Abstract

This study investigates the issue of fault-tolerant motion control in the distributed chassis system (DCS) subject to degradation in independent steering actuators. First, the dynamic behavior of the independent steering system is analyzed to establish a fault-dynamics model for independent steering. The steering powertrain degradation coefficient is then mapped to the contraction of the feasible tire-force region. Subsequently, the model predictive controller (MPC) is designed to solve for the required generalized forces/torques. Moreover, along the direction of the generalized demand force vector, the boundary values for the current cycle are obtained and used to correct the generalized demand force. Finally, an adaptive weighting scheme for the tire force distribution objective function, which accounts for degradation coefficients, is proposed. Sequential quadratic programming (SQP) is employed to achieve optimal utilization of tire forces. Simulation studies for different steering degradation scenarios and road conditions are conducted using a CarSim 2019 and Simulink 2021B co-simulation platform. The simulation results demonstrate that the proposed integrated chassis motion controller maintains excellent motion control performance even under independent steering actuator degradation.

1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of X-by-wire technology, motor technology, and auto-motive intelligence, electric vehicles are progressively replacing traditional mechanical linkages with X-by-wire control systems [1], which improve the chassis system’s performance in handling [2], energy-saving control [3,4], and active safety [5], and provide an advanced actuation platform for automated driving in mixed traffic—for example, in social interaction-aware scenarios [6], lane-change interactions with asymmetric driving aggressiveness [7], and interaction scenarios between automated vehicles and cyclists [8].

However, the elimination of mechanical linkages and the introduction of more complex vehicle electrical systems significantly increase the failure rate [9,10,11], particularly during high-intensity or prolonged driving under complex and variable road conditions [12]. Therefore, the implementation of fault-tolerant control (FTC) is essential to ensure the reliability and safety of vehicle operation, maintaining stability and controllability even in the presence of component failures and thereby preventing severe unstable maneuvers [13]. This need for enhanced safety has stimulated the development of distributed chassis systems (DCS). A typical example is the distributed-drive electric vehicle, in which propulsion is provided by hub motors, while the steering system still retains a conventional steering trapezoid. As a more advanced DCS configuration, the integrated autonomous wheel module (IAWM) vehicle achieved four-wheel independent drive (4WID) and four-wheel independent steering (4WIS) [14,15], thereby offering a higher degree of hardware redundancy that is especially attractive for fault-tolerant control. Building on this architecture, we develop a steering fault-tolerant control strategy for IAWM vehicles in this work.

1.1. Related Work and Motivation

Most existing steering FTC studies focus on active steering systems. From a control perspective, these studies can be broadly classified into three categories: (i) actuator-level FTC; (ii) robust-control approaches, which treat faults as the uncertainties in the DCS; (iii) control allocation methods, which actively coordinate the capabilities of DCS actuators.

For the first category, Fekih et al. [16] proposed an adaptive controller with look-ahead technology to address automatic steering under actuator failure. Huang C et al. [17] proposed a predictive fault-tolerant control algorithm. This algorithm is based on sensitivity estimation and exponential forgetting recursive least squares, aiming to maintain superior steering performance under various actuator faults. Nevertheless, the limitations of this approach become apparent in the event of irreversible actuator failures.

For the second category, faults are treated as disturbances or uncertainties, and robustness is enhanced at the controller level. Guo et al. [18] proposed a robust H∞ FTC system for four-wheel steering vehicles that addresses actuator failures and parameter uncertainties. Cao et al. [19] established a fault model, then developed a linear parameter-varying robust H∞ controller. Polyakov [20] developed fixed-time stabilization methods for linear systems with bounded matched uncertainties. Ning and Han [21] proposed prescribed finite-time consensus tracking protocols for multi-agent systems under bounded uncertainties. Tong et al. [22] considered the effects of parameter variations and actuator failures on the system and proposed a sliding mode variable structure controller to achieve FTC. Jing et al. [23] proposed a novel integration of T-S fuzzy modeling with an adaptive event-triggering mechanism to achieve robust fuzzy passive fault-tolerant control under actuator failure scenarios. However, the second approach can only address failures that are predefined in the controller design, resulting in relatively conservative controller performance. Consequently, it is frequently employed in scenarios where elevated system precision is not a prerequisite.

For the third category, Li et al. [24] established a steering angle allocation method based on the position of the faulty wheel, which was successful in achieving effective control of vehicle motion. Hu et al. [25] proposed a novel adaptive multivariable super-twisting control algorithm for differential drive assisted steering, ensuring vehicle safety in the event of active-steering motor failure. Faïza et al. [26] enabled the vehicle to navigate to the emergency lane during steering system failures by appropriately allocating steering angle and wheel braking torque. Chen et al. [27] employed a nonsingular terminal sliding mode controller to regulate front wheel drive torque, tracking the desired front road wheel angle while accounting for the coupling characteristics between steering angle and drive torque. Wu et al. [28] adapted a tube-based MPC to maintain path tracking performance through direct yaw rate control. Zhao et al. [29] proposed a centralized fault prevention control method based on MPC that incorporates a motor thermal model. These works clearly demonstrate the potential of using actuator redundancy in DCS to reallocate control tasks under steering faults.

However, relatively little work has focused on fault-tolerant control for IAWM vehicles [14]. Existing steering FTC studies for over-actuated EVs typically use simplified fault representations [30,31,32]. For example, they often omit the post-fault dynamics of independent steering actuators and treat faults as exogenous disturbances, or they neglect the faulty wheel’s potential contribution to vehicle motion and idealize its steering angle as locked after failure. Consequently, these approaches neither quantify how degraded actuator capability constrains the achievable tire forces nor provide a systematic way to exploit the remaining steering authority of degraded wheels together with healthy actuators to maintain vehicle stability and tracking. In IAWM vehicles, where each wheel has both distributed drive and independent steering, actuator degradation can reshape the attainable generalized force and moment set. This motivates the development of an integrated FTC framework for IAWM vehicles that combines generalized-force boundary computation with tire-force feasible-region analysis under steering-actuator degradation.

1.2. Contributions and Paper Organization

The contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- (i)

- A fault-inclusive steering dynamics model is developed and analyzed by explicitly incorporating steering motor torque degradation coefficients into the independent steering system. This model establishes a quantitative mapping from the degradation coefficients to the contraction of the corresponding tire-force feasible domain.

- (ii)

- A tire-force allocation method is proposed based on the contracted feasible domain. Within each control cycle, the demand generalized force is initially solved under one-dimensional generalized force/torque boundary constraints. Subsequently, boundary optimization is performed to obtain the boundary values along the direction of the current demand generalized force vector, thereby correcting the demand generalized force, eliminating infeasibility or abrupt switching problems that occur in conventional tire-force distribution.

- (iii)

- An adaptive target weighting scheme is proposed, involving the steering fault factor into the weighting component of the tire force distribution objective function, which enables management using the same optimization objective function before and after faults occur. Ultimately, the SQP algorithm is employed to solve this optimization problem, yielding the target tire forces.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the DCS chassis architecture and system models employed in the control software design. Section 3 develops an integrated chassis fault-tolerant motion controller that accounts for actuator failure constraints. Section 4 presents simulation results. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. System Structure and Related Models

This section first presents the structure of the IAWM vehicle and then introduces four related models: The first model is a three-degree-of-freedom planar vehicle dynamics model with longitudinal and lateral tire forces as inputs, which characterizes the coupled longitudinal-lateral-yaw motion of the vehicle body. The second model is a steering dynamics model based on an independent steering mechanism, describing the relationship among the steering actuator’s output torque, tire forces, and wheel steering angle. The third model is a fault-domain model that maps the steering actuator degradation coefficient to a contraction of the tire force feasible domain, thereby quantifying how failures reduce the available tire forces. The fourth model describes the transformation relationship between tire forces in the tire coordinate system and those in the vehicle coordinate system.

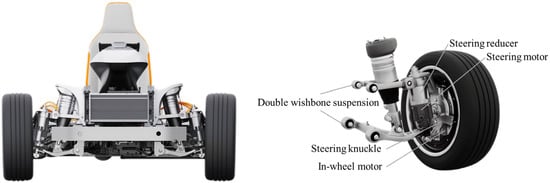

2.1. Structure of the Vehicle

The electric vehicle chassis used in this paper consists of the vehicle body and four IAWMs. The structural design of the IAWM and vehicle is illustrated in Figure 1. The IAWM is equipped with a kingpin steering system, a hub-motor direct-drive system, mechanical friction braking, and a double wishbone suspension. Hub-style outer-rotor motors are used to drive the wheels and provide regenerative braking torque. The wheels are steered independently by motors mounted on the kingpin axis. The hub motor and friction braking system together respond to braking requests for each wheel. The well-established double wishbone suspension is used to connect the IAWM to the vehicle body.

Figure 1.

IAWM and vehicle.

2.2. Vehicle Dynamics Model

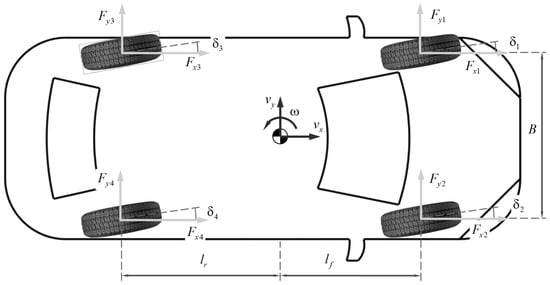

To derive the planar vehicle dynamics model, the following assumptions are introduced: (i) The vertical motion of the vehicle body, as well as roll and pitch dynamics, are neglected. (ii) The tire forces are treated as known inputs to the vehicle model.

Under assumptions (i)–(ii), the three-degree-of-freedom planar vehicle dynamics model is obtained, as shown in Figure 2. This model includes longitudinal and lateral linear degrees of freedom, as well as a rotational degree of freedom for yaw. The vehicle dynamics equations [33], derived in the vehicle coordinate system using Newton’s second law, are as follows:

where is the mass of the vehicle; represents the yaw moment of inertia; and indicate the longitudinal and lateral velocities, respectively; is the yaw rate; , and denote the generalized longitudinal force, generalized lateral force, and generalized yaw moment of the vehicle in the vehicle coordinate system, respectively; and represent tire longitudinal forces and tire lateral forces in the vehicle coordinate system, respectively; denotes the wheel track; and are the distances from the center of mass to the front and rear axles, respectively. In the following text, the index is used to distinguish the four wheels defined in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Vehicle plane dynamic model. The arrows in the figure indicate the positive directions of the vehicle coordinate system.

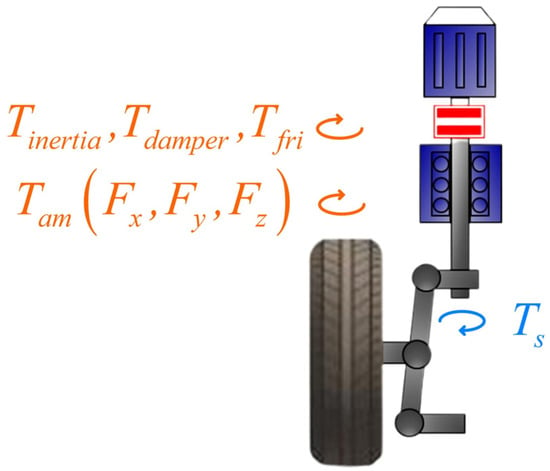

2.3. Independent Steering System Model

Compared to traditional electric power steering systems, the independent steering system (ISS) replaces the torque applied by the steering knuckle arm on the kingpin with the output torque from a reduction motor mounted on the kingpin. Therefore, the dynamic model for the ISS can be constructed by referencing the electric power steering system [34]. The ISS dynamic equation obtained from Figure 3 is as follows:

where and are the moment of inertia and the damping coefficient around the kingpin, respectively; is the friction moment around the kingpin; is the aligning moment generated by tire forces at the kingpin axis; is the output torque of the steering powertrain; , , and indicate the lateral tire force aligning moment, longitudinal tire force aligning moment, vertical tire forces aligning moment, and tire elastic aligning moment, respectively; and is the road wheel angle.

Figure 3.

Independent steering dynamics analysis.

By considering the wheel alignment parameters, , and are obtained by computing the moments of the tire longitudinal, lateral, and vertical forces about the kingpin axis.

where , and are the tire longitudinal forces, tire lateral forces, and tire vertical forces in the tire coordinate system, respectively; is the effective rolling radius of the tire; is the kingpin caster angle; is the kingpin inclination angle; is the kingpin offset distance.

In the longitudinal direction, the tangential tire force acts at a point behind the center of the contact patch, and this longitudinal offset is referred to as the pneumatic trail. In the lateral direction, tire sideslip causes the application point to be displaced from the longitudinal centerline of the patch, and these longitudinal and lateral deformations together generate an elastic aligning moment. Therefore, is described as shown in Equation (4).

where is the pneumatic trail; is the lateral translating deformation of the carcass; and represents the cornering tire stiffness.

2.4. Mapping Model of ISS Degradation to the Tire Force Feasible Region

Current research has categorized failures in steering system actuators [35,36], primarily including lock-in-place failure, loss of output effectiveness, and floating actuator failure. By combining the power transmission route along the kingpin axis during the generation of road wheel angle, it can be observed that the causes of lock-in-place failure primarily stem from motor electrical faults and mechanical failures, such as interturn short circuits or abnormal structures in mechanical transmission components. When an electrical fault occurs, the electrical energy input to the motor cannot be effectively converted into mechanical energy and is almost entirely dissipated as heat. Upon detecting a temperature rise, the MCU triggers the predefined torque-limiting logic in the software, meaning the higher the temperature, the lower the motor’s output torque becomes until thermal shutdown occurs or the MCU actively disables itself. On the other hand, mechanical structure abnormalities are often caused by long-term fatigue or instantaneous impacts. These can be equated to a sudden increase in transmission chain friction, manifesting as a persistent and measurable lag in motor speed response—that is, a reduction in the net torque driving the road wheel steering. Thus, lock-in-place failure can be equated to loss of output effectiveness. For floating actuator failure, its essence lies in the external reaction torque acting on the wheel exceeding the maximum controllable torque available in the current state, thereby disrupting torque equilibrium and causing unintended wheel displacement. Consequently, the failure can be logically equated to a degradation in the motor’s output torque capability, which fails to meet closed-loop control requirements. In summary, these common faults can be characterized by setting the decay coefficient of the motor’s maximum output torque. Degradation scenarios account for a significantly higher proportion of steering actuator failures than complete failure, and implementing reasonable risk warnings and compensatory strategies during the degradation failure conditions can reduce the probability of complete failure. Thus, the following context will focus on degradation scenarios for steering actuators.

The ISS model is simplified under the following assumptions so as to facilitate the controller design presented in the subsequent sections:

- (i)

- To facilitate controller design, the actuator degradation coefficient is mapped to the steady-state boundary of the feasible tire-force domain. Furthermore, since the road-wheel steering motion is predominantly confined to low-frequency motions, the inertia and viscous damping torques associated with the steering rate are neglected.

- (ii)

- Existing tests indicate that the friction moment around the kingpin does not exceed 5 Nm [37], which is significantly smaller than the tire force aligning torque or tire elastic aligning torque. Thus, it is neglected in subsequent analyses.

- (iii)

- Considering the small magnitude of lateral translating deformation of the carcass caused by tire sidewall deflection [38], this effect is also neglected.

- (iv)

- To avoid boundary contraction errors due to model uncertainty, the decay of the pneumatic trail with the tire lateral deflection angle [38] is ignored, and the pneumatic trail at zero lateral sideslip angle is directly used.

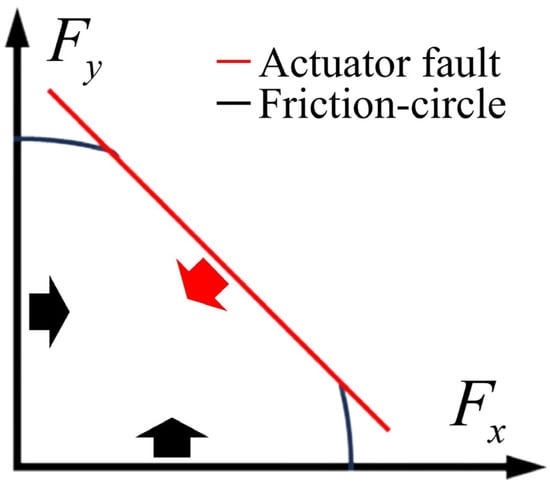

Finally, introducing the degradation coefficient into the ISS steady model, Equation (5) can be obtained as follows:

where is the maximum output torque of the steering powertrain, and , and denote the moment arms of the longitudinal, lateral, and vertical tire forces about the kingpin axis, respectively. is the maximum value of the pneumatic trail.

By organizing the actuator saturation described in Equation (5) and the tire friction circle, the feasible domain for tire force correction can be derived, as shown in Figure 4. The red line (Actuator fault) denotes the actuator-fault constraint boundary, and the black curve (Friction-circle) denotes the tire–road friction-circle boundary, while the arrows indicate that the region between these boundaries is the feasible tire-force domain.

Figure 4.

Tire force corrected feasible region (first quadrant).

2.5. Coordinate System Transformation

The conversion method from the tire coordinate system to the vehicle coordinate system is illustrated as follows:

3. Integrated Chassis Fault Tolerant Motion Controller Design

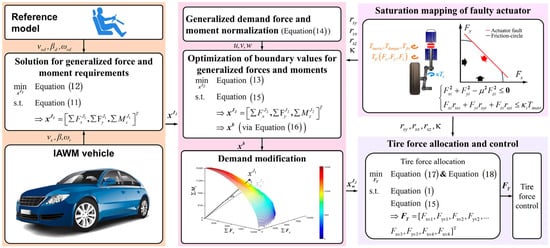

This paper presents an integrated chassis fault tolerant motion controller, illustrated in Figure 5. The controller comprises two components: a generalized force/moment generator and a tire force allocation and control system.

Figure 5.

Structure of the integrated chassis fault tolerant motion controller.

The generalized force/moment generator firstly takes the target values of longitudinal vehicle speed, vehicle sideslip angle, and yaw angular velocity, along with actual vehicle feedback, as inputs. Subsequently, based on the optimization problem , the MPC-based controller uses the one-dimensional maximum values to construct three-dimensional constraints and computes the driver’s control demands in the longitudinal, lateral, and yaw directions of the vehicle at the current control step. These demands define the search direction for the next optimization stage. Under the tire friction-circle and faulty-actuator constraints, the controller then formulates the optimization problem and solves it to obtain the boundary values of the generalized forces and yaw moment within the physically feasible region. Finally, it compares the driver-demanded generalized forces and yaw moment at the current step with these boundary values and adjusts them accordingly, yielding an implementable, fault-tolerant generalized force/moment command.

The module for tire force allocation and control converts implementable generalized force/moment into hub motor moments and road wheel angles, comprising both tire force allocation from generalized correction forces and tire force control. In the tire force allocation stage, the desired tire forces are obtained by solving the optimization problem . The steering actuator fault factor is explicitly embedded in the objective function of , so that the influence of the faulty steering actuator on the available tire-force domain is reflected. At the same time, incorporates the vehicle’s longitudinal, lateral, and yaw dynamics together with the actuator limits and the tire friction ellipse. An SQP algorithm is used to solve and compute the target tire-force command for each wheel. Within the tire force control model, the target longitudinal tire force is mapped to the hub motor moment using the wheel rotation dynamics model. The target lateral tire force is mapped to the tire slip angle via the tire side inverse model, which is then converted into the road wheel angle.

3.1. Generalized Force/Moment Generator

The vehicle’s desired longitudinal velocity is derived based on the driver’s acceleration and deceleration requests. To meet the driver’s desired yaw response, the desired yaw rate is calculated using a single-track model. Concurrently, the vehicle’s motion posture is constrained by the road surface friction coefficient to determine the upper limit of the absolute value of the yaw rate.

where , and represent the target values for longitudinal vehicle speed, vehicle sideslip angle, and yaw angle velocity, respectively; is the initial value of the longitudinal speed; is the given value of the longitudinal acceleration; is the vehicle wheelbase; is the understeer gradient; is the dimensionless coefficient used to compensate for model uncertainty; is the road adhesion coefficient; and is the gravitational acceleration.

Equation (1) is discretized as:

where is the sampling period, and is the current sampling time.

Set the state vector, .

Set the input variable, , where , and are the longitudinal velocity, lateral velocity, and yaw rate at the current moment, respectively.

Equation (8) is linearized as:

where , , , is the system output.

To apply MPC [39], a new state variable is constructed as .

The predictive model is further derived as follows:

where is the identity matrix, and is a matrix that consists entirely of zeros, .

During the optimization calculation of the vehicle’s generalized forces, the characteristics of the friction circle and the output of the faulty actuator should be taken into account. However, the coupled property of the vehicle’s generalized forces under tire friction constraints is difficult to explicitly characterize, where one increases as others may decrease [40]. This paper temporarily ignores this coupling and directly employs the upper and lower bounds of the single-dimensional generalized force as constraints. Consequently, the simplified generalized force constraint is derived as:

where is the road adhesion coefficient, and is the maximum output torque of the hub motor.

To achieve rapid convergence of state variables while imposing input constraints, the optimization objective function is formulated as follows:

where , and are the diagonal matrix with weighting factors, is the prediction horizon, is the control horizon, denotes a non-negative slack variable introduced to soften the constraints, and is the weighting factor for .

The optimal solution to the objective function defined by Equation (12) under the constraints of Equation (11) is .

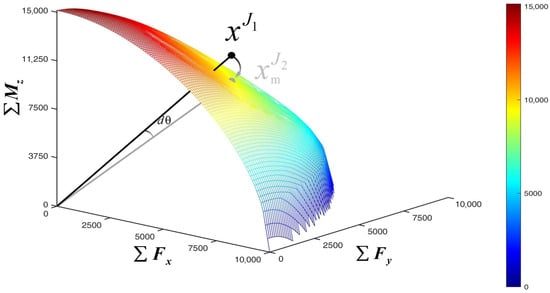

In each control cycle, the vehicle body controller exports a target generalized force vector in generalized force space to track the driver’s intent. Since the tire friction circle constraint and actuator saturation constraint form a convex feasible region, solving the generalized force boundary is equivalent to solving a convex optimization problem. Firstly, the generalized force delivered by the body controller is normalized to the desired unit vector within the generalized force space. Subsequently, a boundary point is sought along this direction within the convex constraints, thereby obtaining the maximum feasible generalized force vector permitted under the current desired conditions. Based on this, the objective function is formulated to minimize the cost in Equation (13).

where is the weight of the vehicle longitudinal resultant force in the generalized demand force; is the weight of the vehicle lateral resultant force in the generalized demand force; and is the weight of the vehicle yaw moment in the generalized demand moment. Their definitions can be expressed as follows:

where is the Euclidean norm of a vector.

From Equations (1) and (13), it is seen that Equation (13) can be rewritten as an affine combination of lateral and longitudinal forces acting on each wheel’s tire in each control cycle. Therefore, when formulating the constraints for this optimization problem, this article directly employs tire force to describe the inequality constraints, as detailed below.

The optimal solution to the objective function defined by Equation (13) under the constraints of Equation (15) is . Further, solving the boundary values of the generalized forces and moment can be expressed as:

where denotes the sign function.

Based on generalized force boundaries derived from online real-time calculations, the system performs single dimensional comparisons and corrections for demand forces: once demand in any dimension exceeds its corresponding boundary, only that dimension is corrected while others remain unaffected. The schematic diagram of the correction process is illustrated in Figure 6: the demand generalized force vector is , with the envelope surface representing the generalized force boundary. The corrected generalized force vector after generalized force boundary constraints is . The difference between the two in generalized force space is represented by a minimal quantity , satisfying . As boundary values continuously update based on actuator fault severity and are embedded as hard constraints within the upper-level controller, the generalized outputs at any given moment are strictly confined within the feasible set of the lower-level system, preventing the tire force optimization allocation process from introducing penalty terms through constraint relaxation, thereby reducing control accuracy.

Figure 6.

Generalized force correction process. Colors closer to red indicate a larger available yaw moment.

3.2. Tire Force Allocation and Control

The execution of the vehicle’s target generalized forces relies on the vehicle’s underlying actuators. The tire force distribution module requires optimization to determine target values for the hub motors and steering powertrain, continuously adjusting longitudinal and lateral tire forces to ensure the vehicle follows the driver’s intent under all operating conditions.

Therefore, a performance metric is established as , fully coordinating the remaining margin of all tire forces across the vehicle to maintain stable driving capability under extreme conditions. The objective function is to minimize Equation (17).

where are weighted coefficients for tire load rate.

Based on the concept of the tire friction circle, the boundary of the tire resultant force vector is determined by the product of the road surface friction coefficient and the vertical load of each wheel. Simultaneously considering the actuator saturation constraint caused by steering powertrain degradation coefficient, the calculation method for the weighted coefficient of the tire load ratio for each wheel is defined as follows:

By introducing the equality constraints described in Equation (1) and the inequality constraints described in Equation (15), and combining them with the objective function described in Equation (17), a nonlinear programming problem, as shown in Equation (19), is formulated to achieve the optimal allocation of tire forces. SQP offers reliable convergence while robustly handling boundary constraints. Moreover, existing studies show that, when combined with algorithmic differentiation and code generation, sparse QP/MQP solvers, inexpensive approximate Hessians, problem simplification, and limited-iteration warm starts, SQP-based controllers can satisfy real-time constraints on automotive ECUs [41]. Therefore, SQP is selected to solve for the optimal tire force.

where is a vector containing the target tire forces expressed in the vehicle coordinate system, and represent the equality and inequality constraints associated with the tire-force allocation problem, respectively.

By applying the coordinate transformation in Equation (6) in the reverse direction for each wheel, the tire-frame force vector is obtained.

The target torque of the hub motor is determined by solving the following wheel rotation dynamics equation:

where denotes the moment of inertia of the wheel, and represents the angular acceleration of the wheel.

Based on the Dugoff tire model [42], the tire side inverse model is derived, leading to the following equation for the target value of the tire slip angles :

where is the longitudinal tire stiffness; .

The road wheel angles are calculated based on the vehicle body model definition shown in Figure 2:

4. Simulation Results and Analysis

To validate the feasibility of the proposed controller, a CarSim 2019 and Simulink 2021B Co-simulation environment was established. Two fault scenarios—diagonal wheel and unilateral wheel steering failures—were selected to perform the lane change maneuver (LCM). Based on recent studies [43] and Chinese-market specifications for compact electric vehicles, the vehicle parameters used in the simulations are chosen as listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Simulation parameters.

In this simulation setup, the controller weights are tuned based on the principle that a larger Q/R gives tighter tracking, whereas a larger R yields smoother and more conservative control actions. Tuning proceeds in three steps. First, we tune the longitudinal motion using pure acceleration/braking maneuvers, where lateral–yaw coupling can be neglected. Next, we adjust the weight on lateral-velocity tracking, since lateral speed constrains the feasible yaw-moment range. Finally, we refine the yaw-rate response.

Table 2 summarizes the proposed method and the comparison method mentioned in this paper. In the comparison method, the generalized force/moment demand is computed without considering the shrinkage of the generalized force/moment feasible domain. At the allocation layer, the comparison method penalizes the tangential force of each tire using the reciprocal of the product of the road adhesion coefficient and the corresponding vertical load, while enforcing the tire friction-circle constraint only on a per-wheel basis. In contrast, the proposed method incorporates the fault information to update both the admissible vehicle force/torque range and each tire’s allowable force range, so that the optimization is carried out within a fault-aware feasible region. This enables the allocator to maintain feasibility and safety even when the steering or driving actuators are degraded.

Table 2.

Descriptions of the proposed method and the comparison method.

4.1. Diagonal Steer Wheel FTC Under High-Friction Road Conditions

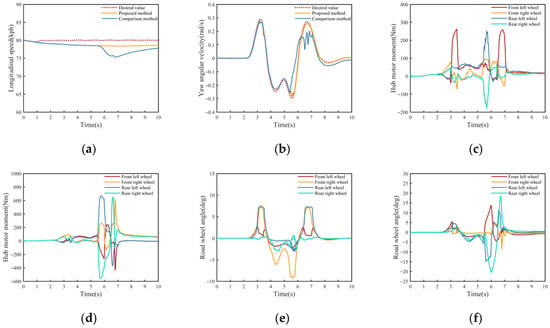

The diagonal wheels with steering failure are the front left wheel and the rear right wheel. The steering powertrain fault is triggered 2 s after the simulation begins. After 2 s, the output torque of the steering powertrain begins to attenuate. Specifically, the maximum output torque of the left front wheel is reduced to 90 Nm, while that of the right rear wheel is reduced to 70 Nm. The target longitudinal vehicle speed in the simulation condition is 80 kph. The road friction coefficient is 0.8.

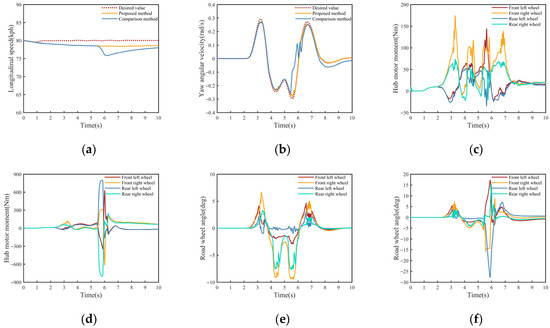

Figure 7 shows the vehicle motion states and actuator status of the proposed method and the comparison method. As illustrated in Figure 7a, a comparison of the results reveals significant variations in longitudinal vehicle speed. The proposed method demonstrates that the actual longitudinal speed more closely aligns with the target speed, with lower speed fluctuation amplitude compared to the comparison method. As illustrated in Figure 7b, a comparison of the results reveals significant disparities in yaw rate. The proposed method effectively tracks the desired value, exhibiting superior tracking performance and faster oscillation decay, particularly during the time-domain response process between 6 and 7 s. The analysis of the actuator state responses shown in Figure 7c–f indicates that this comparison method overcomes the abnormal angular response of the faulty steering wheel by utilizing the hub motor torque output, where the hub motor output torque reaches 600 Nm. In contrast, the proposed method restricts the faulty wheel’s angle within the normal angular response range, thereby avoiding significant conflicts between wheel angle control and differential steering. Consequently, it has been determined that a lower hub motor torque is sufficient to ensure yaw rate tracking, achieving better longitudinal speed tracking performance.

Figure 7.

Some results of the diagonal road wheel failure condition. (a) Longitudinal velocity. (b) Yaw angle rate. (c) Hub motor torques in the proposed method. (d) Hub motor torques in the comparison method. (e) Road wheel angles in the proposed method. (f) Road wheel angles in the comparison method.

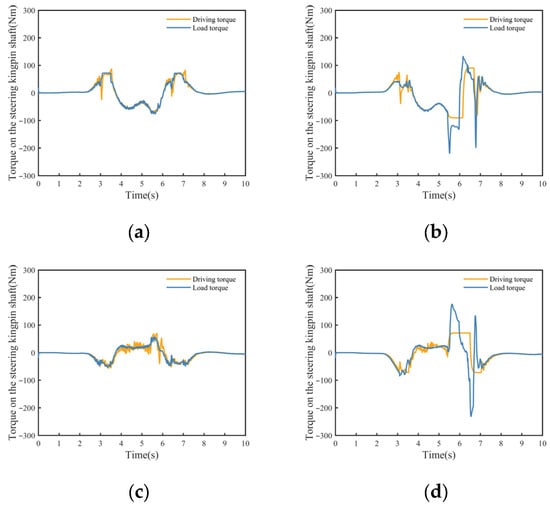

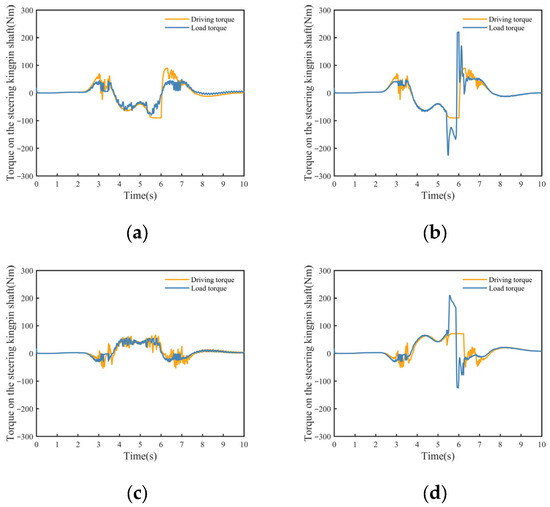

To analyze the differences in steering angle responses between the two methods, a comparison is made of the steering drive torque and steering load torque of the failed wheels in Figure 8. The proposed method considers the steering fault power output capability during steering angle allocation, ensuring that steering loads during the faulted wheel’s steering angle tracking remain within the steering powertrain’s maximum output torque range. Conversely, the comparison method allocates target steering angles without considering steering fault information. Consequently, the steering loads exceed the steering powertrain’s output capacity, leading to steering angle instability.

Figure 8.

Steering kingpin shaft torques in the diagonal road wheel failure condition. (a) Front left wheel kingpin torques in the proposed method. (b) Front left wheel kingpin torques in the comparison method. (c) Rear right wheel kingpin torques in the proposed method. (d) Rear right wheel kingpin torques in the comparison method.

4.2. Unilateral Steer Wheel FTC Under High-Friction Road Conditions

The steering fault is applied to the wheels on the same side, namely the front left and rear left wheels. The fault is injected 2 s after startup: the maximum output torque limit for the left front wheel steering motor is 90 Nm, and for the left rear wheel, it is 70 Nm; the target operating speed is 80 km/h. Road friction coefficient is 0.8.

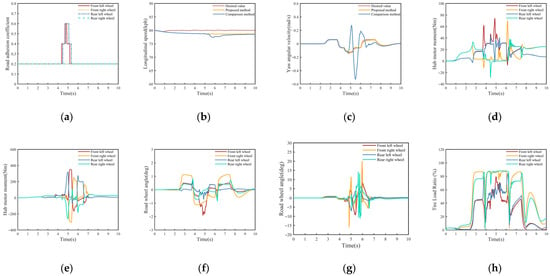

Unilateral steering wheel failures cause imbalance in the available tire forces on the vehicle’s left and right sides, resulting in greater control difficulty compared to diagonal failure scenarios. As shown in Figure 9, in the comparison method, the hub motor outputs a torque of approximately 800 Nm within a 5 to 6 s time frame to adjust the yaw motion; however, this exacerbates the loss of control over the steering angle of the faulty wheel. The fundamental issue appears to be the failure of the approach to account for the simultaneous generation of steering load in the faulty wheel by the hub motor’s torque output. This results in conflicts between torque vectoring control and steering angle control. In contrast, the proposed method quantifies the degradation of the steering actuator to the boundaries of available tire longitudinal and lateral forces. The system has been engineered to limit both the longitudinal force and the tire sideslip angle of the defective road wheel during the process of control allocation. Figure 10 illustrates that road angle tracking is achieved within the remaining capability of the degraded steering actuator under the premise of limiting the load on the faulty road wheel. The remaining vehicle attitude control tasks are accomplished through the tire forces of the healthy wheels. Consequently, even in the event of a steering actuator failure, the tracking of the target vehicle’s state remains a viable undertaking through the concerted output of multiple actuators.

Figure 9.

Some results of the unilateral road wheel failure condition. (a) Longitudinal velocity. (b) Yaw angle rate. (c) Hub motor torques in the proposed method. (d) Hub motor torques in the comparison method. (e) Road wheel angles in the proposed method. (f) Road wheel angles in the comparison method.

Figure 10.

Steering kingpin shaft torques in the unilateral road wheel failure condition. (a) Front left wheel kingpin torques in the proposed method. (b) Front left wheel kingpin torques in the comparison method. (c) Rear left wheel kingpin torques in the proposed method. (d) Rear left wheel kingpin torques in the comparison method.

4.3. Unilateral Steer Wheel FTC Under Split-Friction Road Conditions

The steering fault is applied to the wheels on the same side, namely the front left and rear left wheels. The fault is injected 2 s after startup: the maximum output torque limit for the left front wheel steering motor is 60 Nm, and for the left rear wheel it is 48 Nm; the target operating speed is 80 km/h. The split-friction road consists of a high-friction side with μ = 0.6 and a low-friction side with μ = 0.2. In this scenario, the lane change is configured as a lane change from the low-friction surface to the high-friction surface.

Figure 11a shows the road adhesion coefficient under each wheel. All four wheels initially run on the low-friction surface with μ = 0.2. During the lane change, the left wheels move onto the high-friction surface with μ = 0.6, while the right wheels remain on μ = 0.2. Figure 11b shows the longitudinal speed response. Compared with the proposed method, the comparison method exhibits a more pronounced speed dip around 5–6 s. Figure 11c presents the yaw-rate response. When the faulty wheel encounters the change in road friction, the comparison method exhibits noticeable oscillations and a large deviation from the reference, whereas the proposed method remains close to the desired value. Figure 11d,e compare the hub-motor torques under the two methods. Figure 11f,g compare road-wheel steering angles under the two methods. With the proposed method, the actuator redundancy is utilized more effectively while avoiding large torques and wheel angles. Figure 11h shows the tire load ratio under the proposed method. The right front and right rear wheels reach peak load ratios of about 80~90%, indicating that their available tire forces are effectively utilized. In contrast, the load ratios of the left front and left rear wheels remain at more moderate levels, reflecting that the controller appropriately constrains tire load ratio on the faulty side when the steering actuator degradation is taken into account.

Figure 11.

Some results of the diagonal road wheel failure condition. (a) Road surface adhesion coefficient. (b) Longitudinal velocity. (c) Yaw angle rate. (d) Hub motor torques in the proposed method. (e) Hub motor torques in the comparison method. (f) Road wheel angles in the proposed method. (g) Road wheel angles in the comparison method. (h) Tire load ratio in the proposed method.

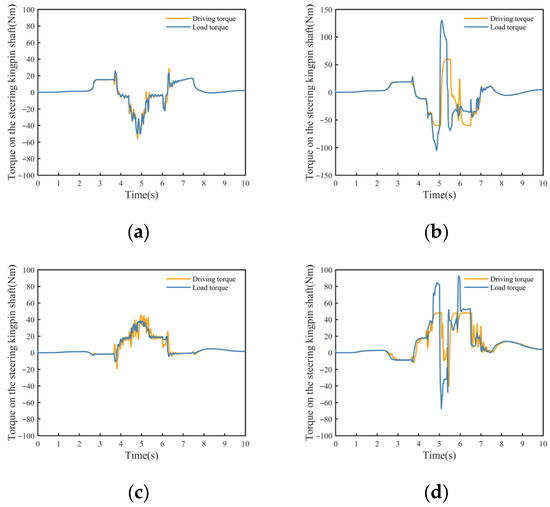

The comparison is made of steering kingpin shaft torques of the failed wheels in Figure 12. In the proposed method, the steering-angle allocation accounts for the limited output capability of the degraded steering actuators. As a result, when the split-friction transition causes a sudden change in steering load, the steering driving torque and load torque of the fault wheel remain relatively bounded. By contrast, the comparison method does not properly coordinate the target torque and steering angle of the faulty wheel around the friction transition, so the faulty wheel cannot effectively cope with the sudden change in steering load.

Figure 12.

Steering kingpin shaft torques. (a) Front left wheel kingpin torques in the proposed method. (b) Front left wheel kingpin torques in the comparison method. (c) Rear left wheel kingpin torques in the proposed method. (d) Rear left wheel kingpin torques in the comparison method.

5. Conclusions

The motion control problem of DCS under the degradation conditions of ISS is investigated. A fault tolerant motion control method for the chassis system is established by integrating the residual capability of the failed steering powertrain with redundant outputs from other actuators. Based on the dynamics of the ISS, an analytical mapping relationship is derived between steering powertrain degradation coefficients and the feasible domain of tire force contraction. Furthermore, MPC is designed to solve for the demand generalized force/torque initially. Within a unit control cycle, the generalized feasible boundary is searched based on the direction of the demand generalized force vector while constraining the vehicle’s desired generalized force/torque for the current cycle, thereby achieving motion state regulation. For tire force allocation, the degradation coefficient is incorporated into the objective function. Combined with the feasible region for tire force contraction, SQP is employed to solve the target tire forces. Simulation validation for diagonal wheel steering failures and same-side wheel steering failures demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Future work will incorporate factors such as tire surface temperature and wear into the aligning-torque model to broaden its applicability, and will evaluate the control strategy through vehicle-in-the-loop testing on a real vehicle. Moreover, prescribed finite-time control can be combined with the proposed optimization-based fault-tolerant control and extended to multi-vehicle platooning in a multi-agent framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.J. and B.J.; methodology, B.J. and Y.H.; software, B.J.; validation, B.J., Y.H. and Q.Z.; data analysis, B.J. and H.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, B.J. and Q.Z.; writing—review and editing, L.J. and H.Y.; visualization, R.L.; supervision, L.J. and B.J.; funding acquisition, L.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Major Project of Guangxi, grant number guikeAA24206032.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Haixia Yi and Ronghua Li were employed by the company Guangzhou Automobile Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DCS | Distributed Chassis System |

| MPC | Model Predictive Controller |

| SQP | Sequential Quadratic Programming |

| FTC | Fault-tolerant Control |

| IAWM | Integrated Autonomous Wheel Module |

| ISS | Independent Steering System |

| LCM | Lane Change Maneuver |

References

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Jin, L.; Yin, G. Key Technologies and Research Progress of Brake-by-Wire System for Intelligent Electric Vehicles. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 60, 339–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Zhang, Q.; Tian, D.; Jin, L.; Li, J.; Xiao, F. Pre-Stability Control for In-Wheel-Motor-Driven Electric Vehicles with Dynamic State Prediction. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 4541–4554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Feng, J.; Fang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Yin, G.; Mao, X.; Wu, J.; Wang, F. An Energy-Oriented Torque-Vector Control Framework for Distributed Drive Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Transport. Electrific. 2023, 9, 4014–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Wang, F.; Feng, J.; Zhao, M.; Fang, R.; Pi, D.; Yin, G. A Hierarchical Control of Independently Driven Electric Vehicles Considering Handling Stability and Energy Conservation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 738–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, W.; Wang, C.; Li, L. Stability Control of In-Wheel Motor Electric Vehicles under Extreme Conditions. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2019, 41, 2838–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosato, L.; Tian, K.; Shum, H.P.H.; Ho, E.S.L.; Wang, Y.; Wei, C. Social Interaction-aware Dynamical Models and Decision-making for Autonomous Vehicles. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 6, 2300575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Deng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Cao, K.; Chu, D.; Zhang, B.; Cao, D. Socially Game-Theoretic Lane-Change for Autonomous Heavy Vehicle Based on Asymmetric Driving Aggressiveness. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 17005–17018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavifar, H.; Wei, C.; Taghavifar, L. Socially Intelligent Reinforcement Learning for Optimal Automated Vehicle Control in Traffic Scenarios. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhang, F.; Dong, H.; Liu, Y.; Yin, G. An Adaptive Fault-Tolerant EKF for Vehicle State Estimation with Partial Missing Measurements. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2021, 26, 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liang, J.; Yin, G.; Feng, J.; Wang, F.; Xu, L. Torque Vector Compensation Strategy with Adaptive Model Predictive Control Considering Steering Actuator Fault. In Proceedings of the 2022 6th CAA International Conference on Vehicular Control and Intelligence (CVCI), Nanjing, China, 28–30 October 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Nor Shah, M.B.; Husain, A.R.; Aysan, H.; Punnekkat, S.; Dobrin, R.; Bender, F.A. Error Handling Algorithm and Probabilistic Analysis under Fault for CAN-Based Steer-by-Wire System. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat. 2016, 12, 1017–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Du, C.; Wang, Y.; Pi, D. Intelligent Vehicle Driving Decisions and Longitudinal–Lateral Trajectory Planning Considering Road Surface State Mutation. Actuators 2025, 14, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, Y. Camera That Takes Pictures of Aircraft and Ground Vehicle Tires Can Save Lives. J. Electron. Imaging 2013, 22, 41104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ni, J.; Tian, H.; Wu, W.; Hu, J. Integrated Robust Dynamics Control of All-Wheel-Independently-Actuated Unmanned Ground Vehicle in Diagonal Steering. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 164, 108263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Qiu, N.; Tian, D.; Zhang, Q.; Teng, F.; Jin, B.; Xiao, F. MPC-Based Path Tracking Strategy for 4WID&4WIS Vehicles Using B-Spline Approximation and State-Dependent Reference. Control Eng. Pract. 2025, 165, 106546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekih, A.; Devariste, D. A Fault-Tolerant Steering Control Design for Automatic Path Tracking in Autonomous Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2013 American Control Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 17–19 June 2013; pp. 5146–5151. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Naghdy, F.; Du, H. Delta Operator-Based Model Predictive Control with Fault Compensation for Steer-by-Wire Systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2020, 50, 2257–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Luo, Y.; Li, K. Robust H∞ Fault-Tolerant Lateral Control of Four-Wheel-Steering Autonomous Vehicles. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2020, 21, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Tian, Y.; Ji, X.; Qiu, B. Fault-Tolerant Controller Design for Path Following of the Autonomous Vehicle under the Faults in Braking Actuators. IEEE Trans. Transport. Electrific. 2021, 7, 2530–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakov, A. Nonlinear Feedback Design for Fixed-Time Stabilization of Linear Control Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2012, 57, 2106–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, B.; Han, Q.-L. Prescribed Finite-Time Consensus Tracking for Multiagent Systems with Nonholonomic Chained-Form Dynamics. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2019, 64, 1686–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, G.; Jing, H. Integrated Path-Following and Fault-Tolerant Control for Four-Wheel Independent-Driving Electric Vehicles. Automot. Innov. 2022, 5, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Liang, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Wong, P.K. Adaptive Event-Based Robust Passive Fault Tolerant Control for Nonlinear Lateral Stability of Autonomous Electric Vehicles with Asynchronous Constraints. ISA Trans. 2022, 127, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Du, H.; Li, W. Fault-tolerant control of electric vehicles with in-wheel motors using actuator-grouping sliding mode controllers. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2016, 72–73, 462–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Qin, Y.; Cao, H.; Song, X.; Jiang, K.; Rath, J.J.; Wei, C. Lane keeping of autonomous vehicles based on differential steering with adaptive multivariable super-twisting control. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 125, 330–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khelladi, F.; Boudali, M.; Orjuela, R.; Cassaro, M.; Basset, M.; Roos, C. An Emergency Hierarchical Guidance Control Strategy for Autonomous Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 4319–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Cai, Y.; Chen, L.; Xu, X.; Sun, X. Trajectory tracking control of steer-by-wire autonomous ground vehicle considering the complete failure of vehicle steering motor. Simul. Modell. Pract. Theory 2021, 109, 102235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wei, C.; Tian, H.; Wang, W.; Jiang, C. Fault-Tolerant Control for Path-Following of Independently Actuated Autonomous Vehicles Using Tube-Based Model Predictive Control. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 20282–20297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Xie, H.; Gao, B.; Lu, X.; Chen, H. A Centralized Fault Prevention Method for Vehicle Longitudinal-Lateral-Vertical Control Considering Motor Thermal Protection. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 6979–6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, C.; Liu, C.; Zheng, H.; Liu, J. Fault Tolerant Control against Actuator Failures of 4WID/4WIS Electric Vehicles; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S.C.; Song, T.J.; Kim, M.J.; Oh, K.S. Adaptive Model Predictive Fault-Tolerant Control for Four-Wheel Independent Steering Vehicles with Sensitivity Estimation. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2023, 24, 829–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, N.; Wu, G.; Li, Z.; Ding, H.; Jiang, C. Active Fault-Tolerant Control of a Four-Wheel Independent Steering System Based on the Multi-Agent Approach. Electronics 2024, 13, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, D.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Hong, J. Advanced Post-impact Safety and Stability Control for Electric Vehicles. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 16, 1753–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Jin, L. Modeling and Simulation Studies on Differential Drive Assisted Steering for EV with Four-Wheel-Independent-Drive. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference, Harbin, China, 3–5 September 2008; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wada, N.; Fujii, K.; Saeki, M. Reconfigurable Fault-Tolerant Controller Synthesis for a Steer-by-Wire Vehicle Using Independently Driven Wheels. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2013, 51, 1438–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Naghdy, F.; Du, H.; Huang, H. Fault Tolerant Steer-by-Wire Systems: An Overview. Annu. Rev. Control 2019, 47, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ji, X.; Zheng, H. Analysis of Vehicle Static Steering Torque Based on Tire–Road Contact Patch Sliding Model and Variable Transmission Ratio. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2016, 8, 1687814016668765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacejka, H. Tire and Vehicle Dynamics, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. Model Predictive Control System Design and Implementation Using MATLAB; Advances in Industrial Control; Springer: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, E.; Hattori, Y.; Muragishi, Y.; Koibuchi, K. Vehicle Dynamics Integrated Control for Four-Wheel-Distributed Steering and Four-Wheel-Distributed Traction/Braking Systems. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2006, 44, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirynen, R.; Cairano, S.D. Sequential Quadratic Programming Algorithm for Real-Time Mixed-Integer Nonlinear MPC. In Proceedings of the 2021 60th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Online, 14 December 2021; IEEE: Austin, TX, USA, 2021; pp. 993–999. [Google Scholar]

- Dugoff, H.; Fancher, P.S.; Segel, L. An Analysis of Tire Traction Properties and Their Influence on Vehicle Dynamic Performance; SAE Transactions: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1970; p. 700377. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, A.; Tian, G. Unified Fault-Tolerant Control and Adaptive Velocity Planning for 4WID-4WIS Vehicles under Multi-Fault Scenarios. Actuators 2024, 13, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).