Abstract

Social sustainability, particularly in the form of inclusive cities, is high on the global agenda. One local manifestation working towards these goals in Qatar is Qatar Foundation for Education, Science, and Community Development’s Education City: a large campus with multiple schools, universities, communities, and cultural institutions, as well as home to one of the major stadiums of the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022 tournament, hitherto the most accessible World Cup in history. This study is based on a survey that explores the experiences of people with and without disabilities in their interactions with Education City’s infrastructure, facilities, and services, as well as the legacy of hosting FIFA. It found that people’s experiences of social inclusion and belonging were positive given the multiple inclusive programs hosted by Education City and that hosting FIFA accelerated this shift. Yet, there is still significant room for improvement in the availability and quality of facilities, services with trained staff, clear communication, and advertisement and raising awareness of institutionalizing policies that reduce discrimination and stigma. Designing disability-inclusive cities is a complex grand societal challenge that requires intentional integration and constant monitoring and evaluation in an increasingly urbanized world. This is one of the first studies on Qatar and post-tournament legacy after a World Cup that prioritized accessibility.

1. Introduction

Qatar ratified the UN Convention of Rights of People with Disabilities (UNCRPD) in 2008. In 2022, it hosted the most inclusive World Cup in the history of FIFA, pioneering many new initiatives and setting ‘a new benchmark in accessibility for future FIFA World Cup tournaments and other mega-sporting events’ (FIFA 2023). Qatar is a small fledgling state with a global and ambitious vision (Kamrava 2015). To this end, it has undergone rapid development in the last few decades in all spheres and sectors—social, political, economic—as well as rapid reforms in education and healthcare (Amin et al. 2024a; Rahman and Al-Azm 2023). Being the first Arab and Muslim nation to host the FIFA World Cup, one of the most prestigious sporting events in the world, was one of its crowning moments (Cochrane et al. 2024). Signing disability rights treaties and making accessibility a core feature of FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022 are indications of Qatar realizing its commitment to people with disabilities.

However, disability overall is defined as a “wicked” policy problem—a socially complex phenomenon with multiple, intersecting and changing interdependencies with no one clear definition nor common solutions (Stace 2015). Despite the UNCRPD boasting the highest number of signatories on the first day, the many intersecting layers of complexity occludes its successful implementation in most countries. Furthermore, studies illustrate that legacies from hosting sporting events are also highly overrated, with “mega-event syndrome” taking over, which involves short-term fixes or vanity projects taking precedence over deeper and meaningful changes (Müller 2015). As some put it, it results in only “physically accessible sporting venues set against a generally inaccessible urban realm” (McGillivray et al. 2018, p. 5). Despite lofty pledges, a lack of including people with disabilities in the design and implementation process leads to many accessibility gaps remaining (Dickson et al. 2016).

This paper explores the case of Qatar Foundation for Education, Science, and Community Development’s Education City in Qatar. Spanning 12 square kilometers, Education City is home to K-12 schools; international branch campuses and a home-grown research university; start-up incubators; a technology park; heritage sites; cultural institutions; the national library; and an Education City Stadium (QF n.d.b). This stadium has a permanent sensory room for children or young adults with sensory-processing difficulties. It was built for the World Cup for fans with disabilities to watch the football live in a safe space alongside their families. Qatar was the first to pioneer sensory rooms inside stadiums during World Cup matches, and it was also one of the flagship accessibility initiatives during FIFA (Inside-Fifa 2023). Like all other stadiums, it met accessibility standards, such as dedicated accessibility seating, adapted toilets, and lower concession stands. This stadium was also the “first stadium in the world to receive a five-star design and build certification under the Global Sustainability Assessment System (GSAS)” (QF n.d.c).

This study is based on a survey covering Education City’s community experiences and awareness regarding accessibility, as well as the legacy of hosting the FIFA World Cup. The aim of the survey was to explore social inclusion and accessibility for people with disabilities in relation to the current initiatives, infrastructure and the post-tournament impact of FIFA to identify potential pathways for improvements. Hitherto, very few studies explore disability, accessibility in Qatar (Shaban and Amin 2023, 2024) and to the authors’ knowledge, this is one of the first studies that includes the legacy of accessibility after hosting a FIFA World Cup tournament. The results reveal that, although accessibility programs and inclusive measures have been established to some extent and overall, the majority of people felt a positive sense of social inclusion and belonging, but there are still a significant proportion that feel otherwise. More needs to be established in terms of accessible infrastructure, facilities and services with trained staff, clear communication channels and raising awareness and introducing policies to reduce stigma and discrimination. People with disabilities and local experts should be a part of this process. These findings resonate with the vast majority of studies on disability inclusion within cities.

The paper begins with a background on social sustainability and inclusive cities, followed by an overview of Qatar Foundation and its accessibility initiatives in Education City. It then outlines the methodology, the results of the survey, engages in a discussion, and then concludes with recommendations.

2. Social Sustainability and Inclusive Cities

The section places the study within the wider context of social sustainability and inclusive cities. Beginning from the perspective of preserving the environment, sustainability has since evolved into a more holistic concept containing three pillars: environmental, economic, and social, the latter of which has received relatively little attention due to being introduced much later (Eizenberg and Jabareen 2017). Social sustainability is a multi-dimensional strand that interrogates the social goals of sustainable development.

There are various definitions and applications of social sustainability. Vallance et al. (2011) have categorized these attempts into three broad directions. First is the development social sustainability that directly stems from the classical texts of sustainable development, such as the famous 1987 Bruntland Report, Our Common Future, which focuses on economic growth, reducing poverty, and inequity. Second is bridging social sustainability, which is the promotion of eco-friendly behavior and stronger environmental ethics. The overarching aim here is to connect or make better “bridges” between people and the bio-physical environment that range from non-transformative and incremental changes, such as recycling schemes, to transformative, radical changes that fundamentally reconfigure the relationship between humans, the environment, and non-humans. Third is the maintenance of social sustainability. This is the most recent iteration and focuses on preserving traditions, cultures, and landscapes during rapid development, migration and technological advancement (Vallance et al. 2011).

Many have conceptualized social sustainability as a blend of distinct yet related concepts. Hemani et al. (2017) defines social sustainability as four Ss: social capital, social cohesion, social equity, and social inclusion. As Rebernik et al. (2020) state, despite differences, most definitions include social inclusion and social equity. The former, social inclusion, is about accessibility to physical buildings and structures as well as information, processes, and products. The latter, social equity, is about ensuring that access is fair and just recognizing diversity and equal membership to society (Bramley et al. 2016). This paper also takes this broad definition of social inclusion and equity as a mechanism for the broader goal of social sustainability.

In an era of rapid urbanization, social sustainability is inextricably linked to the development of inclusive cities. Indeed, Sustainable Development Goal 11 is entitled “Sustainable Cities and Communities”, with the main goal being to “make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable”. Numerous international frameworks and agendas have developed towards this end, including The New Urban Agenda, adopted by the UN in 2016 (UN-Habitat 2016); the UN paper on the right to the city and cities for all (UN-Habitat 2017); Smart Cities for All: A Vision for an Inclusive, Accessible, Urban Future by The Global Initiative for Inclusive ICTs, an advocacy initiative launched by the United Nations Global Alliance for ICT and Development (Korngold et al. 2017); and The Inclusion Imperative: Towards Disability-Inclusive and Accessible Urban Development published by Disability Inclusive and Accessible Urban Development Network established in partnership with United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (CBM 2019). Article 30 of the UNCRPD (2006) also emphasizes the importance of participation in recreation, leisure, sports and cultural activities—a lot of which takes place in urban centers.

There are vast benefits to social inclusion for PWDs. Numerous studies illustrate their boost in confidence, self-esteem and overall mental well-being (Bota et al. 2014; WHO and World Bank 2011). This is heightened especially when there is interaction with their peers without disabilities (Asmus et al. 2017), which also has a “positive spill-over effect” on the latter group (Schur et al. 2014; Tucker et al. 2020; Wilson et al. 2016). Studies on inclusive education settings illustrate that students without disabilities develop a deeper sense of empathy, reduced prejudice, and a more understanding attitude, as well as stronger feelings of belonging and acceptance amongst all students (Kart and Kart 2021; Shogren et al. 2015). Both organized activities and spontaneous interaction with the wider community foster valuable moments, although some have found that the latter is more important (Louw et al. 2019; Milot et al. 2021). In all interactions, there is a socio-ecological framework that includes non-segregated spaces where participation, as opposed to mere presence, yields the greatest value for all community members (Bigby et al. 2018).

However, despite the global treaties, agendas and benefits, some argue that the definition of inclusion is too broad; there is still a lack of conceptual depth, guidance, and understanding of what specifically disability inclusion entails (Rebernik et al. 2020). Failure to grasp complexity leads to an ad hoc approach as opposed to a holistic, system-wide framework that is underscored by the appreciation and impact on the quality of life of the wider population (e.g., families, the elderly), not only those with disabilities (Rebernik et al. 2020). Furthermore, even if certain services are available, access to these services for PWDs is an issue fraught with difficulties. Physical inaccessibility, lack of information as well as cultural and political stigma play a complex role in erecting, often invisible, barriers (Amin et al. 2024b; Badran et al. 2023a, 2023b, 2024a, 2024b; Grills et al. 2017).

3. Background on Education City and Accessibility

In 1995, His Highness Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, the Father Emir of Qatar, and Her Highness Sheikha Moza bint Nasser established Qatar Foundation, a non-profit organization where:

“centres and programs focused in education, research and innovation, and community development intertwine for the benefit of Qatar, and the world. Across our [Qatar Foundation’s] unique ecosystem—which is supported by partnerships with leading international institutions—we are addressing Qatar’s most pressing challenges; creating local, regional, and global impact; and empowering people to shape both the present and the future”.(QF n.d.a)

The main flagship initiative of Qatar Foundation is Education City—a dynamic hub that, as mentioned above, encompasses various schools, universities and national institutions. As of 2023, it hosts seven university campuses and six schools.1 Education City is designed as a cohesive unit that promotes interactions across its educational and recreational components designed with an internal electric tram suitable for people with disabilities with audio and visual communication and step-free access. That being said, some stations are far from certain buildings, which poses difficulties especially in the heat, and some features still require the assistance of trained support personnel. Education City is also well-integrated with major transport networks in Qatar, including the recently inaugurated Doha Metro, with all stations also being designed with high accessibility standards. See Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 below for pictures of parts of Education City.

Figure 1.

Aerial view of Education City showcasing Qatar Foundation Headquarters, Think Bay, Medbay, Carnegie Mellon University in Qatar, and the Qatar National Convention Center.

Figure 2.

Oxygen Park.

Figure 3.

HBKU’s Minaretein Building including Education City Mosque and surroundings.

Education City includes many of Qatar Foundation’s pre-university education schools, international branch campuses, Hamad Bin Khalifa University (a homegrown university), and research centers. These institutions provide Qatari and international students with high-quality education, including higher education, postgraduate studies, research, and executive education. Community development is embedded in all institutions and structures across Education City. At the pre-university level, Education City features branches of the Qatar Academy, which offers an International Baccalaureate curriculum to students, primarily Qatari children, from early childhood through to K-12 education. There is a school dedicated to science and technology for high school students which also offers them the chance to earn college credits through the American Advanced Placement program. This category also includes dedicated schools such as the Awsaj Academy and Renad Academy, which are specifically catered for children with diverse learning needs and intellectual impairments, and satellite programs are available in Al Wakra and Al Khor. The Warif Academy, located in West Bay, was launched in January 2025 in collaboration with the Qatar’s Ministry of Education and Higher Education and is especially for children with severe disabilities. Also, the Academic Bridge Program equips high school students with essential skills for university admission if they require it.

A core aspect of Education City are the international branch campuses, or IBCs. Currently, they consist of the following: the Virginia Commonwealth University School of the Arts Qatar, established in 1998; Weill Cornell Medicine - Qatar, established in 2001; Texas A&M University at Qatar, established from 2003 to 2024; Carnegie Mellon University in Qatar, established in 2004; Georgetown University in Qatar, established in 2005; Northwestern University in Qatar, established in 2008; and HEC Paris in Qatar, established in 2010. Wilkins and Huisman (2012) articulate the concept of an IBC as a scholarly entity that is partially or wholly owned by a non-domestic institution. This entity operates under the auspices of the said institution, providing direct instructional services and leading to qualifications endorsed by the institution (Wilkins and Huisman 2012). The establishment of IBCs, while not a novel innovation, saw a distinctive incarnation in Qatar’s Education City, a consortium of IBCs from American and European universities, an unparalleled venture in the realm of IBCs and global academia. Crist (2015) lauds the Education City model as a pioneering development, coining it a “university of universities”, a notion previously unattained globally, fostering a robust collaborative environment among varied universities towards nurturing a knowledge-based economy in Qatar. A knowledge-based economy is an economic model where knowledge is a pivotal resource for economic and social advancement (Donn and Manthri 2013). In this context, Qatar Foundation designed Education City as a key player to move towards a knowledge-centric economy, diminishing its reliance on the hydrocarbon sector through the development of human capital through education and fostering innovation to spur economic growth. This facet of Education City is complemented by postgraduate offerings and a robust research infrastructure, including four research institutes, the Qatar Research, Development and Innovation Council, and the Qatar Science and Technology Park, aimed at driving forward the nation’s research and development agenda.

Education City’s commitment to community development is reflected through a diverse array of entities, becoming a conduit for initiating many different projects impacting the local Qatari society. This includes the Qur’anic Botanic Garden, the Qatar National Library (QNL), and the Minaretein Center (Education City Mosque), enriching the cultural, educational, and social fabric of Qatar.

Regarding social inclusion, particularly for people with disabilities, Qatar Foundation has initiated some specialist programs and acts as home to various accessible facilities. One recent project, initiated in 2016 and officially launched in 2019, was the Ability Friendly Program for sports by Qatar Foundation, triggered by discussions held during the World Innovation Summit for Health (WISH)—a global healthcare initiative launched by Qatar Foundation. WISH’s global research on autism and a grassroots campaign by local mothers catalyzed the development of this inclusive sports initiative. Initially, the program attracted 181 participants, mainly male, with a significant number being diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (El Akoum and Dyer 2022). By 2019–2020, the program expanded by over 50%, offering football and swimming across multiple locations, including the Education City Recreation Center and Qatar Academy Al Khor. This period marked an increase in female participation due to effective school outreach, aligning with the program’s commitment to gender equality. Despite a pandemic-induced decline in 2020–2021, the program maintained robust enrolment and even opened a new venue at the Qatar Academy Al Wakra (El Akoum and Dyer 2022). Moreover, a survey administered to participants’ caregivers indicated a notable positive impact on children’s development, with 96.72% reporting improvements post-participation. This concise review highlights the Ability Friendly Program’s growth, community impact, and ongoing commitment to diversity and inclusion in sports within Qatar (El Akoum et al. 2023).

Another innovative initiative is the Al Shaqab Equine-Assisted Therapy Program. This is a specialized therapy designed to leverage the benefits of equine-assisted activities to improve physical, emotional, and cognitive development and psychological well-being for those with special needs (Al-Shaqab n.d.).

From a communications perspective, there has been a concerted and conscious effort by the management to add more accessibility features to the website and media platforms including features such as Arabic sign interpretation in events and developing guidelines for how to create an accessible/inclusive event. To this end, Qatar Foundation also recently launched an Autism Task Force and an overall Accessibility and Inclusivity Working Group which coordinates experts across the Qatar Foundation ecosystem to understand how to make Qatar Foundation and all its entities more accessible and inclusive, the latter of which was a direct response to the results and recommendations of this survey.

Lastly, as mentioned above, Education City was home to one of the eight stadiums used for the FIFA World Cup, designed with the highest accessibility and sustainability standards, including pioneering sensory rooms for children and adults with sensory disabilities. Qatar Foundation further enhanced the fan experience at the Education City Stadium by offering performances by artists with disabilities. Furthermore, it trained 250 Accessibility Volunteers for the World Cup to effectively engage with fans with disabilities. To summarize, there has been a concerted effort from the management to establish accessible and inclusive programs and institutions within Education City, which has been boosted through the hosting of the World Cup.

4. Methodology

This study was ethically approved and administered by Qatar Foundation’s Strategy and Impact Directorate (SID) (approval number: QBRI-IRB-2023-107). The overall research questions of the study are:

- (1)

- How do people engage with the facilities and events held at Education City?

- (2)

- To what extent are the activities and facilities accessible to people with disabilities?

- (3)

- What impact did hosting the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022 have on Education City and accessibility?

The study employed a quantitative approach through a structured online survey with Likert scales to assess the accessibility facilities, support, and environment at Education City. The survey comprised 10 close-ended questions designed to elicit information on several key aspects: the level of accessibility within Education City, the ease of use of its facilities, the overall experience of visitors, the prevalence of stigma, and the benefits and limitations of services for people with disabilities. This was followed by a few open-ended questions that allowed the respondents to express their thoughts and describe their experiences, which might not have been possible through close-ended questions. It took approximately seven minutes for respondents to complete the survey. To accommodate Education City’s diversity, the survey was made available in both the Arabic and English language, ensuring broader participation. A notable feature of the survey design was the incorporation of a branching question that targeted respondents with disabilities or those who knew people with disabilities. This survey design meant that the opinions, experiences, and perspectives of those with and without disabilities could be compared.

The survey targeted a broad section of the Education City community, including Qatar Foundation staff, students, families, community members, and volunteers. A total of 626 individuals participated in the survey. The respondents were categorized based on their connection to disability, with 15 indicating they had a disability, 202 knowing someone with a disability, and 486 neither having a disability nor knowing someone with one. This segmentation allowed for comparative analysis across different experiences and perceptions regarding accessibility.

Data collection occurred from 5 February 2023 to 28 February 2023, utilizing the online platform SurveyMonkey for the survey administration. This period was chosen to ensure a broad window for participation, maximizing respondent engagement. The online methodology facilitated ease of access for participants and streamlined the data collection process, enabling efficient handling of the bilingual survey responses.

The study used a voluntary response sampling method, which is where participants choose to take part in a survey. Studies note several advantages to this method, including increased engagement and motivation, as the participants who do respond are typically more interested and invested in the subject matter, yielding more authentic and higher-quality responses (Brauer et al. 2021). Voluntary web-based surveys are also the most cost efficient, as they do not require interviewers or physical surveys printed out (Guzi and de Pedraza García 2015). That being said, a key limitation to this method is the non-response bias, which possibly could skew the data (Cheung et al. 2017). There is also the major assumption that the changes instigated by the FIFA World Cup will be long-lasting.

Furthermore, due to the numerous different types of organizations and institutions (as described above) and being open to the wider public, it is very difficult to estimate the number of people in the Education City community population. It is not a “traditional” city where we can count residents. There will be some staff, for example, who themselves (with their families) take advantage of all the services and organizations while others, for various reasons, do not. Also, there will be individuals and families who are not officially connected to any of the institutions inside Education City but who regularly attend the public events and services, such as QNL.

All Qatar Foundation permanent staff, including Qatar Foundation school teachers and students’ families, were emailed and sent an SMS of the survey as well as being put on screens across Education City buildings with QR codes. Regular reminders were also sent out via email and SMS to complete the study. Therefore, a key limitation to this study is the unknown population size. Findings must consider these limitations and must not be overly generalized.

The data analysis aimed to explore the accessibility level, the usability of facilities, and the overall visitor experience within Education City, with a particular focus on those affected by disabilities. A statistical analysis was conducted on the quantitative data derived from the close-ended questions and Likert scale responses. Comparative analyses and chi-square tests were also performed to understand the differences in perceptions and experiences between those with disabilities, those knowing someone with a disability, and those without any direct connection to disability. The analysis sought to identify patterns and the prevalence of stigma while assessing the impact of current accessibility measures.

5. Results and Discussion

The results are divided into three sections: the first is all the respondents’ attendance and usage of the various facilities at Education City; the second focuses on those respondents with disabilities or who know someone with a disability (e.g., parents with a child with disabilities) and measures their sense of belonging and social inclusion; the third examines the impact of the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022 tournament on accessibility in Education City, and in general, with a comparison between people with and without disabilities.

5.1. Section 1: Interaction with Education City

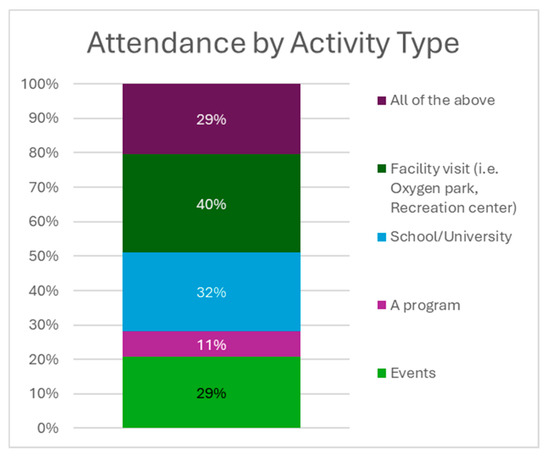

This section begins with Figure 4 and Figure 5, which explore the types of activities the respondents, in general, participate in.

Figure 4.

Activities people participate in in Education City.

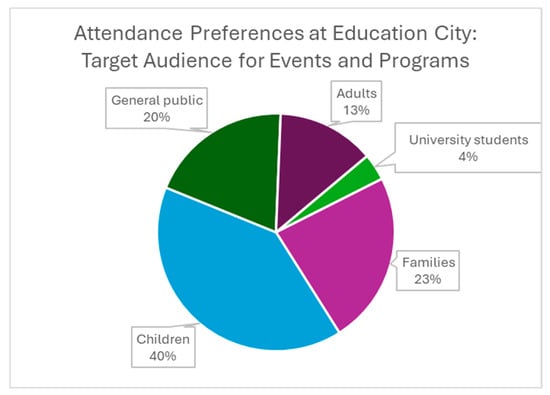

Figure 5.

Type of event preference.

As the graph illustrates, 29% of the respondents stated that they had visited Education City to attend specific events. Another 40% of the respondents mentioned that they visited Education City to access its various facilities, such as the park, library, or gym. The survey also revealed that 32% of the respondents visited Education City to attend school or university. Additionally, 11% of the respondents visited Education City to attend a regular program, for example, the Ability Friendly Program. Lastly, 29% of the respondents indicated that they visited for all the reasons mentioned above. In terms of the target audience, 40% of the respondents attended events aimed at children, while 23% attended those aimed at families. Additionally, 20% of the respondents attended events for the general public, 13% attended those targeted at adults, and only 4% attended events targeted at university students.

In short, the survey was completed by a wide variety of people utilizing the different facilities and initiatives run in Education City. There is more representation (63%) towards children and family activities first, and then the general public and adults (33%), and less representation (4%) of university students. This is probably because the survey was not sent directly to university students but was around on screens in the public spaces.

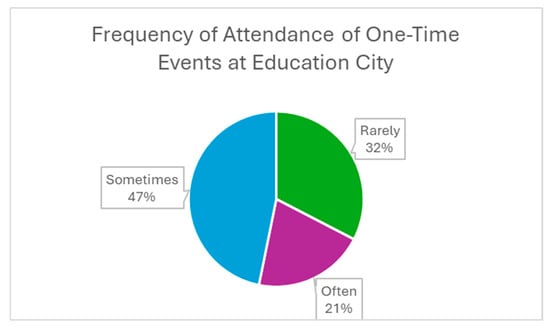

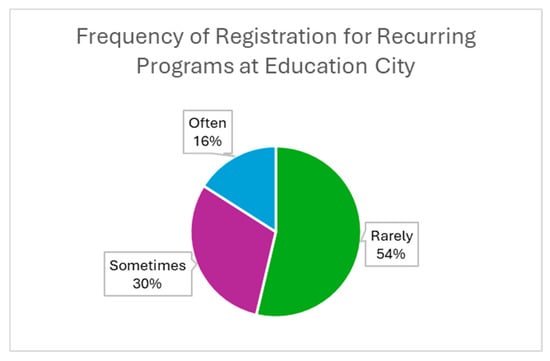

Moving from type of event to frequency of attendance, Figure 6 and Figure 7 exhibit the frequency of attending one-time and occurring events.

Figure 6.

Frequency of attending one-time events.

Figure 7.

Frequency of attending recurring programs.

According to the survey, most of the respondents attended one-off events either sometimes (47%) or often (21%). Just less than half (46%) attended recurring programs, with 30% attending sometimes and 16% attending often. This corresponds with Figure 4, where the least attended activity was the recurring program, which requires regular commitment.

To summarize Section 1 results, the respondents of the survey are spread over their types of usage and the frequency of attendance of Education City facilities and activities. There is a skew towards family-centric events but an almost even split between those who attend recurring events compared to one-off events.

5.2. Section 2: Respondents with Disabilities

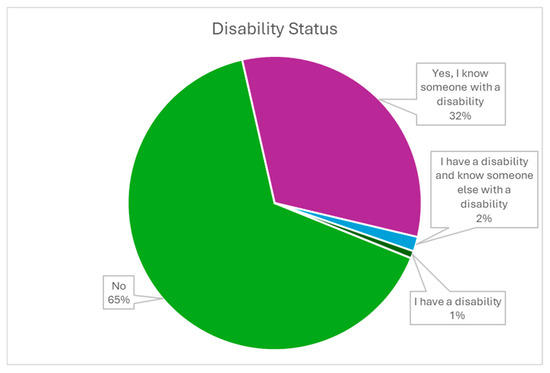

This section explores the specific experiences of those who either have a disability themselves or who know someone with a disability (most likely their child). According to the survey, as shown in Figure 8 below, 217 people were in this category, which is 35% of the total survey respondents.

Figure 8.

Disability status.

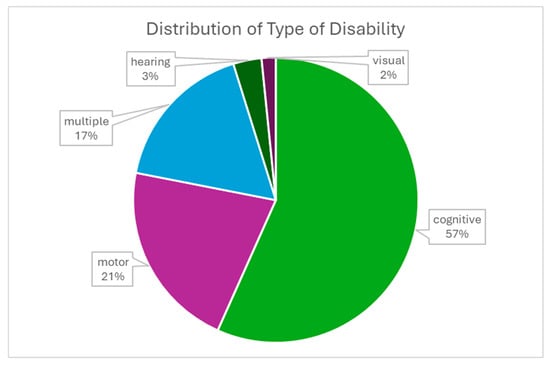

To better understand the needs of people with disabilities, we classified them into five categories based on hearing, visual, cognitive, and motor impairments, as well as, for those who had more than one type, multiple impairments. The results are illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Distribution of type of disability.

Of this group, 2% reported that the disability was related to visual impairment, 3% reported hearing impairment, 57% reported cognitive impairment, 21% reported motor impairment, and 17% reported multiple types of impairment. These findings highlight the diverse needs and experiences of people with disabilities in the Education City community. Of the 217 people who reported that they had a disability or know someone with a disability, only 149 fully completed the survey. The following is based on the answers of those 149 respondents. Figure 10 explores their experiences of the facilities and services at Education City.

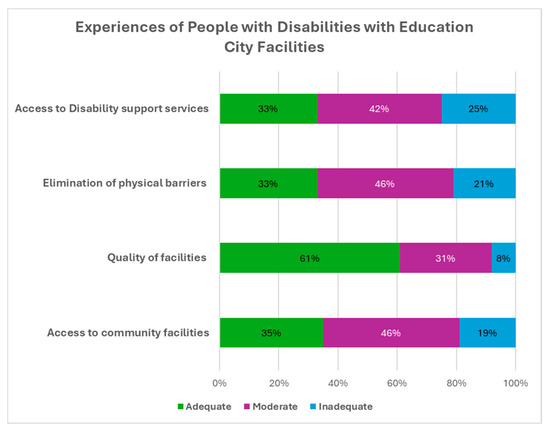

Figure 10.

Experiences of people with disabilities with Education City’s facilities.

Figure 10 illustrates that many people with disabilities or those related to them feel that the facilities are overall adequate to moderate. This shows that, in general, the structure is heading towards the right direction but still requires improvement. There are those who feel that the facilities are inadequate, and the goal is to ensure the vast majority, if not all, choose “adequate” rather than “moderate”. Figure 11 explores accessibility in terms of physical and psychological barriers.

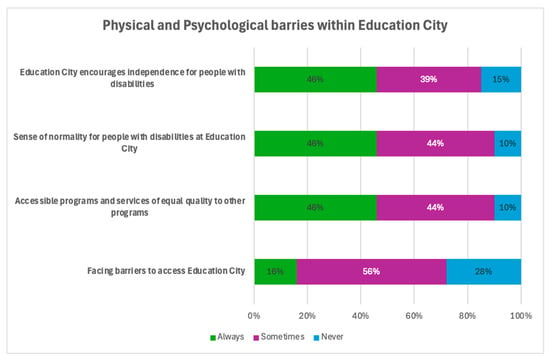

Figure 11.

Physical and psychological barriers within Education City.

Similarly to Figure 10, Figure 11 illustrates that, although there are a significant number of people who have positive experiences and do not experience physical and psychological barriers, there is still a sizeable number that do experience obstacles. These results suggest that, while efforts are underway to increase accessibility and inclusivity in Education City, there is a need for more attention and resources to ensure that individuals with disabilities can fully participate in and access the opportunities available to them both physically and emotionally. Figure 12 explores different measures of social inclusion in Education City.

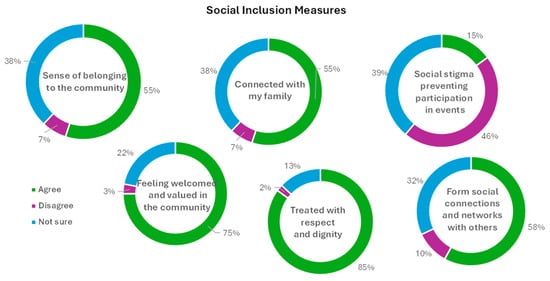

Figure 12.

Feelings of social inclusion for those with disabilities or who know people with disabilities.

As can be seen in Figure 12, in each of the six categories, more than 50% answered positively and felt socially included. Connecting these results with the data above, a chi-square test was conducted to examine the association between the frequency of attending events and feelings of social inclusion. Where participants with disabilities answered how often they attended one-off and recurring events (often, sometimes, rarely), as shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7, this was tested with the three statements on social inclusion: feelings of social belonging to the community, social connections and networks with others, and feeling more connected as a family.

According to the chi-square tests, there are significant associations between attending recurring events and the three feelings of social inclusion measured. Respondents from the disability population who recorded that they attend recurring events sometimes or often were more likely to agree that they felt a sense of belonging to the community, they had greater social connections and networks with others, and that they felt more connected as a family. The chi-square tests were, respectively: χ2 (4, N = 149) = 11.20, p = 0.02; χ2 (4, N = 149) = 19.73, p < 0.001; χ2 (4, N = 149) = 19.19, p < 0.001. The opposite is also true, as those who reported greater feelings of social inclusion, in all three questions, were more likely to record that they frequently attended events. A chi-test square also indicated a significant association between attending a one-off event and a sense of social belonging to the community, χ2 (4, N = 149) = 10.20, p = 0.004. The results indicate, perhaps unsurprisingly, that the more one attends events, the more they feel connected with the community, as well as an increasing connection within their family unit.

However, there were sizable numbers who were either unsure or disagreed, especially in the sense of belonging, forming social connections and connection with their family and social stigma. This was explored further. If, on the question on social stigma preventing participation in events, the respondent answered “agree” or “not sure”, they were directed to open-ended questions asking them to give examples and how these challenges could be eliminated. Answers fell into two categories: social acceptance and facilities. In terms of the former, lack of normalization, awareness, cultural stigmas, and feeling that they would be a burden or in the limelight were the common answers. In terms of the latter, people wrote about a shortage of disability support services, facilities, infrastructure, trained staff, as well as inaccessible communal spaces.

People were then asked more specifically about improvements. Answers fell into five categories: (1) educational campaigns that are both for people with disabilities to know which areas are accessible and all the available facilities, as well as championing and advocating for neurodiverse people for the general public to increase their social awareness and acceptance; (2) facilities need more specialized staff and better accessible physical infrastructures, such as disability-friendly access at all entrances; (3) more inclusive activities to normalize the appearance of people with disabilities in all spaces; (4) more jobs and career opportunities for people with disabilities across Qatar Foundation, including the incorporation of the latest technology to act as enablers; and (5) top-down systematic change that embeds inclusivity and accessibility in all policies and regular audits across all sectors and activities of Qatar Foundation.

To summarize, Section 2 explored the specific responses of people with disabilities and their experiences with Education City’s facilities, physical and psychological barriers, as well as various other measures of social inclusion. Although the overall results were positive, there were significant numbers who felt there needs to be improvement. These participants had the space in the survey to then explain how they would eliminate barriers and improve services that largely fell into two categories: first, education, raising awareness and normalization; second, specialized facilities, support and infrastructure, as well as systematic policies to ensure inclusion.

5.3. Section 3: FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022™ and Its Legacy

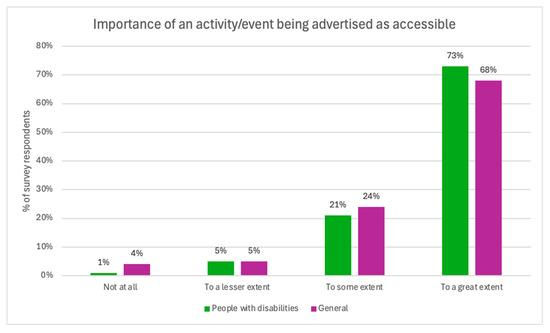

This section compares the perceptions of people with and without disabilities regarding the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022™ and its impact on accessibility during and after. Figure 13 begins with an overall question on the importance of explicitly advertising an event as accessible.

Figure 13.

Importance that an activity is advertised as accessible.

The results indicated that both the people with and without disabilities recognized the need to advertise an event as inclusive-friendly. To confirm these findings, a chi-square test was conducted which revealed no correlation between the two groups. This suggests that, overall, there is a similar level of social awareness around accessibility among both groups on this point. Figure 14 then focuses on the legacy of FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022™ in regard to accessibility in Education City.

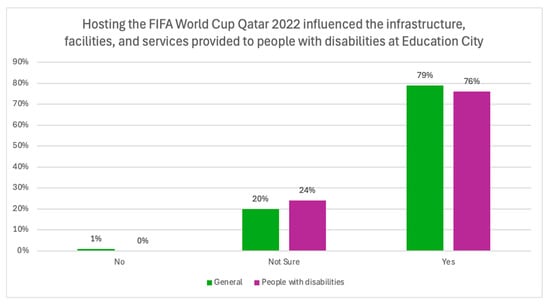

Figure 14.

Hosting FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022™ and its influence on Education City.

As Figure 14 showcases, people with and without disabilities believed that the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022™ had an impact on accessibility at Education City in terms of infrastructure, facilities, and services. To confirm these findings, a chi-square test was conducted which revealed no correlation, which means there is a similar perception between the two groups on this question. However, the next two figures show a difference. Figure 15 and Figure 16 illustrate the findings on the perception that people with disabilities enjoyed a safe, dignified and equitable experience compared to people without disabilities during the tournament.

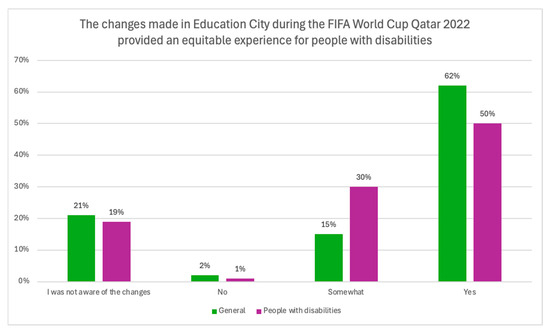

Figure 15.

Equitable experiences during FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022.

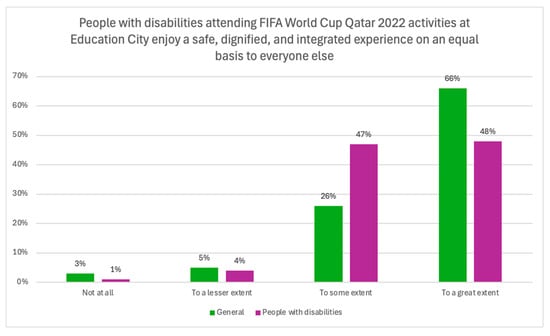

Figure 16.

Safe, dignified and integrated experience.

Figure 15 shows the results of both groups and their perception of the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022 in regard to having an equitable experience for both people and without disabilities. It is interesting to note a sizeable number (approximately 20% in both groups) were not aware of the changes despite it being the most accessible FIFA World Cup in history. On the other side of the graph, 62% verses 50% of people without and with disabilities, respectively, felt the experience was equitable. A chi-square test was conducted and found a significant difference between the responses (χ2 = 16.61, df = 3, p < 0.001, N = 486) in relation to the changes made in Education City during the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022.

Figure 16 explores whether the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022 experience was safe, dignified and integrated for people with disabilities. Similarly to Figure 16, people without disabilities were more positive, with 66% answering “to a great extent” compared to only 48% of the other group. Again, a chi-square test indicates a statistically significant difference between the two groups (χ2 = 19.45, df = 3, p < 0.001, N = 486). Overall, these results suggest that there are significant differences in the perceptions of the two groups regarding the experiences of people with disabilities during the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022 activities at Education City.

In short, Section 3 explored the experiences and legacy of the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022 for people with and without disabilities in Education City. Both groups broadly agreed on the importance of events being explicitly advertised as accessible and that hosting the World Cup made a positive difference to Education City in terms of its facilities, services and infrastructure. However, there was a statistically significant difference in terms of the equitable and integrated experience where people with disabilities felt this was true “to some extent” rather than “to a great extent”, and vice versa for those without disabilities.

5.4. Summary

Looking at the results, what is striking is that these barriers and facilitators found within Education City corroborate the vast majority of studies on cities in general, which strengthens the validity and reliability of these findings. As discussed above in Section 2, research converges on four key barriers to social inclusion in the city: the first is stigma, negative attitudes and stereotypes from the wider community; second is the lack of accessible infrastructure, such as narrow and heavy doors, large open areas to cross with difficulty in finding the entrance and stairs; third, is the shortage of suitable facilities with trained staff and personnel; fourth is the lack of accessible communication in the facilities, support, and overall landscape (Bokányi et al. 2021; de Oliveira Neto et al. 2020; Louw et al. 2019; Overmars-Marx et al. 2014). In terms of facilitators, studies show that removing the aforementioned barriers and involving people with disabilities as part of the planning, monitoring, and evaluation process is essential (Chen et al. 2022; Smith et al. 2010).

6. Conclusions

Social sustainability, particularly in the form of inclusive cities, is high on the global agenda. Qatar Foundation’s Education City, also the location of one of the main stadiums in the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022, is one manifestation of this. This study is based on a survey that explores and compares the experiences of people with and without disabilities in their interactions with Education City and the legacy of the FIFA World Cup. It found that people’s experiences and feelings of social inclusion were positive given multiple inclusive programs hosted by Education City and that FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022 accelerated this shift.

Yet, there is still room for improvement in the availability and quality of facilities; services with trained staff; clear communication and advertisement; as well as raising awareness and institutionalizing policies that reduce discrimination and stigma and normalize people with disabilities in all spheres. These findings corroborate the vast majority of studies on social inclusion for people with disabilities (Bokányi et al. 2021; de Oliveira Neto et al. 2020; Louw et al. 2019; Overmars-Marx et al. 2014). The key recommendations are therefore to work on removing these barriers and instilling a process of monitoring and evaluation, all in conjunction with local experts and people with disabilities. At the time of writing this paper, Qatar Foundation took on this recommendation and has already established several coordination mechanisms, including the Autism Task Force and the Inclusion Working Group, towards this end.

This study offers important insights into the intersection of social inclusion and urban planning, particularly in understudied regions. As more countries are attempting to fulfill their sustainability pledges, this study would prove useful for policy makers and urban planners. We hope that this contributes to a future of urban planning where social sustainability is normalized and therefore embedded in its initial design rather than an afterthought.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.-W.; formal analysis, K.C.; data curation, S.A.-W. and J.D.; writing—original draft, H.A. and E.T.; writing—review and editing, S.A.-W., J.D. and E.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

National Priorities Research Program #12C-0804-190009, entitled SDG Education and Global Citizenship in Qatar: Enhancing Qatar’s Nested Power in the Global Arena, from the Qatar National Research Fund (a member of Qatar Foundation).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | For more on education in Qatar overall and education for sustainability see (Al-Jayyousi et al. 2023; Amin and Cochrane 2023; Amin et al. 2023; Romanowski et al. 2023; Sellami et al. 2025). |

References

- Al-Jayyousi, Odeh, Hira Amin, Hiba Ali Al-Saudi, Amjaad Aljassas, and Evren Tok. 2023. Mission-oriented innovation policy for sustainable development: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 15: 13101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shaqab. (n.d.) Equine Education. Available online: https://alshaqab.com/en/equine-education (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Amin, Hira, Alina Zaman, and Evren Tok. 2023. Education for sustainable development and global citizenship education in the GCC: A systematic literature review. Globalisation Societies & Education 2023: 2265846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Hira, and Logan Cochrane. 2023. The development of the education system in Qatar: Assessing the intended and unintended impacts of privatization policy shifts. British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 51: 1091–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Hira, Khoulood Sakbani, and Evren Tok. 2024a. State Aspirations for Social and Cultural Transformations in Qatar. Social Sciences 13: 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Hira, Leena Badran, Ayelet Gur, and Michael. Ashley Stein. 2024b. The experiences of Palestinian Arabs with disabilities in Israel. Equality Diversity & Inclusion 43: 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmus, Jennifer M., Erik W. Carter, Colleen K. Moss, Elizabeth E. Biggs, Daniel M. Bolt, Tiffany L. Born, Kristen Bottema-Beutel, Matthew E. Brock, Gillian N. Cattey, Molly Cooney, and et al. 2017. Efficacy and social validity of peer network interventions for high school students with severe disabilities. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 122: 118–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, Leena, Ayelet Gur, Hira Amin, and Michael. Ashley Stein. 2023a. Self-Perspectives on Marriage Among Arabs with Disabilities Living in Israel. Journal of Family Issues 44: 2799–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, Leena, Hira Amin, Ayelet Gur, and Michael Ashley Stein. 2023b. “It’s Disgraceful Going through All this for Being an Arab and Disabled”: Intersectional and Ecological Barriers for Arabs with Disabilities in Israel. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 25: 212–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, Leena, Hira Amin, Ayelet Gur, and Michael Ashley Stein. 2024a. ‘I am an Arab Palestinian living in Israel with a disability’: Marginalisation and the limits of human rights. Disability & Society 39: 1901–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, Leena, Hira Amin, Ayelet Gur, and Michael Ashley Stein. 2024b. ‘I had the full support of my family! This family support tops everything else’: Facilitators for Arabs with disabilities in Israel to lead meaningful, independent, and dignified lives by applying self-efficacy theory. The British Journal of Social Work bcae187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigby, Christine, Sian Anderson, and Nadine Cameron. 2018. Designing Effective Support for Community Participation for People with Intellectual Disabilities. Available online: https://apo.org.au/node/312547 (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Bokányi, Eszter, Sandor Juhász, Marton Karsai, and Balazs Lengyel. 2021. Universal patterns of long-distance commuting and social assortativity in cities. Scientific Reports 11: 20829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bota, Aura, Silvia Teodorescu, and Sorin Şerbănoiu. 2014. Unified Sports—A social inclusion factor in school communities for young people with intellectual disabilities. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 117: 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramley, Glen, Nicola Dempsey, Sinead Power, and Caroline Brown. 2016. What is ‘Social Sustainability‘, and How Do Our Existing Urban Forms Perform in Nurturing It. Paper presented at the Sustainable Communities and Green Futures Conference, Chennai, India, December 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Brauer, Eden, Kristen Choi, John Chang, Yi Luo, Bruno Lewin, Corrine Munoz-Plaza, David Bronstein, and Katia Bruxvoort. 2021. Health care providers’ trusted sources for information about COVID-19 vaccines: Mixed methods study. JMIR Infodemiology 1: e33330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CBM. 2019. The Inclusion Imperative: Towards Disability-Inclusive and Accessible Urban Development-Key Recommendations for an Inclusive Urban Agenda. Punat: CBM. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Tzuhao, J. Ramon Gil-Garcia, and Mila Gasco-Hernandez. 2022. Understanding social sustainability for smart cities: The importance of inclusion, equity, and citizen participation as both inputs and long-term outcomes. Journal of Smart Cities and Society 2: 135–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Kei Long, Peter M. ten Klooster, Cees Smit, Hein de Vries, and Marcel E. Pieterse. 2017. The impact of non-response bias due to sampling in public health studies: A comparison of voluntary versus mandatory recruitment in a dutch national survey on adolescent health. BMC Public Health 17: 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, Logan, Hira Amin, and Nouf Al-kaabi. 2024. National identity in Qatar: A systematic literature review. Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 24: 145–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crist, John T. 2015. Innovation in a Small State: Qatar and the IBC Cluster Model of Higher Education. The Muslim World 105: 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Neto, João Soares, Sergio Takeo Kofuji, and Yolaine Bourda. 2020. People with disabilities’ needs in urban spaces as challenges towards a more inclusive smart city. Paper presented at the Information Technology and Systems: Proceedings of ICITS 2020, Bogots, Colombia, February 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, Tracey J., Simon Darcy, Raechel Johns, and Caitlin Pentifallo. 2016. Inclusive by design: Transformative services and sport-event accessibility. The Service Industries Journal 36: 532–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donn, Gari, and Yahya Al Manthri. 2013. Education in the Broader Middle East. Providence: Symposium Books. [Google Scholar]

- Eizenberg, Efrat, and Yosef Jabareen. 2017. Social Sustainability: A New Conceptual Frame. Sustainability 9: 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Akoum, M., and M. Dyer. 2022. Accessible by Design: Building a Legacy of Inclusion. Rayyan: World Innovation Summit for Health. [Google Scholar]

- El Akoum, Maha, Neil Moors, Diedre Thompson, Ryan Moignard, and Kathleen Bates. 2023. Road to success: Lessons from the Qatar Foundation Ability Friendly Program. BMJ Innovations 9: 109–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FIFA. 2023. Accessibility at the Tournament. Available online: https://publications.fifa.com/en/final-sustainability-report/social-pillar/accessibility/accessibility-at-the-tournament/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Grills, Nathan, Lawrence Singh, Hira Pant, Jubin Varghese, Gvs Murthy, Monsurul Hoq, and Manjula Marella. 2017. Access to Services and Barriers faced by People with Disabilities: A Quantitative Survey. Disability, CBR & Inclusive Development 28: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzi, Martin, and Pablo de Pedraza García. 2015. A web survey analysis of subjective well-being. International Journal of Manpower 36: 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemani, Shruti, A. Kumar Das, and Anirban Chowdhury. 2017. Influence of urban forms on social sustainability: A case of Guwahati, Assam. Urban Design International 22: 168–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inside-Fifa. 2023. One Month On: 5 Billion Engaged with the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022. Available online: https://inside.fifa.com/tournaments/mens/worldcup/qatar2022/news/one-month-on-5-billion-engaged-with-the-fifa-world-cup-qatar-2022-tm (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Kamrava, Mehran. 2015. Qatar: Small State, Big Politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kart, Ayse, and Mehmet Kart. 2021. Academic and social effects of inclusion on students without disabilities: A review of the literature. Education Sciences 11: 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korngold, David, Martin Lemos, and Michael Rohwer. 2017. Smart Cities for All: A Vision for an Inclusive Accessible Urban Future. Washington: AT&T. [Google Scholar]

- Louw, Julia S., Bernadette Kirkpatrick, and Geraldine Leader. 2019. Enhancing social inclusion of young adults with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review of original empirical studies. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 33: 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGillivray, David, Gayle McPherson, and Laura Misener. 2018. Major sporting events and geographies of disability. Urban Geography 39: 329–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milot, Élise, Romane Couvrette, and Marie Grandisson. 2021. Perspectives of adults with intellectual disabilities and key individuals on community participation in inclusive settings: A Canadian exploratory study. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability 46: 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Martin. 2015. The mega-event syndrome: Why so much goes wrong in mega-event planning and what to do about it. Journal of the American Planning Association 81: 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overmars-Marx, Tessa, Fleur Thomése, Manon Verdonschot, and Herman Meininger. 2014. Advancing social inclusion in the neighbourhood for people with an intellectual disability: An exploration of the literature. Disability & Society 29: 255–74. [Google Scholar]

- QF. (n.d.a) About US. Available online: https://www.qf.org.qa/about (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- QF. (n.d.b) Education City in Qatar. Available online: https://www.qf.org.qa/education/education-city (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- QF. (n.d.c) Top Five Facts You Need to Know About Education City Stadium. Available online: https://www.qf.org.qa/stories/tap/top-five-facts-you-need-to-know-about-the-education-city-stadium#prev-item (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Rahman, Md Mizanur, and Amr Al-Azm. 2023. Social Change in the Gulf Region: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Rebernik, Nataša, Marek Szajczyk, Alfonso Bahillo, and Barbara Goličnik Marušić. 2020. Measuring Disability Inclusion Performance in Cities Using Disability Inclusion Evaluation Tool (DIETool). Sustainability 12: 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanowski, Michael H., Evren Tok, Tasneem Amatullah, Hira Amin, and Abdellatif Sellami. 2023. Globalisation, policy transferring and indigenisation in higher education: The case of Qatar’s education city. Journal of Higher Education Policy Management 46: 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schur, Lisa, Lisa Nishii, Meera Adya, Douglas Kruse, Susanne M. Bruyère, and Peter Blanck. 2014. Accommodating employees with and without disabilities. Human Resource Management 53: 593–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellami, Ikram, Hira Amin, Ozcan Ozturk, Alina Zaman, Seda Duygu Sever, and Evren Tok. 2025. Digital, localised and human-centred design makerspaces: Nurturing skills, values and global citizenship for sustainability. Discover Education 4: 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, Sabika, and Hira Amin. 2023. The disability price tag: The economic costs of caring for children with disabilities in Qatar. Doha International Family Institute Journal 2023: 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, Sabika, and Hira Amin. 2024. Childhood disabilities and the cost of developmental therapies: The service provider perspective. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being 19: 2345816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shogren, Karrie A., Judith M. S. Gross, Anjali J. Forber-Pratt, Grace Francis, Allyson L. Satter, Martha Blue-Banning, and Cokethea Hill. 2015. The perspectives of students with and without disabilities on inclusive schools. Research and Practice for Persons With Severe Disabilities 40: 243–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Simon, Paul Bellaby, and Sally Lindsay. 2010. Social inclusion at different scales in the urban environment: Locating the community to empower. Urban Studies 47: 1439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stace, Hilary. 2015. Disability as a Wicked Policy Problem. Public Address. May 12. Available online: https://publicaddress.net/access/disability-as-a-wicked-policy-problem/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Tucker, Emily C., Jennifer L. Jones, Kami L. Gallus, Sam R. Emerson, and Amber Manning-Ouellette. 2020. Let’s take a walk: Exploring intellectual disability as diversity in higher education. Journal of College and Character 21: 157–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCRPD. 2006. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. United Nations General Assembly. Available online: https://wwda.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/convention_accessible_pdf.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- UN-Habitat. 2016. New Urban Agenda. Paper presented at the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development, Quito, Ecuador, October 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. 2017. Habitat III Policy Papers: Policy Paper 1 The Right to the City and Cities for All; New York: United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development. Available online: https://habitat3.org/the-new-urban-agenda/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Vallance, Suzanne, Harvey C. Perkins, and Jennifer E. Dixon. 2011. What is social sustainability? A clarification of concepts. Geoforum 42: 342–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO, and World Bank. 2011. World Report on Disability 2011. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, Stephen, and Jeroen Huisman. 2012. The international branch campus as transnational strategy in higher education. Higher Education 64: 627–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Nathan J., Hayden Jaques, Amanda Johnson, and Michelle L. Brotherton. 2016. From social exclusion to supported inclusion: Adults with intellectual disability discuss their lived experiences of a structured social group. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 30: 847–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).