Abstract

The electrification of vehicle chassis systems is increasingly important due to benefits such as vehicle lightweighting, enhanced safety, and design flexibility. However, faults in these systems can seriously compromise safety, making Fault Tolerant Control (FTC) essential. This study investigated FTC of four-wheel independent Electro-Mechanical Brake (EMB) actuators and proposed a method to prevent lane departure under actuator faults. Fault Tolerant Robust Control (FTRC) of four-wheel independent EMB actuators using Time Delay Control (TDC) was applied without Fault Detection and Diagnosis (FDD) to maintain real-time capability, and without steering control to reduce system complexity. In addition, for actuator faults causing large lateral displacements, a control strategy applying relative weighting to lateral velocity and yaw rate was introduced. The results showed that, even when the faults of the EMB actuators were severe and asymmetric between the left and right sides of the vehicle, overall vehicle stability—including lateral and yaw motions—was preserved through the proposed FTRC approach without FDD and steering control. Moreover, the relative weighting strategy effectively reduced lateral displacement, preventing lane departure. These findings highlight the significance of the proposed method for ensuring FTRC in electrified braking systems, enhancing safety, reducing lateral displacement, preventing lane departure, ensuring real-time capability, and reducing the complexity required in practical FTC.

1. Introduction

The electrification of vehicle chassis systems has been increasingly recognized as essential, owing to its advantages such as vehicle lightweighting, enhanced stability and safety, improved energy efficiency, greater design flexibility, and increased ease of manufacturing [1,2,3,4,5]. However, the electrification of vehicle chassis systems, particularly in braking and steering systems, can significantly affect vehicle safety in the event of a fault. Therefore, the implementation of Fault Tolerant Control (FTC) is essential [6,7,8]. In response to this necessity, this study investigates an FTC of four-wheel independent Electro-Mechanical Brake (EMB) actuators for a four-wheel vehicle, as well as a control method to prevent potential lane departure under actuator fault conditions. Table A1 in Appendix A presents a comparison between the conventional hydraulic brake system, which is currently in widespread use, and the EMB system addressed in this study.

Rongrong Wang and Junmin Wang [9] presented an FTC approach for four-wheel independently driven electric vehicles. An active fault diagnosis approach is proposed to explicitly isolate and evaluate the fault. Based on the active fault diagnosis, FTC redistributes the control efforts of all the wheels to relieve the torque demand on the faulty wheel. Simulations using a high-fidelity CarSim full vehicle model show the effectiveness of the proposed active fault diagnosis and FTC approaches in various driving conditions. Hui Jing et al. [10] presented an FTC strategy to improve lateral stability and maneuverability of a four-wheel independently actuated electric ground vehicle with active front steering. Both vehicle parameter uncertainties and actuators faults are considered, making the proposed control method robust to the uncertainties and actuator faults. A robust H∞ dynamic output feedback controller was designed to control the vehicle, which can be implemented without the slip angle or lateral speed measurement, with only the yaw rate measurement. Simulation results based on a full-vehicle model in Carsim validate the effectiveness of the proposed control approach. S. Kim and K. Huh [6] proposed the integration of regenerative braking as well as EMB braking to achieve the FTC of the EMB. The fault tolerant scheme is constructed using the sliding mode controller. The proposed controller and strategies are verified in the EMB HILS (Hardware In the Loop Simulation) unit for various conditions. Xuanhao Cao et al. [7] proposed an FTC strategy for path following of autonomous vehicles considering faults in the braking actuators. A gain-scheduling linear parameter-varying synthesis H∞ robust Fault Tolerant Controller is designed to ensure autonomous vehicle stability and safety. This article fully considers the effects of braking actuator faults in the process of the controller design, and it can implement the FTC for the brake actuators by combining the steer-by-wire system and the Electro-Hydraulic Brake (EHB) system. The experiments in the HIL system are carried out to verify the effectiveness and real-time performance of the proposed control strategy, and the results show that the proposed control strategy can improve the vehicle’s stability and safety under a wide range of types of faults in the EHB system. Guanjie Cui et al. [11] proposed a path-tracking linear parameter time-varying/H∞ FTC strategy under Electronic pneumatic Braking System (EBS) actuator failure in intelligent commercial vehicles. EBS actuator fault coefficients are evaluated in real time to determine whether the EBS is faulty or not, and the gain scheduling linear parameter time-varying robust H∞ FTC strategy is adopted for realizing FTC of the EBS actuator fault. The results demonstrate that the control strategy designed in this paper redistributes the braking torque and synergizes with the steering system to enhance vehicle stability, thereby improving vehicle safety in the EBS failure mode. Taeho Jo et al. [12] presented a method for diagnosing the actuator’s stuck state and FTC of Anti-lock Brake System (ABS). The electronic circuit unit (ECU) monitors the fault detection depending on the operating status of brake actuator. In response to the actuator’s stuck state, the ECU converts the alternative control method. Experimental results validate the effectiveness of the proposed fault diagnosis method and the presented FTC method.

As reviewed in previous studies, most approaches performed Fault Detection and Diagnosis (FDD) first and then utilized the obtained information to implement FTC [6,7,9,11,12]. In real-time control, performing FDD within a limited amount of time often leads to reduced accuracy of FDD. Conversely, improving the accuracy of FDD can compromise the real-time performance [13,14]. Therefore, in practical real-time control, it is challenging to perform FDD and then use the obtained information to execute FTC [13,14]. In addition, some of the previous studies also incorporated steering control to ensure vehicle lateral and yaw dynamics stability, safety, and/or maneuverability [7,10,11]. However, in such cases, when a fault occurs in the vehicle’s driving or braking actuators during longitudinal driving or braking control, ensuring vehicle lateral and yaw dynamics stability and safety may require the additional incorporation of steering control, thereby increasing system complexity. Therefore, issues related to vehicle lateral and yaw dynamics stability and safety, which may arise due to actuator faults in the driving or braking system during longitudinal driving or braking control, should be addressed within the longitudinal control itself, whenever possible or as needed.

Therefore, to ensure the real-time capability of control, this study aims to apply an FTC method that is robust to faults, without relying on FDD or utilizing FDD information only in the case of severe faults. Accordingly, a Fault Tolerant Robust Control (FTRC) of four-wheel independent EMB actuators was intended to be applied using the Time Delay Control (TDC) [15], which is capable of modeling faults as system parameter variations and external disturbances, and is robust against system parameter variations, external disturbances, and unmodeled uncertain dynamics. In addition, to reduce the complexity of the control, this study aimed to address potential issues related to vehicle lateral and yaw dynamics stability and safety caused by EMB actuator faults, solely through an FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators without incorporating steering control. Moreover, in situations where significant lateral displacement may lead to a potential lane departure, a lane departure prevention control strategy was addressed by reducing the lateral displacement through a control approach that applies relative weighting to the lateral velocity and yaw rate. To the best of our knowledge, the content addressed in this study has rarely been dealt with in previous research.

This study is expected to make a significant contribution to the FTC, which is essential for the electrification of vehicle brake actuators, reductions in lateral displacement and, furthermore, the prevention of lane departure in the event of brake actuator faults. Moreover, the FTRC of the four-wheel independent EMB actuators using TDC proposed in this study ensures robustness against actuator faults required in practical FTC by applying the TDC as a robust control technique. As mentioned earlier, because this control does not employ FDD except in the case of severe faults, it is expected to contribute to improved real-time control performance compared with most previous studies that rely on FDD. Moreover, by not incorporating steering control, this control is expected to reduce control complexity compared with previous studies that involve steering control. In addition, the use of relative weighting to the lateral velocity and yaw rate in this control provides a unique feature not reported in prior studies, as mentioned earlier, enabling reduction in lateral displacement and further contributing to lane departure prevention capabilities.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 addresses the vehicle dynamics and the fault model of the EMB actuators. Section 3 discusses the FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators using TDC. In addition, a control method applying relative weighting to lateral velocity and yaw rate is presented to reduce lateral displacement and thereby prevent lane departure. Section 4 verifies the results of the control methods presented in Section 3 through simulations. And Section 5 presents the conclusions.

2. Vehicle Dynamics and Fault Model of EMB Actuators

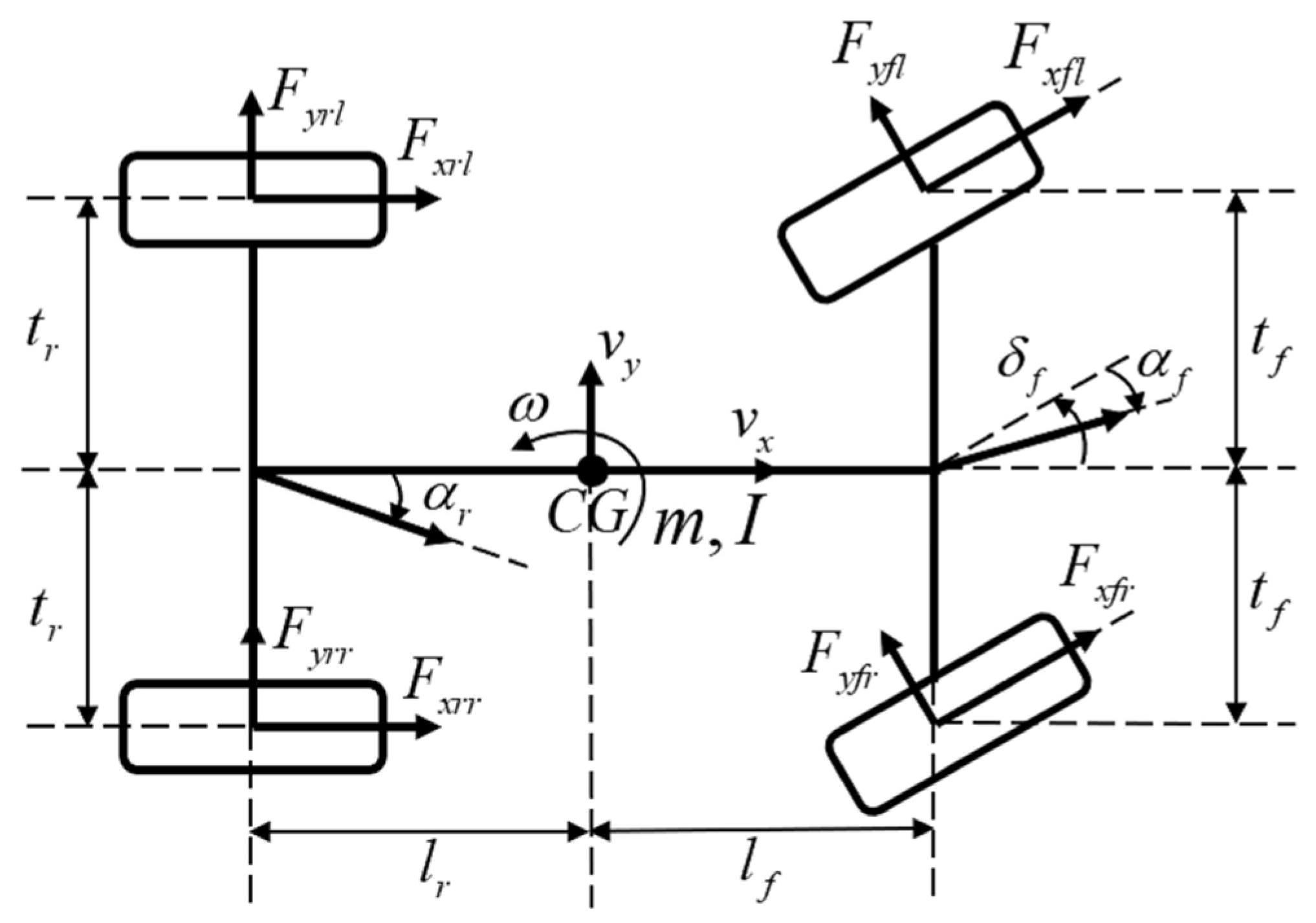

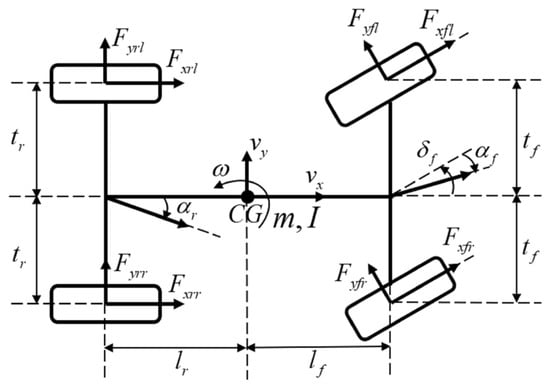

Figure 1 illustrates the vehicle dynamics model. The planar vehicle dynamics with 3 Degrees Of Freedom (DOF)—namely, longitudinal, lateral, and yaw motions—can be described as follows [9].

Here, denote the longitudinal velocity, lateral velocity, and yaw rate, respectively. represent the vehicle mass and yaw moment of inertia, respectively. denotes the front steering angle. and represent and , respectively. represent the distances from the vehicle’s center of gravity to the front and rear axles, respectively. denote the half-track widths of the front and rear axles, respectively. represent the longitudinal and lateral tire force vectors, which can be expressed as follows.

Here, in the subscript of , denote the front and rear axles, respectively, while in the subscript of , denote the left and right wheels, respectively. Accordingly, represent the longitudinal and lateral tire forces acting on each wheel , respectively.

Figure 1.

Vehicle Dynamics Model.

The following equation represents the rotational dynamics of the wheel under the applied braking torque [6].

Here, denotes the rotational moment of inertia of the wheel, is the angular velocity of the wheel, represents the braking torque applied to the wheel, and is the effective radius of the wheel tire. By rearranging Equation (3) with respect to the longitudinal tire force , the following expression is obtained.

The lateral tire force at the wheel can be expressed as follows under the assumption of a small tire side-slip angle.

Here, denotes the tire cornering stiffness of the wheel, and represents the tire slip angle of the wheel. In this study, it is assumed that the tire cornering stiffness and tire slip angle are identical for the left and right wheels at the same axle, as shown in Equation (5); that is, , , , and .

The following represents the fault model of the EMB actuator applied to the wheel [16].

Here, denotes the actual brake torque applied to the wheel, as mentioned above, is the loss-of-effectiveness gain associated with the actual brake torque applied to the wheel, represents the desired brake torque to be applied to the wheel, and is the additional brake torque applied to the wheel, which is assumed to be bounded.

3. FTRC of Four-Wheel Independent EMB Actuators

3.1. Method Using TDC

This study addresses FTC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators, aiming to address potential issues related to vehicle lateral and yaw dynamics stability and safety caused by EMB actuator faults, solely through the FTC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators without incorporating steering control. Therefore, in this study, steering control is not applied, and for convenience, the desired path is set as a straight line, allowing the front wheel steering angle to be set to zero; i.e., . If , Equation (1) becomes

As shown in Equation (7), becomes uncontrollable by the brake actuator control input , as also indicated in Equation (4). The controllable states by the brake actuator control input are , and by applying the input-output linearization [17] with as the output , the following external dynamics [17] can be derived.

Here, for convenience, are redefined as , respectively. It is assumed that for all , and that . are as follows.

are the ratios of the front wheel vertical tire force to the rear wheel vertical tire force on the left and right sides of the vehicle, respectively, and are the ratios of the front wheel brake torque to the rear wheel brake torque on the left and right sides of the vehicle, respectively, as follows [6,9,18,19].

Here, denotes the vertical tire force acting on the wheel.

By applying Equation (11) to Equation (8), the following expression is obtained.

By applying TDC [15] to generate the control input for Equation (12), the following expression is obtained.

Here, represents the time delay, which is typically set equal to the control sampling time [15]. is the desired output of , and is the derivative of the desired output. is a control gain matrix selected to determine the response characteristics of the error dynamics. is a control gain matrix selected based on of Equation (12), and is as follows.

Here, , are the control gains selected based on of Equation (12). In conventional TDC, the control gain matrix is typically determined by estimating system parameters. However, in this study, to focus on faults, it is assumed that the nominal system parameters are known, and instead, the loss-of-effectiveness gain , which represents the severity of the fault, is estimated to determine the control gain matrix . For the TDC to be stable, the following condition must be satisfied [15].

Here, is a 2 × 2 identity matrix. That is, if Equation (15) is satisfied, the TDC given in Equation (13), when applied to the external dynamics described by Equation (12), ensures the stability of the control system for the external dynamics.

When the TDC in Equation (13) is designed to satisfy the condition in Equation (15) and applied to the external dynamics described in Equation (12) to control the external dynamics output to track , the investigation of the stabilizability of the internal dynamics [17] with respect to in Equation (7) reveals that it is stabilizable as follows.

Here, the coefficient of is positive, and the right-hand side is bounded. Therefore, the internal dynamics with respect to are stable.

Therefore, the FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators using TDC can stabilize the external dynamics with respect to the output , and ensure the stabilizability of the internal dynamics of . As a result, this control method can ensure the overall stability of the full vehicle system, including both internal and external vehicle dynamics.

As mentioned in the introduction, the variation in the loss-of-effectiveness gain in Equation (12) can be regarded as a variation in system parameters, while can be considered as a disturbance. Furthermore, in Equation (12), if both become zero on the same side of the vehicle—i.e., either or —then the matrix becomes singular, and the external dynamics in Equation (12) becomes uncontrollable.

3.2. Method Using TDC with Relative Weighting to Lateral Velocity and Yaw Rate

The output in Section 3.1 is modified based on the look-ahead concept [20] as follows.

Here, is the relative weighting factor applied to the lateral velocity and yaw rate. As in Section 3.1, by applying the input-output linearization [17] to the output and utilizing Equation (11), the following external dynamics [17] can be derived.

Here, is the same as in Equation (9), and is given as follows.

By applying TDC [15] to generate the control input for Equation (18), the following expression is obtained.

As in Section 3.1, here, denotes the time delay, is the desired output of , and is the derivative of the desired output. is a control gain matrix selected to determine the response characteristics of the error dynamics. is a control gain matrix selected based on of Equation (18), and is as follows. In this study, the control gain matrix is determined using the same method as that used for selecting in Section 3.1.

Here, for the TDC to be stable, the following condition must be satisfied [15].

That is, if Equation (22) is satisfied, applying TDC in Equation (20) to the external dynamics described by Equation (18) ensures the stability of the control system for the external dynamics.

By controlling the external dynamics as described above, can be controlled to its desired value , and can be controlled to its desired value . Although the individual components of the second output—namely, the lateral velocity and the yaw rate —cannot be controlled independently to their respective desired values—namely, the desired lateral velocity and the desired yaw rate —their weighted combination can be controlled to its desired value . As mentioned in Section 3.1, steering control is not applied in this study, and the desired path is assumed to be a straight line for simplicity. Therefore, the desired lateral velocity is zero—i.e., —to maintain the straight-line path. Likewise, the desired yaw rate is also zero, , to keep the vehicle on the straight-line path. Consequently, is a valid control objective. In practice, if the system does not converge exactly to zero due to steady-state error, it may still converge to a small bounded value ; i.e., . In Section 3.1, it was shown that the state is stabilizable but not controllable by the brake actuator control input. In this section, by redefining the second output as , the uncontrollable state is not directly controlled, but rather controlled indirectly through control of the second output , which is a function of both and . In other words, the controllable state , which can be controlled by the brake actuator control inputs, is utilized to indirectly control the lateral velocity . Through this indirect control of the lateral velocity, the lateral motion of the vehicle can be controlled, thereby reducing lateral displacement and contributing to the prevention of lane departure.

In this section, controllability is achieved by controlling and . However, represents the control of a combined value , not the individual control of . Therefore, to verify the overall stability of the vehicle system, the stabilizability of the states must be examined. If the stabilizability can be confirmed for one of the states within , since is considered controllable, and by the principle that controllability implies stabilizability, the remaining state is also stabilizable. Here, similar to Section 3.1, the stabilizability of is analyzed through the internal dynamics corresponding to . The internal dynamics of is given as follows.

In this section, the output vector is controlled such that and . Therefore, by substituting and into the above equation, it can be rewritten as follows.

Here, it can be observed that the right-hand side is bounded. Therefore, if the coefficient of the term is positive—i.e., if Equation (25) or Equation (26) is satisfied—the internal dynamics with respect to are stable. In other words, is stabilizable.

Here, if , then , which implies that the system is uncontrollable. Therefore, it is assumed that . As a result, as explained earlier, is also stabilizable.

Therefore, in this section, the FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators using TDC with relative weighting to lateral velocity and yaw rate can stabilize the external dynamics associated with the output , and ensure the stabilizability of the internal dynamics of . As a result, this control method is capable of stabilizing the entire vehicle system, which includes both the internal and external vehicle dynamics.

As mentioned in the introduction, the variation in the loss-of-effectiveness gain in Equation (18) can be regarded as a variation in system parameters, while can be considered as a disturbance. Furthermore, as discussed in Section 3.1, in Equation (18), if both become zero on the same side of the vehicle—i.e., either or —then the matrix becomes singular and the external dynamics in Equation (18) becomes uncontrollable.

4. Simulation

4.1. Simulation of the FTRC of Four-Wheel Independent EMB Actuators Using TDC Proposed in Section 3 Applied to the Vehicle Dynamics in Section 2

The control target considered in this section is based on the vehicle dynamics and parameters described in Section 2, including , , , , , , , , the effective radius for all wheels , and the rotational moment of inertia for all wheels .

In addition, the TDC applied to the FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators, as described in Equation (13), employs a control sampling time of 1 ms. The of was selected as shown in Figure 2a, and was set to 0. The of was chosen as −0.5 g (=−4.905 m/s2, g = 9.81 m/s2) and was also set to 0. was selected, and in Equation (14) was determined by applying the aforementioned vehicle dynamics parameters, , and the selected values of , assuming a fault-free condition for the brake actuator; i.e., and .

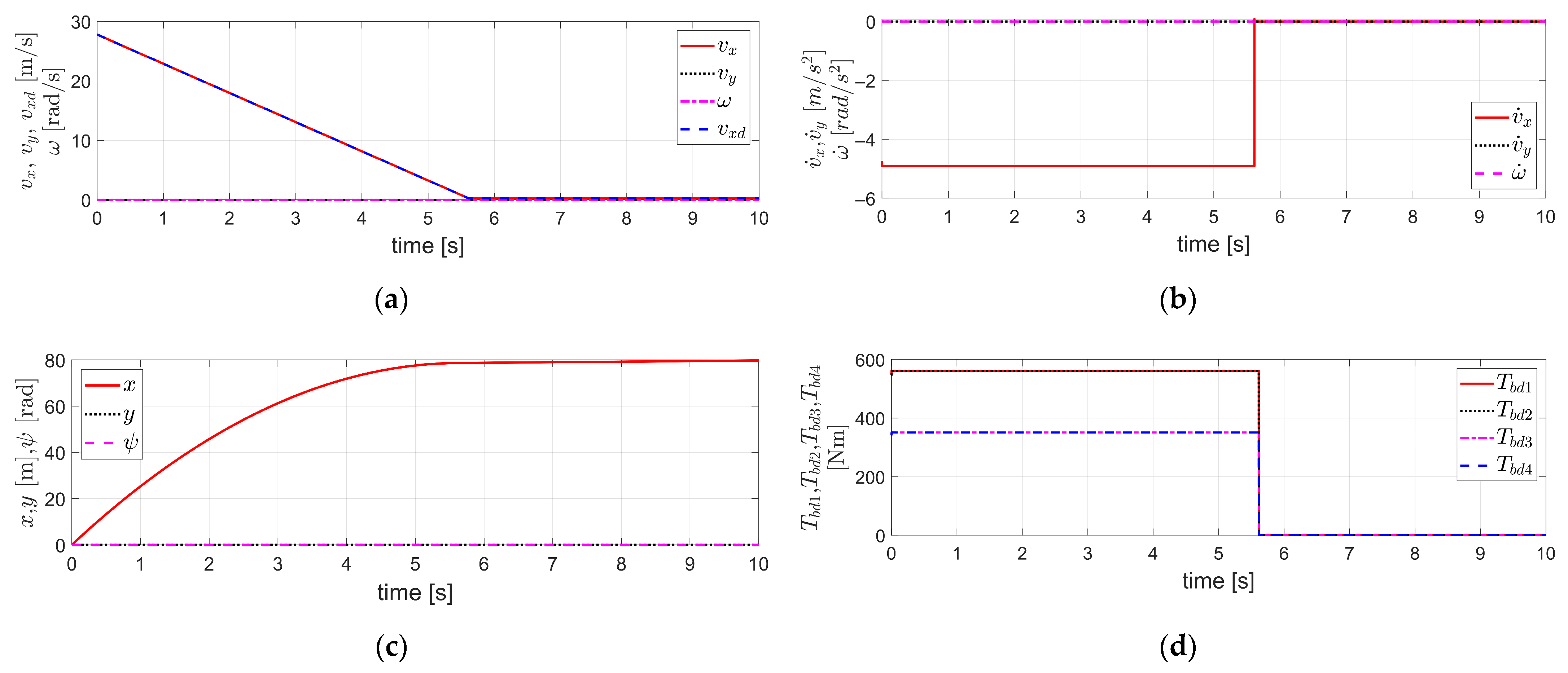

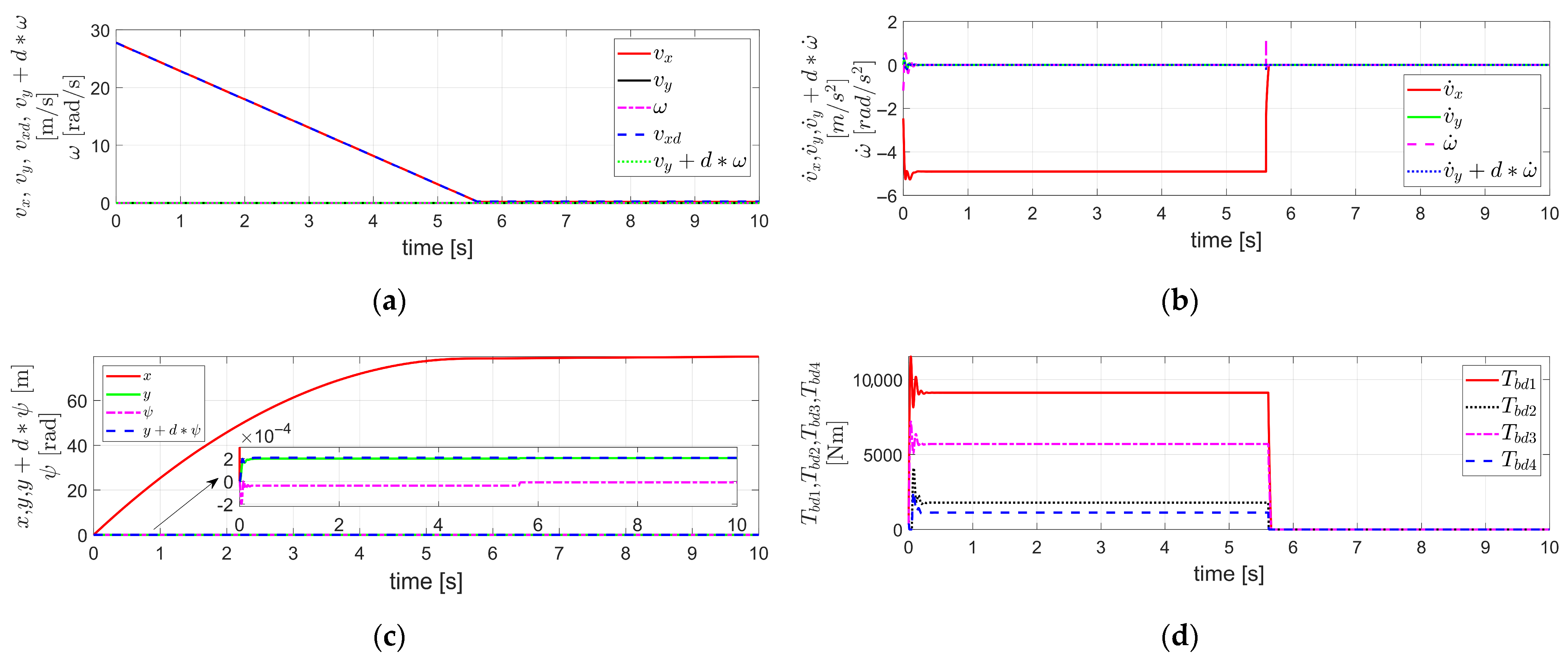

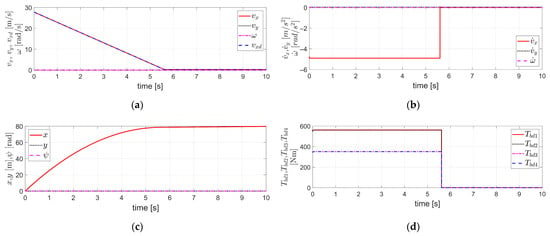

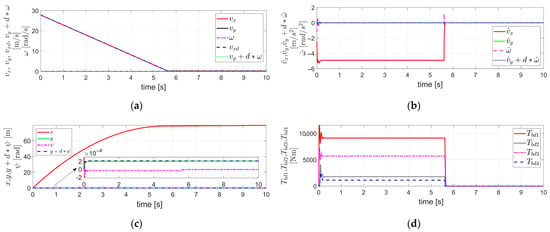

Figure 2.

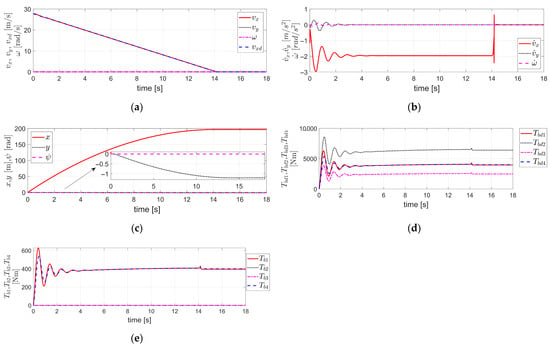

Simulation results obtained by applying the Fault Tolerant Robust Control (FTRC) of four-wheel independent Electro-Mechanical Brake (EMB) actuators using the Time Delay Control (TDC) described in Section 3.1 to the vehicle dynamics in Section 2, under the condition of no EMB actuator fault (i.e., and ): (a) The velocity components ; (b) The acceleration components ; (c) The displacement components , the longitudinal displacement, the lateral displacement, and the yaw angle, respectively; (d) ; (e) ; (f) The value of .

By applying the control as described above, a simulation was conducted under the condition that the initial vehicle velocity is 100 km/h (=27.78 m/s), and no actuator fault occurs; that is, and . The corresponding simulation results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2a shows the velocity components . Here, is set to decrease from the initial value of 27.78 m/s to a final value of 0.25 m/s. The final velocity is not set to 0 m/s in order to avoid division by , as appears in the denominator in the model described in Section 2. As shown in Figure 2a, closely follows , and tracks well. Furthermore, remains stable and maintains a value close to zero, consistent with the internal dynamics stabilizability analysis for described in Equation (16). Figure 2b shows the acceleration components . It can be observed that closely follows and also tracks well. In addition, remains nearly zero. Figure 2c illustrates , the longitudinal displacement, the lateral displacement, and the yaw angle, respectively. Here, represents the braking distance, and it can be observed that both and remain close to zero. It can be seen that the in Figure 2d is identical to in Figure 2e. This corresponds to the case without any brake actuator faults, as mentioned earlier, where and . Figure 2f shows the value of Equation (15), which remains at zero in this case. This indicates that the value of Equation (15) becomes zero due to the of in Equation (14) applied to the of in Equation (12). Thus, by applying the TDC of Equation (13) to the external dynamics described in Equation (12), the resulting control system for the external dynamics is stable. Furthermore, the internal dynamics with respect to was shown to be stable based on the internal dynamics stabilizability analysis for described in Equation (16), which is also confirmed by the simulation results presented in Figure 2. Therefore, it can be confirmed that the overall vehicle system, including both internal and external dynamics, is stable, which is also validated by the simulation results shown in Figure 2.

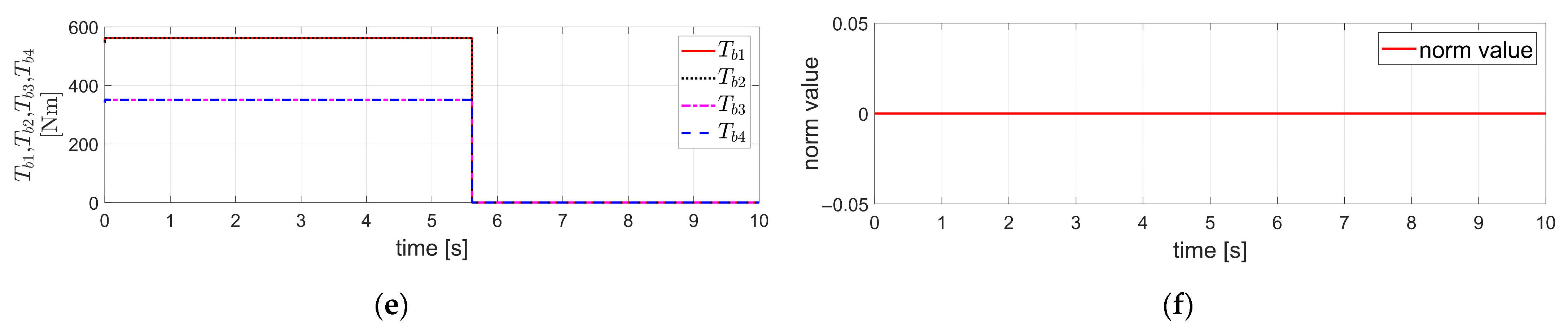

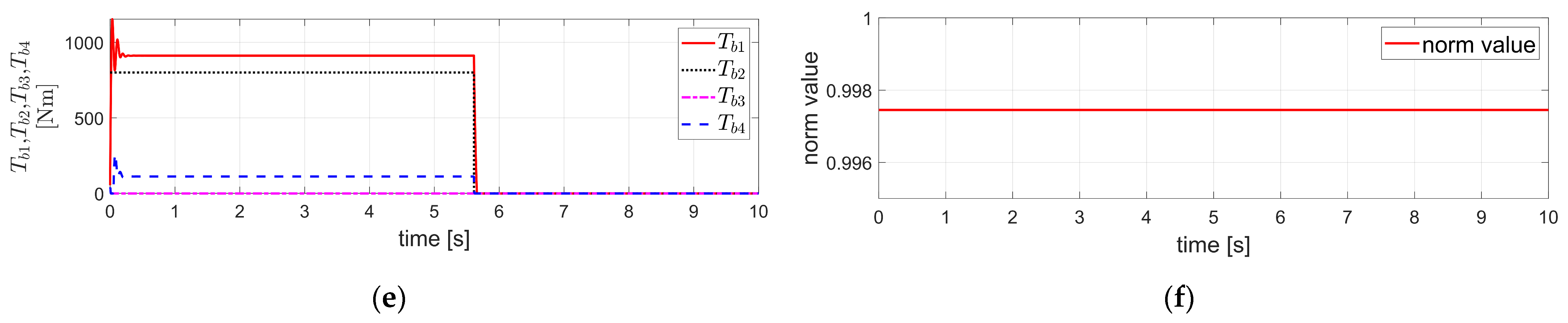

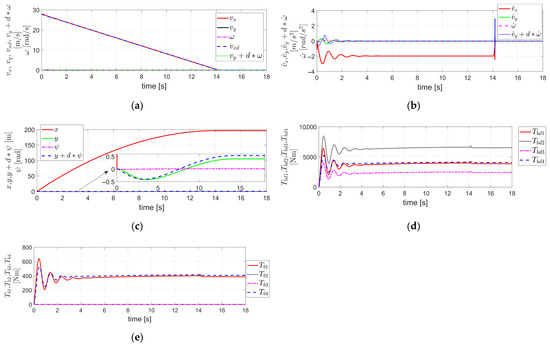

Figure 3 presents the simulation results obtained by applying the same vehicle dynamics and parameters used in the simulation of Figure 2, with the parameters, control gains, and desired values of the TDC in Equation (13) including the in Equation (14) selected identically to those in Figure 2.

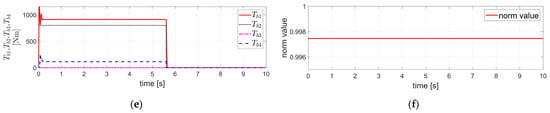

Figure 3.

Simulation results obtained by applying FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators using TDC described in Section 3.1 to the vehicle dynamics in Section 2, under the condition of severe EMB actuator faults (i.e., ): (a) The velocity components ; (b) The acceleration components ; (c) The displacement components ; (d) ; (e) ; (f) The value of .

Figure 3 shows the simulation results for the case where the initial vehicle velocity is 100 km/h (=27.78 m/s), and the is −0.5 g, as in the case of Figure 2. However, in this case, a severe fault is assumed in the brake actuators, with .

Even in the case of a severe fault as described above, Figure 3a shows that closely tracks the , and closely follows . In addition, remains stable and maintains a value close to zero, consistent with the internal dynamics stabilizability analysis for described in Equation (16). In other words, the results are similar to those of the fault-free case shown in Figure 2a. The acceleration components in Figure 3b exhibit slight overshoot tendencies at the beginning and end of deceleration. However, successfully tracks , and follows well. Similarly, shows slight overshoot behavior at the beginning and end of deceleration, but otherwise maintains a value close to zero. In Figure 3c, the lateral displacement reaches a maximum of approximately 4.5 × 10−3 m, and the yaw angle reaches a negative peak of about 1 × 10−3 rad. This indicates that, despite the presence of a severe fault, the variations in displacement compared to the fault-free case shown in Figure 2c are minimal, and the system exhibits a stable response. Figure 3d,e show and , respectively. As observed in the figures, a certain amount of overshoot occurs initially. The relationship between these two values is determined by , which represents the severity of the brake actuator fault, as mentioned earlier. Figure 3f shows the value of Equation (15), which is close to 1 in this case. However, since Equation (15) is still satisfied, the TDC described in Equation (13), when applied to the external dynamics of Equation (12), ensures the stability of the control system for the external dynamics. This stability is also verified by the response of in Figure 3. Furthermore, the internal dynamics with respect to was shown to be stable based on the internal dynamics stabilizability analysis for described in Equation (16), which is also confirmed by the simulation results presented in Figure 3. Therefore, in this case as well, it can be confirmed that the overall vehicle system, including both the internal and external vehicle dynamics, remains stable, which is also verified by the simulation results shown in Figure 3.

The simulation results in Figure 3 correspond to the case where the brake actuator fault is severe; i.e., . Nevertheless, the TDC of Equation (13) was applied without modification, using the control gain of in Equation (14), which had been selected under the fault-free condition assumed in Figure 2; i.e., and . In other words, the control gain , which was originally designed under the assumption of a fault-free condition, was applied without incorporating any fault-related information such as that obtained through FDD. Nevertheless, as can be observed from the simulation results in Figure 3, the overall vehicle system, including both internal and external dynamics, was confirmed to remain stable. This confirms the robustness of the TDC applied to FTC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators, even under severe actuator faults.

Furthermore, the simulation results in Figure 3 show that, even in the case of a severe fault in the brake actuators with asymmetric fault levels between the left and right sides of the vehicle, the proposed FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators using TDC, without employing any steering control, was able to ensure both lateral and yaw stability. In addition, the lateral and yaw displacements remained bounded within limited magnitudes, thereby ensuring safety.

In Figure 3c, it was observed that the lateral displacement reached a maximum of 4.5 × 10−3 m. In this case, the lateral displacement is extremely small and certainly not large enough to raise concerns about lane departure. However, in order to investigate whether the lateral displacement can be further reduced, we aim to apply the method proposed in Section 3.2, which uses TDC with relative weighting to the lateral velocity and yaw rate. This provides an effective approach to prevent lane departure by applying such a method in situations where lane departure is of concern.

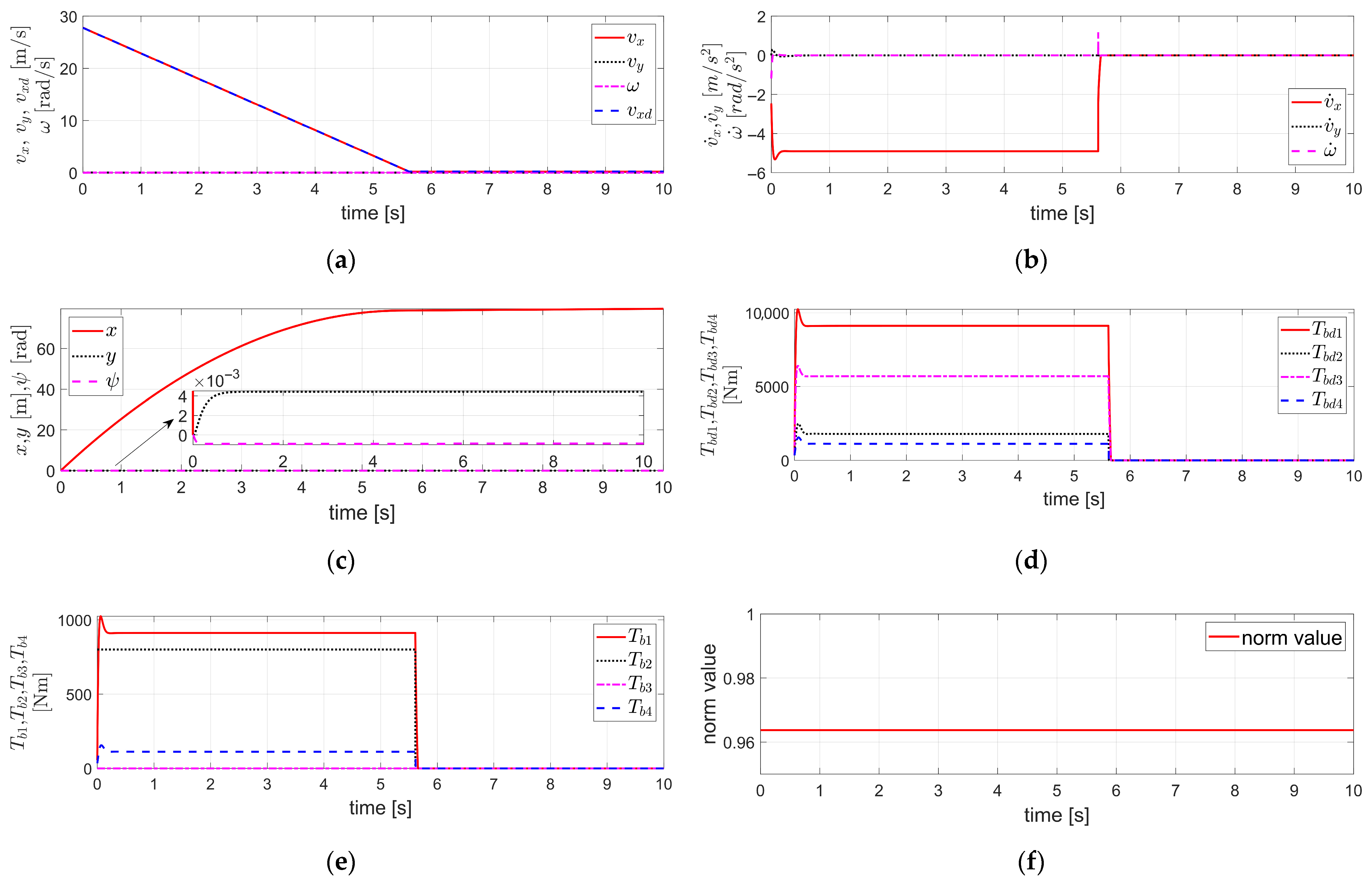

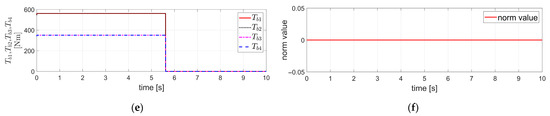

Figure 4 illustrates the case in which the control target has the same vehicle dynamics and parameter values as in Figure 3, including the same initial velocity, desired deceleration, and degree of fault in the brake actuators.

Figure 4.

Simulation results obtained by applying FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators using TDC with relative weighting to the lateral velocity and yaw rate described in Section 3.2 to the vehicle dynamics in Section 2, under the condition of severe EMB actuator faults (i.e., ) and the relative weighting : (a) The velocity components ; (b) The acceleration components ; (c) The displacement components ; (d) ; (e) ; (f) The value of .

In Figure 4, the time delay applied in the TDC presented in Equation (20) of Section 3.2—i.e., the control sampling time—is 1 ms. The of is shown in Figure 4a, and both and are zeros. The of is set to −0.5 g, and both and are zeros. Furthermore, , and the vehicle dynamics parameters, , and of were applied as in Figure 2 and Figure 3. In addition, the relative weighting applied to the lateral velocity and yaw rate was selected to satisfy the internal dynamics stability condition for the lateral velocity —i.e., either Equation (25) or (26)—and was tuned to minimize the lateral displacement . This always satisfies the condition in Equation (26). In other words, when reaches its minimum value of zero, the condition is satisfied.

As a result, the simulation results in Figure 4 show that the maximum lateral displacement, which was 4.5 × 10−3 m in Figure 3c, is significantly reduced to 2.1 × 10−4 m in Figure 4c, demonstrating a reduction by more than 20 times. This confirms that the application of the method described in Section 3.2, which uses TDC with relative weighting to the lateral velocity and yaw rate, effectively reduces the lateral displacement. Likewise, as mentioned earlier, this method can be utilized as an effective approach to prevent lane departure in situations where such a risk is of concern.

As shown in Figure 4a, successfully tracks , and the internal dynamics of remains stable as the relative weighting was selected to satisfy the stability condition of Equation (26). Furthermore, by controlling to follow the desired value , it is confirmed that also maintains stable value. Except for an overshoot at the initial stage of deceleration, it is confirmed that both and remain close to zero. In Figure 4b, a significant overshoot is observed at the initial stage of deceleration, however, excluding the overshoot region, closely follows the desired value . Additionally, it is confirmed that both and remain nearly zero throughout the rest of the response. Figure 4d,e show and , respectively. As observed in the figures, a significant overshoot occurs during the initial stage of deceleration. The relationship between these two values is determined by the degree of brake actuator fault, , as previously mentioned. Figure 4f shows the value of Equation (22), which is approximately close to 1 in this case. However, since Equation (22) is satisfied, the TDC in Equation (20), when applied to the external dynamics described in Equation (18), ensures the stability of the control system for the external dynamics. In addition, as mentioned earlier, the parameter was selected to satisfy the stability condition of the internal dynamics for the lateral velocity , as expressed in Equation (26). Therefore, even in this case, it can be confirmed that the overall vehicle system, including both the internal and external dynamics, is stable, as also verified from the simulation results in Figure 4.

As in the simulation of Figure 3, the simulation results in Figure 4 also correspond to the case where the degree of the brake actuator fault is significant—i.e., —and the control gain , which had been selected under the fault-free condition assumed in Figure 2, is directly applied to Equation (21) without any modification. In other words, the control gain used in the TDC of Equation (20) is not the one selected based on fault information obtained through FDD, but rather the gain , which was originally designed under the assumption of a fault-free condition, without applying FDD. Nevertheless, as can be observed from the simulation results in Figure 4, the overall vehicle system, including both internal and external dynamics, was confirmed to remain stable. This indicates that the TDC in Equation (20) exhibits the robust control characteristics against faults. However, the control gain matrix of the TDC in Equation (20) must be designed not only for , but also with careful selection of the relative weighting . As mentioned earlier, the relative weighting was selected to satisfy the stability condition of the internal dynamics for the lateral velocity given in Equation (26), and was tuned such that the lateral displacement is minimized. In this case, the tuning process for selecting the relative weighting was conducted under the simulation conditions of Figure 4 and the severity of the brake actuator fault. Therefore, in this case, it is necessary to identify the severity of the brake actuator fault through FDD. Although this approach requires the burden of identifying the severity of the brake actuator fault via FDD, it enables a reduction in lateral displacement and ultimately provides the capability to prevent lane departure.

Furthermore, the simulation results in Figure 4 confirm that, even in the case of a severe fault in the brake actuators with asymmetric fault levels between the left and right sides of the vehicle, lateral and yaw stability can be achieved solely through the FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators using the TDC in Equation (20), without applying any steering control. In addition, it is verified that the lateral displacement is significantly reduced compared to the results shown in Figure 3.

4.2. Simulation of the FTRC of Four-Wheel Independent EMB Actuators Using TDC Proposed in Section 3 Applied to 14 DOF Vehicle Dynamics Using Vehicle Dynamics Blockset in MATLAB/Simulink

In this section, the control target is 14 DOF Vehicle Dynamics using Vehicle Dynamics Blockset (VDBS) [21] in MATLAB/Simulink R2024b, which is based on a real vehicle and incorporates the Magic Formula tire model.

The vehicle dynamics parameters applied are the same as those used in Section 4.1, including , , , , , , the effective radius for all wheels , and the rotational moment of inertia for all wheels .

In addition, the TDC applied to the FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators, as described in Equation (13), employs a control sampling time of 0.1 ms. The of was selected as shown in Figure 5a, and was set to 0. The of was chosen as −0.2 g and was also set to 0. was selected, and in Equation (14) was determined by applying the aforementioned vehicle dynamics parameters, , and the tuned values of , under the assumption of a fault-free condition for the brake actuator; i.e., and . Here, were selected through tuning because the 14 DOF Vehicle Dynamics model using VDBS used as the control target in this section is not well known. In other words, for the complex 14 DOF vehicle dynamics model, the control gain of in the TDC of Equation (13), defined in Equation (14), must be selected through tuning. This is because it must reflect not only the estimated value of the fault level for four-wheel independent EMB actuators, but also the estimated parameters representing the unmodeled characteristics of the 14 DOF vehicle dynamics. Therefore, tuning is required to appropriately determine .

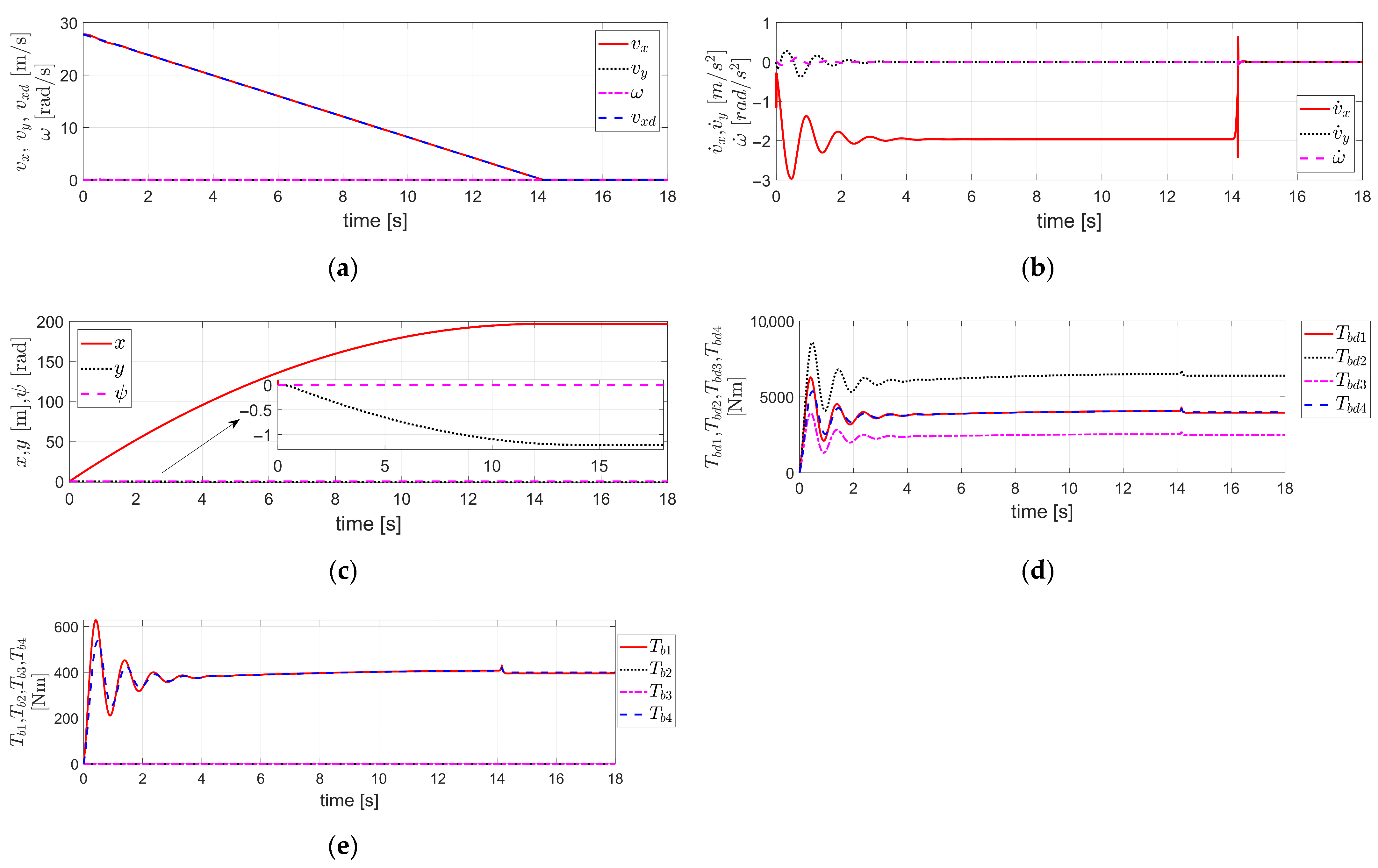

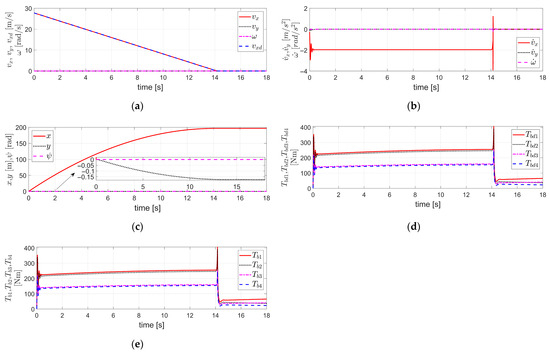

Figure 5.

Simulation results obtained by applying FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators using TDC described in Section 3.1 to the 14 DOF Vehicle Dynamics using Vehicle Dynamics Blockset (VDBS) in MATLAB/Simulink, under the condition of no EMB actuator fault (i.e., and ): (a) The velocity components ; (b) The acceleration components ; (c) The displacement components ; (d) ; (e) .

By applying the above conditions, the simulation results for the case where the initial vehicle velocity is 100 km/h (=27.78 m/s) and there is no fault in the brake actuators—i.e., and —are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5a illustrates the velocity components, . As shown in Figure 5a, closely follows , and also tracks well. Furthermore, remains stable and maintains a value close to zero. Figure 5b illustrates the acceleration components, . Although significant overshoot is observed during the initial and final phases of deceleration, closely follows , and also tracks relatively well. Additionally, remains close to zero throughout the simulation. Figure 5c illustrates the longitudinal displacement , lateral displacement , and yaw angle . The variable represents the braking distance, while remains nearly zero. The variable exhibits a stable response, being bounded within a negative maximum value of approximately 0.18 m. Figure 5d shows , and Figure 5e shows . As mentioned above, this corresponds to the case without any fault in the brake actuators; i.e., and . In this case, and have identical values. Figure 5d,e show that both and exhibit significant overshoot behavior at the beginning and end of deceleration. The reason they maintain nonzero steady-state values even after braking has completed is presumed to be due to the continued compensation control for the unmodeled uncertainties and external disturbances of the 14 DOF vehicle dynamics. Unlike Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, Figure 5 does not present the results corresponding to the stability condition of Equation (15). This is because the mathematical model equations of the Matlab/Simulink VDBS 14 DOF vehicle dynamics used as the control target in this section are not well known. Consequently, when attempting to represent the system in the form of the external dynamics described by Equation (12) or Equation (18), it is difficult to identify the specific mathematical expressions for each term in Equation (12) or Equation (18). Therefore, the matrix in Equation (12) or the matrix in Equation (18) cannot be clearly determined. Therefore, the results related to the stability conditions of Equation (15) could not be presented in Figure 5.

As mentioned earlier, the reason for selecting the control gain of in Equation (14) through tuning is also due to the fact that the VDBS 14 DOF vehicle dynamics model is not well known, as explained here. Therefore, as in Section 4.1, it is not possible to mathematically verify the stability of the internal and external dynamics in this case. Instead, the stability must be confirmed based on the control results applied to the VDBS 14 DOF vehicle dynamics.

From Figure 5, it can be observed that the variables of interest (i.e., , , and ) and the control inputs (i.e., , and ) remain stable and bounded.

The Matlab/Simulink VDBS 14 DOF vehicle dynamics model consists of 6 DOF for the vehicle body, 4 DOF for the rotational motion of each of the four wheels (one per wheel), and 4 DOF for the vertical motion of each of the four wheels (one per wheel). The 6 DOF for the vehicle body consist of 3 translational DOF (longitudinal, lateral, and vertical motions) and 3 rotational DOF (roll, pitch, and yaw motions).

In Figure 5, the variables related to the 3 DOF of the vehicle body (longitudinal and lateral translational motions and yaw rotational motion) among the 14 DOF of the vehicle were examined, along with the brake actuator control inputs, and it was confirmed that all of them are stable and remain within bounded values.

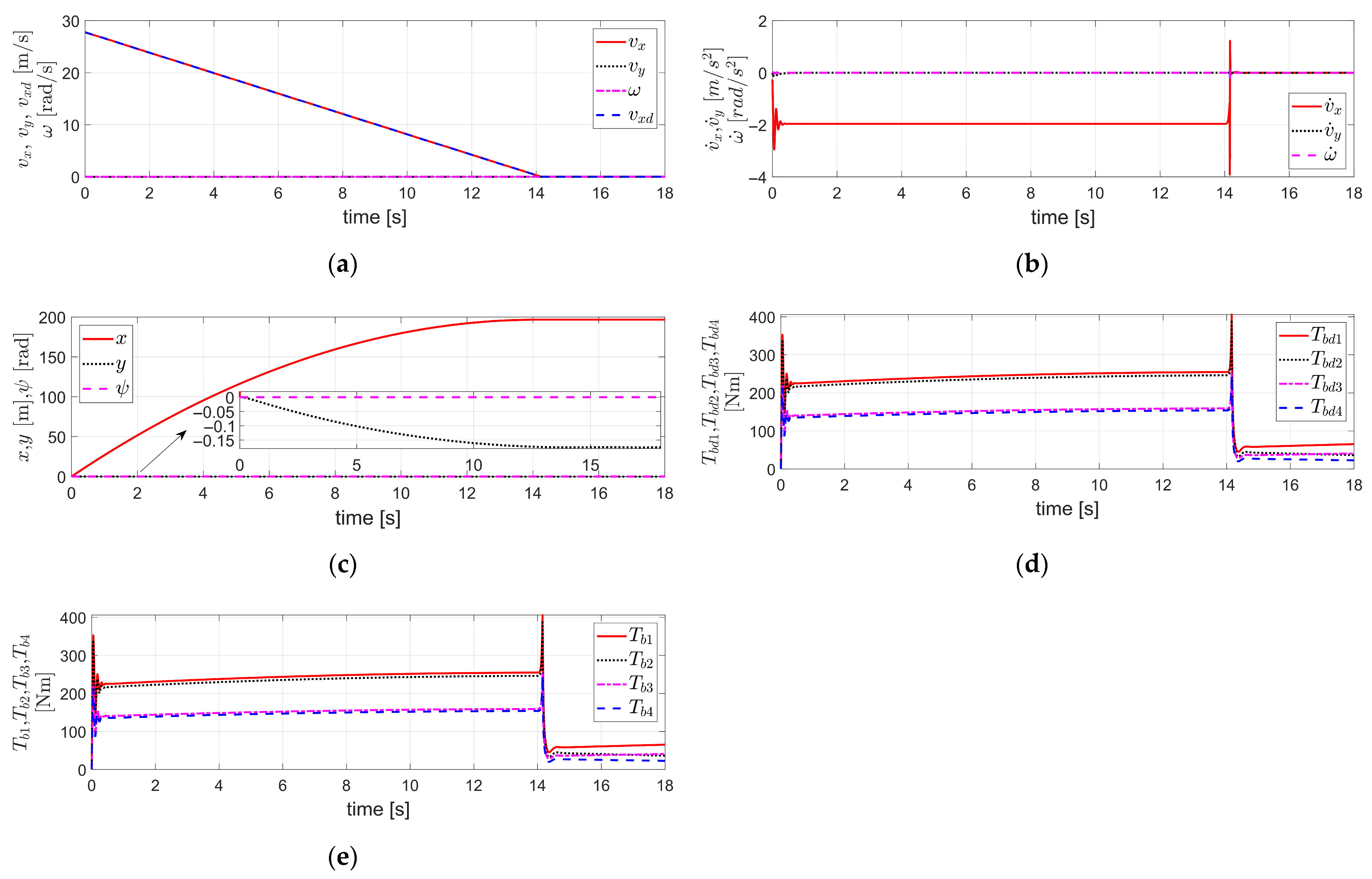

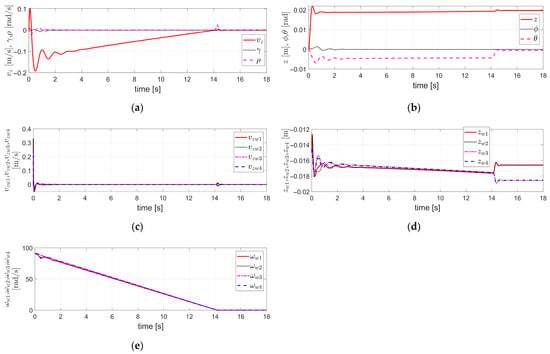

Figure 6 presents the simulation results of the remaining variables among the 14 DOF of the vehicle, excluding the vehicle body’s 3 DOF variables covered in Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Simulation results obtained under the same conditions as those in Figure 5: (a) The velocity components , the vertical translational velocity, the roll angular velocity, and the pitch angular velocity of the vehicle body, respectively; (b) The displacement components , the vertical displacement, the roll angle, and the pitch angle of the vehicle body, respectively; (c) The vertical velocities of each of the four wheels, ; (d) The vertical displacements of each of the four wheels, ; (e) The rotational angular velocities of each of the four wheels, .

Figure 6a shows the vertical translational velocity of the vehicle body, the roll angular velocity , and the pitch angular velocity , all of which exhibit stable responses. Figure 6b shows the vertical displacement of the vehicle body, the roll angle , and the pitch angle , all of which exhibit stable responses with bounded values. Figure 6c shows the vertical velocities of each of the four wheels, all of which exhibit stable responses. Figure 6d shows the vertical displacements of each of the four wheels, all of which exhibit stable responses and have bounded values. Figure 6e shows the rotational angular velocities of each of the four wheels, all of which exhibit stable responses.

Therefore, Figure 6a,b illustrate the variables associated with the vehicle body’s 3 DOF, including vertical translational motion, and rotational motions in the roll and pitch directions, showing stable and bounded responses. Figure 6c,d represent the variables related to the 1 DOF vertical translational motion of each of the four wheels, also exhibiting stable and bounded responses. Figure 6e shows the variables related to the 1 DOF rotational motion of each of the four wheels, also representing stable responses.

Therefore, Figure 6 presents the simulation results for the remaining 11 DOF, excluding the 3 DOF of the vehicle body addressed in Figure 5. These include the other 3 DOF of the vehicle body (vertical translation, roll, and pitch), a total of 4 DOF corresponding to the vertical translational motion of the four individual wheels, and a total of 4 DOF corresponding to the rotational motion of the four individual wheels. All corresponding variables exhibit stable and bounded responses.

Therefore, it can be confirmed that all the variables associated with the full 14 DOF of the vehicle, comprising the 3 DOF of the vehicle body in Figure 5 and the remaining 11 DOF in Figure 6, as well as the brake actuator control inputs in Figure 5, remain stable and within bounded values. This indicates that the overall vehicle control system is stable.

Figure 7 shows the simulation results for the case of a severe fault in the brake actuator; i.e., . The other simulation conditions are the same as those in the simulation shown in Figure 5.

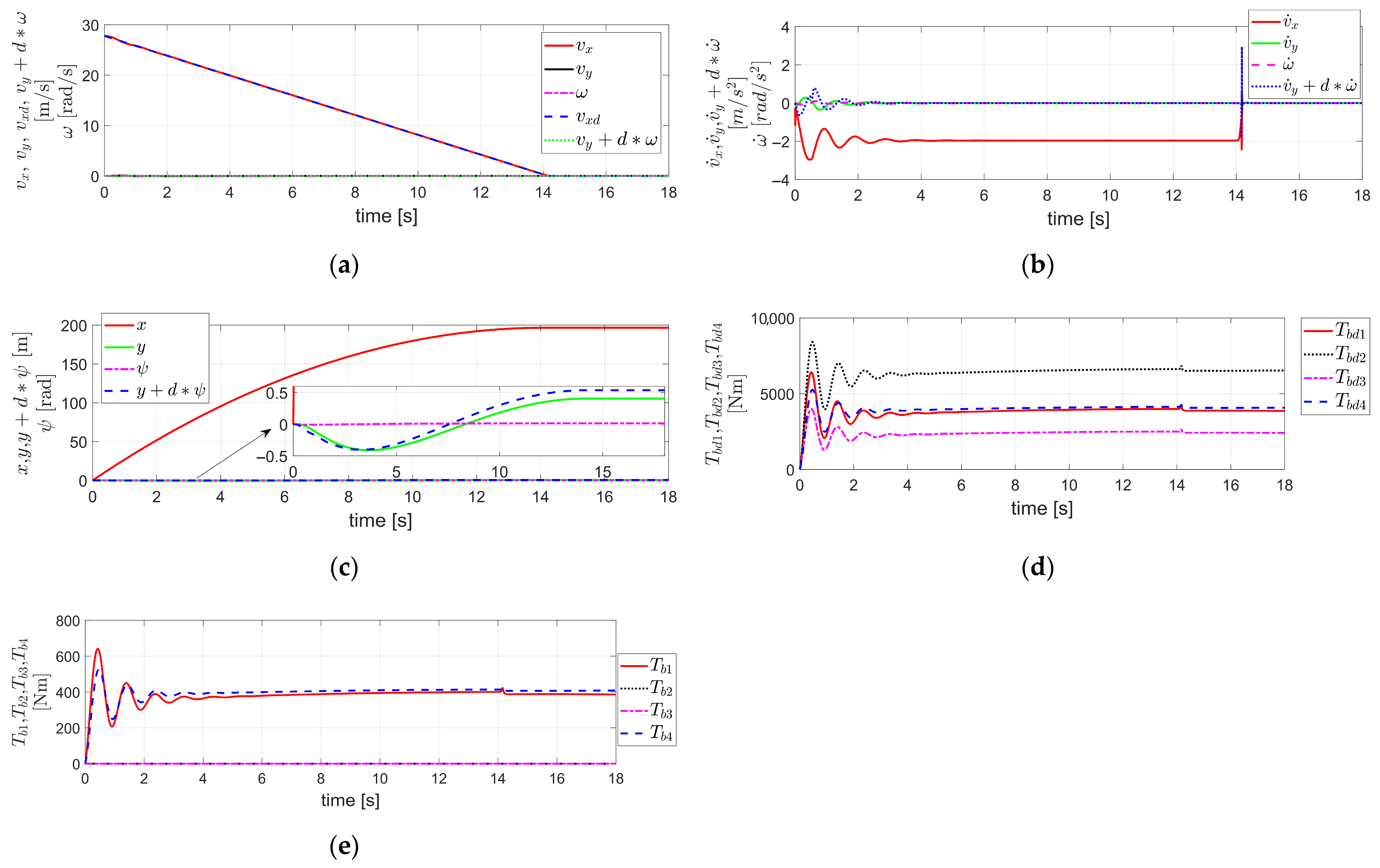

Figure 7.

Simulation results obtained by applying FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators using TDC described in Section 3.1 to the 14 DOF Vehicle Dynamics using VDBS in MATLAB/Simulink, under the condition of severe EMB actuator faults (i.e., ): (a) The velocity components ; (b) The acceleration components ; (c) The displacement components ; (d) ; (e) .

Also in this case, the control gain selected through tuning under the assumption of a fault-free condition, as in Figure 5, was applied.

As shown, even in the case of a severe fault, when the control gain selected through tuning under the assumption of a fault-free condition is applied as-is, Figure 7a demonstrates that tracks relatively well despite slight deviations during the initial deceleration phase. Similarly, also follows with minor errors in the early deceleration period. Moreover, also remains stable and maintains a value close to zero. In Figure 7b, the acceleration components exhibit oscillations in the initial deceleration phase and overshoots in the final deceleration phase. However, in other periods, closely follows , effectively tracks , and maintains a value close to zero. Figure 7c illustrates the longitudinal displacement , lateral displacement , and yaw angle , respectively. The represents the braking distance, while remains close to zero. As observed, is bounded within a maximum magnitude of 1.2 m, which indicates a stable response. However, since the magnitude is relatively large, there exists a potential risk of lane departure. Therefore, the lateral displacement should be re-adjusted and controlled to remain within a range that prevents lane departure. Figure 7d,e show and , respectively. As observed in the figures, significant oscillations occur during the initial deceleration phase, and the relationship between these two values is determined by , which represents the severity of the brake actuator fault, as mentioned earlier.

Also, as mentioned in the simulation results of Figure 5, in the simulation results of Figure 7, and retain nonzero steady-state values even after the braking phase is completed. This is presumed to be due to the continued compensation control for the unmodeled uncertainties and external disturbances of the 14 DOF vehicle dynamics.

As in Figure 5, Figure 7 also does not illustrate the results corresponding to the stability condition of Equation (15), unlike Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. The reason is the same as explained previously in relation to Figure 5.

Therefore, as in Section 4.1, it is not possible to mathematically verify the stability of the internal and external dynamics in this case either. Instead, it is necessary to confirm the stability based on the control results applied to the VDBS 14 DOF vehicle dynamics.

Similarly to Figure 5, Figure 7 examines the variables related to the 3 DOF of the vehicle body (longitudinal and lateral translational motions and yaw rotational motion) among the 14 DOF vehicle dynamics, as well as the control inputs of the brake actuators. It is confirmed that all of them maintain stable and bounded responses.

Figure 8 presents the simulation results of the remaining variables among the 14 DOF of the vehicle, excluding the vehicle body’s 3 DOF variables covered in Figure 7.

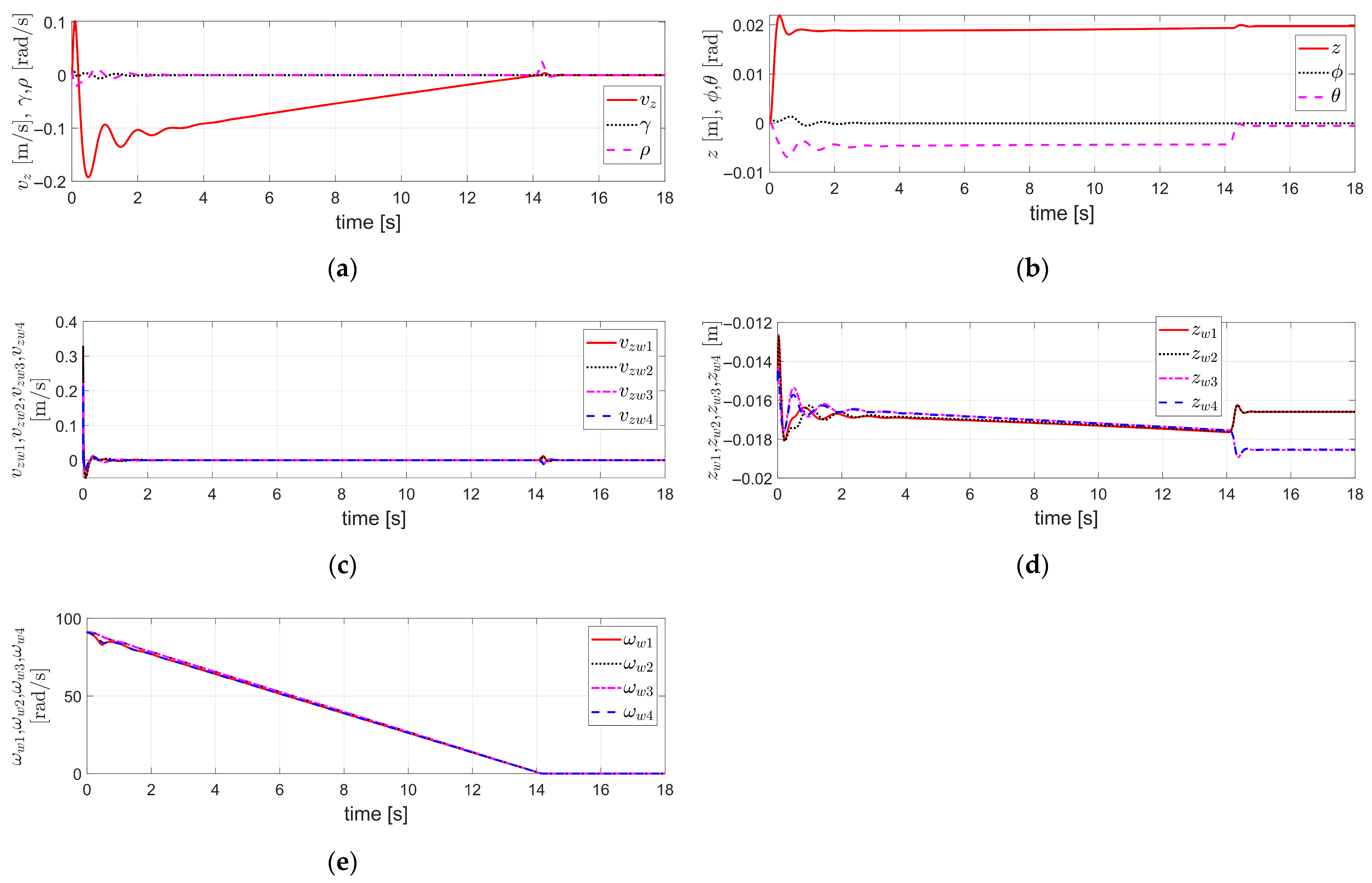

Figure 8.

Simulation results obtained under the same conditions as those in Figure 7: (a) The velocity components ; (b) The displacement components ; (c) The vertical velocities of each of the four wheels, ; (d) The vertical displacements of each of the four wheels, ; (e) The rotational angular velocities of each of the four wheels, .

Figure 8a shows the vertical translational velocity of the vehicle body, the roll angular velocity , and the pitch angular velocity , all of which exhibit stable responses. Figure 8b shows the vertical displacement of the vehicle body, the roll angle , and the pitch angle , all of which exhibit stable responses with bounded values. Figure 8c shows the vertical velocities of each of the four wheels, all of which exhibit stable responses. Figure 8d shows the vertical displacements of each of the four wheels, all of which exhibit stable responses and have bounded values. Figure 8e shows the rotational angular velocities of each of the four wheels, all of which exhibit stable responses.

Therefore, Figure 8a,b illustrate the variables associated with the vehicle body’s 3 DOF, including vertical translational motion, and rotational motions in the roll and pitch directions, showing stable and bounded responses. Figure 8c,d represent the variables related to the 1 DOF vertical translational motion of each of the four wheels, also exhibiting stable and bounded responses. Figure 8e shows the variables related to the 1 DOF rotational motion of each of the four wheels, also representing stable responses.

Therefore, Figure 8 presents the simulation results for the remaining 11 DOF, excluding the 3 DOF of the vehicle body addressed in Figure 7. These include the other 3 DOF of the vehicle body (vertical translation, roll, and pitch), a total of 4 DOF corresponding to the vertical translational motion of the four individual wheels, and a total of 4 DOF corresponding to the rotational motion of the four individual wheels. All corresponding variables exhibit stable and bounded responses.

Therefore, it can be confirmed that all the variables associated with the full 14 DOF of the vehicle, comprising the 3 DOF of the vehicle body in Figure 7 and the remaining 11 DOF in Figure 8, as well as the brake actuator control inputs in Figure 7, remain stable and within bounded values. This indicates that the overall vehicle control system is stable.

However, as previously mentioned, the lateral displacement should be re-adjusted and controlled to remain within a range that prevents lane departure.

The simulation results in Figure 7 and Figure 8 correspond to the case where the brake actuator fault is severe; i.e., . Nevertheless, the control gain , which was selected through tuning under the assumption of no fault—i.e., and , as in Figure 5 and Figure 6—is applied directly to Equation (14) without modification. In other words, this is a case where the control gain , selected through tuning under the assumption of no fault, was directly applied to the TDC of Equation (13) without incorporating any fault information obtained through FDD. Nevertheless, as can be observed from the simulation results in Figure 7 and Figure 8, the overall vehicle control system is confirmed to be stable. This confirms the robustness of the TDC applied to FTC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators, even under severe actuator faults.

Furthermore, the simulation results in Figure 7 show that, even in the case of a severe fault in the brake actuators with asymmetric fault levels between the left and right sides of the vehicle, the proposed FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators using TDC, without employing any steering control, was able to ensure both lateral and yaw stability.

In the simulation results of Figure 7, it was stated that the lateral displacement should be re-adjusted and controlled to remain within a range that prevents lane departure. Therefore, to reduce the lateral displacement , the method introduced in Section 3.2 is applied, which incorporates TDC with relative weighting to the lateral velocity and yaw rate.

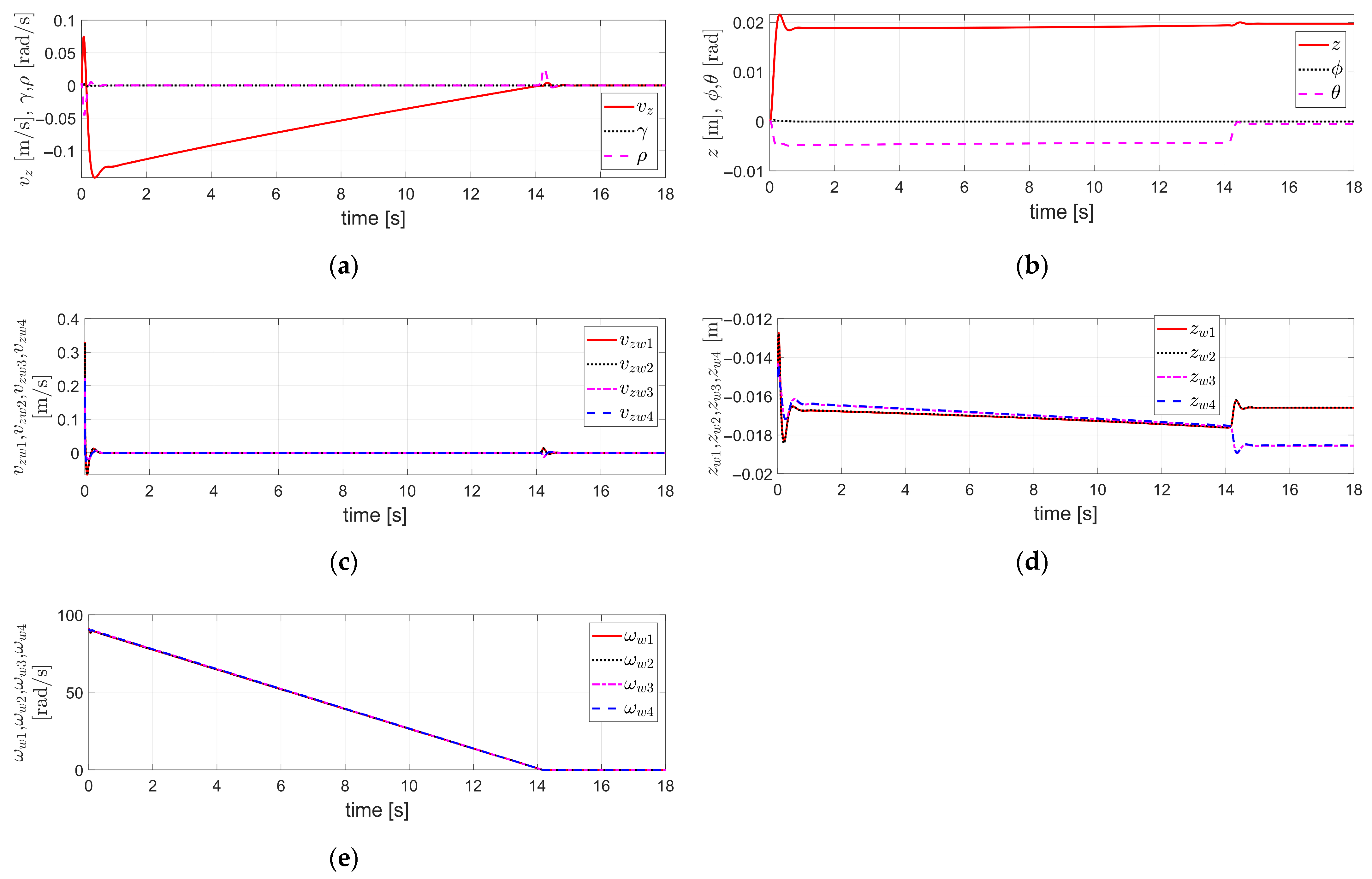

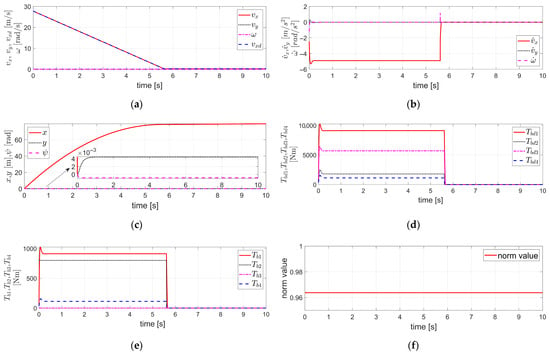

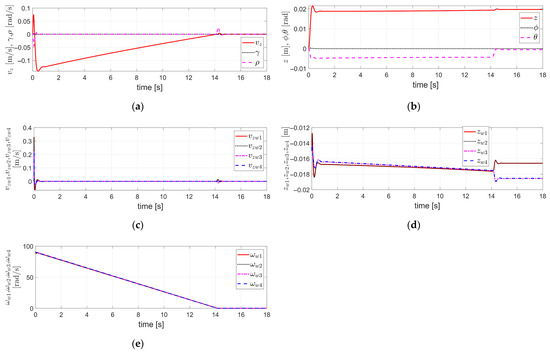

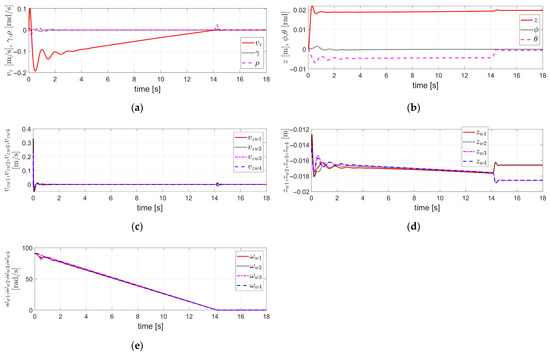

Figure 9 presents the simulation results obtained by applying the method described in Equation (20), which incorporates TDC with relative weighting to the lateral velocity and yaw rate. The simulation in Figure 9 uses the same conditions as in Figure 7, except that the control method in Equation (20) from Section 3.2 is applied instead of the method in Equation (13) from Section 3.1.

Figure 9.

Simulation results obtained by applying FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators using TDC with relative weighting to the lateral velocity and yaw rate described in Section 3.2 to the 14 DOF Vehicle Dynamics using VDBS in MATLAB/Simulink, under the condition of severe EMB actuator faults (i.e., ) and the relative weighting : (a) The velocity components ; (b) The acceleration components ; (c) The displacement components ; (d) ; (e) .

The time delay applied in the TDC presented in Equation (20)—i.e., the control sampling time—is 0.1 ms. The of is shown in Figure 9a, and both and are zeros. The of is set to −0.2 g, and both and are zeros. In addition, and the control gains of were selected through tuning under the assumption of a fault-free condition, as in Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8.

The degree of brake actuator fault considered in Figure 9 is the same as in Figure 7 and Figure 8; i.e., .

The relative weighting factor for the lateral velocity and yaw rate in Equation (20) was determined through tuning, considering the simulation conditions of Figure 9 and the severity of the brake actuator fault.

As a result, the simulation results shown in Figure 9 are similar to those in Figure 7. However, as illustrated in Figure 9c, the lateral displacement remains within , which is significantly reduced compared to that in Figure 7, and exhibits nearly symmetrical deviation in both positive and negative directions. Thus, assuming the vehicle is tracking the center of the lane, the control method described in Section 3.2, which incorporates TDC with relative weighting to the lateral velocity and yaw rate of Equation (20), can be said to contribute to preventing lane departure under the brake actuator fault condition described above.

As in Figure 5 and Figure 7, Figure 9 also does not present the results related to the stability condition of Equation (22), unlike Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. The reason is the same as explained previously in Figure 5. Therefore, as in Section 4.1, it is not possible to mathematically verify the stability of the internal and external dynamics in this case either. Instead, it is necessary to confirm the stability based on the control results applied to the VDBS 14 DOF vehicle dynamics.

Similarly to Figure 5 and Figure 7, Figure 9 examines the variables related to the 3 DOF of the vehicle body (longitudinal and lateral translational motions and yaw rotational motion) among the 14 DOF vehicle dynamics, as well as the control inputs of the brake actuators. It is confirmed that all of them maintain stable and bounded responses.

Figure 10 presents the simulation results of the remaining variables among the 14 DOF of the vehicle, excluding the vehicle body’s 3 DOF variables covered in Figure 9.

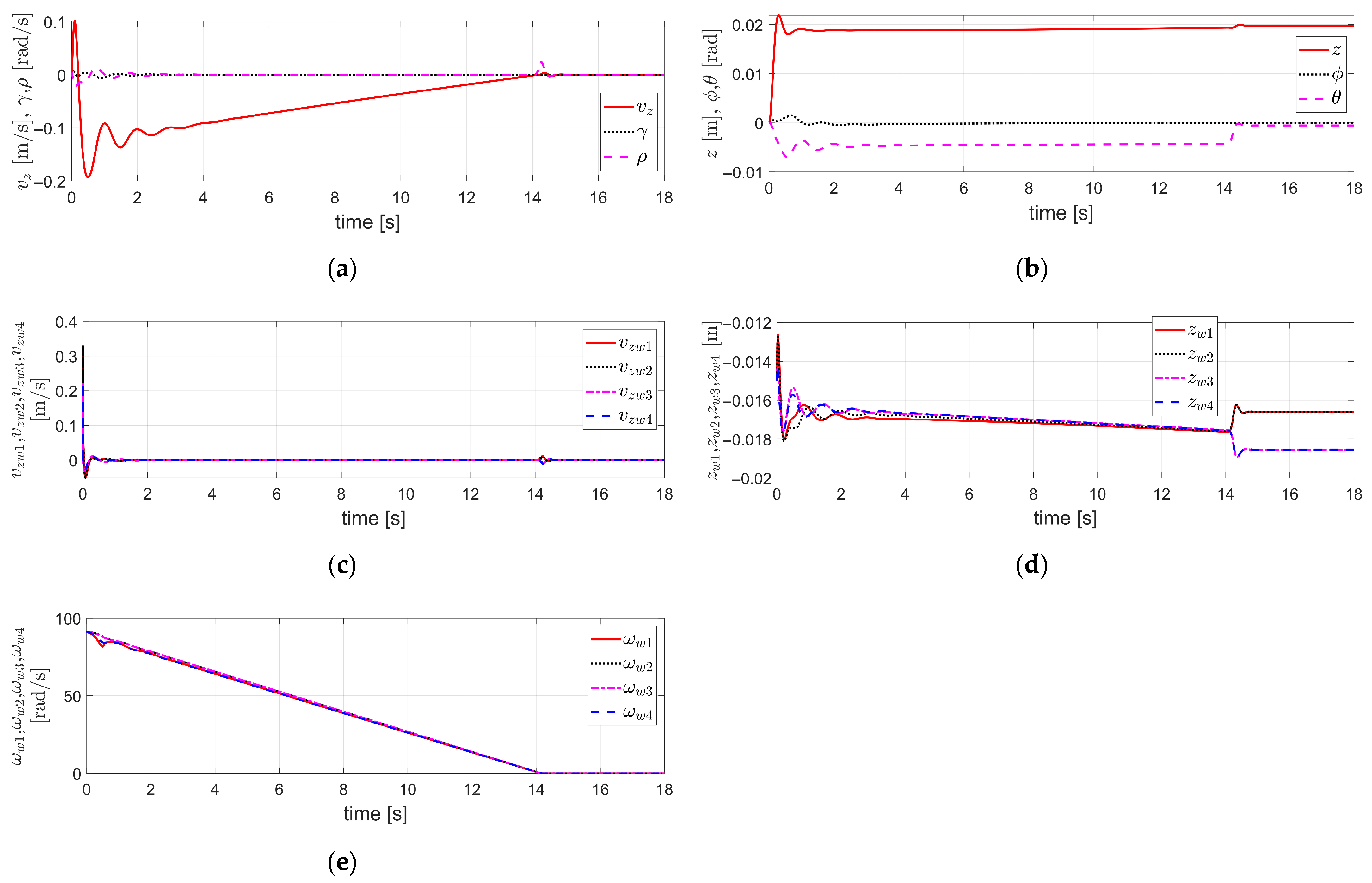

Figure 10.

Simulation results obtained under the same conditions as those in Figure 9: (a) The velocity components ; (b) The displacement components ; (c) The vertical velocities of each of the four wheels, ; (d) The vertical displacements of each of the four wheels, ; (e) The rotational angular velocities of each of the four wheels, .

Figure 10a shows the vertical translational velocity of the vehicle body, the roll angular velocity , and the pitch angular velocity , all of which exhibit stable responses. Figure 10b shows the vertical displacement of the vehicle body, the roll angle , and the pitch angle , all of which exhibit stable responses with bounded values. Figure 10c shows the vertical velocities of each of the four wheels, all of which exhibit stable responses. Figure 10d shows the vertical displacements of each of the four wheels, all of which exhibit stable responses and have bounded values. Figure 10e shows the rotational angular velocities of each of the four wheels, all of which exhibit stable responses.

Therefore, Figure 10a,b illustrate the variables associated with the vehicle body’s 3 DOF, including vertical translational motion, and rotational motions in the roll and pitch directions, showing stable and bounded responses. Figure 10c,d represent the variables related to the 1 DOF vertical translational motion of each of the four wheels, also exhibiting stable and bounded responses. Figure 10e shows the variables related to the 1 DOF rotational motion of each of the four wheels, also representing stable responses.

Therefore, Figure 10 presents the simulation results for the remaining 11 DOF, excluding the 3 DOF of the vehicle body addressed in Figure 9. These include the other 3 DOF of the vehicle body (vertical translation, roll, and pitch), a total of 4 DOF corresponding to the vertical translational motion of the four individual wheels, and a total of 4 DOF corresponding to the rotational motion of the four individual wheels. All corresponding variables exhibit stable and bounded responses.

Therefore, it can be confirmed that all the variables associated with the full 14 DOF of the vehicle, comprising the 3 DOF of the vehicle body in Figure 9 and the remaining 11 DOF in Figure 10, as well as the brake actuator control inputs in Figure 9, remain stable and within bounded values. This indicates that the overall vehicle control system is stable.

As in the simulations of Figure 7 and Figure 8, the simulation results in Figure 9 and Figure 10 also correspond to the case where the brake actuator fault is severe; i.e., . Nevertheless, the control gain , which was selected through tuning under the assumption of no fault—i.e., and , as in Figure 5 and Figure 6—is applied directly to Equation (21) without modification. In other words, the control gain used in the TDC of Equation (20) is not the one selected based on fault information obtained through FDD, but rather the gain , which was selected through tuning under the assumption of no fault, without applying FDD. Nevertheless, as can be observed from the simulation results in Figure 9 and Figure 10, the overall vehicle control system is confirmed to be stable. This indicates that the TDC in Equation (20) exhibits the robust control characteristics against faults.

However, the control gain matrix of the TDC in Equation (20) must be designed not only for , but also with careful selection of the relative weighting . As mentioned earlier, the relative weighting was determined through tuning based on the simulation conditions in Figure 9 and the severity of the brake actuator fault. Therefore, in this case, it is necessary to identify the severity of the brake actuator fault through FDD. Although this approach requires the burden of identifying the severity of the brake actuator fault via FDD, it enables a reduction in lateral displacement and ultimately provides the capability to prevent lane departure.

Furthermore, the simulation results in Figure 9 confirm that, even in the case of a severe fault in the brake actuators with asymmetric fault levels between the left and right sides of the vehicle, lateral and yaw stability can be achieved solely through the FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators using the TDC in Equation (20), without applying any steering control. In addition, it is observed that this method prevents lane departure, which was likely to occur under the conditions of the simulation in Figure 7.

Table A2 in Appendix A presents the results of the simulation in this section, summarizing the maximum absolute error values of the safety-related states—namely, the lateral displacement and yaw angle—which have errors from the desired steady-state values.

5. Conclusions

To ensure the real-time capability of control, this study aims to apply an FTC method that is robust to faults without relying on FDD, or utilizing FDD information only in the case of severe faults. Accordingly, an FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators was intended to be applied using TDC, which is capable of modeling faults as system parameter variations and external disturbances, and is robust against system parameter variations, external disturbances, and unmodeled uncertain dynamics.

In addition, to reduce the complexity of the control, this study aimed to address potential issues related to vehicle lateral and yaw dynamics stability and safety caused by EMB actuator faults, solely through an FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators without incorporating steering control. Moreover, in situations where significant lateral displacement may lead to a potential lane departure, a lane departure prevention control strategy was implemented by reducing the lateral displacement through a control approach that applies relative weighting to the lateral velocity and yaw rate.

The results obtained from this study, as shown in the simulation results in Section 4, confirm that even under severe faults in the EMB actuators, the overall vehicle system remains stable when applying the FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators using TDC, without performing FDD; that is, the robustness of the FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators using TDC against actuator faults was confirmed.

Furthermore, the simulation results demonstrated that even in cases where the faults of the EMB actuators were severe and asymmetric between the left and right sides of the vehicle, the FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators using TDC was able to maintain lateral and yaw stability without employing steering control. Moreover, in situations where large lateral displacements could potentially cause lane departure, the application of relative weighting to lateral velocity and yaw rate effectively reduced lateral displacement, thereby preventing lane departure.

From this, this study is expected to make a significant contribution to the FTC, which is essential for the electrification of vehicle brake actuators, the reduction in lateral displacement and, furthermore, the prevention of lane departure in the event of brake actuator faults.

Furthermore, the FTRC of four-wheel independent EMB actuators using TDC proposed in this study is expected to contribute to both the fault robustness and real-time capability required in practical FTC. In addition, it is anticipated to help reduce the complexity of control.

Table A3 in Appendix A summarizes the characteristics of the conventional FTC and the FTRC proposed in this study.

In this study, it was assumed that there is no limitation on the desired brake torque used as the control input. However, in practice, such a limitation inevitably exists. Therefore, future work will consider this practical constraint and investigate the potential issues that may arise, as well as possible solutions to address them.

Funding

This work was supported by the DGIST R&D Program of the Ministry of Science and ICT of Korea (25-IT-01).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

A comparison between Hydraulic Brake and EMB 1 [1,22].

Table A1.

A comparison between Hydraulic Brake and EMB 1 [1,22].

| Category | Hydraulic Brake | EMB |

|---|---|---|

| Actuator | Hydraulic actuator | Electric motor |

| Response speed | Slow | Fast |

| Control accuracy | Low | High |

| Manufacturing and maintenance | Complex | Simple |

| Energy efficiency | Low | High |

| Weight | Heavy | Light |

| Eco-friendliness | Poor | Good |

| Fault possibility | Low | High |

1 Relative comparison.

Table A2.

Maximum absolute errors of lateral displacement and yaw angle.

Table A2.

Maximum absolute errors of lateral displacement and yaw angle.

| Control Target | Fault Condition 1 | Control Method | Related Simulation | Maximum Absolute Error of Lateral Displacement 2 (m) | Maximum Absolute Error of Yaw Angle 3 (rad) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 DOF Vehicle Dynamics 4 | Equation (13) | Figure 2 | |||

| Equation (13) | Figure 3 | ||||

| Equation (20) | Figure 4 | ||||

| 14 DOF Vehicle Dynamics 5 | Equation (13) | Figure 5 | |||

| Equation (13) | Figure 7 | ||||

| Equation (20) | Figure 9 |

1 Refer to the fault model of the EMB actuator in Equation (6). 2 The desired value is 0. 3 The desired value is 0. 4 Equation (1). 5 Using Vehicle Dynamics Blockset in MATLAB/Simulink.

Table A3.

Characteristics of Conventional FTC and the FTRC proposed in this study 1.

Table A3.

Characteristics of Conventional FTC and the FTRC proposed in this study 1.

| Classification | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| R. Wang and J. Wang [9] | FDD performed, FTC applied based on FDD |

| Hui Jing et al. [10] | Fault range limitation, FTRC, applied to steering control |

| S. Kim and K. Huh [6] | FDD performed, FTC applied based on FDD, FTRC |

| Xuanhao Cao et al. [7] | FDD performed, FTC applied based on FDD, FTRC, applied to steering control |

| Guanjie Cui et al. [11] | FDD performed, FTC applied based on FDD, FTRC, applied to steering control |

| Taeho Jo et al. [12] | FDD performed (actuator’s stuck state), FTC applied based on FDD |

| Proposed Equation (13) | FDD not performed, FTRC, real-time FTC, not applied to steering control, ensures lateral and yaw stability |

| Proposed Equation (20) | FTRC, not applied to steering control, ensures lateral and yaw stability, reduces lateral displacement and prevents lane departure, FDD required for determining relative weighting factor |

1 Summary of Results.

References

- Lequesne, B. Automotive Electrification: The Nonhybrid Story. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electr. 2015, 1, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, X.; Wang, J. Motor/Generator Applications in Electrified Vehicle Chassis—A Survey. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electr. 2019, 5, 584–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, W. Unified Chassis Control of Electric Vehicles Considering Wheel Vertical Vibrations. Sensors 2021, 21, 3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Q.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.P.; Li, S.H. Brake-by-wire system for passenger cars: A review of structure, control, key technologies, and application in X-by-wire chassis. Etransportation 2023, 18, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamzam, O.; Ramzy, A.A.; Abdelaziz, M.; Elnady, T.; Abd El-Wahab, A.A. Structural performance evaluation of electric vehicle chassis under static and dynamic loads. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Huh, K. Fault-tolerant braking control with integerated EMBs and regenerative in-wheel motors. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2016, 17, 923–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Tian, Y.; Ji, X.; Qiu, B. Fault-Tolerant Controller Design for Path Following of the Autonomous Vehicle Under the Faults in Braking Actuators. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electr. 2021, 7, 2530–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.C.; Song, T.J.; Kim, M.J.; Oh, K.S. Adaptive Model Predictive Fault-Tolerant Control for Four-Wheel Independent Steering Vehicles with Sensitivity Estimation. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2023, 24, 829–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, J. Fault-Tolerant Control With Active Fault Diagnosis for Four-Wheel Independently Driven Electric Ground Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2011, 60, 4276–4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Wang, R.; Chadli, M.; Hu, C.; Yan, F.; Li, C. Fault-Tolerant Control of Four-Wheel Independently Actuated Electric Vehicles with Active Steering Systems. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2015, 48, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Bao, C.; Guo, M.; Xu, Y.; He, Y.; Wu, J. Research on Path Tracking Fault-Tolerant Control Strategy for Intelligent Commercial Vehicles Based on Brake Actuator Failure. Actuators 2024, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, T.; Park, I.; Lee, J.; Yoon, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, H. A Fault Diagnosis and Fault-Tolerant Anti-Lock Brake System Control for Actuator Stuck Failures in Braking System in Autonomous Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electr. 2025, 11, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Y. Stabilization of active fault tolerant control systems with imperfect fault detection and diagnosis. Stoch. Anal. Appl. 2003, 21, 673–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, M.; Jiang, J.; Hagino, K. A stability guaranteed active fault-tolerant control system against actuator failures. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2004, 14, 1061–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youcef-Toumi, K.; Wu, S.T. Input/Output Linearization Using Time Delay Control. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 1992, 114, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Lu, S. Fault-tolerant control for four-wheel independent actuated electric vehicle using feedback linearization and cooperative game theory. Control Eng. Pract. 2020, 101, 104510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotine, J.J.E.; Li, W. Applied Nonlinear Control; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rajamani, R. Vehicle Dynamics and Control, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Choi, S.B.; Lee, J.; Hyun, D.; Lee, J. Accurate Brake Torque Estimation With Adaptive Uncertainty Compensation Using a Brake Force Distribution Characteristic. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017, 66, 10830–10840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Tan, H.S. Steering control of high speed vehicles: Dynamic look ahead and yaw rate feedback. In Proceedings of the 37th IEEE Conference on Decision & Control, Tampa, FL, USA, 16–18 December 1998. [Google Scholar]

- The MathWorks, Inc. Vehicle Dynamics Blockset™ User’s Guide, R2024b; The MathWorks, Inc.: Natick, MA, USA, 2024.

- Schrade, S.; Nowak, X.; Verhagen, A.; Schramm, D. Short Review of EMB Systems Related to Safety Concepts. Actuators 2022, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).