Abstract

Reliable positioning performance is crucial in precision industrial automation, especially under dynamic conditions. This research focuses on examining the accuracy of a toothed belt driven linear servo motor positioning system, with the aim of identifying the main factors influencing position deviation. The system was built on a Power Belt ITO 060M shaft, controlled by an Rtelligent RS200-G servo controller and an Omron CP1L-E PLC. Position measurement was performed by a laser distance meter and a Cognex IS2000C-130-40-SR8 industrial camera, both calibrated with certified gauge blocks. The linear unit was moved to predefined points at different speeds, accelerations, and decelerations profiles and the resulting position deviation was recorded for each case. Several analytical methods were used to evaluate the collected measurement data to determine which factors have the greatest impact on positioning error. The result showed that speed significantly affected the accuracy of the system, while the effects of deceleration and acceleration were less pronounced. The study contributes to the fine-tuning of linear motion system and the targeted improvement of their performance.

1. Introduction

Precision positioning is of paramount importance in modern industrial automatization, especially in applications where even micrometer deviations during fast and repetitive movements can cause errors [1]. Linear motion systems, especially toothed belt-driven servo axes, are widely used in manufacturing technology and robotics because they combine high speed and long stroke lengths at reasonable cost [2,3,4]. However, positioning accuracy in these systems can be affected by a number of factors, such as speed, acceleration, mechanical flexibility and the dynamic response of the control system [5,6].

In recent years, several studies have demonstrated that the positioning accuracy of high-speed linear actuators is strongly influenced by the complex interaction of mechanical compliance, transmission elasticity, and control loop latency. Despite the extensive use of toothed belt driven systems in industrial applications, the quantitative contribution of individual motion parameters to the total positioning error remains insufficiently explored. Prior research typically evaluates overall accuracy or repeatability, but rarely isolates the independent effect of speed, acceleration, and deceleration on the dynamic behavior of the axis.

Position feedback is typically provided by incremental or absolute encoders or industrial cameras, which can provide high-accuracy position measurements when triggered externally. The latter is particularly advantageous in cases where non-contact measurement is required or where path tracking, object detection, or position verification is visual based [6,7]. Vibration dynamic effects experienced during actual motion, such as sudden acceleration, braking, or vibration, are not always accurately reflected in the position measured by the encoder system. The literature is increasingly concerned with how these motion parameters affect position error and how they can be measured and interpreted [8,9,10].

However, encoder-based measurement inherently suffers from limitation when rapid motion transients occur. Several authors have shown that encoder feedback may mask short duration deviations caused by overshoot, belt elasticity, transient oscillations, or backlash related micro slip. Vision based sensors and laser metrology therefore provide a more accurate representation of the instantaneous mechanical position, yet these are less frequently combined with systematic statistical analysis to isolate the origins of error. As highlighted in recent metrology-oriented research, the fusion of contactless measurement with computational analysis is essential for gaining a deeper understanding of dynamic error sources in smart manufacturing environments.

This study aims to investigate experimentally a toothed belt-driven linear servo system under different motion parameters, with particular focus on the effect of speed, acceleration, and deceleration on positioning error. The position measurement of the system was performed using a Cognex IS2000C-130-40-SR8 industrial camera, which was calibrated with certified gauge blocks prior to the measurement. Several analytical methods were used to evaluate the recorded date in order to identify the motion parameters that have the greatest impact on position deviation [11]. The high-resolution position information provided by the camera system was supplemented by a laser distance meter with an accuracy of 1 [mm] as an auxiliary function. The measurement system thus developed contributes to the fine-tuning of linear actuators and to increasing positioning reliability in industrial environments [12]. All equipment and measurement devices used in this project were purchased from the official authorized distributor in Serbia.

To address the above-mentioned research gap, the present work combines a non-contact vision-based measurement system with multiple analytical techniques, including Multiple Linear Regression, Principal Component Analysis, and the Random Forest machine learning algorithm. This integrated approach enables the identification of the dominant contributors to the positioning error and provides a statistically validated framework for quantifying the influence of motion parameters. The novelty of the research lies in the systematic separation of speed-, acceleration-, and deceleration-induced error component, the use of calibrated gauge block referencing for camera-based metrology, and the application of combined statistical and machine learning for tools for analyzing deviation patterns in a high-speed linear servo system.

Overall, the study aims not only to evaluate the magnitude of positioning errors but also to provide a methodological foundation for improving servo axis accuracy, supporting predictive maintenance strategies, and contributing to the development of advanced control schemes in modern automation systems.

2. Analysis of Positioning Error Development in a Linear Servo System Under Varying Motion Parameters

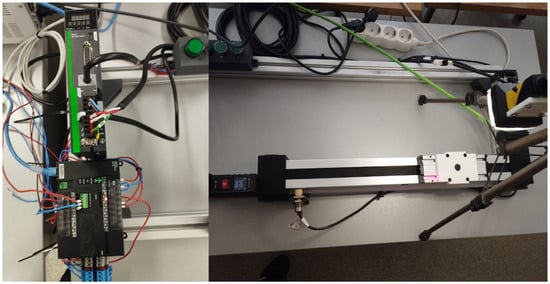

Several main factors influence the development of positioning errors in linear servo systems: mechanical, distortions, dynamic effects of the control system, and measurement uncertainties of the feedback system. For the tests, we used a servo system equipped with a toothed belt-driven linear actuator, whose position feedback was provided by the servo motor encoder. The Cognex camera was used to check the accuracy of the positioning. The structure of the system is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Configuration of the tested toothed belt-driven linear servo system with Cognex camera.

In toothed belt driven actuators, the primary mechanical contributors to positioning error arise from belt elasticity, transmission compliance, and the inertial effects of the moving mass, all of which lead to transient deviations during acceleration or rapid speed changes. Furthermore, the dynamic response of the servo controller such as loop delay, overshoot compensation, and the finite bandwidth of the position control can amplify this deviation when the high speed profile is executed [13].

Another important aspect is that encoder-based feedback only reflects the motor shaft position and does not capture the actual carriage displacement when the belt exhibits micro-stretch or transient slip, hence the need for an independent measurement system such as the calibrated Cognex camera [14,15].

To provide a clearer overview of the mechanical and metrological arrangement, a schematic diagram of the complete measurement system, the sensor placement, and the kinematic chain of the actuator is included to complement the photographic representation.

The largest positioning deviations were caused by acceleration and deceleration profiles during movement, especially at high speeds. Accordingly, the study focused on the effect of motion parameters such as speed, acceleration, and deceleration on positioning accuracy and the reliability of the values measured by the industrial camera.

High-speed motion amplifies dynamic deformation due to increased belt tension fluctuation and the limited settling time available for the control loop, while steep acceleration or deceleration ramps generate additional inertial forces that temporarily distort the belt carriage alignment.

To systematically quantify these effects, the study introduces statistical analysis methods described in Section 2.3, which make it possible to evaluate the relative influence of each motion parameter separately.

This analytical framework ensures that the measured deviations are not interpreted as a single combined error value but are instead separated into the individual dynamic components that contribute to the final positioning inaccuracy.

2.1. Control System Overview

The linear actuator was controlled by an Omron CP1L-EL programmable logic controller, which enabled the execution of predefined motion profiles and precise control of measurement cycles. The PLC communicated directly with an Rtelligent RS200-G servo control unit, which drove the servo motor and controlled the position, speed, and acceleration parameters in real time.

This control architecture ensured high repeatability and reliable execution of the motion profiles. The integration between the two devices enabled the accurate reproduction of the dynamic effects that occur during motion, which were essential for the positioning error test. These devices are shown on the left in Figure 1.

In this configuration, the PLC generated the target position commands, while the servo drive executed the corresponding motion trajectories and returned detailed feedback signals such as encoder position, velocity, and internal status information.

The Cognex industrial camera and the laser distance meter operated independently from the servo control loop, providing external, non-contact position measurement that served as reference values for the evaluation of accuracy.

This separation between command generation, closed loop control, and external measurement ensured that the observed position deviations could be attributed to the mechanical and dynamic behavior of the system rather than to measurement artifacts.

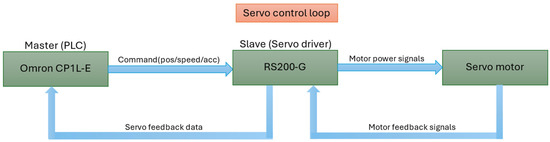

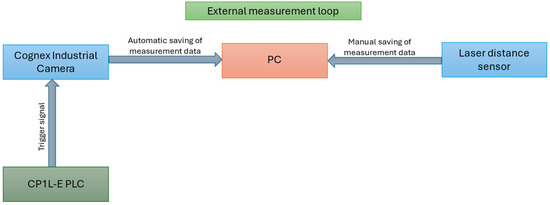

The overall system layout, including the control electronics, actuator mechanics, and metrology components, is presented in the schematic diagram to complement the photographic overview and to clearly illustrate the functional relationships between each subsystem; these can be viewed in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Servo control loop schematic diagram.

Figure 3.

External measurement loop schematic diagram.

The diagram illustrates the signal flow between the PLC, the servo drive, and the motor.

The PLC sends the motion commands, while the servo drive preforms the inner closed-loop control using encoder feedback. This structure separates high-level command generation from low-level regulation, ensuring precise and repeatable motion execution (Figure 2).

The measurement drives operate independently from the servo control system. The PLC triggers the camera, while both the camera and the laser sensor provide external, non-contact position measurements to the PC. This decoupled setup ensures that accuracy evaluation is not influenced by the internal control loop (Figure 3).

2.2. Measurement Setup

The Cognex industrial camera used for position measurement was mounted in a fixed position above the linear slide’s movement path. The camera’s field of view was located directly above the moving unit, ensuring a stable and distortion-free image of the position during measurement.

To ensure repeatability, the camera mount was rigidly fixed to an aluminum frame isolated from the actuator structure, preventing vibration coupling between the motion system and the measuring device.

The optical axis of the camera was aligned perpendicular to the linear carriage surface using alignment laser to minimize perspective distortion effects.

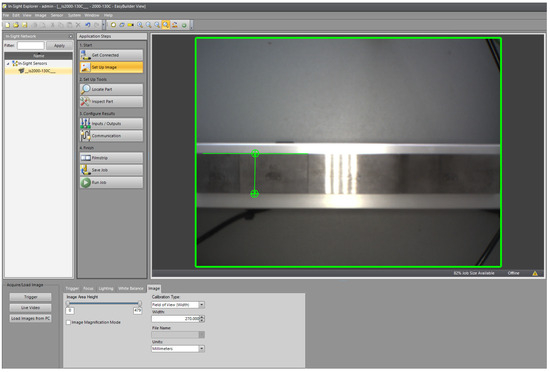

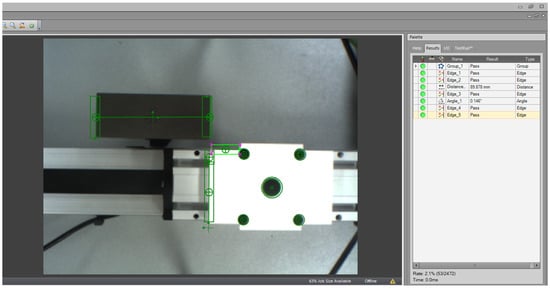

The camera was calibrated using certified gauge blocks. The purpose of this was to assign pixel-based measurements to real physical distance values and to minimize optical and geometric distortions. During the calibration process, several reference points were placed at known distances within the image to determine the pixel-distance correspondence and measure the width of the camera’s field of view using measuring gauge blocks, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Calibration of the Cognex camera using certified gauge blocks.

During calibration, gauge blocks with lengths of 10 mm, 20 mm, and 30 mm were placed at multiple lateral positions within the field of view to determine the pixel to millimeter scale factor and to detect any nonlinear distortion in the imaging plane. The maximum observed calibration deviation was below 0.2 mm across the central region of the field of view, which confirms the suitability of the camera high precision displacement measurement [16]. During the measurement program, we performed various acceleration, deceleration, and speed profiles with the linear actuator. The actuator moved to a predefined position, while after reaching the target position, the PLC triggered the industrial camera, which recorded a single high-accuracy final position measurement. During the tests, we paid particular attention to dynamic effects, i.e., how the position deviation changes under different motion parameters.

All measurements were carried out under non-load conditions, using only the mass of the 3D-printed carriage. This ensures that the observed deviations originate primarily from belt elasticity and servo dynamic rather than external loading effects.

The friction of the linear rail was measured prior to testing and found to be constant within the operating speed range, indicating negligible contribution to dynamic error.

The position data was recorded and processed by Cognex EasyBuilder software. The camera’s image processing algorithm was based on circle and edge detection, and measurements were taken automatically at each position. Sampling took place after the sled had stopped in order to eliminate vibrations and obtain a stable position. The data obtained in this way can be used to calculate position deviations that can be assigned to different acceleration, deceleration, and velocity values.

Sampling was initiated 200 ms after the servo drive signaled in the position status, a delay that ensures sufficient settling time for the mechanical system and eliminates residual oscillations.

Each measurement position was repeated 50 times in identical conditions in order to build a statistically relevant dataset for later PCA, Random Forest, and MLR analysis.

The position of the gauge block was fixed using 3D printed holder, which was specifically aligned with the reference point of the linear actuator’s end position. The holder was adjusted, and the gauging block was in exactly the same plane when the sled reached the reference position. This adjustment to the arrangement of the geometric relationship can be seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Setup of the gauge block and geometric alignment for position verification.

The gauge block remained in the field of view throughout the measurement process, thus enabling continuous verification of the system. Since the size of the gauge block is constant and known, it served as a reference standard the accuracy of the camera calibration and focus could be checked before and during each measurement.

Based on the measurement of the angle at each triggered acquisition between the gauge block and the edges of the 3D printed sled, the positioning error can be calculated in [mm] using Equation (1).

where

- : The calculated position deviation.

- : The reference length () measured in the camera’s field of view, i.e., the distance between the gauge block and the carriage (Figure 3).

- : The angle enclosed by the edges of the white 3D printed carriage and the gauge block.

This formulation is valid because any microscopic misalignment between the two vertical edges produces a measurable angular deviation , which is directly proportional to the lateral displacement error through the geometry of the imaging plane [17].

To convert pixel-based measurement into real physical distances, the Cognex industrial camera was calibrated using certified gauge blocks of known length [18]. During the calibration process, the gauge block was placed at multiple positions within the field of view allowing the software to determine the pixel to millimeter scale factor. This relationship is illustrated in Equation (2) where the scale factor is defined as the ratio between the reference physical length and its corresponding imag size in pixels

Once the scale factor is established all measured pixel values can be converted into millimeters using Equation (3)

The multi-point calibration compensates for minor optical and geometric distortions ensuring a linear and robust pixel to millimeter mapping across the calibrated region. The resulting calibration error remains below 0.2 mm, confirming the suitability of the method for high precision displacement evaluation.

Laser distance measurement was used as a complementary method in the initial phase of the tests, primarily for feedback purposes. This technique proved particularly useful for detecting initial, larger position errors, which often reached or exceeded 1 [mm] due to improper programming and calibration. Laser measurement was therefore not part of the core measurement workflow but only provided rapid OK/NOK validation during the initial fine tuning and calibration of the system.

2.3. Analytical Methods

In order to interpret and reduce positioning errors in linear servo systems, it is essential to use appropriate data processing and analysis methods. Only statistical and machine learning tools can extract correlations from the data recorded during measurements that reveal the relationship between motion parameters and positional deviations [19].

These methods enable the identification of key factors, the development of predictive models, and the fine-tuning of the system for more reliable and accurate operation.

Three analysis methods will be presented below: multiple linear regression, principal component analysis (PCA), and the Random Forest machine learning algorithm. These methods are based on different perspectives but complement each other in helping to interpret the available data and model the behavior of the system.

The dataset used for the analysis consisted of 50 repeated measurements for each motion configuration, recorded after the mechanical system had reached a stable position. Before evaluation, all measurement values were normalized to prevent differences in magnitude between the variables from influencing the analytical outcome. Outlier checks were performed using conventional statistical criteria, and no extreme values were detected that would compromise the validity of the dataset.

The choice of analytical methods was motivated by their complementary strengths. Multiple linear regression provides a direct interpretation of linear relationships between motion parameters and positioning error. PCA reveals the dominant variance structure in the measurement data and indicates whether a single motion parameter is responsible for most deviations. Random Forest regression captures nonlinear interactions and evaluates the relative importance of each parameter without requiring prior assumptions about their relationships.

The analysis was conducted by first examining the variance structure through PCA, followed by Random Forest regression to identify the most influential variables, and finally by applying multiple linear regression to quantify the contribution of each parameter within a linear framework. Model validity was checked using standard performance indicators such as the mean squared error and the coefficient of determination.

This combined analytical approach ensures a balanced evaluation of both linear and nonlinear effects and enables an independent assessment of the influence of speed, acceleration, and deceleration on the overall positioning accuracy of the system.

2.3.1. Method Implementation Details

To ensure reproducibility and to clarify how the analytical methods were applied in practice, additional data processing steps were incorporated into the workflow. The recorded camera measurements were first organized into a structured dataset containing the motion parameters and the corresponding final positioning deviations. Basic preprocessing, such as normalization and consistency checks, was carried out using standard statistical utilities available in MATLAB R2024a.

The implementation of the analytical methods followed a unified procedure: the normalized dataset was used as input for the PCA, Random Forest regression, and Multiple Linear Regression models. PCA was carried out through covariance-based decomposition to identify the dominant variance directions and extract loading coefficients that characterize the contribution of each motion parameter. The Random Forest model was built using standard ensemble regression functions, allowing the evaluation of nonlinear effect and the determination of feature importance values. Multiple Linear Regression was performed using least squares fitting routines, with multicollinearity and residual behavior inspected to validate model assumptions.

Although the exact internal scripts and parameter settings are not detailed here, the combined analytical workflow provides a robust and systematic framework for evaluating how different motion parameters influence positioning deviation. The final interpretation of the results relies on the consistency of trends observed across all three methods rather than on any single computational model.

2.3.2. Multiple Linear Regression

Multiple linear regression is a classic statistical method that assumes a linear relationship between a response variable and several explanatory variables. The purpose of the model is to predict the output and to quantitatively describe the relationship between the variables. The least squares method is used to estimate the parameters.

The advantage of this method is that it is easy to implement and easy to interpret, especially in industrial environments where the auditability of results is important. Its limitations are that it assumes a linear relationship, is sensitive to multicollinearity, and violations of model assumptions can distort the results [19]. Proper validation of the model is crucial.

In the present study, multiple linear regression was used to quantify the direct linear contribution of speed, acceleration, and deceleration to the measured positioning error. This approach makes it possible to determine whether the effect of given motion parameter scales proportionally with the resulting deviation or whether other nonlinear influences dominate the behavior.

Before fitting model, the explanatory variables were checked for multicollinearity using the variance inflation factor, which confirmed that the parameters could be analyzed independently. Residual plots were additionally examined to verify the assumptions of linearity and homoscedasticity.

The resulting regression coefficients provide a straightforward interpretation of how strongly each parameter affects the positioning accuracy when considered within a purely linear framework, supporting the comparative analysis performed with PCA and Random Forest methods.

2.3.3. Principal Component Analysis

PCA is an unsupervised learning method that creates new orthogonal principal components based on the variance of the data. This reduces the dimension of the data while minimizing information loss. It is also useful for noise filtering, visualization, and variable selection.

PCA can be used to analyze sensor data, monitor industrial processes, or as preprocessing for other machine learning models [13]. Its main advantages are the reduction in multicollinearity and the exploration of data structure. Its disadvantage is that the physical interpretation of the principal components is often difficult, and it can only handle linear relationships. In the context of this study, PCA was applied to identify which motion parameter accounts for most of the variance observed in the positioning error. Because PCA transforms the original variables into orthogonal components ordered by explained variance, it provides an objective indication of whether a single parameter dominates the behavior of the system.

The analysis revealed that the first principal component captures nearly all variance in the dataset, indicating that one motion parameter exerts an overwhelmingly strong influence on the resulting positioning deviation. This aligns with the practical expectation that speed induces more pronounced dynamic effects in belt driven actuators than acceleration or deceleration.

Before applying PCA, the input variables were standardized to ensure equal weighting, which prevents scale differences between speed and acceleration parameters from biasing the component calculation.

The results of PCA therefore serve as an independent confirmation of the findings obtained through regression based and machine learning based techniques, strengthening the robustness of the overall analytical framework.

2.3.4. Random Forest

Random Forest is an ensemble machine learning model based on the average results of many decision trees. It has excellent predictive performance and handles nonlinear complex relationship systems well. It is robust against noise and overfitting.

The algorithm is widely used in industrial processes for fault detection, predictive maintenance, and quality control [14]. Its advantages include high accuracy, robustness, and automatic variable selection. Its disadvantage is that the model can be difficult to interpret and computationally intensive on large data sets [14].

In this study, Random Forest regression was used to identify the relative importance of speed, acceleration, and deceleration with respect to the measured positioning error. Unlike linear methods, Random Forest does not assume any mathematical relationship between the variables, allowing it to capture nonlinear and interaction effects that frequently appear in dynamic mechatronic systems.

The model was trained and validated on separate subsets of the measurement data to ensure unbiased performance evaluation. The internal feature-importance metric of the Random Forest provides a direct indication of which parameter contributes most strongly to the prediction, expressed as a normalized importance value.

This method is particularly well suited for belt driven servo systems because the error generation mechanism is influenced by a mixture of linear controller dynamic and nonlinear mechanical effects, such as belt elasticity and micro-vibrations. By analyzing the feature-importance distribution, Random Forest offers a clear and robust confirmation of the dominant role of speed in shaping the resulting positioning deviation.

3. Results

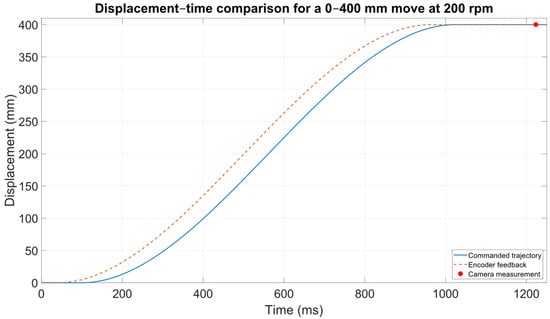

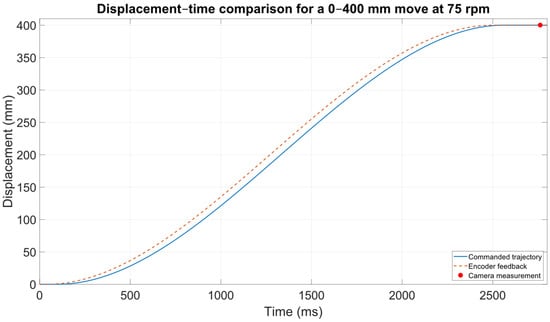

The measurement process was carried out in different configurations, with various combinations of speed, acceleration, and deceleration parameters. For each configuration, 50 consecutive positioning cycles were performed under identical environmental conditions and control parameters. In each measurement, the servo system moved to a predefined reference position, and the actual position was recorded using industrial camera. Since the camera does not provide continuous tracking during motion, the displacement-time diagram user for dynamic interpretation was reconstructed exclusively from the commanded trajectory and the servo encoder feedback. The exact timing of the motion start, the encoder-reported in-position moment, and the 200 ms PLC-triggered camera acquisition are deterministically known, allowing the camera’s single measurement to be accurately placed on the time axis as a final reference point.

The reconstructed diagram confirmed that the encoder reported target arrival significantly earlier than the mechanical system had settled. This behavior is characteristic of belt driven linear stages, where belt elasticity, microscopic slip, and the inertia of the carriage results in a small but measurable delay between the motor shaft position and the true physical position of the slider.

Figure 6 illustrates that at 200 rpm, a clear separation emerges between the command trajectory and the encoder feedback throughout the motion. The encoder reaches the nominal 400 mm target noticeably earlier than the reconstructed commanded profile, indicating premature in position signaling by the drive. The camera measurement obtained 200 ms after the nominal stop position shows a slight overshoot relative to the reference point, confirming residual mechanical settling caused by belt elasticity and dynamic deformation. This behavior of high-speed motion involves higher kinetic energy that amplifies the mechanical lag that cannot be detected by encoder-only feedback.

Figure 6.

Commanded motion, encoder feedback, and camera-measured final position during a 400 mm move at 200 rpm.

Figure 7 shows that at 75 rpm the commanded trajectory and the encoder feedback closely coincide, and the encoder reaches the target position only slightly earlier than the reconstructed command. The camera measurement recorded 200 ms later reveals only minimal deviation from the 400 mm reference, indicating significantly reduced mechanical settling compared to the high-speed case. The low displacement error and the near-perfect alignment of the curves confirm that reduced dynamic loading and smaller belt deformation enable the system to stabilize which much higher repeatability at lower speed.

Figure 7.

Commanded motion, encoder feedback, and camera-measured final position during a 400 mm move at 75 rpm.

3.1. Evaluation of Measurement Results

3.1.1. High-Speed Measurement

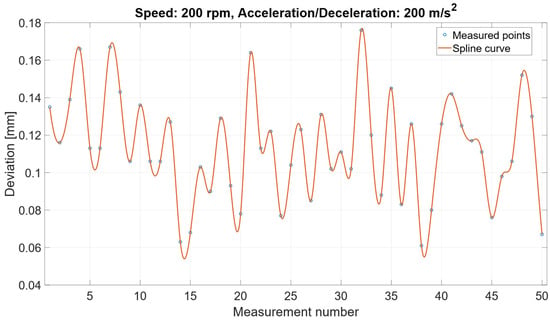

In the high-speed configuration, the nominal motor speed was set to 200 rpm, while the acceleration and deceleration were kept at 200 m/s2 according to the standard motion profile recommended by the manufacturer, which can be seen in Figure 8. Thus, the change in performance is attributed primarily to the higher speed, not to modifications of the acceleration parameters.

Figure 8.

Measured positioning deviation at 200 rpm with acceleration/deceleration set to 200 m/s2.

The final deviation measured over fifty repetitions range from 0.06 mm to 0.16 mm and showed a characteristic oscillatory pattern. This quasi-periodic behavior consists of belt elasticity, vibration modes, and micro-slips, which become more pronounced at higher speed due to increased dynamic loading, even when the acceleration and deceleration remain unchanged.

These results indicate that speed is the dominant factor influencing final positioning accuracy, whereas the acceleration/deceleration settings kept constants for all configurations do not independently contribute to increased deviation.

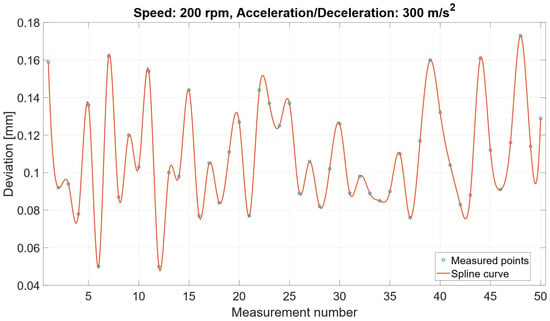

A second high-speed test was performed with the same 200 rpm nominal speed but with increased acceleration and deceleration parameters of 300 mm/s2 which can be seen in Figure 9. Although the overall magnitude of the final positioning deviation remained within the same range (0.05–0.17 mm), the deviation pattern exhibited a noticeably different oscillatory structure. The higher acceleration did not increase the average error or the standard deviation; instead, it altered the dynamic excitation of the belt carriage system, resulting in fewer but larger amplitude oscillation lobes.

Figure 9.

Measured positioning deviation at 200 rpm with acceleration/deceleration set to 300 m/s2.

This behavior supports the statistical findings that acceleration and deceleration have only a secondary influence they do not determine the magnitude of the final error, but they modulate the shape and frequency content of the residual vibration pattern. Consequently, speed remains the dominant parameter, while acceleration/deceleration primarily influence the transient dynamic without significantly affecting the final settled position.

3.1.2. Low-Speed Measurement

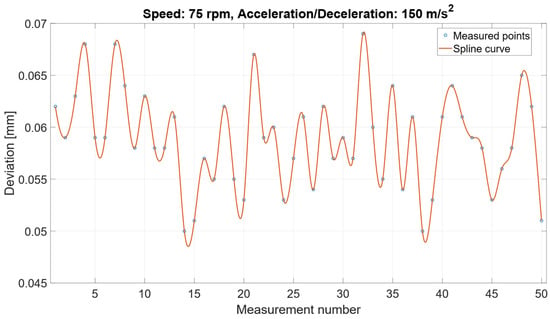

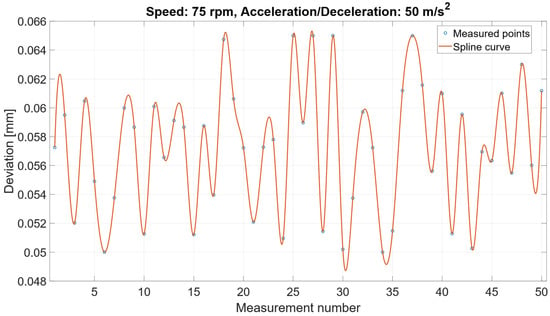

In the low-speed configurations, the shaft speed was 75 rpm, and the acceleration and deceleration were 150 m/s2 and 50 m/s2, which can be seen in Figure 10 and Figure 11.

Figure 10.

Measured positioning deviation at 75 rpm with acceleration/deceleration set to 150 m/s2.

Figure 11.

Measured positioning deviation at 75 rpm with acceleration/deceleration set to 50 m/s2.

The comparison of these datasets showed that lowering the acceleration had virtually no effect on the magnitude of the final positioning deviation. Both configurations produced nearly identical deviation ranges (approximately 0.05–0.065 mm) and very similar oscillatory patterns.

These findings indicate that the low speed the mechanical load and internal deformation of the belt carriage system is minimal, and the motion profile has insufficient dynamic excitation for the acceleration parameter to influence the final settled position. Consequently, the deviations observed at 75 rpm were dominated by the inherent elastic behavior of the belt rather than by the chosen acceleration/deceleration settings.

3.1.3. Principal Component Analysis, Random Forest, and Multiple Linear Regression

The statistical evaluation of the measurement results was carried out using three complementary analytical approaches, namely Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Random Forest regression, and Multiple Linear Regression (MLR). These techniques were applied together to provide a coherent and comprehensive interpretation of the dataset, since each method highlights a different structural aspect of the underlying relationships. PCA reveals how variance is distributed among the motion parameters, Random Forest identifies nonlinear dependencies and assesses the relative importance of each factor, while MLR quantifies the linear influence of the parameters on the final positioning deviation.

By interpreting the combined outcome of these methods within a unified analytic framework, the study ensures that the conclusion regarding parameter influence is robust, consistently reproducible, and independent of any single modeling assumption.

Based on the results of the principal component analysis, the first principal component accounted for 88.6% of the total variance, which means that the changes observed in the final positioning deviation can be described almost entirely in a single dominant direction. This dominant direction corresponded clearly to the nominal motion speed, while acceleration and deceleration contributed only marginally to the variation observed in the measurement. The detailed numerical results of the PCA, including component loadings, eigenvalues and the explained variance ratios, are summarized in Table 1, which further illustrates the dominant role of speed in shaping the behavior of the system.

Table 1.

Principal component loadings, eigenvalues, and explained variance for the motion parameters.

The loading values indicate how strongly each original variable contributes to a given principal component. As shown in Table 1, speed has a significantly higher loading in PC1 than the other parameters, confirming that the first principal component is almost entirely determined by speed. The eigenvalue associated with PC1 (2658) is also substantially larger than those of PC2 and PC3, which explains why PC1 alone accounts for 88.6% of the total variance. Acceleration and deceleration exhibit higher loadings in PC2 and PC3, respectively, but their low eigenvalues and small explained variance rations indicate that their influence on the overall deviation is minimal. This numerical structure reinforces that speed is the dominant factor governing the positioning error, while acceleration and deceleration contribute only secondary effects.

The Random Forest regression confirmed this interpretation by showing that the effect of speed was overwhelmingly dominant, reaching 92% in the model, while acceleration and deceleration contributed only between 3.5 and 4.5%. The strong correlation between the estimated and the measured deviations demonstrated that the model reliably captured the internal structure of the data.

Since the Random Forest method determines the importance of each parameter based on its contribution to reducing prediction error, the dominant role of speed reflects a genuine physical effect rather than a statistical artifact, which is consistent with the mechanical behavior of belt driven systems where increased speed leads to greater elastic deformation and more pronounced vibration phenomena.

The results of the multiple linear regression further reinforced these findings, as speed was the only parameter exhibiting a statistically significant effect on the final deviation, while acceleration and deceleration showed no meaningful linear influence. Although the explained variance of the linear model was slightly lower than that of the Random Forest regression, the consistency between the methods strengthens the reliability of the conclusions. The agreement between the linear and nonlinear models confirms that the dominant influence of speed is stable across different analytical perspectives, and that acceleration and deceleration act only as secondary modifiers of the transient dynamics without substantially altering the final settled position.

Taken together, the combined findings of PCA, Random Forest regression, and Multiple Linear regression demonstrate that speed is the primary determinant of the final positioning deviation in the examined belt driven system, while acceleration and deceleration have only minor influence on the outcome.

These results provide strong statistical and physical evidence that improvement in the positioning accuracy of belt driven stages can be achieved most effectively through careful adjustment of the operating speed while modifications of the acceleration related parameters contribute only marginal benefits.

4. Discussion

The results of the research confirm and quantitatively support the initial hypothesis that the positioning accuracy of a servo-driven linear axis is primarily influenced by rotational speed. This correlation is consistent with previous studies, which found that higher dynamic parameters increase mechanical vibrations and system inertia, leading to greater positioning errors. Similar trends have been observed in high-speed industrial actuators and robotic arms, where overshoot and control loop delay increases proportionally with speed.

This alignment with earlier findings is particularly noteworthy because the present study applies high-accuracy measurement methods to detect the final settled position of the carriage, which provides direct experimental evidence for the relationship between rotational speed and positioning accuracy.

While many previous works relied solely on encoder-based feedback, the current approach highlights the discrepancy between encoder reported and any physically measured positioning, demonstrating that mechanical settling and belt elasticity remain present even after the controller signals target arrival.

In the present study, a combination of experimental measurements and statistical analyses (PCA, Random Forest, and MLR) clearly confirmed that acceleration and deceleration parameters have only a secondary effect on positioning error. This result is also useful from a practical point of view, as it allows the optimization of motion profiles in precision applications where speed can be changed dynamically without significant modification of the acceleration phases.

The agreement between the statistical models and the physical observations indicates that although rapid acceleration may influence transient vibration modes, it does not meaningfully alter the final settled position in a belt driven system operating within the tested range. The predictive models showed a strong and consistent dominance of speed, demonstrating that the primary source of deviation is related to the dynamic excitation of the belt and carriage assembly. This behavior reflects the inherent mechanical properties of belt driven motion systems, where speed induced deformation, internal damping and micro-slip become more significant than the acceleration related excitation itself.

The results have important implications for the tuning of servo control and the predictive maintenance of high-precision electromechanical systems. Future research aims to integrate real-time adaptive control and artificial intelligence-based monitoring algorithms that can compensate for speed induced errors and increasing long term positioning stability.

Furthermore, the methodology presented in this study provides a practical framework for identifying and quantifying dynamic positioning errors, even in systems where only final position measurements are available. Since the camera delivers a single high-accuracy snapshot after the mechanical settling period, the combined trajectory reconstruction and statistical analysis approach can be extended to other belt driven or compliant drive architectures. Integrating these insights into servo tuning workflows enables more informed speed selection, improve repeatability in precision processes and enhance the reliability of the machine over its entire operational life.

5. Conclusions

The experimental results clearly confirmed that positioning accuracy is most influenced by the movement speed of the linear servo system. The effect of acceleration and deceleration was negligible in comparison. The camera-based measurement system and the data evaluation methods used reliably supported the determination of deviations.

The findings also revealed that the encoder reported position does not fully represent the true final location of the carriage, as the camera measurements captured the residual offset remaining after mechanical settling. This demonstrates that belt elasticity, micro slip, and dynamic excitation contribute measurably to the final positioning accuracy even when the controller indicates that the target position has already been reached.

The result provides an opportunity for more efficient motion profile design and targeted fine-tuning of control parameters in industrial applications requiring high accuracy. The methodology and measurement system investigated could serve as a basis for the development of predictive maintenance systems and dynamic control strategies based on artificial intelligence in the future.

In addition, the statistical analyses carried out in the study consistently showed that speed is the dominant factor determining the magnitude of the positioning deviation, while acceleration and deceleration related parameters modify the system dynamics only minimally. This insight enables engineers to optimize motion profiles primarily through speed adjustment without the need for substantial alterations to acceleration phases, making the method practical for real time industrial use.

Future research may integrate real time adaptive algorithms to compensate for speed induced errors and further enhance the long-term stability of belt driven servo systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.T. and L.G.; methodology, J.S.; software, J.S.; validation, L.G.; resources, T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S.; writing—review and editing, I.F. and L.G.; supervision, J.S.; project administration, L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MLR | Multiple Linear Regression |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PLC | Programmable Logic Controller |

References

- Mehedi, I.M.; Shah, M.H.M.; Jannat, R. Linear Positional and Speed Control of Servo Carts Using Inverse Dynamic Control. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 7411673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumanli, A.; Sencer, B. Pre-compensation of Servo Tracking Errors through Data-Based Reference Trajectory Modification. CIRP Ann. 2019, 68, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Li, B.; Ge, W.; Tan, C.; Sun, B. Analysis and Experimental Study on Servo Dynamic Stiffness of Electromagnetic Linear Actuator. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 169, 108587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanchetta, M.; Tavernini, D.; Sorniotti, A.; Gruber, P.; Lenzo, B.; Ferrara, A.; Sannen, K.; De Smet, J.; De Nijs, W. Trailer control through vehicle yaw moment control: Theoretical analysis and experimental assessment. Mechatronics 2020, 64, 102282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y. Positioning Accuracy Reliability Analysis of Industrial Robots Considering Epistemic Uncertainty and Correlation. J. Mech. Des. 2023, 145, 023303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiliç, E.; Doğruer, C.U.; Dolen, M.; Koku, A.B. Position Estimation for Timing Belt Drives of Precision Machinery Using Structured Neural Networks. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2012, 29, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahria, M.T.; Sunny, M.S.H.; Zarif, M.I.I.; Ghommam, J.; Ahamed, S.I.; Rahman, M.H. A Comprehensive Review of Vision-Based Robotic Applications: Current State, Components, Approaches, Barriers, and Potential Solutions. Robotics 2022, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, M.A.; Sims-Waterhouse, D.; Piano, S.; Leach, R. Volumetric Error Modelling of a Stereo Vision System for Error Correction in photogrammetric three-dimensional coordinate metrology. Precis. Eng. 2020, 64, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.M.; Catalucci, S.; Thompson, A.; Leach, R.; Piano, S. Applications of Data Fusion in Optical Coordinate Metrology: A Review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 124, 1341–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabanovic, A.; Sozbilir, O.; Goktug, G.; Sabanovic, N. Sliding Mode Control of Timing-Belt Servosystem. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 9–11 June 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, M.; Shen, X. A Novel Self-Actuated Linear Drive for Long-Range-of-Motion Electromechanical Systems. Actuators 2022, 11, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanesar, M.A.; Yan, M.; Isa, M.; Piano, S.; Ayoubi, M.A.; Branson, D.T. Enhancing Positional Accuracy of the XY-Linear Stage Using Laser Tracker Feedback and IT2FLS. Machines 2023, 11, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Liu, L.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Q.; Tu, X. Dynamic Error Compensation Control of Direct-Driven Servo Electric Cylinder Terminal Positioning System. Actuators 2025, 14, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piščalov, A.; Urbonas, E.; Vainorius, D.; Matijošius, J.; Kilikevičius, A. Investigation of X and Y Configuration Modal and Dynamic Response to Velocity Excitation of the Nanometer Resolution Linear Servo Motor Stage with Quasi-Industrial Guiding System in Quasi-Stable State. Mathematics 2021, 9, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.-S. Modeling of Servo Dynamic Stiffness for Multiple-Periodic Repetitive Learning Control System. Meas. Control. 2024, 58, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Liu, Q.; Madathil, A.P.; Xie, W. Predictive Digital Twin-Driven Dynamic Error Control for Slow-Tool-Servo Ultraprecision Diamond Turning. CIRP Ann. 2024, 73, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Li, S. A Data-Driven Iterative Feedforward Tuning Strategy with a Variable-Gain Feedback Controller for Linear Servo Systems. Energies 2025, 18, 3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, L. Bounded Control of PMLSM Servo System Based on Fractional Order Barrier Function Adaptive Super-Twisting Approach. Control. Eng. Pract. 2025, 154, 106131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.C.; Chao, K.; Chen, Y.R.; Early, H.L. Systemically Diseased Chicken Identification Using Multispectral Images and Region of Interest Analysis. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2005, 49, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).