Interlaboratory Concordance of a Multiplex ELISA for Lyme and Lyme-like Illness Using Australian Samples and Commercial Reference Panels: A Proof-of-Concept Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Used

2.2. Internal and External Controls

2.3. Institutional Review Board Statement

2.4. Statistical Analysis

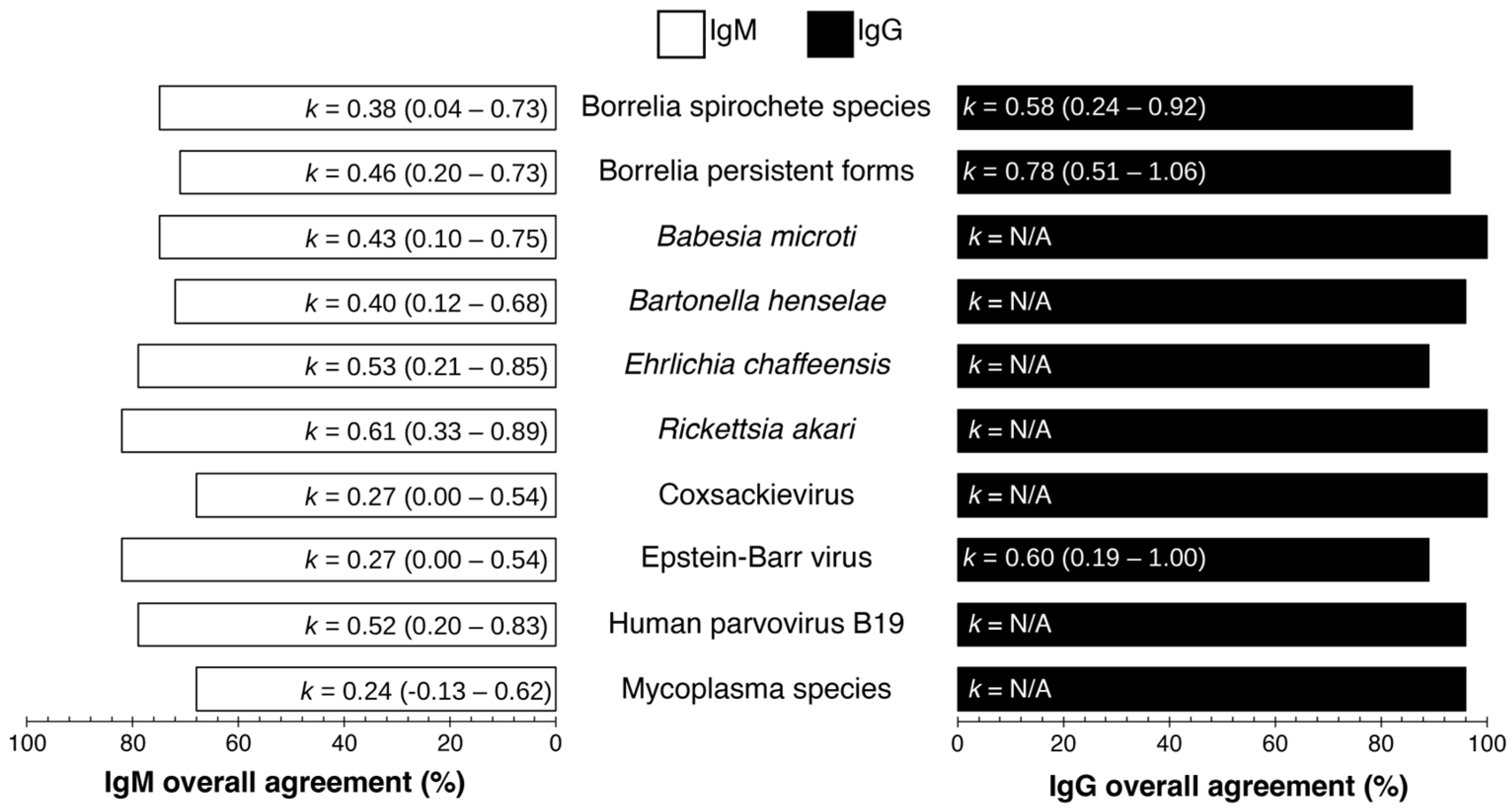

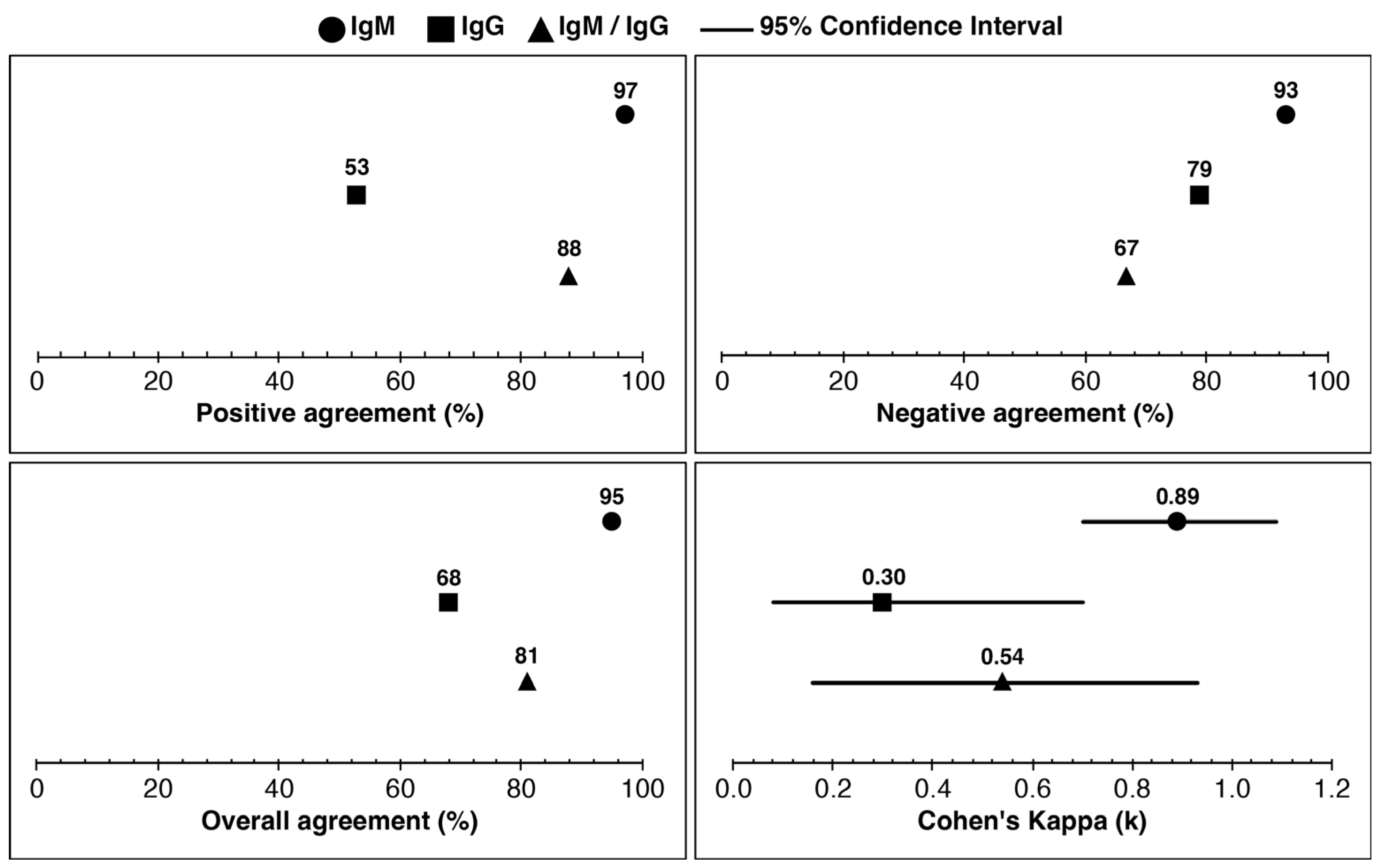

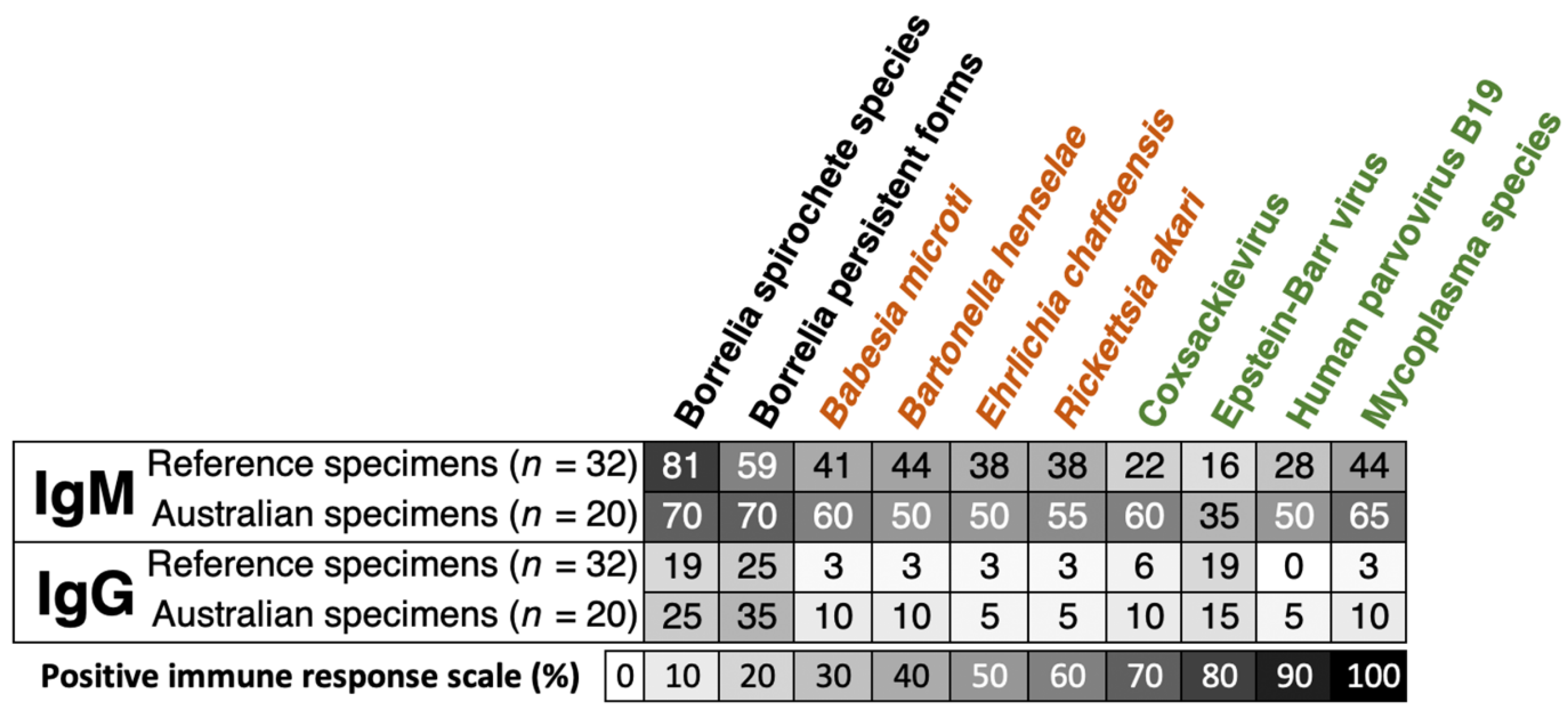

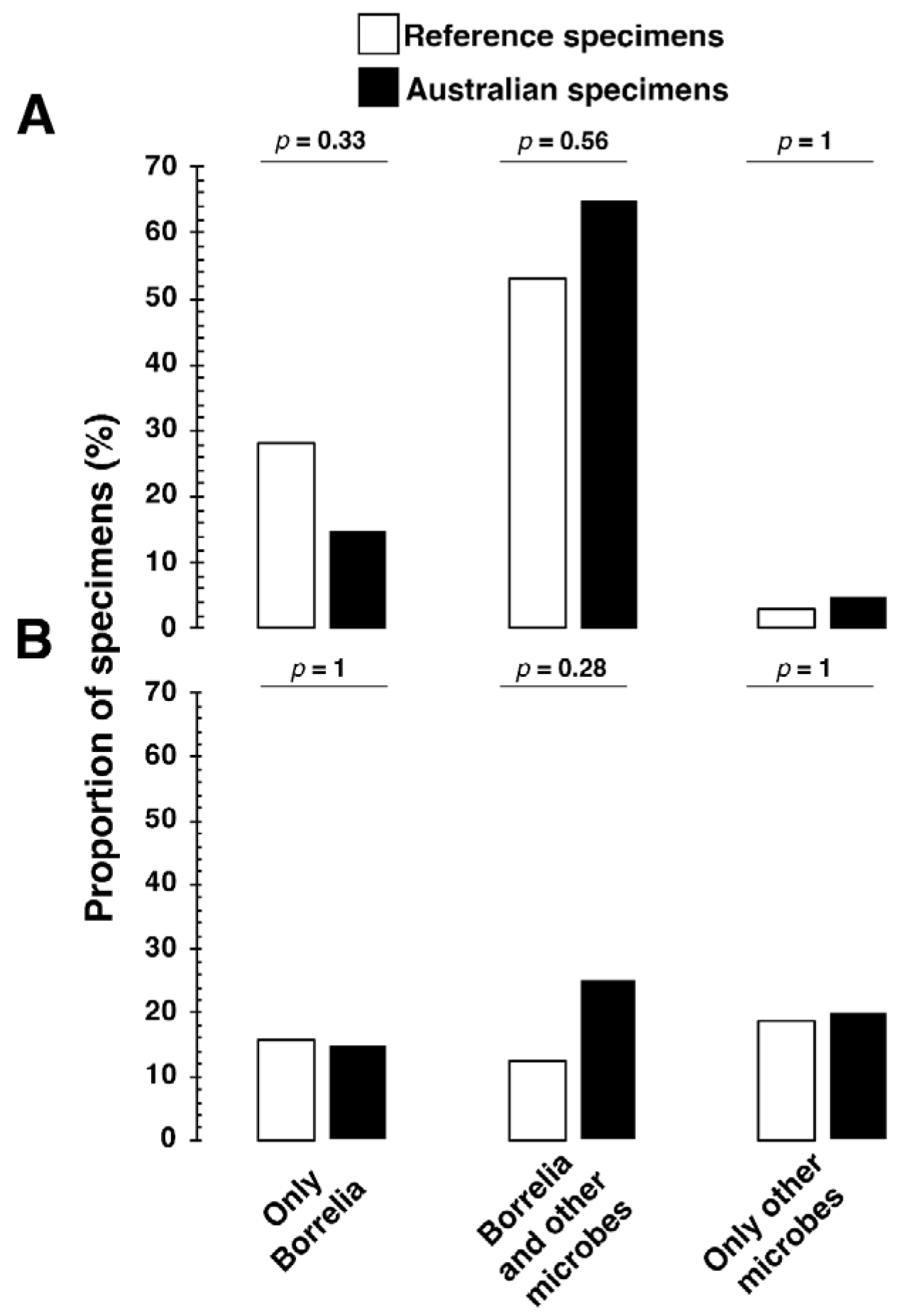

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Assay Performance and Interlaboratory Concordance

4.2. Interpretation of Serological Findings

4.3. Study Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Bb | Borrelia burgdorferi |

| Bb s.l. | Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CV% | Coefficient of Variation |

| DSCATT | Debilitating Symptom Complexes Attributed to Ticks |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| IFA | Immunofluorescence Assay |

| IFU | Instructions for Use |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| IgM | Immunoglobulin M |

| LB | Lyme borreliosis |

| LLD | Lyme-Like Disease |

| NA | Negative Agreement |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Value |

| OA | Overall Agreement |

| ODI | Optical Density Index |

| PA | Positive Agreement |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PPV | Positive Predictive Value |

| QTT | Queensland Tick Typhus |

| RUO | Research Use Only |

| TBD | Tick-Borne Disease |

| WB | Western Blot |

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tickborne Disease Surveillance Data Summary Print. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/data-research/facts-stats/tickborne-disease-surveillance-data-summary.html (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Dong, Y.; Zhou, G.; Cao, W.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, Z.; Yang, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, M.; Fan, Y.; et al. Global Seroprevalence and Sociodemographic Characteristics of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Human Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e007744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugeler, K.J.; Earley, A.; Mead, P.S.; Hinckley, A.F. Surveillance for Lyme Disease After Implementation of a Revised Case Definition—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kugeler, K.J.; Schwartz, A.M.; Delorey, M.J.; Mead, P.S.; Hinckley, A.F. Estimating the Frequency of Lyme Disease Diagnoses, United States, 2010–2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 616–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, A.M.; Kugeler, K.J.; Nelson, C.A.; Marx, G.E.; Hinckley, A.F. Use of Commercial Claims Data for Evaluating Trends in Lyme Disease Diagnosis, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wills, M.C.; Barry, R.D. Detecting the Cause of Lyme Disease in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 1991, 155, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, R.D.; Hudson, B.J.; Shafren, D.R.; Wills, M.C. Lyme Borreliosis in Australia. In Lyme Borreliosis; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1994; pp. 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, B.J.; Barry, R.D.; Shafren, D.R.; Wills, M.C.; Caves, S.; Lennox, V.A. Does Lyme Borreliosis Exist in Australia? J. Spirochetal Tick-Borne Dis. 1994, 1, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Catherine, W.M. Lyme Borreliosis, the Australian Perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, B.J.; Stewart, M.; Lennox, V.A.; Fukunaga, M.; Yabuki, M.; Macorison, H.; Kitchener-Smith, J. Culture-positive Lyme Borreliosis. Med. J. Aust. 1998, 168, 500–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, R.C.; Doggett, S.L.; Munro, R.; Ellis, J.; Avery, D.; Hunt, C.; Dickeson, D. Lyme Disease: A Search for a Causative Agent in Ticks in South–Eastern Australia. Epidemiol. Infect. 1994, 112, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collignon, P.J.; Lum, G.D.; Robson, J.M. Does Lyme Disease Exist in Australia? Med. J. Aust. 2016, 205, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalada, M.J.; Stenos, J.; Bradbury, R.S. Is There a Lyme-like Disease in Australia? Summary of the Findings to Date. One Health 2016, 2, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gofton, A.W.; Blasdell, K.R.; Taylor, C.; Banks, P.B.; Michie, M.; Roy-Dufresne, E.; Poldy, J.; Wang, J.; Dunn, M.; Tachedjian, M.; et al. Metatranscriptomic Profiling Reveals Diverse Tick-borne Bacteria, Protozoans and Viruses in Ticks and Wildlife from Australia. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, e2389–e2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R.H.; Bradbury, R.; Cullen, J.S. Lyme Disease on the NSW Central Coast. Med. J. Aust. 1986, 145, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrossin, I. Lyme Disease on the NSW South Coast. Med. J. Aust. 1986, 144, 724–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallman, N. Lyme Borreliosis—A Case Report for Queensland. Commun. Dis. Intell. 1987, 11, 1–20. Available online: https://ojs.cdi.cdc.gov.au/index.php/cdi/article/view/3037 (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Maud, C.; Berk, M. Neuropsychiatric Presentation of Lyme Disease in Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2013, 47, 397–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.D. A Description of ‘Australian Lyme Disease’ Epidemiology and Impact: An Analysis of Submissions to an Australian Senate Inquiry. Intern. Med. J. 2018, 48, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.S.; Liu, S.; Cruz, I.D.; Poruri, A.; Maynard, R.; Shkilna, M.; Korda, M.; Klishch, I.; Zaporozhan, S.; Shtokailo, K.; et al. Line Immunoblot Assay for Tick-Borne Relapsing Fever and Findings in Patient Sera from Australia, Ukraine and the USA. Healthcare 2019, 7, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.; Fracp, J.G.; Patel, A.; Watt, G.; Cripps, A.; Clancy, R. Lyme Arthritis in the Hunter Valley. Med. J. Aust. 1982, 1, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Senate Community Affairs Committee. Growing Evidence of an Emerging Tick-Borne Disease That Causes a Lyme-like Illness for Many Australian Patients. 2016. Available online: https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Community_Affairs/Lymelikeillness45/Final_Report (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Haisman-Welsh, R.; Marshall, C. Debilitating Symptom Complexes Attributed to Ticks (DSCATT) Clinical Pathway 2020; Australian Government, Department of Health: Canberra, Australia, 2020.

- Schnall, J.; Oliver, G.; Braat, S.; Macdonell, R.; Gibney, K.B.; Kanaan, R.A. Characterising DSCATT: A Case Series of Australian Patients with Debilitating Symptom Complexes Attributed to Ticks. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2022, 56, 974–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senate Community Affairs References Committee. Access to Diagnosis and Treatment for People in Australia with Tick-Borne Diseases; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2025; p. 98.

- Graves, S.R.; Stenos, J. Tick-borne Infectious Diseases in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2017, 206, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.L. Clinical Manifestations and Treatment of Lyme Disease. Clin. Lab. Med. 2015, 35, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, D.; Sleigh, A.; Ritchie, S. Ross River Virus Transmission, Infection, and Disease: A Cross-Disciplinary Review. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001, 14, 909–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, S.R.; Dwyer, B.; McColl, D.; McDade, J. Flinders Island Spotted Fever: A Newly Recognised Endemic Focus of Tick Typhus in Bass Strait: Part 2. Serological Investigations. Med. J. Aust. 1991, 154, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinn, T.G.; Sowden, D. Queensland Tick Typhus. Aust. N. Z. J. Med. 1998, 28, 824–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, D.J.; King, G.; Dwyer, B. Fatal Queensland Tick Typhus. J. Infect. Dis. 1990, 162, 779–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.; Armstrong, M.; Graves, S.; Hajkowicz, K. Rickettsia australis and Queensland Tick Typhus: A Rickettsial Spotted Fever Group Infection in Australia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 97, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fergie, B.; Basha, J.; McRae, M.; McCrossin, I. Queensland Tick Typhus in Rural New South Wales. Australas. J. Dermatol 2017, 58, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branda, J.A.; Body, B.A.; Boyle, J.; Branson, B.M.; Dattwyler, R.J.; Fikrig, E.; Gerald, N.J.; Gomes-Solecki, M.; Kintrup, M.; Ledizet, M.; et al. Advances in Serodiagnostic Testing for Lyme Disease Are at Hand. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 66, 1133–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, S.J.; Tschaepe, M.I.; Wilson, K.M. Investigation of the Performance of Serological Assays Used for Lyme Disease Testing in Australia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, K.; Jokiranta, T.S.; Filén, S.; Gilbert, L. Assessing the Need for Multiplex and Multifunctional Tick-Borne Disease Test in Routine Clinical Laboratory Samples from Lyme Disease and Febrile Patients with a History of a Tick Bite. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriläinen, L.; Herranen, A.; Schwarzbach, A.; Gilbert, L. Morphological and Biochemical Features of Borrelia burgdorferi Pleomorphic Forms. Microbiology 2015, 161, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriläinen, L.; Brander, H.; Herranen, A.; Schwarzbach, A.; Gilbert, L. Pleomorphic Forms of Borrelia burgdorferi Induce Distinct Immune Responses. Microbes Infect. 2016, 18, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.; Zhang, N.; Wooten, R.M. Borrelia burgdorferi Elicited-IL-10 Suppresses the Production of Inflammatory Mediators, Phagocytosis, and Expression of Co-Stimulatory Receptors by Murine Macrophages and/or Dendritic Cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgia, R.; Piazzetta, C.; Cinco, M. Cystic Forms of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato: Induction, Development, and the Role of RpoS. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2002, 114, 574–579. [Google Scholar]

- Murgia, R.; Cinco, M. Induction of Cystic Forms by Different Stress Conditions in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. 2004, 112, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, A.B. Plaques of Alzheimer’s Disease Originate from Cysts of Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme Disease Spirochete. Med. Hypotheses 2006, 67, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alban, P.; Johnson, P.; Nelson, D. Serum-Starvation-Induced Changes in Protein Synthesis and Morphology of Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbiology 2000, 146, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, A.B. Spirochetal Cyst Forms in Neurodegenerative Disorders,…Hiding in Plain Sight. Med. Hypotheses 2006, 67, 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miklossy, J.; Kasas, S.; Zurn, A.D.; McCall, S.; Yu, S.; McGeer, P.L. Persisting Atypical and Cystic Forms of Borrelia Burgdorferi and Local Inflammation in Lyme Neuroborreliosis. J. Neuroinflamm. 2008, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.J.; Powers, M.L.; Gronowski, K.S.; Gronowski, A.M. Human Tissue Ownership and Use in Research: What Laboratorians and Researchers Should Know. Clin. Chem. 2010, 56, 1675–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Diest, P.J.; Savulescu, J. For and against: No Consent Should Be Needed for Using Leftover Body Material for Scientific Purposes. BMJ 2002, 325, 648–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, G.F.; Lynn, F.; Meade, B.D. Use of Coefficient of Variation in Assessing Variability of Quantitative Assays. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2002, 9, 1235–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, P.F.; Petrie, A. Method Agreement Analysis: A Review of Correct Methodology. Theriogenology 2010, 73, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater Reliability: The Kappa Statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-Y. Statistical Notes for Clinical Researchers: Chi-Squared Test and Fisher’s Exact Test. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2017, 42, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommendations for Test Performance and Interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 1995, 44, 590–591. [Google Scholar]

- Golovchenko, M.; Opelka, J.; Vancova, M.; Sehadova, H.; Kralikova, V.; Dobias, M.; Raska, M.; Krupka, M.; Sloupenska, K.; Rudenko, N. Concurrent Infection of the Human Brain with Multiple Borrelia Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempereur, L.; Shiels, B.; Heyman, P.; Moreau, E.; Saegerman, C.; Losson, B.; Malandrin, L. A Retrospective Serological Survey on Human Babesiosis in Belgium. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, e1–e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, E.; Billeter, S.A.; Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Chomel, B.B.; Raoult, D. Potential for Tick-Borne Bartonelloses. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010, 16, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, N.; Bloch, K.C.; McBride, J.W. Human Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis. Clin. Lab. Med. 2010, 30, 261–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.-B.; Na, R.-H.; Wei, S.-S.; Zhu, J.-S.; Peng, H.-J. Distribution of Tick-Borne Diseases in China. Parasites Vectors 2013, 6, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koetsveld, J.; Tijsse-Klasen, E.; Herremans, T.; Hovius, J.W.; Sprong, H. Serological and Molecular Evidence for Spotted Fever Group Rickettsia and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato Co-Infections in The Netherlands. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2016, 7, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, N.A.; Richardson, C.S. Posttreatment Lyme Disease Syndrome and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Comparison of Pathogenesis. Chronic Dis. Transl. Med. 2023, 9, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundt, E.C.; Beatty, D.C.; Stegall-Faulk, T.; Wright, S.M. Possible Tick-Borne Human Enterovirus Resulting in Aseptic Meningitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 3471–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, J.K.S. The Role of Enterovirus in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. J. Clin. Pathol. 2005, 58, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavletic, A.J.; Marques, A.R. Early Disseminated Lyme Disease Causing False-Positive Serology for Primary Epstein-Barr Virus Infection: Report of 2 Cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 65, 336–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koester, T.M.; Meece, J.K.; Fritsche, T.R.; Frost, H.M. Infectious Mononucleosis and Lyme Disease as Confounding Diagnoses: A Report of 2 Cases. Clin. Med. Res. 2018, 16, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Pablos, M.; Paiva, B.; Montero-Mateo, R.; Garcia, N.; Zabaleta, A. Epstein-Barr Virus and the Origin of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 656797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghoff, W. Chronic Lyme Disease and Co-Infections: Differential Diagnosis. Open Neurol. J. 2012, 6, 158–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, J.R.; Gough, J.; Richards, S.C.M.; Main, J.; Enlander, D.; McCreary, M.; Komaroff, A.L.; Chia, J.K. Antibody to Parvovirus B19 Nonstructural Protein Is Associated with Chronic Arthralgia in Patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eskow, E.; Adelson, M.E.; Rao, R.-V.S.; Mordechai, E. Evidence for Disseminated Mycoplasma Fermentans in New Jersey Residents with Antecedent Tick Attachment and Subsequent Musculoskeletal Symptoms. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2003, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.M.; Janigian, R.H. Mycoplasma Pneumoniae: The Other Masquerader. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013, 131, 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, G.L.; Nicolson, N.L.; Haier, J. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Patients Subsequently Diagnosed with Lyme Disease Borrelia Burgdorferi: Evidence for Mycoplasma Species Coinfections. J. Chronic Fatigue Syndr. 2011, 14, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijs, J.; Nicolson, G.L.; Becker, P.D.; Coomans, D.; Meirleir, K.D. High Prevalence of Mycoplasma Infections among European Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Patients. Examination of Four Mycoplasma Species in Blood of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Patients. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2002, 34, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seriburi, V.; Ndukwe, N.; Chang, Z.; Cox, M.E.; Wormser, G.P. High Frequency of False Positive IgM Immunoblots for Borrelia burgdorferi in Clinical Practice. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantos, P.M.; Rumbaugh, J.; Bockenstedt, L.K.; Falck-Ytter, Y.T.; Aguero-Rosenfeld, M.E.; Auwaerter, P.G.; Baldwin, K.; Bannuru, R.R.; Belani, K.K.; Bowie, W.R.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and American College of Rheumatology (ACR): 2020 Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment of Lyme Disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 72, e1–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molins, C.R.; Delorey, M.J.; Replogle, A.; Sexton, C.; Schriefer, M.E. Evaluation of bioMérieux’s Dissociated Vidas Lyme IgM II and IgG II as a First-Tier Diagnostic Assay for Lyme Disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 1698–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, C.A.; Budvytyte, L.N.; Press, C.; Zhou, L.; McLeod, R.; Maldonado, Y.; Montoya, J.G.; Contopoulos-Ioannidis, D.G. Evaluation of Three Point-of-Care Tests for Detection of Toxoplasma Immunoglobulin IgG and IgM in the United States: Proof of Concept and Challenges. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2018, 5, ofy215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricou, V.; Vu, H.T.; Quynh, N.V.; Nguyen, C.V.; Tran, H.T.; Farrar, J.; Wills, B.; Simmons, C.P. Comparison of Two Dengue NS1 Rapid Tests for Sensitivity, Specificity and Relationship to Viraemia and Antibody Responses. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herremans, M.; Vermeulen, M.J.; Van de Kassteele, J.; Bakker, J.; Schellekens, J.F.P.; Koopmans, M.P.G. The Use of Bartonella Henselae-Specific Age Dependent IgG and IgM in Diagnostic Models to Discriminate Diseased from Non-Diseased in Cat Scratch Disease Serology. J. Microbiol. Methods 2007, 71, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Yang, X.; Xiu, B.; Qie, S.; Dai, Z.; Chen, K.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, L.; Nicholson, R.A.; Wang, G.; et al. IgG, IgM and IgA Antibodies against the Novel Polyprotein in Active Tuberculosis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waddell, L.A.; Greig, J.; Mascarenhas, M.; Harding, S.; Lindsay, R.; Ogden, N. The Accuracy of Diagnostic Tests for Lyme Disease in Humans, A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of North American Research. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodym, P.; Kurzová, Z.; Berenová, D.; Pícha, D.; Smíšková, D.; Moravcová, L.; Malý, M. Serological Diagnostics of Lyme Borreliosis: Comparison of Universal and Borrelia Species-Specific Tests Based on Whole-Cell and Recombinant Antigens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, e00601-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyer, P.H.; Lenormand, C.; Jaulhac, B.; Talagrand-Reboul, E. Human Co-Infections between Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. and Other Ixodes-Borne Microorganisms: A Systematic Review. Pathogens 2022, 11, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehhaghi, M.; Panahi, H.K.S.; Holmes, E.C.; Hudson, B.J.; Schloeffel, R.; Guillemin, G.J. Human Tick-Borne Diseases in Australia. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska-Koszko, I.; Kwiatkowski, P.; Sienkiewicz, M.; Kowalczyk, M.; Kowalczyk, E.; Dołęgowska, B. Cross-Reactive Results in Serological Tests for Borreliosis in Patients with Active Viral Infections. Pathogens 2022, 11, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grąźlewska, W.; Holec-Gąsior, L. Antibody Cross-Reactivity in Serodiagnosis of Lyme Disease. Antibodies 2023, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torina, A.; Villari, S.; Blanda, V.; Vullo, S.; La Manna, M.P.; Shekarkar Azgomi, M.; Di Liberto, D.; de la Fuente, J.; Sireci, G. Innate Immune Response to Tick-Borne Pathogens: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms Induced in the Hosts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowicz, M.; Reiter, M.; Gamper, J.; Stanek, G.; Stockinger, H. Persistent Anti-Borrelia IgM Antibodies without Lyme Borreliosis in the Clinical and Immunological Context. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e01020-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalish, R.A.; McHugh, G.; Granquist, J.; Shea, B.; Ruthazer, R.; Steere, A.C. Persistence of Immunoglobulin M or Immunoglobulin G Antibody Responses to Borrelia burgdorferi 10–20 Years after Active Lyme Disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 33, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, H.A.T.; van den Bogaard, A.E.; Nohlmans, M.K.E. Evaluation of Fifteen Commercially Available Serological Tests for Diagnosis of Lyme Borreliosis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1999, 18, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguero-Rosenfeld, M.E.; Nowakowski, J.; Bittker, S.; Cooper, D.; Nadelman, R.B.; Wormser, G.P. Evolution of the Serologic Response to Borrelia burgdorferi in Treated Patients with Culture-Confirmed Erythema Migrans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatz, M.; Golestani, M.; Kerl, H.; Müllegger, R.R. Clinical Relevance of Different IgG and IgM Serum Antibody Responses to Borrelia burgdorferi after Antibiotic Therapy for Erythema Migrans: Long-Term Follow-up Study of 113 Patients. Arch. Dermatol. 2006, 142, 862–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsner, R.A.; Hastey, C.J.; Baumgarth, N. CD4+ T Cells Promote Antibody Production but Not Sustained Affinity Maturation during Borrelia burgdorferi Infection. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total Number of Samples (n) | 53 |

| Reference serum samples from SeraCare Life Sciences Inc. and Plasma Services Group (n) | 33 [Includes two samples labeled as AU6 and AU31 (Table S1), which are identical. These samples were tested in the presence and absence of 30% Glycerol] |

| Reference serum samples from Australia (n) | 20 |

| Common serum samples shared between the independent labs from the total number of samples (n) | 28 (22 samples had tested seropositive for IgM and/or IgG or both for Lyme borreliosis) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garg, K.; Villavicencio-Aguilar, F.; Solano-Rivera, F.; Gilbert, L. Interlaboratory Concordance of a Multiplex ELISA for Lyme and Lyme-like Illness Using Australian Samples and Commercial Reference Panels: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1281. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121281

Garg K, Villavicencio-Aguilar F, Solano-Rivera F, Gilbert L. Interlaboratory Concordance of a Multiplex ELISA for Lyme and Lyme-like Illness Using Australian Samples and Commercial Reference Panels: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1281. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121281

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarg, Kunal, Fausto Villavicencio-Aguilar, Flora Solano-Rivera, and Leona Gilbert. 2025. "Interlaboratory Concordance of a Multiplex ELISA for Lyme and Lyme-like Illness Using Australian Samples and Commercial Reference Panels: A Proof-of-Concept Study" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1281. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121281

APA StyleGarg, K., Villavicencio-Aguilar, F., Solano-Rivera, F., & Gilbert, L. (2025). Interlaboratory Concordance of a Multiplex ELISA for Lyme and Lyme-like Illness Using Australian Samples and Commercial Reference Panels: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Pathogens, 14(12), 1281. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121281