Simple Summary

Guardians of the approximate 528 million companion dogs globally face an array of dog food choices. This is increasing with efforts to create dog food that involves less harm to other animals and a lower environmental impact, relative to conventional dog food. This survey of over 2600 dog guardians aimed to discern important factors guiding dog guardians’ dog food purchasing decisions—regarding both current diets and sustainable alternatives. We found that over 84% of respondents currently fed either conventional or raw meat-based dog food, but over 43% found at least one of the more sustainable alternative dog food options acceptable. Willingness to purchase the alternatives hinged most commonly upon the nutritional soundness of the products, with cultivated meat-based dog food proving the most popular alternative. Labels/packaging was the most frequently selected source of information used by guardians to make dog food decisions. Amongst the human and dog demographic variables analyzed, human diet and dog diet were the factors most commonly associated with current and potential purchasing decisions, as well as with information sources used. Our sample was not representative of the general population in certain respects. To minimize any resultant bias effects, we used regression analyses for the calculation of all association estimates.

Abstract

Interest in more sustainable diets for the global population of 528 million companion dogs is steadily increasing, encompassing nutritionally sound cultivated meat, vegan, and microbial protein-based dog foods. Factors driving these alternative dog foods include lower impacts on the environment, fewer welfare problems related to intensively farmed animals and wild-caught fish, and potentially superior canine health outcomes, relative to conventional meat-based dog food. Through a questionnaire with 2639 responses, this study aimed to gain insights into dog guardians’ current feeding patterns and dog food purchasing determinants, acceptance of more sustainable dog diets, and sources of information used for decisions about dog diets. Key results included that 84% (2188/2596) of respondents currently fed either conventional or raw meat-based dog food. More than 43% (936/2169) of this group of respondents who answered found at least one of the more sustainable alternative dog foods acceptable, with purchases of these alternatives hinging most commonly upon the nutritional soundness of the products. Cultivated meat-based dog food was the most popular alternative (selected by 24%, 529/2169), followed by vegetarian (17%, 359/2169), insect-based (16%, 336/2169), and vegan (13%, 290/2169) dog food. The top three information sources used to make decisions regarding dog diets were labels/packaging (selected by 42% of all respondents, 1080/2596), scientific articles/books (38%, 989/2596), and business webpages (35%, 900/2596). Numerous human and dog demographic variables had impacts on current diets, acceptance of alternative diets, and information sources used. Notably, human diet and dog diet were the factors most commonly associated with current and potential purchasing decisions, as well as with information sources used. For instance, greater reductions by guardians in the consumption of animals were associated with greater acceptance of more sustainable dog diets. It should be noted that, due to the reliance on convenience sampling and the overrepresentation of respondents from the UK, of female guardians, of respondents with higher education, and of vegan guardians, the reported relative frequencies of subgroups were not fully representative of the global dog guardian population. Association estimates were based on regression analyses to minimize any resultant bias effects.

1. Introduction

Dogs represent the most widely kept companion animal globally, with recent data estimating the worldwide companion dog population in 2024 at approximately 528 million, followed by companion cats at 476 million [1]. Other sources demonstrate similar population sizes [2]. The prevalence of companion dogs continues to increase internationally; for example, in Europe, there was an estimated 40% rise in households owning dogs between 2010 and 2022 [3], while China experienced an average annual growth of almost 10% in its pet dog population from 2018 to 2022 [4]. As a result, the global dog food industry was valued at over USD 41.4 billion in 2022, with projections indicating an annual growth rate of 5.1% through 2030 [5]. Despite this growth, concerns have recently emerged regarding the impact of traditional meat-based pet foods on (1) canine health, (2) environmental sustainability, and (3) the welfare of intensively farmed and wild-caught animals.

Health-related reservations primarily focus on the perceived low quality of some pet foods. These concerns arise from the incorporation of animal by-products (ABPs) sourced from slaughterhouses [6], the potential presence of harmful toxins [7], and the frequency of product recalls [8]. Additionally, the highly processed nature of many pet foods has raised concerns about nutrient depletion [9]. From an environmental perspective, the use of ABPs in conventional pet foods supports industrial animal agriculture, which is known to be a major driver of deforestation, habitat loss, water contamination, extensive land use, and climate change [10,11,12]. Notably, a review has indicated that pet food production in the United States accounts for 25–30% of the environmental impacts associated with animal agriculture overall [13,14]. Ethically, feeding dogs meat or fish necessitates the killing of other animals—unless cultivated meat-based dog food is utilized. Studies suggest that pet owners typically exhibit greater empathy towards animals and a stronger commitment to animal welfare compared to the general population [15], and there is a higher prevalence of vegetarians and vegans among pet owners [16]. This situation creates a moral inconsistency, as individuals who care deeply for their pets while feeding them meat-based diets may simultaneously contribute to the harm of other animals—a phenomenon described as the “vegetarian’s dilemma” [17] or the “animal lover’s paradox” [18]. Indeed, various theoretical frameworks, such as meat-related cognitive dissonance (MRCD), have been established to better understand how consumers make dietary purchasing decisions [19].

It is frequently argued that conventional meat-based dog food utilizes only the ABPs that are unfit for human consumption, thereby mitigating the worst of the welfare and environmental impacts [20]. However, Knight [10] has shown that nearly half (47.4%) of animal-derived ingredients in dog food sold in the US are actually suitable for human consumption, and that the remaining ABP fraction is associated with greater, rather than fewer, farmed animal welfare and environmental impacts when considering companion animal diets exclusively. Furthermore, there are indications that continued reliance on slaughterhouse ABPs for dog food could result in shortages, as ABPs are increasingly being diverted for renewable energy production [21]. In response to these health, environmental, farmed animal welfare, and ethical challenges, a growing array of alternative dog food products is now available.

1.1. Sustainable Alternatives to Conventional Meat-Based Dog Food

Nutritionally sound vegan dog food is the main genuinely sustainable option currently widely available for canine diets. While stakeholders frequently cite insect-based pet food as another sustainable alternative, unresolved questions regarding insect sentience [22] mean that welfare and ethical concerns associated with the use of farmed animals remain of concern. Furthermore, arable agriculture generally imposes a lower environmental burden compared to insect farming [23,24]. Other promising sustainable alternatives include dog foods produced from cultivated meat and fermented microbial proteins. The market for cultivated meat-based pet food is still in its infancy, with a limited batch of the first product becoming available in London, UK, in early 2025 [25]. Microbell represents the first commercially available dog food produced using fermented microbial proteins [26]. These emerging alternative pet food proteins have the potential to significantly reduce the environmental impacts associated with pet food consumption. However, regulatory barriers, such as unclear guidance and burdensome processes (particularly for small companies) remain, and need to be addressed [27]. Moreover, to tackle consumer concerns and misinformation surrounding these alternatives, some authors have urged governments and media organizations to run communication campaigns that inform guardians on the environmental and health impacts of different pet food types [28]. In contrast, the vegan dog food sector is already well established, valued at over USD17 billion and projected to exceed USD44 billion by 2032 [29]. Numerous companies currently offer nutritionally complete vegan dog foods (https://sustainablepetfood.info/suppliers, accessed on 7 October 2025), with South America leading the market and the highest anticipated growth in the Asia-Pacific region [29].

An expanding body of research is demonstrating the healthfulness of nutritionally complete vegan or vegetarian diets for dogs. As of September 2025, eleven studies had demonstrated good health outcomes associated with such diets [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40], along with one systematic review [41]. Collectively, these twelve studies have reported no adverse effects—and sometimes health benefits. Veterinary and industry organizations are beginning to issue guidance on the safe transition to and maintenance of nutritionally sound vegan diets in dogs. For example, UK Pet Food [42] has released a fact and guidance sheet on vegan diets for dogs and cats, and the British Veterinary Association has issued advice on feeding dogs nutritionally complete vegan diets [43]. Both organizations support the use of these diets, when formulated to be nutritionally sound. Because of their relatively wide availability, and good dog health outcomes, this study focuses primarily on nutritionally sound vegan dog diets as the main alternative sustainable option.

Although recent scientific investigations into dog feeding practices and the factors influencing dog food purchasing decisions have advanced understanding of these aspects (e.g., [16,44,45,46,47]), they have provided limited insight into the willingness of dog guardians to adopt more sustainable diets, or the specific attributes required for these diets to be accepted. Such knowledge would enable the pet food industry to better address the diverse needs and preferences of different demographic groups of dog guardians and would assist veterinarians in advising their clients. Therefore, the present study was designed to investigate these additional aspects.

1.2. Research Questions

Three overarching topics were investigated: (1) existing feeding patterns and purchasing determinants among dog guardians; (2) acceptance by dog guardians of more sustainable dog diets; and (3) sources used by dog guardians to obtain information about dog diets. We analyzed these topics using the following specific research questions (RQs):

- (1)

- Current diets:

- What feeding patterns exist among dog guardians?

- What factors do dog guardians find important when choosing dog diets?

- (2)

- Alternative diets:

- What proportion of dog guardians currently feeding meat-based (conventional or raw) dog food would realistically be willing to choose more sustainable alternatives?

- For those willing, what characteristics would the alternative diets need to provide in order to be chosen?

- (3)

- Information sources: Where do dog guardians source information about dog diets from?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Design and Distribution

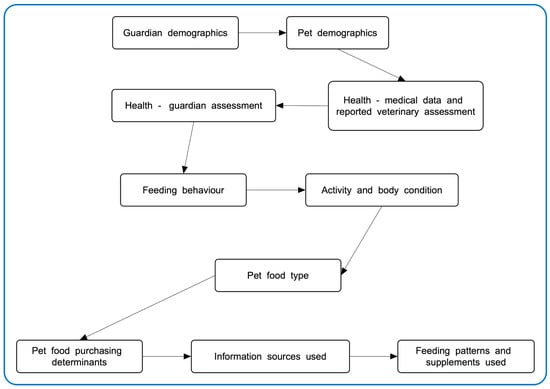

Between May and December 2020, a quantitative questionnaire was administered via the Online Surveys platform (https://www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk, accessed on 14 October 2025) to gather data from dog guardians internationally regarding their current feeding practices, acceptance of more sustainable dog diets, and information sources used for dog diet decisions. After conducting a pilot study with 25 participants, the survey was revised—primarily by reordering questions—to reduce the risks of unconscious bias affecting responses. Specifically, items related to dependent variables were placed before those concerning independent variables, except for demographic questions, which remained at the beginning. The finalized survey instrument contained 37 principal questions organized into 10 sections, as illustrated in Figure 1. Depending on their responses, some participants received additional follow-up questions. The majority of questions were multiple-choice, frequently allowing respondents to select all applicable options, resulting in predominantly nominal data. The full survey is accessible on the OSF platform (https://osf.io/nbepu/, accessed on 14 October 2025).

Figure 1.

Sections of the questionnaire. Source: Knight et al. [37]. Note: The four sections connected to health, body condition, and behavior are not relevant to this study and so are excluded from this analysis; see Knight et al. [37,40,48] and Knight and Satchell [49] for analysis of these results.

Distribution of the survey occurred through social media channels, including specialized groups for dog enthusiasts. Paid Facebook advertisements were utilized to increase reach, and volunteers assisted in disseminating the survey. Targeted recruitment was employed for specific companion animal diet groups to ensure adequate sample sizes for statistical analysis. The choice of using Online Surveys as the survey platform was informed by its widespread adoption, with over 88% of UK universities, including our University of Winchester, using the platform in 2019 [50]. Participants within multi-dog households were instructed to select just one dog about whom to answer, and to base their responses on experiences from the preceding year. For households with both dogs and cats, respondents were asked to randomly select which animal to focus on, using the parity of their birth month as a guide (even-numbered months for dogs). Those whose dogs were on therapeutic diets were directed to reflect on their practices during the year before the therapeutic diet commenced.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

The four sections connected to health, body condition, and behavior were excluded from the analysis for the purpose of this study; see Knight et al. [37,40,48] and Knight and Satchell [49] for analysis of these results. Respondents not agreeing to the first screening question (n = 3) were removed from the data. The analysis of the remaining dog-based data is outlined in the following. For the analysis of the cat-based data, see a forthcoming study by Mace et al. [51].

Inferential statistics were utilized to analyze potential differences between both human and dog demographic subgroups and participant responses regarding RQs 1–3. Each research question was analyzed based on the estimation of multiple (generalized) linear regression models [52]. Linear regression models were estimated for (quasi-)metric response variables. Logistic regression models were estimated for binary response variables, as linear models are not suitable for such data [52]. All of the utilized category scores, outlined below, were created based on an intuitive grouping of the respective items.

For RQ1a, two logistic models were estimated on the binary questions “is the dog fed vegan or meat-based food?” and “is the dog fed raw meat or a conventional meat-based diet?” The former model was only estimated on the subgroup of vegan dog guardians because 303 out of 332 respondents feeding vegan dog diets were vegan themselves.

For RQ1b, four linear models were estimated on four quasi-metric category scores, each reflecting the share of individual items that each respondent stated were purchasing determinants for their current dog diet. The categories comprised Pet Focus I (with individual items ‘health and nutrition,’ ‘palatability,’ ‘diet quality’, i.e., pet-focused items directly influencing pet welfare), Pet Focus II (items ‘naturalness,’ ‘freshness,’ ‘diet reputation’, i.e., pet-focused items not directly influencing pet welfare), Personal Focus (items ‘price,’ ‘convenience,’ ‘social/cultural’), and Personal Values (items ‘food animals,’ ‘sustainability’). For RQ2a, six logistic models were estimated on the individual items ‘vegan,’ ‘fungi-based,’ ‘algae-based,’ ‘vegetarian,’ ‘cultivated meat,’ and ‘insect-based.’

For both RQ2b and RQ3, four logistic models were estimated on four category scores, each reflecting the information if at least one of the respective items was selected. The categories for RQ2b comprised Pet Focus I (items ‘health,’ ‘palatability,’ ‘quality,’ ‘nutritional soundness’), Pet Focus II (items ‘naturalness,’ ‘freshness,’ ‘reputation’), Personal Focus (items ‘price,’ ‘convenience,’ ‘social/cultural’), and Personal Values (items ‘sustainability,’ ‘animal welfare for cultivated meat,’ ‘animal rights for cultivated meat’). For RQ3, the categories comprised Product-Specific (items ‘label/packaging,’ ‘company webpage’), Vet/Pet Care (items ‘veterinarians,’ ‘other vet clinic staff,’ ‘pet store staff,’ ‘pet paraprofessionals’), Media/Literature (items ‘scientific literature,’ ‘media reports,’ ‘non-company webpage,’ ‘other books’), and Social Media (items ‘special interest group online,’ ‘general social media’).

All models controlled for the following sets of independent variables, with the reference characteristics indicated. Categories with a sufficient number of respondents and/or positioned at the start or end of ordinal variable categories were chosen as reference characteristics. Human demographic variables comprised the respondent’s dietary category (reference ‘omnivore’), categorized age (‘18–29’), gender (‘female’), education (‘doctorate’), potential occupation in the pet or veterinary industry (‘no’), income level (‘low’), geographical region (‘UK’), and type of residence (‘urban’). Dog demographic variables comprised the dog’s diet (‘conventional meat-based’), whether the dog was currently fed a medical diet (‘no’), age (‘0–4 years’), sex and neuter status (‘female, spayed’), breed size (‘toy’), if the dog was a working dog (‘no’), and his/her exercise level (‘normal’). As stated above, the human and dog diet effects were not estimated for all RQ1a models due to the high number of vegan-fed dogs with vegan guardians.

Human diet and dog diet were both substantially correlated with each other and with the other human demographic independent variables. To prevent this ‘multicollinearity’ from negatively affecting model estimations, the effects of human diet and dog diet were each estimated in separate regression models, which exclusively controlled for the additional dog characteristics. The resulting human and dog diet estimates are always reported side-by-side with all other estimates but are highlighted through gray-shaded areas in all figures to reflect this separated estimation scheme.

To account for the multitude of individual tests, multiple testing correction after Bonferroni-Holm [53] was applied individually for every model. Model assumptions were visually checked based on the distribution of model residuals. No relevant deviations from the assumptions could be observed. Additionally, we calculated the area under the curve (AUC) values for logistic regression models, which were calculated on a randomly selected 20% hold-out test set after re-estimating each model on the remaining 80% training set. The AUC values for RQ1a were 0.72 for the ‘vegan vs. meat-based’ model and 0.61 for the ‘conventional vs. raw meat’ model. Other AUC values ranged between 0.62 and 0.70 (RQ2a), 0.58 and 0.65 (RQ2b), and 0.61 and 0.66 (RQ3). The R2 values for the RQ1b linear regression models ranged from 0.02 to 0.06. AUC values below 0.7 are generally considered to indicate poor discrimination [54]. No such hard threshold is established for R2 values [55]. While some of our AUC and R2 values were very low, this was anticipated given our focus on modeling complex personal values and interests based almost exclusively on sociodemographic factors. In such social science research settings, low goodness-of-fit values do not necessarily indicate an uninterpretable model, but observed effect patterns and significances can and should still be interpreted [55].

Microsoft Excel was used to supply descriptive statistics. Inferential analyses were conducted using the open-source statistical software R version 4.5.0 [56]. Regression models were estimated with function “gam” from package “mgcv” version 1.9-1 [57]. AUC values were calculated with function “calc_auc” from package “plotROC” version 2.3.3 [58].

2.3. Research Ethics

This study adhered to the University of Winchester research ethics policy [59] and was approved under reference RKEEC200304_Knight. Prior to accessing the questionnaire, participants were provided with information regarding the study’s objectives, how the data they provide would be stored/used, the voluntary nature of any participation, who was carrying out the study, and contact details of who to contact regarding any ethical issues or remaining queries. The participants were then required to provide written confirmation that they were at least 18 years old and consented to participate, by ticking boxes to this effect. Additionally, respondents affirmed that they would answer questions based on one dog or cat they had cared for over the previous year. Full details can be found on the questionnaire, which, along with the dataset generated from this research, the mapping between dependent variables and questionnaire items, and the R code utilized for the statistical analyses, is publicly available at https://osf.io/nbepu (accessed on 14 October 2025). Perplexity (https://www.perplexity.ai) was used on 30 May 2025 to re-phrase parts of the introduction, methodology, and limitations sections of the paper. This was to avoid self-plagiarism of a related study by the same authors [51], and to prevent verbatim repetition between certain parts of the abstract and conclusions. The prompt used on Perplexity was “Can you re-write (paraphrase) in the same academic tone the following passage please? It’s to avoid self-plagiarism.” An example included changing this sentence in the introduction:

“The number of households with a dog continues to rise globally; for instance, across Europe, between 2010 and 2022, there was roughly a 40% increase in the number of households with a dog [3] and China’s pet dog population grew by 9.8% each year between 2018 and 2022 [4]”

to

“The prevalence of companion dogs continues to increase internationally; for example, in Europe, there was an estimated 40% rise in households owning dogs between 2010 and 2022 [3], while China experienced an average annual growth of almost 10% in its pet dog population from 2018 to 2022 [4]”.

3. Results

Data cleaning included the removal of respondents (a) not agreeing to the first screening question (n = 3), (b) stating they played no role in pet food decisions (n = 16), and (c) leaving all questions blank after the demographics section (n = 27). Following this, there were 2596 respondents. Additionally, for the regression-based analyses of associations of data with human and dog demographic characteristics, pregnant (n = 3) and lactating (n = 3) dogs were excluded, due to their non-standard nutritional requirements, leaving 2590 respondents. This section first describes the human and dog demographic characteristics of the remaining participants, before proceeding to explore the three key topics outlined in Section 1.2. Each subsection comprises descriptive statistics followed by the most important results from the regression modeling of associations between human/dog demographic characteristics and the variables of interest.

In reporting these results, we have applied the following conventions:

- Effect = significant association after multiple testing correction.

- Trend = significant association prior to multiple testing correction.

- No trend = no significant association prior to multiple testing correction.

- Explorative tendency = an association arising from explorative analyses only.

- Tendency = general pattern.

Only the most important results—effects and particularly noteworthy trends—are outlined below; comprehensive results are supplied within Supplementary Tables S1–S3.

3.1. Human and Dog Demographic Characteristics

In terms of dog guardian demographics, 91.6% (2377/2596) of respondents were female; 71.6% (1858/2596) were from the UK; 80.1% (2079/2596) had some experience of college-/university-level education; and 64.3% (1670/2596) stated they had a ‘Medium’ level of income relative to ‘Low’ (14.8%, 384/2596), ‘High’ (13.9%, 360/2596), and ‘Prefer not to answer’ (7.0%, 182/2596). There was a fairly even spread between the ages of 20 and 69, with the most represented age range being 50–59 (23.0%, 596/2596). Similarly, 35.7% (928/2596) lived in an urban environment, but around 32.0% lived in both rural and equally urban/rural areas (32.0%, 830/2596; 31.7%, 823/2596, respectively). Moreover, 40.2% (1044/2596) had a standard omnivore diet. Additionally, 81.4% of respondents (2114/2596) did not work in the pet care industry, as a veterinarian, veterinary nurse/technician, animal trainer, nor animal breeder. Table 1 summarizes additional human demographic information.

Table 1.

Distribution of dog guardian demographic characteristics (n = 2596 in each category).

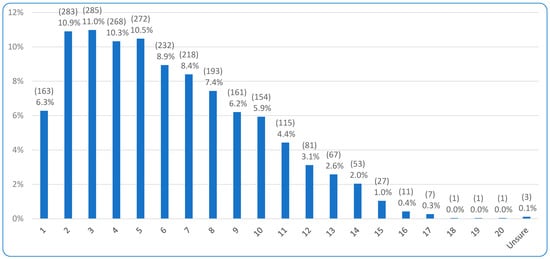

In terms of dog demographics, 98.6% (2559/2596) stated their dog was a companion animal rather than working animal. Figure 2 demonstrates the age ranges of the animals; age 3 was the most common age, selected by 11.0% of respondents (285/2596), with ages 2, 4, and 5 also represented by over 10% of respondents. The vast majority of dogs were neutered (78.2%, 2028/2596), which equated to 81.8% of female dogs (1001/1224) and 74.9% of male dogs (1027/1372). Additionally, almost all dogs (95.9%, 2489/2596) did not have specific high energy requirements (e.g., high levels of exercise, lactating, or pregnant), and 95.2% (2472/2596) were not on a prescription diet. Indeed, 94.2% (2446/2596) of respondents stated their dog was either ‘Healthy’ (61.6%, 1600/2596) or ‘Generally healthy’ (32.6%, 846/2596). Additionally, there was a wide distribution of small (20.1%, 521/2596), medium (38.8%, 1008/2596), and large (34.2%, 889/2596) dogs, along with a few giant (4.4%, 113/2596) and toy (2.5%, 65/2596) dogs.

Figure 2.

Distribution of dog ages (n = 2596).

3.2. Current Feeding Patterns and Purchasing Determinants

3.2.1. Current Feeding Patterns

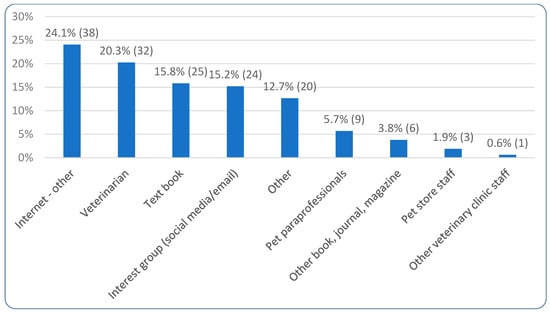

Table 2 demonstrates the diets primarily fed to the dogs, with ‘Meat-based—conventional’ comprising a majority at 52.3% (1359/2596), followed by raw meat-based diets (31.9%, 829/2596) and vegan diets (12.8%, 333/2596). Table 3 demonstrates where guardians obtain the majority of their dog food, with ‘Direct from manufacturer’ being selected most commonly by 25.6% (664/2596). Table 3 further highlights how commercial dog food comprised between 75% and 100% of the diet of nearly three quarters (71.1%, 1845/2596) of respondents’ dogs. It also highlights how the diets of respondents’ dogs were over 50% homemade in 9.8% (254/2596) of cases. Echoing this, the same table displays how up to 10.9% (285/2596) of respondents may be using homemade food as dog food, while ‘Commercial dry kibble’ is used most commonly by 37.6% (976/2596). When specifically asked if homemade food comprised more than half of their animals’ diets, 14.0% (364/2596) said ‘Yes.’ Of these 364 respondents, less than half (43.4%, 158/364) used a recipe, while 56.6% (206/364) did not. Figure 3 displays the sources for the recipes among those using a recipe, with ‘Internet’ being the most common (24.1%, 38/158).

Table 2.

Distribution of current dog diets (n = 2596) and acceptance of more sustainable alternative diets among those (n = 2169) currently feeding conventional/raw meat-based dog food.

Table 3.

Distribution of source of dog food purchases, type of dog food used, and percentage of commercial dog food used (n = 2596 in each category).

Figure 3.

Distribution of sources of homemade dog food recipes (n = 158).

‘Twice daily’ was the most common frequency of daily feeding (73.6%, 1910/2596), followed by ‘Once daily’ (11.9%, 310/2596), ‘Three times daily’ (8.2%, 213/2596), ‘Food is always available’ (4.3%, 112/2596), and ‘Other’ (2.0%, 51/2596). Common answers for people selecting ‘Other’ included 4–6 times a day and references to their dog ‘working’ for their food or no meals per se with food allowances instead being incorporated into training. Just under half (48.4%, 1256/2596) weighed the food given daily.

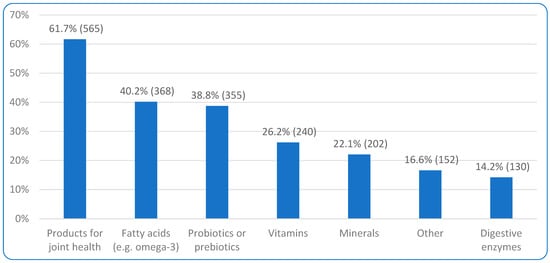

Over 90% (91.3%, 2371/2596) fed treats/snacks/scraps to their dog. Table 4 displays the frequencies of these with ‘More than once a day’ being selected by almost half of the respondents (48.9%, 1160/2371). The most common treat given was ‘vegetables or fruit’ (56.6%, 1342/2371), as displayed in Table 4. Over 60% (63.9%, 1658/2596) did not give their dog any supplements. Of the 36.1% (938/2596) who did give supplements, 11.0% (103/938) gave amino acids. When asked which, common responses included YouMove Plus (Glucosamine), Vegedog supplement, incorporated into dog food bought, taurine, lysine, L-Carnitine, DL-methionine, and tryptophan. The other supplements given to respondents’ dogs are summarized in Figure 4.

Table 4.

Distribution of respondents’ use of dog treats (n = 2371 in each category).

Figure 4.

Distribution of dietary supplements given to dogs (n = 916). Note: Multiple responses were possible; thus, the percentages and counts represent the proportion of all respondents selecting each answer option.

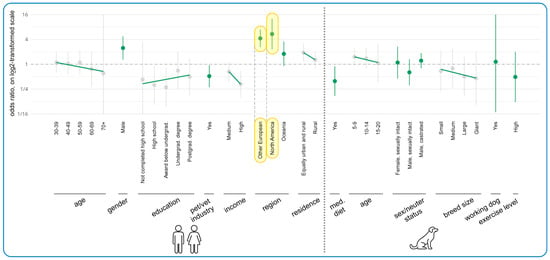

Figure 5 displays the results of the regression modeling regarding associations between human and dog demographics and likelihood of currently feeding dogs vegan diets. This model only included vegan guardians as of the total 332 guardians feeding a vegan diet, 91.3% (303/332) were vegan themselves. In relation to human demographics, the most apparent tendencies concerned region, gender, working in the pet/vet industries, education level, and income. North Americans had a 441% (Odds Ratio = +441%, 95% Confidence Interval: [+129%, +1180%], p = 0.0051), and Other Europeans (i.e., excluding UK) a 324% (OR = +324%, CI: [+161%, +591%], p < 0.0001), increased likelihood of feeding their dogs vegan, relative to those in the UK. These both constituted effects. Males likewise had a 148% increased chance of feeding their dogs a vegan diet relative to females; this constituted a trend (OR = +148%, CI: [+30%, +374%], p = 0.2313).

Figure 5.

Logistic regression results on the associations between human/dog demographic characteristics and the likelihood of currently feeding vegan diets to dogs, relative to the reference characteristics for each group. Note: Vegan dog diets were almost exclusively (91.3%) fed by people who were vegan themselves. As this association was so strong, this regression analysis was run using only vegan respondents. The reference characteristics for these humans and dogs were, respectively: (human) aged 18–29, female, doctoral degree, not in pet/vet industry, low income, UK- and urban-based; (dog) no medical diet, aged 0–4, female, spayed, toy size, a companion dog, and normal exercise levels. Effects are depicted as odds ratios, including 95% confidence intervals (not corrected for multiple testing). Effects that are significant after multiple testing correction are highlighted with yellow bubbles. Individual estimated effects of ordinal variables are grayed out in favor of an additional linear trend line.

In contrast, relative to not working in the pet/vet industries, working in such industries reduced the chance of feeding dogs a vegan diet by 49% (OR = −49%, CI: [−72%, −4%], p > 0.9999), and high income by 67% relative to low income (OR = −67%, CI: [−84%, −31%], p = 0.1249). These both constituted trends. Relative to having a doctorate, completion of high school and another award below undergraduate degree also reduced the chances of feeding dogs a vegan diet by 69% (OR = −69%, CI: [−90%, −4%], p > 0.9999) and 72% (OR = −72%, CI: [−91%, −19%], p = 0.6641), respectively. These both constituted trends.

In relation to dog demographics, the only noteworthy tendency was dogs progressing onto a medical diet being 61% less likely to be fed vegan than those not progressing onto medical diets (OR = −61%, CI: [−83%, −11%], p = 0.8503). This constituted a trend. See Supplementary Figure S1 for the impact of human and dog demographics on the likelihood of guardians to feed their dogs a raw meat diet.

3.2.2. Current Diet Purchasing Determinants

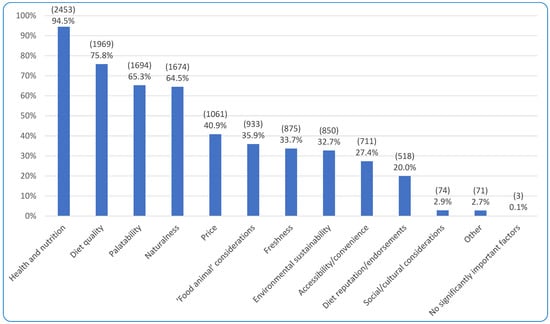

The vast majority of respondents (95.9%, 2489/2596) were the primary decision maker for pet food purchases with 4.1% (107/2596) playing a lesser role. Figure 6 portrays the most commonly selected factors of importance when choosing a dog food, with ‘Health and nutrition’ being the most popular option (selected by 94.5% of respondents, 2453/2596). When asked which health/nutritional factors were specifically important among these 94.5% of respondents, 90.1% (2211/2453) selected ‘Maintenance of pet health,’ 73.3% (1799/2453) selected ‘Nutritional soundness,’ 39.5% (968/2453) ‘Life stage suitability,’ 10.5% (258/2453) ‘Performance on diet,’ and 1.9% (47/2453) ‘Other.’ Examples of ‘Other’ included whether allergens were present, effect on bowels/stools, and safety (no recalls). When asked if there were any particular nutrients these respondents wanted included in pet food, 76.5% (1348/1763) stated ‘No’ and 23.5% (415/1763) stated ‘Yes.’ From the 412 respondents providing qualitative details following their ‘Yes’ response, common responses included all essential nutrients, meeting/exceeding FEDIAF-required levels, B12, L-carnitine, taurine, omega oils, glucosamine, chondroitin, probiotics, prebiotics, and vitamin D.

Figure 6.

Distribution of current dog food purchasing determinants. Note: Multiple responses were possible; thus, the percentages and counts represent the proportion of all respondents (n = 2596) selecting each answer option. The ‘Other’ responses (2.7%, n = 71) comprised, for instance, ‘WSAVA standards compliant’, whether the food is vegan/organic, and avoiding allergens.

Of the 20.0% (518/2596) of respondents selecting ‘Diet reputation/endorsements’ as important (Figure 6), 510 answered the question about which endorsements they would like. A good reputation without specific endorsement was selected by 59.8% (305/510) of respondents. ‘Endorsement by veterinarians’ was selected by 37.5% (191/510), ‘Endorsement by others’ by 26.7% (136/510), and ‘Endorsement by other veterinary staff’ by 9.6% (49/510). ‘Endorsement by others’ was elaborated upon by 121 respondents; common answers included the ‘All about dog food’ website, animal behaviorists, animal nutritionists, breed experts, fellow dog guardians (same breed), others experienced with the way respondents’ dogs are fed (e.g., raw, vegan), academic researchers, WAVSA (World Small Animal Veterinary Association).

Of the 35.9% (933/2596) of respondents selecting considerations about ‘food’ animals as an important factor in dog food purchases (Figure 6), 916 clarified further by selecting more specific considerations. ‘The welfare of “food” animals’ was selected by 83.0%, (760/916), ‘The rights of “food” animals’ by 60.4% (553/916), and ‘Other’ by 4.5% (41/916). Of the 2.9% (74/2596) selecting ‘Social or cultural considerations’ as an important factor in pet food purchases, 71 clarified further; the most common concern was ‘Country of origin of ingredients or finished product’ (70.4%, 50/71), followed by ‘Employment of farmers/workers’ (43.7%, 31/71). ‘Social or cultural considerations’ was selected by 32.4% (23/71) and ‘Other’ by 11.3% (8/71).

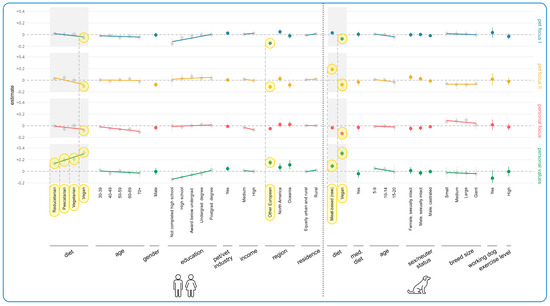

The results of the regression modeling of associations between human and dog demographics and current purchasing determinants are shown in Figure 7. All human demographics other than residence had some impact, especially guardian diet, region, and age. In terms of guardian diet, there was a decreasing tendency of importance of Pet Focus I, Pet Focus II, and Personal Focus with decreasing levels of animal product consumption. This constituted an effect for vegans relative to omnivores in each of these categories (Pet Focus I: Estimate = −0.06, CI: [−0.08, −0.03], p = 0.0049); Pet Focus II: Estimate = −0.10, CI: [−0.14, −0.07], p < 0.0001); Personal Focus: Estimate = −0.08, CI: [−0.11, −0.05], p < 0.0001), and a trend for pescatarians in the Personal Focus category (Estimate = −0.06, CI: [−0.10, −0.01], p > 0.9999). Supplementary Figure S2 shows this applied similarly across all items for Pet Focus I and Pet Focus II. But the reverse tendency was evident for the social/cultural subitem of the Personal Focus category, i.e., an increasing level of importance as animal products were reduced. This demonstrates that the aforementioned decreasing tendency on the main figure only applied to price and convenience subitems for the Personal Focus category. In contrast, for the Personal Values category, there was a clear increasing tendency in how important this factor became in decisions about pet food with decreasing animal consumption. Relative to omnivores, all dietary categories rated Personal Values as more important, and these all constituted effects (vegan: Estimate = +0.32 (CI: [+0.28, +0.36], p < 0.0001); vegetarian: Estimate = +0.21, CI: [+0.16, +0.26], p < 0.0001); pescatarian: Estimate = +0.19, CI: [+0.13, +0.26], p < 0.0001); reducetarian: Estimate = +0.13, CI: [+0.10, +0.17], p < 0.0001). Supplementary Figure S2 shows this was similar across all subitems.

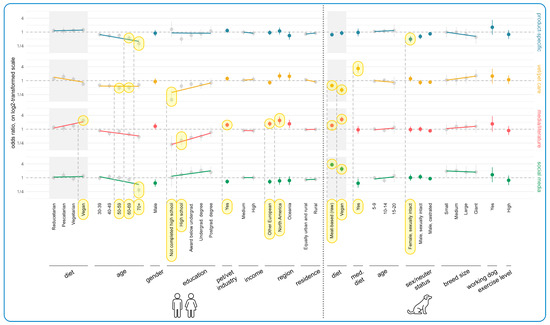

Figure 7.

Linear regression results on the associations between human/dog demographic characteristics and current dog food purchasing determinants, relative to the reference characteristics for each group. Note: The reference characteristics for these humans and dogs were, respectively: (human) omnivore, aged 18–29, female, doctoral degree, not in pet/vet industry, low income, UK- and urban-based; (dog) meat-based (conventional), no medical diet, aged 0–4, female, spayed, toy size, a companion dog, and normal exercise levels. The right y-axis purchasing determinant categories comprise the following subitems: Pet Focus I (health and nutrition, palatability, diet quality), Pet Focus II (naturalness, freshness, diet reputation), Personal Focus (price, convenience, social/cultural aspects), and Personal Values (concerns about ‘food’ animals or sustainability). Each dependent variable (e.g., Pet Focus I) comprises a score between 0 and 1, reflecting the share of its underlying set of items (see Figures S2 and S3) that respondents ticked in the questionnaire. Effects are depicted including 95% confidence intervals (not corrected for multiple testing). Effects that are significant after multiple testing correction are highlighted with yellow bubbles. Individual estimated effects of ordinal variables are grayed out in favor of an additional linear trend line. Effects of human and dog diet are highlighted through gray-shaded areas to reflect their separate estimation scheme (i.e., these effects were estimated while not controlling for further human demographic variables) as outlined in Section 2.2.

In terms of region, Other Europeans rated Pet Focus I, Pet Focus II, and Personal Focus less importantly than those from the UK. This constituted an effect for the first two aforementioned categories (Estimate = −0.15, CI: [−0.18, −0.12], p < 0.0001; Estimate = −0.11, CI: [−0.15, −0.08], p < 0.0001), and a trend for the latter (Estimate = −0.05, CI: [−0.08, −0.02], p = 0.3384). Trends were also found regarding North Americans rating Pet Focus I more importantly than those from the UK (Estimate = +0.05, CI: [+0.01, +0.09], p > 0.9999), and those from Oceania rating Pet Focus II less importantly than those from the UK (Estimate = −0.08, CI: [−0.14, −0.02], p > 0.9999). Supplementary Figure S2 shows the reduced importance of Pet Focus I for Other Europeans was mainly in relation to palatability and diet quality (not health). It also shows that the social/cultural subitem of Personal Focus was rated considerably more important than price and convenience by all regions relative to UK. Additionally, all regions rated Personal Values as more important relative to the UK. The share of Personal Value items ticked by Other Europeans was on average 15 percentage points higher than those in the UK, which constituted an effect (Estimate = +0.15, CI: [+0.10, +0.20], p < 0.0001). Trends were also found for North Americans (Estimate = +0.07, CI: [+0.001, +0.13], p > 0.9999) and those from Oceania (Estimate = +0.11 (CI: [+0.03, +0.19], p = 0.7455) relative to the UK.

With regard to age, there was a decreasing tendency to rate the Personal Focus category as important with increasing age. Relative to the 18–29 age group, four trends were found regarding this (ages 40–49: estimate = −0.05, CI: [−0.08, −0.01], p > 0.9999; ages 50–59: estimate = −0.06, CI: [−0.10, −0.03], p = 0.0930; ages 60–69: estimate = −0.05, CI: [−0.09, −0.02], p > 0.9999; and ages 70+: estimate = −0.11, CI: [−0.17, −0.05], p = 0.0608). There was also a tendency to find Pet Focus I and Personal Vaues increasingly more important with increasing education. Regarding the Pet Focus I category, one trend was found for those not completing high school relative to those with a doctorate (Estimate = −0.16, CI: [−0.25, −0.06], p = 0.1927). Regarding the Personal Values category, a further trend was found for this same tendency for guardians completing high school relative to those with a doctorate (Estimate = −0.10, CI: [−0.19, −0.01], p > 0.9999). Finally, regarding income, Personal Focus received lower ratings of importance with increasing income. There was a trend for both medium (Estimate = −0.03, CI: [−0.06, −0.0001], p > 0.9999) and high (Estimate = −0.07, CI: [−0.11, −0.03], p > 0.9999), relative to low income. Specifically, Supplementary Figure S2 shows a 39% reduced chance of the price subitem being ticked by guardians on a high income compared to those on a low income (OR = −39%, CI: [−52%, −23%]). This constituted an explorative tendency (Table S1b).

In terms of dog demographics, the main variable impacting on current pet food purchasing determinants was dog diet. Compared to guardians feeding their dogs a conventional meat-based diet, guardians feeding a vegan diet rated all categories (except Personal Values) significantly less importantly (Pet Focus I: estimate = −0.07, CI: [−0.10, −0.04], p = 0.0008); Pet Focus II: estimate = −0.08, CI: [−0.11, −0.04], p = 0.0047); Personal Focus: estimate = −0.13, CI: [−0.16, −0.10], p < 0.0001). These constituted three effects. The converse was true for Personal Values; those feeding a vegan diet rated this category significantly more important than those feeding a conventional meat-based diet (Estimate = +0.31, CI: [+0.26, +0.35], p < 0.0001). This likewise constituted an effect.

Similarly to those feeding a vegan diet, those feeding a raw meat diet also rated the Personal Values category significantly more important (Estimate = +0.09, CI: [+0.06, +0.12], p < 0.0001), and the Personal Focus category significantly less important (Estimate = −0.03, CI: [−0.06, −0.01], p = 0.6322), relative to those feeding a conventional meat-based diet. The former constituted an effect and the latter a trend. However, in contrast to those feeding a vegan diet, those feeding a raw meat diet rated the Pet Focus I (Estimate = +0.03, CI: [+0.01, +0.05], p > 0.9999) and Pet Focus II (Estimate = +0.19, CI: [+0.16, +0.21], p < 0.0001) categories more important than those feeding a conventional meat-based diet. These constituted a trend and an effect, respectively. Additionally, Supplementary Figure S3 shows this was in relation to the subitems naturalness and freshness (vs. reputation) for Pet Focus II. This figure also shows that the health/nutrition subitem of Pet Focus I was not applicable, nor the social/cultural subitem of Personal Focus. All other subitems scored similarly.

3.3. Acceptance and Essential Characteristics of More Sustainable Dog Diets

3.3.1. Acceptance of More Sustainable Dog Diets

Those feeding conventional or raw meat-based diets (collectively 84.2%, 2188/2596) were asked which alternative food types they might realistically consider, assuming all their desired attributes could be met—2169 responded. Table 2 demonstrates how all of the alternatives remained unacceptable to 56.8% (1231/2169). Cultivated meat-based food was the next most common selection, chosen by 24.4% (529/2169) of respondents. Vegetarian, insect-based, and vegan options were selected by respondents to comparable extents (16.6%, 359/2169; 15.5%, 336/2169; and 13.4%, 290/2169, respectively). Included in these figures are 10 respondents who deemed all options unacceptable, but who also simultaneously selected one of the alternatives as acceptable (cultivated meat, n = 4; vegetarian, n = 3; vegan, n = 1; insect-based, n = 2).

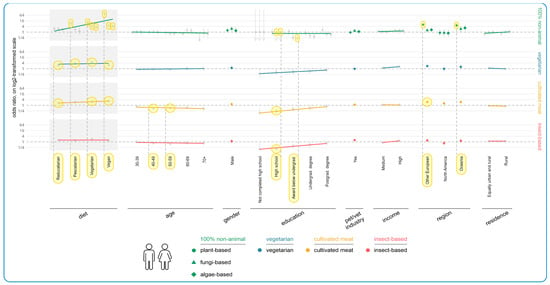

The results of the regression modeling of associations between human and dog demographics and acceptance of alternative more sustainable dog diets are shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9, respectively. The main tendencies found among human demographic variables concerned guardian diet, age, education, and region. In terms of guardian diet, there were clear tendencies of greater acceptance of all alternative diets (bar insect-based food). Vegans and vegetarians were significantly more likely to accept all 100% animal-free options, relative to omnivores. This resulted in six effects, as follows: plant-based (vegan: OR = +8662%, CI: [+5216%, +14,341%], p < 0.0001; vegetarian: OR = +972%, CI: [+538%, +1702%], p < 0.0001); fungi-based (vegan: OR = +375%, CI: [+188%, +684%], p < 0.0001; vegetarian: OR = +322%, CI: [+152%, +605%], p < 0.0001); and algae-based (vegan: OR = +304%, CI: [+145%, +565%], p < 0.0001; vegetarian: OR = +241%, CI: [+103%, +472%], p = 0.0011). An effect was also found regarding pescatarians’ higher acceptance of plant-based alternatives relative to omnivores (OR = +736%, CI: [+346%, +1468%], p < 0.0001).

Figure 8.

Logistic regression results on the associations between human demographic characteristics and the acceptance of more sustainable dog diets, among guardians currently feeding meat-based dog food (raw or conventional), relative to the reference characteristics for each group. Note: The reference characteristics for these people were: omnivore, aged 18–29, female, doctoral degree, not in pet/vet industry, low income, UK- and urban-based. Effects are depicted as odds ratios, including 95% confidence intervals (not corrected for multiple testing). Effects that are significant after multiple testing correction are highlighted with yellow bubbles. Individual estimated effects of ordinal variables are grayed out in favor of an additional linear trend line. Effects of human diet are highlighted through gray-shaded areas to reflect their separate estimation scheme (i.e., these effects were estimated while not controlling for further human demographic variables) as outlined in Section 2.2.

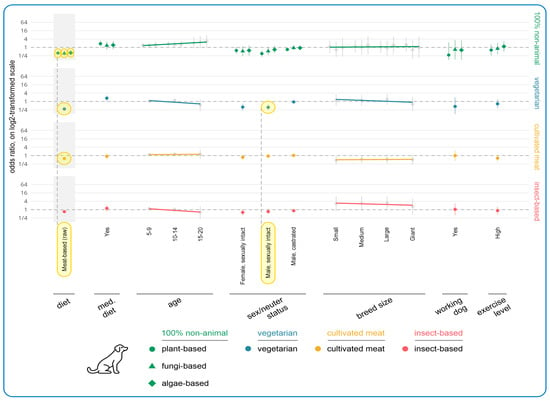

Figure 9.

Logistic regression results on the associations between dog demographic characteristics and the acceptance of sustainable dog diets, relative to the reference characteristics for each group. Note: The reference characteristics for these dogs were: meat-based (conventional), no medical diet, aged 0–4, female, spayed, toy size, a companion dog, and normal exercise levels. Effects are depicted as odds ratios, including 95% confidence intervals (not corrected for multiple testing). Effects that are significant after multiple testing correction are highlighted with yellow bubbles. Individual estimated effects of ordinal variables are grayed out in favor of an additional linear trend line. Effects of dog diet are highlighted through gray-shaded areas to reflect their separate estimation scheme (i.e., these effects were estimated while not controlling for further human demographic variables) as outlined in Section 2.2.

Relative to omnivore guardians, four effects were also found regarding higher acceptance of vegetarian diets among reducetarians (OR = +123%, CI: [+63%, +205%], p = 0.0001), pescatarians (OR = +266%, CI: [+131%, +481%], p < 0.0001), vegetarians (OR = +424%, CI: [+268%, +646%], p < 0.0001), and vegans (OR = +149%, CI: [+68%, +267%], p = 0.0015). For vegans, there was a slight dip regarding the general tendency of increased acceptance of vegetarian diets with reduced animal consumption. For cultivated meat, three effects were found regarding reducetarians’ (OR = +70%, CI: [+32%, +120%], p = 0.0119), vegetarians’ (OR = +152%, CI: [+83%, +246%], p < 0.0001), and vegans’ (OR = +184%, CI: [+107%, +289%], p < 0.0001) acceptance of this alternative relative to omnivores, and one trend for pescatarians (OR = +119%, CI: [+44%, +232%], p = 0.0749).

In terms of age, there was a slight decreasing acceptance of cultivated meat with increasing guardian age. Two effects were found for the 40–49 (OR = −55%, CI: [−68%, −36%], p = 0.0020) and 50–59 (OR = −50%, CI: [−64%, −30%], p = 0.0183) age groups, relative to ages 18–29. The acceptability of plant-based alternatives was also 86% lower for guardians aged 70+, compared relative to ages 18–29. This constituted a trend (OR = −86%, CI: [−97%, −38%], p > 0.9999).

In terms of education, there were clear tendencies of higher acceptance of alternative diets (except 100% animal-free) with increasing education levels. For cultivated meat, there was one effect; namely, those with high school as the highest education level accepted cultivated meat significantly less than guardians with a doctorate (OR = −75%, CI: [−86%, −55%], p = 0.0016). One effect was found regarding lower acceptance of insect-based alternatives among those completing high school relative to guardians with a doctorate (OR = −83%, CI: [−91%, −65%], p = 0.0003). Eight additional trends were also found in support of the tendency towards higher acceptance of more sustainable alternative dog diets with increasing education.

With regard to 100% animal-free diets, three education effects were found; namely, those completing high school were significantly less likely to accept fungi-based (OR = −88%, CI: [−95%, −70%], p = 0.0025) and algae-based (OR = −90%, CI: [−96%, −75%], p = 0.0003) dog diets, and those with an award below undergraduate degree level were significantly less likely to accept algae-based alternatives (OR = −78%, CI: [−90%, −54%], p = 0.0221), relative to guardians with a doctorate. Three trends were also found.

The region guardians lived in showed three further effects. Plant-based diets were considered significantly more acceptable by Other Europeans (OR = +522%, CI: [+343%, +791%], p < 0.0001) and guardians from Oceania (OR = +417%, CI: [+198%, +797%], p < 0.0001), relative to those from the UK, while Other Europeans were also significantly more likely to accept cultivated meat-based dog food (OR = +124%, CI: [+61%, +211%], p = 0.0004), relative to those from the UK. These constituted three effects.

In terms of dog demographics, among the guardians currently feeding conventional or raw meat-based dog food, the key variables impacting acceptance of alternatives were current dog diet, dog age, and sex/neuter status. Guardians currently feeding raw meat were significantly less accepting of virtually all alternatives, relative to those feeding a conventional meat-based diet. This generated five effects: plant-based (OR = −61%, CI: [−71%, −47%], p < 0.0001); fungi-based (OR = −63%, CI: [−76%, −43%], p = 0.0014); algae-based (OR = −59%, CI: [−73%, −38%], p = 0.0105); vegetarian (OR = −71%, CI: [−79%, −61%], p < 0.0001); and cultivated meat (OR = −39%, CI: [−50%, −24%], p = 0.0029).

One effect was also found regarding guardians of male sexually intact dogs being significantly less likely to accept vegetarian dog diets (OR = −62%, CI: [−76%, −40%], p = 0.0130). This reflected a general tendency for guardians of both female and male sexually intact dogs to be less accepting of more sustainable alternatives, for which there were two trends. In terms of dog age, there was a clear increasing tendency to accept animal-free foods as the age of dogs increased. For instance, the chance that plant-based dog food was considered acceptable was 42% higher for guardians whose dog was 5–9 years old (OR = +42%, CI: [+3%, +97%], p > 0.9999), and 77% higher for guardians whose dog was 10–14 years (OR = +77%, CI: [+19%, +164%], p > 0.9999), compared to guardians of dogs aged 0–4 years. These both constituted trends. Additionally, guardians of dogs progressing onto a medical diet were more accepting of plant-based dog diets (OR = +84%, CI: [+8%, +212%], p > 0.9999) and vegetarian dog diets (OR = +73%, CI: [+8%, +177%], p > 0.9999), relative to guardians of dogs not progressing onto a medical diet. These also constituted trends.

3.3.2. Essential Characteristics of Alternative Dog Diets

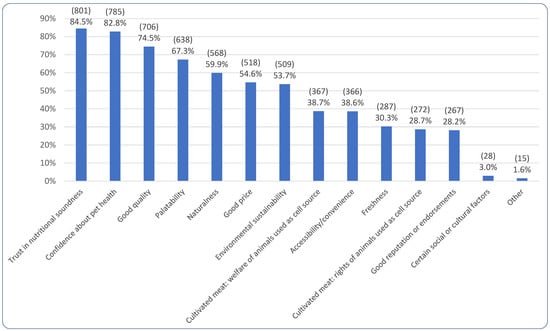

Figure 10 portrays the frequencies with which different attributes were considered essential in order for alternative dog foods to be chosen, by guardians open to more sustainable alternative dog diets. Confidence about nutritional soundness was selected most commonly (by 84.5%, 801/948). When these respondents were asked if there were specific nutrients alternative foods would need to provide, 80.8% (647/801) said ‘No’ with the remainder stating ‘Yes’ (19.2%, 154/801). Those selecting ‘Yes,’ were asked which nutrients would be necessary; among 154 responses, common answers included ‘all essential nutrients,’ exceeding FEDIAF/AAFCO/NRC/WSAVA minimum requirements, B12, vitamin D, omegas, glucosamine, chondroitin, ‘the same amino acid profile as meat,’ prebiotics, probiotics, protein, and taurine.

Figure 10.

Distribution of attributes of sustainable dog food alternatives considered essential by guardians currently feeding conventional/raw meat-based dog food who stated they may realistically consider a sustainable alternative. Note: These attributes were considered essential in order for these respondents to realistically consider choosing alternative options. Multiple responses were possible; thus, the percentages and counts represent the proportion of all respondents (n = 948) selecting each answer option. Among these respondents are 10 respondents who deemed all options unacceptable, but who also simultaneously selected one of the alternatives as acceptable (cultivated meat, n = 4; vegetarian, n = 3; vegan, n = 1; insect-based, n = 2). Common ‘Other’ answers (1.6%, n = 15) included allergen-free, evidence-based nutrition including bioavailability, specific health concerns such as skin problems and gastrointestinal reactions, and insect welfare.

Of the 28.2% (267/948) selecting a ‘Good reputation or endorsements’ as essential, 51.3% (137/267) selected ‘A good reputation without specific endorsements would be enough,’ 46.4% (124/267) selected ‘Endorsements by veterinarians,’ 21.0% (56/267) selected ‘Endorsement by others,’ and 12.4% (33/267) selected ‘Endorsement by other veterinary staff.’ Of the 21.0% (56/267) selecting ‘Endorsement by others,’ common ‘Other’ responses included ‘Canine nutritionist’, the ‘All about dog food’ website, ‘Canine behaviorists’, animal welfare organizations, dog guardians, breeders, and independent researchers. Among the 3.0% (28/948) selecting ‘Certain social or cultural factors,’ 82.1% (23/28) selected ‘Country of origin of ingredients or finished product’ as important, 53.6% (15/28) selected ‘Employment of farmers and workers,’ 21.4% (6/28) selected ‘Cultural or religious factors,’ and 10.7% (3/28) selected ‘Other’ (e.g., ‘humanely reared’ and ‘not Halal’).

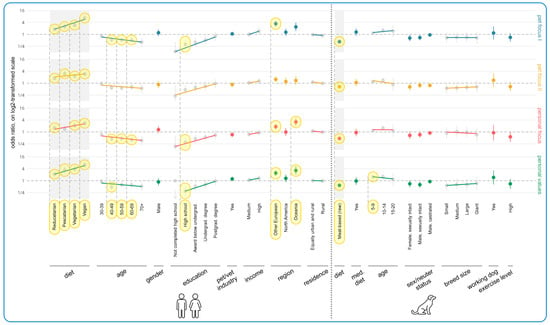

Figure 11 shows the results of the regression modeling of associations between human and dog demographics and essential characteristics that alternative diets would require for them to realistically be chosen. In terms of human demographics, the most noteworthy results concerned guardian diet, age, education, and region. There was a clear tendency for all essential characteristic categories to increase in importance with reduced animal consumption. This resulted in effects for all dietary types and categories (15 in total), except pescatarian and Personal Focus (which was also not a trend). To take just one pair of examples (of the 15 in total) from opposite ends of the dietary spectrum, vegans were 572% more likely to find Pet Focus I important (OR = +572%, CI: [+395%, +813%], p < 0.0001), relative to omnivores, while reducetarians were 82% more likely (OR = +82%, CI: [+46%, +127%], p < 0.0001). Supplementary Figure S4 demonstrates this pattern applied across category subitems.

Figure 11.

Logistic regression results on the associations between human/dog demographic characteristics and characteristics of more sustainable dog diets considered essential, among guardians currently feeding meat-based dog food (raw or conventional), relative to the reference characteristics for each group. Note: The reference characteristics for these humans and dogs were, respectively, as follows: human: omnivore, aged 18–29, female, doctoral degree, not in pet/vet industry, low income, UK- and urban-based; dog: meat-based (conventional), no medical diet, aged 0–4, female, spayed, toy size, a companion dog, and normal exercise levels. The right y-axis essential characteristic categories comprise the following subitems: Pet Focus I (health, nutrition, palatability, diet quality), Pet Focus II (naturalness, freshness, diet reputation), Personal Focus (price, convenience, social/cultural aspects), and Personal Values (sustainability and animal welfare/rights regarding source animals used for cultivated meat-based dog food). Each dependent variable (e.g., Pet Focus I) reflects the information if at least one item among its underlying set of items (see Figures S4 and S5) was ticked in the questionnaire. Effects are depicted as odds ratios, including 95% confidence intervals (not corrected for multiple testing). Effects that are significant after multiple testing correction are highlighted with yellow bubbles. Individual estimated effects of ordinal variables are grayed out in favor of an additional linear trend line. Effects of human and dog diet are highlighted through gray-shaded areas to reflect their separate estimation scheme (i.e., these effects were estimated while not controlling for further human demographic variables) as outlined in Section 2.2.

There was also a clear tendency of decreasing importance of all essential characteristic categories with increasing guardian age. This resulted in three effects for the Pet Focus I category: 40–49 (OR = −47%, CI: [−61%, −27%], p = 0.0139), 50–59 (OR = −48%, CI: [−61%, −29%], p = 0.0059), and 60–69 (OR = −47%, CI: [−62%, −26%], p = 0.0326). There were also three effects for the Personal Focus category: 40–49 (OR = −55%, CI: [−68%, −38%], p = 0.0003), 50–59 (OR = −55%, CI: [−67%, −37%], p = 0.0003), and 60–69 (OR = −60%, CI: [−72%, −42%], p = 0.0002). Additionally, there was an effect regarding the tendency for the 40–49 guardian age group to rate Personal Values as more essential (OR = −52%, CI: [−66%, −32%], p = 0.0043), relative to those aged 18–29. There were also 10 trends in further support of this tendency (see Supplementary Table S2b).

In terms of education, there were clear tendencies of increasing importance of all essential characteristic categories with increasing education levels. This included three effects—all for guardians who had completed high school and their lower valuing of Pet Focus I (OR = −68%, CI: [−82%, −44%], p = 0.0114), Personal Focus (OR = −70%, CI: [−83%, −47%], p = 0.0061), and Personal Values (OR = −70%, CI: [−83%, −47%], p = 0.0076), relative to guardians with a doctorate. There were also 10 trends in further support of this tendency (see Supplementary Table S2b).

In terms of region, Other Europeans and those from Oceania tended to value all categories more than guardians from the UK, and five further effects were found in this regard: Pet Focus I (Other European: OR = +245%, CI: [+149%, +380%], p < 0.0001), Personal Focus (Other European: OR = +84%, CI: [+35%, +152%], p = 0.0182), Oceania: OR = +220%, CI: [+99%, +416%], p = 0.0003), and Personal Values (Other European: OR = +143%, CI: [+78%, +232%], p < 0.0001), Oceania: OR = +228%, CI: [+102%, +431%], p = 0.0003). Trends were also found for Pet Focus II regarding Other European (OR = +56%, CI: [+14%, +112%], p = 0.7027), and Pet Focus I regarding Oceania (OR = +140%, CI: [+47%, +291%], p = 0.0685). Supplementary Figure S4 demonstrates the category subitems were rated fairly similarly for all of the cases above, apart from for a lower rating by Other Europeans for nutritional soundness and palatability in Pet Focus I.

In terms of dog demographics, the key impacting variable was current dog diet. Among the guardians not currently feeding a more sustainable alternative, those currently feeding a raw meat-based diet to their dogs were significantly less likely to find all categories important, relative to guardians feeding a conventional diet. This constituted four effects: Pet Focus I (OR = −57%, CI: [−64%, −48%], p < 0.0001), Pet Focus II (OR = −34%, CI: [−46%, −19%], p = 0.0094), Personal Focus (OR = −53%, CI: [−62%, −42%], p < 0.0001), and Personal Values (OR = −42%, CI: [−52%, −28%], p < 0.0001). Supplementary Figure S5 shows similar ratings across all subitems except for the freshness subitem in Pet Focus II; it is rated of similar importance as those feeding conventional meat. Additionally, guardians of sexually intact male and female dogs rated all categories less important than guardians of spayed females. For instance, guardians with a female sexually intact dog had a 35% lower chance of having ticked at least one item in the Pet Focus II (OR = −35%, CI: [−56%, −4%], p > 0.9999), compared to people with a female spayed dog, and guardians with a male sexually intact dog had a 31% lower chance of having done so for Pet Focus I (OR = −31%, CI: [−49%, −7%], p > 0.9999). These both constituted trends. Supplementary Figure S5 shows similar scoring across all subitems, though the reputation subitem within Pet Focus II was especially low.

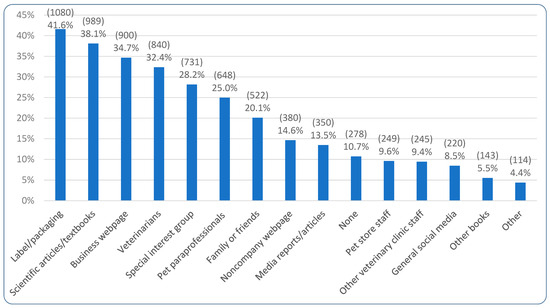

3.4. Dog Diet Information Sources

Figure 12 demonstrates the information sources that respondents selected as significantly influencing their pet food choices. ‘Label/packaging’ was most commonly selected, by 41.6% (1080/2596). Additionally, 82.9% (2153/2596) reported not having received any nutritional recommendations from veterinary clinic staff in the last year, with 15.0% (389/2596) reporting that they had and 2.1% (54/2596) stating they were unsure. Of those reporting they had, 384 left comments regarding what particular advice they had received. Table 5 summarizes this advice, with a recommendation of ailment-specific food (n = 53), particular brands (n = 47), and supplements (n = 46) being the three most common. Of note is that compliance with the veterinary advice reported by 379 (of 389) was described as ‘Good’ by 60.2% (228/379), ‘Poor’ by 26.4% (100/379), and ‘Medium’ by 13.5% (51/379).

Figure 12.

Distribution of information sources significantly influencing respondents’ dog diet choices. Note: Multiple responses were possible; thus, the percentages and counts represent the proportion of all respondents (n = 2596) selecting each answer option. Elaborations on ‘Other’ (4.4%, n = 114) included previous users of a dog food product, animal nutritionists, product awards, adoption charity practice, and ingredients listed (as opposed to other label/packaging details).

Table 5.

Distribution of veterinary nutritional advice received (n = 384).

Figure 13 demonstrates the results of the regression modeling regarding associations between human and dog demographics and information sources used to inform dog diet decisions. The most noteworthy tendencies regarding human demographics concerned guardian diet, age, education level, working in the pet/vet industries, and region. There was a slight increasing tendency to value all categories of information sources with decreasing animal consumption (except Vet/Pet Care). This was particularly the case for Media/Literature with the differences in valuing this category constituting an effect for vegan guardians relative to omnivores; vegans were 137% more likely to use this information source than omnivores (OR = +137%, CI: [+91%, +194%], p < 0.0001). Vegetarians were 42% more likely to use Media/Literature relative to omnivores (OR = +42%, CI: [+8%, +87%], p > 0.9999), which constituted a trend. A trend was also found in the Product-Specific category insofar as vegans were 25% more likely to use this category relative to omnivores (OR = +25%, CI: [+1%, +54%], p > 0.9999). In contrast, while reducetarians, pescatarians, and vegetarians valued Vet/Pet Care to a similar extent to (or slightly more than) omnivores, vegans used this category significantly less than omnivores (OR = −29%, CI: [−43%, −12%], p = 0.2604); this constituted a trend. Supplementary Figure S6 shows this was particularly the case for pet paraprofessionals.

Figure 13.

Logistic regression results on the associations between human/dog demographic characteristics and dietary information sources, relative to the reference characteristics for each group. Note: The reference characteristics for these humans and dogs were, respectively, as follows: (human) omnivore, aged 18–29, female, doctoral degree, not in pet/vet industry, low income, UK- and urban-based; (dog) meat-based (conventional), no medical diet, aged 0–4, female, spayed, toy size, a companion dog, and normal exercise levels. The right y-axis information source categories comprise the following subitems: Product-Specific (label/packaging, company webpage), Vet/Pet Care (veterinarians, other vet clinic staff, pet store staff, pet paraprofessionals), Media/Literature (scientific literature, media reports, non-company webpages, other books), and Social Media (online special interest groups, general social media). Each dependent variable (e.g., Product-Specific) reflects the information if at least one item among its underlying set of items (see Figures S6 and S7) was ticked in the questionnaire. Effects are depicted as odds ratios, including 95% confidence intervals (not corrected for multiple testing). Effects that are significant after multiple testing correction are highlighted with yellow bubbles. Individual estimated effects of ordinal variables are grayed out in favor of an additional linear trend line. Effects of human and dog diet are highlighted through gray-shaded areas to reflect their separate estimation scheme (i.e., these effects were estimated while not controlling for further human demographic variables) as outlined in Section 2.2.

In terms of the impact of age, Vet/Pet Care was used less by all age groups than 18–29 year olds. For instance, 50–59 year olds used Vet/Pet Care 52% less than 18–29 year olds (OR = −52%, CI: [−64%, −37%], p < 0.0001), and 60–69 year olds 50% less (OR = −50%, CI: [−63%, −32%], p = 0.0023). These both constituted effects. There were also two trends for the 30–39 (OR = −37%, CI: [−52%, −17%], p = 0.1785) and 40–49 (OR = −40%, CI: [−54%, −21%], p = 0.0560) age groups. Supplementary Figure S6 shows that low Vet/Pet Care use did not apply to pet paraprofessionals. For the other three information categories, there were clear decreasing tendencies of use as guardian age increased. There were two effects for the 70+ age group regarding their use of Product-Specific sources (OR = −68%, CI: [−80%, −48%], p = 0.0005) and Social Media (OR = −70%, CI: [−84%, −45%], p = 0.0230); Supplementary Figure S6 shows that low Social Media use primarily concerned the subitem general social media use. There was also one effect for the 60–69 age group in relation to the Product-Specific category (OR = −45%, CI: [−60%, −25%], p = 0.0260). There were two trends for the 40–49 (OR = −30%, CI: [−47%, −7%], p > 0.9999) and 50–59 (OR = −29%, CI: [−46%, −6%], p > 0.9999) age groups in terms of the Product-Specific category as well as three trends for the 40–49 (OR = −35%, CI: [−51%, −14%], p = 0.4007), 60–69 (OR = −39%, CI: [−55%, −17%], p = 0.3333), and 70+ (OR = −54%, CI: [−71%, −25%], p = 0.2971) age groups in terms of the Media/Literature category.

In terms of education, there were clear tendencies of increased information source category use as education level increased, apart from for the Product-Specific category. This included two effects for not completing high school and Vet/Pet Care use (OR = −85%, CI: [−94%, −63%], p = 0.0095) and high school as the highest education level achieved and Media/Literature use (OR = −67%, CI: [−80%, −45%], p = 0.0041), relative to those with a doctorate. There were also four trends: completing high school and Vet/Pet Care use (OR = −42%, CI: [−64%, −5%], p > 0.9999); and not completing high school (OR = −78%, CI: [−91%, −49%], p = 0.0805), an award below undergraduate degree (OR = −57%, CI: [−74%, −28%], p = 0.1975), and undergraduate degree (OR = −51%, CI: [−70%, −19%], p = 0.8701) in terms of Media/Literature use, relative to those with a doctorate. Supplementary Figure S6 shows pet store staff are used more than other subitems in Vet/Pet Care, media reports more than other subitems in Media/Literature, and that the subitems are all rated quite similarly for Social Media.

Those working in the pet/vet industries were 53% more likely than those not working in such industries to use Media/Literature and 31% less likely to use Social Media for pet food decisions. This constituted an effect (OR = +53%, CI: [+23%, +91%], p = 0.0242) and a trend (OR = −31%, CI: [−46%, −13%], p = 0.2604), respectively. Supplementary Figure S6 shows the Media/Literature use concerned scientific literature and other books. Additionally, all other regions (Other European, North American, and Oceania) all used Media/Literature more than those in the UK. This constituted two effects (OR = +72%, CI: [+35%, +120%], p = 0.0030; OR = +141%, CI: [+64%, +254%], p = 0.0016) and a trend (OR = +72%, CI: [+14%, +159%], p > 0.9999), respectively. Supplementary Figure S6 shows this particularly related to the subitem scientific literature use. There were no effects found in relation to gender, though males were 41% less likely to use Social Media (OR = −41%, CI: [−59%, −15%], p = 0.6890) than females, which was a trend; Supplementary Figure S6 shows this was similar across subitems.

The most noteworthy tendencies regarding dog demographics concerned dog diet, medical diet, sex/neuter status, and breed size. In terms of dog diet, guardians feeding both raw meat and vegan diets used Product-Specific and Vet/Pet Care categories less than those feeding conventional meat. This resulted in two effects in the Vet/Pet Care category (vegan: OR = −61%, CI: [−69%, −49%], p < 0.0001; raw meat: OR = −39%, CI: [−49%, −27%], p < 0.0001), and a trend in the Product-Specific category (raw meat: OR = −23%, CI: [−35%, −8%], p = 0.7351). Supplementary Figure S7 shows that for those feeding raw meat the low rating particularly applied to veterinarians; for those feeding vegan, veterinarians were the only subitem not rated low relative to those feeding a conventional meat diet. In contrast, guardians feeding both raw meat and vegan diets had significantly increased use of Media/literature and Social Media, relative to guardians feeding a conventional meat diet. This resulted in two effects for Media/Literature (vegan: OR = +165%, CI: [+104%, +243%], p < 0.0001; raw meat: OR = +46%, CI: [+22%, +74%], p = 0.0066), and two effects for Social Media (vegan: OR = +141%, CI: [+86%, +212%], p < 0.0001); raw meat: OR = +269%, CI: [+204%, +347%], p < 0.0001). Supplementary Figure S7 shows the subitems ‘scientific literature’ and ‘other books’ were particularly applicable to Media/Literature (although scientific literature was lower for raw meat feeders) and that special interest groups were particularly applicable to Social Media, especially for those feeding raw meat.

Guardians of dogs who progressed onto a medical diet were 237% more likely to use Vet/Pet Care as an information source relative to guardians of dogs not progressing onto a medical diet (OR = +237%, CI: [+118%, +419%], p < 0.0001); this constituted an effect. Supplementary Figure S7 shows this pertained to veterinarians and other veterinary staff only. There were tendencies regarding guardians of sexually intact dogs using the Product-Specific category less than guardians of female, spayed dogs. This constituted one effect insofar as guardians of female, sexually intact dogs were 51% less likely to use this category (OR = −51%, CI: [−64%, −32%], p = 0.0021), and one trend insofar as guardians of male, sexually intact dogs were 35% less likely to use this category (OR = −35%, CI: [−50%, −16%], p = 0.2035). Supplementary Figure S7 shows this applied across all subitems. No other impact of sex/neuter status was found.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to gain insights into (1) dog guardians’ current feeding patterns and dog food purchasing determinants, (2) acceptance of more sustainable dog diets, and (3) sources of information used for decisions about dog diets. This section discusses the most important results regarding each of these three main parts of this research. Current feeding practices and purchasing determinants are first discussed, followed by acceptance of alternative sustainable dog food options, and finally, dog food information sources used by guardians. The section finishes with consideration of this study’s limitations, and with recommendations for stakeholders within the dog food industry. The discussion centers primarily on feeding vegan diets to dogs as this is the primary focus of the study as explained in Section 1.2.

4.1. Current Feeding Practices and Purchasing Determinants

The present study found that 52% of dog guardians fed a primarily conventional meat-based diet to their dogs and that over 71% of guardians’ dogs diets comprised 75% or more commercial dog food. It also found the top three means of acquiring dog food were direct from the manufacturer, online, or from a pet store. Direct comparisons with findings from other studies are difficult due to varying wording or question types in different surveys. Nevertheless, broadly speaking, this finding is reflected elsewhere in the literature. For instance, in an international survey of dog and cat guardians, Dodd et al. [46] found that 78% of dog guardians at least partially fed their dogs a conventional (commercial, heat-processed) diet, with 79% of these guardians doing so daily. This amounts to 63% of the overall total number of dog guardians surveyed. While this figure is 11% higher than our corresponding figure, the question wording was different to that of the present study. It enquired about frequency of feeding (with daily being the highest frequency). Daily feeding does not necessarily equate to the primary food provided, which is what was enquired about in the present survey. Hence, one could expect the 63% figure to reduce a little on account of these differences. Additionally, Dodd et al. [46] did not differentiate between vegan and nonvegan conventional dog food for this specific survey question, which may also reduce the 63% figure slightly if only meat-based conventional dog food is considered.

In a UK-based survey of dog and cat guardians, Hunter and Murison [60] found just under 60% of dog guardians fed wet, dry, or both wet and dry commercial dog food and that online purchases direct from the manufacturer were the most common means of acquiring pet food. However, they did not distinguish between dogs and cats. Dodd et al. [46] also found the top three means of acquiring pet food to be pet stores, supermarkets, or through online distributors. Again, they did not differentiate between dog and cat guardians. The lack of differentiation between dog and cat guardians may account for the slight differences in results when compared to the present study. Higher figures for feeding primarily commercial kibble or canned food have been found in two further surveys: 86% [44] and almost 80% [45]. In both cases, the surveys were limited to the USA (implicitly, in the study by Schleicher et al. [45]) and guardians feeding vegan commercial pet food were not differentiated. In the latter case [45], dogs and cats were not differentiated between. In contrast to the aforementioned studies by Dodd et al. [46] and Hunter and Murison [60], Schleicher et al. [45] found that large pet stores, “Other,” or small pet stores were the three most popular means of purchasing pet food. Different terminology, combining dog/cat guardians, and different survey answer options may be partially responsible for the variations in top answers. Indeed, acquisition through online means was not listed as an option in the study by Schleicher et al. [45] and ‘Other’ was the second highest option at over 22%. Respondents purchasing pet food online may have selected “Other,” in this case, which would be congruent with the results from aforementioned studies.

The alternative diets making up the dog diet choices of the remaining 48% of guardians comprised primarily raw meat (32%) and vegan diets (13%). The present study found a substantially higher percentage of dog guardians feeding a raw meat-based diet, relative to the 3%, 9%, and 19% in studies by APPA [61], Dodd et al. [46], and Hunter and Murison [60], respectively. This suggests growth in the popularity of feeding raw meat diets. This is despite low support among veterinarians, health warnings against them, and lack of evidence supporting their use [62]. It may also be the case that guardians feeding raw meat were overrepresented in this survey. It must be noted that purposive sampling was undertaken for vegan guardians, so they are likely overrepresented, which would over-accentuate the downward tendency in conventional meat-based diets. For instance, without purposive sampling, the survey of primarily American and British pet guardians by Dodd et al. [16] found that just 1.6% (48/2940) of dog guardians feed their dogs a vegan diet. Few other estimations of feeding vegan diets exclusively exist to date.