Abstract

Soft robotics represents a rapidly advancing and significant subfield within modern robotics. However, existing soft actuators often face challenges including unwanted deformation modes, limited functional diversity, and a lack of versatility. This paper presents a four-chamber multimodal soft actuator with a centrally symmetric layout and independent pneumatic control. While building on existing multi-chamber concepts, the design incorporates a cruciform constraint layer and inter-chamber gaps to improve directional bending and reduce passive chamber deformation. An empirical model based on the vector superposition of single- and dual-chamber inflations is developed to describe the bending behavior. Experimental results show that the actuator can achieve omnidirectional bending with errors below 5% compared to model predictions. To demonstrate versatility, the actuator is implemented in two distinct applications: a three-finger soft gripper that can grasp objects of various shapes and perform in-hand twisting maneuvers, and a steerable crawling robot that mimics inchworm locomotion. These results highlight the actuator’s potential as a reusable and adaptable driving unit for diverse soft robotic tasks.

1. Introduction

Conventional robots, fabricated from rigid metallic components, exhibit rapid response and high load-bearing capacity, yet suffer from high cost and limited adaptability. In contrast, soft robots—characterized by high compliance, exceptional environmental adaptability, safe human–robot interaction, and low cost—have attracted intense attention and have developed rapidly. Notable advances have been achieved in bio-inspired robotics, soft grippers, and flexible actuators [1,2,3].

Soft robotic actuation modalities primarily include fluidic (hydraulic and pneumatic) actuation, shape-memory-alloy (SMA) actuation, tendon-driven actuation, and electroactive-polymer (EAP) actuation [4]. Among these, pneumatic actuation has obtained the widest research and application owing to its lightweight construction, rapid response, and eco-friendly operation [5,6]. In particular, the pneumatic-network (PneuNet) design proposed by Harvard University in 2011 [7]—whereby pressurized chambers generate bending, elongation, or torsion—has been widely referenced [8,9]. To overcome limited deformation in silicone-based actuators, Bobak et al. [10] introduced inter-chamber gaps within PneuNets in 2013, significantly increasing both deformation amplitude and rate; this strategy is now prevalent in soft-gripper design [11,12]. Concurrent research efforts have focused on overcoming other key limitations of soft actuators. A critical challenge remains their limited output force [13,14], which has been addressed through novel fabrication methods like core-insert casting [15] and the strategic integration of rigid components [16,17]. Bio-inspiration has also proven to be a highly effective design paradigm [18,19,20,21], leading to grippers inspired by octopus tentacles [22], coiling actuators mimicking vine tendrils [23], and crawling robots that imitate inchworm locomotion [24]. Furthermore, functional diversity has been enhanced by hybrid systems, such as integrating granular-jamming layers for variable stiffness [25]. Despite these advances, a significant gap remains in achieving actuators that combine high dexterity, simple control, and tractable modeling.

A prominent research direction involves developing actuators with multiple independent chambers to achieve complex, multi-degree-of-freedom motions [26,27]. However, many designs in this area face inherent limitations. The range of bending deformation that can be achieved through the structural design of connecting multiple chambers [28] is limited. Actuators with three chambers arranged in a triangle [29,30] can bend in 3D space, but their bending directions are constrained to the planes defined by their chamber geometry, falling short of genuine omnidirectional motion.

Meanwhile, a significant challenge persists in the accurate and efficient modeling of these actuators. The hyperelastic nature of silicone, large-strain geometric nonlinearities, viscoelastic hysteresis, and coupling between adjacent chambers make deriving analytical models from first principles exceedingly difficult. Consequently, high-fidelity finite element analysis (FEA) is often required for deformation prediction, which is computationally intensive and impractical for real-time control or rapid design iteration.

These challenges often force a trade-off between an actuator’s dexterity, control simplicity, and modeling tractability. As summarized in Table 1, while existing multi-chamber actuators have made significant progress, they often excel in one or two aspects at the expense of others. For instance, some achieve omnidirectional bending but require complex control schemes or intricate fabrication, while others prioritize simplicity but offer limited workspace or face significant modeling hurdles.

Table 1.

Comparative Analysis of Multi-Chamber Soft Actuators.

While multi-chamber pneumatic actuators have been explored previously [26,29,30], their performance is often limited by structural coupling, modeling complexity, or control challenges. This work presents an incremental yet integrated approach that combines a cruciform internal constraint with inter-chamber gaps to mitigate these issues. The primary contributions of this study are threefold: (1) a structurally enhanced four-chamber design that improves directional bending consistency and reduces passive chamber deformation; (2) a simplified empirical model based on vector superposition, facilitating efficient motion planning while reducing reliance on computationally intensive simulations; and (3) experimental validation through two functionally distinct applications—a dexterous soft gripper and a steerable crawling robot—demonstrating the actuator’s versatility as a multimodal driving unit.

2. Design of Four-Chamber Multimodal Actuator

2.1. Structure

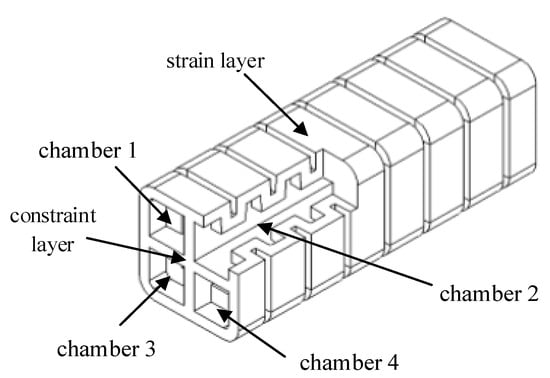

Most pneumatically actuated silicone soft actuators adopt the PneuNet topology, in which the strain layer undergoes larger deformation than the constraint layer upon pressurization, yielding unilateral bending. Gaps introduced into the strain layer further amplify both deformation magnitude and speed. Common chamber shapes include rectangular, circular, semi-circular, trapezoidal, and irregular shapes. The proposed four-chamber multimodal actuator (Figure 1) consists of a rectangular prism with a rectangular cross-section. The outer walls constitute the strain layer, and gaps are placed between adjacent chambers. A cruciform constraint layer embedded at the centroid partitions the internal volume into four independent chambers.

Figure 1.

Structural design of the four-chamber multimodal soft actuator.

Owing to the pneumatic isolation between the four chambers, the pressure within each can be controlled independently. By modulating the pressure applied to individual chambers, the actuator can generate a variety of spatial deformations. As illustrated in Figure 2a, supplying high pressure to chambers 1 and 2 while venting chambers 3 and 4 results in downward bending. Analogously, upward, leftward, and rightward bending are realized by pressurizing the corresponding chamber pairs. More generally, by assigning distinct pressures to all four chambers, the actuator can bend in any direction within 3-D space (Figure 2b). The geometric parameters are summarized in Table 2, and these parameters were used for both simulation and physical prototyping.

Figure 2.

Bending deformation modes of the actuator under different pressure inputs: (a) Bending in four principal directions (up, down, left, right) by pressurizing two opposing chambers; (b) Omnidirectional bending in 3D space achieved by independent pressure control in all four chambers.

Table 2.

Geometric parameters of the four-chamber soft actuator.

2.2. Finite-Element Analysis

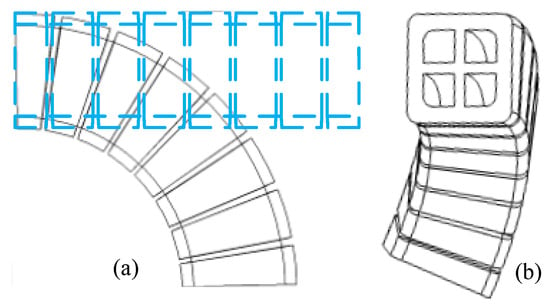

To validate the omnidirectional bending capability of the proposed actuator, we performed a finite-element analysis using ANSYS WorkBench (version 19.0). The 3-D model created in SolidWorks (version 2024) was imported into the static-structural module, where the inlet was fixed and internal pressures were applied. The Yeoh hyperelastic model with C10 = 0.16 MPa and C20 = 0.02 MPa was employed to characterize the silicone. These two coefficients were obtained from uniaxial tensile test [31] as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Material coefficient acquisition: (a) Uniaxial tensile test; (b) Data fitting (C10 = 0.16, C20 = 0.02).

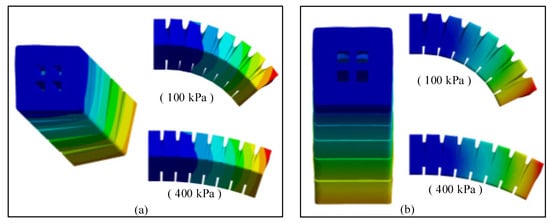

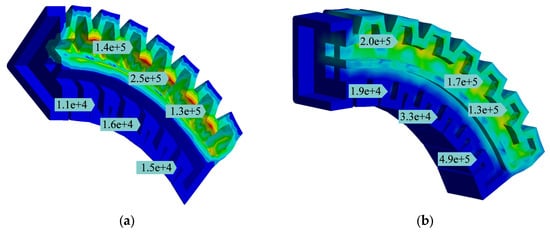

Single-chamber actuation was first investigated. With chamber 1 pressurized to P1 and chambers 2–4 vented (P2 = P3 = P4 = 0), the actuator bent right-downward at φ = 45°. The bending angle monotonically increased with pressure, reaching 50° at P1 = 100 kPa (Figure 4a). Dual-chamber actuation was subsequently examined. When chambers 1 and 2 were equally pressurized (P1 = P2) and chambers 3 and 4 vented, downward bending at φ = 90° was observed. Again, the bending angle grew with pressure, attaining 66° at P1 = P2 = 100 kPa (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Simulation Result: (a) Single-chamber Inflation; (b) Dual-chamber Inflated.

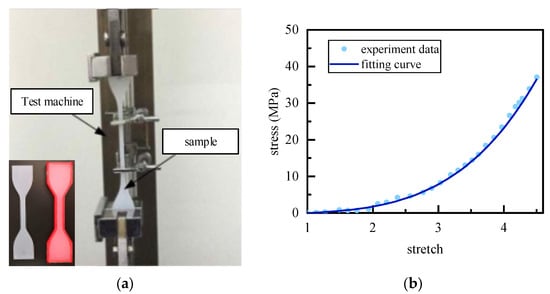

To quantitatively assess the decoupling effect afforded by the inter-chamber gaps, the stress distribution within both pressurized and passive chambers were analyzed. Under a supply pressure of 100 kPa, the von Mises stress was examined. For single-chamber inflation, the maximum stress in the active chamber (approx. 250 kPa) was localized at the connection between the air channel and the PneuNet unit, with an average wall stress of about 175 kPa. Conversely, the stress in the non-pressurized chambers (2, 3, and 4) was markedly lower, averaging only 14.5 kPa (see stress nephogram in Figure 5a). For dual-chamber inflation, the average wall stress in the active chambers was approximately 169 kPa, while the stress in the opposite, passive chambers remained significantly lower at about 34 kPa (Figure 5b). This order-of-magnitude difference in stress levels between active and passive chambers provides clear quantitative evidence that the inter-chamber gap design effectively minimizes undesired mechanical coupling and passive deformation, validating a key feature of our actuator’s structural configuration.

Figure 5.

Stress nephogram: (a) Single-chamber Inflation; (b) Dual-chamber Inflated.

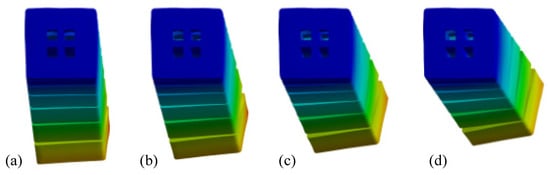

Finally, arbitrary bending was validated by assigning distinct pressures to all four chambers. One representative scenario (P1 = 100 kPa, P4 = 0, with P2 and P3 as annotated in Figure 6) yielded continuous bending between φ = 45° and 90°. Collectively, these results demonstrate that any 360° bending trajectory can be realized by appropriate pressure combinations, while the bending magnitude is continuously tunable via pressure modulation.

Figure 6.

Four-chamber Inflation Simulation (P1 = 100 kPa, P4 = 0): (a) P2 = 60, P3 = 40 kPa; (b) P2 = 70, P3 = 30 kPa; (c) P2 = 80, P3 = 20 kPa; (d) P2 = 90, P3 = 10 kPa.

3. Theoretical Model of Bending Deformation

The Yeoh model was selected for its mathematical simplicity, rapid convergence, and proven utility in modeling moderate to large deformations of silicone elastomers, making it suitable for deriving an analytical moment-balance relationship. While recent comparative studies [31] indicate that the Ogden model may offer higher accuracy over the full range of failure strains, the Yeoh model provides a suitable balance between simplicity and accuracy for the bounded deformation range considered in this work. Its resulting predictions are subsequently calibrated and corrected via an empirically determined influence coefficient.

The Yeoh model is selected as the constitutive model for the silicone material in this study due to its rapid convergence and high accuracy under large deformation. By establishing moment equilibrium between the driving moment generated by pneumatic pressure and the resisting moment arising from silicone deformation, the interaction between bending deformation of a single PneuNet chamber and the internal pressure is analyzed, thereby deriving the overall deformation angle of the actuator.

Assuming that silicone rubber material is incompressible and does not deform in the width direction, based on the classic binomial parameter form of the Yeoh model, the strain energy density function model is represented as Equation (1) and the stress–stretch relation is expressed as Equation (2):

where W is the strain-energy density, λ1 is the principal stretch ratios, C10 and C20 are material coefficients obtained from uniaxial tensile test (Figure 3).

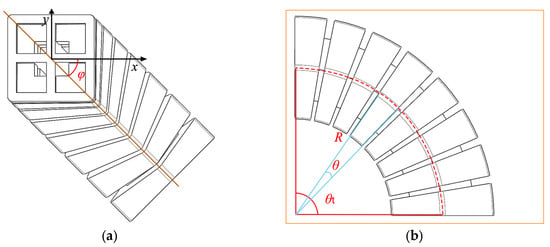

The four independent chambers of the multimodal actuator enable spatially arbitrary bending. As shown in Figure 7, define the bending direction φ as the angle between the bending plane and the transverse axis, the bending angle θₜ as the central angle. The objective of this analysis is to derive an accurate yet computationally efficient pressure–deflection mapping. It allows for the direct calculation of the required pressure inputs (p1, p2, p3, p4) to achieve a desired bending angle (θt) and direction (φ) in a single step, thereby facilitating precise motion planning and trajectory control.

Figure 7.

Bending Direction and Angle: (a) Front view; (b) Side view.

Prior to theoretical analysis, the following reasonable assumptions are made:

- (1)

- Due to the presence of gaps between chambers, the compression deformation of non-inflated chambers during bending is negligible. Consequently, the silicone reaction force from these chambers will be neglected.

- (2)

- The bending deformation of the soft actuator is assumed to be unaffected by its own weight, and the silicone material is treated as incompressible.

- (3)

- The work performed by the internal air pressure within the chambers is entirely converted into stored potential energy of the actuator.

- (4)

- Throughout the deformation process of the soft actuator, the silicone body undergoes uniform deformation. Thus, the central angle corresponding to each PneuNet unit is considered to maintain an identical value. Therefore, the overall central angle of the soft actuator’s bending deformation can be regarded as the sum of the individual bending central angles of all PneuNet units. The overall angle can be expressed aswhere n denotes the effective PneuNet unit count; owing to the connector in the first unit, n = 7 is used for the present actuator.

3.1. Bending with Two Adjacent Chambers Inflated

First, the bending deformation generated when two chambers on the same side are inflated is analyzed. Assume chambers 1 and 2 are connected to the same pressure source, while chambers 3 and 4 are vented to atmosphere. Under these conditions, chambers 1 and 2 expand and deform, causing the entire soft actuator to bend toward chambers 3 and 4, i.e., φ = −90°.

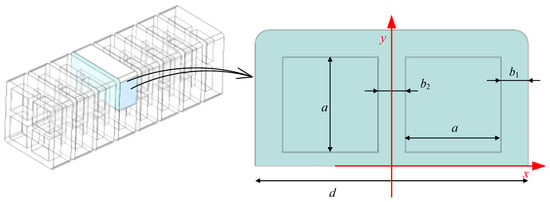

A force analysis is performed on a single PneuNet unit of actuating chambers 1 and 2. The theoretical model is based on a simplified geometry of the PneuNet unit cross-section (Figure 8). The primary simplifications are the omission of air channels and filets; the assumption of uniform wall thickness; and, for the purpose of deriving the driving moment, the treatment of the constraint layer as rigid. Based on this simplified geometry and by considering the elongation along the centerline as the axial elongation, the principal stretch ratio is expressed as Equation (5):

where l is the unit thickness, l = 6.5 mm.

Figure 8.

Cross-sectional view of a single PneuNet unit for theoretical modeling.

The compressed gas acts on the front and rear sides. The driving torque generated by the pressure is

The moment generated by the deformation of the silicone on the top surface of the unit on the x-axis is

The moment generated on the x-axis by the deformation of silicone on the side of the unit is

The moment generated by the deformation of silicone on the x-axis at the front and back of the unit is

Considering the non-uniformity of stress distribution in the soft matrix, the influence coefficient k is introduced to correct the moment generated by stress in the soft matrix. From the moment balance, it can be seen that

By solving Equations (2) and (5) to (10) simultaneously

where , , .

From Equations (2) and (5), it can be seen that σ is a function only with respect to θ12. Therefore, Equation (11) only has two variables, supply pressure p12 and bending angle θ12. Thus, the bending angle θt12 of the soft actuator can be expressed as

If the deformation angle and direction of the actuator are represented as a vector, then it is

The bending deformation relationship for the other three cases of same side inflation can be obtained in the same way.

3.2. Bending with One Chamber Inflated

Chamber 1 is connected to compressed gas, while chambers 2, 3, and 4 are vented to atmosphere. At this moment, φ = −45°. The principal stretch ratio at this time is

Similarly, the compressed gas acts on the front and rear sides. The driving torque is

The moment generated by the deformation of silicone on the side and the top of the unit is

The moment generated by the deformation of silicone at the front and back of the unit is

Also, due to the balance of torque, Equation (15) still holds. By solving Equations (2), (10) and (13)–(17) simultaneously

where , .

Similarly, the overall bending angle θt1 can be expressed as

The bending deformation relationship for the other three chambers can be obtained in the same way.

3.3. Empirical Derivation of Inflation Deformation in Any Chamber

More generally, in order for the soft actuator to produce bending deformation θ in any direction φ, it is necessary to control the air pressures in four chambers. To theoretically analyze the relationship between the four chamber deformation parameters (φ, θ) and pressures (p1, p2, p3, p4), the driving bending moment and resistance bending caused by soft deformation of each chamber can be calculated separately for each chamber’s pressure. The theoretical relationship can be obtained by summing the moments. The steps and methods are the same as the previous two sections, but the deduction and calculation amount are quite large.

Given the existing deformation relationships of a single chamber and two chambers under the same pressure, the four chambers deformation parameters (φ, θ) can be decomposed into the vector sum of deformation under the above two conditions. Namely:

For example, when the pressures of the four chambers are , it can be decomposed into the vector sum of chambers 1 and 2 at a pressure of 60 kPa, chambers 4 and 1 at 20 kPa, and chamber 1 at 20 kPa, expressed as

4. Fabrication and Test of the Multimodal Actuator

4.1. Fabrication

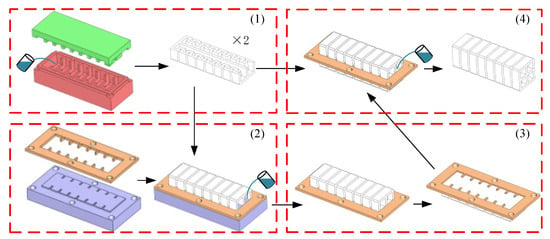

The detailed fabrication process was illustrated in Figure 9. All molds were fabricated using 3D printing (PLA material). (1) Fabrication of Deformation Layers: Two identical deformation layer halves (each including half of the longitudinal constraint layer) were cast using the primary mold. (2) Casting the First Transverse Constraint Half: A second mold set, comprising a base and a thickening layer (2 mm thick), was used. The base featured a 1 mm high boss. The thickening layer was mounted onto the base, creating a 1 mm deep cavity for silicone casting. One deformation layer half was placed within this mold assembly. Silicone was poured into the cavity and allowed to solidify, forming one half of the transverse constraint layer. (3) Assembly for Second Half Casting: The mold base was carefully removed. Due to silicone adhesion, the deformation layer remained attached to the thickening layer. This assembly was then flipped 180°. The space previously occupied by the 1 mm boss was now exposed. Silicone was poured into this space, and the second deformation layer half was placed on top. (4) Final Assembly: After complete silicone solidification, the thickening layer was removed, yielding the complete silicone actuator body. The actuator was then assembled into a complete four-chamber multimodal soft actuator by attaching connectors, pneumatic tubing, and other components, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 9.

Detailed fabrication process of the four-chamber actuator using sectional monolithic casting: (1) casting deformation layers, (2) first transverse constraint casting, (3) assembly for second half casting, (4) final demolding and assembly.

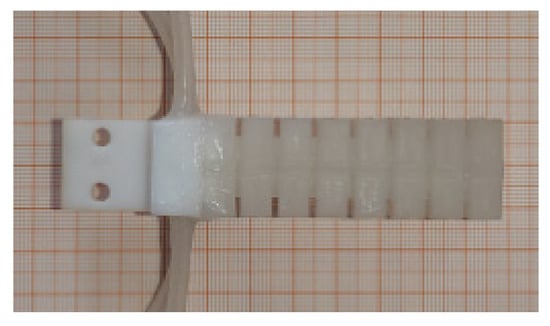

Figure 10.

Fabricated four-chamber multimodal soft actuator.

4.2. Static Characteristic Test

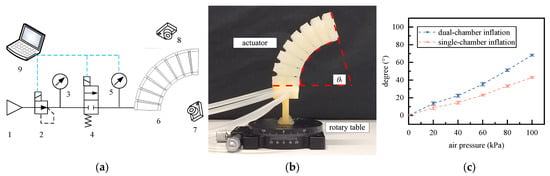

The experimental setup for characterizing the static bending behavior is illustrated in Figure 11a. A regulated air supply was provided by a pressure proportional valve and monitored using Pressure Gauge 1. The air was then delivered to the soft actuator via a solenoid valve, with the instantaneous upstream pressure recorded by Pressure Gauge 2. The actuator was mounted on a fixed base, and a camera was positioned horizontally in front of it to capture its deformation profile under various pressure levels. The resulting bending angles were extracted from the captured images using digital image processing techniques, while acknowledging the inevitable but neglected perspective distortion (Figure 11b). The experimental results for both dual-chamber and single-chamber inflation are summarized in Figure 11c.

Figure 11.

Static Characteristic Test: (a) Experimental Setup: 1—air supply, 2—pressure proportional valve, 3—pressure gauge 1, 4—solenoid valve, 5—pressure gauge 2, 6—actuator, 7—camera in front, 8—camera at top, 9—controller; (b) Bending Angle Process, (c) Experimental Results.

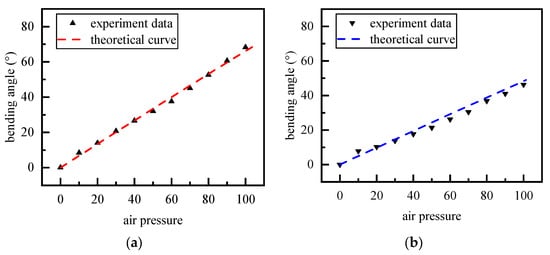

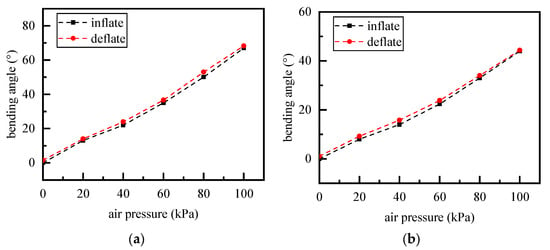

To mitigate the modeling errors introduced by the geometric simplifications in the theoretical derivation, a unified influence coefficient k was introduced into both Equations (11) and (18). A comprehensive set of pressure-angle data was acquired by systematically varying the supply pressure. The dataset from the dual-chamber inflation tests served as the basis for identifying the coefficient k. This was achieved by fitting the theoretical model (Equation (11)) to the experimental data by least squares method in MATLAB (version R2024a), where k = 0.6 was obtained. The optimized value of k was subsequently substituted into the single-chamber model (Equation (18)). As shown in Figure 12, the resulting theoretical curve exhibits excellent agreement with the independent single-chamber experimental data, with minimal observed error. This successful prediction of the pressure-angle relationship for both actuation modes validates the feasibility and effectiveness of introducing the influence coefficient k to compensate for systematic modeling simplifications.

Figure 12.

Experimental Data and Theoretical Curves: (a) Dual-chamber Inflated (b) Single-chamber Inflated.

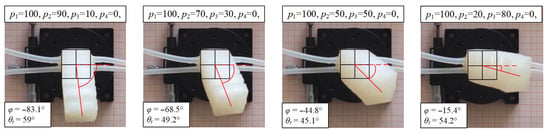

Next, the empirical formula was verified when all four chambers were inflated with different pressures. Another camera was set up to capture top-down views. The pressure values applied to the four chambers and the corresponding deformation directions are shown in Figure 13. The direction angles φ calculated using Equation (20) were −84.38°, −67.75°, −45°, and −13.4°, respectively, with maximum error 2°. The bending angles θt calculated were 58.3°, 47.5°, 43.8°, 52.4°, respectively, with experimental errors all less than 5%. This high precision demonstrates the accuracy of the empirical formula, which simplifies the computational process compared to integration-based solutions.

Figure 13.

Four-chamber Inflated Test.

4.3. Dynamic Characteristic Test

Hysteresis and response time are key performance indicators of soft actuators.

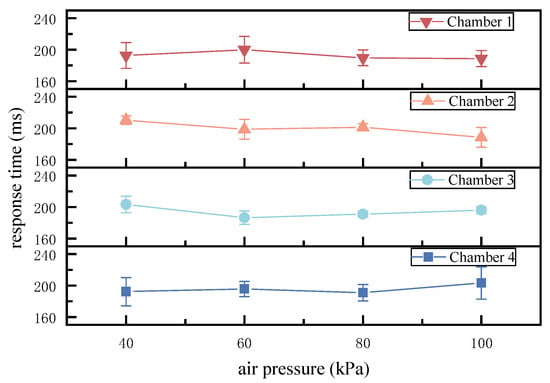

The response time was defined as the duration required for the pressure reading from Gauge 2 to rise from 0 to the stable setpoint value after valve actuation. Tests were conducted at supply pressures ranging from 40 kPa to 100 kPa in increments. Each pressure level was tested three times, and the average value was taken as the final result. The results, also plotted in Figure 14, show that the response time of the soft actuator exhibited minimal fluctuation across the tested pressure range, with an average response time of 195 ms.

Figure 14.

Response Time Test.

Hysteresis was characterized across inflation-deflation cycles. The pressure proportional valve is controlled to pressurize the chamber from 0 kPa to 100 kPa in increments of 20 kPa every 0.5 s (inflation phase), and then gradually reduce 100 kPa back to 0 kPa in the same manner (deflation phase). Record the bending angle at each pressure step. The results, shown in Figure 15, confirm the expected hysteresis due to the material’s nonlinear viscoelasticity. Specifically, at any given pressure, the bending angle during deflation is larger than that during inflation. The average hysteresis was quantified to be approximately 3% for single-chamber actuation and 5% for dual-chamber actuation.

Figure 15.

Hysteresis Test: (a) Dual-chamber (b) Single-chamber.

5. Applications of the Multimodal Soft Actuator

The four-chamber multimodal soft actuator developed in this work can bend in any direction within 3-D space, endowing it with a wide range of capabilities. Two representative applications are presented below: (1) serving as the actuation element of a soft gripper and (2) forming the driving body of an inchworm-inspired soft crawling robot.

5.1. Soft-Gripper Application

The proposed multimodal soft actuator serves as a versatile finger in a gripper setup, enabling capabilities beyond conventional soft grippers. While many soft grippers are limited to simple pinch or enveloping grasps, the independent control of each chamber allows each finger to achieve complex, coordinated motions. This dexterity facilitates not only the secure grasping of objects of varying shapes and fragility but also advanced in-hand manipulation tasks, such as the twisting motion required to screw in a light bulb.

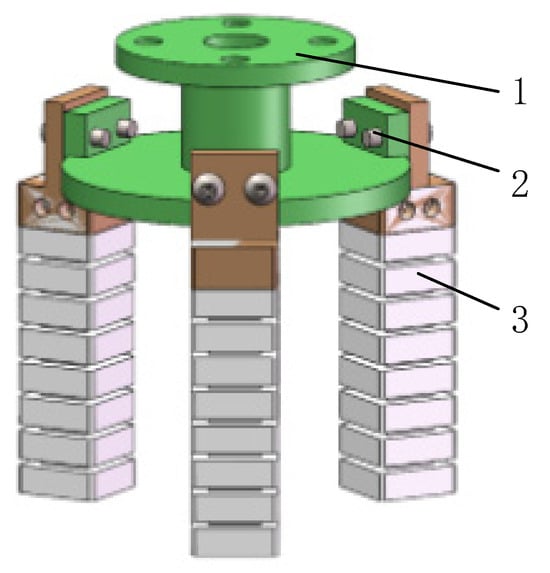

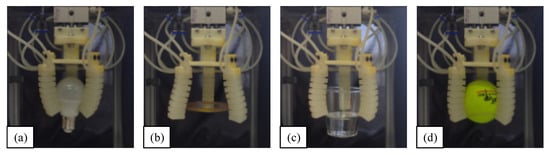

As illustrated in Figure 16, the proposed gripper features a fully compliant fingertip, with the remainder of the structure being rigid. Three multimodal soft actuators were distributed circumferentially around the palm. By regulating the internal air pressure of each actuator, bending was generated to perform grasping.

Figure 16.

Soft Gripper: 1—Connecting flange; 2—screw; 3—multimodal soft actuator.

Select objects of various shapes and materials—such as bulbs, optical disks, glasses, and tennis balls—as grasping targets to evaluate performance. The experimental results, shown in Figure 17, demonstrated that the soft gripper achieves reliable grasping for all tested items. Under a supply pressure of 100 kPa, the maximum payload reached 556 g.

Figure 17.

Grip Experiments: (a) bulb, (b) optical disk, (c) glass, (d) tennis ball.

By further controlling the four chambers of each actuator with different pressures, more sophisticated tasks can be achieved—for example, screwing a light bulb into its socket, as shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Complex Manipulation: Screwing a Light Bulb.

5.2. Soft-Robot Application

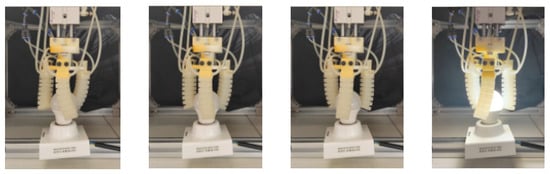

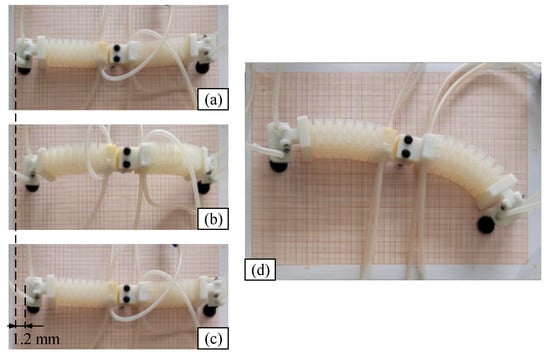

To further demonstrate the versatility of the actuator as a universal drive unit, it was implemented in a soft crawling robot, as shown in Figure 19. Two actuators were mounted on either side of a central joint. Two suckers were installed at both ends to act as front and rear “feet”. This application highlights the actuator’s capability in a domain distinct from manipulation—locomotion. The robot mimics the inchworm’s gait, but its key advanced feature is directional steering. By asymmetrically inflating chambers (e.g., inflating chambers 1 and 4 to turn left, or 2 and 3 to turn right), the robot can alter its crawling path.

Figure 19.

Soft crawling robot based on the four-chamber actuator. (a) Initial state; (b) Inflation; (c) Deflation; (d) Steering.

The crawling sequence was as follows:(1) Vent the rear sucker and supply vacuum to the front cup, anchoring the front foot. (2) Inflate chambers 1 and 2, causing the body to arch upward and the rear foot to advance. (3) Supply vacuum to the rear cup and vent the front cup, fixing the rear foot to the ground. (4) Deflate chambers 1 and 2 to extend the body, pulling the front foot forward. (5) Repeat steps (1)–(4) to achieve continuous forward locomotion, as shown in Figure 19a–c. (6) Inflate chambers 1, 4 or 2, 3 to achieve turning operation, as shown in Figure 19d. The crawling performance was quantitatively evaluated through repeated locomotion cycles. The robot achieved an average forward speed of 1.2 mm/s with a step length of 1.2 mm per cycle. Each complete locomotion cycle took approximately 1 s.

6. Discussion

The theoretical model introduced a unified influence coefficient k (where k = 0.6 for our actuator) to reconcile the analytical moment-balance equations with experimental data. This coefficient collectively accounts for several simplifications inherent in the model: the assumption of uniform wall thickness and stress distribution, the omission of air channels and filets in the cross-sectional geometry, and the neglecting of the coupling effect between chambers. The value of k was determined by fitting the dual-chamber inflation data using a least-squares method, and its subsequent successful application to single-chamber predictions (Figure 12) validates its role in compensating for systematic modeling errors.

It is important to note that the specific value of k is not a universal constant but is dependent on the particular actuator geometry, material properties, and fabrication process. Therefore, for different soft actuator designs, this coefficient should be recalibrated based on experimental data. Our work demonstrates that introducing such an empirically determined coefficient is an effective strategy to bridge the gap between simplified analytical models and the complex behavior of real-world soft actuators, enhancing model utility without sacrificing computational simplicity.

The empirical model employs a vector superposition approach (Equation (20)) to predict deformation under arbitrary pressure inputs by combining the contributions from fundamental single- and dual-chamber inflation states. The physical rationale for this method stems from the decoupled deformation enabled by the inter-chamber gap design. Finite element analysis (Figure 5) quantitatively shows that stress in non-pressurized chambers is an order of magnitude lower than in active ones, indicating a little mechanical coupling. This allows the deformation contributed by each chamber to be considered relatively independent within the operational range.

Experimental validation across various four-chamber pressure configurations (Figure 13) yielded prediction errors below 5%, confirming that the empirical model is accurate within the moderate bending range investigated here—specifically, for bending angles up to approximately 70°. However, the superposition method is an engineering approximation with inherent limitations. Its accuracy is expected to diminish under conditions of very large strain where geometric and material nonlinearities become strongly coupled, or in actuator designs lacking effective decoupling mechanisms between chambers. This method is therefore best suited for actuators with clear structural isolation between chambers operating within a bounded deformation range.

The soft gripper and crawling robot presented in Section 5 serve primarily to illustrate the versatility and multimodal capability of the proposed actuator as a reusable driving unit. These demonstrations are not intended to represent fully optimized systems; for instance, the locomotion speed of the crawling robot has not been maximized, nor has the gripper’s payload been systematically tuned for specific objects. Rather, they validate the actuator’s ability to perform distinct tasks—grasping and locomotion—with the same hardware platform, highlighting its potential for adaptation in diverse soft robotic applications.

While the current model achieves a good balance between accuracy and simplicity within the tested range, several directions exist for further enhancement. Future work will focus on evaluating alternative hyperelastic models (e.g., Ogden) for improved material representation, incorporating viscoelasticity to account for rate-dependent effects and hysteresis, conducting a dedicated study to quantify the limits of inter-chamber coupling and the superposition method’s validity, and performing parametric optimization of the actuator’s geometry to tailor its performance for specific applications.

7. Conclusions

This work presented a four-chamber soft actuator that integrates a cruciform constraint with inter-chamber gaps, enabling omnidirectional bending with minimal cross-chamber coupling. An empirical model based on vector superposition and calibrated with a unified coefficient (k = 0.6) accurately predicts bending deformation within 5% error. The actuator’s versatility was demonstrated through a dexterous soft gripper capable of in-hand manipulation and a steerable crawling robot, confirming its potential as a reusable driving unit for diverse soft robotic tasks. Future efforts will focus on extending the model to account for viscoelastic effects and further optimizing the structure for tailored performance.

8. Patents

The soft crawling robot reported in this manuscript has been patented in China with the No. ZL2024213562824.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, J.Y. (Jiabin Yang); software, formal analysis, H.Z.; investigation, data curation, K.W. and J.Y. (Jiwei Yuan); writing—review and editing, J.C.; funding acquisition, G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Joint Funds of the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. LBMHY25F030001 and the Jiaxing Public Welfare Research Project of Zhejiang Province of China (2024AD10036).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The research data of this paper are all included in this paper, and no new data have been created.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks all editors and reviewers for their handling of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhou, L.; Ren, L.; Chen, Y.; Niu, S.; Han, Z.; Ren, L. Bio-Inspired Soft Grippers Based on Impactive Gripping. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2002017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.-P.; Romario, Y.S.; Bhat, C.; Hentihu, M.F.R.; Zeng, X.-C.; Ramezani, M. Design and fabrication of multi-material pneumatic soft gripper using newly developed high-speed multi-material vat photopoly-merization 3D printer. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 130, 1093–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, F.; Frohn-Sörensen, P.; Engel, B.; Manns, M. Applicability of models to predict the bending behavior of soft pneumatic grippers. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 138, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, T.; Pang, M.; Yang, X.; Qi, Y.; Xia, L.; Qian, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, L.; et al. Research progress in fluid actuation technology of soft robot. Chin. J. Nat. 2023, 45, 217–233. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, D.; Huang, S.; Zhang, D.; Shi, M.; Dai, W.; Wang, S. Design and Basic Performance Analysis of a Bionic Finger Soft Actuator with a Dual-Chamber Composite Structure. Actuators 2025, 14, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Ji, C.; Dou, M.; Wang, X. Bio-G inspired Design and Research on Light Ductile Soft Grippers. China Mech. Eng. 2023, 34, 595–602. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ilievski, F.; Mazze, A.D.; Shepherd, R.F.; Chen, X.; Whitesides, G.M. Soft Robotics for Chemists. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 1890–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepherda, R.F.; Ilievskia, F.; Choi, W.; Morin, S.A.; Stokes, A.A.; Mazzeo, A.D.; Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Whitesides, G.M. Multigait soft robot. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20400–20403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Xu, W.; Li, X. A Soft Robotic Tongue—Mechatronic Design and Surface Reconstruction. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2017, 22, 2102–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosadegh, B.; Polygerinos, P.; Polygerinos, P.; Keplinger, C.; Wennstedt, S.; Shepherd, R.F.; Gupta, U.; Shim, J.; Bertoldi, K.; Walsh, C.J.; et al. Pneumatic Networks for Soft Robotics that Actuate Rapidly. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 2163–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Mei, D.; Wang, J.; Tang, G.; He, L.; Wang, Y. A finger-inspired pneumatic network actuator based on rigid-flexible coupling structure for soft robotic grippers. Intell. Serv. Robot. 2024, 17, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiremath, S.; Mathias, K.A.; Kim, T.-W. 3D-Printed soft pneumatic actuators: Enhancing flexible gripper capabilities. ROBOMECH J. 2025, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wei, Y. Passive Particle Jamming and Its Stiffening of Soft Robotic Grippers. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2017, 33, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.M. A novel approach to enhancing smart stiffness of soft robotic gripper fingers for wider grasping capability. Int. J. Intell. Robot. Appl. 2025, 9, 553–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yao, J.; Zhou, P.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Y. High-force soft pneumatic actuators based on novel casting method for robotic applications. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2020, 306, 111957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.J.; Baek, S.G.; Oh, D.J.; Beak, J.M.; Koo, J.C. ILC-driven control enhancement for integrated MIMO soft robotic system. Intell. Serv. Robot. 2024, 17, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, X.; Guo, Z. A Novel Pneumatic Soft Gripper with a Jointed Endoskeleton Structure. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2019, 32, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, C.; Tang, W.; Jiao, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Zhong, Y.; Zhu, P.; Hu, Y.; Yang, H.; et al. A Bioinspired Stress-Response Strategy for High-Speed Soft Grippers. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2102539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Li, X.; Chen, D.; Liu, J.; Su, J.; Liu, J.; Cao, C.; Yuan, H. A minimally designed soft crawling robot for robust locomotion in unstructured pipes. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2022, 17, 056001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, A.; Goswami, D.; Martinez, R.V. Elastic Energy Storage Enables Rapid and Programmable Actuation in Soft Machines. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 30, 1906603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Domel, A.G.; An, N.; Green, C.; Gong, Z.; Wang, T.; Knubben, E.M.; Weaver, J.C.; Bertoldi, K.; Wen, L. Octopus Arm-Inspired Tapered Soft Actuators with Suckers for Improved Grasping. Soft Robot. 2020, 7, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, J.; Liu, J.; Zhou, K.; Qian, M. An Octopus-Inspired Bionic Flexible Gripper for Apple Grasping. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, H.; Pei, C.; Jin, Z.; Sun, Y. Design and Grasping Force Modeling for a Soft Robotic Gripper with Multi-stem Twining. J. Bionic Eng. 2023, 20, 2123–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y. Design and Motion Analysis of a Wheel-walking Bionic Soft Robot. J. Mech. Eng. 2019, 55, 27–35. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.-Q.; Li, W.-H.; Li, J.-H.; Zhou, H.-L.; Deng, Z.-C. Tuning stiffness with granular chain structures for versatile soft robots. Soft Robot. 2023, 10, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Xu, Z.; Xiao, J.; Hu, W.; Huang, H.; Zhou, F. Multimodal Soft Robot for Complex Environments Using Bionic Omnidirectional Bending Actuator. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 193827–193844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Fan, Y.; Yang, P.; Cao, T.; Liao, H. Worm-Like Soft Robot for Complicated Tubular Environments. Soft Robot. 2019, 6, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Xu, D.; Wang, Y.; Liang, C. Modeling and Experimental Study of Multichambered Composite. J. Tianjin Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2025, 58, 285–292. [Google Scholar]

- Drotman, D.; Jadhav, S.; Karimi, M.; de Zonia, P.; Tolley, M.T. 3D Printed Soft Actuators for a Legged Robot Capable of Navigating Unstructured Terrain. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mustaza, S.M.; Elsayed, Y.; Lekakou, C.; Saaj, C.; Fras, J. Dynamic Modeling of Fiber-Reinforced Soft Manipulator: A Visco-Hyperelastic Material-Based Continuum Mechanics Approach. Soft Robot. 2019, 6, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marechal, L.; Balland, P.; Lindenroth, L.; Petrou, F.; Kontovounisios, C.; Bello, F. Toward a common framework and database of materials for soft robotics. Soft Robot. 2021, 8, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).