Beyond the Mortality Effect: Spodoptera frugiperda Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus Promotes Changes in Feeding and Inhibits Larval Growth and Weight Gain in Fall Armyworm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bioassays

2.2. Data Analysis

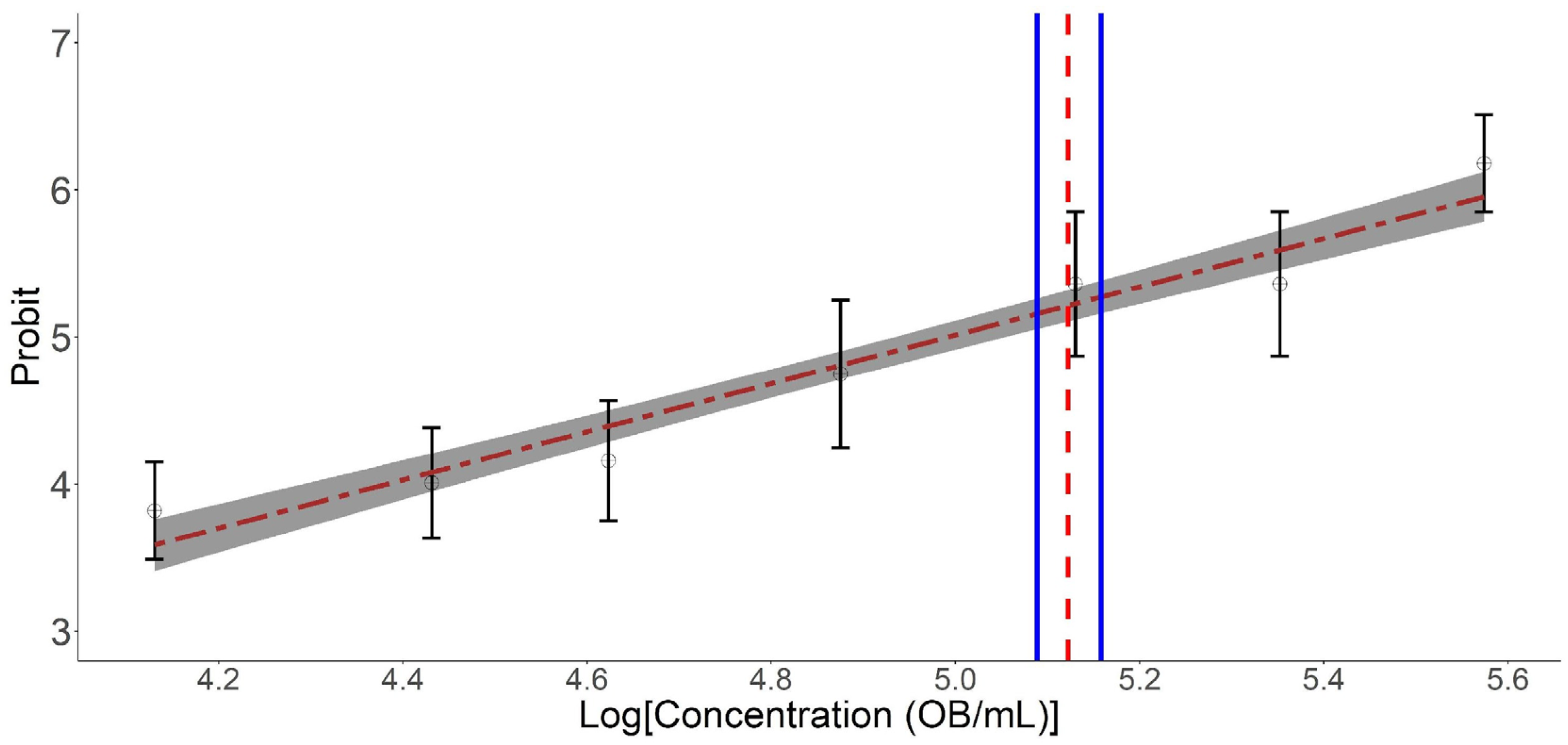

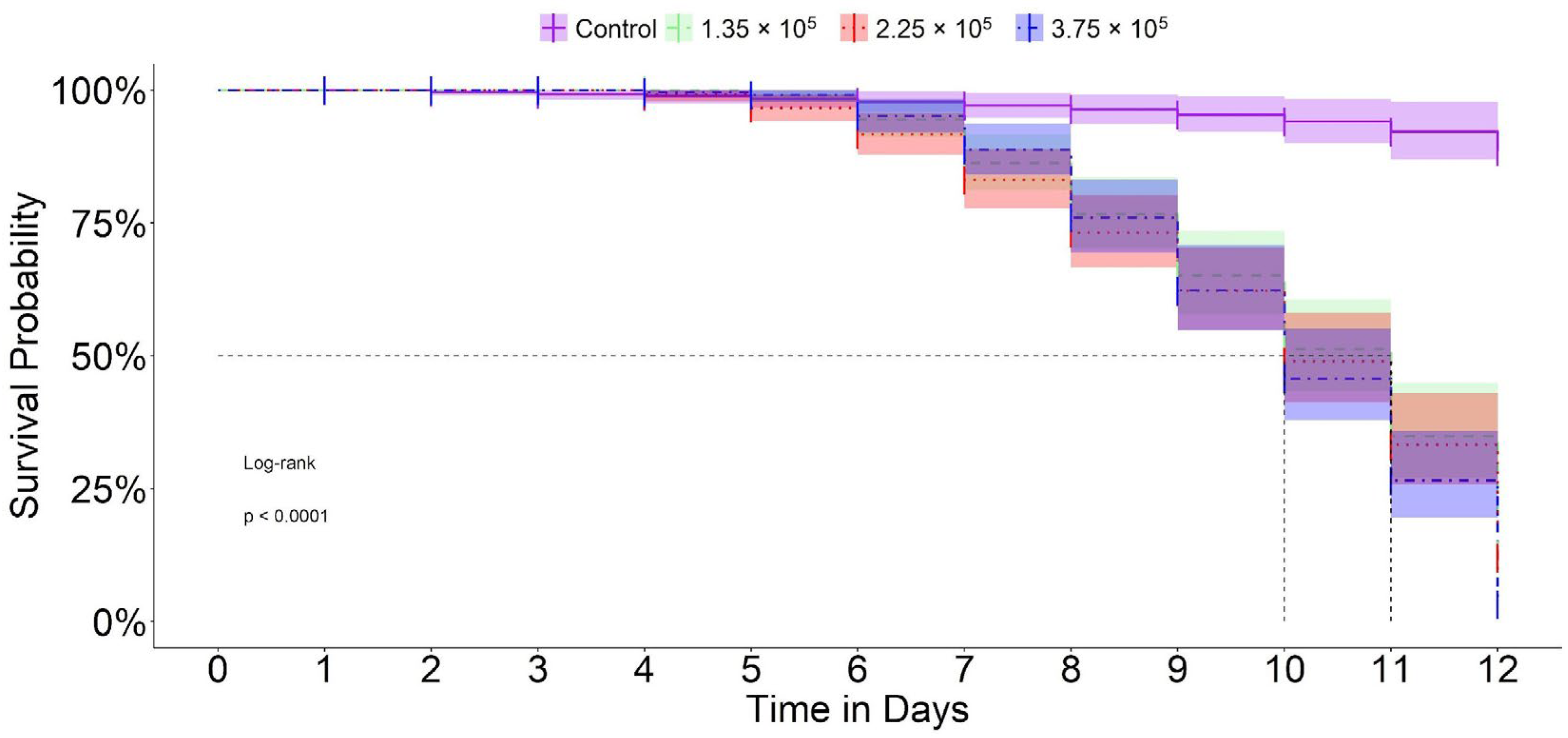

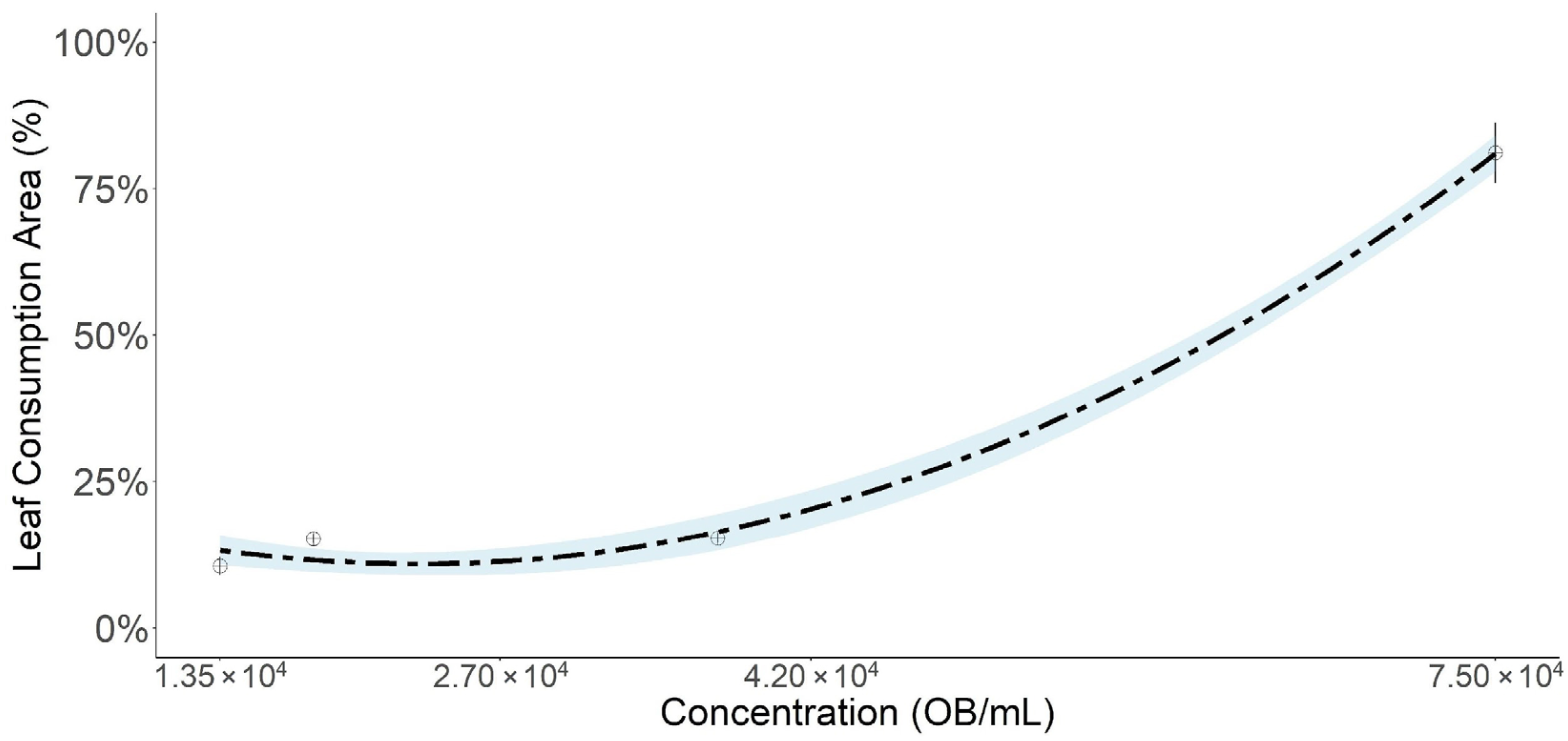

3. Results

Weight Gain Inhibition

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EPPO Global Database. Spodoptera frugiperda (LAPHFR). 2024. Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/LAPHFR/distribution (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Montezano, D.G.; Sosa-Gómez, D.R.; Specht, A.; Roque-Specht, V.F.; Sousa-Silva, J.C.; Paula-Moraes, S.D.; Hunt, T.E. Host plants of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in the Americas. Afr. Entomol. 2018, 26, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.G.; Wennmann, J.T.; Goergen, G.; Bryon, A.; Ros, V.I. Viruses of the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda: A review with prospects for biological control. Viruses 2021, 13, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.Q.; Li, P.P.; Yin, J.; Li, Y.K.; Chen, D.K.; Bao, H.N.; Yao, N. Arabidopsis alkaline ceramidase ACER functions in defense against insect herbivory. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 4954–4967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Xiao, F.; Ojo, J.; Chao, W.H.; Ahmad, B.; Alam, A.; Chen, R. Insect Resistance to Insecticides: Causes, Mechanisms, and Exploring Potential Solutions. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 118, e70045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, J.A.; Fan, R.; Naz, H.; Bamisile, B.S.; Hafeez, M.; Ghani, M.I.; Chen, X. Insights into insecticide-resistance mechanisms in invasive species: Challenges and control strategies. Front. Physiol. 2023, 13, 1112278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landwehr, A. Benefits of baculovirus use in IPM strategies for open field and protected vegetables. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 4, 593–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Alami, M.M.; Alrefaei, A.F.; Abbas, Q.; Naqvi, S.A.H.; Rao, M.J.; Mosa, W.F.A.; Hussain, A.; et al. Drones in plant disease assessment, efficient monitoring, and detection: A way forward to smart agriculture. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, V.I. Baculoviruses: General features (Baculoviridae). In Encyclopedia of Virology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisler, F.C.S.; Martins, L.N.; Machado, I.E.D.F.; Matozo, L.F.; Lucena, W.F.; Soares, V.N.; Bernardi, D. The biological activity of an SfMNPV-based biopesticide on a resistant strain of Spodoptera frugiperda developing on transgenic corn expressing Cry1A.105 + Cry2Ab2 + Cry1F insecticidal protein. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrmann, G.F. Chapter 3, The baculovirus replication cycle: Effects on cells and insects. In Baculovirus Molecular Biology, 4th ed.; National Center for Biotechnology Information (US): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Lei, C.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Hu, J.; Sun, X. Molecular and biological characterization of Spodoptera frugiperda multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus field isolate and genotypes from China. Insects 2020, 11, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, W.A.; Valle, J.; Ibarra, J.E.; Cisneros, J.; Penagos, D.I.; Williams, T. Spinosad and nucleopolyhedrovirus mixtures for control of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in maize. Biol. Control 2002, 25, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakseski, M.R.; Silva Filho, J.G.; Rakes, M.; Pazini, J.D.B.; da Rosa, A.P.S.; Marçon, P.; Popham, H.J.; Bernardi, O.; Bernardi, D. Pathogenic assessment of SfMNPV-based biopesticide on Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) developing on transgenic soybean expressing Cry1Ac insecticidal protein. J. Econ. Entomol. 2021, 114, 2264–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presa-Parra, E.; Navarro-De-La-Fuente, L.; Williams, T.; Lasa, R. Can low concentration flufenoxuron treatment increase the pathogenicity or production of nucleopolyhedrovirus occlusion bodies in Spodoptera exigua (Hübner) or Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)? Acta Zoológica Mex. 2023, 39, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Castillo, A.M.; Zamora-Avilés, N.; Camargo, A.H.; Figueroa-De la Rosa, J.I.; Pineda, S.; Ramos-Ortiz, S. Biological activity of two Mexican nucleopolyhedrovirus isolates and sublethal infection effects on Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Fla. Entomol. 2022, 105, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalim, D.M.; Parra, J.R.P. Biologia, Nutrição Quantitativa e Controle de Qualidade de Populações de Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith, 1797) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) em duas Dietas Artificiais. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, Piracicaba, São Paulo, March 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cabrera, J.; Contreras-Bermúdez, Y.; Sánchez-González, J.A.; Gutiérrez-Campos, J.M. Development of an artificial diet with a mass-rearing and low-cost approach for Spodoptera frugiperda reproduction. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2024, 44, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentivenha, J.P.; Rodrigues, J.G.; Lima, M.F.; Marçon, P.; Popham, H.J.; Omoto, C. Baseline susceptibility of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) to SfMNPV and evaluation of cross-resistance to major insecticides and Bt proteins. J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A.; Kosinski, M.; Biecek, P.; Fabian, S. Drawing Survival Curves Using “Ggplot2”. Available online: https://rpkgs.datanovia.com/survminer/index.html (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Mweke, A.; Rwomushana, I.; Okello, A.; Chacha, D.; Guo, J.; Luke, B. Management of Spodoptera frugiperda JE Smith Using Recycled Virus Inoculum from Larvae Treated with Baculovirus under Field Conditions. Insects 2023, 14, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.P.; Green, T.A.; Loker, A.J. Biological control and integrated pest management in organic and conventional systems. Biol. Control 2020, 140, 104095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgievska, L.; Hoover, K.; van der Werf, W.; Muñoz, D.; Caballero, P.; Cory, J.S.; Vlak, J.M. Dose dependency of time to death in single and mixed infections with a wildtype and egt deletion strain of Helicoverpa armigera nucleopolyhedrovirus. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 104, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Manzoor, S.; Gani, M.; Hassan, T.; Shafi, I.; Wani, F.J.; Mumtaz, S.; Mantoo, M.A. Comparative evaluation of temperate, subtropical, and tropical isolates of nucleopolyhedrovirus against tomato fruit borer, Helicoverpa armigera (Hubner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Egyp. J. Biol. Pest Control 2023, 33, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese1, E.J.; Baldwin, L.A. Hormesis: A generalizable and unifying hypothesis. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2001, 31, 353–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.M. Effect of sublethal doses of some insecticides and their role on detoxication enzymes and protein-content of Spodoptera littoralis (Boisd.) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2020, 44, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.L.Z. Diferentes Plantas Hospedeiras Alteram a Suscetibilidade de Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) ao SfMNPV e Modulam os seus Parâmetros de Desenvolvimento e Fisiológicos. Ph.D. Thesis, Paulista State University, Jaboticabal, Brazil, May 2024. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11449/256097 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Llopis-Giménez, A.; Parenti, S.; Han, Y. A proctolin-like peptide is regulated after baculovirus infection and mediates in caterpillar locomotion and digestion. Insect Sci. 2022, 29, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard Error | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| W0 | 47.40 mg | 49.18 | 46.50–48.40 mg |

| B | 1.42 | 0.07 | 1.28–1.57 |

| EC50 (OBs/mL) | 1.16 × 104 | 4.27 × 102 | 1.07 × 104–1.24 × 104 |

| Concentration (OBs/mL) | Biological Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Head Diameter (mm) | Body Length (mm) | Body Width (mm) | |

| 0 | 1.26 ± 0.05 (1.12–1.32) a | 12.01 ± 0.31 (08.01–14.00) a | 1.52 ± 0.20 (1.22–1.84) a |

| 1.35 × 104 | 0.44 ± 0.20 (0.18–0.77) b | 6.67 ± 2.77 (2.82–10.52) b | 0.73 ± 0.32 (0.27–1.18) b |

| 2.70 × 104 | 0.33 ± 0.22 (0.17–0.68) b | 4.04 ± 2.40 (0.52–7.30) b | 0.43 ± 0.28 (0.16–0.96) b |

| 4.20 × 104 | 0.32 ± 0.15 (0.12–0.55) b | 3.61 ± 2.01 (0.90–6.40) b | 0.34 ± 0.24 (0.14–0.64) b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nascimento, B.M.C.; Nunes, A.D.M.; Souza Junior, S.L.d.; Santos, L.F.d.S.; Mielezrski, F.; Brito, C.H.d.; Cândido, B.Á.P.; de Medeiros, I.L.; Praxedes Júnior, W.G.; Rezende, J.M.; et al. Beyond the Mortality Effect: Spodoptera frugiperda Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus Promotes Changes in Feeding and Inhibits Larval Growth and Weight Gain in Fall Armyworm. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010001

Nascimento BMC, Nunes ADM, Souza Junior SLd, Santos LFdS, Mielezrski F, Brito CHd, Cândido BÁP, de Medeiros IL, Praxedes Júnior WG, Rezende JM, et al. Beyond the Mortality Effect: Spodoptera frugiperda Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus Promotes Changes in Feeding and Inhibits Larval Growth and Weight Gain in Fall Armyworm. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleNascimento, Bianca Marina Costa, Anderson Delfino Mauricio Nunes, Silvio Lisboa de Souza Junior, Luiz Fernando de Santana Santos, Fabio Mielezrski, Carlos Henrique de Brito, Breno Álef Parnaíba Cândido, Isabel Lopes de Medeiros, Wanderlan Gonçalves Praxedes Júnior, Janayne Maria Rezende, and et al. 2026. "Beyond the Mortality Effect: Spodoptera frugiperda Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus Promotes Changes in Feeding and Inhibits Larval Growth and Weight Gain in Fall Armyworm" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010001

APA StyleNascimento, B. M. C., Nunes, A. D. M., Souza Junior, S. L. d., Santos, L. F. d. S., Mielezrski, F., Brito, C. H. d., Cândido, B. Á. P., de Medeiros, I. L., Praxedes Júnior, W. G., Rezende, J. M., Ramalho, F. d. S., Mussury Franco Silva, R. M., & Malaquias, J. B. (2026). Beyond the Mortality Effect: Spodoptera frugiperda Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus Promotes Changes in Feeding and Inhibits Larval Growth and Weight Gain in Fall Armyworm. Microorganisms, 14(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010001