Abstract

The rise of radical right-wing parties in Europe brings new dynamics and challenges to western liberal democratic models, particularly in how these parties construct narratives around minorities, often framing them as threats to national identity and security. Given the historical background of populist governments in Italy and Portugal being, until recently, an exception in the context of populism in Europe, the comparison between these two countries offers an opportunity to analyse the dynamics and impacts of radical right-wing populism in both countries. The present research aims to address the scarcity of studies on social representations of minorities in Portugal and Italy. To achieve this goal, we conducted a survey (N = 1796) in Portugal and Italy. Using the free word association technique, based on Abric’s Structural Approach to Social Representations Theory, we analyse responses regarding social representations of minorities. Our findings reveal that, while respondents in both nations acknowledge discrimination, the Italian sample includes a wider range of negative terms, such as “violent”—whereas the Portuguese sample largely portrays minorities in positive terms, favouring their inclusion. Respondents in both countries recognise the existence of discrimination against minorities in society, yet the evocation of terms such as “violent”, “profiteers”, and “repugnant” reflects considerable influence from exclusionary and marginalising narratives.

1. Introduction

There has been a rise in radical right-wing populist parties in Western Europe, a phenomenon that has affected the liberal democracies of the 21st century (The Economist Intelligence Unit 2023). The rapid growth of radical right political parties across Europe is an example of the populist phenomenon, both in terms of ideology and political narratives (Galhardas 2023). As an example, the 2024 European Elections were marked by a significant increase in radical right parties in several European countries. In Portugal, CHEGA, considered a radical right-wing party, entered the European Parliament while in Italy Fratelli d’Italia won a relative majority of seats. This growth of radical right-wing parties has put several sensitive issues at the centre of public debate, such as anti-immigration discourse, anti-minorities and patriotism (Krzyżanowski and Ledin 2017). Despite being a phenomenon that cuts across most European countries, this research will focus on comparing the rise of radical right populist parties in Portugal (until recently seen as an exception in European populism (Salgado and Zúquete 2017)) and Italy, a country whose past is marked by the influence of several populist parties (Blokker and Anselmi 2019).

This paper looks at the concept of populism from the perspective of Mudde (2004) and Laclau (2005). These perspectives converge on anti-elitism, which refers to the division between the people and the elite, indicating a centrality in the distinction between “those below” and “those above” (Ostiguy 2020). Although populism is often associated with nationalism, studies show that the people that populists claim to represent is not necessarily identical to the nationalist notion, but rather of an oppressed people (Wojczewski 2020). Populist leaders instrumentalise society’s feelings of revolt to challenge the legitimacy of the political entity (Abts and Rummens 2007). The discourse employed by populist leaders tends to create scapegoats who are blamed for society’s current woes (Wodak 2015), adopting nativist notions. In other words, it establishes an explicit preference for members of the native group and rejects those perceived as foreign (Mudde 2021). This type of populism is characterised by the exclusion of all those who are not considered pure in the process of characterising and constructing the people (Mudde 2004) and promotes manichean us vs. them narratives, placing minorities as the others, who play a threatening role to social cohesion and national security (Wodak 2015). It is in this sense that it is worth focusing on social representations as a set of ideas and beliefs created in everyday life and in communicative processes, serving to interpret and make sense of the world (Parreira et al. 2018), by considering the concept of nativism, since they influence the way social groups perceive and react to ideas of identity and belonging.

Guiding this paper is the question: What are the social representations of minorities in countries like Italy and Portugal, which have experienced a right-wing shift, and to what extent do factors such as age, gender, political orientation, and education influence these representations? In addition, we aim to investigate whether social representations vary according to gender and age class. To this end, we conducted a survey in Portugal (N = 906) and Italy (N = 890) and adopted a qualitative method, using the free word association technique, through Structural Approach to Social Representations Theory according to Abric (1976).

In the next two sections this article will examine the most relevant theories of populism in relation to minorities, followed by an analysis of the populist upsurges in Italy and Portugal. It will then contextualise Social Representations Theory before introducing the materials and methods, as well as the data and analysis. The main findings indicate that, in both samples, social representations primarily reflect the perception that minorities are discriminated against. However, they also reveal that minorities are subject to prejudice, particularly the notion that they are violent.

1.1. Populism

It is difficult to give a concrete definition of populism, as it has been applied to various historical phenomena over time (Caiani 2022). Furthermore, within the scientific community there is no concrete and consensual definition of this phenomenon. Thus, this paper will focus on the advantages presented by Cas Mudde’s (2004) ideational approach in conjunction with Laclau’s (2005) formal-discursive contribution.

An emerging consensus in the literature regarding the various conceptualisations of populism is the identification of two opposing groups: the corrupt elite and the pure people (Mudde 2004). Populism can be seen as a fragile political ideology that seeks to divide society into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups: the pure people and the corrupt elite. The central concept in populism is therefore the people (Canovan 1999), portrayed as a source of virtue and power, in contrast to the elite, unconcerned with the interests of the people. Mudde’s vision of populism entails a superficial nature, with a limited core and a restricted set of associated political concepts. In this sense, populism tends to focus on simple issues, related to the opposition between the people and the elite, without addressing political and social issues in a comprehensive manner. Populism is thus described as a thin-centred ideology, i.e., its ideological base is narrow, implying that it can be easily adapted to different contexts and political agendas.

A critical view of populism focuses on its formal and discursive characteristics. Laclau (2005) considers that populism involves the performative and discursive construction of diverse political identities with specific social demands that coalesce (forming a chain of equivalences between them) around an empty signifier, thus constituting the people that opposes an elite constructed in an antagonistic relationship. In this sense, populism is a political logic that characterises the very core and essence of democratic action and refers to an inherent rationality (form) behind its discursive construction. The dialogue between the Muddean and Laclauian schools reveals a point of contact in anti-elitism that refers to the construction and binary division between people and elite. This dual nature of populism, although with different perspectives on what consists of the people and the elite, points to a centrality in the distinction between “those below” and “those above”) (Ostiguy 2020, p. 33), reflecting a dynamic of inclusion and exclusion that is fundamental to populist mobilisation. While Mudde highlights a more structured approach to the categorisation of the people and the elite, Laclau emphasises the fluidity and contingency of the signifiers that discursively constitute these categories. Building on Laclau and Mouffe (2001) discourse here is understood not merely as a linguistic construct but as something material and an encompassing realm that includes societal institutions, structures, and norms. Far from being secondary or derivative, discourse is constitutive, in that individuals, groups, classes, and identities are formed through discourse. Accordingly, discourse is not just a reflection of reality; it is actively and performatively shaping reality. Within this framework, a Laclaudian approach to populism takes a post-foundational stance (Thomassen 2024), suggesting that populist discourse actively creates the very entity it purports to represent—the people (Thomassen 2024). When populist actors speak in the name of the people, they are also performatively constituting that people. In line with Laclau’s formal perspective on populism, there is no specific content that defines populist discourse per se. This holds true for Mudde’s (2004) idea of a moral people and their volonté générale, as well as the authoritarian and nativist dimensions typically associated with radical right-wing populism (Mudde 2007). Rather, it is a particular discursive form—a logic—that demarcates a discourse as populist (Laclau 2005; Thomassen 2024), regardless of its substantive content.

As can be seen, there is a significant amount of discord between Laclau and Mudde over whether “the people” possess any fixed, ontological status. Mudde’s ideational approach attributes a moral essence not only to the people (virtue) but also to the elites (corruption). Laclau, however, views both the people and the elites as hegemonic constructs lacking any ontological primacy, highlighting the contingency of populist articulations. Despite this divergence, both perspectives acknowledge that populism delineates an antagonistic frontier between an underdog populace and an established elite.

1.2. Minorities and Populism

Society is necessarily composed of stratified and hierarchical groups (Schermerhorn 1970). There is a paradigm of power that determines which groups in a society are dominant or inferior. If a group has power and is numerous, it is a majority; if a group has power but is not numerous, it is the elite; if a group has neither power nor is numerous, it is a minority. In this sense, minorities represent the differences that exist in society, and it is an important aspect in the construction of their identity.

Minority is a social categorisation used to complexify the degree of social differences that various groups experience in relation to a dominant group. Minorities can be defined as population groups that are perceived as separate from the rest of society due to socio-demographic characteristics such as ethnicity, sexuality and religion (Indelicato 2022). The characteristics that define ethnic minorities can vary from group to group and context to context and may not coincide with individual perceptions. Barth (1969) developed the view that ethnicity is used as a sign of cultural difference, which defines social barriers. In this sense, an ethnic group represents itself not only as distinct from other groups, but with specific characteristics that allow it to identify with those groups. Ethnicity is a relational identity, but it is an ambivalent relationship, in that constructs of difference and shared identity coexist (Harrison 2003). From Yinger’s (1986) perspective the socio-cultural barriers that define ethnic groups must be visible and tangible.

Minorities are often targeted by populist parties of the radical right. In this way, populism, associated with radical right-wing political ideology, generates exclusionary views, by constructing impure outgroups, in contrast with the pure people (Mudde 2004). Populism, in this case, can be seen as a construct fundamentally at odds with liberal democracy due to its anti-pluralist character, as it defends the belief in cultural homogeneity. While democracy depends on an acceptance of diversity and the protection of the rights of all citizens, radical right-wing populism promotes a simplified and polarising vision of society, which can lead to exclusion, the erosion of democratic institutions and the rise of authoritarianism. Considering that radical right populist actors see multiculturalism as a threat to national identity and social cohesion, it’s not surprising that their response to the complexities of an increasingly pluralistic society is a rejection of multiculturalism (Indelicato and Magalhães Lopes 2024). Radical right-wing populism assumes that multiculturalism contributes to the weakening and denial of the shared values and traditions that unite the nation (Mudde 2021) which gives rise to nativism. Contemporary nativism involves an explicit preference for members of the native group and the rejection of those who are perceived as foreign or non-native (Mudde 2021). Thus, the us vs. them narrative is often promoted, characterising minority groups as threats to social cohesion and national security (Wodak 2015). This view tends to construct scapegoats or enemies—the Others—who are blamed for society’s current problems, often drawing on traditional collective prejudices and stereotypes. Thus, the others are foreigners, defined by race, ethnicity, religion, sexuality or language (Wodak 2015). The construction of a pure nation involves the use of politics based on fear and hatred, often directed against minorities. By exploiting these two elements, radical right populist leaders seek to strengthen their support among elements of the population that feel insecure or marginalised, stimulating polarisation and weakening social cohesion (Galhardas 2023). This emphasis on exclusive identities and authoritarian tendencies directly influences how radical right populist movements perceive and treat minority groups. By promoting a vision of democracy rooted in exclusion rather than inclusion, these political cultures reinforce the divide between those who belong and those who are deemed as outsiders. Their emotional narratives encourage conceptions of democracy based on exclusivity, which favours centralisation, authoritarianism, and state securitisation over innovation and public participation (Gianolla et al., 2024).

1.3. Populist Movements in Portugal and Italy

In Italy, a crisis of political parties emerged, which reached its peak with a corruption scandal called “Tangentopoli” (1993–1994) (Rhodes 2015). As a result, there was a rise in populist movements, coinciding with the aftermath of the fall of the Berlin Wall (Lanzone 2014). This contemporary Italian populism has its roots in the creation of regional leagues in the late 1980s like Bossi’s Lega Nord (LN) in 1991. The LN party emerged as a consequence of the coalition of regional movements in affluent northern Italy. These movements were united by a sense of localism and a perception of dissatisfaction with the state bureaucracy, which they alleged to have been usurped by the southern ‘parasites’ (Bulli and Tronconi 2012). Under Bossi’s leadership, the party developed a clear populist distinction between the pure people (of the North) and the corrupt elites (in the Capital). The party underwent a shift in its ideological orientation towards nationalism in 2013, under the leadership of Matteo Salvini. This transformation marked a departure from its previous regionalist stance and a shift towards a more nationalistic perspective (Passarelli and Tuorto 2022). The initial success of LN coincided with and contributed to the fall of the “First Republic”, characterised by the old mass parties. LN formed an alliance for the 1994 elections with Forza Italia (FI) and, together with Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI) (which soon after the elections became Alleanza Nazionale (AN)), entered Berlusconi’s first centre-right government. In 1993, with the end of the “First Republic”, almost all the old parties disappeared or renewed themselves, and the power vacuum was filled by a new party: “Forza Italia” (FI), founded and led by Silvio Berlusconi (Lanzone 2014), with a people centrist and anti-establishment political discourse (Maccaferri 2022). The consolidation of Berlusconi-Bossi’s populism paved the way for a new anti-system movement years later, like Grillo’s Movimento Cinque Stelle (M5S). What unites these movements is the articulation of populist demands, such as anti-elitism and national sovereignty, although their associated ideologies differentiate them. It is in this context that Fratelli d’Italia (FdI, led by Giorgia Meloni) emerged, a party founded in 2012 by dissidents from Il Popolo della Libertà (PdL) who had previously been active in the M5S and AN.

The last decade has seen the influence of populist parties on the Italian political landscape. In the 2013 parliamentary elections, half of Italian voters voted for parties labelled populist, such as Berlusconi’s PdL, Salvini’s LN and Grillo’s M5S. Italy, unique in Europe, had four coalition governments of populist parties between 1994 and 2011 (Verbeek and Zaslove 2016). Meanwhile, the FdI, a radical right-wing party with neo-fascist roots, increased its representation in parliament, culminating, in September 2022, in a legislative electoral victory, forming a coalition government with the LN and FI. This is the most right-wing Italian government since World War II (Expresso 2023; SIC Notícias 2022).

According to Verbeek and Zaslove (2016), there are three reasons for the reaction to populism in Italy. Firstly, Italian populism has been partly functional for democracy, having helped to bring down the “First Republic”. Secondly, populism ends up being a reaction to populism itself, as the FI reacted to the success of the LN and the M5S challenged the populism of these two parties. Finally, the anti-populists seek to oppose populist policies and ideas, but they face various populist parties with different facets. Thus, despite their ideological differences, these parties share opposition to the established political elite, which can make it challenging for anti-elitists to formulate an effective strategy to confront them. However, all these parties constitute new elites which, in part, incorporate the previous ones. This is how Laclauian theory is necessary to understand populism as an articulation of political and social demands that represent dissatisfaction with emerging or reformulated leaderships.

In contrast, the so-called “Portuguese exception” in Europe has often been explained by the collective memory of Salazar’s dictatorship under the Estado Novo regime until 1974, which contributes to the stigmatisation and repudiation of radical right-wing ideas (Salgado and Zúquete 2017). This cultural resistance created a less favourable environment for such movements to flourish. According to Quintas Da Silva (2018) three main factors hindered the success of radical right ideologies in Portugal: (1) widespread identification with European Union ideals, (2) comparatively lower immigration rates than other EU states, and (3) the historically poor communication skills of radical right candidates during electoral campaigns. Additionally, left-wing parties—such as the Communist Party (PCP) and Left Bloc (BE)—have long acted as aggregators of popular discontent, absorbing some of the protest potential that might otherwise be channeled into more extreme right-wing populist ventures (Salgado and Zúquete 2017). Over time, this interplay of collective memory, established left-wing organisations, and low-profile radical right communication strategies has contributed to an enduring perception that Portugal was uniquely resistant to populist movements.

Despite this, Portuguese politics and media, especially, have not been entirely devoid of populist elements. As Salgado and Zúquete (2017) note, populism often carries a negative connotation in Portuguese public discourse, with politicians and journalists alike employing the term “populist” to delegitimise rivals or policies they deem oversimplified or opportunistic. Historically, mainstream media have offered minimal coverage of extreme right-wing voices, generally portraying them as remnants of the authoritarian regime (Salgado and Zúquete 2017).

This perceived “Portuguese exceptionality” was, however, challenged by the emergence of CHEGA in 2019, a party led by André Ventura. That year, CHEGA won a single seat in the Assembly of the Republic—its first entry into the Portuguese Parliament. Five years later, in 2024, the party expanded its representation to fifty seats, indicating a considerable electorate receptive to radical right-wing populist messages (Santana-Pereira and Cancela 2020). Several factors account for CHEGA’s rise, including broad dissatisfaction with traditional elites, growing concern over immigration and security, frustration with political and economic corruption, and adept use of social media to amplify nationalist and populist sentiments (Biscaia and Salgado 2022; Jaramillo 2021). In his public addresses, Ventura frequently divides society into “good Portuguese” versus outsiders, castigates corruption, and singles out minorities. In particular, he blames Roma communities for contributing to the “mass invasion” of immigrants from southern Mediterranean countries (Jaramillo 2021; Prior and Andrade 2025). By emphasising national identity and “traditional” Portuguese values, CHEGA frames multiculturalism as a threat to Portugal’s cultural heritage (Prior and Andrade 2025).

Insofar as CHEGA’s discourse resonates with a portion of the electorate, it signals that Portugal may no longer be as immune to radical right populism as once perceived. The party’s success underscores that core elements of the populist style can find fertile ground even in contexts where historical memory and left-wing protest channels once seemed to foreclose such possibilities. Populist anti-elitism, the juxtaposition of an idealised “people” against a corrupt establishment, and emotional appeals to national sentiment have proven particularly effective in Portugal. Thus, while the country’s unique legacy and political culture have shaped a more resistant public sphere, CHEGA’s ascendance calls into question whether Portugal’s populist “exception” can endure the evolving demographic and political conditions.

1.4. Social Representations Theory

The Theory of Social Representations, created by Moscovici in 1961, is an explanatory theory of common sense. Moscovici (1986) considers that social representations arise because of interactions and that different interactions give rise to different representations. However, representations cannot be considered a reflection of reality, but rather a meaningful organisation that depends simultaneously on the situational context and the social and ideological context. Thus, representations act as systems of interpretation of reality, which define the relationship of individuals with the physical and social context and their behaviour in that context (Parreira et al. 2018). In general, definitions of social representation reflect an aspect that results from attempts to produce meaning, which we use to communicate and guide our behaviour to live in society. The two fundamental processes that underpin social representations are objectification and anchoring. Objectification refers to the way in which the elements of representations are organised and the way in which these elements become expressions of a reality that is thought of as natural and analyses the way in which a concept is thought of objectively (Vala 2000). Anchoring refers to the way in which new objects are associated and framed in pre-existing representations, being the social instrumentalisation of the represented object (Vala 2000). The process of objectification correlates with that of anchoring to form an object classification system that influences the behaviour of individuals (Moscovici 1986). It can be said that social representation is organised around a core which, in a way, acts as the underlying basis for all the images, beliefs or judgements created by a group or society over time (Moscovici 1986).

Abric (1976) with his Structural Approach to Social Representations, considers social representations to be a set of beliefs, opinions and behaviours that form a cognitive system made up of two subsystems that interact with each other, a central core and a peripheral core (Abric 2001). The central core refers to collective thought, being stable and resistant to change (Machado and Aniceto 2010) and constitutes the common and shared basis of social representation (Mónico et al. 2019). The peripheral core is more individual, flexible, open to change and exposes personal modulations in relation to the common central core (Abric 1993).

According to Moscovici (2011) the theory of social representations is useful for understanding the relationship between minorities and the majority. A group is formed by external characteristics and from beliefs and theories that anticipate its initial state of development. This can explain why society categorises its members, defining differences between majorities and minorities, based on popular beliefs, religious or political rituals. These are representations that follow norms with an ethical meaning. The most distinctive feature of a minority lies in the central core of its representation (Moscovici 2011). The central core of a minority, which is associated with the social representation of that minority, is represented in what is said or thought about that group. One of the main ideas in relation to minorities is the concept of pure/impure, which characterises minorities as a group divergent from the rest of society (Mudde 2004). Another idea is stigma, which differentiates minorities and praises the majority. Stigma is not just a mark of the minority, but a way of thinking that replaces symbolic thinking, where stigmatised people belong to a persecuted minority (Moscovici 2011). These ideas partly shape social representations and precede the development of relations between minorities and majorities in contexts of ethnic and religious persecution and other forms of oppression (Moscovici 2011).

2. Materials and Methods

The qualitative method used in this research is based on the Structural Approach of the Theory of Social Representations, formulated by Abric (1976). The free word association technique was used, based on Jung’s Word Association Test (Petchkovsky et al. 2013).

The free word association technique is an open method in which a stimulus (words or expressions that are part of the subject’s linguistic universe) induces the production of words or terms that emerge by free association. It is part of the associative methods that use verbal expressions collected more spontaneously, which makes it more authentic, without prior contamination by the researcher’s discourse.

This technique is used in studies on social representations (structural approach) and makes it possible to understand the organisation of content by identifying its structure of representation (central core, contrasting core and peripheral elements). It focuses on the internal structure of social representations and seeks to understand how the elements of these representations are organised and hierarchised. Abric’s proposal (Abric 1993, 1994a, 1994b, 1997) is considered appropriate because it allows for the spontaneous (and therefore less controlled) nature of the evocation, with the aim of capturing a projective dimension of the elements of this evocation that make up the semantic universe of the term or object studied.

Using this technique allows access to implicit elements that would otherwise be lost in the subjects’ discursive productions (Abric 2001). By analysing the content of free recall, we can identify the content, structure and organisation of the social representations of minorities. To understand whether the political orientation, gender and age of the respondents have an influence on social representations, we will use the same technique, analysing the central nuclei. Through this technique, with a simple and direct indication, the participant can express what they think and believe about the object (Abric 2001) avoiding biases that can arise when the researcher provides a prior selection of words.

2.1. Sample

The sample of this research includes individuals living in Portugal (n = 906) and Italy (n = 890), or nationals of these countries in 2022, all of whom were over 18 years of age (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characterisation of the Portuguese and Italian samples.

2.2. Ethical and Formal Procedures

To collect data, participants were instructed to answer a questionnaire prepared by the research team from UNpacking POPulism: Comparing the formation of emotion narratives and their effects on political behaviour hosted by the Centre for Social Studies, University of Coimbra (CES-UC).

Participants in Portugal were recruited by distributing a questionnaire via a link and by instructing students of the Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences of the University of Coimbra to distribute the link. These students received specific instructions for distributing the questionnaire and collecting data, following a protocol established within the Research Methodology course. In Italy, the questionnaire was distributed by the company NETQUEST, Barcelona, Spain.

Throughout this study, all ethical principles were respected, and informed consent was obtained by the team in charge of data collection, guaranteeing participant anonymity and data confidentiality. In addition, participants were informed that there was no risk associated with their participation, and that they could stop answering the questionnaire at any time and their previous data would be deleted.

The questionnaire collected information on the social representations of Portuguese and Italian people, elites and minorities, as well as the emotions associated with these groups, using the Geneve Emotion Wheel (GEW) (Scherer et al. 2013). For this research, participants were instructed to answer the question: “Write down the first five words or short expressions that immediately come to mind when you think of ethnic minorities (e.g., romani, blacks, Muslims, etc.), in the order in which they come to mind.” Participants answered according to their country. Information was also collected on the participants’ political orientation, the party they were most sympathetic to, how they voted in the last elections or who they would have voted for, how they voted in elections prior to the last one, and their assessment of each of the parties running for Parliament on a scale of 0 to 10, including the option of not answering. In addition, sociodemographic information was recorded, such as age, level of education, current professional situation, and area of residence.

We analysed the data obtained from the question “Write down the first five words or short expressions that immediately come to mind when you think of ethnic minorities (e.g., Roma, black, Muslim, etc.), in the order in which they come to mind” to find out about the social representations of minorities in Portugal and Italy. In addition, we used sociodemographic information—namely gender, age group, and political orientation—to analyse how these variables impact representations.

2.3. Data Analysis

We first entered the words/short expressions into the Excel program and then into the EVOC (Ensemble de Programmes Permettant L’Analyse des Evocations) software (version 2005). Next, we reviewed the entire lexicographic corpus, with the aim of eliminating special characters from the words, inserting hyphens in expressions that contained more than one word (e.g., social-beneficiaries), due to limitations inherent in the software which does not process special characters and does not distinguish short expressions from single words. In addition, the review helped to maintain the spelling of synonymous words to unite them into a single term (Mónico et al. 2019). Finally, we created a categorisation of words that we considered to be synonymous, such as the terms “abused”, “removed”, and “apart” replaced by “discriminated”.

In this sense, it is important to take a closer look at how the categorisation was carried out. For example, the category “identity construction” refers to the characteristics of minorities that the participants evoked, such as “attitude”, “fair”, “vocal”, and the category “mistrust” indicates that minorities are a factor of mistrust, with words such as “alert”, “careful”, and “caution” being evoked.

Finally, the data were processed using EVOC, which reproduces the number of times a word or expression was used to characterise the object of study. The software calculates a frequency index for each word or expression mentioned, counting how many times each is evoked. The minimal frequency considered for analysis was 20. It also assigns a position index to each term, indicating in which order it was mentioned (position 1 for the first term mentioned, up to position 5 for the last term evoked). Combining these two indices gives a matrix of Four Houses or Four Quadrants, as proposed by Abric (1993). This matrix makes it possible to identify the possible elements of the central core, the contrast zone and the first and second peripheries.

EVOC is made up of sixteen tools which, although they perform different functions, contribute to statistical calculations and the construction of co-occurrence matrices, which serve as the basis for drawing up the four-house matrix (Machado and Aniceto 2010). For the purposes of this study, only four are relevant: Lexique, Trievoc, Rangmot and Rangfrq. Lexique creates a vocabulary of evocations; Trievoc separates the evocations and organises them in alphabetical order; Rangmot presents a list of all the words and expressions in alphabetical order, showing the frequency of each one, as well as the weighted average of the evocation order of each word and the total frequency and overall average of the evocation orders; finally, Rangfrq brings together, in a table with four quadrants, the elements that constitute the central core and the peripheries of the representations (Mónico et al. 2019).

The upper left quadrant of the four-house social representation matrix shows the central core, constituted with words characterised by having a higher frequency of evocations in a lower order, being more frequently evoked in the first positions (essentially 1st and 2nd place in the order of evocations). This core is constituted with the most relevant, stable and consensual terms of a social representation (Machado and Aniceto 2010). In the lower left quadrant are the terms that represent the contrasting core or mute zone, characterised by words that are evoked in first or second place, but with a low frequency, i.e., they are terms that are relevant to certain subgroups of the sample, but do not have the same centrality or universal consensus as the elements of the central core. On the right-hand side is the peripheral system of social representation, which is a strong indicator of possible future changes in social representation. In the upper right-hand quadrant is the first periphery, where frequently evoked terms are shown, but with more secondary evocation orders (terms evoked in third, fourth or fifth place), supporting the central system of social representations. Finally, in the lower right quadrant is the second periphery, where we find terms characterised by low frequency and more secondary evocation order (words evoked in the third, fourth or fifth positions), being the terms most susceptible to change and which play a role in the adaptation and flexibility of social representation (Abric 1993).

3. Results

As can be seen in Table 2, the Portuguese sample evoked 3458 words, 314 of which were unique, with an average order of evocation (A.E.O.) of 2.50 (from 1 to 5). The frequency (f) ranged from 1 to 628 evocations of the same word, and the word most evoked by the Portuguese population was “discriminated”. Table 1 shows the four-house matrix constructed using the EVOC software. In the first quadrant, which corresponds to the central core, the following 8 words appeared, including: “discriminated”, “racialised minorities”, “poor”, and “empathy”. In the contrasting nucleus, 13 terms were evoked, including: “cultural”, “injustice”, “hardworking”, and “not very hardworking”. Regarding the first periphery, there were 6 terms evoked, including: “violent”, “included”, “diversified”, and “fighters”. Finally, the second periphery is made up of 12 terms, including: “self-excluded”, “distrust”, “united”, and “religious”.

Table 2.

Matrix of the four houses of the Portuguese sample (N = 906).

As can be seen in Table 3, the Italian sample evoked 3190 words, 328 of which were single words, with an average evocation order of 2.50. The frequency varied between 1 and 378 evocations of the same word, and the word most evoked by the Italian population was “discriminated”. Table 2 shows the matrix of the four houses in the Italian sample. The central nucleus consisted of 11 words, including: “discriminated”, “violent”, “included”, and “racialised minorities”. In the contrasting nucleus, 12 terms were evoked, including: “hardworking”, “victims of racism”, “numerous”, and “indifferent”. In relation to the first periphery, 4 terms were evoked, including: “solidarity”, “rude”, “diversified”, and “distrust”. Finally, the second periphery is made up of 7 terms, including: “sympathetic”, “admirable”, “equality”, and “intolerable”.

Table 3.

Matrix of the four houses of the Italian sample (n = 890).

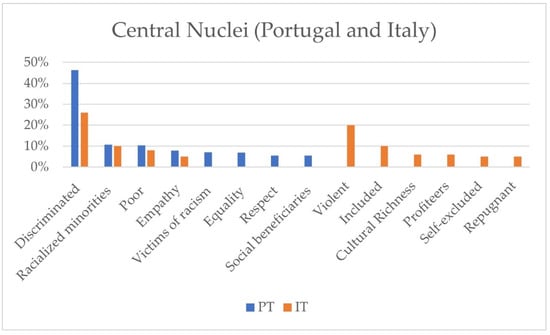

Figure 1 compares the central nuclei between Portugal and Italy, visually illustrating the similarities and differences presented in Table 2 and Table 3. Both samples place a strong emphasis on minorities who face discrimination, racialisation, deteriorating economic conditions, and a need for empathy. However, the Italian sample shows more ambivalent representations. In particular, Italian respondents associate minorities with violence, while simultaneously recognising their inclusion in Italian society and the cultural benefits they provide. At the same time, these groups are also portrayed as “profiteers” and “repugnant”. By contrast, Portuguese representations are generally more positive, highlighting minorities as victims of racism who require better conditions and greater respect.

Figure 1.

Social representations regarding minorities in Portugal and Italy.

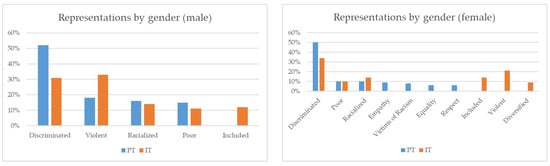

Table 4 and Figure 2 show the central nuclei of the Portuguese and Italian samples by gender. The most evoked word was “discriminated”, except for Italian men, who most frequently evoked “violent”. The Portuguese males’ central nucleus consists of the terms “discriminated”, “violent”, “racialised minorities”, and “poor”. The Italian male’s central nucleus included terms like “violent”, “discriminated”, “racialised minorities”, and “included”. The Portuguese female’s central nucleus included terms such as “discriminated”, “poor”, and “racialised minorities”. The Italian female’s core group includes terms such as “discriminated”, “violent”, and “included”.

Table 4.

Central core according to gender in the Portuguese and Italian samples.

Figure 2.

Representations by gender.

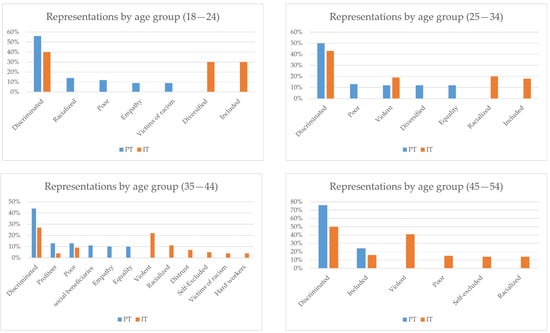

Table 5 and Figure 3 show the central nuclei of the Portuguese and Italian samples by age group. The most evoked word was “discriminated” in all age groups in both samples. The Portuguese sample aged between 18 and 24 presented a central nucleus with terms such as “discriminated”, “racialised minorities”, and “poor”. The Italian sample presented a central nucleus with the words “discriminated”, “diversified”, and “included”. The Portuguese sample aged between 25 and 34 presented a central core with terms such as “discriminated”, “poor”, and “diversified”. The Italian sample presented a core group with terms such as “discriminated”, “racialised minorities”, and “violent”. The Portuguese sample aged 45–54 presented a central nucleus that includes the terms “discriminated” and “included”. The Italian sample presented a central nucleus with terms such as “discriminated”, “violent”, and “included”.

Table 5.

Central core according to age group in the Portuguese and Italian samples.

Figure 3.

Representations by age group.

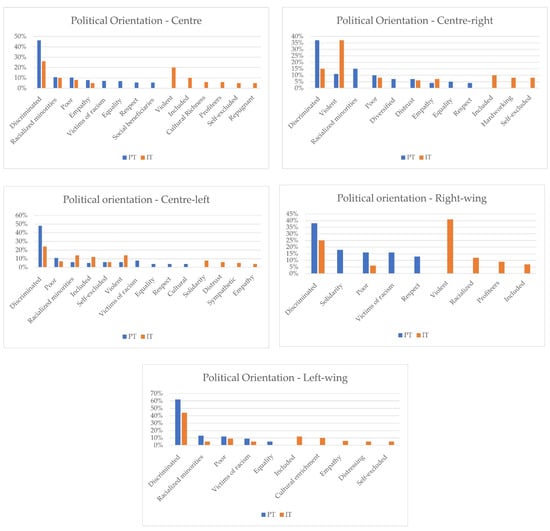

Table 6 and Figure 4 show the central nuclei of the Portuguese and Italian samples according to the political orientation of the respondents. The most evoked term was “discriminated”, except among Italian centre-right and right-wing respondents, who most frequently evoked “violent”. The Portuguese sample with a central political orientation presented a central nucleus that includes the terms “discriminated”, “violent”, and “poor”. The Italian sample presented a central nucleus that includes the terms “discriminated”, “rude”, and “mistrust”. The Portuguese sample with a centre-right political orientation presented a central nucleus that includes terms such as “discriminated”, “racialised minorities”, and “violent”. The Italian sample presented a central nucleus with terms such as “violent”, “discriminated”, and “included”. The Portuguese sample with a centre-left political orientation presented a central nucleus that includes terms such as “discriminated”, “poor”, and “victims of racism”. The Italian sample presented a central nucleus that includes terms such as “discriminated”, “violent”, and “racialised minorities”. The Portuguese sample with a right-wing political orientation presented a central nucleus with terms such as “discriminated”, “solidarity”, and “poor”. The Italian sample presented a central nucleus with terms such as “violent”, “discriminated”, and “racialised minorities”. The Portuguese sample with a left-wing political orientation presented a central nucleus that includes terms such as “discriminated”, “racialised minorities”, and “poor”. The Italian sample presented a central nucleus that includes terms such as “discriminated”, “included”, and “poor”.

Table 6.

Central core according to political orientation in the Portuguese and Italian samples (minimal f = 10).

Figure 4.

Central Nuclei by political Orientation.

4. Discussion

The overall comparison between the samples of Portugal and Italy demonstrates that the word most often evoked by participants was “discriminated”. This indicates that respondents have a significant perception of the injustice and inequality faced by minorities in both countries. Moreover, it suggests a broad awareness of discrimination and the social challenges experienced by minorities. The inclusion of terms such as “discriminated”, “poor”, “respect”, and “empathy” indicates a recognition of the need for equality and social justice in both countries. However, the presence of terms like “violent” may be a sign of radical right-wing party rhetoric, which uses political narratives that exclude minorities and reinforce negative stereotypes. However, the fact that there are terms like “respect” and “empathy” indicates that people also have a positive perception of minorities. Despite some positive perceptions, there is a predominance of negative feelings within the Italian sample towards minorities. This finding could be related to the sample heterogeneity of this study, but may also be justified by historical, cultural, economic, and political factors. These factors may include: the fascist legacy and nationalist policies (Lanzone 2014), the greater impact of migratory movements (Ambrosetti and Paparusso 2018), media narratives that amplify negative stereotypes (Caeiro 2019), crises and competition for jobs that highlight economic inequality (Ambrosetti and Paparusso 2018) and, finally, the discourses of radical right-wing parties that discourage the integration of minorities (Wodak 2015). On the other hand, results reveal a more positive view within the Portuguese sample. While negative stereotypes are firmly rooted in the central core of the Italian sample, the Portuguese sample shows greater diversity and flexibility in perceptions, with less central negative terms and a greater openness to recognising positive aspects of minorities. In the Portuguese sample, fewer terms have a negative connotation, which may indicate a more positive view of minorities, suggesting a lower tendency towards stigmatisation. This might be influenced by the political context, since immigration has only recently become an issue in the public debate, as well as the presence of more inclusive integration policies (Cunha 2010; Padilla and França 2020).

Regarding the first periphery, the terms evoked by both samples suggest that, even though initial perceptions may be more critical or stigmatising, the importance of solidarity and diversity is recognised. Furthermore, the presence of the term “diversity” as a frequent but not initial term indicates that society is aware of the benefits of diversity. It is in the second periphery that the Portuguese sample presents terms with a more negative connotation (“self-excluded”) than those evoked by the Italian sample (“sympathetic” and “admirable”). This suggests areas of social tension or prejudice, since the second periphery contains terms which, although not dominant, are significant enough to be mentioned.

Regarding gender, the analysis of the central nuclei based on sociodemographic data shows that, within the samples, women are more aware of social issues, showing concern for equality and respect. Females also have a less prejudiced or discriminatory attitude towards minorities. These results are in line with Neto’s (2007) study, which reported that women scored higher than men on the ethnic tolerance scale. Recent statistical data also showed a growing ideological discrepancy between the male gender (virtually stable) and the female gender (increasingly to the left), especially in the younger and more senior age groups (Saad 2024).

The age group between 18–24 also shows greater acceptance and neutrality, possibly due to growing up in more diverse and globalised environments. Such environments provide exposure to a greater variety of cultures and ethnicities, which can promote more inclusive views and mitigate stereotypes, as the studies by Janmaat and Keating (2019) and Maratia et al. (2023) point out. However, the term “violent” appears in the core group of people aged 25–34 in both countries and of people aged 48–54 in Italy. This could be because these groups have lived through the economic crises and the stigmatisation of migration (since 2015) in both countries and have absorbed stereotypes related to minorities (Ambrosetti and Paparusso 2018; Pellegrini et al. 2021). Within the 35–44 bracket, Portuguese responses tend to depict minorities as “discriminated” against yet also possibly dependent on public support (“profiteers” “social beneficiaries”), balanced by more inclusive notions like “empathy” and “equality”. Meanwhile, Italians in this age group show a stronger focus on “violence” and “racialisation”, reflecting more fear-oriented stereotypes. These divergent patterns likely stem from distinct national discourses and historical legacies surrounding migration, identity, and social integration.

When it comes to political orientation, “discriminated” was the word most often evoked in both countries in all political orientations, except for Italy’s centre-right and right, with “violent” being the word most evoked in these cases. Italy’s multi-populist historical context translates into a past of parties using their propaganda against the perceived danger that ethnic minorities pose to national identity (Wodak 2015). Therefore, in the Portuguese sample central nuclei, words with a negative connotation do not correspond to the left-wing political orientation. This is in line with Bobbio’s (1996) proposal regarding how the right and left view equality (the right legitimises inequality, while the left challenges it).

In analysing the data through the discursive approach (Laclau), we can identify different sorts of equivalence and antagonism towards minorities, as they emerge within categories such as “discriminated”, “included”, “poor”, “racialised”, and “violent.” These categories reflect calls for either greater security and cultural homogeneity, or for enhanced equality and inclusion. Although these objectives may appear to clash, both discourses converge on the empty signifier of a better society. Thus, a singular signifier can galvanise radically different visions of the people and of the frontier created to define it. Each discourse, however, constructs its subjects differently, revealing the flexibility and tension inherent in populist logic. The data show that both constructions of the people articulate an implicit critique of the existing social order, outlining populist anti-elitism. Yet, consistent with Laclau, the articulation of the people appears to hinge more on the discursive construction of internal equivalences and external antagonisms than on a strictly moral binary (Mudde). The first most predominant discourse exposes systemic injustices and appeals to egalitarian values, whereas the less prominent secondary discourse underscores security and homogeneity. These two seemingly distinct agendas nonetheless share a suspicion of the status quo. The demand for a better society as the empty signifier implicitly identifies the perceived failure of current institutions or elites to meet social demands.

In the present data, the chain of equivalence is observable in the ways participants either extend empathy towards minorities or reinforce boundaries through negative labels. In both Portugal and Italy, the frequent use of the term “discriminated” signals a general recognition of injustice and suggests the existence of an equivalence chain that portrays minorities as deserving of solidarity. While the Portuguese sample also contains central terms such as “included” and “cultural enrichment”, the Italian core includes more negative descriptors like “violent”, “profiteers”, and “repugnant”. This divergence indicates a stronger antagonism towards minorities, revealing in Italy that the people are more often defined in opposition to these others. This becomes an important element in the populist logic, where the unity of the national community can be reinforced by marking minorities as threats to cultural and economic stability.

Sociodemographic trends further illuminate how antagonism and equivalence are formed. Women in both samples tend to mention terms related to equality and respect, indicating that they draw a less exclusionary boundary around the people and express greater willingness to incorporate minorities into the imagined national community. By contrast, men show a slightly higher inclination towards negative descriptors, suggesting a more pronounced exclusionary attitude. Age groups display a similar divergence. Younger participants (18–24) most often evoke neutral or positive terms, perhaps due to greater familiarity with diversity. Meanwhile, those aged 25–34 and 48–54—particularly in Italy—are more likely to describe minorities as “violent”, reflecting a stronger antagonistic stance rooted in lived experiences of economic and migratory crises. Political orientation adds another layer of complexity. In Portugal, left-wing participants exclusively highlight positive representations, such as “discriminated”, pointing to a more inclusive conception of “the people” that contests social inequalities. In Italy, however, centre-right and right-wing respondents more frequently evoke “violent”. This characterisation suggests that their vision of “the people” relies upon a sharper boundary between the national community and threatening others/outsiders. These patterns align with Laclau’s notion that populist discourses hinge on defining chained collective identities as the embodiment of the popular will, while constructing minorities as an antagonistic frontier.

5. Conclusions

The primary aim of this research was to address the question: What are the social representations of minorities in countries like Italy and Portugal, which have experienced a right-wing shift, and to what extent do factors such as age, gender, and political orientation influence these representations? Article findings reveal both commonalities and contrasts in how minorities are socially represented in Portugal and Italy. “Discriminated” emerged as the most frequently evoked term across both samples, suggesting that perceptions of inequality and injustice remain salient in both contexts. At the same time, the stronger presence of negative or stigmatising terms in the Italian central core points to deeper populist narratives. Such narratives have historically resonated in Italy, lending credence to the notion that a legacy of populist discourses can heighten perceptions of minorities as threats or scapegoats. Meanwhile, Portugal’s slightly more inclusive representations highlight the possibility that divergent political histories, integration policies, and less entrenched populist rhetoric can temper overtly negative attitudes.

The findings also exemplify how Laclau’s conception of populism as a political logic characterises equivalence, emptiness, and antagonism. The data show how two distinct populist discourses—one advocating for equality and inclusion, the other prioritising security and homogeneity—rally around “empty signifiers” such as a “better society” or “better future”. Despite their clashing ideological messages, both Italy’s and Portugal’s representations reveal a populist dynamic in which the people is defined in opposition to a perceived failing social order, where minorities are both vulnerable and stigmatised. In this sense, our data underscore how various grievances and anxieties can be articulated into populist claims that may paradoxically both highlight discrimination and reproduce exclusionary stereotypes. The presence of negative stereotypes, particularly in the Italian sample, underscores the influence of populist narratives. While this finding echoes scholarship linking democratic decline to populist political discourse, it also complicates a simple cause-and-effect correlation. Despite the impact of populist influences, many participants—especially in Portugal—displayed supportive, inclusive attitudes towards minorities. Future research could improve the external validity of these results by broadening the scope of the samples and comparing a wider range of countries and political cultures in a diachronic analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.G., L.M., L.S., M.J.C. and S.R.; methodology, C.G., L.M., M.J.C. and S.R.; vali-dation, C.G. and M.J.C.; formal analysis, C.G., L.M., M.J.C. and S.R.; investigation, C.G., M.J.C. and S.R.; resources, C.G. and L.M.; data curation, L.M., M.J.C. and S.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J.C. and S.R.; writing—review and editing, C.G., L.M. and L.S.; visualization, L.M., M.J.C. and S.R.; supervision, C.G., L.M. and L.S.; project administration, C.G. and L.M.; funding acquisition, C.G. and L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is financed by Portuguese national funds through the FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., under the project UNPOP “UNpacking POPulism: Comparing the formation of emotion narratives and their effects on political behaviour” (PTDC/CPO-CPO/3850/2020) and by FCT Funding (UIDP/50012/2020 and 2022.01525.CEECIND/CP1754/CT0005).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Centre for Social Studies (CE-CES)—omissão de Ética do Centro de Estudos Sociais—on 31 August 2021, under the chairmanship of Ana Cordeiro Santos.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abric, Jean-Claude. 1976. Jeux, Conflits et Représentations Sociales. Ph.D. dissertation, Université de Provence, Aix-en-Provence, France. [Google Scholar]

- Abric, Jean-Claude. 1993. Central system, peripheral system: Their functions and roles in the dynamics of social representations. Papers on Social Representations 2: 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Abric, Jean-Claude. 1994a. L’organisation interne des representations sociales: Système central et système périphérique. In Structures et Transformations des Représentations Sociales. Edited by Christian Cuimelli. Colombes: Delachau & Niestlé, pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Abric, Jean-Claude. 1994b. Pratiques Sociales et Représentations. Paris: PUF. [Google Scholar]

- Abric, Jean-Claude. 1997. Coopération, Competition et Représentations Sociales. Doylestown: Cousse DelVal. [Google Scholar]

- Abric, Jean-Claude. 2001. L’approche structurale des représentations sociales: Développements récents. Psychologie et Société 4: 81–103. [Google Scholar]

- Abts, Koen, and Stefan Rummens. 2007. Populism versus Democracy. Political Studies 55: 405–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosetti, Elena, and Angela Paparusso. 2018. Migrants or Refugees? The Evolving Governance of Migration Flows in Italy during the “Refugee Crisis”. Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales 34: 151–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, Fredrik. 1969. Ethnic Groups and Boundaries. In The Social Organisation of Cultural Difference. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Biscaia, Afonso, and Susana Salgado. 2022. Placing Portuguese Right-Wing Populism into Context: Analogies With France, Italy, and Spain. In Advances in Public Policy and Administration. Edited by Dolors Palau-Sampio, Guillermo López García and Laura Iannelli. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 234–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokker, Paul, and Manuel Anselmi. 2019. Multiple populisms. In Italy as Democracy’s Mirror. Milton Park: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bobbio, Norberto. 1996. Left and Right: The Significance of a Political Distinction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bulli, Giorgia, and Filippo Tronconi. 2012. Regionalism, right-wing extremism, populism. In Mapping the Extreme Right in Contemporary Europe. Milton Park: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Caeiro, Mariana. 2019. Média e Populismo: Em Busca das Raízes da Excepcionalidade do Caso Português. Master’s thesis, ISCTE-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Caiani, Manuela. 2022. Populism/Populist Movements. Populisms and Emotions Glossary. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9780470674871.wbespm370.pub2 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Canovan, Margaret. 1999. Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy. Political Studies 47: 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, Manuela. 2010. Race, Crime and Criminal Justice in Portugal. In Race, Crime and Criminal Justice. Edited by Anita Kalunta-Crumpton. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 144–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expresso. 2023. Itália: Meloni Ainda em Estado de Graça um ano Após Eleição. Expresso. September 23. Available online: https://expresso.pt/internacional/2023-09-23-Italia-Meloni-ainda-em-estado-de-graca-um-ano-apos-eleicao-3e8f70ca (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Galhardas, Rodrigo. 2023. Populismo e a Segregação das Comunidades Ciganas em Portugal: O Caso Mediático do Chega! Ph.D. dissertation, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisboa, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Gianolla, Cristiano, Lisete Mónico, and Manuel João Cruz. 2024. Emotion Narratives on the Political Culture of Radical Right Populist Parties in Portugal and Italy. Politics and Governance 12: 8556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Simon. 2003. Cultural Difference as Denied Resemblance: Reconsidering Nationalism and Ethnicity. Comparative Studies in Society and History 45: 343–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indelicato, Maria Elena. 2022. Minority. Populism and Emotions Glossary. Available online: https://unpop.ces.uc.pt/en/glossario/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Indelicato, Maria Elena, and Maíra Magalhães Lopes. 2024. Understanding populist far-right anti-immigration and anti-gender stances beyond the paradigm of gender as ‘a symbolic glue’: Giorgia Meloni’s modern motherhood, neo-Catholicism, and reproductive racism. European Journal of Women’s Studies 31: 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janmaat, Jan G., and Avril Keating. 2019. Are today’s youth more tolerant? Trends in tolerance among young people in Britain. Ethnicities 19: 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, Daniel García. 2021. Constructing the “Good Portuguese” and Their Enemy-Others: The Discourse of the Far-Right Chega Party on Social Media. Ph.D. dissertation, Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Krzyżanowski, Michal, and Per Ledin. 2017. Uncivility on the web: Populism in/and the borderline discourses of exclusion. Journal of Language and Politics 16: 566–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laclau, Ernesto. 2005. On Populist Reason. New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Laclau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe. 2001. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Lanzone, Maria Elisabetta. 2014. The “Post-Modern” Populism in Italy: The Case of the Five Star Movement. In Research in Political Sociology. Edited by Dwayne Woods and Barbara Wejnert. Leeds: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, vol. 22, pp. 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccaferri, Marzia. 2022. Populism and Italy: A theoretical and epistemological conundrum. Modern Italy 27: 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, Laêda Bezerra, and Rosimere Almeida Aniceto. 2010. Núcleo central e periferia das representações sociais de ciclos de aprendizagem entre professores. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação 18: 345–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maratia, Fabio, Beatrice Bobba, and Elisabetta Crocetti. 2023. A near-mint view toward integration: Are adolescents more inclusive than adults? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 153: 2729–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovici, Serge. 1986. L’étude des Représentations Sociales. Paris: Éditions des Archives Contemporaines, pp. 32–58. [Google Scholar]

- Moscovici, Serge. 2011. An essay on social representations and ethnic minorities. Social Science Information 50: 442–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mónico, Lisete, Leonor Pais, Inês Pratas, and Nuno Santos. 2019. Como é o chefe ideal? Um estudo sobre a sua representação social em portugueses. Psicologia 33: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudde, Cas. 2004. The Populist Zeitgeist. Government and Opposition 39: 541–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudde, Cas. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mudde, Cas. 2021. Populism in Europe: An Illiberal Democratic Response to Undemocratic Liberalism (The Government and Opposition/Leonard Schapiro Lecture 2019). Government and Opposition 56: 577–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, Félix. 2007. Atitudes em relação à diversidade cultural: Implicações psicopedagógicas. Revista Portuguesa de Pedagogia 41: 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostiguy, Pierre. 2020. The Socio-Cultural, Relational Approach to Populism. (Version 1.0) [Dataset]. Lecce: University of Salento. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, Beatriz, and Thais França. 2020. Políticas migratórias em Portugal: Complexidade e hiatos entre a lei e a prática. In Sociedades em Movimento: Fluxos Internacionais, Conflitos Nacionais. Edited by Luiz Carlos Ribeiro and Márcio de Oliveira. São Paulo: Intermeios. [Google Scholar]

- Parreira, Pedro, Lisete Mónico, Denise Oliveira, José Cavaleiro, and João Graveto. 2018. Abordagem estrutural das Representações Sociais. In Análise das Representações Sociais e do Impacto da Aquisição de Competências em Empreendedorismo nos Estudos do Ensino Superior Politécnico. Guarda: Instituto Politécnico da Guarda, pp. 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Passarelli, Gianluca, and Dario Tuorto. 2022. From the Lega Nord to Salvini’s League: Changing everything to change nothing? Journal of Modern Italian Studies 27: 400–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, Valerio, Valeria De Cristofaro, Marco Salvati, Mauro Giacomantonio, and Luigi Leone. 2021. Social Exclusion and Anti-Immigration Attitudes in Europe: The mediating role of Interpersonal Trust. Social Indicators Research 155: 697–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petchkovsky, Leon, Michael Petchkovsky, Philip Morris, Paul Dickson, Danielle Montgomery, Jonathan Dwyer, and Patrick Burnett. 2013. fMRI responses to Jung’s Word Association Test: Implications for theory, treatment and research. The Journal of Analitical Psychology 58: 409–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, Hélder, and Miguel Andrade. 2025. Exclusionary Populism in Portugal: “Islamophobia and the Construction of the ‘Otherness’ in the Portuguese Radical Right”. In The Palgrave Handbook on Right-Wing Populism and Otherness in Global. Perspective. Cham: Springer Nature, pp. 359–82. [Google Scholar]

- Quintas Da Silva, Rodrigo. 2018. A Portuguese exception to right-wing populism. Palgrave Communications 4: 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, Martin. 2015. Tangentopoli—More than 20 Years on. Edited by Erik Jones and Gianfranco Pasquino. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, Lydia. 2024. U.S. Women Have Become More Liberal; Men Mostly Stable. GALLUP. February 7. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/609914/women-become-liberal-men-mostly-stable.aspx (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Salgado, Susana, and José Zúquete, eds. 2017. Portugal: Discreet Populisms Amid Unfavorable Contexts and Stigmatization. In Populist Political Communication in Europe. Milton Park: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Santana-Pereira, José, and João Cancela. 2020. Demand without Supply? Populist Attitudes and Voting Behaviour in Post-Bailout Portugal. South European Society and Politics 25: 205–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, Klaus R., Vera Shuman, Johnny R. J. Fontaine, and Cristina Soriano. 2013. The GRID meets the Wheel: Assessing emotional feeling via self-report. In Components of Emotional Meaning: A Sourcebook. Edited by Johnny J. R. Fontaine, Klaus R. Scherer and Cristina Soriano. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermerhorn, Richard. 1970. Comparative Ethnic Relations: A Framework for Theory and Research. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- SIC Notícias. 2022. Resultados Finais das Eleições em Itália Confirmam Maioria da Coligação de Direita. SIC Notícias. September 27. Available online: https://sicnoticias.pt/mundo/2022-09-27-Resultados-finais-das-eleicoes-em-Italia-confirmam-maioria-da-coligacao-de-direita-c5a2061d (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- The Economist Intelligence Unit. 2023. Democracy Index 2023: Age of Conflict. London: The Economist Intelligence Unit. [Google Scholar]

- Thomassen, Lasse. 2024. Ernesto Laclau, Chantal Mouffe and the discursive approach. In Research Handbook on Populism. Edited by Yannis Stavrakakis and Giorgos Katsambekis. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 142–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vala, Jorge. 2000. Representações sociais e psicologia social do conhecimento quotidiano. Psicologia Social 7: 457–502. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek, Bertjan, and Andrej Zaslove. 2016. Italy: A case of mutating populism? Democratization 23: 304–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodak, Ruth. 2015. The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean. Riverside County: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Wojczewski, Thorsten. 2020. ‘Enemies of the people’: Populism and the politics of (in)security. European Journal of International Security 5: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yinger, John. 1986. Intersecting strands in the theorisation of race and ethnic relations. In Theories of Race and Ethnic Relations. Edited by John Rex and David Mason. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 20–41. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).