Abstract

This article presents the design, fabrication, and experimental validation of a centimeter-scale autonomous robot that achieves bidirectional locomotion and trajectory control through 3D-printed resonators actuated by piezoelectricity and integrated with miniature legs. Building on previous works that employed piezoelectric bimorphs, the proposed system replaces them with custom-designed 3D-printed resonant plates that exploit the excitation of standing waves (SW) to generate motion. Each resonator is equipped with strategically positioned passive legs that convert vibratory energy into effective thrust, enabling both linear and rotational movement. A differential drive configuration, implemented through two independently actuated resonators, allows precise guidance and the execution of complex trajectories. The robot integrates onboard control electronics consisting of a microcontroller and inertial sensors, which enable closed-loop trajectory correction via a PD controller and allow autonomous navigation. The experimental results demonstrate high-precision motion control, achieving linear displacement speeds of 8.87 mm/s and a maximum angular velocity of 37.88°/s, while maintaining low power consumption and a compact form factor. Furthermore, the evaluation using the mean absolute error (MAE) yielded a value of 0.83° in trajectory tracking. This work advances the field of robotics and automatic control at the insect scale by integrating efficient piezoelectric actuation, additive manufacturing, and embedded sensing into a single autonomous platform capable of agile and programmable locomotion.

1. Introduction

Process automation has been the subject of research and development since the emergence of the first autonomous robots, such as Shakey (developed between 1966 and 1972), up to the present day [1]. Since then, efforts have focused on identifying application areas in which repetitive tasks could be automated. The earliest robots featured simple, large, and robust designs, in stark contrast to certain contemporary developments that, in addition to traditional industrial models, also incorporate bioinspired morphologies [2,3].

Bioinspiration adopts conceptual approaches derived from the behavior of various biological organisms. Among them are snakes, worms, geckos, fish, insects, spiders, dogs, and humans, which have been studied to replicate their mobility and adaptive capabilities. These strategies have enabled application proposals in fields such as industry, household environments, medicine, and space exploration, among others [4].

The growing demand for robots in diverse applications has driven the development of devices designed to optimize parameters such as size, mobility, speed, processing capability, and autonomy. These advances have fostered research on robots with various morphologies and scales, including humanoids, robotic arms, soft robots, microrobots, and miniature systems [5]. The miniaturization of electronic systems, enabled by the evolution of micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS), has made it possible to integrate sensors and control units into autonomous micro- and millimeter-scale robots. This progress has led to the development of prototypes with dimensions comparable to those of insects, whose low weight, reduced size, and agility make them attractive candidates for operation in environments that are difficult to access for conventional robots or humans. Among the most relevant applications of these systems are fault inspection, micromanipulation, minimally invasive medicine, and infrastructure evaluation [6,7,8].

Nevertheless, miniaturization poses significant challenges, such as identifying actuators capable of generating efficient motion at the microrobotic scale. In this context, several alternatives have been proposed, including electromagnetic micromotors with volumes smaller than 1 cm3 [9], shape memory alloys, magnetostrictive materials, artificial muscles, dielectric elastomers, and piezoelectric ceramics, each offering specific advantages and limitations depending on the application [10,11].

At the macroscale, electromagnetic motors have been the predominant actuators. However, at reduced scales, their fabrication becomes complex and their energy efficiency decreases [12]. Among the most promising alternatives are piezoelectric actuators, which exploit the inverse piezoelectric effect and offer advantages such as low cost, feasibility of miniaturization, high resolution, robust control, fast response, compact architecture, and immunity to electromagnetic interference, making them particularly attractive for microrobotic applications [13].

Piezoelectric actuators can adopt various geometric configurations, with bimorphs and piezoelectric patches being the most commonly used in insect-scale robots. Bimorph robots have shown promise; however, in robots fabricated using 3D printing, electrode segmentation and the routing of the wiring associated with bimorphs introduce construction constraints due to limited space, the need for multiple electrical interconnections, and susceptibility to mechanical and electrical failures under vibration [7]. In contrast, using piezoelectric patches bonded to plate-beam structures simplifies electrical integration in 3D-printed platforms and enables locomotion through resonant excitation of the structure, establishing standing-wave (SW) or traveling-wave (TW) modes that generate effective tangential forces for microrobot displacement [14]. This principle was described by Siyuan He in the context of bidirectional ultrasonic motors [15]. Based on these fundamentals, different types of architectures and miniature robots have been developed that employ this mechanism to produce linear or rotational movements. In this context, the study [14] applies piezoelectric patches on a resonant plate with attached legs and comparatively analyzes the locomotion obtained through SW and TW. The experimental results show that locomotion based on TW reached speeds of up to 6 BL/s, while the use of SW achieved speeds of up to 14 BL/s, demonstrating that the SW strategy provides significantly higher performance than the TW. At this stage, the prototype was driven by external signals and did not incorporate a microcontroller for autonomous operation.

The feasibility of miniaturization and the efficient use of piezoelectric actuators for vibration propagation inherently depend on the materials and manufacturing techniques employed. In this regard, 3D printing has demonstrated superior results compared to traditional methods such as CNC machining or injection molding [16]. Additive manufacturing enables rapid prototyping of lightweight structures with complex geometries, which is critical for millimeter-scale devices where precision is a determining factor [17]. In this context, laser-based 3D printing provides the required resolution and enables the use of cured photopolymers with a tensile modulus of up to 10 GPa [18]. This high stiffness is a key factor because it influences the microrobot’s mechanical performance and is essential to ensure efficient transmission of the mechanical energy generated by the actuators while minimizing losses [19].

These advances in materials and fabrication techniques have enabled the emergence of high-performance piezoelectric microrobots. For instance, [7] reported a robot measuring 29 × 17 × 18 mm3 and weighing 7.4 g is presented, capable of generating linear and rotational movements through SW waves on a glass surface. The experimental results were promising, reaching a maximum speed of 70 mm/s and a rotational speed of up to 190°/s. The system presented a power consumption of 50 mW and a continuous operation time of approximately 6.7 h. The robot managed to follow pre-programmed trajectories, demonstrating agility and control in navigation within complex environments. The limitations present in this work were the adaptation to different surfaces and the lack of sensors that would allow accurate trajectory tracking.

In the context of pursuing autonomy in miniature robots, the authors in [20] designed a robot that emulates the traveling-wave motion of a snail. The robot has dimensions of 27.5 × 26 × 4 mm3 and a weight of 7.9 g, achieving linear speeds of up to 383 mm/s and rotational speeds of 690°/s. It incorporates a 200 mAh battery, providing an approximate operating time of 14.5 min, as well as a wireless real-time image acquisition system to determine its position and orientation during navigation. The experimental results demonstrated excellent controllability and great potential for future applications in complex or hard-to-reach environments. Although the robot includes an integrated camera for navigation, there remains the possibility of incorporating additional microsensors to further expand its range of applications.

The use of sensors in miniature robots is a research topic that remains under active development, as sensors open the possibility of achieving complete autonomy and expanding the range of applications. In [21], PVDF piezoelectric materials were used as actuators, together with a microcontroller and a customized infrared sensor module to track a predetermined trajectory. This robot measures 2 cm in size and weighs 1.12 g. It can move at a speed of 96 mm/s and rotate at 280°/s clockwise and 180°/s counterclockwise. The robot successfully followed a black navigation line at an average speed of 3 mm/s, dynamically adjusting its trajectory through infrared feedback and achieving autonomous trajectory correction control. In the context of miniature robots that employ sensors, Kilobot [22] stands out, a 3.3 cm-scale robot that integrates infrared and ambient light sensors, as well as [23], which uses a visible light sensor (AS7341) to communicate with other robots and follow trajectories based on light intensity.

Similarly, ref. [24] presents an insect-scale quadruped robot integrating a 9-degree-of-freedom (DOF) MPU-9250 inertial measurement unit (IMU) communicating via I2C, which is employed to estimate yaw rotations for closed-loop velocity control. In a related context, [25] utilizes an accelerometer and gyroscope to stabilize the attitude of a fly-sized hovering robot that employs piezoelectric actuators for altitude control. These works highlight the pivotal role of inertial sensing for autonomous control in both terrestrial locomotion and aerial microrobotics.

Given the importance of sensors in microrobotics, this work proposes the integration of an IMU into a robot driven by piezoelectric standing waves, with the aim of achieving precise planar trajectory control. This approach differs from the studies in [24,25], which primarily focus on attitude stabilization or velocity regulation. The present article is structured as follows: Section 2 describes the design and construction of the robot; Section 3 focuses on validating its performance; and finally, Section 4 and Section 5 present the insights derived from this study.

2. Materials and Methods

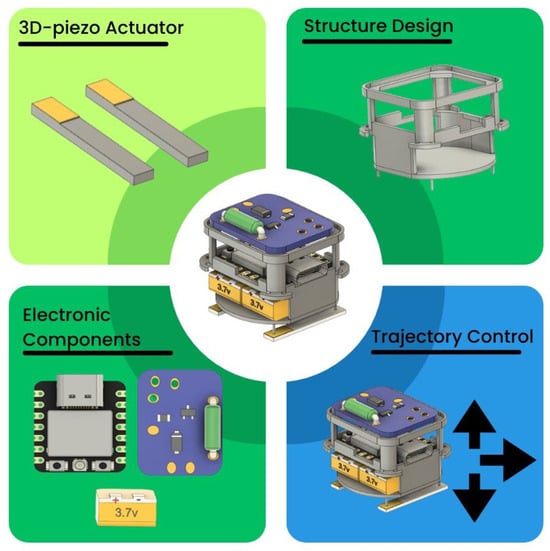

The methodology for the development of this work is divided into four main parts, which are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Methodology for the Trajectory Control of a Miniature Robot.

- The 3D-piezo Actuator block represents the use of miniature motors for generating the robot’s movements, built from 3D-printed plates with a defined geometry and incorporating PZT patches.

- The Structure Design block represents the structural and 3D-printed plates design of the miniature robot; this structure enables the integration of the control and power elements with the PZT actuators.

- The Electronic Components block represents the integration of the control and power circuits for the trajectory control of the robot.

- The Trajectory Control block represents the design of the algorithm implemented in the microcontroller for movement generation and control.

2.1. 3D-Piezo Actuator

For the locomotion of the miniature robot, unimorph piezoelectric patches made of lead zirconate titanate (PZT), specifically the modified PZT material PIC 255 from PI Ceramic [26], were employed. Their main characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main Properties of the Piezoelectric Material PIC 255 [27].

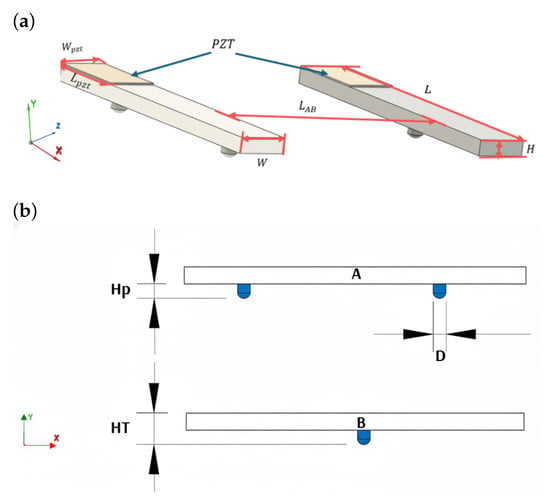

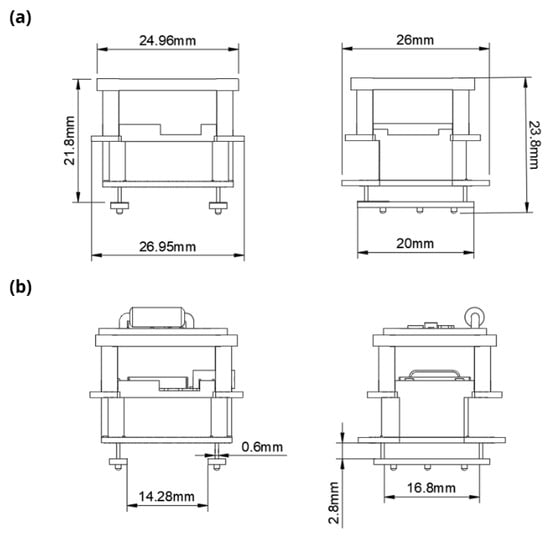

The PZT patches, with dimensions μm, mm, and mm, are placed on top of two plates (A and B) that are 3D-printed using SLA technology with Form3 printer and Formlabs Rigid 10 K resin (Formlabs, Somerville, MA, USA) [28]. The PZT patches are fixed to the plates using Loctite. These plates, represented in Figure 2, have dimensions of mm, mm, and mm, with Plate A containing two legs and Plate B one leg, with dimensions of mm, mm and mm. This design and configuration are based on the referenced study [19].

Figure 2.

(a) Plates A and B with PZT patches. (b) Legs (blue parts) on plates A and B for the generation of linear movements.

In contrast to [19], in this work, the plates are separated by a distance of mm. This separation allows for a balance between the structure containing the control and power components and the piezoelectric actuators.

The linear movements of the miniature robot are obtained by generating SW on plates A and B, exploiting the structure’s response in flexural modes. These modes allow the legs to be positioned between a node and an antinode of the wave, so that their placement enables the generation of rectilinear trajectories [19]. In the present study, the arrangement of the legs follows the description in [19], employing (50) and (60) modes, with legs measuring 1.1 mm in height and 0.6 mm in diameter (Figure 2b), and the actuator patches (PZT piezoelectrics) and leg length were defined based on previous studies [7,14,19]. This configuration ensures stability and enables the generation of linear forward and backward movements, as well as clockwise and counterclockwise rotations.

In this study, (50) and (60) modes were selected because they exhibit maximum amplitudes near the edges and nodal lines toward the interior. This distribution allows the legs to be positioned at the extremities, away from nodal regions, thereby improving the system’s traction and stability compared to other configurations [19].

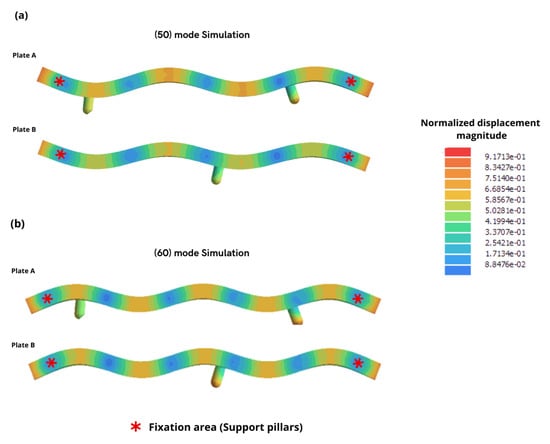

Figure 3a,b show the finite element modal (FEM) analysis performed in SIMSOLID for Plates A and B, where the deformation patterns and the most suitable regions for leg placement can be observed. The color map represents the magnitude of the normalized displacement, scaled relative to the maximum peak displacement. Accordingly, a value of 1 corresponds to the maximum vibration amplitude, while 0 indicates zero displacement. These simulations were performed under free boundary conditions without support pillars to accurately identify the nodal lines. The structure’s mounting points were then assigned to these nodal regions where displacement is close to 0 to minimize damping. This analysis supports the final selection of the leg locations, prioritizing regions with high modal energy and moderate curvature gradients to reduce unwanted rotations during ground contact.

Figure 3.

FEM analysis of the piezoelectric plates showing the modal shape for the selected vibration modes. (a) Modal shape of (50) mode from the FEM simulation for Plates A and B; (b) modal shape of (60) mode from the FEM simulation for Plates A and B.

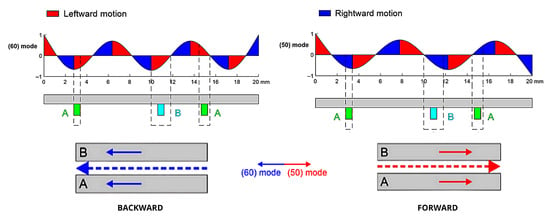

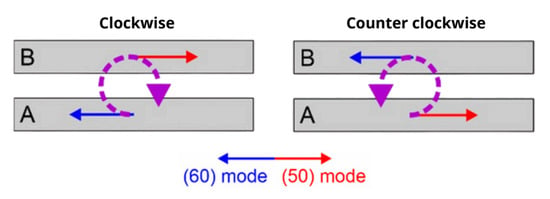

An important effect related to the control of the miniature robot is associated with the leg–surface interaction, where the direction of motion is reversed compared to the case in which the legs are not in contact. When the legs are positioned to the right of an SW crest, the robot tends to move to the left, whereas placing them to the left of the crest results in motion toward the right. This principle allows mode alternation to generate displacements in different directions, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Generation of the robot’s linear motion through standing waves (SW) using (50) and (60) modes [19].

The combination of (50) and (60) modes produces rotational movements in the clockwise and counterclockwise directions, respectively, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Combination of (50) mode and (60) mode to generate rotational movements [19].

2.2. Electronic Components

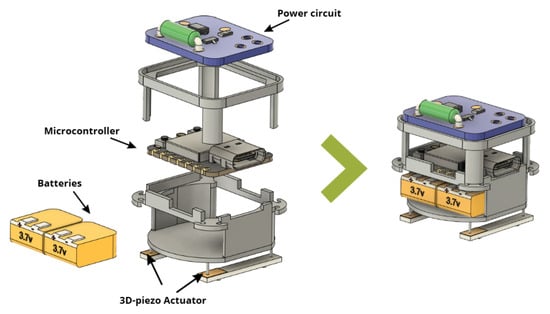

The miniature robot actuated by piezoelectric elements is composed of two 3.7 V Li-Po batteries (Generic, China), a microcontroller for trajectory control, and a power circuit that amplifies the excitation signals applied to the piezoelectric actuators. Figure 6 presents an unmounted and assembled view of the robot.

Figure 6.

Components of the miniature robot for trajectory control.

2.2.1. Microcontroller

The robot’s autonomy relies on the acquisition of motion data from the inertial measurement unit (IMU), the implementation of control algorithms, the generation of PWM signals to drive the actuators, and a low-power-consumption strategy that collectively enable controlled movements and the maintenance of a defined trajectory. Consequently, the integration of an embedded microcontroller becomes essential. However, the robot’s compact size and the use of batteries for power supply impose strict constraints on the selection of the control unit. Under these conditions, a compact, low-power commercial board that incorporates inertial sensors and meets the requirements of this work is the Seeed Studio XIAO nRF52840 Sense (Seeed Studio, Shenzhen, China), which has a compact and lightweight form factor (21 × 17.5 mm; ~3 g). This board integrates the Nordic nRF52840 SoC (ARM Cortex-M4; 16 MHz peripheral clock), 1 MB of flash memory, and 256 KB of RAM, as well as 11 GPIO with 11 PWM outputs and 6 ADC channels. In addition, it provides UART, I2C, SPI, SWD, NFC and Bluetooth 5.0 communication interfaces.

One of the fundamental features for this work is the on-board sensing, which includes a 6-axis IMU (triaxial accelerometer and gyroscope) and a PDM microphone, with low-power operation (5 µA). These characteristics, such as low weight, compact dimensions, communication protocols, low energy consumption, and integrated sensors, are essential for closed-loop trajectory control and provide a solid foundation for future research and developments [29,30].

2.2.2. Power Circuit

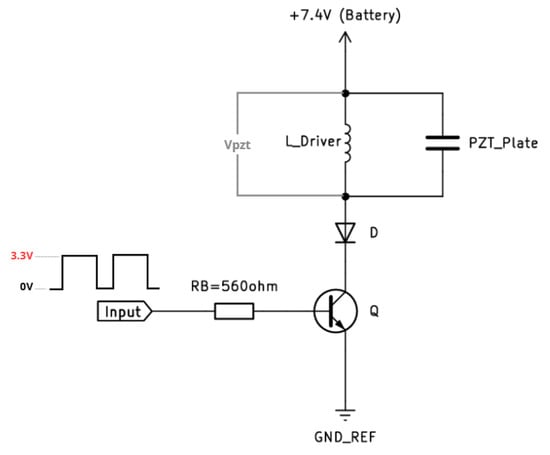

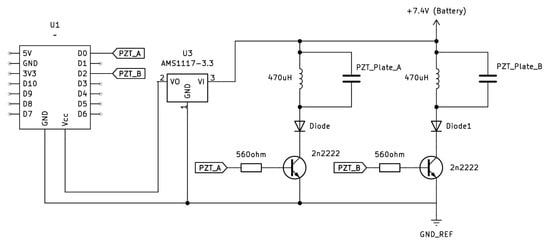

After the microcontroller is selected, the power circuit is designed to increase the excitation voltage of the piezoelectric elements. The microcontroller generates PWM signals at 60 kHz for (50) mode and 95 kHz for (60) mode; these signals have an amplitude of 3.3 V. The voltage supplied by the microcontroller is too low to generate the movements of the miniature robot, which is why the circuit shown in Figure 7, based on [31,32], is implemented.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the power circuit.

The capacitance of the piezoelectric actuators was determined using the practical RC circuit method described in [33]. For this procedure, an Analog Discovery 2 signal generator and a Siglent SDS1104X-E oscilloscope were used to acquire the necessary signals for the calculation. Based on the obtained results, the capacitance of the piezoelectric actuators was determined to be .

Since the robot incorporates two piezoelectric actuators and bidirectional locomotion requires exciting two modes per actuator, a conventional implementation would use one LC tank (defined by and ) per mode, i.e., four inductors, which increases the circuit size and complexity. To reduce component count and volume, the proposed design uses a single inductor per actuator, shared between both modes. According to [32] and our simulations, the electrical resonance of the LC tank does not need to match the mechanical resonance . Instead, setting the electrical resonance close to twice the acoustic resonance maximizes the peak voltage across the transducer and improves efficiency. This relationship is expressed in Equation (1) through the parameter n, which represents the ratio of the electrical resonance frequency of the circuit to the modal resonance frequency of the piezoelectric actuator.

For the two acoustic modes considered—the (50) mode at 60 kHz and the (60) mode at 95 kHz—the condition would yield two different optimal inductance values. However, when a single inductor is used, two scenarios arise:

- If is selected for (60) mode, then and .

- If is selected for (50) mode, then and .

Among these options, choosing close to the value for mode (60) provides higher output power, as shown in Table 2. This choice enables efficient excitation of both resonant modes while keeping a compact and simplified design.

Table 2.

Tested inductors and corresponding electrical response (with and ; kHz, kHz).

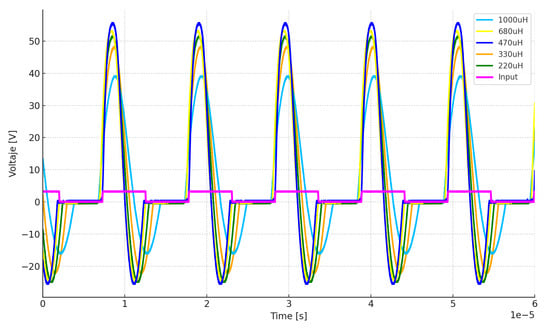

Figure 8 shows the circuit response for each inductor listed in Table 2, excited at a frequency of 95 kHz with a 50% duty cycle. These inductors were selected because they represent the upper and lower operating limits before signal distortion occurs and the current exceeds 600 mA, which is the maximum value supported by the 2N2222A transistor in its SOT-23 package (Onsemi, Phoenix, AZ, USA).

Figure 8.

Piezoelectric voltage (voltage at the inductor terminals applied to the actuator) and control signal (PWM input from the microcontroller) at with a 50% duty cycle. The duty cycle is shown here for illustration but can be tuned to maximize power transfer to the piezoelectric actuator.

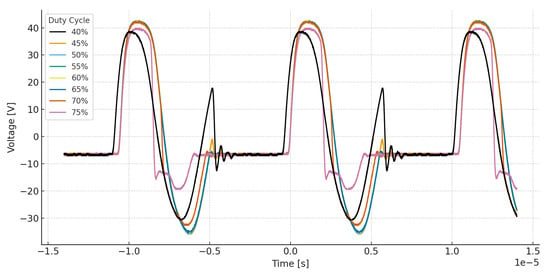

To maintain a favorable trade-off between a high excitation voltage and low current consumption, a commercial 470 µH inductor was selected. Although other inductance values may exhibit a similar waveform behavior, they can significantly increase the required current. As shown in Table 2, the 470 µH inductor provides 81.2 with 0.03A, whereas the 220 µH inductor delivers a slightly lower voltage (76.4 ) but requires a higher rms current (0.10A), which would reduce the robot’s autonomy and increase conduction (Joule) losses in the inductor. Furthermore, the generated waveform is closely linked to the relationship between duty cycle and switching frequency. This behavior is analyzed in Figure 9, where the duty cycle is varied from 40% to 75% while the frequency is kept constant at 95 kHz using the 470 µH inductor.

Figure 9.

Duty cycle variation between 40% and 75% to keep the current within the minimum and maximum limits that ensure proper operation of the piezoelectric actuators.

Based on this analysis, it is observed that duty cycles between 50% and 65% exhibit a similar behavior. However, considering the robot’s displacement and the incorporation of both piezoelectric actuators, better results were achieved when selecting a 65% duty cycle. At this value, the signal shows no appreciable distortion and maintains a stable voltage of approximately 81.2 with a current of 30 mA, thereby ensuring an adequate excitation of the piezoelectric actuators.

2.3. Energy Consumption in the Batteries

The miniature robot uses two 401010 Li-Po batteries connected in series in order to provide a voltage of 7.4 V. This voltage powers the LC resonator circuit (Figure 7) and an AMS1117 voltage regulator, which steps the voltage down to 3.3 V to power the microcontroller. The electronic schematic of the miniature robot is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Electronic schematics of the miniature robot.

The key specifications of these batteries are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Specifications of the Li-Po 401010 Battery [34].

To determine the operating time of the miniature robot, the maximum current consumption of the microcontroller and the power circuit are summed, and Equation (2) is applied, following [35].

where

- t: Battery duration.

- C: Battery capacity.

- : Battery efficiency.

- : Average current considering the consumption of the microcontroller with the IMU sensor, Bluetooth module, and status LEDs turned on, along with the power circuit operating at 60 kHz.

2.4. Design of the Miniature Robot Structure

The structural design of the robot was conceived in a compact and lightweight manner, so that it could incorporate and support the mass of the electronic components listed in Table 4. It is worth noting that the weights presented correspond to experimental measurements of the physical components.

Table 4.

Dimensions and weight of the electronic components that constitute the miniature robot.

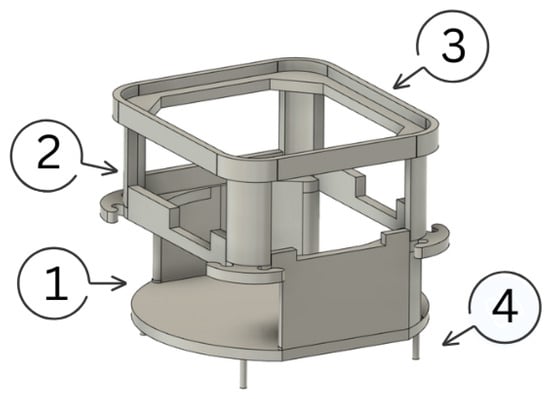

The miniature robot structure consists of four stages, as shown in Figure 11:

Figure 11.

Structural parts designed to accommodate the electronic components of the robot.

- Lower stage (1): Designed to house the batteries.

- Intermediate stage (2): Designed to place and support the microcontroller.

- Upper stage (3): Allows the placement of the oscillator circuit.

- Support pillars (4): Connect plates A and B with the robot structure for motion generation.

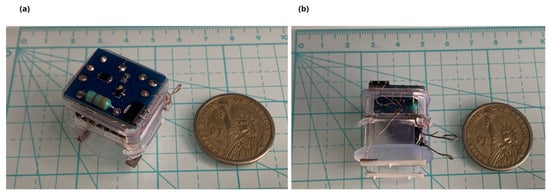

The structure was manufactured by 3D printing in Clear resin from Formlabs using SLA printer [36]. The final dimensions of the structure were: length of 26 mm, width of 26.95 mm, and height of 23.8 mm, with a total mass of 1.8 g (Figure 12a). The support pillars have a cylindrical geometry, with a height of 2.8 mm and a diameter of 0.6 mm. To minimize vibration disturbances, the pillars are positioned at the midpoint between the first two nodal points of (50) and (60) modes. This selected position is located 1 mm from the beginning and end of plates A and B, respectively, as shown in Figure 12b.

Figure 12.

Width, length, and height dimensions of the robot structure.

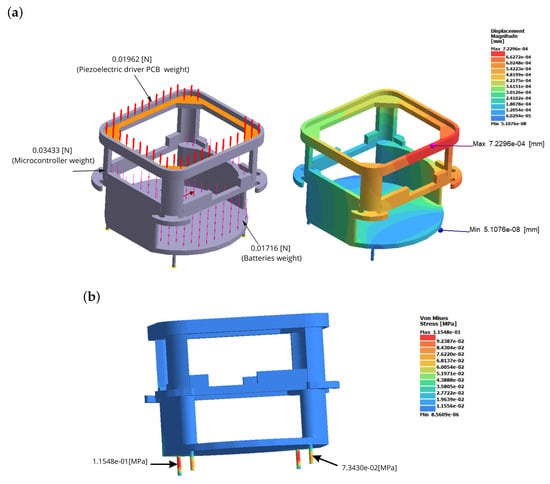

To validate the design, a structural analysis was performed with SimSolid, considering the mechanical properties of the resin and the point loads from Table 4. The static analysis evaluated the total displacements and the equivalent Von Mises stresses.

The simulation results showed a maximum displacement of mm at the point shown in Figure 13a; this value is negligible with respect to the dimensions of the structure. The Von Mises stresses are shown in Figure 13b; these stresses are between MPa and MPa, which represents 0.234% of the material capacity. Therefore, the designed structure is capable of safely supporting all the considered components.

Figure 13.

Finite element analysis of the robot structure: (a) Static deformation under point loads equivalent to the microcontroller, piezoelectric driver PCB, and battery weights (scale in mm). (b) von Mises stress distribution in the supporting legs of the structure (scale in MPa).

The integration of the miniature robot’s components is presented in Figure 14. In the side view (Figure 14a), the oscillator circuit is mounted on the top of the structure and secured at its corners with a cyanoacrylate-based adhesive (Loctite). The top view (Figure 14b) shows the junction of the pillars with plates A and B; this joint was made with the same adhesive to ensure a rigid, stable connection.

Figure 14.

Photographs of the assembled miniature robot: (a) Front view showing the structural frame and electronic components; (b) oblique view of the miniature robot structure showing the arrangement of the electronic board and supporting plates A and B.

The connection between the microcontroller, the resonance plate and the piezoelectrics is made using enameled copper wires of 10 µm in diameter. The assembled prototype maintains the dimensions established in the previous design (26 mm × 26.95 mm × 24.2 mm) and a total weight of 9 g.

The compact distribution of the components ensures the stability of the robot and allows efficient integration of the electrical and mechanical systems.

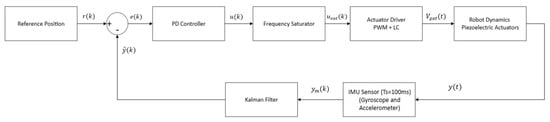

2.5. Trajectory Control

To control the trajectory of the miniature robot, a closed-loop control system is implemented with a zero reference . The system integrates an IMU sensor to estimate the robot’s rotation angle and direction , a control signal that modulates the frequency applied to the piezoelectric actuators , and a control algorithm designed to minimize the tracking error. Figure 15 presents the block diagram used for the robot control system.

Figure 15.

Block diagram for the trajectory control of the miniature robot.

2.5.1. IMU Sensor

The microcontroller integrates an LSM6DS3 inertial sensor (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland) with six degrees of freedom (triaxial gyroscope and triaxial accelerometer, 16-bit). In the selected configuration, the gyroscope operates at ±2000°/s with a sensitivity of , and the accelerometer at g with a sensitivity of ; these ranges were chosen to prevent saturation and to enable precise capture of rapid motion variations and large-magnitude accelerations during frequency changes in the miniature robot’s movement [37]. The axis reference used throughout the processing is defined with respect to the board: the X axis points toward the USB connector, the Y axis points to the left side (with the USB on the right), and the Z axis is perpendicular to the PCB, pointing outward. The components measure linear acceleration along these directions, and represent angular velocity about each axis, with positive sign defined by the right-hand rule.

2.5.2. Kalman Filter

The data acquired from both sensors are processed using a Kalman filter, which effectively mitigates oscillations arising from the device’s intrinsic disturbances as well as vibrations induced by the piezoelectric actuators. For the application of the Kalman filter, the prediction and update equations presented in (3) and (5) were applied [38].

The prediction step is defined in Equation (3).

where corresponds to the a priori estimated state, the a posteriori state, the a priori error covariance, the a posteriori error covariance, and Q the process noise covariance constant. In this work, the values and were used to simplify the expressions, as shown in (4).

The update step is presented in Equation (5):

where represents the Kalman gain, R the measurement noise covariance, the current sensor measurement, and the updated error covariance. In this case, the value was assigned for the reduction in Expression (6).

The values used in Equations (3) and (5) to implement the Kalman filter are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Values used for the initialization of the Kalman filter.

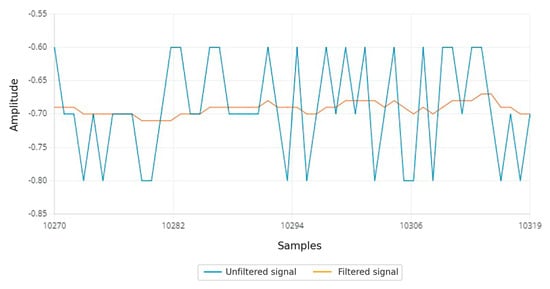

The parameters presented in Table 5 were selected to achieve a balance between responsiveness and sensor noise attenuation. With these values, the intrinsic noise of the system and the vibrations from the piezoelectric actuators are effectively reduced. Figure 16 shows the significant reduction in gyroscope perturbations in the Z-axis.

Figure 16.

Comparison between the gyroscope Z-axis signal without filtering (blue) and the signal filtered with the Kalman algorithm (orange) during the rest state, with no robot motion.

In this study, only the Z-axis rotation values are considered due to the position of the microcontroller and the direction that needs to be corrected for position control.

2.5.3. Gyroscope Calibration and Angle Estimation

As shown in Figure 16, when the miniature robot is at rest, it exhibits random noise and signal drift, which introduce a systematic bias in the measurement of angular velocity. Since the angular velocity should ideally be zero at rest, the bias error is determined using Equation (7) [39]:

where

- N: total number of acquired samples.

- : gyroscope signal acquired from instant to N.

The determined bias value represents the average displacement of the acquired signals. To ensure that the sensor values are centered around zero during the resting state, the corrected measurement is applied using Equation (8):

where represents the corrected angular velocity measurement after eliminating the average noise. In this work, gyroscope calibration was performed by keeping the miniature robot at rest from s to s, with a sampling period of 2 ms, resulting in approximately 1000 samples.

The corrected measurement helps reduce the accumulation of errors when transforming angular velocity into angular position . For this purpose, the integral of the angular velocity is applied, as shown in Equation (9):

2.5.4. PD Control

The motion of the miniature robot is regulated by a Proportional Derivative (PD) controller, which adjusts the frequency applied to the piezoelectric actuators to maintain a predefined path. This application allows correcting the angular position based on the feedback provided by the gyroscope.

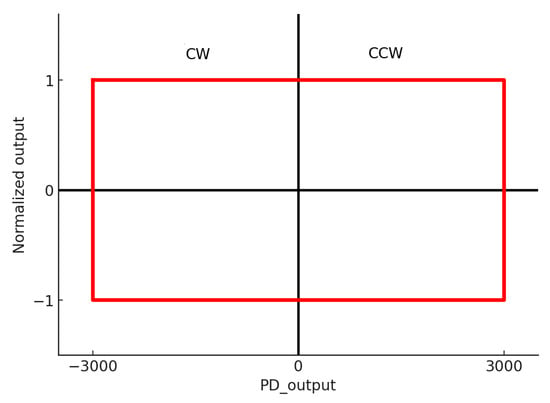

The regulation is based on the hysteresis curve shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Hysteresis curve for PD control showing the switching logic of actuators A and B during midpoint, positive phase (CCW), and negative phase (CW).

The midpoint allows both actuators, A and B, to remain in (50) mode at a frequency of 60 kHz, while the positive phase of the hysteresis curve allows actuator B to switch to (60) mode, with a frequency of 95 kHz, and actuator A to remain in (50) mode to generate a counterclockwise rotation of the robot. The negative phase of the hysteresis allows a clockwise rotation, setting actuator A to (60) mode and actuator B to (50) mode. The base frequency of 60 kHz is selected on the ascending slope of the (50) mode resonance to maximize amplitude modulation, while 95 kHz is used to fully excite the (60) mode.

The general function used for actuators A and B is presented in Equation (11):

where represents the frequency value sent to the PWM of the respective actuators and is the value of the PD controller output.

To assign the frequencies to the respective actuators, Equation (12) is used:

To limit the frequencies sent to each actuator, a saturator is used, expressed as Equation (13):

The output of the controller in continuous time is defined as:

The backward difference approximation of Equation (14) for the discrete PD controller is defined as:

where

- : Proportional gain.

- : Derivative gain.

- : Error between the reference and the gyroscope measurement at the current instant.

- : Error between the reference and the gyroscope measurement at the previous instant.

- : Sampling period.

The tuning of the and values was carried out experimentally through a heuristic procedure, with the aim of achieving a balance between response speed and system stability. The proportional gain was increased up to a value of 700, which allowed a fast response to trajectory changes. Subsequently, the derivative gain was set to 80 in order to reduce overshoot and attenuate system oscillations. The parameter adjustment employed in this work proved to be more effective compared to the model identification of the robot obtained by software. It should be noted that software-based identification presents limitations due to gyroscope noise and the nonlinear dynamics of the robot, which leads to an approximation that is not fully representative of the real model. In contrast, experimental tuning allowed establishing and values that provided satisfactory performance in terms of speed and stability under real operating conditions.

The feedback latency between sensing, control and actuation introduces an inherent discrete-time delay. In our implementation, its impact is primarily governed by the fixed sampling period and the discrete PD controller dynamics. Thus, within the tested operating range, the closed-loop response is consistent with sufficiently linear behavior around the nominal operating point, with no clear evidence of discretization-induced degradation.

Substituting the values of and , with a sampling time of ms, into Equation (16), we obtain:

3. Results

The experimental evaluation of the miniature robot was structured into four main tests:

- 1.

- Conductance test of plates A and B, aimed at validating the electrical response of the piezoelectric resonators when excited in (50) and (60) modes.

- 2.

- Linear displacement velocity test, performed to determine the average forward speed of locomotion.

- 3.

- Angular velocity test, designed to evaluate clockwise and counterclockwise rotational movements.

- 4.

- Trajectory error tests, carried out under two conditions:

- (a)

- without trajectory control, and

- (b)

- with proportional–derivative (PD) control for path correction.

These tests provide the basis for determining the generation of movement, linear speed of locomotion, maneuverability for rotation, and trajectory correction of the proposed robot. The detailed results of each test are presented in the following subsections.

3.1. Conductance Test of Plates A and B

The objective of this test was to validate the electrical response of the piezoelectric actuators coupled to plates A and B, fully assembled within the complete robotic structure. For this purpose, a series RC circuit was implemented, in which a resistor was connected in series with each of the piezoelectric actuators. Using an Analog Discovery 2 board, a sinusoidal signal in the range of 40 to 100 kHz, with an amplitude of 500 mV, was applied.

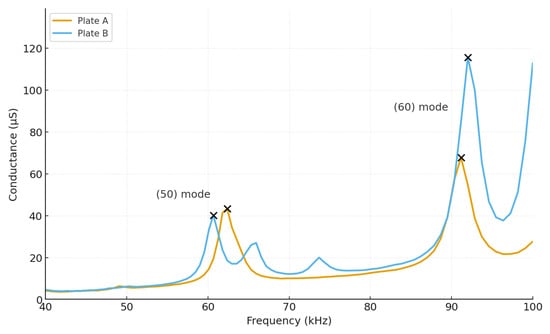

The frequency response obtained is shown in Figure 18, where resonance peaks corresponding to (50) and (60) modes can be observed.

Figure 18.

Conductance vs. Frequency for Plate A and Plate B. Resonance peaks corresponding to (50) and (60) modes are identified.

The quantitative results of the test are summarized in Table 6, where it can be observed that for (50) mode, the resonant frequencies are located at 62.37 kHz for plate A and 60.67 kHz for plate B, with conductance values of 43.4 and 40.2 μS, respectively. For (60) mode, the peaks appear at 91.16 kHz and 92.01 kHz for plates A and B, respectively, reaching conductances of 67.8 and 115.7 μS.

Table 6.

Conductance measurement results for plates A and B in (50) and (60) modes.

Based on the obtained results, the characteristic frequencies of each plate can be identified and their conductance quantified. In comparative terms, it can be seen that plate B exhibits higher conductance in (60) mode compared to plate A, which suggests better electrical coupling in this mode. These results provide a basis for the evaluation of subsequent dynamic tests.

3.2. Linear Displacement and Angular Velocity Test

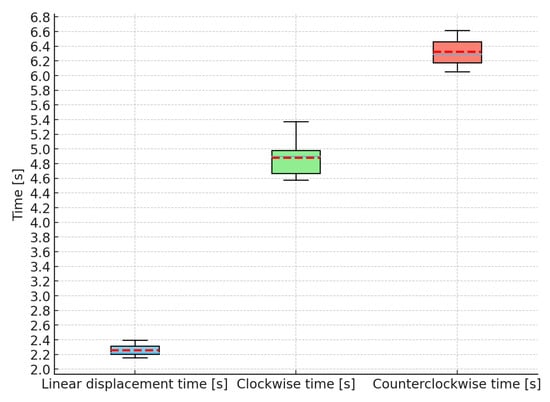

This test involves the study of linear displacement and both clockwise and counterclockwise rotation of the uncontrolled robot. It is worth noting that the linear displacement tests were conducted exclusively in the forward direction. However, (50) and (60) modes enable bidirectional motion, as illustrated in Figure 4, and have been adopted in prior works, such as [7]. In contrast, our method provides full trajectory control, allowing the system to move forward and execute a 180° turn, effectively reversing its direction. Moreover, the proposed trajectory-control strategy is specifically based on combining forward displacements with bidirectional rotations to achieve navigation. As an initial test to determine linear displacement, the travel time of the robot along a 20 mm path was measured. The experiment was conducted on a mm glass plate printed with a 5 mm grid; start and end marks were placed 20 mm apart. Each trial was executed using a timer that triggered the robot’s excitation at the start mark and stopped it at the end mark, recording the elapsed time. The robot was always positioned at the same initial point and driven at 60 kHz with a 65% duty cycle on plates A and B. Before each trial, the battery was verified to be fully charged (7.4 V). A total of n = 10 consecutive trials were conducted, and the time required for each repetition was recorded, yielding a mean time of . Based on this value, the displacement velocity was calculated using the expression , considering a fixed distance of , which resulted in an average velocity of . The boxplot of the displacement test is shown in light blue in Figure 19, where low variability between trials can be observed, with a standard deviation of 0.086 s and no outliers detected.

Figure 19.

Boxplots of the 20 mm linear displacement time and the 180° clockwise and counterclockwise rotation times ().

To determine the rotational speed in both clockwise and counterclockwise directions, tests were conducted on the same surface used for the linear displacement test, setting a reference angle of 180°. For clockwise rotation, plates A and B were excited at frequencies of 60 kHz and 91 kHz, respectively, applying a duty cycle of 65% in both cases. In the counterclockwise test, the actuators were excited at frequencies of 92 kHz and 60 kHz, maintaining the same duty cycle. The average time recorded in the rotation tests was for clockwise and for counterclockwise motion. Based on these values, and applying the expression with a fixed angle of , the corresponding average angular velocities were calculated as and , respectively.

Figure 19 presents the boxplots corresponding to the rotation times. From these results, the standard deviation was calculated as for clockwise rotation and for counterclockwise rotation. These values indicate moderate variability in the trials, slightly higher in the clockwise direction.

The relative variation in the recorded times was low, indicating high repeatability and consistency throughout the experiment. Overall, the results show that, despite the small differences between the two rotation directions, the robot maintains stable and repeatable performance, confirming the system’s capability to generate consistent and reproducible movements.

The experimental setup and robot locomotion can be observed in the Supplementary Video (Video S1).

3.3. Trajectory Error Tests

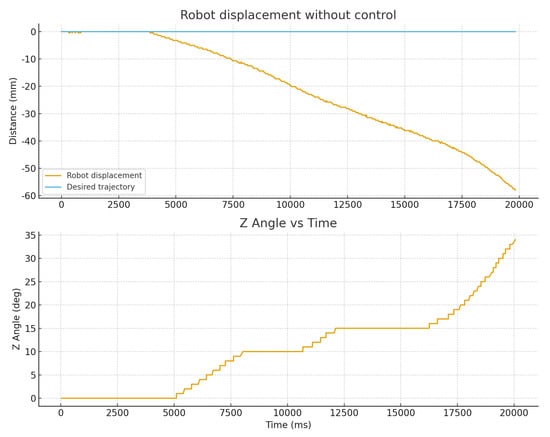

The open-loop trajectory (without trajectory control) was evaluated by exciting actuators A and B at frequencies of 61 kHz and 63 kHz and a duty cycle of 65%, respectively. To analyze the movement, a trajectory was defined on the horizontal axis , and the robot position was measured using a fixed camera placed parallel to the surface of the squared glass. Figure 20 (robot displacement without control) shows the measured linear trajectory and the desired reference over 20 s. In this first open-loop test, the trajectory error was calculated using , representing the linear deviation in millimeters. At the end of the linear displacement test ( s), the robot accumulated a linear error of 58 mm relative to the reference.

Figure 20.

Open-loop motion of the miniature robot under excitation at 60 kHz (65% duty cycle), and angular deviation of the robot measured with the gyroscope during open-loop operation. The experiment is shown in the Supplementary Video (Video S2).

A second open-loop test was performed to evaluate the robot’s rotational drift using the gyroscopic sensor. Figure 20 (Z Angle vs. Time) shows the accumulated angular deviation of the robot with respect to the initial reference . At the end of the test (), the angular error reached approximately 35°. These values were obtained via the Bluetooth communication integrated into the microcontroller, which was used solely for telemetry to monitor IMU sensor data and control signals, enabling real-time data acquisition with a maximum latency of approximately 200 ms.

The angular deviations in the trajectory were evaluated using the metrics: mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and the maximum absolute error ().

The values in Table 7 show considerable deviations with respect to the reference, confirming the need to implement a closed-loop controller.

Table 7.

Trajectory deviation metrics in open-loop condition.

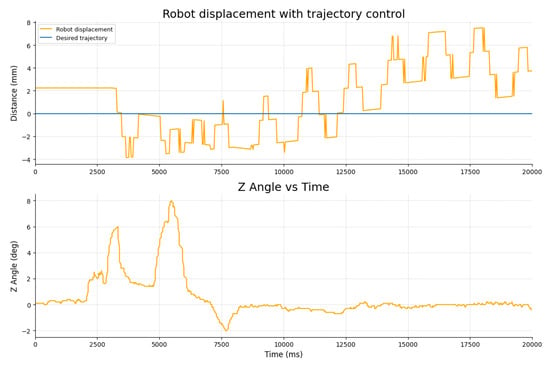

For the close-loop trajectory control, a PD controller designed in Section 2.5.4 was applied. A reference was set on the horizontal axis , and the robot position was measured using a fixed camera placed parallel to the squared glass surface. Figure 21 (robot displacement with trajectory control) shows the measured trajectory and the reference during a 20 s interval after applying the controller; in this graph, an average error of approximately 4 mm is observed between the reference trajectory and the robot position.

Figure 21.

Closed-loop trajectory control performance using a PD controller and closed-loop angular response obtained from the gyroscope output. The experiment can be observed in the Supplementary Video (Video S3).

The flat segment observed between 0 and ∼3000 ms in Figure 21 (robot displacement with trajectory control) corresponds to the initialization stage of the vision-based tracking system. During this interval, the robot remains stationary, with piezoelectric excitation/actuation disabled, and the closed-loop controller has not yet been enabled. The camera detects the robot marker and the tracking algorithm defines the initial reference. Therefore, the measured displacement stays constant and reflects only the initial offset of ∼2.2 mm relative to the reference. After 3000 ms, the PD controller is activated and actuation begins, producing the subsequent displacement response as the robot starts following the reference trajectory.

To validate the controller response, the gyroscope output was analyzed again, setting a reference of and recording the robot response for 12 s. Figure 21 (Z Angle vs. Time) presents the angular response obtained.

Table 8 summarizes the mean of ten trials conducted under equivalent experimental conditions on the same surface.

Table 8.

Trajectory deviation metrics in closed-loop condition.

The values show a significant reduction in trajectory tracking error through the application of the PD controller, decreasing both the mean error and the maximum absolute error compared to the open-loop case.

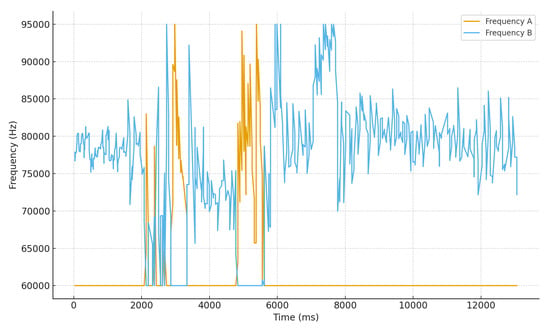

In Figure 22, the excitation frequency of the control signal sent to piezoelectric actuators A and B is presented as a function of time.

Figure 22.

Control signal applied to actuators A and B as a function of time.

3.4. Comparison with Related Works

To validate the proposed design, Table 9 presents a comparative analysis with other piezoelectric microrobots of comparable specifications reported in the literature. The comparison considers size, mass, speed, power consumption, autonomy and trajectory control. As observed, the proposed robot exhibits considerable autonomy. Although its speed is lower than that of some existing platforms, the most significant contribution of this work lies in the successful implementation of a closed-loop trajectory controller. Unlike most reported microrobots, which lack feedback mechanisms, this study demonstrates the feasibility of integrating control strategies without compromising the critical constraints inherent to insect-scale robotics.

Table 9.

Comparison with microrobots of comparable specifications reported in the literature.

4. Discussion

A key finding is the experimental validation of high-precision autonomous navigation. The system achieved a linear speed of 8.87 mm/s in straight-line motion and angular velocities of 37.87°/s and 28.30°/s in clockwise and counterclockwise rotation, respectively, maintaining a straight trajectory with an MAE of only 0.83°. This emphasis on closed-loop trajectory-tracking accuracy distinguishes our robot from previous works that prioritized open-loop speed. For instance, studies such as [7] reported substantially higher linear speeds (70 mm/s) using a similar standing-wave (SW) actuation approach in 7.4 g robots, but they lacked the onboard sensing and closed-loop correction achieved in this prototype. While the open-loop system in [7] attains high speeds, it cannot compensate for the drift inherent to piezoelectric actuators, which leads to deviations when tracking a straight trajectory. In contrast, our approach prioritizes trajectory fidelity over peak speed. By implementing closed-loop control, our robot actively compensates for drift, enabling straight-line motion at the expense of reduced speed. Therefore, the key contribution of this work is autonomous capability for precise navigation rather than maximum speed.

The simplified excitation circuit, previously described in the literature [31,32], was empirically validated in this study, confirming its suitability for generating high excitation voltages up to 81.2 Vpp at 100 kHz with low currents of about 30 mA. The use of two 7.4 V, 30 mAh batteries optimized the balance between speed, force, and endurance. Compared with Flyback circuits reported in other studies [24,41,42,43], the proposed design offers advantages in weight, size, and power consumption parameters that are critical for miniaturized robotic platforms. This electronic optimization represents a tangible step toward the full integration of autonomous systems at reduced scales.

The successful implementation of the Seeed Studio nRF52840 XIAO microcontroller was essential, validating the feasibility of integrated control in miniature robots and enabling wireless communication for real-time monitoring. The effective integration of piezoelectric actuators, compact electronics, and embedded autonomous control consolidates an efficient and versatile miniaturized platform focused on small-scale control research. A crucial factor in the robot’s autonomy was battery performance: the operating current consumption (estimated between 50 mA and 60 mA) depleted the 30 mAh battery in approximately 24 min. This consumption is mainly associated with the control, power, and Bluetooth communication modules used for real-time telemetry and data logging. Such limited endurance remains a primary constraint of the current platform, in marked contrast to the multi-hour operation reported in [7], and should be a major target for future optimization.

Finally, the results open promising research directions toward the implementation of integrated machine-learning techniques (TinyML). Having established a platform capable of stable and programmable motion control, the next logical step is to explore real-time decision-making and advanced perception systems, positioning the developed platform as a solid foundation for the advancement of intelligent and autonomous microrobotics.

5. Conclusions

In this work, a miniature robot with a total weight of 9 g and dimensions of 26 × 26.95 × 24.2 mm was developed and experimentally validated. The robot was propelled by 3D-printed resonators equipped with PZT piezoelectric patches, enabling both linear and rotational motion. The prototype achieved linear speeds of 8.87 mm/s and angular velocities of 37.88°/s and 28.31°/s in the clockwise and counterclockwise directions, respectively. These displacements were obtained through the excitation of SW waves, generated by a compact and low-power microcontroller capable of producing pulse-type signals at frequencies between 60 and 95 kHz with a duty cycle of 65%. The signals were amplified by a resonant LC circuit powered by two 3.7 V–30 mAh batteries.

The design of the LC circuit was based on previous studies and an experimental analysis aimed at determining the optimal Vpp values and operating frequencies that prevent waveform distortion and excessive current peaks. As a result, an inductor of 470 µH was selected with duty cycles between 50% and 65%, allowing operation within the 60–95 kHz range, where the flexural (50) and (60) modes are excited to produce the robot’s motion.

Finally, using the Seeed Studio XIAO nRF52840 Sense microcontroller, chosen for its compact size, low power consumption, and integrated IMU sensor, a proportional–derivative controller was implemented to maintain the robot’s straight-line trajectory. Experimental tests reported an MAE of 0.83°, demonstrating the feasibility of embedded control on a small scale and its potential for future applications of multimodal locomotion control techniques, improved estimation algorithms, and the transition toward fully autonomous microrobotic systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/act15010023/s1, Video S1—Experimental setup and robot locomotion (linear and rotational). Locomotion of the miniature robot under standing-wave (SW) excitation. Linear displacements and clockwise/counterclockwise rotations are observed, with close-ups of the resonator–leg contact and of the surface used for motion tracking. Video S2—Open-loop linear displacement at 61 kHz and 63 kHz (65% duty cycle). Open-loop trials showing the frequency-dependent response. Frequencies of 61 kHz and 63 kHz (PWM at 65%) are applied to actuators A and B, evidencing forward motion. Video S3—Closed-loop trajectory control with an embedded PD controller. Demonstration of on-board sensing and control: yaw feedback via IMU, filtered (Kalman) estimation, and a proportional–derivative (PD) controller that regulates the excitation frequency to maintain a straight path. The video shows representative linear and angular responses under closed-loop operation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.R.-D. and J.L.S.-R.; software B.R.Z.C. and J.R.H.V.; investigation, B.R.Z.C. and J.R.H.V.; data curation, B.R.Z.C. and J.R.H.V.; writing—original draft preparation, B.R.Z.C. and J.R.H.V.; writing—review and editing, V.R.-D., and J.L.S.-R.; project administration, V.R.-D., and J.L.S.-R.; funding acquisition, V.R.-D., and J.L.S.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, Spain, through MCIN/AEI and FEDER “ERDF A way of making Europe” under Grant PID2023-146163OB-I00 and Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, Quito-Ecuador.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study and due to technical/time limitations. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bzapata@ups.edu.ec.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Siciliano, B.; Khatib, O. (Eds.) Springer Handbook of Robotics, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, R.; Lungarella, M.; Iida, F. The Challenges Ahead for Bio-Inspired ’Soft’ Robotics. Commun. ACM 2012, 55, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, M.; Cichella, V.; Lamuta, C. Bioinspired Soft Robotics: State of the Art, Challenges, and Opportunities. Curr. Robot. Rep. 2023, 4, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, H. Bioinspired Sensors and Applications in Intelligent Robots: A Review. Robot. Artif. Intell. 2023, 10, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandari, V.K.; Eom, S.H.; Park, H.; Lee, S.W.; Jeong, U. System-Engineered Miniaturized Robots: From Structure to Intelligence. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2021, 3, 2000284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, C.; Dong, L.; Zhao, J. A Review of Microrobot’s System: Towards System Integration for Autonomous Actuation In Vivo. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Palma, M.R.; Robles-Cuenca, D.; Ruiz-Díez, V.; Hernando-García, J.; Sánchez-Rojas, J.L. Vibration Propulsion in Untethered Insect-Scale Robots. Robotics 2024, 13, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Ma, E.; Chen, H.; Lin, F.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Niu, Y.; Yu, P.; Wang, C. Locomotion for Insect-Scale Robots with Bionic Strategies: A Review. J. Field Robot. 2025, 42, 1586–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.M.; Kim, H.T.; Yi, B.J. An Omnidirectional Mobile Millimeters Size Micro-Robot. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2008, 5, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, V.; Singh, R. A Review of Bio-Inspired Actuators and Their Potential for Autonomous Systems. Actuators 2025, 14, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Li, C.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y. A double-beam piezoelectric robot based on the principle of two-mode excitation. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2024, 369, 115154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Xue, N.; Qiu, B.; Qin, B.; Zhao, Q.; Fang, G.; Yao, Z.; Zhou, W.; Sun, X. Recent Design and Application Advances in Micro-Electro-Mechanical System (MEMS) Electromagnetic Actuators. Micromachines 2025, 16, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Zhao, X. A spatial 3-DOF piezoelectric robot and its speed-up trajectory based on improved stick-slip principle. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 150, 107247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Díez, V.; Hernando-García, J.; Toledo, J.; Ababneh, A.; Seidel, H.; Sánchez-Rojas, J.L. Comparative Study of Traveling and Standing Wave-Based Locomotion of Legged Bidirectional Miniature Piezoelectric Robots. Actuators 2021, 10, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Chen, W.; Tao, X.; Chen, Z. Standing Wave Bi-directional Linearly Moving Ultrasonic Motor. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 1998, 45, 1133–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelin, G.; Sonmez, M.; Pelin, C.E. The Use of Additive Manufacturing Techniques in the Development of Polymeric Molds: A Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Fu, J. Additive Manufacturing: A Comprehensive Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formlabs. 3D Printing Materials Library. Sitio Web. 2025. Recuperado de. Available online: https://formlabs.com/materials/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Ruiz-Díez, V.; García-Caraballo, J.L.; Hernando-García, J.; Sánchez-Rojas, J.L. 3D-Printed Miniature Robots with Piezoelectric Actuation for Locomotion and Steering Maneuverability Applications. Actuators 2021, 10, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Deng, J.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y. A Snail-Inspired Traveling-Wave-Driven Miniature Piezoelectric Robot. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5, 102201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Cao, L.; Lu, G.; Wang, P.; Ran, L.; Peng, B. Untethered Soft Microrobot Driven by a Single Actuator for Agile Navigations. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 61810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, M.; Ahler, C.; Nagpal, R. Kilobot: A Low Cost Scalable Robot System for Collective Behaviors. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Saint Paul, MN, USA, 14–18 May 2012; pp. 3293–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. Miniature Mobile Robot Using Only One Tilted Vibration Motor. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, B.; Zufferey, R.; Doshi, N.; Helbling, E.F.; Whittredge, G.; Kovac, M.; Wood, R.J. Power and Control Autonomy for High-Speed Locomotion with an Insect-Scale Legged Robot. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, S.B.; Helbling, E.F.; Chirarattananon, P.; Wood, R.J. Using a MEMS gyroscope to stabilize the attitude of a fly-sized hovering robot. In Proceedings of the International Micro Air Vehicle Conference and Competition (IMAV), Delft, The Netherlands, 12–15 August 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceramic, P. PI Ceramic Material Data. Datasheet. 2025. Available online: https://www.piceramic.com/fileadmin/user_upload/physik_instrumente/files/datasheets/PI_Ceramic_Material_Data.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- PI Ceramic. Piezo Actuator Materials Tutorial; Technical Tutorial on Piezoelectric Actuator Materials; Physik Instrumente (PI) GmbH & Co. KG: Lederhose, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Formlabs Inc. Rigid 10K Resin—Technical Data Sheet (TDS). Rev. 03. 2022. Available online: https://formlabs-media.formlabs.com/datasheets/2001479-TDS-ENUS-0.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- Seeed Studio. Seeed Studio XIAO nRF52840 Sense Product Specification v1.5; Seeed Studio: Shenzhen, China, 2024. Available online: https://files.seeedstudio.com/wiki/XIAO-BLE/nRF52840_PS_v1.5.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Rovai, M.J. XIAO: Big Power, Small Board; GitHub eBook. 2023. Available online: https://mjrovai.github.io/XIAO_Big_Power_Small_Board-ebook/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Robles-Cuenca, D.; Ramírez-Palma, M.R.; Ruiz-Díez, V.; Hernando-García, J.; Sánchez-Rojas, J.L. Miniature Autonomous Robot Based on Legged In-Plane Piezoelectric Resonators with Onboard Power and Control. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EDN. Increase Piezoelectric Transducer Acoustic Output with a Simple Circuit. 2022. Available online: https://www.edn.com/increase-piezoelectric-transducer-acoustic-output-with-a-simple-circuit/ (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Ramos, R.C.; Devers, C.J. The iPad as a virtual oscilloscope for measuring time constants in RC and LR circuits. Phys. Educ. 2020, 55, 023003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LiPoly Batteries. 30mAh LiPo Battery 3.7V—Model LP401010. Datasheet. Available online: https://lipolybatteries.com/product/30mah-lipo-battery-lp401010-4mm-thickness-3-7-v-battery (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Gharghan, S.K.; Nordin, R.; Ismail, M. An Ultra-Low Power Wireless Sensor Network for Bicycle Torque Performance Measurements. Sensors 2015, 15, 11741–11768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formlabs. Clear Resin—Safety Data Sheet (SDS). 2022. Available online: https://formlabs-media.formlabs.com/datasheets/1801037-SDS-ENUS-0.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- STMicroelectronics. LSM6DS3TR-C: iNEMO inertial module: Always-on 3D accelerometer and 3D gyroscope, 2017. Datasheet, DocID030071 Rev 3. Available online: https://www.st.com/resource/en/datasheet/lsm6ds3tr-c.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Zapata, B.; Heredia, J.; Proaño, J. Design and Evaluation of the PID, SMC and MPC Controllers by State Estimation by Kalman Filter in the TRMS System. In Proceedings of the Innovation and Research—A Driving Force for Socio-Econo-Technological Development; Botto-Tobar, M., Vizuete, M.Z., Cadena, A.D., Eds.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1277, pp. 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Yu, G.; Li, H.; Zhang, N. A Novel MEMS Gyroscope In-Self Calibration Approach. Sensors 2020, 20, 5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhan, W.; Liu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Qi, M.; Leng, J.; Wei, L.; Han, S.; Wu, X.; Yan, X. A Wireless Controlled Robotic Insect with Ultrafast Untethered Running Speeds. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Liu, X.; Cacucciolo, V.; Imboden, M.; Civet, Y.; El Haitami, A.; Cantin, S.; Perriard, Y.; Shea, H. An autonomous untethered fast soft robotic insect driven by low-voltage dielectric elastomer actuators. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4, eaaz6451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Feng, B.; Wang, D.; Liu, T.; Zhou, H.; Li, H.; Qu, S.; Yang, W. S2worm: A Fast-Moving Untethered Insect-Scale Robot with 2-DoF Transmission Mechanism. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 6758–6765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Wu, Y.; Yim, J.K.; Chen, H.; Miao, Z.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Qiu, W.; et al. Electrostatic footpads enable agile insect-scale soft robots with trajectory control. Sci. Robot. 2021, 6, eabe7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.