The Role of Probiotics in Enhancing Animal Health: Mechanisms, Benefits, and Applications in Livestock and Companion Animals

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Methods for Figures

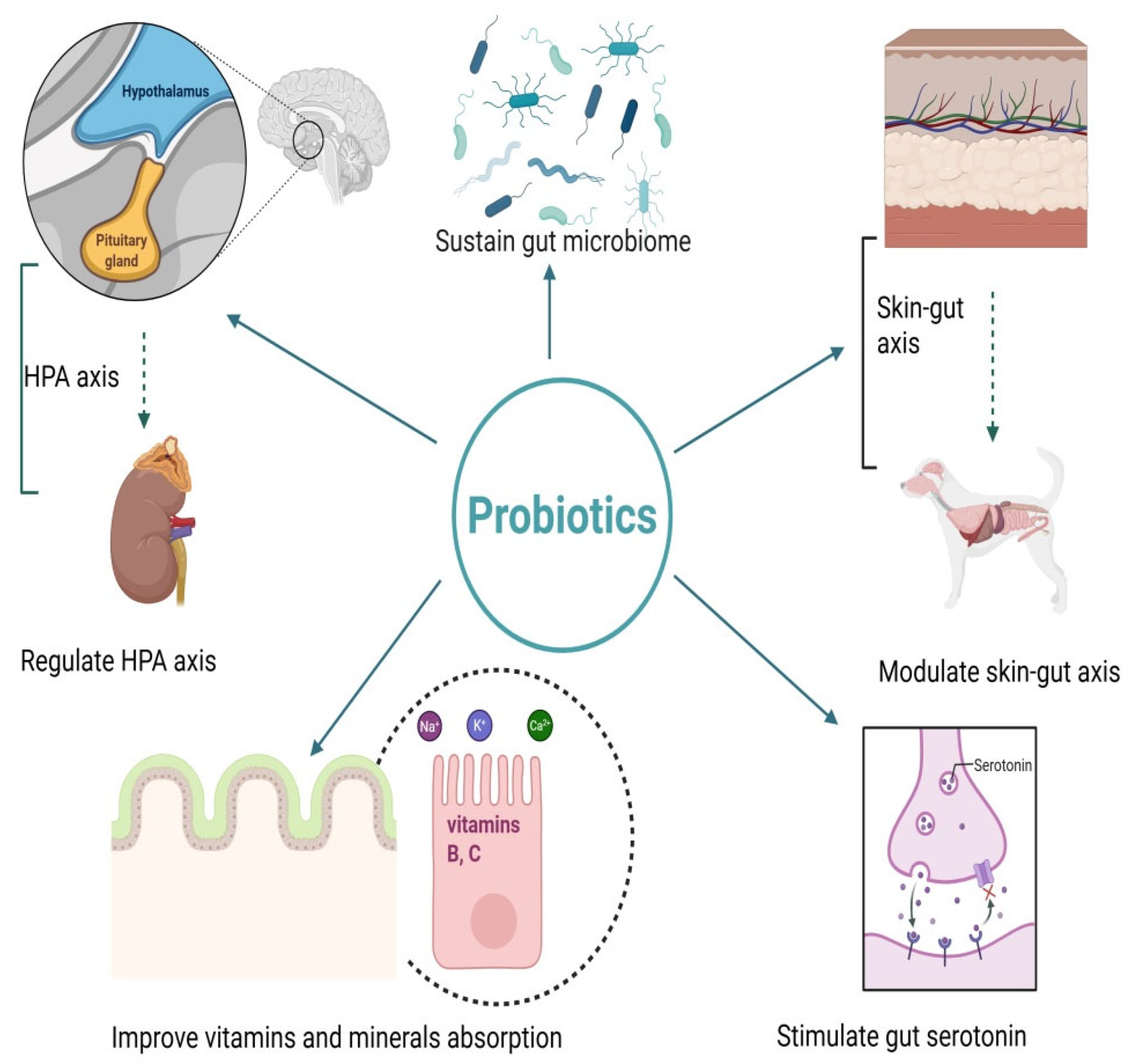

3. Mechanisms of Action of Probiotics

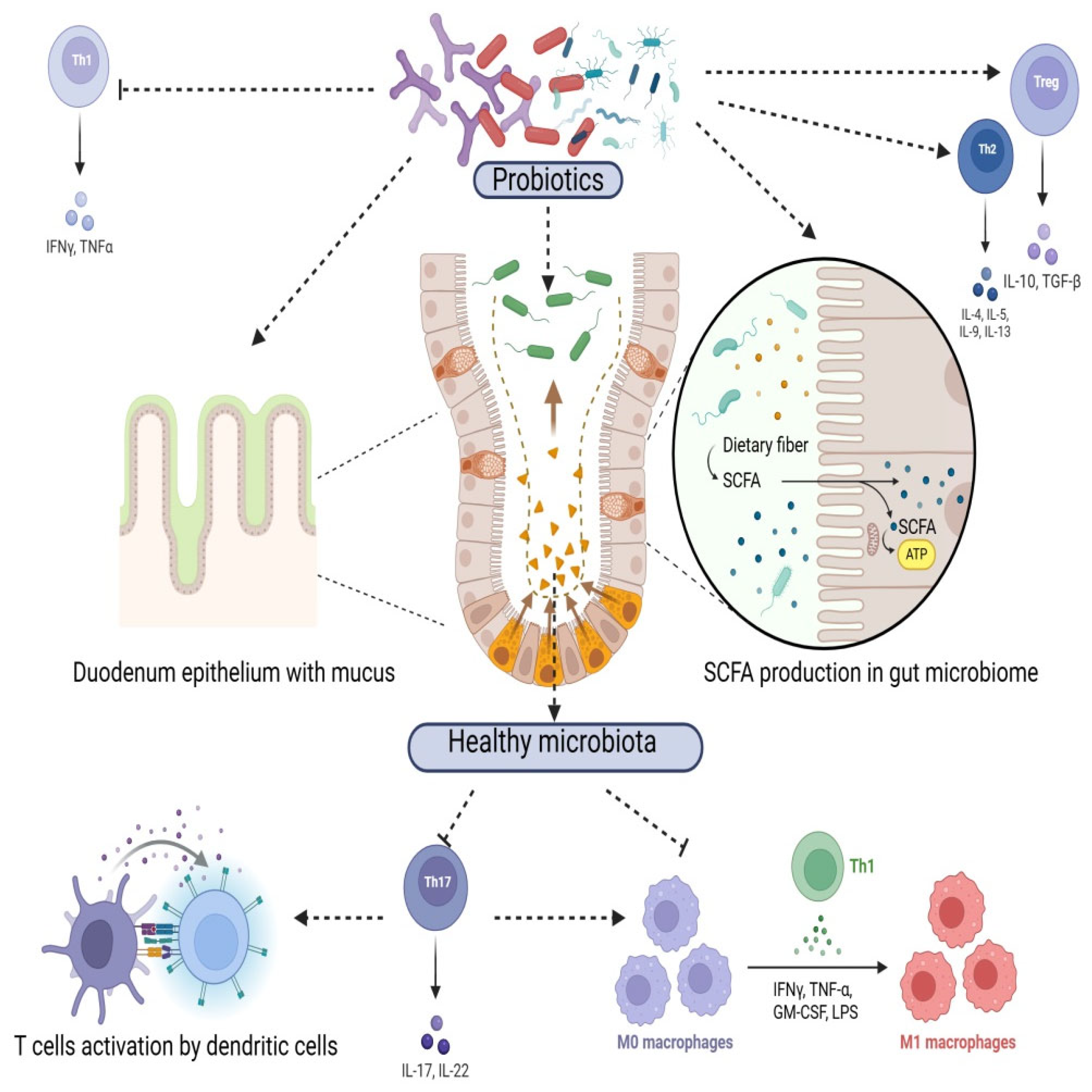

3.1. Gut Microbiota Modulation

3.2. Immune System Modulation

3.3. Pathogen Inhibition

3.4. Enhancement of Intestinal Barrier Function

3.5. Mechanisms Linking Probiotics to Stress and Depression in Animals

Probiotics and Cancer in Animals

4. Applications of Probiotics in Animal Health

4.1. Livestock Animals

4.1.1. Cattle

4.1.2. Poultry

4.1.3. Swine

4.1.4. Probiotics in Horses

4.2. Laboratory Animals

4.3. Companion Animals

4.3.1. Dogs

4.3.2. Cats

| Animal Species | Probiotic Strains/Formulations | Reported Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle (Dairy and Beef) | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Stabilizes rumen pH, supports cellulolytic bacteria, improves fiber digestion, enhances milk yield and composition | [109,110] |

| Lactobacillus plantarum, Propionibacterium freudenreichii | Converts lactate to propionate, stabilizes rumen pH, improves energy metabolism | [111,112] | |

| Bacillus subtilis | Reduces enteric methane emissions, improves feed efficiency | [113] | |

| Lactate-producing bacteria (various strains) | Improve milk yield and feed efficiency by stabilizing rumen pH | [114] | |

| Lactobacillus spp. (specific strains) | Reduces fecal shedding of E. coli O157:H7 in feedlot cattle, improving food safety | [116] | |

| Poultry (Broilers and Layers) | Bifidobacterium bifidum, B. longum (in ovo) | Improves broiler growth and ileal development | [118] |

| Lactobacillus reuteri, B. bifidum | Increase villus height and villus/crypt ratio, improve nutrient absorption and feed conversion | [162] | |

| Bacillus subtilis | Improves growth performance, reduces mortality, strengthens intestinal barrier | [119,120] | |

| Multi-species mix (Lactobacillus, Bacillus) | Hastens clearance of Salmonella Enteritidis | [118] | |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus | Reduces cecal Salmonella (~2 log CFU reduction) | [118] | |

| Bacillus xiamenensis | Increases body weight, improves villus morphology, reduces E. coli and Salmonella | [122] | |

| B. subtilis, B. pumilus (water) | Mitigates heat stress, restores villus height | [122] | |

| Swine (Sows & Piglets) | Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium lactis | Restores microbial balance post-weaning, reduces E. coli diarrhea | [127] |

| Clostridium butyricum (multi-strain blends) | Improves colostrum quality, reduces neonatal diarrhea | [127] | |

| Bacillus-based probiotics | Relieve constipation and systemic inflammation in sows, improve piglet growth | [127] | |

| Multi-strain mix (L. acidophilus, L. casei, B. thermophilum, E. faecium) | Reduces post-weaning diarrhea incidence by >50% | [131] | |

| Horses | Saccharomyces boulardii | Stabilizes hindgut microbiota, reduces gas-forming bacteria, prevents colic | [133] |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | Reduces hindgut lactic acid accumulation, stabilizes pH, mitigates laminitis risk | [135] | |

| Yeast cultures (e.g., S. cerevisiae post-biotics) | Stabilize fecal microbiota during stress/transport | [138] | |

| Laboratory Animals (Rats) | Lactobacillus acidophilus, B. longum | Enhance mucosal immunity (↑IgA), reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines, improve gut integrity | [143,145] |

| Dogs | Lactobacillus acidophilus, Enterococcus faecium | Reduce diarrhea severity/duration, improve stool quality, strengthen mucosal immunity | [146,148,149] |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus | Produces neuroactive compounds influencing stress/anxiety | [101,151] | |

| Multi-strain probiotic | Faster resolution of acute diarrhea, comparable to metronidazole | [151,156] | |

| Synbiotic (E. faecium NCIMB 10415 prebiotic) | Reduces stress-related diarrhea in shelters | [146,148] | |

| VSL#3 (multi-strain) | Reduces clinical severity of IBD, improves gut barrier | [151] | |

| Lactobacillus sakei Probio-65 | Reduces severity of atopic dermatitis | [14] | |

| Cats | Bifidobacterium animalis | Improves SCFA production, enhances barrier function, lowers inflammation | [150,154] |

| Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | Increases IgA/IL-4, reduces TNF-α, improves gut barrier | [154] | |

| Lactobacillus reuteri | Reduces stress during transport or vet visits | [158] | |

| Enterococcus faecium SF68 | Decreases prolonged diarrhea episodes in shelters | [21,155] |

5. Environmental and Sustainability Aspects of Probiotics

5.1. Reducing Methane Emissions in Livestock

5.2. Improving Water Quality in Aquaculture

5.3. Reducing Antibiotic Usage

5.4. Sustainable Farming Practices

5.5. Molecular Mechanisms of Probiotic Action

5.6. Key Pathogens and Efficacy in Each Species

| Aspect | Mechanism | Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental sustainability of probiotics | Reduce pollution, mitigate greenhouse gases, enhance resource efficiency, combat AMR | Probiotics contribute to sustainable animal agriculture | [44,170,171] |

| Reducing methane emissions in livestock | Alter rumen microbial populations; suppress methanogenic archaea; redirect H2 to VFAs | 15–20% less methane in dairy cows; 5% increase in milk; improved feed efficiency | [113,173,174,175,176] |

| Improving water quality in aquaculture | Probiotics (B. subtilis, L. plantarum) suppress pathogens; enhance nutrient cycling; degrade organic matter; remove NH3 and NO2− | 20% reduction in shrimp mortality; 30% improved growth; fewer chemical treatments; healthier water | [176,177,178,179,180] |

| Reducing antibiotic usage | Competitive exclusion, bacteriocin production, immune modulation | Reduced disease incidence; 30% less post-weaning diarrhea in swine; improved growth performance; lower AMR spread | [184,185,186,187,188,189] |

| Sustainable farming practices | Optimize nutrient utilization; reduce nutrient excretion; improve gut absorption; use probiotic-treated manure | 10% better FCR in poultry; 20% less N and P excretion in swine; enhanced soil health; improved animal welfare | [190,191] |

| Molecular mechanisms of probiotic action | Ligand interactions with TLRs/NODs; activate MAPK/NF-κB pathways; SCFA production; histone modification; GPCR signaling | Up-regulation of immune, barrier, and anti-inflammatory genes; stronger gut/immune barrier; improved host resilience | [192,193,194,195,196] |

| Key pathogens and efficacy in each species—Cattle | Target E. coli O157, Salmonella, C. perfringens; Lactobacillus NP51, L. casei | 50% reduction in E. coli O157 shedding; reduced Salmonella counts | [72] |

| Key pathogens and efficacy in each species—Swine | Target ETEC, Salmonella, Lawsonia, Brachyspira; Lactobacillus reuteri, B. subtilis, Pediococcus | Reduced ETEC shedding (20% vs. 60% controls); reduced Salmonella translocation | [43,192] |

| Key pathogens and efficacy in each species—Poultry | Target Salmonella, Campylobacter, C. perfringens; Bacillus-based DFMs | 99% lower Salmonella colonization; 1–2 log10 reduction Campylobacter; 48–66% lower NE lesions | [6,99] |

| Key pathogens and efficacy in each species—Aquaculture | Target Vibrio spp., Aeromonas hydrophila; Bacillus spp., L. plantarum | 86% survival in Vibrio-challenged shrimp; 77.7% survival in fish; reduced pathogen load | [46,47,48] |

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ouwehand, A.C.; Salminen, S.; Isolauri, E. Probiotics: An Overview of Beneficial Effects. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2002, 82, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO Health and Nutritional Properties of Probiotics in Food Including Powder Milk with Live Lactic Acid Bacteria: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation 2021. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/a0512e/a0512e.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Joerger, R.D.; Ganguly, A. Current Status of the Preharvest Application of Pro- and Prebiotics to Farm Animals to Enhance the Microbial Safety of Animal Products. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberfroid, M. Prebiotics: The Concept Revisited. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 830S–837S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherdthong, A.; Wanapat, M.; Wachirapakorn, C. Influence of Urea Calcium Mixture Supplementation on Ruminal Fermentation Characteristics of Beef Cattle Fed on Concentrates Containing High Levels of Cassava Chips and Rice Straw. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2011, 163, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.; Burkholder, K. Application of Prebiotics and Probiotics in Poultry Production. Poult. Sci. 2003, 82, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yirga, H. The Use of Probiotics in Animal Nutrition. J. Probiotics Health 2015, 3, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, W.D.; Wiryawa, K.G.; Wina, E.; Widyastuti, Y.; Suharti, S.; Ridwan, R. Effects of Selected Lactobacillus plantarum as Probiotic on In Vitro Ruminal Fermentation and Microbial Population. Pak. J. Nutr. 2018, 17, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krehbiel, C.R.; Rust, S.R.; Zhang, G.; Gilland, S.E. Bacterial Direct-Fed Microbials in Ruminant Diets: Performance Response and Mode of Action. J. Anim. Sci. 2003, 81, E120–E132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyghebaert, G.; Ducatelle, R.; Immerseel, F.V. An Update on Alternatives to Antimicrobial Growth Promoters for Broilers. Vet. J. 2011, 187, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabir, S.M.L. The Role of Probiotics in the Poultry Industry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 3531–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.K.; Kim, S.-W.; Kim, M.H.; Upadhaya, S.D.; Kam, D.K.; Ha, J.K. Direct-Fed Microbials for Ruminant Animals. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 23, 1657–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Gong, T.; Jiang, Z.; Lu, Z.; Wang, Y. The Role of Probiotics in Alleviating Postweaning Diarrhea in Piglets from the Perspective of Intestinal Barriers. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 883107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Rather, I.A.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, T.; Jang, J.; Seo, J.; Lim, J.; Park, Y.-H. A Double-Blind, Placebo Controlled-Trial of a Probiotic Strain Lactobacillus sakei Probio-65 for the Prevention of Canine Atopic Dermatitis. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 25, 1966–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grześkowiak, Ł.; Endo, A.; Beasley, S.; Salminen, S. Microbiota and Probiotics in Canine and Feline Welfare. Anaerobe 2015, 34, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, L.; Xiao, L.; Fu, Y.; Shao, Z.; Jing, Z.; Yuan, J.; Xie, Y.; Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Geng, W. Neuroprotective Effects of Probiotics on Anxiety- and Depression-like Disorders in Stressed Mice by Modulating Tryptophan Metabolism and the Gut Microbiota. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 2895–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uyeno, Y.; Shigemori, S.; Shimosato, T. Effect of Probiotics/Prebiotics on Cattle Health and Productivity. Microbes Environ. 2015, 30, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaucheyras-Durand, F.; Durand, H. Probiotics in Animal Nutrition and Health. Benef. Microbes 2010, 1, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountzouris, K.C.; Tsitrsikos, P.; Palamidi, I.; Arvaniti, A.; Mohnl, M.; Schatzmayr, G.; Fegeros, K. Effects of Probiotic Inclusion Levels in Broiler Nutrition on Growth Performance, Nutrient Digestibility, Plasma Immunoglobulins, and Cecal Microflora Composition. Poult. Sci. 2010, 89, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowarah, R.; Verma, A.K.; Agarwal, N.; Singh, P.; Singh, B.R. Selection and Characterization of Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria and Its Impact on Growth, Nutrient Digestibility, Health and Antioxidant Status in Weaned Piglets. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, S.N.; Scorza, A.V.; Lappin, M.R. Effect of the Probiotic Enterococcus faecium SF68 on Presence of Diarrhea in Cats and Dogs Housed in an Animal Shelter. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2011, 25, 856–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozupone, C.A.; Stombaugh, J.I.; Gordon, J.I.; Jansson, J.K.; Knight, R. Diversity, Stability and Resilience of the Human Gut Microbiota. Nature 2012, 489, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frizzo, L.S.; Soto, L.P.; Zbrun, M.V.; Bertozzi, E.; Sequeira, G.; Armesto, R.R.; Rosmini, M.R. Lactic Acid Bacteria to Improve Growth Performance in Young Calves Fed Milk Replacer and Spray-Dried Whey Powder. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2010, 157, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowarah, R.; Verma, A.K.; Agarwal, N. The Use of Lactobacillus as an Alternative of Antibiotic Growth Promoters in Pigs: A Review. Anim. Nutr. 2017, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shija, V.M.; Amoah, K.; Cai, J. Effect of Bacillus Probiotics on the Immunological Responses of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus): A Review. Fishes 2023, 8, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Anh, N.D.Q.; Bossier, P.; Defoirdt, T. Norepinephrine and Dopamine Increase Motility, Biofilm Formation, and Virulence of Vibrio Harveyi. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derrien, M.; Van Hylckama Vlieg, J.E.T. Fate, Activity, and Impact of Ingested Bacteria within the Human Gut Microbiota. Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, R.L.; Minikhiem, D.; Kiely, B.; O’Mahony, L.; O’Sullivan, D.; Boileau, T.; Park, J.S. Clinical Benefits of Probiotic Canine-Derived Bifidobacterium animalis Strain AHC7 in Dogs with Acute Idiopathic Diarrhea. Vet. Ther. Res. Appl. Vet. Med. 2009, 10, 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, M.E.; Merenstein, D.J.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Rastall, R.A. Probiotics and Prebiotics in Intestinal Health and Disease: From Biology to the Clinic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collado, M.C.; Gueimonde, M.; Hernández, M.; Sanz, Y.; Salminen, S. Adhesion of Selected Bifidobacterium strains to Human Intestinal Mucus and the Role of Adhesion in Enteropathogen Exclusion. J. Food Prot. 2005, 68, 2672–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; O’Riordan, M.X.D. Regulation of Bacterial Pathogenesis by Intestinal Short-Chain Fatty Acids. In Advances in Applied Microbiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 85, pp. 93–118. ISBN 978-0-12-407672-3. [Google Scholar]

- Mackie, R.I.; White, B.A. Recent Advances in Rumen Microbial Ecology and Metabolism: Potential Impact on Nutrient Output. J. Dairy Sci. 1990, 73, 2971–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyte, M.; Daniels, K. A Microbial Endocrinology-Designed Discovery Platform to Identify Histamine-Degrading Probiotics: Proof of Concept in Poultry. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.K. Probiotics and Immunity: A Fish Perspective. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2010, 29, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuere, L.; Rombaut, G.; Sorgeloos, P.; Verstraete, W. Probiotic Bacteria as Biological Control Agents in Aquaculture. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000, 64, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mafra, D.; Borges, N.A.; Baptista, B.G.; Martins, L.F.; Borland, G.; Shiels, P.G.; Stenvinkel, P. What Can the Gut Microbiota of Animals Teach Us about the Relationship between Nutrition and Burden of Lifestyle Diseases? Nutrients 2024, 16, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyeh, D.D.; Ha, Y.; Park, T. Animal Feed Formulation: Rapid and Non-Destructive Measurement of Components from Waste by-Products. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2021, 274, 114848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, B.; Wang, W.; Arshad, M.I.; Khurshid, M.; Muzammil, S.; Rasool, M.H.; Nisar, M.A.; Alvi, R.F.; Aslam, M.A.; Qamar, M.U.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance: A Rundown of a Global Crisis. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018, 11, 1645–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, J.A.; McVey Neufeld, K.-A. Gut–Brain Axis: How the Microbiome Influences Anxiety and Depression. Trends Neurosci. 2013, 36, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, J.A.; Forsythe, P.; Chew, M.V.; Escaravage, E.; Savignac, H.M.; Dinan, T.G.; Bienenstock, J.; Cryan, J.F. Ingestion of Lactobacillus Strain Regulates Emotional Behavior and Central GABA Receptor Expression in a Mouse via the Vagus Nerve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 16050–16055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, E.A.; Knight, R.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Cryan, J.F.; Tillisch, K. Gut Microbes and the Brain: Paradigm Shift in Neuroscience. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 15490–15496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.D.; Pedroso, A.A.; Maurer, J.J. Bacterial Composition of a Competitive Exclusion Product and Its Correlation with Product Efficacy at Reducing Salmonella in Poultry. Front. Physiol. 2023, 13, 1043383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Fan, L.; Jiang, Y.; Doucette, C.; Fillmore, S. Antimicrobial Activity of Bacteriocin-Producing Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Cheeses and Yogurts. AMB Express 2012, 2, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, F.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, H.; Ren, S.; Guo, L.; Chen, Z.; Hrabchenko, N.; et al. Mechanisms and Applications of Probiotics in Prevention and Treatment of Swine Diseases. Porc. Health Manag. 2023, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayana, G.U.; Kamutambuko, R. Probiotics in Disease Management for Sustainable Poultry Production. Adv. Gut Microbiome Res. 2024, 2024, 4326438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, N.V. The Use of Probiotics in Aquaculture. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 119, 917–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyab, M.; Islam, W.; Waqas, W.; Zhang, Y. Probiotic–Vaccine Synergy in Fish Aquaculture: Exploring Microbiome-Immune Interactions for Enhanced Vaccine Efficacy. Biology 2025, 14, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, S.; Amoah, K.; Huang, Y.; Cai, J.; Wang, B.; Shija, V.M.; Jin, X.; Anokyewaa, M.A.; Jiang, M. Probiotics Application in Aquaculture: Its Potential Effects, Current Status in China and Future Prospects. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1455905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringø, E.; Olsen, R.E.; Gifstad, T.Ø.; Dalmo, R.A.; Amlund, H.; Hemre, G.-I.; Bakke, A.M. Prebiotics in Aquaculture: A Review. Aquac. Nutr. 2010, 16, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobi, N.; Vaseeharan, B.; Chen, J.-C.; Rekha, R.; Vijayakumar, S.; Anjugam, M.; Iswarya, A. Dietary Supplementation of Probiotic Bacillus licheniformis Dahb1 Improves Growth Performance, Mucus and Serum Immune Parameters, Antioxidant Enzyme Activity as Well as Resistance against Aeromonas hydrophila in Tilapia Oreochromis mossambicus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018, 74, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazado, C.C.; Caipang, C.M.A. Mucosal Immunity and Probiotics in Fish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014, 39, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Sánchez, T.; Balcázar, J.L.; Merrifield, D.L.; Carnevali, O.; Gioacchini, G.; De Blas, I.; Ruiz-Zarzuela, I. Expression of Immune-Related Genes in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Induced by Probiotic Bacteria during Lactococcus garvieae Infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2011, 31, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Xie, J.; Du, H.; McClements, D.J.; Xiao, H.; Li, L. Progress in Microencapsulation of Probiotics: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 857–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittisak, S.; Charoen, R.; Seamsin, S.; Buppha, J.; Ruangthong, T.; Muenkhling, S.; Riansa-ngawong, W.; Eadmusik, S.; Phattayakorn, K.; Jantrasee, S.; et al. Effects of Incorporated Collagen/Prebiotics and Different Coating Substances on the Survival Rate of Encapsulated Probiotics. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 34, 1383–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajam, R.; Subramanian, P. Encapsulation of Probiotics: Past, Present and Future. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2022, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasaekoopt, W.; Bhandari, B.; Deeth, H. Evaluation of Encapsulation Techniques of Probiotics for Yoghurt. Int. Dairy J. 2003, 13, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandrieux, J.R.S. Inflammatory Bowel Disease versus Chronic Enteropathy in Dogs: Are They One and the Same? J. Small Anim. Pract. 2016, 57, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA. Introduction of a Qualified Presumption of Safety (QPS) Approach for Assessment of Selected Microorganisms Referred to EFSA—Opinion of the Scientific Committee. EFSA J. 2007, 587, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, M.; Costa, S.G.V.A.O. Biosurfactants in Food Industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 18, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, J. Fiber and Prebiotics: Mechanisms and Health Benefits. Nutrients 2013, 5, 1417–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marková, K.; Kreisinger, J.; Vinkler, M. Are There Consistent Effects of Gut Microbiota Composition on Performance, Productivity and Condition in Poultry? Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leistikow, K.R.; Beattie, R.E.; Hristova, K.R. Probiotics beyond the Farm: Benefits, Costs, and Considerations of Using Antibiotic Alternatives in Livestock. Front. Antibiot. 2022, 1, 1003912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, C.; Zeng, X.; Yang, F.; Liu, H.; Qiao, S. Study and Use of the Probiotic Lactobacillus Reuteri in Pigs: A Review. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, C.G.; Cruz, E.M.R.M.D.; Bezerra, V.M.; Costa, J.T.G.; Lira, S.M.; Holanda, M.O.; Silva, J.Y.G.D.; Canabrava, N.D.V.; Silva, B.B.D.; Guedes, M.I.F. Prebióticos e Probióticos Na Saúde e No Tratamento de Doenças Intestinais: Uma Revisão Integrativa. Res. Soc. Dev. 2020, 9, e6459109071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.C.; Cookson, A.L.; McNabb, W.C.; Park, Z.; McCann, M.J.; Kelly, W.J.; Roy, N.C. Lactobacillus plantarum MB452 Enhances the Function of the Intestinal Barrier by Increasing the Expression Levels of Genes Involved in Tight Junction Formation. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgavi, D.P.; Forano, E.; Martin, C.; Newbold, C.J. Microbial Ecosystem and Methanogenesis in Ruminants. Animal 2010, 4, 1024–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, P.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, A.; Li, D.; Wang, C.-Z.; Wan, J.-Y.; Yao, H.; Yuan, C.-S. Probiotics Fortify Intestinal Barrier Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1143548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zanten, G.C.; Knudsen, A.; Röytiö, H.; Forssten, S.; Lawther, M.; Blennow, A.; Lahtinen, S.J.; Jakobsen, M.; Svensson, B.; Jespersen, L. The Effect of Selected Synbiotics on Microbial Composition and Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production in a Model System of the Human Colon. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyte, M. Probiotics Function Mechanistically as Delivery Vehicles for Neuroactive Compounds: Microbial Endocrinology in the Design and Use of Probiotics. BioEssays 2011, 33, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Gómez, M.X.; Martínez, I.; Bottacini, F.; O’Callaghan, A.; Ventura, M.; van Sinderen, D.; Hillmann, B.; Vangay, P.; Knights, D.; Hutkins, R.W.; et al. Stable Engraftment of Bifidobacterium longum AH1206 in the Human Gut Depends on Individualized Features of the Resident Microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinov, S.R.; Smidt, H.; Akkermans, A.D.L.; Casini, L.; Trevisi, P.; Mazzoni, M.; De Filippi, S.; Bosi, P.; De Vos, W.M. Feeding of Lactobacillus sobrius Reduces Escherichia coli F4 Levels in the Gut and Promotes Growth of Infected Piglets: Probiotic Treatment of ETEC Challenges in Piglets. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008, 66, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, G.-Y.; Yang, L.; Fu, Y.-Q.; Feng, J.-H.; Zhang, M.-H. Effects of Different Acute High Ambient Temperatures on Function of Hepatic Mitochondrial Respiration, Antioxidative Enzymes, and Oxidative Injury in Broiler Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2010, 89, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desnoyers, M.; Giger-Reverdin, S.; Bertin, G.; Duvaux-Ponter, C.; Sauvant, D. Meta-Analysis of the Influence of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Supplementation on Ruminal Parameters and Milk Production of Ruminants. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 1620–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wu, Z. Gut Probiotics and Health of Dogs and Cats: Benefits, Applications, and Underlying Mechanisms. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, M.G.; Kjos, M.; Veening, J.-W. How to Get (a)Round: Mechanisms Controlling Growth and Division of Coccoid Bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, R.R.; Gaghan, C.; Gorrell, K.; Sharif, S.; Taha-Abdelaziz, K. Probiotics as Alternatives to Antibiotics for the Prevention and Control of Necrotic Enteritis in Chickens. Pathogens 2022, 11, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Chen, F.; Xia, W.; Song, J.; Liang, J.; Yang, X. Characterization and Antimicrobial Potential of Bacteriocin-Producing Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from the Gut of Blattella germanica. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, e01203-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneitz, C.; Koivunen, E.; Tuunainen, P.; Valaja, J. The Effects of a Competitive Exclusion Product and Two Probiotics on Salmonella Colonization and Nutrient Digestibility in Broiler Chickens. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2016, 25, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Goyal, A. The Current Trends and Future Perspectives of Prebiotics Research: A Review. 3 Biotech 2012, 2, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxelin, M.; Tynkkynen, S.; Mattila-Sandholm, T.; De Vos, W.M. Probiotic and Other Functional Microbes: From Markets to Mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2005, 16, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zommiti, M.; Chikindas, M.L.; Ferchichi, M. Probiotics—Live Biotherapeutics: A Story of Success, Limitations, and Future Prospects—Not Only for Humans. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2020, 12, 1266–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, Y.; De Palma, G. Gut Microbiota and Probiotics in Modulation of Epithelium and Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Function. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 28, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yang, W.; Hostetler, A.; Schultz, N.; Suckow, M.A.; Stewart, K.L.; Kim, D.D.; Kim, H.S. Characterization of the Anti-Inflammatory Lactobacillus Reuteri BM36301 and Its Probiotic Benefits on Aged Mice. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, B.D.; Chowdhury, D.; Li, Z.; Pan, M.; Peng, T.; Chen, J.; Huang, W.; et al. Probiotic Bacteria-Released Extracellular Vesicles Enhance Macrophage Phagocytosis in Polymicrobial Sepsis by Activating the FPR1/2 Pathway. Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, Z.; İLk, Y.; Yildirim, M.; Tokatli, K.; Öncül, N. Inhibitory Effect of Enterocin KP in Combination with Sublethal Factors on Escherichia coli O157:H7 or Salmonella typhimurium in BHI Broth and UHT Milk. Turk. J. Biol. 2014, 38, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, S.E.; Higgins, J.P.; Wolfenden, A.D.; Henderson, S.N.; Torres-Rodriguez, A.; Tellez, G.; Hargis, B. Evaluation of a Lactobacillus-Based Probiotic Culture for the Reduction of Salmonella enteritidis in Neonatal Broiler Chicks. Poult. Sci. 2008, 87, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanshir, N.; Hosseini, G.N.G.; Sadeghi, M.; Esmaeili, R.; Satarikia, F.; Ahmadian, G.; Allahyari, N. Evaluation of the Function of Probiotics, Emphasizing the Role of Their Binding to the Intestinal Epithelium in the Stability and Their Effects on the Immune System. Biol. Proced. Online 2021, 23, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, M.; Sagayama, R.; Yamawaki, Y.; Yamaguchi, M.; Katsumi, H.; Yamamoto, A. Activation of Host Immune Cells by Probiotic-Derived Extracellular Vesicles via TLR2-Mediated Signaling Pathways. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2022, 45, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, H.-Z.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Ren, L.-F.; Li, Z.-J.; Zhang, L. How Do Intestinal Probiotics Restore the Intestinal Barrier? Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 929346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Kasper, L.H. The Role of Microbiome in Central Nervous System Disorders. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2014, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantis, N.J.; Rol, N.; Corthésy, B. Secretory IgA’s Complex Roles in Immunity and Mucosal Homeostasis in the Gut. Mucosal Immunol. 2011, 4, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuvelin, E.; Lebreton, C.; Grangette, C.; Pot, B.; Cerf-Bensussan, N.; Heyman, M. Mechanisms Involved in Alleviation of Intestinal Inflammation by Bifidobacterium Breve Soluble Factors. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furusawa, Y.; Obata, Y.; Fukuda, S.; Endo, T.A.; Nakato, G.; Takahashi, D.; Nakanishi, Y.; Uetake, C.; Kato, K.; Kato, T.; et al. Commensal Microbe-Derived Butyrate Induces the Differentiation of Colonic Regulatory T Cells. Nature 2013, 504, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westfall, S.; Caracci, F.; Estill, M.; Frolinger, T.; Shen, L.; Pasinetti, G.M. Chronic Stress-Induced Depression and Anxiety Priming Modulated by Gut-Brain-Axis Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 670500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.-I.; Cho, S.; Jeon, E.; Park, M.; Chae, B.; Ditengou, I.C.P.; Choi, N.-J. The Effect of Probiotics on Intestinal Tight Junction Protein Expression in Animal Models: A Meta-Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulluwishewa, D.; Anderson, R.C.; McNabb, W.C.; Moughan, P.J.; Wells, J.M.; Roy, N.C. Regulation of Tight Junction Permeability by Intestinal Bacteria and Dietary Components. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.; Niu, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, W. Effects of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Var. Boulardii on Growth, Incidence of Diarrhea, Serum Immunoglobulins, and Rectal Microbiota of Suckling Dairy Calves. Livest. Sci. 2022, 258, 104875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouvêa, V.N.D.; Biehl, M.V.; Ferraz Junior, M.V.D.C.; Moreira, E.M.; Faleiro Neto, J.A.; Westphalen, M.F.; Oliveira, G.B.; Ferreira, E.M.; Polizel, D.M.; Pires, A.V. Effects of Soybean Oil or Various Levels of Whole Cottonseed on Intake, Digestibility, Feeding Behavior, and Ruminal Fermentation Characteristics of Finishing Beef Cattle. Livest. Sci. 2021, 244, 104390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Zeng, B.; Zhou, C.; Liu, M.; Fang, Z.; Xu, X.; Zeng, L.; Chen, J.; Fan, S.; Du, X.; et al. Gut Microbiome Remodeling Induces Depressive-like Behaviors through a Pathway Mediated by the Host’s Metabolism. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hack, M.E.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Shafi, M.E.; Qattan, S.Y.A.; Batiha, G.E.; Khafaga, A.F.; Abdel-Moneim, A.E.; Alagawany, M. Probiotics in Poultry Feed: A Comprehensive Review. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 104, 1835–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Goh, T.W.; Kang, M.G.; Choi, H.J.; Yeo, S.Y.; Yang, J.; Huh, C.S.; Kim, Y.Y.; Kim, Y. Perspectives and Advances in Probiotics and the Gut Microbiome in Companion Animals. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2022, 64, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, S.; Ali, S.; Riaz, S.; Sardar, I.; Farooq, M.A.; Sajjad, A. Chemopreventive Role of Probiotics against Cancer: A Comprehensive Mechanistic Review. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 799–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motevaseli, E.; Dianatpour, A.; Ghafouri-Fard, S. The Role of Probiotics in Cancer Treatment: Emphasis on Their In Vivo and In Vitro Anti-Metastatic Effects. Int. J. Mol. Cell. Med. 2017, 6, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sung, C.Y.J.; Lee, N.; Ni, Y.; Pihlajamäki, J.; Panagiotou, G.; El-Nezami, H. Probiotics Modulated Gut Microbiota Suppresses Hepatocellular Carcinoma Growth in Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E1306–E1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, H.M.; Jonkers, D.; Venema, K.; Vanhoutvin, S.; Troost, F.J.; Brummer, R.-J. Review Article: The Role of Butyrate on Colonic Function. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 27, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Chen, H.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.Q.; Chen, W. Review of the Roles of Conjugated Linoleic Acid in Health and Disease. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 15, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, A.; Van Sinderen, D. Bifidobacteria and Their Role as Members of the Human Gut Microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, C.-Y.; Chan, W.-T.; Jiang, C.-B.; Cheng, M.-L.; Liu, C.-Y.; Chang, S.-W.; Chiang Chiau, J.-S.; Lee, H.-C. Amelioration of Chemotherapy-Induced Intestinal Mucositis by Orally Administered Probiotics in a Mouse Model. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun, H.M.; Li, S.; Yoon, I.; Meale, S.J.; Azevedo, P.A.; Khafipour, E.; Plaizier, J.C. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Fermentation Products (SCFP) Stabilize the Ruminal Microbiota of Lactating Dairy Cows during Periods of a Depressed Rumen pH. BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, F.; Neshat, M.; Pourjafar, H.; Jafari, S.M.; Samakkhah, S.A.; Mirzakhani, E. The Role of Probiotics and Prebiotics in Modulating of the Gut-Brain Axis. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1173660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, C.; Gardiner, G.; Meehan, H.; Collins, K.; Fitzgerald, G.; Lynch, P.B.; Ross, R.P. Market Potential for Probiotics. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 73, 476s–483s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaucheyras-Durand, F.; Walker, N.D.; Bach, A. Effects of Active Dry Yeasts on the Rumen Microbial Ecosystem: Past, Present and Future. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2008, 145, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Mal, G.; Kalra, R.S.; Marotta, F. Probiotics Against Methanogens and Methanogenesis. In Probiotics as Live Biotherapeutics for Veterinary and Human Health, Volume 1; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 355–376. ISBN 978-3-031-65454-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Sun, H.; Gao, H.; Xia, Y.; Zan, L.; Zhao, C. A Meta-Analysis on the Effects of Probiotics on the Performance of Pre-Weaning Dairy Calves. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangiano, L.R.; Yohe, T.T.; Steele, M.A.; Renaud, D.L. Invited Review: Strategic Use of Microbial-Based Probiotics and Prebiotics in Dairy Calf Rearing. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2020, 36, 630–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Doyle, M.P.; Harmon, B.G.; Brown, C.A.; Mueller, P.O.E.; Parks, A.H. Reduction of Carriage of Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in Cattle by Inoculation with Probiotic Bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1998, 36, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brashears, M.M.; Galyean, M.L.; Loneragan, G.H.; Mann, J.E.; Killinger-Mann, K. Prevalence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Performance by Beef Feedlot Cattle Given Lactobacillus Direct-Fed Microbials. J. Food Prot. 2003, 66, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Moneim, A.E.-M.E.A.; El-Wardany, I.; Abu-Taleb, A.M.; Wakwak, M.M.; Ebeid, T.A.; Saleh, A.A. Assessment of In Ovo Administration of Bifidobacterium bifidum and Bifidobacterium longum on Performance, Ileal Histomorphometry, Blood Hematological, and Biochemical Parameters of Broilers. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2020, 12, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Xiao, C.; Tian, B.; Dorthe, S.; Meuter, A.; Song, B.; Song, Z. Dietary Probiotic Based on a Dual-Strain Bacillus subtilis Improves Immunity, Intestinal Health, and Growth Performance of Broiler Chickens. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Lu, Y.; Li, D.; Yan, C.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Du, R.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Probiotic Mediated Intestinal Microbiota and Improved Performance, Egg Quality and Ovarian Immune Function of Laying Hens at Different Laying Stage. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1041072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhu, C.; Xiong, Y.; Yan, K.; He, S. Effects of Bacillus subtilis and Lactobacillus on Growth Performance, Serum Biochemistry, Nutrient Apparent Digestibility, and Cecum Flora in Heat-Stressed Broilers. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2024, 68, 2705–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Yan, F.-F.; Hu, J.-Y.; Mohammed, A.; Cheng, H.-W. Bacillus subtilis-Based Probiotic Improves Skeletal Health and Immunity in Broiler Chickens Exposed to Heat Stress. Animals 2021, 11, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, S.; Roy, B.; Samanta, I.; Pradhan, S.; Soren, S. Efficacy of Bacillus xiamenensis Probiotic Supplementation on Growth Performance and Gut Health of Commercial Broiler Chickens. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Anim. Husb. 2025, 10, 01–06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.W.; Lee, S.H.; Lillehoj, H.S.; Li, G.X.; Jang, S.I.; Babu, U.S.; Park, M.S.; Kim, D.K.; Lillehoj, E.P.; Neumann, A.P.; et al. Effects of Direct-Fed Microbials on Growth Performance, Gut Morphometry, and Immune Characteristics in Broiler Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2010, 89, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, K.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; Qi, G.; Gao, J.; Zhang, H.; Wu, S. Effects of Dietary Supplementation with Bacillus subtilis, as an Alternative to Antibiotics, on Growth Performance, Serum Immunity, and Intestinal Health in Broiler Chickens. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 786878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-Q.; Zhu, Y.-H.; Zhang, H.-F.; Yue, Y.; Cai, Z.-X.; Lu, Q.-P.; Zhang, L.; Weng, X.-G.; Zhang, F.-J.; Zhou, D.; et al. Risks Associated with High-Dose Lactobacillus rhamnosus in an Escherichia coli Model of Piglet diarrhoea: Intestinal Microbiota and Immune Imbalances. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Li, S.; Tang, W.; Diao, H.; Zhang, H.; Yan, H.; Liu, J. Dietary Complex Probiotic Supplementation Changed the Composition of Intestinal Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Improved the Average Daily Gain of Growing Pigs. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Ronquillo, M.; Villegas-Estrada, D.; Robles-Jimenez, L.E.; Garcia Herrera, R.A.; Villegas-Vázquez, V.L.; Vargas-Bello-Pérez, E. Effect of the Inclusion of Bacillus spp. in Growing–Finishing Pigs’ Diets: A Meta-Analysis. Animals 2022, 12, 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuntapaitoon, M.; Chatthanathon, P.; Palasuk, M.; Wilantho, A.; Ruampatana, J.; Tongsima, S.; Settachaimongkon, S.; Somboonna, N. Maternal Clostridium Butyricum Supplementation during Late Gestation and Lactation Enhances Gut Bacterial Communities, Milk Quality, and Reduces Piglet Diarrhea. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2025, 27, 2933–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.M.C.; Andretta, I.; Franceschi, C.H.; Kipper, M.; Mariani, A.; Stefanello, T.; Carvalho, C.; Vieira, J.; Moura Rocha, L.; Ribeiro, A.M.L. Effects of Multistrain Probiotic Supplementation on Sows’ Emotional and Cognitive States and Progeny Welfare. Animals 2024, 14, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.; Huang, W.; Li, Y.; Jin, H.; Kwok, L.-Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, H. Probiotics Alleviate Constipation and Inflammation in Late Gestating and Lactating Sows. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2023, 9, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.; Chang, S.Y.; Bogere, P.; Won, K.; Choi, J.-Y.; Choi, Y.-J.; Lee, H.K.; Hur, J.; Park, B.-Y.; Kim, Y.; et al. Beneficial Roles of Probiotics on the Modulation of Gut Microbiota and Immune Response in Pigs. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.C.; Weese, J.S. The Equine Intestinal Microbiome. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2012, 13, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gookin, J.L.; Strong, S.J.; Bruno-Bárcena, J.M.; Stauffer, S.H.; Williams, S.; Wassack, E.; Azcarate-Peril, M.A.; Estrada, M.; Seguin, A.; Balzer, J.; et al. Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial of Feline-Origin Enterococcus Hirae Probiotic Effects on Preventative Health and Fecal Microbiota Composition of Fostered Shelter Kittens. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 923792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perricone, V.; Sandrini, S.; Irshad, N.; Comi, M.; Lecchi, C.; Savoini, G.; Agazzi, A. The Role of Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae in Supporting Gut Health in Horses: An Updated Review on Its Effects on Digestibility and Intestinal and Fecal Microbiota. Animals 2022, 12, 3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, C.G.; Gibb, Z.; Harnett, J.E. The Safety, Tolerability and Efficacy of Probiotic Bacteria for Equine Use. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2021, 99, 103407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoster, A.; Weese, J.S.; Guardabassi, L. Probiotic Use in Horses—What Is the Evidence for Their Clinical Efficacy? J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2014, 28, 1640–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganda, E.; Chakrabarti, A.; Sardi, M.I.; Tench, M.; Kozlowicz, B.K.; Norton, S.A.; Warren, L.K.; Khafipour, E. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Fermentation Product Improves Robustness of Equine Gut Microbiome upon Stress. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1134092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steelman, S.M.; Chowdhary, B.P.; Dowd, S.; Suchodolski, J.; Janečka, J.E. Pyrosequencing of 16S rRNA Genes in Fecal Samples Reveals High Diversity of Hindgut Microflora in Horses and Potential Links to Chronic Laminitis. BMC Vet. Res. 2012, 8, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrypnik, K.; Bogdański, P.; Schmidt, M.; Suliburska, J. The Effect of Multispecies Probiotic Supplementation on Iron Status in Rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2019, 192, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchin, S.; Bertin, L.; Bonazzi, E.; Lorenzon, G.; De Barba, C.; Barberio, B.; Zingone, F.; Maniero, D.; Scarpa, M.; Ruffolo, C.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Human Health: From Metabolic Pathways to Current Therapeutic Implications. Life 2024, 14, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, C. Modulation of Gut Microbiota and Immune System by Probiotics, Pre-Biotics, and Post-Biotics. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 634897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Tang, C.; Sun, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Cui, Q.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Su, Y.; Mao, Y.; et al. Protective Effects of SCFAs on Organ Injury and Gut Microbiota Modulation in Heat-Stressed Rats. Ann. Microbiol. 2024, 74, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenman, L.K.; Burcelin, R.; Lahtinen, S. Establishing a Causal Link between Gut Microbes, Body Weight Gain and Glucose Metabolism in Humans—Towards Treatment with Probiotics. Benef. Microbes 2016, 7, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Lv, X.; Ze, X.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, X.; He, R.; Fan, J.; Zhang, M.; Sun, B.; Wang, F.; et al. Combined Probiotics Attenuate Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress-Induced Depressive-like and Anxiety-like Behaviors in Rats. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 990465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, L.; Rose, J.; Gosling, S.; Holmes, M. Efficacy of a Probiotic-Prebiotic Supplement on Incidence of Diarrhea in a Dog Shelter: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2017, 31, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucher, L.; Leduc, L.; Leclère, M.; Costa, M.C. Current Understanding of Equine Gut Dysbiosis and Microbiota Manipulation Techniques: Comparison with Current Knowledge in Other Species. Animals 2024, 14, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.; Cui, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Deng, B.; Han, S. The Function of Probiotics and Prebiotics on Canine Intestinal Health and Their Evaluation Criteria. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmalberg, J.; Montalbano, C.; Morelli, G.; Buckley, G.J. A Randomized Double Blinded Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial of a Probiotic or Metronidazole for Acute Canine Diarrhea. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappin, M.R. Clinical and Research Experiences with Probiotics in Cats. 28 March 2011. Available online: https://www.dvm360.com/view/clinical-and-research-experiences-with-probiotics-cats-sponsored-nestl-purina (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- White, R.; Atherly, T.; Guard, B.; Rossi, G.; Wang, C.; Mosher, C.; Webb, C.; Hill, S.; Ackermann, M.; Sciabarra, P.; et al. Randomized, Controlled Trial Evaluating the Effect of Multi-Strain Probiotic on the Mucosal Microbiota in Canine Idiopathic Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gut Microbes 2017, 8, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Huang, W.; Hou, Q.; Kwok, L.-Y.; Laga, W.; Wang, Y.; Ma, H.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, H. Oral Administration of Compound Probiotics Improved Canine Feed Intake, Weight Gain, Immunity and Intestinal Microbiota. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socha, P.A.; Socha, B.M. The Impact of a Multi-Strain Probiotic Supplementation on Puppies Manifesting Diarrhoeic Symptoms During the Initial Seven Days of Life. Animals 2025, 15, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Cui, Y.; Mei, X.; Li, L.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y. Effect of Dietary Composite Probiotic Supplementation on the Microbiota of Different Oral Sites in Cats. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernimont, S.M.; Radosevich, J.; Jackson, M.I.; Ephraim, E.; Badri, D.V.; MacLeay, J.M.; Jewell, D.E.; Suchodolski, J.S. The Effects of Nutrition on the Gastrointestinal Microbiome of Cats and Dogs: Impact on Health and Disease. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Gallego, C.; Junnila, J.; Männikkö, S.; Hämeenoja, P.; Valtonen, E.; Salminen, S.; Beasley, S. A Canine-Specific Probiotic Product in Treating Acute or Intermittent Diarrhea in Dogs: A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Efficacy Study. Vet. Microbiol. 2016, 197, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman-Davis, R.; Figurska, M.; Cywinska, A. Gut Microbiota Manipulation in Foals—Naturopathic Diarrhea Management, or Unsubstantiated Folly? Pathogens 2021, 10, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Older, C.E.; Diesel, A.B.; Heseltine, J.C.; Friedeck, A.; Hedke, C.; Pardike, S.; Breitreiter, K.; Rossi, M.A.; Messamore, J.; Bammert, G.; et al. Cytokine Expression in Feline Allergic Dermatitis and Feline Asthma. Vet. Dermatol. 2021, 32, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGilloway, M.; Manley, S.; Aho, A.; Heeringa, K.N.; Whitacre, L.; Lou, Y.; Squires, E.J.; Pearson, W. Dietary Fermentation Product of Aspergillus oryzae Prevents Increases in Gastrointestinal Permeability (‘Leaky Gut’) in Horses Undergoing Combined Transport and Exercise. Animals 2023, 13, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncho, C.M.; Kim, S.-H.; Rang, S.A.; Lee, S.S. A Meta-Analysis of Probiotic Interventions to Mitigate Ruminal Methane Emissions in Cattle: Implications for Sustainable Livestock Farming. Animal 2024, 18, 101180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, K.N.; Banerjee, G. Recent Studies on Probiotics as Beneficial Mediator in Aquaculture: A Review. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2020, 81, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craven, S.E.; Stern, N.J.; Bailey, J.S.; Cox, N.A. Incidence of Clostridium Perfringens in Broiler Chickens and Their Environment during Production and Processing. Avian Dis. 2001, 45, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G.; Das, B.C.; Jose, S.; Rejish Kumar, V.J. Bacillus as an Aquaculture Friendly Microbe. Aquac. Int. 2021, 29, 323–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Fu, W.; Lu, R.; Pan, C.; Yi, G.; Zhang, X.; Rao, Z. Characterization of Bacillus subtilis Ab03 for Efficient Ammonia Nitrogen Removal. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanuf. 2022, 2, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proespraiwong, P.; Mavichak, R.; Imaizumi, K.; Hirono, I.; Unajak, S. Evaluation of Bacillus spp. as Potent Probiotics with Reduction in AHPND-Related Mortality and Facilitating Growth Performance of Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) Farms. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, K.; Bisani, K.; Prajapati, H.; Prajapati, S.; Agrawal, D.; Singh, S.; Saraf, M.; Goswami, D. Advances in Probiotics Research: Mechanisms of Action, Health Benefits, and Limitations in Applications. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanuf. 2024, 4, 386–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance 2016. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241509763 (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- O’Mahony, D.; Murphy, S.; Boileau, T.; Park, J.; O’Brien, F.; Groeger, D.; Konieczna, P.; Ziegler, M.; Scully, P.; Shanahan, F.; et al. Bifidobacterium animalis AHC7 Protects against Pathogen-Induced NF-κB Activation in Vivo. BMC Immunol. 2010, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggriawan, R.; Paramita Lokapirnasari, W.; Hidanah, S.; Anam Al Arif, M.; Ayu Candra, D. The Role of Probiotics as Alternatives to Antibiotic Growth Promoters in Enhancing Poultry Performance. J. Anim. Health Prod. 2024, 12, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyanathan, J.; Martin, C.; Morgavi, D.P. The Use of Direct-Fed Microbials for Mitigation of Ruminant Methane Emissions: A Review. Animal 2014, 8, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabighane, B.; Salem, A.Z.M.; Mirzaei Aghjehgheshlagh, F.; Mahdavi, A.; Zarei, A.; Elghandour, M.M.M.Y.; López, S. Environmental Efficiency of Saccharomyces cerevisiae on Methane Production in Dairy and Beef Cattle via a Meta-Analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 3651–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Diaz, J. Modulation of Immunity and Inflammatory Gene Expression in the Gut, in Inflammatory Diseases of the Gut and in the Liver by Probiotics. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 15632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.-R.; Lee, S.; Jung, H.; Miller, D.N.; Chen, R. Enteric Methane Emissions and Animal Performance in Dairy and Beef Cattle Production: Strategies, Opportunities, and Impact of Reducing Emissions. Animals 2022, 12, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, E.N. Energy Contributions of Volatile Fatty Acids from the Gastrointestinal Tract in Various Species. Physiol. Rev. 1990, 70, 567–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmikasoglou, E.; Sumadong, P.; Dagaew, G.; Johnson, M.L.; Vinyard, J.R.; Salas-Solis, G.; Siregar, M.; Faciola, A.P. Effects of Bacillus subtilis on in Vitro Ruminal Fermentation and Methane Production. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2024, 8, txae054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrune, M.; Bach, A.; Ruiz-Moreno, M.; Stern, M.D.; Linn, J.G. Effects of Saccharomyces cerevisiae on Ruminal pH and Microbial Fermentation in Dairy Cows. Livest. Sci. 2009, 124, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkholder, J.; Libra, B.; Weyer, P.; Heathcote, S.; Kolpin, D.; Thorne, P.S.; Wichman, M. Impacts of Waste from Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations on Water Quality. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowiak, P.; Śliżewska, K. The Role of Probiotics, Prebiotics and Synbiotics in Animal Nutrition. Gut Pathog. 2018, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, J.M.; Drouillard, J.S.; Baker, A.N.; De Aguiar Veloso, V.; Kang, Q.; Kastner, J.J.; Gragg, S.E. Impact of the Probiotic Organism Megasphaera elsdenii on Escherichia coli O157:H7 Prevalence in Finishing Cattle. J. Food Prot. 2023, 86, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.-Y.; Ju, H.-J.; Huang, M.-Y.; Kuo, Q.-M.; Su, W.-T. Optimal Nitrite Degradation by Isolated Bacillus subtilis Sp. N4 and Applied for Intensive Aquaculture Water Quality Management with Immobilized Strains. J. Environ. Manage. 2025, 374, 123896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, M.A.; Fathallah, M.A.; Elzoghby, M.A.; Salem, M.G.; Helmy, M.S. Influence of Probiotics on Water Quality in Intensified Litopenaeus vannamei Ponds under Minimum-Water Exchange. AMB Express 2022, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, L.H.B.; Lauridsen, C.; Nielsen, B.; Jørgensen, L.; Canibe, N. Impact of Early Inoculation of Probiotics to Suckling Piglets on Postweaning Diarrhoea—A Challenge Study with Enterotoxigenic E. coli F18. animal 2022, 16, 100667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Mun, S.-H.; Han, D.-W.; Kang, J.-H.; An, J.-U.; Hwang, C.-Y.; Cho, S. Probiotics Ameliorate Atopic Dermatitis by Modulating the Dysbiosis of the Gut Microbiota in Dogs. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. Drug-Resistant Infections: A Threat to Our Economic Future; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Neveling, D.P.; Van Emmenes, L.; Ahire, J.J.; Pieterse, E.; Smith, C.; Dicks, L.M.T. Effect of a Multi-Species Probiotic on the Colonisation of Salmonella in Broilers. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2020, 12, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psichas, A.; Sleeth, M.L.; Murphy, K.G.; Brooks, L.; Bewick, G.A.; Hanyaloglu, A.C.; Ghatei, M.A.; Bloom, S.R.; Frost, G. The Short Chain Fatty Acid Propionate Stimulates GLP-1 and PYY Secretion via Free Fatty Acid Receptor 2 in Rodents. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 39, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolhurst, G.; Heffron, H.; Lam, Y.S.; Parker, H.E.; Habib, A.M.; Diakogiannaki, E.; Cameron, J.; Grosse, J.; Reimann, F.; Gribble, F.M. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Stimulate Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Secretion via the G-Protein–Coupled Receptor FFAR2. Diabetes 2012, 61, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefevre, M.; Racedo, S.M.; Ripert, G.; Housez, B.; Cazaubiel, M.; Maudet, C.; Jüsten, P.; Marteau, P.; Urdaci, M.C. Probiotic Strain Bacillus subtilis CU1 Stimulates Immune System of Elderly during Common Infectious Disease Period: A Randomized, Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study. Immun. Ageing 2015, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanasiri, A.K.S.; Jaramillo-Torres, A.; Chikwati, E.M.; Forberg, T.; Krogdahl, Å.; Kortner, T.M. Effects of Dietary Supplementation with Prebiotics and Pediococcus acidilactici on Gut Health, Transcriptome, Microbiota, and Metabolome in Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar L.) after Seawater Transfer. Anim. Microbiome 2023, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, C.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Ran, C.; He, S.; Zhou, Z. Impact of Lactobacillus casei BL23 on the Host Transcriptome, Growth and Disease Resistance in Larval Zebrafish. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, M.; Dupuis, M.; Gagnon, N.; Nadeau, É.; Matte, J.J.; Goulet, J.; Fairbrother, J.M. Administration of Pediococcus acidilactici or Saccharomyces cerevisiae boulardii Modulates Development of Porcine Mucosal Immunity and Reduces Intestinal Bacterial Translocation after Escherichia coli Challenge1,2. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87, 922–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, E.T.; Gabler, N.K.; Burrough, E.R. Highly Fermentable Fiber Alters Fecal Microbiota and Mitigates Swine Dysentery Induced by Brachyspira hyodysenteriae. Animals 2021, 11, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, D. Defined Competitive Exclusion Cultures in the Prevention of Enteropathogen colonisation in Poultry and Swine. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2002, 81, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, L.; Guo, F.; Liu, Y.; Pham, V.H.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Z. Probiotics Bacillus Licheniformis Improves Intestinal Health of Subclinical Necrotic Enteritis-Challenged Broilers. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 623739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisener, L.V.; Sargeant, J.M.; O’Connor, A.M.; Faires, M.C.; Glass-Kaastra, S.K. The Use of Direct-Fed Microbials to Reduce Shedding of Escherichia coli O157 in Beef Cattle: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Zoonoses Public Health 2015, 62, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szott, V.; Reichelt, B.; Friese, A.; Roesler, U. A Complex Competitive Exclusion Culture Reduces Campylobacter jejuni Colonization in Broiler Chickens at Slaughter Age In Vivo. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mârza, S.M.; Munteanu, C.; Papuc, I.; Radu, L.; Purdoiu, R.C. The Role of Probiotics in Enhancing Animal Health: Mechanisms, Benefits, and Applications in Livestock and Companion Animals. Animals 2025, 15, 2986. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15202986

Mârza SM, Munteanu C, Papuc I, Radu L, Purdoiu RC. The Role of Probiotics in Enhancing Animal Health: Mechanisms, Benefits, and Applications in Livestock and Companion Animals. Animals. 2025; 15(20):2986. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15202986

Chicago/Turabian StyleMârza, Sorin Marian, Camelia Munteanu, Ionel Papuc, Lăcătuş Radu, and Robert Cristian Purdoiu. 2025. "The Role of Probiotics in Enhancing Animal Health: Mechanisms, Benefits, and Applications in Livestock and Companion Animals" Animals 15, no. 20: 2986. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15202986

APA StyleMârza, S. M., Munteanu, C., Papuc, I., Radu, L., & Purdoiu, R. C. (2025). The Role of Probiotics in Enhancing Animal Health: Mechanisms, Benefits, and Applications in Livestock and Companion Animals. Animals, 15(20), 2986. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15202986