Abstract

Migration through Central America continues to rise, yet limited research examines how people make migration decisions, especially among those traveling in transit. This study addresses that gap by analyzing the motivations of migrants passing through Casa del Migrante San José in Ocotepeque, Honduras, to examine how long-term pressures interact with immediate triggers during migration. A mixed-methods approach was used, integrating two data sources: 3934 registration records from the Human Mobility Pastoral database (2021–2022) and 75 semi-structured interviews conducted in December 2022. The Push-Pull Plus (PPP) framework was applied to interpret how persistent conditions, immediate triggers, and available support networks influence decisions to migrate. Quantitative results show a marked increase in arrivals during 2022, especially among Venezuelan migrants, with a peak in October following a U.S. policy announcement. Most participants were men aged 21–40 with incomplete secondary education, and economic hardship was the most frequently cited reason for leaving. However, interviews indicate that financial motives were often intertwined with insecurity, family obligations, and unexpected opportunities to travel. Overall, the findings suggest that migration decisions are complex, dynamic, and timing-sensitive, underscoring the need for policies that address the root causes while providing support for migrants in transit.

1. Introduction

Migration refers to the movement of people across or within national borders, encompassing all population movements regardless of size, cause, or composition. This includes economic migrants, displaced people, and asylum seekers (IOM 2020). Migrants are those who leave their place of origin temporarily or permanently to settle in another community or country (IOM 2019). These movements are often motivated by the pursuit of employment, improved living conditions, family reunification, or political instability in the country of origin (Aruj 2008). Many individuals undertake irregular migration routes when they are unable to access legal pathways for entry or residence in destination countries (Canales Cerón et al. 2019).

As of 2020, an estimated 281 million people were living outside their country of birth, accounting for approximately 3.6 percent of the global population (McAuliffe and Triandafyllidou 2022). This growth does not occur in isolation, but rather reflects ongoing disruptions in labor markets, state capacity, and regional security, which collectively narrow domestic livelihood options. In Latin America, particularly Central America, migration has intensified since the 1980s, driven largely by poverty, inequality, and political violence (Cecchini and Martínez Pizarro 2023). These conditions push people toward mobility not only because of material need, but because long-term instability reduces the predictability required to plan a viable future at home. These migratory flows reflect more profound structural transformations rooted in the region’s historical experience with colonization, dependency, and uneven development (Apablaza Riquelme 2010). In practice, colonial histories produced unequal access to land, wages, and political voice, patterns that continue to shape livelihood opportunities in the region today (Hunter 2024; Frankema 2010). These inherited inequalities influence who can build a stable life locally and who becomes more vulnerable to displacement. When economic exclusion persists across generations, migration emerges not only as a response to current hardship but also as a long-term strategy for navigating structural constraints. From this perspective, contemporary mobility reflects both historical processes and present conditions rather than a temporary fluctuation in flows. Transit migration is therefore not simply movement between origin and destination, but a distinct condition shaped by uncertainty, institutional gaps, and rapid decision making (Brunarska and Ivlevs 2023; Zorlu and Van Gent 2023).

According to United Nations estimates, by 2015, there were approximately 31.1 million Latin American migrants living in the United States, representing about 5 percent of the total U.S. population (Canales Cerón et al. 2019). In many Latin American countries, repeated implementation of political and economic models that have deepened social inequality and excluded large sectors of the population from development opportunities has contributed to widespread social deterioration (Aruj 2008). Migration between Latin America and the United States is shaped by a complex interplay of political instability, economic exclusion, and social vulnerability, with both immediate and long-term consequences (Massey et al. 1993; Suárez 2008; Castles et al. 2014).

The number of Honduran migrants in the United States has increased dramatically, rising from 39,000 in 1980 to approximately 1.2 million by 2019, which represents a 3000 percent increase over four decades (Perdomo et al. 2020). Between 2018 and 2019, it was estimated that approximately 300 Hondurans migrated each day, while an average of 256 were deported daily, primarily from Mexico and the United States (Perdomo et al. 2020). Currently, one in every nine Hondurans lives abroad, and more than 40 percent of the population expresses a desire or intention to emigrate. This growing migratory trend reflects the interaction of long-term structural inequality with more immediate pressures, rather than a combination of isolated causes. Chronic unemployment, poverty, inequality, and limited institutional capacity constrain livelihood stability and narrow future opportunities, while corruption and political crises heighten uncertainty and reduce access to protection (Sosa 2021). Migration produces both challenges and opportunities. It can strain social systems and labor markets in origin and destination countries, but it also provides critical remittances that support families and contribute to local economies (Suárez 2008).

Migrants in transit often face serious risks and vulnerabilities that threaten their physical safety, health, and lives, particularly in contexts where policies for their protection are weak or absent (Canales Cerón et al. 2019). Given the evolving and complex nature of contemporary migration, research plays a critical role in uncovering patterns, motivations, and broader impacts. To be effective, such research must integrate demographic, educational, health, and economic dimensions to offer a more comprehensive understanding of migratory processes (Cecchini and Martínez Pizarro 2023; Galeano 2011). However, there is still limited research that centers on the lived experiences and decision-making processes of migrants in transit through Central America (Lamiño Jaramillo et al. 2022).

Migration has both positive and negative impacts on individuals and societies. On the one hand, it can lead to the loss of cultural identity and separation from loved ones due to distance or language barriers (Bhugra and Becker 2005). On the other hand, it often arises from structural conditions that hinder national development, such as poverty, unemployment, or weak institutions (Rodríguez Martínez 2000). Human mobility is not a new phenomenon. It has been shaped historically by demographic, economic, environmental, and sociopolitical forces, including war, colonization, and state formation (Zahra 2021).

While economic and political crises often act as catalysts for migration, social networks and family ties frequently enable and sustain migratory flows (Suárez 2008).

This study aims to fill critical research gaps by examining the perspectives of transit migrants at Casa del Migrante San José in Ocotepeque, Honduras, particularly regarding the motivations behind their decision to leave their countries of origin. Using a mixed-methods convergent approach, the research integrates quantitative and qualitative data to explore the primary drivers of emigration during 2021 and 2022. It focuses on identifying the social, economic, and political conditions that shape migration decisions, as well as the demographic characteristics of those on the move. This research is especially relevant as Honduras continues to experience high levels of emigration, which is part of a broader regional trend across Latin America, underscoring the need for informed policies and interventions that address root causes and support vulnerable populations (Lamiño Jaramillo et al. 2022).

Theoretical Framework

This study is grounded in the Push-Pull Plus (PPP) theory of migration, which expands on the classical push-pull model by offering a more nuanced understanding of how people make migration decisions. Initially developed by Ravenstein in the late nineteenth century and later refined by Lee (1966), the traditional push-pull framework primarily focuses on economic differences between the origin and destination. While this model has provided a helpful starting point, it has been widely criticized for being overly simplistic and economistic in nature. The PPP framework addresses these limitations by integrating a broader set of drivers and dimensions that better reflect the complexity of migration processes (Van Hear 1998; Van Hear et al. 2018).

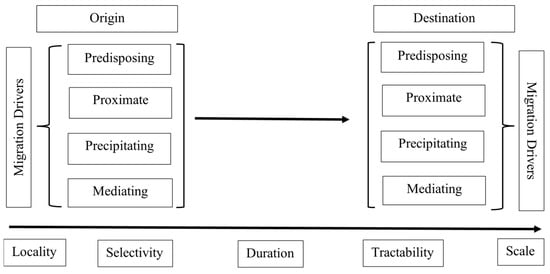

The structure of these functional drivers and dimensions is visually represented in Figure 1, which illustrates the relationships between predisposing, proximate, precipitating, and mediating factors, as well as the five analytical dimensions that influence how these forces manifest in specific contexts. This conceptual framework, adapted from Lamiño Jaramillo et al. (2022), helps clarify how a constellation of structural conditions and individual circumstances shapes migration decisions.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Structure of the Push-Pull Plus Theory of Migration. Source: Adapted from Lamiño Jaramillo et al. (2022).

The PPP theory identifies four types of functional drivers that interact dynamically to influence migration decisions (Van Hear et al. 2018). These factors form dynamic constellations that shape migration flows. Predisposing drivers refer to background conditions such as chronic poverty, weak institutions, or structural inequality, which make migration a viable or even necessary option for certain populations. Proximate drivers emerge when these conditions deteriorate to the point of being intolerable, prompting individuals or families to consider leaving. Precipitating drivers are immediate events or crises, such as natural disasters, political crackdowns, or sudden changes in law or policy, that act as catalysts for action. Mediating drivers encompass the resources, infrastructure, and social networks that either facilitate or hinder migration. These include access to transportation, communication technologies, financial means, and information about possible destinations (Van Hear 1998; Van Hear et al. 2018).

In addition to these four categories, the PPP framework introduces five analytical dimensions that shape how migration drivers operate in specific contexts. Locality refers to the influence of both origin and destination environments on migratory choices. Scale includes both geographic scales, such as local, national, or international, and social scales, including individuals, households, and communities. Selectivity highlights how demographic characteristics such as gender, age, ethnicity, or legal status affect migratory trajectories. Duration addresses the timeframe over which migration decisions are made, whether rapidly in response to acute danger or more gradually due to long-term decline. Tractability refers to the extent to which migration is culturally normalized or institutionally supported, such that it becomes a recognized and recurring strategy within a given society (Van Hear et al. 2018).

The Push-Pull Plus framework is especially relevant for examining contemporary migration flows in Central America, where long-term structural vulnerabilities intersect with acute socio-political pressures. Conditions such as entrenched poverty, weak governance, and limited access to public services can be understood as predisposing drivers. These are often compounded by proximate factors such as unemployment, rising insecurity, and environmental stress. Political instability and shifting migration policies in destination countries may act as precipitating events. Mediating factors, including access to transportation, financial support networks, and communication technologies, influence whether and how migration occurs. By capturing these layered interactions, the PPP framework offers a flexible yet structured approach for analyzing mobility in contexts characterized by both chronic and acute displacement pressures.

The five dimensions outlined in the PPP framework further enhance their relevance for analyzing migration from regions experiencing chronic instability and complex mobility patterns. The dimension of locality enables consideration of how both origin and destination contexts influence migration aspirations and feasibility. Scale highlights the multi-layered nature of mobility, encompassing individual, household, and community decisions that unfold across national borders. Selectivity highlights how age, gender, and legal status influence who migrates and the manner in which they do so. Duration helps capture variation in how quickly migration decisions are made, whether through rapid displacement or prolonged contemplation. Tractability accounts for how migration becomes socially embedded in specific contexts, where it may be normalized as a pathway to opportunity or survival. These dimensions enable a layered, context-sensitive analysis that bridges the structure and agency in migration studies.

While the PPP framework offers a helpful structure for identifying economic, environmental, and security-related migration drivers, recent scholarship emphasizes that mobility decisions also unfold within broader social systems characterized by unequal access, institutional discrimination, and racialized forms of governance. For example, Coen-Sánchez (2021) examines how systemic racism and structural inequities are reproduced across institutional contexts, providing a useful conceptual lens for understanding how access to protection and services may become stratified for people on the move. Relatedly, Coen-Sánchez et al. (2022) highlight how policy regimes shape vulnerability and access to essential services, demonstrating how governance systems can deepen precarity for already marginalized groups. Taken together, these perspectives complement the PPP approach by foregrounding how governance structures and unequal institutional environments shape the options, risks, and lived realities of migrants, particularly in transit and reception contexts.

This study draws on the PPP framework to deepen the understanding of how multiple factors interact in shaping migration decisions. Rather than treating push and pull elements as separate or fixed, the PPP approach emphasizes how long-standing conditions—such as poverty or political instability—can interact with more immediate events and available resources in specific contexts. This perspective enables a more comprehensive understanding of migration as a dynamic process shaped by a combination of structural pressures, personal circumstances, and evolving opportunities. The framework is particularly relevant for analyzing transit migration, where decisions are often made under uncertain and rapidly changing conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a mixed-methods design to examine the motivations, timing, and contextual factors that shape transit migration through Casa del Migrante San José, Honduras. Quantitative and qualitative components were implemented concurrently and later integrated. The quantitative phase provided demographic and flow characteristics, while the qualitative phase added depth to the narratives of migrant decision-making. The methodological approach was informed by the PPP framework, not as a procedural guide but as an analytic lens for interpreting how long-term conditions (predisposing and proximate drivers) interact with sudden opportunities or restrictions (precipitating drivers) and the support networks that mediate trajectories.

2.1. Design

This study employed a convergent mixed-methods research design, which aims to comprehensively understand phenomena by integrating quantitative and qualitative data within a single study (Creswell and Creswell 2018). This approach provides a more nuanced representation of complex issues and facilitates stronger inferences by integrating the breadth of survey data with the depth of interviews or observations. The integration of these data sources facilitates a holistic perspective that enhances both description and interpretation. To select participants, the study used convenience sampling, a non-probabilistic and non-random method based on ease of access and availability (Etikan et al. 2016; Golzar et al. 2022).

2.2. Study Site

The present study was conducted at Casa del Migrante San José, located in the municipality of Ocotepeque, Honduras. Founded in 2010 with support from the IOM, the center is the only migrant shelter on Honduras’s western border. It provides assistance to international migrants in transit, including children, adolescents, and pregnant women. The IOM contributes food, medicines, equipment, furniture, and specialized training for the shelter’s staff (IOM 2020).

2.3. Quantitative Phase

Two quantitative data sources were used in this phase. The first consisted of administrative registration records collected by Casa del Migrante San José between 2021 and 2022 for migrants passing through the shelter. It includes variables such as age, sex, nationality, migration status, and stated reasons for migration, and documents 3934 individuals from 24 countries. This dataset served as the baseline for describing migration flows and for contextualizing findings from the survey and interviews.

The second data source was a 20-item structured survey administered verbally to 75 migrants present at the shelter in December 2022. Unlike the administrative registration records, the survey captured variables not previously recorded, including educational level, marital status, intended destination, travel companions, access to communication technology, travel duration, and the presence of relatives abroad. Although administered face-to-face, the instrument remained quantitative in scope, focusing on verification of database records and collection of complementary statistical information.

Descriptive statistical procedures were used to analyze both datasets. Responses were reviewed for completeness, cleaned to address inconsistencies, and summarized using pivot tables to generate frequency distributions and identify patterns across demographic and mobility variables. Findings were visualized through tables and figures, illustrating national origins, monthly flow variation, and reported migration drivers.

2.4. Qualitative Phase

For the qualitative phase, the study employed a phenomenological case study approach to explore the factors influencing migration from the perspective of migrants themselves (Creswell and Plano Clark 2017; Manterola and Otzen 2017). Phenomenological methods are particularly valuable in qualitative research because they enable the researcher to capture the depth, richness, and complexity of lived experiences. This approach helps to uncover how individuals perceive and make sense of their migration journeys, thereby enriching the overall understanding of the phenomenon under study (Braun and Clarke 2006).

Consistent with the oral administration used in the quantitative phase, qualitative data were gathered through individual semi-structured interviews with a subsample of 75 participants drawn from the larger Pastoral database at the shelter in December 2022. These same 75 individuals had also completed the structured survey, allowing integration of quantitative and qualitative responses.

The interview guide comprised seven open-ended questions designed to explore the primary reasons for migration from the perspectives of migrants at Casa del Migrante. In addition to motivations, participants were asked about the major challenges they had faced during their journey, their reasons for traveling at that specific time of year, their occupations in their countries of origin, and the costs associated with the trip. This comprehensive approach facilitated a deeper understanding of the various factors that shape the migration experience.

Open coding is a useful technique in case study research, particularly for organizing and analyzing qualitative data collected through interviews and fieldwork (Saldaña 2016). Following Saldaña’s recommendations, the interview transcripts were systematically reviewed, along with associated notes and memos recorded before and after each session. Errors were identified and corrected during this review. The data were then divided into meaningful segments, and each transcript was examined line by line. Words and phrases that reflected the core of the participants’ experiences were manually identified and highlighted. From these observations, initial codes were developed. These codes were then grouped into broader categories, resulting in seven primary themes: reasons for migrating, major difficulties encountered during the journey, timing of the decision to migrate, occupations in the country of origin, travel costs, and the sources of funding used for the trip.

Pattern coding was then applied to consolidate the initial codes into broader themes, creating a more coherent and meaningful structure (Saldaña 2016). During this stage, the preliminary categories were grouped into broader themes, allowing for the identification of connections across data sources and facilitating the organization and interpretation of complex qualitative information (Saldaña 2016). This approach was essential for making the data more manageable and interpretable in preparation for deeper analysis (Morse and Richards 2002).

Lincoln and Guba (1985) proposed four key criteria to establish trustworthiness in qualitative research: credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability. Credibility is enhanced through strategies such as prolonged engagement with participants, sustained observation, and triangulation of data sources. Transferability depends on the provision of rich, detailed descriptions that enable readers to determine the applicability of findings to other contexts. Dependability is supported by systematic documentation and the creation of an audit trail that records the research process. Confirmability is achieved through practices such as peer review, participant validation, and reflective journaling, which help ensure that findings are grounded in the data rather than shaped by researcher bias (Ahmed 2024).

In this study, credibility was established through data triangulation across semi-structured interviews, structured surveys, and administrative registration records, which enabled cross-verification of information and enhanced the internal coherence of the results. Transferability was ensured by providing rich and contextualized descriptions of Casa del Migrante San José, the conditions of transit migration, and the demographic and experiential profiles of participants, allowing readers to assess the applicability of the findings to similar contexts. Dependability was maintained through systematic coding, clear documentation of analytical steps, and adherence to consistent procedures during data cleaning, categorization, and thematic development, ensuring that the process could be replicated. Finally, confirmability was achieved through participant validation and researcher reflexivity, including continuous comparison between data sources and reflective notes, which ensured that interpretations accurately represented participants’ perspectives rather than researchers’ assumptions.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Phase

To facilitate alignment with the PPP framework, the results are presented using PPP terminology. Structural conditions are identified as predisposing drivers, acute policy changes as precipitating drivers, and enabling factors such as information access and mobility networks as mediating drivers. The migrants surveyed and interviewed in the study came from 24 different countries, with the largest numbers originating from Venezuela, Honduras, and Nicaragua. In terms of demographic characteristics, men outnumbered women, and most participants fell within the age range of 21 to 40 years old. According to the Human Mobility Pastoral registration records, the majority of migrants were classified as being in transit rather than having been returned to their countries of origin. With respect to marital status, most migrants were single. Within the category of Educational Attainment of Migrants, the largest category consisted of individuals who had not completed secondary school, followed by those who had, a pattern also reflected in the interview data.

3.1.1. Country of Origin of Migrants Registered at Casa del Migrante

Between 2021 and 2022, the Casa del Migrante in Honduras recorded migrants from 24 countries. The majority came from Venezuela and Honduras, reflecting broader shifts in regional migration flows. Venezuela was the main country of origin, especially in 2022, when 1945 Venezuelans were recorded. The peak occurred in October 2022, following a U.S. policy announcement introducing new migration measures for Venezuelans. This trend reflects broader regional patterns, with a sharp rise in Venezuelan migration through the Darién region during the same period (IOM 2023). The spike reflects a precipitating driver, triggered by U.S. policy announcements that temporarily reshaped migration feasibility and timing. Table 1 shows the country of origin from the registered migrants at Casa del Migrante.

Table 1.

Country of Origin of Migrants Registered at Casa del Migrante (2021–2022).

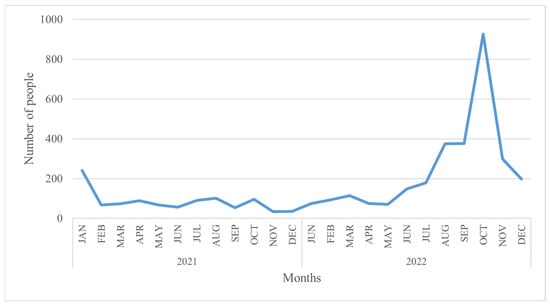

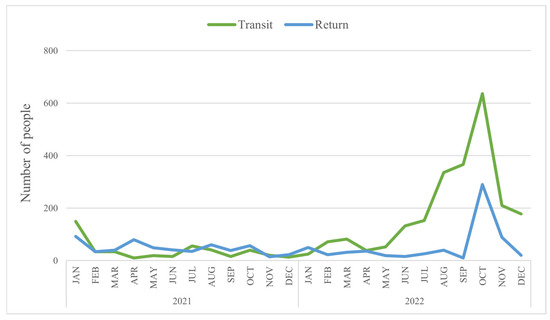

3.1.2. Monthly Trends in Migration Flow

According to monthly records from Casa del Migrante, a total of 3934 individuals were registered between January 2021 and December 2022, with an average of 164 people per month. During 2021, arrivals remained relatively low and stable, fluctuating between a minimum of 34 people in November and a maximum of 241 in January. In contrast, 2022 showed a marked increase in migration flows, beginning with moderate monthly totals and intensifying sharply in the second half of the year. The highest monthly value was recorded in October 2022, when 926 individuals were registered, the peak of the two-year period, while the lowest point across both years occurred in November 2021, with only 34 individuals. A secondary peak appeared in September 2022, with 376 people signaling the onset of the rapid surge that culminated in October. The October peak coincided with a policy announcement by the United States Government on 12 October 2022, outlining a new migration process for Venezuelans that combined enforcement measures with the promotion of legal pathways. This announcement introduced a new parole process for Venezuelans with U.S. sponsors that provided a lawful pathway for temporary entry while tightening consequences for irregular crossings. This created both an incentive for rapid departure and a deterrent for unauthorized entry (U.S. Department of Homeland Security 2022). This pattern demonstrates how policy announcements may function as precipitating drivers within the PPP framework, accelerating migration already primed by existing structural and economic pressures. Figure 2 shows the monthly migration trend from 2021 to 2022.

Figure 2.

Monthly number of migrants registered at Casa del Migrante from 2021 to 2022. Source: Administrative registration records collected by Casa del Migrante San José during 2021 and 2022.

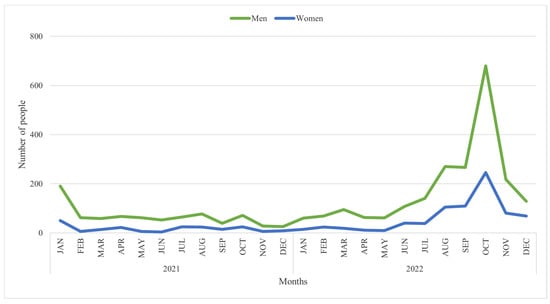

3.1.3. Gender Dynamics in Transit Migration

Based on the monthly records from Casa del Migrante, male arrivals remained consistently higher than female arrivals throughout 2021–2022. Men averaged 123 migrants per month and women averaged 41, reflecting a persistent gender gap in the flow. According to the data in Figure 3, the lowest monthly male value occurred in December 2021, with 26 men, while the highest was reached in October 2022, with 680 men. For women, the lowest monthly value appeared in June 2021, with 4 women, and the highest likewise occurred in October 2022, with 246 women. This pattern aligns with PPP’s selectivity dimension, where men disproportionately assume the risks and costs associated with irregular transit. These differences reflect how gender roles and socioeconomic conditions shape migration patterns. Between 2021 and mid-2022, male migration consistently surpassed female migration at Casa del Migrante, with a sharp rise in male migrants from June 2022. While employment is a key driver for both sexes, women often seek education and family stability, whereas men are more motivated by freedom and income (Escribano 2000). In 2022, Honduras recorded over 94,000 male and 48,000 female migrants in transit, with most heading to the U.S. That same year, 80,855 Hondurans were returned, 65% of whom were men (CONADEH 2022).

Figure 3.

Monthly Number of Migrants Registered at Casa del Migrante, by Sex (2021–2022). Source: Administrative registration records collected by Casa del Migrante San José during 2021 and 2022.

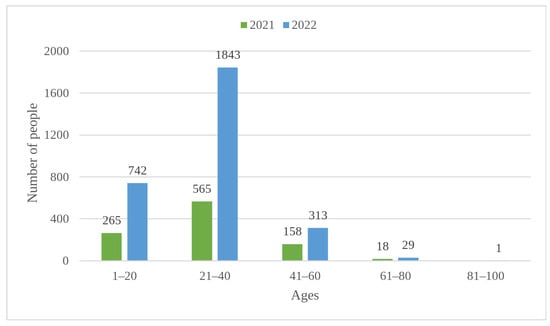

3.1.4. Age Distribution of Migrants Registered at Casa del Migrante

Most migrants registered at Casa del Migrante were young people between 21 and 40 years old, highlighting the demographic impact of migration on both origin and destination regions. Between 2021 and 2022, most individuals registered at Casa del Migrante were between 21 and 40 years old, followed by those aged 1 to 20. Adults between 41 and 60 ranked third, while a smaller proportion were aged 60 and above (Figure 4). This trend reflects the fact that migrant populations are typically young and in their productive and reproductive years. This reflects PPP’s emphasis on selectivity and duration, as migration is more feasible for adults in prime working ages who can mobilize quickly in response to shocks or opportunities. As a result, migration tends to rejuvenate destination regions and age those of origin. Destination areas may see increased birth rates and lower mortality, while the opposite occurs in sending regions. Migration thus plays a key role in demographic change, directly and indirectly affecting population growth and age-gender structure. Regions losing population to migration not only decline demographically but also experience shifts in their natural growth patterns (CONAPO 2012).

Figure 4.

Age of individuals registered at Casa del Migrante (2021–2022). Source: Administrative registration records collected by Casa del Migrante San José during 2021 and 2022.

3.1.5. Migrant Status Registered at Casa del Migrante

Between 2021 and 2022, the number of migrants in transit increased significantly, particularly in 2022, highlighting shifting regional mobility patterns associated with Venezuelan migration flows. According to the IOM (2016), return migration refers to the process by which individuals return to their country of origin or habitual residence after having lived in another country for at least one year, whether voluntarily or involuntarily. Migrants in transit, on the other hand, are those moving toward their final destination, passing through an intermediate stage between departure and arrival (ACNUDH 2015). Over the 24-month period, monthly counts of migrants in transit ranged from a low of 10 people in April 2021 to a peak of 636 people in October 2022, with a strong surge also observed in September 2022 (366 people); overall, transit flows averaged about 114 people per month. Return migration exhibited a distinct pattern: the lowest value was recorded in September 2022, with 10 returnees, while the highest peak occurred in October 2022, with 290 returnees, resulting in an overall average of approximately 50 returnees per month. The predominance of individuals in transit rather than return reflects the role of mediating drivers, including social networks, available routes, and cross-border information flows, that enable continued movement. Figure 5 shows the trend of return vs. transit migrants.

Figure 5.

Migration status of migrants registered monthly at Casa del Migrante (2021–2022). Source: Administrative registration records collected by Casa del Migrante San José during 2021 and 2022.

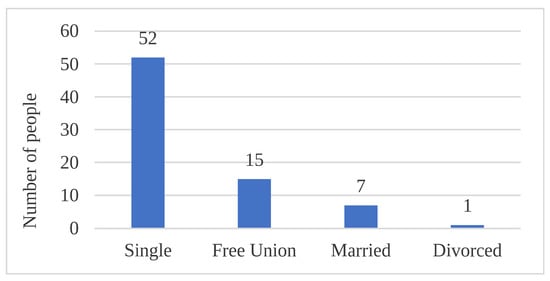

3.1.6. Marital Status of Migrants

In December 2022, the majority of individuals who migrated were single, followed by those in consensual unions. Married individuals represented a smaller percentage, and only one person was registered as divorced. According to Rodríguez Martínez (2000), marital status is an important explanatory variable in relation to migration, as single individuals and those who have recently entered a union are more willing to relocate. From a PPP perspective, marital status primarily operates through the selectivity dimension, as lower household obligations reduce constraints on mobility and strengthen mediating drivers that facilitate migration. In contrast, married people or those with children are less likely to migrate due to the high costs of relocation, their emotional and cultural ties to their place of origin, and other psychological barriers (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Marital Status of Migrants Registered at Casa del Migrante (December 2022). Source: Structured Survey at Casa del Migrante San José, December 2022.

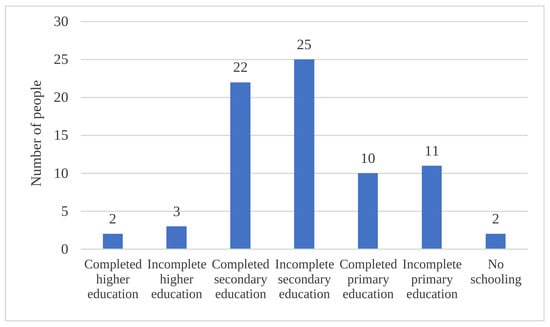

3.1.7. Educational Attainment of Migrants

The educational profile of migrants reveals important differences that influence their migration decisions and opportunities. Most individuals reported incomplete secondary education at the time of registration. In December 2022, most individuals registered had a low educational level, without having completed secondary education. They were followed by those who had completed secondary education, with smaller proportions having completed or not completed primary education. In contrast, fewer individuals had completed or incomplete higher education, and a minimal number had no schooling at all (Figure 7). It is important to note that migrants are not a random group and differ from non-migrants in several aspects, such as their educational level, which allows them to be better informed, access improved economic opportunities, and finance their migration (Peláez et al. 2021). From a PPP perspective, education operates through the selectivity dimension, enabling individuals to more effectively access mediating drivers such as information, networks, and resources that facilitate migration.

Figure 7.

Educational Level of Migrants Registered at Casa del Migrante (December 2022). Source: Structured Survey at Casa del Migrante San José, December 2022.

3.1.8. Main Reasons for Migration

According to the records from the Migrant Shelter database, provided by the Pastoral de Movilidad Humana, 84 percent of respondents in 2021 stated that their primary motivation for migrating was the country’s economic situation. In 2022, this figure increased to 87 percent. By contrast, a smaller percentage of migrants reported leaving due to a lack of job opportunities or in search of international protection or refugee status in Mexico. From an economic and labor perspective, these trends reflect migration driven by the pursuit of employment and higher wages, largely influenced by the demand for low-cost labor in diversified markets such as the United States (Rodríguez Martínez 2000). Table 2 presents the main reasons for migration, based on responses collected by the Pastoral de Movilidad Humana during 2021 and 2022. These data highlight the factors that compelled individuals to leave their countries of origin in search of improved opportunities or safer living conditions. Both “the country’s economy” and “lack of employment opportunities” point to economic motivations at different scales. Although presented separately in the table, taken together, these responses show that nearly all participants cited economic hardship as a central motivation for migration. Economic hardship (“country’s economy” and “lack of employment”) represents a clear predisposing driver, rooted in long-term structural pressures; meanwhile, security concerns and protection needs align with proximate drivers that translate structural adversity into active migration intentions.

Table 2.

Primary reasons for migration among individuals registered at Casa del Migrante, by year (2021 to 2022).

3.2. Qualitative Phase

The qualitative section revealed several emerging themes that complemented the findings from the quantitative phase. These insights were drawn from interviews conducted in December 2022. Table 3 presents the primary reasons that motivated individuals to migrate and leave their countries of origin. It provides a detailed view of the factors influencing their decisions to seek a new life elsewhere. These motivations range from economic hardship and political instability to family reunification and personal aspirations. Additionally, the findings highlight how global events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, have played a significant role in shaping migration patterns.

Table 3.

Primary reasons why individuals were motivated to migrate and leave their countries of origin.

3.2.1. Migration Motivations: Insights from Migrant Narratives

The testimonies of migrants reveal a complex interplay of factors influencing their decisions to leave their countries of origin. Through their narratives, five key themes emerged as primary motivations for migration: sociopolitical factors, personal and family circumstances, economic hardship, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, and unplanned travel. These accounts offer firsthand insights into the challenges, aspirations, and pressing conditions that shape migratory decisions, providing a deeper understanding of the structural and personal forces driving these journeys. The following sections explore each of these themes in detail, highlighting the voices and lived experiences of the migrants themselves. To align the qualitative findings with the PPP framework, each theme below is interpreted using PPP’s categories of predisposing, proximate, and precipitating drivers, along with mediating capacities.

Theme 1: Sociopolitical Factors

One of the primary reasons for migration, particularly from Venezuela, is the deterioration of political and social conditions. Many migrants expressed that they took advantage of a perceived opportunity to migrate due to recent policies in the United States. One migrant stated: “I traveled now for the opportunity for Venezuelans to go to the United States because I took advantage of the fact that others were traveling.”

Another significant factor influencing migration is the escalation of violence in countries of origin. “Because there was a lot of violence,” while another emphasized the dire conditions in Venezuela, explaining that “the situation was extremely bad due to constant threats.” A third participant reinforced this perspective by noting that migration occurred because “the situation had become unbearable as a result of ongoing threats.”

In addition to these extreme conditions, participants described experiences of direct violence and rights violations during transit. One testimony explained, “In the Darién, my phone and money were stolen. Later, at the border, migration authorities detained me and put me in a holding cell; they take away all your belongings.” These experiences illustrate how theft, detention, and the absence of institutional protection deepen migrants’ vulnerability during transit. This insecurity is further compounded by the presence of organized criminal groups along migration routes, as another participant noted: “It has become extremely severe, particularly due to cartel activity. Women are trafficked, and people often remain silent out of fear.”

Moreover, several narratives convey a pervasive sense of abandonment and uncertainty that extends across the entire migration process. As one participant expressed, “The insecurity is not knowing whether you will arrive alive, whether you will be able to return when you run out of money, when you lose everything and have no way to communicate. They demand that you pay a certain amount of money in order to let you pass. It is an insecurity that ultimately becomes a stifled cry that leads nowhere.” These statements underscore how security concerns and political instability have become critical drivers of migration.

Finally, global events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, have also impacted migration patterns. Some individuals reported being forced to leave their country due to the direct impact of the pandemic. One migrant mentioned: “We left China because of the pandemic.” This highlights how sudden crises can drastically reshape migration decisions, prompting individuals to seek safer or more stable environments. These accounts illustrate proximate drivers, as escalating violence, threats, and institutional erosion transform chronic instability into immediate pressure to migrate.

Theme 2: Family Reasons

Family ties strongly influenced migration decisions, both as a pull factor toward destination countries and as a driving force to leave. Several migrants explained that their primary motivation was to reunite with parents, partners, or children after long periods of separation. One person said, “I really wanted to spend the holidays with my family, and there’s no work at all in January.” Another participant expressed: “I am going to reunite with my mother in Nicaragua. I have tried to migrate more than 15 times… but my main reasons are my dreams, and that at home there was no food.” This account illustrates how the desire for family unity persists even in circumstances of scarcity, where rejoining a parent becomes not only a personal aspiration but also a response to worsening conditions at home.

Families also played an essential role as support systems, making migration possible. In some cases, extended relatives provided money, logistics, and reception at destination points. As one migrant recalled, “Support from family and selling everything we had; that is how we were able to leave.” A second testimony reinforces the same pattern through combined work and family assistance, explaining, “Through work and with support from my family, I sold everything I owned.” These accounts demonstrate that family networks not only motivate migration, but also enable it materially, transforming desire into action.

Family-related stories reflect mediating capacities within the PPP framework, where emotional support, remittances, and family networks shape the feasibility and direction of movement. A third group of participants described migration as a decision made primarily for dependents rather than for themselves. One explained, “My reason is my children. I want something better for them even if it means sacrifice along the way,” while another emphasized the economic dimension of this decision, stating the urgency “to support my family financially.” Here, family becomes the rationale for movement, the financial mechanism that sustains it, and the future horizon migrants imagine when they decide to leave. Taken together, these narratives show that family is not merely an emotional motivator, but a structuring force that determines when migration becomes possible, who can migrate, and under what conditions. Within the PPP framework, family networks operate as mediating capacities, lowering barriers to movement and converting aspiration into action.

Theme 3: Economic Factors

Economic difficulties are among the most commonly cited reasons for migration. Many migrants experience severe financial hardship, struggling to support their families due to high living costs and a lack of stable employment. Economic motivations correspond to predisposing drivers, revealing long-term structural hardship that normalizes migration as an economic survival strategy. One individual stated: “The situation in the country and the lack of job opportunities make it very difficult to earn enough to support my children and, in the name of God, fulfill my children’s dreams.” Another echoed these struggles: “I decided to travel because, to start with, I did not miss a day working there, and the way of living was very ugly. “There is work, but living has become really expensive.” Some individuals made significant personal and material sacrifices to migrate, such as selling property or leaving jobs behind in pursuit of better opportunities. One participant shared: “In those circumstances, we had the opportunity to travel. We sold our motorcycle, we quit our job, and we do not even have a house in Colombia.” A similar account reveals broader economic strain: “We sold our family home in China and used credit cards to obtain some funds to cover travel expenses.” while another described survival strategies during transit: “People with good hearts helped us, and we worked wherever we could along the way.” Additionally, another participant stated: “We received donations along the way, and by selling candy that people gave us to sell.”

Access to quality education and better job prospects also emerged as strong motivators. Some migrants saw opportunities abroad as a pathway to a better future through education or language learning. One individual expressed: “Firstly, because I wanted to study in the United States, […] and because I liked English.” Within this pattern, some differences across gender appeared: women more frequently associated migration with improving education and achieving family stability, whereas men more often emphasized employment, economic autonomy, or earning potential.

Theme 4: Unplanned Travel

The qualitative findings highlight the spontaneous and reactive nature of migration for some individuals, where decisions are not always the result of careful planning or long-term aspirations. As illustrated by the quotes, migration can be shaped by immediate circumstances—such as personal relationships or unexpected opportunities—rather than strategic, future-oriented plans. One individual described their decision-making process: “I just thought about traveling; I did not pay attention to the date or anything else.” This lack of planning was closely tied to material deprivation, as another individual explained that migration occurred “because I no longer had any means of subsistence.” A third participant further emphasized the constrained nature of this decision, noting, “I did not really decide; one travels when the moment allows it, because if it were a personal decision, there would only be one journey.” This reflects how some people may migrate impulsively, without fully considering the long-term implications.

Similarly, another migrant shared how external influences shaped their migration: “I decided to travel at this time because my cousin’s wife and his sister were going to travel with them, and that was when he sent us the money to come.” This example demonstrates how social networks and economic support can be pivotal in triggering migration decisions. These experiences suggest that migration is not always driven by clearly defined goals, but can also be influenced by unforeseen personal, economic, and social factors. These reactive decisions illustrate precipitating drivers, where sudden threats, unexpected opportunities, or network signals accelerate the timing of migration among those already facing cumulative pressures.

4. Discussion

This study suggests that the PPP framework is analytically useful for understanding contemporary transit migration through Honduras, and the findings are consistent with previous work, such as de Haas’s (2021) findings, on the multidimensional nature of migration drivers. Across our data, the four functional drivers—predisposing, proximate, precipitating, and mediating—operate as an interlocking system rather than as discrete, sequential forces. Predisposing conditions such as chronic poverty, weak institutions, and long-standing inequality establish the structural baseline that normalizes mobility as a plausible life strategy (Massey et al. 1993; Taylor 2006). Proximate pressures—including inflation, unemployment, and insecurity—then convert latent aspirations into concrete intentions to move (Czaika and de Haas 2014). The timing of departures is frequently shaped by precipitating events, notably policy shifts in destination countries that temporarily widen or redefine legal pathways (Menjívar and Abrego 2012). Finally, mediating elements—information flows, social and financial networks, and institutional supports like Casa del Migrante—determine whether intentions can be translated into feasible journeys (Bakewell 2010).

The empirical record from Casa del Migrante is especially instructive on this timing dimension. Monthly arrivals remained modest until mid-2022, then surged to a peak in October, coinciding with announcements about humanitarian processes for Venezuelans (IOM 2023). This pattern shows how policy communication can act as a precipitating catalyst, amplifying flows already primed by structural and proximate pressures. The composition further underscores PPP’s selectivity dimension: migrants were mainly young adults (21–40), mostly male, and often single or in consensual unions. Such profiles align with the notion that migration entails risks and costs younger, less encumbered individuals are more likely to assume (CONAPO 2012).

Educational attainment adds nuance to this selectivity. Most migrants reported incomplete secondary schooling, with smaller shares completing secondary or higher levels (Peláez et al. 2021). This distribution challenges simplistic binaries that frame migrants as either the “most skilled” or “least skilled.” Instead, it suggests a population with some formal education and demonstrated capability to navigate complex routes and information, but insufficient local opportunity structures to secure stable, dignified livelihoods at home. This reflects a profile of individuals with some formal education who possess enough cultural capital, literacy, and access to information to make international mobility feasible, yet still encounter limited pathways to stable employment or upward mobility in their countries of origin. Peláez et al. (2021) note that migrants are not randomly drawn from the general population; rather, they tend to have comparatively higher levels of education than non-migrants, which enables them to access information, respond to opportunities, apply transferable skills, and finance mobility. In PPP terms, this is where predisposing constraints (weak labor markets) intersect with mediating capacities (basic education, digital literacy, networks) to enable movement under uncertainty (de Haas 2021; Carling and Talleraas 2016).

Motivationally, the quantitative data are unambiguous: over four-fifths of respondents cited the economic situation as the primary reason for leaving. Yet qualitative narratives complicate this picture in productive ways. Interviewees pointed to sociopolitical degradation (“could no longer endure the violence”), family imperatives (reunification, providing for children), and unplanned or opportunistic departures (“I did not have a plan”). These accounts illuminate how proximate economic hardship was typically articulated in relation to other constraints rather than as a standalone motivation; it is entangled with threats to physical integrity, aspirations for family stability, and the contingent availability of resources and routes. Importantly, the theme of “unplanned travel” is not synonymous with irrationality. As Bakewell (2010) argues, even seemingly impulsive moves can be rational adaptations to volatility, where windows of opportunity open and close rapidly and where social ties (e.g., a relative financing a ticket) instantly transform feasibility.

The scale and locality dimensions of PPP also surface clearly. Most pathways are international and multistage, routing through multiple countries before Honduras. At each node, migrants recalibrate plans in light of updated information, enforcement risks, costs, and health constraints. Similar dynamics have been documented by Schapendonk (2012) and Mainwaring and Brigden (2016), who highlight the iterative and adaptive character of mobility trajectories. This continual recalibration illustrates PPP’s duration dimension: some decisions are incubated over months, others are precipitous, triggered by sudden shocks or perceived openings. Tractability appears high in communities with established migration histories, where moving abroad is culturally legible, institutionally scaffolded by networks, and often seen as a default strategy when local futures narrow (Van Hear et al. 2018).

The patterns observed, particularly the emphasis on uncertainty, perceived risk, and constrained access to institutional support, suggest that migration decisions are shaped not only by insecurity or economic pressures but also by the institutional environments that migrants navigate. Experiences of uncertainty, perceived risk, and uneven access to protection echo scholarship documenting how systemic inequities and governance structures shape vulnerability (Coen-Sánchez 2021; Coen-Sánchez et al. 2022). At the same time, patterns of decision-making, perceived feasibility, and navigational strategies resonate with arguments that migrants draw on different forms of cultural capital when navigating uncertainty and institutional barriers (Coen-Sánchez 2025).

Methodologically, the convergent mixed-methods design added explanatory power. Cross-sectional counts identified who, when, and how many; interviews revealed why and how decisions were enacted. Together, they show that migration decisions are not solely economic acts but assemblages of structural pressure, sudden triggers, and social mediation, consistent with de Haas (2021) and Van Hear et al. (2018). For researchers, this argues for designs that can register both temporal spikes (policy-linked surges) and the slower tides of structural change.

Limitations of the Present Study

While the PPP framework provides a useful structure for interpreting these patterns, it does not fully capture all dimensions of transit migration. Decisions made quickly, under pressure, or amid rapidly changing conditions may not align neatly with the sequential logic the framework suggests (Hagen-Zanker et al. 2023). The approach may also understate the emotional and relational influences, including fear, trust, family expectations, and informal information flows that shaped many of the experiences described in the interviews (Siviş et al. 2024). These considerations indicate that PPP is a helpful analytical tool, but it does not exhaust the complexity observed in lived decision-making during transit.

As with most field-based migration research, the findings are shaped by the sampling strategy available in the study context. Because participants were recruited through convenience sampling at a single shelter, the experiences described may reflect the specific demographic, logistical, and motivational characteristics of migrants passing through Casa del Migrante rather than the full diversity of transit migration in the region. While the combination of quantitative and qualitative data provides internal consistency and useful patterns, the results should be interpreted as analytically informative rather than statistically generalizable.

This study was not designed to conduct subgroup analysis across gender, age, or nationality, and therefore, the findings should not be interpreted as comparative across demographic groups. While gender was recorded, the analysis focused on overall patterns in motivations rather than systematic differences between categories. However, some interview responses pointed to gendered dynamics in the migration experience, including references by women to heightened vulnerability during transit through certain corridors such as the Darién crossing. Because these accounts relate to experiences during the journey rather than initial motivations, they fall outside the scope of the thematic framework used in this study. Future research with a design oriented toward risk exposure, safety, or protection ecosystems could explore these patterns in greater depth.

An additional limitation concerns the analytical scope of the qualitative component. While the thematic analysis identified recurring dimensions shaping migration decisions, it was not designed to quantify case-level co-occurrence or to model specific combinations of drivers across interviews. Themes were developed as analytically distinct but non-exclusive categories intended to capture patterns of meaning rather than to function as variables for cross-tabulation. For example, experiences of violence were coded as part of broader sociopolitical factors rather than as a standalone theme. A more granular examination of how specific drivers intersect at the individual level would require a dedicated quantitative or mixed-methods design with variables explicitly operationalized for that purpose.

5. Conclusions

This study examined transit migration through Honduras using a convergent mixed-methods approach, integrating 3934 records from the Human Mobility Pastoral database between 2021 and 2022 with semi-structured interviews conducted with 75 migrants at Casa del Migrante San José. The findings reveal a notable increase in flows during 2022, particularly among Venezuelans, with October representing a peak that coincided with U.S. policy announcements regarding humanitarian entry processes. This illustrates how policy shifts can act as precipitating drivers, intensifying flows already primed by structural hardship.

Demographically, most migrants were men between 21 and 40 years old, frequently single or in consensual unions, and with incomplete secondary education. This profile underscores the selectivity dimension of the Push-Pull Plus (PPP) framework, as younger individuals with mid-level education and fewer family obligations are more likely to assume the risks and costs of migration. Economic hardship and unemployment were the most frequently cited motivations, followed by family-related reasons such as reunification, and, to a lesser extent, sociopolitical instability. Qualitative narratives further revealed themes of violence, insecurity, and unplanned or opportunistic departures, highlighting that migration decisions often combine structural constraints with sudden opportunities.

Viewed through the PPP framework, these findings confirm that migration results from the interplay of long-term predisposing pressures (poverty, inequality, weak institutions) with proximate factors (inflation, unemployment, insecurity), while precipitating events—such as policy announcements or crises—trigger departures. Mediating elements, including social networks, financial support, and institutional aid from shelters, determine feasibility. The multidimensional nature of these drivers demonstrates that migration is neither a purely economic decision nor an entirely spontaneous act, but a dynamic process shaped by structural pressures, short-term triggers, and available resources.

Practically, the study highlights the urgent need to expand shelter capacity at Casa del Migrante San José, where overcrowding remains a persistent challenge. Strengthening inter-agency collaboration with local authorities and civil society would improve coordination and service delivery. Innovative communication tools, including audiovisual storytelling, could also raise awareness and humanize migration narratives while safeguarding anonymity.

These findings carry three policy implications. First, policies based solely on deterrence may produce unintended outcomes. While recent policy changes in the United States have coincided with a marked reduction in reported irregular encounters during 2024–2025, the longer-term effects of deterrence-focused approaches remain contested. When legal migration pathways remain limited and the structural and proximate factors that influence migration decisions are unchanged, such measures may shift, delay, or reconfigure mobility rather than produce durable reductions in irregular movement. Whether recent declines reflect a sustained transformation of migration dynamics or a temporary response to heightened enforcement remains an open empirical question with important humanitarian and governance implications.

Second, interventions should be multi-level and sequenced: mitigate predisposing drivers (inequality, labor exclusion, insecurity) while expanding protected, predictable channels that reduce the need for irregular transit. Third, mediating infrastructures matter. Shelters, legal aid, remittance mechanisms, and accurate information can reduce harm, improve decision quality, and lower the transaction costs of regularization where possible. This means designing reception and support systems that not only reduce harm but also provide space, information, and legal pathways that allow migrants to make informed and voluntary decisions about their journeys, rather than being constrained by uncertainty or coercion.

An emerging policy question concerns how reductions in irregular migration should be evaluated when they occur in response to restrictive measures. Future research could examine whether declines associated with such policies reflect a lasting shift in migration dynamics or a temporary response, and how these outcomes should be understood in relation to humanitarian impacts and overall governance goals

Future research could also extend databases to include earlier years and data from other shelters, border crossings, and transit hubs to allow for a broader regional analysis. Improved data collection tools and systematic documentation of migrant experiences would enhance accuracy and provide stronger evidence for policy design. Addressing both humanitarian needs and structural root causes remains essential to ensure responses that are comprehensive, sustainable, and respectful of migrants’ lived realities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R., B.T., J.C.F. and M.G.; methodology, M.R., B.T. and M.G.; data curation, M.R. and B.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R., P.L. and B.T.; writing—review and editing, M.R., P.L. and B.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and, under the direction of Dr. Lamiño during his affiliation with Texas Tech University, received approval on 17 May 2019 from the Texas Tech University Institutional Review Board, Human Research Protection Program (approval code: IRB2019-561).

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. Written consent was not collected due to the participants’ vulnerable status as migrants and to protect their anonymity and comfort during data collection. All participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, voluntary nature, and confidentiality safeguards before giving their consent.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PPP | Push-Pull Plus |

| CONAPO | National Population Council |

| CONADEH | National Commissioner for Human Rights |

| IOM | International Organization for Migration |

| ACNUDH | Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights |

References

- ACNUDH, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2015. Situation of Migrants in Transit. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/2021-12/INT_CMW_INF_7940_S.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Ahmed, Sirwan Khalid. 2024. The pillars of trustworthiness in qualitative research. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health 2: 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apablaza Riquelme, Marta Verónica. 2010. Migraciones Centroamericanas a Estados Unidos en el Contexto de la Globalización (1980–2010). Master’s thesis, University of Chile, Santiago, Chile. Available online: https://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/109961 (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Aruj, Roberto S. 2008. Causes, consequences, effects, and impact of migration in Latin America. Papeles de Población 14: 95–116. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/112/11205505_2.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Bakewell, Oliver. 2010. Some reflections on structure and agency in migration theory. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36: 1689–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhugra, Dinesh, and Matthew A. Becker. 2005. Migration, cultural bereavement and cultural identity. World Psychiatry 4: 18. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1414713 (accessed on 6 January 2026). [PubMed]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunarska, Zuzanna, and Artjoms Ivlevs. 2023. Forced displacement and subsequent generations’ migration intentions: Intergenerational transmission of family migration capital. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50: 2423–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canales Cerón, Alejandro I., Carmen Rosa De León-Escribano, and Juan Alberto Fuentes. 2019. Development and Migration: Challenges and Opportunities in the Countries of Northern Central America. CEPAL Report No. LC/MEX/TS.2019/7. Santiago: Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/44649 (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Carling, Jørgen, and Cathrine Talleraas. 2016. Root Causes and Drivers of Migration: Implications for Humanitarian Efforts and Development Cooperation. PRIO Paper. Oslo: Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO). [Google Scholar]

- Castles, Stephen, Hein de Haas, and Mark J. Miller. 2014. The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Cecchini, Simone, and Jorge Martínez Pizarro. 2023. International Migration in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Development and Rights Perspective. CEPAL Review No. 141. Santiago: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/4124169a-d6db-4a62-9280-34517e2c8a57/content (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Coen-Sánchez, Karine. 2021. Systematically Disenfranchised: Addressing Anti-Black Racism Cannot Happen Without Teaching About White Privilege. The Sociological Review Magazine. September 7. Available online: https://thesociologicalreview.org/magazine/september-2021/new-solidarities/systematically-disenfranchised/ (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Coen-Sánchez, Karine. 2025. Polite racism and cultural capital: Afro-caribbean negotiations of blackness in Canada. Social Sciences 14: 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen-Sánchez, Karine, Bassey Ebenso, Ieman Mona El-Mowafi, Maria Berghs, Dina Idriss-Wheeler, and Saani Yaya. 2022. Repercussions of overturning Roe v. Wade for women across systems and beyond borders. Reproductive Health 19: 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W., and J. David Creswell. 2018. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W., and Vicki L. Plano Clark. 2017. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Czaika, Mathias, and Hein de Haas. 2014. The globalization of migration: Has the world become more migratory? International Migration Review 48: 283–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haas, Hein. 2021. A theory of migration: The aspirations-capabilities framework. Comparative Migration Studies 9: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano, Antonio Izquierdo. 2000. The migration project of undocumented migrants by gender. Papers: Revista de Sociologia 60: 225–40. Available online: https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/papers/02102862n60/02102862n60p225.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Etikan, Ilker, Sulaiman Abubakar Musa, and Rukayya Sunusi Alkassim. 2016. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics 5: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankema, Ewout. 2010. The colonial roots of land inequality: Geography, factor endowments, or institutions? Economic History Review 63: 418–51. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27771619 (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Galeano, Juan. 2011. Castles, Stephen y Miller, Mark J. (2009): The age of migration: International population movements in modern world. Documents d’Anàlisi Geogràfica 57: 575–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golzar, Jawad, Shagofah Noor, and Omid Tajik. 2022. Convenience Sampling. International Journal of Education & Language Studies 1: 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen-Zanker, Jessica, Gemma Hennessey, and Caterina Mazzilli. 2023. Subjective and intangible factors in migration decision-making: A review of side-lined literature. Migration Studies 11: 349–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, Raymond Alexander. 2024. Land access, land use, and agricultural practice: Political ecologies of servitude at colonial Ollantaytambo (1550–1770). Journal of Political Ecology 32: 5868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2016. The Scalabrinian Sisters recognize IOM for supporting migrants in Honduras. Available online: https://www.iom.int/es/news/las-hermanas-scalabrinianas-reconocen-la-oim-por-el-apoyo-los-migrantes-en-honduras (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2019. Glossary on Migration. International Migration Law No. 34. Geneva: IOM. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iml_34_glossary.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2020. World Migration Report 2020. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2020.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2023. Tendencias migratorias en las américas. Available online: https://lac.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1446/files/documents/2023-12/espanol-tendencias-julio-setiembre-de-2023-1.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Lamiño Jaramillo, Pablo, Amy E. Boren-Alpizar, Sarahi Morales, Scott Burris, and Carlos Carpio. 2022. A love-hate relationship: An ethnographic study of migration with Lenca women in rural Honduras. Migration and Development 11: 1218–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Everett S. 1966. A theory of migration. Demography 3: 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Yvonna S., and Egon G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mainwaring, Ċetta, and Noelle Brigden. 2016. Beyond the border: Clandestine migration journeys. Geopolitics 21: 243–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manterola, Carlos, and Tamara Otzen. 2017. Checklist for reporting results using observational descriptive studies as research designs: The MInCir initiative. International Journal of Morphology 35: 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, Douglas S., Joaquín Arango, Graeme Hugo, Ali Kouaouci, Adela Pellegrino, and J. Edward Taylor. 1993. Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal. Population and Development Review 19: 431–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuliffe, Marie, and Anna Triandafyllidou. 2022. World Migration Report 2022. Geneva: International Organization for Migration (IOM). [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar, Cecilia, and Leisy Abrego. 2012. Legal violence: Immigration law and the lives of Central American immigrants. American Journal of Sociology 117: 1380–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, Janice M., and Lyn Richards. 2002. The integrity of qualitative research. In Readme First for a User’s Guide to Qualitative Method. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- National Commissioner for Human Rights (CONADEH). 2022. Entre enero y el 15 de diciembre del 2022: En medio de abusos y violaciones a sus derechos, más de 178,300 migrantes transitaron por Honduras. Tegucigalpa: CONADEH. Available online: https://conadeh.hn/?p=841 (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- National Population Council (CONAPO). 2012. Algunos efectos de la migración internacional en los lugares de origen y destino. Available online: http://www.conapo.gob.mx/work/models/CONAPO/intensidad_migratoria/pdf/Efectos.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Peláez, Oscar A., Adriana María Gallego Henao, Leisy Magdali Arroyave Taborda, and Juan Luis Gaviria Pérez. 2021. Migration as a social phenomenon affecting education, the economy, and overall well-being. Revista de Ciencias Sociales (Ve) 27: 149–59. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/280/28069360011/28069360011.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Perdomo, Rodulio, Ariel Torres Funes, and Frances Bennaton. 2020. Culture of Exile: Causes and Consequences of Honduran Migration (1980–2020). Available online: https://oi-files-cng-v2-prod.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/centroamerica.oxfam.org/s3fs-public/file_attachments/Culture%20of%20Exile%20-%20Causes%20and%20Consequences%20of%20Honduran%20migration%20%281980-2020%29.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Rodríguez Martínez, Miriam. 2000. La Migracion Inter Regional de América Latina: Problemas y Desafíos. Available online: https://bibliotecavirtual.clacso.org.ar/ar/libros/cuba/cemi/miginter.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Saldaña, Johnny. 2016. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Schapendonk, Joris. 2012. Migrants’ Im/mobilities on their way to the EU: Lost in transit? Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 103: 577–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siviş, Selin, Verena K. Brändle, Jakob-Moritz Eberl, Sophia Wyatt, Kathryn Braun, Iman Metwally, and Hajo G. Boomgaarden. 2024. Oscillating between hope and despair: Understanding Migrants’ reflections on ambivalence in ‘Transit’. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa, Eugenio. 2021. Las bases sociales de la migración y la salida como la opción ante la crisis. El caso de Honduras. Cuadernos Intercambio sobre Centroamérica y el Caribe 19: E51315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, David. 2008. Causas y efectos de la migración internacional. Perspectivas 22: 161–80. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/4259/425942158006.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Taylor, J. Edward. 2006. International Migration and Economic Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/unpd_om_200606_p09_taylor.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security. 2022. DHS Announces New Migration Control Process for Venezuelans. Available online: https://www.dhs.gov/archive/news/2022/10/12/dhs-announces-new-migration-enforcement-process-venezuelans (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Van Hear, Nicholas. 1998. New Diasporas: The Mass Exodus, Dispersal and Regrouping of Migrant Communities. London: UCL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hear, Nicholas, Oliver Bakewell, and Katy Long. 2018. Push-pull plus: Reconsidering the drivers of migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44: 927–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, Tara. 2021. Migration, mobility and the making of a global Europe. Contemporary European History 31: 142–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorlu, Aslan, and Wouter Van Gent. 2023. Economic assimilation of the “Third Generation”: An Intergenerational mobility perspective. International Migration Review 58: 734–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.