1. Introduction

Tracked vehicles are extensively used in construction machinery, agricultural and forestry operations, and defense equipment due to their low ground pressure, strong obstacle-crossing capability, and excellent terrain adaptability [

1,

2,

3,

4]. On complex and unstructured terrains like soft soil, gravel roads, and obstacle surfaces, the interaction among the track, drive sprocket, and road wheels significantly impacts the vehicle’s traction efficiency, operational stability, and vibration characteristics [

5,

6,

7]. Within these subsystems, the track tensioning system is crucial for maintaining the track profile and ensuring continuous meshing. The quality of its regulation directly affects the vehicle’s dynamic response and energy performance. Insufficient tension can cause track slackening or derailment, while excessive tension increases frictional losses and energy consumption between the idler wheel and the track [

8,

9]. Thus, achieving closed-loop optimization of track tension under dynamic operating conditions is a fundamental issue in the dynamic analysis of tracked vehicles [

10,

11,

12].

Track tensioning technology has progressed from mechanical constant-tension systems to hydraulic passive systems and, most recently, to electro-hydraulic active tensioning systems [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Mechanical systems provide stable tension in static conditions but struggle with adapting to terrain irregularities and load disturbances [

17]. Hydraulic systems, which use proportional valves and accumulators, offer limited adjustments based on operating conditions; however, their accuracy, robustness, and energy efficiency are still limited [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Recently, electro-hydraulic control, integrated with advanced strategies like nonlinear model predictive control (NMPC), learning-enhanced MPC, and disturbance-observer-based control, has been applied to active tensioning. Research shows that active tensioning effectively suppresses peak tension, reduces vibration impacts, and extends track service life [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

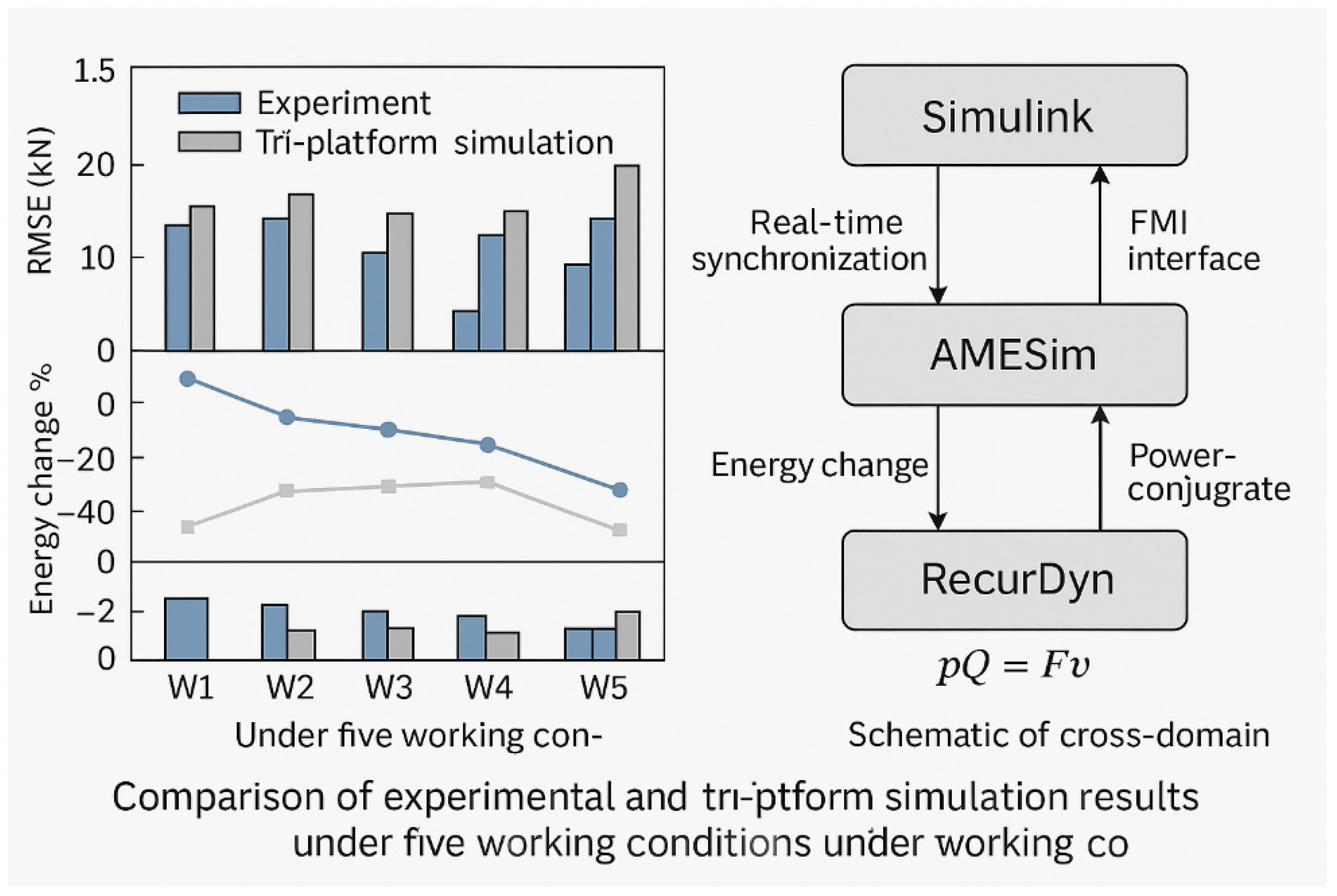

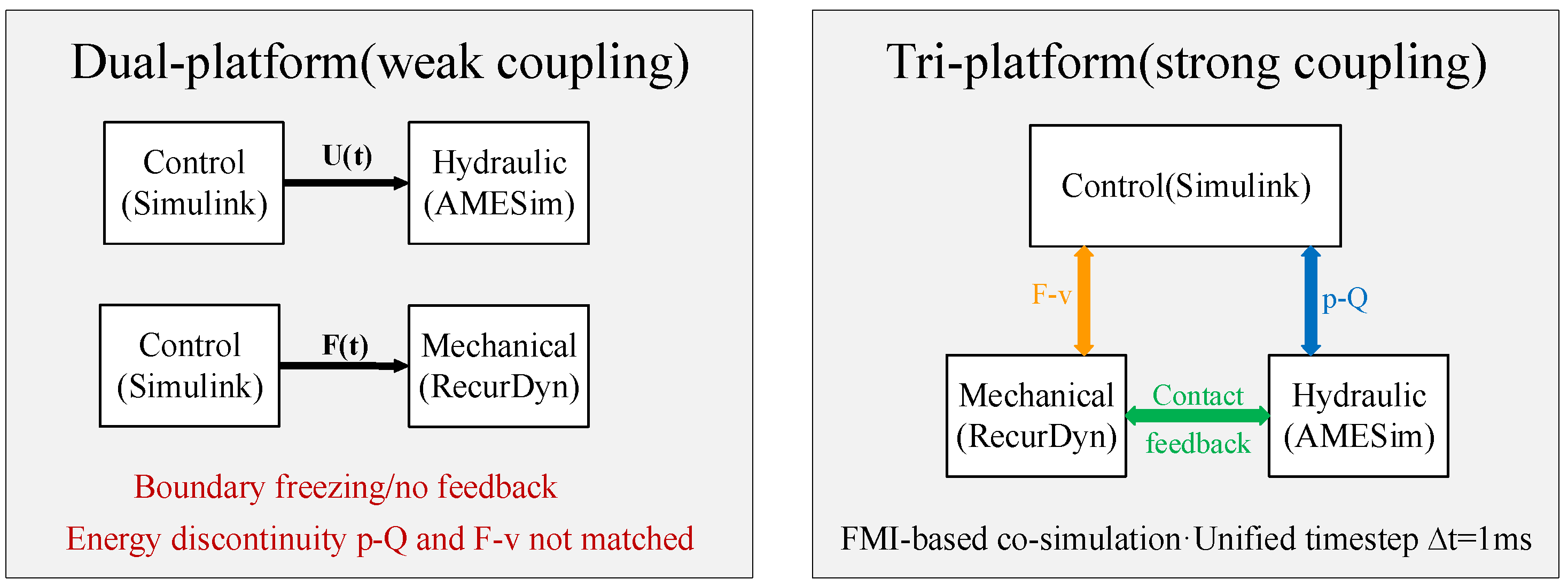

To effectively evaluate the interaction between the tensioning system and vehicle dynamics during the design phase, both academia and industry have increasingly adopted multi-domain virtual prototyping approaches. Traditional single- or dual-platform simulations, however, face challenges due to inherent cross-domain physical decoupling. For instance, AMESim excels in high-fidelity modeling of hydraulic transients, such as valve throttling, fluid compressibility, and leakage, but necessitates simplification of track–terrain dynamics [

28]. On the other hand, RecurDyn effectively captures contact interactions among track links, road wheels, and terrain, as well as vehicle vibration modes, yet typically idealizes the hydraulic actuator as a mere force source [

29]. Dual-platform configurations like Simulink–AMESim or Simulink–RecurDyn can partially integrate the “control–hydraulic” or “control–mechanical” domains. However, they still struggle to maintain bidirectional energy exchange and causal continuity across all three domains on a unified time base. As a result, the power transmission chain (p–Q–F–v) becomes fragmented, causing cross-domain phase mismatches and reducing dynamic consistency [

30,

31,

32,

33].

Recent research on the strong coupling of multi-software systems for construction machinery has garnered significant attention [

34,

35,

36]. In bulldozing operation studies, RecurDyn–EDEM–AMESim co-simulation is utilized to achieve realistic load spectra and predict fatigue life [

37]. This method focuses on bidirectional data feedback within a unified communication step, allowing for a more precise depiction of actual machine loads and energy transfer paths [

38]. Concurrently, the Functional Mock-up Interface (FMI) standard has developed a robust theoretical framework for error estimation and step-size control, offering a reproducible and quantifiable basis for executing strongly coupled multi-domain simulations [

39,

40].

This study introduces a robust tri-platform co-simulation framework that seamlessly integrates Simulink, AMESim, and RecurDyn. The framework facilitates bidirectional coupling across the control domain (valve logic and NMPC), the hydraulic domain (valve nonlinearities, chamber pressure–flow dynamics, leakage, and compliance), and the multibody domain (nonlinear track–terrain contact, idler wheel forces, and vehicle vibrations) using a unified time step. Interface variables are aligned based on power-conjugate pairs (p–Q and F–v) and exchanged through closed-loop feedback. This approach ensures energy consistency and causal consistency at the numerical level, effectively replicating realistic coupled responses under supply-pressure disturbances, random road excitations, and transient steering/braking conditions [

41,

42].

2. System Architecture and Modeling

2.1. Structure of the Electro-Hydraulic Track Tensioning System

Track tension is crucial for ensuring the meshing stability of the track–wheel system. If the tension is too low, it can result in track slackening or derailment; if too high, it causes accelerated wear and energy loss. The conventional mechanical tensioning mechanism, which uses a torsion bar with nut freezing, has a simple design but offers only a static preload, lacking adaptability to changing operating conditions. The electro-hydraulic tensioning system examined in this study (

Figure 1) includes three primary subsystems: (1) a hydraulic actuation circuit featuring a tensioning cylinder, a main solenoid directional valve, and two normally closed pilot valves (V_L and V_R); (2) a sensing and state-estimation module that continuously measures displacement, pressure, and tension signals; and (3) an embedded real-time control unit that uses a three-valve logic to manage pressurization, holding, and pressure-release modes. This architecture ensures stable track tension without requiring continuous energy input and allows for adaptive dynamic regulation through closed-loop control.

2.2. Hydraulic Actuation Principle

Figure 2 presents the equivalent schematic of the electro-hydraulic track tensioning system. The main valve manages the oil supply and discharge, while the two normally closed valves selectively connect to the left and right tensioning cylinders. The coordinated operation of these three valves results in three fundamental working modes:

Figure 2 illustrates the hydraulic circuit used in the derivation of Equations (1)–(3), including the cylinder chamber pressures, the main valve, and the two pilot valves that generate the pressurize/hold/release modes.

In pressurization mode, the main valve and normally closed valves open, permitting hydraulic oil to enter the cylinder chambers and thereby increasing the tension forces and . During holding mode, all three valves remain closed, trapping the hydraulic fluid within the chambers and maintaining stable track tension.

In the mathematical modeling, the flow through each valve orifice is described by the standard turbulent orifice equation:

where

is the discharge coefficient,

is the effective orifice area determined by the valve input

,

is the fluid density, and

,

denote the upstream and downstream pressures, respectively. In the present tensioning circuit,

and

correspond to the supply, chamber, or tank pressures indicated in

Figure 2.

where

is the effective bulk modulus,

indicates the effective chamber volume, and

is the effective piston area. The track tensioning force is calculated based on the chamber pressure and the piston area.

This model characterizes the nonlinear coupling among the valve orifice, pressure, and displacement, while also providing the state-space foundation for the control system. To ensure that the hydraulic-domain behavior is well defined, several modeling assumptions are adopted. The hydraulic oil is modeled using a constant effective bulk modulus, and temperature-dependent variations are assumed negligible over each operating period. Internal leakage is represented through a linear laminar-flow coefficient, whereas turbulent leakage is neglected. Valve spool dynamics are approximated using steady-state orifice-area maps , and electromagnetic delay is accounted for through the minimum holding-time constraint in the control layer. Pipeline compliance is incorporated into the effective chamber volume , and oil temperature is considered uniform during each simulation condition, consistent with the experimental setup.

To preserve energy consistency across hydraulic and mechanical domains, the interface explicitly maintains the power-conjugate relationships. From the constitutive relation , the sensitivity of force to pressure is . Similarly, the flow–velocity relation yields . These analytical derivatives are evaluated at each coupling step and exchanged among platforms. Maintaining this mapping ensures that chamber-pressure fluctuations are transmitted immediately to mechanical velocities and that mechanical reactions influence hydraulic flow correctly, thereby improving numerical stability and preventing boundary freezing.

2.3. Dynamics of the Actuating Cylinder and Track Tensioning System

The dynamics of the tensioning cylinder are described by

where

denotes the equivalent moving mass and

represents the external force transmitted from the track–terrain interaction and vehicle body. This equation characterizes the boundary coupling between the hydraulic domain and the multibody dynamics domain. To characterize the mechanical response of the track–idler–roller subsystem, several assumptions are introduced.

Terrain stiffness is represented using an equivalent Kelvin–Voigt foundation calibrated from sinkage–load measurements. Normal contact between rollers and track links follows a Hunt–Crossley formulation that captures elastic and velocity-dependent damping behavior. Tangential interaction employs a Coulomb–Stribeck friction model to provide a smooth transition between static and dynamic friction. Track pads are modeled as rigid bodies connected through revolute joints, and lateral deformation is neglected. The chassis is treated as a rigid body, with primary vibration modes dominated by the track–roller subsystem.

The stable interaction of the track–drive–idler–roller system depends on the tension force to preserve the geometric integrity and ensure the continuous contact of the track loop. By modeling the track chain as an equivalent Euler–Bernoulli beam, this equivalent-beam representation has been used in prior studies to approximate the transverse flexibility of tracked chains under dynamic loading [

43]. Although each link behaves as a rigid body, the combined hinge flexibility yields a bending-like response that can be captured by an equivalent

term calibrated from experimental modal identification. Here, I denotes the equivalent bending inertia of the entire chain segment rather than the geometric inertia of a single rigid link. It is obtained from modal identification and represents the aggregate hinge flexibility of all joints. The relationship between displacement and stress for a chain link under dynamic loading can be represented as:

In this context, represents the elastic modulus of the equivalent track-link material, is the equivalent bending inertia per unit width identified from modal tests, and is the mass per unit length. The variables and denote the transverse displacement and external load, respectively. Experimental results demonstrate this model accurately replicates the measured stress–strain distribution for frequencies below 5 kHz. Empirical studies reveal that the static track tension in a typical tracked vehicle is about 13 kN, with dynamic fluctuations reaching up to 50 kN. If the tension drops below a threshold F_min, track slackening or derailment may occur; on the other hand, excessive tension increases frictional losses and track wear. Thus, the tension control objective is expressed as: , where is the instantaneous track tension, and are the boundary limits defined by meshing stability and service-life optimization, respectively.

2.4. Control System Modeling and State Estimation

Taking the track tension as the control objective, the state vector is defined as:

where

are the pressures in the cylinder chamber pressures,

is the piston displacement, and

is the piston velocity. The control input

is the equivalent valve opening, and the system output is the instantaneous track tension

.

The nonlinear dynamic model of the system can be expressed in a unified form as follows:

To maintain stability and meet constraints under complex operating conditions, a Nonlinear Model Predictive Control (NMPC) strategy is employed. The essence of NMPC lies in conducting rolling optimization over a finite prediction horizon, where the optimal control sequence

is determined, and applying only the first control input at each step. The optimization problem is formulated as follows:

The objective function in (8), depends on the nonlinear dynamics

, and aims to balance tension-tracking error and control effort. Constraints ensure that the tension remains within safety limits, chamber pressures stay below their maximum thresholds, and valve openings satisfy physical restrictions. As some system states, like transient chamber pressure gradients, cannot be measured, real-time state estimation is achieved using either Extended Kalman Filtering (EKF) or Unscented Kalman Filtering (UKF).

In this context represents the signals measured from sensors, while is the filter gain. The filter’s estimated states are then input into the NMPC optimizer to enhance both model prediction accuracy and closed-loop robustness.

The optimized continuous control input is ultimately mapped to the three-valve switching states (pressurization, holding, pressure release), taking into account the valve dead zone and the minimum valve holding time to ensure smooth electromagnetic actuation. This architecture forms a comprehensive closed-loop control chain, integrating reference generation, state estimation, predictive optimization, three-valve logic, and actuation feedback.

The selection of NMPC parameters follows the characteristics of the hydraulic actuation dynamics. The weighting matrices are tuned using step-response tests to balance tracking performance and valve energy consumption, while the minimum valve holding time is set according to the measured electromagnetic delay of 18–25 ms.

The measurement model includes chamber pressures and cylinder displacement. The process noise covariance assumes moderate uncertainty in valve dynamics and external load, while the measurement noise covariance is based on sensor calibration (σp ≈ 0.15 MPa, σy ≈ 0.2 mm). These values were validated through residual analysis to ensure estimator consistency. The EKF/UKF estimator is constructed using the measurement vector . With process and measurement noise covariances , . This configuration yields stable estimation performance across all tested conditions, with root-mean-square errors typically within 3–5%.

The prediction horizon and control horizon were selected based on the dominant hydraulic time constant (≈40–60 ms) and the mechanical vibration period (≈80–120 ms). Weighting matrices were tuned through a combination of step-response analysis and sensitivity evaluation, ensuring balance between fast tension tracking and limited valve activity. Minimum valve holding time (25–30 ms) was chosen to prevent high-frequency chatter observed in preliminary trials.

2.5. Multibody Dynamics Model

The tracked vehicle is modeled as a multibody system comprising rigid track links, sprocket, idler, rollers, and a six-degree-of-freedom chassis. Approximately 100–120 degrees of freedom are included, with 74 track links connected through revolute joints. Normal contact between track links and rollers is described using a Hunt–Crossley impact model, while tangential friction follows a Coulomb–Stribeck formulation. Terrain stiffness is represented using an equivalent elastic foundation calibrated from sinkage–load measurements. This multibody representation effectively reproduces the dynamic behavior of the track–idler–roller subsystem and demonstrates good agreement with idler-force measurements on the LF1352 test vehicle. Although MSC ADAMS is widely used in multibody dynamics, RecurDyn was selected for this work for three main reasons. First, RecurDyn provides a dedicated Track-HM (heavy machinery) toolkit that includes built-in track–roller–ground contact libraries with significantly higher computational efficiency for large link-count systems. Second, the Facet–Facet contact algorithm is used to compute normal and tangential forces between track links, rollers, and terrain [

44]. Third, RecurDyn offers a native co-simulation interface with Simulink through FMI, enabling stable bidirectional coupling without requiring external middleware. These features make RecurDyn particularly suitable for modeling track–wheel–terrain interactions in real time, whereas ADAMS would require custom contact modeling and introduces noticeably higher computational cost for systems exceeding 80–100 contacting bodies.

For clarity, the main modeling assumptions adopted in this study are summarized as follows: The hydraulic fluid is treated as mildly compressible with a constant effective bulk modulus; internal leakage follows a linear pressure–difference relationship. Valve orifice flow obeys the turbulent orifice equation with no cavitation modeling. Track links and wheels are assumed rigid; terrain is assumed homogeneous with equivalent stiffness and damping identified from bench tests. Coulomb–Stribeck friction is used for tangential contact forces. Sensor noise is assumed Gaussian, and the EKF/UKF noise covariances are constant during operation. These assumptions determine the fidelity and generalizability of the proposed tri-platform model.

3. Hydraulic System Simulation and Cross-Domain Strong Coupling Verification

3.1. Tri-Platform Coupled Architecture and Principle of Dynamic Consistency

Existing dual-platform simulations typically use two configurations: Simulink–AMESim and Simulink–RecurDyn. Simulink–AMESim excels at accurately modeling hydraulic transient characteristics, such as valve flow resistance, fluid compressibility, and throttling nonlinearities. However, it often simplifies vehicle dynamics to lumped loads or equivalent masses, which hampers its ability to capture the feedback effects of track–terrain contact stiffness and body vibration on hydraulic chamber pressure. In contrast, Simulink–RecurDyn effectively reproduces the nonlinear interactions between track links, rollers, and terrain, as well as the vehicle’s vibration modes. Nonetheless, it usually idealizes hydraulic actuators as linear force sources, thus overlooking supply-pressure drop and valve control logic.

To explicitly address these limitations,

Figure 3 illustrates the complete cross-domain data pathways among the three platforms. RecurDyn outputs the cylinder-end displacement, idler reaction forces, and equivalent contact stiffness; AMESim computes the chamber pressures and flow rates based on the nonlinear valve orifice relations and fluid compressibility; Simulink receives these physical states, performs state estimation, and generates the switching logic for the main valve and the two normally closed pilot valves. The exchanged variables form the power-conjugate pairs (p, Q) and (F, v), ensuring that hydraulic and mechanical domains interact through a closed and causally consistent power chain.

The unidirectional boundary coupling overlooks the cross-derivative terms between domains, resulting in a structural deficiency in the system’s Jacobian matrix. This disruption affects the continuity of the pressure–flow–force–displacement power transmission chain. Consequently, energy-path truncation and boundary freezing occur, leading to a loss of dynamic consistency across domains. This inconsistency causes structural deviations from experimental results under step inputs, nonstationary road excitations, and supply-pressure disturbances.

This study introduces a robust tri-platform co-simulation framework that integrates Simulink, AMESim, and RecurDyn to address existing limitations. In this setup, AMESim models the hydraulic domain, explicitly considering fluid compressibility, valve nonlinearities, leakage, and line compliance. RecurDyn handles the vehicle dynamics domain, capturing track–roller–terrain contact, idler-wheel reactions, and body vibration modes. Simulink defines the control domain, executing valve logic and closed-loop regulation. The three domains are synchronized through an FMI/Co-simulation interface with a unified time step. The synchronization step is set to 1 ms to ensure that hydraulic transients, mechanical impacts, and control updates occur within the same temporal resolution. This configuration also preserves the cross-derivative terms, such as ∂F/∂p and ∂v/∂Q, within the global Jacobian structure, preventing boundary freezing and numerical stiffness escalation during rapid valve or contact switching. The cross-derivative terms ∂F/∂p and ∂v/∂Q are computed numerically within each communication step using first-order perturbation of interface variables. AMESim provides chamber pressure and flow sensitivity to valve opening, while RecurDyn provides force and velocity sensitivity to boundary displacement. These derivatives are retained in the FMI exchange to prevent Jacobian degeneration and ensure consistent Newton–type iteration across domains. Simulink sends control signals to AMESim, which returns chamber pressure, flow rate, and displacement to both Simulink and RecurDyn. RecurDyn provides feedback on idler-wheel forces and contact stiffness to the other domains. This bidirectional coupling mechanism allows hydraulic transients, control logic, and vehicle dynamics to evolve concurrently and converge cooperatively, maintaining a closed power chain and complete causal relationship. To ensure dynamic consistency, the framework matches effort–flow variable pairs at the hydraulic–mechanical interface to preserve power conservation. Interface residual iteration is applied to retain cross-derivative terms, thereby avoiding structural mismatches in the Jacobian matrix. In the control domain, minimum valve holding time and valve dead-zone constraints are introduced to align discrete valve logic with continuous hydraulic responses on a consistent time scale. Additionally, initial pre-tension, contact conditions, and fluid temperature are unified at initialization to prevent cross-domain drift and numerical divergence.

In summary, the proposed tri-platform framework integrates models at the software level while ensuring cross-domain dynamic consistency among hydraulic transients, control logic discretization, and vehicle multibody dynamics at the theoretical level. This framework offers a high-fidelity foundation for the dynamic simulation and experimental validation of electro-hydraulic tensioning systems.

To improve reproducibility, the multibody dynamics model implemented in RecurDyn is briefly summarized here. The LF1352 track subsystem consists of 1 vehicle body, 1 drive sprocket, 1 idler wheel, 6 road wheels, and 82 track links, resulting in a total of 286 degrees of freedom with kinematic joints defining revolute, translational, and ground-contact relationships. Track–roller and track–terrain interactions are modeled using the Facet–Facet contact formulation with normal force computed via a nonlinear Hertzian stiffness and damping law, and tangential force based on a modified Coulomb friction model with a Stribeck transition. Terrain stiffness and damping are identified from static and cyclic loading tests. Assumptions include rigid links, no lateral bending of track pads, and uniform terrain properties. This summarized description enables clearer understanding of the RecurDyn module used in the tri-platform framework.

As shown in

Figure 3, the main valve (“zong3”) and the two pilot valves (“dan1” and “dan2”) are mapped into

,

and

in the co-simulation framework. Their discrete switching states are aligned with the continuous hydraulic response through minimum holding-time and dead-zone constraints, ensuring physical consistency between electromagnetic actuation and fluid dynamics. In the modeling process, the hydraulic domain is built on the actual cylinder geometry and valve characteristics, taking into account fluid compressibility, pipeline compliance, and throttling behavior. This setup outputs key variables such as chamber pressure, piston displacement, and mechanical power. The vehicle domain, developed in RecurDyn, uses a Facet–Facet contact algorithm to create a multibody dynamic model of the track system. This model generates outputs like idler-wheel reaction forces, vehicle-body acceleration, and contact energy, with cylinder displacement and force serving as boundary conditions. The control domain employs a Nonlinear Model Predictive Control (NMPC) algorithm for closed-loop regulation. In this method, measured pressure and displacement signals undergo state estimation via Extended Kalman Filtering (EKF) or Unscented Kalman Filtering (UKF) before being fed into the predictive model. Within a finite prediction horizon, rolling optimization determines the first optimal control input, which is then translated into a three-valve logic: pressurization, holding, and pressure release. To prevent frequent valve switching and high-frequency hydraulic oscillations, minimum holding-time and dead-zone constraints are applied.

To maintain consistency across domains, the simulation begins with standardized preload conditions, track–roller contact parameters, and fluid temperature, thereby preventing initial-value drift between domains. The three domains are synchronized through the FMI/Co-simulation interface, employing a 1 ms main time step and a 10 ms control period, while using consistent engineering units (kN, MPa, L/min, mm) across all interfaces. This synchronized iteration ensures the structural integrity of the Jacobian matrices during computation, theoretically preventing numerical divergence and energy drift.

The Simulink–AMESim–RecurDyn tri-platform framework facilitates integrated multi-domain simulation at the tool level while ensuring cross-domain dynamic consistency at the theoretical modeling level. This approach offers a high-fidelity virtual prototype environment for electro-hydraulic tensioning systems, allowing for precise predictions of system stability, control precision, and energy efficiency under complex operating conditions. It serves as a dependable foundation for subsequent engineering design and full-scale testing.

3.2. Multi-Platform Comparison and Fairness Configuration

To quantitatively assess the necessity and benefits of the strongly coupled tri-platform co-simulation, three equivalent models were developed: Simulink–AMESim–RecurDyn (Tri-Platform, TP), Simulink–AMESim (Dual-Platform A, DP-A), and Simulink–RecurDyn (Dual-Platform B, DP-B). Each model employs the same NMPC controller, maintaining identical prediction and control horizons, weighting coefficients, and solver tolerances. Consistent interface signals and unit conversions ensure cross-domain comparability. On a standard workstation (Intel i7, 32 GB RAM), the tri-platform simulation requires approximately 1.8–2.5 ms per step, allowing near real-time performance at a 1 ms step size using FMI parallel execution. Solver profiling indicates that AMESim consumes ~55% of computation time, RecurDyn ~30%, and NMPC optimization ~15%. All models operate with a uniform communication step of 1 ms and a control period of 10 ms, ensuring temporal synchronization and iterative consistency across platforms. To ensure functional fairness, all controllers use identical weighting matrices, prediction horizons, solver tolerances, and actuator constraints. The NMPC formulation is therefore evaluated under exactly the same optimization structure across TP, DP-A, and DP-B, isolating the effect of cross-domain coupling rather than differences in control design. DP-A consistently overestimates tension because the mechanical load is represented as an equivalent static stiffness without real-time feedback. This causes the hydraulic subsystem to react to an unrealistically rigid boundary, amplifying pressure peaks and delaying relaxation compared to the fully coupled TP model.

The tests encompass five representative operating conditions: (1) constant-tension tracking, (2) random road excitation, (3) transient steering/braking pulses, (4) supply-pressure drop, and (5) parameter perturbation. Each scenario is repeated five times to obtain statistically significant averages and variances. The evaluation framework includes control accuracy, dynamic consistency, and energy efficiency. Key performance indicators comprise tension and displacement tracking errors (RMSE and ISE), pressure and stroke constraint violations, valve switching frequency, control increments, vehicle vibration RMS, frequency-domain energy spectra, total energy consumption, and optimization feasibility and computation time. To ensure fair comparisons, the DP-A model uses an equivalent external load matching the road-spectrum energy from RecurDyn, while the DP-B model adopts an equivalent actuator force source consistent with AMESim’s static stiffness and damping characteristics. Additionally, representative cases are aligned with experimental and bench-test data to validate the physical consistency and engineering applicability of the simulations. These configurations ensure that all three architectures are comparable and repeatable in terms of control strategy, boundary conditions, and execution environment, enabling a systematic investigation of the tri-platform framework’s cross-domain dynamic consistency and engineering feasibility. In addition to the NMPC-based schemes, a classical PID controller and a linear MPC (LMPC) derived from the linearized hydraulic–mechanical model are implemented as baseline benchmarks. Simulation results show that NMPC in the tri-platform model reduces tension RMSE by 30–45% relative to LMPC and by 40–55% relative to PID, demonstrating that the advantage of the tri-platform configuration stems from both strong coupling and nonlinear predictive control.

Compared with the dual-platform configurations, the tri-platform architecture uniquely preserves bidirectional coupling among hydraulic, mechanical, and control domains. This enables real-time propagation of contact stiffness and idler reactions back into the hydraulic subsystem, allowing the control layer to optimize against the true dynamic load rather than an equivalent static boundary condition.

Table 1 outlines the distinctions among single-, dual-, and tri-platform approaches in hydraulic modeling, control modeling, vehicle dynamics modeling, and coupling characteristics. To differentiate modeling fidelity and coupling completeness,

Table 1 uses both background shading and marker symbols. Cells marked with “●” denote high-fidelity modeling or complete functionality (e.g., AMESim for hydraulics or the tri-platform structure for cross-domain coupling). Cells marked with “○” indicate moderate fidelity or idealized simplifications (e.g., an idealized actuator in RecurDyn or simplified hydraulic sources in Simulink–RecurDyn), whose validity depends on operating conditions. Cells marked with “–“ highlight missing functionality, such as the absence of closed-loop control in AMESim alone or the lack of full vehicle-dynamics feedback in Simulink–AMESim. These symbols ensure that the distinctions remain visible even when the article is printed in black and white.

Single-platform approaches significantly simplify system representation, whereas dual-platform methods, like Simulink–AMESim, partially address this by enabling control–hydraulic coupling. However, they still fall short in capturing the feedback effects of full vehicle dynamics. In contrast, the proposed Simulink–AMESim–RecurDyn tri-platform framework (highlighted in green) offers high-fidelity modeling across hydraulic, control, and vehicle-dynamics domains. It realizes a bidirectional closed-loop and dynamically consistent interaction among the three subsystems, making it the most comprehensive modeling approach available in current studies.

To quantitatively verify the necessity and benefits of tri-platform strong coupling, three comparable models were developed: TP (Simulink–AMESim–RecurDyn), DP-A (Simulink–AMESim), and DP-B (Simulink–RecurDyn). Each model utilizes identical controllers, maintaining the same prediction/control horizons, weighting matrices, communication steps, and sampling frequencies, along with unified reference trajectories and initialization parameters. For a fair comparison, DP-A uses an equivalent external load to match RecurDyn’s road-spectrum energy, while DP-B employs an equivalent force source to align with AMESim’s actuator stiffness and damping. Each operating condition is simulated five times to gather statistical indicators in both time and frequency domains, as well as energy-consumption metrics for direct comparison. This setup ensures comparability, representativeness, and repeatability across the three architectures, establishing a unified baseline for subsequent performance analysis and mechanism interpretation. In all comparison plots (

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8), the TP, DP-A, and DP-B curves are distinguished by both line style and point markers to ensure clear identification when printed in grayscale.

3.2.1. Constant-Tension Tracking Condition

In this scenario, the reference tension initially jumps from a static value of 12 kN to 15 kN, and then begins a ramp increase at a rate of 0.05 kN/s starting at 15 s. This setup is designed to assess the controller’s tracking accuracy, overshoot behavior, and steady-state error when subjected to smooth input variations.

As illustrated in

Figure 4a, the tri-platform (TP) model achieves smooth tracking with a peak error under 0.8 kN and a steady-state RMSE of 0.42 kN. In contrast, the dual-platform models, DP-A and DP-B, have RMSE values of 1.15 kN and 0.92 kN, respectively, with DP-A experiencing an overshoot of about 2.1 kN during the step input.

Figure 4b shows that the average energy consumption for TP is 82.4 kJ, which is 14.0% and 10.1% lower than that of DP-A (95.8 kJ) and DP-B (91.7 kJ), respectively. This efficiency is due to the real-time feedback of reaction forces between the track and vehicle body to both the hydraulic and control domains in TP, which suppresses the oscillatory “overcompensation-correction” cycle and allows for near-optimal valve aperture adjustment. Consequently, this leads to significantly reduced throttling losses and enhanced energy efficiency.

3.2.2. Random Road Excitation Condition

To simulate vehicle operation over uneven terrain, we introduce a random load excitation that combines multi-frequency sinusoidal signals with Gaussian white noise. The reference tension is maintained at 15 kN, while random external disturbances affect the system via the track–terrain contact model. This setup is intended to assess the controller’s ability to reject disturbances and suppress vibrations under nonstationary inputs.

Figure 5a illustrates that under random road excitation, the tension fluctuation amplitude of the TP model remains within ±1.3 kN, which is significantly lower than the ±2.6 kN and ±2.1 kN observed for DP-A and DP-B, respectively. The RMSE values are 0.86 kN for TP, compared to 1.64 kN for DP-A and 1.27 kN for DP-B. Vehicle-body acceleration within the 8–12 Hz range, corresponding to the first vibration mode of the idler wheel, is significantly suppressed, with aRMS reductions ranging from 19% to 27%.

Figure 5b shows that the total energy consumption for TP is 83.1 kJ, which is notably lower than the 97.2 kJ for DP-A and 93.0 kJ for DP-B. Mechanistically, TP enhances performance by closing the feedback loop, transmitting contact stiffness and terrain-induced disturbances back into the hydraulic domain. This allows valve control to optimize against the actual dynamic load rather than an equivalent static load, thereby avoiding the boundary-freezing error common in dual-platform configurations.

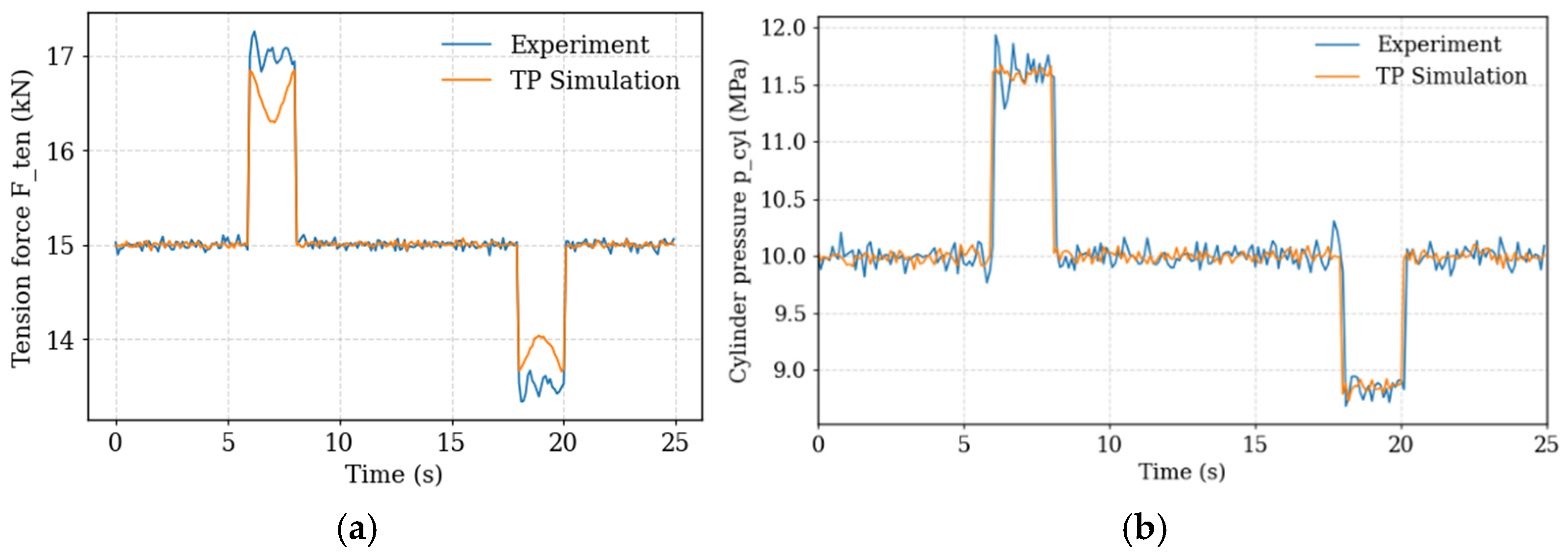

3.2.3. Transient Steering and Braking Pulse Condition

In this scenario, a +2 kN tension pulse is applied from 6 to 8 s, followed by a −1.5 kN release pulse from 18 to 20 s, simulating sudden steering and braking maneuvers. This setup evaluates the controller’s transient response, recovery time, and stability during transition phases.

Figure 6a illustrates the comparison of dynamic tension force responses between the TP model and the dual-platform models (DP-A, DP-B). The TP model shows a maximum overshoot of +1.6 kN and a settling time (Ts) of 2.4 s, while DP-A and DP-B exhibit overshoots of +3.8 kN and +2.7 kN, with Ts values of 4.1 s and 3.3 s, respectively. The TP model’s peak pressure is 0.9–1.2 MPa lower than that of the dual-platform models. Additionally, it reduces the valve-switching frequency by approximately 21% and decreases the RMS contact energy (Econtact, RMS) by about 25%. This improvement is due to the synchronous updating of control, hydraulic, and mechanical states at each time step under strong cross-domain coupling. The controller can anticipate the rising trend of idler-wheel reaction forces and contact energy at the pulse’s leading edge, allowing it to preemptively reduce valve opening to suppress pressure spikes and energy surges. In contrast, the dual-platform models, lacking awareness of transient dynamics in other domains, respond more slowly, resulting in greater overshoot.

As illustrated in

Figure 6b, the total system energy consumption for TP is 83.1 kJ, which is 14–18% lower than that of DP-A (97.2 kJ) and DP-B (93.0 kJ). The energy distribution analysis reveals that TP’s closed-loop coupling enables the valve control to adapt to the actual load, thereby avoiding the throttling losses and flow overcompensation associated with the static boundary assumptions in dual-platform models. This suggests that TP not only achieves faster convergence and smaller overshoot in the time domain but also restores physical consistency among the hydraulic, mechanical, and control domains in the energy domain.

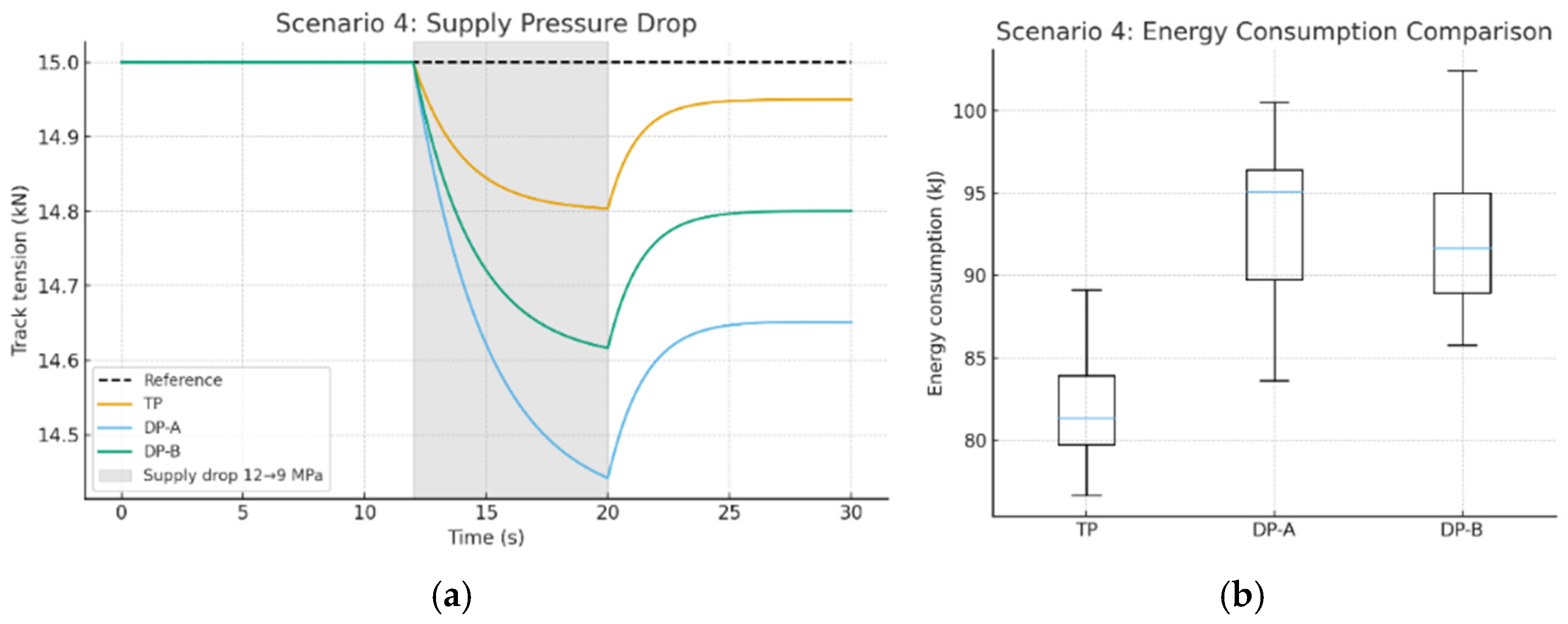

3.2.4. Supply-Pressure Drop Condition

Between 12 and 20 s, the system supply pressure decreases from 12 MPa to 9 MPa, before being restored to 12 MPa after 20 s. This scenario assesses the system’s robustness and energy performance under conditions of reduced hydraulic power, with a particular emphasis on how the pressure drop affects tension-control accuracy.

In

Figure 7a, when the supply pressure suddenly decreases from 12 MPa to 9 MPa, the TP model experiences a transient tension drop of just 0.9 kN, recovering in 1.8 s. In comparison, DP-A and DP-B show larger tension drops of 2.6 kN and 1.9 kN, with recovery times of 3.5 s and 2.7 s, respectively. The TP model’s pressure response is smoother, with significantly reduced peak fluctuations, indicating faster recovery and enhanced stability.

Figure 7b illustrates that the total energy consumption for TP is 80.3 kJ, compared to 96.1 kJ for DP-A and 92.4 kJ for DP-B, representing reductions of 16.4% and 13.1%, respectively. This efficiency is due to TP’s ability to dynamically adjust the equivalent hydraulic load using real-time feedback from vehicle dynamics. Within the NMPC framework, tension stability is achieved by combining input-increment penalties with minimum valve-holding time constraints, effectively suppressing high-frequency switching and broadband throttling under low-pressure conditions. This approach reduces energy loss, minimizes tension dips, and accelerates recovery, showcasing the framework’s robustness and energy-efficient control under supply-pressure limitations.

3.2.5. Parameter Uncertainty Condition

To evaluate the system’s robustness and adaptability under parameter variations, the effective bulk modulus, cylinder friction coefficient, and track stiffness are adjusted within ±20% of their nominal values. This approach tests the controller’s capacity to maintain stability and compensate for modeling discrepancies.

Figure 8a illustrates that with ±20% parameter variations, the TP model maintains a tension fluctuation range of ±1.1 kN and an RMSE of 0.79 kN. In contrast, DP-A and DP-B show fluctuations of ±2.8/±2.0 kN and RMSE values of 1.75/1.28 kN, respectively. Thus, the TP model achieves 45–60% smaller tension oscillations than the dual-platform approaches, highlighting its superior dynamic consistency and robustness against parameter perturbations.

Figure 8b shows that the total energy consumption for TP is 81.5 kJ, compared to 98.2 kJ for DP-A and 93.6 kJ for DP-B, reflecting reductions of 17.0% and 12.9%, respectively. This advantage stems from TP’s bidirectional coupling mechanism, which prevents cross-domain error amplification due to parameter mismatches. By synchronously updating the energy and state variables of the hydraulic and mechanical domains at each time step, the system avoids iterative error accumulation. In contrast, dual-platform models rely on unidirectional boundary assumptions, failing to perceive transient variations in other domains, which causes small parameter deviations to escalate into significant tension fluctuations and energy losses. These findings confirm the tri-platform framework’s stability and energy-consistency advantage under parameter uncertainties.

3.3. Discussion

From a system dynamic consistency standpoint, the primary advantage of the tri-platform strong coupling is not rooted in model complexity but in the closure of energy and causality chains. By synchronizing the pressure–flow pair in the hydraulic domain with the force–velocity pair in the vehicle dynamics domain using a unified time step, the tensioning cylinder—initially a unidirectional boundary variable—transforms into a bidirectional feedback variable. This transformation ensures continuity and conservation of power flow. This mechanism allows chamber pressure fluctuations to immediately reflect changes in the track–terrain contact state, enabling the control law to optimize for the actual dynamic load rather than an equivalent static load. This mechanism also mitigates throttling losses and suppresses return-flow disturbances during rapid valve transitions. As a result, the hydraulic subsystem maintains smoother chamber-pressure evolution and reduces numerical oscillations commonly observed in dual-platform configurations, while naturally minimizing throttling losses, shortening the energy path, and enhancing overall energy conversion efficiency. This dynamic consistency fosters temporal synchronization across domains, enabling simulation results to accurately reproduce both the trend and magnitude of experimental observations.

From the perspective of system identification and observability, the tri-platform framework maintains the cross-derivative terms at the hydraulic–mechanical interface, ensuring the structural integrity of the Jacobian matrix across domains. Real-time feedback of idler-wheel reaction forces and contact energy enhances the time-varying observability of the effective gain , allowing the controller to capture the coupling between contact stiffness and load phase. Consequently, the Extended or Unscented Kalman Filter (EKF/UKF) can more accurately reconstruct system dynamics within the prediction horizon, reducing the mismatch between the control law and the physical plant. This “observable hidden-variable” mechanism enables the predictive model to self-adapt to time-varying operating conditions, maintaining control precision and robustness in nonstationary scenarios such as random road excitation, abrupt steering, and supply-pressure fluctuation. Moreover, through real-time feedback of idler reaction forces and contact-energy evolution, the estimator maintains a well-conditioned observability matrix, ensuring accurate reconstruction of unmeasured chamber-pressure dynamics under nonstationary conditions.

From a control optimality standpoint, the enhanced performance of the tri-platform Nonlinear Model Predictive Control (NMPC) arises not from increased algorithmic complexity but from access to more comprehensive state and constraint information. When supply pressure is limited or contact stiffness changes abruptly, the controller can foresee constraint activation trends, such as valve opening or pressure upper limits. This foresight allows it to proactively adjust input increments and holding times within the optimization layer, thereby preventing secondary overshoot and hydraulic chatter. In contrast, dual-platform architectures experience cross-domain delays, reacting only after constraints are violated, which results in oscillatory throttling and compensatory behaviors. The tri-platform’s “prediction–feedback–constraint” closed-loop synergy shifts control from passive correction to proactive planning, fundamentally enhancing both stability and energy efficiency.

From the standpoint of frequency-domain energy shaping and resonance avoidance, the track–idler–vehicle system often displays significant modal peaks in the 8–12 Hz range. In dual-platform simulations, the absence of cross-domain phase information leads the controller to misinterpret impedance within this frequency band, preventing timely “phase-avoidance” adjustments. By incorporating acceleration and contact-energy feedback at a 1 ms synchronization interval, the tri-platform allows the controller to clearly “perceive” the phase margin within the prediction horizon. This enables the adoption of resonance-avoidance strategies, such as reducing valve gain or smoothing transitions near modal peaks. This approach accounts for the observed simultaneous reduction in PSD peak amplitude and aRMS under conditions W2 and W3, indicating that frequency-domain resonance avoidance effectively mitigates time-domain impacts.

From the standpoint of numerical stability and stiffness management, integrating hydraulic compliance, valve throttling, and track contact switching creates a highly stiff, hybrid system. The tri-platform utilizes a unified main time step and FMI synchronization, ensuring consistent time discretization and causal constraints across domains. Consequently, the discrete control output and stiff hydraulic transients are synchronized within the same sampling interval, eliminating the aliasing and phase errors often seen in dual-platform co-simulations (e.g., 0.1–1 ms vs. 5–10 ms sampling mismatch). This synchronization reduces spurious oscillations and numerical energy injection, as evidenced by the concurrent decrease in valve-switching frequency and pressure ripple in conditions W1 and W3, along with a systematic reduction in total energy consumption.

From an engineering and theoretical standpoint, the tri-platform strong coupling significantly enhances simulation fidelity while redefining the design logic of tracked-vehicle power systems. Traditional methods typically use static equivalent loads or empirical factors to determine actuator bore size, accumulator volume, and valve holding times. In contrast, the tri-platform framework offers a system-level parameter calibration method based on energy pathways, dynamic coupling, and modal coordination. Control-law weighting shifts from merely minimizing tension error to balancing power loss, peak pressure, and contact energy through multi-objective optimization. Consequently, system design transitions from local performance optimization to cross-domain, energy consistency global optimization. This approach not only boosts the predictive reliability of virtual prototyping but also provides a quantifiable and traceable theoretical foundation for the design and control-strategy development of electro-hydraulic tensioning systems. The unified discretization strategy also eliminates aliasing between hydraulic and multibody solvers, preventing spurious numerical energy injection. This explains the systematic reduction in valve-switching frequency, pressure ripple, and high-frequency oscillations across all tested working conditions.