Abstract

As the global world produces new social problems and the continuously changing environment of work organizations calls for new modes of operation, there emerges a need for discussion forums to analyze and find practical solutions, involving the people concerned. This article examines, within the framework of realist evaluation, the potential of democratic dialogue, a Nordic method of workplace development, to generate outcomes that are put into practice in work organizations. Democratic dialogue is seen as a social program that, by providing the participants with new resources and new reasoning in work conferences and other dialogue forums, enables them to make new choices. The focus is on three Finnish action research networks applying democratic dialogue, and the recompilation of these cases along the Context-Mechanism-Outcomes formula of realist evaluation. Changes in the organizational patterns of communication, linked to the criteria of democratic dialogue and the design of work conferences, are identified and examined through the lenses of varied organizational concepts that elaborate the underlying processes generating change. The article suggests further research to compare cases with the same starting points but differing outcomes to trace the finer distinctions in the preconditions for accomplishing the desired objectives.

1. Introduction

Of late, management reforms have been traded from one country to another perhaps more intensively than previously, although, as Pollitt (2003) puts it, such international traffic is far from new. International interaction is also one of the most essential elements of research and development activities. Nowadays the European Union is also interested in gathering and disseminating ideas of new methods used in workplace development programs, or on a smaller scale in change initiatives at the workplace level (Eurofound 2015).

In this framework of management reform trading, we reflect on Finnish applications of democratic dialogue, a workplace development method that originated in Scandinavia. Democratic dialogue was adopted in Finland from the Swedish LOM (Leadership, Organization, Co-determination) program (Gustavsen 1991; Gustavsen and Engelstad 1986) and was practiced as an intervention method in workplace development deploying participatory action research (PAR). The context of democratic dialogue is that of work organizations and management cultures, referring to workplace democracy. Alasoini (2011) has highlighted action research as one group of methods used in ambitious workplace innovation, meaning collaboratively constructed changes in organizational and human resource management practices. This notion is well in accordance with Greenwood’s (2015) definition of action research as the strategy of using multiple theories and methods to promote democratic social change.

Democratic dialogue began to be used in Finland in the 1980s during the boom in action research (Buhanist et al. 1994), is still being used over 35 years later in organizational development issues usually related to the quality of working life and the productivity, and is reported to produce practical results (Hökkä et al. 2014; Syvänen et al. 2015; Leinonen 2016), although it has been modified over time. These modifications include changes in the intensity of the development processes and the concepts used. In the first large-scale PAR programs, democratic dialogue was practiced in conferences lasting up to one and a half days (Kasvio et al. 1994; Heiskanen et al. 1998). Nowadays, it is more customary to have mini-conferences—or rather workshops—that may last 3–6 h, but democratic dialogue or some other form of dialogue approach is applied (Kivimäki 2011; Hökkä et al. 2014). Brief—even momentary—dialogue workshops have been developed together with the participants in response to the demands of the current hectic work pace. The modifications include a new emphasis on the concept of “mere” dialogue and the emergence of rather diverse dialogical approaches without direct references to workplace democracy. Cases conducted along these lines, theories, and evaluations have been presented, for example, by Collin et al. (2015), and Heiskanen and Jokinen (2015).

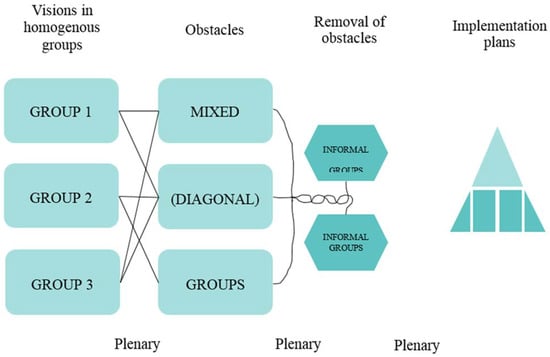

We argue that PAR applying democratic dialogue, as defined by Gustavsen (1991), may also be fruitful in the current circumstances characterized by continuous changes of work organizations. The basic notion is to acknowledge the significance of broad participation and labour-management cooperation in organizational development issues. When a supporting participatory action research project applying democratic dialogue is set up the members of the organization and the researchers work collaboratively towards new ways of operation. Gustavsen (1991, 2001) and Gustavsen and Engelstad (1986) present an operationalization of democratic dialogue as a set of criteria to be pursued in a process aiming to make an agreement of future joint action. Democratic dialogue is conducted in dialogue conferences, and also in other development groups. Along the progress of the conference from small group dialogues and plenaries about visions of desirable futures through obstacles and means of conquering the obstacles towards a concrete action plan the voice and work experience of the members of the organization are respected. Due to the regularly positive outcomes it seems worthwhile to determine the core elements of democratic dialogue that may contribute to change and thus encourage to maintain a continued interest in dialogical development approaches in the working life.

Habermas’s (1984) concept of communicative action is often advanced as a core assumption in theorizing democratic dialogue. Gustavsen (1991) concludes that the quality of all human thought and action is seen ultimately to depend on the patterns of communication between people. This is in accordance with Mumby (1988), who argues that organizational actors with positions high up in the hierarchy also have dominance over communication. While meanings are created and organizations are built in communication processes, power relations are also maintained and reproduced by communication that either supports or rejects different organizational experiences. From this point of view, it seems reasonable and practical to change the patterns of communication and to bring forward diverse experiences about work in the pursuit of desirable change. This is what democratic dialogue aims to do.

Nevertheless, Gustavsen (2001) noted that the unequivocal scientific-philosophical underpinning of democratic dialogue was being progressively abandoned in favor of a pragmatic one based on “what works”. We are interested in this pragmatic aspect of democratic dialogue and focus on the core of “what works”, especially in the Finnish context. The applications to be evaluated retrospectively were conducted at Tampere University, Work Research Centre.

2. Methods and Research Tasks

The application of democratic dialogue as a participatory workplace development method necessarily means intervening in the regular course of organizational life. By giving the members of work organizations a voice in their developmental issues, the PAR setting is appreciated in the realm of critical realism for having the potential to be an emancipatory, intensive, and engaged research approach, although Ackroyd and Karlsson (2014) do not recognize any distinctive critical realist type of action research. Critical realism is committed to finding potential but not readily observable mechanisms that have an effect in the social world (O’Mahoney and Vincent 2014, p. 10). This idea has been developed further, for example by Pawson and Tilley (1997), who have presented a procedure for realist evaluation used in connection with social programs. Their guiding principle is that social programs are theories of society where causal outcomes (O) follow from mechanisms (M) acting in contexts (C); this is known as the CMO-formula. Drawing on Ackroyd and Karlsson (2014) we see both participatory action research PAR and realist evaluation as practical projects of critical realism, a philosophy of science, that assumes an objective world and also that a part of the world consists of subjective interpretations.

The research setting becomes more complicated when large, theory-driven social programs take their place as a part of the context. We have a choice to make: Do we try to directly study how, why and in what circumstances democratic dialogue improved the outcome of participant organizations, or how, why and in what circumstances democratic dialogue impacted the ways of working and contributed to the improvement of the outcome (see Alvarado et al. 2017). Drawing on Dalkin et al. (2015) we choose the latter. Dalkin et al. (2015) have focused on Pawson and Tilley’s (1997) work concerning the content of mechanisms as a combination of resources offered by social programs and the participants’ reasoning in response to these new resources. Further, they see that the combination of resources and reasoning enables participants to make and sustain new choices, which in our case would mean new, dialogue related, ways of working and interaction at the workplace. Following Kazi (2014), we call those parts of the social program (democratic dialogue intervention) that the participants involve themselves and use as their resources, as “generative mechanisms”.

Based on the above arguments we adopt realist evaluation as our general framework—a guideline—in increasing our understanding of what works in democratic dialogue and thus are tackling the core issue of also other theory-based evaluations: how complex programs in complex contexts lead to changes in outcomes (Blamey and Mackenzie 2007). More specifically, we take PAR interventions applying democratic dialogue (Gustavsen and Engelstad 1986; Gustavsen 1991) to be equivalent to theory-based social programs and anticipate practical changes will take place by changing communication patterns (Habermas 1984) in the participating work organizations. Accordingly, we trace generative mechanisms that provide potential or even plausible explanations for the known outcomes of the democratic dialogue projects conducted in their historical contexts. We practice realist evaluation at the PAR case level, tied to the history of our cases, and do not claim to use realist action research like for example Westhorp et al. (2016). Their approach resembles greatly the classic action research cycles (Lewin 1948) during which the actors evaluate the planned solutions by learning from observing their effects and improve the solutions until they work as desired in the given context. On the other hand, we feel free to use existing theories of the phenomena studied, adding theory to data along the lines of critical realism (O’Mahoney and Vincent 2014, p. 18).

The defined research tasks are

- to re-compile PARcases conducted at Tampere University, Work Research Centre according to the CMO-formula by describing their societal and organizational contexts (C), the outcomes (O) together with the aims and practical results, and the mechanism (M) as applications of democratic dialogue, as reported in the data;

- to identify those aspects of democratic dialogue applications that the participants have interpreted further as generative mechanisms emerging from the participants’ new resources and new reasoning and to proceed toward potential explanations of what makes democratic dialogue work by adding existing theories to data as the basis for new, detailed research.

- The data consist of the final reports and connected research articles of the cases conducted by the authors. In the case selection, we ensured that the material include comprehensive descriptions of PAR interventions. The final reports and articles are based on field diaries of participant observation, organizational documents, questionnaires, recorded interviews, project group/task force memoranda, and work conference materials. Other data consist of a description of democratic dialogue by Kasvio (1990) and articles on the original Swedish LOM program.

- In carrying out this research the case reports and other data are re-read by using the separate factors of the CMO-formula as analytical tools. Therefore, the from case to case varying contexts (C), applications of democratic dialogue (M) and outcomes (O) produce new knowledge as they are structured in a new way. They give background to a more detailed analysis of democratic dialogue (M) as a process that might produce new resources and new reasoning (Dalkin et al. 2015) to the participants and thus give plausible explanations to the outcomes. In reporting this research the CMO-formulas are presented as split in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 and in Figure 1 in Section 3 and Section 4. Table 1 and Table 2 include two modifications of the formula; the case-specific aims concretize the broad frameworks of workplace development and practical results concretize the outcomes. Section 5 concentrates in the details of the operationalization of democratic dialogue (M) by Gustavsen (2001) as qualitative interpretations of the experiences of the participants. Section 6 discusses the results.

Table 1. The contexts, aims and outcomes of the networks.

Table 1. The contexts, aims and outcomes of the networks. Table 2. The practical results of the Networks.

Table 2. The practical results of the Networks. Table 3. The Democratic Dialogue applications and other research work in the networks.

Table 3. The Democratic Dialogue applications and other research work in the networks. Figure 1. The progression of the dialogue (work) conferences.

Figure 1. The progression of the dialogue (work) conferences.

In summary, the authors have a retrospective interest in democratic dialogue and they ask the question: why and how has the method worked? The cases to be studied are PAR networks representing three different sectors of the Finnish economy.

Network A (Health sector) was conducted in two phases involving all university hospitals (22 wards) in the early 2000s, and central and regional hospitals, health care centres, and private sheltered homes (nine organizations) between 2008 and 2010. Representatives of work safety and occupational health were involved in both phases. Applications expanded to the development projects conducted by universities of applied sciences.

Network B (Clothing Industry) also had two phases. Phase I involved four companies in the early 1990s and Phase II included seven companies from 1994 onward, including three from Phase I. Local trade union branches of clothing industry workers were active participants in the case. Applications expanded to gender and equality issues in Finnish workplaces.

Network C (Public services) was launched in 1991 as a national program of 14 projects with a diverse intensity of development work (core, satellite, short term). It continued in 1995 as a network with 25 participant service organizations until 2001 and has later attracted new participants and created spin-off activities. At the local level, it involves citizens/clients, human resource managers, trade union representatives, and political decision makers and at the central level representatives of labour market partners and action researchers from other research and education institutions.

3. Case Networks in Their Contexts (C), Development Aims, the Reported Outcomes (O) and Underlying Practical Results

As the Context-Mechanism-Outcome (CMO) formulas of realist evaluation (Pawson and Tilley 1997) imply, the context of any social program largely determines the potential and actual outcomes of the programs. The first case Networks applying democratic dialogue were launched in the early 1990s and continued in various spin-offs later, in the conditions of the Finnish recessions of the 1990s and 2008 and their aftermaths.

The societal and organizational contexts (C) that gave rise to the use of democratic dialogue in workplace development in Networks A–C, and their contexts interpreted as aims of the development work, as well as the reported outcomes (O), are summarized in Table 1, based on the information provided in the final reports.

In the interpretation of Table 1 it is also necessary to mention the funders as contextual factors: the Finnish Work Environment Fund (TSR), closely related to the central labour market organizations, three Ministries (Social and Health Affairs, Education and Labour), the Finnish Workplace Development Programmes (1996–2010), the Finnish Funding Agency for Innovation (Tekes), the European Social Fund, the Academy of Finland, and the participant organizations of Network C.

We may interpret that the societal pressures, combined with the problematic organizational context, had decreased employee well-being in the health care sector to a level that funding was allocated to launch Network A. In the private sector enterprises of Network B, the dominating societal context is the recession of the early 1990s, which created the impetus to launch PAR with ambitious objectives to find new competitive potential. Although the participant organizations of Network C have allocated financial resources to be involved, major funding came from public bodies. This matter has been discussed by Fricke (2011) who argues that PAR programs for work life reform stand no chance without being able to generate support from broad socio-political coalitions. This was also the case in Finland. Although not emphasized in the final reports, we should add to the societal contexts the national level labour-management cooperation and tripartite reform coalitions (including also the government) that supported participatory workplace development by providing sufficient financial funds.

Although the support in the societal context was secured the early PAR projects of Tampere University, Work Research Centre, democratic dialogue had to be accepted by those in a position either to grant or deny access to their organizations. Kasvio et al. (1994, p. 25) have reported about one case that accepted the researchers only to produce research material to support the local development activities and two cases that were interrupted at a very early stage due to the misbalance of the management type and the PAR approach during a severe budget crisis. Additionally, Kivimäki (2011) has reported experiences of the mismatch of the democratic dialogue approach with the top-down approach of cut-back management. Professional discrepancies are mentioned as constraints in the diffusion of local development ideas by Kalliola and Nakari (1999).

When access is denied or constrained at a very early stage, the democratic dialogue interventions cannot be carried out at all. When access is granted, there are usually sufficient supporting factors, and democratic dialogue produces practical results. This is the significant background experience of the authors, who want to understand what lies behind those results.

Table 1 also describes how the promises of the democratic dialogue interventions were fulfilled. In Network A, improvements were achieved in the flow of information, general interaction and cooperation, the progress of work and activities, the work climate, the acknowledgement of the employees’ opinions, and the relations between small employee groups. The employees thought that their opportunities to influence their working conditions had improved (Kivimäki et al. 2006, English summary). Many ideas were developed further to secure the smooth running and organization of work, the flows of information, working hours and rota planning, equipment safety, and working atmosphere, and to help the workers cope with interpersonal conflicts and the threat of violence, as presented by some clients (Kivimäki et al. 2006). Network B accomplished the desired changes in organizing production and the content of labour-management cooperation. In addition, it took steps toward international collaboration with all relevant stakeholders. A summary of the productivity improvements of the first projects of Network C is presented by Kasvio et al. (1994, p. 147) as increases in overall productivity consisting of economic efficiency and economic productivity (input/output measures), effectiveness at a long-term societal level and at the client level, and improvements in the internal capacity of the organization, including the quality of working life. The interpretation of the improvements in the quality of working life (Kasvio et al. 1994, p. 195) was done in the framework of increased labour-management cooperation and new forms of self-regulated work.

The positive outcomes of the networks do not mean that every case proceeded completely smoothly without any setbacks in the bottom-up approach when confronted by top-down management and professional positions. However, the positive outcomes can be interpreted as one precondition, together with favourable societal and organizational contexts, for consecutive funding and providing the researchers with opportunities to learn more about the contexts and the PAR methods.

In Table 2 we revisit the final reports and look for those practical results, concrete changes that underlie the compilation of the reported outcomes in Table 1. The practical results have found a permanent function in the organizations, at least to the extent that the new changes are evident. Therefore, we approach the ideas of generative mechanisms and discuss briefly the role of the organizational contexts as presented earlier in either promoting or constraining changes.

We can interpret from Table 2 that all organizational contexts allow democratic dialogue-driven development work to produce two very concrete new generative mechanisms: improving the information channels and offering on-the-job training that increases the information and knowledge of the employees. All the organizational contexts also allow cooperation and the crossing of organizational borders vertically and horizontally. This change is initiated by the design of the work conference, which involves a broad range of stakeholders, and may evolve towards a permanent way of planning and working. The organizational traditions start to hinder the changes when we look at the leadership styles and the status of hierarchies: private companies and public service organizations have been able to adopt ‘management by walking’ and to level the hierarchies, but this did not happen in the more rigid hierarchies of health care. However, autonomy was increased among the health care staff in the planning of working schedules, while the teams in the public service organizations were also given official decision-making powers (Kalliola 2003). According to Gustavsen (2017), this element of increasing autonomy at work, and the need to see workplace development as an issue on the societal level, has not only survived but also been strengthened since they were placed on the agenda decades ago.

The working conditions and quality of working life questionnaires from Networks A and C showed positive results, suggesting contributions from democratic dialogue in professional bureaucracies, and both networks produced results in the guides for practitioners. As the practical results highlight, the method was also appreciated in private companies, although the possible changes in working conditions were not measured. On the other hand, private companies were the only ones flexible enough to allow local bargaining as part of the development projects, and the health care network was the only one to modify the dialogical method used.

After establishing the main characteristics of contexts (C) and outcomes (O) of the CMO-formula, we proceed to investigate the mechanisms (M).

4. The Finnish Application of Democratic Dialogue: From Dialogue Conferences to Work Conferences (M)

Buhanist et al. (1994) trace the emergence of action research in Finnish working life to Nordic contacts among research-oriented office holders at the Ministry of Labour and the labour market partners. The university-based pioneers of Finnish action research learned the principles of democratic dialogue by reading research reports, journal articles, and books. Concrete applications were brought to practice by a learning-by-doing method (Fricke 2011). The main source in describing the method in Finnish is Kasvio (1990).

Kasvio (1990) refers to the work of Odhnoff and von Otter (1987) as one of the basic texts about the Nordic development approach, and to Gustavsen and Engelstad (1986) as a source for understanding the design of work conferences’, a concept adopted in Finland to cover ‘conferences applying democratic dialogue’. The conference participants came from organizations working in the same branch, as the strategy of the LOM program was to involve clusters of organizations in carrying out the development process (Gustavsen 1991).

In the Finnish context, the basic model of work conferences was presented as a purposeful gathering of participants from private or public work organizations who wanted to work together in their search for a favourable future and in the evaluation of their progress. Furthermore, the participants showed an interest in the often-hidden perspectives and capabilities of the entire staff. They appreciated local theories and organizational mapping (Kasvio 1990; Elden 1983) which were seen as tools to bring forward the unused resources of the staff. The participation of the staff was seen as a prerequisite for commitment and the emergence of a joint understanding about future action. This was the promise of the often publicly funded projects, which were expected to come to fruition by following the principles of democratic dialogue.

Kasvio (1990) outlines the epistemological and social scientific roots of democratic dialogue emphasizing equal opportunities to participate in the organizational change processes and the creation of feasible plans for future action. Below, one of the English-language versions of the criteria of democratic dialogue is presented (Gustavsen 2001, pp. 18–19; the numbering of the criteria is by the authors):

- Dialogue is based on the principle of give and take, not one-way communication.

- All concerned by the issue under discussion should have the opportunity to participate.

- Participants are under an obligation to help the other participants be active in the dialogue.

- All participants have the same status in the dialogue arenas.

- Work experience is the point of departure for participation.

- Some of the experience the participant has when entering the dialogue must be seen as relevant.

- It must be possible for all participants to gain an understanding of the topics under discussion.

- An argument can be rejected only after an investigation (and not, for instance, on the grounds that it emanates from a source with limited legitimacy).

- All arguments that are to enter the dialogue must be presented by the actors present.

- All participants are obliged to accept that other participants may have arguments better than their own.

- Among the issues that can be made subject to discussion are the ordinary work roles of the participants—no one is exempt from such discussion.

- The dialogue should be able to integrate a growing degree of disagreement.

- The dialogue should continuously generate decisions that provide a platform for joint action.

The work conferences were modelled as an interplay between small groups and plenaries that were conducted according to a design deduced from Democratic Dialogue (Kasvio 1990, p. 121). In the basic model the problems and flaws are put aside as the starting point is the desirable future within a time span of five years (Figure 1).

The visions of the desirable future were formulated in homogenous groups, consisting of participants with similar hierarchical or occupational positions. Therefore, managers, supervisors, shop-floor-level workers, representatives of trade unions and occupational health and safety, or occupational groups, from different organizations, but presumably sharing same interests and goals, conducted a dialogue within themselves in small groups. As all the other phases of a conference were steered by the vision phase, this composition was an important element in the design of the conferences.

All the visions were presented and submitted to a further dialogue in a plenary, after which diagonal groups, consisting of representatives of all the hierarchical or occupational positions present, defined the potential obstacles hindering the visions to come true.

The conference continued by discussing possible means to overcome the obstacles in freely mixed informal groups. Again, following a plenary, members of each participant work organizations gathered by themselves, as a community of work, to define organizational goals of their own.

The closing plenary summarized the ideas brought forward, looking for similarities and differences, and also for a common ground for some concrete action to be taken immediately by all, while the individual participant organizations were expected to carry on their plans within a proper time. Therefore, the democratic dialogue Criterion 13 was emphasized: there is a need to make conclusions of what should and could be done in order to improve the issues in question.

Initially, work conferences applying democratic dialogue were parts of development projects lasting 2–3 years. The criteria of democratic dialogue assign the researchers a facilitating role: researchers were not expected to adopt expert positions or to give any kind of lectures during the conferences, in line with the interpretation of Criterion 9. Only later, when the future plans were concretized in the workplaces, were the researchers expected to provide their input in the processes. This was criticized by Kasvio (1990), who wondered whether the strong emphasis on local knowledge would overrule the impact of relevant theories in the development work. Kasvio (1990) was also concerned about whether any normative procedures would free communication from the actual power structures.

In the UNI networks, the practice of democratic dialogue was encouraged in the official project groups, workplace meetings, and all other work groups that were assembled along the lines of representativeness (occupations, hierarchical levels) and stakeholder positions. The roles of participants were defined along PAR principles as research subjects, not objects. The researchers cooperated with liaison persons who knew the regular activities and the culture of their organizations. The official objectives (see Table 1) were transformed into a local need for change, and the substance of the interventions was planned and evaluated through the cooperation of the research subjects and the researchers. In some cases, the participants were real co-researchers (Harré 1979) producing and commenting on data, and in some cases co-authors as recently in Hökkä et al. (2014).

In PAR interested in communication patterns and the recognition of the participants as research subjects, the language spoken must have relevance to the participants’ lives. This was pursued, for example, in the first interviews charting the perspectives of the participants about the development issues and concepts used, and in feedback meetings discussing the results of the questionnaires (Kalliola and Nakari 1999; Heiskanen et al. 1998). A summary of the research approaches applied in Networks A–C is given in Table 3.

Network A built Phase II on the practical results of Phase I and relied on miniature work conferences, combining the basic four dialogues (Figure 1) into two. The participants agreed to carry out at least 2–3 of the new ideas within one year; this was monitored by a questionnaire. Network B maintained the original idea of the LOM program (Gustavsen 1991) by clustering participant organizations. The initial fieldwork and surveys in the four enterprises of Phase I played an important role in conducting the action research interventions, as the themes of work conferences were chosen based on these results. In Phase II, researchers stayed with the seven enterprises for some time, making observations and interviewing people from all occupational groups. Once again, this knowledge provided the background information for work conferences. Since the researchers had prior knowledge of the enterprises based on their fieldwork study, they could participate actively in the discussions, rather than merely offering resources. This pro-activeness was required, for example, in situations where discussions were regulated too much by managers. Furthermore, in tension-filled issues, such as pay systems, the active contribution of the researchers—in the form of asking questions and framing the issues—was needed to keep the discussions constructive instead of open conflicts (Heiskanen et al. 1998). In Network C, the clustering of public service organizations did not succeed: the participants gathered together and shared information only when organized by the researchers. A single organization of Network C, having a project of its own, usually participated in 2–3 conferences: objective-setting, mid-term evaluation, and the final evaluation accompanied by continuing the development without the researchers (e.g., Kalliola 2003). The contributions of evaluative mid-term and final conferences as a form of participatory evaluation to learning at work and to accomplish the change visions (Suárez-Herrera et al. 2009) would be worthy of further research, but they are left beyond the scope of this research.

5. Generative Mechanisms Related to Democratic Dialogue (M), and Adding Theory to Data

We have assumed a program theory of democratic dialogue in which changing mostly top-down communication patterns of organizational communication produces changes in the way organizational tasks are conducted and how people perceive them. To find the potential of democratic dialogue to create and maintain organizational changes, we interpret the data within the framework of new resources, reasoning, and choices (Pawson and Tilley 1997; Dalkin et al. 2015). We identify those changes in the patterns of communication that the participants appreciated as having further potential in producing change, and name them as the potential generative mechanisms that may underlie the emergence of practical outcomes. (N.B. In the data, the concept of the generative mechanism is not used.) We continue by adding theory to data, asking what concepts and theories are required—or at least helpful—in understanding the potential underlying processes generating change and allowing eclecticism in terms of the ideas of critical realism (Ackroyd and Karlsson 2014).

5.1. Offering Dialogue Forums to Work Organizations (Dialogue Interventions as a Whole)

The democratic dialogue approach involves the establishment of a new type of communication forum that organizations do not usually have. Often hospitals and other health care work organizations—typically characterized by a continuous lack of resources (staff, money), an abundance of daily routines, a hectic workspace, and shift works—have no forums at all for reflecting upon work together. Therefore, the dialogue intervention in Network A was a type of resource that was able to respond to the needs to plan the work together, establish ground rules, and redistribute responsibility, aiming to secure the smooth running of the hospital, health centre, and sheltered home services (Kivimäki et al. 2006; Kivimäki 2011)

Exercising influence together and participation increases the motivation to work. The support from outside is important in the development work. We have to evaluate our activities continuously and this is a good way to mobilize the workplace as a whole.(Upper supervisor, 2005, Network A)

It would be worth continuing in the same way, since it [development approach] could improve the quality of work and commitment to work(Respondent 1, 2009, Network A)

Similar types of recognition of the new resources and new reasoning were also reported in Networks B and C. In Network B, the discussions additionally brought up issues and problems that were hidden or unrecognized in the daily routine, while the continuous need to secure open and effective information flows was regularly addressed in Network C.

Many such flaws were raised that one would not even expect.(Supervisor, 1998, Network B)

I hope the workplace meetings will survive and the information channels will be improved further. It is surely possible to make decisions jointly, but it requires a new kind of openness, a reciprocity. I am rather hopeful.(Employee, 1993, Network C)

The positive feedback of the members of the Networks about the opportunity to present their own perspectives and to hear those of others may be interpreted from the point of view of necessary but missing dialogue arenas. The members of Network A in particular greatly appreciated the small-scale dialogue conferences as a significant response to their need for interaction within their organizations. The role and functions of the dialogue conferences in organizational settings have been elaborated on, for example, by Pålshaugen (1999), who sees dialogue conferences as part of ‘development organizations’, attempts to build internal public spheres for companies. Pålshaugen (1999, pp. 39–40), believes that companies may lack a joint forum to allow all organizational members to bring their concerns to further discussions for the acknowledgement of others. Along these lines of thought, companies would gain from development organizations that could expose the members of formal bodies to new insights and experiences usually discussed only in the sub-public arenas of co-workers. In Network A, the dialogues on new public spheres contributed to a remarkable amount of practical changes that the top management could not have otherwise initiated.

Pålshaugen (1999) sees dialogue as a basic element of organizational studies. While Pålshaugen (1999) relies on the idea of discussing the concerns of various individuals and collectives in public spheres, Colbjørnsen and Falkum (1998) have gone further. They conceptualize organizations as an interplay of production (employees, supervisors, management), bargaining (employer representatives, shop stewards) and development systems. They argue that any changes result from the negotiations between these three systems. In the framework of generative mechanisms, this notion is stronger than discussions on public forums without any obligations to take them into account by the decision makers.

The inclusion and the presence of all three systems in dialogues explain the securing of the outcomes of democratic dialogue in work conferences, task forces, workplace meetings, and other types of group work initiated in the Networks. Along with the interpretation of Criterion 2 of the democratic dialogue, the identification of stakeholders covered all the systems and hierarchical levels of the participant organizations. In Network A, the connection with trade unions was built through the occupational health and safety representatives (Kivimäki et al. 2006; Kivimäki 2011), whereas in Network B the core issue of bargaining—in terms of wages—was brought to the agendas of the dialogue forums. The progress of these issues was monitored in evaluative questionnaires. In some companies, the dialogues had continued locally and resulted in pilots and renewals as the bargaining parties reached solutions compatible with the changing demands of work (Heiskanen et al. 1998). In the case of the six participant organizations of Network C working together as a learning network, a conceptualization of Colbjørnsen and Falkum (1998) was used as a learning task: the participants investigated how the production, bargaining, and development organizations were connected in their home organizations (Kalliola and Nakari 2006) and the findings were put into practice by sharing information and power between these systems in local development work.

Since 1997, a day care case in Network C has been almost continuously involved in dialogue-based development to meet the needs of ongoing organizational change (Kalliola and Nakari 2008; Syvänen et al. 2015). In 2005–2006, a challenging transformation from a public service organization toward a purchaser-provider model took place. The involved union branch appreciated the opportunity to influence the content of work in addition to the very preliminary plans for bonus pay and gainsharing. In addition, the trade union branch appreciated the commitment of the top managers, and the pilot progressed according to the tight timetable given (Kalliola and Nakari 2008).

When the pilot [of the contractor model] really got started, it was a part of a larger project [Network C] where the participation of the staff was emphasized. At the beginning, there was a questionnaire, a digital one, and so the number of respondents was not very high [the response rate was 57%]. But it was an opportunity to express one’s worries about the changes to come. And I really think that the top manager and also the team leaders took it very seriously and they tried to inform us more of what will change and what will not change. After that, there was a work conference aiming to make action plans for every team to reach a new level of operation. Afterwards, it seems that the input of team leaders had been quite strong, and it was realized that there must be more of this kind of listening to the staff. In the task force, there are members who see that the participation of the staff is automatically included in the purchaser-provider model. And I said that it is not automatic: participation will emerge if it is allowed.(Shop steward, 2005, Network C)

A municipal enterprise providing infrastructure services was being transformed into a limited company. It was organized as three operating teams with development organizations, but without separate task forces. Shop stewards carried a combination of roles: they were both professional employees with their regular duties and union representatives. Although they saw that there may have been too much pressure ‘from above’ to accept the idea of the company, they shared the opinion of the top manager regarding the usefulness of dialogues in developing the organization.

Let’s imagine a situation where we would not have this type of system—surely we could not promote the current development work as well as now.(Top manager, 2005, Network C)

I see that we, together with the employer [top manager], recognized the problems we have and agreed to meet more often to solve them.(Shop Steward, 2005, Network C)

The connections between production, bargaining, and development systems can support the dialogues to be carried out in practice by involving “the right people”: the staff with concrete development ideas based on their work experience, the decision makers with authority, and the trade union representatives as potential supporters or opponents of the changes. Correspondingly, in development work focusing specifically on employee well-being, the support of occupational health and safety is also important.

This [method] stops one to think and to solve the problems of the work units, to develop. Otherwise, the working days are so busy that one has no time to reflect on issues during the regular pace.(Occupational health and safety officer, 2005, Network A)

We see the interplay between production, bargaining, and development systems as being closely related to Lawler’s (1987) idea of high involvement management, a productive factor that can be achieved only by redistributing information, knowledge, power, and rewards. Lawler’s (1987) idea corresponds with the basic principles of democratic dialogue.

Walton and McKersie’s (1965) classic notion of integrative bargaining may have explanatory potential in this matter. In the process of integrative bargaining, the partners with opposing or at least differing interests—such as managers and the trade union representatives—try to arrive at common objectives and the means to achieve them. As the conduct of democratic dialogue usually covers issues that derive from production-related matters and ways of delivering services, the common objectives and action plan are inherent in the dialogues. An example of this is a genuine client orientation that could be used as a guiding principle in planning joint actions (Kasvio et al. 1994; Heiskanen et al. 1998; Kivimäki et al. 2006)

5.2. Offering Learning Space and Learning from Others (Criteria 1, 7, and 10)

In the evaluation of the potential effects of democratic dialogue, understanding the concept of dialogue is vital. In Criterion 1, dialogue is explained as the process of giving and taking instead of one-way communication, and in Criterion 7, the aim to learn is fully explicit. Participants frequently seem to find at least some common elements in the other participants’ experiences, but they may also uncover totally new perspectives, and these contribute to the process of mutual learning. Criterion 10 counsels the participants to accept the potentially better arguments of others, and thus widen the scope of learning.

The project provided resources also for my own work.(Representative of occupational safety and health, 2005, Network A)

[In work conferences] one learns to appreciate the work of others and new things.

In this type of meeting, many things get clarified when we gather together and work out issues.(Respondents 3 and 4, 2009, Network A)

However, following Gherardi (2001), we do not assume learning to be synonymous with change, as changes can take place without learning and learning may not give rise to change. Instead, in the sphere of democratic dialogue that is built on the participants’ work experience, ‘the domain of learning is that of practice, consisting of knowing and doing’ Gherardi (2001). When the knowing and doing of participants is brought to joint forums, dialogue may lead to learning.

The genuine cluster setting of Network B was also visible in the evaluations of the dialogues. In addition, managers, supervisors, and shop-floor-level workers valued the opportunity to hear about the problems and solutions of other enterprises:

[The work conferences] provided a lot, even unexpected things.(Manager, 1998)

The solutions [presented in the conferences] gave us reasons to think.(Shop-floor-level worker, 1998)

5.3. Increasing Agency by Involving Oneself in the Dialogues (Criteria 2–6 and 8–9)

The inherent values emphasizing the work experience of every participant in the main body of the criteria were significant to the grass-roots-level employees. When they saw the dialogue forums enabled (or sometimes obliged) them to express their perspectives and to take a stand to do this, they realized they had the resources to be active agents in their work organization.

In Network A, this acknowledgement of the employees and their opinions was of great importance in the results of the evaluative questionnaires. The employees clearly expressed that their opportunities to influence their working conditions had improved (Kivimäki et al. 2006; Kivimäki 2011).

When an employee sees that she has been heard and there exists a possibility for discussions with supervisors, the positivity of the atmosphere increases, although it is not always possible to have an influence at the practical level.(Respondent 5, 2009, Network A)

In Network B, the shop-floor-level workers in particular valued the emphasis on interaction in the work conferences, which they regarded as an empowering element:

This has given us courage for discussions.(Shop-floor-level worker, Network B, 1998)

Hökkä et al. (2014) use the concept of occupational agency to cover the influence, choice-making, and stand-taking of individuals or working communities in the matters of work and occupational identity. They see that members of present-day work organizations may need support both at the workplace level—for example, in work conferences—and at the individual level—for example, via intensive identity work—to be able to cope with the many ongoing structural changes.

5.4. Enabling the Expression of Individual and Group Interests (Criterion 2 and Homogenous Groups)

In addition to the potential to increase agency, Criterion 2 encourages the participants to express and combine their individual interests into a future vision in homogenous groups (Figure 1). Actually, the dialogues in the homogenous groups are highly significant for the whole process, since the visions form the basis of the following dialogues. As professional or occupational boundaries and identities are often seen as a constraint to genuine client orientations in the rank order of occupations (Svensson 2005), the members of these groups use the resources offered by democratic dialogue to express their views. Collin et al. (2015) have also found that work conferences in hospital settings bring forth new suggestions about ways to strengthen the role of all professionals groups in patient care.

In one case in Network C, there is evidence of the incorporation of different occupational interests with new work organizations in a team-building process involving home care workers and nurses. Toward the end of the process, the role of the nurses was allowed to vary between teams, as reported in Kalliola (2003). In the day care case moving toward the contractor model, Kalliola and Nakari (2008) report that the input of occupational groups in the new models of the day care centres balanced the collective and individual practices.

Occupational practices will be harmonized in favour of the children, without standardization, and the special knowledge of individual staff members will be positively utilized to promote the service quality and the performance of the whole profit centre. Training needs and options would be discussed in the context of profit centre, not a day care centre.(Kalliola and Nakari 2008, p. 123)

In Network A, the staff being listened led to improvements in the relationships between small occupational groups, and in some cases, the doctors were also involved:

Even a couple of doctors were involved. Usually the doctors position themselves outside the working community.(Representative of occupational safety and health 2005, Network A)

5.5. Making Use of the Dialogues Enhances Trust and Commitment (Criteria 11–13)

In a work conference, after hearing about the obstacles and available means, and alongside learning, the dialogue should be able to integrate the various perspectives to create a joint plan that can be carried out. It is after the conferences that the crucial phase comes—turning words into action. If this does not happen, the participants will usually be frustrated and lose their potential commitment to further dialogues. The following comments were expressed in the cases of Network A, where the ideas developed in work conferences were not carried out—or had delays—within the following year:

There is talk and there is talk, but nothing happens at the practical level.

It feels like all the efforts [on the dialogue forums] were in vain when nothing happens.

It is not worth continuing the development work, since the situations [work conferences] are not real.(Respondents 6–8, 2009, Network A)

The ‘reality’ of work conferences, as well as other dialogue forums, may be supported only by carrying out the plans. In Network A, where actually many good practices were developed during the first university hospital project and modified further with the other health care organizations, the staff appreciated its influence on the changes made, and this contributed to improvements in the work atmosphere (Kivimäki et al. 2006; Kivimäki 2011).

It is good to make decisions together; the motivation to carry out the decision is better.(Respondent 9, 2009, Network A)

In Network B too, a number of the ideas generated in the work conferences were put into practice. New solutions for wage systems were sought out, educational schemes were compiled, and new training schemes were started. There was an increase in management by walking, meaning that the managers could familiarize themselves more closely with the daily issues of production, and some improvements in physical environments were also made. Almost everywhere, issues of communication were highlighted in the discussions as new resources and improvements were noticed in this area. The general feeling of an increase in open discussions and concomitant improvements in the organizational climate had positive effects on the cooperative planning of production and joint problem-solving. New resources, reasoning, and choices can be identified in the discussions and feedback evaluations of Network B:

Courage and self-confidence to talk about issues has increased.(Shop-floor-level worker, 1998)

A feeling has developed that we can solve problems together.(Shop steward, 1998)

As illustrated earlier by the day care case (Network C) changing to a contractor model, events progressed efficaciously when the staff realized that they were actually being heard. Their concerns were taken into account, renewal plans created in the dialogue conferences of the pilot organizations were carried out, and the staff got on-the-job training, as outlined in the conference. The words put into action enabled trust: the top managers, who needed the input of the staff, committed themselves to the change project, and the staff was ready to adopt new practical activities. After a successful pilot project, democratic dialogue was adopted as a tool to facilitate the change in the whole organization (Kalliola and Nakari 2008).

Furthermore, the mechanism of practical changes creating trust can be linked to Colbjørnsen and Falkum’s (1998) approach of involving development organizations with production and bargaining systems. The approach may secure the authority (top managers of the production system who also control budgetary resources and the main actors of the bargaining system controlling the degree of resistance) of the development projects to take action according to the plans made in dialogue forums, and it can be counted as a mechanism for enabling change. Lewin’s (1958) idea of gatekeepers supports this notion partly: the relevance of the involvement of gatekeepers is based on their position as actors that others follow. As actual gatekeepers may exist in any organizational group, it is important to find them in the preparatory negotiations before PAR is launched, and this is also a matter for the organizational context of PAR.

Lewin (1958) offers one more framework to consider. The final objective of the criteria of democratic dialogue, as expressed by Criterion 13, is a close analogy to Lewin’s (1958) group decision, a procedure that results in the responsible and committed action of the participants after discussions about the need for change.

Commitment as a generative mechanism may function at any level from the individual to the many types of collectives. When the criteria of democratic dialogue are acknowledged as obligatory, they can be interpreted as creating a new kind of regulative space (Scott 1995) that promotes the realization of the plans (Kalliola and Nakari 2008). The participants will gain experience of this when work conferences—or other dialogue forums—are adopted as a regular practice.

In Networks A–C, a sufficient number of participants have found new resources and new ways to reason, and they have made new choices to carry out the plans created in the dialogue forums. In addition, they have been in positions to ensure the practical actions. No practical outcomes would be possible without the participants, since the action researchers are not in a position to accomplish such changes.

6. Discussion

The recompilation of the project documents of Networks according to CMO-formula accentuated the significance of the favorable societal and organizational contexts (C), which is in line with the basic assumptions of realist evaluation (Pawson and Tilley 1997). The role of government in setting strategic goals for ministries as well as providing funding have been essential elements in supporting democratic dialogue and other PAR interventions in the workplace in order to resolve the survival and quality of working life issues caused by the recessions of the 1990s and in 2008. The adoption of especially democratic dialogue was facilitated by the cooperation of labour market partners who found an agreement about the necessity of change and favoured any steps towards more participatory forms in management styles. These interpretations get support from Lawler (1987, pp. 216–17), who names an urgent, recognized need to survive as an underlying factor in successful organizational changes. Currently the need to survive is a permanent contextual factor that may encourage Finnish work organizations, valuing their human resources, to adopt dialogue-based workplace development methods although the larger societal context is not as favourable as during the conduct of Networks A, B and C.

The present societal context with an emphasis on global economic competition and efficiency may challenge the basic idea of democratic dialogue. However, the method has proven to be malleable without compromising its basic components. The creation of future action plans by hearing all of those concerned, although sometimes through representatives, has maintained its position as a core element of also ‘mere’ dialogical workplace development methods, without any emphasis on workplace democracy as such. For example, in the spin-off project of Network A (Table 1), democratic dialogue was modified toward a more general dialogical approach in which developmental dialogues were practiced at two levels: among organizations offering occupational health and safety services and their client companies and also forums including researchers (Kivimäki et al. 2015). A connected project also showed the malleability of dialogue-based approaches: well-being at work was developed by combining individual reflections with workplace-level dialogues (Syvänen et al. 2015).

The heritage of industrial democracy as a driving force of democratic dialogue and other forms of PAR in the workplaces calls us to look at the organizational culture of Finnish workplaces more closely. Although working life has undergone numerous changes of late, features of authoritative management in the Finnish leadership styles were traced as late as 2010 by Lämsä (2010) in her comparison of the traditional Finnish and Swedish leadership styles, with Sweden being the original home culture of the LOM program. This information seems to offer one explanation for the popularity of democratic dialogue in Finnish working life: it is favoured by employees as a compensation for the deficiencies of the leadership. From the perspective of the management, democratic dialogue may be seen as a useful approach in situations where the management really needs the input of the employees and wants to avoid antagonistic resistance. Basically, democratic dialogue is a multiple level concept and phenomenon. It may be understood as an abstract high-level societal aim of ideal speech situation (Habermas 1984), a vision accompanied by a compatible strategy of leadership styles and participation, pursued by the management or the staff, or both (the idea of workplace democracy) or concrete action (Gustavsen 2001). In our research, democratic dialogue takes the form of concrete action as an integral part of participatory action research and is evaluated as a mechanism. Our evaluation is that democratic dialogue is a mechanism (M) that is able to produce new, generative mechanisms leading to change, to practical results and to desired outcomes (O). The change generation ability is linked to the 13 criteria and to the design of conferences, both building on broad participation and jointly agreed future plans to be carried out. Broad participation may be interpreted as a form of co-design advocated by Westhorp et al. (2016) in their realist action research approach.

In the interplay of small groups and plenaries of the conference the first two dialogues (visions and their obstacles, Figure 1) are significant especially for people with positions low in the hierarchy and consequently with little autonomy. The proper conduct of the conference secures their voices to be heard, and in addition, to be taken seriously, when the visions of every small group are dealt with respectfully and they all form a basis for further dialogues, concrete planning and learning from others. We conclude that democratic dialogue has a capacity to integrate work and learning (to give new resources and reasoning), and to transform words into action (to make new choices), by changing the patterns of organizational communication (Habermas 1984; Mumby 1988). The new steps taken may have even more effect when they are embedded in everyday management and leadership styles, as pursued by the project task forces and workplace meetings.

In addition to the thinking of Habermas (1984) and Mumby (1988) our evaluation points towards numerous potential theoretical interpretations and explanations of the change-generating mechanisms connected to democratic dialogue. Our study has taken us amidst organizational theories that seem to complement rather than exclude each other. We have added theory to the data by using multiple theoretical lenses to point out the diverse influences that affect the outcome (O’Mahoney and Vincent 2014) of the applications of democratic dialogue. Relying on only one conceptual framework will leave many organizational features unexamined. Additionally, one cannot ignore the potential of workplace democracy as a concretely practiced organizational value in generating the change.

In this research, the focus is on large, networked, and well-documented successful cases. We suggest further studies on closely comparable cases with different outcomes: in order to trace fine distinctions between successful and less successful cases, ‘the new resources, new reasoning, and new choice’ aspects should be combined with the outcome evaluations of PAR projects (Pawson and Tilley 1997; Dalkin et al. 2015). Additionally, primary data collection about the criteria of democratic dialogue and the design of conferences as a theory of ‘productive participation’ could be conducted along the lines put forward by Manzano (2016). In addition, when applying realist evaluation there are difficulties in the definition of the context and the mechanism since they are truly intertwined—a supportive context may be interpreted as a part of the mechanisms. This challenges the researchers to clearly explicate their CMO formulas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and investigation, S.K., T.H. and R.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K. and T.H. and visualization, R.K.

Funding

The authors received no external funding for the authorship of this article. The funding of the Networks A–C under study is mentioned in the Section 2 of article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ackroyd, Stephen, and Jan Ch. Karlsson. 2014. Critical Realism, Research Techniques, and Research Designs. In Studying Organizations Using Critical Realism. Edited by Paul K. Edwards, Joe O’Mahoney and Steve Vincent. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 21–45. [Google Scholar]

- Alasoini, Tuomo. 2011. Workplace Development as Part of Broad-Based Innovation Policy: Exploiting and Exploring Three Types of Knowledge. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies 1: 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, Natasha, Stephanie Honey, Joanne Greenhalg, Alan Pearman, Dawn Dowding, Alexandra Cope, Andrew Long, David Jayne, Arron Gill, Alwyn Kotze, and et al. 2017. Eliciting Context-Mechanism-Outcome Configurations: Experiences from a Realist Evaluation Investigating the Impact of Robotic Surgery on Teamwork in the Operating Theatre. Evaluation 23: 444–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blamey, Avril, and Mhairi Mackenzie. 2007. Theories of Change and Realistic Evaluation. Peas in a Pod or Apples and Oranges. Evaluation 13: 439–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhanist, Paul, Antti Kasvio, Timo Kauppinen, and Maarit Lahtonen. 1994. Finnish Action Research. In Action Research in Finland. Active Society with Action Research; Labour Policy Studies 82. Helsinki: Ministry of Labour, pp. 15–41. [Google Scholar]

- Colbjørnsen, Tom, and Elvin Falkum. 1998. Corporate Efficiency and Employee Participation. In Development Coalitions in Working Life The "Enterprise Development 2000" Program in Norway. Edited by Björn Gustavsen, Tom Colbjørnsen and Øyvind Pålshaugen. Dialogues on Work and Innovation DOWI 6. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Collin, Kaija, Susanna Paloniemi, and Katja Vähäsantanen. 2015. Multiple Forms of Professional Agency for (Non)Crafting of Work Practices in a Hospital Organization. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies 5: 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkin, Sonia Michele, Joanne Greenhalgh, Diana Jones, Bill Cunningham, and Monique Lhussier. 2015. What’s in a Mechanism? Development of a Key Concept in Realist Evaluation. Implementation Science 10: 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elden, Max. 1983. Democratization and Participative Research in Developing Local Theory. Journal of Occupational Behaviour 4: 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. 2015. Third European Company Survey Workplace Innovation in European Companies. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, Werner. 2011. Socio-Political Perspectives in Action Research. Traditions in Western Europe—Especially in Germany and Scandinavia. International Journal of Action Research 7: 248–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, Silvia. 2001. From Organizational Learning to Practice-Based Knowing. Human Relations 54: 131–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, Davydd J. 2015. An Analysis of the Theory/Concept Entries in the SAGE Encyclopedia of Action Research: What We Can Learn about Action Research in General from the Encyclopedia. Action Research 13: 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsen, Björn. 1991. The LOM Progman: A Network-Based Strategy for Organization Development in Sweden. In Research in Organizational Change and Development. Edited by Richard W. Woodman and William A. Pasmore. Greenwich and London: JAI Press, pp. 285–315. [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsen, Björn. 2001. Theory and Practice: The Mediating Discourse. In Handbook of Action Research: Participatiave Inquiry and Practice. Edited by Peter Reason and Hilary Bradbury. London: Thousand Oaks and New Delhi: Sage, pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsen, Björn. 2017. General Theory and Local Action: Experiences Form the Quality of Working Life Movement. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies 7: 107–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsen, Björn, and Per H. Engelstad. 1986. The Design of Conferences and the Evolving Role of Democratic Dialogue in Changing Working Life. Human Relations 39: 101–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1984. Theory of Communicative Action, Volume One: Reason and the Rationalization of Society. Translated by Thomas McCarthy. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harré, Rom. 1979. Social Being: A Theory of Social Psychology. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Heiskanen, Tuula, and Esa Jokinen. 2015. Resources and Constraints of Line Manager Agency in Municipal Reforms. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies 5: 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiskanen, Tuula, Riitta Lavikka, Leena Piispa, and Pirjo Tuuli. 1998. Joustamisen Monet Muodot. Pukineteollisuus Etsimässä Tietä Huomiseen. [In Search of Flexibility – Building Perspectives for the Textile and Clothing Industry. With English Summary]. Yhteiskuntatieteiden Tutkimuslaitos, Sarja T 17. Tampere: Tampereen yliopisto. [Google Scholar]

- Hökkä, Päivi, Susanna Paloniemi, Katja Vähäsantanen, Sanna Herranen, Mari Manninen, and Anneli Eteläpelto, eds. 2014. Ammatillisen toimijuuden ja työssäoppimisen vahvistaminen—Luovia voimavaroja työhön! [Promoting Occupational Agency and Learning at Work—Creative Resources for Work!]. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, Available online: https://jyx.jyu.fi/handle/123456789/44975 (accessed on 19 December 2018).

- Kalliola, Satu. 2003. Self-Designed Teams in Improving Public Sector Performance and Quality of Working Life. Public Performance & Management Review 27: 110–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kalliola, Satu, and Risto Nakari. 1999. Resources for Renewal. A Participatory Approach to the Modernization of Municipal Organizations in Finland. Dialogues on Work and Innovation DOWI 10. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Kalliola, Satu, and Risto Nakari. 2006. Vuorovaikutus ja dialogi oppimisen tiloina [Interaction and dialogue as learning spaces]. In Rajan ylitykset työssä. Yhteistoiminnan ja oppimisen uudet mahdollisuudet. Edited by Hanna Toiviainen and Hannu Hänninen. Jyväskylä: PS kustannus, pp. 203–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kalliola, Satu, and Risto Nakari. 2008. Dialogues with an Impact on Development. In Dialogue in Working Life Research and Development in Finland. Labour, Education and Society 13. Edited by Jarmo Lehtonen and Satu Kalliola. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, pp. 109–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kasvio, Antti. 1990. Työorganisaatioiden tutkimus ja niiden tutkiva kehittäminen [Researching and developing work organizations. Literature review.]. Yhteiskuntatieteiden tutkimuslaitos, Sarja T 4. Tampere: Tampereen yliopisto. [Google Scholar]

- Kasvio, Antti, Risto Nakari, Satu Kalliola, Arja Kuula, Ilkka Pesonen, Helena Rajakaltio, and Sirpa Syvänen. 1994. Uudistumisen voimavarat. Tutkimus kunnallisen palvelutuotannon tuloksellisuuden ja työelämän laadun kehittämisestä. [Resources for Renewal. Researching Productivity and the Quality of Working Life of Municipal Services]. Yhteiskuntatieteiden tutkimuslaitos, Sarja T 14. Tampere: Tampereen yliopisto. [Google Scholar]

- Kazi, Mansoor. 2014. Realist Evaluation and Effectiveness Research: An Example from School Based Interventions. In Evaluation as a Tool for Research, Learning, and Making Things Better. Edited by Satu Kalliola. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kivimäki, Riikka. 2011. Työhyvinvointi on Tehtävä. Terveydenhoitoalan Työpaikat Työhyvinvointia Kehittämässä [Health Care Work Organizations in Promoting Wellbeing at Work]. Työelämän Tutkimuskeskus, Työraportteja 87. Tampere: Tampereen yliopisto, Available online: https://tampub.uta.fi/handle/10024/65669 (accessed on 19 December 2018).

- Kivimäki, Riikka, Aija Karttunen, Leena Yrjänheikki, and Sari Hintikka. 2006. Hyvinvointia sairaalatyöhön. Terveydenhuollon kehittämishanke 2004–2006. [Improving workplace welfare in hospital work. Development project in the health care sector 2004–2006]. Sosiaali- ja terveysministeriön selvityksiä 69. Helsinki: Sosiaali- ja terveysministeriö, Available online: http://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/71950/Selv200669.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2018).

- Kivimäki, Riikka, Eija Kyrönlahti, Anita Keski-Hirvi, Kaija Loppela, Niina Peltoniemi, and Pia-Maria Haapala. 2015. Yhteistyöllä Uusia Työhyvinvoinnin Edistämisen Malleja UUMA [New Cooperation Based Models for Promoting Wellbeing at Work]. Seinäjoki: Epky, Available online: http://huispaus.ucs.fi/Epanet/Arkisto/julkaisuja/uuma_mallit.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2018).

- Lämsä, Tuija. 2010. Leadership Styles and Decision-Making in Finnish and Swedish Organizations. Review of International Comparative Management 1: 139–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lawler, Edward E. E., III. 1987. High-Involvement Management Participative Strategies for Improving Organizational Performance. San Francisco: Jossey Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Leinonen, Minna. 2016. Toimintatutkimus ja työkonferenssimenetelmä työpaikkojen tasa-arvon edistämisessä [Action Research and He Work Conference Method in Promoting Workplace Gender Equity]. Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 2184. Tampere: Tampere University Press, Available online: http://tampub.uta.fi/handle/10024/99605 (accessed on 19 December 2018).

- Lewin, Kurt. 1948. Action Research and Minority Problems. In Resolving Social Conflicts. Selected Papers on Group Dynamics. Edited by Gertrud Weiss Lewin. New York: Harper & Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, Kurt. 1958. Group Decision and Social Change. In Readings in Social Psychology, 3rd ed. Edited by Eleanor E. Maccoby, Theodore M. Newcomb and Eugene L. Hartley. New York: Henry Holt and Company, pp. 197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Manzano, Ana. 2016. The Craft of Interviewing in Realist Evaluation. Evaluation 22: 342–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumby, Dennis K. 1988. Communication and Power in Organizations: Discourse, Ideology, and Nomination. Norwood: Ablex. [Google Scholar]

- Odhnoff, Jan, and Casten von Otter, eds. 1987. Arbetets rationaliteter: Om framtidens arbetsliv [The Rationalities of Work: About the Working Life of the Future]. Stockholm: Arbetslivscentrum. [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahoney, Joe, and Steve Vincent. 2014. Critical Realism as an Empirical Project A Beginner’s Guide. In Studying Organizations Using Critical Realism. Edited by Paul K. Edwards, Joe O’Mahoney and Steve Vincent. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pålshaugen, Øyvind. 1999. The End of Organization Theory? Language as a Tool in Action Research and Organizational Development. Dialogues on Work and Innovation DOWI 5. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson, Ray, and Nick Tilley. 1997. Realistic Evaluation. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Pollitt, Cristopher. 2003. Public Management Reform: Reliable Knowledge and International Experience. OECD Journal of Budgeting 3: 121–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W. Richard. 1995. Institutions and Organizations. Thousands Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Herrera, José Carlos, Jane Springett, and Carolyn Kagan. 2009. Critical Connectionss between Participatory Evaluation, Organizational Learning and Intentional Change in Pluralistic Organizations. Evaluation 15: 321–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, Lennart G. 2005. Professional Occupations and Status: A Sociological Study of Professional Occupations, Status, and Trust. Paper presented at ESA European Sociological Association Conference, Research Network ‘Sociology of Professions’, Torun, Poland, September 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Syvänen, Sirpa, Kati Tikkamäki, Kaija Loppela, Sari Tappura, Antti Kasvio, and Timo Toikko. 2015. Dialoginen Johtaminen: Avain Tuloksellisuuteen, Työelämän Laatuun Ja Innovatiivisuuteen [Dialogical Leadership: The Key to Productivity, Quality of Working Life and Innovativeness]. Tampere: Tampere University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, Richard E., and Robert B. McKersie. 1965. Behavioral Theory of Labor Negotiations: An Analysis of Social Interaction System. New York: McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Westhorp, Gill, Kaye Stevens, and Patricia J. Rogers. 2016. Using Realist Action Research for Service Redesign. Evaluation 22: 361–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).