Abstract

Oral candidiasis, mainly from Candida albicans, affects immunocompromised individuals, the elderly, and denture wearers. Probiotics offer immunomodulatory and microbiota-balancing benefits as potential antifungal alternatives. However, the comparative impact of different probiotic delivery methods remains inadequately explored. This systematic review evaluated the effectiveness of various probiotic delivery methods in reducing Candida colonization and clinical symptoms in oral candidiasis. Following PRISMA 2020 guidelines, a systematic review search across multiple databases included human clinical studies based (Medline, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and ProQuest) on PICO criteria across all age groups. Outcomes assessed included Candida load, oral microbiota changes, symptom improvement, and disease recurrence. Of 297 articles screened, 10 met inclusion criteria. Delivery methods investigated included lozenges, capsules, yogurt, and cheese. Most studies reported reductions in Candida colony-forming units (CFUs) or prevalence, mainly for C. albicans and for non-albicans species, with probiotics such as Lactobacillus reuteri, L. rhamnosus, L. acidophilus, and Bifidobacterium strains. Some studies reported improved immunological markers, while symptom relief, especially when probiotics were combined with antifungals. Probiotics reduce Candida colonization and symptoms, with potential prolonged effects. They show promise as adjunctive therapies, but standardized, large-scale trials are needed for optimization.

Keywords:

oral candidiasis; Probiotic; microbiota; delivery methods; fungal infections; efficacy; Candida; antifungal 1. Introduction

Oral candidiasis, primarily attributed to the opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans, is a common fungal infection affecting the oral mucosa, particularly in immunocompromised individuals [1], the elderly [2], denture wearers [3,4,5], and patients undergoing chemotherapy or radiotherapy [6]. Candida albicans is part of the normal microbiota but may become pathogenic under compromised host conditions, contributing to biofilm formation and resistance to antifungal agents [7].

The infection ranges from asymptomatic colonization to overt mucosal lesions, often exacerbated by factors such as xerostomia [8], diabetes [9], poor oral hygiene, and poorly adapted dentures [10,11]. Dentures themselves serve as reservoirs for Candida spp. due to their porous nature and susceptibility to biofilm accumulation [12,13].

While conventional antifungal therapies such as nystatin and azoles remain the standard of care [14,15], their efficacy is often limited by side effects [16,17], and the emergence of drug-resistant Candida strains [18]. Consequently, there is growing interest in alternative and complementary therapies that can modulate the host’s microbiota and immune response with fewer adverse effects [19,20,21].

Probiotics—defined as “live microorganisms which, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host” [22]—have gained attention as supportive or alternative therapies for Candida-associated oral infections. Certain Lactobacillus and Streptococcus strains exhibit antifungal effects through competitive inhibition [23], production of organic acids [24], hydrogen peroxide, and bacteriocin-like substances, which suppress C. albicans growth and biofilm formation [25]. Moreover, probiotics can modulate host immunity by stimulating cytokine release and enhancing macrophage and T-cell activity, thereby improving mucosal defence [26]. These combined antimicrobial and immunomodulatory effects make probiotics a promising adjunctive approach for managing oral candidiasis [21,26].

Probiotic strains such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus, L. acidophilus, L. reuteri, and Streptococcus salivarius K12 have demonstrated antifungal activity in both in vitro [23], and in vivo studies [19,27]. Additionally, specific strains like L. rhamnosus GG and L. reuteri have shown effectiveness when delivered in cheese or lozenge forms [19,28].

While numerous studies indicate that probiotics can help lower oral Candida spp. Levels [20,21,29], there is a lack of comparative research on the effectiveness of different delivery methods [30]. Only a few investigations have directly assessed forms such as lozenges, cheese, yogurt, or capsules in terms of clinical efficacy, patient adherence, and long-term impact [20,21,30]. Delivery method influences probiotic retention time in the oral cavity, patient adherence, and overall therapeutic effectiveness, making it a clinically relevant factor [28]. This underscores the need for a systematic comparison to inform optimal probiotic strategies for managing oral candidiasis.

This systematic review aims to critically assess and compare the effectiveness of various probiotic delivery methods in reducing Candida spp. colonization and clinical symptoms associated with oral candidiasis. By synthesizing evidence from diverse clinical settings and populations, this review seeks to identify the most promising delivery formats and inform future therapeutic strategies for managing this prevalent oral infection.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [31]. The protocol of this systematic review was registered in the PROSPERO database [32] (CRD420251060214).

2.1. Focused Question

The focused question was “How do different probiotic delivery forms influence the effectiveness of probiotics in the treatment of oral candidiasis in human clinical trials?”

2.2. Patients, Interventions, Control, Outcome (PICO)

The study follows the Patient-Intervention-Comparison-Outcome (PICO) framework to ensure a well-defined research question. In this review, the population (P) consists of patients diagnosed with oral candidiasis. The intervention (I) involves the use of different probiotic delivery methods, while the comparison (C) involves different probiotic delivery forms. (It should be noted that not all included studies directly compared delivery methods within the same trial. Comparative analysis was therefore conducted qualitatively across studies). The outcome (O) focuses on the effectiveness in reducing Candida colonization and symptom relief [33].

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria were: (a) studies conducted on participants with either clinically confirmed oral candidiasis or microbiologically confirmed Candida colonization without clinical signs, (b) participants of all age groups including children, adults, and the elderly, (c) inclusion of individuals with or without denture use, (d) clinical studies involving human subjects (e.g., randomized clinical trials), (e) studies in which probiotics were used as the primary intervention, (f) probiotics administered in any form with reported dosage, treatment duration, and method of administration, (g) studies reporting at least one of the following outcomes: reduction in Candida colonization load, changes in oral microbiota balance, reduction in the severity of clinical symptoms, or recurrence rate of the disease during follow up, (h) articles published in English, and (i) no restriction on the year of publication.

Studies were excluded if they met one or more of the following conditions: (a) focused on fungal infections other than oral candidiasis (e.g., vaginal, cutaneous, or systemic candidiasis); (b) did not use probiotics as the primary intervention for treatment; (c) included participants presenting with clinical denture stomatitis; (d) involved individuals with cancer (The exclusion of cancer patients refers to individuals with an active cancer, including those undergoing or who have recently completed chemotherapy or radiotherapy. These conditions substantially alter oral immunity and could introduce heterogeneity in treatment response. Immunocompromised individuals without cancer (e.g., HIV-infected participants) were not excluded. None of the included studies involved participants with cancer.); (e) were published in languages other than English; (f) were of the following study types: in vitro (laboratory) studies, animal studies, systematic reviews or meta-analyses, and studies with incomplete data (e.g., lacking efficacy outcome reports).

2.4. Search Strategy

A comprehensive search was carried out in accordance with PRISMA guidelines, using electronic databases such as Medline, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and ProQuest on 26 February 2025. The search terms included “probiotic,” “microbiota,” “oral candidiasis,” “administration,” and “use,” which were applied in various ways and adapted for each database using appropriate indexing terms and Boolean operators. The search strategies were as follows:

- •

- MEDLINE: (((probiotic[MeSH Terms]) OR (microbiota[MeSH Terms])) AND (oral candidiasis[MeSH Terms])) AND ((administration) OR (use))

- •

- Web of Science Core Collection: (((TS=(Probiotic)) OR TS=(Microbiota)) AND TS=(Oral Candidiasis)) AND (TS=(Use) OR TS=(Administration)), with the “Article” document type filter applied.

- •

- ScienceDirect: ((“probiotic” OR “microbiota”) AND “oral candidiasis” AND (“administration” OR “use”)), with the “Research Articles” filter applied.

- •

- ProQuest: noft(probiotic OR microbiota) AND noft(oral candidiasis) AND noft(administration OR use), using the “Anywhere except full text—NOFT” field and applying the “Scholarly Journals” and “Article” filters.

2.5. Data Extraction and Quality/Risk of Bias Assessment

Study eligibility was assessed independently by two authors based on the title and abstract of the articles. Following this selection, a full-text review of the selected articles was conducted by two authors in order to confirm whether they met the inclusion criteria. In case of disagreements about the selection of studies, decisions were made through discussion with another researcher.

The methodological quality and risk of bias in the included studies were assessed independently by two authors using the JBI critical appraisal checklist [34,35]. Domain-specific judgments (e.g., randomization procedures, allocation concealment, blinding, follow-up completeness, and statistical analysis) were assessed according to the JBI checklist criteria. This study uses Robvis to create plots for JBI critical appraisal checklist [36].

2.6. Synthesis Methods

All included studies fulfilled the quality criteria. Due to heterogeneity in study designs, probiotic strains, and intervention protocols, a meta-analysis was not feasible. Therefore, a narrative synthesis approach was adopted. For this synthesis, studies were grouped and compared qualitatively based on their probiotic delivery method, study characteristics, and outcomes, which are structured in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the included studies.

Table 2.

Population characteristics of the included studies.

Table 3.

Outcome characteristics of probiotic interventions in oral candidiasis.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

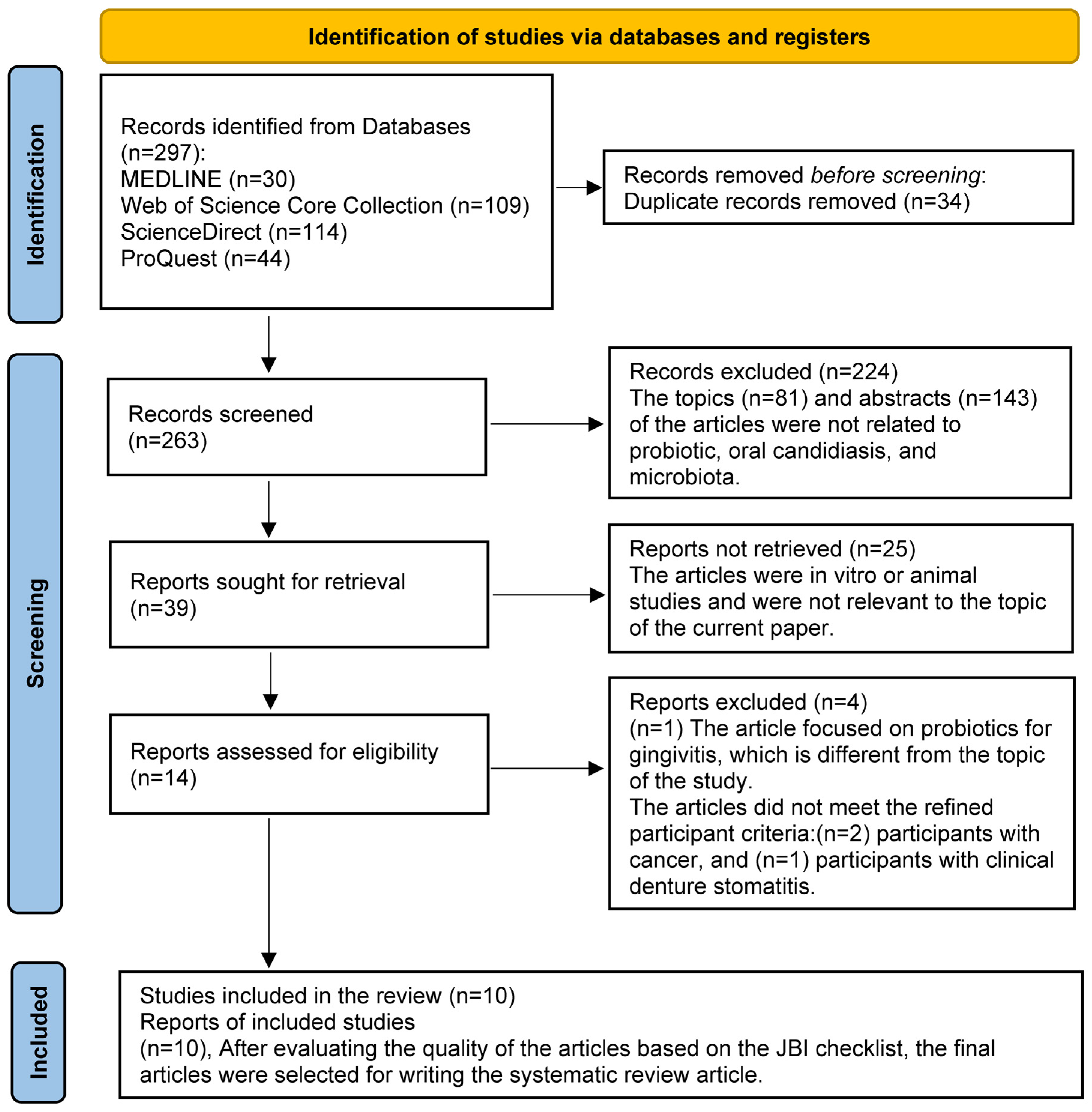

A total of 297 records were initially retrieved through database searches. After removing 34 duplicate entries, 263 unique records remained for screening. Following a two-stage screening process against eligibility criteria, 10 studies met the inclusion criteria and were selected for the final systematic review, based on a quality appraisal using the JBI checklist. The screening process was conducted using Rayyan [42], a web-based tool designed for systematic reviews. Also, no time limit was applied to extracting articles (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews.

3.2. General Characteristics of the Included Studies

All studies were conducted in clinical or hospital-based settings between 2007 and 2024. The studies were reported to be conducted in Brazil, Egypt, Sweden, China, the USA, Turkey, and Finland. The inclusion of studies from these countries was not intentional or geographically restricted; rather, it resulted from the systematic screening process based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles meeting the eligibility criteria were included regardless of their country of origin. Seven of the studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [3,19,20,37,39,40,41], while three were quasi-experimental studies [1,21,38], all involving human subjects. Trial registration numbers for several studies are presented in Table 1.

The mean age of participants varied widely across studies, ranging from young adults to elderly individuals. In most studies, the participants were older adults, often over 60 years of age, reflecting the focus on specific populations such as denture wearers, and frail elderly. The sample sizes of the included studies were highly heterogeneous, ranging from 24 to 276 participants across trials (Table 1).

3.3. Population Characteristics of the Included Studies

The 10 studies exhibited varied inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2). Inclusion criteria often specified oral conditions (e.g., Candida colonization, denture use) [3], specific populations (e.g., elderly, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive women) [1,21,41]. Exclusion criteria frequently involved use of antifungals/antibiotics [38,39], reported of consumption of probiotics [37], lactose intolerance [40], severe systemic diseases [20], and cognitive impairment [41].

3.4. Outcome Characteristics of Probiotic Interventions in Oral Candidiasis

The included studies, detailed in Table 3 for strain composition, CFU counts, and exact administration protocols, evaluated probiotic effectiveness. The findings are summarized below according to delivery method.

3.4.1. Lozenges

Four studies administered probiotics via lozenges [20,37,39,41]. The lozenges contained various strains, such as including 7 Lactobacillus strains and 5 Bifidobacterium strains species [37], 2 L. reuteri strains (DSM 17938 and PTA 5289) [41], and Streptococcus salivarius K12 [39]. Treatment durations ranged from 4 weeks [20,39], 8 weeks [37], and 12 weeks [41], with administration frequencies of once daily [37], twice daily [39,41], or three times daily [20]. Reported outcomes included significant reductions in Candida CFU/mL compared with control groups (p < 0.001) [37] and assessments of clinical symptoms [20].

3.4.2. Capsules

One study used a capsule containing L. rhamnosus HS111, L. acidophilus HS101, and B. bifidum, applied daily to the upper denture for five weeks [3]. The probiotic group showed a significantly lower Candida detection rate (16.7%) than the placebo group (92.0%) (p < 0.0001).

3.4.3. Sachets

Two studies administered probiotics in sachet form, mixed with liquid before intake [21,38]. Treatment durations were 10 days [38] and 30 days [21], with daily [38] or thrice-weekly [21] dosing. Outcomes included reductions in Candida counts and measurement of salivary anti-Candida IgA levels [21].

3.4.4. Probiotic Products

Three studies used probiotic products as delivery vehicles: two probiotic cheeses [19,40] and one probiotic yogurt [1]. Intervention durations were 30 days [1], 8 weeks [40], and 16 weeks [19], with daily consumption. Two studies reported significant reductions in Candida CFU/mL compared with controls [19,40], while one study found potential reductions but noted limitations due to a small sample size [1].

Outcome measurements across all included studies primarily focused on quantification of Candida, typically through culture on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) followed by species identification [1,3,21,37].

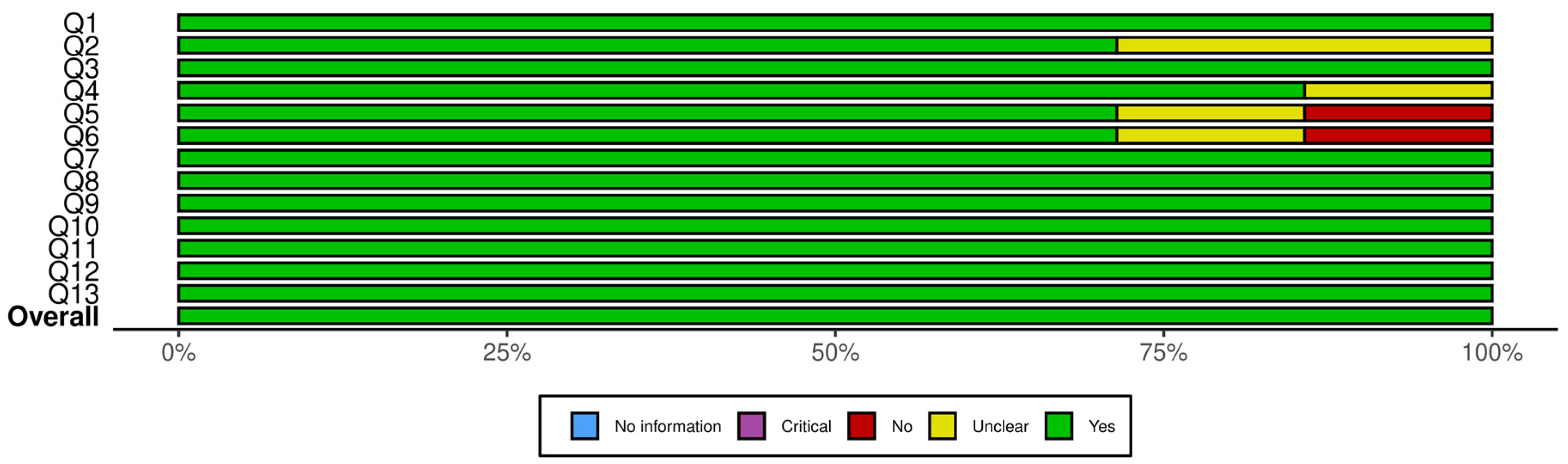

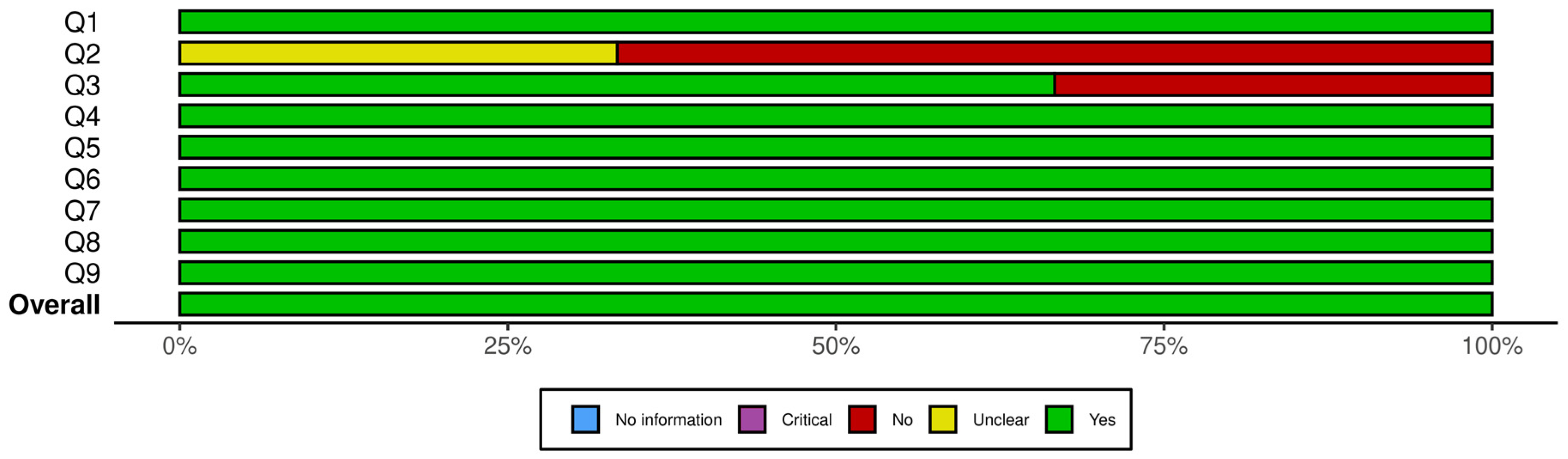

3.5. Quality of the Included Studies

The methodological quality of the 10 included studies was assessed using the relevant JBI critical appraisal tools, selected based on each study’s design. Three studies were evaluated using the JBI Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies [34], while seven studies were assessed using the JBI Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials [35]. In cases of disagreement, a third researcher was consulted to facilitate a consensus-based resolution.

For clinical trials, the quality assessment considered factors such as the adequacy of the randomization process, the representativeness of participant selection, the presence and length of the follow-up period (and any disadvantages associated with short follow-up), and the appropriateness of the control and intervention groups.

Each checklist includes four possible responses: “Yes,” “No,” “Unclear (UC),” and “Not Applicable (N/A).” A higher proportion of “UC” and “N/A” responses suggests either poor reporting or methodological weaknesses. Studies with substantial ambiguity in these areas were considered to be at a higher risk of bias. None of the included studies were excluded following the quality appraisal, as all were considered to meet the minimum methodological standards required for inclusion.

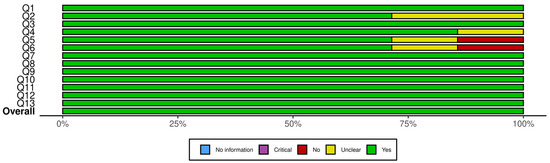

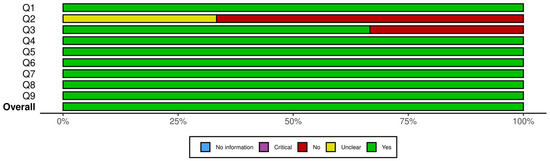

Figure 2 presents a summary plot of the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials, and Figure 3 displays the corresponding plot for the JBI Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies. In these visual summary plots, “No information” is used in place of “N/A.”

Figure 2.

Summary plot for JBI critical appraisal checklist for randomized controlled trials. Q1. Was true randomization used for assignment of participants to treatment groups? Q2. Was allocation to treatment groups concealed? Q3. Were treatment groups similar at the baseline? Q4. Were participants blind to treatment assignment? Q5. Were those delivering treatment blind to treatment assignment? Q6. Were outcomes assessors blind to treatment assignment? Q7. Were treatment groups treated identically other than the intervention of interest? Q8. Was follow up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow up adequately described and analyzed? Q9. Were participants analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized? Q10. Were outcomes measured in the same way for treatment groups? Q11. Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? Q12. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? Q13. Was the trial design appropriate, and any deviations from the standard RCT design (individual randomization, parallel groups) accounted for in the conduct and analysis of the trial?

Figure 3.

Summary plot for JBI checklist for quasi-experimental studies. Q1. Is it clear in the study what is the “cause” and what is the “effect” (i.e., there is no confusion about which variable comes first)? Q2. Was there a control group? Q3. Were participants included in any comparisons similar? Q4. Were the participants included in any comparisons receiving similar treatment/care, other than the exposure or intervention of interest? Q5. Were there multiple measurements of the outcome, both pre and post the intervention/exposure? Q6. Were the outcomes of participants included in any comparisons measured in the same way? Q7. Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? Q8. Was follow-up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow-up adequately described and analyzed? Q9. Was appropriate statistical analysis used?

A closer inspection of the RCTs showed that the highest sources of bias were related to allocation concealment and blinding. Specifically, two trials did not clearly report allocation concealment, and blinding procedures were either unclear or absent in one to two studies for participants, treatment providers, and outcome assessors. All other domains showed consistently strong reporting across the seven RCTs. For the quasi-experimental studies, uncertainty arose from the use and reporting of control groups: two studies did not clearly describe whether a control group existed, and one lacked a control group entirely. Baseline comparability was unclear in one study, but all other methodological domains were well reported. Overall, the areas with the most ambiguity involved blinding in RCTs and control-group structure in quasi-experimental designs. Despite these limitations, none of the studies exhibited risk levels sufficient to warrant exclusion.

A comprehensive summary of the quality appraisal results, including detailed tables, is available in the Supplementary Materials.

3.6. Results Synthesis

4. Discussion

This systematic review investigated how different probiotic delivery forms influence the effectiveness of probiotics in treating oral candidiasis in humans. The 10 included studies used delivery methods that varied substantially, including capsules, lozenges, sachets, yogurt, and cheese. Probiotics, whether used alone or as adjuvants to conventional antifungal therapies, were generally effective in reducing oral Candida colonization.

The importance of probiotic delivery systems in oral health has received increasing attention, as probiotic efficacy depends not only on strain selection but also on the ability of the microorganisms to remain viable, and exert localized effects, although such mechanisms were not directly evaluated in the included studies. The delivery method is likely to influence probiotic performance; however, none of the included studies directly measured mucosal retention, survival, or adhesion, so these mechanisms remain theoretical and based on broader probiotic literature. Formulations that potentially prolong contact with the oral mucosa, such as lozenges, may provide enhanced local exposure. These mechanisms are theoretically relevant in the management of oral candidiasis, where sustained mucosal presence is essential to disrupt Candida biofilms and restore microbial balance. Additionally, the use of indigenous oral strains may enhance colonization efficiency and therapeutic efficacy, underscoring the importance of optimizing both the microbial composition and the delivery vehicle of oral probiotic products [43].

Lozenges were among the most consistently effective delivery forms [20,37,39,41]. Their mode of administration may provide longer oral exposure, which could contribute to clinical effects, although this was not measured in the included trials. In several studies, lozenges containing strains such as Lactobacillus reuteri [41], Streptococcus salivarius K12 [39], and mixed Lactobacillus-Bifidobacterium formulations [37] reduced Candida counts and, in some cases, shortened treatment durations when used as adjuncts to antifungal agents [39]. Slow dissolution may plausibly increase oral exposure time, but interaction with mucosal biofilms was not assessed in the included studies.

Capsule-based probiotics, when opened and applied directly to dentures or mucosal surfaces, have demonstrated significant efficacy in reducing oral Candida colonization in asymptomatic elderly denture wearers. This targeted application, involving the placement of the probiotic formulation on the maxillary denture in close contact with the palatal mucosa, may enhance localized probiotic activity and promote effective colonization at the mucosa-prosthesis interface [3].

Sachets dissolved in liquids showed significant antifungal and antimicrobial effectiveness, consistent with clinical findings demonstrating reduced microbial counts in oral regions and denture surfaces after probiotic intake. Their use also appeared to stimulate mucosal immune function, with studies reporting an increase in salivary anti-Candida IgA levels in elderly individuals, indicating enhanced secretory immune response and reinforcing their potential role in the management of oral candidiasis [21,38]. These findings suggest potential immunomodulatory effects, although causality cannot be established from the available evidence.

Probiotic products such as yogurt and cheese offered variable results. While two of the studies reported significant reductions in Candida colonization, another noted more limited or inconsistent effects. These variable outcomes may be partially related to limited oral contact inherent to food-based products, although this was not assessed in the included studies. Probiotic products, although easy to administer, may be less suitable for patients requiring sustained mucosal exposure to probiotics [1,19,40]. Nonetheless, probiotic dairy products may still play a supportive role, particularly in improving general microbial balance and contributing to immune modulation [44].

However, recent literature highlights that, although their mucosal contact is limited, fermented dairy products remain effective systemic probiotic carriers due to their capacity to maintain microbial viability during storage and gastrointestinal transit. Technological advances, such as microencapsulation and the use of exopolysaccharide-producing strains, have further enhanced the stability and functional efficacy of these products. Combined with broad consumer acceptance, these advances suggest that dairy matrices may function effectively as delivery vehicles, though the present review did not assess systemic outcomes, and such interpretations fall outside its scope [45].

5. Limitations

This review has some limitations. The included studies varied in design, participant characteristics, probiotic strains, dosage, sample sizes, and intervention duration. Candida quantification methods were not standardized across studies, and follow-up durations were often short, reducing the ability to assess long-term effects or recurrence. Although no geographic restrictions were applied during study selection, the distribution of available studies was uneven across regions, which may influence the generalizability of the findings.

Another limitation is that none of the included studies directly compared different probiotic delivery forms within the same trial, preventing definitive conclusions regarding the relative effectiveness of the various delivery systems.

The decision to exclude studies involving participants with active cancer was made because cancer therapies substantially alter oral immunity and could introduce clinically incomparable and heterogeneous treatment responses. While this criterion ensured greater homogeneity among the included populations, it also means that the findings primarily apply to non-cancer populations.

6. Conclusions

This systematic review suggests that probiotic delivery form may influence clinical outcomes in oral candidiasis; however, the available evidence remains limited and heterogeneous. Several studies reported favorable effects, particularly with delivery forms that potentially increase oral contact time, such as lozenges or formulations applied to dentures.

At the same time, orally ingested carriers such as dairy-based products also demonstrate promising findings. While their oral contact time is short, they remain practical options, especially when ease of use or integration into daily habits is important. However, evidence regarding systemic benefits or gut–oral interactions was beyond the scope of the included studies and requires further investigation.

Overall, current evidence supports the potential role of probiotics as adjunctive or preventive interventions for reducing Candida burden, but conclusions regarding the relative effectiveness of specific delivery methods remain preliminary. The small number of trials, variation in probiotic strains and dosages, and differences in Candida quantification methods limit the strength of comparative interpretations.

Future research should include well-designed, adequately powered randomized controlled trials that: directly compare different delivery vehicles under standardized conditions; use consistent probiotic strains or provide detailed strain-level reporting; apply uniform and validated Candida quantification methods; and incorporate longer follow-up periods to evaluate persistence of effects and recurrence.

In conclusion, while probiotic delivery form may influence therapeutic outcomes in oral candidiasis, stronger and more standardized clinical evidence is required before definitive recommendations can be made.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/microorganisms13122883/s1, Table S1: JBI critical appraisal checklist for randomized controlled trials. Table S2: JBI checklist for quasi-experimental studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A., C.P., A.I.O., P.B. and A.C.; Methodology, R.A. and A.C.; Investigation, R.A., C.P. and A.C.; Data curation, R.A. and C.P.; Formal analysis, R.A., C.P., A.I.O., P.B. and A.C.; Visualization, R.A., A.I.O. and P.B.; Validation, A.C.; Writing—original draft preparation, R.A. and C.P.; Writing—review and editing, C.P., A.I.O., P.B. and A.C.; Supervision, A.C.; Funding acquisition, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received financial support from the PT national funds (FCT/MECI, Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia and Ministério da Educação, Ciência e Inovação) through the project UID/50006/2025 DOI 10.54499/UID/50006/2025—Laboratório Associado para a Química Verde—Tecnologias e Processos Limpos.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| CFUs | Colony-Forming Units |

| CFU/mL | Colony-Forming Units per Milliliter |

| RCTs | Randomized Controlled Trials |

| ChiCTR | Chinese Clinical Trial Registry |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| GIT | Gastrointestinal |

| AIDS | Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome |

| WIHS | Women’s Interagency HIV Study |

| MMS | Mini-Mental State test |

| SDA | Sabouraud Dextrose Agar |

| spp. | Species |

| BID | Twice a day |

| TID | Three times a day |

| KOH | Potassium hydroxide |

| NaCl | Sodium chloride |

| AEs | Adverse Events |

| VAS | Visual Analogue Scale |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| SABC | Sabouraud’s Dextrose Agar with Chloramphenicol |

| UC | Unclear |

References

- Hu, H.; Merenstein, D.J.; Wang, C.; Hamilton, P.R.; Blackmon, M.L.; Chen, H.; Calderone, R.A.; Li, D. Impact of Eating Probiotic Yogurt on Colonization by Candida Species of the Oral and Vaginal Mucosa in HIV-Infected and HIV-Uninfected Women. Mycopathologia 2013, 176, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, X.; Gómez, L.; Vergara, C.; Astorga, E.; Cajas, N.; Ivankovic, M. Association between Presence of Candida Yeasts and Elderly Patient Factors with and without Denture Stomatitis. Int. J. Odontostomat 2013, 7, 279–285. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, K.H.; Mayer, M.P.A.; Miyazima, T.Y.; Matsubara, V.H.; Silva, E.G.; Paula, C.R.; Campos, T.T.; Nakamae, A.E.M. A Multispecies Probiotic Reduces Oral Candida Colonization in Denture Wearers. J. Prosthodont. 2015, 24, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, T.; Neves, A.; Leão, M.; Jorge, A. Vinegar as an Antimicrobial Agent for Control of Candida Spp. in Complete Denture Wearers. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2008, 16, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, C.; Pascale, M.; Contaldo, M.; Esposito, V.; Busciolano, M.; Milillo, L.; Guida, A.; Petruzzi, M.; Serpico, R. Candida-Associated Denture Stomatitis. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2011, 16, e139–e143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beetz, I.; Schilstra, C.; Burlage, F.R.; Koken, P.W.; Doornaert, P.; Bijl, H.P.; Chouvalova, O.; Leemans, C.R.; de Bock, G.H.; Christianen, M.E. Development of NTCP Models for Head and Neck Cancer Patients Treated with Three-Dimensional Conformal Radiotherapy for Xerostomia and Sticky Saliva: The Role of Dosimetric and Clinical Factors. Radiother. Oncol. 2012, 105, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, B.; Goyal, R.; Dutta, S.; Joshi, P.; Sanyal, K. Candida Albicans: Insights into the Biology and Experimental Innovations of a Commonly Isolated Human Fungal Pathogen. ACS Infect. Dis. 2025, 11, 1780–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anil, S.; Vellappally, S.; Hashem, M.; Preethanath, R.; Patil, S.; Samaranayake, L. Xerostomia in Geriatric Patients: A Burgeoning Global Concern. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2014, 7, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, R.; Kimmie-Dhansay, F. Prevalence of Denture-Related Stomatitis in Edentulous Patients at a Tertiary Dental Teaching Hospital. Front. Oral. Health 2021, 2, 772679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendreau, L.; Loewy, Z. Epidemiology and Etiology of Denture Stomatitis. J. Prosthodont. 2011, 20, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Anil Kumar, D.; Tamrakar, A.; Singh Bhasin, S. Candida Spp. in Oral Mucosa of Denture Wearers: A Pilot Study. NJIRM 2017, 8, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Chladek, G.; Basa, K.; Mertas, A.; Pakieła, W.; Żmudzki, J.; Bobela, E.; Król, W. Effect of Storage in Distilled Water for Three Months on the Antimicrobial Properties of Poly (Methyl Methacrylate) Denture Base Material Doped with Inorganic Filler. Materials 2016, 9, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gad, M.M.; Al-Thobity, A.M.; Shahin, S.Y.; Alsaqer, B.T.; Ali, A.A. Inhibitory Effect of Zirconium Oxide Nanoparticles on Candida Albicans Adhesion to Repaired Polymethyl Methacrylate Denture Bases and Interim Removable Prostheses: A New Approach for Denture Stomatitis Prevention. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 5409–5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Cuesta, C.; Sarrion-Pérez, M.; Bagán, J. Current Treatment of Oral Candidiasis: A Literature Review. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2014, 6, e576–e582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.J.; Dhaliwal, H.S.; Theaker, E.D.; Pemberton, M.N. Patterns of Antifungal Prescribing in General Dental Practice. Br. Dent. J. 2004, 196, 701–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hamad, M. Antifungal Immunotherapy and Immunomodulation: A Double-Hitter Approach to Deal with Invasive Fungal Infections. Scand. J. Immunol. 2008, 67, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, V.; Bandara, H.; Mayer, M.; Samaranayake, L. Probiotics as Antifungals in Mucosal Candidiasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 1143–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niimi, M.; Firth, N.A.; Cannon, R.D. Antifungal Drug Resistance of Oral Fungi. Odontology 2010, 98, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakka, K.; Ahola, A.J.; Yli-Knuuttila, H.; Richardson, M.; Poussa, T.; Meurman, J.H.; Korpela, R. Probiotics Reduce the Prevalence of Oral Candida in the Elderly-a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Dent. Res. 2007, 86, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, Q.; Liu, C.; Lin, M.; Li, X.; Xiao, X.; Zhu, Z.; Gong, Q.; Zhou, H. Efficacy and Safety of Probiotics in the Treatment of Candida-Associated Stomatitis. Mycoses 2014, 57, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonça, F.H.B.P.; dos Santos, S.S.F.; da Silva de Faria, I.; Gonçalves e Silva, C.R.; Jorge, A.O.C.; Leão, M.V.P. Effects of Probiotic Bacteria on Candida Presence and IgA Anti-Candida in the Oral Cavity of Elderly. Braz. Dent. J. 2012, 23, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO. Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food; FAO/WHO: London, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hasslöf, P.; Hedberg, M.; Twetman, S.; Stecksén-Blicks, C. Growth Inhibition of Oral Mutans Streptococci and Candida by Commercial Probiotic Lactobacilli-an in Vitro Study. BMC Oral Health 2010, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, G.; Assefa, S.; Reid, G. Probiotic Interference of Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GR-1 and Lactobacillus Reuteri RC-14 with the Opportunistic Fungal Pathogen Candida Albicans. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 2012, 636474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sookkhee, S.; Chulasiri, M.; Prachyabrued, W. Lactic Acid Bacteria from Healthy Oral Cavity of Thai Volunteers: Inhibition of Oral Pathogens. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 90, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, T.; Takagi, A.; Ikemura, H.; Matsuguchi, T.; Yokokura, T. Intestinal Microflora: Probiotics and Autoimmunity. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 798S–802S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosseau, C.; Devine, D.A.; Dullaghan, E.; Gardy, J.L.; Chikatamarla, A.; Gellatly, S.; Yu, L.L.; Pistolic, J.; Falsafi, R.; Tagg, J. The Commensal Streptococcus Salivarius K12 Downregulates the Innate Immune Responses of Human Epithelial Cells and Promotes Host-Microbe Homeostasis. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 4163–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caglar, E.; Kuscu, O.; Cildir, S.; Kuvvetli, S.; Sandalli, N. A Probiotic Lozenge Administered Medical Device and Its Effect on Salivary Mutans Streptococci and Lactobacilli. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2008, 18, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, S.; Pang, G.; Ashman, R.; Clancy, R. Enhanced Clearance of Candida Albicans from the Oral Cavities of Mice Following Oral Administration of Lactobacillus Acidophilus. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2005, 141, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meurman, J.H.; Stamatova, I. Probiotics: Contributions to Oral Health. Oral Dis. 2007, 13, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; Shamseer, L.; Tricco, A.C. Registration of Systematic Reviews in PROSPERO: 30,000 Records and Counting. Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, L.; Marques, J.M.; Firmino, C.F.; Frade, F.; Valentim, O.S.; Antunes, A.V. Modelos de Formulação Da Questão de Investigação Na Prática Baseada Na Evidência. Available online: https://repositorio-cientifico.essatla.pt/handle/20.500.12253/1287 (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Barker, T.H.; Habibi, N.; Aromataris, E.; Stone, J.C.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Sears, K. The Revised JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for the Assessment of Risk of Bias Quasi-Experimental Studies. JBI Evid. Synth. 2024, 22, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, T.H.; Stone, J.C.; Sears, K.; Klugar, M.; Tufanaru, C.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. The Revised JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for the Assessment of Risk of Bias for Randomized Controlled Trials. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuinness, L.A.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk-of-bias VISualization (Robvis): An R Package and Shiny Web App for Visualizing Risk-of-bias Assessments. Res. Synth. Methods 2021, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsayes, S.A.; El Attar, M.S.; ElHadary, A.; Aboulela, A.G.; Essawy, M.M.; Soliman, I.S. Antimycotic Prophylaxis with Multispecies Probiotics against Oral Candidiasis in New Complete Denture Wearers: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 134, 1852–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evirgen, Ş.; Kahraman, E.N.; Korcan, S.E.; Yıldırım, B.; Şimşek, A.T.; Aydın, B.; Ünal, M. Intake of Probiotics as an Option for Reducing Oral and Prosthetic Microbiota: A Clinical Study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 133, 1276.e1–1276.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Mao, Q.; Zhou, P.; Lv, X.; Hua, H.; Yan, Z. Effects of Streptococcus Salivarius K12 with Nystatin on Oral Candidiasis-RCT. Oral Dis. 2019, 25, 1573–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazima, T.; Ishikawa, K.; Mayer, M.; Saad, S.; Nakamae, A. Cheese Supplemented with Probiotics Reduced the Candida Levels in Denture Wearers-RCT. Oral Dis. 2017, 23, 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft-Bodi, E.; Jorgensen, M.; Keller, M.; Kragelund, C.; Twetman, S. Effect of Probiotic Bacteria on Oral Candida in Frail Elderly. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 181S–186S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How, Y.-H.; Yeo, S.-K. Oral Probiotic and Its Delivery Carriers to Improve Oral Health: A Review. Microbiology 2021, 167, 001076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anusha, R.L.; Umar, D.; Basheer, B.; Baroudi, K. The Magic of Magic Bugs in Oral Cavity: Probiotics. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2015, 6, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kariyawasam, K.M.G.M.M.; Lee, N.-K.; Paik, H.-D. Fermented Dairy Products as Delivery Vehicles of Novel Probiotic Strains Isolated from Traditional Fermented Asian Foods. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 2467–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).