Advanced Servo Control and Adaptive Path Planning for a Vision-Aided Omnidirectional Launch Platform in Sports-Training Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Multi-dimensional attention-fused perception model YOLO11-MAF: CoordAttention, ECA, MSCA and LSKA modules are simultaneously embedded into YOLO11 for the first time, enabling position-encoded, channel-interactive and multi-scale feature fusion; as a result, mAP@0.5 increases by 1.90%while 45 FPS real-time performance is preserved.

- Binary heap-enhanced Dijkstra planner: time complexity is reduced from O(V2) to O((V+E)logV) and Euclidean-heuristic pruning eliminates most redundant expansions; a novel local replanning mechanism limits replanning latency to <50 ms and yields >95% obstacle avoidance success, outperforming traditional algorithms in real-time performance and surpassing emerging strategies like IBA in path optimality.

- Hardware–software co-design for basketball robots: a ROS-2-based (humble) modular architecture integrating an omnidirectional chassis and multi-sensor fusion is proposed, guaranteeing end-to-end latency below 100 ms for on-court deployment.

2. Related Works

2.1. Visual Recognition Method

2.2. Path Planning Algorithm

2.3. Research Status of Basketball Robot

3. Materials and Methods

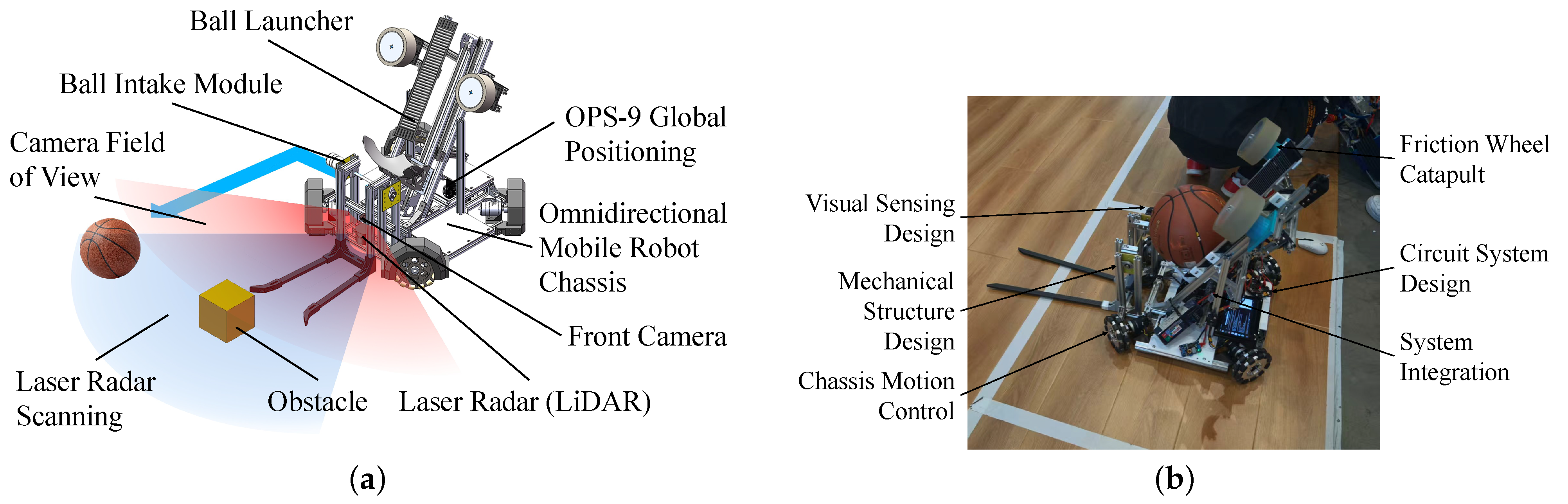

3.1. Overall Design of the Basketball Robot System

3.1.1. Mechanical Structure Design

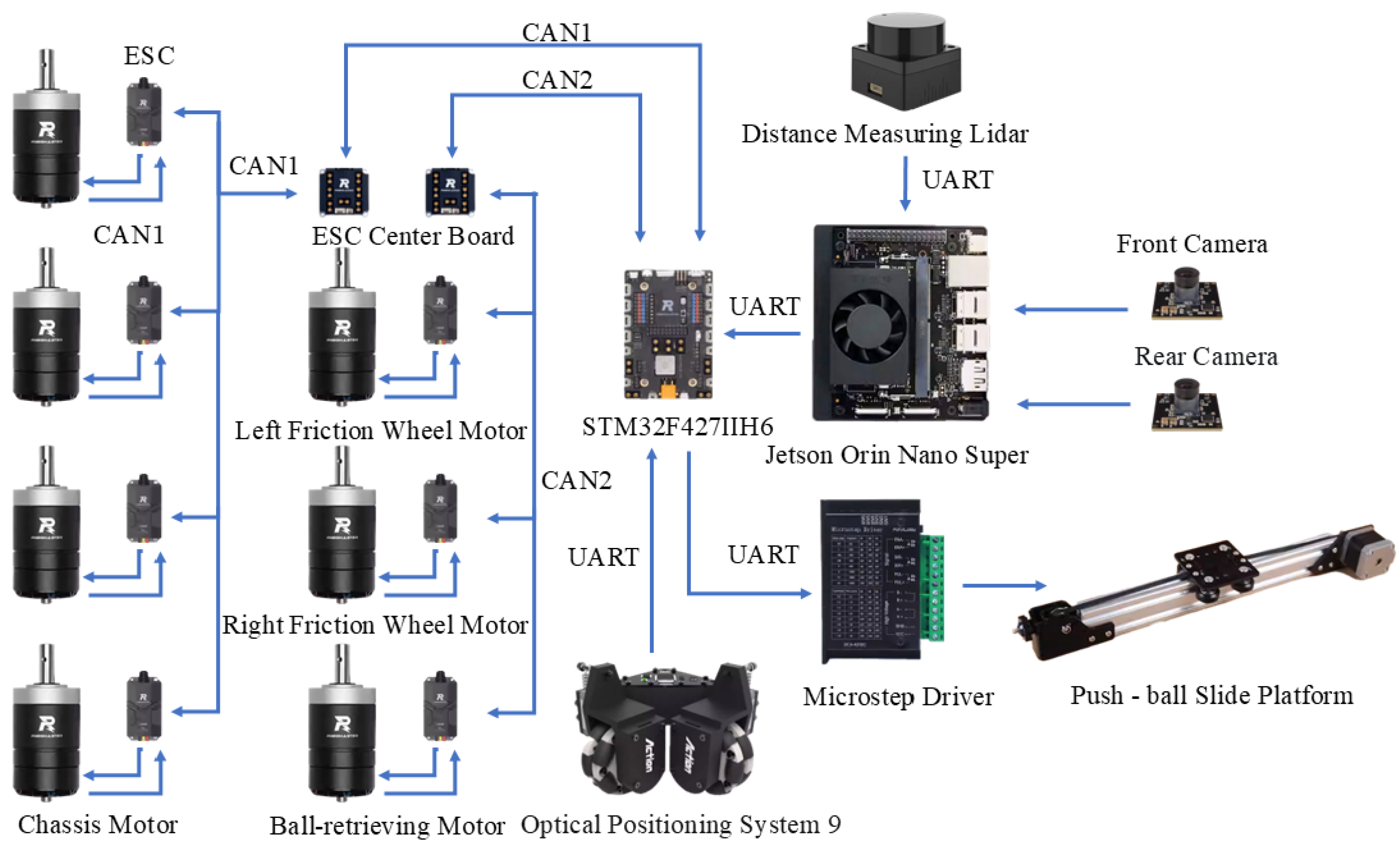

3.1.2. Electronic Hardware Architecture

3.1.3. Software System Architecture

3.2. YOLO11-MAF: The Improved Basketball Target Recognition Algorithm

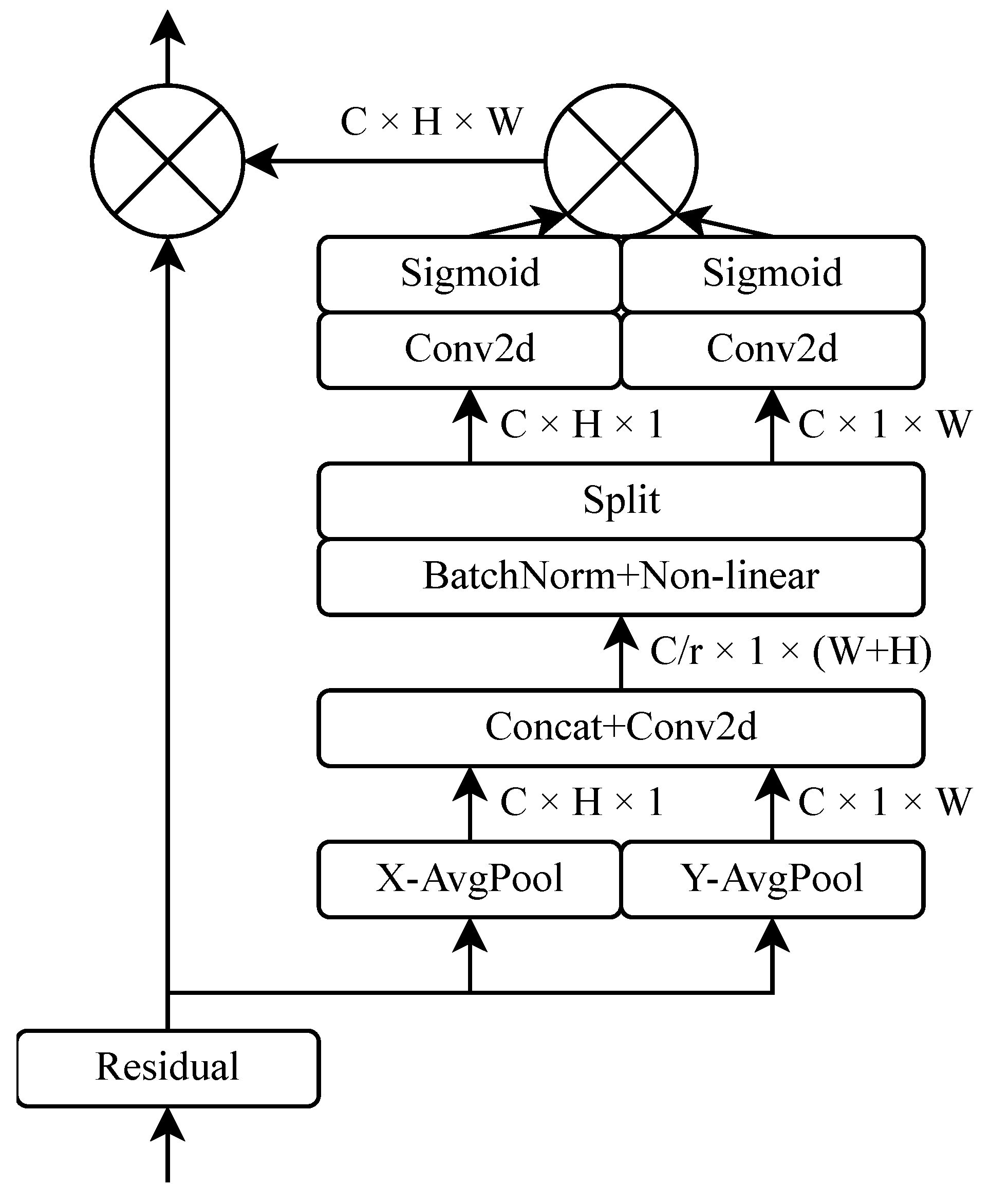

3.2.1. CoordAttention Module

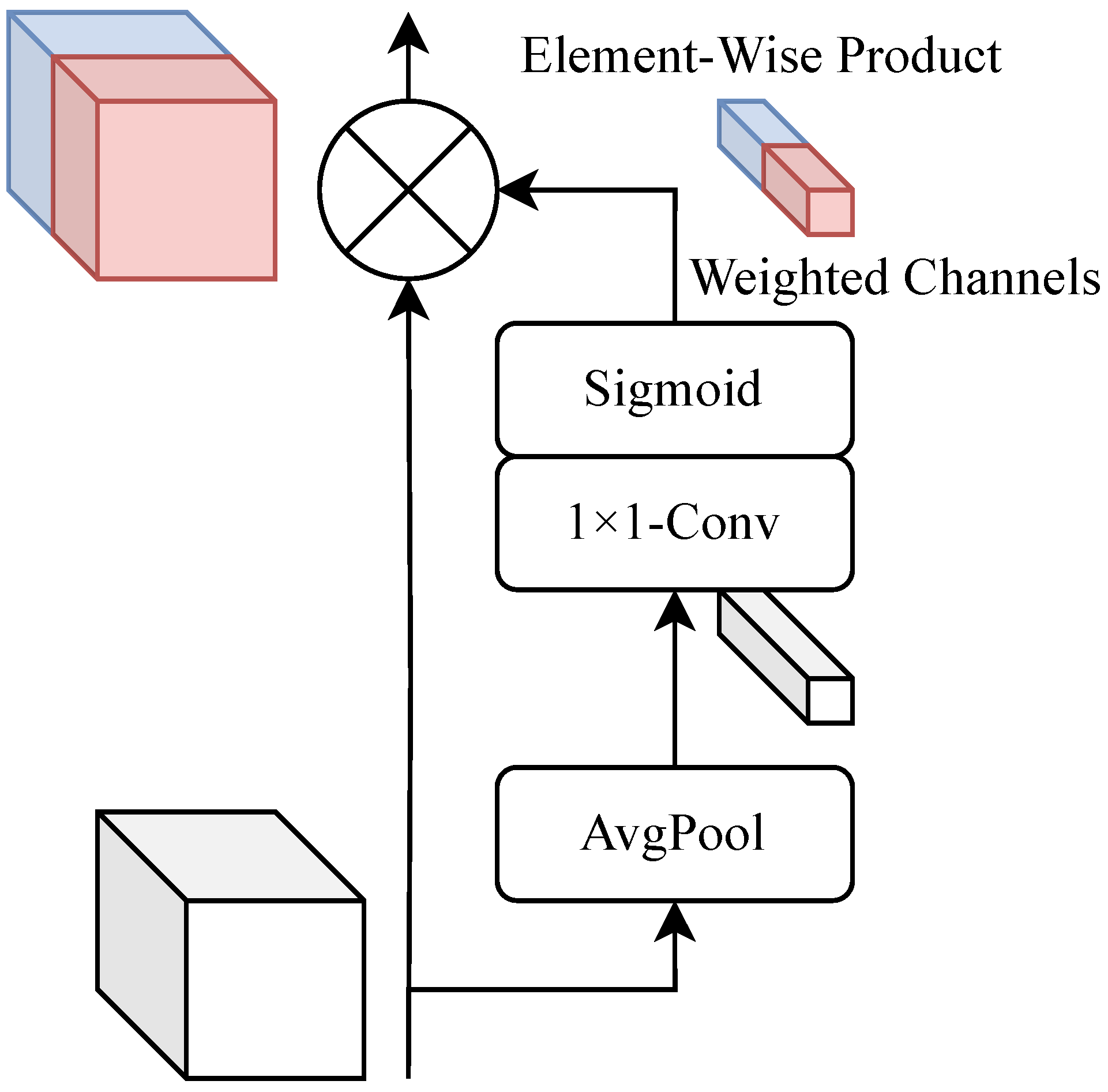

3.2.2. ECA Module

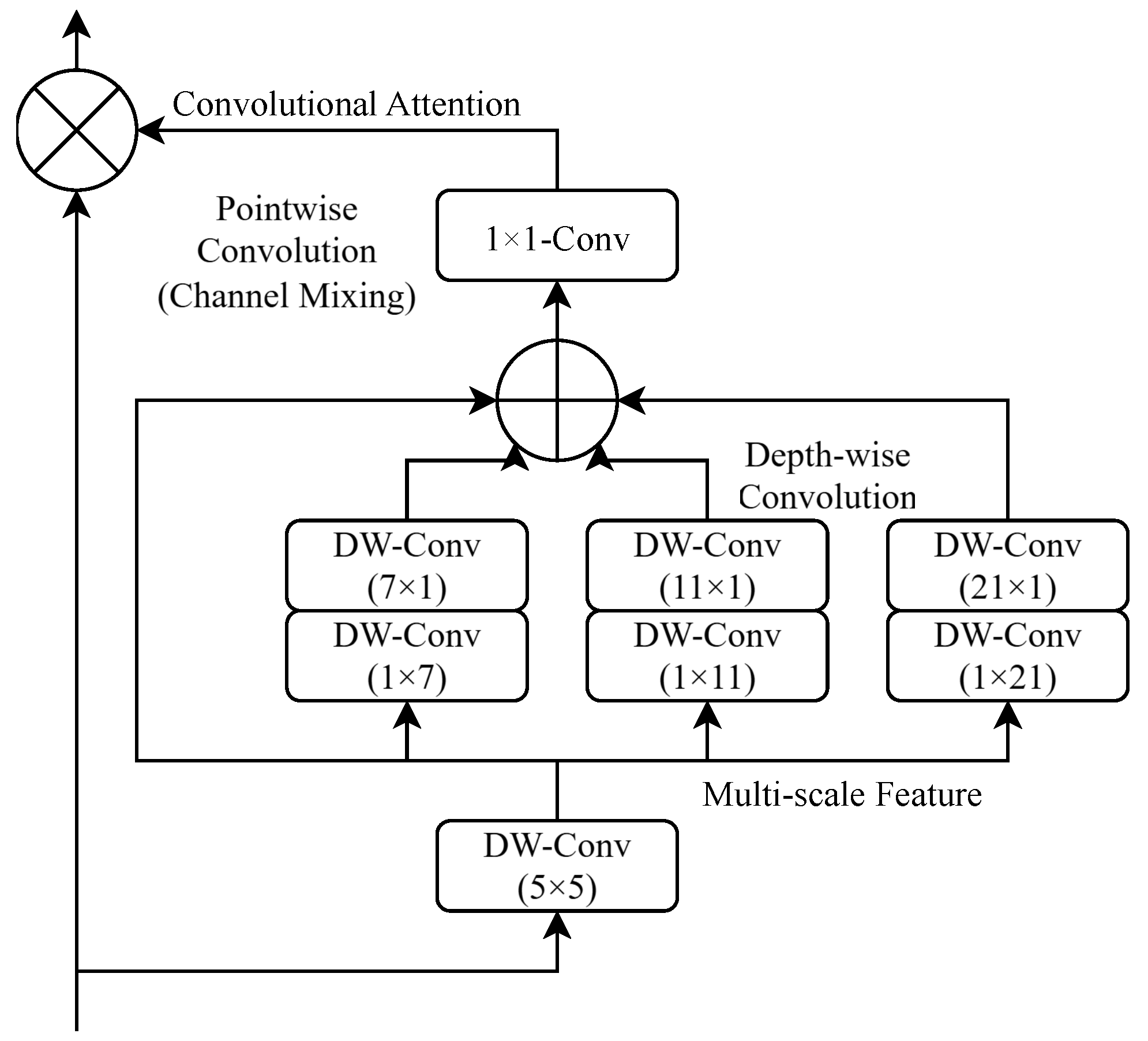

3.2.3. MSCA Module

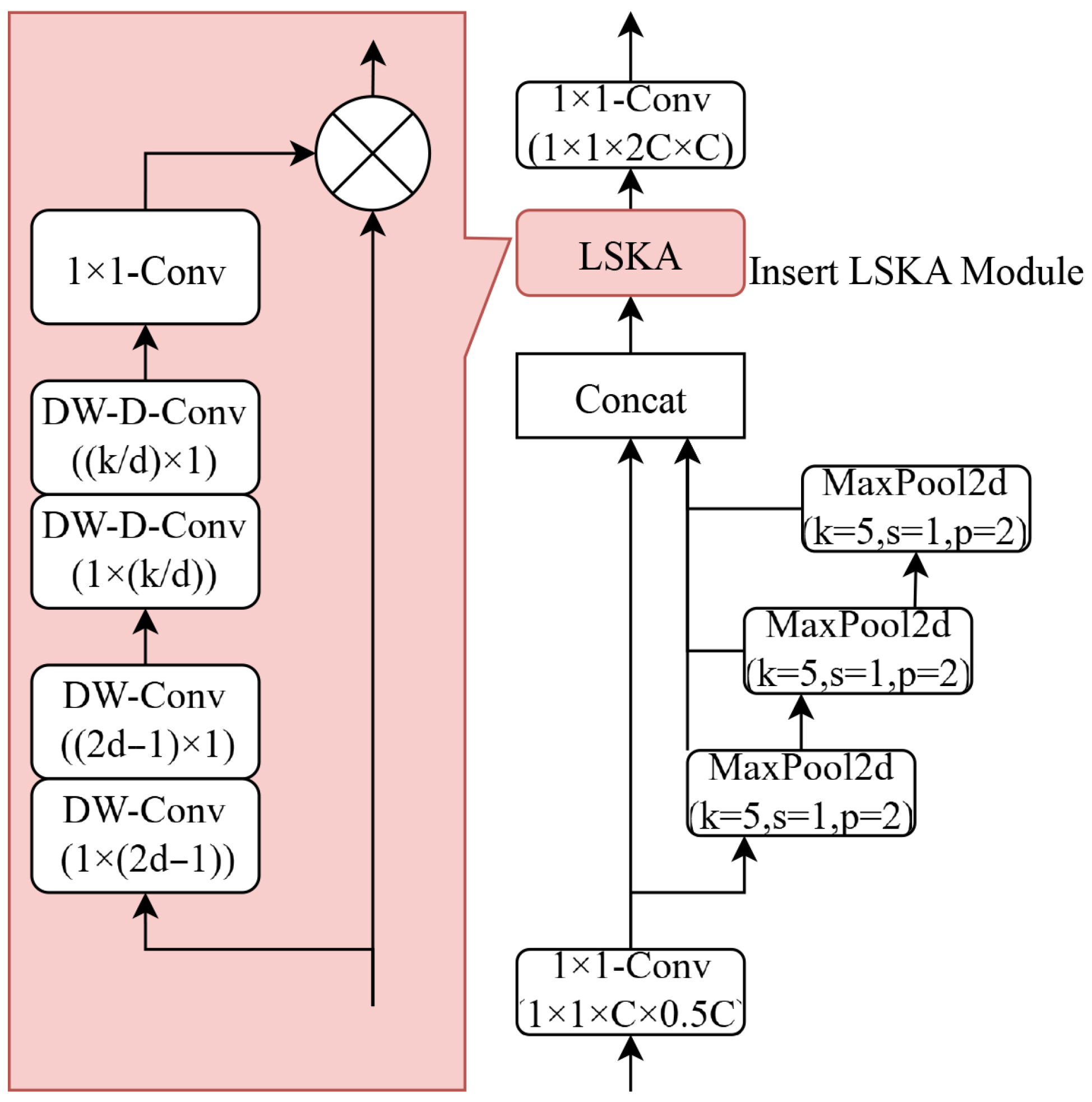

3.2.4. SPPF-LSKA Module

3.3. The Improved Dijkstra Algorithm

3.3.1. Priority Queue Optimization Based on Binary Heap

3.3.2. Heuristic Information Fusion and Priority Optimization

- When (high obstacle density, e.g., multi-robot intersection areas), to strengthen heuristic guidance toward the target and reduce invalid expansions in obstacle regions;

- When (low obstacle density, e.g., near field boundaries), to prioritize path optimality;

- When (moderate density), to balance efficiency and optimality.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Visual Recognition Performance Test

4.1.1. Dataset

4.1.2. Validation and Ablation Experiment Design

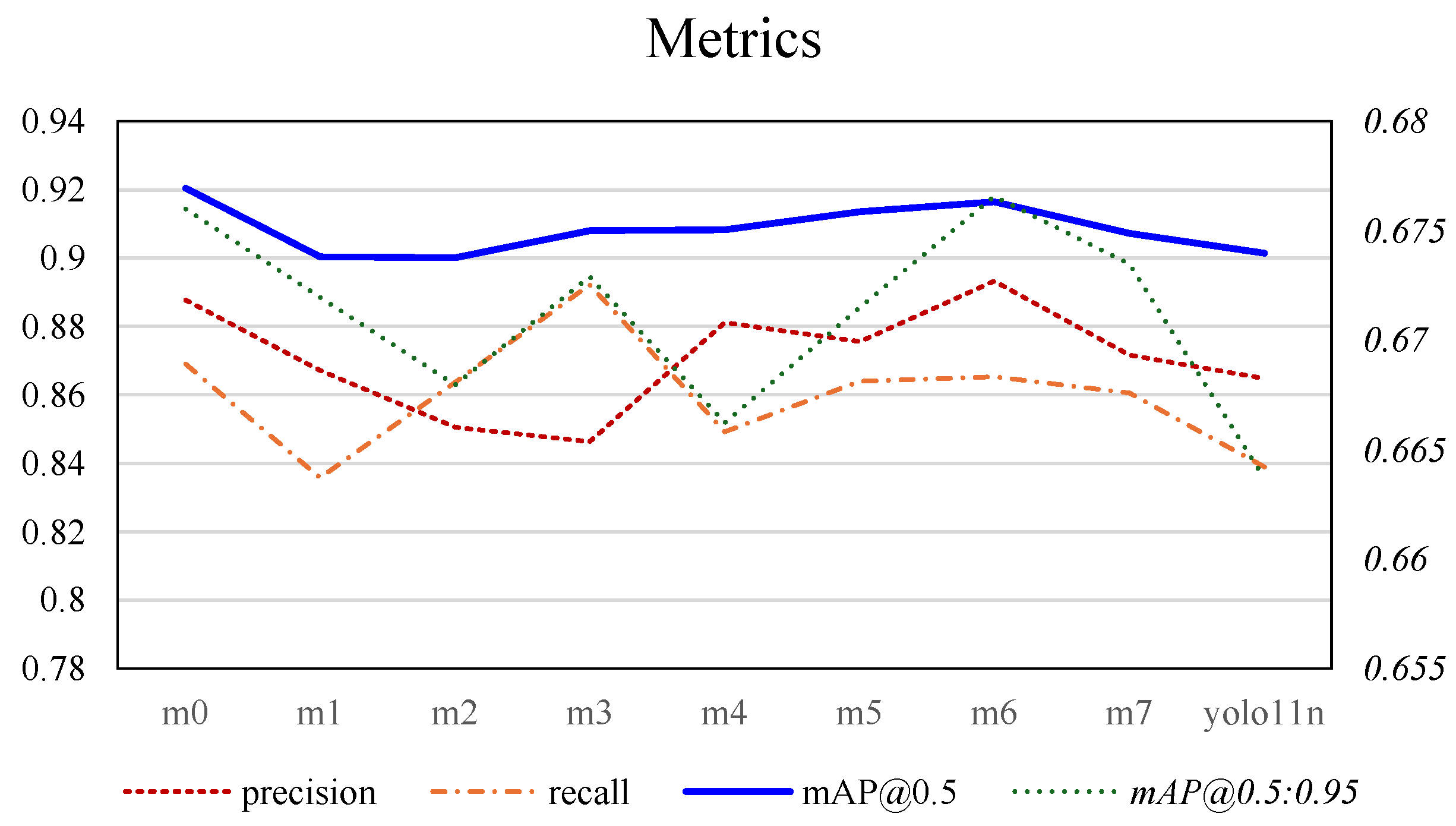

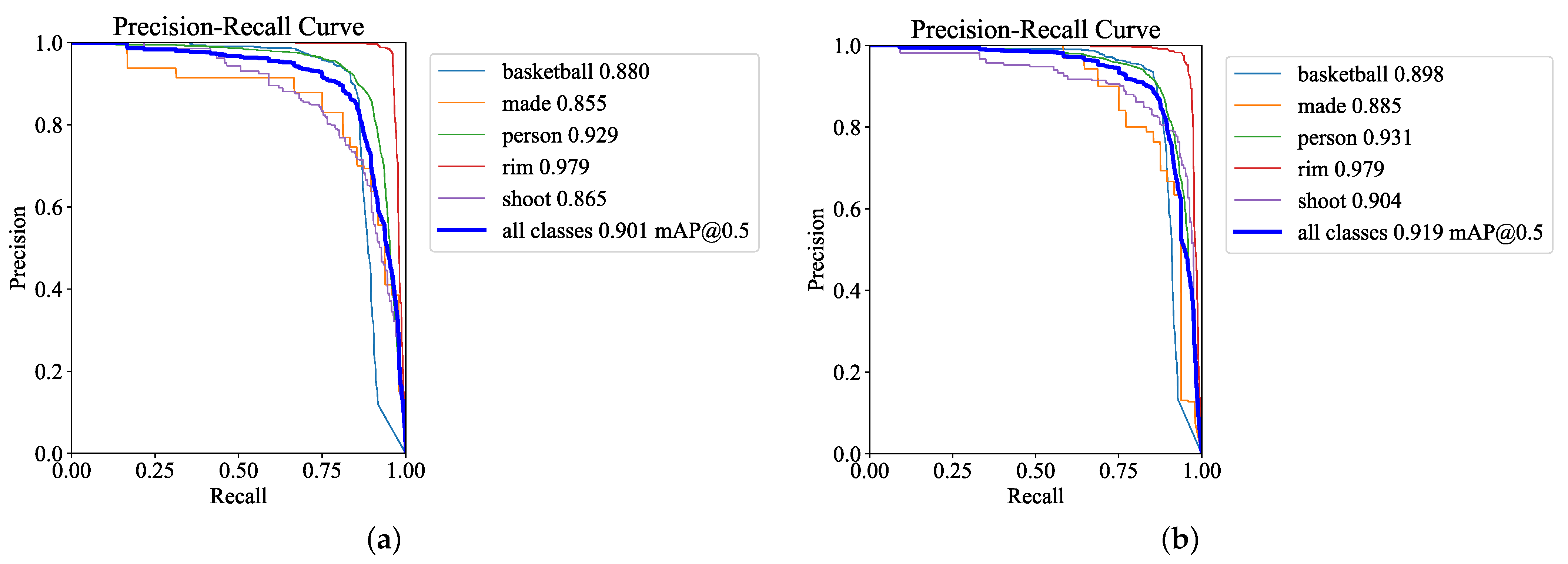

4.1.3. Validation and Ablation Experiment Results

4.2. Experimental Results of Path Planning Algorithms

4.3. End-to-End System Experimental Results

4.3.1. Passing Phase Experimental Results

4.3.2. Critical Discussion of Passing Performance

4.3.3. Shooting Phase Experimental Results

4.3.4. Critical Discussion of Shooting Accuracy

4.4. Discussion on Experimental Conditions

4.4.1. Key Assumptions and Scope

- In hardware, the robot operates on flat indoor ground without extreme environmental interference such as strong wind or intense light.

- In visual perception, the targets possess distinctive color and shape features, ensuring algorithmic identification and that no objects that are highly similar to a basketball are present in the scene.

- In path planning and motion control, the robot’s moving speed is moderate, avoiding sensor data distortion due to dynamic effects and ensuring that sensor fusion technology can effectively handle nonlinear factors such as wheel slippage, thereby ensuring the reliability of localization and navigation.

4.4.2. Model Uncertainties

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Islam, R.U.; Iqbal, J.; Manzoor, S.; Khalid, A.; Khan, S. An autonomous image-guided robotic system simulating industrial applications. In Proceedings of the 2012 7th International Conference on System of Systems Engineering (SoSE), Genova, Italy, 16–19 July 2012; pp. 344–349. [Google Scholar]

- Shahria, M.T.; Sunny, M.S.H.; Zarif, M.I.I.; Ghommam, J.; Ahamed, S.I.; Rahman, M.H. A comprehensive review of vision-based robotic applications: Current state, components, approaches, barriers, and potential solutions. Robotics 2022, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyetunji, O.; Rain, A.; Feris, W.; Eckert, A.; Zabihollah, A.; Abu Ghazaleh, H.; Priest, J. Design of a Smart Foot–Ankle Brace for Tele-Rehabilitation and Foot Drop Monitoring. Actuators 2025, 14, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohaib, M.; Pasha, S.M.; Javaid, N.; Iqbal, J. IBA: Intelligent Bug Algorithm—A Novel Strategy to Navigate Mobile Robots Autonomously. In Proceedings of the Communication Technologies, Information Security and Sustainable Development; Shaikh, F.K., Chowdhry, B.S., Zeadally, S., Hussain, D.M.A., Memon, A.A., Uqaili, M.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Jamshoro, Pakistan, 2013; pp. 291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11534–11542. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive Image Features from Scale-Invariant Keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, N.; Triggs, B. Histograms of Oriented Gradients for Human Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–26 June 2005; pp. 886–893. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Lake Tahoe, CA, USA, 3–6 December 2012; Volume 25, pp. 1097–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R. Fast r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y. The Evolution of YOLO: From YOLOv1 to YOLOv11 with a Focus on YOLOv7’s Innovations in Object Detection. Theor. Nat. Sci. 2025, 87, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. Yolov11: An overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat Radzi, S.F.; Abd Rahman, M.A.; Muhammad Yusof, M.K.A. YOLOv12-ECA: An Efficient Attention-Enhanced Detector for Real-Time UAV-Based Pothole Detection. In Proceedings of the 2025 14th International Conference on Information Technology in Asia (CITA), Kuching, Malaysia, 5–6 August 2025; pp. 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 21–25 June 2021; pp. 13713–13722. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.; Tian, F.; Qiu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zhan, R.; Zhan, J. Research on Machine Vision-Based Control System for Cold Storage Warehouse Robots. Actuators 2023, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, S.; Frazzoli, E. Sampling-based algorithms for optimal motion planning. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2011, 30, 846–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rösmann, C.; Hoffmann, F.; Bertram, T. Timed-Elastic-Bands for Time-Optimal Point-to-Point Nonlinear Model Predictive Control. In Proceedings of the 2015 European Control Conference (ECC), Linz, Austria, 15–17 July 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Xu, C.; Gao, F. Geometrically Constrained Trajectory Optimization for Multicopters. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2022, 38, 3259–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Chen, P.; Lin, K.; Zhao, K.; Ding, J.; Li, Y. Sample-efficient backtrack temporal difference deep reinforcement learning. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 330, 114613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Fu, J. Basketball robot object detection and distance measurement based on ROS and IBN-YOLOv5s algorithms. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0310494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Tao, D. Research on deep reinforcement learning basketball robot shooting skills improvement based on end-to-end architecture and multi-modal perception. Front. Neurorobotics 2023, 17, 1274543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, J.; Dong, X. Improved Q-learning-based motion control for basketball intelligent robots under multi-sensor data fusion. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 57059–57070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Tang, L. Adoption of machine learning algorithm-based intelligent basketball training robot in athlete injury prevention. Front. Neurorobotics 2021, 14, 620378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, S.; Likhachev, M. D* Lite. In Proceedings of the 18th National Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI ’02), Edmonton, AB, Canada, 28 July–1 August 2002; pp. 476–483. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Wang, P. Path Planning Techniques for Mobile Robots: Review and Challenges. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 142, 109548. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.W.J. Algorithm 232: Heapsort. Commun. ACM 1964, 7, 347–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormen, T.H.; Leiserson, C.E.; Rivest, R.L.; Stein, C. Introduction to Algorithms, 3rd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, N.; Baier, J.A.; Hernández, C. Incorporating weights into real-time heuristic search. Artif. Intell. 2015, 226, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilt, C.; Ruml, W. When Does Weighted A* Fail? In Proceedings of the 26th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-12), Toronto, ON, Canada, 22–26 July 2012; pp. 674–680. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Ibáñez, J.R.; Pérez-del-Pulgar, C.J.; García-Cerezo, A. Path Planning for Autonomous Mobile Robots: A Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model | ECA | CoordAtt | MSCA | SPPF-LSKA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| yolo11-m0 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | SPPF-LSKA |

| yolo11-m1 | ✔ | ✔ | SPPF-LSKA | |

| yolo11-m2 | ✔ | ✔ | SPPF-LSKA | |

| yolo11-m3 | ✔ | SPPF-LSKA | ||

| yolo11-m4 | ✔ | ✔ | SPPF-LSKA | |

| yolo11-m5 | ✔ | SPPF-LSKA | ||

| yolo11-m6 | ✔ | SPPF-LSKA | ||

| yolo11-m7 | SPPF-LSKA | |||

| yolo11n | SPPF |

| Model | Precision | Recall | mAP@0.5 | mAP@0.5:0.95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| yolo11-m0 | 0.897786329 | 0.86906443 | 0.920450305 | 0.676009616 |

| yolo11-m1 | 0.867136376 | 0.835704399 | 0.90051382 | 0.671960307 |

| yolo11-m2 | 0.850457417 | 0.863826924 | 0.900105601 | 0.667979664 |

| yolo11-m3 | 0.846417603 | 0.8922018 | 0.907951938 | 0.672894904 |

| yolo11-m4 | 0.881252536 | 0.849166824 | 0.908367057 | 0.666251825 |

| yolo11-m5 | 0.875701261 | 0.864030006 | 0.913642406 | 0.671490847 |

| yolo11-m6 | 0.893377074 | 0.8654571 | 0.916381936 | 0.676582832 |

| yolo11-m7 | 0.871780955 | 0.860571003 | 0.907361924 | 0.673468277 |

| yolo11n | 0.864695559 | 0.838904681 | 0.901489216 | 0.663698118 |

| Path A* | Path Imp. D | Time A* (ms) | Time Imp. D (ms) | Impr. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 599 | 599 | 188.1 | 157.5 | 16.2 |

| 0.10 | 599 | 599 | 158.4 | 134.3 | 15.2 |

| 0.20 | 599 | 599 | 143.0 | 123.4 | 13.7 |

| 0.30 | 599 | 599 | 119.2 | 109.4 | 8.2 |

| Algorithm | Map Size | Avg. Runtime/ms | Avg. Path Length | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Dijkstra | 100 × 100 | 2768.6 | 199 | Sequential, , not real-time |

| Improved Dijkstra | 300 × 300 | 124.0 | 602 | Heap + heuristic, |

| A* | 300 × 300 | 140.4 | 602 | Optimal, slightly slower |

| Metric | Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recognition Success Rate (%) | 98.3 | 98.3 | 96.7 |

| Passing Completion Rate (%) | 98.3 | 95 | 96.7 |

| Interference Avoidance Success Rate (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Average Planning Time (ms) | 124.5 | 124.9 | 124.6 |

| Return-to-Start Rate (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Metric | Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recognition Success Rate (%) | 98.3 | 98.3 | 98.3 |

| Shooting Success Rate (%) | 96.7 | 95 | 96.7 |

| Interference Avoidance Success Rate (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Average Planning Time (ms) | 125.0 | 124.7 | 124.8 |

| Return-to-Start Rate (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, S.; Xie, Y.; Huang, K.; Lang, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhuang, Y. Advanced Servo Control and Adaptive Path Planning for a Vision-Aided Omnidirectional Launch Platform in Sports-Training Applications. Actuators 2025, 14, 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120614

Wang S, Xie Y, Huang K, Lang J, Liu Q, Zhuang Y. Advanced Servo Control and Adaptive Path Planning for a Vision-Aided Omnidirectional Launch Platform in Sports-Training Applications. Actuators. 2025; 14(12):614. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120614

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Shuai, Yinuo Xie, Kangyi Huang, Jun Lang, Qi Liu, and Yaoming Zhuang. 2025. "Advanced Servo Control and Adaptive Path Planning for a Vision-Aided Omnidirectional Launch Platform in Sports-Training Applications" Actuators 14, no. 12: 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120614

APA StyleWang, S., Xie, Y., Huang, K., Lang, J., Liu, Q., & Zhuang, Y. (2025). Advanced Servo Control and Adaptive Path Planning for a Vision-Aided Omnidirectional Launch Platform in Sports-Training Applications. Actuators, 14(12), 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120614