Simple Summary

We documented maternal protective behaviors in a female humpback whale in response to harassment from escort males within a competitive group. Video footage was obtained from aerial drone recordings on 3 August 2022, at the Abrolhos Bank, Brazil. We applied an aerial photogrammetry technique to estimate the size of the calf, the female, and the four harassing males. Based on drone video analysis, we describe for the first time a female’s protective behaviors toward her calf, using her body and pectoral fins during approaches by male escorts and physical contact between the escorts and the calf as they attempted to approach the lactating female. The use of drones allows us to describe new behaviors, even of well-known cetacean species.

Abstract

While protective behaviors of baleen whales toward calves have been documented during predator attacks, they have not been observed in response to approach attempts by other males of the same species. We recorded high-resolution aerial drone videos of four competing male of humpback-whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) harassing a lactating female with her post-neonate calf in a breeding ground in Brazil. We document several protective behaviors and highlight a new role for pectoral fins in maternal protection, a function not previously attributed to this anatomical structure. These results confirm the value of using drones to describe new cetacean behaviors, even in well-known species.

1. Introduction

Protecting and nursing their young involves a significant energy expenditure for mysticetes [1,2] that undertake long migrations between feeding and breeding grounds. The lactating female humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) fasts until she migrates back to her feeding grounds, relying solely on her energy reserves to maintain her own metabolism and ensure calf development [3]. During this period, postpartum ovulation can still attract males seeking to mate with these lactating females, which become potentially receptive [4]. When competing for access to a lactating female, males can negatively affect calf development by increasing travel time, decreasing rest periods [5], and disrupting nursing [6]. Furthermore, the aggressive behavior of males competing for access to the female increases the risk of physical injury and separation of the calf from its mother [5]. Therefore, describing how females avoid male harassment and protect their calves allows for an assessment of the additional energetic costs inherent to mother–calf interactions involving escorts during the early stages of calf development and maternal care.

In several populations, female humpback whales segregate into shallower areas to spatially distance themselves from competing males [6,7,8]. However, on the Abrolhos Bank, Brazil, the primary humpback whale breeding ground [9,10] has low bathymetric variation, which leaves mother–calf pairs closer and more accessible to escort males [11]. This makes it a good location for evaluating interactions between lactating females and harassing males. Protective behaviors toward calves have been described for several baleen whale species during predation attempts by killer whales (Orcinus orca) [12,13,14], but not in response to approach attempts by conspecific males. We describe novel behaviors performed by a lactating female humpback whale to protect her calf from harassment by competing males, as well as physical contact initiated by escorts against the calf during their attempts to approach the female.

2. Materials and Methods

The use of drones facilitates the identification of cetacean behaviors below the water surface and can triple the observation time compared to vessel-based researchers [15]. We used a DJI Phantom 4 PRO drone to apply the “focal group follow” [16,17] method at an altitude of 9.3 to 37 m and record high-resolution (4K) aerial videos of the mother–calf pair and the four escorts. Recordings were made with a drone-mounted camera with a gimbal that moved to allow observation of all individuals in the group. The lens was aimed vertically downward 90° to the horizon to extract measurements. The total length of each whale in the group was estimated using a vertical aerial photogrammetry technique based on calibrated images collected by the drone: an object of known length of one meter and a fixed flight height of 20 m were used as a scale reference to correct for any inaccuracies in the drone’s barometric altimeter. The size of the reference object was measured in pixels and converted to meters considering the altitude provided by the drone’s barometer, camera focal length, sensor size sensor, and image resolution [18]. Three measurements of each individual were taken and body length estimated using an adjusted R script [19] available at [20]. No image grading was carried out during analysis. To classify calves, we used their total length in relation to that of their mothers. Calves were considered neonates if they measured up to one third of the length of the mother, and post-neonates if they were longer [21]. We also used a threshold of >11.2 m to distinguish juvenile from adult [22]. Videos were transcribed into digitally tabulated behavioral data using the BORIS v. 8.21.8 video coding software [23]. We calculated the absolute frequency (number of occurrences) of two types of behavioral events: (1) evasive and protective behaviors of lactating females towards their calves, and (2) escorts’ harassing behaviors toward the female that resulted in physical contact with the calf.

3. Results

On 3 August 2022, we observed a group of humpback whales for 46 min from the research boat, consisting of a mother–calf pair accompanied by four escorts that were competing intensely for access to the female. The observation occurred in the Abrolhos Bank, Brazil (location: 18.05641° S, 38.79886° W), near the 27 m isobath. Although the sex of the escorts could not be determined from biopsy samples, we assumed they were all males based on their aggressive competitive behavior [5,24].

3.1. Photogrammetry and Photoidentification

The estimated total length was 12.1 ± 0.02 m for the adult female and 5.3 ± 0.14 m for the calf. Thus, the female, at over 11.2 m, was classified as an adult, and the calf, with a relative length of 43.8% of the mother’s total body length, was classified as a post-neonate. Escort 1 (12.9 ± 0.05 m), Escort 2 (11.2 ± 0.24 m) and Escort 3 (12.2 ± 0.09 m) were classified as adults, while Escort 4 (10.8 ± 0.03 m) was classified as a juvenile. Two individuals were photo-identified and added to the Happywhale platform, including Escort 1 (IBJ-7094) (https://happywhale.com/individual/93312, accessed on 28 August 2025) and the female (IBJ-7097) (https://happywhale.com/individual/93310, accessed on 28 August 2025). The female was sighted in a competitive group on the Abrolhos Bank in 2024 without a calf (IBJ data).

3.2. Video Analysis

We recorded a total of 25.15 min of video during the focal group follow. However, we analyzed 21.49 min of aerial video footage in which all group members were clearly visible in the frame. During approach attempts by the males, our analysis identified 42 instances of protective behavior by the female toward the calf and nine potentially dangerous surface events initiated by the escorts toward the calf (Table 1 and Videos S1–S6).

Table 1.

Absolute frequency of novel humpback whale surface behaviors on the Abrolhos Bank, recorded during 21.49 min of aerial drone video. Behaviors include (a) male avoidance and calf protection by a lactating female, and (b) harassment of the female by four males, resulting in contact with the calf.

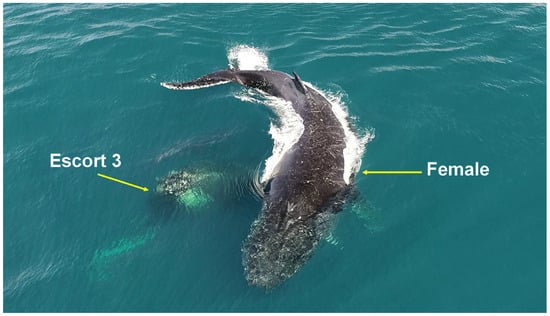

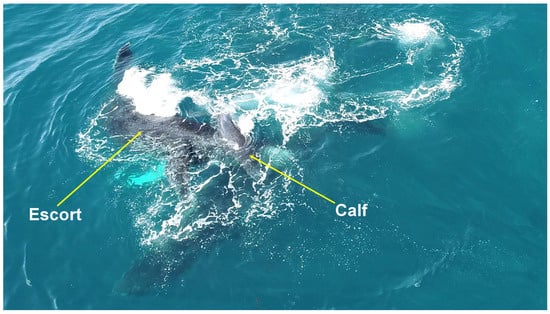

During male approach attempts, the female altered her direction of travel with sharp turning angles (Figure 1) and exhibited behaviors toward the calf using her head and pectoral fins.

Figure 1.

Acute reorientation behavior. A female humpback whale evading an escort with sharp turning angles on the Abrolhos Bank, Brazil.

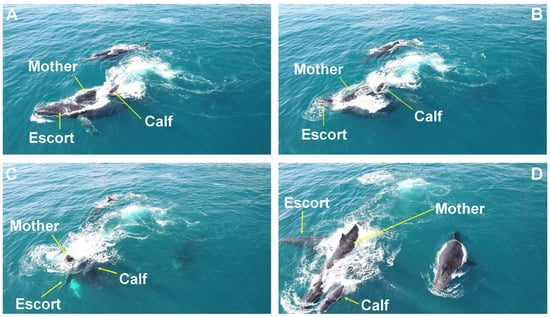

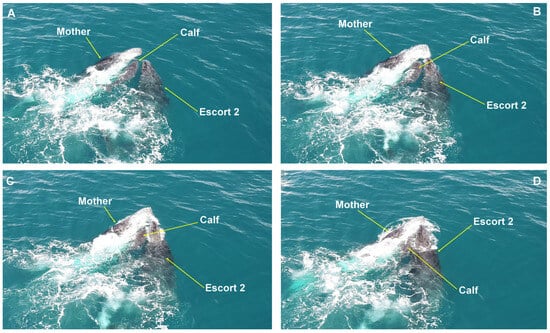

When an escort approached laterally, the female attempted to submerge it with her head, creating an opening for the calf to move to the opposite side of her body (Figure 2), or she moved with the calf positioned on either her right or left pectoral fin (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Head-push submersion behavior. Behavioral sequence of a female attempting to submerge a laterally approaching escort (A,B), creating an opening for the calf to move to the female’s opposite side (C,D). Observed on the Abrolhos Bank, Brazil.

Figure 3.

Pectoral fin carry behavior. A female moving with her calf on her left pectoral fin during an approach by escorts on the Abrolhos Bank, Brazil.

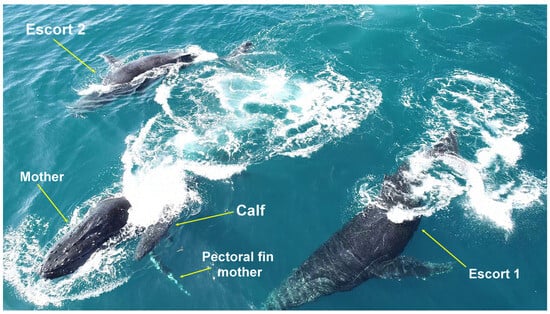

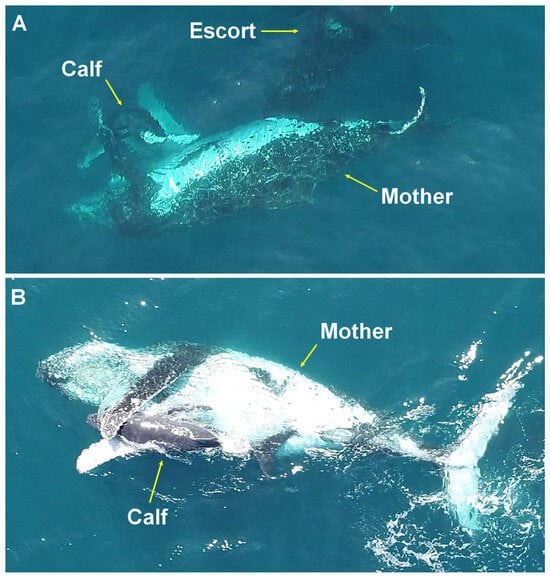

At other times, when one or more escorts approached from below or behind, the female drew the calf to her ventrum and extended her pectoral fins around it, sometimes crossing them (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Hug behavior. A female diving with her young between her pectoral fins (A) and with the ventral side facing upward and crossing her pectoral fins around her calf (B), prior to an approach from below by escort males on the Abrolhos Bank, Brazil.

The lactating female performed other behaviors already described in the literature, such as head and caudal fin slaps, to ward off the males and protect her calf (Table S1).

Despite the active protection of the female, escorts still managed to lift the calf with their heads on five occasions (Figure 5) and press the calf against its mother four times (Figure 6). Several behaviors characteristic of male–male competition were also recorded, such as “caudal fin slaps”, “extensions of the pectoral fin”, and “bubble trailing” [24] (Table S1).

Figure 5.

Head calf lift behavior. An escort lifts the calf with its head during an approach toward the female on the Abrolhos Bank, Brazil.

Figure 6.

Calf compression behavior. (A–D) showing a lateral approach by an escort, who presses the calf between himself and the female. From a competitive group on the Abrolhos Bank, Brazil.

4. Discussion

Humpback whale mother–calf pairs have been observed to strategically segregate into shallower waters to avoid male harassment in various breeding grounds, such as those in Ecuador [6,7] and Hawaiʻi [6,7]. In Serra Grande in Brazil, groups with calves were sighted in waters ten meters shallower than groups without calves [25]. However, the low depth variation in the Abrolhos Bank means that mother–calf pairs remain in close proximity and accessible to escorts [11]. In this context, a broad and complex repertoire of protective behaviors may supplement the habitat segregation strategy between males and females and be crucial for calf survival.

Acute reorientation was the most frequent behavior of the female to evade male harassment. In Hawaiʻi, calves exhibit significantly higher reorientation rates when in groups with multiple male escorts [5]. In Brazil, in a different context, a Bryde’s whale (Balaenoptera edeni) was observed frequently reorienting its swimming direction when near the potential danger posed by a vessel [26]. Thus, reorientation may be a behavior performed by female humpback whales in response to the threat posed by approaching males. However, these evasions from escorts can increase the risk of mother–calf separation, which poses a potential threat to the dependent calf.

The female repeatedly positioned her body to form a physical barrier between the calf and the males. Several cetacean species display similar protective behaviors during predation attempts by killer whales (Orcinus orca). Female gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) position themselves between their calf and predators, in addition to striking vigorously with their tails [12]. In similar situations, humpback mothers keep their calf close while exhibiting aggressive behaviors such as tail slaps and surface lunges directed at the orcas [14]. Odontocetes exhibit similar behaviors: traveling spinner dolphin (Stenella longirostris) mothers protect their calves by positioning them between themselves and another female [27], while female Amazon river dolphins (Inia geoffrensis) exhibit the same behavior during infanticide attempts [28]. In response to harassment from escort males, the female humpback whale brought the calf close to her body and used a pectoral fin to hold it on top of them while she moved. The use of pectoral fin in maintaining interindividual relationships has been described as a strategy to fight off predatory attacks by killer whales in humpback whales, southern right whales (Eubalaena australis) [13], and dolphin species [29]. However, we believe our record of the humpback mother’s pectoral fin use is related to calf protection, as the “Pectoral Fin Carry” and “Hug” behaviors create a safe space/barrier against lateral and underneath approaches from escorts. One variation of the “Hug” behavior involved the female protecting her calf by holding it against her ventrum at the surface, a behavior previously described in female southern right whales during the breeding season in Brazil [30]. In a different context, during predatory attacks by killer whales, gray whales have also attempted to protect their calves by holding them on top of their ventrum [13]. Ventral exposure at the surface has been reported in adult humpback whales when attacked by orcas, but not for the purpose of protecting a calf [13]. This pectoral fin protection of a calf may be unique to humpback whales due to their long pectoral fins, which can reach one-third of the individual’s total length [31].

Active behaviors, such as head and tail slaps, corroborate the intense energetic investment of escort males competing for the female [24,32]. Despite the mother’s protective strategies, she could not always ensure the complete protection of her calf. Infanticide attempts, aimed at inducing copulation with the postpartum female, have been observed in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) [33], Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) [34], Guiana dolphins (Sotalia guianensis) [35], and killer whales [36]. Although never documented in baleen whales, the “head calf lift” and “calf compression” behaviors we describe do not appear to be infanticide attempts, as the primary objective of the escort males is to approach the female, not to sever the mother–calf bond or eliminate the offspring.

The presence of male escorts in groups of lactating females imposes significant energy costs on humpback whale mother–calf pairs. Females with calves are more likely to be pursued by multiple males than females without calves [37]. As a result, these female–calf pairs spend significantly more time on the move and less time resting when accompanied by escorts, compared to groups without male escorts [5,37]. For growing calves, an average reduction of 10% in surface time is due to the presence of escorts [5] and can lead to an increase in metabolic cost, which impacts on the energy allocated to their development.

In response to this pressure, lactating females may adopt counterstrategies to mitigate harassment from competitive males. One such strategy is to allow association with a single accompanying male [5,37], a behavior that aligns with the bodyguard hypothesis [38]. Although a recent study suggested that the association of females with humpback whale calves was related to the social development of the calves [39], it is also plausible that aggregations of females with calves function as a strategy to dilute the mother’s individual vigilance [40] toward approaching males. This could increase the time available for rest and potentially optimize energy allocation for lactation and calf growth.

The protective behaviors exhibited by the mother reveal a novel function for the pectoral fins of humpback whales, with implications for maternal care strategies, and consequently calf survival. Nevertheless, the behavior of competing males demonstrates plasticity in their strategies for approaching reproductive females and highlights gaps in our understanding of the social dynamics of humpback whale reproduction. Finally, we emphasize that the mother’s protective behaviors using her pectoral fins were not clearly identifiable to the naked eye by vessel-based researchers, as these actions occurred while the whales were submerged. This highlights the importance of using drones for studying cetacean behavior, as this aerial perspective allows for the identification of behaviors not visible from the horizontal viewpoint of vessel-based observers [41,42].

5. Conclusions

We identified several maternal protective behaviors involving the pectoral fins of humpback whales, a previously undocumented function for this organ. The large size of their pectoral fins is a unique characteristic among cetaceans, and the use of these appendages for protection may be exclusive to the species. Describing novel behaviors in one of the most studied cetacean species reinforces the value of drones as a research tool, providing a unique perspective that allows for detailed descriptions of social interactions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ani15243610/s1, Table S1. present the frequency of behaviors performed by calf, female and escorts. Further supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/studies/S-BSST2101 (accessed on 28 August 2025). We present High resolution videos captured by drones to elucidate and facilitate understanding of the behaviors exhibited by the escort males and the mother–calf pairs. Video S1: Acute reorientation—A female humpback whale evading an escort with sharp turning angles. Video S2: Head-push submersion—A female pushing an escort underwater with her head, allowing her calf to move to her opposite side. Video S3: Pectoral fin carry—A female moving with her calf on her pectoral fin during an approach by escorts. Video S4: Hug—A female crossing her pectoral fins around her calf. Video S5: Head calf lift—An escort lifting the calf with its head during an approach toward the female. Video S6: Calf compression—An escort pressing the calf between himself and the female. Reference [24] is cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: B.M.R., M.C.C.M. and Y.L.P., Methodology: B.M.R. and L.A., Software: B.M.R. and L.A., Validation: B.M.R., M.C.C.M. and Y.L.P., Formal analysis: B.M.R. and L.A., Investigation: B.M.R., L.A. and M.C.C.M., Resources: M.C.C.M., Data curation: B.M.R. and L.A., Writing—original draft: B.M.R., L.A., M.C.C.M. and Y.L.P., Writing—review and editing: B.M.R., L.A., M.C.C.M. and Y.L.P., Visualization: B.M.R., M.C.C.M. and Y.L.P., Supervision: M.C.C.M., Project administration: M.C.C.M., Funding Acquisition: M.C.C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by is sponsored by Petróleo Brasileiro S.A.—PETROBRAS https://petrobras.com.br/en (accessed on 28 August 2025), Projeto Baleia Jubarte. BMR received a scholarship grant from the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado da Bahia (FAPESB), https://www.fapesb.ba.gov.br (accessed on 28 August 2025) and LA received a scholarship grant from the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), https://www.gov.br/capes/en (accessed on 28 August 2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the Brazilian legislation [43] and authorized by SISBIO license number 21489-15. The whales were approached at a minimum distance of 100 m and for a maximum duration of 30 min per group, less if their behavior indicated that they were avoiding the proximity of the boat.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Oftedal, O.T. Lactation in Whales and Dolphins: Evidence of Divergence between Baleen and Toothed Species. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 1997, 2, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockyer, C. Review of Baleen Whale (Mysticeti) Reproduction and Implications for Management. Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 2016, 6, 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, F.; Madsen, P.T.; Andrews-Goff, V.; Double, M.C.; How, J.R.; Clapham, P.; Ivashchenko, Y.; Tormosov, D.; Sprogis, K.R. Extreme Capital Breeding for Giants: Effects of Body Size on Humpback Whale Energy Expenditure and Fasting Endurance. Ecol. Modell. 2025, 501, 110994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapham, P.J.; Palsbøll, P.J.; Mattila, D.K.; Vasquez, O. Composition and Dynamics of Humpback Whales Competitive Groups in West Indies. Behaviour 1992, 122, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, R.; Sullivan, M. Associations with Multiple Male Groups Increase the Energy Expenditure of Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) Female and Calf Pairs on the Breeding Grounds. Behaviour 2009, 146, 1573–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smultea, M.A. Segregation by Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) Cows with a Calf in Coastal Habitat near the Island of Hawaii. Can. J. Zool. 1994, 72, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A.S.; Herman, L.M.; Pack, A.A.; Waterman, J.O. Habitat Segregation by Female Humpback Whales in Hawaiian Waters: Avoidance of Males? Behaviour 2014, 151, 613–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, F.; Botero-Acosta, N. Distribution and Behaviour of Humpback Whale Mother-Calf Pairs during the Breeding Season off Ecuador. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011, 426, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.C.A.; Morete, M.E.; Engel, M.H.; Freitas, A.C.; Secchi, E.R.; Kinas, P.G. Aspects of Habitat Use Patterns of Humpback Whales in the Abrolhos Bank, Brazil, Breeding Ground. Mem. Queensl. Museum 2001, 47, 563–570. [Google Scholar]

- Wedekin, L.L.; Neves, M.C.; Marcondes, M.C.C.; Baracho, C.; Rossi-Santos, M.R.; Engel, M.H.; Simões-Lopes, P.C. Site Fidelity and Movements of Humpback Whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) on the Brazilian Breeding Ground, Southwestern Atlantic. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2010, 26, 787–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righi, B.M.; Baumgarten, J.E.; Morete, M.E.; Souza, R.C.F.; Marcondes, M.C.C.; Sousa-Lima, R.S.; Teixeira, N.N.; Tonolli, F.A.S.; Gonçalves, M.I.C. Exploring Habitat Use and Movement Patterns of Humpback Whales in a Reoccupation Area off Brazil: A Comparison with the Abrolhos Bank. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2024, 40, e13139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett-Lennard, L.G.; Matkin, C.O.; Durban, J.W.; Saulitis, E.L.; Ellifrit, D. Predation on Gray Whales and Prolonged Feeding on Submerged Carcasses by Transient Killer Whales at Unimak Island, Alaska. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011, 421, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.K.B.; Reeves, R.R. Fight or Flight: Antipredator Strategies of Baleen Whales. Mamm. Rev. 2008, 38, 50–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, R.L.; Totterdell, J.A.; Fearnbach, H.; Ballance, L.T.; Durban, J.W.; Kemps, H. Whale Killers: Prevalence and Ecological Implications of Killer Whale Predation on Humpback Whale Calves off Western Australia. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2015, 31, 629–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.G.; Nieukirk, S.L.; Lemos, L.; Chandler, T.E. Drone Up! Quantifying Whale Behavior from a New Perspective Improves Observational Capacity. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, J. Observational Study of Behavior: Sampling Methods. Behaviour 1974, 49, 227–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, J. Behavioral Sampling Methods for Cetaceans: A Review and Critique. Mar. Mammal Sci. 1999, 15, 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, F.; Vivier, F.; Charlton, C.; Ward, R.; Amerson, A.; Burnell, S.; Bejder, L. Maternal Body Size and Condition Determine Calf Growth Rates in Southern Right Whales. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2018, 592, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: http://www.r-project.org (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Christiansen, F.; Dujon, A.M.; Sprogis, K.R.; Arnould, J.P.Y.; Bejder, L. Noninvasive Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Provides Estimates of the Energetic Cost of Reproduction in Humpback Whales. Ecosphere 2016, 7, e01468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, L.G.; Thums, M.; Hanson, C.E.; McMahon, C.R.; Hindell, M.A. Evidence for a Widely Expanded Humpback Whale Calving Range along the Western Australian Coast. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2018, 34, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittleborough, R.G. Puberty, Physical Maturity, and Relative Growth of the Female Humpback Whale, Megaptera novaeangliae (Bonnaterre), on the Western Australian Coast. Austr. J. Mar. Freshw 1955, 6, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friard, O.; Gamba, M. BORIS: A Free, Versatile Open-Source Event-Logging Software for Video/Audio Coding and Live Observations. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1325–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.S.; Herman, L.M. Aggressive Behavior between Humpback Whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) Wintering in Hawaiian Waters. Can. J. Zool. 1984, 62, 1922–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.I.C.; De Sousa-Lima, R.S.; Teixeira, N.N.; Morete, M.E.; De Carvalho, G.H.; Ferreira, H.M.; Baumgarten, J.E. Low Latitude Habitat Use Patterns of a Recovering Population of Humpback Whales. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2018, 98, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L.R.; Augustowski, M.; Andriolo, A. Occurrence, Distribution and Behaviour of Bryde’s Whales (Cetacea: Mysticeti) off South-East Brazil. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2016, 96, 943–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowans, S.; Würsig, B.; Karczmarski, L. The Social Structure and Strategies of Delphinids: Predictions Based on an Ecological Framework. Adv. Mar. Biol. 2007, 53, 195–294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bowler, M.T.; Griffiths, B.M.; Gilmore, M.P.; Wingfield, A.; Recharte, M. Potentially Infanticidal Behavior in the Amazon River Dolphin (Inia geoffrensis). Acta Ethol. 2018, 21, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudzinski, K.; Ribic, C. Pectoral Fin Contact as a Mechanism for Social Bonding among Dolphins. Anim. Behav. Cogn. 2017, 4, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.C.; Rodrigues, J.; Corrêa, A.A.; Groch, K.R. Comportamento de Pares de Fêmea- Filhote Eubalaena australis (Desmoulins, 1822) Na Temporada Reprodutiva de 2008, Enseada de Ribanceira e Ibiraquera, Santa Catarina, Brasil. Ens. Ciência Ciênc. Biol. Agrár. Saúde 2010, 14, 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Clapham, P.J.; Mead, J.G. Megaptera novaeangliae; Mamm. Species 1999, 604, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyack, P.; Whitehead, H. Male Competition in Large Groups of Wintering Humpback Whales. Behaviour 1983, 83, 132–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrtree, R.M.; Sayigh, L.S.; Williford, A.; Bocconcelli, A.; Curran, M.C.; Cox, T.M. First Observed Wild Birth and Acoustic Record of a Possible Infanticide Attempt on a Common Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus). Mar. Mammal Sci. 2016, 32, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Karczmarski, L.; Lin, W.; Chan, S.C.Y.; Chang, W.L.; Wu, Y. Infanticide in the Indo-Pacific Humpback Dolphin (Sousa chinensis). J. Ethol. 2016, 34, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nery, M.F.; Simão, S.M. Sexual Coercion and Aggression towards a Newborn Calf of Marine Tucuxi Dolphins (Sotalia guianensis). Mar. Mammal Sci. 2009, 25, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towers, J.R.; Hallé, M.J.; Symonds, H.K.; Sutton, G.J.; Morton, A.B.; Spong, P.; Borrowman, J.P.; Ford, J.K.B. Infanticide in a Mammal-Eating Killer Whale Population. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.E. Female Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) Reproductive Class and Male-Female Interactions During the Breeding Season. Ph.D. Thesis, Antioch University New England, Keene, NH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mesnick, S.L. Sexual Alliances: Evidence and Evolutionary Implications. In Feminism and Evolutionary Biology; Gowaty, P.A., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1997; pp. 207–260. ISBN 9781461559856. [Google Scholar]

- McGovern, B.; Machernis, A.F.; McCordic, J.A.; Olson, G.L.; Sullivan, F.A.; Barber-Meyer, S.M.; Currie, J.J.; Stack, S.H. Prevalence, Composition, and Behaviour of Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) Groups Containing Multiple Mother–Calf Pairs in East Australia. Aquat. Mamm. 2025, 51, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caine, N.G.; Marra, S.L. Vigilance and Social Organization in Two Species of Primates. Anim. Behav. 1988, 36, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidrobo, A.M.V. Uso de Drones Para El Estudio de Cetáceos: Perspectivas En El Estudio Ecológico de Ballenas y Delfines, y Potencial Aplicación En La Costa Norte Del Ecuador. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito, Ecuador, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pedrazzi, L.; Naik, H.; Sandbrook, C.; Lurgi, M.; Fürtbauer, I.; King, A.J. Advancing Animal Behaviour Research Using Drone Technology. Anim. Behav. 2025, 222, 123147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources. IBAMA Normative Ordinance No. 117, of December 26, 1996. Brasília: DOU Official Gazette. Published in the D.O.U. of December 27, 1996. 1996. Available online: https://www.ibama.gov.br/component/legislacao/?view=legislacao&legislacao=94100 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).