1. Introduction

Approximately 40% of the world’s population lives within shared river basins, and nearly 90% in countries that depend on transboundary waters, with 14 economically dependent basins supporting over 1.4 billion people [

1]. As climate change accelerates hydrological variability and geopolitical tensions, cooperative transboundary water governance becomes indispensable for ensuring regional stability, environmental sustainability, and human security. Well-established legal and institutional frameworks—such as river basin organizations and treaties—are essential for mediating the interests of riparian states [

2]. Since the early 19th century, more than 450 treaties have been signed to govern shared water resources, underscoring the long-standing recognition of cooperation as a conflict mitigation tool [

3]. However, the effectiveness of these frameworks remains uneven across regions, and many developing countries continue to face significant governance and data gaps.

Water, however, is not just a source of life but also a source of power. Transboundary rivers, by their very nature, transcend national boundaries, transforming from natural resources into highly politicized entities shaped by competing claims over sovereignty, economic development, and environmental rights [

4]. In many regions—particularly those marked by fragile governance, weak infrastructure, and socio-political instability—transboundary rivers become flashpoints rather than connectors [

5]. The asymmetry in power and capacity between upstream and downstream countries further complicates negotiations [

6]. The dynamics of transboundary water politics are further complicated by climate change, which alters precipitation patterns, intensifies droughts and floods, and increases the unpredictability of water availability [

7]. In response, many states pursue unilateral water development projects such as dam construction and river diversions to secure their national interests. While these actions may offer short-term domestic benefits, they often generate downstream tensions and ecological degradation when undertaken without consultation or joint planning.

Nowhere are these issues more pronounced than in fragile states such as Afghanistan. Decades of war, institutional collapse, and underinvestment in water infrastructure have left Afghanistan unable to effectively harness or manage its hydrological resources. Although official figures once claimed that Afghanistan possessed 57 billion cubic meters of water, more recent estimates suggest a dramatic decrease of at least 10 billion cubic meters, reinforcing its classification as a water-stressed country [

8]. A significant portion of the basin’s surface water remains unutilized and flows into neighboring countries due to poorly functioning irrigation systems and insufficient storage infrastructure. The country’s traditional systems such as Karez (a

Karez (called

Qanat in Iran) is a traditional underground irrigation system that channels groundwater from mountains to agricultural land using gently sloping tunnels, thereby delivering water by gravity without pumping [

9]) have been disrupted, and many modern dams remain either unfinished or inoperative. The situation is further exacerbated by Afghanistan’s extreme vulnerability to climate change. The country has experienced a 1.8 °C rise in temperature since the 1950s—more than double the global average [

10]. This warming trend has intensified floods, droughts, and food insecurity. In 2022 alone, climate-related damages exceeded

$2 billion, with over 80% of the population dependent on agriculture, rural livelihoods are especially exposed [

11]. Climate shocks are also driving a shift from staple crops to drought-resistant opium, reinforcing cycles of conflict and displacement [

12]. Since the Taliban’s return to power in 2021, climate action and water infrastructure development have stagnated due to frozen international aid, isolation, and lack of institutional continuity. This national context is vividly reflected in Afghanistan’s transboundary rivers, where water scarcity and governance challenges intersect with regional politics.

The Harirud (Harirod) River, shared by Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkmenistan, stretches about 1100 km, originating in Afghanistan’s central highlands near the Baba Mountains in Bamyan. It flows westward through Herat province, forming parts of the Afghanistan–Iran and Afghanistan–Turkmenistan borders before dissipating into the Karakum Desert [

13]. The river is primarily snowmelt-fed, with peak flows in spring and early summer; its average annual discharge is estimated at 1.6 billion m

3 [

14]. However, due to climate change and upstream abstraction, flow variability has increased, intensifying water scarcity across the basin. Recent studies indicate a 29% decline in surface water resources, equivalent to a loss of about 0.98 billion m

3, caused by reduced winter precipitation, more intense but less frequent rainfall, and rising temperatures [

15]. In Afghanistan, the river sustains agriculture and hydropower through projects such as the Salma and Pashdan dams [

16], while in Iran’s Khorasan Razavi province, it supports irrigation and groundwater recharge. The absence of a binding water-sharing agreement has led to unilateral developments, and has heightened ecological and political tensions. Iran reports reduced flows and environmental degradation, whereas Afghanistan faces challenges asserting its sovereign water rights amid limited diplomatic recognition and institutional fragility [

17].

This fragile context illustrates the interplay of hydro-hegemony, environmental stress, and governance failure [

2]. Despite international legal frameworks such as the 1997 United Nations (UN) Watercourses Convention and the 1992 Helsinki Water Convention, over 60% of transboundary rivers globally, including the Harirud, lack any formal cooperative mechanism [

6]. In such situations, unilateralism thrives and conflict risks rise. This study focuses on the Harirud River Basin as a critical yet under-researched transboundary watercourse, examining how climate change and unilateral water development jointly undermine the sustainability and security of shared water governance in Afghanistan and Iran.

Despite its strategic importance, the Harirud River Basin has been comparatively neglected in the transboundary water literature, especially when compared to the Helmand River Basin or the Amu Darya Basin. This oversight is largely due to the basin’s smaller scale, limited international visibility, and the absence of a comprehensive water-sharing treaty, which in turn restricts access to reliable hydrological data and coordinated research activities [

18]. Additionally, decades of conflict and institutional fragility in western Afghanistan have impeded systematic field studies, while downstream-focused analyses often centre on reservoirs and canals in Iran and Turkmenistan rather than upstream Afghan dynamics [

19].

This study advances current scholarship by filling this empirical and analytical gap. Unlike earlier research on the Helmand or Amu Darya basins, which primarily examined treaty frameworks and conflict narratives, this paper provides an integrated analysis of the Harirud Basin that links climate-induced hydrological variability, unilateral development policies, and governance asymmetries. By situating these interactions within broader theories of hydro-hegemony and environmental security, the study contributes novel insights into how fragile upstream contexts shape transboundary water relations in politically unstable regions. The Harirud River Basin demonstrates a persistent governance gap in transboundary water management. Despite its environmental and geopolitical importance, Afghanistan and Iran lack effective cooperative institutions, a problem intensified by climate-driven water scarcity and hydrological variability. Similar global trends of unilateral water development have heightened tensions in many shared basins [

20,

21]. This is evident in the Harirud, where Afghanistan’s Salma and Pashdan dams have raised concerns downstream, while earlier projects such as the Doosti Dam were built without consulting Afghanistan [

22].

This study builds upon our earlier research in which we analyzed the drivers of transboundary water conflicts, including climate change, population growth, power asymmetries, and the uneven distribution of water resources. In this study we extend that research by focusing on the Harirud River Basin, aiming to evaluate how the combined pressures of climate change and unilateral water policies are eroding the potential for sustainable and equitable water governance between Afghanistan and Iran. The analysis is guided by three interrelated research questions: (a) What is the geopolitical and economic significance of the Harirud River in shaping Afghanistan–Iran relations? (b) How do unilateral interventions—such as dam construction and water diversions—affect the equitable and sustainable use of shared water resources? and (c) How is climate change transforming the basin’s hydrology, and what adaptive strategies could foster cooperative and sustainable transboundary water governance? By addressing these questions, the study aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of the interwoven challenges and potential solutions for sustainable governance of shared water resources in politically sensitive regions.

Finally, given the study’s reliance on secondary data and literature-based synthesis, its findings are interpretive rather than empirical. This limitation is mitigated through triangulation of diverse academic, institutional, and hydrological sources, ensuring that the analysis remains robust and representative despite data constraints.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopts a qualitative, descriptive research design to examine how climate change and unilateral actions shape governance and hydro-political dynamics in the Harirud River Basin, shared by Afghanistan and Iran. The interdisciplinary approach integrates political geography, environmental governance, and international water law, providing an analytical basis for exploring strategic, socio-economic, and ecological dimensions of transboundary water management. This design was chosen for its ability to generate an in-depth, contextualized understanding of water governance in a politically sensitive and data-scarce region.

Rather than testing hypotheses, the study interprets patterns and relationships among climate-induced hydrological variability, unilateral development initiatives, and their socio-political consequences. The analytical framework combines three complementary theoretical lenses—climate vulnerability analysis, hydro-hegemony theory, and transboundary water governance principles—to analyze environmental stressors, upstream–downstream power asymmetries, and institutional mechanisms (or their absence) for cooperation. Each lens and its application are detailed in the Analytical Framework section.

2.1. Initial Steps

A systematic literature review was conducted to compile insights on transboundary water governance, hydro-politics, climate impacts, unilateral development, and the Afghanistan–Iran water relationship. Searches were carried out using Google Scholar and major academic databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, JSTOR, ScienceDirect, and Wiley Online Library. The review focused on publications from reputable publishers such as Taylor & Francis, Springer, Wiley, Emerald, and MDPI, and applied predefined criteria: (i) peer-reviewed or reputable policy publications; (ii) direct relevance to transboundary water governance, climate impacts, hydro-politics, or unilateral development; (iii) English-language availability; and (iv) relevance to the Harirud River Basin or comparable international cases. To strengthen analytical reliability, secondary sources were cross-checked against international reports—such as those of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and the World Bank—as well as relevant bilateral agreements and national legal documents. Persian-language (Farsi/Dari) materials were selectively consulted to capture local perspectives and verify regional narratives not available in English.

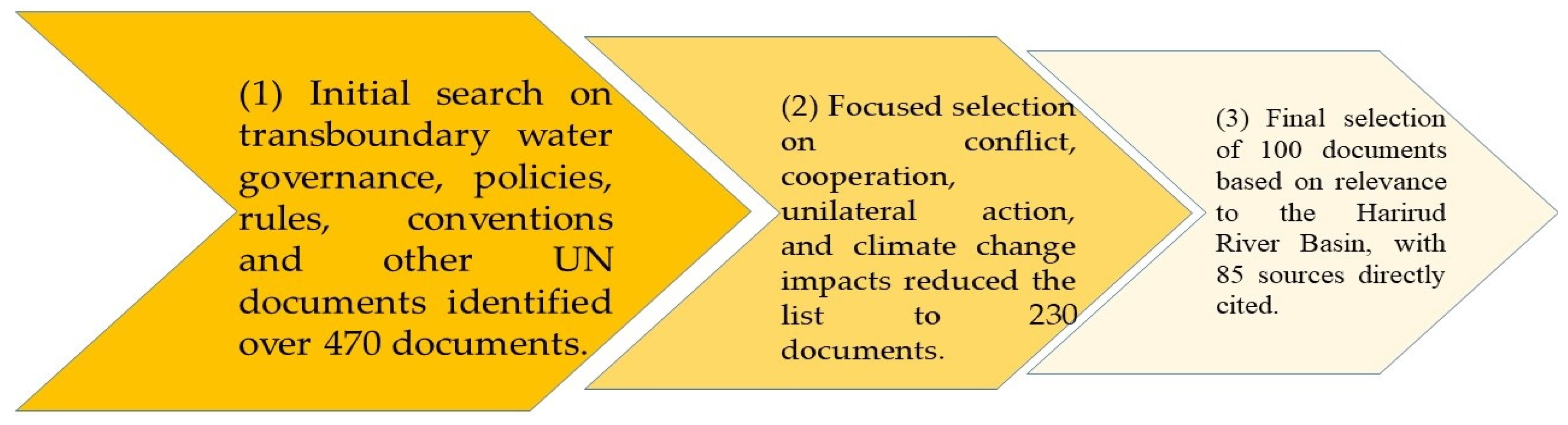

Publications were excluded if they were thematically irrelevant, duplicated, or lacked methodological rigor—defined here as the absence of a clear research design, transparent data sources, replicable analytical methods, or credible institutional authorship. Applying these criteria reduced an initial pool of over 470 records to a final dataset of 100 sources, of which 85 were cited.

Figure 1 illustrates this selection process and demonstrates the methodological transparency supporting the dataset. Persian-language (Farsi/Dari) materials were selectively incorporated to capture local perspectives, government reports, and contextual political information not available in English; these were used primarily to verify regional narratives and enhance cultural and historical accuracy.

2.2. Resource Eligibility and Selection Guidelines

Because the study relies entirely on secondary data and literature-based synthesis, particular emphasis was placed on triangulation to mitigate bias. Information was cross-validated across academic studies, institutional reports, and hydrological datasets from international agencies to ensure accuracy and consistency. This approach strengthens the validity of interpretations despite the absence of primary field data. The selected sources were reviewed for thematic alignment, methodological soundness, and empirical consistency. Abstracts, introductions, and conclusions were screened, followed by full-text reviews of materials meeting inclusion standards. This process ensured a credible and balanced representation of both global and regional perspectives, situating the Harirud River Basin within the wider discourse on transboundary water governance and climate adaptation.

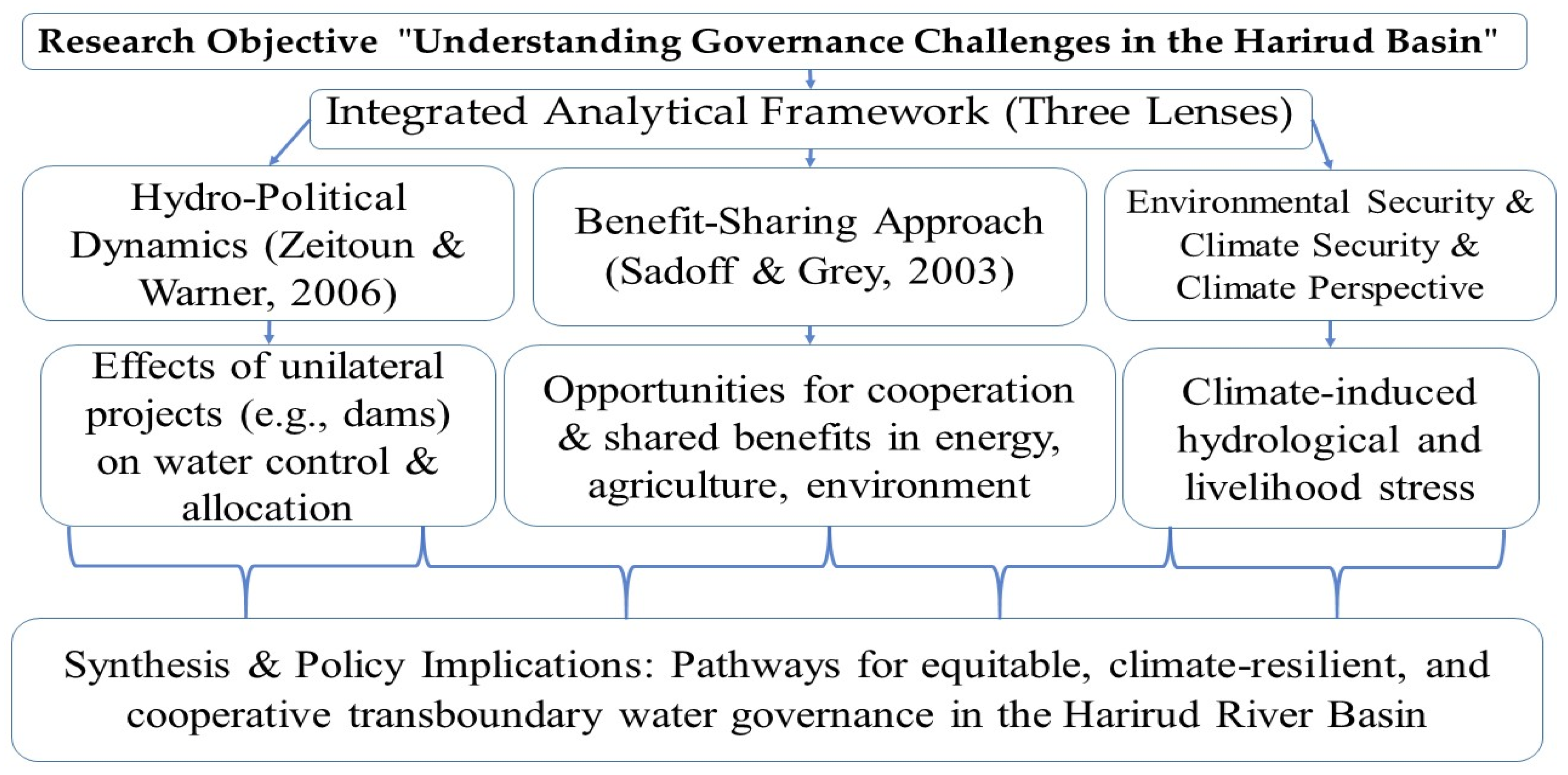

2.3. Analytical Framework and Mapping of Sources

This study applies an integrated framework combining hydro-political dynamics, benefit sharing, and environmental security/climate resilience to examine governance in the Harirud River Basin (

Figure 2). Hydro-political dynamics [

6] assess how unilateral projects such as the Salma and Dosti dam of Iran Turkmenistan influence control and allocation of shared water. The benefit-sharing approach [

23] identifies opportunities for cooperation despite historical tensions, while environmental security and climate resilience perspectives evaluate how droughts, hydrological variability, and climate change affect water governance and livelihoods.

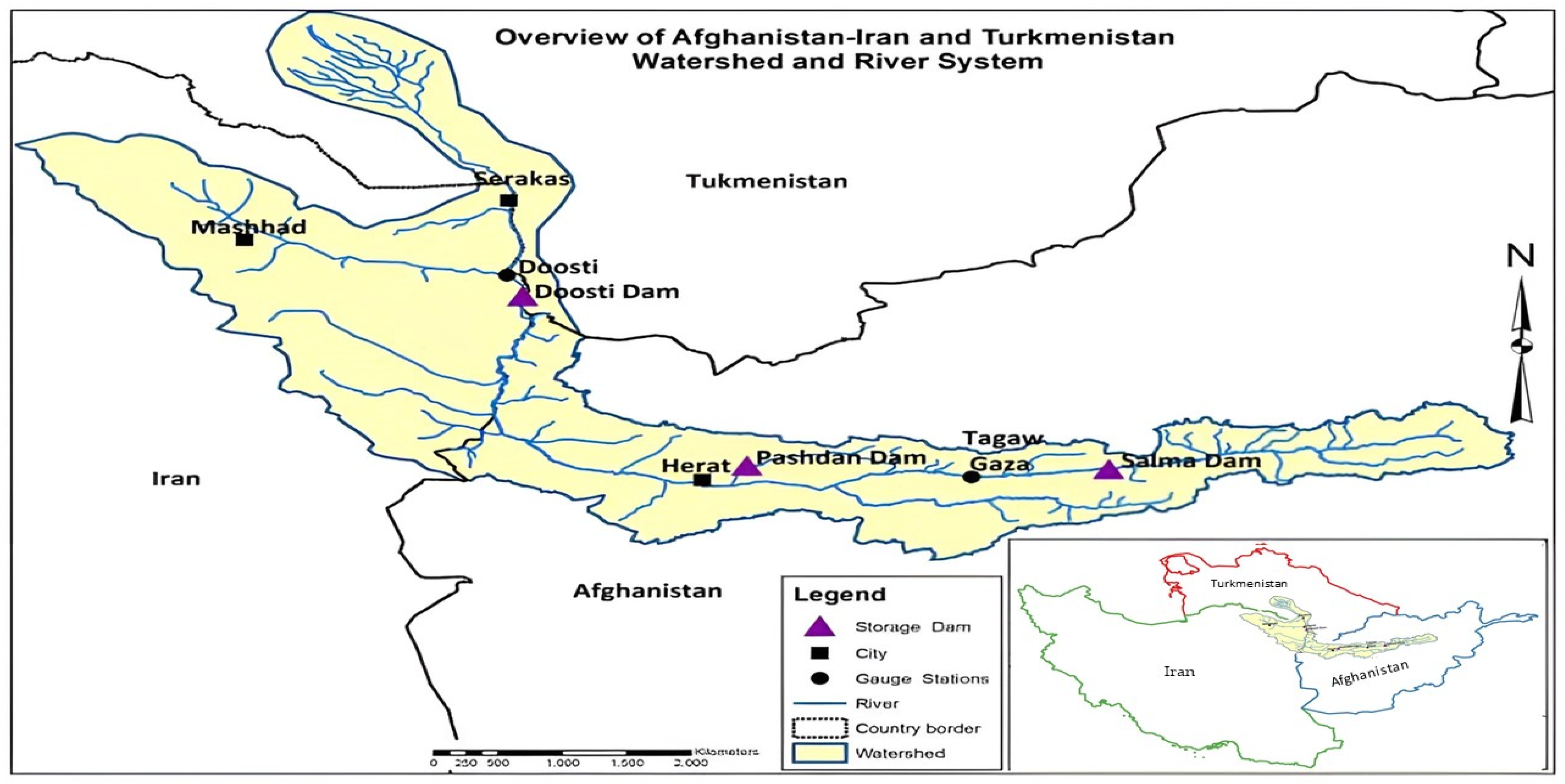

A visual map of the Harirud River Basin and its riparian territories (

Figure 3) complements this analytical structure. The map highlights how country and river basin boundaries simultaneously complicate benefit-sharing efforts and present new opportunities for coordination and cooperation. By synthesizing multiple data sources and theoretical perspectives, this methodology offers a comprehensive assessment of the complex socio-hydrological realities of the Harirud River Basin. It provides valuable insights into the pathways for addressing water scarcity, enhancing climate resilience, and promoting transboundary cooperation in a politically sensitive and environmentally vulnerable region.

3. Results

This study synthesizes findings from a qualitative case analysis of the Harirud River Basin, focusing on the hydro-political dynamics between Afghanistan and Iran, with partial relevance to Turkmenistan. The results identify clear patterns of hydro-climatic change, socio-economic dependence, and institutional asymmetry that influence transboundary water governance in the basin. Observed climatic indicators show reduced snowpack, earlier spring runoff, and higher evapotranspiration associated with rising temperatures [

15]. Both Afghanistan and Iran face increasing water stress and land degradation, with documented effects on food security and rural outmigration [

24].

The river plays a central role in regional water supply, irrigation, and energy production. Approximately 70% of agriculture in Herat Province depends on Harirud water [

25,

26]. In Iran’s Khorasan Razavi Province, the river supports agricultural and industrial activities through qanat systems and engineered diversions; in Turkmenistan, it contributes to oases irrigation and groundwater recharge. Studies of arid river systems show that persistent low-flow conditions increase pressure on water supply infrastructure as agricultural and domestic demands remain constant—patterns also observed in the Harirud Basin during extended dry seasons [

26]. Hydrologically, the basin exhibits upstream–downstream asymmetry: Afghanistan controls the headwaters but has limited institutional and infrastructural capacity, while Iran and Turkmenistan possess greater management and engineering capabilities yet depend on upstream releases [

27]. Several measurable constraints affect sustainable development in the basin. Water scarcity, hydrological variability, and groundwater over-extraction are documented across the riparian states [

28]. Institutional fragility in Afghanistan limits integrated management, while decentralised water governance in Iran contributes to uneven implementation capacity [

29]. The literature also identifies the absence of a formal transboundary water-sharing agreement between Afghanistan and Iran, along with persistent gaps in data exchange and institutional coordination [

30]. Environmental degradation—including deforestation, declining water quality, and soil salinization—appears widely in regional assessments [

10]. Cross-border development planning remains inconsistent, and infrastructure projects are often uncoordinated [

31].

Climatic data show an increase of approximately 1.5 °C in mean temperature between 1980 and 2020, accompanied by a 20% reduction in winter precipitation, a 25–30% decrease in snowpack, and an estimated 29% decline in surface water resources [

15,

32]. Per capita water availability in western Afghanistan decreased from roughly 2500 m

3 in 1990 to under 1700 m

3 in 2020 [

33]. These shifts correspond with more frequent droughts, reduced snow storage, and greater variability in river discharge. Hydraulic development has expanded on all sides of the basin. Afghanistan’s major projects—including the Salma Dam and the under-construction Pashdan Dam—aim to increase irrigation and hydropower capacity [

34]. Downstream, the Doosti Dam ( Construction completed 2004) serves Iran and Turkmenistan for storage and irrigation [

35,

36]. Reports indicate that the Doosti reservoir approached dead storage levels in 2023 due to low inflows from Afghanistan [

37]. Legally, the Harirud remains outside any binding bilateral or multilateral treaty framework. Existing arrangements consist of ad hoc memoranda, and none of the riparian states has fully ratified or operationalised global water conventions, such as the UN Watercourses Convention (1997) or the International Law Association’s 1966 Draft Articles on Transboundary Aquifers [

38,

39].

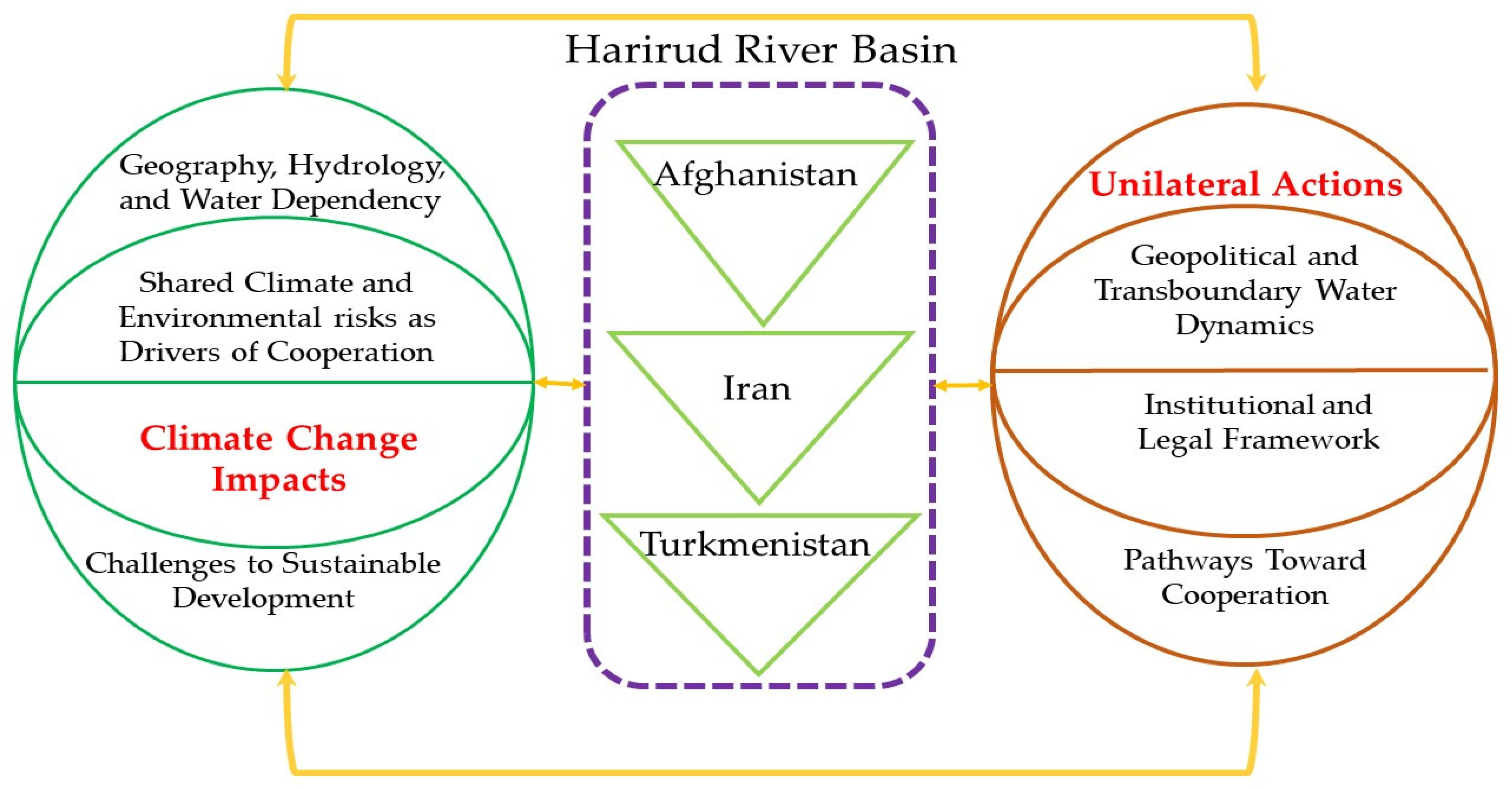

Overall, the results indicate measurable changes in precipitation, runoff patterns, and seasonal flow distribution in the Harirud River Basin between 1980 and 2022. The data also show changes in flow timing associated with upstream water infrastructure, along with increases in water demand due to population and land-use change. Institutional documents further reveal variability in basin-level coordination. These empirical patterns form the basis for interpreting broader climatic, governance, and political processes, which are examined in the subsequent discussion. To better capture how these natural and political factors interact across the shared basin, a conceptual framework is provided in

Figure 4.

4. Discussion

Building on the empirical results, this discussion interprets how climate change, unilateral water development, and governance constraints collectively shape the evolving hydrological and political landscape of the Harirud River Basin. The findings demonstrate that rising temperatures, declining precipitation, and altered runoff regimes—reinforced by uncoordinated dam construction—are transforming the basin’s flow dynamics and exacerbating downstream uncertainty. These pressures are further intensified by limited institutional capacity, fragmented planning, and demographic growth, creating a multilayered vulnerability that mirrors patterns identified in broader transboundary river literature. Situating these outcomes within historical trajectories and regional realities, the discussion examines the interconnected geographic, socio-political, and legal-institutional drivers that structure hydro-political relations between Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkmenistan. This integrated analysis highlights not only the systemic risks associated with current approaches but also the potential for cooperative frameworks, benefit-sharing mechanisms, and climate-adaptation strategies to realign the basin toward more sustainable and equitable water governance.

4.1. Geography, Hydrology, and Water Dependency

Afghanistan’s hydrology is organized around five major river basins: the Amu Darya, Harirud–Murghab, Helmand, Kabul, and Northern Basin, most of which originate in the Hindu Kush and Pamir mountains and are snow-fed, exhibiting strong seasonal flow variability [

35]. The Amu Darya, Helmand, Kabul, and Harirud basins are transboundary systems, linking Afghanistan hydrologically with Iran, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan [

40]. The Harirud River Basin covers about 112,200 km

2, shared among Iran (44%), Afghanistan (35%), and Turkmenistan (21%), each with distinct hydrological and infrastructural capacities [

19,

41]. Major dams include Afghanistan’s Salma Dam (2016, 650 MCM; 42 MW), Iran’s Doosti Dam (construction completed 2004, 1225 MCM), and several smaller facilities in Turkmenistan [

36,

37,

42]. Despite these infrastructures, Afghanistan utilizes only about 40% of its surface water, while Iran and Turkmenistan exploit nearly all available resources, often exceeding sustainable groundwater limits [

43].

Water is central to Afghanistan’s development. About 80% of the population depends on agriculture, which consumes 90% of national water resources, yet only 30% of potential water is effectively used due to weak infrastructure and governance [

44,

45]. With most farmland located within transboundary basins, agricultural productivity is increasingly threatened by upstream abstraction and climate variability [

46]. The sector contributes roughly 36% of GDP but contracted by 6.6% in 2022 following severe droughts [

47]. In the Harirud Basin, more than half of Herat’s farmland depends on the river for irrigation, making rural livelihoods highly water-dependent. Climate change has intensified risks such as droughts, floods, and shifting seasonal patterns, undermining agricultural reliability and deepening rural poverty [

32,

48]. Afghanistan’s overall reliance on seasonal rainfall and snowmelt has become increasingly unstable due to glacial retreat and early snowmelt [

49,

50].

In the energy sector, hydropower generates about 67% of Afghanistan’s electricity, yet only a small portion of the estimated 23,000 MW potential is developed [

51]. Rivers such as the Harirud, Helmand, and Kabul hold major potential for irrigation and energy expansion, but unilateral dam construction risks aggravating transboundary tensions with Iran and Turkmenistan. Overall, Afghanistan’s dependence on climate-sensitive and transboundary waters underscores a dual challenge: meeting domestic agricultural and energy needs while maintaining regional water cooperation. Strengthening IWRM, modernizing irrigation systems, and advancing joint hydropower initiatives under frameworks such as the UNECE Water Convention (2021) remain vital for long-term stability and resilience.

4.2. Shared Climate and Environmental Risks as Drivers of Cooperation

Findings from this study show that the Harirud River Basin is increasingly stressed by climate variability, declining water availability, and unilateral water use, all of which intensify hydrological imbalance and political tension among Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkmenistan. As shown in the results, warming and reduced precipitation have intensified hydrological imbalance. These basin-wide shifts confirm the study’s hydrological findings and demonstrate that climate change acts as a shared driver of vulnerability across all riparian states.

As discussed earlier, Afghanistan’s agriculture-based economy makes it highly sensitive to hydrological variability [

52]. Reduced snowmelt and erratic rainfall have led to crop losses, food insecurity, and rural displacement, undermining local stability [

53]. The findings link these effects to increased upstream abstraction through projects like the Salma Dam, which, while improving national irrigation and energy supply, further intensifies downstream stress [

54].

Iran’s groundwater depletion and reduced inflows exemplify how transboundary effects of climate variability manifest downstream. The collapse of water-dependent livelihoods has triggered mass rural-to-urban migration, further reflecting the basin-wide link between climatic decline and socio-economic stress [

55]. Turkmenistan, the downstream riparian, faces the compounded effects of reduced inflows, soil salinization, and inefficient irrigation, confirming the study’s finding that lower river discharge and outdated Soviet-era infrastructure constrain water reliability [

46,

56].

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that climate change and unilateral development are shared, quantifiable stressors driving ecological degradation, rural poverty, and political friction throughout the Harirud Basin. Declining flows and fragmented governance are already linked to the collapse of wetlands and rangelands and increasing dust storms in the Sarakhs–Badkhyz region [

57], and correspond to the study’s objectives, which emphasize the need to understand how climate change and unilateral actions jointly undermine sustainable and equitable governance in the Harirud Basin. Hence, the evidence underscores that addressing the basin’s environmental crisis requires cooperative governance mechanisms—including joint data sharing, equitable allocation, and adaptive planning—that align with the study’s broader goal of promoting climate-resilient and peaceful transboundary water management [

18,

58].

4.3. Climate Change Impacts

The Harirud River Basin faces growing vulnerability to climate change, with intensified droughts, shifting precipitation, and rising temperatures undermining agriculture, livelihoods, and water security. Despite differing national vulnerabilities, the riparians share interconnected risks that demand cooperative adaptation strategies. As reported in the results, climatic shifts across the basin have altered rainfall, snowmelt, and runoff, amplifying seasonal water stress. These basin-wide changes, have disrupted natural flow regimes and intensified hydro-political tensions among riparian states [

19,

59]. Recurrent droughts (e.g., 2011–2012, 2018–2019) and snowpack loss have undermined Afghanistan’s agricultural stability, depleting water reserves, reducing river flows, and causing widespread crop failures, particularly in rain-fed farming areas that support much of the rural population [

51,

52]. In Turkmenistan, outdated irrigation and reduced inflows reinforce systemic water insecurity [

56,

60].

Rising temperatures, altered precipitation, and increasing water variability are severely impacting agriculture, food security, and rural livelihoods across the Harirud Basin. In Afghanistan, where most people depend on agriculture, climate-induced water stress has devastated crop yields and pasture quality, driving displacement, poverty, and humanitarian dependence. Since 2021, weakened governance and limited capacity have intensified droughts and floods, further undermining productivity and disproportionately affecting women, children, and displaced communities [

22,

61]. The absence of coherent policy frameworks and limited international engagement has hindered long-term water planning and infrastructure maintenance [

10], intensifying water scarcity and raising regional tensions in shared basins like the Helmand and Harirud, where unilateral actions impede cooperative governance [

41].

Between 2001 and 2021, Afghanistan’s water sector struggled with institutional fragility, corruption, and limited technical capacity. Despite substantial international aid, major infrastructure projects suffered from mismanagement, while frameworks such as the 2009 Water Law were inconsistently applied [

25,

41,

43]. Corruption and weak governance eroded donor confidence and left rural communities—dependent on traditional karez and canal systems—highly vulnerable to water scarcity and climate stress [

46,

52]. Observations from the Harirud River at Pul-e-Malan in Herat [

62] indicate a sharp decline in water quantity, with pronounced seasonal fluctuations—spring floods and summer-autumn shortages—reflecting the basin’s worsening hydrological imbalance.

Figure 5 highlights the stark seasonal contrasts in river flow—from intense spring flooding to severe summer and autumn scarcity.

In Iran, agriculture consumes over 90% of available freshwater, yet the sector is facing declining yields due to water shortages, soil salinity, and heat stress. The abandonment of over 12,000 villages between 2002 and 2017 reflects the profound socio-economic effects of unsustainable water use and climate vulnerability [

55]. Ecosystems have also suffered: wetland degradation, including in the Sarakhs region, has disrupted biodiversity and increased the frequency of dust storms, which have adverse health and economic consequences [

57]. Turkmenistan’s land degradation and lack of adaptive investment mirror regional governance gaps [

46]. Ecologically, the basin’s terminal wetlands and riparian zones are shrinking, contributing to biodiversity loss and habitat fragmentation [

57,

60].

Intensifying temperature rise, increasing precipitation variability, and recurrent droughts are reshaping agricultural systems, rural livelihoods, and ecological integrity across the Harirud Basin. The compounded nature of these impacts—intertwined with political fragility, outdated infrastructure, and unilateral development—demands coordinated and cooperative adaptation strategies. Without a basin-wide climate resilience framework, the region faces the risk of escalating environmental collapse, food insecurity, and socio-political instability. Conversely, joint action through climate-resilient agriculture, sustainable water use, and environmental restoration can provide a foundation for mutual benefit and long-term sustainability. These results inform Research Question (c) by illustrating the ways in which documented climatic shifts—particularly temperature increases, changing precipitation patterns, and more frequent droughts—are associated with changes in the basin’s hydrology and seasonal flow dynamics. By linking environmental degradation with political fragility, the results demonstrate that adaptive, cooperative frameworks are essential to prevent further destabilization of transboundary relations.

4.4. Challenges to Sustainable Development

The Harirud River exemplifies the complexity of sustainable development in transboundary basins, where ecological stress, socio-economic dependency, and institutional weakness intersect with political mistrust and unilateralism. Although it holds considerable potential for cooperation, these interrelated challenges have instead made it a focal point of hydro-political tensions rather than a foundation for regional stability and development [

41].

The Harirud Basin faces compounded sustainability challenges arising from ecological fragility, water scarcity, and competing transboundary demands. Climate-driven shifts in precipitation, rising temperatures, and more frequent droughts have reduced and destabilised surface flows, heightening vulnerability in downstream regions such as Iran’s Khorasan Razavi Province [

37]. Environmental degradation—including deforestation, land misuse, and inefficient irrigation in Afghanistan—further weakens soil stability and natural water retention, undermining basin-wide ecological integrity [

52]. Across Iran and Turkmenistan, intensive irrigation and groundwater extraction have accelerated salinisation, desertification, and dust storm formation, producing substantial socio-economic and health impacts [

55]. Taken together, these pressures show how climate stress, land degradation, and intensified resource competition jointly threaten long-term sustainable development in the Harirud Basin. In a region already prone to extreme droughts, climate change is amplifying these pressures by intensifying variability and reducing predictability of river flows. As a result, competition over the limited and fluctuating resources of the Harirud is becoming increasingly acute, heightening the risk of zero-sum thinking and unilateral exploitation [

19].

Beyond ecological constraints, socio-economic conditions in the riparian states add further complexity. Afghanistan, with over 80% of its population dependent on agriculture, views the Harirud as essential for food security, livelihoods, and rural development. Projects such as the Salma and Pashdan dams are part of Kabul’s efforts to stabilise its agricultural economy and enhance energy production. Conversely, Iran relies on the river to secure drinking water for the rapidly growing city of Mashhad and for agricultural irrigation in Khorasan Razavi Province [

63]. The competing demands of population growth, displacement, and urbanisation in both countries place unsustainable pressure on water resources. Moreover, the Doosti Dam, jointly built by Iran and Turkmenistan but without Afghanistan’s involvement, highlights the marginalisation of Kabul in regional water development and has reinforced perceptions of inequitable benefit-sharing [

19]. Water disputes along the Harirud cannot be understood in isolation from the broader political context between Afghanistan and Iran. Recent years have seen the forced deportation of large numbers of Afghan refugees by Iran, over 1.1 million between March and July 2025 alone—deepening bilateral mistrust and fueling grievances [

64]. These deportations intersect directly with water politics, as both states increasingly use migration and water as instruments of leverage in broader negotiations. The result is a dangerous securitization of transboundary issues, where humanitarian crises, resource scarcity, and political rivalry reinforce one another. Such dynamics undermine the prospects for cooperative water governance, echoing Gleick’s [

65] observation that water disputes in fragile regions are often exacerbated by wider political instability.

Another major challenge is the lack of a binding institutional and legal framework for the Harirud River. Unlike the Helmand River, which is at least partially governed by the 1973 Helmand Water Treaty, the Harirud remains unmanaged by any formal bilateral or multilateral agreement. This absence of regulation has allowed unilateral dam construction and groundwater extraction to flourish unchecked. Afghanistan has invested in upstream infrastructure such as the Salma and Pashdan dams, while Iran and Turkmenistan have constructed the Doosti Dam and developed extensive well networks without Afghan consent [

66]. Both states invoke international law selectively to justify their positions: Afghanistan emphasizes sovereignty and its right to develop upstream resources, whereas Iran stresses the principle of “no significant harm” to downstream users [

40]. Without a joint monitoring mechanism, data-sharing platform, or basin organisation, transparency is limited and mistrust deepens, reinforcing the perception of inequitable and contested water use [

66]. At the heart of the Harirud dispute lies the structural imbalance of power between Afghanistan and Iran. As the weaker riparian, Afghanistan struggles to assert its sovereign rights in the face of Iran’s stronger economic, political, and infrastructural capacity. Tehran’s ability to combine downstream water needs with broader instruments of influence—including refugee policy, trade relations, and regional alliances—gives it a form of hydro-hegemony over Kabul [

42]. This asymmetry creates a political environment in which cooperative solutions are obstructed by mistrust. Afghanistan accuses Iran of overexploitation and obstruction of its dam projects, while Iran portrays Afghan actions as destabilizer to its downstream security. In this context, the absence of dialogue and joint institutions perpetuates a cycle of suspicion and rivalry, rather than opening pathways toward benefit-sharing and sustainable transboundary governance [

22].

Figure 6 illustrates the interlinked challenges to sustainable development in the Harirud River Basin, including ecological fragility (climate change, salinization, desertification), water overuse (irrigation and groundwater extraction), socio-economic pressures (population growth and displacement), political tensions (refugee deportations and mistrust), and weak governance (absence of a treaty and unilateral actions)—all compounding water scarcity and institutional fragility. Together, these challenges transform the river from a potential engine of cooperation into a flashpoint of conflict. Addressing them requires more than technical water management; it demands embedding bilateral relations within the principles of international water law, strengthening institutional capacity, and creating cooperative mechanisms for benefit-sharing. Without such measures, the Harirud will remain less a source of shared prosperity and more a symbol of missed opportunities and deepening mistrust between Afghanistan and Iran.

4.5. Unilateral Actions

Findings from this study demonstrate that hydro-hegemony in the Harirud Basin is not static but produced through unilateral actions, weak governance, and unequal power relations among the riparian states. The basin illustrates how competing national agendas—rather than collective management—have fragmented cooperation, degraded ecosystems, and deepened social vulnerability. All riparians pursue unilateral control strategies, as evidenced by downstream exclusion in the Doosti Dam (2004) and upstream responses through Afghanistan’s Salma and Pashdan projects [

66]. Yet, findings show that these upstream interventions have altered seasonal flow patterns, reducing downstream reliability and intensifying Iran’s perception of hydrological insecurity [

38].

As shown in R1, declining precipitation and flow variability amplify this competition. Actor interviews and policy documents reveal that Iranian officials frame Afghanistan’s dam projects as violations of “customary water rights,” while Afghan authorities emphasize their sovereign entitlement to use domestic resources for food and energy security. These narratives illustrate discursive hydro-hegemony, where control over language and legitimacy reinforces material dominance [

18]. The research also found that unilateral water projects and migrant dynamics are closely interlinked. Following drought and declining agricultural productivity, rural out-migration from Herat and Ghor has surged, while Iran’s mass deportations of Afghan migrants—over one million in 2025—have overwhelmed border provinces already facing water scarcity and economic fragility [

67]. These conditions create a feedback loop: water scarcity drives migration, and migration policies are then used as leverage in water negotiations, reinforcing asymmetrical power structures.

This analysis supports the study’s broader finding that the absence of institutionalized cooperation and data-sharing mechanisms has entrenched a pattern of competitive unilateralism rather than collective adaptation. Both upstream and downstream actors justify their actions as defensive responses to the other’s initiatives, illustrating the cyclical reproduction of hydro-hegemony. As the study’s results show, the failure to establish a trilateral governance framework perpetuates environmental degradation, erodes trust, and hinders progress toward SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions). This outcome directly relates to the study’s objective of evaluating how weak institutional cooperation and unilateral actions undermine sustainable and equitable transboundary water governance. It also situates the Harirud case within global policy efforts promoting cooperative, inclusive, and climate-resilient water management.

In this context, hydro-hegemony is not merely a theoretical lens but a lived reality—manifested through unequal control over infrastructure, narrative framing, and population mobility. Addressing it requires strengthening transboundary institutions, embedding climate adaptation in basin planning, and promoting mutual data transparency as a foundation for equitable cooperation and shared resilience. This subsection directly responds to Research Question (b) by demonstrating that unilateral water projects in Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkmenistan have transformed hydrological interdependence into political asymmetry. The analysis confirms that uncoordinated dam construction and competing national agendas erode trust and hinder equitable, sustainable water use across the basin.

4.6. Geopolitical and Transboundary Water Dynamics

Afghanistan occupies a strategically pivotal hydrological nexus in South and Central Asia, sharing five major transboundary river systems: the Harirud and Murghab rivers shared with Iran and Turkmenistan, the Amu Darya (with Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan), the Kabul–Kunar system shared with Pakistan and the Helmand (with Iran). Collectively, these rivers underpin both Afghanistan’s water security and the broader stability of the region; furthermore, over 80% of the country’s freshwater originates from these transboundary basins, making cooperative management essential [

68]. However, Afghanistan’s upstream position has not translated into sustained hydro-hegemonic influence due to weak institutions, protracted conflict, and limited technical capacity [

6]. The Harirud Basin demonstrates the multifaceted nature of these dynamics. Downstream infrastructure such as the Iran–Turkmenistan Doosti (Friendship) Dam—constructed in the early 2000s without Afghan participation—set a precedent for exclusionary basin governance, consolidating downstream control and marginalizing Afghanistan in decision-making [

69]. Afghanistan, a country in urgent need of agricultural development, sought funding from India for upstream projects such as the Salma and Pashdan dams, which were framed as essential for post-war reconstruction, irrigation, and energy supply. While these projects address domestic needs and support vulnerable farmers, they have also raised concerns about reduced water availability downstream [

19].

The absence of a comprehensive trilateral water-sharing framework, unlike the 1973 Helmand River Treaty, which is inconsistently implemented, has left the Harirud governed by fragmented legal norms and contested interpretations of customary international water law, particularly regarding benefit-sharing and cooperative utilisation [

70]. These governance deficits are exacerbated by significant data and technical asymmetries, reflected in limited joint monitoring, scarce hydrological data sharing, and uneven institutional capacity, all of which impede evidence-based allocation and confidence-building [

71]. Climate change is exacerbating these risks, accelerating glacier retreat, altering snowmelt regimes, and increasing hydrological variability, which reduces flow predictability and amplifies the socio-economic and ecological consequences of infrastructure development [

72,

73]. Water scarcity in border areas has also contributed to rising tensions; human rights organizations and local media have reported incidents of violence against Afghan civilians by Iranian border guards, including shootings over access to drinking water from the Harirud River [

73]. In 2024–2025, Iran’s mass expulsions of Afghan nationals coincided with heightened water disputes, creating humanitarian pressures in ecologically stressed provinces such as Herat and further politicizing bilateral relations [

64].

Similar patterns emerge in Afghanistan’s other transboundary basins. The 1973 Helmand River Treaty remains Afghanistan’s only water-sharing pact with Iran, but its uneven implementation has fueled tensions, particularly after Afghanistan’s president highlighted water’s geopolitical role during the 2021 inauguration of the Kamal Khan Dam [

74]. This dynamic reflects a broader pattern of using transboundary water as political leverage, akin to Türkiye’s manipulation of the Euphrates via the Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP)—notably during the filling of the Atatürk Dam—which significantly disrupted downstream water availability [

75]. Unlike countries that might weaponize water in high-level negotiations, Afghanistan’s ability to use water as leverage in the Harirud Basin is severely constrained by domestic political instability, which hampers effective resource management, and recurrent floods and droughts that annually exact a heavy toll on lives and infrastructure [

76]. Furthermore, neighboring countries frequently exert pressure on Afghanistan to limit upstream development, complicating transboundary water dynamics even further. While such strategies may compel regional engagement, they also heighten the risk of escalation and undermine long-term cooperation. A more sustainable approach would integrate migration management, climate adaptation, and water governance, aligning with recommendations from the International Organization for Migration to address underlying socio-economic drivers through bilateral agreements, reintegration programs, and vocational training [

49].

Afghanistan’s recent accession to the UNECE Water Convention in 2021 marks a notable step toward aligning with international norms on equitable and sustainable water management [

77]. This provides a normative and practical platform for institutionalising cooperation through mechanisms such as joint monitoring, shared databases, environmental impact assessments, and adaptive allocation rules responsive to climatic variability [

70,

71]. Ultimately, basin stability depends on transitioning from unilateralism to legally grounded, transparent cooperation, supported by confidence-building measures and integrated humanitarian considerations to mitigate the securitisation of water and migration. The political will of riparian states, backed by sustained multilateral facilitation, will be decisive in transforming these frameworks into enforceable, locally legitimate institutions. In relation to Research Question (a), this analysis highlights that the Harirud River’s geopolitical importance stems from its dual role as a source of both strategic leverage and potential cooperation. The basin exemplifies how asymmetrical power, migration pressures, and regional isolation intersect to shape Afghanistan–Iran relations, reinforcing the need for legal and institutional frameworks that transform hydro-politics into collaboration rather than conflict.

4.7. Institutional and Legal Framework

The Harirud River Basin lacks a binding, basin-wide legal and institutional framework, leaving Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkmenistan without mechanisms to coordinate water use, resolve disputes, or manage shared risks. This absence has fostered unilateral actions, weakened ecological resilience, and deepened mistrust—contradicting the study’s findings that cooperative, data-based governance is key to sustainable management. Current arrangements remain fragmented. The Doosti Dam, constructed by Iran and Turkmenistan without Afghan participation, and Afghanistan’s Salma and Pashdan Dams, implemented without regional consultation, highlight the absence of legal procedures for prior notification, environmental impact assessment, and equitable allocation [

18,

44]. Each riparian interprets sovereignty and water rights in isolation, undermining basin-wide sustainability.

To bridge these gaps, the riparians should pursue a legally binding trilateral agreement anchored in the principles of equitable and reasonable use, no significant harm, and the duty to cooperate, adapted to the Harirud’s specific hydro-political realities. The establishment of a Joint River Basin Commission would institutionalize cooperation through shared monitoring, conflict resolution, and transparent data exchange. Applying the principles of IWRM is essential. IWRM emphasizes the coordinated use of water, land, and related resources to maximize socio-economic welfare without degrading ecosystems [

78]. In the Harirud context, this means aligning irrigation, hydropower, and groundwater management under one basin strategy; integrating climate adaptation, ecosystem protection, and benefit-sharing mechanisms; and involving local stakeholders—particularly farmers, women, and displaced communities—in planning and monitoring.

Regional and international platforms can play a vital role in supporting basin-wide cooperation. Afghanistan’s participation in frameworks like the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO) and the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) underscores the potential for multilateral engagement. Neutral actors such as the UN, World Bank, or OSCE can provide mediation, technical assistance, and capacity building to address asymmetries between riparian [

77]. Afghanistan’s evolving national water governance framework provides an essential legal basis for managing the Harirud River Basin, yet implementation remains weak. The Water Law (2009) recognizes water as a public good and calls for integrated basin-level management, which—if operationalized—could guide coordinated planning with Iran and Turkmenistan. The National Water Policy (2010) and the Afghanistan National Peace and Development Framework II (2021–2025) emphasize infrastructure development and transboundary cooperation, both directly relevant to balancing upstream irrigation and hydropower expansion in Herat with downstream needs [

79]. Likewise, the Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan (2016) identifies the Harirud as highly vulnerable, urging climate-resilient basin management [

14].

However, this study finds that these national policies have had limited practical impact on the Harirud due to institutional fragmentation, poor data exchange, and lack of enforcement. Translating these frameworks into basin-level governance would require a joint, legally binding mechanism aligned with IWRM principles, integrating hydrological monitoring, climate adaptation, and equitable benefit-sharing. Only through such application can national reforms contribute meaningfully to regional cooperation and sustainable development in the Harirud Basin. These insights contribute to Research Question (b) by emphasizing that the absence of a binding transboundary framework perpetuates unilateralism and undermines sustainable governance. A joint river basin mechanism grounded in equitable use, no-harm, and cooperation principles emerges as a practical pathway toward regional stability and shared benefit.

4.8. Pathways Toward Cooperation

Current geopolitical dynamics in the Harirud Basin markedly exacerbate uncertainty and complicate pathways toward cooperative water management. Iran, in particular, faces deep political and economic pressures—from international sanctions to regional conflicts such as the war in Gaza and broader Middle East tensions—that distract decision-makers from transboundary water diplomacy. On the other hand, Afghanistan finds itself in even deeper isolation and political limbo; from 2021 until mid-2025, no state formally recognized the Taliban government, with Russia’s recognition on 3 July 2025 marking the first reversal in that trend [

80]. Concurrently, the country grapples with crippling poverty and widespread displacement, with over 80% of its population living below the poverty line [

24,

81] and a majority caught in the destructive cycles of migration and state invisibility. Turkmenistan remains relatively stable in comparison, yet its central government rarely demonstrates a proactive appetite for cooperative dialogue.

Despite significant geopolitical, institutional, and environmental challenges in the Harirud River Basin, several strategic pathways offer strong potential for enhancing transboundary cooperation among Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkmenistan. A key starting point is the revitalization of diplomatic dialogue via existing bilateral and trilateral platforms, and ultimately institutionalizing cooperation under regional—if not global—frameworks such as the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO), UN-ESCAP, or the newly launched UN-Water Transboundary Water Cooperation Coalition. This global coalition, launched in 2022, encourages countries sharing cross-border water to make concrete cooperation commitments to foster peace and sustainable development—an approach that could serve as a model for Harirud basin states [

82].

Another foundational measure is establishing joint hydrological monitoring systems and transparent data-sharing protocols, which build trust and enable coordinated planning. Such confidence-building mechanisms are widely recognized as critical in transboundary basin cooperation [

16,

55,

83]. Equally vital is the adoption of equitable benefit-sharing arrangements that extend beyond volumetric water division to include shared returns from hydropower generation, agricultural productivity, flood control, and ecological protection. These positive-sum frameworks help reframe water sharing from zero-sum competition into collaborative gain, aligning with evolving international practice [

71].

Neutral third-party facilitation—from UN entities, development banks, or impartial states—can also play a catalytic role by mediating disputes, providing technical support, and enabling institutional innovation. This aligns with global practice where international mediation has helped bridge gaps in transboundary water governance [

78]. Building for future uncertainty, legal and institutional provisions should be adaptive and flexible—able to respond effectively to climate change impacts and hydrological variability, following the principles of IWRM. IWRM emphasizes sustainable multifunctional management of water resources, incorporating flexibility, local participation, and environmental integrity [

72].

Complementing these approaches, developing transparent legal pathways grounded in international conventions (such as the UN Watercourses Convention) and tailored regional norms will provide legal legitimacy. Equally important is capacity building for Afghan institutions to engage effectively in negotiations and basin governance. In summary, a multi-tiered cooperation strategy combining regional institutionalization, data transparency, benefit-sharing, adaptive legal design, and capacity support can transform the Harirud from a site of dispute into a platform for sustainable regional collaboration and resilience.

As a comparative insight we can say that the Harirud River Basin shares several features with other transboundary basins such as the Helmand, Euphrates–Tigris, Nile, and Indus. Like the Helmand River, it reflects asymmetric power relations and the absence of a binding treaty, which foster unilateral development and recurring downstream grievances [

55]. Similarly to the Euphrates–Tigris and Indus systems, hydropolitics in the Harirud are shaped by infrastructure-driven competition and securitization of water, where dam construction substitutes for cooperation [

6]. However, unlike these larger and institutionally engaged basins, the Harirud remains marginalized in regional diplomacy and lacks an active joint management body or data-sharing mechanism, which intensifies mistrust. In contrast to the Nile Basin, where cooperative institutions such as the Nile Basin Initiative have created a dialogue platform despite political tensions [

84,

85], the Harirud still operates in a legal vacuum with minimal third-party facilitation.

This study thus positions the Harirud as a microcosm of wider transboundary challenges—where climate stress, governance asymmetry, and geopolitical rivalries converge—but also as a potential testing ground for integrated water governance and IWRM-based cooperation in fragile regions. This subsection synthesizes responses to all three research questions. It shows that effective transboundary governance in the Harirud Basin requires integrating climate adaptation, institutional reform, and geopolitical engagement. By linking environmental security with cooperative water management, the findings underline that sustainable governance is both a hydrological necessity and a foundation for long-term peace between Afghanistan and its neighbors.

5. Conclusions

The Harirud River Basin exemplifies how climate change, unilateral development, and weak governance converge to shape transboundary water relations among Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkmenistan. This study’s integrated hydrological and qualitative analysis reveals that sustainable management of the basin depends on coordinated action across ecological, political, and institutional dimensions. (a) Geopolitical and economic significance: The findings confirm that the Harirud is not merely a hydrological system but a strategic resource shaping Afghanistan–Iran relations. Its waters underpin agriculture, hydropower, and urban supply, linking food and energy security with regional stability. However, asymmetric power relations and the absence of a binding agreement have allowed political and economic tensions to overshadow cooperative opportunities. (b) Unilateral interventions and governance: Policy analysis indicates that unilateral infrastructure projects—Afghanistan’s Salma and Pashdan Dams, and Iran’s Doosti Dam and groundwater diversions—have entrenched zero-sum perceptions and weakened trust. Both sides invoke sovereignty and security narratives, yet the lack of joint data-sharing or prior notification mechanisms has magnified downstream scarcity and regional mistrust. These findings show that unilateral action undermines equitable and sustainable water use across the basin. (c) Climate change and adaptive strategies: Hydrological data (1980–2020) reveal a 1.5 °C rise in mean annual temperature, a 20% decline in winter precipitation, and a 29% reduction in surface water availability—equivalent to a loss of about 0.98 billion m3. These changes have reduced snowpack and seasonal runoff, intensifying water scarcity and competition. The impacts extend beyond the environment: water stress drives agricultural losses, rural poverty, and cross-border migration, as seen in Iran’s deportation of over one million Afghan migrants in 2025.

The combined effects of climate variability and unilateral decision-making are the principal threats to the basin’s sustainability, disrupting both the physical flow of water and the institutional foundations of cooperation. To ensure long-term resilience, management must shift from unilateral, project-based control to joint, adaptive governance rooted in IWRM and aligned with the UN Watercourses Convention. A trilateral framework—featuring a Joint River Basin Commission, shared hydrological monitoring, and transparent data exchange—would enable equitable benefit-sharing and strengthen climate adaptation. In essence, the Harirud Basin can either remain a locus of hydro-political asymmetry or evolve into a model of cooperative, sustainable peace. Achieving the latter depends on translating evidence-based insights into binding legal commitments, shared adaptation strategies, and trust-building measures that bridge science, policy, and diplomacy.

This study advances both geoscience and hydro-political scholarship by integrating hydrological trend analysis with institutional and governance assessment in an under-researched transboundary basin. It provides new evidence of climate-induced hydrological decline in the Harirud—showing a 1.5 °C temperature rise, 20% drop in precipitation, and 29% surface water loss—and links these physical shifts to unilateral actions, governance asymmetry, and migration pressures. Conceptually, it extends hydro-hegemony and IWRM frameworks to a fragile, data-scarce context, addressing a key gap in Central and Southwest Asian water studies by demonstrating how climatic and institutional fragility together shape transboundary water governance and regional sustainability.