Abstract

In this study, the effects of pediocin (PP) on intestinal barrier function, renal injury, and immune regulation were evaluated in Salmonella pullorum-infected chickens. Forty-five 7-day-old specific-pathogen-free (SPF) chickens were randomly assigned to three groups: control (CON), S. pullorum infection (SP), and S. pullorum infection + PP treatment (SPA). The results showed that S. pullorum infection significantly elevated (p < 0.05) the renal (CREA, UREA), hepatic (ALT, AST), immunological (IgG, IgM), and inflammatory (TNF-α, IL-6, SAA, CRP) parameters, as well as the expression of trefoil factor 3, Toll-like receptor 2, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. In contrast, the jejunal villus height and the villus-to-crypt ratio, and the expression of intestinal tight junction proteins (occludin, claudin-1, and Zonula occludens-1), mucin-2, and transforming growth factor-β1 were significantly decreased in both the SP and SPA groups. In the SP group, the parameter alterations observed at 6 DPI compared to the CON group persisted until 12 DPI. In contrast, in the SPA group, these parameters returned to levels comparable to those of the CON group after 6 days of PP treatment. Moreover, S. pullorum infection markedly reduced the α-diversity of the gut microbiota, and this reduction could be partially restored following PP treatment. At the phylum level, S. pullorum infection significantly reduced the relative abundances of Proteobacteria and Verrucomicrobia. PP treatment increased the abundances of Firmicutes and Actinobacteria, while also restoring the abundances of Proteobacteria and Verrucomicrobia to some extent. At the genus level, PP treatment significantly increased the abundance of Faecalibacterium and Lactobacillus. Additionally, Faecalibacterium and Butyricicoccus were significantly more abundant in the SPA group. Thus, PP could alleviate S. pullorum infection induced intestinal barrier damage, reduce immune stress responses, and exert a protective effect by modulating the composition of the intestinal microbiota of chickens.

1. Introduction

Salmonella, a common foodborne pathogen, poses a direct threat to animal health, causes substantial economic losses, and is a potential risk to human food safety [1]. Salmonella Pullorum is primarily parasitic in poultry hosts and can cause pullorum disease, a septicemic condition with an extremely high mortality rate in chicks and turkey poults. Transmission mainly occurs vertically (through eggs) but can also spread horizontally within poultry environments. In laying hens infected with S. pullorum, the most notable effects include decreased egg production, reduced egg weight, and poorer eggshell quality (such as thinner shells and higher breakage rates) [2,3], leading to economic losses in poultry farming. Therefore, effective health management and disease control are paramount in poultry farming. Recent epidemiological studies in China have confirmed S. pullorum as the most prevalent serotype in large-scale poultry farms [4,5]. Antibiotics are widely used in livestock farming to shorten disease duration and limit pathogen transmission [6]. However, this strategy has several drawbacks. Prolonged antibiotic use not only promotes the development of antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella and other enteric bacteria but also disrupts the composition of the gut host microbiota, leading to long-term adverse effects on animal health [7,8,9]. The European Union prohibited antibiotic use as growth promoters in 2006, and China introduced a similar ban on 1 July 2020. Since the prohibition, the treatment of intestinal diseases poses a major challenge in the poultry industry. Identifying alternative therapeutic approaches has become a central focus in current research to overcome these challenges. Among potential alternatives, bacteriocins such as nisin [10], which are produced by Lactococcus lactis, have demonstrated efficacy in inhibiting the growth of Salmonella. Nevertheless, their mechanisms of action and practical applications in the prevention and control of Salmonella infections remain insufficiently studied. Therefore, further investigation and development of novel antimicrobial agents, particularly bacteriocin-based alternatives, are important in mitigating the threat of Salmonella, reducing antibiotic dependence, and safeguarding both animal and human health.

Bacteriocins are ribosomally synthesized small peptides or proteins that exhibit potent antimicrobial activity, low host cytotoxicity, and a minimal likelihood of inducing drug resistance. These natural and safe bio-antimicrobial agents have been widely used in the fields of medicine [11], food processing [12], and animal husbandry [13]. Bacteriocins modulate the intestinal microbiota by inhibiting pathogenic bacteria while promoting the proliferation of beneficial bacteria, thereby maintaining intestinal health, enhancing immune responses, and alleviating physiological stress [14,15]. Mechanistically, most bacteriocins inactivate target cells by disrupting cell membranes and forming pores [16]. The bacteriocin pediocin from Pediococcus acidilactici is broad-spectrum and thermally stable [17] with proven efficacy in poultry. In broilers, dietary pediocin A alleviates Clostridium perfringens-induced growth impairment and tends to lower ADG (average daily gain) loss [18]. In chickens, supplementation of Pediococcus acidilactici (PA) enhances early production performance and eggshell quality [19]. Additionally, Pediococcus pentosaceus DYNDL69M8, which contains a pediocin-like operon, has been shown to increase beneficial gut bacteria and raise acetic acid concentration in mice, as demonstrated by Cui et al. [20]. However, bacteriocins, including nisin and pediocin, their precise mechanism of action on intestinal barrier function in vitro has not yet been completely elucidated.

Previously, an engineered strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae producing pediocin was successfully constructed. This strain exhibited excellent antibacterial properties in vitro and had a particularly strong antagonistic effect against Salmonella. However, it remains unclear as to whether bacteriocins can enhance gut health in a Salmonella-challenge model of chickens. Therefore, the efficacy of Pediococcus pentosaceus-derived bacteriocins in controlling Salmonella infections in chickens and their effects on intestinal morphology, immune responses, and cytokine mRNA expression were evaluated in this study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Bacteriocins

PP, a bacteriocin which was originally identified from a Pediococcus pentosaceus strain in our previous study, was heterologously expressed and tested for in vitro bacterial inhibition, and was found to be the most effective against Salmonella. S. cerevisiae strain YTK12 was preserved in yeast extract–peptone–dextrose (YPD; Solarbio, Beijing, China) medium containing 10% glycerol (Solarbio, Beijing, China) in an ultralow-temperature refrigerator at −80 °C. Prior to the experiment, YTK12 was inoculated in YPD liquid medium and incubated aseptically at 30 °C for 20 h. The cultures were then incubated at −80 °C in an ultralow-temperature refrigerator. Subsequently, the culture was transferred to a 5 L fermenter, and fermentation was continued for 2 days. The fermentation broth was centrifuged at 2000× g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm sterile filter to remove organisms, and the filtrate was stored in a 4 °C refrigerator for backup. The filter-sterilized supernatant, referred to as the crude pediocin PP preparation, was used directly for all subsequent assays and animal administration.

The antimicrobial activity of the crude pediocin PP preparation was determined against Salmonella spp. using the agar well diffusion method. Briefly, an overnight culture of the indicator strain was diluted and spread-plated onto Mueller–Hinton agar plates to achieve a final concentration of approximately 3 × 107 CFU per plate. Sterile Oxford cups (Beijing Pro PBS Biotechnology Co., Ltd., (Beijing, China)) (6 mm diameter) were placed on the seeded agar. Subsequently, 200 μL of the crude super-natant preparation was pipetted into each cup. The plates were kept at 4 °C for 4 h to allow pre-diffusion, then incubated at 37 °C for 12 h. The diameter of the resulting in-hibition zones was measured. The preparation used in this study produced a mean inhi-bition zone of 25.6 mm against the target Salmonella strain under these conditions. For quantification, the activity titer was defined in Arbitrary Units per milliliter (AU/mL), where 1 AU is defined as the amount of bacteriocin that generates a 1 mm inhibition zone diameter in this assay system. The preparation used in the animal trial had a titer of 1.28 × 102 AU/mL.

2.2. Culture and Handling of Salmonella pullorum

S. pullorum (CVCC 1800) was obtained from the Microbiological Conservation Center, Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences. The experimental procedure was as follows: Salmonella C1800 was first cultured under aerobic conditions by inoculation into Luria–Bertani (LB) agar medium and incubated at 37 °C while shaking at 200 rpm for 12 h. The culture was transferred to LB liquid medium and incubated for an additional 18 h under the stated conditions. From days 10 to 16 of the experiment, chickens in the challenge group were orally administered a suspension of actively growing Salmonella C1800 (1 × 107 colony-forming units [CFU]/mL, 1 mL per chick), whereas control chicks received an equal volume of sterilized LB broth (Qingdao Haibo Biology, Qingdao, China).

2.3. Animal Experiments

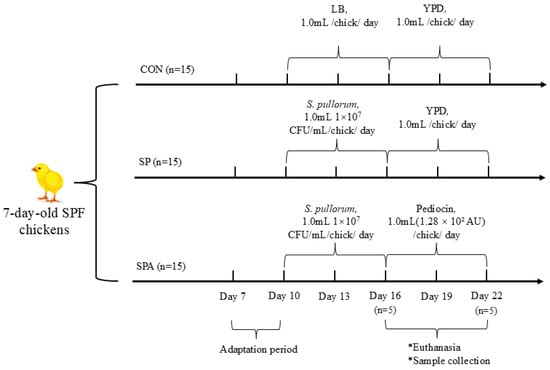

A total of 45 seven-day-old specific-pathogen-free (SPF) chickens with similar initial body weights were randomly assigned to three treatment groups (n = 15): an untreated control group, a S. pullorum-challenged group, and a group that received both PP and S. pullorum challenge. As illustrated in Figure 1, this design yielded the following three groups: control (CON; negative control, basal diet without Salmonella challenge), Salmonella-infected CON (SP; positive control, Salmonella challenge only), and Salmonella-infected + pediocin-treated (SPA) groups. Starting on day 3 (when chickens were 10 days old), chickens in the SP and SPA groups were orally inoculated with 1 mL of actively growing S. pullorum culture (1.0 × 107 CFU/mL) for six consecutive days. During the same period, chickens in the CON groups received an equal volume of LB liquid medium. On the 9th day (when chickens were 16 days old), the chickens in the SPA group were orally administered 1 mL of the PP preparation (1.28 × 102 AU) every day for 6 consecutive days until the end of the experiment. During the same period, chickens in the CON groups received an equal volume of YPD liquid medium. Each treatment included 5 replicate cages with 3 chickens per cage. All birds were maintained under uniform environmental conditions in accordance with the Management Guide for chickens. A corn–soybean meal basal diet without antibiotics was provided, which was formulated to meet or exceed the nutrient requirements recommended by the NRC (2004). Chickens were housed under controlled conditions with a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. Throughout the 15-day experimental period, chickens were group-housed in single-tier stainless-steel cages (1.2 m × 0.9 m × 0.7 m) and provided access to feed and water ad libitum.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the experimental design. Forty-five 7-day-old specific-pathogen-free (SPF) chickens were randomly assigned to three groups: control (CON), Salmonella pullorum infection (SP), and infection plus pediocin PP treatment (SPA). Starting on Day 3 (10 days of age), chickens in the SP and SPA groups were orally inoculated with S. pullorum (1.0 × 107 CFU/mL/day) for 6 consecutive days, while CON group received sterile LB medium. From Day 9 (16 days of age), chickens in the SPA group received daily oral administration of pediocin PP preparation (1.28 × 102 AU/day) for 6 days, while the CON and SP groups received sterile YPD medium. Key sampling time points are indicated.

2.4. Sample Collection

On days 6 and 12 post-infection (corresponding to days 16 and 22 of the experiment), blood samples were collected from 5 chickens per group (1 sample per replicate cage) into coagulant-containing vacuum tubes and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting serum was transferred into 3 aliquots and stored at −20 °C until subsequent analyses. Serum samples were used to determine aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), Serum creatinine (CREA), and Serum urea (UREA) levels, and other biochemical parameters. Serum C-reactive protein (CRP), serum amyloid A (SAA), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6, immunoglobulin (Ig)M, and IgG were determined following the manufacturers’ instructions in the corresponding assay kits (Nanjing Jianjian Bioengineering Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China).

On days 6 and 12 post-infection, at each sampling time point, one bird was randomly selected and euthanized from each of the 5 replicate cages per group. This resulted in n = 5 chickens per group per time point. Euthanasia was performed via intravenous injection of sodium pentobarbital. Cecal contents from chickens were collected before the end of the trial. Two samples from each replicate were randomly selected, mixed thoroughly, centrifuged, and immediately frozen in dry ice before storage at −80 °C for subsequent analysis of cecal microbiota diversity. Mid-jejunal tissue samples (approximately 2 cm in length) from each bird were excised, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for subsequent mRNA analysis.

2.5. Total RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) to Determine the Transcript Levels of Relevant Genes in the Jejunum

Total RNA from tissue samples (50 mg) was isolated from snap-frozen jejunal tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The concentration and purity of total RNA were determined using a microplate reader (Multiskan Sky, 1.00.55, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using a 260:280 nm absorbance ratio. Absorbance ratios (optical density [OD]260/OD280) between 1.8 and 2.0 for total RNA samples are considered to be of acceptable purity. First, complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using a Fast King reverse-transcription kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China, kit No. KR116) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and stored at −20 °C until further processing. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using an Applied Biosystems Bio-Rad Real-Time PCR system (Bio-Rad, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and Premix Ex Taq with SYBR Green (Tiangen, China, kit No. FP205). The total reaction mixture was 20 μL, which consisted of 10.0 μL of 2× SYBR PreMix plus, 1.0 μL of cDNA, 0.6 μL of each primer (10 mmol/L), and 7.8 μL RNase-free water. For PCR, the thermal cycling protocol was 15 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s each; denaturation at 95 °C, annealing/extension at 60 °C for 34 s; and final melting. Melting curve analysis was performed to monitor the purity of the PCR products. Oligonucleotide primers included chicken IL-1β, IL-6, ZO-1, claudin, occludin, MUC2, TFF3, TGF-β1, and TNF-α (Table 1). Gene expression sequences were designed using Primer Express 5.0 based on the sequences available in public databases. The average gene expression relative to GAPDH was calculated for each sample using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Table 1.

Primer sequences.

2.6. Histological Assessment

Morphological characteristics of the intestine were assessed by measuring jejunal villi height (VH), crypt depth (CD), and the VH:CD ratio. Briefly, jejunal tissue samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and jejunal tissues were subsequently embedded in paraffin and sectioned into 5-μm-thick sections. The prepared sections were stained using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and analyzed for jejunal morphometry. VHs and the corresponding CDs of the small intestine were measured using ImageJ software (version 1.54i; National Institutes of Health, USA), and the VH:CD ratio was calculated to complete intestinal histomorphometric analysis.

2.7. Microbiota Analysis

Total DNA from the cecal contents of chickens was extracted using a QiagenDNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Shanghai, China), and the extracted DNA was purified and tested for purity and concentration following the manufacturer’s instructions in the kit. The extracted DNA was used as a template for the PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA V3–V4 region of bacteria. PCR products were analyzed using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, cut gel recovery, and Tris-HCl elution, followed by high-throughput sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq platform, clustering of operational taxonomic units (OTUs), and bioinformatics statistical analysis. Results from OTU clustering analysis were analyzed to determine diversity in colony composition.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Experimental data were initially organized in Microsoft Excel, and one-way analysis of variance was used for analysis in SPSS 23.0. The results are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), and differences between groups were compared using t-tests and visualized with GraphPad Prism 9 software. Differences with p < 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 were considered statistically significant (*), highly significant (**), and extremely significant (***), respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Serum Indices

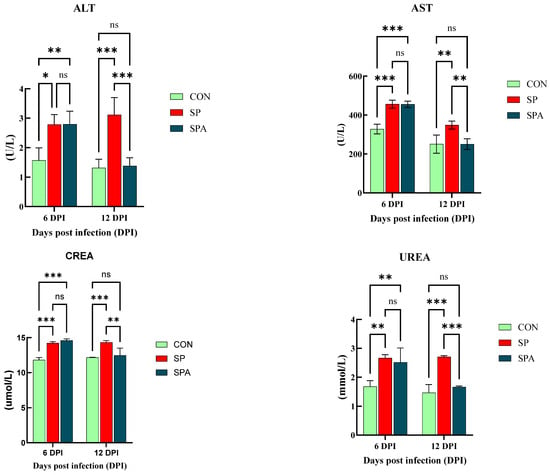

Significant differences in serum biochemical indices were observed among the groups on days 6 and 12 of the intervention (Figure 2). Specifically, on 6 DPI, serum ALT and AST levels were significantly higher (p < 0.05) in both the SP and SPA groups compared with those in the CON group. Moreover, CREA and UREA levels were significantly higher than those in the CON group. On 12 DPI, the SP group continued to show significantly elevated ALT and AST (p < 0.05) compared with those in the normal control group. Notably, the liver and kidney function indices of PP-treated chickens in the SPA group showed significant improvement, approaching normal levels by the end of the experiment.

Figure 2.

Effect of Salmonella pullorum and pediocin PP on serum liver and renal function in chickens. ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; CREA: Serum creatinine; UREA: Serum urea; UREA: Urea uric acid. * denotes p < 0.05; ** denotes p < 0.01; *** denotes p < 0.001; ns denotes p > 0.05.

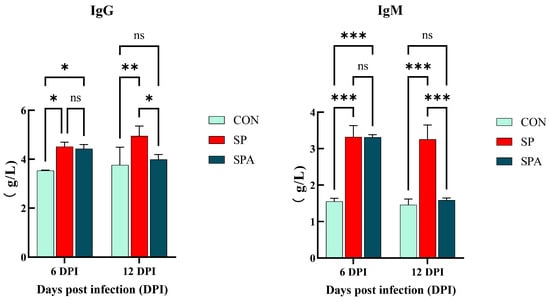

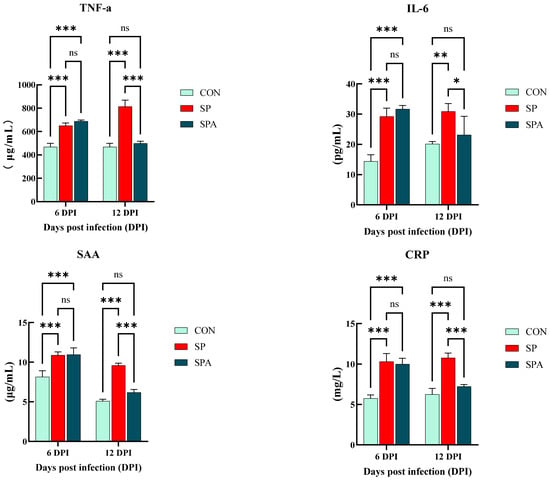

As shown in Figure 3, serum IgG and IgM levels were significantly elevated in the SP and SPA groups compared with those in the CON group on 6 DPI of the experiment (p < 0.05). As shown in Figure 4, serum IL-6, TNF-α, SAA, and CRP levels were significantly elevated in the SP and SPA groups compared with those in the CON group on 6 DPI of the experiment (p < 0.05). After 6 days of PP infusion (on 12 DPI), serum IgG, IgM, TNF-α, IL-6, SAA, and CRP levels in the SPA group were significantly lower than those in the SP group (p < 0.05) and returned to near-normal levels by the end of the experiment.

Figure 3.

Effect of Salmonella pullorum and pediocin PP on serum immunity of intestinal damage in chickens. IgG: ImmunogIobuIin G; IgM: ImmunogIobuIin M. * denotes p < 0.05; ** denotes p < 0.01; *** denotes p < 0.001; ns denotes p > 0.05.

Figure 4.

Effect of Salmonella pullorum and pediocin PP on serum pro-inflammatory factors and markers of intestinal damage in chickens. TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α; IL-6: Interleukin-6; SAA: serum amyloid A; CRP: C-reactive protein.* denotes p < 0.05; ** denotes p < 0.01; *** denotes p < 0.001; ns denotes p > 0.05.

3.2. Histological Assessment

Figure 5 and Table 2 demonstrate the effects of PP supplementation on the jejunum morphology of Salmonella-infected SPF chickens. As shown in Figure 5A–C, at 6 DPI, the jejunum villus height (VH) and villus-to-crypt ratio (VH:CD ratio) values were significantly higher in the CON groups than in the SP and SPA groups. At 12 DPI, the villus height and villus-to-crypt ratio in the SP group remained significantly lower than in the CON group. However, after PP intervention, the jejunum VH and VH:CD ratio values in the SPA group were significantly higher than those in the SP group (Figure 5D–F), but did not differ significantly from those in the CON groups.

Figure 5.

Effect of pediocin PP intervention on the jejunum morphology of chickens with S. pullorum. Magnification was 5× and 10×, n = 5 chickens per treatment. Representative photomicrographs of jejunal sections from chickens. (A–C) Sections from the CON, SP, and SPA groups at 6 DPI, respectively. (D–F) Sections from the CON, SP, and SPA groups at 12 DPI, respectively.

Table 2.

Effect of PP intervention on the jejunum morphology of chickens with S. pullorum of broiler chickens at 6 DPI and 12DPI.

3.3. Real-Time qPCR

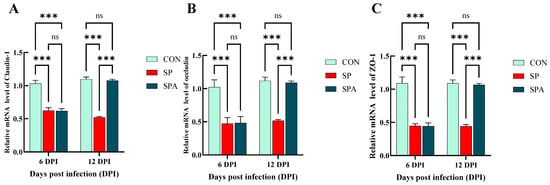

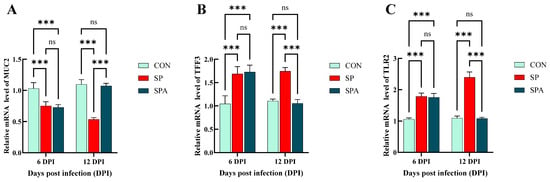

The mRNA expression of claudin-1, occludin, and Zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) is indicative of the functional status of the intestinal barrier. As shown in Figure 6A–C, on 6 DPI, Salmonella infection significantly decreased the expression of the mucosal tight junction (TJ) genes claudin-1, occludin, and ZO-1 in the jejunum of the SP and SPA groups. At 12 days post intervention, the expression levels of the TJ genes in the jejunal mucosa increased significantly in the SPA group and approached the values for the control group compared with those noted for the SP group. As shown in Figure 7A,B, at 6 DPI, Salmonella infection significantly decreased the expression of the chemical barrier-related gene Mucin 2 (MUC2) in the jejunum of both SP and SPA groups, while markedly increasing trefoil factor family 3 (TFF3) expression. At 12 DPI, the expression of chemical barrier-related genes MUC2 in the jejunum in the SPA group significantly increased, while the expression of TFF3 significantly decreased and approached the expression noted in the control group when compared with that in the SP group.

Figure 6.

Effects of Salmonella pullorum and pediocin PP on the expression of jejunal barrier–related genes in chickens. (A–C) Physical barrier genes in the jejunum. Vertical bars represent standard errors. n = 5 chickens for each treatment. ZO-1: zonula occludens-1. *** denotes p < 0.001; ns denotes p > 0.05.

Figure 7.

Effects of Salmonella pullorum and pediocin PP on the expression of jejunal barrier–related genes in chickens. (A,B) Chemical barrier genes in the jejunum. (C) Immune barrier genes in the jejunum. Vertical bars represent standard errors. n = 5 chickens for each treatment. MUC2: Mucin 2; TFF3: Trefoil factor family 3; TLR2: Toll Like Receptor 2. *** denotes p < 0.001; ns denotes p > 0.05.

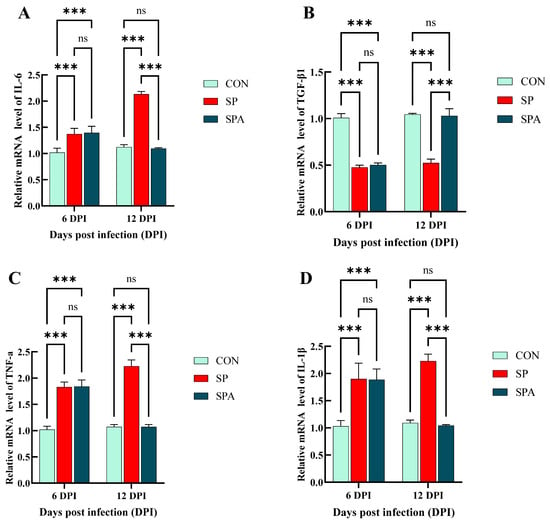

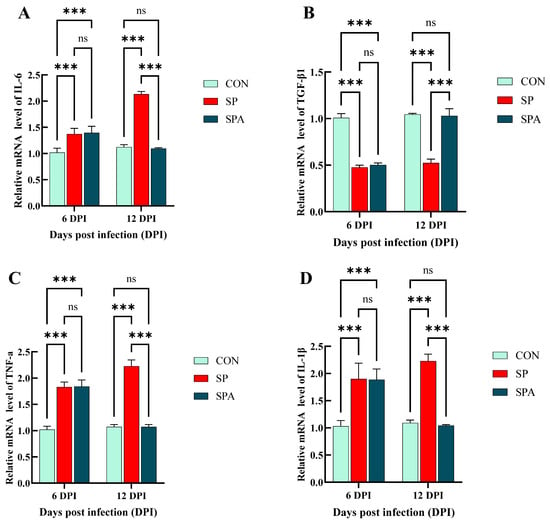

As shown in Figure 7C and Figure 8A–D, Salmonella infection significantly reduced (p < 0.05) the expression of the immune-related gene transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) in the jejunum, while significantly upregulating that of Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. After 6 days of intervention, the expressions of jejunal immune-related genes TLR2, TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in the treatment group decreased significantly, while TGF-β1 increased significantly and approached those of the control group when compared with that in the SP group.

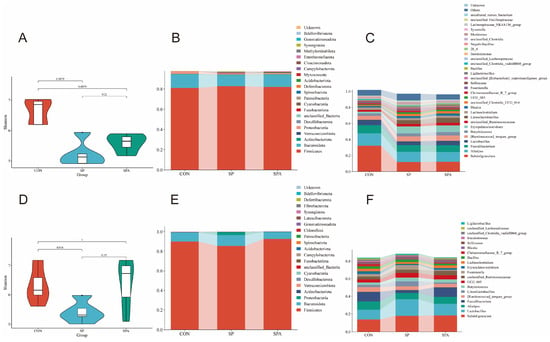

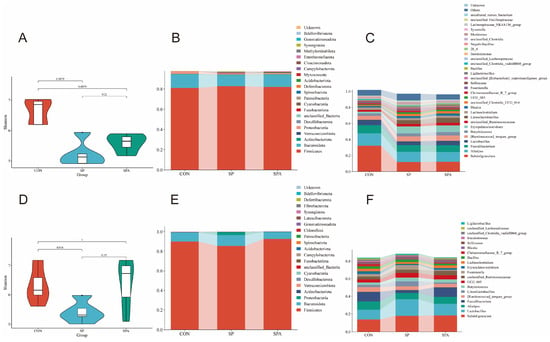

3.4. Microbiota Analysis

To determine the effects of PP supplementation on the intestinal microbiota of S. pullorum-infected chickens, high-throughput sequencing of the V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was conducted using cecal samples (n = 5 per group) from the CON, SP, and SPA groups. As shown in Figure 9A,D, significant differences in the α-diversity of the gut microbiota (measured using the Shannon index) were noted among groups on 6 DPI. Specifically, the Shannon indices in the CON groups were significantly higher than those in the SP and SPA groups. However, on 12 DPI, the Shannon index of the SPA group did not differ significantly from that of the CON groups, indicating that PP supplementation partially restored the decreased microbial diversity resulting from Salmonella infection.

Phylogenetic analyses revealed distinct compositional profiles of the cecal microbiota at both the phylum and genus levels across treatment groups (Figure 9B,C,E,F). At the phylum level, all groups showed an abundance of Firmicutes and Bacteroidota on 6 DPI. At 6 DPI, the relative abundances of Proteobacteria and Verrucomicrobia were significantly reduced in both the SP and SPA groups compared with those in the control group (p < 0.05; see detailed statistical analysis in Table 3). At 12 DPI, Firmicutes remained dominant in all groups, whereas PP supplementation significantly increased the relative abundances of Firmicutes and Actinobacteriota in the SPA group compared with those in the SP group (p < 0.05) (Table 3).

Figure 8.

Effects of Salmonella pullorum and pediocin PP on the expression of inflammatory genes in the jejunum of chickens. (A,B) jejunal pro-inflammatory genes; (C,D) jejunal anti-inflammatory genes. Vertical bars represent standard errors. n = 5 chickens for each treatment. IL-6: Interleukin-6; TGF-β1: transforming growth factor-β1; TNF-α: Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha; IL-1β: Interleukin-1β treatment. *** denotes p < 0.001; ns denotes p > 0.05.

Table 3.

Effect of PP intervention on the jejunal phylum levels of chickens with S. pullorum of broiler chickens at 6 DPI and 12DPI.

At the genus level, Subdoligranulum (32.36%), Alistipes (13.47%), and Faecalibacterium (10.02%) were predominant across all groups on 6 DPI. On 6 DPI, both SP and SPA groups showed significantly higher abundances of Erysipelatoclostridium but lower abundances of Subdoligranulum and Alistipes compared with those in the CON group. On 12 DPI, the SPA group exhibited higher levels of Faecalibacterium and Butyricicoccus compared with those in the SP group.

Figure 9.

Effects of S. pullorum and pediocin PP on the diversity of the cecal microbiota in chickens. (A,D) Shannon indices on 6 DPI and 12 DPI; (B,C) Relative abundance of the top 20 phyla (B) and genera (C) in each group on 6 DPI. (E,F) Relative abundance of the top 20 phyla (E) and genera (F) in each group on 12 DPI. n = 5 chickens for each treatment.

4. Discussion

Chicken dysentery is an acute or chronic infectious disease caused by S. pullorum. Pullorum disease, caused by Salmonella pullorum, primarily affects chicks aged 2–3 weeks. Infected chicks often exhibit huddling together for warmth, lethargy, loss of appetite, and dehydration, with characteristic white, paste-like droppings around the vent [21]. Cheng [22] found that within 5 to 7 days post-infection with Salmonella Pullorum, all chickens exhibited symptoms of labored breathing and mental depression, with some mortality occurring. The study also revealed a significant upregulation in the expression of inflammatory factors—tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and IL-8 in both lung and spleen tissues. Furthermore, histopathological examination indicated swelling of the lung tissue accompanied by distinct lesions. Previous studies have shown that S. pullorum infection significantly reduces the average body weight of Hongguang-Black 1-day-old breeder chicks [23]. This disease mainly affects poultry and is particularly harmful to young chickens [24]. Urea is an end product of protein metabolism that is primarily synthesized in the liver and excreted by the kidneys [25]. CREA, a product of muscle metabolism, is also mainly excreted via the kidneys. Moreover, CREA is commonly used as an auxiliary indicator when evaluating renal function in poultry in clinical settings [26]. A previous study has reported that Salmonella infection significantly increases serum alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and alkaline phosphatase activity, as well as UREA and CREA level [27]. Our findings revealed that S. pullorum infection raised the levels of UREA and CREA, while its level was close to the control group when supplemented with pediocin PP, suggesting that PP supplementation could alleviate dysentery in chickens after S. pullorum infection. ALT and AST are key enzymes that catalyze transamination reactions between amino acids and keto acids. In mammals, these enzymes are released into the circulation when hepatocyte membranes are disrupted due to cellular injury or metabolic dysfunction. The extent of increase in serum ALT levels is positively correlated with the severity of hepatocellular damage, making it a reliable biomarker in assessing liver function [28,29]. Findings suggest that elevated ALT levels following Salmonella infection may reflect the capacity of the pathogen in colonizing hepatic tissues and inducing hepatocellular damage [30]. Previous studies have reported that S. enteritidis (SE) infections could significantly increase ALT activity in 1- and 7-day-old chicks within the SE-infected subgroup (S-II) compared with those in the Intebiot-fed, SE + sage extract-fed, and negative control groups [31]. Similarly, among S. pullorum-infected chicks, the SP-challenged subgroup exhibited hepatic hemorrhage and focal necrosis compared with those in the CON and treatment subgroups that received 0.5%, 1%, or 1.5% acetic acid. Notably, supplementation with 1% acetic acid markedly reduced the severity and frequency of these pathological lesions [32]. Our findings revealed a significant increase in ALT and AST levels in both infected groups (SP and SPA) on 6 DPI. Similar findings have been reported in 1-day-old Salmonella-challenged SPF Lohmann broiler chicks, where AST activity was significantly increased at 1, 3, and 5 days post-infection [33]. Therefore, our present results suggest that Salmonella infection exerts negative physiological effects on poultry, whereas supplementation with PP may confer hepatoprotective benefits [34,35,36].

S. pullorum infection induces inflammatory responses by releasing cytokines and disrupting the intestinal barrier, thereby altering systemic immune parameters [37]. In our study, S. pullorum challenge markedly increased serum IgG and IgM levels, consistent with previous findings showing Salmonella-induced humoral immune activation [38]. Colonization of the gastrointestinal tract by Salmonella can compromise the intestinal barrier and activate mucosal immune pathways, triggering TNF-α and IL-6 release and promoting systemic inflammation [39]. In the current study, S. pullorum challenge markedly increased IL-6 levels, whereas PP supplementation significantly reduced TNF-α and IL-6 levels, indicating the anti-inflammatory effect of PP. SAA and CRP are acute-phase proteins and sensitive markers of inflammation [40]. In this study, S. pullorum infection significantly elevated serum SAA and CRP levels, likely reflecting the systemic inflammatory response triggered by Salmonella. Pathogen invasion activates the innate immune system in the host, stimulating hepatic synthesis of acute-phase proteins such as SAA and CRP, whose elevated concentrations indicate the severity of infection-induced inflammation [41,42]. PP supplementation reduced SAA and CRP levels, suggesting that PP could alleviate SP-induced intestinal barrier disruption and systemic inflammation.

Our findings also demonstrated that Salmonella infection significantly decreased the jejunal expression of the immunomodulatory cytokine TGF-β1 while markedly increasing the expression of TLR2, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. These findings highlight the complex regulatory effects of Salmonella on the intestinal immune response and provide insights into its pathogenic mechanisms. TGF-β1 is a multifunctional cytokine crucial for maintaining immune homeostasis, suppressing inflammation, and promoting tissue repair [43]. The downregulation of TGF-β1 noted in our study may weaken immune regulation in the host, resulting in excessive inflammatory activation, consistent with previous studies that have also suggested that Salmonella promotes inflammation by inhibiting the expression of TGF-β1 [44]. This imbalance may further aggravate intestinal inflammation, facilitating Salmonella colonization and tissue invasion. Conversely, the expressions of TLR2, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 were significantly upregulated after infection. TLR2, a member of the pattern recognition receptor family, detects pathogen-associated molecular patterns and initiates innate immune signaling [45]. Elevated TLR2 expression indicates activation of the innate immune system of the host, whereas the upregulation of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 reflects an intense inflammatory response that may result in tissue injury and compromise barrier integrity [46]. Remarkably, on 12 DPI, the expression of these immune-related genes was almost similar to that in the control group. This finding suggests that PP intervention can restore intestinal immune balance by upregulating TGF-β1 levels and downregulating those of TLR2, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. Enhanced TGF-β1 expression may suppress excessive inflammation, whereas normalization of the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines promotes tissue recovery. These findings were consistent with previous reports that probiotics and bioactive compounds ameliorate intestinal inflammation by modulating immune-related gene expression [47,48]. Overall, Salmonella infection disrupts intestinal immune homeostasis via differential regulation of pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators, whereas PP supplementation re-establishes the immune balance and promotes mucosal healing.

Maintaining the integrity of the intestinal morphology is essential for effective nutrient absorption owing to its crucial role in preserving the intestinal barrier. Intestinal villi are vital structural components of the small intestine that are responsible for nutrient uptake [49]. Previous studies have reported that S. pullorum infections severely damage intestinal villi and decrease nutrient absorption [50]. In our study, S. pullorum infection markedly impaired the jejunal VH and VH:CD ratio, which may have contributed to the observed decline in growth performance. Similarly, previous studies have demonstrated that Lactobacillus paracasei KL1 and L. plantarum can mitigate histopathological lesions in the intestine and preserve villus integrity in S. dysenteriae-infected chicks [51]. Supplementation with bacteriocins has been shown to improve intestinal histomorphology in Japanese quail [52]. Consistent with these findings, supplementing the diet with PP in our study enhanced VH, alleviated S. pullorum infection–induced jejunal damage, and promoted faster epithelial regeneration and improved nutrient absorption. Notably, after PP intervention, the SPA group exhibited a significantly increased jejunal VH and VH:CD ratio, with values comparable to those in the CON groups. These results indicate that PP could effectively alleviate S. pullorum-induced intestinal morphological damage to near-normal levels. This finding aligns with that reported previously that probiotics and their metabolites strengthen the intestinal barrier by promoting epithelial proliferation and differentiation [53], thereby enhancing resistance to pathogenic infection. In conclusion, PP supplementation could effectively mitigate S. pullorum-induced intestinal injury and promote intestinal recovery.

TJs of the intestinal epithelium are crucial for maintaining barrier integrity, with occludin, claudin-1, and ZO-1 serving as core structural proteins [54]. The expression of these proteins is positively correlated with intestinal barrier function, and their downregulation can compromise TJ integrity, increasing intestinal permeability [55,56]. Salmonella infection significantly decreases the expression of barrier function-related genes and increases epithelial permeability [57,58]. Bu et al. [59] have reported that bacteriocin-producing L. plantarum can markedly upregulate intestinal ZO-1 and claudin-1 expression in mice, thereby exerting an enteroprotective effect. Similarly, Enterococcus species can attenuate diet-induced intestinal inflammation and preserve epithelial integrity [60,61]. In the current study, S. pullorum infection significantly downregulated the mRNA expression of occludin and claudin-1 in the jejunum of broilers. However, PP supplementation reversed this effect by upregulating claudin-1 expression, consistent with previous observations. These findings collectively suggest that PP mitigates S. pullorum infection-induced impairment of intestinal barrier function by modulating the expression of TJ proteins.

MUC2 and TFF3 are key regulators of the intestinal chemical barrier and play a crucial role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis and defending against pathogenic infection [62,63]. In this study, S. pullorum infection significantly downregulated MUC2 expression in the jejunum while markedly upregulating that of TFF3, revealing the dual regulatory effect of Salmonella on the intestinal chemical barrier. MUC2 is the primary structural component of the intestinal mucus layer. It is secreted by goblet cells to form a protective barrier that prevents pathogens from directly coming into contact with epithelial cells [64]. The downregulation of MUC2 observed in our study likely reduced the thickness of the mucus layer and weakened the intestinal defense against Salmonella, consistent with previous studies that have reported that pathogenic infections disrupt barrier integrity by inhibiting MUC2 expression [65]. Reduced MUC2 expression may also exacerbate intestinal inflammation, thereby facilitating Salmonella colonization and invasion. In contrast, TFF3 expression is significantly upregulated after Salmonella infections. TFF3, a member of the trefoil factor family, plays an important role in mucosal repair and regulating inflammation [66]. Its upregulation may represent a compensatory host response aimed at promoting epithelial cell migration, tissue repair, and attenuation of inflammation. However, increased TFF3 expression has been associated with chronic inflammation and pathological conditions [67]. Notably, PP supplementation normalized the expression of both MUC2 and TFF3, suggesting its ability to restore the chemical barrier function of the intestine by modulating these genes. Upregulation of MUC2 is associated with mucus layer reconstruction and reinforcement of the intestinal physical barrier, whereas restoring TFF3 expression promotes epithelial repair and mitigates inflammation. These findings align with previous findings that probiotics and certain pharmacological agents can enhance the integrity of the intestinal barrier by regulating the expression of MUC2 and TFF3 [68,69]. Overall, PP supplementation effectively alleviated S. pullorum-induced disruption of the intestinal chemical barrier by restoring the expression of MUC2 and TFF3.

The cecal microbiota plays a crucial role in nutrient absorption, host immunity, and intestinal defense [70,71]. However, infections by intestinal pathogens disrupt microbial homeostasis, leading to intestinal inflammation and impaired growth performance [72]. In our study, the effects of PP supplementation on the intestinal microbial composition of chickens infected with S. pullorum were systematically analyzed using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Salmonella infection significantly reduced the α-diversity of the intestinal microorganisms, which was partially restored after PP intervention. At the phylum level, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes were predominant in all experimental groups, consistent with previous reports on avian intestinal microbiota composition [73]. PP supplementation significantly increased the relative abundance of Actinobacteria, suggestive of its probiotic effect by modulating specific microbial taxa. At the genus level, PP treatment markedly increased the relative abundance of Faecalibacterium and Lactobacillus, both of which are known to exert anti-inflammatory and probiotic effects [74,75]. Furthermore, the relative abundance of Faecalibacterium and Butyricicoccus, genera strongly associated with short-chain fatty acid production and intestinal health, was significantly elevated in the PP-treated groups [76]. Overall, PP supplementation partially restored the microbial diversity that was disrupted by Salmonella infection and promoted the proliferation of beneficial bacteria, thereby re-establishing the intestinal microbial balance and improving gut health.

5. Conclusions

Our study provides preliminary evidence that supplementation with PP alleviates the inflammatory response in S. pullorum-challenged chickens. Moreover, PP supplementation mitigated the subclinical Salmonella infection by improving intestinal morphology and barrier function and optimizing the composition of the cecal microbiota. Our findings offer a theoretical basis for the protective role of PP in reducing S. pullorum infections and highlight its potential as a therapeutic strategy in controlling avian salmonellosis. Overall, this study not only elucidates the underlying mechanisms by which PP mitigates S. pullorum infections but also offers a valuable tool for therapeutic intervention.

Author Contributions

C.Z.: carried out the chicken experiment and writing—original draft; H.L. and B.Y.: formal analysis and data curation; Z.Z., M.Z. and S.Z.: carried out the chicken experiment; D.Z. and Z.F.: rewriting—original and data curation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Innovation Capacity Building Project of the Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences (KJCX20240507), the Public institution project of Institute of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Medicine (XMS202516), and Innovation Capacity Building Project of the Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences (KJCX20251102).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was performed according to the relevant animal welfare guidelines (IHVM11-2302-8) (25 September 2025) of the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Medicine, Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, China.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The sequences of metagenomes presented in this study are openly available in GenBank under BioProject PRJNA1354233.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| CREA | Serum creatinine |

| UREA | Urea uric acid |

| IgG | ImmunogIobuIin G |

| IgM | ImmunogIobuIin M |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| SAA | serum amyloid A |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| ZO-1 | zonula occludens-1 |

| MUC2 | Mucin 2 |

| TFF3 | Trefoil factor family |

| TLR2 | Toll Like Receptor 2 |

| TGF-β1 | transforming growth factor-β1 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

References

- Gast, R.K.; Porter, R.E., Jr. Salmonella Infections. In Diseases of Poultry; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 717–753. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Jia, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Lv, H.; Wu, S.; Qi, G. Supplemental Plant Extracts from Flos lonicerae in Combination with Baikal skullcap Attenuate Intestinal Disruption and Modulate Gut Microbiota in Laying Hens Challenged by Salmonella pullorum. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruesga-Gutiérrez, E.; Ruvalcaba-Gómez, J.M.; Gómez-Godínez, L.J.; Villgrán, Z.; Gómez-Rodríguez, V.M.; Heredia-Nava, D.; Ramírez-Vega, H.; Arteaga-Garibay, R.I. Allium-Based Phytobiotic for Laying Hens’ Supplementation: Effects on Productivity, Egg Quality, and Fecal Microbiota. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schat, K.A.; Nagaraja, K.V.; Saif, Y.M. Pullorum Disease: Evolution of the Eradication Strategy. Avian Dis. 2021, 65, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Ran, X.; Qiu, H.; Zhao, S.; Hu, Z.; Wang, J.; Ni, H.; Wen, X. Seroprevalence of pullorum disease in chicken across mainland China from 1982 to 2020, A systematic review and meta-analysis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022, 152, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zeng, Z.; Zhou, D.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Han, Y.; Qin, M.; Luo, C.; Feng, S.; et al. Effect of oral administration of microcin Y on growth performance, intestinal barrier function and gut microbiota of chicks challenged with Salmonella pullorum. Vet. Res. 2024, 55, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, C.X.; Tan, L.T.H.; Ab Mutalib, N.S.; Pusparajah, P.; Goh, B.H.; Chan, K.G.; Letchumanan, V.; Lee, L.H. Unveiling the Impact of Antibiotics and Alternative Methods for Animal Husbandry: A Review. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sazykin, I.S.; Khmelevtsova, L.E.; Seliverstova, E.Y.; Sazykina, M.A. Effect of Antibiotics Used in Animal Husbandry on the Distribution of Bacterial Drug Resistance (Review). Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2021, 57, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasimanickam, V.; Kasimanickam, M.; Kasimanickam, R. Antibiotics Use in Food Animal Production: Escalation of Antimicrobial Resistance: Where Are We Now in Combating AMR? Med. Sci. 2021, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara, A.; Maekawa, M.; Nakagawa, K. The mechanism of action of nisin in promoting poultry through tight junction integrity and dendritic cell anti-inflammatory properties. Arch. Microbiol. 2025, 207, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglani, R.; Parveen, N.; Kumar, A.; Dewali, S.; Rawat, G.; Mishra, R.; Panda, A.K.; Bisht, S.S. Bacteriocin and its biomedical application with special reference to Lactobacillus. In Recent Advances and Future Perspectives of Microbial Metabolites; De Mandal, S., Xu, X., Jin, F., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 123–146. [Google Scholar]

- Smaoui, S.; Echegaray, N.; Kumar, M.; Chaari, M.; D’Amore, T.; Ali Shariati, M.; Rebezov, M.; Lorenzo, J.M. Beyond Conventional Meat Preservation: Saddling the Control of Bacteriocin and Lactic Acid Bacteria for Clean Label and Functional Meat Products. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 196, 3604–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, K.; Huang, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xia, T.; Yun, F.; Zhong, J. Food and gut originated bacteriocins involved in gut microbe-host interactions. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 49, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Tian, F.; Yu, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, Q.; Chen, W. Effect of bacteriocin-producing Pediococcus acidilactici strains on the immune system and intestinal flora of normal mice. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2022, 11, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bu, Y.; Cao, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Hao, L.; Yi, H. Effect of Fermented Milk Supplemented with Nisin or Plantaricin Q7 on Inflammatory Factors and Gut Microbiota in Mice. Nutrients 2024, 16, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.A.T.; de Melo, M.R.; da Silva, C.M.R.; Jain, S.; Dolabella, S.S. Nisin resistance in Gram-positive bacteria and approaches to circumvent resistance for successful therapeutic use. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 47, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorshidian, N.; Khanniri, E.; Mohammadi, M.; Yousefi, M. Antibacterial Activity of Pediocin and Pediocin-Producing Bacteria Against Listeria monocytogenes in Meat Products. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 709959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, E.; Messina, M.R.; Catelli, E.; Morlacchini, M.; Piva, A. Pediocin A improves growth performance of broilers challenged with Clostridium perfringens. Poult. Sci. 2009, 88, 2152–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulski, D.; Jankowski, J.; Naczmanski, J.; Mikulska, M.; Demey, V. Effects of dietary probiotic (Pediococcus acidilactici) supplementation on performance, nutrient digestibility, egg traits, egg yolk cholesterol, and fatty acid profile in laying hens. Poult. Sci. 2012, 91, 2691–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Jiang, J.; Li, B.; Ross, R.P.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Yang, B.; Chen, W. Effects of the short-term administration of Pediococcus pentosaceus on physiological characteristics, inflammation, and intestinal microecology in mice. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 1695–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhanu, G.; Fulasa, A. Pullorum Disease and Fowl Typhoid in Poultry: A Review. Br. J. Poult. Sci. 2020, 9, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, W.; Wen, G.; Luo, H.; Shao, H.; Zhang, T. Evaluation of young chickens challenged with aerosolized Salmonella pullorum. Avian Pathol. 2020, 49, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, C.; Li, C.; Wang, M.; Chen, W.; Zhou, C.; Wei, P. The effect of oregano essential oil on the prevention and treatment of Salmonella pullorum and Salmonella gallinarum infections in commercial Yellow-chicken breeders. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 1058844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, F.; Yi, J.; Xiao, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; He, X.; Song, Z. Protective effect and possible mechanism of arctiin on broilers challenged by Salmonella pullorum. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, skac126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeyomoye, O.I.; Akintayo, C.O.; Omotuyi, K.P.; Adewumi, A.N.; Adewumi, A.N. The Biological Roles of Urea: A Review of Preclinical Studies. Indian J. Nephrol. 2022, 32, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, M.; Kaddurah-Daouk, R. Creatine and Creatinine Metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 2000, 80, 1107–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, S.; Ihedioha, J.; Ezema, W. Experimental Salmonella gallinarum Infection in Young Pullets: Correlation of Serum Biochemistry with Organ Pathology. Acta Vet. Eurasia 2025, 51, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, M.R. The past and present of serum aminotransferases and the future of liver injury biomarkers. EXCLI J. 2016, 15, 817–828. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Ni, T.; Tang, W.; Yang, G. The Role of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound in the Differential Diagnosis of Tuberous Vas Deferens Tuberculosis and Metastatic Inguinal Lymph Nodes. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Alam, J.; Rahman, M.M.; Khan, M.A.H.N.A.; Haider, M.G. Pathology of Pullorum Disease and Molecular Characterization of Its Pthogen. Ann. Bangladesh Agric. 2019, 23, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laptev, G.Y.; Yildirim, E.A.; Ilina, L.A.; Filippova, V.A.; Kochish, I.I.; Gorfunkel, E.P.; Dubrovin, A.V.; Brazhnik, E.A.; Narushin, V.G.; Novikova, N.I.; et al. Effects of Essential Oils-Based Supplement and Salmonella Infection on Gene Expression, Blood Parameters, Cecal Microbiome, and Egg Production in Laying Hens. Animals 2021, 11, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, G.; Ramzaan, R.; Khattak, F.; Raheela, R. Effects of acetic acid supplementation in broiler chickens orallychallenged with Salmonella pullorum. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2016, 40, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Hussain, S.; Tang, T.; Gou, Y.; He, C.; Liang, X.; Yin, Z.; Shu, G.; Zou, Y.; Fu, H.; et al. Protective Effects of Cinnamaldehyde on the Oxidative Stress, Inflammatory Response, and Apoptosis in the Hepatocytes of Salmonella gallinarum-Challenged Young Chicks. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 2459212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams Shargh, M.; Dastar, B.; Zerehdaran, S.; Khomeiri, M.; Moradi, A. Effects of using plant extracts and a probiotic on performance, intestinal morphology, and microflora population in broilers. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2012, 21, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, A.A.; Yalçın, S.; Latorre, J.D.; Basiouni, S.; Attia, Y.A.; El-Wahab, A.A.; Visscher, C.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Huber, C.; Hafez, H.M.; et al. Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Phytogenic Substances for Optimizing Gut Health in Poultry. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigley, P. Salmonella and Salmonellosis in Wild Birds. Animals 2024, 14, 3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulwahhab, A.I.; Al-Zuhariy, M.T. Immunological Status of Salmonella pullorum-Infected Broilers Treated with Bacillus Subtilis, Organic Acids and Ciprofloxacin. Iraqi J. Agric. Sci. 2025, 56, 1045–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withanage, G.S.K.; Wigley, P.; Kaiser, P.; Mastroeni, P.; Brooks, H.; Powers, C.; Beal, R.; Barrow, P.; Maskell, D.; Maskell, I. Cytokine and Chemokine Responses Associated with Clearance of a Primary Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Infection in the Chicken and in Protective Immunity to Rechallenge. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 5173–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, S.; Hardt, W.D. Mechanisms conferring multi-layered protection against intestinal Salmonella Typhimurium infection. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2025, 49, fuaf038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, T. Comparative evaluation of acute phase proteins by C-reactive protein (CRP) and serum amyloid A (SAA) in nonhuman primates and feline carnivores. Anim. Dis. 2022, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlting, C.; Wolf, S.D.; Bode, J.G. Acute-phase protein synthesis: A key feature of innate immune functions of the liver. Biol. Chem. 2021, 402, 1129–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, L. Acute phase protein response to viral infection and vaccination. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2019, 671, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travis, M.A.; Sheppard, D. TGF-β Activation and Function in Immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 32, 51–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.G.; Singhal, M.; Lin, Z.; Manzella, C.; Kumar, A.; Alrefai, W.A.; Dudeja, P.K.; Saksena, S.; Sun, J.; Gill, R.K. Infection with enteric pathogens Salmonella typhimurium and Citrobacter rodentium modulate TGF-beta/Smad signaling pathways in the intestine. Gut Microbes 2018, 9, 326–337. [Google Scholar]

- Suresh, R.; Mosser, D.M. Pattern recognition receptors in innate immunity, host defense, and immunopathology. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2013, 37, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voirin, A.C.; Perek, N.; Roche, F. Inflammatory stress induced by a combination of cytokines (IL-6, IL-17, TNF-α) leads to a loss of integrity on bEnd.3 endothelial cells in vitro BBB mode. Brain Res. 2020, 1730, 146647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Zhen, W.; Guo, F.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, K.; Kong, L.; Guo, Y.; Wang. ZPretreatment with probiotics Enterococcus faecium NCIMB11181 attenuated Salmonella Typhimurium-induced gut injury through modulating intestinal microbiome immune responses with barrier function in broiler chickens. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Liu, B.; Wang, N.; Yang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Sun, C.; Zhao, Y. Low fish meal diet supplemented with probiotics ameliorates intestinal barrier and immunological function of Macrobrachium rosenbergii via the targeted modulation of gut microbes and derived secondary metabolites. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1074399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, T.; Feng, Y.; Li, L.A. Common factors and nutrients affecting intestinal villus height—A review. Anim. Biosci. 2025, 38, 1557–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Han, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yan, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Song, W.; Ma, Y. Lactobacillus casei protects intestinal mucosa from damage in chicks caused by Salmonella pullorum via regulating immunity and the Wnt signaling pathway and maintaining the abundance of gut microbiota. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Xie, Y.; Xiong, L.; Liu, H.; Wang, F. Effects of a probiotic on the growth performance, intestinal flora, and immune function of chicks infected with Salmonella pullorum. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 5316–5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onder Ustundag, A.; Ozdogan, M. Effects of bacteriocin and organic acid on growth performance, small intestine histomorphology, and microbiology in Japanese quails (Coturnix coturnix japonica). Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2019, 51, 2187–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yu, Z.; Tian, F.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, Q.; Chen, W. Surface components and metabolites of probiotics for regulation of intestinal epithelial barrier. Microb. Cell Factories 2020, 19, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T. Regulation of the intestinal barrier by nutrients: The role of tight junctions. Anim. Sci. J. 2020, 91, e13357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Yin, L.; Li, J.Y.; Li, Q.; Shi, D.; Feng, L.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, W.D.; Wu, P.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Glutamate attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced oxidative damage and mRNA expression changes of tight junction and defensin proteins, inflammatory and apoptosis response signaling molecules in the intestine of fish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017, 70, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Song, J.; Li, Y.; Luan, Z.; Zhu, K. Diosmectite–zinc oxide composite improves intestinal barrier function, modulates expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and tight junction protein in early weaned pigs. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 110, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Teng, P.Y.; Lee, T.T.; Yu, B. Effects of multi-strain probiotic supplementation on intestinal microbiota, tight junctions, and inflammation in young broiler chickens challenged with Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 33, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, L.; Lv, Y.; Chen, Q.; Feng, J.; Zhao, X. Lactobacillus plantarum Restores Intestinal Permeability Disrupted by Salmonella Infection in Newly-hatched Chicks. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yi, H. Protective Effects of Bacteriocin-Producing Lactiplantibacillus plantarum on Intestinal Barrier of Mice. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, N.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Piao, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J. Pediococcus pentosaceus PP04 improves high-fat diet-induced liver injury by the modulation of gut inflammation and intestinal microbiota in C57BL/6N mice. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 6851–6862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, D.; Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Gao, F.; Duan, H.; Dong, L.; Wang, X.; Wu, C. Pediococcus pentosaceus PR-1 modulates high-fat-died-induced alterations in gut microbiota, inflammation, and lipid metabolism in zebrafish. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1087703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, W. Trefoil Factor Family (TFF) Peptides and their Different Roles in the Mucosal Innate Immune Defense and More: An Update. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 7387–7399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blyth, G. Regulation of Colonic Mucus and Epithelial Cell Barrier Function by Cathelicidin. Doctoral Thesis, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, M.E.V.; Hansson, G.C. Immunological aspects of intestinal mucus and mucins. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarepour, M.; Bhullar, K.; Montero, M.; Ma, C.; Huang, T.; Velcich, A.; Xia, L.; Vallance, B.A. The Mucin Muc2 Limits Pathogen Burdens and Epithelial Barrier Dysfunction during Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Colitis. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 3672–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aamann, L.; Vestergaard, E.M.; Grønbæk, H. Trefoil factors in inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taupin, D.; Podolsky, D.K. Trefoil factors: Initiators of mucosal healing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 721–732, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 819.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wen, C.; Zhou, Y. Dietary supplementation with a silicate clay mineral (palygorskite) alleviates inflammatory responses and intestinal barrier damage in broiler chickens challenged with Escherichia coli. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Li, Z.R.; Green, R.S.; Holzman, I.R.; Lin, J. Butyrate Enhances the Intestinal Barrier by Facilitating Tight Junction Assembly via Activation of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase in Caco-2 Cell Monolayers12. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1619–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, M.H. Chapter 12—Impact of the gut microbiota on the immune system. In Avian Immunology, 3rd ed.; Kaspers, B., Schat, K.A., Göbel, T.W., Eds.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 353–364. [Google Scholar]

- Iacob, S.; Iacob, D.G.; Luminos, L.M. Intestinal Microbiota as a Host Defense Mechanism to Infectious Threats. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Akhtar, M.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Z.; Liang, Y.; Shi, D.; Cheng, R.; Cui, L.; Hu, Y.; Nafady, A.A. Chicken jejunal microbiota improves growth performance by mitigating intestinal inflammation. Microbiome 2022, 10, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, B.B.; Lillehoj, H.S.; Kogut, M.H.; Kim, W.K.; Maurer, J.J.; Pedroso, A.; Lee, M.D.; Collett, S.R.; Johnson, T.J.; Cox, N.A. The chicken gastrointestinal microbiome. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2014, 360, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, T.C.V. Comprehensive Characterization of the Protein Microbial Anti-Inflammatory Molecule (MAM) from the Genus Faecalibacterium Structural, Diversity, and Anti-Inflammatory Implications; Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Carasi, P.; Racedo, S.M.; Jacquot, C.; Elie, A.M.; Serradell, M.L.; Urdaci, M.C. Enterococcus durans EP1 a Promising Anti-inflammatory Probiotic Able to Stimulate sIgA and to Increase Faecalibacterium prausnitzii Abundance. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hays, K.E.; Pfaffinger, J.M.; Ryznar, R. The interplay between gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids, and implications for host health and disease. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2393270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.