Abstract

When approached through the theoretical lenses of canonical literature and the reductionist Western science of settler colonialism, climate crisis discourse grapples with a conception of apocalypse wherein catastrophe and hopelessness engender eco-anxiety and a sense of environmental nihilism. Drawing from the works of Jessica Hernandez, Sherri Mitchell, Robin Wall Kimmerer, and others, “What Would the Mushrooms Say?”, both as a class and concept, envisions a healing-centered, interdisciplinary approach to climate discourse in learning spaces, one that centers the theoretical and practical applications of an Indigenous science and mythology to flip the dominant narratives we tell about the dystopic dead ends of climate change, extinctions, anthropocentric hierarchies, and other events predictive of end times. Instead of only reckoning with white settler colonialism’s false promises of technocratic off-planet societies, students interact with a multiplicity of apocalypses and possibilities found in Indigenous cosmologies, mythologies, epistemologies, and speculative fiction of Indigenous, Indigequeer, queer writers of color, and the natural world. Posited as an exemplar text, Amanda Strong’s animated short film Biidaaban is discussed in terms of its instructional potential and depiction of Indigenous ways of relating, as kin, to human and nonhuman alike when speculating about futurity. “What Would the Mushrooms Say?” calls for slowing down and embracing the natural world as a teacher from whom we learn and speculate alongside. It suggests as a lifelong practice ways of relating to our planet and engaging with the climate discourse that interrupt a legacy of white settler colonialist eco-theorizing and action determined to dominate and subdue the natural world. In conclusion, this project documents the emergence of students’ shifting perspectives and their explorations of newfound possibilities within learning spaces where constructive hope rather than despair dominates climate discourse.

Why do we focus alwayson the destructionand not the regeneration?We reach for talesassuring us of immortalityyet we refuse to readthe life right in front of us.-Jeff Fernside, “New Channel” (Fernside 2016)

“We’re All Gonna Die!”…Or, Are We?

When my students in my ecohumanities1 class, “What Would the Mushrooms Say?”2, first encounter the topics of climate science and climate justice in their science classes, they succumb to a sense of environmental nihilism and, as their meme illustrates (Figure 1), a foreboding existential despair. Their eco-anxiety3 speaks to the potent and crushing sense of doom topics of this sort engender. With each car ride, every plastic bottle not recycled, and each unfinished slice of pizza that misses the compost bin, we inch that much closer to our demise, our singular apocalyptic ending. We are, in other words, living out Adam McKay’s film Don’t Look Up (2022), albeit on a less catastrophic and far more syncopated scale. Perhaps recent advances in privatized space travel suggest the potential for a way out when the time comes, a one-way ticket to galactic and interplanetary colonies and post-apocalyptic survivance. If humankind is indeed plummeting, irrevocably, towards its certain demise, the Earth becoming hostile and inhabitable, putting all our proverbial eggs in tech-centric solutions and off-planet escapes would seem wise. Yet, McKay’s film warns, an escape plan reliant on technocrats’ sleek machines, utopic destinations, and money-making ventures risks replicating the wounds of wealth disparity. Within the context of the film, this means a select group—namely, wealthy white people who shrug off science and solidarity to pursue rugged individualism and financial gain—enjoy the opportunity to live while everyone else, everything else, is left to die as an asteroid roughly the size of 105 football fields hurls towards the doomed planet. A work of satire, Don’t Look Up denies the shuttle of elites their happy ending in an ultimate privilege check, and—spoiler alert—humans go extinct. Thus, in staring down the looming apocalypse, it seems we would be remiss to put all our faith in a singular technocratic savior, whose congregation subscribes first and foremost to the gospel of capitalism. Yet, if humankind’s futurity necessarily entails escaping a ruined planet, what other viable options do we have?

Figure 1.

Student-created meme posted to a student-run Instagram account for school-inspired memes.

Ariel King, on the other hand, prefers a far less pessimistic perspective. “With so much heavy and bleak news surrounding the climate crisis, it’s more important than ever to share stories of positive solutions, environmental justice, and climate optimism to reignite our desire to take action to protect people and the planet” (00:01:07). A podcast “dedicated to sharing stories about climate solutions and justice grounded in intersectionality, optimism, and joy”, King’s The Joy Report reframes climate dialogue, interrupting pervasive feelings of despair,4 and cultivating instead an environmental optimism that echoes the teachings and practices of Indigenous scientists Robin Wall Kimmerer (Citizen Potawatomi Nation), Sherri Mitchell (Penawahpskek), and Jessica Hernandez (Binniza and Maya Ch’arti’). Unlike the mechanized, sleek solutions technocrats propose and McKay’s film mocks, the Indigenous scientists and intersectional environmentalists find the promise of possibility, survivance, and futurity in restoring our relationship with Mother Earth and embracing nature as teacher. The Indigenous, overlapping eco-epistemologies detailed in their respective works can and do reframe the climate dialogue in my classroom when, following the examples set by Kimmerer, Mitchell, Hernandez, and others, we listen to the lessons of mushrooms, mythology, and multispecies entanglements rather than frantically planning a galactic escape from a doomed planet and “crushing existential despair”.

Concerns about the climate crisis are hardly unfounded, however, and remain urgently relevant even in those learning spaces that approach the discourse through the holistic perspective of the Indigenous scientist noted above. “The extinction crisis is very real”, writes Deborah Bird Rose. “Rates of extinction are perhaps ten thousand times the background rate” (Rose 2015a, p. G52). Rose describes types of extinction beyond those measured in terms of “presumptive absence” (Rose 2015a, p. G52). Extinction cascades and vortexes, massive yet subtle slippages that cause “relationships to unravel, mutualities to falter, dependance [to become] a peril rather than a blessing, and whole worlds of knowledge and practice to diminish” (Rose 2015a, p. G52). Dire and hopeless, indeed, seems the continuation of life as we know it, but what if our prophecies foretelling of inevitable sudden mass extinctions and a singular apocalypse are overly reductive? Perhaps a hyper-focus on crushing existential despair and popular media’s foreboding narrative of end-times narrowly roots climate action discourse in the anthropocentric assumption that moving off-planet is unavoidable. What if, as Rose learned through observing the relationship between Australia’s angiosperms and flying foxes, “in the midst of terrible destruction, life finds a way to flourish” (Rose 2015a, p. G61)?5

Rose’s emphasis on the Aboriginal aesthetic of “shimmer”, its historical place within Aboriginal rituals and art, and its invitation to join vibrant, multispecies worlds counters the mythology mirroring post-truth rhetoric that often dictates how we engage with climate science and climate justice. In “Entries into the Forest”, Charles Goodrich champions “multiple ways of knowing”, observing, experiencing, and talking about nature (Goodrich 2016, p. 11). He writes:

Goodrich, in his introduction to Forest Under Story, speaks convincingly to the efficacy of an interdisciplinary ecohumanities approach to grappling with environmental science and one that heeds the call to “build dialogical bridges between knowledge systems: between ecological sciences and the humanities, between Western and other knowledge systems” (Rose 2015b, p. 1). Yet, the blending of ideas when limited to humans’ imaginings does not do enough to decenter the anthro in these conversations, thus maintaining an oppressive and exclusive hierarchy that some—Adam McKay, for instance—would argue landed us in this species-ending climate mess in the first place.Storytelling and poetry, observation and experiment, myth and mathematics are all authentic windows into the world. There is an unusual richness and joy in the community of the humanities and sciences, in the coming together of insights from many different perspectives and disciplines.(qtd. in Brodie et al. 2016, p. 11)

I contend that a healing-centered6 ecohumanities pedagogy and praxis offers a nuanced, critical alternative to a traditional curriculum and instruction grounded in the reductionist science of settler colonialism. Instead of building from the myth and monolith of a doomed anthropogenic age, “What Would the Mushrooms Say?”, as a class and concept, in a move to soothe eco-anxiety and disrupt environmental nihilism, invites learning communities to stop, look, and listen to “Indigenous voices, perspectives and lived experiences”, or what Hernandez calls “Indigenous science because they embody [Indigenous] ways of knowing that are rooted from the ancestral knowledge and valid sciences” (Hernandez 2022, p. 13).7 In addition to Hernandez’s work and other contributions from Indigenous scientists, the ecohumanities approach I suggest embraces the nonhuman as teacher, looking “to our teachers among the other species for guidance” (Kimmerer 2013, p. 9). When we “learn to listen” to the story plants can tell us about rekindling our relationship with Mother Earth, as Kimmerer suggests, we engage with a different type of mythos, one that sets out not to erase other ways of thinking and being, but honor the storytellers with the most experience—Indigenous peoples, those within diasporas, and our nonhuman kin, from flora to fauna to the feminist lessons of marine mammals and mycelium’s promise of the “possibility of life in capitalist ruins” (Tsing 2015). Conceptually and as a class, “What Would the Mushrooms Say?” centers Indigenous, Black, and nature’s speculative fiction as one mode for reorienting mythos in learning spaces and disrupting a settler colonialist mindset that, through its emphasis on individualism and the privileging of Western science, forecloses the optimistic interspecies futures. Within this paper, I focus on one particular piece of Indigenous speculative fiction—Anishinaabe director Amanda Strong’s short film Biidaaban (The Dawn Comes) (Strong 2018)—and its potency as an exemplar text for the learning and doing of a healing-centered ecohumanities. Lastly, I document the emergence of shifting perspectives and explorations of newfound possibilities within learning spaces where constructive hope8 rather than despair dominates climate discourse.

The Sacred Instruction of Indigenous Science

Earlier, I raised a critical eyebrow at a singular, cataclysmic outcome which quite literally dead ends in a grand finale for humankind and, depending on the fictional depiction, nonhuman species as well. Not only does this end point culminate in climate catastrophe and mass extinction, but it relies on two interdependent myths. First, our bleak obsession with environmental nihilism, and secondly, “the myth of separation” (Mitchell 2018, p. 46). Fueled by “the Western idea of rugged individualism”, the myth of separation lies in the illusion that humans exist at the top of a naturally occurring hierarchy, thereby separating us from the nonhuman and, as slavery and genocide ideologies prove, from people deemed less than human. Instead of living communally, we pursue individual aims above all else, becoming “fully invested into the capitalist model that places profit above all other considerations, even the survival of our own species” (Mitchell 2018, p. 47). Off-planet expeditions, interplanetary imperialism, extraction and human exploitation to mine more lithium for alternatives to fossil fuels, and other colonialist projects monopolize conversations about solutions to climate change, with the clear caveat that these projects do not include everyone. “We have a name for this madness”, remarks Mitchell. “In our mythology…We call it the dance of the Cannibal Giant” (Mitchell 2018, p. 47). In Wabanaki mythology, Mitchell’s ancestral mythos, the cannibalistic spirit, Kiwawk, slumbers undisturbed in the depths of the forest, protected from human disturbances, until Mother Earth awakens him to “feed on the greed, excess, and unchecked consumption” of mankind run amok (ibid.). Once awake, Kiwawk lures humanity into a hypnotic, frenzied dance of “mindless consumption”, the pace quickening as we gyrate towards our demise and Mother Earth towards her opportunity to replenish (ibid., p. 48). Known to other Native cultures by other names, the Cannibal Giant is, according to Mitchell’s elders, awake. “There is only one way to stop this dance with Kiwawk and put him back to sleep, and that is for us to wake up” (ibid.).

The “sacred instruction” Mitchell intimates in her book echoes the lessons imparted by Indigenous scientists Kimmerer and Hernandez in their respective works. All three draw from ancestral tradition passed down from one generation to the next via the stories and myths told as teaching moments in a long lineage of “inherited knowledge” (Hernandez 2022, p. 3). The story of the Cannibal Giant implores a sense of urgency, a call to action, a chance at futurity, if we cease our deadly dance with consumption and reject the myth of separation. Creation stories depict ancestors as “being made from the earth, our lands” (ibid., p. 72) and thus serve as “a source of identity and orientation to the world” (Kimmerer 2013, p. 7). As Indigenous cosmologies, these myths describe symbiotic, reciprocal interspecies enmeshments, “an alchemy … coupled with deep gratitude”, an equilibrium. “If we listen closely”, writes Mitchell, “we can hear this creation song echoing in our bones”, tapping into a rhythm balanced “with the harmonic frequencies that surround us” (2018, p. 5). Indeed, the interrelated notions of “listening” and “balance” are key lessons across Indigenous science and Indigenous speculative fiction, the latter of which I will address in a separate section. They are lessons, Mitchell contends, deeply embodied by ancestral knowledge.

If Mitchell’s elders are correct and Kiwawk is awake, then we are indeed experiencing a state of imbalance, the harmonious natural rhythms thrown off key by a discordant note struck by humans in our mad dash to subdue, dominate, and consume the world around us.Our ancestors…understood the language of the land and the waters. They spoke to the plants and animals. They heard the subtle voice of creation and they saw the interconnectedness among all living things. As a result, they worked in concert with the natural rhythms that surrounded them, knowing that their lives were tied inextricably to all living beings and to the living earth as well. Thus, the stories they wove and the lives they created were balanced and harmonious.(2018, p. 14)

This state, according to Indigenous speculative fiction writers Grace L. Dillon (Anishinaabe) and Joshua Whitehead (Oji-Cree), constitutes a “Native Apocalypse.” Like the Cannibal Giant, the Native Apocalypse appears in Indigenous mythology, fiction, science, and art in various forms. However, what remains true across this abundant body of work is, as Whitehead aptly describes, the “Apocalypse as ellipses”, that is, the notion of the Native Apocalypse as always-already occurring, especially for Indigenous peoples (Whitehead 2020, p. 9). “The idea that disaster will come is not new for indigenous peoples; genocidal disaster has already come, decades and centuries ago, and has not stopped” Donna Haraway notes (Bubandt et al. 2015, p. M44). Yet, unlike the cataclysmic doomsday of a singular apocalypse, the sort of myth that I and others have argued engenders eco-anxiety and, according to my students, existential despair, the imbalance of Native Apocalypses proffers hope. “Imbalance further implies a state of extremes, but within those extremes lies a middle ground…the state of balance, one of difference and provisionally, a condition of resistance and survival” (Dillon 2012, p. 9).

Nature remains humankind’s most steadfast and knowledgeable teacher in our efforts to germinate collective futurity in the spaces of decay and ruin, thus restoring balance and returning Kiwawk to an assured quietude. Mitchell’s Sacred Instructions, Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, Hernandez’s Fresh Banana Leaves—all of which I will continually revisit—respond to the aftermath of and ongoing trauma caused by “ecocolonialism”, or “the altering of our environments and landscapes due to colonization of Indigenous lands and the paradigms that are upheld to grant settlers (white people) the power to continue managing our environments and landscapes” (Hernandez 2022, p. 42). Their responses, I argue, are crucial for understanding their intentional processes of decolonizing our relationship to nature-as-teacher and, as I will show in a following section, unpacking this relationship in Indigenous speculative fiction. Mitchell and Hernandez, in particular, are critical of the top-down, settler colonial capitalist ideology dominating environmental activism. “There is no way to balance the domination model”, Mitchell argues. “It is designed to breed imbalance, inequity, and injustice” (Mitchell 2018, p. 112); it is designed to exclude the voices of Kimmerer, Mitchell, Hernandez, and other Indigenous scientists whose profound knowledge of our world includes the teachings of ancestral mythologies and nature. Mitchell coins the dominant, settler-lead, antagonistic conservation efforts—such as “wage war on climate change”—“conquest activism” (ibid., p. 115). On Mitchell’s account, activism of this sort employs divisive conquest ideology rooted in colonialism. “Approaching activism with the intent to conquer an opponent always leaves us with a population that is negatively impacted by our actions” (ibid., p. 117), and we need everyone, Mitchell continues, for we are not homogenous, despite colonization’s insistence otherwise. “Diversity and distinction are essential for a healthy system” (ibid., p. 118). Mitchell turns to soil to impart this lesson: “Just as monocrop agriculture weakens the soil and deprives it of valuable nutrients, homogenizing our cultures weakens our societies and deprives us of our core values” (ibid., p. 112). Restoring balance, then, necessitates not only an attunement to ancestral knowledge and the natural world, but a rejection of conquest activism that, through its participation in the rhetoric of the oppressor, muffles calls for multispecies, inclusive eco-collectives.

Hernandez offers a similar critique of conservation, describing what she calls a “top-down approach” wherein Western science prevails over Indigenous knowledge to dictate conservation efforts in a way that smacks of paternalism and hence colonialism. Dismissive of Indigenous ancestral knowledge, science, and lived experience, this “top-down approach centers scientists and conservationists as the knowledge holders who continue to come into Indigenous communities and territories and advise Indigenous peoples what to do with their environment” (Hernandez 2022, p. 82).9 Like Mitchell, Hernandez locates the birth of conservation within settler colonialism. As its harmful offspring, top-down conservation and conquest activism hardly address the hurts caused by ecocolonialism and merely perpetuate the imbalance Indigenous science seeks to address. Instead, Hernandez advocates for a bottom-up approach that centers the notion of “living within”, a way of being and relating that permeates Indigenous mythology, contemporary speculative fiction, and related scholarship, all of which I will discuss in turn. Within the context of conservation—or healing—“living within” refers to the people who have lived experiences within “the environments scientists are trying to protect and serve” (Hernandez 2022, p. 87). Healing efforts should come from within these communities, from the source—the bottom—and not from without. When we pause to consider “community” from an Indigenous perspective, we are reminded of all that comingles along with humans to form this bottom: nonhuman species, sediment, root systems, mycelium, geological footprints, and ancestral whispers. Certainly, these experts within include our most profound and some of our oldest teachers and, as both Mitchell and Hernandez assert, are best situated to lead healing efforts towards restoring balance.

Interspecies and Nonhumans as Teachers, as Kin

Of course, a shift in tenor alone—that is, swapping out the language of colonization with that of Indigenous science—runs the risk of coming off as performative activism. This is true of humanities and science classrooms as well unless these spaces actively work to dismantle the myth of separation and begin living within the reciprocal interspecies enmeshments. The approach, therefore, goes beyond a framework with updated verbiage. To lull Kiwawk to sleep, we should, Mitchell insists, “approach the process from a place of kinship”, taking a “communal approach” and ensuring everyone, including other species and the natural world, “feels valued” (Mitchell 2018, pp. 118–19). Borrowing from the work of Dr. Enrique Salmon, Hernandez refers to this human–nature relationship as “kincentric ecology”. She writes, “This term tries to explain the human relationship Indigenous peoples have with their environments through the notion that we are not separate from nature but rather an integral component” (Hernandez 2022, p. 115).10 Indeed, the excerpts from Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass and aforementioned Indigenous mythology and science testify to Indigenous peoples’ way of living within and relating to “their natural resources and surroundings as part of their kin, relatives, and communities” (ibid.). Therefore, a pedagogy and praxis purporting to center Indigenous science that does not foreground these multispecies entanglements falls short in its aims. Without this expansive notion of kin, we are left with only ourselves, humans, the one species proven to repeatedly throw off kilter our precariously balanced planet.

As kin, our nonhuman relatives are insightful cocreators of ecological science knowledge. They are the microbes, mycelium, and marine mammals that live and speak from within the soil and ocean bottom, fluent in the languages “we have yet to learn” (Kimmerer 2016, p. 49). They are languages hidden to us by the myth of separation and deference to Western modes of scientific thinking, voices we cannot hear “if your only way of knowing is data” (ibid., p. 46). Kimmerer advocates for immersive field study and long-term ecological reflections. Becoming intimate with the place, really listening to the land…makes for better science, because the land will suggest new questions” (ibid.). In her “Interview with a Watershed” and “Listening to Water”, Kimmerer bears witness to the stories told by water, old growth, mossy stones, and the alder leaves as they drift down the stream. Nature’s dutiful, patient student, she catalogues the healing strategies her nonhuman kin speculate on. The opportunity to write their new stories “lies in listening to the land for stories that are simultaneously material and spiritual” (ibid., p. 44). A meditative practice, Kimmerer’s performance of Indigenous science likens research to “an interview of sorts between two parties that don’t speak the same language”, a conversation between long-lost relatives distanced by ecocolonialism (ibid.).

The multisensory way of relating to and living, as kin, within the world Mitchell, Hernandez, and Kimmerer describe frequents the pages of scholarly journals and books written by non-Indigenous thinkers and scientists. Many of their contributions pay homage to Indigenous science rather than merely appropriate, rename, and attribute the ideas to themselves. As such, I bring them in to the discussion here not as central scholarship, but for what they add to the existing and seminal teachings from Indigenous ancestors, elders, and contemporary thinkers. The foci of the various supplementary texts offer concrete happenings of interspecies mingling, kincentric possibility, and collective resurgences in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. In other words, they build on the possibility of hope and serve as touchstones for those seeking to overcome eco-anxiety and environmental nihilism, like my students, and like myself. Moreover, they do so in a way that furthers efforts to decolonize ways of relating and the language used to describe them, thereby actively challenging the myth of Western science’s unquestioned credibility. Their musings also enrich the ecohumanities syllabus I have in mind with their nods to the speculative fiction of plants, lessons from animals, and other enlightening modalities for listening to, learning from, and living within the natural world.

In a precarious world where frustration and fear spark anger and conquest activism, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing and her co-authors, in Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, recommend “we begin with noticing” (Bubandt et al. 2015, p. M7). Once engaged in this practice, we “might look around to notice this strange new world, and we might stretch our imaginations to grasp its contours. This is where mushrooms help”, Tsing suggests (Tsing 2015, p. 3). In her seminal work, The Mushroom at the End of the World, Tsing details the resilience of fungi within the liminal space of imbalance. Tsing celebrates mushrooms’ ability to teach us not to abandon hope but “to turn our attention to other sites of promise and ruin, promise and ruin” (ibid., p. 18 emphasis in original). Tsing’s art in noticing fungi’s lessons on possibility inscribes the teachings of the matsutake mushroom found in its “willingness to emerge in blasted landscapes”, and its creation of lifeways through the assemblages of multispecies collaborative survival (ibid., pp. 3, 23). The matsutake alone will not save us, Tsing admits, but the promise of possibility it holds as it stubbornly thrives amidst and because of decay and indeterminacy captures an expansive and inclusive version of world making that “makes life possible” (ibid., p. 20). The matsutake models what it means to live within a community wild with diversity and one wherein the generative power of a wasteland is harnessed and necessary for collective survival.

Beneath the mushrooms lay “trillions of miles of the circulatory system of the planet”: mycelium (Harvey 2021). Tendrils of communication between the fungi and trees, mycelium transforms carbon into intricate networks vital for soil’s biodiversity, a biodiversity necessary for striking a life-sustaining balance. Vast highways of hope, mycelium speaks to and about decomposition and resurgence; it tells the ancestral stories of our forests, weaving “a palace of rot” within old growth (qtd. in Brodie et al. 2016, p. 119). Mycelium is, poet Thomas Lowe Fleischner concludes, “a major shaping force in forest communities/yet invisible/and to most forest ecologists, even,/unknown” (qtd. in Brodie et al. 2016, p. 119). Ecologists, mycologists, and environmentalists emit a tangible excitement over what mycelium can teach us about carbon storage as well as reciprocity and symbiosis among organic life beneath the immediately observable surface. Perhaps the greater lesson mycelium has to teach is one of multispecies connections, collaborative resiliency, and a more nuanced understanding of what it means to communicate. Indeed, as Biidaaban illuminates and I explore in the next section, mycelium tethers together human and nonhuman, the living and ancestral spirits, the stories being written with the mythology of the past.

If matsutake and mycelium can teach us about resilience, multispecies connections, and novel ways of communicating, what can we learn from the animals we live among within shared ecosystems? What if, Alexis Pauline Gumbs proposes, “we expand our empathy and boundaries of who we are to become more fluid, because we identify with the experiences of someone different, maybe someone of a whole different species” (Gumbs 2020, p. 9, emphasis in original). In her humbling practice of apprenticeship, Gumbs attempts to identify with marine mammals, becoming a pupil of the Black feminist lessons they have to teach. Undrowned both chronicles her immersion as well as invites us all to “see what happens when [we] rethink and refeel [our] own relations, possibilities, and practices inspired by the relations, possibilities, and practices of advanced marine mammal life” (ibid.). Each of the twenty meditations11 submerge readers into a multisensory lifeworld where we flip and dive, play and laugh, and otherwise live as kin, learning alongside ocean critters. Gumbs, attuned, like Mitchell and Hernandez, to the entanglement of ancestral spirits and earth, listens to the stories gray whales might tell of the transatlantic slave trade. Bottom feeders, the gray whale filters sediment containing the bones of enslaved Africans who either leapt to freedom or were thrown overboard by their captors. “So there is actually a digestive truth to the idea that the ancestors we lost in the transatlantic slave trade became whale” (Gumbs 2020, p. 118). The gray whales, then, are experts not only in marine ecology but in the sediment infused with slavery’s ghosts and therefore their stories. For Gumbs, the gray whale is both storyteller and scientist; it speculates about interspecies relationships and the “toxicity of the slave trade and its impact in the ocean” (ibid., p. 119).

African and African diaspora speculative fiction frequently revisits the Atlantic Ocean, reimagining and creating anew seascapes and marine life that confront the ocean’s specters and conjure futurity for those robbed of life in the corporeal sense. Gumbs’s own “Bluebellow” “imagines mermaid zombie survivors of the middle passage connecting with Black people who take the reverse transatlantic journey to Europe” (Gumbs 2020, p. 11). Animal spirits, along with mycelium, similarly factor into Biidaaban, connecting ancestors and inherited Indigenous knowledge to their Native pupil in a post-apocalyptic present. Natania Meeker and Antonia Szabari’s Radical Botany attributes a similar creative and instructional potential to vegetal life and, given the preexistence of Indigenousness science,12 does not pose a novel perspective inasmuch as it enrichens the discourse and foregrounds plants as authors of speculative fiction and purveyors of their own unique and often unintelligible mythos. I find the way they frame the speculative potential of plants not only applicable to Tsing’s matsutake and Gumbs’s white whale but a dazzling addition to the conversation as a whole, a linguistic framing of nature’s vital role as teacher. Vegetal life, such as fungi and animals, drives knowledge production; “plants are not just objects of manipulation but participants in the effort to imagine news worlds and envision new futures” (Meeker and Szabari 2020, p. 2). The authors of Radical Botany carefully construct their prose to disrupt “thinking of plants as passive beings”, proposing instead the vegetal as coparticipant, world-maker, and multisensory visionary. As apprentices to this other species, we begin to “think with and alongside plants”, growing porous and receptive to their teachings and speculations about futurity (Meeker and Szabari 2020, p. 21).

Radical Botany’s contribution to the discourse expands the multispecies entanglement and what it means to live within this enmeshment of plants, fungi, animals, and elemental and ancestral spirits. Meeker and Szabari join a resonance of voices in a harmony of collaborative speculation about hopeful outcomes for the survival of our species. Yet, like Kimmerer, Hernandez, Mitchell, Tsing, Gumbs, and others, they are firm in their insistence for an upending—or, perhaps, a reordering—of an ecological hierarchy that primacies the athnro and reinforces the myth of separation. Nature, they argue, encapsulates a sacred mythology brimming with lessons on resiliency, hope, and untapped possibilities. Conduits of nature’s sacred instructions, they proffer guidance on how to frame a healing-centered ecohumanities approach in classroom spaces.

Speculating Multispecies Futurity in Biidaaban

My colleague and I scaffolded the art of noticing by prefacing our foray into speculative fiction with opportunities for students to engage with ideas and practices captured above. Each class meeting began with a meditative practice in living within the landscapes and among nonhuman kin. Excerpts from Gumbs’s Undrowned, passages from Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, time-lapse videos of decomposition’s “promise and ruin, promise and ruin” framed a daily outdoor journaling exercise of listening to and learning alongside nature (Tsing 2015, p. 18 emphasis in original). By the time we arrived at a series of Indigenous short films, our classroom community was familiar with the Indigenous science and lifeforce inherent in interspecies entanglements undergirding the narratives. I put three films in conversation: Don’t Look Up, The 6th World, and Biidaaban. I asked students to consider how the two Indigenous films, as examples of speculative fiction, responded to McKay’s Netflix blockbuster. Specifically, as students in a healing-centered ecohumanities class, I wanted them to consider how the absence of Indigenous science in one and its presence in others impacted process and outcomes for all characters—human and nonhuman—in each film. The 6th World, for examples could be read as a direct response to Don’t Look Up insofar as it is Navajo Astronaut Tazbah Redhouse’s reclamation of ancestral practices with Indian corn that rescue the mission and germinate the first crop on Mars. We also discussed how the short films counter the myth of separation and Don’t Look Up’s inevitable singular apocalypse. How they, in other words, speculate actions and futures that “better honor [Indigenous] epistemologies, traditions, and inherent rights to self-determination” rather than prolong Native apocalypses and conjure eco-anxiety and existential despair (Medak-Saltzman 2017, p. 148).

In conversation with each other, The 6th World and Biidaaban add to the larger anthology of stories, traditional mythology, and inherited knowledge that center the collaborative potential for messy, multispecies entanglements to respond to Native Apocalypses by restoring balance. As Indigenous futurist projects, the films, to borrow from Danika Medak-Saltzman (Turtle Mountain Chippewa), “rely on Indigenous innovation and creativity to bring about change in ways that are always-already informed and supported by Indigenous political concerns and Indigenous ways of being in the world” (Medak-Saltzman 2017, p. 144). Stories and mythologies that insert Native peoples into their own futures “have always been, and remain, deeply entrenched in, and important to Native communities” Medak-Saltzman adds ibid., p. 146). These renderings serve as “a particularly powerful act” of reclaiming the “lands, bodies, labor, and/or lifeways” robbed from Native communities by settler colonialist practices such as ecocolonialism (ibid.). Not surprisingly, my class and I were especially drawn to Biidaaban, in part for its mesmerizing stop-motion animation, Indigequeer characters, hypnotic pallet, and otherworldly tenor. The name given to one of the two nonbinary characters and the only human in the film, Biidaaban, in Ojibwe, the native language of the Anishinaabe people, means “dawn comes; it is daybreak” (The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary 2021).13 In the Mnjikaning community, Biidaaban denotes a particular healing model intended to be used within Ingenious communities and alongside criminal justice proceedings involving Indigenous peoples as a restorative approach to otherwise punitive systems. In practice, Biidaaban guides individuals through a personalized return to their “traditional roots” as part of a journey towards restoring balance for individuals and communities impacted by domestic violence and the traumatic aftermath of colonialism on indigeneity (Couture and Couture 18).14 Like the healing practice, Biidaaban’s journey includes a return to traditional roots that manifests most obviously as the “tapping sugar from maple trees as it has been done for thousands of years” (Oleksijczuk 2021, p. 9). As a healing practice, film, and character, Biidaaban harnesses ancestral knowledge to propel their people forward, beyond settler colonialism’s literal and figurative wasteland, and towards sovereign futures.

The film is also an immersive educational experience,15 plunging its captive audience into a world woven of Indigenous mythology, ancestral practices, and survivance. In these ways, I argue that Biidaaban exemplifies “the shimmer of life”, for its aesthetic “calls us into these multispecies worlds” (Rose 2015a, pp. G51, G53) where spirits and nature, humans and critters come together as kin “to experience the dynamics of participation in the enduring and the ephemeral, birth, life, death, and mutualistic, multispecies waves of ancestral power” (Rose 2022, p. 141). A bioluminescent glow, Biidaaban’s shimmer merges story and student with the themes from Mitchell, Hernandez, Kimmerer, and others discussed above. Shimmer simultaneously teaches the text and illuminates the equally instructional tendrils sustaining lifeways and communication among and between those who live within Biidaaban’s multiverses. Following shimmer as it traverses the veiny pathways carved by insects, root systems, and mycelium in and around the film’s maples reveals the subtle and nuanced moments when Biidaaban and Sabe, a 10,000-year-old shapeshifter, tap into ancestral knowledge in their joint practice of Indigenous science and “the ceremonial harvesting of sap from maple trees in a menacing urban neighborhood in Ontario” (Oleksijczuk 2021, p. 9). When shimmer takes over as teacher in a healing-centered ecohumanities class, opportunities appear for students to ground abstract ideas in a concrete text that itself is firmly planted in the inherited eco-epistemologies and mythos of Native cultures.

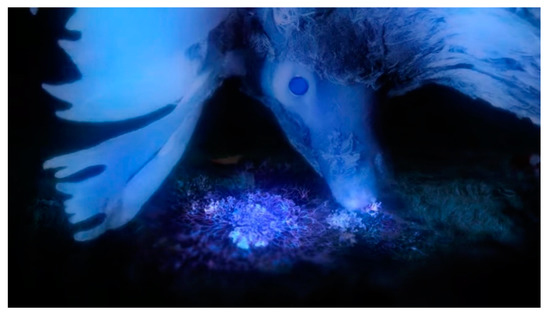

Ironically, dawn never comes in Biidaaban, in a celestial sense. Shrouded in a swathe of melancholic midnight blues and blacks, the setting speculates on a future in which the sun is almost entirely absent, but the changing of seasons and continuation of life that this progression promises are not. The dark backdrop means shimmer pops from the frame, like glowing bioluminescence in nighttime’s ocean waters, pulling the viewer’s gaze along a narrative arc co-created by the human and nonhuman shimmer connects. The film opens with a gradual accumulation of a white-blue light I read as symbolizing shimmer as it passes through and illuminates root systems, mycelium, and other conduits for collaborative survival and interspecies communication. We follow shimmer along a powerline, down a tree, and into one of the film’s two spirit animals, the caribou ghost, who transmits shimmer’s healing power through lichen to free the maple of the restrictive red mesh encircling its trunk (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Caribou Ghost in Biidaaban (00:01:09).

- Storyteller, teacher, magnifying glass, mycelium, animal ancestors—shimmer visually illuminates in Biidaaban’s opening sequence the interconnectedness the Indigenous scientists and creatives foreground in their practices and the perspective of learning alongside nature—within it, as kin—that a healing-centered ecohumanities pedagogy promotes.

Shimmer also leads us into the innerworkings of a technology in Biidaaban used by human and shapeshifter to engage in reciprocal dialogue throughout their practice of the traditional maple sugar harvest. The pair communicate the seasonal needs of the harvest using a device that resembles a geode (Figure 3). Rocklike with vegetal accents, the device functions somewhat like the texting feature on a smartphone. Strong, like Meeker and Szabari do with plants, situates mycelium “not just on the receiving end of technologies but also as agents that can inspire technological change” (Meeker and Szabari 2020, p. 6). Instead of a lithium battery obtained through the ecocolonialist methods of extraction and human exploitation, shimmer—that is, the luminous striations of fossilized sediment resembling mycelium—powers the tool.

Figure 3.

Communication device in Biidaaban (00:09:30).

- Shimmer, imagined as such, offers instruction in the immense communicative potential found within our planet’s naturally occurring systems, such as mycelium. Strong, along with Indigenous science more generally, certainly puts great stock in mycelium’s “major shaping force in forest communities” as a conduit for communication between human and nonhuman, the living and spirits (Brodie et al. 2016, p. 119). Shimmer in Biidaaban glides along mycelium, entangling us and itself in a complex interstate of messaging highways that transmit needs, knowledge, and tradition. Biidaaban’s enmeshment of shimmer and mycelium thus animates the animal, vegetal, ancestral, and technological, awakening in them and in students’ imaginations the possibility for interspecies conversations vital for sustaining life, even when, as Kimmerer observed, those involved no longer speak the same language.

Despite differences in dialect, Biidaaban’s maple trees participate in the reciprocal production of myth and meaning alongside the film’s other nonhuman and human kin, a process illuminated by shimmer. The maples are no less animate and integral to this process than the film’s sole human. In this way, and “In our Anishinaabe way”, Kimmerer writes, “we count trees as people, ‘the standing people,’ and the maple, according to the Onondaga Nation, ‘the leader of the trees’” (Kimmerer 2013, pp. 168–69). Strong’s characters’ relationships with the maples capture a story, in staying with Indigenous tradition, that has been “retold by different storytellers for generations” (Oleksijczuk 2021, p. 9). Matthew Harrison Tedford, noting the maple trees’ culture significance, remarks that the “relationship between someone like Biidaaban and maple trees is intergenerational, symbiotic, spiritual, and even cosmological” (Tedford 2020). The leader of trees, kin ground the film’s characters in traditional practices, multispecies entanglements, and kinship with the natural world. Indeed, shimmer’s neon white glow electrifies the trees and the reciprocal transfer of cocreated knowledge and meaning-making between human and nonhuman. In this way, the maple, Biidaaban, Sabe, ghost caribou, ghost wolf, and ancestors are never not connected. This visually discernable thread symbolizes what, in Kimmerer’s view, “it means to be a citizen of Maple Nation, having maple in your bloodstream, maple in your bones” (Kimmerer 2013, p. 172). Biidaaban’s process of marking, tapping, and collecting sap from the maple trees is always marked by a transference of shimmer; in fact, shimmer and the intravenous flow of sap are one in the same (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Sap illuminated by shimmer in Biidaaban (00:11:45).

- Maple, then, not only enters the bloodstream symbolically through spiritual channels, but the sweet sap calcifies inside the body as the syrup is consumed and “maple carbon becomes human carbon” (Kimmerer 2013, p. 172). Once again, there is a “digestive truth” to a transmutative becoming that, like Gumbs’s attributes to the gray whale, involves the consumption of the entity something becomes. “Our traditional thinking had it right;” Kimmerer reflects, “maples are people, people are maples” (ibid.)

Sabe teaches this lesson in Indigenous science even more explicitly. A shapeshifter enshrined in vegetal-like armor, Sabe sparkles, shimmer’s iridescent hue highlighting their organic garb and viny “hair” in constant, autonomous motion. Unlike Biidaaban, Sabe can transcend the boundaries demarcating human and nonhuman realms. Set aglow by shimmer, they move with fluidity between the maple trees’ external and internal environments, becoming one with the enmeshments within and without (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Sabe entering a maple tree in Biidaaban (00:05:34).

- Sabe, shimmer, and the species with whom they merge cocreate a lesson in Indigenous speculative fiction’s “emphasis on newly vibrant materialities and bodies” and the possibility this mode of storytelling holds for students to think about “how becoming plant can disassemble and reassemble us” and how, in turn, our thoughts become “more plantlike” (Meeker and Szabari 2020, pp. 6, 22). Sabe and Biidaaban—thinking “with and alongside plants”—model an attunement with the natural world I want my students to enact in their healing-centered ecological inquiry (ibid., p. 21). They approach nature with humility, pair tactile interactions with a familial tenderness, and occupy spaces within the multispecies entanglements with an unobstructive quietude. This renders them, as it will students, more adept in the art of noticing shimmer, more receptive to nature’s sacred instructions.

In Biidaaban’s final and most overtly speculative act, shimmer makes visible a reciprocal exchange of life-forces that in turn blurs boundaries between species and spirits, muddying the myth of separation, and illustrating not only what it means to live within these enmeshments but what it looks like to thrive. Placing their hands on the soil, where they buried tokens of ancestral importance beneath a maple tree, Biidaaban ignites shimmer’s communicative power, sending through mycelium’s circuitry a lifeforce that awakens their ancestors, who resume their traditional practice of harvesting sap from the maple trees. With this act, the interconnectedness Indigenous science recognizes is brought to the fore by Strong’s framing of a triad of interrelated realms in totality. With this act, balance is restored (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Triad of interrelated realms in Biidaaban (00:16:34-00:16:50).

An exemplar of Native apocalyptic storytelling imbedded in a healing-centered ecohumanities curriculum, Biidaaban “shows the ruptures, the scars, the trauma in its effort ultimately to provide healing and a return to … a state of balance” (Dillon 2012, p. 9). The film’s shimmer illuminates and sutures these ruptures, sparking a regenerative healing achieved when Indigenous eco-epistemologies and lifeways triumph over the distinctly humanmade, hostile commodities (blinding floodlights, aggressive sprinklers, and cantankerous houses). “Biidaaban … dismantles the divisions between human and more-than-human beings,” calling the myth of separation’s bluff (Oleksijczuk 2021, p. 10). In my classroom, the film “poses questions which enlarge our capacity for thinking-feeling about industrial modernity’s parasitical relationship to Mother Earth” and urges us to learn “from the land and with the land” (ibid.). An antidote to eco-anxiety and existential despair, Biidaaban speculates about constructive, hopeful, expansive ways of being, relating, and living within multispecies futures abundant with shimmer.

Hope-Filled Classrooms

Across her scholarship, Maria Ojala argues that constructive hope has “a positive impact on young people’s well-being and environmental efficacy” (Doyle 2020, p. 2752). In other words, contending with optimistic outcomes for the very real climate crisis may cultivate a learning community less prone to environmental nihilism and more motivated to take actions, including subtle steps discussed here, such as checking their anthropocentric hubris and embracing nature and their nonhuman kin as teachers. A shift in perspective echoed in various ways by the Indigenous scientists, speculative fictions writers, philosophers, and ecologists cited above, “Living in a time of planetary catastrophe thus begins with a practice at once humble and difficult: noticing the worlds around us” (Bubandt et al. 2015, p. M7A). Sitting in meditative silence with our cuttlefish and chrysanthemum cousins, however, is only part of what Ojala and Doyle propose that pedagogy and praxis aimed at fostering constructive hope among students include. “In order to lessen pessimism and/or indifference one should help students to envision alternative futures and educate them in ‘the language of possibility” (Ojala 2011, p. 5). Building on Ojala’s work as well as the potentiality Haraway locates within speculative fiction to imagine possible futures, Doyle urges educators to use climate stories that “offer critically hopeful engagements” instead of the “individualist, technocratic, and fear-based approaches to climate change [that] can negatively influence young people’s active participation” and trigger crippling eco-anxiety for students (Doyle 2020, pp. 2749–50). Doyle’s play-based approach counters the existential despair of climate doomsday narratives by engaging students in the collaborative speculation of alternative futures.

While I agree with Doyle that in classrooms seeking to spark environmental efficacy and a sense of wellbeing, speculative fiction can help students imagine hopeful outcomes to the very real climate crisis, I propose, contrary to Doyle, that we hold onto apocalyptic imaginaries, shedding instead our narrow, anthropocentric, and cataclysmic conception of apocalypse. Indigenous mythology and speculative fiction teach us that apocalypses—“as ellipses”—do not immediately culminate in mass extinction, and this lesson remains potent in the context of a classroom. Likewise, Tsing’s resilient little matsutake speaks to us from the rotting crevasses and decaying wastelands with an unmistakable message of hope. Shimmer persists in a future Toronto’s frigid and foreboding landscape because of Biidaaban and Sabe’s efforts to sustain ancestral tradition, their sacred practice of Indigenous science. Native mythologies and creation stories step in to assist with meaning-making, translating nature’s ancient languages, for “myth”, according to storyteller Martin Shaw, is “the language in which the world thinks” (Wingfield-Hayes 2020). Thus, where Doyle’s speculating about fictional hopeful futures starts from students’ present, I prefer an interdisciplinary, transhistorical, multiversal, and multispecies approach wherein students cocreate futurity alongside those with whom they share this planet, both human and nonhuman kin. To do otherwise, I fear, puts students in the position of reifying and even replicating a settler colonialist conservationism that privileges “rugged individualism” and further upsets the natural balance.

Healing-centered, “What Would the Mushrooms Say?” as a concept and class counters ecocolonialism with the symbiotic interspecies entanglements and epistemologies of Indigenous science. It is a pedagogy that does not move to topple or overcome Western science but foreground what Whyte refers to as Indigenous “portfolios of knowledge”, which include “older and ancient knowledge, intellectual traditions, and then also a lot of contemporary knowledge including the use of different sciences” (Wray 2020). It is an approach that understands that the “sense of connection” integral to Indigenous science “arises from a special kind of discrimination, a search image that comes from a long time spent looking and listening”, from learning from and alongside nature (Kimmerer 2003, p. 13). From this place, “connected to the consciousness of matter…true myth too is written, a translation of this language that lies between all things, a language which we access through the imaginal realm and images, the feelings senses of the body and intuition” (Wingfield-Hayes 2020). It is an activity of “reciprocal capture”16 wherein “transformative encounters, seductive moments…generate new entangled modes of coexistence” (Kirksey 2015, p. 3). From these moments spent “looking [and] watching each other’s way of living” and learning the stories about relationships they have to tell, we arrive at actual instances of the “possibility of life in capitalist ruins”, (Tsing 2015), of “hope in the reverted zone” (Kirksey 2015, p. 36), of multispecies survivance unfolding in emergent ecosystems. Instances that, in turn, lead to speculation, fictional or otherwise, about hopeful futures for all.

Conclusions: Towards Environmental Optimism

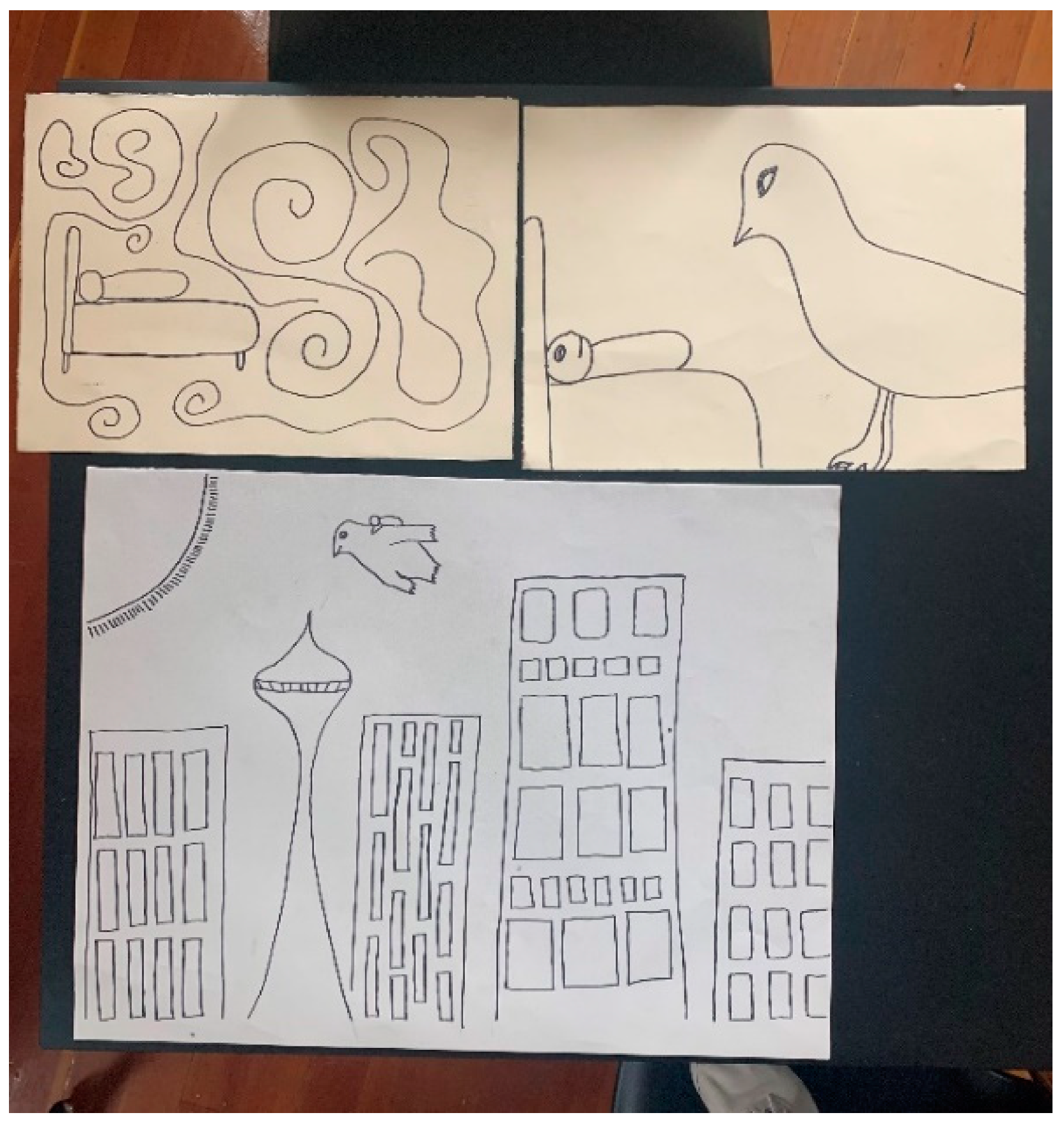

Down the hall from my classroom, in a colleague’s room, Donna Haraway’s sympoiesis, an “art-science activism” and co-creative practice of worlding, emerges, stich by stich, as a crochet coral reef (Figure 7). Laughter, casual conversation, and the occasional expletive following a dropped stich punctuate students’ teacher-facilitated inquiry into the life-worlds, cultures, and regions they recreate through their craft.

Figure 7.

Coral reef crocheted by students, in a fellow teacher’s classroom.

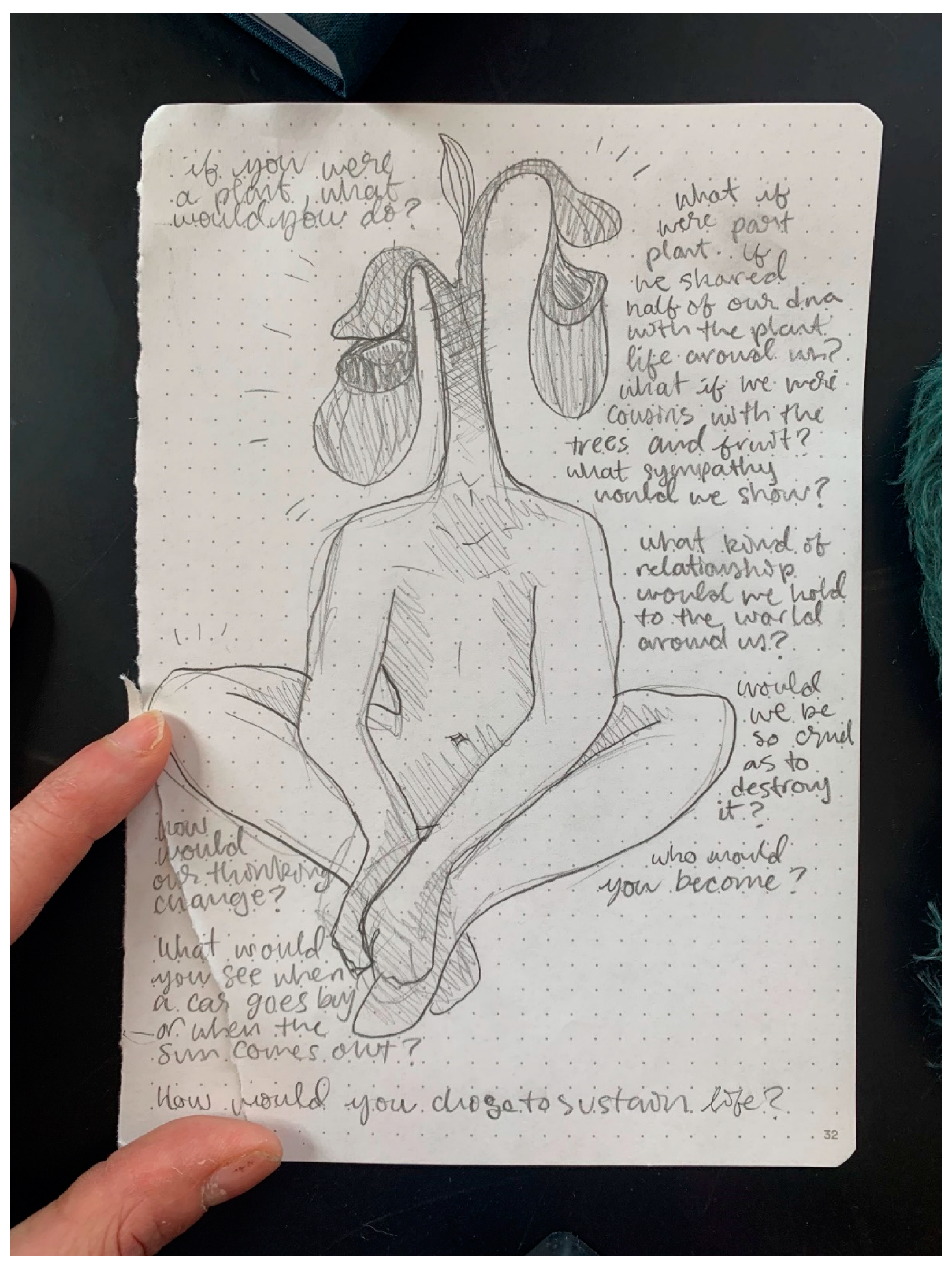

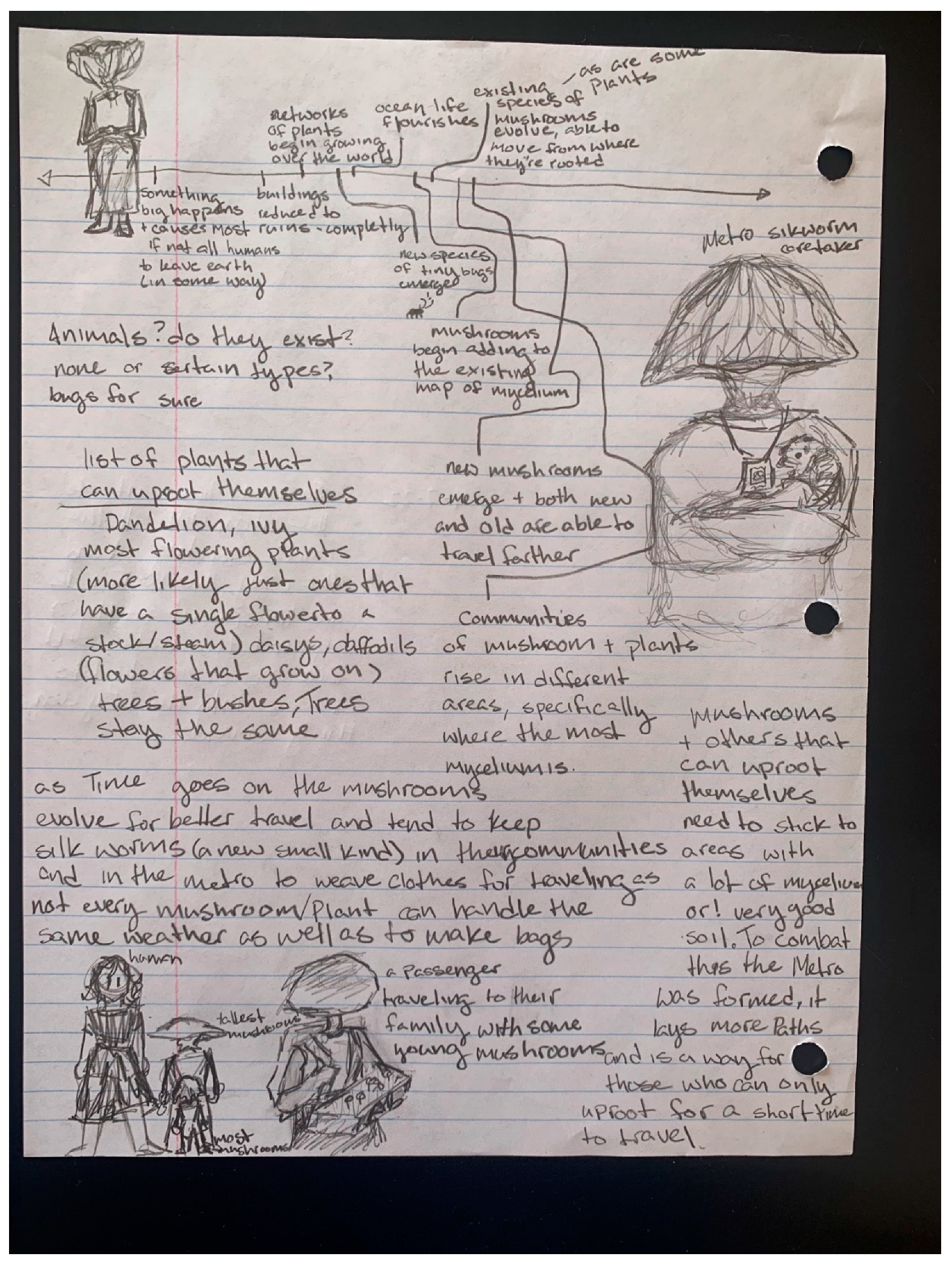

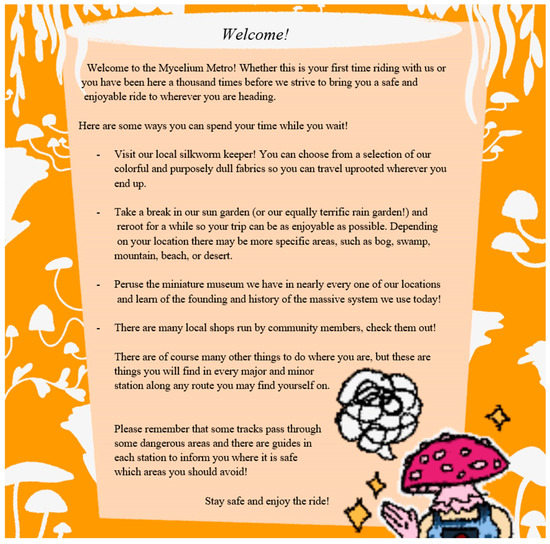

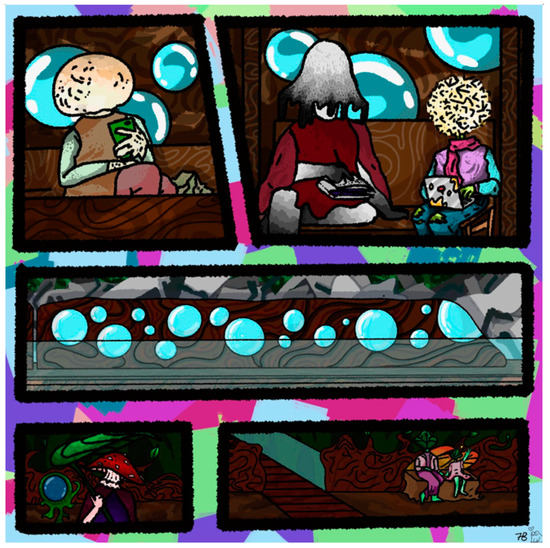

A few doors down, in one of two spaces my class meets, students present their speculative fiction projects. A three-verse illustrated poem captures one student’s hopeful present and the promise of a similarly hopeful future, having followed a bird guide to healing (Appendix A). Another imagines themselves as plant and ponders the sorts of questions they might ask in this vegetal state (Appendix B). A third, in a nod to the solarpunk aesthetic and the devices in Biidaaban, merges species to imagine a mass transit system powered by mycelium for a society populated by human/fungi/vegetal enmeshments (Appendix C.1, Appendix C.2 and Appendix C.3). The resonant themes across students’ projects—those of a porousness to the natural world, relating to the nonhuman as kin, and allusions to the Indigenous science and mythology we engaged with in class—weave optimistic stories of symbiotic interspecies entanglements and collaborative survivance. Their stories foretell lifeways made possible by disrupting what Hernandez described as a top-down approach to conservation and one that devalues Indigenous knowledge (Hernandez 2022, p. 82).

Actualizing and sustaining a state of environmental optimism entails the continued reordering of mythologies and dismantling of the hierarchies criticized by Mitchell and Hernandez. This is especially difficult given “we have been conditioned to believe that our safety and our acceptance within the societies we occupy are dependent on supporting those at the top of the hierarchies we’ve created” (Mitchell 2018, p. 114). Minimizing the myth as well as the literal separation dividing us from our nonhuman kin disrupts one such hierarchy. Championing myths of “progress” told from the perspective of white settler colonialism and today’s tech giants only exacerbates the division between humanity and the natural world, as does action dressed up as being culturally inclusive. As Karsten Schultz dryly notes, “Indigenous ways of ‘becoming-with’ the environment are not meant to be calls for more ‘conscious’ geoengineering, the patenting of traditional medicine, or new green transformations led by the agrochemical industry” (Karsten Schultz 2017, p. 137). Environmental optimism counters the popular notion of the Anthropocene as a geological age in which humans are the pinnacle species whose existence or extinction demarcates a prophetic beginning and catastrophic end. It involves “undoing a definition of the human, which is so tangled in separation and domination that it is consistently making our lives incompatible with the planet” (Gumbs 2020, p. 9). Yet, mythology can also reunite us with our animal, vegetal, and other nonhuman kin, restoring a reciprocal sharing of knowledge through storytelling and instruction, where the mythos draws from ancient ways of relating to nature. “Stories for living in the Anthropocene demand a certain suspension of ontologies and epistemologies, holding them lightly, in favor of a more venturesome, experimental natural history” (qtd in Bubandt et al. 2015, p. M45). Indeed, “One of the great roles of myth”, concludes Wingfield-Hayes, “is to lead us back in this way, as feeling, instinctual beings”. Perhaps it is time we slow down and practice the art of noticing.

For my students, environmental optimism signals viable alternatives—preferable ones, at that—to technocrats Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk’s off-planet ventures. Of course, options other than interplanetary colonization mean less money for these guys and greater opportunities for people like me, my students, and the other dredge of our Earth. Naturally, then, “those guys” do not have a vested interest in repairing our relationship with our planet in a way that not only renews our bonds with the natural world but amplifies the voices of Indigenous peoples, Black folks, Asian Pacific Islanders, vegetal and marine life, and other communities whose wisdom white capitalist settler colonialism has pushed to the margins of climate discourse. Environmental optimism requires a reimagining of catastrophe, one that adopts an anti-hegemonic notion of the apocalypse as always-already occurring, a state of imbalance. Understood as such, we come to appreciate the apocalypse both as a lived experience and as a generative space for renewal and possibility—a space abundant with shimmer—rather than the foreclosure of futurity for those who cannot afford to escape a doomed planet.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The Story of My Recovery (for what would the mushrooms say)

- Part One:

- Bed bound by pain

- Head hung by a single string

- Even a bed stand feels so far

- Even a lift of finger feels so hard

- And dreams are ones only friend

- Please just let me untie my head

- Part Two:

- I miss her

- Thoughts of cliffs and hights so high

- The constant racing

- Has me ever pacing

- I can’t take this anymore

- Please lord

- Just let me soar.

- I look up, and there it is

- A bird.

- Part Three:

- I climb on and hold tight for dear life

- Everything moves fast except time

- For it’s not a short flight

- Above grimy city, cigarettes, sex, and graffiti

- We fly above the clouds

- So the rain can’t always hit me.

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix C.1

Appendix C.2

Figure A1.

Pictured above: front of a pamphlet from the Mycelium Metro.

Appendix C.3

Figure A2.

Pictured above: reverse side of the pamphlet above (Appendix C.2).

Notes

| 1 | In “The Ecological Humanities,” Deborah Bird Rose attributes the emergence of the the interdiscpline to a breach in “the Western division between human and history and natural history” (Rose 2015b, p. 1). According to Rose, the ecohumanities aim to “addess the fact that current ecological problems, including extinctions, climate change, toxic death zones, water degredation, and many others are anthropocenic events” (ibid.). Citing philsophper Val Plumwood, Rose names the two major tasks for the ecohumanities as, first, “resituating the human in ecological terms,” discarding of the idea that humans are “outside nature”, and, secondaly, resituting “the non-human in ethical terms” (Rose 2015b, p. 3). The latter, Rose claims, consitutues “a first step towards overcoming a Western science worldview that defines the natural world as morrally inert” (ibid., p. 4). |

| 2 | “What Would the Mushrooms Say?”, the title for this paper and approach proposed therein, is derived from the course title for a secondary ecohumanities class I co-teach with an environmental science and history teacher. The title stems from, in part, the practice of returning to students’ their questions about the climate but from the perspective of the communities most impacted, the natural world, and nonhuman species. “Mushrooms” is a nod to student interests and both the class and concept’s references to mycelium’s contribution to climate discourse. |

| 3 | “The American Psychological Association (APA) defines eco-anxiety as ‘the chronic fear of environmental cataclysm that comes from observing the seemingly irrevocable impact of climate change and the associated concern of one’s future and that of next generations’” (Naameh 2022, emphasis in original). |

| 4 | According to (King 2021), “A study conducted last year with ten-thousand people ages 16-25 from ten different countries found that 60% felt very or extremely worried about climate change, and 45% said that their feelings about climate change impacted their daily lives” (00:00:51-00:01:07). |

| 5 | Deborah Bird Rose expands on her encounters with the flying fox and shimmer in her book Shimmer: Flying Fox Exuberance in the Worlds of Peril, published posthumously in 2022. |

| 6 | Jessica Hernandez opts to use “healing” in place of “conservation” given the latter “is a Western construct that was created as a result of settlers overexploiting Indigenous lands, natural resources, and depleting entire ecosystems” (Hernandez 2022, p. 72). Hernandez contends that conservation functions as a tool for white people, namely men, to superimpose their belief systems and dominant ideologies on the natural world and Indigenous people as a means of controlling them. Hernandez notes that no direct translation for “conservation” exists in her familial Zapotek dialect, given the term’s colonialist origins. Instead, Hernandez uses “healing” or “caring” to describe her culture’s relationship to wilderness, wildlife, and other natural resources, the conservation of which “was not needed before colonization” (Hernandez 2022, p. 75). Thus, when I refer to “healing” and “caring,” I do so in a concerted effort to shift away from the language of settler colonialism and towards a dialogue of kinship. |

| 7 | Hernandez is careful to note that Indigenous knowledge systems, like Indigenous science, “cannot be defined by one sole definition as it consists of all Indigenous knowledge—locally, regionally, and globally. While some Indigenous knowledges can share similarities with one another, they differ based on geographic location of each tribe, nation, or community” (Hernandez 2022, p. 109). In Fresh Banana Leaves, Hernandez uses her preferred term—Indigenous science—interchangeably with others, including “tribal science, Indigenous knowledge, traditional ecological knowledge, Indigenous ethnoscience” (110), and other terms Dillon lists as well, such as “Indigenous scientific literacies [and] ‘traditional ecological knowledge,’ or TEK” (Dillon 2012, p. 7). Within this essay, I generally refer to Indigenous knowledge systems using Hernandez’s preferred descriptor for the sake of consistency and because of the rhetorical efficacy the term holds when juxtaposed with Western science. |

| 8 | Here, I use “constructive hope” in contrast with “hope based on denial” as described by Maria Ojala in her study “Hope in the Face of Climate Change: Associations with Environmental Engagement and Student Perceptions of Teachers’ Emotion Communication Style and Future Orientation” (2015). In the context of climate change, constructive hope entails “meaning focused strategies consisting of actively putting trust in different societal actors [politicians, researchers, themselves, and others] but also positive reappraisal, where the problem was acknowledged, but where the young also were able to switch perspectives and see positive trends concerning climate change” (Ojala 2011, p. 6–7). Hope based on denial, on the other hand, de-emphasized “the seriousness of climate change by claiming that the problem is exaggerated or that it does not concern oneself” (Ojala 2011, p. 7). Moreover, constructive hope avoids the valid concerns about hope Dr. Kyle Whyte (Citizen Potawatomi Nation) unpacks in a 2020 interview conducted by Britt Wray, entitled “How Can You Hope When You’re Coming Out of Dystopia?” In the interview, Whyte finds problematic hope origniating from a position of privielge, devoid of action, and expressed wishfully, wistfully, as a “hope for a miracle” (Whyte qtd in Wray 2020). Within climate discourse, this type of hope manifests, in part, in the face of popular media’s “obsession that certain dominant groups and culture have with this idea that the human species is on the verge of being extinct,” or with what I and others cited within my paper refer to as a singular apocalypse. Not only, then, does this wishful hope ignore the multiplicity of Indigenous appocalyposes, but it can also generate what Wray calls “the ultimate bystander effect,” displacing action onto those without the privilge of hoping for a miracle from a place of comfortable complacemeny. Constructive hope, on the other hand, acknowledges the climate crisis, one’s complicity in it, and calls for creative, collaborative solutions. Constructive hope is “tied to action” and the knowledge that “many hard lessons are still in store” for those engaged in constructive hope “as they learn from what happens when their actions contest oppressive forces” (Whyte qtd in Wray 2020). |

| 9 | In support of this claim, Hernandez references disparities in who is receiving doctoral degrees in the sciences as well as who is granted access to research projects based in Latin American countries home to Indigenous populations. Citing Josh Trapani and Katherine Hale’s article “Science and Engineering Indicators” (2019), Hernandez notes, “According to the National Science Foundation, in 2017, 71.1 percent of doctoral degrees in the sciences were awarded to whites in comparison to the 0.4 percent awarded to Indigenous students” (Hernandez 2022, p. 83). |

| 10 | Whyte, et al. make a similar claim in their essay “Indigenous Lessons about Sustainability Are Not Just for ‘All Humanity’”, noting, “For many Indigenous peoples[…]plants, animals, and ecosystems are agent bound up in moral relationships of reciprocal responsibilities with humans other nonhumans” (Whyte et al. 2018, p. 156). |

| 11 | In collaboration with the folk singer Toshi Reagon, Gumbs set eleven of the meditations to music composed by Reagon. The project, entitled “Long Water Song: Marine Mammal Meditations”, is available for purchase on Bandcamp’s website. Meditation Two: Breathe can be streamed for free here: https://soundcloud.com/longwatersong (accessed on 5 May 2022). |

| 12 | On this history, Robin Wall Kimmerer writes, “In traditional ways of knowing, one way of learning a plant’s particular gift is to be sensitive to its comings and goings. Consistent with the indigenous worldview that recognizes each plant as being with its own will, it is understood that plans come when and where they are needed” (Kimmerer 2003, p. 103). |

| 13 | In their thesis, Jackson shares the following: “Biidaaban translates as dawn, or more specifically, the very first light before dawn. As explained by Anishinaabeg scholar, writer and author Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, who broke down the three parts of the word, philosophically the word references the past and the future collapsing in on the present. ‘Bii’ means the future is coming at you with full force, ‘daa’ means the present or home, and “ban” is a suffix that would be added to someone’s name after they’ve passed on to the spirit world” (Jackson 2019, p. 4). |

| 14 | In their detailed report of the formation, implementation, and outcomes of Biidaaban as a community healing model, Dr. Joe Couture and Ruth Couture remark upon the practice’s purpose for First Nations peoples’ individual and collective renewal, survivance, and flourishing. Of the simultaneous emergence of both the tribal casino and Biidaaban, Couture and Couture note, “Both faced initial obstacles specific to their development. Both officially came into being in 1996. It is, perhaps, the Creator’s way of placing the necessary tools for balance in the Mnjikaning community in order to fully utilize their individual and collective gifts and move their People from colonial devastation into a newer, more encompassing global role, one that will propel them forward as an Aboriginal beacon of caring, sharing and hope” (Couture and Couture 2003, p. 9). The parallels between Biidaaban as healing model and Biidaaban as character and film are noteworthy, indeed. |

| 15 | Strong’s film is not the only creative rendering that posits Biidaaban as an immersive experience. “Biidaaban: First Light,” an interactive art installation by Elizabeth Jackson, uses virtual reality technology to place the user in a projected future Toronto “where nature has begun to reclaim the city and where humans are living in keeping with the knowledge systems of the original people of the territory” (Jackson 2019, ii). |

| 16 | Here, Kirksey is referencing Isabelle Stenger’s concept of “reciprocal capture” as defined by Stenger in their book Cosmopolitics I. |

References

- Brodie, Nathaniel, Charles Goodrich, and Frederick J. Swanson. 2016. Forest Under Story: Creative Inquiry in an Old-Growth Forest. Washington, DC: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bubandt, Nils, Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, and Elaine Gan. 2015. Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Monsters of the Anthropocene. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Couture, Joe, and Ruth Couture. 2003. Biidaaban: The Mnjikaning Community Healing Model. Native Counselling Services of Alberta. Available online: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/bdbn/bdbn-eng.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Dillon, Grace L. 2012. Imagining Indigenous Futurism. In Walking in the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction. Edited by Grace L. Dillon. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, Julie. 2020. Creative Communication Approaches to Youth Climate Engagement: Using Speculative Fiction and Participatory Play to Facilitate Young People’s Multidimensional Engagement with Climate Change. International Journal of Communication 14: 2749–72. [Google Scholar]

- Fernside, Jeff. 2016. New Channel. In Forest Under Story: Creative Inquiry in an Old-Growth Forest. Edited by Nathaniel Brodie, Charles Goodrich and Frederick J. Swanson. Seattle: University of Washington Press, pp. 123–24. [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich, Charles. 2016. Entries into the Forest. In Forest Under Story: Creative Inquiry in an Old Growth Forest. Edited by Nathaniel Brodie, Charles Goodrich and Frederick J. Swanson. Seattle: University of Washington Press, pp. 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gumbs, Alexis Pauline. 2020. Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals. Edinburgh: AK Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Fiona. 2021. World’s Vast Networks of Underground Fungi to be Mapped for the First Time. The Guardian. November 30. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2021/nov/30/worlds-vast-networks-ofunderground-fungi-to-be-mapped-for-first-time?scrlybrkr=5b349368 (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Hernandez, Jessica. 2022. Fresh Banana Leaves: Healing Landscapes through Indigenous Science. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Elizabeth. 2019. Biidaaban: First Light. New York: York University. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmerer, Robin Wall. 2013. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmerer, Robin Wall. 2003. Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses. Corvallis: Oregon State University. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmerer, Robin Wall. 2016. Interview with a Watershed. In Forest Under Story: Creative Inquiry in an Old-Growth Forest. Edited by Nathaniel Brodie, Charles Goodrich and Frederick J. Swanson. Washington, DC: University of Washington Press, pp. 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- King, Ariel. 2021. The Joy Report Trailer. The Joy Report from Intersectional Environmentalist. Available online: https://www.intersectionalenvironmentalist.com/the-joy-report/trailer (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Kirksey, Eben. 2015. Emergent Ecologies. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Medak-Saltzman, Danika. 2017. Coming to You from the Indigenous Future: Native Women, Speculative Film Shorts, and the Art of Possible. Studies in American Indian Literature 29: 139–71, Special Issue of Digital Indigenous Studies, Gender, Genre, and New Media. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeker, Natania, and Antonia Szabari. 2020. Radical Botany: Plants and Speculative Fiction. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Sheri. 2018. Sacred Instructions: Indigenous Wisdom for Living Spirit-Based Change. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Naameh, Sarah. 2022. An Introduction to Eco-Anxiety. Circularity Community. Available online: https://www.instagram.com/p/CcLfsQlr/?igshid=YMyMTA2M2Y= (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Ojala, Maria. 2011. Hope in the Face of Climate Change: Associations with Environmental Engagement and Student Perception of Teachers’ Emotion Communication Style and Future Orientation. Available online: https://oru.divaportal.org/smash/get/diva2:1040256/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Oleksijczuk, Denise. 2021. Creative Ecologies: How Might We Live in the Ruins of the More-Than Human Anthropocene? Public 32: 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Deborah Bird. 2015a. Shimmer: When All You Love is Being Trashed. In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Monsters of the Anthropocene. Edited by Nils Bubandt, Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson and Elaine Gan. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. G51–G63. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Deborah Bird. 2015b. The Ecological Humanities. In Manifesto for Living in the Anthropocene. Edited by Katherine Gibson, Deborah Bird Rose and Ruth Fincher. Santa Barbara: Punctum Books, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Deborah Bird. 2022. Shimmer: Flying Fox Exuberance in Worlds of Peril. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, Karsten A. 2017. Decolonizing Political Ecology: Ontology, Technology, and ‘Critical’ Enchantment. Journal of Political Ecology 24: 125–43. [Google Scholar]

- Amanda Strong, director. 2018, Biidaaban (The Dawn Comes). Spotted Fawn Productions.

- Tedford, Matthew Harrison. 2020. Is a Non-Capitalist World Imaginable? Embodied Practices and Slipstream Potentials in Amanda Strong’s Biidaaban. Feminist Media Histories 8: 46–71. Available online: https://online.ucpress.edu/fmh/article-abstract/8/1/46/120185/Is-aNon-Capitalist-World-Imaginable-Embodied?redirectedFrom=fulltext (accessed on 5 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary. 2021. Available online: https://ojibwe.lib.umn.edu/mainentry/biidaaban-vii (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, Joshua, ed. 2020. Love after the End: An Anthology of Two-Spirit & Indigiqueer Speculative Fiction. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Printing. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, Kyle, Chris Caldwell, and Marie Schaefer. 2018. Indiginous Lessons about Sustainability Are Not Just for “All Humanity”. In Sustainability: Approaches to Environmental Justice and Social Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 149–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield-Hayes, Georgia. 2020. The Role of Story and Myth in Our Troubled Times. Wildculture. Available online: https://wilderculture.com/myth-and-storytelling/ (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Wray, Britt. 2020. How Can You Hope When You’re Coming Out of a Dystopia? Gen Dred. Available online: https://gendread.substack.com/p/how-can-you-hope-when-youre-coming (accessed on 5 May 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).