Simple Summary

Swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus is an emerging enteropathogenic coronavirus with high lethality in lactating piglets and strong cross-species transmission ability. As it is a new threat to the swine industry, research and understanding of this virus are still in the early stages. There are currently no commercially available vaccines that prevent swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus (SADS-CoV). In this review, we systematically analyzed the structural components of the virus, input and possible modes of transmission, and the cross-species transmissibility of the virus to characterize its risk level. We also summarized host-dependent factors in the virus infection process, as well as the viral regulation of host cell life processes. Finally, we discussed preventive and therapeutic measures that can be adopted in the future. Through this review, we aim to contribute to a better understanding of this porcine enterovirus and to subsequent research.

Abstract

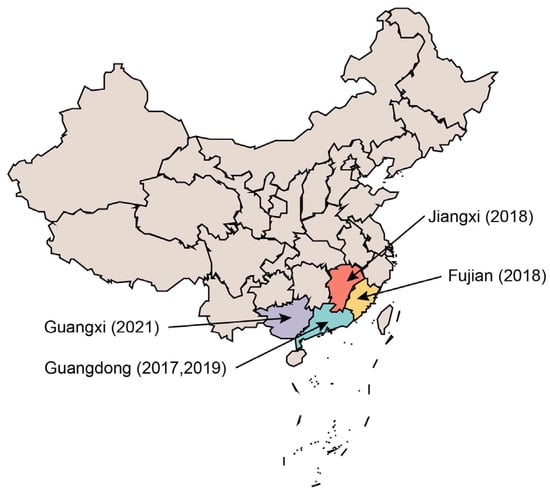

Swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus (SADS-CoV) is a virulent pathogen that causes acute diarrhea in piglets. The virus was first discovered in Guangdong Province, China, in 2017 and has since emerged in Jiangxi, Fujian, and Guangxi Provinces. The outbreak exhibited a localized and sporadic pattern, with no discernable temporal continuity. The virus can infect human progenitor cells and demonstrates considerable potential for cross-species transmission, representing a potential risk for zoonotic transmission. Therefore, continuous surveillance of and comprehensive research on SADS-CoV are imperative. This review provides an overview of the temporal and evolutionary features of SADS-CoV outbreaks, focusing on the structural characteristics of the virus, which serve as the basis for discussing its potential for interspecies transmission. Additionally, the review summarizes virus–host interactions, including the effects on host cells, as well as apoptotic and autophagic behaviors, and discusses prevention and treatment modalities for this viral infection.

1. Introduction

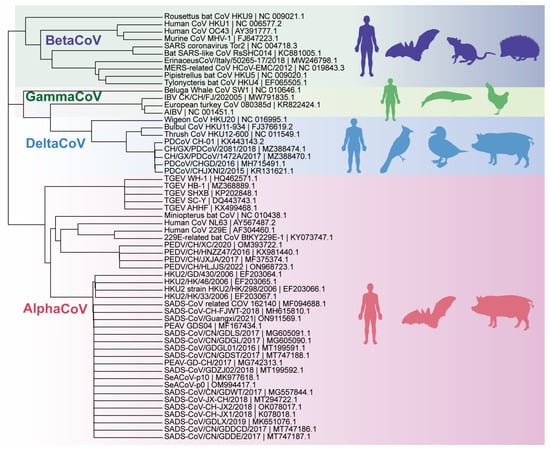

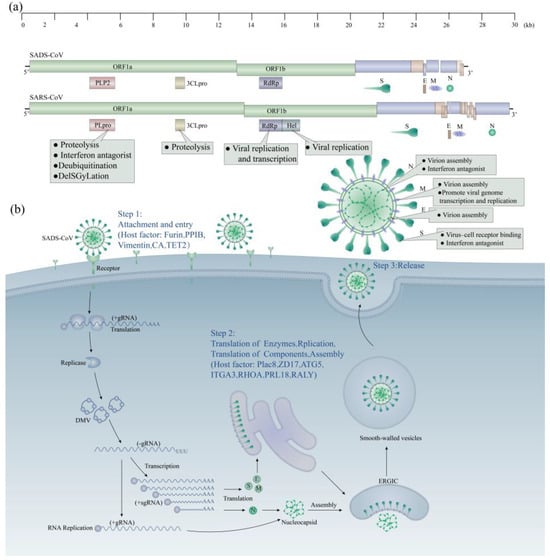

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are the largest positive-sense RNA viruses, belonging to the family Coronaviridae and the order Nidovirales. The virus was named after its specialized crown-like structure, as observed in electron microscope images [1,2]. Coronaviruses have the largest genome of any known RNA virus, with a genome size of about 26–32 KB [3]. All coronaviruses have a similar organization and expression of their genomes [2]. First, there is the open reading frame (ORF) 1a/b, which can encode 16 non-structural proteins and occupies about two-thirds of the genome length [4], starting from the 5′ end, followed by the structural proteins spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N), and finally the ORF, expressing non-structural proteins near the 3′ end [5]. Based on the serology and the genome, the subfamily of coronaviruses can be divided into four genera: α, β, γ, and δ [6]. The coronavirus genome encodes various proteins, including structural, non-structural, and accessory proteins. Coronaviruses, like other RNA viruses, have a high mutation rate and a strong tendency to reorganize despite possessing a proofreading-active ribonucleic acid exonuclease (ExoN)-containing non-structural protein (nsp14) [7]. These characteristics allow them to overcome host species barriers and to adapt to new hosts. This has resulted in repeated demonstrations of their zoonotic and terrestrial transmission capabilities, such as those of COVID-19, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV), and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), which originated in bats and were transmitted to humans via intermediate mammalian hosts [8]. Because virus epidemics pose potential risks to human health and economic and social development, it is crucial to recognize the virus and implement proactive measures to reduce or eliminate its impact.

Porcine coronavirus infections have resulted in significant economic losses in the swine farming sector [9]. For example, in October 2010, coronavirus infections in pigs cumulatively led to the deaths of more than one million piglets in China [10]; the 2013 outbreak of PEDV in the United States, Canada, and Mexico killed more than eight million piglets in the United States alone [11]; and in the first half of 2017, the first outbreak of SADS-CoV led to the deaths of more than 20,000 piglets [12]. These infections are caused by six different coronaviruses: porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV), porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), porcine delta coronavirus (PDCoV), porcine acute diarrheal syndrome coronavirus (SADS-CoV), porcine hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus (PHEV), and porcine respiratory coronavirus (PRCV) [13]. These viruses belong to three genera within the subfamily Orthocoronaviridae. PEDV, TGEV, SADS-CoV, and PRCV belong to the genus α-coronavirus, whereas PHEV and PDCoV belong to the genera β-coronavirus and δ-coronavirus, respectively. Different genera of viruses typically induce distinct clinical manifestations. Pigs infected with α-coronaviruses typically exhibit enteritis and watery diarrhea. These viruses are commonly referred to as porcine enteric coronaviruses (PEC) [14,15]. In contrast, PHEV causes encephalomyelitis, whereas PRCV causes respiratory disease [16,17]. Among the six porcine coronaviruses mentioned, PHEV and PRCV primarily infect individuals with occult infections, with or without mild clinical signs [18,19]. PECs are a significant cause of economic loss and the transmission of epidemics in farming. Since the last century, TGEV and PEDV have caused substantial economic losses in swine farming worldwide. PDCoV and SADS-CoV are emerging PECs that were discovered in 2014 (USA) and 2017 (China), respectively [20].

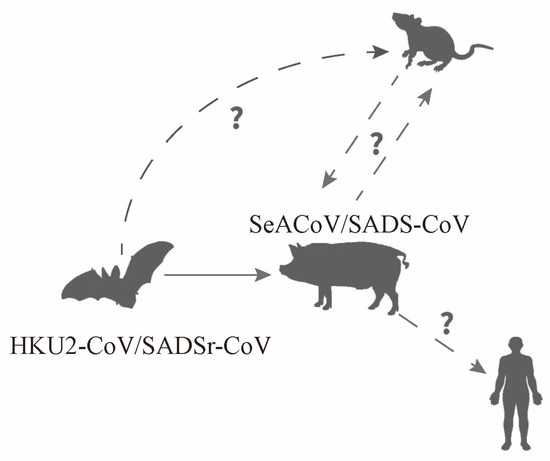

SADS-CoV, a novel porcine α-coronavirus, was first discovered in Guangdong Province, China, in 2017 [21]. SADS-CoV is closely related to bat coronavirus HKU2 [22], which was isolated by the University of Hong Kong in 2006. It originates from Rhinolophus sinicus and has a genome length of approximately 27.2 kilobases [23]. As of 2023, SADS-CoV has caused outbreaks in Guangdong and its neighboring provinces, including Fujian, Guangxi, and Jiangxi. Infected pigs exhibit clinical signs such as acute diarrhea and vomiting, along with high mortality rates in piglets. Although the scale of outbreaks caused by this virus has not yet reached pandemic levels, it is still endemic to specific regions. Studies have consistently shown that SADS-CoV, with its unique structure, is at risk of evolving into a zoonotic virus [24,25,26]. The study of SADS-CoV is critical for the surveillance and control of animal diseases, while also enhancing our understanding of coronaviruses by identifying their unique characteristics. This review will provide a summary and discussion of the research progress on SADS-CoV, focusing on its evolutionary features, cross-species transmissibility, zoonotic potential, key host factors, and prevention and treatment methods.

8. Discussion

SADS-CoV, an α-coronavirus with structural similarities to β-coronaviruses, has been extensively studied and found to exhibit several unique characteristics. One of these features is the ability to reduce immunogenicity by aligning the spike protein trimer conformation more tightly and making flexible structural adjustments [46]. Another characteristic of SADS-CoV is its reliance on complete autophagic [94,116,117] flux to increase viral copies. This suggests that there may be genome crossover between different species of the genus coronavirus [33,34], leading to evolutionary changes and the emergence of novel coronaviruses with distinct characteristics.

The temporal gaps and spatial uncertainty observed in epidemiological studies on the virus suggest a high degree of latency. Therefore, a high level of vigilance and continuous monitoring of swine farms, especially those previously affected by other swine coronaviruses, is imperative to minimize the economic impact of outbreaks and enhance our understanding of the evolutionary and epidemiological attributes of the virus. In addition, extensive cytophilicity and interspecies transmission of the virus [25] may have accelerated its evolution. Human-infecting coronaviruses typically have natural hosts and exist intermediate hosts before transmission to humans. Their evolutionary progression can be categorized into three stages: animal-only, zoonotic, and human-specific viruses. Recent outbreaks of SARS-CoV in 2003 [65,176,177] and MERS-CoV in 2012, which originated in bats, have demonstrated that the virus can only infect humans through the evolution and adaptation of intermediate hosts, such as civets and camels [178,179]. Predicting the possible mutation sites of SADS-CoV is crucial for understanding its potential evolution and assessing the risk of its transmission to humans.

Understanding viruses and the mechanisms of virus–host interactions, particularly with regard to SADS-CoV, is of great scientific and practical importance. While previous research has aided our understanding of the key factors of the virus’s hosts using integrated bioinformatics analysis, key host proteins that interact directly with the virus to completely block SADS-CoV invasion have not been identified [12,53]. This may be due to the use of immortalized cell lines in existing studies, which may have partial gene deletions or diverse mechanisms of cell invasion caused by the virus. Currently, established library screening methods typically use a limited number of infection pluralities to avoid false positive experimental results caused by the multiple knockdown of individual cells [180]. The potential key factors screened were all single genes. The functions and mechanisms of these single genes have been verified [130,139,141]; however, no studies have been conducted on the combined effects of multiple genes. Therefore, further research is needed to validate the results of library screening for co-interactions of multiple genes.

Vaccine research is a key initiative aimed at preventing viral infection. Despite ongoing efforts to screen for strains with attenuated activity, the traditional vaccine development process remains arduous and carries the risk of infection. mRNA vaccines have proven to be highly advantageous in addressing outbreaks caused by novel coronaviruses in the human population [181,182]. This vaccine’s characteristics can be summarized as “short development cycle, no risk of infection, simple production process, dual immunity mechanism, high immunogenicity, and no need for adjuvants” [183]. Vaccine development for SADS-CoV may have significant implications for future mRNA vaccine development during sudden outbreaks.

9. Conclusions

Coronaviruses persist as a formidable threat to human society, showcasing their capacity to traverse species boundaries and profoundly impact human health. While the prospect of direct human infection with porcine coronaviruses remains low, these pathogens exert an indirect influence by disrupting the agricultural sector, particularly the farming industry. Notably, the emergence of swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus (SADS-CoV) in recent years has triggered outbreaks in various provinces in southern China. Despite occurring in manageable outbreaks, the virus merits heightened attention due to its novel structural attributes and enhanced cellular invasion capabilities, as evidenced by an expanding body of research.

While prior studies have delved into the genomic, structural, evolutionary, and epidemiological facets of SADS-CoV, the virus’s elusive receptor remains an enigma. The absence of a known receptor, coupled with a commercially available vaccine, underscores the imperative for ongoing research efforts to unravel the intricacies of this viral threat. This review systematically consolidates the existing body of research on SADS-CoV since its initial report, offering comprehensive insights as a valuable reference for future investigations. As we confront the challenges posed by this emerging coronavirus, continued exploration and a deeper understanding are essential to pave the way for effective preventive and therapeutic interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L., Q.C. and Z.F.; software, W.H. and X.H.; validation, C.L. and W.H.; investigation, C.L., W.H. and X.H; resources, Q.C.; data curation, C.L. and Z.F.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L. and W.H.; writing—review and editing, X.H., Q.C. and Z.F.; visualization, C.L., W.H. and X.H; funding acquisition, Q.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University–Industry Cooperation Project of Fujian, 793 Province of China, grant number 2021N5003.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank our colleagues in the Qi Chen lab for their discussion and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lai, M.M.; Cavanagh, D. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 1997, 48, 1–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Wong, G.; Shi, W.; Liu, J.; Lai, A.C.K.; Zhou, J.; Liu, W.; Bi, Y.; Gao, G.F. Epidemiology, Genetic Recombination, and Pathogenesis of Coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S.R.; Navas-Martin, S. Coronavirus pathogenesis and the emerging pathogen severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2005, 69, 635–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocherhans, R.; Bridgen, A.; Ackermann, M.; Tobler, K. Completion of the porcine epidemic diarrhoea coronavirus (PEDV) genome sequence. Virus Genes 2001, 23, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langereis, M.A.; van Vliet, A.L.; Boot, W.; de Groot, R.J. Attachment of mouse hepatitis virus to O-acetylated sialic acid is mediated by hemagglutinin-esterase and not by the spike protein. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 8970–8974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Guo, D. Emerging coronaviruses: Genome structure, replication, and pathogenesis. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, S.A.; Brown, J.; Pedersen, B.S.; Quinlan, A.R.; Elde, N.C. Extensive recombination-driven coronavirus diversification expands the pool of potential pandemic pathogens. bioRxiv 2021. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Li, F.; Shi, Z.L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumtaz, M.; Hussain, N.; Baqar, Z.; Anwar, S.; Bilal, M. Deciphering the impact of novel coronavirus pandemic on agricultural sustainability, food security, and socio-economic sectors—A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 49410–49424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.Q.; Cai, R.J.; Chen, Y.Q.; Liang, P.S.; Chen, D.K.; Song, C.X. Outbreak of porcine epidemic diarrhea in suckling piglets, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlasova, A.N.; Marthaler, D.; Wang, Q.; Culhane, M.R.; Rossow, K.D.; Rovira, A.; Collins, J.; Saif, L.J. Distinct characteristics and complex evolution of PEDV strains, North America, May 2013–February 2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 1620–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Fan, H.; Lan, T.; Yang, X.L.; Shi, W.F.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.W.; Xie, Q.M.; Mani, S.; et al. Fatal swine acute diarrhoea syndrome caused by an HKU2-related coronavirus of bat origin. Nature 2018, 556, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malbec, R.; Kimpston-Burkgren, K.; Vandenkoornhuyse, E.; Olivier, C.; Souplet, V.; Audebert, C.; Carrillo-Ávila, J.A.; Baum, D.; Giménez-Lirola, L. Agrodiag PorCoV: A multiplex immunoassay for the differential diagnosis of porcine enteric coronaviruses. J. Immunol. Methods 2020, 483, 112808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, H.Y. Porcine enteric coronaviruses: An updated overview of the pathogenesis, prevalence, and diagnosis. Vet. Res. Commun. 2021, 45, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Luo, Y.; Liang, X.; Wang, X. A Review of Bioactive Compounds against Porcine Enteric Coronaviruses. Viruses 2022, 14, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Gao, F.; Lan, Y.; Guan, J.; Zhang, J.; Lu, H.; Zhao, K.; He, W. Porcine Hemagglutinating Encephalomyelitis Virus Triggers Neural Autophagy Independently of ULK1. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e0085121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keep, S.; Carr, B.V.; Lean, F.Z.X.; Fones, A.; Newman, J.; Dowgier, G.; Freimanis, G.; Vatzia, E.; Polo, N.; Everest, H.; et al. Porcine Respiratory Coronavirus as a Model for Acute Respiratory Coronavirus Disease. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 867707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesley, R.D.; Woods, R.D. Immunization of pregnant gilts with PRCV induces lactogenic immunity for protection of nursing piglets from challenge with TGEV. Vet. Microbiol. 1993, 38, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora-Díaz, J.C.; Temeeyasen, G.; Magtoto, R.; Rauh, R.; Nelson, W.; Carrillo-Ávila, J.A.; Zimmerman, J.; Piñeyro, P.; Giménez-Lirola, L. Infection and immune response to porcine hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus in grower pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 2021, 253, 108958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, K.; Hu, H.; Saif, L.J. Porcine deltacoronavirus infection: Etiology, cell culture for virus isolation and propagation, molecular epidemiology and pathogenesis. Virus Res. 2016, 226, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.; Mou, C.; Shi, K.; Chen, X.; Meng, X.; Bao, W.; Chen, Z. SADS-CoV nsp1 inhibits the IFN-β production by preventing TBK1 phosphorylation and inducing CBP degradation. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e29104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, S.K.; Woo, P.C.; Li, K.S.; Huang, Y.; Wang, M.; Lam, C.S.; Xu, H.; Guo, R.; Chan, K.H.; Zheng, B.J.; et al. Complete genome sequence of bat coronavirus HKU2 from Chinese horseshoe bats revealed a much smaller spike gene with a different evolutionary lineage from the rest of the genome. Virology 2007, 367, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Feng, T.; Shi, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Feng, S.; Chen, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Z.; et al. Identification and epitope mapping of swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus accessory protein NS7a via monoclonal antibodies. Virus Res. 2022, 313, 198742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Yang, Y.L.; Qin, Y.; Pan, D.; Yuan, L.X.; Huang, Y.W.; Wang, B. The origin and evolution of emerged swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus with zoonotic potential. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Geng, R.; Li, B.; Chen, J.; Zhao, K.; Zheng, X.S.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; et al. Broad Cell Tropism of SADS-CoV In Vitro Implies Its Potential Cross-Species Infection Risk. Virol. Sin. 2021, 36, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, C.E.; Yount, B.L.; Graham, R.L.; Leist, S.R.; Hou, Y.J.; Dinnon, K.H., 3rd; Sims, A.C.; Swanstrom, J.; Gully, K.; Scobey, T.D.; et al. Swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus replication in primary human cells reveals potential susceptibility to infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 26915–26925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, Q.; Xu, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, C.; Wen, Z.; Cao, Y. A New Bat-HKU2-like Coronavirus in Swine, China, 2017. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017, 23, 1607–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.N.; Liang, Y.F.; Weng, Z.J.; Quan, W.P.; Hu, C.; Peng, Y.Z.; Sun, Y.S.; Gao, Q.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, G.H.; et al. Porcine Enteric Alphacoronavirus Entry through Multiple Pathways (Caveolae, Clathrin, and Macropinocytosis) Requires Rab GTPases for Endosomal Transport. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0021023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, H.; Bi, Z.; Gu, J.; Gong, W.; Luo, S.; Zhang, F.; Song, D.; Ye, Y.; Tang, Y. Complete Genome Sequence of a Novel Swine Acute Diarrhea Syndrome Coronavirus, CH/FJWT/2018, Isolated in Fujian, China, in 2018. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2018, 7, e01259-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xing, J.; Xu, Z.Y.; Gao, H.; Xu, S.J.; Liu, J.; Zhu, D.H.; Guo, Y.F.; Yang, B.S.; Chen, X.N.; et al. Re-emergence of Severe Acute Diarrhea Syndrome Coronavirus (SADS-CoV) in Guangxi, China, 2021. J. Infect. 2022, 85, e130–e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Vlasova, A.N.; Kenney, S.P.; Saif, L.J. Emerging and re-emerging coronaviruses in pigs. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2019, 34, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.L.; Liang, Q.Z.; Xu, S.Y.; Mazing, E.; Xu, G.H.; Peng, L.; Qin, P.; Wang, B.; Huang, Y.W. Characterization of a novel bat-HKU2-like swine enteric alphacoronavirus (SeACoV) infection in cultured cells and development of a SeACoV infectious clone. Virology 2019, 536, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Tian, X.; Qin, P.; Wang, B.; Zhao, P.; Yang, Y.L.; Wang, L.; Wang, D.; Song, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. Discovery of a novel swine enteric alphacoronavirus (SeACoV) in southern China. Vet. Microbiol. 2017, 211, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Fang, B.; Liu, Y.; Cai, M.; Jun, J.; Ma, J.; Bu, D.; Wang, L.; Zhou, P.; Wang, H.; et al. Newly emerged porcine enteric alphacoronavirus in southern China: Identification, origin and evolutionary history analysis. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018, 62, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Su, S.; Bi, Y.; Wong, G.; Gao, G.F. Bat-Origin Coronaviruses Expand Their Host Range to Pigs. Trends Microbiol. 2018, 26, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, L.; Huang, L.; Lin, Y.; Qin, J.; Du, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Xue, C.; Cao, Y. Isolation and characterization of a highly pathogenic strain of Porcine enteric alphacoronavirus causing watery diarrhoea and high mortality in newborn piglets. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Zou, C.; Peng, P.; Wu, Y.; Wei, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gong, L.; Cao, Y.; Xue, C. Attenuation and characterization of porcine enteric alphacoronavirus strain GDS04 via serial cell passage. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 239, 108489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.L.; Yu, J.Q.; Huang, Y.W. Swine enteric alphacoronavirus (swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus): An update three years after its discovery. Virus Res. 2020, 285, 198024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.H.; Chuang, S.J.; Chen, C.C.; Cheng, S.C.; Cheng, K.W.; Lin, C.H.; Sun, C.Y.; Chou, C.Y. Structural and functional characterization of MERS coronavirus papain-like protease. J. Biomed. Sci. 2014, 21, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Shaw, N.; Yan, L.; Lou, Z.; Rao, Z. Structural view and substrate specificity of papain-like protease from avian infectious bronchitis virus. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 7160–7168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemm, T.; Ebert, G.; Calleja, D.J.; Allison, C.C.; Richardson, L.W.; Bernardini, J.P.; Lu, B.G.; Kuchel, N.W.; Grohmann, C.; Shibata, Y.; et al. Mechanism and inhibition of the papain-like protease, PLpro, of SARS-CoV-2. Embo J. 2020, 39, e106275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindner, H.A.; Fotouhi-Ardakani, N.; Lytvyn, V.; Lachance, P.; Sulea, T.; Ménard, R. The papain-like protease from the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus is a deubiquitinating enzyme. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 15199–15208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clementz, M.A.; Chen, Z.; Banach, B.S.; Wang, Y.; Sun, L.; Ratia, K.; Baez-Santos, Y.M.; Wang, J.; Takayama, J.; Ghosh, A.K.; et al. Deubiquitinating and interferon antagonism activities of coronavirus papain-like proteases. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 4619–4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Hu, W.; Fan, C. Structural and biochemical characterization of SADS-CoV papain-like protease 2. Protein Sci. 2020, 29, 1228–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, C.; Suo, X.; Duan, Y.; Li, X.; Shi, L.; Cao, L.; Kong, X.; Zheng, H.; Wang, Q. Comprehensive Subcellular Localization of Swine Acute Diarrhea Syndrome Coronavirus Proteins. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0077222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Wang, Y.; Perčulija, V.; Saeed, A.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Jan, S.S.; Li, Y.; Zhu, P.; Ouyang, S. Cryo-electron Microscopy Structure of the Swine Acute Diarrhea Syndrome Coronavirus Spike Glycoprotein Provides Insights into Evolution of Unique Coronavirus Spike Proteins. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e01301-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchdoerfer, R.N.; Wang, N.; Pallesen, J.; Wrapp, D.; Turner, H.L.; Cottrell, C.A.; Corbett, K.S.; Graham, B.S.; McLellan, J.S.; Ward, A.B. Stabilized coronavirus spikes are resistant to conformational changes induced by receptor recognition or proteolysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F. Structure, Function, and Evolution of Coronavirus Spike Proteins. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2016, 3, 237–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorici, M.A.; Veesler, D. Structural insights into coronavirus entry. Adv. Virus Res. 2019, 105, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, F.; Matsuyama, S. Cell entry mechanisms of coronaviruses. Uirusu 2009, 59, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- EA, J.A.; Jones, I.M. Membrane binding proteins of coronaviruses. Future Virol. 2019, 14, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.Q.; Liu, W.; Fan, X.H.; Vijaykrishna, D.; Tang, X.C.; Gao, F.; Li, L.F.; Li, G.J.; Zhang, J.X.; Yang, L.Q.; et al. Detection of a novel and highly divergent coronavirus from asian leopard cats and Chinese ferret badgers in Southern China. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 6920–6926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Qiao, S.; Guo, R.; Wang, X. Cryo-EM structures of HKU2 and SADS-CoV spike glycoproteins provide insights into coronavirus evolution. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Gui, M.; Wang, X.; Xiang, Y. Cryo-EM structure of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein in complex with its host cell receptor ACE2. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, J.C.; Zelus, B.D.; Holmes, K.V.; Weiss, S.R. The N-terminal domain of the murine coronavirus spike glycoprotein determines the CEACAM1 receptor specificity of the virus strain. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Shi, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, S.; Wang, D.; Tong, P.; Guo, D.; Fu, L.; Cui, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Structure of MERS-CoV spike receptor-binding domain complexed with human receptor DPP4. Cell Res. 2013, 23, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, G.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Qi, J.; Gao, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, Y.; Bao, J.; et al. Molecular basis of binding between novel human coronavirus MERS-CoV and its receptor CD26. Nature 2013, 500, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, W.; Farzan, M.; Harrison, S.C. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science 2005, 309, 1864–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, D.; Ou, X.; Li, P.; Peng, G.; Liu, Y.; Guo, R.; Mu, Z.; Li, F.; Holmes, K.; Qian, Z. Glycine 29 Is Critical for Conformational Changes of the Spike Glycoprotein of Mouse Hepatitis Virus A59 Triggered by either Receptor Binding or High pH. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01046-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Wan, Y.; Liu, C.; Yount, B.; Gully, K.; Yang, Y.; Auerbach, A.; Peng, G.; Baric, R.; Li, F. Structure of mouse coronavirus spike protein complexed with receptor reveals mechanism for viral entry. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Hou, Y.; Wang, Q. The enhanced replication of an S-intact PEDV during coinfection with an S1 NTD-del PEDV in piglets. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 228, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Rosen, O.; Wang, L.; Turner, H.L.; Stevens, L.J.; Corbett, K.S.; Bowman, C.A.; Pallesen, J.; Shi, W.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Structural Definition of a Neutralization-Sensitive Epitope on the MERS-CoV S1-NTD. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 3395–3405.e3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desingu, P.A.; Nagarajan, K.; Dhama, K. SARS-CoV-2 gained a novel spike protein S1-N-Terminal Domain (S1-NTD). Environ. Res. 2022, 211, 113047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, B.T.T.; Thao, P.T.P.; Hoa, N.T.; Thu, H.T.; Phuoc, M.H.; Le, T.H.; Van Quyen, D. Molecular analysis reveals a distinct subgenogroup of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in northern Vietnam in 2018–2019. Arch. Virol. 2022, 167, 2337–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husain, I.; Ahmad, R.; Siddiqui, S.; Chandra, A.; Misra, A.; Srivastava, A.; Ahamad, T.; Khan, M.F.; Siddiqi, Z.; Trivedi, A.; et al. Structural interactions of phytoconstituent(s) from cinnamon, bay leaf, oregano, and parsley with SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein: A comparative assessment for development of potential antiviral nutraceuticals. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, G.; Wang, Q.; Gao, G.F. Bat-to-human: Spike features determining ‘host jump’ of coronaviruses SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and beyond. Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walls, A.C.; Tortorici, M.A.; Frenz, B.; Snijder, J.; Li, W.; Rey, F.A.; DiMaio, F.; Bosch, B.J.; Veesler, D. Glycan shield and epitope masking of a coronavirus spike protein observed by cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016, 23, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, C.; Geng, Q.; Tai, W.; Du, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, F. Cryo-Electron Microscopy Structure of Porcine Deltacoronavirus Spike Protein in the Prefusion State. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e01556-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Nomura, N.; Muramoto, Y.; Ekimoto, T.; Uemura, T.; Liu, K.; Yui, M.; Kono, N.; Aoki, J.; Ikeguchi, M.; et al. Structure of SARS-CoV-2 membrane protein essential for virus assembly. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhuang, M.W.; Han, L.; Zhang, J.; Nan, M.L.; Zhan, P.; Kang, D.; Liu, X.; Gao, C.; Wang, P.H. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) membrane (M) protein inhibits type I and III interferon production by targeting RIG-I/MDA-5 signaling. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, K.A.; Dutta, M.; Kern, D.M.; Kotecha, A.; Voth, G.A.; Brohawn, S.G. Structure of SARS-CoV-2 M protein in lipid nanodiscs. Elife 2022, 11, e81702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, L.; Hurst-Hess, K.R.; Koetzner, C.A.; Masters, P.S. Analyses of Coronavirus Assembly Interactions with Interspecies Membrane and Nucleocapsid Protein Chimeras. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 4357–4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, A.; Pak, A.J.; He, P.; Monje-Galvan, V.; Casalino, L.; Gaieb, Z.; Dommer, A.C.; Amaro, R.E.; Voth, G.A. A Multiscale Coarse-grained Model of the SARS-CoV-2 Virion. bioRxiv 2020. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoeman, D.; Fielding, B.C. Coronavirus envelope protein: Current knowledge. Virol. J. 2019, 16, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeDiego, M.L.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; Jiménez-Guardeño, J.M.; Regla-Nava, J.A.; Alvarez, E.; Oliveros, J.C.; Zhao, J.; Fett, C.; Perlman, S.; Enjuanes, L. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus envelope protein regulates cell stress response and apoptosis. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Yang, R.; Lee, I.; Zhang, W.; Sun, J.; Wang, W.; Meng, X. Characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 E Protein: Sequence, Structure, Viroporin, and Inhibitors. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 1114–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.; Hogue, B.G. Role of the coronavirus E viroporin protein transmembrane domain in virus assembly. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 3597–3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruch, T.R.; Machamer, C.E. The coronavirus E protein: Assembly and beyond. Viruses 2012, 4, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.X.; Yuan, Q.; Liao, Y. Coronavirus envelope protein: A small membrane protein with multiple functions. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 2043–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, R.; van Zyl, M.; Fielding, B.C. The coronavirus nucleocapsid is a multifunctional protein. Viruses 2014, 6, 2991–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Du, N.; Lei, Y.; Dorje, S.; Qi, J.; Luo, T.; Gao, G.F.; Song, H. Structures of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid and their perspectives for drug design. EMBO J. 2020, 39, e105938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timani, K.A.; Liao, Q.; Ye, L.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Ye, L.; Yang, X.; Lingbao, K.; Gao, J.; et al. Nuclear/nucleolar localization properties of C-terminal nucleocapsid protein of SARS coronavirus. Virus Res. 2005, 114, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Sun, Y.; Xu, J.; Tang, X.; Zhou, L.; Li, Q.; Lan, T.; Ma, J. Swine Acute Diarrhea Syndrome Coronavirus Nucleocapsid Protein Antagonizes Interferon-β Production via Blocking the Interaction between TRAF3 and TBK1. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 573078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liang, Q.Z.; Lu, W.; Yang, Y.L.; Chen, R.; Huang, Y.W.; Wang, B. A Comparative Analysis of Coronavirus Nucleocapsid (N) Proteins Reveals the SADS-CoV N Protein Antagonizes IFN-β Production by Inducing Ubiquitination of RIG-I. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 688758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Cheng, J.; Luo, Y.; Yan, X.L.; Wu, Z.X.; He, L.L.; Tan, Y.R.; Zhou, Z.H.; Li, Q.N.; Zhou, L.; et al. Attenuation of a virulent swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus strain via cell culture passage. Virology 2019, 538, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Sun, Y.; Lan, T.; Wu, R.; Chen, J.; Wu, Z.; Xie, Q.; Zhang, X.; Ma, J. Retrospective detection and phylogenetic analysis of swine acute diarrhoea syndrome coronavirus in pigs in southern China. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, Q.N.; Su, J.N.; Chen, G.H.; Wu, Z.X.; Luo, Y.; Wu, R.T.; Sun, Y.; Lan, T.; Ma, J.Y. The re-emerging of SADS-CoV infection in pig herds in Southern China. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 2180–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Cheng, Y.; Ling, R.; Dai, Y.; Huang, B.; Huang, W.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, Y. Antibody-dependent enhancement of coronavirus. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 100, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloutier, M.; Nandi, M.; Ihsan, A.U.; Chamard, H.A.; Ilangumaran, S.; Ramanathan, S. ADE and hyperinflammation in SARS-CoV2 infection- comparison with dengue hemorrhagic fever and feline infectious peritonitis. Cytokine 2020, 136, 155256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, J.K.; Jaimes, J.A.; Whittaker, G.R. Molecular diversity of coronavirus host cell entry receptors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2021, 45, fuaa057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, X.Q.; Qin, P.; Yang, Y.L.; Liao, M.; Liang, Q.Z.; Zhao, Z.; Shi, F.S.; Wang, B.; Huang, Y.W. First evidence that an emerging mammalian alphacoronavirus is able to infect an avian species. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, e2006–e2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.L.; Qin, P.; Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Xu, G.H.; Peng, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhu, S.J.; Huang, Y.W. Broad Cross-Species Infection of Cultured Cells by Bat HKU2-Related Swine Acute Diarrhea Syndrome Coronavirus and Identification of Its Replication in Murine Dendritic Cells In Vivo Highlight Its Potential for Diverse Interspecies Transmission. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01448-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

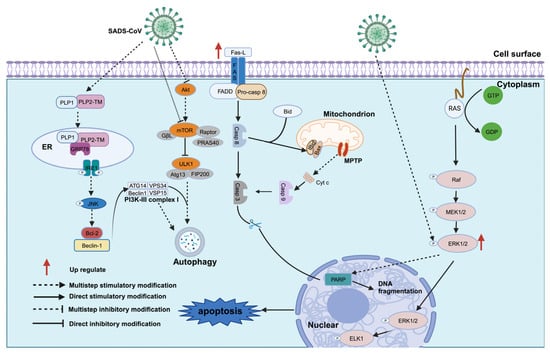

- Zhang, J.; Han, Y.; Shi, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Ji, Z.; et al. Swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus-induced apoptosis is caspase- and cyclophilin D- dependent. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.M.; Burrough, E. The Effects of Swine Coronaviruses on ER Stress, Autophagy, Apoptosis, and Alterations in Cell Morphology. Pathogens 2022, 11, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y. The Roles of Apoptosis in Swine Response to Viral Infection and Pathogenesis of Swine Enteropathogenic Coronaviruses. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 572425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everett, H.; McFadden, G. Apoptosis: An innate immune response to virus infection. Trends Microbiol. 1999, 7, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.M.; Kleiboeker, S.B. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus induces apoptosis through a mitochondria-mediated pathway. Virology 2007, 365, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Xu, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, K.; Chen, G.; Yu, G.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Tong, D. Transmissible gastroenteritis virus infection induces apoptosis through FasL- and mitochondria-mediated pathways. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 158, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Martindale, J.L.; Holbrook, N.J. Requirement for ERK activation in cisplatin-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 39435–39443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornberry, N.A.; Lazebnik, Y. Caspases: Enemies within. Science 1998, 281, 1312–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.M. Signal transduction mediated by Bid, a pro-death Bcl-2 family proteins, connects the death receptor and mitochondria apoptosis pathways. Cell Res. 2000, 10, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halestrap, A.P.; McStay, G.P.; Clarke, S.J. The permeability transition pore complex: Another view. Biochimie 2002, 84, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.C.; Zong, W.X.; Cheng, E.H.; Lindsten, T.; Panoutsakopoulou, V.; Ross, A.J.; Roth, K.A.; MacGregor, G.R.; Thompson, C.B.; Korsmeyer, S.J. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: A requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science 2001, 292, 727–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, D.H.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, H.S.; Chung, H.H.; Song, Y.S. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore as a selective target for anti-cancer therapy. Front. Oncol. 2013, 3, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, M.; Sakamoto, N.; Enomoto, N.; Tanabe, Y.; Kanazawa, N.; Koyama, T.; Kurosaki, M.; Maekawa, S.; Yamashiro, T.; Chen, C.H.; et al. Specific inhibition of hepatitis C virus replication by cyclosporin A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 313, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Wilde, A.H.; Li, Y.; van der Meer, Y.; Vuagniaux, G.; Lysek, R.; Fang, Y.; Snijder, E.J.; van Hemert, M.J. Cyclophilin inhibitors block arterivirus replication by interfering with viral RNA synthesis. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 1454–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, P.P.; Blenis, J. ERK and p38 MAPK-activated protein kinases: A family of protein kinases with diverse biological functions. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2004, 68, 320–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Shi, H.; Feng, S.; Feng, T.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Han, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus replication is reduced by inhibition of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway. Virology 2022, 565, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubiec, A.; Jupin, I. Regulation of positive-strand RNA virus replication: The emerging role of phosphorylation. Virus Res. 2007, 129, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shi, H.; Zhou, L.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Ji, Z.; et al. Epitope mapping and cellular localization of swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus nucleocapsid protein using a novel monoclonal antibody. Virus Res. 2019, 273, 197752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Lee, C. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus replication is suppressed by inhibition of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway. Virus Res. 2010, 152, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, C. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation is required for porcine epidemic diarrhea virus replication. Virology 2015, 484, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.; Vanhoutte, P.; Pages, C.; Caboche, J.; Laroche, S. The MAPK/ERK cascade targets both Elk-1 and cAMP response element-binding protein to control long-term potentiation-dependent gene expression in the dentate gyrus in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 4563–4572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, N.; Komatsu, M. Autophagy: Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell 2011, 147, 728–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottam, E.M.; Maier, H.J.; Manifava, M.; Vaux, L.C.; Chandra-Schoenfelder, P.; Gerner, W.; Britton, P.; Ktistakis, N.T.; Wileman, T. Coronavirus nsp6 proteins generate autophagosomes from the endoplasmic reticulum via an omegasome intermediate. Autophagy 2011, 7, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prentice, E.; Jerome, W.G.; Yoshimori, T.; Mizushima, N.; Denison, M.R. Coronavirus replication complex formation utilizes components of cellular autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 10136–10141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Tan, X.; Guo, H.; Zeng, W.; Yan, G.; Memon, A.M.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Induces Autophagy to Benefit Its Replication. Viruses 2017, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, O.; Xia, Y.; Xu, Q.; Li, H.; Xue, C.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, H. Swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus induces autophagy to promote its replication via the Akt/mTOR pathway. iScience 2022, 25, 105394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, D.; Zhou, L.; Shi, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, D.; Feng, T.; Zeng, M.; Chen, J.; et al. Autophagy is induced by swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus through the cellular IRE1-JNK-Beclin 1 signaling pathway after an interaction of viral membrane-associated papain-like protease and GRP78. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Peng, O.; Sun, R.; Xu, Q.; Hu, F.; Zhao, Y.; Xue, C.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, H. Transcriptional Landscape of Vero E6 Cells during Early Swine Acute Diarrhea Syndrome Coronavirus Infection. Viruses 2021, 13, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, G.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Ji, M.; Chen, Y.; Shi, Y.; Bi, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, H. ORF3a of the COVID-19 virus SARS-CoV-2 blocks HOPS complex-mediated assembly of the SNARE complex required for autolysosome formation. Dev. Cell 2021, 56, 427–442.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Li, Y.E.; Yuan, Y.; Du, X.; Wang, Y.; Dong, X.; Yang, H.; Qi, S. TMEM41B and VMP1 are phospholipid scramblases. Autophagy 2021, 17, 2048–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamers, M.M.; Beumer, J.; van der Vaart, J.; Knoops, K.; Puschhof, J.; Breugem, T.I.; Ravelli, R.B.G.; Paul van Schayck, J.; Mykytyn, A.Z.; Duimel, H.Q.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 productively infects human gut enterocytes. Science 2020, 369, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scialo, F.; Daniele, A.; Amato, F.; Pastore, L.; Matera, M.G.; Cazzola, M.; Castaldo, G.; Bianco, A. ACE2: The Major Cell Entry Receptor for SARS-CoV-2. Lung 2020, 198, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, L.; Lian, X.; Xie, Y.; Li, S.; Xin, S.; Cao, P.; Lu, J. The MERS-CoV Receptor DPP4 as a Candidate Binding Target of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike. iScience 2020, 23, 101400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Prasoon, P.; Kumari, C.; Pareek, V.; Faiq, M.A.; Narayan, R.K.; Kulandhasamy, M.; Kant, K. SARS-CoV-2-specific virulence factors in COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Hou, Y.; Yang, D.; Wen, L.; Shuai, H.; Yoon, C.; Shi, J.; Chai, Y.; Yuen, T.T.; Hu, B.; et al. Coronaviruses exploit a host cysteine-aspartic protease for replication. Nature 2022, 609, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Receptor recognition mechanisms of coronaviruses: A decade of structural studies. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 1954–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Alfajaro, M.M.; DeWeirdt, P.C.; Hanna, R.E.; Lu-Culligan, W.J.; Cai, W.L.; Strine, M.S.; Zhang, S.M.; Graziano, V.R.; Schmitz, C.O.; et al. Genome-wide CRISPR Screens Reveal Host Factors Critical for SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Cell 2021, 184, 76–91.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Jin, Q.; Xiao, W.; Fang, P.; Lai, L.; Xiao, S.; Wang, K.; Fang, L. Genome-Wide CRISPR/Cas9 Screen Reveals a Role for SLC35A1 in the Adsorption of Porcine Deltacoronavirus. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0162622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Zu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, F.; Jin, X.; Hu, H. Porcine Deltacoronavirus Utilizes Sialic Acid as an Attachment Receptor and Trypsin Can Influence the Binding Activity. Viruses 2021, 13, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Hulswit, R.J.G.; Widjaja, I.; Raj, V.S.; McBride, R.; Peng, W.; Widagdo, W.; Tortorici, M.A.; van Dieren, B.; Lang, Y.; et al. Identification of sialic acid-binding function for the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E8508–E8517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Yoon, J.; Park, J.E. Furin cleavage is required for swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus spike protein-mediated cell—Cell fusion. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2022, 11, 2176–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Shang, W.; Shi, Z.; Xiao, G.; Zhang, L. Comprehensive interactome analysis of the spike protein of swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus. Biosaf. Health 2021, 3, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.T.; Chien, S.C.; Chen, I.Y.; Lai, C.T.; Tsay, Y.G.; Chang, S.C.; Chang, M.F. Surface vimentin is critical for the cell entry of SARS-CoV. J. Biomed. Sci. 2016, 23, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.Y.; Yang, Y.L.; Tang, Y.X.; Qin, P.; Wang, G.; Xie, J.Y.; Chen, S.X.; Ding, C.; Huang, Y.W.; Zhu, S.J. Bile acids promote the caveolae-associated entry of swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus in porcine intestinal enteroids. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledford, J.G.; Kovarova, M.; Koller, B.H. Impaired host defense in mice lacking ONZIN. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 5132–5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.M.; Kerr, M.S.; Slaven, J.E. Plac8-dependent and inducible NO synthase-dependent mechanisms clear Chlamydia muridarum infections from the genital tract. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 1896–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, L.V.; Meganck, R.M.; Araba, K.C.; Yount, B.L.; Shaffer, K.M.; Hou, Y.J.; Munt, J.E.; Adams, L.E.; Wykoff, J.A.; Morowitz, J.M.; et al. Genomewide CRISPR knockout screen identified PLAC8 as an essential factor for SADS-CoVs infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2118126119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axe, E.L.; Walker, S.A.; Manifava, M.; Chandra, P.; Roderick, H.L.; Habermann, A.; Griffiths, G.; Ktistakis, N.T. Autophagosome formation from membrane compartments enriched in phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and dynamically connected to the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 182, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Tan, C.W.; Xie, S.Z.; Chen, Y.; Yao, Y.L.; Zhao, K.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, M.Q.; Yang, X.L.; et al. Identification of ZDHHC17 as a Potential Drug Target for Swine Acute Diarrhea Syndrome Coronavirus Infection. mBio 2021, 12, e0234221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Mou, C.; Yang, X.; Lin, J.; Yang, Q. Mitophagy in TGEV infection counteracts oxidative stress and apoptosis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 27122–27141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Yuan, C.; Suo, X.; Cao, L.; Kong, X.; Li, X.; Zheng, H.; Wang, Q. TET2 is required for Type I IFN-mediated inhibition of bat-origin swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 3251–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliman, M.; Cho, E.H.; Park, J.G.; Kim, J.Y.; Alfajaro, M.M.; Baek, Y.B.; Kim, D.S.; Kang, M.I.; Park, S.I.; Cho, K.O. Rotavirus-Induced Early Activation of the RhoA/ROCK/MLC Signaling Pathway Mediates the Disruption of Tight Junctions in Polarized MDCK Cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharif, M.; Baek, Y.B.; Naveed, A.; Stalin, N.; Kang, M.I.; Park, S.I.; Soliman, M.; Cho, K.O. Porcine Sapovirus-Induced Tight Junction Dissociation via Activation of RhoA/ROCK/MLC Signaling Pathway. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e00051-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Z.; Tang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, L.; Han, Y. The association of ribosomal protein L18 with Newcastle disease virus matrix protein enhances viral translation and replication. Avian Pathol. 2022, 51, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y. Ribosomal protein L18 is an essential factor that promote rice stripe virus accumulation in small brown planthopper. Virus Res. 2018, 247, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Duan, X.; Fu, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Cao, H.; Zheng, S.J. The association of ribosomal protein L18 (RPL18) with infectious bursal disease virus viral protein VP3 enhances viral replication. Virus Res. 2018, 245, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Moro, A.; Tebaldi, T.; Cornella, N.; Gasperini, L.; Lunelli, L.; Quattrone, A.; Viero, G.; Macchi, P. Identification and dynamic changes of RNAs isolated from RALY-containing ribonucleoprotein complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 6775–6792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Cao, Z.; Ji, C.; Zhou, L.; Yan, X.; Sun, Y.; Ma, J. Analysis of Interaction Network Between Host Protein and M Protein of Swine Acute Diarrhea Syndrome Coronavirus. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 858460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Lu, J.; Wang, N.; He, W.T.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, W.; Su, S. Development of a TaqMan-probe-based multiplex real-time PCR for the simultaneous detection of emerging and reemerging swine coronaviruses. Virulence 2020, 11, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Zeng, F.; Cong, F.; Huang, B.; Huang, R.; Ma, J.; Guo, P. Development of a SYBR green-based real-time RT-PCR assay for rapid detection of the emerging swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus. J. Virol. Methods 2019, 265, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Shi, K.; Long, F.; Zhao, K.; Feng, S.; Yin, Y.; Xiong, C.; Qu, S.; Lu, W.; Li, Z. A Quadruplex qRT-PCR for Differential Detection of Four Porcine Enteric Coronaviruses. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.H.; Rawal, G.; Aljets, E.; Yim-Im, W.; Yang, Y.L.; Huang, Y.W.; Krueger, K.; Gauger, P.; Main, R.; Zhang, J. Development and Clinical Applications of a 5-Plex Real-Time RT-PCR for Swine Enteric Coronaviruses. Viruses 2022, 14, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Cong, F.; Zeng, F.; Lian, Y.; Liu, X.; Luo, M.; Guo, P.; Ma, J. Development of a real time reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification method (RT-LAMP) for detection of a novel swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus (SADS-CoV). J. Virol. Methods 2018, 260, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Chen, Y.; Fang, X.; Liu, Y.; Du, M.; Lu, X.; Li, Q.; Sun, Y.; Ma, J.; Lan, T. Microfluidic-RT-LAMP chip for the point-of-care detection of emerging and re-emerging enteric coronaviruses in swine. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1125, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tao, D.; Chen, X.; Shen, L.; Zhu, L.; Xu, B.; Liu, H.; Zhao, S.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; et al. Detection of Four Porcine Enteric Coronaviruses Using CRISPR-Cas12a Combined with Multiplex Reverse Transcriptase Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Assay. Viruses 2022, 14, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Jiang, T.; Zheng, S.; Huang, M.; Xue, C.; Cao, Y.; Xu, Z. Development of an indirect ELISA for detecting swine acute diarrhoea syndrome coronavirus IgG antibodies based on a recombinant spike protein. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, 2065–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, H.; Bi, Z.; Song, D.; Zhang, F.; Lei, D.; Luo, S.; Li, Z.; Gong, W.; Huang, D.; et al. Significant inhibition of re-emerged and emerging swine enteric coronavirus in vitro using the multiple shRNA expression vector. Antivir. Res. 2019, 166, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulloor, N.K.; Nair, S.; McCaffrey, K.; Kostic, A.D.; Bist, P.; Weaver, J.D.; Riley, A.M.; Tyagi, R.; Uchil, P.D.; York, J.D.; et al. Human genome-wide RNAi screen identifies an essential role for inositol pyrophosphates in Type-I interferon response. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1003981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; You, Y.; Wang, S.; Jiang, L.; Tian, L.; Zhu, S.; An, X.; Song, L.; Tong, Y.; Fan, H. Antiviral Drugs Screening for Swine Acute Diarrhea Syndrome Coronavirus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.S.W.; Yap, T.; Martyres, R.; Kern, J.S.; Varigos, G.; Scardamaglia, L. The association of mycophenolate mofetil and human herpes virus infection. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2020, 31, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, A.; Prejs, M.; Cholewinski, G.; Dzierzbicka, K. New Analogues of Mycophenolic Acid. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 734–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagno, V.; Medaglia, C.; Cerny, A.; Cerny, T.; Zwygart, A.C.; Cerny, E.; Tapparel, C. Methylene Blue has a potent antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 and H1N1 influenza virus in the absence of UV-activation in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabholkar, N.; Gorantla, S.; Dubey, S.K.; Alexander, A.; Taliyan, R.; Singhvi, G. Repurposing methylene blue in the management of COVID-19: Mechanistic aspects and clinical investigations. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 142, 112023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.J.; Kim, C.; Cho, S. Gemcitabine and Nucleos(t)ide Synthesis Inhibitors Are Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Drugs that Activate Innate Immunity. Viruses 2018, 10, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, A.L. Natural products in drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2008, 13, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Chen, L.J.; Huang, T.; Ying, J.Q.; Li, J. The pharmacology, toxicology and therapeutic potential of anthraquinone derivative emodin. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2020, 18, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Huang, M.; Xia, Y.; Peng, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, S.; Wang, X.; Xue, C.; Cao, Y. Emodin from Aloe Inhibits Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus via Toll-Like Receptor 3 Activation. Viruses 2021, 13, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wang, X.; Hu, H.; Xia, Y.; Diao, X.; Qiu, W.; Xue, C.; Cao, Y.; Xu, Z. Emodin from Aloe inhibits Swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus in cell culture. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 978453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Li, J.; Yang, Q.; Wang, J.; Su, T.; Zhou, S. Gossypol has anti-cancer effects by dual-targeting MDM2 and VEGF in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2017, 19, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagunduz, O.; Karaca, B.; Atmaca, H.; Uzunoglu, S.; Karabulut, B.; Sanli, U.A.; Haydaroglu, A.; Uslu, R. Radiosensitization of hormone-refractory prostate cancer cells by gossypol treatment. J. BUON 2010, 15, 763–767. [Google Scholar]

- Mahase, E. COVID-19: Molnupiravir reduces risk of hospital admission or death by 50% in patients at risk, MSD reports. BMJ 2021, 375, n2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, W.; Wen, Z.; Wang, C.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Ding, T.; Shuai, L.; Zhong, G.; et al. Gossypol Broadly Inhibits Coronaviruses by Targeting RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerases. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2203499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.C.; Blanc, H.; Surdel, M.C.; Vignuzzi, M.; Denison, M.R. Coronaviruses lacking exoribonuclease activity are susceptible to lethal mutagenesis: Evidence for proofreading and potential therapeutics. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, Y.A. Properties of Coronavirus and SARS-CoV-2. Malays. J. Pathol. 2020, 42, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- To, K.K.; Sridhar, S.; Chiu, K.H.; Hung, D.L.; Li, X.; Hung, I.F.; Tam, A.R.; Chung, T.W.; Chan, J.F.; Zhang, A.J.; et al. Lessons learned 1 year after SARS-CoV-2 emergence leading to COVID-19 pandemic. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 507–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, E.; van Doremalen, N.; Falzarano, D.; Munster, V.J. SARS and MERS: Recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer Zu Natrup, C.; Schünemann, L.M.; Saletti, G.; Clever, S.; Herder, V.; Joseph, S.; Rodriguez, M.; Wernery, U.; Sutter, G.; Volz, A. MERS-CoV-Specific T-Cell Responses in Camels after Single MVA-MERS-S Vaccination. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 1236–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manghwar, H.; Lindsey, K.; Zhang, X.; Jin, S. CRISPR/Cas System: Recent Advances and Future Prospects for Genome Editing. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 1102–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, R.R.; Painter, M.M.; Apostolidis, S.A.; Mathew, D.; Meng, W.; Rosenfeld, A.M.; Lundgreen, K.A.; Reynaldi, A.; Khoury, D.S.; Pattekar, A.; et al. mRNA vaccines induce durable immune memory to SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern. Science 2021, 374, abm0829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheaffer, S.M.; Lee, D.; Whitener, B.; Ying, B.; Wu, K.; Liang, C.Y.; Jani, H.; Martin, P.; Amato, N.J.; Avena, L.E.; et al. Bivalent SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines increase breadth of neutralization and protect against the BA.5 Omicron variant in mice. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbeke, R.; Lentacker, I.; De Smedt, S.C.; Dewitte, H. The dawn of mRNA vaccines: The COVID-19 case. J. Control. Release 2021, 333, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).