Abstract

Glasgow has a persistent and historical gang culture. Dimensions of ‘the gang’ are widely recognized in terms of behavior, formation, membership, and territoriality. The gap in our knowledge lies in the nature of a gang’s evolutionary flexibility. Given that life-course criminology foregrounds continuity and change in offending, it is surprising that this evolution has gone unrecognized in Scotland. Many contemporary studies of youth gangs connect ‘gang talk’ exclusively with territoriality and masculinity overlooking criminal progression. The argument of this article does not dispute the dominant received conceptualization of the youth urban street gang. The article’s contribution is to progress beyond these narrowing tropes and chronological age boundaries to encompass a more complex portrayal of Glasgow gangs and the lives of the indigenous Scottish young lads who were interviewed. The article does this by voicing the lived experiences of those whose lives are enmeshed with gang membership and whose linguistic register rarely achieves a serious platform in the middle-class world in control of the British media.

1. Introduction

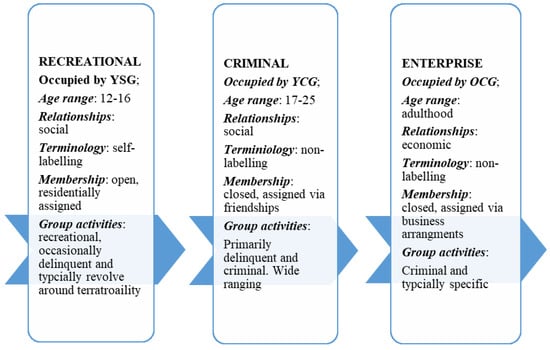

This article explores youth gangs in Glasgow, examining both the activities in which they partake in, and the evolving capabilities they may retain. Prior to the article being written, the authors input the phrase “violence in Glasgow” as a search term into a major UK research-led university library. This term yielded 68,849 hits—these included health and medicine, epidemiology and community health, feminist reviews, and studies published in contemporary British history journals. Our focus belongs with a very extensive context that addresses the multidimensionality of violence in relation to living in Glasgow. Our article seeks to address this violence in Glasgow through the lens of youth gangs. This is done by: (a) firstly, providing an in-depth analysis of youth gangs in the given context; and (b) exploring how gangs are by no means synchronic entities but rather retain evolving capabilities towards more serious forms of criminality. Figure 1 (below) points to the gangs’ capacity to evolve. Yet exploring the gang beyond a single stage is beyond this paper alone, thus the focus here is solely on the youth gang and how the gang may aid potential gang organization for some.

Figure 1.

The gang as an evolving phenomenon.

Figure 1 denotes change in criminal seriousness and their positional threat to society. Not unlike holding a university degree gang membership is a positional good, but one that helps to set conditions for a life involving legal incarceration, not enlightenment. This original theorization proposes that at this stage the youth gangs tend to be the coming together of various peer groups of similar age who all live within close proximity to one another: usually within a single housing estate or ‘scheme’ as it is labelled in Scotland (Deuchar 2009). These various groups regularly drift in and out of affiliation with a smaller body of persistent offenders seen to be the core body of the larger gang structure (Aldridge et al. 2005; Davies 2013; Deuchar et al. 2015; McLean 2017a; Patrick 1973; Violence Reduction Unit 2011). Our treatment of the gang bears comparison with the literature on life-course criminology where biographical trajectories are mapped. While most gang members at the recreational stage tend drift in an out of offending as adolescents before ‘ageing out’ altogether with maturity (See Matza 1964). For a minority, this is not the case, and instead delinquency gradually becomes criminality (Farrington et al. 1998, 2001). Moffitt’s (1993) dual taxonomy model likewise suggest that while offending spikes during adolescence, for the majority this is only temporary and will decline as individuals move towards adulthood. Before providing empirical support for the article’s thesis we turn to an analysis of the literature to legitimate our perspective. The evolution process relies upon the persistence of cultural myths about the developmental pathway of the male and the naturalness of a misogynistic gendered hierarchy. The ‘evolving gang’ (See Densley 2013) is intertwined with the growth of masculinity and received social hierarchy. Glasgow lads are rebels, but only to a point. It is mistaken to assert they advance enlightened societal structures of power.

2. Background

Characterizing street violence through the trope of “post code wars” simplifies the nuanced nature of violence against the person. We know from the ethnographies of Elijah Anderson (1999) in the US and Holligan (2014) in Scotland that a ‘code of the street’ connected with honor, natural justice, and reputation are precious forms of capital that, if threatened, can result in recourse to serious violence to determine natural justice (Anderson 1999). Gangs and gang culture in and around Glasgow city have continued their disturbing presence in terms of stabbings and other forms of antisocial behavior, with motor-bike and car theft being common. Localized gangs are far from being eradicated; in many of the poorer communities domiciled in Glasgow’s extensive conurbations gangs remain a very prevalent and unchanging feature of their working-class mental as well as physical cartographies. The intense political gaze which youths grouping together in such communities had to bear only a few years ago has steadily been relieved mainly due to the seeming reductions in knife carrying and inter/intra gang related violence1 (Deuchar 2013). Yet, while interpersonal violence appears remains down overall, a recent spike in knife crimes has rekindled a fearful outlook, local populations in Glasgow fear gang violence may re-emerge (Collins 2017).

In view of the presence of male youth gangs in Glasgow for more than a century, gangs appear entrenched. The persistence of intergenerational disadvantage reflecting a post-industrial collapse of employment is associated with the continuation of the historical trajectory of the youth gang. This is because overnight deindustrialization has meant that the ability for working-class male adolescents to express their masculinity via the workplace is no longer possible. Rather the expression of masculinity is now confined to the sphere of leisure. As a consequence, the gang has become an established outlet for hegemonic masculine expression (Connell 1995), whereby peer status and reputation is achieved through delinquent and occasionally criminal behavior, even if ‘toxic’ to future legitimate opportunities (Kupers 2005). For males, doing crime is, in many ways, seen as doing masculinity (See Messerschmidt 1993). This expression of this ‘protest’ masculinity (see Connell and Messerschmidt 2005) has in many ways become tied up with issues of territoriality whereby territory becomes a defended space (Holligan and Deuchar 2009). Therefore, this parallel coupling of the micro with the macro suggests gang membership offers those affiliated youths an opportunity to satisfy social and emotional needs that remain under threat due to the existence of pervasive poverty afflicting their neighborhood life (Vigil 1988a, 1988b).

Yet while gangs and street violence remain definitional of Glasgow’s ‘hard man’ identity and history, how these gangs ‘live’ is not entirely understood (Fraser 2015). The existing ‘gang talk’ seeming scholarly constructions of the gang to have emerged, following the turn of the century, have come from influential non-gang experts; public intellectuals opine through the mass media as well as members of an elite political establishment (Hallsworth and Young 2008). And, while such ‘talk’ generates academic action in the Anglo-Welsh context, the revisiting of the British gang in Scotland has not been met with the same level of enthusiasm (McLean 2017a), —or received serious research although qualitative contributions do exist to this literature (McLean 2018)2. Our cumulative knowledge of the gang in Scotland continues to grow, but we are nevertheless comparatively stifled in the understanding of the Scottish gang and existing gang typologies3.

Therefore, the purpose of the article is not to specifically critique existing literature, discuss other gang typologies, nor explain why the gang per se has been overlooked in the Scottish context when compared to our Anglo-Welsh counterparts, but rather the article aims to move beyond existing literature by providing a new qualitative analysis of Young Street Gangs (YSGs) in Scotland’s ‘gangland capital’, Glasgow using fresh primary data (Bartie 2010; Davies 1998, 2013). The article will do so by extending the meaning of territoriality and masculinity in their existing theoretical sense, and by listening to the youth voices of those having been involved in extensive YSG behavior. Our purpose means we present to the reader those lived realities of life in the YSG in a grass roots sense. In doing so, the authors hope to convey what it means to be a YSG member in Glasgow. Yet before presenting the voices of YSG and former YSG members, a contextual background about Glasgow gangs and gang culture is first described. Following this context-setting, the research methods are presented, the data analysis, and the results.

3. Gang Dynamics

Traditionally gangs in Britain had been considered distinct from those found in North America (Thrasher 1927). While US gangs were categorized as organized and inherently violent with links to serious criminality e.g., illicit drug trafficking, in Britain the gang were primarily youth groups who expressed rebellion through dress sense, style, and dabbling in drugs rather than outright criminality (Campbell and Muncer 1989). However, in the decades preceding the millennium, some reckoned that US-style street gangs were being imported into the UK (Bennett and Holloway 2004; Deuchar 2009). As a generalized anxiety, it was seen to be connected with predominantly global flows of cultural, economic, social, and political capitals (Pitts 2008). British scholars revisited the contemporary UK gang notion to establish whether or not there were grounds for comparisons between US and British gangs. The fruits of this comparative work has emerged over the past 30 years (Densley 2012, pp. 43–44). Glasgow, with its violent sectarian and later territorial gangs, should have easily been a candidate for this comparative enquiry and arguably be in its vanguard, but it was overlooked. This has not been the case. Scotland’s ‘welfarist’ approach to youth criminal justice (Deuchar and Sapouna 2016) has resulted in Glasgow’s comparative neglect by the criminologists. Recent research focused upon territoriality, masculinity, and street socialization with some even arguing against the existence of youth gangs in Glasgow (Fraser 2013; Lawson 2013; Miller 2015). The abstracted nature of these foci upon the gang phenomenon has interfered with gaining a nuanced appreciation of the lives of individuals for whom being in a gang matters as a lived always mutating reality.4

Given the historical relationship that Glasgow shares with gangs and gang culture, it is perhaps no surprise to find that much of the literature on Scottish gangs more generally revolves around studies carried out in and around the city of Glasgow.5 Yet despite the early razor gangs, with the exception of Sillitoe (1956), analysis of early gang formation in Glasgow has primarily been confined to the latter writings of a few scholars, namely Bartie (2010) and Davies’s (1998, 2013) historical analysis. Bartie (2010) details the process whereby gang narratives came to dominate public concerns over what may in fact have been the situation on the streets. Reviewing media articles from the post-war period, Bartie painstakingly explores how heightened fears of ‘the gang’ are essentially tied to the media’s biased reporting, and how that framed a gang-politicized discourse. During this ‘moral panic’, youth groups are misleadingly presented to the wider public as organized, violent, and necessarily criminal. Davies’s (2013) different approach anchors into historical reference points, including police and media articles, (auto)biographies, and court proceedings, to present the lived realities of early 20th century gang members as documented in historical sources. Davies (1998) utilizes Sir Percy Sillitoe’s 1956 biography ‘Clock and Dagger’ identify gang structure, behavior, and their supposed criminal activity. Davies argues the early gangs in the city typically comprised of an ‘inner core’ of ‘career criminals’, and an ‘outer circle’ of individuals on the periphery of the gang who would act like a fighting entourage when rival scuffles erupted over turf and sectarianism, but whose attachment to the gang over time varied.

Following WW2, gangs in Glasgow crystallized into other formations: Bartie (2010) points out gangs of post-war Glasgow contrasted with interwar forms identified by Davies (1998, 2013). Fundamental changes within Glasgow’s gangs occurred for a variety of reasons, including an upsurge in the economy, the inner-war years, and improvements in both security and living standards, amongst other factors (McLean 2017a). It was not until James Patrick’s (1973) covert ethnographic study of a Maryhill gang did social scientific interest in the Glasgow gang emerge. For Patrick the gang was effectively a group of youths whom could be divided into two units: a core and loose associates on the fringes of the gang, a finding echoing Davies (1998), but without the attribute of an essentialist criminally violent animus. These ‘Patrick gangs’ were younger and less structured with teenage delinquency expressing their identity. Aside from delinquent behavior, this gang provided members with recreational opportunities and support. Rebellion and masculinity through conflicts with other groups of youths from out with the housing estate exhausted most of their energy. Humphries (1981) supported this depiction of the gang in interviews with young gang members based in several British cities including Glasgow.

A shadow of silence enveloped research into the gang universe in Scotland until a handful of academics revisited the contemporary gang in Scotland. While Glasgow was again the primary location of investigation some scholars extended this investigation into Edinburgh. From the early 2000s there has emerged a fresh literature. Studies by the likes of Deuchar (2009, 2013), Fraser (2013, 2015), Holligan (2013), Lawson (2013), Miller (2015), and the action research conducted by Glasgow police’s Violence Reduction Unit, or VRU (2011) all suggest Glasgow gangs, and in the case of Bradshaw (2005), McAra and McVie (2007, 2010) Edinburgh gangs, contributed significantly to new knowledge of the youth gang in Scotland. A common conclusion of this body of work is that gangs in Scotland are recreational youth groups located in working-class neighborhoods whose social capital is problematic. These groups are formed as young teenagers socialize with one another in areas of public space within their housing estate, meet at school and support football teams. Occasionally these groups engage in territorial violence with groups of a similar makeup from nearby housing estates and their members may individually commit more serious offences. Territoriality is presented as being fixed and fighting associated is classified as serving proposes of status recognition and flight from lifestyles judged boring by those participating. However, McLean (2017a) critiques much of this body of work and claims that Scottish gang research is in many ways incomparable with gang literature in the Anglo-Welsh context. This is because Scottish gang research has studied, and labelled as gangs, what are essentially found to be peer groups in the Anglo-Welsh context (McLean 2018).

Yet McLean (McLean 2017a, 2018) argues this corpus of research is nonetheless limited in that it overlooks how some members of gangs, as they age, cause a change to occur in the nature of the gang to which they continue to associate. We argue in this article that the gang’s traditional representation in this more recent literature in the Scottish context varies from those found elsewhere in the UK, Europe, and the US. The collective scholarly error has been to fixate on a dominant paradigm of the gang where it is assumed the gang lacks a developmental trajectory. To help complete this lacuna in our knowledge of the gang the article (McLean 2017a, 2017b) proposes an outline of an evolving gang in terms of its having a continuum of growth from YSGs to Serious Organised Crime Gangs (SOCGs) (Figure 1). Furthermore, McLean argues that the gang type studied and described by those scholars mentioned directly above is essentially the YSG: the gang in its comparatively benign recreational stage of development. The research methodology was developed in order to facilitate an answer to the conjecture that the gang contains a developmental dimension and it not restricted to the provision of recreational violence and escapism for youths experiencing marginalization in the urban streets.

4. Research Methodology

The data presented was gathered between 2013 and 2016.6 This field work formed part of larger qualitative study into gang organization as a means to undertake gang business in Scotland. As mentioned, Glasgow has a historically embedded gang culture (Deuchar 2009, 2013; Miller 2015). Glasgow retains approximately 70% of Scotland’s organized crime; 65% of organized crime is related to the illegal supply of narcotics (Scottish Government 2009, 2015). Glasgow, our research site, was a fruitful location. The sample selection criteria were: (a) have been involved in gang-based group offending; (b) been involved in Serious and Organized Crime (Scottish Government 2009, 2015) and (c) be over 16 years of age. To access participants who met these criteria, street workers attached to key outreach projects in the West of Scotland’s acted as gatekeepers. The gatekeepers were asked to assist the researchers in accessing potential participants. This approach yielded a sample of 12 but was considered to be limited in accessing ‘hard-to-reach populations’. This duly prompted recourse to a snowball sampling technique whereby interviewed participant were asked to provide potential interviewees who met the set criteria (See Bhopal and Deuchar 2016).

In addition to interviewing the five gatekeepers and the 12 offenders so far, the snowball sampling technique provided successful and resulted in a further 25 interviews. In-depth life history interviews lasting about one hour were conducted with the participants. In regard to the participants who met the set criteria, all considered themselves to be indigenous Scots, although not all were white. These participants had been raised in households located mainly within working-class neighborhoods. These neighborhoods where situated within the Glasgow conurbation (Scottish Government 2012).

Although most interviews were conducted on a one-on-one basis, two focus group interviews were held. These group interviews numbered four and five participants respectfully. Whenever feasible gathered data would be triangulated, usually with those outreach workers but on occasion with other interviewees. The data was recorded with an audio device, before being analyzed thematically (Creswell 1998). Ethical approval was granted by the researcher’s university, and prior to interviews, an information sheet outlining relevant information was distributed as a tool for gaining informed consent. The extracts presented below typify interviewees’ constructions regarding gang formation, structure and activity in the YSG stage of development and outlined what factors were seen as contributing to gang organization and continuation along criminal trajectories.

5. Results

The results inducted from qualitative analysis are represented thematically. The overarching themes consist of four areas: ‘YSGs and Territoriality’, ‘YSG Structure and Gang Membership’, ‘Masculinity’, and ‘Gang Fights and Criminal Aspects’. A narrative structure is employed to convey these themes that arose from a process of inductive qualitative analysis below. As our study is qualitative, we do not claim the extracts are statistically representative, but they are typical of our data set which illuminates the phenomena that the article has as its research object.

6. Themes

6.1. Youth Street Gangs as Territorial

Existing research on YSGs revolves around territoriality (Kintrea et al. 2008). YSGs are emerge from historical conditions including a socioeconomic environment that places constraints on personal agency (Davies 2013; Fraser 2015). YSGs are prominent in the urban communities that suffer acute intergenerational deprivation (Deuchar 2009). These outlying urban areas of Glasgow and other Scottish cities including Edinburgh, Dundee, and Aberdeen lack age-appropriate recreational facilities as they experienced permanent post-Thatcher austerity cuts or ‘schemes’.7 Many of these marginalized youths are from families where older males including parents are situated within processes of intergenerational post-code entrenched incarceration. Grant, a research participant, convey his ‘life world’ of searching and negative restraint:

‘There wasn’t much to get up to when [growing up]. Nothing to do but get into trouble I suppose. Most of the daft gang fights I was involved in was more to do way breaking boredom than anything else.’—Grant

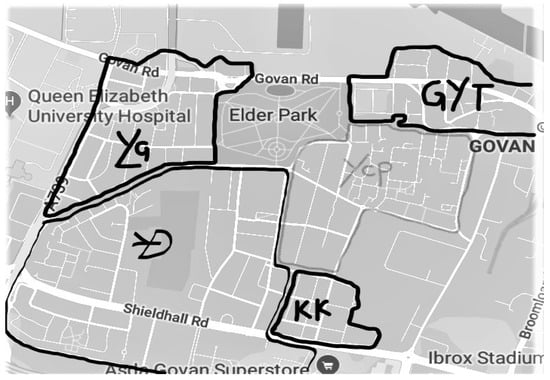

His reference to boredom symbolizes the alienation or anomie we associate with Emile Durkheim’s analysis of modernity. ‘Daft gang fights’ denote the construction under pressure of alternate social worlds. Fraser (2013, 2015) details how in post-industrial cities like Glasgow, communities have gradually become more isolated from one another, and disconnected from wider society. When placed over existing community divisions, as identified by Davies (2013), it is clear to see that pre-existing invisible boundaries that are intergenerationally transmitted are reinforced (Deuchar 2009). This process has resulted in the Glasgow conurbation essentially being divided in terms of identities and physical geography into numerous schemes. Their invisible boundaries are conveyed semiotically by graffiti, street corner shops, and public parks or railways lines. This material symbolism serves to not only hem youths into ‘ghettos’ marking what Hallsworth and Brotherton (2011) refer to as the ‘other’ a stereotype and imposed estrangement.8 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Aided by participants: Authors hand draw map of YSG scheme boundaries in the larger Govan housing estate.9

Research participants collaborated in the map making and its validation. The imposed marks in Figure 2 denote perception of scheme boundaries.10 Urban boundaries, as they perceive them, gridlock youths movement by limiting their social space and pessimistic mental scripts (See Kintrea et al. 2008). Even socializing on the boundary peripheries is interpreted by opposing YSGs as aggression and signal of anticipated incursion by enemies. As we argued earlier this territoriality has been presented as fixed or static, lived reality conveys a different picture.11 YSG boundaries are fluid, and permeable, Graeme argues:

‘The scheme I grew up in didn’t have one gang [but two]. We used to all fight but then all started hanging out together till one of the guys from the Krew [YSG A] got jumped by the Young Team [YSG B]. After that we all started fighting again…. was good no having to worry about getting jumped in your own [scheme]…. while it lasted. But too many dodgy (dangerously unpredictable) cunts pure thinking their [hard men] and always starting [conflict].’

Graeme’s claims that YSGs do merge within schemes, but the merger is never stable. Fighting others outside the scheme meant they were protected from rival gangs who belong to the same scheme. Rab observes it is not that two gangs (teams) from one scheme merge, but rather two YSGs from very different schemes located in other geographical areas may merge for strategic reasons at times:

We see in this extract the gang organizing its form to accommodation various environments in reaction to perceived threat. The gang evolves within areas that are outside their core geographic place of domicile. YSGs ‘operate’ as occasion demands by annexing a scheme’s name, yet the members comprise individuals from elsewhere outside of the scheme and normally identify with the gang of that scheme where they live. Rehousing polices can influence this social flux whereby residents are relocated to other neighboring schemes, yet youths continue to congregate in their original scheme, or where the local scheme once stood physically. James explains:‘Our [YSG] would team up with the boys from Gangja (YSG from Seedhill) and fight the Cumbie (Gorbals based YSG) outside the dancing. Probably did that most weekends for while back…. Never had any problems way the [Ganja] boys. Only met them at the dancing. Didn’t know them from like hang about, they came from the other side of [Glasgow]. They were sound but. [They] could get a meaty squad (numbers) together, and always came to [the town center] with a lot of [gang members]. So, did we…. Helped a lot [be] cause the Gorbals could always pull a heavy team on the Saturday’s.’

As demonstrated by James, the scheme he grew up in had long been demolished and no physical territorial boundaries remained. The youths who congregated in that location where they lived continued to adopt the scheme name to signify to others the social space they felt mattered to them. Gang names do not invariably indicate either where lads live or where there is inhabitable housing. This practice suggests the associative meaning of the name itself has taken on a resonance of its own which rallies the affiliated lads.‘There was no Tuch (former name of a demolished scheme) anymore. Last of the flats on [street X] got pulled down a years back. Me and the boys that use to live there got moved all over Glasgow by the council…. [but] we still always met back up on the weekends at the shops (which remained) …. Still called ourselves Kimbo Kill Boys.’

6.2. Youth Street Gang Structure and Membership

Drawing upon the work of Vigil’s (1988a) study of Latino youths in the US Barrios, Miller (2015) adopts a similar approach to ‘street socialization’ in Glasgow arguing YSG membership is not tainted because it is naturalized, and a given in communities. Intergenerational narratives construct the sociology of the scheme so strongly that the agency of the youth is undermined. They will identify with their locality as a territory and adopt scheme identity as a badge of who they are in conformity with the demand of the status quo.

As Dillan suggests, a YSG may be separated into two distinct bodies, of core and associate members. Studies by Davies (1998), Miller (2015), Patrick (1973), and Sillitoe (1956) as well as autobiographical accounts of criminal autobiographies (Boyle 1977; Ferris 2005; Ferris and McKay 2001, 2010; Jeffery 2003) describe Glasgow’s YSGs as typically consisting of both a criminal core and a wider grouping whereby smaller peer groups regularly attach themselves to the core body as an anchor of support and belonging. McLean (2017a) coins the former the ‘core body’ and the latter the ‘outer layer’. The key difference between core members and those of the outer layer predominantly lies in the way the groupings define their identity and crime. The core body itself is typically numerically modest, number around three to eight individuals at most, for them being criminally agentive is central to their sense of identity. As embryonic ‘career criminals’ they are more ‘ready’ to be receptive to membership of organized crime communities. Their criminality is imputed by them to forces over which their control is minimal (Boyle 1977). While reminiscing on his days as a core YSG member in Glasgow’s south side, Boab outlined how YSGs work:‘I didn’t want to, like, join a [YSG]… it just happens, know. You are just [as YSG member] because you [are raised] in [a] scheme. People from elsewhere say “that [Dillan] from [Scheme A]”. You don’t really have a choice … people just label you [as] where you’re [raised] … some boys, but, get right into it, aye. It is kind of who they are… [they] are like the [core of the] gang, basically aye. Most the troops mighty fight sometimes, but really just hang about wi’ them (the core) … [be]cause that, people, mostly the police and shit, think they are the gang as well.’—Dillan

We could muster a squad of about 40–45 bodies depending [on occasion] or who [we] were fighting. If it was local teams, then usually 20 or that but more people would come if say a [YSG] had been arranging to come through from the other end of the city for a fight…. most times I would just hang about way my [closest friends]. There was usually eight of us really (including Boab’s two siblings) …. it is unreasonable to play football way 40 boys, or get them all in your mum’s house to play the PlayStation at once (laughs).

His social life in the street resonates masculinity, references being made to technology, football and the female who provides within the domestic sphere, “your mum’s house”. Gender resonances of power surface in this militaristic discourse where “a squad”, “muster”, and “fighting” present opposing armies on the ground. While Boab refers to a large core body, and even larger outer layer12, this difference in numbers could be due to Boab having come from a particular housing estate, when compared to most. Leisure in the street seems masculinized, but in the home whilst that continues it becomes more intimate in “your mum’s house” where references to fathers are invariably absent. Research participants generally suggested that the average YSG size was between 20–30 individuals when gang fights occurred from which it could be concluded not that this represents violent escalation, but it is safer to be in the larger group whose entertain characteristics might also be more compelling. In this way such conflict is ritualistic and symbolic. Yet like the Govan housing estate, other large housing estates like Castlemilk, Drumchapel, and Easterhouse could not support a single YSG. Their streets and corridors were broken up and divided into a multitude of smaller areas to accommodate the formation of several YSGs. For example, the district Greater Pollok has several YSGs including ‘Arden’, ‘Bushwhackers’, ‘Darnley’, ‘Nitshill’, ‘Pollok Krew’, ‘Scratchy’ (AKA ‘South Nitshill’), ‘Bundy13, ‘Tiny Priesty’, and ‘Young Team’. Likewise, the district of Govan is no different with the likes of ‘Crossy Possie’, ‘Drumoyne Team’, ‘Goucho’, ‘Govan Team’, ‘Ibrox Tongs’, ‘Kimbo Kill’, ‘KP Derry’, ‘KP Star’, and ‘Young Young Winny’ (Evening Times 200614).

Despite media portrayals of YSGs consisting of a substantial number of youths regularly involved in gang violence, more often than not it is a ritualistic group activity revolving around socialising (Leask 2008; Mceachran 2003). Yet all smaller groups within a community are often referred to by locals, police, and peers as being the local gang therefore it was possible for the ‘gang’ to be in several locations and participating in several activities at once. In this way onlookers help in the construction of the mythology of the street gang, an attribution that may serve to satisfy other policing and community needs. However, by categorizing the whole of a smaller group as an extension of the gang, even those who are not gang members are labelled members (Deuchar 2009; Hallsworth and Young 2008). Others identify gang labelling as serving to solidify group cohesion (Hallsworth and Young 2006; Klein 1971). Hendo expounds on how his non-gang friends adopted the YSG label after having it had been continually applied to them by the police:

‘I might have fought for my [YSG]. So, did a few of my [other] pals, but I also hung about with a few boys that didn’t [fight for the local YSG]. No all my mates are [YSG] members, know what I mean…. When you’re getting called a gang all the time [by law enforcement and the local community], you just end up acting like [a gang] anyways don’t you.’

Hendo indicates that the labelling process saw him and his friends—both gang and non-gang members—increase their group cohesiveness. Similarly, Hendo also states that those members started to ‘act like’ a YSG, suggesting that they also engaged in territorial conflicts. Miller (2015) notes that street socialization often results in non-gang youths at times adopting gang-like behavior.15 Several participants discussed how YSGs only truly existed in relation to the occasion. While a core body remained fairly constant, the larger gang formation would generally only materialize at weekends, particular social events, parties, or arranged battles with other rival outfits.

6.3. Masculinity and Violence Capital

The gang evolution is also an evolution in terms of an entrenchment about masculinity and progression through the ladder of gender hierarchy. A ‘successful’ adult criminal sits at the pinnacle of this working-class informed pecking-order. Gang evolution has the backdrop the overlap of a trajectory of masculine identity growth. Fraser (2013) suggests while territorial confinement is perceived to have a negative impact upon Glasgow youth. On the other hand positive consequences occur in that creating confined social space enables individuals to gain local celebrity recognition. Territorial confinement allows participants to be ‘big fish in a small pond’. Phil and Wayne claim:

‘Fighting gave me a rep[utation] in my own scheme…. Like people my age would recognize me cause of gang fights they had heard I had been in.’

‘The police and all them, they don’t get it. Everyone is always pure saying “stop the violence” and “stop fighting, what you do that for”. They don’t get it but. It’s about being top boy, that’s all. Fuck all to do but scrap (fight)…. [Fighting] is the only fucking wi’ folk [around here] respect you…. If you can’t handle yourselves no one will respect you.’

As Phil points out, gang fighting enabled him to gain status within scheme boundaries. For Wayne, being able to fight well was perceived as a way to be recognized and respected amongst peers: Where else if this better displayed than in peer sight during YSG fights. Their idea of street capital interconnects with possessing a ‘successful’ reputation for violence (Harding 2014). Scotland’s martial tradition as a supplier of mercenary soldiers throughout history in Europe, for instance, during the Hundred Years War, and overseas in the New World including Canada is reflected in masculinity as fighting capacity. Masculine identity in the Glasgow context is bound with concepts of ‘maleness’ within working-class communities (Holligan and Deuchar 2015). Yet for marginalized youths now living in post-industrial Glasgow, such traits of maleness may become accentuated16, and even take on ‘hypermasculine’ or ‘protest masculinity’ value (Connell 1995). Such masculine expression is culturally specific (Tolson 1977). When placed in the YSG context in Scotland, masculinities invariably become ‘toxic’ (Kupers 2005). They are expressed through aggression, gym musculature, physical dominance, violence and esteem within the dominant gender hierarchy. Loe, a former criminal offender, argues:

‘Having a [penis] does not make you a man. Might make you look like one, but you earn manhood…. Guys are meant to be tough, know, you don’t act like a woman, irrational and shit. [In]stead you think things through, do what needs to be done. You protect your family…. when in school I would get into fights thinking it made me the big man. And it probably did in my mate’s eyes, but always somebody out there harder than you…. don’t learn that till it’s too late. Acting that way, being a man [through gang violence] seen me end up missing six months of my life [by being imprisoned]. I know now you can be a man…. without having to get into trouble, [but] you don’t think of that when you’re young.’

Leo seems to have “aged out” of his earlier identity as a younger man. His notion of masculinity marginalized and derides the female as a weak and despised other. His masculinity is misogynist. He overlooks how incarceration in these post-codes is a rite of passage to working-class masculinity. Leo recognized that as a marginalized youth living in an isolated and deprived community, those traits associated with tough working-class manhood are damaging (Kupers 2005). In Glasgow hyper-masculinity amongst youths is most clearly evident through territorial conflicts between YSGs, attributes like toughness and bravery subsequently become both heightened and distorted in their expression (Deuchar 2009; Holligan and Deuchar 2015; Kupers 2005; Miller 2015; Patrick 1973; Whitehead 2002). Jerry statement captures this point:

‘Suppose a just [perceive] fighting as what guys do …. if you’re a man, you’re going to get into fights ... I loved the excitement [YSG fighting] gave me, aye. You wi’ the boys (other YSG members) chasing [rival YSGs] …. Aye, you get some buzz mate…. Daft, but you feel like the big [man] after it.’—Jerry

Fighting well provides achievements at no financial cost. Whitehead (2002) suggests the cultural embedding of class dynamic helps aid a process whereby forms of street capital are seen as essential for attaining manhood. In a cultural and historical context, masculinity in Glasgow has historically been found to retain extraordinary aggressive and violent undercurrents (Holligan 2014). A seeming cultural acceptance of YSG violence expected from boys, is captured in the accounts of local youth workers. Shuggie and John controversially argue:

‘[Of] course [young males in Glasgow] get into trouble. What boy doesn’t [when] growing up. Boys fight. That’s what they do. Do you get me…. Boys will be boys won’t they…. [even] if my [own son] wasn’t getting into trouble I’d probably be worried to tell you the truth.’—Shuggie

‘I’ve a few boys of my own. To be honest mate I wouldn’t want them going off the rails or nothing. [I] do expect them to act up a bit during their teen [age years] at least…. every boy has at least one fight for the scheme. Doesn’t make them bad though.’—John

The statements by both youth workers demonstrate the feeling that boys will inevitability engage with YSGs at some point during their adolescent years. These participants acknowledged cultural practices exist in a Glasgow where YSG violence is natural. Fighting and being violent is seen as a feature of a developmental process. It is not pathologized. It is however theorized through the lens that colludes in the unwitting acceptance of gendered male stereotypes, for boys. Each worker does not connect their expectations about boys as perhaps a limited endorsement of the more enduring kinds of anti-social behaviors and their pathways into serious criminality. The gang as an evolving phenomenon is arguably sustained by a culture of complicity about beliefs about the naturalness of a supposed gendered human nature whose expressions are judged developmentally appropriate.

7. Gang Fights and Criminality

While participants were not always proud of the offences they committed during YSG fights, many felt their involvement in a YSG was a symbol of being a hegemonic male (Rafanell et al. 2017). YSGs are an important part of adolescent life in the scheme as they gave opportunities for masculine performance valued in the context. Gang fighting was a surrogate sporting event which for the working-class male meant the athleticism shown by middle-class counterparts in rugby or sky-diving could be easily displayed without the barrier of financial cost. These masculine traits for lads in the schemes were sources of esteem and recognition. In professional football, teams play in a national league where they compete against teams from within the region and league association. In order to determine the best team, they compete and sharpen their existing skills. Likewise, YSGs regularly ‘mix it up’ in fighting against rival YSGs from out with local jurisdiction. Gang fighting for the disenfranchised youth is available as a mechanism for expressing a class-based type of masculinity (Holligan 2013). When street fights occur some are particularly violent and foster weapon carrying, as Alan explains:

‘One time…. [YSG A] from the other side of the Clyde tunnel came through and started going to town (fighting) with us (YSG-B). [YSG-A] had been saying over [pirate radio station] they where coming through and going do this and that, course we got heavy tooled up and waited for them, man. Even (X and Z17) were carrying blades (knives) man…. After a heavy brawl on Govan road, two of our boys ended up jumping a taxi to the other side of the tunnel, [so] when we ended up chasing them, we basically cornered them off in the tunnel and a couple of their boys got done (severely injured, possibly stabbed)…. No kidding mate, was bodies scattered everywhere after that. Their bodies mind you, not ours (laughs)’.

His representation of a form of serious recreational violence involving youth largely aged 12–16 foregrounds an interest in portraying it as urban ritual. Hyperbolic comment aims to resonate the existence of a war zone adding weight to the attempt to annex courage to those participating especially those who succeed in remaining upright. Yet while YSGs sought to display and attain masculinity through conflict with other YSGs, inner YSG conflict was not uncommon. The YSG could be a place of inner conflicts and continual power struggles. Positions and status were constantly challenged by other members—usually through violence, threat, or verbal correction—as masculinity was having to be both proven and reproven (Holligan 2014). Such dynamics of insecurity suggest the fragile social capital circulating these street cultures. Participants believed internal division resulted in heightened levels of violence or group fractioning.

Beyond violence, YSGs did not exert much effort in carrying out planned crimes, or crimes for financial gain. Some YSGs, such as the Gorbals Cumbie and Suicide Cumbie had a reputation for knife-point robbery, but this was opportunistic an attempt to exert masculinity in front of peers. More deliberate criminal enterprise found that YSGs were most frequently involved in drug supply. However, dealing drugs by no means reflected what Coomber (2006) terms ‘drug-dealing proper’, but rather a ‘social supply’ to affiliates and others in the area. The reasons for initially engaging in ‘social supply’ ranged considerably, and often had little to do with securing a steady source of finance, as outlined by Fraz:

‘Most [of the] time we hung out was spent getting high. Use to meet up down the woods to take buckets (a method of consuming cannabis via the use of a plastic bottle) …. People would take turns in getting the [cannabis]. I use to get it [from my older brother], but they had to pay me back, know what I mean. I couldn’t be paying for it all the time. No pure rich or nothing man …. Or sometimes we would all chip in. I got it but so didn’t pay.’—(Fraz)

Fraz argued that a lot of the time youths spend in YSGs is spent socializing, may often include dappling with drug use. Fraz indicates that his role as social supplier meant he was exempt from paying for the drugs he would later consume in the group setting. Obtaining drugs for free seemed to motivate that role. Similarly, Fraz did not obtain drugs to sell on the open market, but rather he purchased them to share amongst friends and known associates. McPhee (2013) notes that often those who have been involved in social supply may gravitate towards more serious forms of supply. This process was also at work in Fraz’s case:

‘[Progressed] from there really, suppose. Was getting nine bars (a large weight of cannabis) quite a bit at the time from [my older brother]. He was giving me them. Well no giving me them. Had to pay, course, but was getting me them if I asked. On tick (credit) as well …... most my mates had left school and had jobs, so had money to get ounces, whatever, aye. I just sold them [cannabis] …. Wouldn’t say it was intentional, know, More, I could get it and they wanted it. I needed the money.’

A critical interpretation is that Fraz was in fact a dealer using the mask of a mere social supplier to establish markets and income. Fraz story epitomized the way most participants in the study began to sell drugs, but who often appeared unwilling to classify themselves as drug dealers which would criminalize and stigmatize them. Under cover of the street gang identity, they demonstrated signs of evolving into the more serious criminal enterprise. Initially participants had extensive friendship networks giving that they socialized in large peer groups and YSGs. Due to pre-existing contacts—usually in the form of criminal familial or close friends with criminal familial, all of whom were older and more experienced criminals—they were able to gain access to recognized drug markets. While supply in YSGs was primarily in the form of an apparent social supply, as participants aged and faced different threats coupled with an increasingly entrenched delinquent identity favoring law-violation, saw them use existing resources to engage in more criminal behavior. This tendency seemed systematic, but at the same time clandestine in terms of the accounts they gave about it and their mental scripts that helped neutralize them from blame. The enterprise stand of our Figure 1 emerges then on the basis of at least two phenomena: firstly a putative social drug dealing coincides with a drift into drug dealing more conventional gain, and secondly, the context includes more experienced criminals who offer combinations of role models and access to drug markets. Evolution is a messy social affair.

8. Conclusions

Our article makes its contribution by beginning to propose and evidence a holistic analysis of YSGs in Glasgow in the sense of their being variable and sites of opportunity for criminal progression. Much of the information we know, or assume to be true, about Glasgow gangs emanates either from ‘gang talkers’ or law enforcement. As a consequence, the YSG image that those of the general public are presented with is often this mythology of bravado that received discourses impose upon the talkers whose appear inclined to conform to their understanding of the expectations of an audience. Even the academic literature on the subject, often the lived realities of ‘gang life’ are homogenized. Territory is constructed formulaically, and mere masculinity is given as the catalyst for gang membership and the resulting youth violence. Yet this article proposes that territory is moral commitment to the self, peers, and historical attachments. Territoriality embraces many tangible and intangible properties. YSGs may forge alliances, reshape territories, create new ones, and drift into the embrace of more serious criminal propensities connected with money-making. YSG at first blush are primarily formed via street socialization. However, the social practices that street capital develops from may in certain cases project individuals into the beginnings of an adult criminal ‘career’. The ability to develop ones’ masculinity in the YSG, often via bravado and violence, enables such individuals to acquire a certain reputation which can be used to help gain access into the criminal underworld should they seek to progress along criminal trajectories. Although hegemony is by no means confined to an ones’ recourse to violence but in reality is the interplay between numerous factors (including race, sexuality, ethnicity, etc.), and this is something YSG members need to negotiate carefully if they are to progress successfully beyond YSG formation. Autobiographical sources of renowned underworld figures give support in favor of this trajectory as well as the attempts at neutralization by some of our research participants.

This is particularly true given that such groupings have been shown to generally have differing levels of membership, structure, and degrees of association with other groups. It is during this process that those who will go on to become persistent offenders forge alliances, make contacts, acquire a ‘bad’ or ‘feared’ reputation, learn how to fight and supply drugs, and acquire this identification. Many (auto)biographical accounts concerning Glasgow’s gangsters, for instance, Jimmy Boyle and Paul Ferris reflect back to their early years in which a fighting reputation was gained, networks developed and gang structure as a resource exploited for acquisitive crimes. Household names like Specky Boyd, Paul Ferris, and Tam McGraw, trace their origins back to in YSGs. Therefore, it is crucial to understand how YSGs and criminality later in life are intertwined. A circulation of role models of renowned local persons who develop into more public criminals is likely be an unfortunate resource that impacts the aspirations of some teenage males in tandem with their admiration for football celebrities. Neither is likely to offer them a positive or realistic future.

Author Contributions

Writing-Literature Review, C.H.; Methodology, R.M.; Findings, R.M.; Conclusion, C.H.; Revision and Proofread, R.M.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank James Densley, School of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice, Metropolitan State University, for his comments and advice.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aldridge, Judith, Robert Ralphs, and Juanjo Medina-Ariza. 2005. Street youth gangs in an English city: Social exclusion, drugs and violence. In Eurogang VIII Workshop ‘The Social Contexts of Gangs and Troublesome Youth Groups in Multi-Ethnic Europe. Onati: International Institute for the Sociology of Law. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Elijah. 1999. Code of the Street: Decency, Violence and the Moral Life of the Inner City. New York: W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Bartie, Angela. 2010. Moral panics and Glasgow gangs: Exploring the new wave of Glasgow hooliganism, 1965–1970. Contemporary British History 24: 385–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Trevor, and Katy Holloway. 2004. Gang membership, drugs and crime in the UK. British Journal of Criminology 44: 305–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhopal, Kalwant, and Ross Deuchar. 2016. Researching Marginalized Groups. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, Jimmy. 1977. A Sense of Freedom. London: Pan Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, Paul. 2005. Terrors and young teams: Youth gangs and delinquency in Edinburgh. In European Street Gangs and Troublesome Youth Group. Edited by Scott H. Decker and Frank M. Weerman. Oxford: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Anne, and Steven Muncer. 1989. Them and us: A comparison of the cultural context of American gangs and British subcultures. Deviant Behavior 10: 271–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Robert. 2017. Knife crime in Scotland soars by TEN PER CENT in a year… as victims campaigner says offenders treated too leniently. The Scottish Sun, January 4. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, Robert William. 1995. Masculinities, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, Robert W., and James W. Messerschmidt. 2005. Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender and Society 19: 829–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomber, Ross. 2006. Pusher Myths: Re-situating the Drug Dealer. London: Free Association Books. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John. 1998. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Andrew. 1998. Street gangs, crime and policing in Glasgow during the 1930s: The case of the Beehive Boys. Social History 23: 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Andrew. 2013. City of Gangs: Glasgow and the Rise of the British Gangster. London: Hodder & Stoughton. [Google Scholar]

- Densley, James A. 2012. The organization of London’s street gangs. Global Crime 13: 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Densley, James A. 2013. How Gangs Work: An Ethnography of Youth Violence. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Deuchar, Ross. 2009. Gangs, Marginalised Youth and Social Capital. Stoke on Trent: Trentham Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Deuchar, Ross. 2013. Policing Youth Violence: Transatlantic Connections. London: Institute of Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deuchar, Ross, and Maria Sapouna. 2016. ‘It’s harder to go to court yourself because you don’t really know what to expect’: Reducing the negative effects of court exposure on young people—Findings from an Evaluation in Scotland. Youth Justice 16: 130–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuchar, Ross, Johanne Miller, and Mark Barrow. 2015. Breaking down barriers with the usual suspects: Findings from a research-informed intervention with police, young people and residents in the West of Scotland. Youth Justice 15: 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evening Times. 2006. Glasgow Gang Map. Evening Times, February 6. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington, David P., Sandra Lambert, and Donald J. West. 1998. Criminal careers of two generations of family members in the Cambridge study in delinquent development. Studies on Crime and Crime Prevention 7: 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington, David, Darrick Joliffe, Rolf Loeber, Magda Stouthamer-Loeber, and Larry Kalb. 2001. The concentration of offenders in families and family criminality in the prediction of boy’s delinquency. Journal of Adolescence 24: 579–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, Paul. 2005. Vendetta: Turning Your Back on Crime Can Be Deadly. Edinburgh: Black and White Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ferris, Paul, and Reg McKay. 2001. The Ferris Conspiracy. Edinburgh: Mainstream. [Google Scholar]

- Ferris, Paul, and Reg McKay. 2010. Villains: It Takes One to Know One. Edinburgh: Black and White Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, Alistair. 2013. Street habitus: Gangs, territorialism and social change in Glasgow. Journal of Youth Studies 16: 970–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, Alistair. 2015. Urban Legends: Gang Identity in the Post-Industrial City. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth, Simon, and David Brotherton. 2011. Urban Disorder and Gangs: A Critique and a Warning. London: Runnymede. [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth, Simon, and Tara Young. 2006. Urban Collectives: Gangs and Other Groups. Report for Operation Cruise. London: HM Government/Metropolitan Police. [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth, Simon, and Tara Young. 2008. Gang talk & gang talkers: A critique. Crime, Media & Culture 4: 175–95. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Simon. 2014. The Street Casino: Survival in the Violent Street Gang. Bristol: The Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holligan, Chris. 2013. ‘The cake and custard is good!’ A qualitative study of teenage children’s’ experience of being in prison. Children and Society 29: 366–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holligan, Chris. 2014. Breaking the code of the street: Extending Elijah Anderson’s encryption of violent street governance to retaliation in Scotland. Journal of Youth Studies 18: 634–48. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13676261.2014.992312 (accessed on 12 May 2015). [CrossRef]

- Holligan, Christopher Peter, and Ross Deuchar. 2009. Territorialities in Scotland: Perceptions of young people in Scotland. Journal of Youth Studies 12: 727–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holligan, Chris, and Ross Deuchar. 2015. What does it mean to be a man? Psychosocial undercurrents in the voices of incarcerated (violent) Scottish teenage offenders. Criminology and Criminal Justice 15: 361–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, Stephen. 1981. Hooligans or Rebels: Oral History of Working Class Childhood and Youth, 1889–1939. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery, Robert. 2003. Glasgow’s Godfather: The Astonishing inside Story of Walter Norval, the City’s First Crime Boss. Edinburgh: Black and White Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Ronnie, and Arthur McIvor. 2004. Dangerous work, hard men and broken bodies: Masculinity in the Clydeside heavy industries: 1930–1970s. Labour History Review 69: 135–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintrea, Keith, Jon Bannister, Jon Pickering, Maggie Reid, and Naofumi Suzuki. 2008. Young People and Territoriality in British Cities. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Malcolm W. 1971. Street Gangs and Street Workers. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Kupers, Terry A. 2005. Toxic masculinity as a barrier to mental health treatment in prisons. Journal of Clinical Psychology 61: 713–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, Robert. 2013. The construction of ‘tough’ masculinity: Negotiation, alignment and rejection. Gender and Language 7: 369–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, David. 2008. Three Hundred Booze and Blade gangs Blighting Scotland. The Herald. March 4. Available online: https://www.pressreader.com/uk/the-herald/20080304/281517926821436 (accessed on 9 November 2015).

- Matza, David. 1964. Delinquency and Drift. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- McAra, Lesley, and Susan McVie. 2007. Youth justice? The impact of system contact on patterns of desistance from offending. European Journal of Criminology 4: 315–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAra, Lesley, and Susan McVie. 2010. Youth crime and justice: Key messages from the Edinburgh study of youth transitions and crime. Criminology and Criminal Justice 10: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mceachran, John. 2003. The Murder City—Glasgow is the Western European Killing Capital. The Daily Record. November 27. Available online: https://clippednews.wordpress.com/2003/11/28/glasgow-murder-capital-of-europe/ (accessed on 30 November 2015).

- McLean, Robert. 2017a. An Evolving Gang Model in Contemporary Scotland. Deviant Behavior 39: 309–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, Robert. 2017b. Glasgow’s Evolving Urban Landscape and Gang Formation. Deviant Behavior. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, Robert. 2018. How Gang Narratives Stifle Gang Research. In Gang Violence: Perspectives, Influences and Gender Differences. Edited by Cliff Akiyama. Hauppauge: Nova Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- McPhee, Iain. 2013. The Intentionally Unseen: Illicit & Illegal Drug Use in Scotland. Saarbrucken: Lambert Academic Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Messerschmidt, James W. 1993. Masculinities and Crime: Critique and Reconceptualization of Theory. Totowa: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Johanne. 2015. In Every Scheme There Is a Team: A Grounded Theory of How Young People Grow in and out of Gangs in Glasgow. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University West of Scotland, Hamilton, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt, Terrie E. 1993. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review 100: 674–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, James. 1973. A Glasgow Gang Observed. London: Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Pitts, John. 2008. Reluctant Gangsters: The Changing Shape of Youth Crime. London: Willan Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rafanell, Irene, Robert McLean, and Lynne Poole. 2017. Emotions and hyper-masculine subjectivities: The role of affective sanctioning in Glasgow Gangs. NORMA International Journal for Masculinity Studies 12: 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Government. 2009. Letting Our Communities Flourish: A Strategy for Tackling Serious Organised Crime in Scotland; Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Scottish Government. 2012. Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation; Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Scottish Government. 2015. Scotland Serious Organised Crime Strategy Report; Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Sillitoe, Percy. 1956. Cloak without Dagger. London: Pan. [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher, Frederic Milton. 1927. The Gang: A Study of 1313 Gangs in Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tolson, Andrew. 1977. The Limits of Masculinity. London: Tavistock. [Google Scholar]

- Vigil, James Diego. 1988a. Group processes and street identity: Adolescent Chicano gang members. Ethos 16: 421–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigil, James Diego. 1988b. Barrio Gangs: Street Life and Identity in Southern California. Austin: University Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Violence Reduction Unit. 2011. The Violence Must Stop: Glasgow’s Community Initiative to Reduce Violence. Second Year Report. Glasgow: VRU. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, Stephen M. 2002. Men and Masculinities: Key Themes and New Directions. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Knife culture has often been an assumed trait of gang activity in Glasgow, and thus consequently has been used as a way to measure gang proliferation. Yet, the perception that declines in knife violence automatically means a decline in gang formation is naive. |

| 2 | For a discussion on those reasons why the revisiting of the British gang has been disproportionately Anglo-centric see McLean (2017a, 2018). |

| 3 | McLean (2017a, 2017b) argues that Scotland’s academic community has explicitly focused on one form of gang typology in Scotland—Young Street Gangs—and in the process of doing so have effectively overlooked the possibility that other typologies may exist. McLean terms these other typologies as ‘Young Crime Gangs’ and ‘Serious Organized Crime Groups’. Note though, that although the latter is derived from Police Scotland’s organized crime terminology, the actual criteria required differs significantly according to McLean. |

| 4 | For example, territoriality is often assumed as inherently fixed, yet as we shall discuss in the findings this is not really the case, many youths congregate from various housing estates, and band together under one unified term (often in relation to the social space they occupy in for socialization, as opposed to residential, purposes). |

| 5 | Given Glasgow’s historical relationship with gangs, and prevalent gang culture, the city serves as an ideal reference point for studying gangs in the wider Scottish context. Likewise, given the geographical proximity (much of Scotland’s population is disproportionately located across the central belt), similarities in socioeconomic circumstances and history of heavy industry employment, it can be assumed that life in Glasgow is reflective of much of those other cities, towns, and burghs in Scotland. Yet, it is important to note, that differences between YSGs of Scotland’s West Coast and Central Belt may vary slightly with those located in the Highlands, for example, therefore it is for this reasons that the study is a comprehensive analysis of YSGs in Glasgow as opposed to being a comprehensive study of YSGs in Scotland. It would be unfair to assume life in Glasgow reflects life in all of Scotland, if not much of it. |

| 6 | Note that several additional interviewees took place after 2016, yet the data from the additional interviews were not included in McLean’s original unpublished thesis ‘Discovering Young Crime Gangs in Glasgow: Gang Organization as a Means for Gang Business’, due to time constraints to submit the thesis. |

| 7 | In Glasgow, Dundee, and Aberdeen as well as in Edinburgh housing estates are usually referred to as ‘schemes’. Schemes generally follow those boundary lines which the city council defines as separating one housing estate from another, yet such lines are not a given, and are by no means fixed, as will be detailed later. The welfare state that provides this housing for typically unemployed populations in the case of Glasgow is the largest in Europe in terms of level of benefit dependency. |

| 8 | Note, that references of the ‘other’ tend to emphasise aspects that visibly distinguish outsiders such as skin color, cultural dress style, etc., In Glasgow’s YSGs, the ‘other’ is the outsider from outside of the scheme. Often schemes are particularly small and as such the youths living within them know of, or recognize most, of those who are of a similar age group. Thus when youths from elsewhere enter the scheme, they can be identified immediately as not belonging to that area. |

| 9 | From top left clockwise: YLG is Young Linty Goucho; GYT is Govan Young Team; YCP is Young Crosse Posse: KK is Kimbo Kill; YDT is Young Drumoyne Team. Source of map is Google Street Maps. |

| 10 | Please note while scheme boundaries are generally YSG boundaries, this is not always the case, and neither do gangs from these areas necessarily always carry the same name. |

| 11 | How territoriality actually presents itself is largely hidden, or at times overlooked, in contemporary gang research in Scotland. While academics tend to demonstrate territoriality as existing as a theoretical concept with invisible boundaries, law enforcement may focus on particular areas of public space where youths from a local scheme congregate (See Fraser 2013; Violence Reduction Unit 2011). |

| 12 | Most YSGs core body tended to be closer to numbering between 3–5 individuals, and the outer layer between 20–30. |

| 13 | The Bundy no longer exists as it has since been demolished. It once stood where Silverbrun shopping center is situated. Although obtaining a notorious reputation, it was relatively small in size when compared to surrounding territories and consisted of a block of post-war three story tenements, a block of two story flats, and several four-in-a-block cottage homes. |

| 14 | Note, while the source given also identifies ‘Tuecharhill Young Team’, this is another name for the ‘Kimbo Kill’. |

| 15 | It was also found that gang photos placed on social media, typically consisted of core YSG members and nonmembers alike, who for the purpose of the photograph alone adopt gang-like behavior, status, and insignia. |

| 16 | Despite a considerable proportion of the sample having found themselves suffering from second- or even third-generational unemployment, manual types of work were nonetheless deemed crucial assets in being able to self-legitimize one’s manliness (Johnston and McIvor 2004). However, the desire to express masculinity through work-related activities has become somewhat hindered and constrained, due to globalized processes which have resulted in Glasgow’s deindustrialization. Thus, being young and lacking legitimate outlets for masculine expression, participants spoke of channelling masculinity through aggressive recreational outlets, of which YSG formation may be one. |

| 17 | X and Z are non-gang members who often associated with these particular YSG but rarely got involved in YSG fights. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).