Abstract

This work presents a new 1:10,000-scale geological map of the Frasassi area (central Italy), integrating recent surface and cave surveys. The map is complemented by new data on the lithostratigraphic characterisation of the Calcare Massiccio Formation (MAS), which forms the core of the local Jurassic structural high. This refined analysis allows for a more detailed subdivision of the MAS and better correlation with the overlying condensed Jurassic succession (BU) and surrounding Maiolica Formation (MAI). The map documents the complex tectono-sedimentary contacts between these units, highlighting the geometry of the MAS–MAI boundary and the occurrence of neptunian dykes both at the surface and within the cave system. The proposed structural interpretation suggests that the Frasassi high was an elongated NW–SE block bounded by conjugate oblique-slip normal faults later reactivated during folding. The results refine the understanding of Jurassic paleogeography and post-Jurassic deformation in the northern Apennines and provide an updated framework to support future geological studies in the area.

1. Introduction

The Frasassi Gorge, a renowned Italian geosite and tourist destination, is best known for its show cave, which develops along a 500 m-deep, 2 km-long canyon incised by the Sentino River through an anticline ridge. The cave system is a classic example of hypogene speleogenesis ([1] and references therein). It extends for over 30 km on multiple levels formed during progressive valley deepening. Speleogenesis was driven by the oxidation of ascending sulfidic waters, a process known as sulphuric acid speleogenesis.

The gorge also provides an exceptional cross-section through the anticline, exposing the Umbria–Marche succession [2,3] from the Lower Jurassic carbonate platform at the core to the Miocene marlstones on the western limb. This succession accumulated along the passive continental margin of the western Tethys. Variations within the Jurassic pelagic deposits reflect contemporaneous extensional tectonics, which fragmented the platform into fault-bounded highs and intervening basins.

Detailed geological investigations of the Frasassi structure date back to the early 20th century, when the feasibility of an artificial lake was assessed to exploit the morphological constriction of the gorge. Fossa Mancini [4] produced a 1:50,000-scale geological map, derived from a 1:25,000 field survey, accompanied by an extensive series of geological cross-sections. He concluded that dam construction was unfeasible due to the high permeability of the karstified limestones. It can be noted that at that time the known extent of the cave system was only a few hundred metres.

More recently, Coltorti [5] produced a 1:25,000-scale map that includes the eastern sector of the study area, highlighting tectonic structures related to Jurassic extension and NE–SW faults interpreted as active and continuous across the entire area. Barchi et al. [6] examined the Frasassi structure alongside six other anticlines in the Northern Apennines to characterise fracture patterns in platform limestones forming anticline cores. Cello et al. [7] produced a 1:25,000-scale geological map and documented mesostructures associated with two extensional tectonic phases—Jurassic and Cretaceous–Oligocene—and with Neogene compression. They emphasised the role of pre-existing lithological heterogeneity, generated by Jurassic faulting, during subsequent thrusting. After the initial folding, some faults were partially reactivated, uplifting the Jurassic high relative to the adjacent basin, before being cross-cut by newly formed thrust faults.

Mariani et al. [8] investigated deposits on cave lake walls up to five metres above the present water table. Using 14C dating of eel remains and measurements of microcrystalline calcite rinds marking past water levels, they documented a ~4.5 m lowering of the water table over the last 8000 years. This was attributed entirely to tectonic uplift. The upper rinds were found to be markedly tilted (up to 0.21° ENE) relative to the present water table, a feature that the authors interpreted as evidence of rollback rotation due to Holocene reactivation of the hanging wall of a SW–dipping fault located ~6.5 km to the ENE. In addition to the maps provided in the cited studies, a revised 1:10,000-scale geological map of the area is available online [9].

In this paper, a new 1:10,000-scale geological map of the Frasassi area is presented and discussed, together with an updated stratigraphic framework based on decades of field investigations.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is based on a 1:10,000-scale geological survey, developed over several decades of work in the area, including research on the geology and genesis of the caves. Specific geological mapping was performed in three main phases.

The first phase, in 1988, focused on collecting structural attitude data used to model the fracture network of the Frasassi anticline [6]. The second phase, in 2020, involved detailed mapping of contacts along the eastern limb and extension of the survey to the southwestern sector. From 2023 onwards, marginal sectors were mapped and key sites and significant contacts were refined.

Fieldwork included the detailed analysis of the lithological characteristics of the formations, particularly the Jurassic units, and careful mapping of stratigraphic and tectonic contacts between them. Bedding, fault attitude, and kinematic indicators, where observable, were measured throughout the study area, including less accessible sectors. Although no statistical analysis was performed, most measurements are plotted on the geological map and were used to constrain fault geometries and the structure of the folds.

Early data were recorded manually, while from 2023 onwards, the PETEX FieldMove software (version 1.5.2) was used. All data were compiled on a 1:10,000 topographic base (Regione Marche), with contacts first drawn by hand, then digitised and vectorised using CorelDRAW 2024. The same dataset was used to construct geological cross-sections, spaced approximately 400 m apart, allowing estimation of formations thickness and fault throws. Three representative cross-sections were included in Figure S1.

Surface observations were integrated with information from deep sectors of the caves, at sites marked by stars on the geological map (Figure S1). Their position within the mountain structure was determined using pre-existing cave maps produced by speleological groups of the region. These surveys combined theodolite measurements and, more commonly, rapid compass-and-distance methods. Cave plans were georeferenced to the surface topography by aligning entrances with GPS coordinates. The overall positional uncertainty of structural features in the cave is estimated within ±10–20 m.

3. Geological Framework

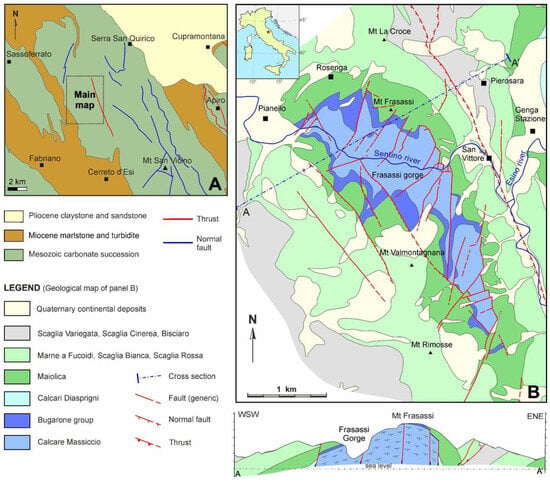

The study area (Figure 1) includes the minor Frasassi anticline and the Pierosara syncline, situated immediately west of the major Mt San Vicino anticlinorium. Its tectono-sedimentary evolution forms part of the broader geological history of the Apennine chain. A recent synthesis based on surveys for the 1:50,000-scale Foglio 302 Tolentino of the Geological Map of Italy [10] covers the adjacent area to the east.

Figure 1.

(A) Regional geological framework showing the location of the study area. (B) Simplified geological map of the Frasassi Gorge with accompanying cross-section. The complete geological map, including the full base map, cross-sections, and detailed lithostratigraphic information, is provided in Figure S1.

The tectonic evolution involved four main phases [11,12]: (i) Jurassic extension, which fragmented the Lower Jurassic carbonate platform into a mosaic of structural highs and basins; (ii) Cretaceous–Palaeogene extensional tectonics, producing thickness variations, slumps, and olistostromes; (iii) a late Miocene pre-orogenic extensional phase, forming chain-parallel basins filled with siliciclastic turbidites; (iv) a compressional phase, uplifting the chain and thrusting it eastwards over the Messinian Gessoso Solfifera Formation. During the final stages, erosion of the Miocene and even pre-Miocene substratum is evidenced by the presence of chaotic materials within the siliciclastic turbidites.

The set of normal faults at the core of the Mt San Vicino anticlinorium was attributed to Miocene extensional tectonics, based on cutoff angles and the lack of morphological evidence for recent movement [11,12]. These structures are therefore considered older than the post-thrust Pleistocene and Holocene activity previously proposed [13,14].

During the Jurassic, the tectonic evolution was accompanied by the differentiation of structural highs and intervening basins, each marked by distinct pelagic successions (Mesozoic stratigraphic scheme, Figure S1). The basinal domains consist predominantly of limestones with variable chert content and intercalated Toarcian marlstones, recording deposition from the Sinemurian onwards. The thickness exceeds 400 m and can reach over 1000 m in some sectors. Conversely, the structural highs are characterised by condensed pelagic successions dominated by limestones, which accumulated from the Pliensbachian onwards and range from a few metres to 40–50 m in thickness.

By the end of the Jurassic, depositional environments across the Umbria–Marche Basin became more uniform. Pelagic cherty limestones dominated until the Eocene, when the advancing Alpine orogen promoted increased terrigenous input.

4. Geological Setting of the Frasassi Area

The new 1:10,000-scale geological mapping integrates over 40 years of field observations, including investigations within the cave system. These data provide the basis for a detailed description of the local stratigraphy (Figure S1) and tectonic features, providing the basis for a refined reconstruction of the geological framework and structural evolution of the Frasassi anticline and its surroundings.

4.1. Stratigraphy

4.1.1. The Carbonate Platform

The Calcare Massiccio (MAS; Hettangian–Sinemurian) is exposed along the hinge zone of the anticline and within the gorge that cuts across its core (Figure 2). It is the oldest outcropping unit in the region and overlies a thick Upper Triassic evaporitic formation drilled in boreholes [15] (Mesozoic stratigraphic scheme, Figure S1). These evaporites are considered the source of the ascending sulfidic waters responsible for the development of the Frasassi cave system.

Figure 2.

Natural section through the core of the anticline on the northern side of the Frasassi Gorge, showing main faults, a neptunian dyke, and the stratigraphic boundaries of the MAS levels. (viewpoint from SSE: 43°23′54′′ N 12°57′34′′ E). Labels: i—basal cyclothemic level; ii—lower non-cyclothemic level; iii—upper cyclothemic level; iv—uppermost non-cyclothemic level.

Along the gorge’s steep slopes, the unit is exposed for more than 550 m without reaching its base, offering one of the most complete natural sections of the formation in the entire region. Four main lithofacies intervals can be distinguished based on facies associations.

- (i)

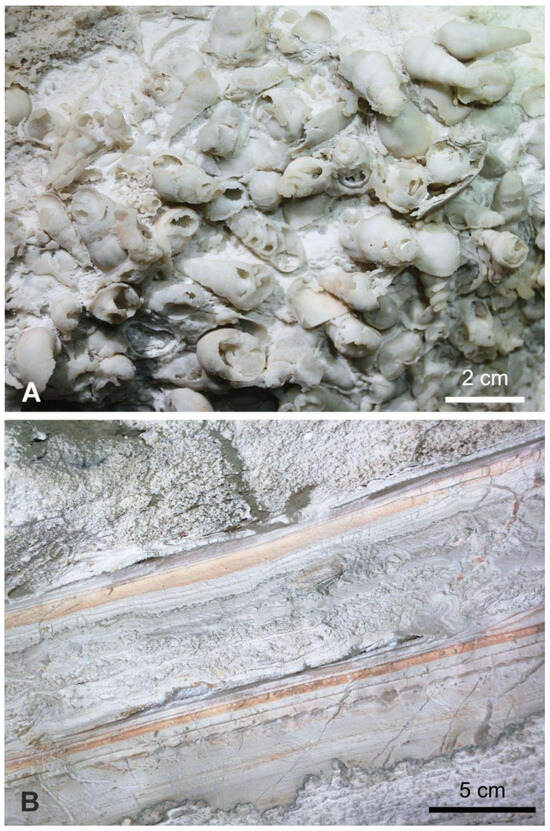

- The basal ~300 m displays the typical cyclothemic facies [16,17,18]. These consist mainly of regressive cycles in which up to 4 m of subtidal wackestone or packstone pass upward into one or more decimetre-thick beds of intertidal to supratidal facies. The subtidal facies are whitish to light hazel limestones with irregular porous systems and contain abundant peloids, algae, bioclasts, and scattered oncolites. Floatstone or rudstone levels, rich in oncolites or bioclasts, are common and interpreted as channel lag deposits (Figure 3A). The thin-bedded horizons are darker and display fenestral fabrics, algal mats, reddish micrites, sheet and prism cracks, and occasional vadose pisolites, although these are less common here than in other localities (Figure 3B and Figure 4A,B).

Figure 3. Typical structures from the cyclothemic MAS revealed by differential corrosion inside the caves. (A) Gastropod rudstone in the upper part of a subtidal thick bed. (B) Reddish micrite in a thin inter-supratidal layer.

Figure 3. Typical structures from the cyclothemic MAS revealed by differential corrosion inside the caves. (A) Gastropod rudstone in the upper part of a subtidal thick bed. (B) Reddish micrite in a thin inter-supratidal layer. Figure 4. Typical facies from the MAS, based on negative prints from dry peels (scale bar 1 cm). Cyclothemic MAS: (A) fenestral fabric; (B) sheet cracks and vadose pisolite, both from inter-supratidal layers, with stylolitic surfaces. Non-cyclothemic MAS: (C) well-sorted, fine-grained deposits; (D) grainstone with micritised ooids.

Figure 4. Typical facies from the MAS, based on negative prints from dry peels (scale bar 1 cm). Cyclothemic MAS: (A) fenestral fabric; (B) sheet cracks and vadose pisolite, both from inter-supratidal layers, with stylolitic surfaces. Non-cyclothemic MAS: (C) well-sorted, fine-grained deposits; (D) grainstone with micritised ooids. - (ii)

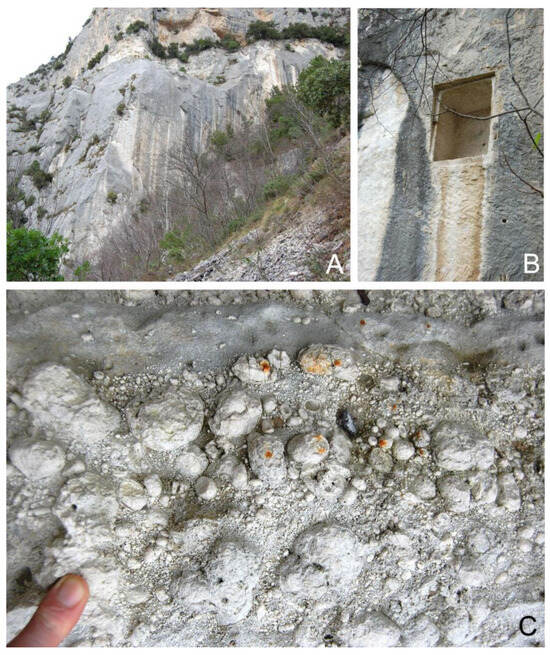

- These cyclothemic facies are followed by a 40–50 m thick, massive unit composed of well-sorted, fine-grained limestones, with low micrite content and open pore spaces only partially filled by syntaxial cement (Figure 4C,D and Figure 5A,B). In addition to this dominant lithology, levels of poorly cemented grainstone with fossils and oncolites are also present, while intertidal–supratidal facies are absent (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Outcrop images from the lower non-cyclothemic MAS level (ii) (location: 43°24′13″ N, 12°57′13″ E). (A) A thick, massive level of fine-grained materials. (B) Remnants of historical carving activity on the rock surface. (C) A poorly cemented grainstone bed rich in oncolites, highlighted by fine grains crumbling away.

Figure 5. Outcrop images from the lower non-cyclothemic MAS level (ii) (location: 43°24′13″ N, 12°57′13″ E). (A) A thick, massive level of fine-grained materials. (B) Remnants of historical carving activity on the rock surface. (C) A poorly cemented grainstone bed rich in oncolites, highlighted by fine grains crumbling away.

The homogeneous texture and ease of carving explain its long-standing use as a building and ornamental stone in public and religious buildings since Roman times and throughout the Middle Ages (Figure 5B). Poorly cemented horizons have promoted the formation of a prominent ledge along the gorge, where numerous superficial caves developed due to the crumbling of limestone caused by weathering processes (Figure 2).

- (iii)

- The overlying ~150 m thick interval shows a return to cyclothemic facies, here dominated by subtidal deposits containing two distinctive Megalodon-bearing horizons [19]. Intertidal–supratidal events occur but are only weakly developed.

- (iv)

- The uppermost ~60 m consist mainly of poorly cemented, well-sorted fine-grained limestones, similar to those in unit (ii), together with well-sorted oolitic grainstones (Figure 4D) and micrite-rich beds. Oncolites are rare and there is no evidence of prolonged subaerial exposure. This interval corresponds to the Calcare Massiccio B [20,21], and to the “oolitic bar” of [22], who attributed the fine-grained facies to a back-bar environment. It has been interpreted both as a residual platform deposit preserved on horst tops generated by Jurassic tectonics [20] and as part of a drowning succession in the footwalls of Jurassic faults [23].

In the study area, the permanently subtidal facies of the Calcare Massiccio (MASa [21]), which typify deeper depositional zones in the hanging walls of Jurassic faults, are not exposed.

4.1.2. Bugarone Group

The pelagic deposits overlying the Calcare Massiccio in the Frasassi anticline are represented by a condensed succession. This succession may comprise up to five units, collectively mapped as the Bugarone group (BU; Pliensbachian–lower Tithonian) [24]. Its total thickness reaches ~40 m but shows pronounced local variation (Lithostratigraphic column, Figure S1).

The basal unit (BU1)—corresponding to Calcari nodulari dell’Infernaccio (Pliensbachian p.p.–Toarcian p.p) [25]—is the thickest, reaching up to ~25 m. It consists of whitish, pink, or hazel micritic limestones, commonly containing scattered pyrite. The lower part is often nodular and rich in bioclasts. BU2—corresponding to Calcari nodulari e marne verdi de I Ranchi (Toarcian p.p) [25]—comprises gray–yellow or reddish marlstones, generally entirely nodular, and reaches up to 8 m in thickness on the northern side of Mt Valmontagnana. BU3—corresponding to Calcari nodulari a filamens di Fosso del Presale (upper Toarcian–lower Bajocian) [25]—typically consists of a few metres of light brownish limestone, often very rich in Posidonidae.

BU4 is composed of argillaceous and siliceous limestones, grey–green in colour, locally containing chert layers. Its thickness varies from 0 to ~15 m. In the most typical condensed successions this unit is absent, indicating a regional hiatus on structural highs from the lower Bajocian to the upper Kimmeridgian [20,26,27]. BU5—corresponding to Calcari nodulari ad ammoniti ed aptici di Cava Bugarone (Kimmeridgian p.p.–Tithonian p.p.) [25]—consists of a few metres of micritic, fossiliferous limestone that marks the return to prevailing carbonate sedimentation.

The group exhibits marked lateral variability. It progressively thins toward the northeastern sector, whereas the BU4 level—absent in most outcrops—appears in a restricted southern area, reaching ~15 m in thickness, and also on the northwestern side of the gorge, where it forms a few-metre-thick chert-free horizon (geological map, Figure S1).

4.1.3. Calcari Diasprigni

The Calcari Diasprigni (CDU; Bajocian p.p.–Tithonian p.p.) forms the uppermost part of the Jurassic basinal succession, corresponding to the “complete succession” [20], which also includes Corniola (COI), Marne del Mt Serrone (RSN) and Rosso Ammonitico (RSA), Calcari e marne a Posidonia (POD) formations (not exposed in the study area; see Mesozoic stratigraphic scheme, Figure S1). The CDU comprises two members, not mapped separately, with a total thickness of 80–100 m.

The lower membro selcifero consists of thin-bedded detrital cherty limestones and chert, with chert becoming dominant in the central part of the unit. Upward, the carbonate content increases, accompanied by a colour shift to reddish hues. This transition leads into the upper member (calcari a Saccocoma e Aptici), which consists of grey–green, cherty biodetrital limestones.

The unit crops out only along the northeastern margin of the study area, on the eastern limb of the Pierosara syncline, where extensive exposures of the entire complete succession occur. In the Frasassi anticline, only the grey–green cherty limestones within the Grotta dell’Inferno, a cave developed along the stratigraphic boundary with the overlying Maiolica, are attributed to this unit (star 1 in the geological map, Figure S1).

4.1.4. Maiolica

The Maiolica (MAI; Tithonian p.p.–Aptian p.p.) marks the return to more uniform sedimentary conditions across the entire basin, although significant variations in thickness and lithology persist depending on the underlying Jurassic succession. The Formation consists of white micritic cherty limestone. with grey to black chert occurring as nodules and layers.

In the Pierosara syncline, the Maiolica reaches 250–300 m in thickness and shows a transitional contact with the underlying CDU. In contrast, in the Frasassi anticline, where it overlies the BU, its thickness decreases to 120–140 m. Here, near the stratigraphic base, chert is rare or absent, and the limestone layers are often partially or entirely dolomitised, resulting in a saccharoidal texture and a dark yellowish colour. The Formation also thickens in the Mt Rimosse area, where geological and stratigraphic relationships suggest a transition toward a basinal succession (cross-section C, Figure S1). The upper part of the Maiolica is more uniform, and near the contact with the overlying unit, the limestone becomes darker and includes thin interbeds of black shale.

4.1.5. Marne a Fucoidi

The Marne a Fucoidi (FUC; Aptian p.p.–Albian p.p.) conformably overlies the MAI and records a more clay-rich sedimentation in the basin. It consists of regularly bedded marlstone and calcareous mudstone with thin interbeds of black shale. The clay content decreases progressively upwards. The prevailing colour is grey–green, with less frequent reddish horizons. In the study area, it is approximately 40 m thick.

4.1.6. Scaglia Bianca

The Scaglia Bianca (SBI; Albian p.p.–Turonian p.p.) is a 60–70 m thick unit that marks a return to predominantly carbonate sedimentation. Its lower portion consists of whitish marly limestone in 20–30 cm thick beds, interlayered with thin bituminous horizons and frequent pink–orange chert. The upper part is more calcareous and contains distinctive levels of zoned black chert. A bituminous marker bed, up to 1 m thick (the Bonarelli Level), occurs a few metres below the top of the formation.

4.1.7. Scaglia Rossa

The Scaglia Rossa (SAA; Turonian p.p.–Lutetian p.p.) is a predominantly reddish limestone unit, subdivided into three or four informal members [28], which have not been mapped separately.

The basal member consists of well-stratified pink limestone containing light-red chert in laminae or nodules. This is overlain by a chert-free reddish limestone—which includes the Cretaceous–Palaeogene (K–Pg) boundary—followed by brick-red argillaceous limestone and, finally, an uppermost member of pink to red limestone interbedded with red chert layers.

The chert-free Cretaceous interval contains calcarenitic and calcilutitic turbidite beds, within which Fossa Mancini [4] documented at Mt. Rimosse a rudist too large to have been transported. These detrital deposits derived from a carbonate-platform source and are more abundant outside the study area, where the Scaglia Rossa reaches greater thickness [29,30].

In the Frasassi anticline, the formation reaches nearly 150 m in thickness. In the syncline area it increases to around 200 m, although its true thickness is often difficult to determine due to intense folding. Bedding is commonly irregular as a result of synsedimentary deformation. A major slide affected the second and third intervals in the northern sector of the Frasassi anticline. Locally, the reddish coloration is absent, such as near San Vittore village, where it fades along a surface that cross-cuts bedding.

4.1.8. Scaglia Variegata

The scaglia variegata (VAS; Lutetian p.p.–Bartonian p.p.) consists of an alternation of thin-bedded pink to whitish or light green argillaceous limestones and grey or reddish marlstones. Bedding is commonly irregular due to synsedimentary deformation. The unit reaches a total thickness of approximately 50 m.

4.1.9. Scaglia Cinerea

The Scaglia Cinerea (SII; Bartonian p.p.–Aquitanian p.p.) is composed of about 150 m of argillaceous limestones, marlstones, and calcareous mudstones in 10–20 cm thick beds, with carbonate content decreasing upward. Grey tones predominate, although many reddish beds occur. In tectonised zones, the presence of these reddish beds often makes it difficult to distinguish the Scaglia Cinerea from the underlying scaglia variegata.

4.1.10. Bisciaro

The Bisciaro (BIS; Aquitanian p.p.–Burdigalian p.p.) comprises alternating dark argillaceous and siliceous limestones, marlstones, and calcareous mudstones, with volcaniclastic interbeds. It reaches several tens of metres in thickness but is poorly exposed within the mapped area.

4.1.11. Quaternary Deposits

Quaternary deposits are dominated by scree composed of angular clasts derived from cold-climate weathering of the carbonate bedrock. These deposits locally can include variable amounts of fine-grained material from marly units. Along the slopes, the marlstones interbedded within the carbonate succession have favoured the development of large, generally inactive landslides. Valley floors are infilled with alluvial sediments, primarily gravels, with minor terraced deposits preserved along the Sentino river valley.

A distinctive feature of the area’s geomorphological evolution is the extensive hypogene cave system, which extends from the present river bed at ~200 m a.s.l. up to altitudes of ~500 m. These caves are of considerable scientific significance [1], but in the context of this study, they are primarily valued because they provide unique access to geological data from within the mountain.

4.2. Structural Setting

4.2.1. Main Tectonic Elements

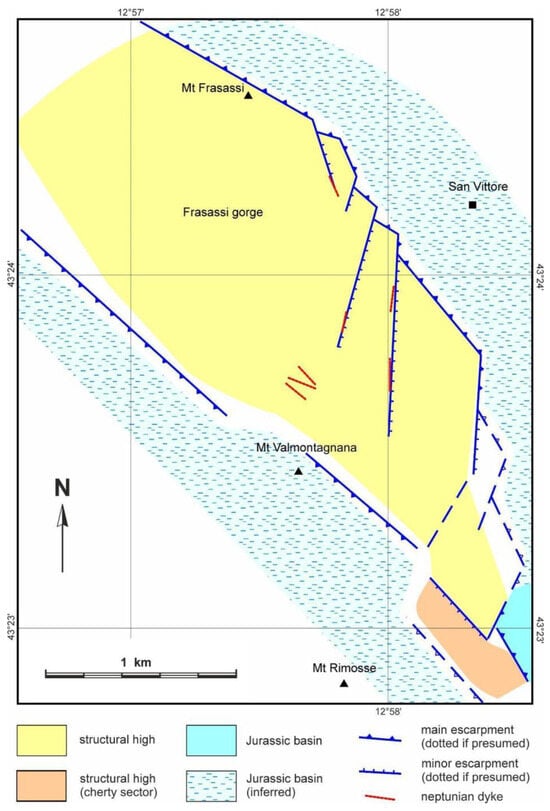

The Frasassi anticline dominates the study area (Figure 6). It is markedly asymmetric, with a gentle, extended western limb and a steep to vertical, eastern limb, and displays an ENE vergence (see cross-sections, Figure S1). North of the Frasassi Gorge, the structure plunges into its periclinal termination.

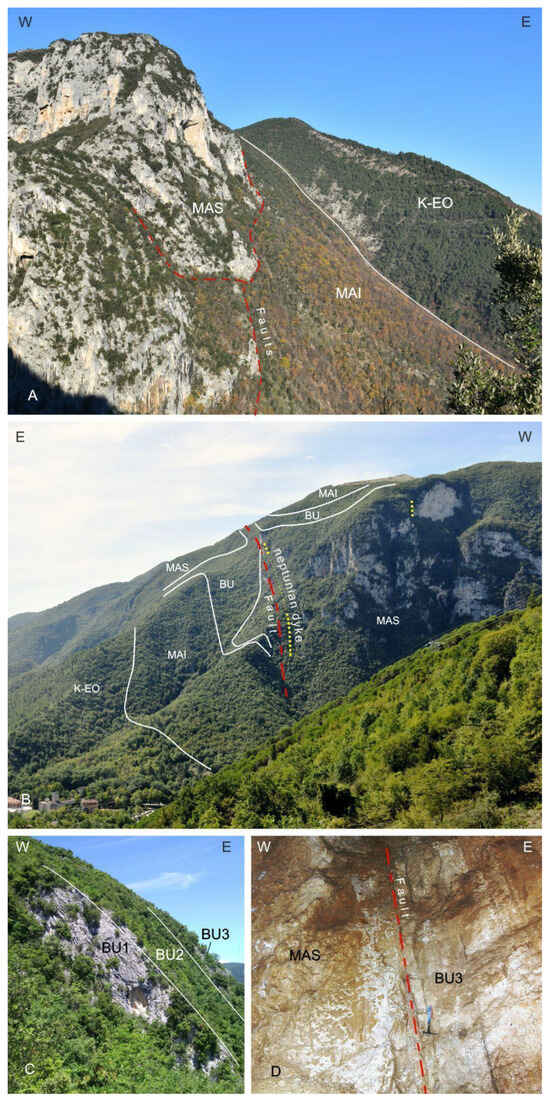

Figure 6.

Panoramic view of the western limb of the Frasassi anticline, showing main faults and stratigraphic boundaries (viewpoint from ENE: 43°24′22′′ N 12°59′08′′ E). Labels: MAS—Calcare Massiccio; BU—Bugarone group; MAI—Maiolica; K—Cretaceous Fms; K–EO—Cretaceous–Eocene Fms.

The anticline lies in the hanging wall of a thrust that places it above the Pierosara syncline along the valleys of the Sentino and Esino rivers. The thrust surface follows the main valley, where it is buried beneath alluvial deposits, and is generally poorly exposed. North of the Pierosara village, the thrust progressively loses displacement, and deformation is expressed by a system of asymmetric folds. In this northern sector, the syncline has a gentle eastern limb, whereas towards the south it evolves into a tight fold in the thrust footwall, characterised by predominantly steep bedding.

The most prominent structure in the area is the tectonic contact between the Calcare Massiccio (MAS) and the Maiolica (MAI) on the eastern limb of the anticline (Figure 6). This contact has previously been interpreted as the result of the MAS of a Jurassic structural high being driven during folding against the pelagic units of the adjacent basin [7]. Buttressing of the pelagic succession against the rigid MAS of the footwall block produced verticalisation of the pelagic succession, accompanied by additional uplift of the Jurassic high.

The present survey confirms this interpretation but also reveals a more complex geometry than previously shown on maps. Along this main tectonic contact, the MAS surface at several locations (43°24′06′′ N 12°57′51′′ E; 43°23′27′′ N 12°58′14′′ E; 43°23′15′′ N 12°58′17′′ E) is draped by discontinuous thin coatings of pelagic limestone attributable to BU. Furthermore, the contact is not continuous but segmented and offset by transverse faults, predominantly oriented NNE–SSW, with a right-lateral strike-slip component inferred from their geometry and locally supported by slickenlines. Based on the local characteristics, three distinct sectors can be distinguished.

On the northern side of the gorge, there is a sharp contact where the MAS, only partially folded eastwards, is juxtaposed against vertical beds of the MAI (Figure 7A). This striking geometry influenced the representation of the tectonic contact in previous maps, extending its interpretation southwards across the entire area.

Figure 7.

Tectonic contacts between the MAS and overlying units on the eastern limb of the Frasassi anticline. (A) Sharp contact between MAS and verticalised MAI beds north of the gorge (viewpoint from S: 43°23′55′′ N 12°58′01′′ E). (B) Folded surface of the Jurassic high with transfer fault and neptunian dyke traces (viewpoint from N: 43°24′37′′ N 12°58′08′′ E). The tectonic contact between MAS and vertical MAI beds along the eastern edge of the folded Jurassic high is visible only inside the caves, below the topographic surface (stars 2 in the geological map, Figure S1). (C) Highly inclined BU beds (viewpoint from S: 43°23′38′′ N 12°58′15′′ E). (D) Tectonic contact between MAS and vertical BU3 beds inside the cave (star 3 in the geological map, Figure S1); the MAS beds, not visible in the image, dip ~45° eastwards. Labels: MAS—Calcare Massiccio; BU—Bugarone group: (sub-units as in the main text: 1—Pliensbachian limestone; 2—Toarcian marlstone; 3—Aalenian–Bajocian limestone); MAI—Maiolica; K–EO—Cretaceous–Eocene Fms.

South of the gorge, the MAS and the overlying BU are strongly folded within the anticline limb, with dips reaching up to 60° (Figure 7B,C). The boundary with the vertical MAI beds in the fold limb is not exposed at the surface. Observations inside the caves show that the tectonic contact may occur either between the MAS, inclined at about 45°, and vertical beds of MAI (star 2 in the geological map, Figure S1), or between the MAS and vertical beds of BU3 (star 3 in the geological map, Figure S1 and Figure 7D). At the latter site, stratigraphic analysis indicates that the lower BU sub-units, and probably BU5, are absent, with only BU3 interposed between MAS and MAI.

At the southern termination of the Jurassic outcrops, a basinal setting is indicated by the presence of the CDU within the Grotta dell’Inferno, a cave that follows the CDU–MAI stratigraphic boundary from the southernmost MAS body northwards towards the main MAS outcrops (star 1 in the geological map, Figure S1). At the surface, the small MAS body is disrupted by irregular pockets of BU infill, and its eastern tectonic contact coincides with the top of a Jurassic palaeo-escarpment onlapped by the CDU, which is exposed only as a narrow 1–2 m band. Inside the cave, however, the CDU attains thicknesses exceeding 15 m, without the base being exposed.

In addition to this main tectonic contact, a set of NW–SE normal faults cuts across the crest zone of the anticline. These faults can reach a throw of over 100 m, with the southwestern block generally downthrown, although minor antithetic faults also occur. They offset the Cretaceous–Paleogene units, and their southern terminations are truncated by the NNE–SSW fault system. Despite their significant throw and continuity, these structures produce no significant morphological expression.

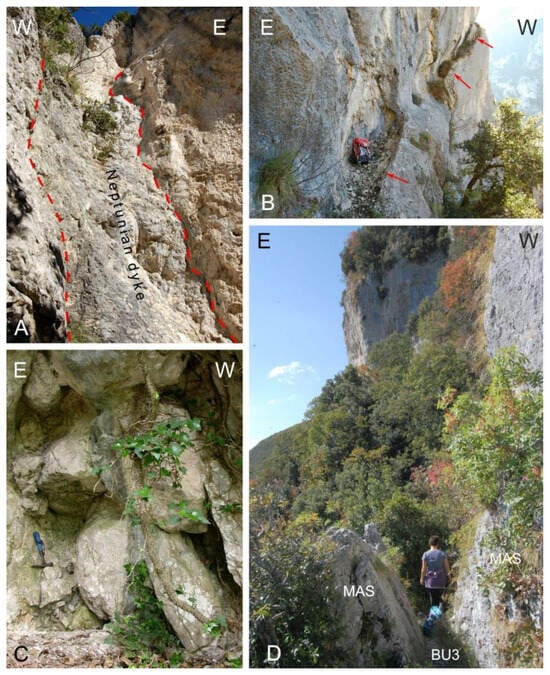

4.2.2. Neptunian Dykes

Jurassic neptunian dykes, often cross-cut by younger fractures, add a further structural complexity. North of the gorge (Figure 2), near the faulted contact with the MAI, two dykes (250/88° and 060/60°) occur ~100 m below the top of MAS (Figure 8A,B). They are filled with rounded pebbles embedded in a micritic to microclastic matrix, both sourced from the overlying BU, and contain rare MAS clasts.

Figure 8.

Neptunian dykes filled with Bugarone limestone. (A,B) Dykes on the southern slope of Mt Frasassi (outcrop location: 43°24′11′′ N 12°57′42′′ E). Mt Valmontagnana dykes: (C) Large dyke fill with boulders of BU1 and MAS in BU3 micrite (outcrop location: 43°23′50′′ N 12°57′46′′ E). (D) Open entrance of a neptunian dyke with bioclastic BU3 fill (outcrop location: 43°23′42′′ N 12°57′58′′ E). Labels: MAS—Calcare Massiccio; BU3—Aalenian–Bajocian Bugarone group limestone (sub-units as in the main text).

South of the gorge (Figure 7B), a large vertical dyke striking approximately N15E descends more than 100 m below the top of the MAS. It is filled with boulders of MAS, BU1, and brownish limestone, attributable to BU3, within a grey–green micritic matrix (Figure 8C). The most noteworthy dyke is located farther east, where it is exposed at two different structural levels. To the south, it appears as an open fissure near the top surface of MAS, dipping 090/70° and is filled with BU3 material, with abundant Posidonidae (Figure 8D). Downslope to the north, it widens into a some-metre-thick dyke filled with BU-derived material within a steep ravine. This dyke almost coincides with a fault that, in its southern sector, cuts the MAS–BU boundary, whereas farther north it juxtaposes MAS and MAI (geological map, Figure S1).

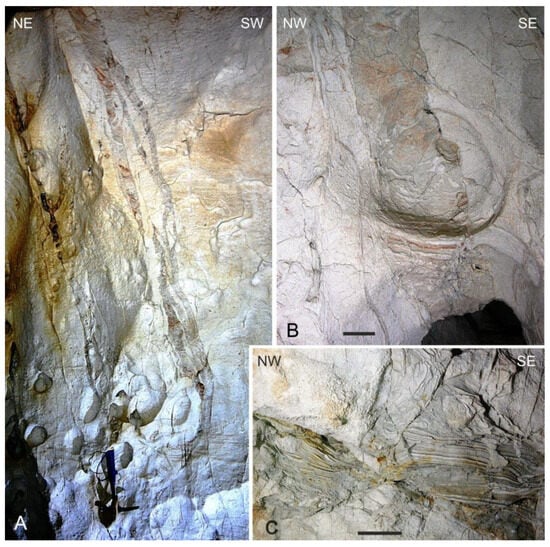

Seven additional main dykes, together with smaller veins, occur within the cave system (stars 4 and 5 in the geological map, Figure S1) at ~220 m elevation, over 500 m below the platform surface (Figure 9). These dykes strike between N110E and N140E (roughly N130E) with steep dips and antithetical orientations. Their micritic to microclastic fills resemble BU material, though no biostratigraphic indicators are present. Internal laminations, formed by gravitational settling, are highlighted by differential karst corrosion.

Figure 9.

Neptunian dykes inside the cave, more than 500 m below the platform surface, with micritic and microclastic fills. (A) A sequence of sub-parallel dykes on a cave wall (hammer for scale) (location: star 4 in the geological map, Figure S1). (B,C) Neptunian dykes showing gravitational lamination, highlighted by differential karst corrosion (scale bar ≈ 10 cm) (location: star 5 in the geological map, Figure S1).

5. Discussion

5.1. The Jurassic Structure

The Jurassic rocks are represented by a main MAS outcrop elongated NW–SE, overlain by a condensed succession deposited on a tectonic high. The marginal fault escarpments that typically bound such highs are not directly exposed, but their position can be inferred from structural and stratigraphic relationships documented during the survey (Figure S1).

On the southwestern side, evidence for a buried palaeo-escarpment is provided by: (i) the extremely condensed Jurassic deposits, associated with pervasive silicification of the MAS along its tectonic contact with the MAI southeast of Mt. Valmontagnana; (ii) the set of deep, N130E–oriented neptunian dykes observed in the Frasassi caves (stars 4 and 5 in the geological map, Figure S1). Both features are typical of Jurassic submarine escarpments (see Section 2.2 in [31] and references therein), suggesting that the edge of the Jurassic outcrops approximately coincides with the original margin of the tectonic high.

Along the northeastern edge, the sub-horizontal MAS strata (observed at the surface and in caves; star 6 in the geological map, Figure S1) are nearly juxtaposed with the steeply inclined beds of the Cretaceous formations in the periclinal termination, with only a discontinuous thin drape of BU limestone interposed. This geometry may be explained by a pre-existing bending of the pelagic Jurassic units and the lower MAI above a buried escarpment, further accentuated by differential compaction [32]. The absence of fault continuation from the MAS into the overlying units supports the interpretation that the edge of the Jurassic outcrops approximates the original limit of the Jurassic high against the non-outcropping basin.

Along the top surface of the Jurassic high, variations in thickness and facies within the condensed succession likely reflect primary irregularities of the depositional surface. In the southwestern sector, the occurrence of a thin, silica-rich level (BU4) similar to the coeval CDU Formation of the basins, suggests that these areas represented relatively depressed portions of the high (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Jurassic palaeogeographic scheme, restored based on evidence of palaeo-escarpments, dyke distribution, fault geometry, and folding effects.

The MAS substrate of the structural high is cut by large, deep neptunian dykes that record Jurassic fracturing events and provide valuable insights into tectonic evolution. Although most dykes are nearly vertical, they can be attributed to extensional tectonics, as suggested by the cutoff angles of the associated faults (cross-section B, Figure S1), and they originally dipped eastwards.

Fracturing of the MAS platform, linked to the early Mesozoic rifting phase, began in the Sinemurian, coinciding with the onset of pelagic sedimentation in the newly formed basins [33]. While most displacement occurred during the early Sinemurian [34], the presence of dykes filled with Bugarone sediments indicates that the fractures remained open and allowed sediment infiltration from the top of the structural high for a prolonged period, at least until the Bajocian.

Neptunian dykes filled with Jurassic pelagic sediments are well known in the region, but they typically occur close to the surface of palaeo-escarpments. These structures, together with other sedimentological and stratigraphic indicators such as resedimented deposits and unconformities, are considered indirect evidence of fault reactivation after the main Sinemurian event [19,31,35,36,37].

The large size of the Frasassi dykes and their development to depths exceeding 500 m below the platform surface, as verified inside the cave system, demonstrate that they cannot have formed by superficial gravitational extension along the palaeo-escarpment. Instead, they provide compelling evidence for persistent synsedimentary tectonic activity along the margins of Jurassic structural highs.

At Frasassi, the dykes are predominantly oriented NW–SE and N–S. The NW–SE orientation corresponds to the inferred margins of the high, whereas the N–S dykes are oblique and may have formed along transfer faults within the extensional regime (Figure 10).

By integrating structural orientation, palaeo-escarpment evidence, dyke distribution, fault geometry and folding effects, the Jurassic high of Frasassi can be reconstructed as a NW–SE elongated block, a common geometry for Jurassic structural highs [12,38]. It was likely bounded by two antithetic faults and segmented by transverse transfer faults along the main scarps (Figure 10 and Figure 11A).

Figure 11.

Schematic representation of the tectonic evolution of the Frasassi area. (A) Jurassic extensional tectonics fragmented the carbonate platform, forming structural highs and basins, filled by thicker pelagic deposits. (B) During the Cretaceous, basin infilling was completed, while minor extensional tectonics contributed to seafloor instability until the Eocene. (C) Development of normal faults on the western side of the Frasassi structure, possibly related to Miocene extensional tectonics affecting the region. (D) Final structure of the Frasassi anticline following the Messinian thrusting event. Evidence of Quaternary extensional activity was not found in the area, unlike in the western sectors of the Apennine ridge.

5.2. Post Jurassic Extensional Tectonics

No new structural evidence attributable to the Cretaceous–Paleogene tectonic phase has been identified beyond what was previously documented [7]. One of the most striking features remains the large slump affecting the second and third intervals of the Scaglia Rossa, which indicates prolonged seafloor instability likely related to tectonic activity that persisted until the Eocene (Figure 11B).

The NW–SE trending fault system along the anticline crest developed approximately along the inferred edge of the Jurassic high, suggesting that these faults may have reactivated pre-existing Jurassic structures. Although direct evidence is lacking, the absence of morphological or structural indicators of Quaternary activity supports the interpretation that their formation is linked to the Messinian extensional tectonics that affected the region (Figure 11C). Fault systems of similar orientation and characteristics are documented in neighbouring areas to the east [39], reinforcing this hypothesis.

5.3. Thrusting

The onset of contractional deformation in the study area is attributed to the late Messinian [12]. This tectonic phase induced folding and overthrusting of the Frasassi anticline onto the Pierosara syncline (Figure 11D). This event may have been influenced by pre-existing Jurassic tectonic discontinuities, facies variations, and thickness heterogeneities [40].

In the anticline, the Jurassic structural high behaved as a rigid body elongated NW–SE, oblique (~20–30°) to the main thrust direction. Consequently, different sectors of the high experienced distinct deformation within the fold. The buried southwestern margin of the Jurassic high, located in the axial zone, underwent only mild deformation during folding, whereas the northeastern margin was rotated within the narrow curvature zone adjacent to the thrust. As a result, along the northeastern margin the hanging-wall succession adjacent to the Jurassic faults became verticalised by buttressing against the MAS surfaces of the palaeo-escarpments. This process was accompanied by further uplift of the palaeo-escarpments relative to the adjacent basinal sectors, which remained buried at depth.

The deformation involved displacement both along fault planes and through disharmonic slip between the rigid MAS block and the overlying finely bedded pelagic deposits. Fault motion occurred predominantly along a set of NNE–SSW faults with a right-lateral strike-slip component, which frequently reactivated pre-existing Jurassic faults, as indicated by their correspondence with deep neptunian dykes. Within the condensed succession, the BU2 marly bed acted as a detachment horizon, allowing the upper BU3 to decouple from the underlying BU1 and MAS and to follow the folding of the overlying MAI (Figure 7D).

In the Mt Frasassi area, north of the gorge, the Jurassic high lies entirely within the western limb and crest of the anticline, and its marginal paleo-escarpment abuts against the vertical or overturned MAI beds on the eastern limb and near the fold’s periclinal termination (Figure 7A). In contrast, south of the gorge, in the Mt Valmontagnana area, the original margin is not exposed, as the Jurassic high occupies mainly the hinge zone of the anticline, attaining steep dips within the fold limb (Figure 7B).

Further south, where the width of the Jurassic high appears to decrease, the contact with the MAI reverts to a sharp boundary, probably along reactivated N–S and NNE–SSW transfer faults. Finally, at the southernmost location, a weakly deformed contact occurs between the upper units of the Jurassic basin and the palaeo-escarpment.

5.4. Post-Thrusting Tectonics

Earlier studies suggested recent tectonic activity based on the general evolution of the caves [41]. Coltorti & Galdenzi [42] proposed a displacement of Middle Pleistocene cave levels exceeding 40 m. However, this hypothesis was effectively refuted by the exploration of passages which extend beyond the fault at the same cave level.

More recently, Holocene tilting of the Frasassi anticline has been linked to the reactivation of a fault located ~6.5 km to the ENE [8]. A vertical throw of approximately 24 m over the last 8400 years can be calculated from the rotational angles reported by those authors. That fault, however, was considered Messinian in age, and no morphological or depositional evidence of its recent activity has been documented [10,11,12]. Moreover, historical seismicity records [43] do not support fault movements of this magnitude. Assuming the inclination measurements of former water levels recorded by calcite rims inside the caves are accurate, although Mariani et al. [8] did not report associated uncertainties, the tilting is more plausibly explained by processes unrelated to fault displacement.

The comprehensive field survey conducted in this study likewise did not reveal any direct evidence for significant Quaternary faulting in the mapped area, in contrast with the westernmost sectors of the central and northern Apennines, where an extensional tectonic activity is well documented both in surface geological structures and by seismicity [38,44,45,46,47,48,49]. Minor post-thrusting deformation due to extensional tectonics in the study area cannot be excluded; however, its effects, if present, appear to have been negligible compared with those of the earlier tectonic phases.

6. Conclusions

The principal outcome of this study is the new geological map of the Frasassi area, which integrates detailed surface observations with data obtained from the cave system. This map provides a comprehensive structural and stratigraphic framework that constitutes the basis for future research on more specific aspects, including sedimentology, tectonics, hydrogeology, and also cave development.

In addition to its cartographic value, the mapping has yielded significant geological insights. It has refined the stratigraphic and structural knowledge of the area within the broader context of the Umbria–Marche domain, providing new details on the Calcare Massiccio (MAS) and its relationships with the overlying formations. The reconstruction of the Jurassic structural high has revealed its NW–SE elongation, bounded by antithetic and transfer faults, a geometry consistent with that of other regional Jurassic highs. The occurrence of deep neptunian dykes, extending more than 500 m below the platform surface, provides compelling evidence of long-lived Jurassic fault activity and synsedimentary tectonism along the margins of the structural high. The results also demonstrate the structural inheritance of these discontinuities in subsequent deformation, especially during Messinian thrusting.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/geosciences15120454/s1, Figure S1: Geological map of the Frasassi Gorge (northern Apennines, Italy) with three geological cross-sections, a regional Mesozoic stratigraphic scheme and the local stratigraphic column. Figure S2: georeferenced version of the 1:10,000-scale geological map.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The geological map at 1:10,000 is available in the Supplementary Materials of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Galdenzi, S.; Jones, D.S. The Frasassi caves: A “classical” active hypogenic cave. In Hypogene Karst Regions and Caves of the World; Klimchouk, A.B., Palmer, A.N., De Waele, J., Auler, A., Audra, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centamore, E.; Deiana, G.; Micarelli, A.; Potetti, M. Il Trias–Paleogene delle Marche. Studi Geol. Camerti 1986, Special Volume “La Geologia delle Marche”, 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cresta, S.; Monechi, S.; Parisi, G. Mesozoic–Cenozoic Stratigraphy in the Umbria-Marche Area. Mem. Descr. Carta Geol. d’Italia 1989, 39, 185. [Google Scholar]

- Fossa Mancini, E. Geologia ed idrogeologia della Gola del Sentino nella Marca di Ancona. G. Geol. Prat. 1921, 16, 12–51. [Google Scholar]

- Coltorti, M. Geologia della regione di M. Pietroso-M. Murano (Appennino Marchigiano); Università Degli Studi di Ferrara: Ferrara, Italy, 1980; Volume 7, pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Barchi, M.; Lavecchia, G.; Menichetti, M.; Minelli, G.; Nardon, S.; Pialli, G. Analisi della fratturazione del Calcare Massiccio in una struttura anticlinalica dell’Appennino umbro-Marchigiano. Boll. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1991, 110, 101–124. [Google Scholar]

- Cello, G.; Gazzani, D.; Marchegiani, L.; Mazzoli, S.; Tondi, E. Assetto geologico-strutturale ed evoluzione tettonica dell’area di Frasassi. Studi Geol. Camerti 1997, 14, 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Mariani, S.; Mainiero, M.; Barchi, M.; van der Borg, K.; Vonhof, H.; Montanari, A. Use of speleologic data to evaluate Holocene uplifting and tilting: An example from the Frasassi anticline (northeastern Apennines, Italy). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2007, 257, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regione Marche. Carta Geologica Regionale CTR. Available online: https://www.regione.marche.it/Regione-Utile/Paesaggio-Territorio-Urbanistica/Cartografia/Repertorio/Cartageologicaregionale10000#PDF-e-GeoTIFF (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Servizio Geologico d’Italia. Carta Geologica d’Italia alla scala 1:50,000, Foglio 302 Tolentino; ISPRA: Roma, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Deiana, G.; Pambianchi, G. Note Illustrative della Carta Geologica d’Italia Alla Scala 1:50,000, Foglio 302 Tolentino; ISPRA: Roma, Italy, 2009; 116p. [Google Scholar]

- Deiana, G.; Cello, G.; Chiocchini, M.; Galdenzi, S.; Mazzoli, S.; Pistolesi, E.; Potetti, M.; Romano, A.; Turco, E.; Principi, M. Tectonic evolution of the external zones of the Umbria-Marche Apennines in the M. S. Vicino-Cingoli area (Central Italy). Boll. Soc. Geol. Ital. 2002, 1, 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Barchi, M.; Menichetti, M.; Pialli, G.; Merangola, S.; Tosti, S.; Minelli, G. Struttura della ruga marchigiana esterna nel settore M. S. Vicino-M. Canfaito. Boll. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1996, 115, 625–648. [Google Scholar]

- Boncio, P.; Ponziani, F.; Brozzetti, F.; Barchi, M.; Lavecchia, G.; Pialli, G. Seismicity and extensional tectonics in the northern Umbria-Marche Apennines. Mem. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1998, 52, 539–556. [Google Scholar]

- Martinis, B.; Pieri, M. Alcune notizie sulla formazione evaporitica del Triassico superiore nell’Italia centrale e meridionale. Mem. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1964, 4, 649–678. [Google Scholar]

- Pialli, G. Facies di piana cotidale nel Calcare Massiccio dell’Appennino Umbro-Marchigiano. Boll. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1971, 90, 481–507. [Google Scholar]

- Colacicchi, R.; Passeri, L.; Pialli, G. Evidences of tidal environment deposition in the Calcare Massiccio Formation (Central Apennines-Lower Lias). In Tidal Deposits, a Casebook of Recent Examples and Fossil Counterparts; Ginsburg, R., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1975; pp. 345–353. [Google Scholar]

- Brandano, M.; Corda, L.; Tomassetti, L.; Testa, D. On the peritidal cycles and their diagenetic evolution in the Lower Jurassic carbonates of the Calcare Massiccio Formation (Central Apennines). Geol. Carpathica 2015, 66, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Società Geologica Italiana; Istituto di Geologia, Università di Perugia. Guida alle Escursioni. Simposio “Sedimentologia delle Rocce Carbonatiche di Mare Sottile”, 5–7 October 1973; University of Perugia: Perugia, Italy, 1973; 24p. [Google Scholar]

- Centamore, E.; Chiocchini, M.; Deiana, G.; Micarelli, A.; Pieruccini, V. Contributo alla conoscenza del Giurassico dell’Appennino umbro-marchigiano. Studi Geol. Camerti 1971, 1, 7–89. [Google Scholar]

- Petti, F.M.; Falorni, P.; Marino, M. Calcare Massiccio. In Carta Geologica d’Italia 1:50,000. Catalogo Delle Formazioni—Unità Tradizionali (1); Cita, M.B., Abbate, E., Aldighieri, B., Balini, M., Conti, M.A., Falorni, P., Germani, D., Groppelli, G., Manetti, P., Petti, F.M., Eds.; Quad. Serv. Geol. d’It., Ser. III, 7 (VI); APAT: Roma, Italy, 2007; pp. 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Colacicchi, R.; Pialli, G. Significato paleogeografico di alcuni depositi ad alta energia nella parte sommitale del Calcare Massiccio (nota preliminare). Boll. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1973, 92 (Suppl. S1), 173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Fabbi, S.; Santantonio, M. Footwall progradation in syn-rift carbonate platform-slope systems (Early Jurassic, Northern Apennines, Italy). Sediment. Geol. 2012, 281, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISPRA. Verbale Riunione Comitato Area Appennino Settentrionale. Successioni Carbonatiche Meso-Cenozoiche Dell’appennino Settentrionale e Centrale. 2002. Available online: https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/files/carg/verbale-7mag.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- ISPRA. Approfondimenti. Gruppo del Bugarone. Available online: https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/it/progetti/cartella-progetti-in-corso/suolo-e-territorio-1/progetto-carg-cartografia-geologica-e-geotematica/comitati-di-coordinamento/integrazione_approfondimenti.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Cecca, F.; Cresta, S.; Pallini, G.; Santantonio, M. Il Giurassico di Monte Nerone (Appennino marchigiano, Italia Centrale): Biostratigrafia, litostratigrafia ed evoluzione paleogeografica. In Atti II Conv. Intern. “Fossili, Evoluzione, Ambiente”; Pallini, G., Cecca, F., Cresta, S., Santantonio, M., Eds.; Tecnostampa Edizioni: Ostra Vetere, Italy, 1990; pp. 63–139. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolini, A.; Cecca, F. 20 My hiatus in the Jurassic of Umbria-Marche Apennines (Italy): Carbonate crisis due to eutrophication. Earth Planet. Sci. 1999, 329, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petti, F.M.; Falorni, P. Scaglia Rossa. In Carta Geologica d’Italia 1:50,000. Catalogo Delle Formazioni—Unità Tradizionali (1); Cita, M.B., Abbate, E., Aldighieri, B., Balini, M., Conti, M.A., Falorni, P., Germani, D., Groppelli, G., Manetti, P., Petti, F.M., Eds.; Quad. Serv. Geol. d’It., Ser. III, 7 (VI); APAT: Roma, Italy, 2007; pp. 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Colacicchi, R.; Baldanza, A. Carbonate turbidites in a Mesozoic pelagic basin: Scaglia Formation, Apennines. Comparison with siliciclastic depositional models. Sediment. Geol. 1986, 48, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bice, D.M.; Montanari, A.; Rusciadelli, G. Earthquake-induced turbidites triggered by sea level oscillations in the Upper Cretaceous and Paleocene of Italy. Terra Nova 2007, 19, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santantonio, M.; Innamorati, G.; Cipriani, A.; Antonelli, M.; Fabbi, S. An exceptionally well-preserved Jurassic plateau-top to marginal escarpment in the Northern Apennines (Central Italy): Sedimentological, palaeontological and palaeostructural features. J. Iber. Geol. 2024, 50, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carminati, E.; Santantonio, M. Control of differential compaction on the geometry of sediments onlapping paleoescarpments: Insights from field geology (Central Apennines, Italy) and numerical modelling. Geology 2005, 33, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passeri, L.; Venturi, F. Timing and causes of drowning of the Calcare Massiccio platform in Northern Apennines. Boll. Soc. Geol. Ital. 2005, 124, 247–258. [Google Scholar]

- Santantonio, M.; Cipriani, A.; Fabbi, S.; Meister, C. Constraining the slip rate of Jurassic rift faults through the drowning history of a carbonate platform. Terra Nova 2022, 34, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdenzi, S. Megabrecce giurassiche nella dorsale marchigiana e loro implicazioni paleotettoniche. Boll. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1986, 105, 371–382. [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani, A.; Bottini, C. Unconformities, neptunian dykes and mass-transport deposits as an evidence for Early Cretaceous syn-sedimentary tectonics: New insights from the Central Apennines. Ital. J. Geosci. 2019, 138, 333–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, A.; Zuccari, C.; Innamorati, G.; Marino, M.C.; Petti, F.M. Mass-transport deposits from the Toarcian of the Umbria-Marche-Sabina Basin (Central Italy). Ital. J. Geosci. 2020, 139, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierantoni, P.; Deiana, G.; Galdenzi, S. Stratigraphic and structural features of the Sibillini Mountains (Umbria-Marche Apennines, Italy). Ital. J. Geosci. 2013, 132, 497–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoli, S.; Deiana, G.; Galdenzi, S.; Cello, G. Miocene fault-controlled sedimentation and thrust propagation in the previously faulted external zones of the Umbria-Marche Apennines, Italy. Stephan Mueller Spec. Publ. Ser. 2012, 1, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, P.; Calamita, F.; Tavarnelli, E. Along-strike variation of fault-related inversion folds within curved thrust systems: The case of the Central-Northern Apennines of Italy. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2022, 142, 105731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltorti, M. Geomorphologic evolution of a karst area subject to neotectonic movements in the Umbria-Marche Appennines (Central Italy). In Proceedings of the VIII International Congress of Speleology, Bowling Green, KY, USA, 18–24 July 1981; Beck, B.F., Ed.; Georgia Southwestern College: Americus, GA, USA, 1981; pp. 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Coltorti, M.; Galdenzi, S. Geomorfologia del complesso carsico Grotta del Mezzogiorno (4 MA AN)—Frasassi (1 MA AN) con riferimento ai motivi neotettonici dell’anticlinale di M.te Valmontagnana (Appennino Marchigiano). Studi Geol. Camerti 1983, 7, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Guidoboni, E.; Ferrari, G.; Tarabusi, G.; Sgattoni, G.; Comastri, A.; Mariotti, D.; Ciuccarelli, C.; Bianchi, M.G.; Valensise, G. CFTI5Med, the new release of the catalogue of strong earthquakes in Italy and in the Mediterranean area. Scientific Data 2019, 6, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calamita, F.; Pizzi, A. Tettonica quaternaria nella dorsale appenninica umbro-marchigiana e bacini intrappenninici associati. Studi Geol. Camerti 1993, Spec. Vol. 1992/1, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Calamita, F.; Pizzi, A.; Roscioni, M. I “fasci” di faglie recenti ed attive di M. Vettore-M. Bove e di M. Castello-M. Cardosa (Appennino umbro-marchigiano). Studi Geol. Camerti 1993, Spec. Vol. 1992/1, 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lavecchia, G.; Brozzetti, F.; Barchi, M.; Menichetti, M.; Keller, J.V.A. Seismotectonic zoning in east-central Italy deduced from an analysis of the Neogene to present deformations and related stress fields. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1994, 106, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stendardi, F.; Capotorti, F.; Fabbi, S.; Ricci, V.; Silvestri, S.; Bigi, S. Geological map of the Mt. Vettoretto–Capodacqua area (Central Apennines, Italy) and cross-cutting relationships between Mts. Sibillini Thrust and Mt. Vettore normal faults system. Geol. Field Trips Maps 2020, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaraluce, L.; Di Stefano, E.; Tinti, E.; Scognamiglio, L.; Michele, M.; Casarotti, M.; Cattaneo, M.; De Gori, P.; Chiarabba, C.; Monachesi, G.; et al. The 2016 Central Italy seismic sequence: A first look at the mainshocks, aftershocks, and source models. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2017, 88, 757–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civico, R.; Pucci, S.; Villani, F.; Pizzimenti, L.; De Martini, P.M.; Nappi, R.; Open Emergeo Working Group. Surface ruptures following the 30 October 2016 Mw 6.5 Norcia earthquake, central Italy. J. Maps 2018, 14, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).