Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes is a major foodborne pathogen associated with increasing global public health concern due to numerous outbreaks. Rapid pathogen detection is critical for reducing both the incidence and severity of foodborne illnesses. Recent advances in nanotechnology are transforming analytical methods, particularly for detecting foodborne pathogens. Magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) and gold nanoparticles (GNPs) are among the most widely used nanomaterials in this field. This study investigated the potential use of MNPs and GNPs for the rapid and specific isolation of L. monocytogenes from fresh salad, deli meat, and frozen vegetables. L. monocytogenes (ATCC 19117) served as the model organism for biosensing and target capture. Results showed that the limits of detection (LoDs) for the GNP-based plasmonic/colorimetric biosensor and the MNP-based biosensor were 2.5 ng/µL DNA and 1.5 CFU/mL, respectively. Both GNPs and MNPs specifically detected L. monocytogenes even in the presence of closely related pathogens. Integration of MNPs and GNPs significantly enhanced the sensitivity of L. monocytogenes detection. Within one hour, naturally contaminated pre-packaged salad samples demonstrated clear evidence of effective direct capture by MNPs and specific identification by GNPs. This combined approach enables rapid and accurate on-site detection of L. monocytogenes, facilitating timely intervention and reducing the risk of contaminated foods reaching consumers.

1. Introduction

Listeria monocytogenes is a major foodborne pathogen responsible for invasive listeriosis and gastroenteritis, with symptoms ranging from mild gastrointestinal illness to septicemia, meningitis, abortion, and death [1]. Although infections are relatively rare, the case fatality rate approaches 20–30% and disproportionately affects the elderly and immunocompromised [1]. In the United States, an estimated 1600 infections occur annually, nearly 20% of which are fatal [1], resulting in substantial economic losses estimated at USD 1.282 million per case and USD 2.04 × 1012 overall [2]. Outbreaks also lead to major financial disruptions, including 22–27% declines in sales of ready-to-eat (RTE) foods following recalls [3,4]. Preventing contaminated products from entering the market therefore remains a public health and economic priority.

L. monocytogenes is ubiquitous in nature and can enter the food chain through environmental reservoirs or contaminated farm animals [5]. Its ability to grow at refrigeration temperatures, tolerate wide pH and water activity ranges, and form biofilms in food processing facilities contributes to its persistence and contamination of food-contact surfaces [6]. RTE foods are at particular risk because they receive no further antimicrobial treatment prior to consumption [7]. Although the infective dose is generally considered high (>104 CFU/g) [8], susceptible individuals may develop illness at levels as low as 102–104 CFU/g [9,10]. Prevalence studies have shown contamination in 10% of frozen vegetable samples in England [11], and a major U.S. outbreak in 2016 linked to IQF vegetables resulted in nine illnesses, three deaths, and extensive product recalls [12,13,14]. These events highlight the need for rapid, reliable detection methods that can prevent contaminated foods from reaching consumers [15].

Accurate detection remains central to surveillance and outbreak response. Traditional culture-based methods provide high sensitivity (1–5 CFU/test portion) [16,17] but are slow and labor-intensive and require specialized laboratory infrastructure. Rapid assays, including lateral flow tests, ELISA, and PCR, offer improved speed and specificity [16] but remain limited by cost, potential false positives [6], matrix interference, and dependence on trained operators and well-equipped laboratories [6,18,19]. Many workflows are further hindered by food matrix complexity [20], low pathogen loads that require 8–18 h of enrichment before detection [21], and narrow testing budgets within the food industry [22]. Although magnetic bead-based concentration methods can improve bacterial recovery, they often yield variable results and may be affected by food debris [16,23,24,25,26]. Immunomagnetic nanoparticles improve specificity but are constrained by antibody cost, limited stability, and reduced performance in complex matrices [27,28].

Carbohydrate-coated magnetic nanoparticles (gMNPs) offer a cost-effective, robust, and broadly reactive alternative to antibody-based capture methods [29]. These nanoparticles demonstrate long shelf life, stability, and compatibility across diverse food matrices and can be paired with downstream biosensing platforms to achieve high sensitivity without the need for expensive or fragile recognition ligands [30,31,32,33,34,35]. Biosensor technologies, particularly optical systems, for the detection of L. monocytogenes provide rapid, real-time, and on-site analytical capabilities for food safety monitoring [36]. In these systems, interactions between bioreceptors (nucleic acids, antibodies, enzymes, or whole cells) and target molecules are converted into measurable physical signals through optical, electrochemical, or mass-based transducers [37]. Gold nanoparticle (GNP)-based optical biosensors are especially promising due to their strong surface plasmon resonance (SPR), which enables highly sensitive detection measurable by UV–Vis spectrophotometry [38,39].

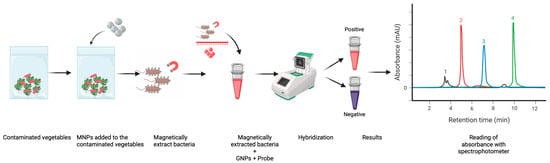

Despite these advances, several limitations persist. Traditional pathogen extraction workflows rely on recognition ligands requiring cold storage, which increases cost and reduces practicality in low-resource settings; in contrast, glycan-coated MNPs circumvent this need and allow for rapid capture of large sample volumes [40]. Likewise, many GNP-based assays depend on DNA amplification or lengthy probe-functionalization steps that can exceed 24 h [41]. To address these constraints, the present study demonstrates a rapid, amplification-free method for detecting L. monocytogenes using a combination of MNP-based bacterial concentration and GNP-based colorimetric DNA detection in fresh salad, deli meat, and frozen vegetable matrices (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Workflow of magnetic nanoparticle–assisted bacterial capture and colorimetric detection from produce. Produce samples are mixed with functionalized MNPs, allowing selective binding to bacterial cells, followed by magnetic separation. Bound bacteria react with GNP-based probes to generate positive (red) or negative (purple) colorimetric outputs, which are quantified spectrophotometrically and visualized as chromatographic peaks.

In this study, we aimed to address the need for rapid, sensitive, and field-deployable detection of L. monocytogenes in RTE foods. We identified a critical gap in the availability of low-cost biosensing systems capable of both concentrating and detecting pathogens without DNA amplification or antibody-based capture. We hypothesized that carbohydrate-coated magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), used in combination with dextrin-capped gold nanoparticles (GNPs), could achieve rapid, specific, and highly sensitive detection of L. monocytogenes directly from complex food matrices. To test this hypothesis, our objectives were to: (i) evaluate the capture efficiency of MNPs in pure culture and food matrices; (ii) determine the sensitivity and specificity of the GNP-based biosensor; and (iii) validate the integrated MNP–GNP system using naturally contaminated food samples.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Chemicals

Magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) coated with chitosan and gold nanoparticles (GNPs) coated with dextrin were developed by the Alocilja Research Group at Michigan State University. The MNPs are shelf-stable at room temperature for at least 3 years, while the GNPs are stored at 4 °C and remain stable for at least 3 years. The GNP-MUDA formulation is also stored at 4 °C and is stable for at least 6 months. The MNPs, composed of iron oxide (magnetite), are coated with chitosan to facilitate efficient capture of bacterial cells. The chitosan-coated MNPs used in this study had an approximate core size of 50–80 nm, with an average stock concentration of 5 mg/mL. The dextrin-capped GNPs were approximately 20–25 nm in diameter and supplied at a concentration optimized for colorimetric assays. Nanoparticles were stored at 4 °C in the dark to prevent aggregation and equilibrated to room temperature prior to use. This cost-effective approach eliminates the need for expensive antibodies or aptamers commonly required in immunomagnetic separation, allowing the nanoparticles to interact effectively with glycoproteins on the bacterial cell surface [20].

2.2. Primer Design and Biosensor Probe

Primers previously reported in the literature were adopted, and the corresponding gene sequences were retrieved and processed using SnapGene® software (GSL Biotech LLC, a Dotmatics company; Chicago, IL, USA, snapgene.com) for specific primer and probe design. The biosensor probe used in this study was Lmo0733-2F-Biosensor with the following sequence: /5AmMC6/TG GAA AGT TGT TTG CTC TTT CTT TTG TTG TTC TGC TGT ACG A.

2.3. Bacterial Culture

Listeria monocytogenes (ATCC 19117) was obtained from the Center for Food Animal Health, Food Safety and Defense Laboratory, Tuskegee University, USA. Cultures were grown in Listeria Enrichment Broth (LEB) (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, CA, USA) at 30 °C for 24 h and used throughout the study.

2.4. Spiking of PBS and Salad Samples to Determine the Limit of Detection (LoD) of MNPs and GNPs

The limits of detection (LoD) of the MNP and GNP biosensors were evaluated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and salad samples through spiking and recovery experiments. L. monocytogenes (ATCC 19117) was cultured in LEB at 30 °C for 24 h and centrifuged to obtain a bacterial pellet. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 1× PBS to a 0.5 McFarland standard (1.5 × 108 CFU/mL), corresponding to 0.1 absorbance on a turbidimeter.

Salad samples were first exposed to UV light for 30 min to eliminate naturally occurring L. monocytogenes. Ten grams of UV-treated salad were weighed into a Whirl-Pak bag and spiked with 1 mL of the 0.5 McFarland suspension. Nine milliliters of PBS were then added, and the mixture was homogenized in a stomacher for 2 min, yielding a concentration of 1.5 × 108 CFU/mL.

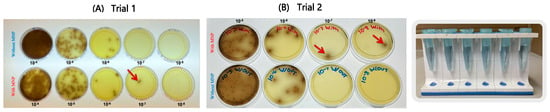

From this homogenate, 100 µL was transferred into 900 µL of PBS (1.5 × 107 CFU/mL), followed by 10-fold serial dilutions from 10−1 (1.5 × 107 CFU/mL) to 10−8 (1.5 CFU/mL). These serial dilutions were prepared in three sets (Figure 2):

Set A: without MNPs

Set B: with MNPs

Set C: for GNP LoD experiments

Dilutions from 10−4 to 10−8 were used in all experiments. Uninoculated salad samples served as negative controls. The limit of detection (LoD) was defined as the lowest dilution at which L. monocytogenes was consistently detected in at least 95% (≥19/20) of replicate reactions. All experiments, including spiking trials, capture efficiency assays, GNP sensitivity and specificity tests, and naturally contaminated sample analyses, were performed in triplicate unless otherwise stated. Mean values were used for all calculations.

Figure 2.

Serial tenfold dilutions (10−4–10−8) of ATCC Listeria monocytogenes in PBS plated on Oxford agar (A,B). Results represent two independent experimental trials. Red arrows indicate the capture efficiency of MNPs at the lowest detectable dilution level.

2.5. Capture Efficiency of MNPs

Capture efficiency was assessed using the two sets of serial dilutions described in Section 2.4 (Set A: without MNPs; Set B: with MNPs). The experiment was based on the method described by [21] with modifications.

For Set B, 10 µL of 5 mg/mL MNPs were added to each serially diluted sample (10−4 to 10−8). Tubes were incubated in a shaker at 32 °C for 10 min and then placed on a magnetic rack for 5 min to pellet the MNP-bacteria complexes. The supernatant was carefully removed without disturbing the complexes, which were then resuspended in 90 µL of PBS. The entire resuspension was plated on Listeria Oxford agar and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h.

For Set A, 20 µL of each dilution was directly plated without MNP treatment to determine the initial CFU/mL. Colonies were enumerated for all dilutions, and capture efficiency (CE) was calculated as [21]:

Experiments were performed twice, and mean colony counts were used for CE calculations.

2.6. Analytical Specificity of GNP Biosensor for Detecting L. monocytogenes

L. monocytogenes (ATCC 19117) was grown in LEB at 30 °C for 24 h, pelleted by centrifugation, and subjected to DNA extraction using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). Extracted DNA was used in the GNP biosensor assay.

To evaluate specificity, Escherichia coli O157:H7 DNA was extracted and included as a non-target control. The GNP protocol followed Dester et al. [40]. Briefly, 5 µL GNPs, 5 µL probe, and 10 µL DNA were combined in a 0.2 mL tube. Hybridization was performed in a thermocycler with the following conditions: 95 °C for 5 min (denaturation); 55 °C for 10 min (annealing); 4 °C for 5 min (cooling).

Then, 3 µL of 0.1 M HCl were added gradually, and colorimetric results were read after 5–10 min. Target DNA remained red, whereas non-target DNA aggregated and turned purple/blue. Absorbance at 520 nm was measured using a NanoDrop™ 2000C spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Wilmington, DE, USA).

2.7. Assessment of MNP and GNP Biosensor Combination in Naturally Contaminated Food Samples

A total of 50 food samples, including premade salad, frozen spinach, frozen mixed vegetables, frozen Brussels sprouts, deli meat, queso fresco, and RTE fresh lettuce were collected from Tuskegee and Auburn, Alabama, USA.

Presence of L. monocytogenes was confirmed using the FDA BAM method. Briefly, 10 g of each sample were mixed with 100 mL Buffered Peptone Water and shaken for 30 s at 250 rpm, then incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. One hundred microliters of the suspension were transferred to LEB and incubated for 48 h at 30 °C. Cultures were plated onto BIO-RAD Agar and Oxford Agar, then incubated for 48 h at 37 °C. A rhamnose biochemical test was performed for confirmation.

For biosensor analysis, 10 g of each sample were mixed with 100 mL Buffered Peptone Water in a Whirl-Pak bag and homogenized for 30 s at 250 rpm. Then, 10 µL of 5 mg/mL MNPs were added and incubated in a shaker for 10 min. Samples were placed on a magnetic rack for 5 min, and the captured MNP-bacteria complex was resuspended in 90 µL PBS.

For detection, 5 µL GNPs, 5 µL probe, and the MNP-bacteria complex were combined and subjected to the same thermocycling and HCl-induced colorimetric protocol described in Section 2.6. PCR was performed on extracted genomic DNA to confirm that GNP stability corresponded to the presence of L. monocytogenes DNA.

2.8. Data Analysis

A two-way ANOVA was used to compare means of L. monocytogenes cells captured bsy MNPs in spiked PBS and spinach samples using GraphPad Prism version 10.3.0. Significance was set at α = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Spiking of PBS and Salad Samples to Determine the LoD of MNPs and GNPs

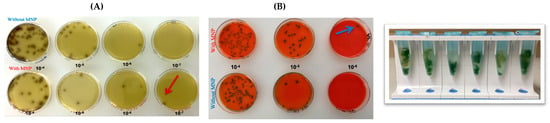

Serial dilution experiments performed in PBS (Figure 2) demonstrated that the MNPs successfully captured L. monocytogenes down to the 10−7 and 10−8 dilutions, equivalent to concentrations of approximately 15 CFU/mL and 1.5 CFU/mL, respectively. Similarly, experiments conducted with spinach samples (Figure 3) showed that the MNPs captured L. monocytogenes as low as the 10−7 dilution (15 CFU/mL per 10 g of food). These findings confirm that the MNPs maintained strong capture capability even in a complex food matrix.

Figure 3.

Serial tenfold dilutions (10−4–10−8) of ATCC L. monocytogenes inoculated onto spinach and subsequently plated on Oxford agar (A) and RAPID’ L. mono agar (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) (B). Red and blue arrows indicate the capture efficiency of MNPs at the lowest detectable dilution level.

3.2. MNPs Capture Efficiency Results

Capture efficiency results demonstrated robust performance of MNPs in both PBS and spinach samples. In PBS, the capture efficiency ranged from 69% to 71%. At the lowest dilutions tested (107 and 108, corresponding to 15 CFU/mL and 1 CFU/mL), one colony was captured using MNPs, whereas no colonies were observed in corresponding dilutions without MNPs.

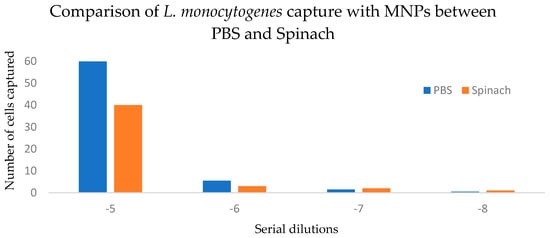

In spinach, capture efficiency ranged from 66% to 90% (Figure 4), highlighting the ability of MNPs to function effectively even in food matrices containing natural debris and inhibitory substances.

Figure 4.

Comparison of L. monocytogenes capture with MNPs between spiked PBS and spinach samples. p > 0.05 (0.355).

Two-way ANOVA without replication showed a significant effect of dilution level on capture efficiency (p = 0.0138), accounting for 94.4% of total variation. The matrix (PBS vs. spinach) did not significantly affect capture efficiency (p = 0.355), contributing only 1.6% of the variation. Because measurements were not replicated within each matrix-by-dilution combination, interaction effects could not be tested. The 95% confidence interval for the mean difference in capture efficiency between PBS and spinach was −10.30 to 21.05, indicating no statistically significant difference between matrices (Table 1).

Table 1.

Two-way ANOVA (Matrix × Dilution Level) for capture efficiency.

3.3. Analytical Sensitivity of GNP Biosensor for Detecting L. monocytogenes

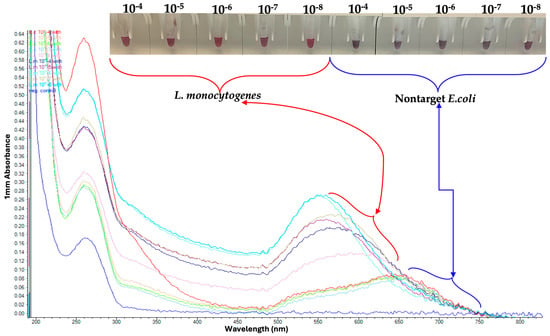

Using a range of DNA concentrations, the GNP biosensor effectively detected purified L. monocytogenes DNA at concentrations as low as 2.5 ng/µL, even in the presence of non-target E. coli DNA, as shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6. These results demonstrate both the high sensitivity and the robustness of the GNP-based detection platform.

Figure 5.

Serial Dilutions of L. monocytogenes tested on Gold Nanoparticle (GNP). Red coloration indicates dispersed GNPs in the presence of L. monocytogenes DNA, whereas purple/blue coloration represents nanoparticle aggregation in the absence of target DNA.

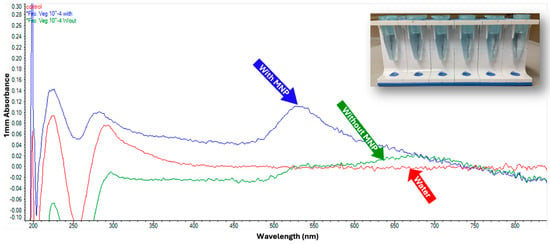

Figure 6.

GNP testing on L. monocytogenes without DNA extraction. This assay demonstrates that GNPs can detect released bacterial DNA following thermal lysis without the need for DNA extraction.

3.4. Observed Analytical Specificity of GNP Biosensor for Detecting L. monocytogenes

Following magnetic capture using MNPs, the GNP biosensor successfully detected L. monocytogenes across dilutions from 10−4 to 10−8, corresponding to concentrations as low as 1 CFU/mL (Figure 5). The assay clearly differentiated L. monocytogenes from the non-target pathogen E. coli, confirming high analytical specificity.

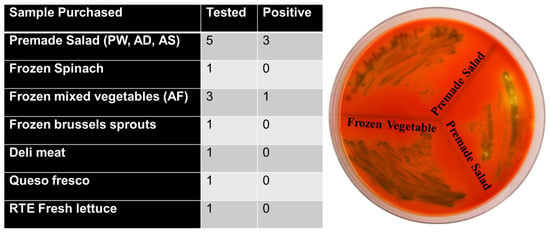

3.5. Assessment of MNP and GNP Biosensors in Naturally Contaminated Food Samples

Among the 50 food samples tested, 13 were positive for L. monocytogenes and were subjected to further analysis. The premade salad category (samples PW, AD, AS) showed the highest positivity rate of 60% (3/5). In the frozen food category, frozen mixed vegetables exhibited a positivity rate of 33.3% (1/3), while both frozen spinach and frozen Brussels sprouts tested negative.

Single samples of deli meat, queso fresco, and RTE fresh lettuce all tested negative (0%).

Across all sample types, the overall positivity rate was 30.8%, with premade salads showing the greatest incidence of contamination (show in Figure 7). PCR verification of positive samples is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 7.

Listeria monocytogenes detection in RTE food samples. Table summarizes the number of food items tested and those positive for L. monocytogenes. Premade salads showed 3 positives out of 5 samples, and one frozen mixed vegetable sample also tested positive. All other products were negative. (Right) Representative chromogenic agar plate displaying typical dark green/black L. monocytogenes colonies recovered from premade salad and frozen mixed vegetable samples.

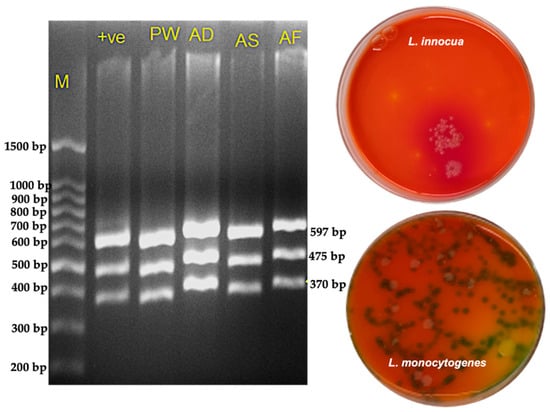

Figure 8.

Confirmation of Listeria isolates by PCR and selective plating. (Left) Agarose gel electrophoresis showing amplification profiles of Listeria monocytogenes premade salad (PW, AD, AS) and frozen mixed vegetables (AF). Lane M: molecular weight marker; Lane +ve: positive control (L. monocytogenes serogroup 4 d, ATCC strain). All test lanes display the characteristic multi-band pattern consistent with the expected L. monocytogenes target fragments. (Right) Selective plating on chromogenic medium illustrating phenotypic differentiation between L. innocua and L. monocytogenes. L. innocua colonies (top plate) appear smooth, pale, and non-pigmented, lacking the characteristic color change. L. monocytogenes colonies (bottom plate) exhibit the typical darker, bluish-green to black colonies indicative of β-glucosidase activity. The combined molecular and culture-based results confirm accurate identification and discrimination of Listeria species from RTE food samples.

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate the effectiveness of magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) and gold nanoparticles (GNPs) for capturing and detecting Listeria monocytogenes in a variety of food matrices, including phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and spinach. The findings highlight the potential of these nanoparticle-based biosensing methods as rapid, sensitive, and cost-effective alternatives to conventional pathogen detection techniques. Several biosensor platforms have previously been used for the detection of L. monocytogenes (Table 2), and the present study contributes to this growing body of evidence.

The ability of MNPs to capture L. monocytogenes at extremely low concentrations down to dilutions as high as 10−7 and 10−8 in PBS, demonstrates the high sensitivity of the method. These dilutions correspond to bacterial concentrations of approximately 15 CFU/mL and 1.5 CFU/mL, respectively. Given that the infectious dose for healthy individuals is estimated at 10 to 100 million CFU, and as low as 0.1 to 10 million CFU for individuals at higher risk [42], the sensitivity of this biosensing system is sufficient to support early detection and prevention of listeriosis. Early identification is essential for minimizing the spread of contamination and preventing foodborne outbreaks. The significant effect of dilution level observed in the ANOVA is biologically expected, as nanoparticle bacteria collision probability decreases with declining microbial load. This supports the sensitivity profile of the MNP system and aligns with kinetic interaction models demonstrating reduced capture rates at lower bacterial concentrations.

Capture efficiency results further support the robustness of the MNP platform. In PBS, capture efficiency ranged from 69% to 71%, while in spinach, a more complex matrix containing natural inhibitors, it ranged from 66% to 90%. This performance indicates that MNPs can function effectively across sample types and withstand the challenges posed by food matrices. Importantly, the ability to detect L. monocytogenes in spinach at concentrations as low as 15 CFU/mL illustrates the real-world applicability of this approach to ready-to-eat (RTE) foods, where low levels of contamination can pose significant risks due to the absence of a kill step prior to consumption. Statistical analysis further demonstrated that the matrix (PBS vs. spinach) did not significantly influence capture efficiency (p = 0.355). The 95% confidence interval for the mean difference between matrices (−10.30 to 21.05) included zero, indicating that any true difference is likely small. This suggests that moderate matrix-associated inhibitors present in leafy greens do not substantially interfere with glycan–nanoparticle interactions. These findings align with previous reports showing that carbohydrate-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles retain performance in the presence of fibers, pigments, and polyphenols commonly found in plant-based foods.

The strong capture performance observed in this study is consistent with known mechanisms of bacterial interaction with carbohydrate-coated magnetic nanoparticles. Prior work has shown that glycan-functionalized MNPs bind to Gram-positive bacteria through a combination of electrostatic attraction, hydrophobic interactions, and glycan-mediated adhesion. The negatively charged teichoic acids and peptidoglycan components of the Listeria cell wall interact with hydrophilic or positively charged carbohydrate ligands on the nanoparticle surface, while lectin-like domains on bacterial surfaces can engage mannose-, galactose-, and glucan-based ligands [30,31,32,33,34,35]. In addition, hydrophobic regions of the bacterial envelope promote adsorption via van der Waals and hydrophobic forces, facilitating rapid formation of bacteria nanoparticle complexes even in complex food matrices. These mechanisms help explain the high capture efficiencies observed across different sample types in this study.

The GNP-based biosensor also demonstrated strong analytical performance, exhibiting high specificity and sensitivity. The assay successfully distinguished L. monocytogenes from the non-target organism Escherichia coli, minimizing the likelihood of false-positive results, an important advantage in food safety testing where unnecessary recalls can have substantial economic impacts [43]. The GNP biosensor detected L. monocytogenes at levels as low as 1 CFU/mL following magnetic concentration, underscoring its capability for sensitive downstream detection. Notably, the limit of detection (LoD) reported in this study contrasts with previous findings by Xiao et al. [44], who reported an LoD of 102 CFU/mL in lettuce samples, highlighting the improved sensitivity achieved using the combined MNP–GNP system.

The performance of the nanoparticle system in naturally contaminated food samples further demonstrates its practical applicability. Of the 50 samples tested, 13 were positive for L. monocytogenes, with premade salads exhibiting the highest positivity rate (60%). This aligns with previous reports indicating that RTE salads are among the highest-risk products for Listeria contamination [45,46]. The detection of L. monocytogenes in frozen mixed vegetables is consistent with the documented persistence of this pathogen in frozen foods, such as those implicated in the 2016 multistate outbreak involving individually quick-frozen (IQF) vegetables [13]. Negative results in deli meat, queso fresco, and RTE lettuce samples could be due to the absence of contamination or the limited number of samples tested. Food matrices naturally contain inhibitors such as fats, fibers, and polyphenols that can interfere with nanoparticle binding and optical responses. The ability of the MNP–GNP system to detect L. monocytogenes in spinach and premade salads demonstrates tolerance to moderate matrix interference; however, future studies should quantify the influence of pH, fat content, and particulate debris on capture efficiency. The lack of a significant matrix effect is advantageous for practical applications, as it indicates that the MNP system can deliver consistent performance across both simple (PBS) and complex (spinach) matrices. This level of robustness distinguishes the glycan-coated MNPs from antibody-based magnetic beads, which frequently exhibit reduced efficiency in complex samples due to steric hindrance or nonspecific competitive binding. However, the present findings do not rule out the possibility that highly fatty, viscous, or protein-rich matrices may impose stronger inhibitory effects. Additional validation across a broader range of RTE food products will clarify the operational limits of the technology.

Compared to traditional culture-based methods, the nanoparticle-based approach presented here offers several significant advantages. Although culture methods remain the gold standard for Listeria detection, they are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and require trained personnel and specialized facilities [47]. Moreover, conventional methods typically detect L. monocytogenes at levels ranging from 5 to 100 CFU per 25 g of food [48], while the combined MNP–GNP system used in this study achieved substantially lower detection limits. Importantly, the nanoparticle-based workflow can substantially reduce or eliminate the need for lengthy pre-enrichment steps, enabling faster decision-making during routine testing and outbreak response.

Detection with GNPs can be completed in approximately 30 min, and pathogen capture with MNPs requires about 15 min. With downstream confirmation through PCR or culture, the entire workflow can be completed within 1–24 h, markedly faster than conventional protocols. In addition, nanoparticle technology allows a single operator to perform the full detection process efficiently, reducing labor demands and overall operational costs. The assay is also highly cost-effective, with an estimated cost of less than USD 0.01 per reaction. Minimal equipment requirements further support its use as a point-of-care diagnostic tool [49].

A previous study reported the use of biofunctionalized magnetic nanoparticles with nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) for rapid detection of L. monocytogenes in food samples. Although the NMR-based method required only 40 min, compared to the five days required by some national standards, the test cost remained relatively high at approximately USD 38 per assay, with detection limits ranging from 3 to 103 CFU/mL [16]. In contrast, the system used in the present study offers enhanced sensitivity at significantly lower cost, making it more suitable for widespread adoption in food safety monitoring.

Overall, the results demonstrate that the combined use of MNPs and GNPs represents a highly promising approach for rapid and sensitive detection of L. monocytogenes in diverse food matrices. The method is well-suited for routine monitoring, outbreak investigations, and on-site testing at food processing facilities, potentially improving food safety and reducing the risks associated with Listeria contamination. This nanoparticle-based workflow could complement existing regulatory detection protocols, including FDA BAM and ISO 11290 [50], by providing rapid on-site screening to enable earlier intervention during contamination events. Taken together, these findings confirm that dilution level but not matrix drives variability in capture efficiency, reinforcing the robustness and practical suitability of the MNP platform for diverse food safety applications.

Table 2.

Summary of biosensing Strategies for Listeria monocytogenes.

Table 2.

Summary of biosensing Strategies for Listeria monocytogenes.

| Recognition Molecule/Nanomaterial | Sample Matrix | Detection Time | LOD | Method Type | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycan-coated MNPs + dextrin-capped GNPs (This study) | RTE foods | 3 h | 1.5 CFU/mL (MNP); 2.5 ng/µL DNA (GNP) | Magnetic capture + plasmonic colorimetric | This study |

| CRISPR/Cas12a (RAA-CRISPR platform) | Pure culture, genomic DNA | 20–30 min | 350 CFU/mL; 5.4 × 10−3 ng/µL | CRISPR fluorescence | [51] |

| High-resolution melting (HRM) qPCR | Roast pork | 3–6 h | 6.2 × 103–6.2 × 104 CFU/mL | mPCR + HRM qPCR | [52] |

| PEG-cefepime MNPs | Lettuce, juices, meat | 110 min | 3.1 × 102 CFU/mL | Antibiotic MNP + colorimetry | [44] |

| Antibody-ZIF-8 GOD@ZIF-8@Ab | Juice | NS | 101 CFU/mL | Colorimetry | [53] |

| Teicoplanin MNPs | PBS, ground beef | NS | 2.6 × 101 CFU/mL | Fluorescence | [54] |

| Ampicillin-MNPs + qPCR | Milk | 2.5 h | 102 CFU/mL | qPCR | [55] |

| Aptamer-linked AuNP + MNP | Milk | NS | 6 CFU/mL | Colorimetric immunoassay | [56] |

| Immunomagnetic beads + SERS | Milk | NS | 12 CFU/mL | SERS | [57] |

| D-amino acid MNPs | Milk, meat | 30 s | 2.17 × 102 CFU/mL | Colorimetric | [58] |

| Antibody–MNP + nitrocellulose | Vegetables | 35 min | 1 × 102 CFU/g | Colorimetry | [59] |

| Fe3O4@silica antibody NPs | Pure culture | 30 min | NS | Magnetic capture | [60] |

| AuNP + Ag nanoclusters + aptamer MNPs | Food | NS | 10 CFU/mL | Colorimetric | [61] |

| Impedance immunosensor + MNPs | Lettuce, milk, beef | 3 h | 104 CFU/mL | Impedance | [62] |

| Aptamer-MNP + AIE fluorescence | Spiked samples | NS | 10 CFU/mL | Fluorescence | [63] |

| Vancomycin-PEG-MNPs + PCR | PBS, lettuce | <4 h | 30 CFU/g | PCR | [64] |

| Fe/Fe3O4 NPs + antibodies (NMR) | Milk powder, lettuce | NS | 3 MPN | NMR | [16] |

| CRISPR/Cas12a electrochemical | Plant samples | 2 h | 0.68 aM; 940 CFU/g | Electrochemical | [36] |

| Mesoporous silica microarray | Food samples | 2 h | 102 CFU/mL | Microarray | [65] |

| Aptamer-MNP + AuNP amplification | Meat, milk | 1.5 h | 10 CFU/mL | Colorimetric | [66] |

| AuNP-SD-PMA-qPCR | Milk | 6 h | 5 × 101 CFU/g | qPCR + viability dye | [67] |

| Aptamer-based MNP system | Food | 18 h | 103 CFU/mL | Fluorescence | [68] |

| Boronate affinity magnetic + fluorescence | Lettuce | 35 min | 2.2 × 101 CFU/mL | Fluorescence | [69] |

| Cefepime-PEG-MNPs + colorimetry | Lettuce, juice, meat | 100 min | 3.1 × 102 CFU/mL | Colorimetric | [44] |

| G-quadruplex DNAzyme colorimetric | Pork | 4 h | 3.1 CFU/mL | Colorimetric | [70] |

| Lateral flow strip (end-on mAb) | Blood, milk, mushrooms | 15 min | 101–104 CFU/mL | Lateral flow | [71] |

| QCM aptasensor + MNPs | Milk, cheese, meats, vegetables | 10 min | 148 CFU/mL | QCM | [72] |

| LAMP electrochemical sensor | Multiple foods | 30 min (post enrichment) | 1 CFU/25g | LAMP + electrochemical | [73] |

| CPA isothermal amplification | Rice flour | 60 min | 104 CFU/mL | CPA | [74] |

| AlphaLISA nucleic acid assay | Milk, juice | NS | 250 attomole | AlphaLISA | [75] |

Abbreviations: LOD, limit of detection; NS, not specified; CFU, colony-forming units; MNPs, magnetic nanoparticles; GNPs, gold nanoparticles; CRISPR, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats; HRM, high-resolution melting; SERS, surface-enhanced Raman scattering; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; QCM, quartz crystal microbalance; LAMP, loop-mediated isothermal amplification; CPA, crossing priming amplification.

Limitations and Future Directions

While this study demonstrates the strong potential of MNPs and GNPs for the detection of L. monocytogenes, several limitations should be addressed in future research. One limitation is the non-specific nature of carbohydrate-coated MNPs. Although these particles provide a cost-effective alternative to antibody-based capture, their non-specificity may be a disadvantage in situations where multiple pathogens are present in the same sample, potentially complicating interpretation of results. Future work should therefore focus on improving the specificity of MNPs, for example, by incorporating multifunctional ligands capable of simultaneously capturing and differentiating among multiple pathogens. Selectivity in natural samples may also be enhanced by using pathogen-specific carbohydrate epitopes; for instance, biotinylated oligosaccharides have been successfully applied to streptavidin-coated magnetic beads to capture E. coli strains [32].

Another important direction is the integration of this nanoparticle-based detection approach with other rapid diagnostic technologies, such as microfluidics, automated processing systems, or portable biosensing devices. Such integration would enable high-throughput, hands-free screening of food samples with minimal operator input, reducing potential human error and enhancing testing efficiency. This would be especially beneficial in food production environments, where routine monitoring often requires processing large sample volumes within short time frames.

Overall, future development should aim to enhance the selectivity, automation, and scalability of the nanoparticle-based detection system. These improvements will support the broader adoption of rapid biosensing technologies in the food industry and increase their impact on food safety, public health, and outbreak prevention.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the combined use of magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) and gold nanoparticles (GNPs) presents a highly promising alternative to traditional methods for detecting Listeria monocytogenes in food. This approach is highly sensitive, specific, and capable of identifying low levels of contamination across a variety of food matrices. Its rapid detection capability requiring minimal processing time and limited specialized equipment makes it particularly valuable for applications in the food industry, where timely identification of contamination is essential for preventing foodborne illness outbreaks. Continued research and development in this area may yield even more robust, selective, and versatile detection platforms, further enhancing food safety monitoring and contributing to improved public health protection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A. and W.A.; methodology, M.W., R.F., S.S., K.E.B., A.G. and Y.W.; validation, M.W., R.N., A.G. and E.A.; investigation, M.W., R.F. and R.N.; resources, E.A.; data curation, R.N. and A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, R.N.; writing—review and editing, S.S., K.E.B., Y.W., T.S. and W.A.; supervision, R.F., T.S. and W.A.; project administration, M.W., T.S. and W.A.; funding acquisition, W.A. and T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by grants from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, United States Department of Agriculture (NIFA-USDA), including USDA/NIFA/CBG 2021-38821-34710 and MSU/USDA/NIFA RC113747TU. Additional support was provided through summer DVM student research funding from DHHS/HRSA D34HP00001-35-00, and facility support from the NIH/NIMHD RCMI grant U54MD007585.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge James Franco, Michigan State University, for providing the MNPs and GNPs used in this study. We also thank Nelson Oranye for his assistance with statistical analysis and interpretation, and Tammie B. Hughley for coordinating the summer research program at the Tuskegee University College of Veterinary Medicine.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Listeria Initiative 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/php/surveillance/listeria-initiative.html (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Byrd-Bredbenner, C.; Berning, J.; Martin-Biggers, J.; Quick, V. Food safety in home kitchens: A synthesis of the literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 4060–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, M.R.; Shiptsova, R.; Hamm, S.J. Sales Responses to Recalls for Listeria monocytogenes: Evidence from Branded Ready--to-Eat Meats. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2006, 28, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, D.G.; Koopmans, M.; Verhoef, L.; Duizer, E.; Aidara-Kane, A.; Sprong, H.; Opsteegh, M.; Langelaar, M.; Threfall, J.; Scheutz, F.; et al. Food-borne diseases—The challenges of 20 years ago still persist while new ones continue to emerge. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 139, S3–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahan, C.G.; Hill, C. Listeria monocytogenes: Survival and adaptation in the gastrointestinal tract. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Välimaa, A.-L.; Tilsala-Timisjärvi, A.; Virtanen, E. Rapid detection and identification methods for Listeria monocytogenes in the food chain—A review. Food Control 2015, 55, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, K.; McAuliffe, O. Chapter Seven-Listeria monocytogenes in Foods. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research; Rodríguez-Lázaro, D., Ed.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 86, pp. 181–213. [Google Scholar]

- Ooi, S.T.; Lorber, B. Gastroenteritis due to Listeria monocytogenes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 40, 1327–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ross, W.H.; Scott, V.N.; Gombas, D.E. Listeria monocytogenes: Low levels equal low risk. J. Food Prot. 2003, 66, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLauchlin, J.; Mitchell, R.; Smerdon, W.; Jewell, K. Listeria monocytogenes and listeriosis: A review of hazard characterisation for use in microbiological risk assessment of foods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 92, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, C.; McLauchlin, J.; Aird, H.; Amar, C.; Barker, C.; Dallman, T.; Elviss, N.; Lai, S.; Sadler-Reeves, L. Occurrence of Listeria and Escherichia coli in frozen fruit and vegetables collected from retail and catering premises in England 2018–2019. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 334, 108849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multistate Outbreak of Listeriosis Linked to Frozen Vegetables. 2016. Available online: https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/listeria/outbreaks/frozen-vegetables-05-16/index.html (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- Madad, A.; Marshall, K.E.; Blessington, T.; Hardy, C.; Salter, M.; Basler, C.; Conrad, A.; Stroika, S.; Luo, Y.; Dwarka, A.; et al. Investigation of a multistate outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes infections linked to frozen vegetables produced at individually quick-frozen vegetable manufacturing facilities. J. Food Prot. 2023, 86, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fay, M.L.; Salazar, J.K.; Stewart, D.S.; Khouja, B.A.; Zhou, X.; Datta, A.R. Survival of Listeria monocytogenes on Frozen Vegetables during Long-term Storage at −18 and −10 °C. J. Food Prot. 2024, 87, 100224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, A.R.; Burall, L.S. Diagnosis of Pathogenic Microorganisms Causing Infectious Diseases, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis Ltd: Oxford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, K.; Wang, J.; White, W.L.; Yang, S.; Lu, J. Rapid detection of Listeria monocytogenes in food by biofunctionalized magnetic nanoparticle based on nuclear magnetic resonance. Food Control 2017, 71, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasson, V.; Jacxsens, L.; Luning, P.; Rajkovic, A.; Uyttendaele, M. Alternative microbial methods: An overview and selection criteria. Food Microbiol. 2010, 27, 710–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, A.; Hammerl, J.A.; Boone, I.; Jansen, W.; Fohler, S.; Klein, G.; Dieckmann, R.; Danhouk, S.A. Overview of validated alternative methods for the detection of foodborne bacterial pathogens. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 62, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janudin, A.A.S.; Lim, Y.C.; Ahmed, M.U. Chapter 8—Strategies and challenges of CRISPR/Cas system in detecting foodborne pathogens. In Biosensors for Foodborne Pathogens Detection; Pal, M.K., Ahmed, M.U., Campbell, K., Eds.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 161–193. [Google Scholar]

- Basak, S.; Venkatram, R.; Singhal, R.S. Recent advances in the application of molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) in food analysis. Food Control 2022, 139, 109074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puiu, M.; Bala, C. Microfluidics-integrated biosensing platforms as emergency tools for on-site field detection of foodborne pathogens. TRAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 125, 115831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, H.; Clark, B.; Rhymer, C.; Kuznesof, S.; Hajslova, J.; Tomaniova, M.; Brereton, P.; Frewer, L. A systematic review of consumer perceptions of food fraud and authenticity: A European perspective. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 94, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Li, W.; Xu, H. Advances in magnetic nanoparticles for the separation of foodborne pathogens: Recognition, separation strategy, and application. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 4478–4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustine, R.; Abraham, A.R.; Kalarikkal, N.; Thomas, S. 9-Monitoring and separation of food-borne pathogens using magnetic nanoparticles. In Novel Approaches of Nanotechnology in Food; Grumezescu, A.M., Ed.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 271–312. [Google Scholar]

- Paniel, N.; Noguer, T. Detection of Salmonella in food matrices, from conventional methods to recent aptamer-sensing technologies. Foods 2019, 8, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, C.-Q.; Guo, T.; Hong, L. An automated bacterial concentration and recovery system for pre-enrichment required in rapid Escherichia coli detection. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cai, R.; Gao, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Yue, T. Immunomagnetic separation: An effective pretreatment technology for isolation and enrichment in food microorganisms detection. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 3802–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, H.P.; Jaykus, L.-A. Detection of pathogens in foods: The current state-of-the-art and future directions. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 37, 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharief, S.A.; Caliskan-Aydogan, O.; Alocilja, E. Carbohydrate-coated magnetic and gold nanoparticles for point-of-use food contamination testing. Biosens. Bioelectron. X 2023, 13, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, L.L.; Alocilja, E.C. Carbohydrate ligands on magnetic nanoparticles for centrifuge-free extraction of pathogenic contaminants in pasteurized milk. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 1941–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.-M.; Jeong, K.-B.; Luo, K.; Park, J.-S.; Park, J.-W.; Kim, Y.-R. Paper-based colorimetric detection of pathogenic bacteria in food through magnetic separation and enzyme-mediated signal amplification on paper disc. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1151, 338252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosief, H.O.; Weiss, A.A.; Iyer, S.S. Capture of Uropathogenic, E. coli by Using Synthetic Glycan Ligands Specific for the Pap-Pilus. ChemBioChem 2013, 14, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Boubbou, K.; Gruden, C.; Huang, X. Magnetic Glyco-nanoparticles: A Unique Tool for Rapid Pathogen Detection, Decontamination, and Strain Differentiation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 13392–13393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, L.L.; Karuppuswami, S.; Chahal, P.; Alocilja, E.C. AuNP-RF sensor: An innovative application of RF technology for sensing pathogens electrically in liquids (SPEL) within the food supply chain. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 111, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazy, A.; Nyarku, R.; Faraj, R.; Bentum, K.; Woube, Y.; Williams, M.; Alocilja, E.; Abebe, W. Gold Nanoparticle-Based Plasmonic Detection of Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica, Campylobacter jejuni, and Listeria monocytogenes from Bovine Fecal Samples. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Ye, Q.; Chen, M.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, J.; Pang, R.; Xue, L.; Wang, J.; Zeng, H.; Wu, S.; et al. An ultrasensitive CRISPR/Cas12a based electrochemical biosensor for Listeria monocytogenes detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 179, 113073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myndrul, V.; Yanovska, A.; Babayevska, N.; Korniienko, V.; Diedkova, K.; Jancelewicz, M.; Pogorielov, M.; Iatsunskyi, I. 1D ZnO–Au nanocomposites as label-free photoluminescence immunosensors for rapid detection of Listeria monocytogenes. Talanta 2024, 271, 125641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karnwal, A.; Kumar Sachan, R.S.; Devgon, I.; Devgon, J.; Pant, G.; Panchpuri, M.; Ahmad, A.; Alshammari, M.B.; Hossain, K.; Kumar, G. Gold Nanoparticles in Nanobiotechnology: From Synthesis to Biosensing Applications. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 29966–29982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos Rosero, W.A.; Bueno Barbezan, A.; Daruich de Souza, C.; Chuery Martins Rostelato, M.E. Review of Advances in Coating and Functionalization of Gold Nanoparticles: From Theory to Biomedical Application. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dester, E.; Alocilja, E. Current methods for extraction and concentration of foodborne bacteria with glycan-coated magnetic nanoparticles: A review. Biosensors 2022, 12, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintela, I.A.; de Los Reyes, B.G.; Lin, C.-S.; Wu, V.C. Simultaneous colorimetric detection of a variety of Salmonella spp. in food and environmental samples by optical biosensing using oligonucleotide-gold nanoparticles. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, J.M.; Ross, W.H.; Harwig, J. Health risk assessment of Listeria monocytogenes in Canada. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1996, 30, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norton, D.M. Polymerase Chain Reaction-Based Methods for Detection of Listeria monocytogenes: Toward Real-Time Screening for Food and Environmental Samples. J. AOAC Int. 2019, 85, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Qi, W.; Bai, X.; Xu, H. Cefepime-modified magnetic nanoparticles and enzymatic colorimetry for the detection of Listeria monocytogenes in lettuces. Food Chem. 2023, 409, 135296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łepecka, A.; Zielińska, D.; Szymański, P.; Buras, I.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Assessment of the Microbiological Quality of Ready-to-Eat Salads—Are There Any Reasons for Concern about Public Health? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A.; Allende, A.; Bolton, D.; Chemaly, M.; Davies, R.; Fernández Escámez, P.S.; Snary, E.; Threlfall, J.; Arcella, D.; Wagner, M.; et al. Listeria monocytogenes contamination of ready-to-eat foods and the risk for human health in the EU. EFSA J. 2018, 16, e05134. [Google Scholar]

- Osek, J.; Lachtara, B.; Wieczorek, K. Listeria monocytogenes in foods-From culture identification to whole-genome characteristics. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 2825–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Chon, J.W.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.S.; Choi, D.; Kim, Y.J.; Yim, J.-H.; Moon, J.S.; Seo, K.H. Comparison of Culture, Conventional and Real-time PCR Methods for Listeria monocytogenes in Foods. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2014, 34, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baetsen-Young, A.M.; Vasher, M.; Matta, L.L.; Colgan, P.; Alocilja, E.C.; Day, B. Direct colorimetric detection of unamplified pathogen DNA by dextrin-capped gold nanoparticles. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 101, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 11290-2:2017; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection and Enumeration of Listeria monocytogenes and of Listeria spp.—Part 2: Enumeration Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Confirmed 2022.

- Yang, Y.; Kong, X.; Yang, J.; Xue, J.; Niu, B.; Chen, Q. Rapid Nucleic Acid Detection of Listeria monocytogenes Based on RAA-CRISPR Cas12a System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wu, S.; Ye, Q.; Gu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Lin, R.; Liang, X.; Liu, Z.; Bai, J.; et al. A novel multiplex PCR based method for the detection of Listeria monocytogenes clonal complex 8. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 409, 110475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Huang, J.; Li, W.; Song, Y.; Xiao, F.; Xu, Q.; Xu, H. Portable dual-mode biosensor based on smartphone and glucometer for on-site sensitive detection of Listeria monocytogenes. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 874, 162450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, M.; Chen, G.; Feng, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Q.; Xu, H. Detection of Listeria monocytogenes based on teicoplanin functionalized magnetic beads combined with fluorescence assay. Microchem. J. 2021, 171, 106842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Xiao, F.; Huang, J.; Xu, Q.; Xu, H. Rapid and accurate detection for Listeria monocytogenes in milk using ampicillin-mediated magnetic separation coupled with quantitative real-time PCR. Microchem. J. 2022, 183, 108063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Cui, L.; Song, Y.; Chen, W.; Su, Y.; Chang, W.; Xu, W. Detection of Listeria monocytogenes Using Luminol-Functionalized AuNF-Labeled Aptamer Recognition and Magnetic Separation. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 26338–26344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeğenoğlu Akçinar, H.; Aslim, B.; Torul, H.; Güven, B.; Zengin, A.; Suludere, Z.; Boyaci, I.H.; Tamer, U. Immunomagnetic separation and Listeria monocytogenes detection with surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 50, 1157–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhogail, S.; Suaifan, G.; Zourob, M. Rapid colorimetric sensing platform for the detection of Listeria monocytogenes foodborne pathogen. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 86, 1061–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, W.-B.; Lee, C.-W.; Kim, M.-G.; Chung, D.-H. An antibody–magnetic nanoparticle conjugate-based selective filtration method for the rapid colorimetric detection of Listeria monocytogenes. Anal. Methods 2014, 6, 9129–9135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, H.; Gao, T.; Zheng, Y.; Li, L.; Xu, D.; Zhang, X.; Hou, Y.; Yan, M. Fe3O4@silica nanoparticles for reliable identification and magnetic separation of Listeria monocytogenes based on molecular-scale physiochemical interactions. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 84, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Song, X.; Xu, K.; Chen, H.; Zhao, C.; Li, J. Colorimetric immunoassay for Listeria monocytogenes by using core gold nanoparticles, silver nanoclusters as oxidase mimetics, and aptamer-conjugated magnetic nanoparticles. Microchim. Acta 2018, 185, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanayeva, D.A.; Wang, R.; Rhoads, D.; Erf, G.F.; Slavik, M.F.; Tung, S.; Li, Y. Efficient Separation and Sensitive Detection of Listeria monocytogenes Using an Impedance Immunosensor Based on Magnetic Nanoparticles, a Microfluidic Chip, and an Interdigitated Microelectrode. J. Food Prot. 2012, 75, 1951–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhao, C.; Liu, Y.; Nie, H.; Guo, X.; Song, X.; Xu, K.; Li, J.; Wang, J. A novel fluorescence method for the rapid and effective detection of Listeria monocytogenes using aptamer-conjugated magnetic nanoparticles and aggregation-induced emission dots. Analyst 2020, 145, 3857–3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Li, F.; Li, F.; Xiong, Y.; Xu, H. Vancomycin modified PEGylated-magnetic nanoparticles combined with PCR for efficient enrichment and detection of Listeria monocytogenes. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 247, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormsombut, T.; Mekjinda, N.; Kalasin, S.; Surareungchai, W.; Rijiravanich, P. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles-Enhanced Microarray Technology for Highly Sensitive Simultaneous Detection of Multiplex Foodborne Pathogens. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 2367–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Guo, J.; Liu, J.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, D.; Bai, Y. An aptamer magnetic capture based colorimetric method for rapid and sensitive detection of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2024, 18, 6319–6330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Pang, X.; Li, X.; Bie, X.; Sun, J.; Lu, Y. Rapid and accurate AuNPs-sodium deoxycholate-propidium monoazide-qPCR technique for simultaneous detection of viable Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella. Food Control 2024, 166, 110711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramoglu, G.; Ozalp, V.C.; Arica, M.Y. Aptamer-based magnetic isolation and specific detection system for Listeria monocytogenes from food samples. Microchem. J. 2024, 203, 110892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Xiao, F.; Wang, Z.; Ling, Z.; Xu, H. TBA magnetically functionalized materials combined with biomass-derived fluorescent probe for Listeria monocytogenes detection in a sandwich-like strategy. Food Biosci. 2024, 59, 104049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Chen, Q.; Yang, C.; Ning, Q.; Liu, Z. An enhanced visual detection assay for Listeria monocytogenes in food based on isothermal amplified peroxidase-mimicking catalytic beacon. Food Control 2022, 134, 108721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongmee, P.; Ngernpimai, S.; Srichaiyapol, O.; Mongmonsin, U.; Teerasong, S.; Charoensri, N.; Wongwattanakul, M.; Lulitanond, A.; Kuwatjanakul, W.; Wonglakorn, L.; et al. The Evaluation of a Lateral Flow Strip Based on the Covalently Fixed “End-On” Orientation of an Antibody for Listeria monocytogenes Detection. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 8543–8551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyazit, F.; Arica, M.Y.; Acikgoz-Erkaya, I.; Ozalp, C.; Bayramoglu, G. Quartz crystal microbalance–based aptasensor integrated with magnetic pre-concentration system for detection of Listeria monocytogenes in food samples. Microchim. Acta 2024, 191, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Macho, A.; Eletxigerra, U.; Diez-Ahedo, R.; Merino, S.; Goñi-de-Cerio, F.; Olabarria, G. LAMP based electrochemical sensor for extraction-free detection of Listeria monocytogenes in food samples. Food Control 2024, 163, 110546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiang, Z.; Huang, T.; Xu, Z.; Ma, Q.; Yuan, L.; Soteyome, T. Development and verification of crossing priming amplification on rapid detection of virulent and viable L. monocytogenes: In-depth analysis on the target and further application on food screening. LWT 2024, 204, 116422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.M.; Capobianco, J.A.; Nguyen, S.; Guragain, M.; Liu, Y. High-throughput homogenous assay for the direct detection of Listeria monocytogenes DNA. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).