Abstract

The control instructions of industrial control systems are prone to threats such as unauthorized access and tampering during transmission and interaction, and access control is a fundamental method to protect data security. Due to the cyber-physical integration and availability constraints in industrial control systems, existing access control methods cannot be directly applied. In this paper, we propose an access control policy for control instructions based on the ciphertext policy attribute-based encryption (CP-ABE) under the availability constraints in industrial control systems. First, we analyze the abnormal behaviors of control instructions in process industrial monitoring systems, and model the attributes associated with field control business and integrate them into CP-ABE to achieve fine-grained access control and avoid non-compliant operations. Second, we adopt a trusted computing mechanism to protect the identity trustworthiness of the transmission node; the confidentiality of the transmitted control instruction is guaranteed by the negotiated symmetric key and the key authorization is realized by the CP-ABE. We further optimize the measuring frequency of the trusted measurement and the deployment policy of the access control method to guarantee business availability. Finally, we conduct formal analysis and experimental validation of the proposed method, and the results show that the proposed access control policy can prevent unauthorized access and non-compliant tampering by industrial control devices and achieve trustworthy delivery of control instructions with controlled computational complexity.

1. Introduction

Industrial control systems are widely used in key industrial scenarios such as electric power, petrochemical, metallurgy, intelligent manufacturing, etc., playing the role of the central nervous system. Due to the important political and economic value, the continuous accumulation of vulnerabilities, and a large number of attack surfaces, industrial control systems are facing serious information security threats. The attack incidents of Iran’s nuclear facilities and Ukraine’s blackout have proven that the threat is real and the security protection of industrial control systems is urgent [1,2].

Industrial control systems have great differences compared with ordinary information systems. Firstly, data flow between physical devices and information devices, malicious operation, or mis-operation will have a huge impact on industrial field equipment. Secondly, the control business has extremely high availability and control operations do not allow interruption; for the security protection, availability > integrity > confidentiality—it is exactly the opposite of ordinary information systems, as the availability constraints ensure that information security methods such as complex encryption and access control, universal security routing, and updatable operating systems cannot be directly applied [3,4].

Data are an important asset of an industrial control system. Control instructions are the dynamic control data and associated parameters that flow during the monitoring and control process. Control instructions are vulnerable to threats such as unauthorized access and tampering, leading to control failures or errors. Access control is a basic method to protect data security. At present, a lot of research on access control methods has been carried out [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. However, establishing the access control policy of the industrial control system under the availability constraint is the key problem to be solved. Existing access control schemes have some problems in industrial control scenarios, and those are the following:

(1) The existing access control strategies lack the consideration of the availability constraint of the industrial control process. The access control requirements for industrial control systems mainly focus on standards such as IEC62443 [5], NIST SP-800-82 [6], and some suggested solutions [7,8,9], which have no specific implementation plans. The mainstream identity-based access control (IBAC) [10] method lacks restrictions on the operations behavior of industrial control businesses. Role-based access control (RBAC) [11] method lacks fine-grained operational limitations of heterogeneous objects in industrial control systems. Attribute-based access control (ABAC), e.g., Ruj [12], does not consider the heterogeneity of industrial control systems and does not apply to the data aggregation process from industrial hosts to field nodes. Zhang [13] proposed a SCADA data access control scheme based on identity proxy re-encryption. Chen [14] proposed an access control scheme based on trusted SGX. Li [15] proposed a fine-grained CP-ABE approach based on weighted attributes. Complex encryption mechanisms are effective but need to be adjusted in strong real-time scenarios, and lightweight access control policies should be used under the availability constraints of industrial control processes.

(2) Most of the access control mechanisms do not continuously follow up on the anomalous behaviors of the authorized objects. Gowdanakatte [16] applied attribute-based access control methods to PLC communication protocols. Cheminod [17] proposed attribute-based access control policies under the cyber-physical dual model. Tu [18] proposed a CP-ABE method with cloud-assisted decryption. These schemes do not consider the anomalous behavior of legitimate nodes, and the data are prone to be tempering or leaking after decryption by nodes with access privileges. Chiquito [19] identified the key attributes of ABAC and ABE and combined them for secure data sharing in industrial environments. Qi [20] proposed a CP-ABE and cloud-assisted optimization approach to protect sensing data in industrial IoT devices. Fan [21] adopted trusted TEE (Trusted Execution Environment) and CP-ABE to avoid the leakage of sensitive information from mobile devices, and Banerjee [22] adopted multi-attribute block-chain and CP-ABE to encrypt block data in the industrial Internet of Things, but none of these methods can avoid the abuse of privileges in the context of the cyber-physical fusion, where authorized identities and roles may do non-compliant damage to field devices.

There are some other attribute-based encryption (ABE) methods, such as KP-ABE [23], FH-ABE [24], and MA-ABE [25]. In the KP-ABE algorithm, the access control policy is embedded in the key, and the attribute set is associated with the ciphertext, which is exactly the opposite of CP-ABE. The KP-ABE is suitable for static scenarios and is not suitable for scenarios where data owners dynamically set policies for their data. The FH-ABE algorithm is an ABE variant that enhances privacy protection and aims to hide attribute information in ciphertext and keys. The MA-ABE algorithm supports collaborative management of attributes by multiple independent authorization agencies, which increases complexity and latency. These methods are not suitable for industrial control scenarios that require high availability and clear attribute information.

From the technology development trend, active defense technologies represented by trusted computing 3.0 [26,27] are a potential solution for information system security. In this paper, we propose to solve the access control problem of control instructions by integrating trusted computing and the CP-ABE method. We first utilize the trusted computing approach to authenticate the nodes to avoid identity forgery. We adopt the symmetric key negotiated by the Diffie–Hellman (DH) exchange protocol to protect the transmission process of control instructions, and the authorization of the key is restricted by the CP-ABE method to avoid the availability problem brought by the direct introduction of CP-ABE method. We model the business operation attributes of the industrial control process into the attribute-based access control method to identify the non-compliant operations of the field devices. The extracted attributes are used synchronously for the integrity metric of the computation node. Moreover, we update the key negotiation frequency and integrity measurement frequency according to the abnormal behavior and availability constraint of the industrial control system to avoid the abuse of privileges.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) We have added a dedicated and critical attribute for industrial control systems, that is business correlation attribute, to the CP-ABE algorithm to identify non-compliant operations of field devices, which was not considered in the previous work. We use the symmetric key negotiated by the DH method to protect the transmission process of the control instruction, and the encrypted key is authorized by the CP-ABE method to ensure that only recipients who satisfy the attributes can obtain a decryption key.

(2) We have introduced a trusted computing mechanism to solve the problem of property, parameter tampering, and leakage in traditional access control methods. Trusted authentication is to protect the trustworthiness of the computing environment and the nodes’ identity. The encrypted control instructions and their hash values, as week as negotiated session keys and related parameters, are stored into the PCR (Platform Configuration Register) of the trusted module to prevent unauthorized tampering.

(3) Compared to the previous work that did not adequately consider the availability constraints of industrial control systems, we have improved the access control scheme. According to the availability constraint, we dynamically adjust the access control policy of heterogeneous field devices and integrity monitoring frequency and realize the dynamic update of data encryption key to avoid privilege abuse.

Finally, we conduct formal analysis and experimental validation of the proposed method; the results show that the proposed access control policy can prevent unauthorized access and non-compliant tampering of industrial control devices and achieve trustworthy delivery of control instructions with controlled computational complexity.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 analyzes the anomalous behaviors of control instructions in industrial control networks; Section 3 proposes a fine-grained access control policy for industrial control systems; Section 4 is the theoretical and experimental analysis; and finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Abnormal Behaviors of Control Instructions in Control Networks

2.1. Industrial Control Scenarios and Control Instructions

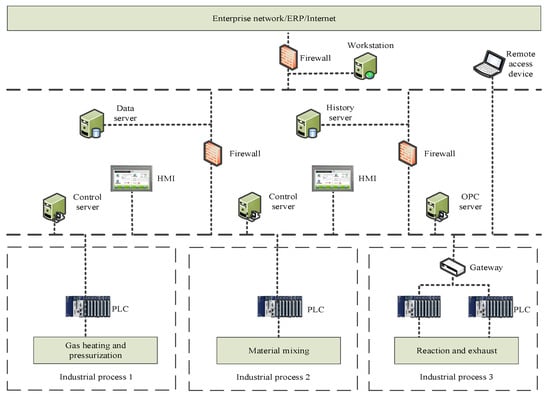

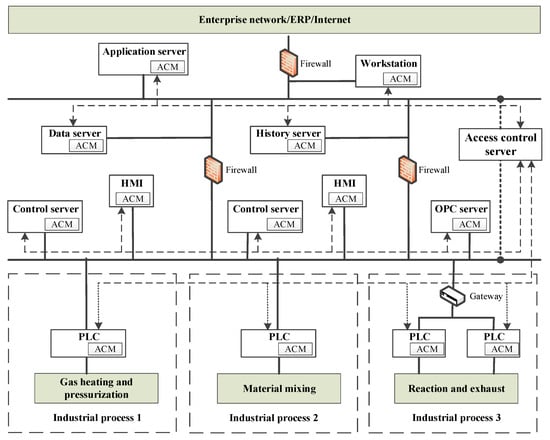

First, we give a scene as follows: take the oil and gas separation operation of the process control system as an example; gas heating and pressurization, mixing, reacting, and exhausting are carried out in sequence, and the processes are controlled by the monitoring system individually or compositely; its basic structure is shown in Figure 1. The monitoring system includes workstations, HMIs, control servers, database servers, OPC servers, PLCs, etc. PLCs directly connect to the site for direct control, e.g., temperature and pressure adjustment of gas heating and pressurization. The control server monitors the status of the PLCs and adjusts the control instructions, e.g., changing the control parameters of gas heating and pressurization. The HMI collects the data of each device in the monitoring system, e.g., the data change curves of temperature and pressure, and displays them to the operator. The database server stores a large amount of real-time and historical monitoring data. The workstation can view the control view, modify, and send configuration commands. The OPC server is mainly used for protocol conversion to convert the monitoring data into data that can be recognized by the on-site network.

Figure 1.

Basic architecture of process industrial control system.

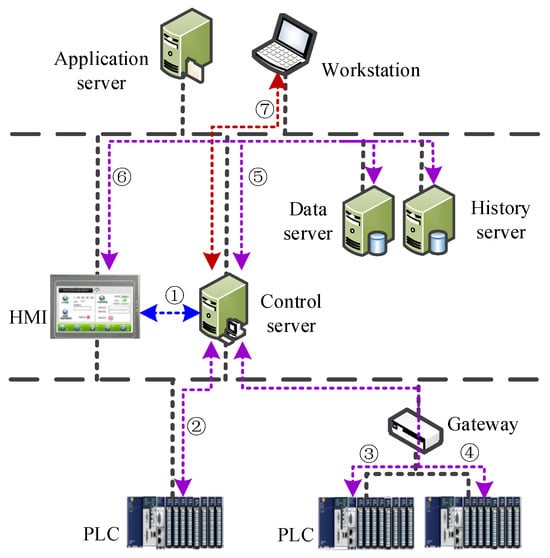

Control instructions are the data that flow in the controller, control server (also called host computer), HMI, data server, and workstation, including configuration information, control commands, data view request commands, etc. We give an example of control data flow, as shown in Figure 2. The figure shows the data flow with numbering—No. ① indicates the data exchanged between the control server and HMI for display, configuration of control instructions, and human–computer interaction. In some control systems, the HMI is integrated into the control server. No. ② indicates the data exchanged between the control server and the controller PLC; for PLC configuration, control commands sending and receiving, this interaction is the most important. Some PLCs are connected to the control server through switches or field buses (the data exchange method in No. ③ and No. ④) to realize distributed control. In the process of control decision-making, the control server sometimes needs to access the data of the data server or history server to assist in decision-making (the data exchange method in No. ⑤), e.g., querying the database to support fault diagnosis of the control device. The HMI also needs to display historical data and predict the development trend and needs to interact with the data server or history server (the data exchange method in No. ⑥). The data exchange in No. ⑦ indicates access to the control network from the engineer’s workstation. When the control strategy needs adjusting, the engineer sends a new command to the host computer, which adjusts the control and responds to the engineer. The data exchange between the HMI and the host computer, or between the database and the server is single-hop data. Configuration commands from the workstation to the PLC will involve multiple data streams (⑦② or ⑦①②). Device status data passed to the host computer will flow through multiple cascaded PLCs or gateway devices.

Figure 2.

Diagram of critical control command flow.

2.2. Security Threats and Access Control Requirements

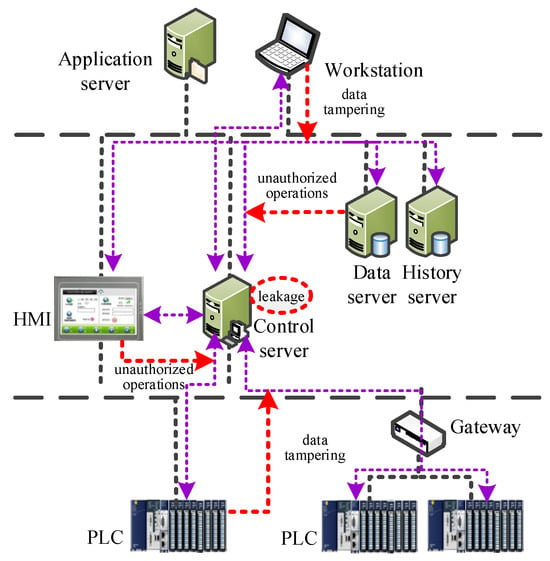

Control instructions face many threats, as shown in Figure 3. The main abnormal behaviors include the following:

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of critical data threats.

Unauthorized manipulation: the data originator, transmitter, or receiver has exceeded their authority to access control instructions.

Instruction tampering: commands are intercepted or tampered with on the transmission path; authorized nodes may also tamper with the commands after decrypting them.

Instruction leakage: in the process of transit, fusion of auxiliary information, and protocol conversion, unauthorized nodes leak the instruction data. After authorized nodes decrypt the instruction, the instruction information may leak due to operating system vulnerability or malicious operation.

The real-time requirement of control instructions is high, and a lightweight access control method is required to avoid unauthorized access, tampering, and leakage of data. The mapping relationship between abnormal behaviors and access control policies is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Anomalous behavior and access control requirements of the critical control data.

3. Fine-Grained Access Control Policies for Industrial Control Networks

To realize the access control requirements in Table 1, this paper proposes access control strategies based on CP-ABE and trusted computing.

3.1. Preliminary Knowledge and Notations

CP-ABE method [12] mainly consists of the following steps:

Step 1: System initialization Setup (1λ). Let G, GT be two cyclic groups in which the order is a large prime number q. g is a generating element of G. Definition e: G × G → GT is a bilinear mapping. The hash function H: {0, 1}* → G describes the hash value of a user’s identity mapped to G. The hash function uses SHA-1. The authorization center A (access control server or intra-region sub-policy server) has a set of attributes L, A that randomly choose ai, bi ∈ Zq, Zq = {0, 1, 2, …, q-1}. The private key of the authorization center A is SK = {ai, bi, i ∈ L}. The public key of A is PK = {e(g, g)ai, gbi, i ∈ L}.

Step 2: Key generation and distribution. Node u receives a set of attributes I(u) from the authorization center, and a private key ski,u = gai H(u)bi corresponds to each i ∈ I(u). Note that all keys are passed to the target node through a secure channel, e.g., encrypted using SSH or the target node’s public key, and can be decrypted only by the node with the corresponding private key.

Step 3: Sender encryption Encrypt(M, R, π). The sender determines the access tree, extracts the LSSS (Linear Secret Sharing Scheme) access structure (R, π), and computes the ciphertext based on the input message M, the access matrix R, and the mapping relation π from the row vectors of R to the attributes. First, the sender chooses a random seed s ∈ Zq, a random vector v = (s, y2, …, yn) ∈ Zqn, n is the number of attributes in the access policy, and the first term is s. Then, the sender computes λx = Rxv, where Rx is the xth row of R. Also, the sender chooses a random vector w ∈ Zqn, with the first term 0, and computes wx = Rxw. Further, for each row Rx of R, the sender chooses a random number ρx ∈ Zq, and then computes the following parameters:

where π(x) is a mapping from Rx to attribute i. Finally, the sender assembles the ciphertext C = <R, π, C0, {C1,x, C2,x, C3,x, ∀x}> and sends it to the receiver, along with the access tree R matrix.

Step 4: Decrypt algorithm Decrypt(C, {ski,u}). The receiver u inputs the ciphertext C, the key {ski,u}, the group G, and outputs the message M. It first obtains the access control matrix R and the mapping π from C, and then performs the following steps:

First, u computes the set of shared attributes {π(x): x ∈ X} ∩ I(u) to obtain the intersection of the assigned attributes and the corresponding attributes of the access matrix, and X is the set of row vectors of the matrix R. Then, for each attribute of the set of shared attributes, it is checked whether there exists a subset X’ of the row vectors of R, such that their linear combination is equal to (1, 0, …, 0). If it does not exist, decryption is not feasible, and Decrypt(C, {ski,u}) = NULL. If it exists, the receiver computes the constants kx ∈ Zq that satisfy ; Kx is a vector of constants consisting of kx, x ∈ X’. Finally, the decryption computation proceeds as follows:

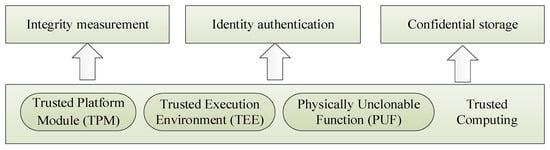

Trusted computing [23] is an active immune method and its basic function is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Basic functions of the trusted computing.

Integrity measurement: variable x (which can be an environment value, attribute value, specific value, etc.) has an integrity value of f(x). The hash calculation h(.) is a commonly used integrity calculation method, and f(x) is stored in a trusted module. The trusted module (TPM) recalculates the variable x at a certain frequency (f2 in this article; f2 is an important parameter) to obtain f’(x), and determines whether its integrity value has been tampered with (f(x)? = f’(x)).

Identity authentication: authentication is implemented using TPM integrity metrics and remote proofs [23]. TPM reports AIK (Attestation Identity Key) certificates and AIK-based signatures of integrity metric values (h(x1), h(x2), …, h(xn)) to neighboring nodes, and the neighbor nodes certify the correctness of the certificates and signatures to complete the authentication.

Confidential storage: TPM stores the integrity measurement value in the PCR protected by the storage root key (SRK). TPM is physically tampering-resistant; it uses a nonvolatile memory to protect the EK, SRK, and PCR. It uses a secret area taking the SRK as a root for protecting the platform data outside the EK, and a sealed storage function is provided for protecting the data from unauthorized operation by the authorized user.

The notations used in this paper are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Notations.

3.2. Attribute Modeling and Non-Compliance Identification Incorporating Trusted Mechanisms

Attribute modeling is the key to attribute-based access control (including CP-ABE method), whose task is to find a set of attribute collections and formulate authorization relationships on the collections.

3.2.1. Generalized Attributes

Generic attributes generally include identity attributes, operation attributes, environment attributes, etc. The access attribute set Attr_Set = <ID, Act_Set, Env_set>, ID denotes the set of node identities, such as {PLC1, PLC2, control-server1, data-server2, …}. Act_Set denotes the set of operation behaviors for control instructions, commonly including read, write, relay operations, that is {read, write, relay}. Env_set denotes the set of environment attributes; the common ones include the node’s function, function {monitoring, field control}, and other restrictions.

3.2.2. Attributes of Business Relevance

Taking the oil and gas separation operation of the process control system as an example, the processes of gas heating and pressurization, mixing, reacting, and exhausting are in strict sequence within a cycle Tn.

Each process has a period, e.g., after completing the “mixing” period, it is handed over to the “reacting” period. Env_denote = {Nh, Nm, Nr} denotes the identifiers of each process. When the PLC finishes controlling the current process, it sends a handover signal to the control server, which starts or loads the control program for the next business process, and at the same time notifies all the currently connected nodes to update their identifiers.

Within a single process period, the operating status of the equipment shall be limited to the scope defined by the control program for that process. Pressurized operation (belonging to Nh) is not permitted within the period of mixing marked as Nm to avoid gas explosion.

There are two modes for industrial scenarios (as shown in Figure 1). When a single controller controls a single business process, devices within the data transmission range of a single business process only need to mark the current business flow Nxe ∈ Env_denote. When a single controller controls multiple business processes, the process markers on the devices need to be switched positively and instantly by the timing relation Nh → Nm → Nr → Nh within the processes cycle Tn.

The business process identifier is added to the Env_set as one of the factors of environmental constraints. The receiving node uses a monitoring mechanism to recognize if the current operation is constrained within the current process, thus allowing/warning the operation.

Another business correlation is spatial location. The monitoring system directly connects the physical site. The closer it is to the PLC, the greater the threat is to the physical site device from operations that violate the security policy (especially write operations). Control servers and PLCs need to be guarded against tampering with critical data to cause wrong control (e.g., maliciously closing valves).

The business relevance constraints are all reflected in the environmental attributes. We expand the set of environment attributes, Env_set= {function, Nxe, Lx}. Lx = {1, 0} denotes the relevance to the field operation, where 1 denotes relevance to the field operation and 0 denotes no relevance. Considering the spatial location, the data operation sent to the control server and PLC is to set Lx = 1. The associativity constraint avoids tampering of data by the control server and PLC by formulating an operation preemptive policy, e.g., the one that allows the authorized nodes to further manipulate the data only if the integrity metrics of the control program and critical instructions are passed and the operation behavior is in line with the predefined operation flow of the control code.

3.2.3. Identification of Business Relevance Anomalies

TPM and access control module collaborate to identify anomalies in business-related behaviors.

As mentioned earlier, Lx =1 indicates that the operation is directly related to the control business. Each process, such as gas heating and pressurization, mixing, reacting, and exhausting will have a set of control programs, and each set of control programs indicates a strict time sequence within the period, such as opening/closing/increasing/decreasing the valves, etc. TPM saves the integrity metrics of the control programs and verifies the integrity according to a certain frequency (f2). Once an anomaly occurs, it implies that there may be tampering of the data by the control servers and the PLCs; the TPM interrupts the operation process and submits it to the detection server to analyze the code logic relationships. Simultaneously, the access control module also monitors the execution process of each group of control programs with timing relationships within the process in real time. Once recognizing that critical control instructions violate the business timing, such as reading/writing programs segment that are not the current business segment, the module issues an early warning and interrupts the operation process.

Integrity metrics and compliance identification are also reflected in the attribute model. Let e1 denote the TPM’s integrity warning for control instructions; e1 =1 when without warning. e2 denotes the TPM’s integrity warning for the static control program; e2 =1 when without warning. e3 denotes the TPM’s warning indication for control instructions that violate the predefined operation timing of the segment of the programs within the period of the process and when without warning e3 =1. Then, the warning indications E = e1 e2 e3. When E = 1, access to the data is normal; otherwise, access is blocked. E is also an environment variable; the supplemented environment variable is Env_set_new= {function, Nxe, Lx, E}.

3.3. Identity Authentication and Data Transfer Incorporating Trusted Mechanisms

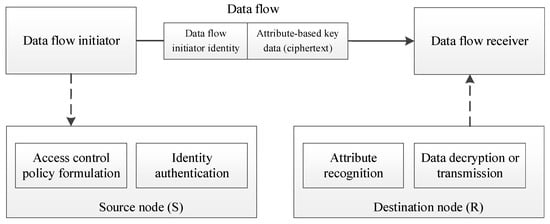

Without the loss of generality, the transfer process of the control command between two nodes is shown in Figure 5. Each node deploys an access control module for access function realization and communication interactions. When the data flow initiator is ready to send data, the resident access control module first authenticates the identity information of the data initiator and the connected network node, and only valid identities are added to the routing list to avoid the data being sent to the revoked node. Then, the initiator formulates the attribute-based access control policy (CP-ABE method) for the data. The access control module of the receiver performs attribute matching and identification, and only the node that has the attribute policy defined by the sender can obtain the decryption key to decrypt the data. If it is an intermediate node, it continues to deliver the data.

Figure 5.

Data transfer model.

Due to the node stability of the industrial control system, it is not necessary to perform authentication at every interaction. Authentication is required at the beginning of the establishment of the industrial control network, when a new node joins, or when a node that is not in the access control list due to revocation of privileges re-initiates a connection request. To prevent tampering by the operating system, authentication is implemented using TPM integrity metrics and remote proofs [23]. The TPM reports AIK (Attestation Identity Key) certificates and AIK-based signatures of integrity metric values (h(x1), h(x2), …, h(xn)) to neighboring nodes, and the neighbor nodes certify the correctness of the certificates and signatures to complete the authentication. After all the nodes pass the authentication by the above method, the data transmission starts.

Data transmission combines the Modbus protocol [5]; node a transmits data Md {C, h(data), Tv, (R, π)} to the target node d. C is the ciphertext encapsulated by the CP-ABE algorithm, in which the plaintext M = MK (data). MK (data) denotes the data encapsulated by the Modbus protocol and encrypted with the session key K between node a and node d adopting symmetric encryption method (e.g., DES or AES). The key update frequency f1 is fixed or updated on demand, and the maximum frequency is one cryptogram at a time. h(data) is the hash value of the data. Tv = h(K) ⊕ Tmod denotes the authentication sequence number, h(K) denotes the hash value of the session key K, and Tmod denotes the checksum value that comes with the Modbus protocol. (R, π) is the LSSS access structure formulated by node a. Node d receives and extracts the Modbus protocol data by the access control privileges and calculates the data hash value to verify the data integrity. When there is an integrity verification exception or synchronization exception, node d verifies Tv. When the verification fails, the data are retransmitted. When the verification fails again, the request is re-initiated and identity verification is performed, at which time the session key in Tv needs to be updated synchronously. The same method is used to transfer data from node d to node a.

Notice that, considering the high availability for instructions transmission in industrial control networks, the sender encrypts the transmitted data using a set of shared session keys that have been negotiated in the authentication phase using an end-to-end encryption method, MK(data) = EnK(data), and the key K is the encryption key. The core of TPM is memory sealing and remote authentication. The TPM stores the negotiated key K and its generating parameter, the public key, and the decrypted commands and their integrity metric values in the PCR isolation zone to avoid unauthorized access by the host operating system.

3.4. Access Control Policy Optimization Under Availability Constraints

We deploy an access control server on the monitoring network bus and deploy the access control module-integrated TPM on each node of the industrial control network. The access control server monitors the node and network status and adjusts and optimizes the access control policy when the deployed policy affects the availability of the industrial control system.

3.4.1. Availability Constraint Problem

Time delay is a key factor in the availability constraints of control instructions and control functions, and industrial control systems require that control cycles and data acquisition be within acceptable delay; the time delay of a control cycle includes intra-node access control processing overlay delay and inter-node transmission overlay delay. Let the set of industrial network nodes through which business data flow in a single control cycle be N1 = {N1, N2, …, Nm1}; m1 is the number of nodes, the computation time of the access control deployed by the i-th node is ta(i), the original business processing time is tb(i), and the total computation time is tcal (i) = ta (i) + tb (i). When the command instruction is transmitted from the source node to the target node, the transmission time of the access control is tc(i), and the original service transmission time is td(i). The total transmission time is tcom(i) = tc(i) + td(i). A single control cycle (e.g., control instruction transmission, processing, and feedback) consists of multiple processes at multiple nodes, so the time delay of a single control cycle is . N1 is the set of nodes involved in the control cycle. An access control policy can be deployed to a target node when t < tmax. tmax is the maximum delay allowed for a control cycle.

3.4.2. Access Control Policy Optimization

The policy optimization includes the following three aspects: optimization of policy deployment location and intensity, optimization of session key update frequency, and optimization of the frequency of integrity metrics of TPMs on target programs or key attributes.

TPMs are deployed in network nodes in a parallel manner and some PLC devices have limited energy, which is not suitable for deploying TPM chips. In this case, the authentication at the beginning of PLC access is implemented by the control server (host computer) by proxy. The PLC adopts the host computer’s AIK key to sign the PLC’s integrity metric value (h(x1), h(x2), …, h(xn)), and then reports the platform integrity to the host computer at a frequency; the host computer verifies the signature and compares integrity value with the first pre-stored one to determine whether it has been tampered with. The PLC directly loads the attribute-based access control set <{ID}, {Act_Set}, {function, Nxe, Lx, E}> to implement access control to the control program in the PLC and the passed control instructions. The PLC does not participate in the CP-ABE/decryption process, and the host computer passes the control commands stored in the TPM to the PLC in a symmetrically encrypted way to avoid leakage and tampering of the Fieldbus.

Optimization of key update frequency f1: f1 is defined as the number of updates per unit time. Let the number of command interactions per unit of time be nt; the one-at-a-time protection is the best, but it is difficult to satisfy the delay constraint; if the key is not updated for a long time it will lead to information tampering and leakage. We set the key to be updated when anomalies are detected, assuming that the average number of finding anomalies is nrec (nrec < nt), and updating the key before detecting the threat can guarantee the protection effect. Therefore, we establish the optimization constraint rule as follows:

We deploy a complete access control mechanism, randomly select the instruction transmission path, and compute Equation (4); if the delay constraint is satisfied, the optimal solution of Equation (3) is one secret at a time, f1 = nt. If Equation (4) is not satisfied, we need to find a lower bound on f1 that ensures the protection effectiveness.

The industrial control system is more stable than the Internet system; we consider the worst case of Internet packet loss, assuming that each packet loss can be found. The average number of abnormalities nrec obeys the Pareto distribution, the cumulative distribution function (CDF) is , where α is a Pareto parameter, it is in line with the empirical distribution of the historical statistical values of the anomalies’ number; the complementary CDF of nrec is , assuming that is negligible, and hence the average number of anomalies found in the worst case is . Since f1 < nrec and the number of instruction interactions is integer, min f1 = nrec + 1 under satisfying the delay constraint. ε is chosen according to the system preference, and f1 = 11 when α = 2 and ε = 0.01. If Equation (4) is still not satisfied when f1 takes the lower bound, we optimize the DH key negotiation process as follows: a set of negotiation keys {K1, K2, …, Ktn} is generated at the beginning of the communication establishment, and when an exception occurs, we firstly select the keys that were not randomly used before (set the random index) from the key list to be used for the instruction transmission, which avoids repeating the negotiation process, and further reduces the time delay. To avoid exhaustive attack, we set a forced update period Tmax, which updates a set of negotiation keys for the next batch of instruction transmission during the gap period of instruction transmission.

Optimization of TPM monitoring frequency f2: f2 is defined as the number of times the target object is monitored per unit time. The monitoring process includes reading the target program, computing the hash value, calling the hash value in memory for comparison, and feeding back the results. Due to the dual architecture of trusted computing, the additional delay of TPM monitoring on the target program is mainly the interaction with the interface program, which is negligible in comparison with the encryption operation. From the viewpoint of defense effect, f2 should be as large as possible. f2′ s lower bound must cover anomalies, i.e., nrec + 1< f2 < fnor, where fnor is the regular monitoring frequency of TPM. When Equation (4) does not meet the requirements but is close to the set delay, f2 can be reduced (e.g., by 50%, but must be greater than nrec + 1) to reduce the delay.

3.5. Access Control Implementation Steps

The steps of the proposed access control method integrated with trusted mechanisms are as follows:

Step 1: Initialization. The access control server records the node identity (ID) when it connects to the access control module of each node in the domain and extracts the access attribute set Attr_Set = <{ID}, {Act_Set}, {Env_set}>. Node u receives a set of attributes I(u) from the access control server and a private key ski,u = gai H(u)bi corresponding to each i ∈ I(u) (see Section 3.1). All keys are delivered to the nodes using SSH encryption during the system initialization phase. Each node pair negotiates a set of session keys using the DH method, and the related parameters are also transmitted to each node using SSH encryption, key K, and its related parameters are stored in the PCR of the TPM.

Step 2: Access control policy formulation. The message sender formulates an access control policy based on the desired access attributes of the data. For example, policyi = <PLCi ∈ ID, write/read, {field control, Nh, Lx =1, E = 1}> is an access control policy indicating that the PLC node with identity i can read or write critical data in the field control operation of gas heating and pressurization. The access that satisfies the policy conditions is Permit, otherwise Deny. The message sender extracts the LSSS access structure (R, π) based on the formulated access control policy, R is the access matrix, and π is the mapping relation from the row vector of R to the attributes.

Step 3: Trusted platform startup. The node runs the TPM platform and measures the integrity of the node’s environment. The attributes used for authentication are (h(x1), h(x2), …, h(xn)), which include the version number of the platform control program, the code function division parameter, and the attributes associated with the control code {function, Nxe, Lx, E}, and stores the integrity metric in the PCR register of the TPM platform to realize the isolated management of sensitive data.

Step 4: Data sending. The resident access control engine first authenticates the identity of the data initiator and the connected network node using TPM and adds valid identities to the routing list. The message sender encrypts the instructions to be transmitted using a negotiated shared key MK(data) = EnK(data). Further, the message sender computes the ciphertext based on the access structure (R, π) using the Encrypt(K, R, π) algorithm in Section 3.1, assembles the ciphertext C = <R, π, C0, {C1,x, C2,x, C3,x, ∀x}> and sends data Md {C, h(data), Tv, (R, π)} encapsulated by the Modbus protocol to the receiver. The PLC sends and receives data according to the optimized scheme (see Section 3.4.2).

Step 5: Data reception. When the receiver is the target node, its resident access control engine first authenticates the identity information of the data initiator and the previous hop node on the first connection, and the connection is broken if the authentication fails. After authentication, the receiver extracts the access structure (R, π), queries its own attribute set and attribute values (including the attribute values formed by the result of the TPM’s metrics on the integrity of the instruction data and control program, as well as the result of the expected operation of the control instruction) to see if they satisfy the access control policy set by the access tree, and interrupts the transmission if not satisfied. When satisfied, the receiver executes the decryption algorithm Decrypt(C, {ski,u}) to authorize access to the key K in the PCR. Then, the receiver decrypts data data= DeK (MK (data)) using the symmetric key K. It synchronously verifies the integrity of data and K in Md and alerts for tampering. When the data flow through the intermediate node, there are two cases: one is that the data need to be manipulated, for example, the host computer needs to perform some operation or processing of the instructions from the workstation with the data from the database, and then send it to the PLC. In this case, the host computer has the attribute privilege to decrypt and process the data in the TPM isolation zone and encrypt them to be sent to the PLC. The other case is that the data do not need to be manipulated; data are flowed directly to the next node as directed by the routing table.

Step 6: Access control policy optimization. The access control server monitors the node and network status and computes the time delay of each access control process. If the deployed policy affects the availability, then the server optimizes the access control policy as follows: optimization of session key update frequency, and optimization of the frequency of integrity metrics of trusted TPMs on target programs or key attributes. The server randomly combines the above strategies until the availability meets the requirements and further observes the abnormal conditions of the control program.

4. Theory Proof and Analysis of the Proposed Method

4.1. Formal Security Analysis

For the anomalous behaviors in Figure 3 and Table 1, we analyze the access control methods to identify and protect against unauthorized access, tampering, and leakage of control instructions of industrial control systems.

4.1.1. Security Model

Threat model: adversaries are mainly the attacked internal nodes (such as compromised PLCs, maliciously manipulated workstations). There are also some external nodes (maintenance nodes or wireless nodes) that implement unauthorized access. All nodes are untrusted. They are controlled to carry out unauthorized access, tampering, and leakage of control instructions at different locations and stages of data transmission in the industrial control network. The methods used by adversaries include forging credentials, malicious interruptions, man-in-the-middle, etc.

Assumptions: The device is reliable (functional failure is not considered), the communication channel is reliable, the TPM and associated TEE are trusted, the nodes in each layer of industrial control system have no security boundary, and the security boundary between layers is the firewall, which is also untrusted.

There is an adversary A that builds the following five models from three categories in polynomial time.

- Unauthorized (ID, C, Re, and W): A performs a read (Re) or write (W) operation on the control instruction C using the identity ID, and the attack is successful if it escapes detection by the access control system. This model includes the following three scenarios:

- Game 1: A forges an identity ID and impersonates a legitimate user to access control instruction C.

- Game 2: A has a legal identity, performs an unauthorized read or write on control instruction C.

- Game 3: A has a legitimate identity and has access to C, but performs a non-compliant write operation on C.

- Tamper (C, c1, and c2): A uses legitimate identity ID to tamper with the control instruction C; if it is not discovered by the access control system, then the attack is successful. A typical case is that A has a legitimate identity and has access to C; A tampers with the control instruction so that the hash value c1 of the data before tampering is the same as the hash value c2 of the data after tampering.

- Reveal (C): A has a legitimate identity and has access to C. A reveals control instructions C or critical data during the interaction. If it is not discovered by the access control system, then the attack is successful.

4.1.2. Formalized Analysis of Security Characteristics

Suppose that A is an adversary and B is a challenger. We describe the security of some of the techniques in access control through a set of challenge-response games.

- TPM non-clonability: TPM is unclonable and its challenge-response game is described as follows:

- Initialization: A sets the set of identity attributes according to the access control policy, and challenges B.

- Setup: B initializes access control processes, such as identity and attribute authentication.

- Query: A randomly selects a set of challenges {C1, C2, …, Cn}, e.g., a set of legitimate identities, with a polynomial number of times, and obtains B’s output response {R1, R2, …, Rn}, e.g., a set of authentication results, as training.

- Challenge: A chooses a challenge Cx that has not been asked before, such as a fake identity, and sends it to B.

- Guess: A outputs a guess Rx’ for B’s response Rx =TPM(Cx); if Rx’ = Rx, A wins the game, and A’s advantage in winning this game is denoted as Pr[Rx = Rx’].

A wins the game, which implies that the attacker knows the TPM processing through multiple queries, and A can impersonate B’s identity attributes. Since the TPM is physically secure (from large number decomposition difficulty) and non-cloneable (unique AIK key), A wins the game by an advantage ε1= Pr[Rx’ = Rx] and ε1 is negligible. TPM’s non-clonability guarantees the integrity and confidentiality of the authentication key, integrity metric attributes, negotiation keys, and its parameters stored in the TPM.

- DBDH (Decisional Bilinear Diffie–Hellman) assumption: the algorithm of CP-ABE is based on the DBDH method. An algorithm has an advantage ε2 in solving the DBDH problem in G. We say that the DBDH assumption holds if no polynomial algorithm has a non-negligible advantage of at least ε2 in solving the DBDH problem.

- Confidentiality of negotiation key K: unauthorized node A tampers with or leaks control commands by obtaining the negotiation key K. The challenge-response game is described as follows:

- Query: A asks for the negotiated key by training a set of encryption and decryption processes.

- Challenge: A sends plaintext (M0, M1) as a challenge, B chooses a random number c’∈ {0, 1}, computes the ciphertext of the challenge, and sends it to A.

- Guess: A guesses a random bit cg’ of c’. A wins the game if cg’ = c’.

According to the DH large prime decomposition difficulty, A cannot obtain the private key of the negotiation key, i.e., the ciphertext is indistinguishable. A can also randomly guess K. Assuming that the key length is N, A can guess q times, and the probability of guessing correctly is ; N is a large prime and can be ignored, so the advantage of A’s successful guessing is ε3 = ε2 + , and ε3 can be ignored.

- Pseudo-random function assumption: the integrity metric values of critical data and identity attributes are computed using pseudo-random functions. A pseudo-random function is defined as PRF as follows: {0, 1}k × {0, 1}* → {0, 1}k’, {0, 1}k is the secret security parameter, {0, 1}* is the message, and assuming that h is a pseudo-random function, the probability that A distinguishes between h or the true random function (random {0, 1}) is + ε4, and ε4 is negligible.

4.1.3. Security Proof

Lemma 1.

Probabilistic polynomial adversaries cannot gain access through identity forgery.

Proof.

The proposed access control methods perform mutual authentication by the TPMs, and the identity proof is realized by the AIK certificate and signature of the integrity values (h(x1), h(x2), …, h(xn)) in the PCR by the AIK. Due to the uniqueness of the AIK, the non-clonability of the TPM, and the pseudo-random function assumption, the adversary is unable to obtain the legitimate AIK or integrity metric values, and the advantage of the forged identity to pass the authentication is ε1, and ε1 is negligible. □

Lemma 2.

The adversary’s advantage in Game 2 is the same as in Game 1.

Proof.

A has a legitimate identity and performs an unauthorized read or write to C. The CP-ABE-based approach matches the access attribute, and when the match fails, the adversary advantage is zero. Another approach for A is to break the CP-ABE approach, which requires solving the DBDH puzzle, and it has been proved in the literature [21] that the adversary’s advantage is . Since Game 2 has a legitimate identity and more information than Game 1, the adversary’s advantage is not lower than that of Game 1. So, the advantage is the same as Game 1. □

Lemma 3.

The adversary’s advantage in Game 3 is the same as in Game 2.

Proof.

A performs a noncompliant write operation on C; the operation is matched by the access control rule, i.e., all fields of function, Nxe, Lx, E, are strictly matched, and when the match fails, the adversary’s advantage is zero. Since Game 3 has more information than Game 2, the adversary’s advantage is not lower than that of Game 2. Thus, their advantage is the same. □

Lemma 4.

The adversary cannot synchronously tamper with critical control instructions and their hashes.

Proof.

The data structure of the control instruction is Md {MK (data), h(data), Tv, (R, π)}; the data integrity is protected by a hash value and an authentication sequence number Tv = h(K) ⊕ Tmod. Individual tampering of instructions, associated control codes, or encryption keys by an adversary would be detected by the integrity metric mechanism. An adversary may tamper with control instructions and their hash values synchronously, and the adversary needs to know the structure of the hash function. According to the pseudo-random function assumption, the probability that A succeeds is + ε4—ε4 is negligible, whereas is the probability that A guesses directly and correctly. Therefore, an attacker cannot construct an input in a polynomial number of times such that the hash of the output is the same as the hash before data tampering. The adversary may also tamper with the negotiation key K and its hash value. K is built on a public key regime, and the advantage of cracking it is ε3, which is negligible in polynomial time. A can also impersonate a legitimate node to re-establish the negotiation key, and A passes the authentication with the advantage of ε1. Thus, A tampers with the control command and its hash value with the advantage of ε5 = ε4 × ε3 or ε5 = ε4 × ε1, which is negligible since ε << 1. □

Lemma 5.

Third-party adversaries are unable to leak critical control commands and the leakage behavior of receiving nodes is controlled.

Proof.

The critical control instructions are protected by the key during the delivery process, the third-party nodes cannot obtain and leak the critical control instructions, and the advantages of forging, modifying, and cracking the negotiated key can be ignored according to Lemma 4. The key is stored in the PCR of the TPM when it is delivered to the receiver, which prevents the receiver from leaking the control instructions before the authorization judgment, and the advantage of cracking the TPM can be ignored. After authorization, the node decrypts the critical control instructions, and the TPM strictly monitors the reading, writing, and passing of the instructions; once the malicious behavior (e.g., leaking to other nodes) occurs, the access control module will revoke the access privileges and require updating the negotiation key to ensure the confidentiality of the next control instructions. □

Therefore, the proposed access control method can avoid unauthorized and non-compliant attacks and tampering with control instructions on the above security assumptions; also, the leakage behavior can be controlled.

Table 3 compares the security features of existing access control methods related to this paper.

Table 3.

Comparison of security functions of various methods.

Ruj method [12] is an access control method that integrates CP-ABE and homomorphic encryption for industrial control systems. Fan method [21] is an access control method that integrates CP-ABE and trusted TEE. Chen method [14] is an access control method based on trusted TEE. Cheminod method [17] is an access control method that maps the logic of the field network tasks in industrial control systems, and the Zhang method [13] is a transmission authentication method for industrial control systems. Except for the Cheminod method, which considers task logic, none of the other existing methods consider non-compliant operations. In the table, “√” indicates that the function is available, and “×” indicates that it is not available. The tampering and data leakage is implemented under the condition that A has a legitimate identity and has access rights to C. As can be seen from the table, the proposed method is relatively more comprehensive in terms of security features.

4.2. Performance Analysis

The deployment of access control inevitably brings about performance impacts, which can be measured in terms of computational complexity and the impact of policy adjustment.

Lemma 6.

The additional computation of the proposed access control policy increases linearly with the network nodes, and the storage and transmission additions are constant.

Proof.

The computation of the proposed access control method consists of the following four parts: key negotiation, trusted measurement, transmission data processing, and access control. The computation amount of key negotiation consists of 1 computation of the public key and 1 computation of the session key, with the maximum value of 2p × p3, where p3 is the computation amount of one scalar multiplication and p is a large prime. TPMs are deployed in parallel with host computers. The computation amount of the integrity metric value per unit time is f2 × n × (h + 1), f2 is the metric frequency of the TPM, n is the number of attributes, and h denotes the computation amount of the one-time hash operation. The authentication computation is 2tasy, including the computation for sending authentication and receiving the other party’s authentication, and tasy is the computation amount of one public key encryption and decryption. Since the TPM deployment and authentication are one-time, in the regular operation after completing the authentication, the computation amount is f2 × n × (h + 1). The transmitted data are Md{MK(data), h(data), Tv, (R, π)}, containing one symmetric encryption (0.5tsy, tsy is the computation amount of one symmetric encryption and decryption), two hashes (2h, h denotes the unit computation of the hash operation), one integrity check (equals to h), and one Xor operation (x, x denotes the unit computation of the Xor operation). In the access control phase, in addition to the computation of CP-ABE with tasy, it also includes attribute judgment. From the computational point of view, judging whether the attribute is the same requires 1 time of the Xor operation, and the maximum computation is 9 times of the Xor operation (9x, including seven attributes, where E is determined by e1, e2, e3 respectively). After the access rights are satisfied, symmetric decryption is performed, including session key computation (2p × p3, which can be computed in advance) and symmetric decryption (0.5tsy), as well as the ongoing integrity judgment of the TPM for l targets (each computation is f2 × n × (h + 1)), and thus the additional computation of the proposed access control policy is 4p × p3 + tsy +3h + 10x +tasy + l × f2 × n × (h + 1) on the routine phase. The computational amount of key negotiation, symmetric encryption key, and command hash is fixed, and the hash and Xor operations are negligible with respect to asymmetric encryption. Therefore, the computational amount is proportional to the encryption and decryption of the CP-ABE, which increases linearly with the increase in the node number in the network (increase in node IDs). □

The additional storage requirements of the access control scheme include one TPM hard and software module, n integrity metrics (each metric is typically 32 bytes), a set of negotiation keys, public–private key pairs and public parameters associated with the negotiation keys (a key length is typically 512 bytes), temporary storage of the data Md {C, h(data), Tv, (R, π)}, and process variables in encryption and decryption. Except for the command of variable finite length, all other variables are constants. The amount of data transferred within nodes has a negligible effect on the delay, and the additional amount of data transferred between nodes includes two public keys (1024 bytes) for TPM authentication, the public key (512 bytes) for negotiation key computation, and Md {C, h(data), Tv, (R, π)}; the amount of transferred data is also a constant.

Corollary 1.

Access control optimization ensures that the computing of resource-sensitive nodes and time delay is within acceptable limits and does not reduce the protection effectiveness.

Proof.

The computational amount of the TPM after the authentication is f2 × n × (h + 1). For the resource-constrained PLC, the integrity verification is implemented by the host computer. f2 is reduced to zero, and the verification computation is replaced by the transmission amount of sending n attributes as well as their hash values. The PLC loads the attribute-based access control sets <{ID}, {Act_Set}, {function, Nxe, Lx, E}> directly. The host computer delivers the control instructions to the PLC in a symmetric encrypted manner. The computational amount is n × h + 9x + 0.5tsy, which is competent for mainstream PLCs. The protection against unauthorized access, non-compliant access, tampering, and leakage of control commands in the PLC can still be guaranteed under the proxy mechanism. □

The optimization of the key update frequency makes it unnecessary for the source and target nodes to perform CP-ABE computation every time. During the period when the session key is not updated, the additional computation of the access control policy can be reduced to tsy + 3h + 10x + l × f2 × n × (h + 1), which greatly reduces the delay, and the additional transmission is {MK(data), h(data), Tv}, which is also reduced by about 50%. If the delay requirement is still not met when f1 takes the lower bound, the optimized key negotiation process negotiates a set of keys {K1, K2, …, Ktn} by DH negotiation, and when an exception occurs, current node and data sender pick a key that was not randomly used before in the key list for instruction transmission, avoiding the repeated negotiation process, which can further reduce the delay. The reduction in TPM monitoring frequency f2 can further optimize the time delay. At the same time, we set the optimization lower bounds of f1 and f2 as well as the mandatory update period Tmax to guarantee the timely identification of threats and timely update of keys. Once an attack is recognized, access is revoked and the session key is updated to prevent the threat from spreading.

4.3. Simulation Analysis of the Effect of Access Control Scheme Adjustment

This section analyzes the impact of policy adjustments on the protection effectiveness. The scheme deployment scenario in the industrial control network is shown in Figure 6. The access control server loads the access control module (ACM) into each node of the industrial control network. The ACM contains the support functions of the TPM, attribute-based access control policy, and key negotiation. Nodes other than controllers are deployed in the form of workstations (Intel i7 8th Gen, Window 10) and industrial control computers (Intel i5, 8G, Window 10, WINCC V7.0), which support the TPM chip. PLCs use Siemens 400/1200 models, which generally do not support TPM. According to the optimization scheme, the access control policy in PLC is simplified to attribute checksum and integrity metrics. The number of nodes is thirteen, the number of attributes is m = six, and the size of the LSSS matrix is 13 × 6. {Act_Set} consists of {read, write, relay}, {function} is set to be the monitoring function of key instructions, Nxe ∈ {Nh, Nm, Nr}, Lx ∈ {0, 1}, E ∈ {0, 1}. The number of integrity metrics is n = six. The key length is 512 K. The initial key negotiation frequency f1 is one secret at a time, the initial frequency of TPM f2 = 50, the maximum delay tmax = 150 ms, and the number of a set of negotiated keys tn = 10.

Figure 6.

Access control deployment scenario in industrial control network.

Based on the above scenarios and parameters, we analyze the effectiveness of access control policy adjustments. The two set metrics are:

Time delay: the time delay of the control cycle is tx, tx < tmax; tmax is the maximum time delay allowed.

Access control effectiveness: the metric is the access control recognition rate, which is defined as the percentage of successfully identified cycles in the total control cycles for the anomalies’ recognition.

The compared schemes are the Ruj scheme [12] and the Chen scheme [14]. The Ruj method uses the same CP-ABE method as our method, but the Ruj method uses complex homomorphic encryption to process the fused data and it lacks access policy optimization. Chen method adopts the access control method of trusted computing, which is the same concept as our method, but Chen method lacks fine-grained evaluation and optimization. We calculate the time delay of the Ruj method and Chen method in the same experimental environment. The numerical calculations are programmed by MATLAB 7.1.

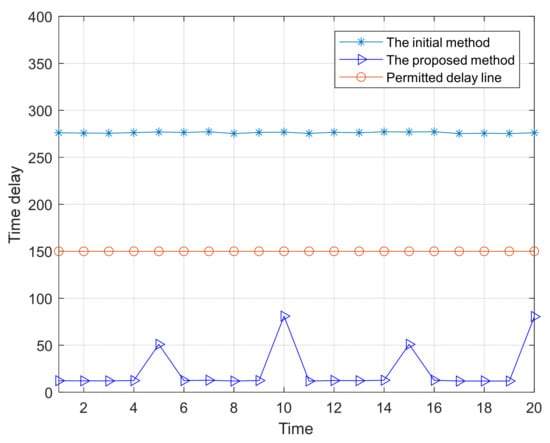

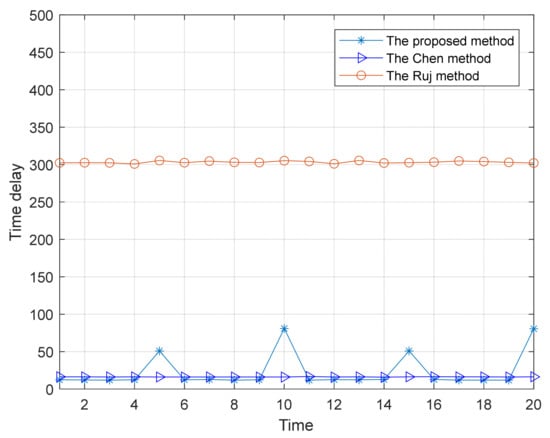

(1) Time delay: for completing control operations, we calculate the latency changes before and after policy adjustment; the results are shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Figure 7.

Adjusted access control time delay.

Figure 8.

Time delay comparison.

Figure 7 demonstrates the time delay in completing the processing and transmission of control commands in twenty experiments. Each time the control commands that flow from the workstation to the control server are loaded onto the PLC and executed to return the results to the control server and the workstation in turn, the entire process is one experimental cycle. The path is random each time. If necessary, the control server requests data support from the data server and the history server (six experiments involved). The allowable delay line is 150 ms, which is the delay period followed by general distributed control systems. We update the negotiated key on the 5th, 10th, 15th, and 20th times, and restore attribute access control on the 10th time after policy adjustment. We observe the change in the delay before and after the policy adjustment, and we can see that the delay returns to the delay limit line after the policy adjustment.

Figure 8 compares the time delay of the proposed method after policy adjustment with the other two methods. The delay of Chen’s method is larger than that of our method because the real-time construction of TEE (in the interaction phase about 2 tsy) to protect the interaction of sensitive data will generate a larger delay, but it is less than the delay of times with abnormal updates of our method (4p*p3 is added on each node at 5th and 15th times, and 4p × p3 + tasy at 10th and 20th times). Because the Ruj method adopts the homomorphic encryption (>100ms delay on each node) method and CP-ABE method, it lacks policy adjustment, its delay is large, and it is not suitable for an industrial control network.

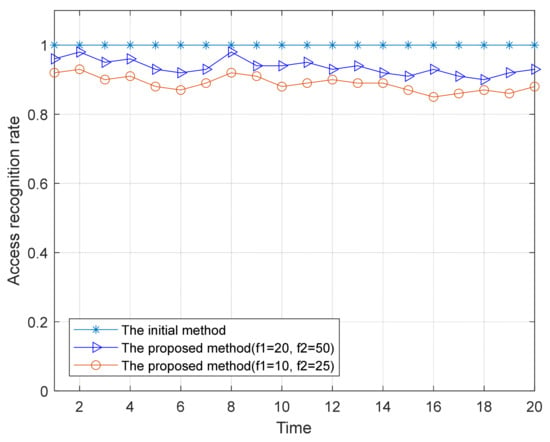

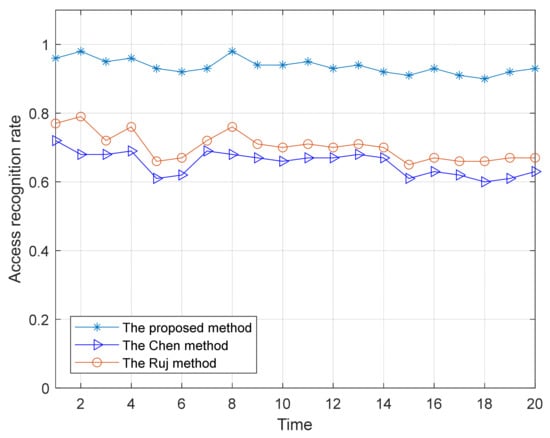

(2) Access control identification success rate: in the scenario where abnormal behavior exists, we calculate the success rate of the access control identification, and the results are shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 9.

Access identification success rate.

Figure 10.

Identification success rate comparison.

We perform twenty experiments of control command processing and transmission with the same experimental setup as in the above time delay section. The path is random each time. In each experiment, we perform 100 attacks, including 20 times of identity forgeries in Game 1 (performed by 1–2 randomly selected nodes out of 13 nodes), 20 times of unauthorized reads or writes in Game 2, 20 times of non-compliant operations in Game 3 (performed by 2 control servers on the control commands sent to 4 PLCs as well as by the PLCs themselves on the control commands), 20 times of tampering in Game 4 (that is Tamper (C, c1, c2)), and 20 times of leakage in Game 5 (that is Reveal(C)). We observe the cycles in which the anomalies are successfully recognized.

Figure 9 illustrates the relationship between access control identification success rate and policy optimization. The initial method refers to the access control method before policy optimization, which does not consider the energy and availability constraints of nodes, and all nodes have loaded all access control functions and trusted functions. Due to the corresponding protection against the above-mentioned threats in the proposed access control method, in the case of known threats and their combination, the initial approach has a 100% identification success rate. After the key update frequency f1 is reduced to the lower limit (f1 = 10) from normal frequency (f1 = 20), the recognition success rate decreases slightly, but the key update makes the access control function recover quickly. The change in the TPM monitoring frequency f2 (after the reduction from 50 to 25) also brings about a slight decrease in the recognition success rate, but it is still above 85%.

Figure 10 compares the recognition success rate of the three methods. The strategy adjustment is that PLC adopts the agent mechanism, f1 = 20, f2 = 50. The attribution-based CP-ABE method is deployed in the Ruj method, which has a high identification success rate. Due to the lack of identification of non-compliant behaviors (twenty non-compliant operations of Game 3 cannot be identified), the access control method is lower than the proposed method. Chen method lacks non-compliance identification and fine-grained tampering identification of legitimate nodes, and the success rate of access control is relatively low.

In summary, the proposed access control adjustment policy has advantages over existing methods in terms of guaranteeing delay and access identification success rate.

5. Conclusions

This article establishes an access control strategy for control instructions in industrial control systems that integrates trusted computing. We use a negotiated symmetric key to protect the transmission process of control instructions, and the authorization of the key is implemented by an attribute-based encryption method (CP-ABE). We model the business-associated attributes of industrial control systems into attribute-based access control methods to identify non-compliant operations of on-site equipment. The extracted attributes are used synchronously for the integrity measurement process of TPM. We optimize the key negotiation frequency and TPM monitoring frequency based on the availability constraints and abnormal behavior recognition of the industrial control system, ensuring availability while avoiding permission abuse. The analysis and experimental results show that the proposed access control method solves the problems of unauthorized access, non-compliant operations, tampering, and leakage of instruction data. It has advantages over existing methods in terms of time delay and access control recognition success rate. The delay of the proposed method is around 100 ms (maximum), which is not sufficient for application scenarios of field control or streaming data (a delay of less than 50 ms). This is a limitation of the CP-ABE method. In the future, we should collaborate with lightweight and effective access control methods to address the data collaborative protection issues in field control and monitoring control layers in the industrial control system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W. and M.Z.; methodology, M.Z. and J.W.; software, K.Z., M.Z. and X.C.; validation, M.Z. and X.C.; formal analysis, J.W.; investigation, M.Z., J.W. and X.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z., J.W., K.Z. and X.C.; writing—review and editing, M.Z., J.W. and X.C.; supervision, J.W.; project administration, J.W., M.Z., K.Z. and X.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Open Research Project of the State Key Laboratory of Industrial Control Technology, China (Grant No. ICT2024B38).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Khan, S.; Madnick, S. Cybersafety: A System-Theoretic Approach to Identify Cyber- Vulnerabilities & Mitigation Requirements in Industrial Control Systems. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2022, 19, 3312–3328. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Wu, S.; Ma, R.; Liu, M.; Luo, H.; Kaynak, O. Monitoring and Defense of Industrial Cyber-Physical Systems Under Typical Attacks: From a Systems and Control Perspective. IEEE Trans. Ind. Cyber Phys. Syst. 2023, 1, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Hu, B.; Shi, Y.; Tian, Y.-C.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y. A Unified Architectural Approach for Cyberattack-Resilient Industrial Control Systems. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 517–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliatsios, D.; Sarigiannidis, P.; Lagkas, T.; Sarigiannidis, A.G. A Survey on SCADA Systems: Secure Protocols, Incidents, Threats and Tactics. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2020, 22, 1942–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piggin, R.S.H. Development of industrial cyber security standards: IEC 62443 for SCADA and Industrial Control System security. In Proceedings of the IET Conference on Control and Automation 2013: Uniting Problems and Solutions, Birmingham, UK, 4–5 June 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Stouffer, K.; Falco, J.; Scarfone, K. Guide to Industrial Control Systems (ICS) Security; Document NIST SP-800-82; NIST: Gaithersburg, MA, USA, 2011.

- Lopez, J.; Rubio, J.E. Access control for cyber-physical systems interconnected to the cloud. Comput. Netw. 2018, 134, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leander, B.; Čaušević, A.; Lindström, T.; Hansson, H. Access Control Enforcement Architectures for Dynamic Manufacturing Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 20th International Conference on Software Architecture (ICSA), L’Aquila, Italy, 13–17 March 2023; pp. 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Li, X.; Xu, G.; Xiong, N.; Merlo, E.; Stroulia, E. An Effective Evolutionary Analysis Scheme for Industrial Software Access Control Models. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalle, P.N.; Anggorojati, B.; Prasad, N.R.; Prasad, R. Identity Authentication and Capability Based Access Control (IACAC) for the Internet of Things. J. Cyber Secur. Mobil. 2012, 1, 309–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafoorian, M.; Abbasinezhad-Mood, D.; Shakeri, H. A Thorough Trust and Reputation Based RBAC Model for Secure Data Storage in the Cloud. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2019, 30, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruj, S.; Nayak, A. A Decentralized Security Framework for Data Aggregation and Access Control in Smart Grids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2013, 4, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Fang, L.; Liu, Z.; Ge, C. A Secure Revocable Fine-grained Access Control and Data Sharing Scheme for SCADA in IIoT Systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 1976–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, W.; Zhang, N.; Zheng, Q.; Lou, W.; Hou, Y.T. Towards Efficient Fine-Grained Access Control and Trustworthy Data Processing for Remote Monitoring Services in IoT. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2019, 14, 1830–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, H.; Zhang, W.; Chen, W.; Wang, H. Secure, Efficient, and Weighted Access Control for Cloud-Assisted Industrial IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 16917–16927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowdanakatte, S.; Ray, I.; Houmb, S.H. Attribute Based Access Control Model for Protecting Programmable Logic Controllers. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Workshop on Secure and Trustworthy Cyber-Physical Systems (Sat-CPS ‘22), Baltimore, MD, USA, 27 April 2022; pp. 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cheminod, M.; Durante, L.; Valenza, F.; Valenzano, A. Toward attribute-based access control policy in industrial networked systems. In Proceedings of the 2018 14th IEEE International Workshop on Factory Communication Systems (WFCS), Imperia, Italy, 13–15 June 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, G.; Liu, B. An efficient attribute-based access control system with break-glass capability for cloud-assisted industrial control system. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2021, 18, 3559–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiquito, A.; Bodin, U.; Schelén, O. Attribute-Based Approaches for Secure Data Sharing in Industrial Contexts. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 10180–10195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Lu, Y.; Wei, W.; Chen, X. Efficient Data Access Control with Fine-Grained Data Protection in Cloud-Assisted IIoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 2886–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Liu, S.; Tan, G.; Qiao, F. Fine-grained access control based on Trusted Execution Environment. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 109, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Bera, B.; Das, A.K.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Khan, M.K.; Rodrigue, J.J.P.C. Private blockchain-envisioned multi-authority CP-ABE-based user access control scheme in IIoT. Comput. Commun. 2021, 169, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Doröz, Y.; Polyakov, Y.; Rohloff, K.; Sajjadpour, H.; Savaş, E.; Sunar, B. Implementation and Evaluation of a Lattice-Based Key-Policy ABE Scheme. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2018, 13, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, Y.; Li, Z. An Expressive Fully Policy-Hidden Ciphertext Policy Attribute-Based Encryption Scheme With Credible Verification Based on Blockchain. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 8681–8692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Joshi, K.P.; Choi, S.G. Multi Authority Access Control in a Cloud EHR System with MA-ABE. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Edge Computing (EDGE), Milan, Italy, 8–13 July 2019; pp. 107–109. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, B.; Yan, F.; Yu, F.; Zhang, L.; Xu, M. Research on trusted computing and its development. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2010, 53, 405–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, M. A Trust Management Method against Abnormal Behavior of Industrial Control Networks under Active Defense Architecture. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2022, 19, 2549–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.