significant threat to slope stability. However, as the seismic intensity increases, this behavior changes. For dominant frequencies around 12.4 Hz, a notable reduction in FSdyn was observed when PGA exceeded 1900 mm/s2. This implies that moderate-frequency seismic waves can also induce instability in high-energy scenarios, especially when combined with unfavorable geometric or geotechnical conditions. Summary of results with the identified minimum FSdyn is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results summary including the determined minimum value of FSdyn.

3.3. Mathematical Description of How FS Depends on the Dominant Frequency in the Analyzed Case

The initial analysis of the relationship between the minimum FSdyn and the dominant vibration frequency f was performed using independent logarithmic fits for each PGA level.

The adopted functional form, provided high coefficients of determination for each of the models (R2 = 0.966–0.997) across all the tested cases. This confirms that the logarithmic function adequately captures the empirical trend of rapid growth of FSdyn with increase in f (Table 4).

Table 4.

Parameters of logarithmic function fits describing the relationship between the minimum FSdyn and the dominant frequency f for different PGA values.

The analysis of parameters indicates that:

- The coefficient a increases with PGA, which means a higher initial growth rate of FSdyn as a function of f for higher accelerations;

- The intercept b decreases with PGA, which reflects lower FSdyn values at very low frequencies under high dynamic loads.

It has to be highlighted that, the logarithmic approach is purely empirical, without an asymptotic upper bound, and therefore cannot fully reflect the physical mechanism of stabilization at high frequencies. To introduce a physically consistent formulation, the data were subsequently fitted with a saturation-type exponential model:

where denotes the asymptotic safety factor at very high frequencies, while C(PGA) and k(PGA) are parameters dependent on the peak ground acceleration PGA. The parameter C(PGA) represents the initial gap between the low-frequency response and the asymptotic limit, and k(A) governs the rate of convergence towards .

Nonlinear regression of all data points (25 observations, five frequency levels and five PGA values) produced a common asymptote of

with C(A) increasing and k(A) decreasing with PGA. This behavior indicates that stronger seismic loading reduces the initial stability and requires higher frequencies to achieve model saturation. The model reproduces the dataset with high accuracy (RMSE = 0.065).

To generalize, the dependence of the parameters on PGA was captured by power-law relations:

with = 0.740, γ = 0.221, k0 = 0.798, and α = 0.212., where is scaling constant for the amplitude parameter, is power-law exponent for the dependence of C(PGA), k0 is scaling constant for the saturation rate parameter and α is a power-law exponent for the dependence of k(PGA).

Substituting these expressions leads to a compact two-dimensional predictive model in following form:

where PGA is given in mm/s2 and f in Hz. The global error of this predictive formulation is RMSE = 0.109

4. Discussion

The application of both logarithmic and saturation approaches provided a complementary view of the dependence of the safety factor on the dominant vibration frequency. The logarithmic model, while simple and highly accurate within the tested range, remains a purely empirical formulation, lacking the ability to determine the limiting value of FS or to establish explicit links with PGA. In contrast, the saturation model offers comparable fitting accuracy, but additionally defines the asymptotic limit F∞, accounts for the influence of PGA on the curve shape, and enables a physically consistent interpretation as well as extrapolation to high frequencies. Consequently, it represents a more universal and mechanistically grounded solution for modeling dynamic processes in geomechanics.

From a physical point of view, the fitted relationships should therefore be regarded as empirical descriptors of the frequency-dependent amplification of the slope–foundation system rather than as direct estimates of the mass, stiffness or damping of an equivalent single-degree-of-freedom (SDOF) oscillator. The asymptotic limit F∞ approximates the stability level reached when the excitation frequency is well above the fundamental modes of the system and dynamic amplification becomes small, while the coefficients C(PGA) and k(PGA) describe, respectively, the initial deficit in FS at low frequencies and the rate at which the system transitions toward this high-frequency regime. These trends are qualitatively consistent with the behavior of an equivalent SDOF system, but a rigorous identification of SDOF parameters for the present slope configuration would require a separate, more theoretical study and is beyond the scope of this paper.

Still, it must be pointed out that despite the high quality of fit within the studied range, the saturation model relies on the assumption of a common asymptote F∞ and an exponential approach towards it, which is a simplification of real dynamic processes. The parameters C(A) and k(A) were derived solely from five PGA values and five dominant frequency bands, which restricts the ability to generalize the model to other loading conditions.

At this stage it has to be kept in mind that extrapolation beyond the range A ∈ [200, 3000] mm/s2 and f ∈ [0.8, 24] Hz may lead to significant errors. Furthermore, the method does not account for nonlinear material effects or the full dynamics of the phenomenon, since is based on simulated waveforms, and should therefore be regarded as a supplementary tool for describing trends and comparisons rather than as a standalone method for dynamic stability assessment. Moreover, both the developed saturation model and the logarithmic fits are applicable only to the specific slope geometry and the geotechnical parameters of the analyzed soil layers; their applicability beyond this configuration requires recalibration. Extending the study to real vibration records (not based on harmonic decomposition) may lead to different, and likely less conservative, quantitative results. Nevertheless, the methodology remains valid: the fitting procedure (logarithmic and saturation), the derivation of F∞, C(A), and k(A), as well as the analysis of sensitivity and saturation thresholds, can be directly applied to new datasets once they are recalibrated.

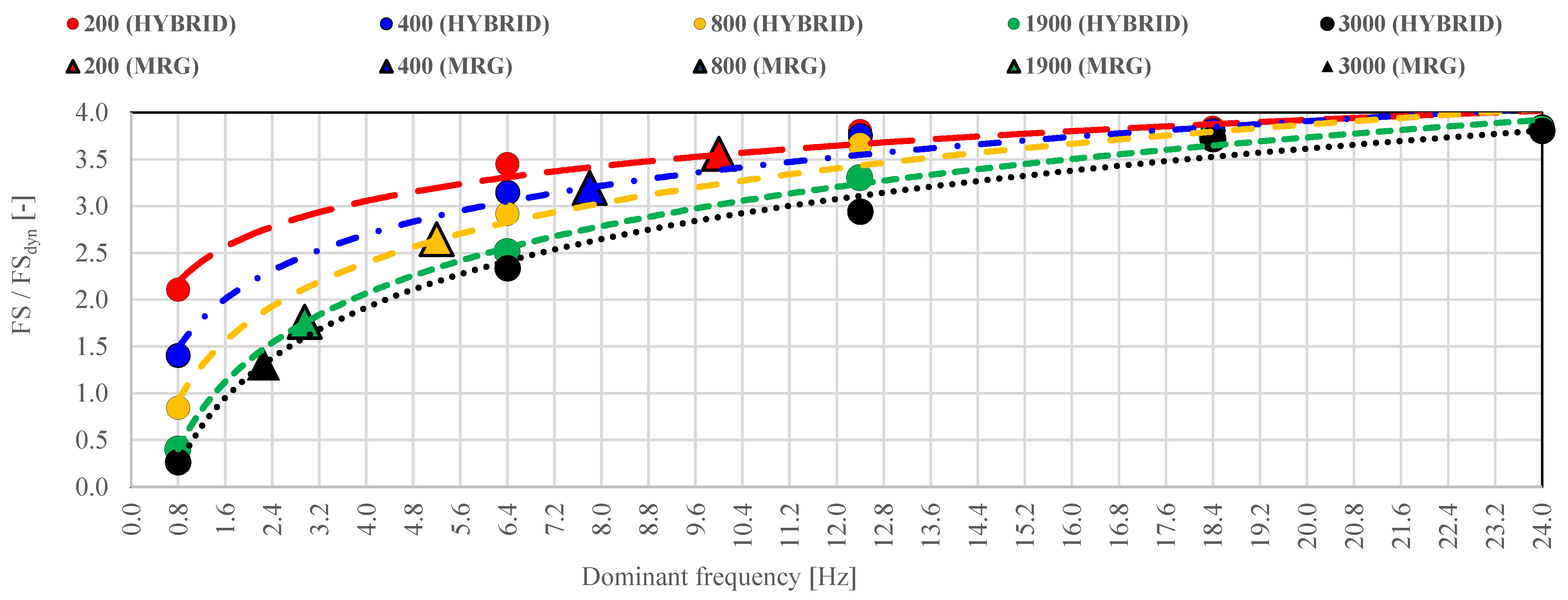

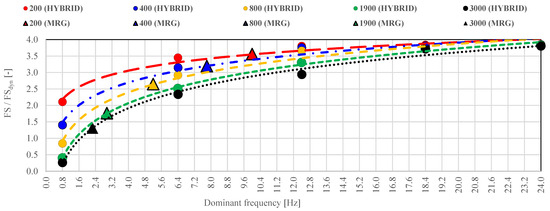

An important aspect that reinforces the practical applicability of the hybrid FEM–LEM dynamic approach is its comparison with the traditionally adopted pseudostatic method, particularly using the rigorous Morgenstern–Price limit equilibrium formulation. This comparison enables an objective evaluation of the benefits and limitations of each method under identical loading scenarios. To this end, the minimum FSdyn values obtained for each dynamic case (illustrated in Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10) were compared against the FS values derived from the corresponding pseudostatic analyses. This side-by-side comparison provides insight into the extent to which the pseudostatic method may overestimate or underestimate slope stability under seismic excitation. The results of this comparison are summarized in Figure 11, which highlights the frequency-dependent discrepancies between the two approaches.

Figure 11.

Comparison of minimum safety factor (FS) values obtained from the pseudostatic analysis (LEM–Morgenstern–Price) and the FEM–LEM-based FSdyn.

This analysis confirms that the hybrid method captures important dynamic effects neglected in the pseudostatic framework and should therefore be considered in risk assessments for large geotechnical structures subjected to complex seismic loading. Figure 11 clearly demonstrates that while the pseudostatic method may be sufficient in high-frequency, low-amplitude conditions, it significantly diverges from the dynamic response in the presence of low-frequency, high-energy seismic loading-conditions under which the hybrid analysis predicts critical reductions in FS. As shown in Figure 13, for each analyzed vibration amplitude, it is possible to identify a threshold dominant frequency below which the hybrid method becomes necessary for a realistic evaluation of stability. Conversely, for dominant frequencies above this threshold, the conventional pseudostatic approach may still provide reliable results-and in some cases, even overly conservative ones compared to the actual dynamic response. The data reveal a clear trend: as the PGA increases, the frequency threshold for which the hybrid method is required decreases. In other words, higher energy seismic events render even moderate frequencies dynamically significant, requiring a more advanced modeling approach. The threshold frequencies below which a hybrid FEM–LEM analysis is recommended for the examined PGA values are as follows:

- 200 mm/s2 → hybrid analysis should be applied for dominant frequencies ≤ 10 Hz;

- 400 mm/s2 → hybrid analysis should be applied for dominant frequencies ≤ 7.8 Hz;

- 800 mm/s2 → hybrid analysis should be applied for dominant frequencies ≤ 5.2 Hz;

- 1900 mm/s2 → hybrid analysis should be applied for dominant frequencies ≤ 2.9 Hz;

- 3000 mm/s2 → hybrid analysis should be applied for dominant frequencies ≤ 2.2 Hz.

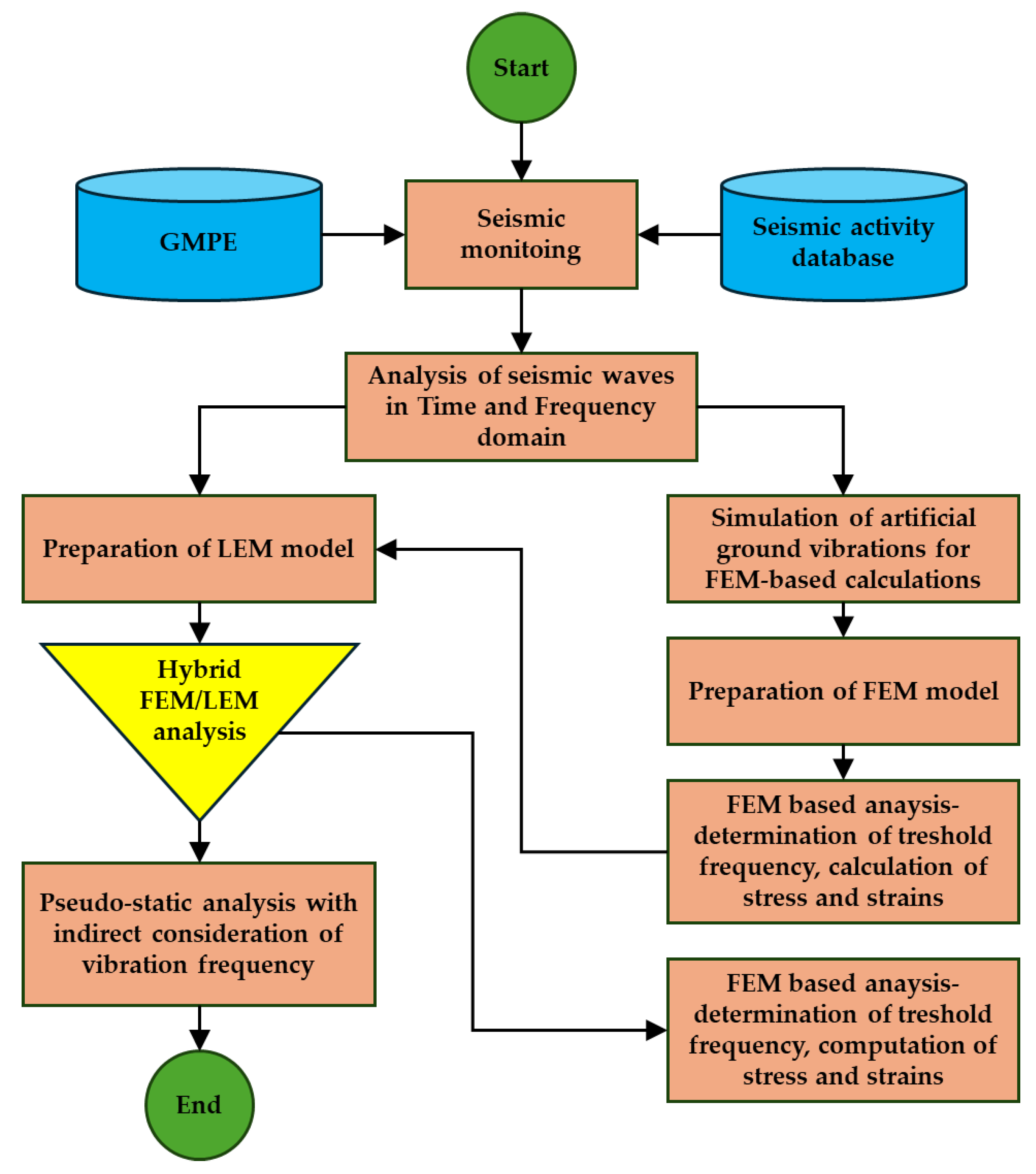

These results underscore the limitations of the pseudostatic method in capturing the destabilizing influence of low-frequency, high-intensity ground motions and provide a clear guideline for selecting appropriate modeling strategies based on site-specific seismic loading characteristics. Figure 12 shows the procedure for determining the dynamic stability index taking into account the effect of frequency on the structural stability of the object.

Figure 12.

Block diagram illustrating the individual steps for determining the slope dynamic safety factor (FSdyn) with indirect consideration of vibration frequency.

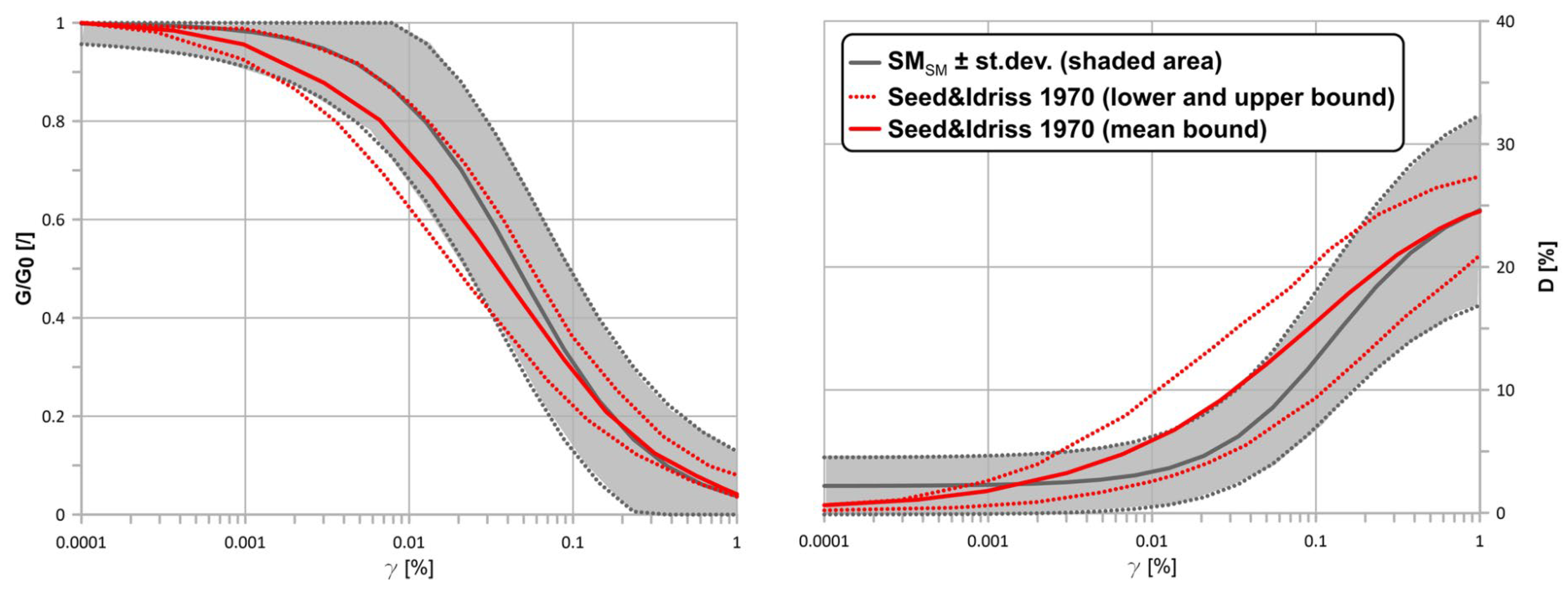

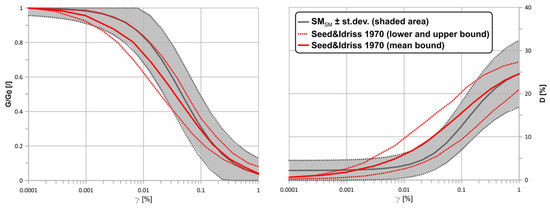

From an engineering perspective, it is important to indicate how the linear-elastic assumption may bias the results. For high-frequency motions and moderate PGA, shear strains remain small, so the difference between a constant-stiffness Mohr–Coulomb model and a nonlinear, strain-dependent model should be limited and the FSdyn values obtained here can be treated as a reasonable approximation of the actual stability. For low-frequency, large-amplitude motions (f ≈ 0.8 Hz and high PGA), real tailings and foundation soils would exhibit pronounced stiffness degradation and cyclic strain accumulation, so our simplified model is likely to overestimate stability; a more realistic nonlinear model would yield lower FSdyn values, which reinforces the conclusion that low-frequency excitation is most critical for large earth structures.

This interpretation is consistent with Figure 13. The left panel shows the normalized shear modulus reduction curve G/G0 from Gaudiosi et al. [29], together with the classic Seed and Idriss bounds [30]. The mean shear modulus (black) indicates that G/G0 ≈ 1 at very small strains (γ ≲ 0.001%), but typically decreases to about 0.4–0.7 for intermediate strains (γ ≈ 0.01–0.1%), i.e., in the range relevant for strong, low-frequency shaking. The right panel shows the accompanying increase in damping ratio D. Thus, when seismic loading drives the soil into this strain range, a nonlinear model with modulus reduction and increased damping would predict lower FSdyn than reported here, while the overall trend of increasing FSdyn with frequency would remain.

Figure 13.

Normalized shear modulus reduction G/G0 (left) and damping ratio D (right) versus cyclic shear strain γ for a sand-like soil [29].

In addition, the present analysis neglects the dynamic generation and dissipation of pore water pressure and therefore effectively represents dry or well-drained conditions. As a consequence, the results are not intended for direct application to collapsible loess, highly saturated tailings deposits or fully saturated silty foundations without further model development. In such materials, pore pressure build-up and partial loss of effective stress would further reduce both FS and FSdyn, especially under low-frequency, high-amplitude motions. The factors of safety reported here should therefore be interpreted as optimistic stability estimates for drained conditions, while the qualitative conclusions regarding the influence of dominant frequency are expected to remain valid when realistic pore pressure evolution is introduced in future, fully coupled hydro-mechanical analyses.

At the same time, the frequency-dependent FSdyn framework proposed here could be integrated into modern probabilistic slope stability and failure probability assessment methods, which have recently been applied to seismic and rainfall-induced landslides [31,32,33].

5. Conclusions

The correct evaluation of slope stability under additional dynamic loads remains one of the major challenges in contemporary geotechnics. Despite significant advances in monitoring techniques and the development of increasingly sophisticated numerical methods, catastrophic slope failures continue to be recorded worldwide. The present study addressed this issue by investigating the dynamic variation in the safety factor (FS) for an example slope using a hybrid FEM–LEM computational framework. The calculations were based on synthetic seismic waveforms characterized by different dominant frequencies and amplitudes, within the range of ground motion parameters observed in the Lower Silesian Copper Basin (Poland) between 2002 and 2025. Two complementary modeling approaches were applied to describe the relationship between FSdyn and dominant frequency. The logarithmic model, although purely empirical, provided excellent fitting accuracy across all PGA levels and confirmed the strong dependence of stability on frequency content. The saturation-type model achieved comparable accuracy, but additionally introduced a physically interpretable asymptotic limit F∞ and allowed the explicit characterization of PGA-dependent parameters. Both approaches consistently indicated that the stabilizing effect of seismic vibrations is most pronounced in the low-frequency band (1–10 Hz), while at higher frequencies the rate of FS increase diminishes and the curves converge toward a common asymptote.

The findings underline that reliance solely on pseudostatic methods—based only on peak ground acceleration—may overlook the crucial influence of frequency content on slope performance. The proposed methodology, combining numerical simulation with mathematical modeling, provides a more complete framework for analyzing the seismic response of large-scale geotechnical structures.

The present conclusions are directly applicable to large, predominantly homogeneous, drained slopes subjected to narrow-band excitation in the range of ground motion parameters typical for the Lower Silesian Copper Basin. For heterogeneous stratigraphy, partially saturated or highly compressible materials, or broad-band earthquake records, additional caution is required and the quantitative values of FSdyn may change. Nevertheless, the demonstrated sensitivity to dominant frequency remains an important warning that design checks based solely on peak ground acceleration can be non-conservative for critical earth structures exposed to low-frequency seismic loading.

In future work, the approach will be extended to real seismic waveforms generated by mining-induced events with magnitudes from ML = 2.5 up to ML = 4.5, recorded within 5 km of the site. Accurate reproduction of time histories and comparative analyses across different slope geometries and material configurations will enable a detailed sensitivity assessment. This represents an essential step toward enhancing the accuracy and reliability of geotechnical stability analyses, particularly in regions affected by induced seismicity.

Finally, it should be emphasized that the present study adopts a deterministic FS framework. In parallel with such deterministic approaches, there is a growing body of work on probabilistic slope stability and failure probability assessment, which aims to quantify the likelihood of failure rather than only providing a single safety margin. Integrating the frequency-dependent FSdyn response obtained here into probabilistic or reliability-based frameworks represents a natural direction for future research, in line with recent developments in probabilistic geotechnical analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.F. and L.S.; methodology, K.F. and L.S.; software, K.F.; validation, K.F., L.S. and B.P.-W.; formal analysis, K.F. and B.P.-W.; investigation, K.F., L.S. and B.P.-W.; resources, K.F. and L.S.; data curation, K.F.; writing—original draft preparation, K.F., L.S. and B.P.-W.; writing—review and editing, K.F., L.S. and B.P.-W.; visualization, K.F.; supervision, K.F.; project administration, K.F.; funding acquisition, K.F. and B.P.-W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been prepared through the project no. I/18/0003 financed by KGHM CUPRUM Ltd. R&D Centre in a frame of innovation fund. APC was co-founded with the research subsidy of the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education granted for 2025.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the representatives of the KGHM Polska Miedź SA for their support and the possibility of taking measurements of the mining-induced seismicity.

Conflicts of Interest

Krzysztof Fuławka and Lech Stolecki are affiliated with the Rock Engineering Department of KGHM Cuprum Ltd. The other author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TSF | Tailings Storage Facility |

| LSCB | Lower Silesian Copper Basin |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| LEM | Limit Equilibrium Method |

| FS | Factor of Safety |

| FSdyn | Dynamic Factor of Safety |

| PGA | Peak Ground Acceleration |

| DOE | Design of Experiments |

| MP | Morgenstern–Price |

| GLE | General Limit Equilibrium |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| F∞ | Asymptotic stability factor at very high frequencies |

| ICOLD | International Commission on Large Dams |

References

- Fuławka, K.; Pytel, W.; Pałac-Walko, B. Near-field measurement of six degrees of freedom mining-induced tremors in Lower Silesian Copper Basin. Sensors 2020, 20, 6801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuławka, K.; Stolecki, L.; Jaśkiewicz-Proć, I.; Pytel, W.; Mertuszka, P. The analysis of seismic load characteristics observed in the Lower Silesian Copper Basin. EPS 2020, 2, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabolotnii, E.; Morgenstern, N.R.; Wilson, G.W. Mechanism of failure of the Mount Polley tailings storage facility. Can. Geotech. J. 2022, 59, 1503–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, R.L.; Alves, P.R.; Di Domenico, M.; Braga, A.A.; De Paiva, P.C.; D’Azeredo Orlando, M.T.; Sant’Ana Cavichini, A.; Longhini, C.M.; Martins, C.C.; Neto, R.R.; et al. The Fundão dam failure: Iron ore tailing impact on marine benthic macrofauna. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva Rotta, L.H.; Alcântara, E.; Park, E.; Negri, R.G.; Lin, Y.N.; Bernardo, N.; Mendes, T.S.G.; Souza Filho, C.R. The 2019 Brumadinho tailings dam collapse: Possible cause and impacts of the worst human and environmental disaster in Brazil. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2020, 90, 102119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivapriya, S.V.; Anne Sherin, A. Causes and consequences of dam failures—Case study. In Sustainable Practices and Innovations in Civil Engineering; Naganathan, S., Mustapha, K.N., Palanisamy, T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; Volume 179, pp. 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Commission on Large Dams (ICOLD). ICOLD Official Website. Available online: https://www.icold-cigb.org/GB/icold/icold.asp (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- GRID-Arendal. GRID-Arendal Official Website. Available online: https://www.grida.no (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Atif, I.; Cawood, F.T.; Mahboob, M.A. Modelling and analysis of the Brumadinho tailings disaster using advanced geospatial analytics. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2020, 120, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirouz, B.; Lu, Z.; Javadi, S. Estimating rheological properties of liquefied tailings for dam break simulation using site-specific parameters and laboratory testing. In Paste 2023: Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Paste, Thickened and Filtered Tailings; Australian Centre for Geomechanics: Perth, Australia, 2023; pp. 629–638. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Jing, Y.; He, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X. Seismic stability study of bedding slope based on a pseudo-dynamic method and its numerical validation. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liao, H.; Zhou, D.; Zhu, J. Analytical solution for seismic stability of 3D rock slope reinforced with prestressed anchor cables. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifang, P.; Honggang, W.; Tao, Y.; Feifei, Z. Study on seismic coefficient calculation method of slope seismic stability analysis. Shock. Vib. 2021, 2021, 9986509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, J.; Fenton, G.A.; Griffiths, D.V. Probabilistic seismic slope stability analysis and design. Can. Geotech. J. 2019, 56, 1979–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuławka, K.; Kwietniak, A.; Lay, V.; Jaśkiewicz-Proć, I. Importance of seismic wave frequency in FEM-based dynamic stress and displacement calculations of the earth slope. Stud. Geotech. Et Mech. 2022, 44, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Wang, C.-W.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, L. Probabilistic investigation of the seismic displacement of earth slopes under stochastic ground motion: A rotational sliding block analysis. Can. Geotech. J. 2021, 58, 952–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-W.; Xue, E.-W.; Gu, X.-B.; Yang, C.; Zhao, C. Application of the principal component analysis–cloud model in the assessment of the seismic stability of slopes. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 11, 1330966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Sun, Q. Upper bound analysis of the anti-seismic stability of slopes considering the effect of the intermediate principal stress. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 10, 1023883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Qiao, F.; Bo, J.; Peng, D.; Li, Q. The influence of seismic frequency spectrum on the instability of loess slope. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świdziński, W.; Korzec, A.; Woźniczko, K. Stability analysis of Żelazny Most tailings dam loaded by mining-induced earthquakes. In Seismic Behaviour and Design of Irregular and Complex Civil Structures II; Zembaty, Z., De Stefano, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Li, L.; Xu, C.; Cui, Y.; Ding, H.; Huang, K.; Li, Z. A multi-objective optimization evaluation model for seismic performance of slopes reinforced by pile-anchor system. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łydżba, D.; Różański, A.; Sobótka, M.; Pachnicz, M.; Grosel, S.; Tankiewicz, M.; Stefanek, P. Safety analysis of the Żelazny Most tailings pond: Qualitative evaluation of the preventive measures effectiveness. Stud. Geotech. Et Mech. 2021, 43, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łydżba, D.; Różański, A.; Sobótka, M.; Stefanek, P. Optimization of technological measures increasing the safety of the Żelazny Most tailings pond dams with the combined use of monitoring results and advanced computational models. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2022, 68, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koperska, W.; Stachowiak, M.; Jachnik, B.; Stefaniak, P.; Bursa, B.; Stefanek, P. Machine learning methods in the inclinometers readings anomaly detection issue on the example of tailings storage facility. In Artificial Intelligence for Knowledge Management; Mercier-Laurent, E., Kayalica, M.Ö., Owoc, M.L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 614, pp. 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzanti, P.; Antonielli, B.; Sciortino, A.; Scancella, S.; Bozzano, F. Tracking deformation processes at the Legnica–Głogów Copper District (Poland) by satellite InSAR-II: Żelazny Most tailings dam. Land 2021, 10, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koperska, W.; Stachowiak, M.; Duda-Mróz, N.; Stefaniak, P.; Jachnik, B.; Bursa, B.; Stefanek, P. The tailings storage facility (TSF) stability monitoring system using advanced big data analytics on the example of the Żelazny Most Facility. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2022, 68, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GeoStudio. QUAKE/W—Dynamic Consolidation and Seismic Response Analysis, Engineering Book, 2022 ed.; Seequent: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- GeoStudio. SLOPE/W—Stability Modeling with Limit Equilibrium, Engineering Book, 2022 ed.; Seequent: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudiosi, I.; Romagnoli, G.; Albarello, D.; Fortunato, C.; Imprescia, P.; Stigliano, F.; Moscatelli, M. Shear modulus reduction and damping ratio curves joined with engineering–geological units in Italy. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seed, H.B.; Idriss, I.M. Soil Moduli and Damping Factors for Dynamic Response Analyses. In Earthquake Engineering Research Center Report EERC 70-10; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Wu, J.; Bao, H.; Li, B.; Shan, Z.; Kong, D. Advances in Statistical Mechanics of Rock Masses and Its Engineering Applications. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2021, 13, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Cui, H.; Zhang, T.; Song, J.; Gao, Y. A GIS-Based Tool for Probabilistic Physical Modelling and Prediction of Landslides: GIS-FORM Landslide Susceptibility Analysis in Seismic Areas. Landslides 2022, 19, 2213–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, T.; Chen, H. A New Theoretical Model to Locate the Back Scarp in Landslides Caused by Strength Reduction in Slip Zone Soil. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 159, 105410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).