Abstract

The study aimed to interpret how citizen participation mechanisms contribute to rebuilding public trust in the Peruvian state, considering how citizens evaluate transparency, institutional legitimacy, and state responsiveness. A qualitative approach with an explanatory-interpretive scope was developed, based on a phenomenological-hermeneutic method, and included 4124 participants selected through purposive sampling, whose semi-structured interviews were analyzed through open and axial coding in Atlas.ti v23. The results showed that public trust is mainly shaped by the perceived consistency between institutional discourse and action, clarity of information, accessibility of services, ethical conduct of officials, and responsiveness to social demands. Likewise, it was identified that citizen participation is valued positively when it produces verifiable results, feedback, and continuity, while it is perceived as symbolic when it does not influence decision-making, there is one-way communication, or bureaucratic and technological barriers persist. In conclusion, the study shows that public trust is rebuilt when institutions guarantee transparency, clear communication, and participatory mechanisms with real impact, shaping governance oriented toward openness, shared responsibility, and democratic legitimacy.

1. Introduction

Citizen participation has become an essential component in strengthening democratic governance and rebuilding public trust in state institutions. Its relevance lies in expanding spaces for deliberation, promoting social co-responsibility, and lending legitimacy to public decisions through open and verifiable processes. Recent reports from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP 2024) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD 2023) indicate that countries with strong participatory mechanisms have higher levels of transparency, social control, and community cohesion, consolidating citizens as active actors in oversight and co-management (Roncancio et al. 2025).

The relationship between participation and trust has been the subject of extensive debate since the 1990s. Fischer (1993, 2000), Fishkin (1991, 2009), and Fung (2006) analyzed how deliberative mechanisms can rebuild democratic legitimacy after the deterioration of the welfare state. Sharma et al. (2024) argued that participation became a fundamental axis for restoring institutional credibility in the face of the impacts of globalization and the erosion of traditional representative mechanisms. In parallel, the World Bank introduced the concept of “good governance,” linking transparency, accountability, and participation as drivers for regenerating public trust. This historical overview shows that the theoretical field is broad and mature, making it necessary to clearly define the specific contribution of the present study. In this vein, the recent review by Zhou et al. (2025) highlights that, despite the accumulated development, there is still a need to understand how citizens interpret participation and how those interpretations translate into sustained legitimacy.

Strengthening participation does not depend solely on regulatory frameworks, but also on the institutional capacity to ensure inclusive processes with effective impact. Trust is rebuilt when citizens perceive that their contributions influence public action. De Braal et al. (2025) explain that participation acts as a collaborative mechanism that legitimizes the exercise of power, while Llano-Aristizábal and Peña (2025) highlight that such interaction promotes more open and representative institutions. In this vein, the literature states that contemporary democracies require stable mechanisms for dialog, recognition, and co-responsibility to regenerate the links between citizens and the state (Takakusa and Kinoshita 2024).

This challenge is particularly visible in Latin America, where inequality, corruption, and institutional weakness have affected government legitimacy (Suárez Elías and Noboa 2024). In the case of Peru, political instability, recurring changes in leadership, corruption scandals, and urban–rural territorial gaps have eroded political representation and limited the effectiveness of participatory mechanisms. According to ECLAC (2023), rebuilding trust depends on the state’s ability to guarantee transparent, verifiable, and inclusive participatory processes, which makes the Peruvian case a relevant scenario for studying the dynamics between participation and legitimacy.

The literature has also shown that different participatory designs produce different effects on public trust. Fung (2006) and Bozkus Kahyaoglu et al. (2025) distinguish between participatory budgeting, citizen juries, deliberative forums, public consultations, and hybrid multi-stakeholder mechanisms, noting that each generates specific dynamics of legitimation. More recently, hybrid arenas that integrate state actors, technicians, civil organizations, and private sectors have transformed traditional models of participation, expanding the forms of public advocacy (Mo and Beh 2025; Mora-Perez et al. 2024). Recognizing this diversity allows for a more accurate interpretation of how different mechanisms can influence the rebuilding of trust.

Based on this framework, the present study aims to interpret how citizen participation mechanisms contribute to rebuilding public trust in the Peruvian state. To this end, three specific objectives are defined: (i) to examine how citizens interpret participation mechanisms and how these experiences shape their perceptions of transparency, proximity, and legitimacy; (ii) to analyze the political, social, and administrative factors that condition the effectiveness of participation in building trust; and (iii) to interpret the narratives of social and governmental actors on the real impact of participatory spaces on decision-making processes. In line with these objectives, the study adopts an interpretive approach and proposes two hypotheses for analysis: H1: Citizen participation mechanisms strengthen public trust by transforming citizens’ perceptions of institutional performance. H2: The legitimacy of performance, understood as transparency, procedural openness, and responsiveness, is the main mechanism through which participation influences the rebuilding of trust. These hypotheses guide the interpretation of the qualitative results and define the study’s contribution to the contemporary debate on democratic governance.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Historical Evolution of the Debate

The debate on citizen participation and public trust dates back to the late 20th century, when the need arose to rebuild democratic legitimacy in the face of the deterioration of the welfare state and the advance of globalization. During this period, Fischer (1993, 2000); Fishkin (1991, 2009); Fung (2006), and Cohen and Rogers (1992) developed the foundations of participatory governance, emphasizing that the direct inclusion of citizens was essential to restoring the damaged credibility of public institutions. At the same time, the World Bank (1997), under the paradigm of “good governance,” integrated transparency, social control, and institutional openness as pillars for sustaining democratic trust. This theoretical basis allowed for the consolidation of a broad field of research that analyzed the democratic value of participation, its effects on legitimacy, and the normative and operational difficulties associated with its implementation. In a systematic update, Zhang and Bai (2024) highlighted the conceptual saturation of the field and pointed out the need to precisely delimit the empirical problems linked to participation and public trust.

In the following decades, this debate diversified into the empirical analysis of participatory modalities and their effects on institutional trust. Recent studies have shown that the perception of consistency between institutional performance and public commitments increases trust (Mu et al. 2025), and that participation linked to community experiences generates greater democratic cohesion (Bruno and Barreiro 2021). Legitimacy has also been associated with perceptions of government integrity (Poertner and Zhang 2024), citizenship norms (Beesley and Hawkins 2022), and social recognition in inclusive processes (Peresada et al. 2022). Complementarily, Ma et al. (2023) showed that civic education strengthens the capacity for political advocacy and understanding of the role of citizens in democratic governance.

More recently, comparative literature has expanded the analysis to include psychological, educational, and community dimensions. Research on youth participation links civic self-efficacy with the willingness to take on public responsibilities (Vejseli and Kamberi 2021), while Choi et al. (2022) and Grobshäuser and Weißeno (2021) show that trust in government is shaped by the interaction between transparency, citizen evaluation, and perceptions of institutional justice. Other studies point out that participatory modalities interact with intercultural and socio-economic factors that shape democratic legitimacy (Fernández de Castro and Díaz-García 2021).

2.2. Citizen Participation and Trust in Governance

The relationship between citizen participation and trust in governance has been understood as an interdependent process that articulates perceptions of institutional performance, state openness, and direct interaction between citizens and authorities. Jiménez and Valdés (2022) argue that public trust is strengthened when citizens perceive justice, transparency, and efficiency in government management, while Essomba et al. (2023) demonstrate that participation increases institutional credibility when accompanied by positive evaluations of local performance. Oser (2022) adds that participation influences citizens’ willingness to collaborate with the public sector when there is consistency between institutional commitments and observable results. Along the same lines, Mühleck and Hadjar (2023) explain that access to information on administrative results reduces uncertainty and strengthens trust.

At the regional level, Ortiz and Santos-Jaén (2021) highlight that participation and accountability act as complementary mechanisms that improve efficiency and legitimacy, shaping a form of governance in which citizens take an active role in state oversight. Across the board, Faggiani (2022) argues that citizen satisfaction increases when participatory processes are structurally integrated into decision-making cycles.

Other studies highlight that participation operates not only as a political mechanism but also as a social process that channels perceptions of justice, equity, and mutual recognition. Lo Prete (2024) shows that continuous interaction with authorities reduces the psychological distance from the state, generating higher levels of trust when institutional performance is perceived as consistent. For their part, Baggetta and Bello-Gomez (2025) argue that trust deteriorates when governments maintain opaque practices or limit communication channels. Fabiano (2023) emphasizes that ethical integrity and the moral climate of public administration directly influence perceptions of trustworthiness, while Bonotti and Willoughby (2022) point out that incorporating criteria of distributive equity and informational transparency strengthens state credibility. These contributions demonstrate that citizen participation is a structural determinant of public trust, as it activates evaluation mechanisms, reduces the opacity of power, and consolidates cooperation between society and institutions.

2.3. Designs and Modalities of Participation

The research argues that the effects of participation depend on the institutional architecture of the process and on citizens’ capacities to interact with it. Fung (2006) established an analytical framework that differentiates designs according to three dimensions: (i) selection mechanism, (ii) form of communication and (iii) degree of influence. This allows us to identify modalities with different effects on legitimacy and trust. Consultative designs generate information for authorities but have limited impact on trust due to their low incidence; deliberative designs, according to Fishkin (2009), strengthen trust when they guarantee political equality, informed discussion, and procedural transparency. In contrast, the empowered models described by Cohen and Rogers (1992) offer citizens real decision-making power, which increases the perception of state responsiveness, although they require high levels of institutionalization.

From a normative perspective, Fischer (2000) argued that the evaluation of designs should not focus solely on their technical efficiency, but also on their ability to integrate citizen knowledge, minimize power asymmetries, and produce deliberative justice. These criteria are linked to the World Bank (1997) approach to good governance, where participation is conceived as a structural mechanism to consolidate transparency, reduce discretion, and sustain public credibility.

Recent studies extend this field to hybrid and digital formats. Watfa and Ali (2025) demonstrated that digital platforms generate innovative combinations of consultation, collaboration, and citizen monitoring, diversifying the points of contact between citizens and the state. Kwan (2022) pointed out that these designs only acquire legitimacy when they incorporate verifiable feedback and traceability of citizen contributions.

Likewise, Myoung and Liou (2022) showed that contemporary deliberative models strengthen civic learning and the perception of procedural justice. Inclusive and transformative designs, such as those documented by Pramuditha et al. (2024) and Hutahaean et al. (2023), increase legitimacy by integrating intercultural and community dynamics that promote social cohesion. Hybrid, digital, and face-to-face modalities, such as those analyzed by Li and Shang (2023) and Van Nguyen et al. (2025), broaden the participation of specific groups, particularly young people, while Nawafleh and Khasawneh (2024) show that associative spaces operate as indirect participation by generating collective practices based on co-responsibility.

Based on the above, the literature reveals that there is no single participatory effect, but rather differentiated results according to (a) the level of actual impact, (b) the type of interaction (informative, consultative, deliberative, decision-making), (c) the degree of social inclusion, and (d) the institutional capacity to respond to demands.

This diversity requires studying how citizens interpret each modality and why the same mechanisms produce different effects on the perception of trust.

2.4. Factors Influencing Trust

Public trust is shaped by a set of citizen assessments of impartiality, performance, procedural justice, and institutional transparency. Anuradha and Pathranarakul (2023) explained that trust emerges when state action is perceived as consistent, verifiable, and oriented toward collective well-being. Li and Xue (2021) expanded on this perspective by showing that administrative efficiency, when it coincides with the commitments made by the authorities, reinforces institutional credibility by reducing uncertainty regarding the functioning of the state. From a political perspective, Li (2021) argued that institutional openness and citizen inclusion are crucial for sustaining trust, particularly when legitimacy is under strain. In line with this, Kala et al. (2024) demonstrated that participation strengthens credibility when it is linked to positive assessments of local performance. This evidence suggests that trust does not depend solely on technical performance, but on how citizens interpret their relationship with the state (Rodriguez-Saavedra et al. 2025).

On a symbolic level, Gupta (2021) identified that procedural justice and fairness in government decisions act as emotional anchors of trust, while Verástegui et al. (2025) showed that a lack of openness and the persistence of closed hierarchical structures erode public credibility. From an interpretive perspective, Abdulkareem and Oladimeji (2024) explained that trust is constituted at the intersection of distributive justice, service effectiveness, and institutional accountability, converging in a comprehensive perception of the integrity of the state. Haesevoets et al. (2024) added that civic self-efficacy influences the willingness to trust, as it generates positive expectations about one’s own ability to influence. Institutional contributions reinforce these findings. Healy (2023) demonstrated that citizen monitoring mechanisms reduce discretion and shorten the psychological distance between citizens and the state. He and Ma (2021) showed that lack of information and limited institutional response undermine credibility, while Abdi and Rahman (2025) highlighted the importance of transparency and continuous interaction in sustaining open governance systems.

2.5. Critical Synthesis and Research Gap

The classical literature has extensively established the link between citizen participation and democratic legitimacy. Fischer (1993, 2000), Fishkin (1991, 2009), and Fung (2006) explained that deliberative mechanisms emerged in response to the loss of institutional credibility, while Cohen and Rogers (1992) emphasized that empowered participation sought to rebuild public trust. The World Bank’s (1997) approach to good governance integrated these principles, consolidating transparency, social control, and state openness as pillars of legitimacy. However, Mahmud (2021) pointed out that the field is conceptually saturated and requires new definitions that allow us to understand how trust is configured in current contexts.

Recent evidence has shown that trust depends on perceptions of performance, institutional coherence, and participatory openness (Ye et al. 2024; Zeng et al. 2025). Other studies, such as those by Brunner et al. (2024) and Abdi (2023), emphasize that the stable integration of participatory mechanisms reinforces citizen satisfaction and consolidates democratic legitimacy. Likewise, Gao and Sun (2025) show that continuous interaction reduces the psychological distance between citizens and the state.

However, despite these advances, a central limitation remains: there is insufficient understanding of how citizens interpret their direct experience within different participatory designs or why similar modalities generate different effects on public trust. Nevertheless, the literature still does not explain why similar participatory designs generate divergent effects among different social or territorial groups, which reinforces the need for an interpretive analysis focused on citizen perceptions (Rodriguez-Saavedra et al. 2025). This theoretical gap justifies the interpretive approach of the present study, which aims to analyze participation as a process through which people evaluate the coherence, openness, and responsiveness of the state, thus shaping their perception of democratic trust.

2.6. Relevance of the Peruvian Case

The Peruvian case provides a unique setting for studying the relationship between citizen participation and institutional trust due to the political instability, corruption scandals, and crisis of representation that have marked the country over the last two decades.

At the regional level, comparative studies have shown that Latin American states face persistent deficits in transparency, equity, and access to participatory mechanisms. ECLAC (2023), UNDP (2024), and OECD (2023) agree that countries with lower public trust are those where accountability is fragmented, and participatory processes lack continuity. This scenario places Peru within a regional pattern where citizens demand mechanisms that reduce institutional uncertainty and produce verifiable results.

Peru also has a high degree of sociocultural and territorial diversity, which complicates the relationship between participation and trust. Lee (2024) highlights that culturally heterogeneous environments require intercultural participatory mechanisms, while Dong and Kübler (2021) show that legitimacy increases when historically marginalized sectors are included. Ati et al. (2024) add that active citizenship is strengthened when there are stable interactions between institutions and community actors, a critical aspect in a country where trust in the state fluctuates continuously (Rodriguez Saavedra et al. 2025b).

Therefore, the availability of national microdata allows us to examine how citizens interpret their experience with participatory spaces in a context of political volatility. Ratnasari et al. (2022) point out that trust depends on consistency between government performance and commitment, and Lee (2021) shows that verifiable information reduces the psychological distance between the state and society. Based on the above, Peru offers an appropriate “institutional laboratory” for understanding the effects of participation on public trust in contexts of high uncertainty and unstable legitimacy.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Strategy and Design

The study adopted a qualitative approach, aimed at interpreting the meanings that citizens attribute to political participation, state transparency, and trust in public institutions. It was applied in nature, as it sought to generate useful knowledge for strengthening participatory processes (Rodriguez Saavedra et al. 2025a). The scope was explanatory-interpretative, focused on understanding how citizens’ perceptions of institutional legitimacy are shaped. A phenomenological-hermeneutic method was used, which is appropriate for studying subjective experiences expressed by participants in a complex social environment (Richey 2023). This approach made it possible to identify patterns of meaning associated with the formation of public trust, the evaluation of state performance, and the interaction between citizens and institutions.

3.2. Participants

The study included 4124 participants residing in Peru, selected through purposive sampling, with the aim of incorporating a diversity of experiences and perceptions related to citizen participation and trust in public institutions. The sample consisted of citizens (55%) and public officials (45%), aged between 21 and 68, which allowed for intergenerational perspectives and perspectives from different areas of interaction with the state.

The call for participants was made through an open invitation distributed via digital platforms, including LinkedIn, university networks, academic groups, and a unique access link disseminated through institutional contacts. This mechanism ensured voluntary participation, avoided duplication, and broadened the scope to include profiles directly or indirectly linked to public affairs. Table 1 below summarizes the main sociodemographic characteristics of the participants included in the study.

Table 1.

General characteristics of study participants.

Table 1 shows the distribution of participants according to gender, age, citizenship or professional status, and educational level. The inclusion of these variables allows us to contextualize the plurality of profiles present in the research and provides relevant elements for understanding the diversity of experiences and perceptions analyzed in the qualitative study.

3.3. Instruments

A semi-structured interview guide was used to collect information, designed to explore the meanings, perceptions, and experiences that participants attribute to citizen participation, government transparency, and trust in state institutions. This instrument allowed for open-ended questions organized around a clear theoretical structure, while also providing flexibility to delve deeper into the narratives (Bruun 2024).

Due to the high number of participants, the guide consisted of 15 open-ended questions distributed across conceptual dimensions previously defined based on the literature on institutional legitimacy, citizen participation, governance, public communication, and trust. These dimensions were established prior to the fieldwork to ensure interpretive consistency and avoid analytical dispersion. The instrument underwent content validation by five specialists in public policy, democratic governance, and sociology, who evaluated the clarity, relevance, and internal consistency of each item. The assessment resulted in an Aiken V coefficient of 0.912, an indicator that supports the adequacy and conceptual soundness of the guide.

All interviews were conducted with digital informed consent, were fully recorded, and were subsequently transcribed by the team of authors for qualitative analysis. Atlas.ti version 23 was used for processing, following an open and axial coding procedure that allowed for the identification of units of meaning, their grouping into categories, and the establishment of interpretive connections between the analytical axes of the study. Table 2 below shows the correspondence between the theoretical construction and the empirical exploration.

Table 2.

Subcategories, qualitative indicators, and semi-structured questions.

Table 2 presented the interpretive categories, which were defined based on the literature on participatory democracy, institutional legitimacy, and public trust. The questions were organized to explore the mechanisms by which citizens evaluate transparency, participation, and trust in institutions.

3.4. Ethics and Procedure

The study complied with the ethical principles of confidentiality, informed consent, and respect for the autonomy of participants. Before beginning data collection, each person digitally accepted a consent form explaining the study’s objectives, the use of the data, and their right to withdraw at any time without consequences. To ensure anonymity, each participant was assigned an alphanumeric code that prevented any possibility of personal identification (Vento 2024). All data collection was carried out virtually in secure digital environments, avoiding unnecessary risks or exposure.

The procedure was carried out in three phases. In the first phase, the call for participation was disseminated and compliance with the inclusion criteria was verified (Faustini 2025). In the second phase, a semi-structured interview guide in open digital format was applied, ensuring uniformity in its application and consistency in the analytical categories. In the third phase, the responses were transcribed in full and analyzed in Atlas.ti software, applying theoretical saturation criteria to determine the end of the analytical process. The entire study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of social science research and following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

4. Results

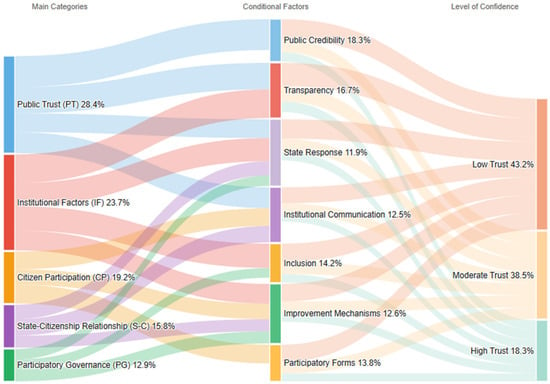

The qualitative analysis was developed from semi-structured interviews processed and coded in Atlas.ti v23 software, applying open and axial coding techniques, thematic content analysis, and interpretive triangulation. These tools made it possible to identify discursive patterns and shared meanings about trust, participation, and governance. A Sankey diagram was also used to visually represent the flows and interconnections between the emerging categories. The results presented below reflect the most representative perceptions that explain the interaction between citizens and public institutions.

4.1. Results of Objective 1: Interpret Citizens’ Perceptions of Levels of Trust and Credibility in Public Institutions

The qualitative analysis showed that public trust was mainly structured around three elements: transparency, consistency in management, and the state’s responsiveness. Respondents associated credibility with verifiable experiences, clear information, fulfillment of commitments, and timely attention, while opacity, bureaucracy, and institutional distance were described as factors that undermine public legitimacy. Differences between social groups were also identified; citizens prioritized proximity and speed of resolution, while officials emphasized administrative efficiency and procedural compliance. At the territorial level, local institutions were perceived as more accessible and reliable than national entities, which were characterized by their remoteness and difficulty of contact. Table 3 below summarizes the emerging categories associated with these perceptions.

Table 3.

Emerging categories related to citizen trust in public institutions.

The results summarized in Table 3 show that public trust is a dynamic process based on the relationship between institutional performance and citizen expectations. Transparency, consistency, and responsiveness emerged as the key criteria by which the population evaluates the credibility of the state. The micro-quotes reveal a constant demand for clear information, effective compliance, and timely attention, while institutional presence at the local level helps reinforce the perception of accessibility and proximity. These categories allow us to understand that public trust is a key indicator of the state–society relationship and a fundamental component for rebuilding institutional legitimacy.

4.2. Results of Objective 2: Analyze the Political, Social, and Administrative Factors That Condition the Capacity of Participation to Generate Public Trust

The qualitative analysis showed that citizen participation is interpreted as a process influenced by structural conditions that determine its impact on public trust. Interviewees pointed out that participatory effectiveness depends on transparency in management, ethical conduct by officials, the quality of consultation spaces, and the clarity of administrative procedures. The perception of exclusion increases when participation is considered symbolic, bureaucratic, or without real impact on state decisions. In addition, unequal access to information and digital tools, together with institutional slowness and lack of follow-up, reinforces the idea that citizens have few opportunities to influence public management. Table 4 below summarizes the emerging categories related to these conditioning factors.

Table 4.

Factors influencing public confidence.

The information presented in Table 4 shows that the ability of participation to generate trust depends on a network of factors that operate simultaneously in the political, social, and administrative spheres. Transparency and institutional ethics are consolidated as basic requirements for citizens to perceive participation as a real process and not as a formality. Information inequality and technological limitations introduce barriers that prevent full inclusion, while administrative slowness and lack of follow-up generate frustration and demotivation among citizens. Micro-quotes show that the legitimacy of the state is weakened when participatory spaces lack impact, clarity, and continuity. Taken together, these findings make it clear that participation only contributes to strengthening public trust when it takes place in open, accountable, and efficient institutional conditions.

4.3. Results of Objective 3: Interpreting the Narratives of Social and Governmental Actors on the Actual Effectiveness of Participatory Spaces in Public Decision-Making

The qualitative analysis showed that participatory spaces are formally recognized by citizens, but their actual effectiveness in decision-making is perceived as limited. The narratives showed that these mechanisms function mainly as consultative processes that rarely produce verifiable changes, creating a sense of distance between the state and society. Participants pointed out that the lack of continuity, the absence of feedback, and the limited incorporation of citizen contributions diminish the legitimacy of these spaces. Likewise, unilateral communication, bureaucracy, and lack of follow-up reinforced the perception that participation operates more as an administrative procedure than as a deliberative process. However, positive experiences emerged at the local level, where direct contact with authorities allowed for concrete improvements and greater institutional commitment to listening to citizens. Table 5 below summarizes the emerging categories related to the actual effectiveness of participatory spaces.

Table 5.

Factors affecting the effectiveness of participatory spaces.

Table 5 shows that the effectiveness of participatory mechanisms depends on the state’s capacity to generate visible results and maintain two-way communication processes. Perceptions of symbolic participation, lack of follow-up, and one-way communication explain why citizens believe that their contributions do not have a real influence on public decisions. Positive experiences in local governments show that effectiveness increases when there is institutional proximity, timely responses, and verifiable actions. The findings indicate that participation is valued not for its formal existence, but for its ability to influence, produce change, and maintain consistency between what is deliberated and what is executed.

4.4. Interpretive Representation of Qualitative Findings

The Sankey diagram visually summarizes the qualitative findings of the three specific objectives and allows us to observe how the central categories of the analysis, such as public trust, institutional factors, citizen participation, the state–citizen relationship, and participatory governance, are linked to the conditional factors identified in the open and axial coding process. This representation facilitates understanding of the intensity and directionality of the connections interpreted in the narratives. Figure 1 below presents the interpretive representation constructed from the qualitative processing of the data.

Figure 1.

Interpretive representation of citizen participation and trust in the state.

Figure 1 shows that public trust is shaped by the interaction between credibility, transparency, and state responsiveness. Low levels of trust are mainly linked to experiences of opacity, top-down communication, and poor response times. Moderate trust is associated with listening practices, availability of information, and some verifiable results. Finally, high trust is related to contexts in which participants perceive institutional coherence, accountability, and effective participatory mechanisms.

This representation reaffirms that participatory governance acts as an integrating axis between citizen perceptions and the reconstruction of public trust. The articulation between transparency, credibility, inclusion, institutional improvements, and participatory forms shapes a dynamic process through which citizens evaluate the legitimacy of the state and the coherence between its commitments and actions.

5. Discussion

The findings showed that public trust is built on the perceived consistency between institutional commitments and the observable results of government management. Participants interpreted transparency, credibility, and responsiveness as fundamental elements for sustaining institutional legitimacy. This interpretation is in line with the classic literature that, since the 1990s, has explained that democratic trust depends on visible, fair, and procedurally legitimate processes. Along these lines, Fischer (1993, 2000) and Fishkin (1991, 2009) argued that trust is strengthened when citizens perceive openness and clarity in policy-making processes. Similarly, Fung (2006) emphasized that participatory mechanisms only generate trust when they have a real impact on decision-making. Recent evidence confirms these ideas. Abasilim and Adekunle (2024) demonstrated that impartiality in management strengthens citizen trust, while Gale et al. (2025) pointed out that accountability increases the perception of democratic reliability. Similarly, Tzagkarakis and Kritas (2023) reinforced that procedural legitimacy is consolidated when transparency, openness, and inclusion are visible to citizens.

Political, social, and institutional factors also conditioned citizens’ interpretations of trust. The narratives showed that bureaucratic distance, lack of information accessibility, and insufficient public ethics practices create a structural climate of mistrust. This finding coincides with Aldeguer and Antón-Mellón (2025), who argue that corruption and opacity undermine state credibility, and with Feng and Shao (2023), who assert that institutional clarity reinforces perceived legitimacy. Recent research also highlights the role of government digitization. Yang (2021) showed that interactive communication reduces information asymmetry, while Milkoreit (2025) showed that accessible digital channels strengthen the perception of integrity. Richey (2023) identified that satisfaction with digital services increases the perception of institutional honesty, thus reinforcing the link between communication, efficiency, and trust.

On the other hand, citizen experiences revealed that participatory spaces, although present, are perceived as having little impact and being mostly formal. This result coincides with the tradition of Cohen and Rogers (1992), who explained that participation only contributes to public trust when it generates verifiable effects and produces shared decisions. Contemporary theories support this approach. He and Ma (2021) found that active participation strengthens democratic identity, while Abdi and Rahman (2025) argued that political inclusion allows for a more genuine representation of collective demands. Mahmud (2021) and Ye et al. (2024) demonstrated that local cooperation increases institutional legitimacy, reinforcing the perception of the public system’s effectiveness. In addition, Zeng et al. (2025) and Brunner et al. (2024) pointed out that civic knowledge promotes critical and active citizenship, which explains why participation with monitoring and feedback strengthens democratic trust. According to Abdi (2023) and Gao and Sun (2025), new digital forms of participation expand channels of expression and reduce barriers to involvement.

Likewise, it was observed that the relationship between citizens and the state continues to be mediated by predominantly vertical communication, characterized by one-way information and little feedback. This communication pattern weakens the institutional bond and sustains the perception of state distance. The literature confirms this trend. Lee (2024) demonstrated that the use of clear and emotionally appropriate language improves the perception of government commitment, while Ati et al. (2024) pointed out that effective management of digital networks reduces the psychological distance between citizens and authorities. Ratnasari et al. (2022) showed that the dissemination of verifiable information increases public satisfaction. Similarly, Vento (2024) and Gale et al. (2025) showed that understanding institutional outcomes and a sense of local belonging encourage civic collaboration. Complementarily, Aldeguer and Antón-Mellón (2025) and Lai and Beh (2025) explained that the incorporation of technological tools promotes direct participation and transparency, consolidating more responsive and cooperative governance practices.

Based on the above, the results allow us to affirm that public trust is rebuilt when there is consistency between institutional discourse and action, when processes are transparent, and when participatory spaces offer clear impact and results. This study confirms the validity of the classic approaches of Fischer (1993, 2000), Fishkin (1991, 2009), and Fung (2006), showing that democratic trust does not depend solely on formal mechanisms of participation, but on the real capacity of institutions to communicate, respond, and demonstrate openness. The analysis shows that institutional legitimacy emerges from the interaction between transparency, public ethics, meaningful participation, and accessible communication, forming an interpretive system where citizen perceptions are articulated with government practices that sustain or erode collective trust.

Future Research and Recommendations

Future research should delve deeper into the analysis of participatory governance by comparing how different institutional models operate in the Peruvian context, at the local, regional, and national levels. It is necessary to examine how the country’s historical trajectories of participation, the predominance of municipal experiences, and the asymmetries between urban and rural areas influence the configuration of citizen trust. It would also be relevant to explore the relationship between digital innovation and state credibility, analyzing the role of online platforms, citizen interaction tools, and government communication strategies to improve transparency and institutional responsiveness.

It is recommended to use mixed methodologies that integrate qualitative and quantitative evidence, allowing for a more complete understanding of perceptions of legitimacy, administrative performance, and institutional accessibility. Future lines of research could also examine the role of civic education in the formation of critical and participatory citizens, as well as the effect of accountability policies on rebuilding public trust. Strengthening these areas will allow for a more accurate understanding of the mechanisms that link participation, communication, and trust within specific geo-institutional contexts.

6. Conclusions

The findings showed that public trust is based, first and foremost, on the correspondence between institutional discourse and the concrete actions that citizens can observe in their daily lives. In this context, local institutions stood out for generating greater credibility due to their accessibility, responsiveness, and direct presence in the territory. In contrast, central levels were perceived as more distant, bureaucratic, and less transparent, which consistently weakened citizen assessment. This shows that trust is consolidated when there is clarity of information, fulfillment of commitments, and tangible evidence of state performance.

Second, it was confirmed that political, social, and administrative factors have a decisive influence on the strength of the relationship between the state and its citizens. The lack of accountability, limited inclusion in decision-making processes, and unclear institutional practices led to a progressive erosion of trust. At the same time, experiences that incorporated functional responsibility, public ethics, and openness to dialogue showed that these elements can reverse negative perceptions and strengthen legitimacy. Thus, the link between institutions and society depends as much on the quality of management as on the overall behavior of those who exercise public functions.

Third, the analysis confirmed that citizen participation continues to be predominantly formal, fragmented, and with little capacity to influence decision-making. However, when spaces for participation offered continuity, feedback, and effective mechanisms for channeling proposals, significant improvements in trust and a sense of institutional belonging were observed. This reveals that participation only acquires transformative value when it is accompanied by follow-up, a willingness to listen, and visible results that reflect the real incorporation of citizen contributions.

Likewise, it was identified that institutional communication is still unidirectional, with insufficient response times and a lack of clarity in the information provided. These conditions contribute to perceptions of disinterest, distance, and administrative weakness. However, significant progress was observed in the use of digital tools that reduce the gap between authorities and citizens, favoring more direct, accessible, and timely interaction.

The results allow us to conclude that rebuilding public trust requires a gradual but determined shift toward a participatory governance model based on transparency, clear communication, and genuine shared responsibility in decision-making. Trust is strengthened when institutional management acts consistently, when authorities respond clearly, and when citizens participate in processes where their voices are effectively taken into account.

This involves consolidating structures that guarantee accessibility, feedback mechanisms, and management that is consistently oriented toward the common interest, thus shaping a more solid, legitimate, and balanced relationship between society and the state.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.O.R.-S. and R.E.G.L.; methodology, M.O.R.-S., R.E.G.L. and R.P.V.; software, R.E.G.L., H.E.A.G. and A.B.D.P.; validation, M.O.R.-S., R.E.G.L., R.P.V., O.A.A. and I.C.G.; formal analysis, M.O.R.-S., R.E.G.L. and I.C.G.; research, M.O.R.-S., R.E.G.L., R.P.V., H.E.A.G., A.B.D.P., O.A.A., J.A.E.P., R.A.P.G., I.C.G., L.M.C.A., A.V.M.G. and J.W.M.L.; resources, L.M.C.A., A.V.M.G. and O.A.A.; data curation, J.A.E.P., R.A.P.G. and H.E.A.G.; writing—original draft, M.O.R.-S.; writing—review and editing, M.O.R.-S., R.E.G.L., R.P.V., J.A.E.P., R.A.P.G., I.C.G. and J.W.M.L.; visualization, R.E.G.L., A.B.D.P. and H.E.A.G.; supervision, M.O.R.-S., R.E.G.L. and L.M.C.A.; project management, M.O.R.-S. and L.M.C.A.; funding acquisition, M.O.R.-S., L.M.C.A., A.V.M.G. and R.E.G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been funded by Ricardo Enrique Grundy López.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because, in accordance with the Regulations of the Research Ethics Committee of the Technological University of Peru (Code INV-RG004, Version 05, 2024), it was not necessary to request ethical approval. In accordance with Articles 3, 5, and 12 of the aforementioned regulations, the research did not involve vulnerable populations, minors, or the handling of clinical or sensitive data, and is therefore exempt from review by an ethics committee. In addition, all participants were adults who signed their informed consent, guaranteeing confidentiality, anonymity, and respect for the ethical principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised in 2013). Document available at: https://www.utp.edu.pe/web/sites/default/files/INV_-_RG004_Reglamento_del_Comite_de_Etica_en_Investigacion_V05.pdf, accessed on 30 November 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. All subjects were adults and agreed to participate voluntarily, signing the informed consent form, which guaranteed confidentiality, anonymity, and respect for the ethical principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised in 2013).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results are available upon request from the corresponding author. An anonymized dataset, along with the variable dictionary and R scripts, will be provided to anyone who requests it for academic purposes and agrees to a confidentiality agreement, subject to applicable ethical requirements.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the institutions that provided administrative and technical support during the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abasilim, Ugochukwu, and Ahmed Oluwatobi Adekunle. 2024. Digital Media and Governance Research: Empirical Evidence from Public Administration and Political Science Scholars. Ianna Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 6: 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, Abdi Nur Mohamud, and Nor Azlida Rahman. 2025. Public trust in local government in Somalia: Effect of citizen participation and perceived local government performance. Cogent Social Sciences 11: 2441405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, Nur Mohamud. 2023. The mediating role of perceptions of municipal government performance on the relationship between good governance and citizens’ trust in municipal government. Global Public Policy and Governance 3: 309–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkareem, Azeezat Kudirat, and Kehinde Ayobami Oladimeji. 2024. Cultivating the digital citizen: Trust, digital literacy and e-government adoption. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy 18: 270–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldeguer, Bernabé, and Juan Antón-Mellón. 2025. Intelligence Theory and Democratic Governance: An Epistemological Approach from Political Science. International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence 38: 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuradha, Pirisudham Indikathe, and Piyapong Pathranarakul. 2023. Can governments rebuild the trust of their citizens through e-government? The mediating effect of good governance. International Journal of Electronic Governance 14: 458–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ati, Sanjay Satpathy, and Surbhi Saxena. 2024. Perceived public service performance, trust in the government, and citizens’ willingness to participate: Evidence from water governance in Visakhapatnam, India. Water Policy 26: 618–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggetta, Matthew, and Ricardo Bello-Gomez. 2025. Can You Sing Your Way to Good Citizenship?: Recreational Association Structures and Member Political Participation. Social Problems 72: 964–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beesley, Carol, and Darren Hawkins. 2022. Corruption, institutional trust and political engagement in Peru. World Development 151: 105743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonotti, Matteo, and Luke Willoughby. 2022. Citizenship, language tests, and political participation. Nations and Nationalism 28: 449–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkus Kahyaoglu, Seda, Rasul Abdieva, and Dinara Baigonushova. 2025. Citizen Perception and Participation in Local Government in Post-Soviet Countries: Case of Kyrgyzstan. Journal of Eurasian Studies 16: 261–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, Eric, Yong Kim, Mark Robbins, and Bill Simonsen. 2024. The impact of performance information on citizen perceptions of school district efficiency, trust in government, and support for taxes. Public Budgeting and Finance 44: 6–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, Debora, and Alfredo Barreiro. 2021. Cognitive Polyphasia, Social Representations and Political Participation in Adolescents. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science 55: 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruun, Mikkel Hojer. 2024. Algorithmic Governance, Public Participation and Trust Citizen–State Relations in a Smart City Project; La gouvernance algorithmique, la participation publique, et la confiance: Les rapports entre les citoyens et l’état dans un projet de ville connectée. Social Anthropology 32: 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Young Kyoung Hwang, and Chin Lee. 2022. The Effects of Participation in Lifelong Education, Political Efficacy, and Citizenship on Quality of Life: The Moderated Mediation Model of Growth Mindset. Res Militaris 12: 7145–58. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Joshua, and Joel Rogers. 1992. Secondary Associations and Democratic Governance. Politics & Society 20: 393–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Braal, Peter, Stijn Oosterlynck, Michael Leyshon, and Catherine Leyshon. 2025. Opening the black box of the municipal government: Exploring the lived experiences of local public servants with citizen participation and decentralisation in The Netherlands. Journal of Social Policy 8: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Li, and Daniel Kübler. 2021. Government performance, political trust, and citizen subjective well-being: Evidence from rural China. Global Public Policy and Governance 1: 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECLAC. 2023. Social Panorama of Latin America and the Caribbean, 2023. United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Available online: https://www.cepal.org/en/publications/80859-social-panorama-latin-america-and-caribbean-2024-challenges-non-contributory (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Essomba, Miguel Àngel, Marta Nadeu, and Anna Tarrés. 2023. Youth Democratic Political Identity and Disaffection: Active Citizenship and Participation to Counteract Populism and Polarization in Barcelona. Societies 13: 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiano, Davide Luca. 2023. Representative Democracy Crisis, E-Political Participation and Civil Society Awareness: The Digital Citizenship Challenges and the Necessary Conditions for its Introduction; Crisi dello Stato democratico rappresentativo, partecipazione politica elettronica e consapevolezza della società civile. Federalismi.it 2023: 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Faggiani, Valentino. 2022. Substantive citizenship and political participation in eu: Limits of the system and the need of a closer inclusion; citoyenneté substantielle et droits de participation politique dans l’ue: Limites du système et nécessité d’une plus grande inclusion; ciudadanía sustantiva y derechos de participación política en la ue: Límites del sistema y necesidad de una mayor inclusión. Revista de Derecho Comunitario Europeo 2022: 915–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faustini, Alessandra. 2025. Implications of the “human right to science” in the field of biolaw: Accessibility, public participation and political governance; Implicazioni del “diritto umano alla scienza” nel campo del biodiritto: Accessibilità, partecipazione pubblica e governance politica. BioLaw Journal 1: 147–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Ling, and Changming Shao. 2023. Analysis on the mechanisms and causes of political overshadowing on science -Based on the early pandemic governance in the U.S. [政治对科学的遮蔽机制及其成因分析-基于美国疫情治理初期实践的考察]. Studies in Science of Science 41: 971–79. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández de Castro, Pablo Fernando, and Omar Díaz-García. 2021. Active citizenship and political participation of women in Spain; CiudadanÍa activa y participaciÓn polÍtica de las mujeres en EspaÑa. OBETS 15: 501–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Frank. 1993. Policy Discourse and the Politics of Washington Think Tanks. Lanham: University Press of America. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Frank. 2000. Citizens, Experts, and the Environment: The Politics of Local Knowledge. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishkin, James. 1991. Democracy and Deliberation: New Directions for Democratic Reform. New Haven: London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fishkin, James. 2009. When the People Speak: Deliberative Democracy and Public Consultation, online ed. Oxford: Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, Archon. 2006. Varieties of participation in complex governance. Public Administration Review 66: 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, Fred, Danielle Goodwin, Heather Lovell, Helen Murphy-Gregory, Kate Beasy, and Marion Schoen. 2025. Political Science’s Engagement with the Sustainability Challenge: A Semi-Systematic Review of the Voluntary Sustainability Standards (VSS) Governance Literature. Sustainable Development 33: 459–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Xuede, and Fei Sun. 2025. Examining the Impact of Relative Performance Information on Citizen Satisfaction: The Moderating Role of Trust in Local Government. Public Administration and Development 45: 555–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobshäuser, Natalie, and Georg Weißeno. 2021. Does political participation in adolescence promote knowledge acquisition and active citizenship? Education, Citizenship and Social Justice 16: 150–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Kriti Priya. 2021. Impact of e-government benefits on continuous use intention of e-government services: The moderating role of citizen trust in common service centres (CSCs). International Journal of Electronic Governance 13: 176–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haesevoets, Tesssa, Arne Roets, Kristof Steyvers, Bram Verschuere, and Bram Wauters. 2024. Towards a multifaceted measure of perceived legitimacy of participatory governance. Governance 37: 711–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Alex Jingwei, and Liang Ma. 2021. Citizen Participation, Perceived Public Service Performance, and Trust in Government: Evidence from Health Policy Reforms in Hong Kong. Public Performance and Management Review 44: 471–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, Hali. 2023. Pulp and participation: Assessing the legitimacy of participatory environmental governance in Umkomaas, South Africa. Ecological Economics 208: 107794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutahaean, Martua, Ira Junianingsih Eunike, and Anastasia Debora Kurniati Silalahi. 2023. Do Social Media, Good Governance, and Public Trust Increase Citizens’ e-Government Participation? Dual Approach of PLS-SEM and fsQCA. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2023: 9988602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, Luis, and Rocio Valdés. 2022. Participation, citizenship and inclusive education: Possibilities to think of the student as a political subject; Participación, ciudadanía y educación inclusiva: Posibilidades para pensar al estudiante como sujeto político. Estudios Pedagogicos 48: 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kala, Devkant, Dhani Shanker Chaubey, Rakesh Kumar Meet, and Ahmad Samed Al-Adwan. 2024. Impact of user satisfaction with e-government services on continuance use intention and citizen trust using tam-issm framework. Interdisciplinary Journal of Information, Knowledge, and Management 19: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, Jin. 2022. ‘Democracy and Active Citizenship Are Not Just About the Elections’: Youth Civic and Political Participation During and Beyond Singapore’s Nine-day Pandemic Election (GE2020). Young 30: 247–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Ruqiang, and Loo See Beh. 2025. The Impact of Political Efficacy on Citizens’ E-Participation in Digital Government. Administrative Sciences 15: 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Yung. 2021. Government for Leaving No One Behind: Social Equity in Public Administration and Trust in Government. SAGE Open 11: 21582440211029227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Yung. 2024. Government performance and citizen trust before and after the Great Recession: The case of Greece and Italy. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 44: 1152–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Wenjuan. 2021. The role of trust and risk in Citizens’ E-Government services adoption: A perspective of the extended UTAUT model. Sustainability 13: 7671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Wenjuan, and Lan Xue. 2021. Analyzing the critical factors influencing post-use trust and its impact on Citizens’ continuous-use intention of E-Government: Evidence from Chinese municipalities. Sustainability 13: 7698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yifei, and Haoyun Shang. 2023. How does e-government use affect citizens’ trust in government? Empirical evidence from China. Information and Management 60: 103844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llano-Aristizábal, Sergio, and Jennie Peña. 2025. Pareto Principle and citizen participation in the editing of Wikipedia articles about Colombian government entities; Principio de Pareto y participación de los ciudadanos en la edición de artículos de entidades del Estado colombiano en Wikipedia. Apuntes 52: 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Prete, Anna. 2024. Political participation and financial education: Understanding personal and collective tradeoffs for a better citizenship. Economics Letters 244: 111943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Ting, Lizhi Jia, Linsheng Zhong, Xinyu Gong, and Yu Wei. 2023. Governance of China’s Potatso National Park Influenced by Local Community Participation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, Rizwanul. 2021. What explains citizen trust in public institutions? Quality of government, performance, social capital, or demography. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration 43: 106–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkoreit, Manjana. 2025. Political science and the Earth system: Adapting governance to planetary realities. British Journal of Politics and International Relations 27: 551–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Hongjing, and Loo See Beh. 2025. Impact of citizen participation through e-government platforms on satisfaction and trust. International Journal of Electronic Governance 17: 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Perez, César Omar, Karla Haydeé Ortiz Palafox, and Rigoberto Silva-Robles. 2024. Strengthening transparency in Mexico: Social accountability and citizen participation as drivers of democracy and government efficiency; Fortalecimiento de la transparencia en México: Responsabilidad social y participación ciudadana como impulsores de democracia y eficiencia gubernamental. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia 29: 581–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Dongmei, Xueping Liang, and Daifu Yang. 2025. e-Government development and environmental performance: Unravelling the dual mediation of regulatory enforcement and citizen participation in China. International Review of Administrative Sciences 91: 409–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühleck, Kathrin, and Andreas Hadjar. 2023. Higher education and active citizenship in five European countries: How institutions, fields of study and types of degree shape the political participation of graduates. Research in Comparative and International Education 18: 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myoung, Eunyoung, and Pey Yan Liou. 2022. Adolescents’ Political Socialization at School, Citizenship Self-efficacy, and Expected Electoral Participation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 51: 1305–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawafleh, Sami Ahmad, and Ali Saleh Khasawneh. 2024. Drivers of citizens E- loyalty in E-government services: E-service quality mediated by E-trust based on moderation role by system anxiety. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy 18: 217–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2023. Government at a Glance 2023. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, María, Dolores Gema, and Jóse Manuel Santos-Jaén. 2021. New forms of political participation in Spain as a central element in the construction of new models of citizenship: The post-conventional ones; Nuevas formas de participación política en España como elemento central en la construcción de nuevos modelos de ciudadanía: Las postconvencionales. Politica y Sociedad 58: e62099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oser, Jennifer. 2022. How Citizenship Norms and Digital Media Use Affect Political Participation: A Two--Wave Panel Analysis. Media and Communication 10: 206–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peresada, Olha, Oleksandra Severinova, Vitalii Serohin, Svitlana H. Serohina, and Olga Shutova. 2022. Intercultural Communications and Community Participation in Local Governance: EU Experience. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 11: 266–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poertner, Mathias, and Nan Zhang. 2024. The effects of combating corruption on institutional trust and political engagement: Evidence from Latin America. Political Science Research and Methods 12: 633–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramuditha, Rizky, Didin Muhafidin, Asep Sumaryana, and Elisa Susanti. 2024. Exploring the Impacts of e-Government Service Quality on Citizen Satisfaction and Trust: Evidence from Population Administration Services. Journal of Logistics, Informatics and Service Science 11: 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasari, Sri Langgeng, Nomahaza Mahadi, Nur Anis Nordin, and Dio Caisar Darma. 2022. Ethical Work Climate, Social Trust, and Decision-Making in Malaysian Public Administration: The Case of MECD Malaysia. Croatian and Comparative Public Administration 22: 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richey, Sean. 2023. The Influence of Local Patriotism on Participation in Local Politics, Civic participation, Trust in Local Government and Collective Action. American Politics Research 51: 357–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Saavedra, Miluska Odely, Erick Alexander Donayre Prado, Adolfo Erick Donayre Sarolli, Paola Gabriela Lujan Tito, Jóse Antonio Escobedo Pajuelo, Ricardo Enrique Grundy Lopez, Orlando Aroquipa Apaza, María Elena Alegre Chalco, Wilian Quispe Nina, Raúl Andrés Pozo González, and et al. 2025a. Chatbots and Empowerment in Gender-Based Violence: Mixed Methods Analysis of Psychological and Legal Assistance. Social Sciences 14: 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Saavedra, Miluska Odely, Luis Gonzalo Barrera Benavides, Iván Cuentas Galindo, Luis Miguel Campos Ascuña, Antonio Víctor Morales Gonzales, Jiang Wagner Mamani Lopez, and Maria Elena Alegre Chalco. 2025b. The Role of Law in Protecting Minors from Stress Caused by Social Media. Studies in Media and Communication 13: 373–85. Available online: https://redfame.com/journal/index.php/smc/article/view/7581 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Rodriguez-Saavedra, Miluska Odely, Luis Gonzalo Barrera Benavides, Iván Cuentas Galindo, Luis Miguel Campos Ascuña, Antonio Víctor Morales Gonzales, Jiang Wagner Mamani Lopez, and Ruben Washington Arguedas-Catasi. 2025. Augmented Reality as an Educational Tool: Transforming Teaching in the Digital Age. Information 16: 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncancio, Andres Felipe, Kelly Joselin Espitia Ortega, José Javier Nuvaez Castillo, and Valerie Michelle Vallejo Vilaró. 2025. El e-gobierno como proposición de gobernanza en los Procesos de dinamización de la participación ciudadana: Concepción de modelo de gestión. Encuentros 24: 180–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Swapnil, Arpan Kar, and Gupta. 2024. Untangling the web between digital citizen empowerment, accountability and quality of participation experience for e-government: Lessons from India. Government Information Quarterly 41: 101964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez Elías, Matias, and Alison Noboa. 2024. Online citizen participation in local governments an analysis of the ideas mechanism (montevideo decide) and the participatory budgets of san lorenzo and vicente lópez; la participación ciudadana online en los gobiernos locales un análisis del mecanismo ideas de montevideo decide y los presupuestos participativos de san lorenzo y vicente lópez. Prisma Social 44: 274–306. [Google Scholar]

- Takakusa, Daijiro, and Hikaru Kinoshita. 2024. Astudy on the complex public facility development using pure-cm system by local government (part 3): Case study of cmr’s role in the citizen participation on the construction project by small municipality, yabu city. AIJ Journal of Technology and Design 30: 1559–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzagkarakis, Stylianos Ioannis, and Dimitrios Kritas. 2023. Mixed research methods in political science and governance: Approaches and applications. Quality and Quantity 57: 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme. 2024. Human Development Report 2023/2024: Breaking the Gridlock—Reimagining Cooperation in a Polarized World. New York: UNDP. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Van Nguyen, Phuong, Demetris Vrontis, Linh Doan Phuong Nguyen, Trang Thi Uyen Nguyen, and Charbel Salloum. 2025. Unraveling the Role of Citizens’ Concerns and Cognitive Appraisals in E-Government Adoption: The Impact of Social Media and Trust. Strategic Change 34: 675–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejseli, María, and Fabiola Kamberi. 2021. The intercultural communication and community participation in local governance: The case of north Macedonia and Kosovo. Journal of Liberty and International Affairs 7: 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vento, Isak. 2024. Trust, collaboration, and participation in governance: A Nordic perspective on public administrators’ perceptions of citizen involvement. Public Administration Review 84: 870–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verástegui, Mateo Dimitri Galiano, Jiang Mirko Medina-Quintero, and Fabian Ortiz-Rodríguez. 2025. Perceived Usefulness and Ease of Use of E-Government to Generate Trust and Intention to Use by Citizens. Journal of Technology Management and Innovation 20: 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Watfa, Ali Assad, and Driss Ait Ali. 2025. From national loyalty to student political participation: The mediating effect of university citizenship promotion. Frontiers in Education 10: 1600175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 1997. World Development Report 1997: The State in a Changing World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/5980 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Yang, Guangbin. 2021. The Paradigm Shift of Political Science from Being “Change-oriented” to “Governance-oriented:“ A Perspective on History of Political Science. Chinese Political Science Review 6: 506–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Yong, Ping Yu, and Xiaojun Zhang. 2024. More trust in central government during the COVID-19 pandemic? Citizens’ emotional reactions, government performance, and trust in governments. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 108: 104555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Runxi, Liu Yang, Wuyue Zhang, Richard Evans, and Junjie Luo. 2025. Government social media and citizen trust: The mediating role of psychological distance and perceived government performance. Public Management Review, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Pan, and Zhouling Bai. 2024. Leaving messages as coproduction: Impact of government COVID-19 non-pharmaceutical interventions on citizens’ online participation in China. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 11: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Mingxi, Jingrui Ju, Wang Yuan, Luning Liu, and Yuqiang Feng. 2025. Exploring the Roles of Informational and Emotional Language in Online Government Interactions to Promote Citizens’ Continuous Participation. Public Performance and Management Review 48: 468–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.