Abstract

War, famine, political conflicts and environmental factors (e.g., climate change) have increased the flow of immigrants into several European countries. Immigrants’ integration represents one of the most important challenges to our globalized society. Previous research has pointed out that social-dominant people show negative reactions towards immigrants. The present research is aimed at expanding and consolidating previous knowledge about immigrants’ research by proposing that: (i) citizens’ happiness is related to a favorable attitude towards immigrants; and (ii) social dominance orientation is related to attitude towards immigrants through happiness. In this study, a large sample recruited across different European countries (European Social Survey 2014 data, N = 40,185) has been considered. Measures of social dominance orientation, happiness and attitude towards immigrants have been assessed. Results showed that people’s happiness is related to favorable attitudes towards immigrants. Moreover, these results also showed the mediating role of happiness in the relationship between social dominance and attitude towards immigrants. Implications for future studies and policy strategies to support immigrants’ integration are discussed.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, famine, war, political conflicts and environmental factors in critical areas of the world have increased the flow of immigrants into different European countries. In addition, the attractiveness engendered from the economic prosperity and the relative political stability of some European countries has raised this flow of immigration. Thus, in 2016, 4.1% (20.1 million) of the European population was composed of minority groups of immigrants (EUROSTAT 2017). Likely, immigrants’ integration represents one of the most important challenges to our globalized society in the contemporary age. Immigration and integration policies need to be developed in order to prevent intergroup conflicts. Indeed, the future of EU society is strongly related to the adaptation and integration of immigrants and their children. This cultural transition’s process has been widely recognized as a social sciences process that encompasses different fields such as social psychology, sociology and economics as well as politics. One of the aims of this study consists of investigating some social-psychological factors that could play a key role in the understanding of the phenomenon related to attitude towards immigrants.

A relevant factor that has been traditionally related to discrimination, prejudice and stereotyping of minority groups is the social dominance theory (SDT; Pratto et al. 1994; Pratto et al. 2006; Sidanius and Pratto 2001; Sidanius et al. 1994b). Such a theory posits that individuals showing higher levels of social dominance orientation (SDO) also report a highly stratified and hierarchical vision of society. In other words, social-dominant people support the idea that intergroup and interpersonal relationships should be highly hierarchical, while individuals showing lower levels of SDO approve and support equality-based intergroup relationships. Social-dominant people preferring group-based hierarchies emphasize antagonism, inequality, and the supremacy of some groups viewed as dominant over those dominated. Based on these assumptions, previous research has shown that social dominance is related to several outcomes such as prejudice, discrimination, negative reactions to people belonging to a low-status group, and support for warfare, as well as cruel initiatives (e.g., Pratto et al. 1994; Sidanius et al. 1994a; Sidanius and Pratto 2001). Sidanius and colleagues have pointed out that a crux in the SDT is the competitive vision of the world characterized by lack of empathy, scant concern for other individuals, and unwillingness to identify with them (e.g., Pratto et al. 1994; Sidanius et al. 2013; Sidanius et al. 1994b). Thus, one could suppose that social-dominant people tend to view the world as a dog-eat-dog environment (Pratto et al. 2006).

Let me now turn to the relationship between SDO and the negative attitude towards immigrants. Some authors have highlighted a relationship between SDO and negative reactions to immigrants (e.g., Costello and Hodson 2010, 2011; Guimond et al. 2010; Thomsen et al. 2008). In particular, Thomsen et al. (2008) postulated the “status boundary enforcement hypothesis” claiming that: “SDO should be associated with aggression against immigrants who do assimilate into the dominant culture because this blurs existing status boundaries between groups” (p. 1455). More specifically, it would seem that SDO is more strongly associated with negative reactions towards immigrants when they are eager to assimilate into the dominant culture. By contrast, a social-dominant disposition would seem more weakly related to negative reactions towards immigrants that prefer the cultural isolation. In a subsequent study, Guimond and colleagues corroborated this link between SDO and negative attitude towards immigrants (Guimond et al. 2010). In this vein, Costello and Hodson (2010, 2011) showed that higher levels of SDO are related to greater resistance to help immigrants needing assistance and prejudice towards immigrants, as well as their (de)humanization. Even though previous literature has empirically established a link between SDO and negative attitude towards immigrants (e.g., Guimond et al. 2010; Costello and Hodson 2010, 2011; Thomsen et al. 2008), little is known about potential factors that could play a relevant role in this relationship. The main aim of this study consists of shedding light on potential underlying factors in the association between SDO and negative attitude towards immigrants. There is evidence that citizens’ happiness could play a relevant role in fostering equality and that it is associated with important social indicators (Flavin and Radcliff 2009; Flavin et al. 2011; Oishi et al. 2018; Radcliff and Shufeldt 2016).

Happiness has been considered to be one of the most relevant outcomes of human life (Diener et al. 2015). It could be considered one of the main sources of wellbeing (e.g., Diener and Biswas-Diener 2002). Indeed, several studies have pointed out that individuals’ happiness is related to several achievements in life such as marriage, a comfortable income, career success, a long life, life satisfaction, reduced job stress, and good mental health (e.g., Diener et al. 2017; Mastekaasa 1994; Diener and Biswas-Diener 2002; Naseem 2018; Clark et al. 2018; Jebb et al. 2018; Walsh et al. 2018). With respect to the aim of this study, several authors have shown an association between happiness and different prosocial behavior outcomes such as volunteering, charity donations, and helping others (e.g., Aknin et al. 2018; Appau and Churchill 2018; Dunn et al. 2008; Post 2005; Thoits and Hewitt 2001). Diener and colleagues have also pointed out that happiness may increase the likelihood to perform adaptive social behaviors. Indeed, people’s happiness would seem to increase sociality, mating and creativity (Diener et al. 2015). A recent study has shown that happiness derives from career success, and vice versa, it can also lead to improved outcomes in the workplace, thus pointing out that the hypothesis which claims that happiness could be an antecedent of such outcomes is plausible (Walsh et al. 2018). Based on these studies, happiness would seem to represent a relevant factor contributing to prosocial behavior; and accordingly to the evolution of the society (e.g., Aknin et al. 2018; Appau and Churchill 2018; Diener et al. 2015; Thoits and Hewitt 2001; Walsh et al. 2018). In this vein, Oishi and colleagues (2018) have recently provided compelling empirical evidence demonstrating that people’s happiness is strongly related to income inequality. In particular, it would seem that income inequality would make people less happy. Indeed, despite individuals’ negative attitude towards taxation, it would seem that people are happier when paying taxes which, in turn, are aimed at reducing economic inequality (Oishi et al. 2018). Oishi et al. (2018) attribute this effect to a specific phenomenon, a so-called “tax morale: feeling that one is a good citizen by paying taxes” (p. 9). Accordingly, this link between happiness and willingness to reduce social inequality is directly opposed to the link between SDO and willingness to conserve the status quo as well as differences among groups. To the best of my knowledge, there is no empirical evidence showing that happiness could influence attitude towards immigrants. Thus, empirical research that takes these factors into account could help us to explain some mechanisms underlying the well-established relationship between social dominance and negative reaction towards immigrants.

From a different line of research, compelling evidence has shown that people with a liberal ideology are happier than conservatives (i.e., a political ideology strongly related to SDO) (e.g., Wojcik et al. 2015). Pollock and colleagues have also pointed out a positive relationship between happiness and personality traits related to a liberal ideology, such as extraversion or openness to experience (Pollock et al. 2016). Such a link has been supported in different studies (e.g., Diener and Seligman 2002; Lauriola and Iani 2017; Tkach and Lyubomirsky 2006). Thus, in the present research using a very large sample, it has been supposed that social dominance orientation (an individual disposition related to a conservative ideology) might be negatively associated with happiness. The idea behind this supposition is that conservative attitudes, such as social dominance, might have a function aimed at maintaining the status quo, which is hard to maintain in a world as globalized as our world. Globalization boosts rapid changes and transformations and, accordingly, it might be frustrating to see that every effort to maintain the status quo falls apart. For example, the conservative political parties’ attempts to prevent immigrants from entering European countries often fail because it is impossible to prevent such migrations towards these countries. Thus, social-dominant people could be less happy to live in a society that does not reflect their need to maintain the status quo or in which they see a threat to the hierarchical order of society. Previous empirical research would not seem to highlight happiness as a resource that could play a relevant role in the relationship between social dominance and negative reaction towards immigrants. Thus, the main aim of the present study consists of shedding light on whether and how people’s social dominance could be related to attitude towards immigrants through happiness.

The Present Study

Previous social psychology research has demonstrated that social dominance negatively affects attitude towards immigrants because social-dominant people would tend to conserve the status quo and perceive immigrants as a threat to it (e.g., Costello and Hodson 2010, 2011; Guimond et al. 2010; Thomsen et al. 2008). More specifically, the status boundary enforcement hypothesis pointed out that people’s social dominance is related to negative reactions towards immigrants when they show willingness to assimilate into the dominant culture. It is likely that, in a social-dominant view, such an effect could be explained by the perception of the threat that immigrants could go beyond the borders of the group to which they belong (Thomsen et al. 2008). On the other hand, recent compelling evidence has shown that happiness can be related to a willingness to reduce economic inequality (i.e., a vision of society related to low social dominance) and liberal ideologies (e.g., Oishi et al. 2018; Wojcik et al. 2015). Thus, drawing on previous studies, this research is aimed at testing the following hypotheses: First, it is predicted that individuals showing higher levels of happiness would also show a positive attitude towards immigrants compared to individuals with lower levels of happiness. Second, it is predicted that SDO is related to happiness, which in turn, is related to attitude towards immigrants. Specifically, it has been hypothesized that greater SDO is related to negative attitude towards immigrants through a lower level of happiness. Finally, it is also expected to replicate and corroborate the link between SDO and attitude towards immigrants using the European Social Survey (ESS) data that make it possible to robustly test this association by using a very large sample.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

In this research, data from the seventh round of the ESS (2014) have been analyzed. This round has been chosen as it focused specifically on measuring attitudes towards immigration. The ESS databases are freely available to researchers and comprise measures of attitude towards immigrants, demographics and personality dispositions. The ESS (2014) round 7 data provide empirically grounded composite indexes as an option to analyze immigration attitudes. The ESS is a data source enabling the investigation of the issues about the immigration attitudes that are some of the most often used in academic research. The population considered was composed of EU citizens over the age of 15. For each of the European countries, respondents were selected by means of strict probability samples of the resident populations. Participants were interviewed using face-to-face mode regarding different social issues including their attitudes towards immigration, social dominance and happiness (ESS 2014). The total sample was of 40,185 participants. Women made up 53% of the sample (Mage = 49.28; SD = 18.74). Due to some missing values, the valid sample for the mediation model described herein was 35,126.

An overview, more details, and a full description of the design of the survey (ESS) are reported at the following web link: http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Social Dominance Orientation

The key index of orientation to equality—SDO—has been measured through the following item: “Would you say that some cultures are much better than others or that all cultures are equal?” (reverse coded). Respondents rated the extent to which they agreed with this statement (1 = Some cultures are much better than others; 2 = All cultures are equal).

2.2.2. Happiness

The index of happiness has been assessed through the following item: “How happy would you say you are?” Respondents rated the extent to which they agreed with this statement, on an 11-point scale, with the responses anchored at the ends with 0 (extremely unhappy) and 10 (extremely happy).

2.2.3. Attitude towards Immigrants

Such an index has been assessed through 3 items: “Would you say it is generally bad or good for [country]’s economy that people come to live here from other countries?” Respondents indicated their agreement with this statement, by an 11-point scale, with the responses anchored at the ends (0 = Bad for the economy–10 = Good for the economy). The following two items were: “Would you say that [country]’s cultural life is generally undermined or enriched by people coming to live here from other countries?” (11-point scale response options: 0 = Cultural life undermined–10 = Cultural life enriched); “Is [country] made a worse or a better place to live by people coming to live here from other countries?” (11-point scale response options: 0 = Worse place to live–10 = Better place to live). This index has been calculated as the aggregated index by summing up all responses to all items in the index. Cronbach’s alpha of this sample was 0.85.

3. Results

To investigate the relationships between SDO, happiness and attitude towards immigrants, the zero-order correlations among these variables have been computed (see Table 1). The results of the present research showed that SDO was significantly negatively related to both happiness and attitude towards immigrants. Finally, individuals’ happiness was significantly and positively associated with a favorable attitude towards immigrants (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations and intercorrelations among variables investigated in the Study.

As expected, the association of happiness with attitude towards immigrants was supported by a multiple regression model where attitude towards immigrants score was regressed on participants’ happiness (β = 0.233, p < 0.001; Bunstandardized = 0.780, 95% CI = 0.747 to 0.813). In the model, age and gender (women coded as 1 and men coded as 2) were entered as covariates and they also showed a significant effect with men and the young showing a more positive attitude towards immigrants (gender β = 0.022, p < 0.001; Bunstandardized = 0.272, 95% CI = 0.148 to 0.396; age β = −0.064, p < 0.001; Bunstandardized = −0.022, 95% CI = −0.025 to -0.018).

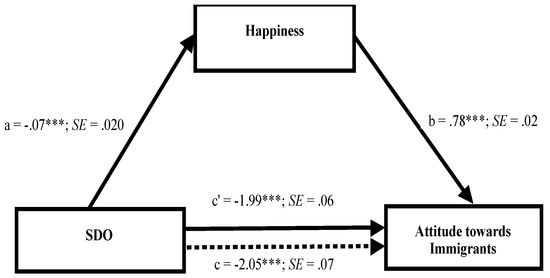

To understand the mechanisms underlying the relationships between SDO, happiness and attitude towards immigrants, the PROCESS macro for SPSS has been used (see Hayes 2013; for more details), which tested the mediation hypothesis (Hayes 2009; Preacher and Hayes 2008). Hayes and Scharkow (2013) have claimed that the bootstrapping procedure is the most trustworthy method of assessing the effects of mediation models. The mediation model included SDO as the independent variable, happiness as the mediator, and attitude towards immigrants as the dependent variable. Such a model was estimated to derive the total, direct and indirect associations of SDO with attitude towards immigrants through happiness. The model estimated the indirect effect of SDO on attitude towards immigrants, quantified as the product of the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression coefficient estimating happiness from SDO (path a in Figure 1) and the OLS regression coefficient estimating attitude towards immigrants from happiness, controlling for SDO (path b in Figure 1). A bias-corrected bootstrap-confidence interval (CI) for the product of these paths that does not include zero provides evidence of a significant indirect effect (see MacKinnon et al. 2000; Preacher and Hayes 2008; Hayes 2009, 2013; for more details). Using the PROCESS macro with 5000 bootstrap samples, the results of the present research revealed a significant negative indirect effect of SDO on attitude towards immigrants through happiness (point estimate = −0.057; 95% CI = −0.088 to −0.027).

Figure 1.

Path coefficients for mediation analysis in the Study. Note: Dotted line denotes the effect of social dominance orientation on attitudes towards immigrants, when happiness is not included as a mediator. a, b, c and c′ are unstandardized OLS regression coefficients. *** p < 0.001.

Since participants’ gender and age could be related to attitude towards immigrants, then a mediating model which included gender (women coded as 1 and men coded as 2) and age as covariates has been tested. The dependent, independent and mediator variables were the same as in the previous model (see Figure 1 for more details). The relationships between SDO, happiness and attitude towards immigrants did not substantially change after controlling for the effect of these covariates (point estimate = −0.05; 95% CI = −0.076 to −0.017). In line with previous results, the model showed a significant positive effect of gender on attitude towards immigrants (β = 0.029, p < 0.001; Bunstandardized = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.23 to 0.48), with men showing a more positive attitude towards immigrants. A significant negative effect of age on attitude towards immigrants has also been confirmed (β = −0.058, p < 0.001; Bunstandardized = −0.020, 95% CI = −0.023 to −0.016), with older people showing negative attitude towards immigrants.

4. Discussion

The present research was aimed to investigate two main purposes. First, this study has sought to establish a positive link between happiness and a favorable attitude towards immigrants. The second purpose of the present research was to point out whether social dominance was related to attitude towards immigrants through happiness. Finally, albeit in previous research, an association between SDO and negative attitude towards immigrants has already been established, a further aim of this study has been to corroborate this relationship through a very large sample (Costello and Hodson 2010, 2011; Guimond et al. 2010; Thomsen et al. 2008). Taken together, the results of the present research provide support for the hypotheses of the study. More specifically, it shows a positive link between people’s happiness and a favorable attitude towards immigrants. Such a link is relevant because according to Oishi and colleagues’ perspective, one might claim that happiness may represent a relevant resource to reduce inequality as well as promote a favorable attitude towards immigrants (Oishi et al. 2018). In particular, in the present study it has been seen that people’s happiness plays a relevant role in the relationship between SDO and negative reactions towards immigrants. In fact, the results of the present research firstly show that a negative link between SDO and attitude towards migrants could be explained from lower levels of citizens’ happiness. An overarching message of this study is that people who are higher in happiness show a more favorable attitude towards immigration and a more egalitarian stance in society. This represents a novel insight, as happiness can be a factor susceptible to public policies and interventions. Indeed, one could suppose that policy decision makers may counteract negative reactions towards immigration and populism related to this phenomenon, for example, by acting promptly on citizens’ happiness via policies aimed at fostering such a factor. For example, some public policies promoting unemployment protection and welfare benefits might enhance and support people’s happiness. Some authors argue that people are more satisfied when government actively intervenes in the market economy, for example, by modifying the outcome of it (e.g., Flavin and Radcliff 2009; Flavin et al. 2011; Radcliff and Shufeldt 2016). It would seem that government efforts in this direction would foster happiness across society at large, and not just in less-privileged people. Moreover, public intervention efforts to protect citizens from the instability of the market economy would seem to be associated with greater happiness (see Flavin et al. 2011; Radcliff and Shufeldt 2016; for more details). Thus, such a factor could represent a lever to promote different positive social outcomes such as greater equality, counteracting populism, as well as preventing negative reactions and prejudice towards immigrants.

From a different line of research, some authors have pointed out a significant relationship between mindfulness and happiness, as well as social dominance orientation (e.g., Brown and Kasser 2005; Hollis-Walker and Colosimo 2011; Jazaieri et al. 2014; Panno et al. 2018). In this vein, Lim et al. (2015) have shown that a mindfulness meditation training self-administered via smart technologies was effective in determining more compassionate behavior towards strangers (Lim et al. 2015). Keeping in mind that mindfulness is negatively related to SDO and positively to happiness (Brown and Kasser 2005; Hollis-Walker and Colosimo 2011; Jazaieri et al. 2014; Panno et al. 2018), one might expect that mindfulness training could be helpful to reduce negative reactions towards immigrants and the tendency to support the inequality expressed by social-dominant people. Thus, mindfulness training could be adopted with the purpose of coping with migration issues. This is encouraging in terms of the applied interventions of these results, even though future studies are needed to shed light on such a field. In this vein, some authors have also shown that an emotion regulation strategy that is strongly related to happiness (i.e., cognitive reappraisal; Gross and John 2003) can represent a helpful resource to cope with relevant social issues such as climate change and intractable conflicts (e.g., Israeli–Palestinian conflict; Gross et al. 2013; Halperin et al. 2013; Halperin 2014; Panno et al. 2015). Future studies could test whether well-established interventions aimed at the enhancement of such an emotion regulation strategy might also be effective in coping with the immigration issues (see Halperin et al. 2013; Halperin 2014; for more details).

Even though this research offers notable strengths, some limitations should be considered when drawing conclusions from it. First, although a very large sample has been used to shed light on the relationships between SDO, happiness and attitude towards immigrants, the mediating role of happiness needs to be supported by further empirical evidence. Thus, future longitudinal studies investigating causal mechanisms underlying these relationships are needed. Future studies should also seek to replicate such results in an experimental setting trying to manipulate happiness as well as using implicit measures to assess attitude towards immigrants. It is true that the cross-sectional nature of the studies does not allow causal inferences; nevertheless, the results of the present research provide relevant insights into the relationships between SDO, happiness and attitude towards immigration. Second, some studies have shown happiness to be related to some personality dispositions that could play a further role in these relationships (e.g., Pollock et al. 2016). It was beyond the scope of the current study to investigate all of these, but we cannot rule out that some of these might influence these relationships. Thus, future studies should take into account these factors when examining such relationships.

To summarize, this work extends previous research in the following ways: First, it shows a positive link between happiness and a favorable attitude towards immigrants. Second, the findings of this research shed light on the relationship between social dominance and negative reactions towards immigration showing that happiness plays a key role in it. Third, even though previous studies showed a link between social dominance orientation and attitude towards immigrants, these results add empirical evidence corroborating such a relationship through a very large sample (e.g., Costello and Hodson 2010, 2011; Guimond et al. 2010; Thomsen et al. 2008).

In conclusion, the present study advanced a model illustrating a relevant and broad potential mechanism underlying the association between SDO and attitude towards immigration. The results of the present research increase our knowledge about social dominance theory (e.g., Pratto et al. 1994; Pratto et al. 2006) and are also relevant for studies that rely on happiness to predict social outcomes (e.g., Aknin et al. 2018; Diener et al. 2015; Oishi et al. 2018; Radcliff and Shufeldt 2016). Broadly speaking, the results of this research can promise novel insight into these connections across various fields including social and positive psychology, as well as political science. More and more studies are needed to fill the gap among these disciplines, but the intersection between psychological and political science can represent a fruitful avenue to cope with relevant social issues peculiar to our time (e.g., climate change, migration, etc.). The present research is an attempt in this direction suggesting that a dominant view, whether it pertains to the strong or weak, does not fit well with a happiness stance. Such a misfit holds the potential to be a powerful tool to promote equality as well as reduce discrimination in society at large.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Aknin, Lara B., Julia W. Van de Vondervoort, and Kiley J. Hamlin. 2018. Positive feelings reward and promote prosocial behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology 20: 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appau, Samuelson, and Sefa A. Churchill. 2018. Charity, Volunteering Type and Subjective Wellbeing. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. Advance on line publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Kirk W., and Tim Kasser. 2005. Are psychological and ecological well-being compatible? The role of values, mindfulness, and lifestyle. Social Indicators Research 74: 349–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Andrew E., Sarah Flèche, Richard Layard, Nattavudh Powdthavee, and George Ward. 2018. The Origins of Happiness: The Science of Well-Being over the Life Course. Princeton: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, Kimberly, and Gordon Hodson. 2010. Exploring the roots of dehumanization: The role of animal—Human similarity in promoting immigrant humanization. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 13: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, Kimberly, and Gordon Hodson. 2011. Social dominance-based threat reactions to immigrants in need of assistance. European Journal of Social Psychology 41: 220–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, and Robert Biswas-Diener. 2002. Will money increase subjective well-being? Social Indicators Research 57: 119–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, and Martin E. Seligman. 2002. Very happy people. Psychological Science 13: 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, Ed, Satoshi Kanazawa, Eunkook M. Suh, and Shigehiro Oishi. 2015. Why people are in a generally good mood. Personality and Social Psychology Review 19: 235–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, Ed, Sarah D. Pressman, John Hunter, and Desiree Delgadillo-Chase. 2017. If, why, and when subjective well-being influences health, and future needed research. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 9: 133–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, Elizabeth W., Lara B. Aknin, and Michael I. Norton. 2008. Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science 319: 1687–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ESS. 2014. ESS7 - 2014 Data Download. Available online: http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/data/download.html?r=7 (accessed on 3 June 2018).

- EUROSTAT. 2017. Statistiche sulle migrazioni internazionali e sulle popolazioni di origine straniera. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics/it (accessed on 3 June 2018).

- Flavin, Patrick, and Benjamin Radcliff. 2009. Public policies and suicide rates in the American states. Social Indicators Research 90: 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavin, Patrick, Alexander C. Pacek, and Benjamin Radcliff. 2011. State Intervention and Subjective Well-Being in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Politics & Policy 39: 251–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, James J., and Oliver P. John. 2003. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85: 348–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, James J., Eran Halperin, and Roni Porat. 2013. Emotion regulation in intractable conflicts. Current Directions in Psychological Science 22: 423–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimond, Serge, Pierre De Oliveira, Rodolphe Kamiesjki, and Jim Sidanius. 2010. The trouble with assimilation: Social dominance and the emergence of hostility against immigrants. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 34: 642–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, Eran. 2014. Emotion, emotion regulation, and conflict resolution. Emotion Review 6: 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, Eran, Roni Porat, Maya Tamir, and James J. Gross. 2013. Can emotion regulation change political attitudes in intractable conflicts? From the laboratory to the field. Psychological Science 24: 106–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2009. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs 76: 408–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Andrew F., and Michael Scharkow. 2013. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychological Science 24: 1918–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollis-Walker, Laurie, and Kenneth Colosimo. 2011. Mindfulness, self-compassion, and happiness in non-meditators: A theoretical and empirical examination. Personality and Individual Differences 50: 222–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazaieri, Hooria, Kelly McGonigal, Thupten Jinpa, James R. Doty, James J. Gross, and Philippe R. Goldin. 2014. A randomized controlled trial of compassion cultivation training: Effects on mindfulness, affect, and emotion regulation. Motivation and Emotion 38: 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebb, Andrew T., Louis Tay, Ed Diener, and Shigehiro Oishi. 2018. Happiness, income satiation and turning points around the world. Nature Human Behaviour 2: 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauriola, Marco, and Luca Iani. 2017. Personality, positivity and happiness: A mediation analysis using a bifactor model. Journal of Happiness Studies 18: 1659–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Daniel, Paul Condon, and David DeSteno. 2015. Mindfulness and compassion: An examination of mechanism and scalability. PLoS ONE 10: e0118221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKinnon, David P., Jennifer L. Krull, and Chondra M. Lockwood. 2000. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science 1: 173–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastekaasa, Arne. 1994. Marital status, distress, and well-being: An international comparison. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 6: 183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Naseem, Khalida. 2018. Job Stress, Happiness and Life Satisfaction: The Moderating Role of Emotional Intelligence Empirical Study in Telecommunication Sector Pakistan. Journal of Social Science 4: 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi, Shigehiro, Kostadin Kushlev, and Ulrich Schimmack. 2018. Progressive taxation, income inequality, and happiness. American Psychologist 73: 157–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panno, Angelo, Giuseppe Carrus, Fridanna Maricchiolo, and Lucia Mannetti. 2015. Cognitive reappraisal and pro-environmental behavior: The role of global climate change perception. European Journal of Social Psychology 45: 858–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panno, Angelo, Mauro Giacomantonio, Giuseppe Carrus, Fridanna Maricchiolo, Sabine Pirchio, and Lucia Mannetti. 2017. Mindfulness, pro-environmental behavior, and belief in climate change: The mediating role of social dominance. Environment and Behavior. Advance on line publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, Noah C., Amy E. Noser, Christopher J. Holden, and Virgil Zeigler-Hill. 2016. Do orientations to happiness mediate the associations between personality traits and subjective well-being? Journal of Happiness Studies 17: 713–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, Stephen G. 2005. Altruism, happiness, and health: It’s good to be good. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 12: 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratto, Felicia, Jim Sidanius, Lisa M. Stallworth, and Bertram F. Malle. 1994. Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67: 741–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratto, Felicia, Jim Sidanius, and Shana Levin. 2006. Social dominance theory and the dynamics of intergroup relations: Taking stock and looking forward. European Review of Social Psychology 17: 271–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, Kristopher J., and Andrew F. Hayes. 2008. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods 40: 879–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radcliff, Benjamin, and Gregory Shufeldt. 2016. Direct democracy and subjective well-being: The initiative and life satisfaction in the American States. Social Indicators Research 128: 1405–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, Jim, and Felicia Pratto. 2001. Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius, Jim, Felicia Pratto, and Lawrence Bobo. 1994a. Social dominance orientation and the political psychology of gender: A case of invariance? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67: 998–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, Jim, Felicia Pratto, and Michael Mitchell. 1994b. In-group identification, social dominance orientation, and differential intergroup social allocation. The Journal of Social Psychology 134: 151–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, Jim, Nour Kteily, Jenniffer Sheehy-Skeffington, Arnold K. Ho, Chris Sibley, and Bart Duriez. 2013. You’re inferior and not worth our concern: The interface between empathy and social dominance orientation. Journal of Personality 81: 313–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoits, Peggy A., and Lyndi N. Hewitt. 2001. Volunteer work and well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 42: 115–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, Lotte, Eva G. Green, and Jim Sidanius. 2008. We will hunt them down: How social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism fuel ethnic persecution of immigrants in fundamentally different ways. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 44: 1455–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkach, Chris, and Sonya Lyubomirsky. 2006. How do people pursue happiness?: Relating personality, happiness-increasing strategies, and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies 7: 183–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Lisa C., Julia K. Boehm, and Sonya Lyubomirsky. 2018. Does Happiness Promote Career Success? Revisiting the Evidence. Journal of Career Assessment. Advance on line publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojcik, Sean P., Arpine Hovasapian, Jesse Graham, Matt Motyl, and Peter H. Ditto. 2015. Conservatives report, but liberals display, greater happiness. Science 347: 1243–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).