1. Introduction

Streptomyces can produce numerous secondary metabolites (SMs) [

1,

2,

3]. These bioactive natural products (NPs) serve as feasible lead compounds in innovative drug development [

2,

3,

4]. However, full-scale mining of the valuable SMs encoded in the genomes of various wild-type (WT)

Streptomyces strains remains a challenge [

5]. Firstly, the obvious difference between the laboratory environment and bacterial natural habitats could hamper SM production by repressing the expression of their biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in routine strain cultivation [

5,

6]. Directly activating these silent BGCs requires precise genomic information or mature genetic manipulation tools, which are often unavailable for WT strains [

7,

8]. Thus, to overcome the aforementioned barriers, the relatively simple and versatile ribosome engineering has been employed to stimulate the production of

Streptomyces SMs recently [

9,

10,

11]. This strategy, derived from the research regarding bacterial “stringent response”, positively regulates their secondary metabolism, can efficiently generate desirable SM-producing mutants simply by treating

Streptomyces strains with rifampicin [

9,

12]. During the “stringent response”, strains can produce abundant signal molecule ppGpp to bind the ppGpp-sensitive domain in the β-subunit of RNA polymerase (RNAP) [

9,

12]. This binding could modulate RNAP activity by enhancing the gene expression involved in SM biosynthesis [

9,

12,

13]. Coincidentally, the ppGpp-sensitive domain is located close to the rifampicin binding domain in RNAP β-subunit [

9,

12].

Streptomyces strains treated with rifampicin can acquire resistant mutations in

rpoB, which will encode the corresponding mutant β-subunit to form relevant resistant mutant RNAP in generated mutant strains [

9,

12]. Subsequent binding of rifampicin to the mutant RNAP, similarly to the abovementioned ppGpp binding to its sensitive domain in RNAP, could also activate the expression of biosynthetic genes to produce bioactive SMs in

Streptomyces strain [

9,

12,

13].

As a straightforward strategy, ribosome engineering is independent of the target strains’ mature genetic condition [

12]. Thus, this reliable strategy is quite suitable for dealing with difficult

Streptomyces strains without complete genome information and established genetic manipulation systems [

9,

11]. In this study,

Streptomyces sp. PRh3 (PRh3) is a new endophytic strain isolated from Dongxiang wild rice (DXWR), a wild crop with the highest latitude distribution and excellent environmental adaptability [

14]. In view of PRh3’s distinct habitat, the comprehensive fermentation coupled with metabolite profiling was performed. However, these laboratory assays failed to detect any meaningful SM from this strain or to acquire its high-quality whole-genome sequence. Due to this abnormal situation, a conventional ribosome engineering treatment (rifampicin in concentration gradient) was adopted to improve the secondary metabolism in PRh3 and generated an expected resistant mutant strain PRh3-r55, which acquired an H473Y rifampicin-resistant mutation in

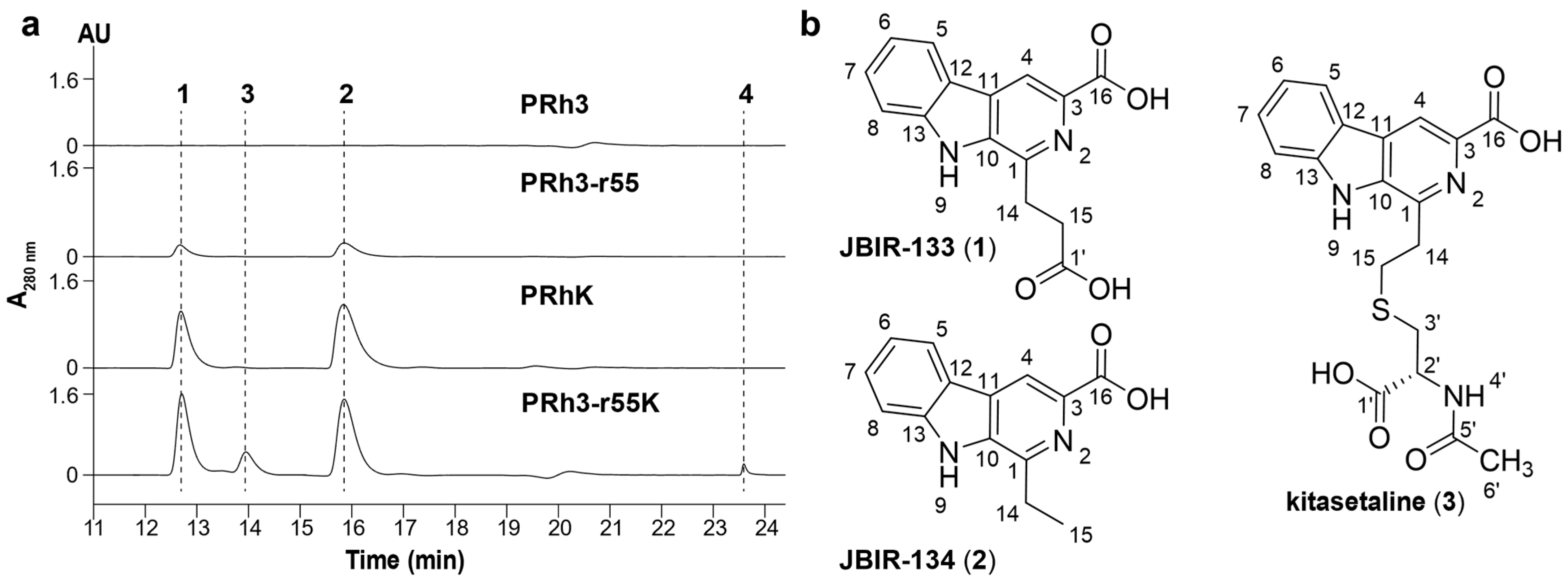

rpoB and was activated to produce a small amount of two β-carboline alkaloids, JBIR-133 and JBIR-134.

Previous research has revealed that

Kitasatospora setae NBRC 14216

T, harboring BGC

ksl, can produce JBIR-133, JBIR-134, and the additional β-carboline alkaloid, kitasetaline [

15,

16,

17]. Nevertheless, identification of

ksl-homologous BGC in PRh3 was blocked due to a lack of genome sequence, which also, in return, hampered the subsequent discovery of β-carboline alkaloids from PRh3. Therefore, given the consistency of producing JBIR-133 and JBIR-134 in the above two strains, we adopted a substituted heterologous expression by overexpressing

ksl in PRh3-r55 and generated the derivative mutant strain PRh3-r55K. This attempt not only effectively enhanced the production of JBIR-133 and JBIR-134, but also achieved a synergistic effect between the heterologous expression of

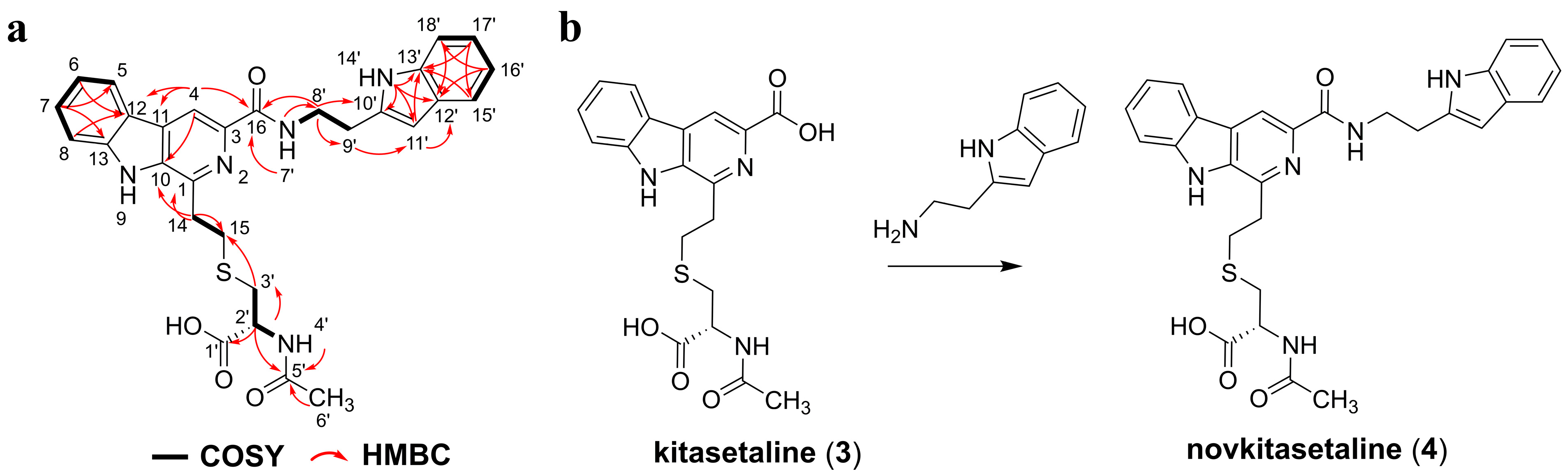

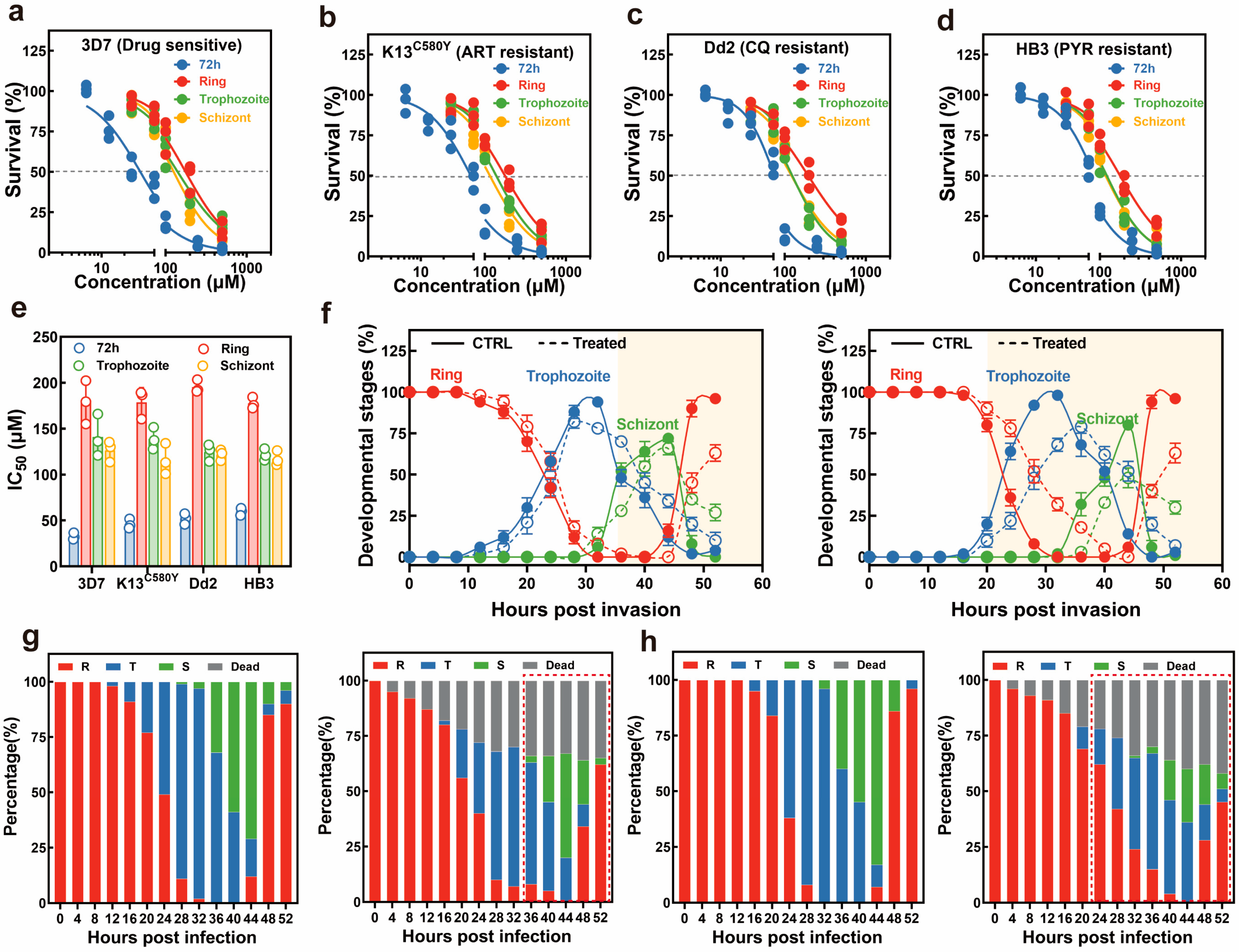

ksl and the optimized intracellular secondary metabolic environment of the host strain, which enabled PRh3-r55K to produce kitasetaline and novkitasetaline. Novkitasetaline is a derivative of kitasetaline, where the carboxyl group at C-3 of the pyridine ring forms an amide bond with tryptamine. This structural modification significantly enhanced the molecules’ antimalarial activity. Novkitasetaline exhibited potency against

Plasmodium falciparum 3D7 with an IC

50 value of 32.65 ± 2.93 μM. In contrast, its precursor, kitasetaline, exhibited no obvious antimalarial bioactivity. Notably, novkitasetaline also exhibited activity against the drug-resistant

P. falciparum strains with IC

50 of 45.98 ± 4.17 μM (K13

C580Y), 51.88 ± 4.76 μM (Dd2), and 59.67 ± 3.15 μM (HB3). These consistent activities against both drug-sensitive and drug-resistant parasites revealed that novkitasetaline possessed a relatively broad antimalarial spectrum. Furthermore, novkitasetaline exerted peak antimalarial activity against late-stage parasites (specifically the trophozoite-to-schizont transition phase) by either arresting parasite growth or impairing merozoite invasion. In conclusion, this study successfully activated the biosynthetic potential of β-carboline alkaloids in PRh3 by combining ribosome engineering with the heterologous expression of

ksl. This combinatorial strategy not only obtained a new sulfur-containing antimalarial β-carboline alkaloid, novkitasetaline, but also provided new insight into mining of bioactive NPs from

Streptomyces.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strain and Culture Condition

PRh3 was isolated from DXWR, Jiangxi province, China (28°14′ N, 116°30′ E). This strain has been deposited into the Guangdong Microbial Culture Collection Center (GDMCC) with the number GDMCC 65483. This strain and its mutants were cultivated on a modified-ISP4 (M-ISP4) plate [

18]. For each fermentation, 50 μL of spore suspension (10

7 spores) of PRh3 and its derived mutant strains was inoculated into 50 mL liquid M-ISP4 in the 250 mL flasks, then incubated at 28 °C and 200 rpm for 6 days. The 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequence of PRh3 was uploaded to the GenBank with accession Number PV855736.1.

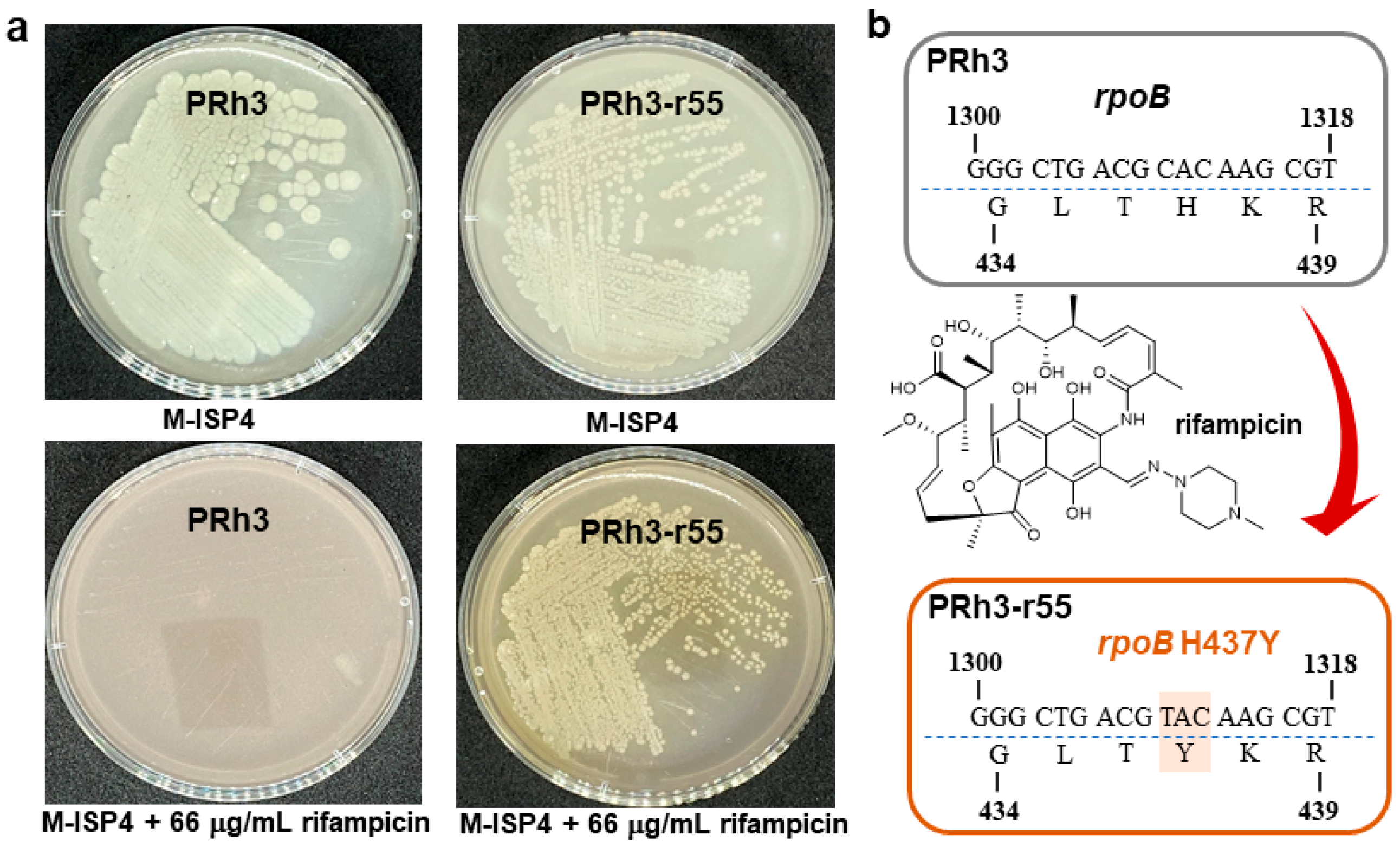

2.2. Ribosome Engineering of PRh3

Spore suspensions (10

6–10

7 spores) of PRh3 were spread onto an M-ISP4 plate containing different concentrations (5–100 μg/mL) of rifampicin and cultivated at 28 °C for persistent observation. Then the minimal inhibition concentration (MIC) of rifampicin against PRh3 was determined at 22 μg/mL. The following treatments of PRh3 were carried out by applying rifampicin at concentrations of 1 × MIC-5 × MIC on the M-ISP4 plates to obtain resistant mutant strains. Genetic characterization of the

rpoB mutation in the final selected rifampicin-resistant mutant strain PRh3-r55 was performed by PCR using four pairs of primers (

Table S1). The amplified oligonucleotides were cloned onto the

pEASY®-T&B simple cloning Vector (Transgen biotech; Beijing, China) and sequenced to verify the mutations. The sequence of

rpoB was also uploaded to the GenBank with accession Number PV870206.1.

2.3. Heterologous Expression of ksl in PRh3 and PRh3-r55

To effectively activate the expression of

ksl, the necessary corresponding vector pJN44 was designed and constructed. This vector was derived from pSET152. Firstly, the pSET152 was digested by EcoRI and XbaI to yield a related linear vector. Then, two sequence-complementary oligonucleotides containing cohesive ends of EcoRI and XbaI were annealed to form the corresponding double-stranded fragment by touchdown polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (

Table S2). This double-stranded product also contained the promoter SP44, ribosome binding site (RBS) SR40, and two additional restriction enzyme recognition sites: NdeI and BamHI [

19]. Finally, the double-stranded DNA was ligated into previously prepared linear pSET152 to generate the pJN44.

The pJN44 was digested by NdeI and Xba1 to yield the linear vector. Then the full-length (3389 bp)

ksl was amplified from the genomic DNA of

Kitasatospora setae NBRC 14216

T by using one pair of primers (

Table S3). Subsequently, the

ksl fragment was ligated into the linear pJN44 to generate the pJN44-

ksl by using the “LightNing

® DNA Assembly Mix Plus” (BestEnzymes; Lianyungang, China).

The pJN44-

ksl was subsequently transformed into the PRh3 and PRh3-r55 by

Escherichia coli ET12567/pUZ8002 mediated conjugation [

20]. Target exconjugants were subsequently selected on M-ISP4 plates supplied with 50 μg/mL apramycin to confirm their antibiotic resistance. Then, single colonies were patched onto M-ISP4 plates containing 50 μg/mL apramycin, and the correct PRh3-r55K was further verified by PCR and sequencing (

Table S3).

2.4. Strain Fermentation, Product Isolation, and Identification

To isolate JBIR-133 and JBIR-134 from PRh3-r55, a 2-step fermentation process was adopted. First, the spores of PRh3-r55 were inoculated into 50 mL liquid M-ISP4 in the 250 mL flask and cultured at 28 °C and 200 rpm for 36 h. Then, these seed cultures were transferred into 200 mL liquid M-ISP4 in the 1 L flask and cultured at 28 °C and 200 rpm for an additional 7 days. At last, about 5 L cultures were harvested in this way. All the culture broth was centrifuged and divided into the supernatant and the mycelium cake. The supernatant was extracted with equal ethyl acetate three times and evaporated to dryness. The mycelium was extracted with acetone and evaporated to dryness too. These two extracts were dissolved and mixed with silica gel (100–200 mesh) for normal phase silica gel column chromatography, which was eluted by CH2Cl2/MeOH mixture at 100/0, 98/2, 96/4, 95/5, 93/7, 90/10, 80/20, and 50/50 to yield 8 fractions (Afr1–Afr8). The Afr3 was then subjected to the following gel permeation chromatography to yield an additional 52 fractions (Bfr1-Bfr52). The Bfr11-Bfr14 were mixed and purified by semi-preparative HPLC with a YMC-Pack ODS-A column (250 mm × 10 mm, 5 μm) to give the resulting 4.1 mg JBIR-133 and 3.3 mg JBIR-134.

To isolate JBIR-133, JBIR-134, kitasetaline, and novkitasetaline from PRh3-r55k, another 2-step fermentation process was adopted. The spores of PRh3-r55k were also inoculated into 50 mL liquid M-ISP4 in the 250 mL flask and cultured at 28 °C and 200 rpm for 36 h. Then, the seed culture was transferred into 250 mL liquid M-ISP4 in the 1 L flask and cultured at 28 °C and 200 rpm for an additional 6 days. At last, about 20 L of cultures were harvested in this way. All the culture broth was centrifuged and divided into the supernatant and the mycelium cake. The supernatant was extracted with equal ethyl acetate three times and evaporated to dryness. The mycelium was extracted with acetone and evaporated to dryness too. These two extracts were dissolved and mixed with silica gel (100–200 mesh) for normal phase silica gel column chromatography, which was eluted by CH2Cl2/MeOH mixture at 100/0, 98/2, 96/4, 95/5, 93/7, 90/10, 80/20, and 50/50 to yield 8 fractions (Afr1–Afr8). The Afr3–Afr4 was then subjected to the following gel permeation chromatography to yield an additional 102 fractions (Bfr1–Bfr102). The Bfr16–Bfr22 were mixed and purified by semi-preparative HPLC with a YMC-Pack ODS-A column (250 mm × 10 mm, 5 μm) to give the resulting 15.1 mg JBIR-133 and 9.2 mg JBIR-134, respectively. The Bfr47–Bfr48 was mixed and purified by the same semi-preparative HPLC to yield 4.2 mg kitasetaline and 3.5 mg novkitasetaline, respectively.

Analytic HPLC of β-carboline alkaloids was performed at 280 nm with an Agilent 1260 Infinity series instrument (Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a diode array detector (DAD) and an Agilent ZORBAX SB-C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm). The solvent system consists of solvents A (water with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) and B (acetonitrile with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid). The elution process was run under the following conditions: 5% B to 50% B (linear gradient, 0–15 min), 50% B to 80% B (linear gradient, 15–20 min), 80% B to 100% B (linear gradient, 20–21 min), 100% B (isocratic elution, 21–24 min), 100% B to 5% B (linear gradient, 24–25 min), and 5% B (isocratic elution, 25–30 min). The flow rate is set at 1 mL/min. Optical rotation was measured on an Anton Paar MCP 5300 polarimeter (Graz, Austria) at 25 °C and a wavelength of 589 nm. High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HRESIMS) data were acquired on a ZenoTOF 7600 system (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA), using a syringe pump operated at 0.4 mL/min. The solvent system consists of solvents A (water) and B (acetonitrile). The elution process was run under the following conditions: 10% B (isocratic elution, 0–0.6 min), 10% B to 95% B (linear gradient, 0.6–1 min), 95% B (isocratic elution, 1–3.5 min), 95% B to 10% B (linear gradient, 3.5–3.6 min), 10% B (isocratic elution, 3.6–5 min). Full scan data were acquired in the positive ionization mode using a spray voltage of 5.5 kV. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were acquired at 298 K on a Bruker Avance IIIHD 600M, a Bruker Avance NEO 400M, and a Bruker Avance IIIHD 700M (Bruker, Bremen, Germany) spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm TCI CryoProbe (Bruker, Germany), using standard Bruker pulse sequences and phase cycling. NMR data were analyzed using the MestReNova v14.0 software (Mestrelab Research, Santiago de Compostela, Spain).

2.5. Antimalarial Activity Assay

2.5.1. Ethics Statements

This study was carried out in accordance with the institutional guidelines for the care and use of biosamples in Jiangsu Institute of Parasitic Diseases (JIPD). The experimental design was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of JIPD (JIPD-2022-005).

2.5.2. Parasite Culturing

Plasmodium falciparum strains—including the wild-type (3D7), artemisinin (ART)-resistant strain (K13

C580Y), chloroquine (CQ)-resistant strain (Dd2), and pyrimethamine (PYR)-resistant strain (HB3)—were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 0.5% (

w/

v) Albumax I, 50 mg/L hypoxanthine, 25 mM NaHCO

3, 25 mM HEPES, and 10 mg/L gentamycin, and contained 2% hematocrit of O

+ erythrocytes (supplied by Wuxi Blood Center, Wuxi, Jiangsu, China). Parasite cultures were maintained at 37 °C under an atmosphere of 5% CO

2, 5% O

2, and 90% N

2, as previously reported [

21]. Parasites were routinely synchronized via two consecutive treatments with 5% sorbitol, and late-stage parasites were purified using 40/70% Percoll density gradient centrifugation. Parasitemia was quantified microscopically using Giemsa-stained thin blood smears.

2.5.3. Asexual Growth Inhibition Assay

A 3-day SYBR Green Growth inhibition assay was conducted based on the 3-day SYBR Green I method for the determination of the IC50 value. Specifically, 100 μL of ring-stage parasites obtained from sorbitol synchronization were incubated in a 96-well plate at 0.5% parasitemia and 2% hematocrit. Cultures were incubated with 2-fold serially diluted compounds ranging from 6.25 to 500 μM in a total volume of 200 μL for an additional 72 h under normal conditions. Then, 100 μL lysis buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl, 7.5 mM EDTA, 0.12% saponin, and 0.12% Triton X-100) containing 5 × SYBR green I was added to each well. Parasite cultures were lysed and stained in the dark for an additional 2 h at RT, and parasite-related fluorescence was monitored via a microplate reader with excitation and emission wavelengths at 485 nm and 530 nm, respectively. Each plate contained a vehicle-treated control and a negative control (erythrocyte only at 2% hematocrit) for background subtraction, and the growth inhibition assay was performed by two independent experiments with technical triplicates each time. IC50 was calculated by fitting the data with a nonlinear regression curve using GraphPad Prism 8.0.

2.5.4. Stage-Specific Antimalarial Assay

To assess the stage-specific antimalarial activity, parasites were subjected to double synchronization using 5% sorbitol at 40 h intervals. Following this, a 40/70% Percoll treatment was implemented, and the remaining parasites were cultured with fresh erythrocytes for 3 h to promote merozoite invasion. Highly synchronized parasites at ring (0–3 hpi), trophozoite (24 ± 2 hpi), and schizont (32 ± 2 hpi) were incubated with varied concentrations of the compound for 16 h in the 96-well plates at a starting parasitemia of 1%. The survival rate for parasites was determined at 72 h by the above-mentioned SYBR green I assay. The stage-specific parasite inhibition assay was performed in two independent experiments with technical triplicates each time.

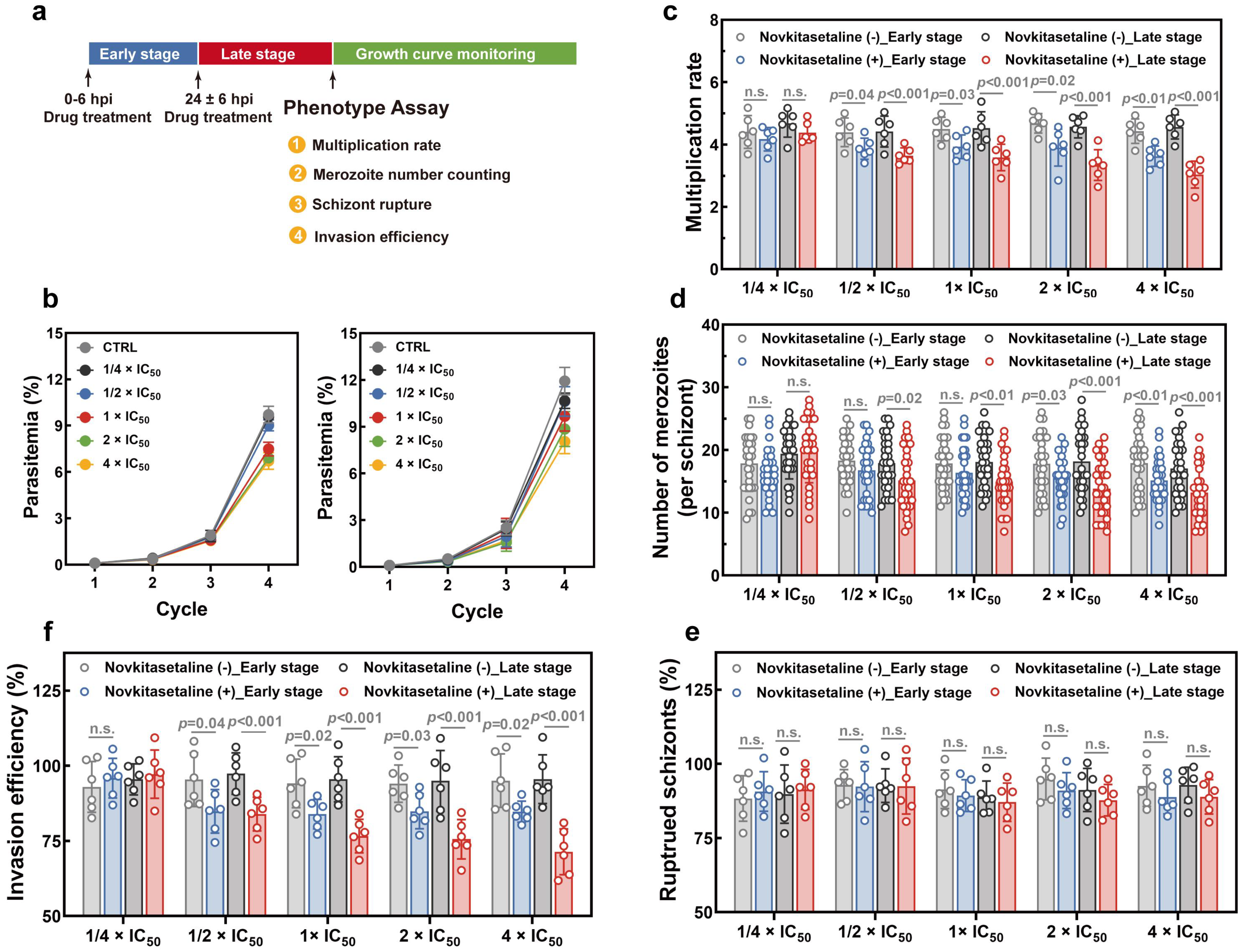

2.5.5. Asexual Parasite Growth Phenotype

To investigate whether treatment with the novkitasetaline could impair parasite growth during the intraerythrocytic development cycle (IDC), growth-related phenotypes were systematically determined, including growth curve, parasite multiplication rate, parasite egress, and invasion assays. Specifically, highly synchronized ring-stage parasites with ~6 h window were seeded at 0.1% parasitemia with 2% hematocrit in 24-well plate in the presence or absence of 1/4 × IC50, 1/2 × IC50, 1 × IC50, 2 × IC50, 4 × IC50 for 16 h at either early (0 ± 6 hpi) or late stage (24 ± 6 hpi). Novkitasetaline treatment was conducted one cycle prior to the phenotype assays. Following novkitasetaline treatment, cultures were washed twice with complete medium. Growth curves were plotted based on daily parasitemia assessed from Giemsa-stained thin smears. The multiplication rate of parasites was determined as the fold increase in parasitemia after each cycle. Three independent experiments with technical duplicates were performed for each experiment. Quantification of intraerythrocytic merozoites was conducted by microscopically counting 30 randomly selected schizont-infected erythrocytes.

For the egress-associated phenotype, the number of ruptured parasites was quantified following a standard protocol. Briefly, parasites were pre-treated with compounds for 24 h at the corresponding developmental stage prior to tight synchronization. Enriched schizonts by magnetic cell sorting were then co-incubated with red blood cells (RBCs) at 1% parasitemia and 2% hematocrit. After 12 h of incubation, the quantities of ring-stage trophozoites and schizonts were quantified by counting at least 5000 cells per experimental condition across randomly selected microscopic fields of Giemsa-stained thin blood smears. The number of ruptured schizonts and the average number of newly formed ring-stage parasites per ruptured schizont were calculated using the following formula: ruptured schizonts = [(parasitemia of schizont at 0 h) − (parasitemia of schizont at 12 h)]/(parasitemia of schizont at 0 h)

For the invasion-associated phenotype, the erythrocyte invasion assay was performed according to the previously reported protocol. Briefly, mature schizonts were purified by centrifugation on a 40/70% Percoll gradient, and enriched schizont-infected erythrocytes were counted by hemocytometer. 8 × 105 schizonts were mixed with fresh erythrocytes at a 1:50 ratio in 200 μL complete medium. Mixtures were added into 96-well plates with triplicate wells for each treatment and incubated under standard conditions for an additional 20 h. The invasion rate was quantified by microscopic counting of newly invaded ring-stage parasites in at least 50 microscopic fields.

2.5.6. Asexual Parasite Progression Assay

To analyze the arrested progression of parasites during the asexual stage, parasites were synchronized with two rounds of 5% sorbitol prior to assay. Synchronized ring-stage parasites were set up at 5% parasitemia, and the starting culture was divided into two aliquots. Half of the starting culture (ring stage parasites) was incubated with the compound at 2× IC50 in a 24-well plate to evaluate its effect on early-stage development. After 24 h, late-stage parasites progressed from the starting culture were similarly applied to evaluate the effect on late-stage development. After incubation, cultures were washed three times with complete medium to remove the compound, and the parasite progression was monitored during the following cycle. Thin blood smears were made at 4 h intervals, and microscopic analysis of growth arrest was performed by counting the number of newly invaded rings, as well as remaining trophozoites and schizonts in 100 parasites. The assay was performed in two independent experiments with technical duplicates each time.

4. Discussion

The deep exploration of the rich bioactive SMs from

Streptomyces is a major objective in current drug development [

1,

2,

3,

4]. However, this exploration is always hindered due to the severe disparity between laboratory culture conditions and the natural habitats of

Streptomyces strains, which in turn can suppress the expression of BGCs within strains and halt the production of SMs [

5]. Directly altering culture conditions to bridge the gap of strain growth involves manipulating numerous critical physical and chemical parameters, which is difficult to achieve in standard cultivation protocols. To circumvent these limitations and facilitate the SMs discovery, ribosome engineering was developed and applied in

Streptomyces research [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. This strategy is first performed by only selecting common laboratory antibiotics that target either the RNAP or the ribosome itself [

12]. Antibiotics such as rifampicin can be seamlessly integrated into conventional strain cultivation methods, without significantly altering medium composition or adversely affecting the cultivation operation [

12,

13]. Furthermore, all suitable antibiotics can be used quantitatively via concentration gradients in the medium to treat the target strains, thereby generating resistant mutants [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Thus, this overall procedure of ribosome engineering is relatively simple and convenient.

On the other hand, compared to traditional mutagenesis strategies, ribosome engineering has more defined targets: RNAP and ribosome, which are central to gene expression [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. The resulting antibiotic-resistant mutant strains of ribosome engineering always acquire mutations in RNAP or ribosomal proteins, leading to global adjustments in intracellular gene expression and activating the expression of silent BGCs [

6,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Finally, the optimized BGCs expression could initiate and enhance the production of SMs [

6,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Given these superior traits of ribosome engineering, it has been extensively employed in the research and exploitation of

Streptomyces, facilitating the discovery of diverse notable bioactive lead compounds [

6,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. In this research, to efficiently elicit the production of SMs in PRh3 under laboratory conditions, we treated it only with rifampicin, a common antibiotic used in ribosome engineering. These processes led to the screening of the optimal mutant strain PRh3-r55, which effectively produced JBIR-133 and JBIR-134. This activation of β-carboline alkaloids biosynthesis in DXWR-derived PRh3 also further validated that ribosome engineering was a simple but effective strategy in

Streptomyces SM development. Crucially, ribosome engineering can significantly enhance the efficiency and scope of both research and utilization of

Streptomyces strains, thereby enabling the exploitation of numerous

Streptomyces strains isolated from natural habitats [

12,

13,

14,

22,

23]. Moreover, the diverse mutants generated by ribosome engineering, with upgraded intracellular BGC expression and improved SM profiles, may also provide new foundations to drive the continuous investigation.

Meanwhile, heterologous expression serves as another valuable strategy in

Streptomyces SM development [

30,

31]. This strategy capitalizes on the continual progress in efficiently refactoring BGCs into amenable hosts, ultimately leading to successful BGC expression for biosynthesizing various SMs [

30,

31]. In the present research, unexpected difficulties in genome sequencing prevented the identification of β-carboline alkaloid BGC in PRh3. Consequently, we employed an alternative strategy by cloning the

ksl, responsible for JBIR-133 and JBIR-134 biosynthesis, and introducing it into PRh3-r55 for heterologous expression. The efficient expression of

ksl, coupled with ribosome engineering-improved intracellular environment in PRh3-r55, created a synergistic and iterative effect. This effect not only significantly enhanced the yield of JBIR-133 and JBIR-134, but also enabled the production of two sulfur-containing β-carboline alkaloids, including the new molecule novkitasetaline. These combinatorial practices underline that utilizing metabolically engineered hosts in conjunction with well-characterized BGCs can effectively facilitate the discovery of new NPs. Recently, a tremendous diversity of BGCs has been continuously identified from

Streptomyces [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. In parallel, ribosome engineering can steadily generate various

Streptomyces hosts [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Therefore, integrating these two strategies can expand the scope for BGCs expression, enabling the deep mining of natural products and ensuring the full utilization of genetic resources.

β-carboline alkaloids, featuring a planar tricyclic pyridoindole ring system, constitute an extraordinary family of N-heterocyclic compounds widely distributed in plants and microorganisms [

26,

27]. Natural β-carboline alkaloids have exhibited potent antimalarial effects against diverse

Plasmodium strains [

26,

27,

28]. Thus, isolation and identification of new β-carboline alkaloids not only directly provide candidate antimalarial lead compounds, but also offer unique structure features to guide subsequent rational drug design and modification. In the present study, we obtained the new sulfur-containing antimalarial novkitasetaline, which exhibited a relatively broad antimalarial activity against both drug-sensitive and drug-resistant

P. falciparum strains. Moreover, differences in drug sensitivity among developmental stages of

P. falciparum have been reported as one of the potential mechanisms for the emergence of antimalarial drug resistance [

29]. Thus, additional quantitative assessments of stage-specific drug sensitivity have been performed to investigate the mode of action (MOA) of novkitasetaline. Notably, in contrast to the 72 h growth inhibition assay, a similar growth profile as well as IC

50 values have been obtained regardless of the

P. falciparum strains. Late-stage parasites exhibit significantly higher sensitivity than early-stage parasites. Given that late-stage parasite proliferation is associated with the progression of the parasite’s IDC, this finding strongly indicates that exposing late-stage parasites to novkitasetaline can markedly impair parasite normal developmental processes. Detailed growth phenotype assays have confirmed that exposure to novkitasetaline at the late developmental stage significantly halts the parasite’s progression, in which both a notable reduction in the number of newly invaded ring-stage parasites and an increase in the accumulation of arrested schizont-stage parasites have been observed. Meanwhile, the reduced number of merozoites per schizont further indicated that exposure at the late stage can remarkably disrupt parasite development. Furthermore, invasion/egress assays provided additional support for this conclusion, confirming that novkitasetaline exposure impairs parasite development rather than interfering with schizont rupture. Collectively, our results demonstrated that novkitasetaline exerts its antimalarial activity by targeting

Plasmodium growth processes.

Traditional antimalarials are classified as fast-acting drugs that can eliminate the vast majority of parasites within a short period. For example, artemisinin and its derivatives generate reactive oxygen species upon activation, which exerts a lethal effect on parasites [

32]. Additionally, quinoline antimalarials act by inhibiting hemoglobin-degrading enzymes, thereby leading to the accumulation of toxic heme that ultimately kills the parasite [

33]. However, due to the relatively high selection pressure imposed by their mode of action, these agents are prone to developing drug resistance [

34]. It has been reported that targeting key transcriptional factors or proteins associated with parasite progression represents a promising strategy for developing novel antimalarials with reduced propensity for resistance evolution [

35]. Among potential targets, tubulins, a core component of microtubules, have emerged as possible candidates for inhibiting parasite growth [

36,

37]. Disruption of tubulin function, whether via destabilizing or stabilizing compounds, triggers parasite growth arrest or developmental impairment. Notably, several alkaloid compounds (e.g., colchicine alkaloids and vinca alkaloids) have been identified as tubulin destabilizers [

38]. Given the structural similarity between novkitasetaline and these alkaloids, we hypothesize that novkitasetaline exerts its antimalarial effect by disrupting tubulin function. Our results further support this hypothesis; for instance, parasite growth was more significantly impaired when exposed to novkitasetaline at the late stage. This is consistent with the fact that late-stage parasites undergo extensive morphological changes, during which microtubules play a critical role in forming and maintaining the mitotic spindle, an essential structure for chromosome segregation during cell division [

39]. Additionally, unlike compounds that interfere with parasite egress (e.g., ML10, E64), novkitasetaline only reduced the parasite multiplication rate and inhibited schizogony rather than blocking egress [

40,

41]. Notably, direct evidence linking novkitasetaline to tubulin targeting is currently lacking. This is partly due to its moderate antimalarial potency (weaker than traditional antimalarials) and the absence of commercially available

Plasmodium tubulin-specific antibodies.

While novkitasetaline exhibits relatively weaker antimalarial activity compared to commercially available antimalarials, its notable efficacy against drug-resistant parasite strains highlights its potential as a candidate partner drug in combating malaria drug resistance. This property positions it as a valuable starting point for addressing the critical challenge of resistance in current antimalarial therapies. To advance its potential, future research could focus on two key directions based on its structural scaffold, including the structural optimization and in vivo antimalarial evaluation. Guided by structure–activity relationship analyses, targeted modifications could be further implemented to improve its antimalarial potency. Based on these efforts, in vivo studies including assessments of pharmacokinetic profiles, efficacy in different animal models of malaria could be conducted to validate their translational potential. Furthermore, the novkitasetaline is a modified natural derivative of kitasetaline. The distinct structural features and bioactivity between these two compounds definitively validate that aromatic modification at the C-1 position of the β-carboline pyridine ring is critical for antimalarial efficacy. This structure-activity relationship aligns with earlier findings on marinacarbolines [

25,

28], offering valuable insights and reference for future antimalarial drug design and development.