Abstract

Concrete is the most widely used construction material worldwide, yet its production and disposal pose significant environmental challenges due to high carbon emissions and limited recyclability. While microbial colonization of concrete is often associated with structural deterioration, recent research has highlighted the potential of microorganisms to contribute positively to concrete recycling and self-healing. In this study, we investigated the bacterial and fungal communities inhabiting urban concrete samples using amplicon-based taxonomic profiling targeting the 16S rRNA gene and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region. Our analyses revealed a diverse assemblage of microbial taxa capable of surviving the extreme physicochemical conditions of concrete. Several taxa were associated with known metabolic functions relevant to concrete degradation, such as acid and sulphate production, as well as biomineralization processes that may support crack repair and surface sealing. These findings suggest that concrete-associated microbiomes may serve as a reservoir of biological functions with potential applications in sustainable construction, including targeted biodegradation for recycling and biogenic mineral formation for structural healing. This work provides a foundation for developing microbial solutions to reduce the environmental footprint of concrete infrastructure.

1. Introduction

Concrete, a ubiquitous and durable composite material composed of cement (primarily tricalcium silicate (3CaO·SiO2), dicalcium silicate (2CaO·SiO2), tricalcium aluminate (3CaO·Al2O3), and tetra-calcium aluminoferrite (4CaO·Al2O3Fe2O3), fine and coarse aggregates, water, and optionally other additives, has played a pivotal role in shaping modern infrastructures due to its versatility, strength, and moldability [1]. Despite its engineering advantages, the environmental impact of concrete production is significant: the production of cement alone accounts for a considerable share of global CO2 emissions and requires the extraction of finite natural resources [2]. These concerns have catalyzed efforts to develop sustainable alternatives, such as the use of low-carbon cementitious materials and recycled aggregates; however, recycling concrete remains a technical and logistical challenge. Demolished structures are typically crushed into smaller particles for reuse as aggregate in low-grade applications, often referred to as downcycling [3,4]. Moreover, contaminants such as embedded steel, wood, and chemical additives complicate processing, reducing the efficiency and quality of recycled concrete [5,6]. New strategies are needed to improve the recyclability and functional reuse of concrete materials. Among the emerging approaches is the use of biological agents to facilitate selective degradation or mineral recovery, offering a potentially more targeted and environmentally friendly solution.

Biological interactions with concrete have traditionally been viewed through the lens of deterioration. Concrete, although largely inert, can support microbial colonization under favorable environmental conditions, including low surface pH, elevated relative humidity (i.e., between 60–98%), long cycles of humidification and drying, freezing and defrosting, high CO2 concentration (e.g., carbonation in urban atmospheres), high salt concentration or high concentration of sulfates and small amounts of acids [7]. The biodeterioration of concrete can occur through various mechanisms, such as production of organic acids (e.g., acetic, lactic, and butyric acid), which can lower the pH levels and initiate the dissolution of minerals within the concrete, contributing to the erosion of the exposed concrete surface, reducing the protective cover depth, increasing concrete porosity and increasing the transport of degrading agents in the structure [8]. For example, sulphur-oxidizing bacteria oxidize H2S to sulphuric acid, leading to accelerated corrosion in concrete-applications such as sewer systems and barn floors [9]. Other microbes secrete enzymes that degrade organic components in the cement paste, exacerbating porosity and structural weakening [10]. Despite this negative impact, the metabolic versatility of these organisms also offers a promising avenue for biotechnological exploitation. Recent interest has shifted toward harnessing microbes not just as agents of degradation, but also as contributors to concrete repair and sustainability. Certain microbial taxa can induce calcium carbonate precipitation, a phenomenon that can be exploited for crack healing and surface sealing [11]. Such “self-healing concrete” technologies rely on microbial metabolism to form new mineral phases that restore structural integrity. However, a detailed understanding of the microbial communities inhabiting concrete and their functional capabilities remains limited.

In this study, we employed amplicon-based taxonomic profiling to investigate the bacterial (16S rRNA gene) and fungal (ITS region) communities associated with concrete samples collected from diverse urban environments. Our goal was to identify resident taxa capable of colonizing urban concrete, therefore providing a shortlist of organisms that may be leveraged as starting points for future biotechnological applications with minimal engineering. By linking community composition with known or putative microbial activities relevant to cement degradation or mineral precipitation, we aim to provide a foundation for the development of sustainable strategies for controlled concrete recycling and biomineralization-based self-healing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Acquisition

To characterize microbial communities associated with concrete in urban environments, seven concrete samples were provided by the City of Vienna (Stadt Wien, MA 39, Austria), collected from various locations in and around the City of Vienna, Austria (Table 1). Samples 1 and 2 had been previously processed by the construction material testing laboratory of the City of Vienna (Stadt Wien, MA 39), including heat-drying, and were stored under dry conditions for more than three months before analysis. Sample 3 was collected from a relatively humid underground parking facility and exhibited early signs of surface deterioration. Samples 4 and 5 were obtained from two exterior demolition sites and were in comparatively good condition. Samples 6 and 7 were collected from two neighboring demolition sites. All samples were handled using sterile tools at the time of collection and were stored at −20 °C until DNA extraction.

Table 1.

Description of the collected concrete samples.

2.2. Metagenomic DNA Extraction

Metagenomic DNA was extracted from seven concrete samples using the DNeasy PowerMax Soil Kit [QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany, Cat. No. 12988-10], which is optimized for isolating microbial DNA from large quantities of material with low microbial biomass. For each sample, a small portion of the original concrete block was aseptically crushed in a sterile environment, and 10 g of the resulting pulverized material was processed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Following extraction, the total DNA was concentrated 100-fold by precipitation with 5 M sodium acetate and 0.7 volumes of isopropanol. The precipitated DNA was then pelleted by centrifugation, washed with 70% ethanol, air-dried, and resuspended in nuclease-free water.

2.3. Library Preparation and Sequencing

To characterize bacterial and fungal communities, unsaturated PCR amplification of 16S and ITS rDNA fragments was performed using the Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase [New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA, Cat. No. M0491], which provides ultra-low amplification error rates. For bacteria, the V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was targeted using primers 341F (5′-CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACNNGGGTATCTAAT-3′) [12]. For fungi, the ITS1 region was amplified using primers ITS5-1737F (5′-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3′) and ITS2-2043R (5′-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3′) [12]. PCRs were performed in 50 µL reactions using 1 µL of template DNA (~0.5 ng total DNA per reaction). Thermal cycling conditions were 98 °C for 30 s, followed by 25 cycles of 98 °C for 8 s, 57 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 15 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 2 min. For each sample, PCRs were performed in four replicate 50 µL reactions, which were pooled prior to purification and library preparation. All PCR reactions included a no-template control using nuclease-free water and reagents from the DNeasy PowerMax Soil Kit and DNA precipitation steps, which yielded no detectable amplification, confirming the absence of contamination. Amplicons were purified using the GeneJET Gel Extraction Kit [Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, Cat. No. K0691] prior to library preparation. Libraries were constructed using the NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina [New England Biolabs, Cat. No. E7645] following the manufacturer’s instructions. Indexed libraries were multiplexed and sequenced in-house on an Illumina MiSeq system using a MiSeq v2 300-cycle flow cell [Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA, Cat. No. MS-102-2002], generating single-end 300 bp reads (Table 2).

Table 2.

16S/ITS amplicon sequencing statistics.

2.4. Microbial Community Composition Analysis

Following sequencing, the quality of raw 16S and ITS amplicon reads was assessed using FastQC (v0.11.9) [13]. Sequencing adapters and low-quality reads were trimmed and removed using Cutadapt (v5.2) [14]. Amplicon sequence data were processed using the DADA2 pipeline (v1.26.0) [15] in R (v4.5.0), which performs quality filtering, dereplication, sample-specific error modelling, inference of amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), and chimera removal (Table 2). Taxonomic assignment was conducted using the SILVA reference database (release 138.2) [16] for bacterial 16S rRNA sequences and the UNITE database (version 10) [17] for fungal ITS sequences, and structured using the phyloseq package (v1.52.0) [18]. Prior to diversity analyses, ASV tables were transformed to relative abundances to account for unequal sequencing depth. Alpha-diversity metrics were computed in phyloseq, and beta diversity was assessed using Bray–Curtis dissimilarities and NMDS ordination.

2.5. Concrete Sample Preparation and Analysis of Physicochemical Properties

Concrete samples were crushed to 4 mm grains using a BB200 heavy-metal free Jaw crusher [Retsch, Haan, Germany, Cat. No. 20.059.0001] and then further milled to a grain size of less than <100 µm with a vibrating-disc mill [Fritsch, Idar-Oberstein, Germany, Cat. No. 09.5000.00]. The pH of concrete leachate was measured for both grain sizes. Crushed or milled concrete was properly mixed, triplicate samples of 5 g were taken using the quartering sampling method [19], and dissolved in 50 mL of tap water. Samples were kept on a wave platform shaker set to 100 rpm, and pH was recorded at 30 min, 90 min, and 72 h. The elemental composition was analyzed with the NitonTM XL3t X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) Analyzer [Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, Cat. No. 10131166] using the milled concrete samples.

2.6. Multivariate Analysis of Microbial Community Composition and Concrete Chemistry

Bacterial and fungal communities were analyzed together to explore associations between microbial composition and the chemical properties of concrete. Amplicon sequence variant (ASV) count tables and associated sample metadata were imported into R (v4.5.0) and structured using the phyloseq package (v1.52.0) [18]. Ordination was performed using non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) implemented with the vegan package (v2.7-1) to visualize variation in community structure [20]. Family-level counts were converted to relative abundances using decostand(method = “total”), and Bray–Curtis dissimilarities were calculated prior to NMDS using metaMDS(). Environmental variables describing elemental composition were standardized (z-transformed) and fitted to the ordination using the envfit() function. Because the number of possible permutations exceeded the requested number, envfit() performed a free permutation test by generating the full set of permutations available for the dataset (5039 total). Vector direction and length represent the orientation and strength (r2) of correlations between individual variables and the NMDS configuration.

3. Results

3.1. Bacterial Community Composition

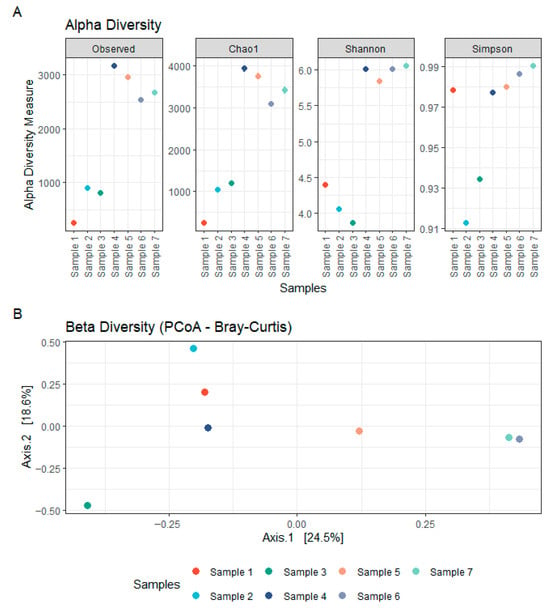

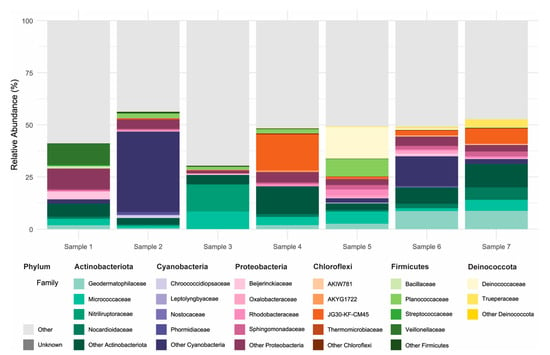

The bacterial communities present in the concrete samples were highly diverse and exhibited marked variation across sites. Alpha diversity estimates based on observed richness and the Chao1 index were higher in samples 4–7 than in samples 1–3, indicating a greater species richness in these communities (Figure 1). Shannon and Simpson indices showed a similar trend, reflecting the richness and evenness of the community compositions, suggesting a more diverse and balanced distribution of taxa in samples 4–7. Samples 1–2 were heat-dried and stored prior to processing, whereas samples 3–7 were processed fresh. Despite lower alpha-diversity in samples 1–2 (and partially sample 3) relative to samples 4–7, taxonomic profiles remained broadly overlapping across samples (Supplementary Table S1), including several genera detected in all samples; the potential influence of heat-drying and storage is discussed below. Taxonomic profiling of the 16S rRNA gene sequences revealed a broad range of bacterial phyla, with the most prominent lineages including Actinobacteriota, Cyanobacteria, Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi, Firmicutes, and Deinococcota (Figure 2). Actinobacteriota comprised between 5.4% and 31.0% of the total classified reads and were consistently among the dominant phyla across all samples (Supplementary Table S1). Within this group, the orders Micrococcales (2.0–11.8%) and Frankiales (0.1–14.4%) were especially abundant. These were primarily represented by the families Micrococcaceae (1.1–8.3%), Microbacteriaceae (0.006–3.7%), Intrasporangiaceae (0.06–4.6%), and Geodermatophilaceae (0.005–8.9%). Cyanobacteria were highly variable across samples, accounting for as little as 0.005% and up to 40.9% of the total reads. Most cyanobacterial reads were classified as Chloroplasts (0.003–38.0%), with smaller fractions assigned to Cyanobacteriales (up to 2.9%). Proteobacteria, another major phylum observed in all samples, ranged from 2.3% to 14.6% of the bacterial community. The most represented classes were Alphaproteobacteria (0.9–7.1%) and Gammaproteobacteria (0.3–2.8%). Other phyla, such as Chloroflexi (0.2–18.7%), Firmicutes (0.01–12.1%), and Deinococcota (0.001–15.4%), were also consistently detected, although their relative abundance varied widely between samples. Additional minor taxa included Patescibacteria, Bacteroidota, Acidobacteriota, Fusobacteriota, Verrucomicrobiota, Gemmatimonadota, Crenarchaeota, Planctomycetota, Sumerlaeota, Myxococcota, and Bdellovibrionota, each contributing less than 5% of the community in most samples. Remarkably, a large proportion of the detected amplicon sequence variants (42.2–68.4%) could not be confidently assigned to known taxonomic groups, suggesting the presence of uncharacterized or poorly represented taxa in reference databases. These findings underscore the phylogenetic complexity of microbial communities inhabiting concrete structures and point toward a substantial fraction of potentially novel or uncultured bacteria within this environment.

Figure 1.

Bacterial diversity within concrete samples. (A) Alpha diversity of bacterial communities in concrete, assessed using Observed, Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson indices based on 16S rDNA sequencing. (B) Beta diversity of bacterial communities in concrete, visualized using Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis distances from 16S rDNA sequencing data.

Figure 2.

Taxonomic composition of bacterial communities in concrete samples. Relative abundance (%) of bacterial ASVs based on 16S rDNA sequencing, shown at the family level for the six most abundant phyla: Actinobacteriota, Cyanobacteria, Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi, Firmicutes, and Deinococcota. For each phylum, the four most abundant families are displayed individually; remaining families within the same phylum are grouped as “Other [Phylum]”. Taxa from less abundant phyla are grouped under “Other”, and ASVs not assigned to a known phylum are labeled as “Unknown”.

3.2. Fungal Community Composition

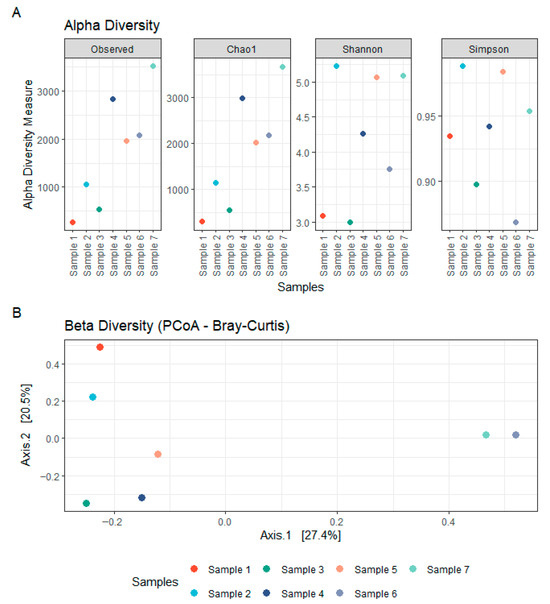

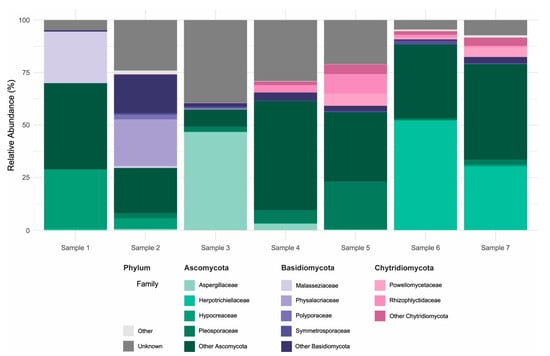

The fungal communities associated with the concrete samples exhibited high variability in both composition and diversity across sites. Alpha diversity estimates, based on Observed richness, as well as Chao1, Shannon and Simpson indices, revealed substantial fluctuations among samples, indicating marked differences in fungal richness and evenness (Figure 3). Samples 1–2 were heat-dried and stored prior to processing, wheras samples 3–7 were processed fresh. Despite lower alpha-diversity in samples 1–2, and partly sample 3), ITS taxonomic profiles showed broad overlap across samples (Supplementary Table S2), including seven genera detected in all samples; potential effects of heat-drying and storage are addressed in the discussion. Taxonomic classification of the ITS sequences identified a broad range of fungal phyla, with the dominant groups being Ascomycota (29.7–88.3% of classified reads) and Basidiomycota (2.4–44.4%), followed by lower-abundance lineages including Chytridiomycota (0.001–19.8%), Rozellomycota (0.000–1.5%), Blastocladiomycota (up to 0.7%), and Monoblepharomycota (up to 0.4%) (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S2). Other phyla collectively contributed less than 0.05% of the classified reads. Notably, a substantial fraction of ASVs (4.5–39.5%) could not be confidently assigned to known taxa, suggesting the presence of potentially novel or poorly characterized fungal lineages. Within the Ascomycota, the class Sordariomycetes was particularly well represented, accounting for 4.0–40.2% of total reads. This was largely due to high relative abundances of the genera Trichoderma (0.015–28.3%, family Hypocreaceae) and Fusarium (0.03–11.9%, family Nectriaceae). Eurotiomycetes also constituted a significant portion of the community in several samples (0.7–57.7%), primarily driven by members of the genus Exophiala (0.008–52.2%, family Herpotrichiellaceae), which emerged as the most abundant genus overall. Additional contributions within this class came from Penicillium (0.000–28.7%) and Aspergillus (0.000–18.0%), both belonging to the Aspergillaceae family. Among the Basidiomycota, the families Malasseziaceae (0.001–24.6%) and Physalacriaceae (up to 22.1%) were the most frequently detected. In particular, the presence of Malassezia, a genus typically associated with skin and other moist environments, highlights the ability of some members of this phylum to colonize and persist in unconventional substrates such as concrete. Other noteworthy phyla included Chytridiomycota, in which the orders Spizellomycetales (up to 8.3%) and Rhizophlyctidales (up to 9.4%) were most prominent. Although often considered aquatic or soil-associated, their detection in concrete suggests the presence of microhabitats that may support their growth and persistence. Together, these findings highlight the remarkable phylogenetic breadth of fungi colonizing concrete structures and point to both cosmopolitan taxa and site-specific specialists potentially adapted to the harsh physicochemical conditions of this niche.

Figure 3.

Fungal diversity within concrete samples. (A) Alpha diversity of fungal communities in concrete, assessed using Observed, Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson indices based on rDNA ITS sequencing. (B) Beta diversity of fungal communities in concrete, visualized using Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis distances from rDNA ITS sequencing data.

Figure 4.

Taxonomic composition of fungal communities in concrete samples. Relative abundance (%) of fungal ASVs based on rDNA ITS sequencing, shown at the family level for the three most abundant phyla: Ascomycota, Basidiomycota and Chytridiomycota. For each phylum, the four most abundant families are displayed individually; remaining families within the same phylum are grouped as “Other [Phylum]”. Taxa from less abundant phyla are grouped under “Other”, and ASVs not assigned to a known phylum are labeled as “Unknown”.

3.3. Concrete Physicochemical Composition and Its Relation to Microbial Communities

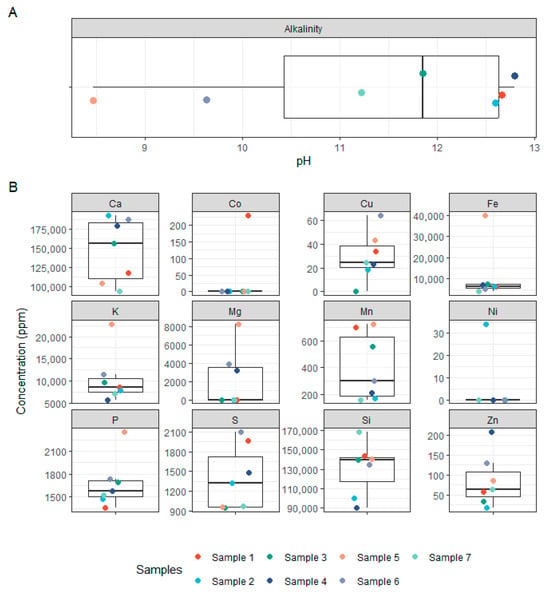

The physicochemical analysis of the seven concrete samples revealed substantial variability across samples in both pH and elemental composition. Most samples exhibited highly alkaline pH values, ranging from 11.73 to 12.80, consistent with the expected chemical environment of concrete (Figure 5). However, two samples (5 and 6) showed markedly lower pH values of 8.47 and 9.63, respectively, suggesting potential aging or environmental exposure effects. Calcium (Ca), a major component of cementitious materials, was present in high concentrations across all samples (93,000 to 192,000 ppm), with no clear pattern across pH gradients (Figure 5). Silicon (Si) was similarly abundant (90,000 to 168,000 ppm), aligning with the mineral matrix of concrete. Other key elements such as potassium (K), iron (Fe), phosphorus (P), and sulphur (S) also showed marked variation across samples. Notably, Fe ranged from 4000 to 40,000 ppm, while K concentrations peaked at 23,000 ppm in sample 5. Magnesium (Mg) was below the limit of detection (LOD) in most samples except 4–6, where it reached up to 8000 ppm. Transition metals such as copper (Cu), manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), cobalt (Co), and nickel (Ni) were present in variable and often trace amounts. Cobalt was detected only in sample 1 (230 ppm), and nickel only in sample 2 (34 ppm), while other samples were below LOD. Zinc concentrations were highest in sample 4 (208 ppm), with the other samples ranging from ~17 to 130 ppm. Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S3 provide a complete overview of all measured elements. Pairwise correlations between element abundances are displayed in the triangular correlation matrix in Supplementary Figure S2. Despite the observed chemical heterogeneity, no significant correlation was found between the concrete composition and the structure of bacterial or fungal communities, as assessed using multivariate statistical approaches (NMDS stress = 7.19 × 10−5; see Supplementary Figure S3 and Supplementary Table S4). This is likely due to the limited number of samples and the high variability in physicochemical profiles. Instead, beta-diversity analyses (Figure 1B and Figure 3B) indicated that microbial community similarity more closely reflected the geographical proximity of the sampling sites, suggesting that environmental factors and local dispersal patterns, such as spore availability, played a stronger role in shaping microbial communities than the concrete’s chemical environment.

Figure 5.

Physicochemical properties of concrete samples. (A) Boxplot showing the pH values of the concrete samples. (B) Boxplots of elemental concentrations (ppm) for selected major and trace elements measured in concrete samples, including Ca, Si, Fe, K, P, S, Mg, Cu, Zn, Mn, Co, and Ni.

4. Discussion

We used 16S rRNA gene and ITS amplicon sequencing to profile bacterial and fungal communities across seven urban concrete samples, with the aim of identifying resident taxa already capable of colonizing and persisting in concrete, and thus potential candidates for applications that leverage intrinsic adaptation and require minimal engineering, such as biogenic crack sealing via biomineralization or controlled microbially mediated degradation for recycling. Two samples (Samples 1–2) were heat-dried and stored prior to acquisition, whereas Samples 3–7 were processed fresh. DNA yields from the heat-dried samples were comparable to those from fresh concrete, but alpha-diversity was lower in Samples 1–2 for both 16S and ITS profiles, consistent with the possibility that drying/storage and/or other sample-specific factors reduce detectable richness and evenness. A plausible explanation is partial DNA degradation during drying and long-term storage, which may disproportionately affect the detection of low-abundance taxa. Despite this, community composition remained broadly comparable across sample types: Supplemental Tables S1 and S2 show substantial overlap of classified taxa across all samples, including several genera detected in all seven samples (16S: Blastococcus, Nocardioides, Marmoricola, Pseudonocardia, Sphingomonas, Paracoccus, TM7a; ITS: Trichoderma, Fusarium, Botryotrichum, Exophiala, Alternaria, Cladosporium, Malassezia), alongside sample-specific enrichments present in both heat-dried and fresh concrete. Notably, many of these recurrent genera have been linked in the literature to concrete-relevant processes.

Concrete deterioration by acid attack primarily involves acidolysis, in which hydration products in the matrix react with infiltrating organic acids, leading to ion release and loss of solid mass [21]. This is followed by complexolysis, where the resulting acid ions form complexes with metal ions released during acidolysis. This facilitates further dissolution of the solid phase, while the precipitation of expansive reaction products may cause cracking. Among the tested acids, citric, succinic, and acetic acid have been reported as the most aggressive agents of concrete degradation [22]. However, the stability of original cement components and the extent of their recovery post-acid exposure remain unclear. While many heterotrophic bacteria (e.g., Vibrio, Acidobacteria, Bacillus) are known to produce organic acids that can induce decalcification of cement hydration products, none were detected at significant levels in our samples. Autotrophic bacteria such as Nitrosomonas, Nitrobacter (nitrifiers), and sulphur-oxidizers like Thiobacillus, Thiothrix, Thiomicrospira, and Beggiatoa produce inorganic acids, which are typically more corrosive than their organic counterparts. Previous studies have identified Thiobacillus, Acidothiobacillus, and Thiomonas as dominant taxa in corroded concrete sewer pipes [7,23], yet these were also not present at notable levels in our dataset. In contrast, fungi capable of producing organic acids were well represented. We identified six fungal genera previously associated with concrete biodeterioration (Exophiala, Trichoderma, Alternaria, Penicillium, Aspergillus, and Fusarium) at high relative abundances. Notably, Fusarium species have been implicated in the deterioration of concrete bridges along the Nile River [21], highlighting their potential role in structural degradation.

Microbial taxa identified in this study have also been explored for their self-healing potential, particularly through biologically induced mineralization. Among bacteria, species within the genus Bacillus, notably Bacillus sphaericus and Bacillus pasteurii, have garnered significant attention. These bacteria can induce calcium carbonate precipitation via ureolysis, where the enzymatic hydrolysis of urea results in the production of ammonium and carbonate ions [24]. In the presence of calcium ions, this leads to the formation of calcite, which can seal microcracks in concrete [25,26]. Other metabolic pathways used for biomineralization include denitrification and sulphate reduction, both of which also result in alkaline conditions favorable to calcium carbonate precipitation [27,28]. Interestingly, some fungal taxa may offer similar capabilities: Aspergillus nidulans, Trichoderma reesei, Neurospora crassa and other filamentous fungi have demonstrated the ability to precipitate calcium carbonate through organic acid-mediated dissolution and reprecipitation cycles, as well as through CO2 production during respiration [29,30,31]. The resulting alkalinity in localized microenvironments can support mineral precipitation. Furthermore, the hyphal structure of fungi may facilitate crack infiltration, increasing their utility in healing deeper or more extensive damage compared to bacterial systems. However, empirical evidence for the use of fungi in concrete self-healing remains limited, with most studies conducted at laboratory scale [32]. These mechanisms are primarily relevant for serviceability-scale microcracks where water ingress can occur. Autogenous healing is generally limited to cracks < 0.2 mm, whereas microbe-enabled mineralization approaches have been reported to extend healing into the sub-millimeter range [33,34,35]. Microbial activity is most likely to contribute under intermittent wetting that provides water for transport and activation, access to oxygen, and sufficient Ca2+/carbonate availability in the alkaline matrix to support CaCO3 precipitation. From an engineering perspective, these microbe–concrete interactions are most likely to affect performance by altering permeability and ion transport within the near-surface zone and crack network. Acid-driven decalcification and persistent biofilms may increase porosity and accelerate ingress of aggressive agents, whereas biomineralization-driven CaCO3 precipitation may reduce permeability and slow such ingress under serviceability conditions, potentially supporting longer-term durability even when complete crack closure is not achieved. The potential contributions of dominant fungal and bacterial genera to concrete healing or deterioration, together with their proposed mechanisms, are outlined in Table 3.

Table 3.

Functional inference of the most abundant fungal and bacterial genera.

Engineering such microbial systems for self-healing applications involves several considerations. For bacteria, researchers have developed encapsulation techniques (e.g., lightweight aggregates, hydrogel beads, or silica microcapsules) to preserve viability and trigger calcite formation upon crack exposure. For fungi, similar strategies are being explored, but their larger size and different environmental requirements pose engineering challenges. Advances in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering may eventually allow the optimization of metabolic fluxes for improved mineralization efficiency and environmental adaptability. The microbial communities detected in our study, particularly the diverse fungal phyla, present an untapped reservoir of metabolic capabilities with implications for both concrete degradation and healing. However, further functional characterization of these taxa is needed to understand their precise roles in concrete–microbe interactions. A key future direction is to distinguish microbial taxa based on their functional outputs rather than just taxonomic identity. For instance, strains that efficiently secrete strong organic acids may be desirable in applications focused on controlled concrete degradation, such as biorecycling of demolition waste. Conversely, strains capable of biomineralization and structural repair should be prioritized for applications in infrastructure maintenance and sustainability. This duality also highlights the need for application-specific microbial engineering. For degradation purposes, communities could be selected or engineered for high acid production, low pH tolerance, and enzymatic activity targeting the cement matrix. For healing, strains might be selected for high urease activity, resilience in alkaline environments, and efficient calcium carbonate precipitation. Moreover, the high proportion of unclassified sequences in our dataset underscores a gap in our current understanding of microbial biodiversity in built environments. There is a clear need for expanded reference databases and experimental work, including isolation, culturing, and genome sequencing, to uncover the full functional potential of these microbes.

A key limitation of this study is the modest sample size, which constrains statistical power and limits the extent to which our observations can be generalized across the diversity of real structural concrete. Urban concrete varies widely in mix design and material properties (e.g., cement type and content, aggregates, supplementary cementitious materials, admixtures, porosity, and age), and these factors can shape microbial colonization by altering pH, moisture retention, and nutrient availability. In addition, exposure histories differ substantially among structures, including wet–dry cycling, de-icing salts and other ions, air pollution, temperature fluctuations, and UV exposure, each of which may select for different microbial assemblages. Our dataset, therefore, represents a snapshot of urban concrete microbiomes rather than a comprehensive survey across concrete types and exposure regimes. Future studies should use larger, stratified cohorts spanning defined concrete classes and controlled exposure metadata, ideally coupled with standardized fresh sampling and functional assays, to link community shifts to specific material and environmental drivers. Importantly, the functional roles discussed are inferred from amplicon-based taxonomic assignments and published literature on related taxa and were not experimentally validated in this study.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that urban concrete supports diverse bacterial and fungal communities that tolerate its extreme environmental conditions. Although elemental composition did not significantly explain community variation, taxonomic profiling revealed a set of recurrent concrete-associated taxa, providing a shortlist of organisms that may be leveraged as minimally engineered starting points for concrete biotechnology. Several detected taxa are linked in the literature to processes relevant to both concrete deterioration and healing. Acid-producing and sulphate-oxidizing microorganisms may contribute to deterioration, while biomineralizing bacteria and filamentous fungi offer promising avenues for self-healing through calcium carbonate precipitation and crack infiltration. Concrete-associated microbiomes, therefore, represent an underexplored reservoir of functions with potential applications in sustainable construction. Future work should prioritize functional characterization through cultivation, genome-resolved analyses, and controlled assays to identify strains suitable for biodegradation or biogenic mineral formation. Improved taxonomic resolution, particularly for fungi, will further refine our understanding of these interactions. Harnessing microbial capabilities may ultimately support low-impact recycling strategies and the development of self-healing concrete materials, thereby reducing the environmental footprint of built infrastructure.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/microorganisms14010131/s1, Figure S1: Physicochemical properties of concrete samples (extended); Figure S2: Correlation matrix of elemental concentrations in concrete samples; Figure S3: Fitted environmental vectors on the NMDS ordination of microbial communities; Table S1: Detailed 16S Community Composition; Table S2: Detailed ITS Community Composition; Table S3: Detailed Concrete Composition Analysis; Table S4: Detailed NMDS Statistics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.M.-A., C.D. and J.C.; methodology, C.D. and J.C.; formal analysis, C.D. and J.C.; investigation, C.D., J.C., C.B. and P.A.; resources, A.R.M.-A.; data curation, C.D. and J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.D. and J.C.; writing—review and editing, A.R.M.-A., R.L.M. and J.L.; visualization, J.C.; supervision, A.R.M.-A.; project administration, A.R.M.-A.; funding acquisition, A.R.M.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The financial support from an internal pre-feasibility study aiming at novel “CO2 Utilization Methods” is gratefully acknowledged. The given funding aims to support future “Direct Air Capture” activities led by Josef Fuchs and Stefan Müller (TU Wien).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in [NCBI] at [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1288356/] (accessed on 2 January 2026), reference number [PRJNA1288356].

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Herbert Kurz (Stadt Wien—MA39) for providing the concrete samples used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASV | Amplicon sequence variant |

| ITS | Internal transcribed spacer |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| MICP | Microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation |

| NMDS | Non-metric multidimensional scaling |

| rRNA | Ribosomal RNA |

| XRF | X-Ray fluorescence |

References

- Jahren, P.; Sui, T. History of Concrete; World Scientific Publishing Company: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad, N.; Muthusamy, K.; Embong, R.; Kusbiantoro, A.; Hashim, M.H. Environmental impact of cement production and Solutions: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 48, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade Salgado, F.; de Andrade Silva, F. Recycled aggregates from construction and demolition waste towards an application on structural concrete: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 52, 104452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Huang, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Ni, W. Research Progress of Low-Carbon Cementitious Materials Based on Synergistic Industrial Wastes. Energies 2023, 16, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badraddin, A.K.; Rahman, R.A.; Almutairi, S.; Esa, M. Main Challenges to Concrete Recycling in Practice. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, C.-S.; Chan, D. Effects of contaminants on the properties of concrete paving blocks prepared with recycled concrete aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2007, 21, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.P.; Jiang, Z.L.; Liu, H.; Zhou, D.S.; Sanchez-Silva, M. Microbiologically induced deterioration of concrete—A Review. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2013, 44, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Silva, M.; Rosowsky, D.V. Biodeterioration of Construction Materials: State of the Art and Future Challenges. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2008, 20, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, S.; Odagiri, M.; Ito, T.; Satoh, H. Succession of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria in the microbial community on corroding concrete in sewer systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Pettitt, T.R.; Buenfeld, N.; Smith, S.R. A critical review of the physiological, ecological, physical and chemical factors influencing the microbial degradation of concrete by fungi. Build. Environ. 2022, 214, 108925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Singh, V.; Arora, A. Microbial Concrete-a Sustainable Solution for Concrete Construction. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 194, 1401–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janusz, G.; Mazur, A.; Pawlik, A.; Kołodyńska, D.; Jaroszewicz, B.; Marzec-Grządziel, A.; Koper, P. Metagenomic Analysis of the Composition of Microbial Consortia Involved in Spruce Degradation over Time in Białowieża Natural Forest. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. Available online: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 2 January 2026).

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J. Silva Taxonomic Training Data Formatted for DADA2 (Silva Version 138.2). Zenodo. 2024. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/14169026 (accessed on 2 January 2026).

- Abarenkov, K.; Zirk, A.; Piirmann, T.; Pöhönen, R.; Ivanov, F.; Nilsson, R.H.; Kõljalg, U. UNITE General FASTA Release for Fungi. UNITE Community. 2025. Available online: https://doi.plutof.ut.ee/doi/10.15156/BIO/3301229 (accessed on 2 January 2026).

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, R.W.; Dobb, D.E.; Raab, G.A.; Nocerino, J.M. Gy sampling theory in environmental studies. 1. Assessing soil splitting protocols. J. Chemom. 2002, 16, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.; Blanchet, F.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.; O’Hara, R.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. 2025. Available online: https://vegandevs.github.io/vegan/ (accessed on 2 January 2026).

- Gaylarde, C.C.; Ortega-Morales, B.O. Biodeterioration and Chemical Corrosion of Concrete in the Marine Environment: Too Complex for Prediction. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ninan, C.M.; Ajay, A.; Ramaswamy, K.P.; Thomas, A.V.; Bertron, A. A critical review on the effect of organic acids on cement-based materials. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 491, 012045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincke, E.; Boon, N.; Verstraete, W. Analysis of the microbial communities on corroded concrete sewer pipes—A case study. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 57, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocks-Fischer, S.; Galinat, J.K.; Bang, S.S. Microbiological precipitation of CaCO3. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1999, 31, 1563–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Muynck, W.; Cox, K.; Belie, N.D.; Verstraete, W. Bacterial carbonate precipitation as an alternative surface treatment for concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2008, 22, 875–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Muynck, W.; Debrouwer, D.; De Belie, N.; Verstraete, W. Bacterial carbonate precipitation improves the durability of cementitious materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2008, 38, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erşan, Y.Ç.; Hernandez-Sanabria, E.; Boon, N.; de Belie, N. Enhanced crack closure performance of microbial mortar through nitrate reduction. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 70, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanier, S.; Métayer-Levrel, G.L.; Perthuisot, J.-P. Bacterial Roles in the Precipitation of Carbonate Minerals. In Microbial Sediments; Riding, R.E., Awramik, S.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, R.R.; Luo, J.; Chen, X.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, N.; Jin, C. Screening of Fungi for Potential Application of Self-Healing Concrete. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Wylick, A.; Vandersanden, S.; Jonckheere, K.; Rahier, H.; De Laet, L.; Peeters, E. Screening fungal strains isolated from a limestone cave on their ability to grow and precipitate CaCO3 in an environment relevant to concrete. MicroPubl. Biol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Csetenyi, L.; Gadd, G.M. Biomineralization of Metal Carbonates by Neurospora crassa. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 14409–14416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wylick, A.; Monclaro, A.V.; Elsacker, E.; Vandelook, S.; Rahier, H.; De Laet, L.; Cannella, D.; Peeters, E. A review on the potential of filamentous fungi for microbial self-healing of concrete. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2021, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvardsen, C. Water permeability and autogenous healing of cracks in concrete. Aci Mater. J. 1999, 96, 448–454. [Google Scholar]

- Amran, M.; Onaizi, A.M.; Fediuk, R.; Vatin, N.I.; Muhammad Rashid, R.S.; Abdelgader, H.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Self-Healing Concrete as a Prospective Construction Material: A Review. Materials 2022, 15, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Khushnood, R.A. Bacterial Carbonate Precipitation Using Active Metabolic Pathway to Repair Mortar Cracks. Materials 2022, 15, 6616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak Babic, M.; Gunde-Cimerman, N. Water-Transmitted Fungi are Involved in Degradation of Concrete Drinking Water Storage Tanks. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prenafeta-Boldú, F.X.; Medina-Armijo, C.; Isola, D. Black fungi in the built environment—The good, the bad, and the ugly. In Viruses, Bacteria and Fungi in the Built Environment; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2022; pp. 65–99. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N.; Khan, H.A.; Khushnood, R.A.; Bhatti, M.F.; Baig, D.I. Self-healing of recycled aggregate fungi concrete using Fusarium oxysporum and Trichoderma longibrachiatum. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 392, 131910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wylick, A.; Rahier, H.; De Laet, L.; Peeters, E. Conditions for CaCO(3) Biomineralization by Trichoderma Reesei with the Perspective of Developing Fungi-Mediated Self-Healing Concrete. Glob. Chall. 2024, 8, 2300160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, X.; Li, M.; Samia, A.; Yu, X. Study on the behaviors of fungi-concrete surface interactions and theoretical assessment of its potentials for durable concrete with fungal-mediated self-healing. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 125870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.D.; Ford, T.E.; Berke, N.S.; Mitchell, R. Biodeterioration of concrete by the fungus Fusarium. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 1998, 41, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomina, M.; Podgorsky, V.S.; Olishevska, S.V.; Kadoshnikov, V.M.; Pisanska, I.R.; Hillier, S.; Gadd, G.M. Fungal Deterioration of Barrier Concrete used in Nuclear Waste Disposal. Geomicrobiol. J. 2007, 24, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannantonio, D.J.; Kurth, J.C.; Kurtis, K.E.; Sobecky, P.A. Molecular characterizations of microbial communities fouling painted and unpainted concrete structures. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2009, 63, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.; Son, Y.; Jang, I.; Yi, C.; Park, W. Managing two simultaneous issues in concrete repair: Healing microcracks and controlling pathogens. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 416, 135125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leplat, J.; Bousta, F.; François, A.; Guiavarc’h, M.; Mertz, J.-D.; Brissaud, D. The pink staircase of Sully-sur-Loire castle: Even bacteria like historic stonework. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2019, 145, 104805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleyen, N.; Hendrix, K.; Moors, H.; Durce, D.; Vasile, M.; Valcke, E. Biodegradability of dissolved organic matter in Boom Clay pore water under nitrate-reducing conditions: Effect of additional C and P sources. Appl. Geochem. 2018, 92, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-M.; Park, S.-J.; Ghim, S.-Y. Characterization of Three Antifungal Calcite-Forming Bacteria, Arthrobacter nicotianae KNUC2100, Bacillus thuringiensis KNUC2103, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia KNUC2106, Derived from the Korean Islands, Dokdo and Their Application on Mortar. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 23, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaheen, N.; Khushnood, R.A.; Memon, S.A.; Adnan, F. Feasibility assessment of newly isolated calcifying bacterial strains in self-healing concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 362, 129662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiledal, E.A.; Keffer, J.L.; Maresca, J.A. Bacterial Communities in Concrete Reflect Its Composite Nature and Change with Weathering. mSystems 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W.; Chen, T.; Liu, G.; Xue, L.; Cui, X. Nocardioides: “Specialists” for Hard-to-Degrade Pollutants in the Environment. Molecules 2023, 28, 7433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jroundi, F.; Fernandez-Vivas, A.; Rodriguez-Navarro, C.; Bedmar, E.J.; Gonzalez-Munoz, M.T. Bioconservation of deteriorated monumental calcarenite stone and identification of bacteria with carbonatogenic activity. Microb. Ecol. 2010, 60, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.